- 1MacDonald Franklin Operational Stress Injury Research Centre, London, ON, Canada

- 2Department of Psychology, Neuroscience and Behaviour, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 3Homewood Research Institute, Guelph, ON, Canada

- 4Department of Psychiatry, Western University, London, ON, Canada

- 5School of Psychology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 6Douglas Mental Health University Institute, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 7Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 8Department of Clinical Health Psychology, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

- 9Department of Psychiatry, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

- 10Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

- 11Deer Lodge Centre Operational Stress Injury Clinic, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

Objectives: The traumatic nature of high-risk military deployment events, such as combat, is well-recognized. However, whether other service-related events and demographic factors increase the risk of moral injury (MI), which is defined by consequences of highly stressful and morally-laden experiences, is poorly understood. Therefore, the objective of this study was to examine determinants of MI in Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) personnel.

Methods: Data were obtained from the 2018 Canadian Armed Forces Members and Veterans Mental Health Follow-up Survey (CAFVMHS; unweighted n = 2,941). To identify military characteristics, sociodemographic variables, and deployment-related factors associated with increased levels of MI, a series of multiple linear regressions were conducted across deployed and non-deployed groups.

Results: When all variables were considered among the deployed personnel, rank, experiencing military related sexual trauma, child maltreatment (i.e., physical abuse, emotional abuse and neglect), and stressful deployment experiences were significant predictors of increased MI total scores (β = 0.001 to β = 0.51, p < 0.05). Feeling responsible for the death of an ally and inability to respond in a threatening situation were the strongest predictors of MI among stressful deployment experiences. Within the non-deployed sample, experiencing military-related or civilian sexual trauma and rank were significant predictors of increased MI total scores (β = 0.02 to β = 0.81, p < 0.05).

Conclusion: Exposure to stressful deployment experiences, particularly those involving moral-ethical challenges, sexual trauma, and childhood maltreatment were found to increase levels of MI in CAF personnel. These findings suggest several avenues of intervention, including education and policies aimed at mitigating sexual misconduct, as well as pre-deployment training to better prepare military personnel to deal effectively with morally injurious experiences.

Introduction

Military service has been associated with an elevated risk of negative mental health outcomes including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, substance use, and suicidal behaviors globally (1–5). This finding holds in the Canadian context, with higher prevalence of mental disorders observed in Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) personnel compared to civilian populations (6, 7), with 44% of surveyed CAF members experiencing symptoms consistent with a depressive or anxiety- related disorder at some point between 2002 and 2018 (8).

Although stressful deployment experiences such as combat have been associated with increased negative mental health outcomes in military populations (1, 9), combat experiences are not the sole type of psychologically traumatic events military members may encounter. Exposure to stressful or difficult events with moral-ethical implications is also common (10–12), but the psychological distress associated with these experiences is less well understood. Therefore, it is critical to understand the pre-, peri- and post-deployment, as well as non-deployment experiences that are associated with moral injury in the CAF.

Moral injury (MI) refers to the psychological, spiritual, behavioral or social distress that follows from situations in which individuals have committed, witnessed, or failed to prevent acts that transgress one's personal moral beliefs (13, 14). These feelings of distress may include shame, guilt, anger, and disgust, which may be associated with acts perpetrated by the self, such as actions leading to loss of life, or acts perpetrated by others, including betrayal, witnessing inappropriate acts by colleagues, or inappropriate acts by individuals in positions of power (10–15). Morally injurious experiences, such as betrayal from a trusted peer, may prompt a variety of psychological, social, and behavioral consequences, including relational strain, fundamental shifts in core beliefs (e.g., beliefs about the world), spiritual/existential challenges, alterations in perceptions of the self, as well as feelings of guilt, shame or anger (10, 15, 16). Although evidence is currently limited, recent research indicates that potentially morally injurious experiences (PMIEs) are common, and may have a unique impact on post-deployment outcomes in military populations. A representative survey of United States (U.S.) military combat veterans found that approximately 25% of respondents reported witnessing transgressions of others, 25% reported experiencing betrayal during their careers, and 10% reported that they transgressed their personal morals (15). In a representative survey of CAF members deployed to the mission in Afghanistan, Nazarov et al. (11) found that over half of the population indicated experiencing at least one PMIE. The authors found that individuals indicating exposure to PMIEs were more likely to report experiencing past-year major depressive disorder (MDD) and past-year posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) while adjusting for other relevant variables such as age, sex, and deployment-related factors (11).

