- 1National Clinical Research Center for Mental Disorders, and Department of Psychiatry, The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, China

- 2Mental Health Institute of Central South University, China National Technology Institute on Mental Disorders, Hunan Technology Institute of Psychiatry, Hunan Key Laboratory of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hunan Medical Center for Mental Health, Changsha, China

- 3Affiliated WuTaiShan Hospital of Medical College of Yangzhou University, Yangzhou Mental Health Center, Yangzhou, China

- 4Zhumadian Psychiatric Hospital, Zhumadian, China

Background: Previous studies have shown that childhood maltreatment (CM) is closely associated with social support in the general population. However, little is known about the associations of different types of CM with social support in Chinese patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), which was the goal of the current study.

Methods: One hundred and sixty-six patients with moderate-to-severe MDD were enrolled. Participants were assessed by the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-28 item Short Form, Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS), the 24-item Hamilton rating scale for depression, and the 14-item Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale. Correlation analysis and Hierarchical multiple linear regression analysis were adopted to investigate associations of types of CM with social support.

Results: (1) Physical neglect (PN) and emotional neglect (EN) were the most commonly reported types of CM in patients with MDD. (2) EN was the only type of CM significant in the regression models of the SSRS total score, the score of subjective support, and the score of utilization of support.

Limitations: The data of CM was collected retrospectively and recall bias may be introduced. Assessment of CM and social support were self-reported and could be influenced by the depression status.

Conclusion: In Chinese patients with MDD, PN and EN are the most prevalent types of CM. EN is the only type of CM associated with low social support in regression models, calling for special attention in the assessment and intervention of EN.

Introduction

Social support is the assistance or comfort from others that makes one person believe himself is a part of a social network, being valued, esteemed, loved, and cared for (1). Social support is associated with the development of depression (2). A high level of support helps individuals to cope with life stress and acts as a protective factor for depression (3). Childhood maltreatment (CM) is defined as a variety of adverse experiences of a child, including emotional abuse (EA), physical abuse (PA), sexual abuse (SA), emotional neglect (EN), and physical neglect (PN) (4, 5). CM also brings detrimental consequences for the mental health of survivors (5, 6), containing earlier onset (7), poorer treatment response (8), and higher risk of relapse (9) of major depressive disorder (MDD).

Considering the both vital role of social support and CM on depression, we were curious about the association of CM with social support. Current literature on this topic is mainly focused on the general population. Generally, CM is found to be correlated with lower levels of social support (10, 11). According to prospective studies, maltreated children are more likely to report lower social support in adulthood (12) and unstable support across the life span (13) compared to those without a history of CM. Specific to types of CM, PA and EA are reported to be correlated with lower support in early life (14) and midlife (15) in the USA. Survivors with childhood neglect have lower social support from their families in Australia (16). In China, Wang et al. found five types of CM are all correlated with social support in adolescents (17) while only EA and PN are related to total social support and objective support, respectively, in a community sample (18).

Up to now, there is no study to investigate this topic in Chinese patients with MDD. As a common, severe, and debilitating neuropsychiatric disorder, MDD will rank first place in the global disease burden by 2030 (19). Investigating associations of CM with social support in MDD may be instructive to the improvement of social support and facilitate the prevention and recovery of depression. Thus, the main objective of the current study is to examine the associations of different types of CM with social support in Chinese patients with MDD. Based on the above findings, we hypothesized that all types of CM are associated with social support.

Materials and Methods

Data for this study were drawn from the project of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function and magnetic resonance imaging study of trauma-related depression (registration number: ChiCTR1800014591). A detailed description of the design of this project was presented by the previous articles (20, 21).

