- 1Faculty of Education, Shitennoji University, Habikino, Japan

- 2Hiratani Child Development Clinic, Fukui, Japan

We examined the association of mental health problems with preventive behavior and caregivers' anxiety in children with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD) and their caregivers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Data were obtained from 227 pairs of children with NDD and their caregivers in a clinic in Fukui Prefecture, Japan, from October 1 to December 31, 2020. During this period, the activities of children and caregivers were not strongly restricted by the public system. Caregivers' anxiety about children's activities was positively associated with caregivers' and children's fears of COVID-19 and children's depressive symptoms. Children's preventive behavior was negatively associated with children's depressive symptoms. These findings suggested that caregivers' fear of COVID-19 stemmed from worry about the relationship between children's activity and COVID-19 infection, and children might have reflected caregivers' expressions of concern. In schools and clinics, practitioners educate children on how to engage in preventive behavior against COVID-19. Our results support the effectiveness of such practices in mitigating mental health problems in children with NDD.

Introduction

Lifestyles have been changed by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic; these changes have impacted mental health problems in the general population (1). The mortality risk of COVID-19 is low for children and most caregivers (2), and children are not the main drivers of COVID-19 (3). However, COVID-19 affects the mental health problems of children and their caregivers. For example, the rate of children with a low quality of life increased during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic (4). It has been reported that about 60% of caregivers expressed worry that their child would catch COVID-19 at school (5).

Children with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD), such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD), are at risk for mental health problems (6, 7). Similar risks have also been found in their caregivers (8, 9). In a survey during the COVID-19 pandemic, a higher prevalence of emotional symptoms and conduct problems and fewer prosocial behaviors were found in children with NDD than in those with neurotypical development [NTD; (10)]. Mental health and behavioral problems increased during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic in children with NDD (11, 12). In addition, externalizing behavior was higher in children with NDD than in those with NTD, and that behavior was associated with parenting stress during the COVID-19 pandemic (13, 14). These results suggest that mental health has been worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic in children with NDD as well as in their caregivers.

Educating the public with appropriate information about COVID-19 and related preventive behaviors has been considered important for mitigating children's mental health problems (15). In a previous study, adults who engaged in preventive behavior tended to have better mental health (16). In schools, teachers have provided students with knowledge about COVID-19 and related preventive behaviors (17). In addition, brochures have been developed to educate children with ASD on knowledge and preventive behavior (18). However, there is no evidence that knowledge and preventive behavior are associated with mental health problems in children with NDD.

The behavior and mental health problems of children interact with those of their caregivers (19, 20). In a study from before the COVID-19 pandemic, mothers' anxiety and fearfulness were found to be associated with the anxiety and fearfulness of children (21). Children of caregivers with anxiety disorders tend to be more anxious and fearful than children of caregivers without anxiety disorders (20, 22). Most caregivers worried that their child would catch COVID-19 at school (5). Thus, it is possible that caregivers' anxiety about children's activities related to COVID-19 infection was associated with children's mental health problems.

In this study, we examined the association of mental health problems with preventive behavior and caregivers' anxiety about children's activities in children with NDD and their caregivers. We used data from patients and their caregivers in a clinic in Fukui Prefecture. Japan was in a state of emergency from April 7 to May 25, 2020. During that time, citizens were required to stay home, and children stopped participating in school activities. The number of cases was smaller in Japan than in other developed countries (23). Children continued to participate in school activities starting at the end of the first state of emergency (May 25, 2021). Thus, the activities of children and caregivers were not strongly restricted by public systems. Moreover, Fukui Prefecture is a provincial area of Japan, with a population of approximately 760,000. During the survey period (i.e., October 1 to December 31, 2020), 111 people were infected in the Fukui Prefecture (24). That is, the number of cases was much smaller in Fukui Prefecture than in metropolitan areas of Japan and other countries. On the other hand, the government recommended preventive behavior (25), and the media conveyed information about COVID-19 daily. Thus, we hypothesized that mental health problems of children with NDD and their caregivers would be associated with knowledge about COVID-19, preventive behavior for COVID-19 infection, and caregivers' anxiety about children's activities related to COVID-19, rather than to the COVID-19 pandemic itself.

