- 1Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 2Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 3Department of Psychology, Universität Hildesheim, Hildesheim, Germany

Misconduct in prison is a phenomenon, which by its nature is hard to observe. Little is known about its origins and its modifiability. This study presents data on the level of misconduct in prison perceived by staff members and examines its impact on occupational factors. Data from officers, which also included i.e. team climate, job satisfaction, self-efficacy, and sick days, was collected at three different correctional units in Berlin, Germany (N = 60). The study reveals higher rates of perceived misconduct in prison on regular units as compared to treatment units within the observed facilities. In addition, regression analysis provides evidence for an association of rates of misconduct in prison, sick days, and low self-efficacy. Results are discussed in terms of providing a model that supports the idea of a network entailing occupational factors and misconduct in prison and which can be utilized to target misconduct in prison with suitable interventions.

Introduction

Providing safety through regulation is one of the main aspects of the daily work of correctional officers. However, it is common for correctional facilities to be a place where both, inmates and officers, face highly adverse experiences. Adverse experiences can include a wide range of instances with varying degrees of violence, e.g. experiencing (directly) or witnessing (indirectly) physical assaults between inmates (1) or inmates and officers (2), sexual assault among inmates (3–6), or sexual harassment by forensic workers (7) to name only a few. For a complete overview of dangers that officers are confronted with, see Ferdik and Smith (8).

These and other adverse experiences at correctional facilities are harmful in many ways. Depending on the form of violence, inmates who are victimized are confronted with injuries and sexually transmitted diseases (9). In addition, the perception of an unsafe atmosphere as measured by a ward climate instrument is correlated to elevated levels of fear of self-disclosure, which can be regarded as an important aspect of therapy resistance (10). Furthermore, indirect or direct exposure to threats, violence, and the perception of not being safe in an environment can be harmful to inmates, employees, and visitors. A constantly growing body of research points to serious negative consequences in terms of job stress for employees of correctional facilities which are associated with the described adverse experiences (11). In comparison to other occupations, studies on prison officers also report elevated burnout rates (12–15), more frequently diagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder (16), and more drug use (17). These negative health outcomes do not only affect employees on a personal level but can also represent a burden for the organizations because of higher rates of absenteeism or job termination (18).

Negative experiences are made in prisons, especially when the rules intended to guarantee social order are not adhered to. Two models are used to explain the emergence of misconduct in prison. Criminal norm orientation and thus the activities were thought to either be brought into the institution by the inmates themselves (“importation model”; (19)), or the (criminal) subculture existing in the prison was regarded as the result of a process of adaptation to the depriving institutional factors (“deprivation model” (20, 21)). It has been argued that a very unique inmate code is formed within prisons, which the newcomers (must) join (21), and which is associated with very different forms of misconduct, including the negative outcomes mentioned above. Research has shown that both models are suitable to explain inmates’ misconduct (22, 23), which on the other hand shows that neither theory can be considered as complete (23).

One of the main purposes of a prison is to change inmates’ norm orientation while being incarcerated. This aim is not easily accomplished because these dissocial attitudes presumably existed before the imprisonment and led to imprisonment in the first place. It is likely that modifying inmates’ dissocial attitudes could also reduce the extent of misconduct. In the sense of the deprivation model, however, organizational and structural changes can be realized in an economic manner through policy adjustments, in order to reduce prison subculture. Feld (21) found that the more custodial and punitive settings, prison subculture was more violent, more hostile, and more oppositional than those in the treatment-oriented settings were. This is in line with recent evidence that emphasizes the role of prison overcrowding (24) and consequently, inmate-to-staff ratio. Gaining a deeper understanding of the occurrence and determinants of prison misconduct is the aim of this study. In doing so, possibilities of modifying the phenomenon in a way that makes correctional facilitates safer for both, inmates and officers, shall be explored.

Research Questions

Previous research focused on the inmates’ perspective on misconduct in prison has shown that inmates perceive less misconduct on treatment units compared to regular prison units (25). Our group has previously published data on how occupational factors relate to prison’s social climate and treatment motivation of inmates (26). The studies are closely linked since they are both part of an evaluation project, overlapping of participants and psychometric measures will be described in detail in the following paragraphs. Now, in the present study we were aiming at addressing the following hypotheses focusing on prison misconduct: Firstly, we investigated whether officers also perceived differences in misconduct in prison on regular units compared to treatment units. Our hypothesis was that, as in inmates, differences should be perceived. Secondly, misconduct in prison being a fundamental part of the everyday experience of correctional officers, working on treatment units was hypothesized to correlate with occupational factors (OF) such as team climate, job satisfaction, self-efficacy, and sick days. These OFs have been studied and described before by our group (26). Thirdly, we hypothesized that OFs, especially the occurrence of sick days, predict the extent of prison misconduct on treatment units.