Participants

The study enrolled one hundred and sixty-six patients with MDD from the Zhumadian Psychiatric Hospital, Henan, China, from January 2013 to December 2018. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age years ≥ eighteen. (2) diagnosed by two psychiatrists according to the Structured Clinical Interview for the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). (3) total score of a 24-item Hamilton rating scale for depression (HAMD-24) > nineteen points. Patients would be excluded if they were satisfied with any of the following criteria: (1) obvious suicide ideation or suicide attempts. (2) current or lifetime severe physical condition. (3) history of any other DSM-IV psychiatric disorders. (4) history of substance dependence or abuse. (5) in the perinatal period.

All participants gave written informed consent. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Zhumadian Psychiatric Hospital and the ethics committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University.

Measures

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-28 Item Short Form (CTQ-SF)

The CTQ-SF contains 28 self-report items, which are scaled by a five-point Likert ranging from never true (one point) to very often true (five points). Psychiatrists often use this scale to evaluate the five types of CM. Generally, EA refers to the inappropriate emotional response to the child's behavior such as belittling, rejection, and terrorizing (22). PA assesses the violence toward the body of the child by families or caregivers. SA represents sexual contact or forces the child to watch pornography. EN means the deficiency of emotional support (23) and PN is the failure to meet the basic material needs of the child (24). Subjects with CM were defined as ever suffering at least one kind of CM according to the cut-off scores as follows: EA ≥ 13, PA ≥ 10, SA ≥ 8, EN ≥ 15, and PN ≥ 10. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of CTQ-SF were proved to be good (25).

Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS)

The SSRS is a self-report questionnaire in Chinese to assess psychological, objective, and utilization of support. This scale contains ten items and can be divided into three subscales: objective support (three items related to living conditions in the past year, and sources of economical and psychological support in urgent situations), subjective support (four items associated with relationships with colleagues and neighbors, support from family, and numbers of friends who can provide support), and utilization of support (three items in regards to the manner one talks and asks for help when encountering troubles, and the positivity of participation in group activities) (26). The SSRS has good validity and reliability (27, 28).

HAMD-24

The HAMD-24 is commonly used by the clinician to rate depressive symptoms. This scale consists of 24 items and the total score range from 0 to 75 points (29). The cut-off scores of HAMD-24 are 8, 20, and 35, which means mild, moderate, and severe depression respectively (30).

14-Item Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAMA-14)

The HAMA-14 is one of the most widely used rating scales for the severity of anxious symptoms (31). As a clinician-rated scale, it consists of 14 items. Each item is scaled by a five-point Likert ranging from not present (zero point) to severe (four points). This scale has been demonstrated to have good reliability and validity (32).

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed on IBM SPSS Statistics 20. Continuous variables with normal distribution were shown as mean ± standard deviation. Those with skewed distribution were shown as median (interquartile range). Pearson and Spearman correlation and partial correlation analysis were performed to assess the relationships between sociodemographic variables, clinical variables, and the SSRS total and subscale scores. Sociodemographic variables related to the SSRS total and subscale scores, respectively, were controlled in Pearson partial correlation analysis. Sociodemographic and clinical variables associated with the SSRS total and subscale scores, respectively, were controlled in Spearman partial correlation analysis. To investigate which associated variables could explain the variation of social support, hierarchical multiple linear regression analysis was adopted. The sociodemographic variables which had statistical significance in correlation analysis were entered in the first step (model 1), and then scores of HAMD-24 or associated types of CM were entered in the second step (model 2). Statistical significance was set as a two-tailed P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Sociodemographic Information and Clinical Information