Mental health problems were evaluated from two aspects: fears of COVID-19 and general mental health problems. The Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S) have been developed (26), and was widely used to assess fears of COVID-19. We assumed that the fears of COVID-19 were associated with knowledge about COVID-19, preventive behavior for COVID-19 infection, and caregivers' anxiety about children's activities related to COVID-19. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic not only influenced fears regarding the virus itself but also general mental health problems (1). We examined the association of general mental health problems with the variables. In the secondary analysis, we confirmed the relationship between fears of COVID-19 and general mental health problems (26). Further, we thought it useful for clinical practice to clarify types of preventive behavior that children with NDD understood and engaged in. Thus, we examined the difference in items of knowledge about COVID-19 and preventive behavior for COVID-19 infection.

Methods

Participants

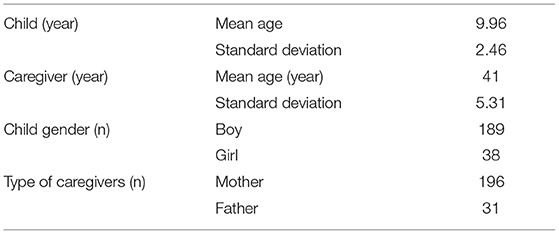

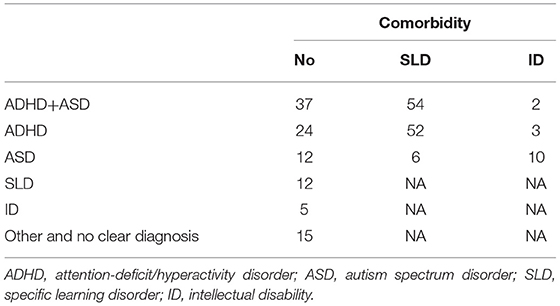

The participants were children with NDD and their caregivers. We recruited 252 children and 294 caregivers from a developmental clinic in Fukui Prefecture from October 1 to December 31, 2020. All caregivers of the 252 children participated in this study. One pair withdrew their participation after submitting their responses. After excluding incomplete responses, data from 232 pairs remained. Five pairs were excluded because children's IQs were lower than 50. Thus, we used data from 227 pairs in the analyses. The ages of the children ranged from 6 to 18 years. The characteristics and diagnoses are shown in Tables 1, 2. Some children were not diagnosed with clear NDD (e.g., children with low IQ but not intellectual disability and children with ASD tendencies). The caregivers provided written informed consent before participation, and informed consent was obtained from all the children. The study design was approved by the ethics committee of Shitennoji University (2020-17).

Fear of COVID-19

The Japanese version of FCV-19S [FCV-19S-J; (27)] was used to assess the fear of COVID-19 in caregivers. The FCV-19S-J (27) and the original version (26) consists of seven items, and caregivers rated their state using a five-point Likert-type scale (strongly disagree = 1 to strongly agree = 5). Total scores were used for the analysis. A higher score represents a higher degree of fear related to COVID-19.

The expressions of items of the FCV-19S-J were revised to be suitable for children. One item, “I am afraid of losing my life because of COVID-19,” was considered to be too invasive for children with NDD. Thus, we revised this item to “I am afraid of being admitted to a hospital because of COVID-19.” Children rated their state on a five-point Likert-type scale (strongly disagree = 1 to strongly agree = 5). We performed a factor analysis using the maximum-likelihood estimation method. The factor loadings of items ranged from 0.43 to 0.75. Thus, similar to FCV-19S-J, we used the sum of the items to assess fear of COVID-19 in children.

General Mental Health Problems of Children and Caregivers

The Japanese version of the Birleson Depression Self-Rating Scale for Children [DSRS-C; (28)] was used to assess general mental health problems in children. The DSRS-C consists of 18 items that assess depressive symptoms (29). Children rated their states using a three-point scale (none of the time = 0 to all of the time = 2). We used the sum score of the DSRS-C for the analysis. A higher score indicates a higher degree of depressive symptoms.