Methods

The current study is part of an ongoing evaluation that started in 2014 and encompasses different correctional treatment programs in Berlin, Germany. The Ethics Committee of Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin approved of the study with a positive ethics vote (EA4/131/18).

Data was collected at social-therapeutic facilities for adult and adolescent offenders as well as on a preventive detention unit. In contrast to regular prison units, the aim of these therapeutic facilities is to establish a therapeutic community. In addition to psychotherapy, participants have access to targeted leisure activities and social work. This, together with a lower staff-inmate ratio, is intended to create a supportive climate in order to achieve the therapeutic goals, i.e. the reduction of recidivism (10, 26). The social-therapeutic facilities are not separate, but rather houses or even units within the regular prison. As a result of this, all the persons interviewed—officers as well as inmates—had spent some time on regular units before coming to the therapeutic facility.

Participants

The acquisition of N = 60 participants was a two-step process. First, one third of all officers working at the social-therapeutic facility for male adult and adolescence offenders were randomly selected using the randomize function in Excel (Microsoft, Washington, USA). At the preventive detention unit quota sampling was used, resulting in a subsample that was proportional in terms of gender. All randomly selected participants gave their written consent and took part in an interview with a trained psychologist. In a second step also officers who were not chosen for an interview were able to volunteer and also gave their written consent (n = 12). An overall participation rate of 45% was observed across all sites (n = 42 male and n = 18 female). The participating officers work in treatment units most of the time. However, all of them have prior experience on regular units since it is part of their educational program. In addition, during their daily service it often occurs that officers are deducted from treatment units to regular units due to personal calamity. The subsample deriving from the social-therapeutic facility for male offenders consists of n = 20 correctional officers (33.3%; Age: M = 48.9 years; SD = 8.4; Min-Max = 34–59). In the social-therapeutic facility for adolescent offenders n = 15 correctional officers took part in the study (25.0%; Age: M = 47.4 years; SD = 8.4; Min-Max = 32–59). Twenty-five correctional officers (41.7%; Age M = 46.4 years; SD = 8.9; Min-Max = 30–57) from the preventive detention unit agreed to participate. Data from the same correctional officers studied in a previous paper (26) have been analyzed to investigate the influence of occupational factors on prison misconduct (previous study n = 63, current study n = 60).

Procedure

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by psychologists (level of education: master’s degree or higher) within the institutions during working hours of the officers. Interviews took between 1.5 and 2 h and included, among others, different questionnaires (shortened and/or adopted from previous research and own developments) covering misconduct in prison, team climate, job satisfaction, and self-efficacy.

Psychometric Measures

Interviews With the Participants About Subjectively Perceived Misconduct in Prison (PMP)

We decided to record self-reported misconduct. It can be assumed that misconduct that was not always considered as official could also be a burden for employees (e.g. hierarchies, verbal threats). Since it was precisely the individual effects of the employees that were the focus of the study, recording subjective perception seemed to be of crucial importance. As both self-reported and official misconduct had been valid and reliable indicators of inmate behavior in previous studies (23, 27), we felt that such an approach was appropriate. All officers were asked about the extent of misconduct they perceived using a Likert-scale (0 = never to 3 = often). A total of eleven questions cover very different forms of misconduct (e.g. drugs/alcohol, sexual assault; see Table 1 for an overview). Nine of the questions focus on possible misconduct by inmates. The other two questions, on the other hand, focus on possible misconduct committed by prison staff (unjustified priority treatment and suppression). Each officer completed the questions for two work sites, i.e. regular and treatment units. Internal consistency was measured as Cronbach’s Alpha for the PMP as rated by officers for treatment units and regular units is acceptable (ρT =.794; ρT =.775). The PMP measures the perception of misconduct and is not an objective measure.

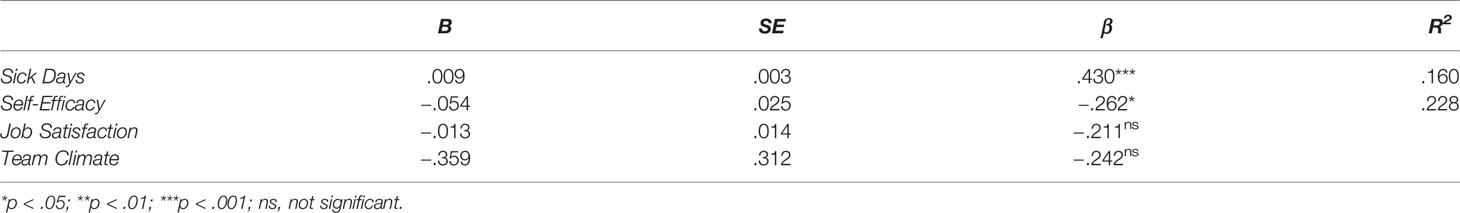

Table 1 Perceived Misconduct in Regular Units vs. Treatment Units from Officers’ Perspective (n = 60).