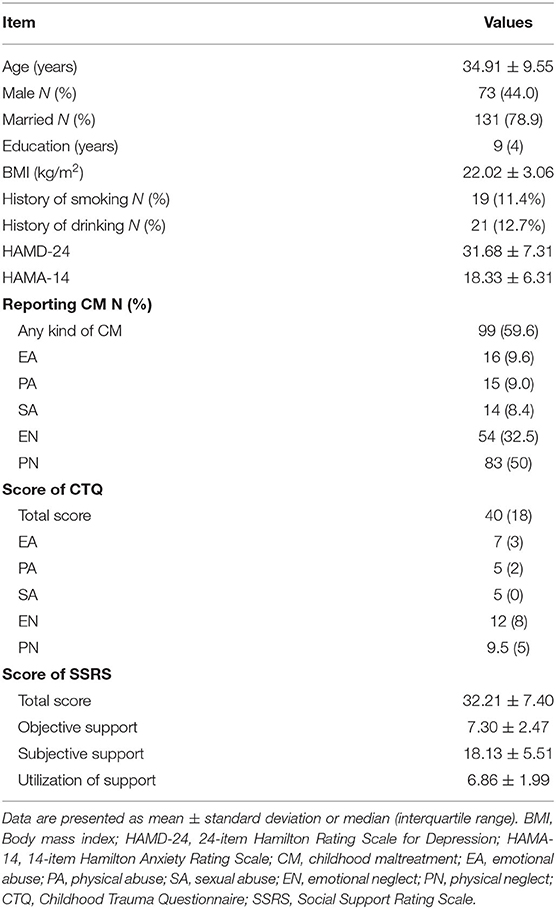

As shown in Table 1, patients aged 35 years nearly and the majority of them were married. About ten percent of participants reported a history of smoking and drinking. More than half of patients reported having experienced at least one type of CM. PN and EN were the most prevalent two types of CM.

Correlations of Sociodemographic and Clinical Variables With the SSRS Total and Subscale Scores

The results of correlation analyses are shown in Table 2. Age was related to the score of objective support, the score of subjective support, and the SSRS total score (r = 0.210, 0.375, and 0.379, respectively). Education and the total score of HAMD-24 were correlated with the score of objective support (r = 0.178 and −0.214, respectively). Sex and marriage were associated with the score of subjective support (r = 0.163 and −0.217, respectively).

Table 2. Correlations of sociodemographic and clinical information with the SSRS total and subscale scores.

Meanwhile, EA, EN, and PN were associated with SSRS total score and the score of subjective support (all P < 0.05). Only EN was related to the score of utilization of support (r = −0.209, P < 0.01). None of the types of CM was correlated with the score of objective support.

Hierarchical Multiple Linear Regression Analysis of the SSRS Total and Subscale Scores

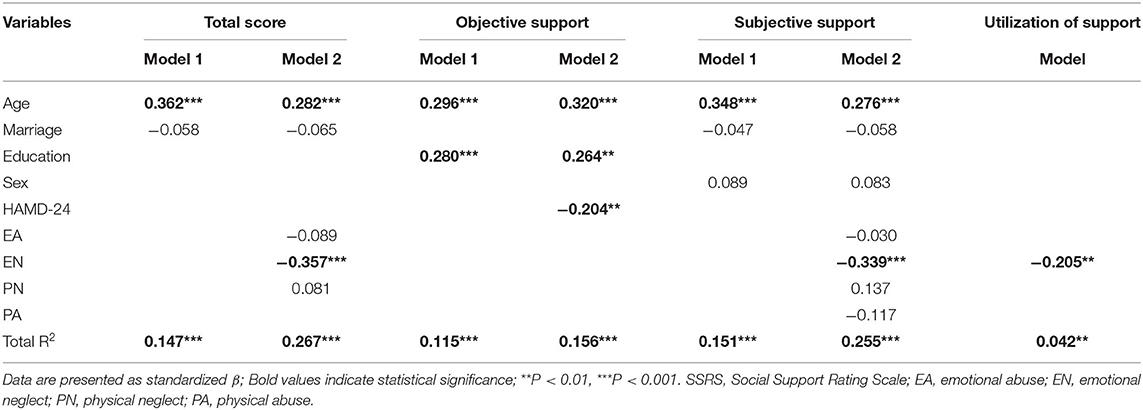

Table 3 reveals the results of the regression analyses. Age was significant in the final regression models of the SSRS total score, the score of objective support, the score of subjective support (standardized β = 0.282, 0.320, and 0.276, respectively). Education and the total score of HAMD-24 could explain the variation of the score of objective support (standardized β = 0.264 and −0.204, respectively).