Although these findings provide evidence that certain PMIEs may increase the risk of negative mental health outcomes in deployed military members, there are specific limitations to the current body of research examining MI among military personnel. In the aforementioned study by Nazarov et al. (11), MI was not directly assessed using a validated measure; rather, mental health outcomes were assessed in relation to proxy deployment experiences used to indicate exposure to PMIEs (11). Wisco et al. (15) used the Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES) to assess MI, but because this study was conducted in a U.S. combat sample, the results may not generalize to the CAF due to cultural and structural differences between the two Armed Forces (15). Additionally, although both studies examined the impact that deployment PMIEs had on the development of other mental health disorders, the authors did not focus on factors that may increase the risk of development of MI among non-deployed personnel. Although this evidence suggests that PMIEs occur frequently during military combat and deployment operations, scant evidence exists regarding factors that may contribute to the development of MI in non-deployed CAF personnel. Understanding risk factors that contribute to the development of MI within both deployed and non-deployed CAF personnel is critical to appropriately target resilience-building interventions to mitigate development of MI.

Aims of the Study

The aim of this study was to identify the military, deployment, and sociodemographic factors that are associated with increased MI in a nationally representative sample of CAF personnel and veterans. We hypothesized that deployment experiences and childhood maltreatment variables will significantly predict elevated MI scores in CAF personnel.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Data Collection

Data were obtained from the 2018 Canadian Armed Forces Members and Veterans Mental Health Follow-up Survey (CAFVMHS)(17). The CAFVMHS used a longitudinal survey design to resample individuals who initially participated in the 2002 Canadian Community Mental Health Survey—Mental Health and Well-being—Canadian Forces (CCHS-CF) (9). 5,155 CAF Regular Force personnel participated in the CCHS-CF in 2002, and 4,299 individuals were eligible to be contacted for follow-up interview. The target sampling frame for CAFVMHS were individuals who had completed the CCHS-CF and were full-time Regular Force members at the time of 2002 administration. At the time of 2018 data collection, personnel could be actively serving or veterans.

Of those who participated in the 2002 CCHS-CF and were eligible for follow-up (n = 4,299), 2,941 individuals participated in the CAFVMHS. Longitudinal weights were then created to produce representative estimates of the target population in 2002 and rounded to the nearest base of twenty. Therefore, the weighted survey sample represents 18,120 active duty and 34,380 released CAF personnel from the 2002 survey. As our analyses aimed to determine independent risk factors for the development of MI, and morally injurious experiences may differ between deployed and non-deployed personnel, the data were split into two groups: ever deployed outside North America and never-deployed groups. Data collection was conducted by Statistics Canada between January and May of 2018 using computer-assisted personal interviews. Participation was voluntary, and all participants provided informed consent. All data were collected in accordance with Statistics Canada procedures and approved by relevant review boards. For more information regarding the CAFVMHS rationale and methodology, please refer to (17, 18).

Measures

Moral Injury

MI was evaluated using the Moral Injury Events Scale (19), which uses a six-point Likert scale to assess event experiences. Participants were provided a series of nine statements (e.g., “I am troubled by having witnessed others' immoral acts”) and were asked to indicate their level of agreement (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree). Of note, logic skipping, wherein a participant selecting strongly disagree for certain items automatically imputed strongly disagree for a subsequent item, was used during administration [for more information, please see (20)]. Mean MIES scores were calculated and used as an outcome variable in our models, with higher mean scores indicating increased endorsement of MI. Past research has shown that while it is not without limitations (20), the MIES has strong evidence for internal consistency reliability and convergent validity (19, 20).