Team Climate

The Team Climate Inventory (TCI; (28)) is a questionnaire aiming at measuring work atmosphere in teams. The initial 44-item TCI was shortened to 15 items for economic reasons of the evaluation project: The remaining items cover three subscales: (1) safety (5 items), (2) vision (7 items), and (3) task orientation (3 items). (1) Safety measures the environmental perception of safety and the possibility of participation in decision-making. (2) Vision captures the aim of a team. (3) Task orientation collects efforts of the team members to further develop performance and quality of work (Likert-scale: 1 = not at all to 5 = completely). Internal consistency for the shortened TCI is good (ρT =.839).

Job Satisfaction

To gather data on job satisfaction, unpublished adaptions derived from the abridged Job Descriptive Index (JDI; (29)) and the SAZ (Skala zur Erfassung der Arbeitszufriedenheit; (30)) were used. The specifically tailored job satisfaction scale entails eight items asking about satisfaction with colleagues, supervisor, work task, working conditions, organization, management, workload, and opportunities (Likert-scale: 0 = completely unsatisfied to 5 = completely satisfied). Internal consistency for the adapted job satisfaction scale is good (ρT =.817).

Self-Efficacy

Two unpublished versions (for teachers and nurses) of the general self-efficacy scale (SWE; (31)) were shortened and adopted for the use in correctional facilities. The five items of the questionnaire measure perceptions of self-efficacy of officers in dealing with difficult and suspicious inmates (Likert-scale: 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Internal consistency for the adapted self-efficacy scale is questionable (ρT =.651).

Sick Days

Data on sick leave were collected via the administrative council of the facilities. Due to data protection regulations sick days could only be collected as average numbers per year. The studied OFs, namely Team climate, Job satisfaction, Self-efficacy, and Sick days are also described in detail in our previous study (26).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 25.0 for Mac OS (IBM, Armonk, NY). First, paired-samples (two-tailed) t-tests were conducted to test for differences in perceived misconduct in prison ratings between regular units and treatment unit. Next, Pearson-correlations were calculated for perceived misconduct in prison ratings on treatment units and OFs (team climate, job satisfaction, sick days, and self-efficacy). According to Cohen (32), values of 0.1 and above represent a small effect, 0.3 and above represent a moderate effect and 0.5 and above represent a strong effect. Bonferroni-corrections were applied to all tests. Lastly, perceived misconduct in prison ratings from treatment units, but not regular units, were linear, stepwise regressed on OFs. All variables were normally distributed (Kolmogorov-Smirnov-Test: p-value Range =.051–.689).

Results

Officers’ Perception of Misconduct in Prison in Regular and Treatment Units

Bonferroni-corrected t-tests revealed that correctional officers perceived overall more misconduct in prison in regular as compared to treatment units (see Table 1). In fact, that difference in perception holds for all subscales except unjustified priority by staff members (p =.209).

Misconduct in Prison and Its Correlation With Team Climate, Job Satisfaction, and Sick Days

Two-tailed Pearson-correlations for perceived misconduct in prison ratings and OFs (team climate, job satisfaction, sick days, and self-efficacy) confirmed our hypothesis that perceived misconduct in prison moderately correlate with team climate (r = −.34, p < .05), job satisfaction (r = −.38, p < .01), and sick days (r =.42, p < .01).