To assess general mental health problems of caregivers, we used the Japanese version of the Kessler 6-items Psychological Distress Scale [K6; (30, 31)]. K6 consists of six items that assess depressive and anxiety symptoms. Caregivers rated their state using a five-point Likert-type scale [none of the time = 0 to all of the time = 4; (30)]. The sum score was used in the analysis. A higher score indicates a higher degree of psychological distress.

Children's Knowledge and Preventive Behavior

Children's knowledge about COVID-19 was tested by seven items: “stay home,” “don't go to crowded places,” “don't speak closely with friends,” “open windows,” “put on a mask outside of the house,” “frequently wash hands,” and “don't touch your eyes, nose, and mouth.” The items were made based on information from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in Japan in August 2020 (25). Children rated whether the item was related to the prevention of COVID-19 using a three-point scale (incorrect = 1 to correct = 3). We used the mean score of items for the analysis and considered that a higher score represents more appropriate knowledge.

Children's preventive behavior for COVID-19 infection was assessed by themselves and caregivers using seven items identical to those used to assess children's knowledge. Children and caregivers rated how often children engaged in preventive behavior of each item, using a three-point scale (none of time = 1 to always = 3). We used both the mean scores of items rated by children and caregivers for the analysis and considered higher scores to represent more appropriate preventive behavior.

Caregivers' Preventive Behavior and Anxiety

Caregivers' preventive behavior for COVID-19 infection was assessed using seven items identical to those used to assess children. Caregivers rated adherence to preventive behavior of each item on a six-point scale (behave very incompletely = 1 to behave very completely = 6). We used the mean score of items for the analysis and considered higher scores to represent more appropriate behavior.

Caregivers' anxiety about children's activities related to COVID-19 infection was assessed using six items on children's activities: “school,” “playing with their friends,” “time with their family,” “vacation,” “hospital,” and “all activities.” Caregivers rated their children's activity using a five-point scale (“I am not afraid of the activity at all” = 0 to “I am very afraid of the activity” = 5). We used the mean score of the items for the analysis. A higher score represents a higher degree of anxiety about children's activities related to COVID-19 infection.

Problematic Behavior

The Japanese version of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist [ABC-J; (32, 33)] was used for assessing problematic behavior of children. The ABC-J consists of 58 items that are classified into five subscales: “irritability,” “lethargy,” “stereotypic behavior,” “hyperactivity,” and “inappropriate speech.” Caregivers rated children's behavior using a four-point scale (no problem = 0 to remarkable problem = 4). We used the sum score for each subscale.

Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the free statistical environment R 3.52 (34). The association between fear of COVID-19 and general mental health problems with other variables was tested using stepwise multiple regression analyses based on Akaike information criteria. For this, we used children's knowledge about COVID-19; their preventive behaviors regarding COVID-19 infection, as rated by both the children and caregivers; caregivers' preventive behavior regarding COVID-19 infection; and their anxiety about children's activities related to COVID-19 infection as independent variables. Additionally, previous studies have shown the association between behavioral characteristics and mental health problems among children with NDD and their caregivers (35, 36). Hence, we added irritability, lethargy, stereotypical behavior, hyperactivity, and inappropriate speech as independent variables. We also added children's age, gender, and IQ and the caregivers' age and type of caregivers (father = 0, mother = 1) as control variables. Finally, the above variables were incorporated in the first model of step-wise regression analyses.

The relationship between children's and caregivers' fears of COVID-19 and general mental health problems was tested using Pearson's correlational test. We evaluated the differences among items in children's knowledge and children's preventive behaviors rated by children and caregivers using one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs). A Bonferroni test was used for multiple comparisons (α = 0.05).

For correlational analysis and regression analysis, we excluded the data of a participant from the analysis when there was more than one missing value in each variable. When there was one missing value, we calculated the mean values for the data, excluding the missing values, and then used the mean value as the score for the item with a missing value. For ANOVAs on variables, we excluded the data of participants with missing values.