Deployment Experiences

Deployment experiences (DEX) were captured using a survey module that evaluated lifetime exposure and exposure since 2002 to eight stressful deployment experiences using dichotomous (yes/no) scoring (e.g., “known someone seriously injured or killed”). These items were adapted by the Canadian Department of National Defense (DND) from the Combat Experiences Scale (21). The eight items were chosen by the initial survey developers from the original Combat Experiences Scale instrument based on conceptual considerations (11).

Child Maltreatment

Participants were asked to retrospectively recall types of childhood adversity that they had been exposed to before the age of sixteen. Childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, exposure to intimate partner violence, and neglect were captured using nine items that were adapted from the Childhood Experiences of Violence Questionnaire (22). This measure has been used previously in population-level research to assess degree/severity of exposure to childhood adversity (11, 23). Of note, childhood sexual trauma was removed from the multivariate models due it theoretically being captured as a sub-category of lifetime sexual trauma.

Lifetime Sexual Trauma

Participants were asked if they had ever experienced sexual trauma in their lifetime. Sexual trauma was endorsed if they answered yes to one or more of eight dichotomous questions (e.g., “unwanted touching”). Further questions probed whether the event occurred while at a CAF workplace, while on deployment, or whether it was perpetrated by a CAF member/DND employee (17). If the respondent answered yes to any of these questions, these events were coded as military-related sexual trauma. If not, they were coded as non-military-related sexual trauma.

Military Variables

Previous research has shown that certain military variables may be associated with the presence of MI (11). As such, military variables, including force type, service environment (Army, Navy or Air Force), rank (junior non-commissioned member, senior non-commissioned officer, junior officer, senior officer), and number of years in the military, were included as covariates in our analyses (17). A dichotomous deployment variable was used to split the sample into CAF members who had deployed outside of North America and those who had not previously deployed. Separate models were created for deployed and non-deployed samples to independently assess how deployment-related variables impacted the endorsement of MI.

Demographic Covariates

Based on previous research that has shown associations between certain sociodemographic factors and MI, we adjusted for marital status, age, sex, and highest level of completed education in our analyses (11, 15). These variables were measured by self-report.

Statistical Methods

First, we evaluated descriptive statistics across both samples, as well as simple linear regressions with MIES score as the outcome variable. Next, multiple linear regression models were conducted to assess military, deployment, and sociodemographic-related predictors of MI scores. Survey sample weights calculated by Statistics Canada were used in all analyses to ensure survey sample representativeness. Furthermore, to account for the complex survey design, confidence intervals were calculated using 500 bootstrapped weights provided by Statistics Canada. Based on Statistics Canada's vetting rules, reported frequencies used sample weights and were rounded on a base of twenty, with percentages calculated based on the weighted frequencies following rounding. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