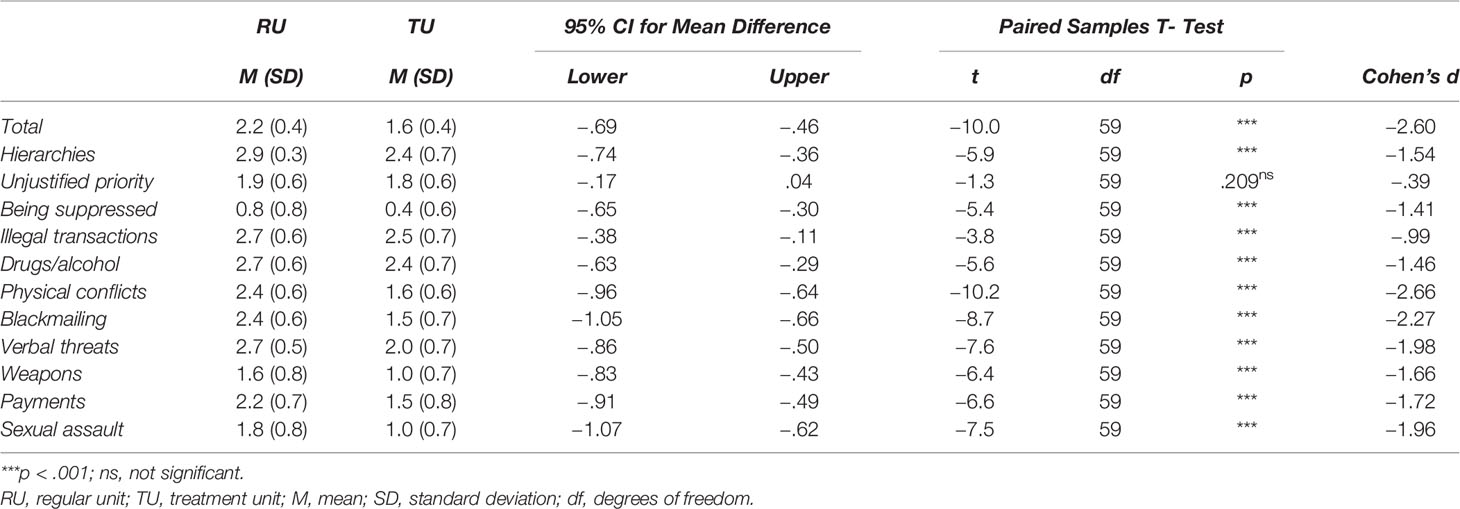

Other than assumed, self-efficacy did not correlate significantly with perceived misconduct in prison in treatment units (r = −.20, p =.126). Having a closer look at the full correlation matrix (see Figure 1), it becomes apparent which types of perceived misconduct in prison are associated with which OF on treatment units. Team Climate is correlated negatively to physical conflicts between inmates (r = −.29, p < .05), blackmail (r = −.34, p < .01), verbal threats (r = −.26, p < .05), and the detention of (self-built) weapons (r = −.41, p < .01) on treatment units. Job satisfaction is correlated negatively to hierarchies between inmates (r = −.36, p < .01), unjustified priority treatment by staff members (r = −.28, p < .05), physical conflicts (r = −.39, p < .01), blackmail (r = −.33, p < .05), and verbal threats between inmates (r = −.35, p < .01).

Figure 1 Correlation matrix of different aspects of perceived misconduct in prison and occupational factors. Significant correlations range from dark blue (+1) to dark red (−1). Insignificant correlations are shown in white. Each square is showing the correlation coefficient. JS, job satisfaction; PMP, perceived misconduct in prison; SE, self-efficacy; TCI, team climate inventory; TCI_S, team climate inventory subscale safety; TCI_V, team climate inventory subscale vision; TCI_TO, team climate inventory subscale task orientation.

Sick days are correlated positively to hierarchies (r =.45, p < .01), unjustified priority treatment by staff members (r =.38, p < .01), physical conflicts (r =.46, p < .01), blackmail (r =.43, p < .01), verbal threats (r =.29, p < .05), and sexual assaults between inmates (r =.29, p < .05). As the complete correlation matrix shows, OFs are also associated with each other. In particular, team climate is moderately correlated to job satisfaction (r =.53, p < .01) and job satisfaction is moderately correlated to sick days (r = −.47, p < .01).