Results

Step-Wise Regression Analyses on Fear of COVID-19

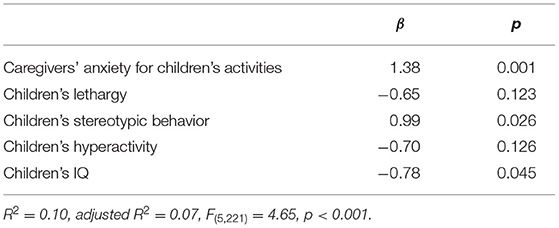

Table 3 shows the results of the step-wise regression analysis on children's fear of COVID-19. The final model included caregivers' anxiety regarding children's activities, children's lethargy, children's stereotypic behavior, children's hyperactivity, and children's IQ. We found that the model was significantly associated with children's fear of COVID-19 (p < 0.001); children's fear of COVID-19 had significant positive associations with caregivers' anxiety about children's activities and children's stereotypical behavior, whereas it had a significant negative association with children's IQ (Table 3).

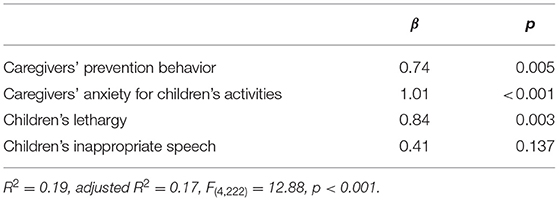

Table 4 shows the result of the step-wise regression analysis on caregivers' fear of COVID-19. The final model included caregivers' prevention behavior, caregivers' anxiety for children's activities, children's lethargy, and children's inappropriate speech. The model was significantly associated with caregivers' fear of COVID-19 (p < 0.001); there were significant positive associations between caregivers' fear of COVID-19 and caregivers' preventive behavior, caregivers' anxiety about children's activities, and children's inappropriate speech (Table 4).

Step-Wise Regression Analyses on General Mental Health Problems

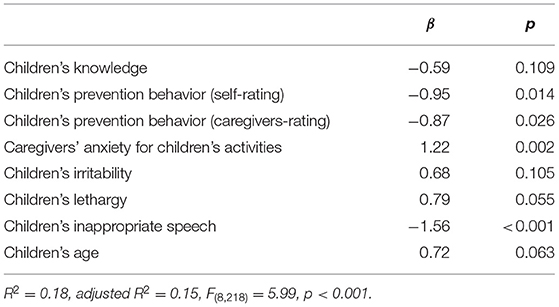

Table 5 shows the results of the step-wise regression analysis on children's depressive symptoms. The final model included children's knowledge, children's prevention behavior, as rated by both self the children themselves and the caregivers, caregivers' anxiety for children's activities, children's irritability, children's lethargy, children's inappropriate speech, and children's age, and the model was significantly associated with children's depressive symptoms (p < 0.001). In the model, children's depressive symptoms had a significant positive association with caregivers' anxiety about children's activities, and significant negative associations with children's preventive behaviors, as rated by both the children and caregivers, and children's inappropriate speech (Table 5).

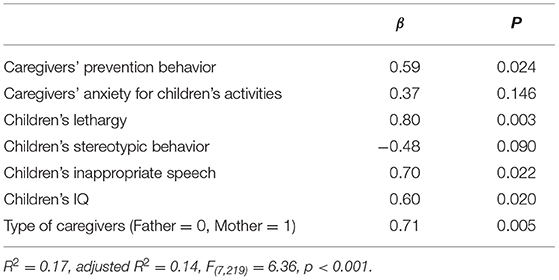

Table 6 shows the results of the step-wise regression analysis on caregivers' psychological distress. The final model included caregivers' prevention behavior, caregivers' anxiety for children's activities, children's lethargy, children's stereotypic behavior, children's inappropriate speech, children's IQ, and type of caregivers. The model was significantly associated with caregivers' psychological distress (p < 0.001). In the model, there were significant positive associations between caregivers' psychological distress and caregivers' preventive behavior, children's lethargy, children's inappropriate speech, children's IQ, and mother respondents (Table 6).