EN had statistical significance in the final regression models of SSRS total score, the score of subjective support, and the score of utilization of support (standardized β = −0.357, −0.339, and −0.205, respectively; R2 = 0.267, 0.255, and 0.042, respectively).

Discussion

To the best knowledge, the present study is the first one to investigate the associations of different types of CM with social support in Chinese patients with MDD. We found that in Chinese patients with MDD: (1) EN and PN were the most prevalent two types of CM. (2) in regression models, only EN was associated with social support. Our findings highlight the significance of EN in impairing social support in Chinese patients with MDD.

High Prevalence of CM in Patients With MDD

In the present study, the prevalence of CM is lower than that in a German MDD sample (74.7%) (33), while higher than that in another Chinese MDD sample (48.8%) (34). Meanwhile, in this Chinese study, they reported higher prevalence of PN, EN, and EA in the MDD group among types of CM (34), which is consistent with us. It indicates the three types of CM possibly have close relationships with MDD, different from foreign studies holding that abuse is more related to depression (23).

EN Is Associated With Low Social Support in Patients With MDD

In China, about twenty-six percent of children ever experience childhood neglect, which is higher compared with other countries (35) and leads to large economic losses (35). However, little do we know about the impact of childhood neglect on the mental health of the Chinese (36). In contrast to our hypothesis, we reported only a negative association of EN with social support, which is consistent with the existing literature. A study examining the influence of CM on the adaption of soldiers to army life found that EN has a special negative impact on the access to social support from units (37). Harmer et al. (16) investigated 46 adults recovering from addiction and reported that severer neglect is associated with lower social support from the family in Australia.

The exact mechanisms under the association of EN with social support were unknown. We supposed the probable reasons are as follows. Firstly, EN was one of the most prevalent types of CM in this study, which makes it easier to have a relationship with social support. In addition, the correlated coefficients of EN with social support were the highest among the five types of CM, making the relationships between other types of CM and social support are covered by EN. Moreover, the experience with EN makes one person is not good at expressing emotion (38) and feel not being loved, valued, and cared for, which lets him hold that other people will refuse him and tend to less utilize social support. Meanwhile, survivors of EN have deficits in the development of intimate relationships (39), resulting in a weak supportive network insufficient for them to use. Finally, there may exist a mediator between EN and social support, such as attachment (40). According to Kapeleris and Paivio (38), EN is correlated with emotional competence such as lack of sense of contentment, worth, and importance, which contributes to insecure attachment styles leading to low trust in others and poor utilization of social support. The reason why EN was not associated with objective support was unclear. However, it indicates that the correlations of age, education, and severity of depression with objective support were more significant than EN in the sample of the present study.

Social support is associated with the elevated risk (2), severity (41–43), course (44), and outcomes (45) of depression, and even mediates the correlation of depression with suicidal ideation (46). The higher proportion of EN (47, 48) and its significant association with social support indicate that it should be taken into consideration in studies involved with social support in patients with MDD. Psychotherapy mitigating the potentially detrimental effects of EN on social support may be effective in the prevention and recovery of depression.

Limitations

Despite the advantages of this study, several limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. Firstly, the data of CM was collected retrospectively, which could induce recall bias in the assessment. Prospective research should be considered in the future. Secondly, CTQ-SF and SSRS are self-report scales vulnerable to subjective effects, especially in patients with MDD. Depressed patients tend to exaggerate their adverse experiences in childhood and misjudge social support in the present life. Thirdly, variables such as family structure, economic status, and individual occupations correlated with social support were failed to be enrolled and controlled in the current study, which should be considered in the future. Finally, the explanatory effects of the regression models on social support are relatively unsatisfactory. Future studies should include more related variables to build models with better effects.