Influence of Sick Days and Self-Efficacy on Perceived Misconduct in Prison

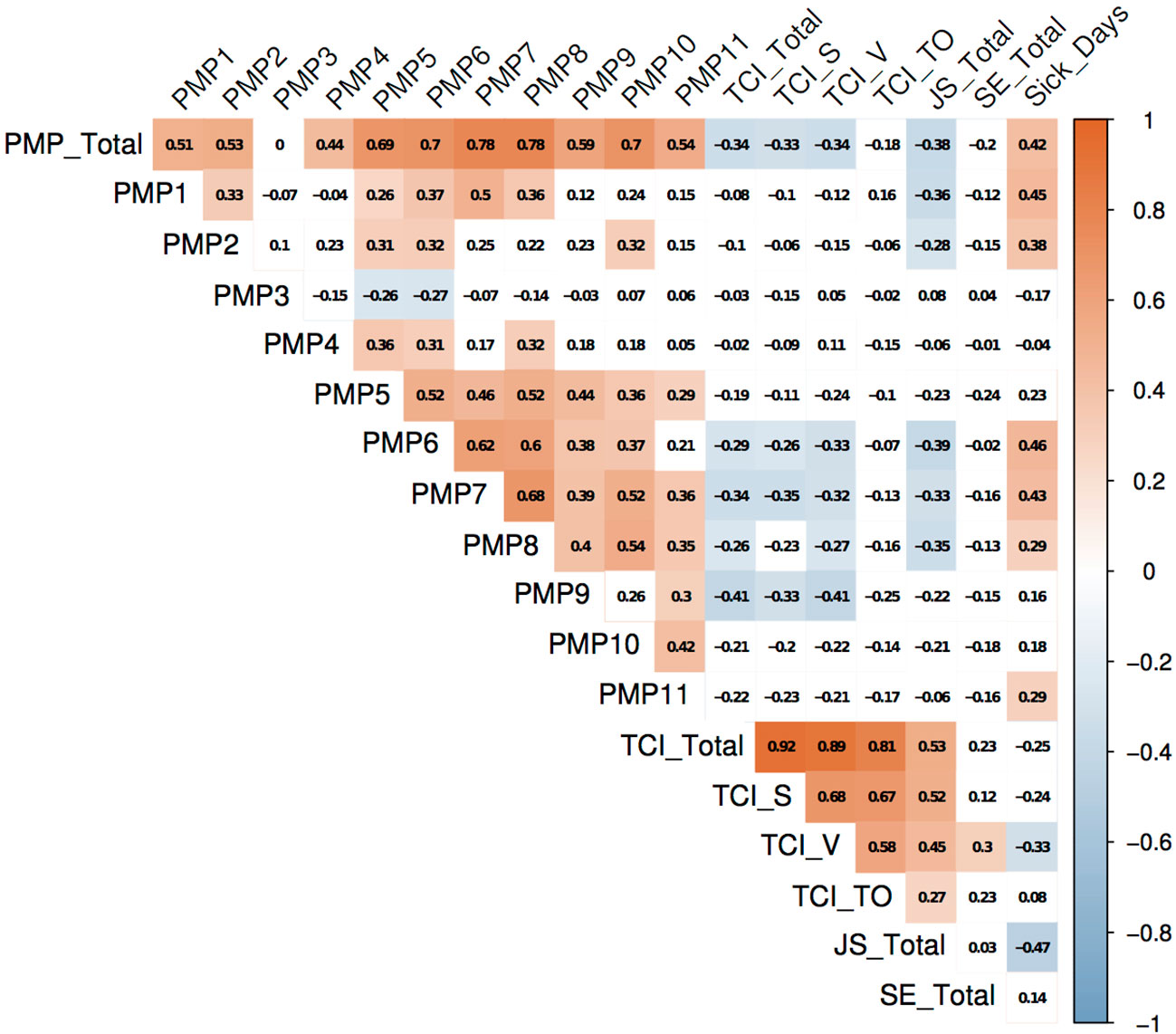

Our third hypothesis, i.e. OFs predicting perceived misconduct in prison, was confirmed for treatment units (F(2,52) = 7.68, p < .001), and to be more specific for sick days (R2 =.16) and self-efficacy (R2 =.23, see Table 2). Job satisfaction (β = −.21, p =.134) and team climate (β = −.242, p =.065) were not significantly associated with perceived misconduct.

Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between misconduct in prison and occupational factors from the officers’ perspective. The results support the idea that OFs are associated with various forms of misconduct in treatment units that can corrupt safety and rehabilitation in correctional facilities. The results of the study also provide the possibility to speculate on hypothetical starting points for modifying prison misconduct in such a way that the experience of imprisonment and imprisoning might become safer, and thus comes closer to the legal goal of rehabilitation treatment.