Correlational Analyses

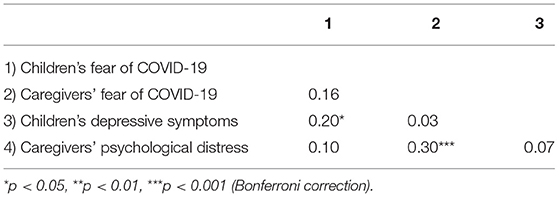

Table 7 shows Pearson's correlational coefficients among fears of COVID-19 and general mental health problems (i.e., depressive symptoms and psychological distress) in children and caregivers. There were significant positive correlations between fears of COVID-19 and general mental health problems in both children and caregivers. However, there were no significant correlations of fears of COVID-19 and general mental health between children and caregivers.

Table 7. Pearson's correlation among fears of COVID-19 and general mental health problems in children with neurodevelopmental disorder and their caregivers.

Children's Knowledge About COVID-19 and Preventive Behavior for COVID-19 Infection

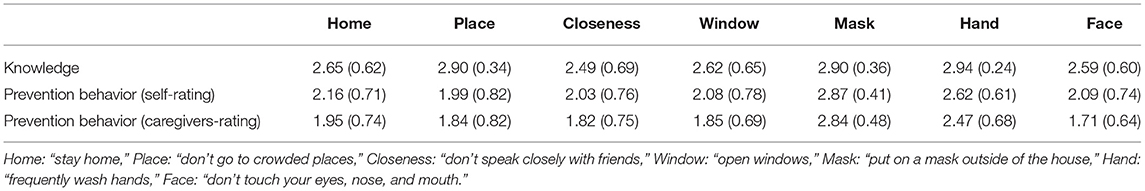

Table 8 shows means and standard deviations of children's knowledge about COVID-19 and preventive behavior for COVID-19 infection. One-way ANOVAs showed significant main effects of items (children's knowledge about COVID-19: F(6, 1356) = 31.44, p < 0.001; children's preventive behavior rated by the children: F(6, 1344) = 60.72, p < 0.001; children's preventive behavior rated by caregivers: F(6, 1326) = 101.46, p < 0.001). In terms of children's knowledge about COVID-19, Bonferroni tests showed that scores were significantly higher on “don't go to crowded places,” “put on a mask outside of the house,” and “wash hands frequently” than on the other items. For children's preventive behaviors rated by both the children and caregivers, Bonferroni tests showed that scores were significantly higher on “put on a mask outside of the house,” and “wash hands frequently” than on other items. Bonferroni tests also showed that scores were significantly higher on “put on a mask outside of the house” than “wash hands frequently.” In addition, Bonferroni tests showed that scores were significantly higher on “stay home” than “don't go to crowded places.”

Table 8. Means (standard deviations) of children's knowledge about COVID-19 and prevention behavior for COVID-19 infection.

Discussion

We examined the association of mental health problems with preventive behavior and caregivers' anxiety in children with NDD and their caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. There were significant positive correlations between fear of COVID-19 and general mental health problems in children with NDD and their caregivers. Thus, we confirmed the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and general mental health problems in children with NDD and their caregivers. In addition, caregivers' anxiety about children's activities was positively associated with fear of COVID-19 in caregivers. Children have a low mortality risk of COVID-19 (2), and are not the main drivers of the pandemic (3). In spite of this evidence, most caregivers worried that their child would catch COVID-19 at school (5). Our results indicated that caregivers' fear stemmed from worry about the relationship between children's activity and COVID-19 infection.

Caregivers' anxiety about children's activities related to COVID-19 infection was positively associated with children's fear of COVID-19 and depressive symptoms. A previous study conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic indicated that caregivers' anxiety is associated with their children's anxiety (20–22). It is possible that children reflected caregivers' expressions of worry about the relationship between children's activity and COVID-19 infection. In addition, we hypothesized that caregivers' anxiety about children's activity might be related to over-involvement in children's preventive behavior. A systematic review showed that caregivers' over-involvement is associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms (37). Therefore, we suggest that mental health problems in children with NDD were affected by caregivers' expression of worry and over-involvement.