Conclusions

PN and EN are the most prevalent types of CM in Chinese patients with MDD. EN is the only type of CM related to social support in regression analyses. Studies associated with the social support system in Chinese patients with MDD in the future should take the assessment of EN into account. Moreover, developing special interventions to EN may help to improve social support and contribute to the mental health of Chinese patients with MDD.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Zhumadian Psychiatric Hospital and the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

LL and BL co-designed the topic. MW, XL, JS, QD, LZ, JL, YJ, PW, HG, FZ, YZ, and BL are responsible for participant recruitment and data collection. XQ undertook the statistical analyses and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. BL contributed substantial revisions to the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Science and Technologic Program of China (2015BAI13B02), the Defense Innovative Special Region Program (17-163-17-XZ-004-005-01), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81171286, 91232714, and 81601180). The funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the data, preparation and approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer LN declared a shared affiliation with several of the authors XQ, MW, XL, JS, QD, LZ, JL, YJ, BL, YZ and LL to the handling editor at the time of the review.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants for participating in this study.

References

1. Cobb S. Presidential Address-1976. social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom Med. (1976) 38:300–14. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003

2. Grey I, Arora T, Thomas J, Saneh A, Tohme P, Abi-Habib R. The role of perceived social support on depression and sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 293:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113452

3. Lagdon S, Ross J, Robinson M, Contractor AA, Charak R, Armour C. Assessing the mediating role of social support in childhood maltreatment and psychopathology among college students in Northern Ireland. J Interpers Violence. (2021) 36:1–25. doi: 10.1177/0886260518755489

4. Xie P, Wu K, Zheng Y, Guo Y, Yang Y, He J, et al. Prevalence of childhood trauma and correlations between childhood trauma, suicidal ideation, and social support in patients with depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia in southern China. J Affect Disord. (2018) 228:41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.011

5. Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. (2009) 373:68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7

6. Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, Anda RF. Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: results from the adverse childhood experiences study. Am J Psychiatry. (2003) 160:1453–60. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1453

7. Nelson J, Klumparendt A, Doebler P, Ehring T. Childhood maltreatment and characteristics of adult depression: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. (2017) 210:96–104. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.180752

8. Nanni V, Uher R, Danese A. Childhood maltreatment predicts unfavorable course of illness and treatment outcome in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. (2012) 169:141–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020335

9. Opel N, Redlich R, Dohm K, Zaremba D, Goltermann J, Repple J, et al. Mediation of the influence of childhood maltreatment on depression relapse by cortical structure: a 2-year longitudinal observational study. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6:318–26. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30044-6

10. Punamäki RL, Komproe I, Qouta S, El-Masri M, de Jong JT. The deterioration and mobilization effects of trauma on social support: childhood maltreatment and adulthood military violence in a Palestinian community sample. Child Abuse Negl. (2005) 29:351–73. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.10.011

11. Su Y, D'Arcy C, Meng X. Social support and positive coping skills as mediators buffering the impact of childhood maltreatment on psychological distress and positive mental health in adulthood: analysis of a national population-based sample. Am J Epidemiol. (2020) 189:394–402. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwz275

12. Sperry DM, Widom CS. Child abuse and neglect, social support, and psychopathology in adulthood: a prospective investigation. Child Abuse Negl. (2013) 37:415–25. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.006

13. Horan JM, Widom CS. From childhood maltreatment to allostatic load in adulthood: the role of social support. Child Maltreat. (2015) 20:229–39. doi: 10.1177/1077559515597063

14. Crouch JL, Milner JS, Thomsen C. Childhood physical abuse, early social support, and risk for maltreatment: current social support as a mediator of risk for child physical abuse. Child Abuse Negl. (2001) 25:93–107. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00230-1

15. Ebbert AM, Infurna FJ, Luthar SS, Lemery-Chalfant K, Corbin WR. Examining the link between emotional childhood abuse and social relationships in midlife: the moderating role of the oxytocin receptor gene. Child Abuse Negl. (2019) 98:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104151