Officers perceived less misconduct in prison on treatment units compared to regular units. This finding complements work from Sauter and colleagues (25), according to which the inmates also reported less misconduct in treatment units. The study has also shown that OFs are correlated not only to each other but also to different aspects of misconduct in prison on treatment units. Also, occupational factors, i.e. sick days and self-efficacy of officers together explain 22.8% of variance in misconduct in treatment units. The majority of studies investigating the risk factors of misconduct in prison have focused on inmate’s characteristics such as sex and prior record (23) as well as prison characteristics such as prison crowding (33, 34). In a meta-analysis French & Gendreau (35) have identified three main strategies that can be utilized to effectively lower prison misconduct: a) “get tough” meaning very low levels of service and strategies such as solitary confinement in order to discipline inmates, b) “situational control strategies” including variables such as prison climate and inmate-to-staff-ratio, and c) treatment programs that aim at behavioral changes of the inmates. The highest effectiveness was found for behavioral treatment programs (r =.26). Fewer studies have investigated how factors related to correctional officers influence prison misconduct of inmates. Recently, several studies have highlighted the importance of staff-related factors in relation to inmate’s behavior. Findings from 3,886 inmates in Ohio (USA) prisons suggest that inmates’ perceived legitimacy of correctional officers results in fewer nonviolent infractions (36). However, perceived legitimacy was not associated with violent misconduct in this study (36). Moreover, Logan and colleagues (37) highlight the importance of the staff-inmate relationship and state that officers can affect inmates’ behavior positively and negatively during their incarceration (e.g. (38, 39)). Taken together, these studies highlight the importance of investigating factors related to correctional officers in order to influence inmate’s behavior, including misconduct. Our results provide first time evidence that self-efficacy and sick days of correctional officers are related to perceived misconduct in prison, therefore highlighting the potential of these factors in reducing prison misconduct.

By its design, the study provides us with the possibility of speculating on starting points to create interventions in order to target the extent of harmful misconduct in prison. The study shows that misconduct in prison is associated with sick days. Important to note, sick leave itself can be a result of exposure to violence and threat at work (40, 41). Combining these results suggests a possible network of adverse experiences in prison that is further supported by the correlations found in the study.

The proposed network provides us with multiple hypothetical starting points for planning interventions in order to reduce destructive misconduct in prison. One target point could be to limit the potentially cost intensive consequences of sick leave by temporarily providing competent employee replacement. Even better, personal levels could be increased all together. In that way, well-educated and accustomed staff could serve as a suitable replacement for colleagues in sick leave right away. Another targeting point could be to create programs to elevate levels of team climate, job satisfaction, and self-efficacy. An improvement of team climate could be achieved by implementing team supervisions and team building. Job satisfaction could be improved by shaping working conditions, organization, management, and workload. Improving OFs, especially sick days, might result in less misconduct, fewer incidence of exposure to adverse and violent experiences and therefore levels of OFs should increase. The following limitations should be considered: Data presented here relies solely on the officers’ perception of misconduct in prison. However, using the same questions Sauter and colleagues (25) found that perceptions on misconduct did not differ in the overall picture between inmates and officers. Only minor differences were found, most likely due to distortions caused by in- and out-group biases (42, 43). Another important limiting factor is that the results represent solely association findings which do not imply causality or a direction of effect. Therefore, the discussed network, as well as the proposed interventions are partly hypothetical and need further research in order to gain more insight into possible causal effects. Also, the sample size is low and complementing data from officers working in regular units most of their daily routine should be collected to further investigate the relationship of occupational factors and misconduct in regular prison units. Another limitation is that the adapted and revised questionnaires which derived from already existing and validated questionnaires are so far not validated. The reason for modifying the questionnaires was to make the interviews as economical as possible. The questionable reliability of the self-efficacy scale has to be emphasized at this point. It is possible that the instrument was not adapted in a suitable manner and decreased in item number too drastically. Further research on this instrument is needed.

The aim of this study was to provide empirical data on the potential of occupational factors to help to create an atmosphere that can prevent or at least minimize misconduct in prison. Officers’ care therefore not only seems to pay off for the officers themselves, but also seems to be suitable for coming closer to the legal goal of rehabilitation and resocialization. Sick days and self-efficacy were identified as being linked to misconduct in prison and thereby added to a growing body on literature on misconduct and its correlates in correctional facilities. The paper presented hypothetical interventions that might influence the extent of misconduct. Longitudinal future studies have to investigate if and under what circumstances misconduct can be minimized with the proposed interventions.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Senate of Justice and Consumer Protection of Berlin.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study will not be made publicly available. This study is part of an evaluation project commissioned by the Berlin Senate for Justice, Consumer Protection and Anti-Discrimination. We do not have the right to disclose the data.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by ethics committee of Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

JV: data analysis and preparation and revision of manuscript. JS: questionnaire design, manuscript preparation and revision. B-OV: manuscript preparation and revision, figures. K-PD: study supervision, administrative, technical, and material support, manuscript revision.