Children's preventive behavior was negatively associated with children's depressive symptoms, which indicates that children who acquired preventive behavior for COVID-19 tended to have lower depressive symptoms. Most children with NDD engaged in preventive behavior of “put on a mask outside of the house” and “wash hands frequently.” In schools, teachers have educated students on knowledge and preventive behavior for COVID-19 (17), and educational methods have been developed for children with NDD (15, 18). Our results support the idea that these practices mitigated children's general mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In contrast to children's preventive behavior, caregivers' preventive behavior was positively associated with caregivers' fear of COVID-19 and psychological distress. Inconsistent results were reported in a previous study in which preventive behavior was associated with better mental health (16). Japanese people had been required to engage in preventive behavior for more than half a year at the time of the survey. The number of cases was small in Fukui Prefecture during the survey period (24). Most people did not strictly engage in preventive behaviors such as “stay home.” We hypothesize that “excessive” preventive behavior was a burden for caregivers, which might have exacerbated mental health problems.

Children's IQ was negatively associated with children's fear of COVID-19, whereas it was positively associated with caregivers' psychological distress. Children with high IQs can effectively acquire knowledge about COVID-19 and can freely behave independently of caregivers, which might reduce children's fear of COVID-19 and might enhance caregivers' psychological distress. In addition, children's inappropriate speech was negatively associated with children's depressive symptoms, whereas it was positively associated with caregivers' psychological distress. One item, “talks excessively,” is included in inappropriate speech (32), and it is also one of the factors that can increase the spread of COVID-19 infection. Thus, we considered that caregivers of children with a higher score of inappropriate speech worried that the children would spread COVID-19. On the other hand, we speculated that a higher score for inappropriate speech represented a low level of worry about COVID-19 infection; thus, children with higher scores might not feel burdened.

In the statistical analysis, the fears of COVID-19 and general mental health problems were used as dependent variables. However, the associations between the dependent and independent variables were unclear. Therefore, longitudinal data are necessary to test the causality. Moreover, since the COVID-19 pandemic is on-going, it would difficult for the future studies to confirm the present findings. We expect clinicians to report their practices regarding awareness of preventive behavior and interventions for caregivers, which might partially support the present findings. In addition, most variables were based on self-reported scales; thus, the findings are biased. Especially, preventive behavior regarding COVID-19 might have the tendency to be scored higher owing to government recommendations and media information regarding COVID-19. In the all models of the step-wise regression analyses, the coefficients of determination were <0.20, which indicates that the other variable might more strongly explain the fears of COVID-19 and general mental health problems. Furthermore, the results might not be unique to children with NDD and their caregivers because only clinical data were available. We acquired patient- and caregiver-data from a single clinic. Therefore, our results are not representative of children with NDD and their caregivers. Additionally, patients with severe mental health problems could not participated in this study. Thus, the present findings were based on the data from participants who could respond to the questionnaire. Finally, the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic is fluctuating and differs across countries and regions. It is, thus, difficult to obtain representative results; Fukui Prefecture is a provincial area, and the number of cases was small during the survey period (24). However, despite the above limitations, we believe that our results are valuable as it analyzes these issues in the context of the pandemic.

We examined the association of mental health problems with preventive behavior and caregivers' anxiety in children with NDD and their caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Caregivers' anxiety about children's activities was positively associated with caregivers' and children's fears of COVID-19 and children's depressive symptoms. These results suggest that caregivers' fear of COVID-19 stems from worry about the relationship between children's activity and COVID-19 infection and that children might reflect caregivers' expressions of concern. Children's preventive behavior was negatively associated with children's depressive symptoms. In schools and clinics, practitioners educate children to engage in preventive behavior against COVID-19. Our results support the effectiveness of such practices in mitigating general mental health problems in children with NDD.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the author, and approval by the ethics committee of Shitennoji University. The data are not publicly available because no informed consent was given by the participants for open data sharing. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Kota Suzuki, a3Quc3V6dWtpQGhvdG1haWwuY28uanA=; a3RzdXp1a2lAc2hpdGVubm9qaS5hYy5qcA==.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of Shitennoji University. The caregivers provided written informed consent before participation, and informed consent was obtained from all children.