16. Harmer ALM, Sanderson J, Mertin P. Influence of negative childhood experiences on psychological functioning, social support, and parenting for mothers recovering from addiction. Child Abuse Negl. (1999) 23:421–33. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00020-4

17. Wang S, Xu H, Zhang S, Yang R, Li D, Sun Y, et al. Linking childhood maltreatment and psychological symptoms: the role of social support, coping styles, and self-esteem in adolescents. J Interpers Violence. (2020) 9:1–31. doi: 10.1177/0886260520918571

18. Wang D, Lu S, Gao W, Wei Z, Duan J, Hu S, et al. The impacts of childhood trauma on psychosocial features in a Chinese sample of young adults. Psychiatry Investig. (2018) 15:1046–52. doi: 10.30773/pi.2018.09.26

19. Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. (2006) 3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442

20. Liu J, Dong Q, Lu X, Sun J, Zhang L, Wang M, et al. Exploration of major cognitive deficits in medication-free patients with major depressive disorder. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00836

21. Qin X, Sun J, Wang M, Lu X, Dong Q, Zhang L, et al. Gender differences in dysfunctional attitudes in major depressive disorder. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.541955

22. Sneddon H. The effects of maltreatment on children's health and well-being. Child Care in Practice. (2003) 9:236–49. doi: 10.1080/1357527032000167795

23. Negele A, Kaufhold J, Kallenbach L, Leuzinger-Bohleber M. Childhood trauma and its relation to chronic depression in adulthood. Depress Res Treat. (2015) 2015:650804–650804. doi: 10.1155/2015/650804

24. Infurna MR, Reichl C, Parzer P, Schimmenti A, Bifulco A, Kaess M. Associations between depression and specific childhood experiences of abuse and neglect: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2016) 190:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.006

25. Fu W, Yao S, Yu H, Zhao X, Li R, Li Y, et al. Initial reliability and validity of childhood trauma questionnaire (CTQ-SF) apllied in Chinese college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. (2005) 13:40–2. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2005.01.012

26. Sun J, Sun R, Jiang Y, Chen X, Li Z, Ma Z, et al. The relationship between psychological health and social support: evidence from physicians in China. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228152

27. Xiao S. The theoretical basis and research application of “social support rating scale”. J Clin Psychiatry. (1994) 4:98–100.

28. Yang G, Feng Z, Xia B, Zhong T, Liu Y, Wang T, et al. The reliability, validity and national norm of social support scale in servicemen. Chin Ment Health J. (2006) 20:309–12.

29. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, et al. The 16-item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. (2003) 54:573–83. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01866-8

30. Pan S, Liu ZW, Shi S, Ma X, Song WQ, Guan GC, et al. Hamilton rating scale for depression-24 (HAM-D(24)) as a novel predictor for diabetic microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Psychiatry Res. (2017) 258:177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.07.050

31. Thompson E. Hamilton rating scale for anxiety (HAM-A). Occup Med. (2015) 65:601. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqv054

32. Maier W, Buller R, Philipp M, Heuser I. The hamilton anxiety scale: reliability, validity and sensitivity to change in anxiety and depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. (1988) 14:61–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90072-9

33. Dannehl K, Rief W, Euteneuer F. Childhood adversity and cognitive functioning in patients with major depression. Child Abuse Negl. (2017) 70:247–54. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.013

34. Yang S, Cheng Y, Mo Y, Bai Y, Shen Z, Liu F, et al. Childhood maltreatment is associated with gray matter volume abnormalities in patients with first-episode depression. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. (2017) 268:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2017.07.005

35. Fang X, Fry DA, Ji K, Finkelhor D, Chen J, Lannen P, et al. The burden of child maltreatment in China: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. (2015) 93:176–85C. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.140970

36. Pan J. Child neglect situation and intervention outlook in rural areas of China. Zhonghua yu fang yi xue za zhi [Chinese journal of preventive medicine]. (2015) 49:850–2.