Funding

The Senate of Justice and Consumer Protection of Berlin, Germany funded the evaluation project.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Wooldredge J, Steiner B. Violent victimization among state prison inmates. Violence Vict (2013) 28:531–51. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.11-00141

2. Konda S, Reichard AA, Tiesman HM. Occupational injuries among U.S. correctional officers, 1999-2008. J Saf Res (2012) 43:181–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2012.06.002

3. Einat T. Inmate harassment and rape: an exploratory study of seven maximum- and medium-security male prisons in Israel. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol (2009) 53:648–64. doi: 10.1177/0306624X08321953

4. Einat T. Rape and Consensual Sex in Male Israeli Prisons: Are There Differences With Western Prisons? Prison J (2013) 93:80–101. doi: 10.1177/0032885512467316

5. Hilinski-Rosick CM, Freiburger TL. Sexual Violence Among Male Inmates. J Interpers Violence (2018), 886260518770190. doi: 10.1177/0886260518770190

6. Kubiak SP, Brenner H, Bybee D, Campbell R, Fedock G. Reporting Sexual Victimization During Incarceration: Using Ecological Theory as a Framework to Inform and Guide Future Research. Trauma Violence Abuse (2018) 19:94–106. doi: 10.1177/1524838016637078

7. Faulkner C, Regehr C. Sexual boundary violations committed by female forensic workers. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law (2011) 39:154–63.

8. Ferdik FV, Smith H. Correctional Officer Safety and Wellness Literature Synthesis. Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice: U.S. Department of Justice (2017).

9. Robertson JE. Rape among incarcerated men: sex, coercion and STDs. AIDS Patient Care STDS (2003) 17:423–30. doi: 10.1089/108729103322277448

10. Stasch J, Yoon D, Sauter J, Hausam J, Dahle K-P. Prison Climate and Its Role in Reducing Dynamic Risk Factors During Offender Treatment. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol (2018) 62:4609–21. doi: 10.1177/0306624X18778449

11. Dowden C, Tellier C. Predicting work-related stress in correctional officers: A meta-analysis. J Crim Justice (2004) 32:31–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2003.10.003

12. Boudoukha AH, Hautekeete M, Abdellaoui S, Groux W, Garay D. Burnout and victimisation: impact of inmates’ aggression towards prison guards. Encephale (2011) 37:284–92. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2010.08.006

13. Griffin ML, Hogan NL, Lambert EG, Tucker-Gail KA, Baker DN. Job Involvement, Job Stress, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment and the Burnout of Correctional Staff. Crim Justice Behav (2010) 37:239–55. doi: 10.1177/0093854809351682

14. Griffin ML, Hogan NL, Lambert EG. Doing “People Work” in the Prison Setting: An Examination of the Job Characteristics Model and Correctional Staff Burnout. Crim Justice Behav (2012) 39:1131–47. doi: 10.1177/0093854812442358

15. Schaufeli WB, Peeters MCW. Job stress and burnout among correctional officers: A literature review. Int J Stress Manag (2000) 7:19–48. doi: 10.1023/A:1009514731657

16. Spinaris CG, Denhof MD, Kellaway JA. Posttraumatic stress disorder in United States corrections professionals: Prevalence and impact on health and functioning. Desert Waters Correctional Outreach (2012), 1–32.

17. Svenson LW, Jarvis GK, Campbell RL, Holden RW, Backs BJ, Lagace DR. Past and current drug use among Canadian correctional officers. Psychol Rep (1995) 76:977–8. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1995.76.3.977

18. Lambert EG, Hogan NL, Altheimer I. An Exploratory Examination of the Consequences of Burnout in Terms of Life Satisfaction, Turnover Intent, and Absenteeism Among Private Correctional Staff. Prison J (2010) 90:94–114. doi: 10.1177/0032885509357586

19. Thomas CW, Petersen DM. Prison organization and inmate subcultures. IN: Bobbs-Merrill Indianapolis (1977).

20. Clemmer D, The prison community. (1940). Available at: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1940-05154-000.

21. Feld BC. A Comparative Analysis of Organizational Structure and Inmate Subcultures in Institutions for Juvenile Offenders. Crime Delinquency (1981) 27:336–63. doi: 10.1177/001112878102700303

22. Hartnagel TF, Gillan ME. Female Prisoners and the Inmate Code. Pac Sociol Rev (1980) 23:85–104. doi: 10.2307/1388804

23. Steiner B, Butler HD, Ellison JM. Causes and correlates of prison inmate misconduct: A systematic review of the evidence. J Crim Justice (2014) 42:462–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2014.08.001

24. Steiner B, Ellison JM, Butler HD, Cain CM. The Impact of Inmate and Prison Characteristics on Prisoner Victimization. Trauma Violence Abuse (2017) 18:17–36. doi: 10.1177/1524838015588503

25. Sauter J, Seewald K, Vogel J, Dahle KP. The challenge of offender rehabilitation in a parallel universe: Effects of misconduct in prison on treatment-related variables in correctional treatment units. in preparation (2020).