Author Contributions

KS contributed to the study design, interpreting the data, and writing the manuscript. MH contributed to the study design, data collection, interpreting the data, and writing the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was partly supported by a group research grant from Shitennoji University and a Grant-in-Aid (KAKENHI) for Scientific Research (C) (Grant No. 19K03304) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We give special thanks to Ms. Riko Horiuchi, Ms. Miu Ichimura (Shitennoji University), and the staffs of the Hiratani Child Development Clinic for their assistance.

References

1. Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 89:531–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048

2. Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Beltekian D, Mathieu E, Hasell J, Macdonald B, et al. Mortality Risk of COVID-19. (2021). Available online at: https://ourworldindata.org/mortality-risk-covid (accessed May 21, 2021).

3. Ludvigsson JF. Children are unlikely to be the main drivers of the COVID-19 pandemic–a systematic review. Acta Paediatr. (2020) 109:1525–30. doi: 10.1111/apa.15371

4. Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Erhart M, Devine J, Schlack R, Otto C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2021) 25:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01726-5

5. Jeffs E, Lucas N, Walls T. CoVID-19: Parent and caregiver concerns about reopening New Zealand schools. J Paediatr Child Health. (2021) 57:403–8. doi: 10.1111/jpc.15234

6. Lee YC, Yang HJ, Chen VCH, Lee WT, Teng MJ, Lin CH, et al. Meta-analysis of quality of life in children and adolescents with ADHD: By both parent proxy-report and child self-report using PedsQL™. Res Dev Disabil. (2016) 51:160–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.11.009

7. Lai M.-C., Kassee C, Besney R, Bonato S, Hull L, et al. Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6:819–29. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30289-5

8. Cheung K, Aberdeen K, Ward MA, Theule J. Maternal depression in families of children with ADHD: A meta-analysis. J Child Fam Stud. (2018) 27:1015–28. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1017-4

9. Schnabel A, Youssef GJ, Hallford DJ, Hartley EJ, McGillivray JA, Stewart M, et al. Psychopathology in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. Autism. (2020) 24:26–40. doi: 10.1177/1362361319844636

10. Nonweiler J, Rattray F, Baulcomb J, Happ, é F, Absoud M. Prevalence and associated factors of emotional and behavioural difficulties during COVID-19 pandemic in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Children. (2020) 7:128. doi: 10.3390/children7090128

11. Breaux R, Dvorsky MR, Marsh NP, Green CD, Cash AR, Shroff DM, et al. Prospective impact of COVID-19 on mental health functioning in adolescents with and without ADHD: protective role of emotion regulation abilities. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2021). doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13382. [Epub ahead of print].

12. Nuñez A, Le Roy C, Coelho-Medeiros ME, López-Espejo M. Factors affecting the behavior of children with ASD during the first outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurol Sci. (2021) 42:1675–8. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05147-9

13. Colizzi M, Sironi E, Antonini F, Ciceri ML, Bovo C, Zoccante L. Psychosocial and behavioral impact of COVID-19 in autism spectrum disorder: an online parent survey. Brain Sci. (2020) 10:341. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10060341

14. Bentenuto A, Mazzoni N, Giannotti M, Venuti P, de Falco S. Psychological impact of Covid-19 pandemic in Italian families of children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Res Dev Disabil. (2021) 109:103840. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103840

15. Shorey S, Lau LST, Tan JX, Ng ED, Ramkumar A. Families with children with neurodevelopmental disorders during COVID-19: a scoping review. J Pediatr Psychol. (2021) 46:514–25. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsab029

16. Yildirim M, Güler A. COVID-19 severity, self-efficacy, knowledge, preventive behaviors, and mental health in Turkey. Death Stud. (2020) 16:1–8. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1793434

17. Ministry of Education Culture Sports Science and Technology. 新型コロナウイルス感染症の予防 [Prevention for COVID-19]. (2020). Available online at: https://www.mext.go.jp/content/2020501-mext_kenshoku-000006975_5.pdf (accessed May 21, 2021).