37. Rosen LN, Martin L. Childhood antecedents of psychological adaptation to military life. Mil Med. (1996) 161:665–8. doi: 10.1093/milmed/161.11.665

38. Kapeleris AR, Paivio SC. Identity and emotional competence as mediators of the relation between childhood psychological maltreatment and adult love relationships. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. (2011) 20:617–35. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2011.595764

39. Berzenski SR. Distinct emotion regulation skills explain psychopathology and problems in social relationships following childhood emotional abuse and neglect. Dev Psychopathol. (2019) 31:483–96. doi: 10.1017/S0954579418000020

40. Struck N, Krug A, Feldmann M, Yuksel D, Stein F, Schmitt S, et al. Attachment and social support mediate the association between childhood maltreatment and depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. (2020) 273:310–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.04.041

41. Zlotnick C, Shea MT, Pilkonis PA, Elkin I, Ryan C. Gender, type of treatment, dysfunctional attitudes, social support, life events, and depressive symptoms over naturalistic follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. (1996) 153:1021–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.8.1021

42. Shao R, He P, Ling B, Tan L, Xu L, Hou Y, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety and correlations between depression, anxiety, family functioning, social support and coping styles among Chinese medical students. BMC psychol. (2020) 8:38–38. doi: 10.1186/s40359-020-00402-8

43. Mohd TAMT, Yunus RM, Hairi F, Hairi NN, Choo WY. Social support and depression among community dwelling older adults in Asia: a systematic review. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e026667. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026667

44. van den Brink RHS, Schutter N, Hanssen DJC, Elzinga BM, Rabeling-Keus IM, Stek ML, et al. Prognostic significance of social network, social support and loneliness for course of major depressive disorder in adulthood and old age. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2018) 27:266–77. doi: 10.1017/S2045796017000014

45. Leskela U, Rytsala H, Komulainen E, Melartin T, Sokero P, Lestela-Mielonen P, et al. The influence of adversity and perceived social support on the outcome of major depressive disorder in subjects with different levels of depressive symptoms. Psychol Med. (2006) 36:779–88. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007276

46. Nam EJ, Lee J-E. Mediating effects of social support on depression and suicidal ideation in older Korean adults with hypertension who live alone. J Nurs Res. (2019) 27:e20. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000292

47. Herzog JI, Schmahl C. Adverse childhood experiences and the consequences on neurobiological, psychosocial, and somatic conditions across the lifespan. Front Psychiatry. (2018) 9:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00420

Keywords: emotional neglect, social support, major depressive disorder, childhood maltreatment, Chinese

Citation: Qin X, Wang M, Lu X, Sun J, Dong Q, Zhang L, Liu J, Ju Y, Wan P, Guo H, Zhao F, Zhang Y, Liu B and Li L (2021) Childhood Emotional Neglect Is Associated With Low Social Support in Chinese Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 12:781738. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.781738

Received: 23 September 2021; Accepted: 08 November 2021;

Published: 02 December 2021.

Edited by:

Yuping Ning, Guangzhou Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Lu Niu, Central South University, ChinaTianmei Si, Peking University Sixth Hospital, China

Copyright © 2021 Qin, Wang, Lu, Sun, Dong, Zhang, Liu, Ju, Wan, Guo, Zhao, Zhang, Liu and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lingjiang Li, TExKMjkyMEBjc3UuZWR1LmNu; Bangshan Liu, YmFuZ3NoYW4ubGl1QGNzdS5lZHUuY24=

Xuemei Qin1,2

Xuemei Qin1,2 Qiangli Dong

Qiangli Dong Liang Zhang

Liang Zhang Jin Liu

Jin Liu Yumeng Ju

Yumeng Ju Yan Zhang

Yan Zhang Bangshan Liu

Bangshan Liu Lingjiang Li

Lingjiang Li