26. Sauter J, Vogel J, Seewald K, Hausam J, Dahle K-P. Let’s Work Together - Occupational Factors and Their Correlates to Prison Climate and Inmates’ Attitudes Towards Treatment. Front Psychiatry (2019) 10:781. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00781

27. Steiner B, Wooldredge J. Comparing Self-Report to Official Measures of Inmate Misconduct. Justice Q (2014) 31:1074–101. doi: 10.1080/07418825.2012.723031

29. Stanton JM, Bachiochi PD, Robie C, Perez LM, Smith PC. Revising the Jdi Work Satisfaction Subscale: Insights into Stress and Control. Educ Psychol Meas (2002) 62:877–95. doi: 10.1177/001316402236883

30. Fischer L, Lück HE. Entwicklung einer Skala zur Messung von Arbeitszufriedenheit (SAZ). Psychol Und Praxis (1972) 16:64–76.

31. Jerusalem M, Schwarzer R. Fragebogen zur Erfassung von” Selbstwirksamkeit. In: Skalen zur Befindlichkeit und Persoenlichkeit In R Schwarzer (Hrsg ) (Forschungsbericht No 5). Berlin: Freie Universitaet, Institut fuer Psychologie (1981).

32. Cohn J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbam Associates (1988).

33. Franklin TW, Franklin CA, Pratt TC. Examining the empirical relationship between prison crowding and inmate misconduct: A meta-analysis of conflicting research results. J Crim Justice (2006) 34:401–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2006.05.006

34. Glazener E, Nakamura K. Examining the Link Between Prison Crowding and Inmate Misconduct: Evidence from Prison-Level Panel Data. Justice Q (2018) 37:1–23. doi: 10.1080/07418825.2018.1495251

35. French SA, Gendreau P. Reducing Prison Misconducts. Crim Justice Behav (2006) 33:185–218. doi: 10.1177/0093854805284406

36. Steiner B, Wooldredge J. Prison officer legitimacy, their exercise of power, and inmate rule breaking. Criminology (2018) 56:750–79. doi: 10.1111/1745-9125.12191

37. Logan MW, Jonson CL, Johnson S, Cullen FT. Agents of Change or Control? Correlates of Positive and Negative Staff-inmate Relationships among a Sample of Formerly Incarcerated Inmates. Corrections (2020), 1–21. doi: 10.1080/23774657.2020.1749181

38. Hacin R, Meško G. Prisoners’ Perception of Legitimacy of the Prison Staff: A Qualitative Study in Slovene Prisons. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol (2018) 62:4332–50. doi: 10.1177/0306624X18758896

39. Schaefer L. Correcting the “Correctional” Component of the Corrections Officer Role: How Offender Custodians Can Contribute to Rehabilitation and Reintegration. Corrections (2018) 3:38–55. doi: 10.1080/23774657.2017.1304811

40. Andersen LP, Hogh A, Elklit A, Andersen JH, Biering K. Work-related threats and violence and post-traumatic symptoms in four high-risk occupations: short- and long-term symptoms. Int Arch Occup Environ Health (2019) 92:195–208. doi: 10.1007/s00420-018-1369-5

41. Biering K, Andersen LPS, Hogh A, Andersen JH. Do frequent exposures to threats and violence at work affect later workforce participation? Int Arch Occup Environ Health (2018) 91:457–65. doi: 10.1007/s00420-018-1295-6

42. Efferson C, Lalive R, Fehr E. The coevolution of cultural groups and ingroup favoritism. Science (2008) 321:1844–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1155805

Keywords: misconduct in prison, offender treatment, correctional officers, self-efficacy, sick days

Citation: Vogel J, Sauter J, Vogel B-O and Dahle K-P (2020) Targeting Misconduct in Prison by Modifying Occupational Factors in Correctional Facilities. Front. Psychiatry 11:517. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00517

Received: 06 September 2019; Accepted: 20 May 2020;

Published: 05 June 2020.

Edited by:

Birgit Angela Völlm, University of Rostock, GermanyReviewed by:

Jack Tomlin, University of Rostock, GermanyStanislava Harizanova, Plovdiv Medical University, Bulgaria

Copyright © 2020 Vogel, Sauter, Vogel and Dahle. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joanna Vogel, am9hbm5hLnZvZ2VsQGNoYXJpdGUuZGU=

Joanna Vogel

Joanna Vogel Julia Sauter

Julia Sauter Bob-Oliver Vogel

Bob-Oliver Vogel Klaus-Peter Dahle1,3

Klaus-Peter Dahle1,3