18. Kawabe K, Hosokawa R, Nakachi K, Yoshino A, Horiuchi F, Ueno S, et al. Making brochure of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) for children with autism spectrum disorder and their family members. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2020) 74:498–9. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13090

19. Suzuki K, Kita Y, Kaga M, Takehara K, Misago C, Inagaki M. The association between children's behavior and parenting of caregivers: a longitudinal study in Japan. Front Public Health. (2016) 4:17. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00017

20. Lawrence PJ, Murayama K, Creswell C. Systematic review and meta-analysis: anxiety and depressive disorders in offspring of parents with anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2019) 58:46–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.07.898

21. Muris P, Steerneman P, Merckelbach H, Meesters C. The role of parental fearfulness and modeling in children's fear. Behav Res Ther. (1996) 34:265–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00067-4

22. Turner SM, Beidel DC, Costello A. Psychopathology in the offspring of anxiety disorders patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. (1987) 55:229–35. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.55.2.229

23. Johns Hopkins University. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE). (2021). Available online at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed May 21, 2021).

24. Fukui Prefecture. 新型コロナウイルス感染症のオープンデータを公開します [Open data of COVID-19]. (2021). Available online at: https://www.pref.fukui.lg.jp/doc/toukei-jouhou/covid-19.html (accessed May 21, 2021).

25. Ministry of Health Labour Welfare. 新型コロナウイルス感染予防のために [For COVID-19 Prevention]. (2020). Available online at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/covid-19/kenkou-iryousoudan.html (accessed May 21, 2021).

26. Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. Int J Ment Health. (2020) 27:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8

27. Wakashima K, Asai K, Kobayashi D, Koiwa K, Kamoshida S, Sakuraba M. The Japanese version of the Fear of COVID-19 scale: reliability, validity, and relation to coping behavior. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0241958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241958

28. Murata T. Examination of birleson depression scale for school children in Japan. Jpn J Latest Psychiatry. (1996) 1:131–8.

29. Birleson P. The validity of depressive disorder in childhood and the development of a self-rating scale: a research report. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (1981) 22:73–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1981.tb00533.x

30. Furukawa TA, Kessler RC, Slade T, Andrews G. The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian national survey of mental health and well-being. Psychol Med. (2003) 33:357–62. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006700

31. Furukawa TA, Kawakami N, Saitoh M, Ono Y, Nakane Y, Nakamura Y, et al. The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the world mental health survey Japan. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. (2008) 17:152–8. doi: 10.1002/mpr.257

32. Aman MG, Singh NN, Stewart AW, Field CJ. The aberrant behavior checklist: a behavior rating scale for the assessment of treatment effects. Am J Ment Defic. (1985) 89:485–91.

33. Ono Y. Factor validity and reliability for the aberrant behavior checklist-community in a Japanese population with mental retardation. Res Dev Disabil. (1996) 17:303–9. doi: 10.1016/0891-4222(96)00015-7

34. R Core Team. R-3.5.2 for Windows. (2021). Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/3.5.2/ (accessed May 21, 2021).

35. Kita Y, Inoue Y. The direct/indirect association of ADHD/ODD symptoms with self-esteem, self-perception, and depression in early adolescents. Front Psychiatry. (2017) 8:137. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00137

36. Suzuki K, Hiratani M, Mizukoshi N, Hayashi T, Inagaki M. Family resilience elements alleviate the relationship between maternal psychological distress and the severity of children's developmental disorders. Res Dev Disabil. (2018) 83:91–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2018.08.006

Keywords: coronavirus disease 2019, preventive behavior, caregivers' anxiety, neurodevelopmental disorder, fears of COVID-19

Citation: Suzuki K and Hiratani M (2021) The Association of Mental Health Problems With Preventive Behavior and Caregivers' Anxiety About COVID-19 in Children With Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 12:713834. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.713834

Received: 24 May 2021; Accepted: 17 June 2021;

Published: 16 July 2021.

Edited by:

Ylva Svensson, University West, SwedenReviewed by:

Cheng-Fang Yen, Kaohsiung Medical University, TaiwanZixin Lambert Li, Stanford University, United States

Copyright © 2021 Suzuki and Hiratani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kota Suzuki, a3Quc3V6dWtpQGhvdG1haWwuY28uanA=; a3RzdXp1a2lAc2hpdGVubm9qaS5hYy5qcA==

Kota Suzuki

Kota Suzuki Michio Hiratani2

Michio Hiratani2