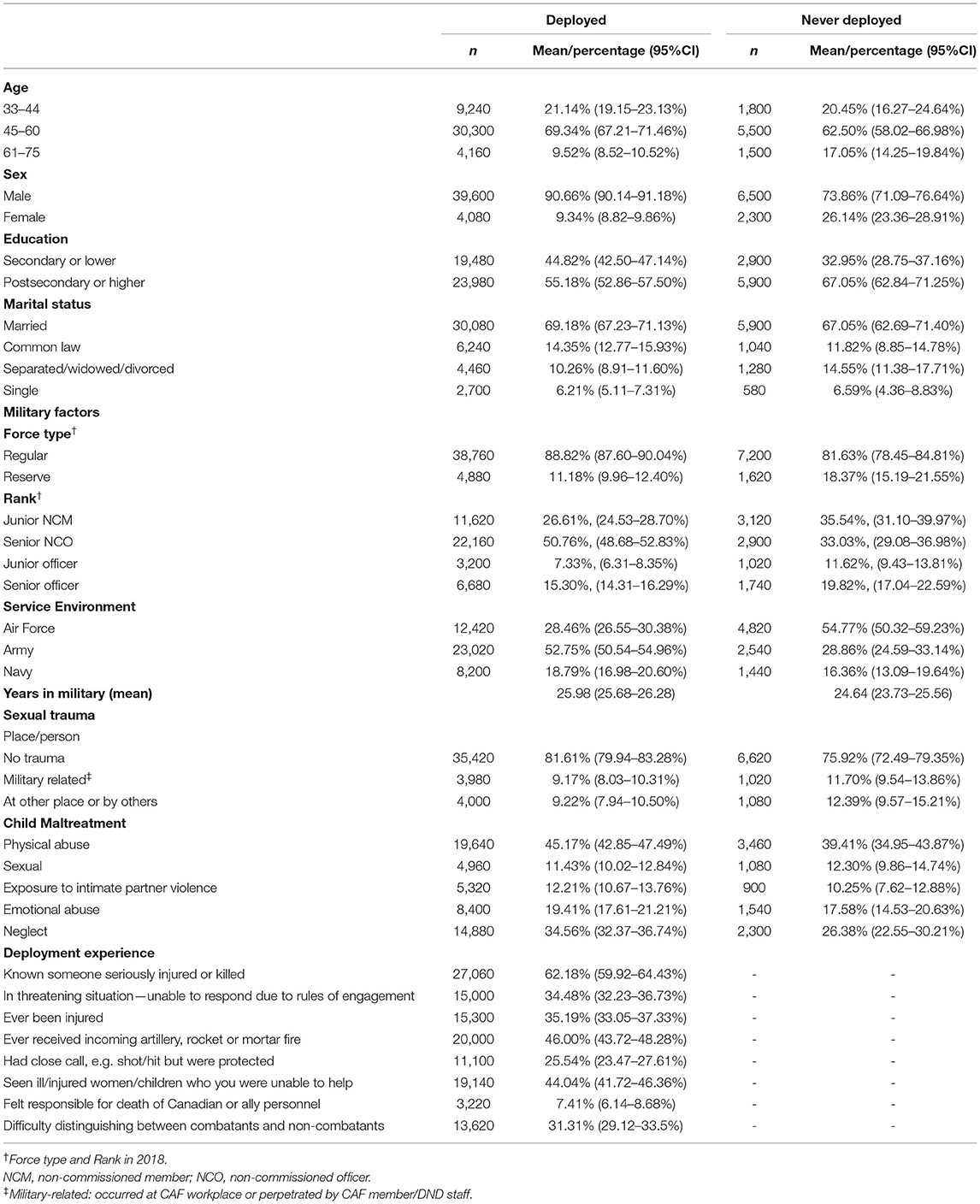

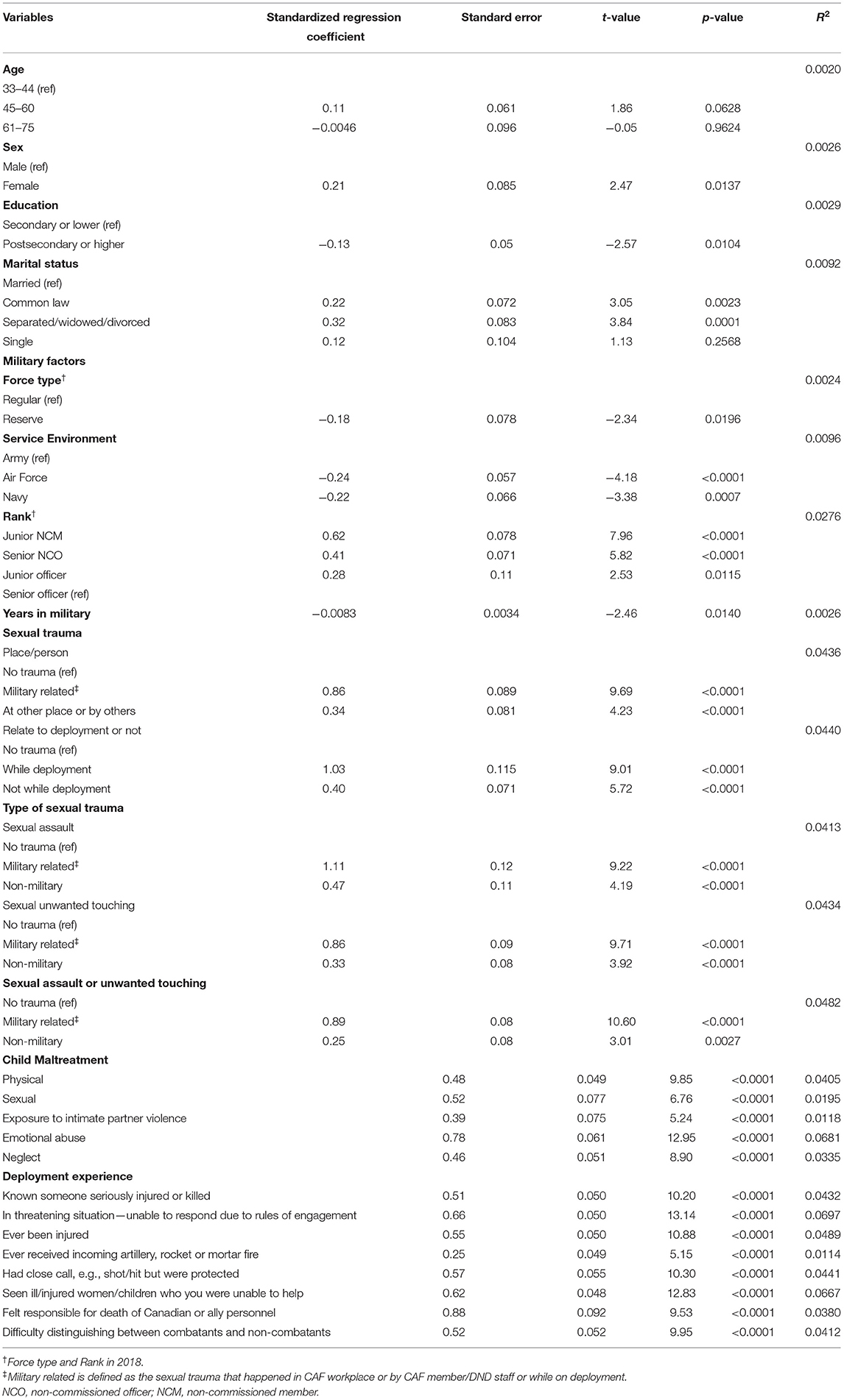

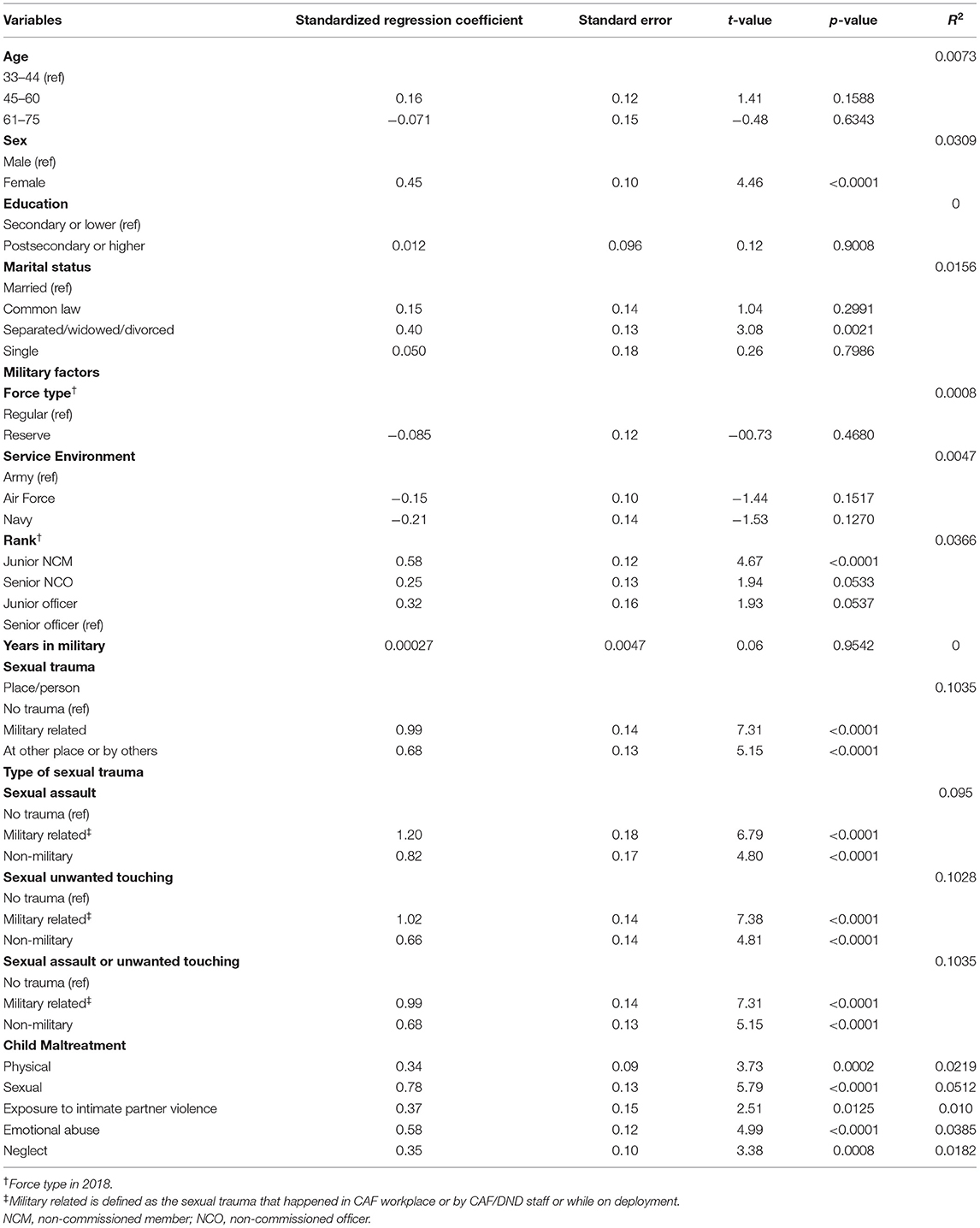

The unweighted sample of 2,941 total participants represented 18,120 active duty and 34,380 released CAF personnel from the original 2002 survey. Over 90% (n = 39,600) of the deployed sample and 74% (n = 6,500) of the non-deployed sample were male. The majority of the deployed (69%, n = 30,300) and non-deployed (62%, n = 5,500) personnel were between the ages of 45–60 years at the time of the 2018 survey administration. Among those who deployed, stressful deployment experiences were commonly reported. Specifically, 62% endorsed knowing someone who had been seriously injured or killed, 46% had ever received incoming artillery, rocket or mortar fire, and 44% reported seeing injured or ill women or children they were unable to help (Table 1). Simple linear regressions with MIES total score as the outcome variable among deployed and non-deployed samples are displayed in Tables 2, 3, respectively. Force element (i.e., Army, Navy or Air Force) was a statistically significant predictor of MIES score in the deployed sample, though not in the non-deployed sample. Rank was a statistically significant predictor in both deployed and non-deployed samples.

Table 2. Simple linear regressions predicting MIES scores among deployed CAF personnel (weighted n = 43,700).

Table 3. Simple linear regressions predicting MIES scores among non-deployed CAF personnel (weighted n = 8,800).

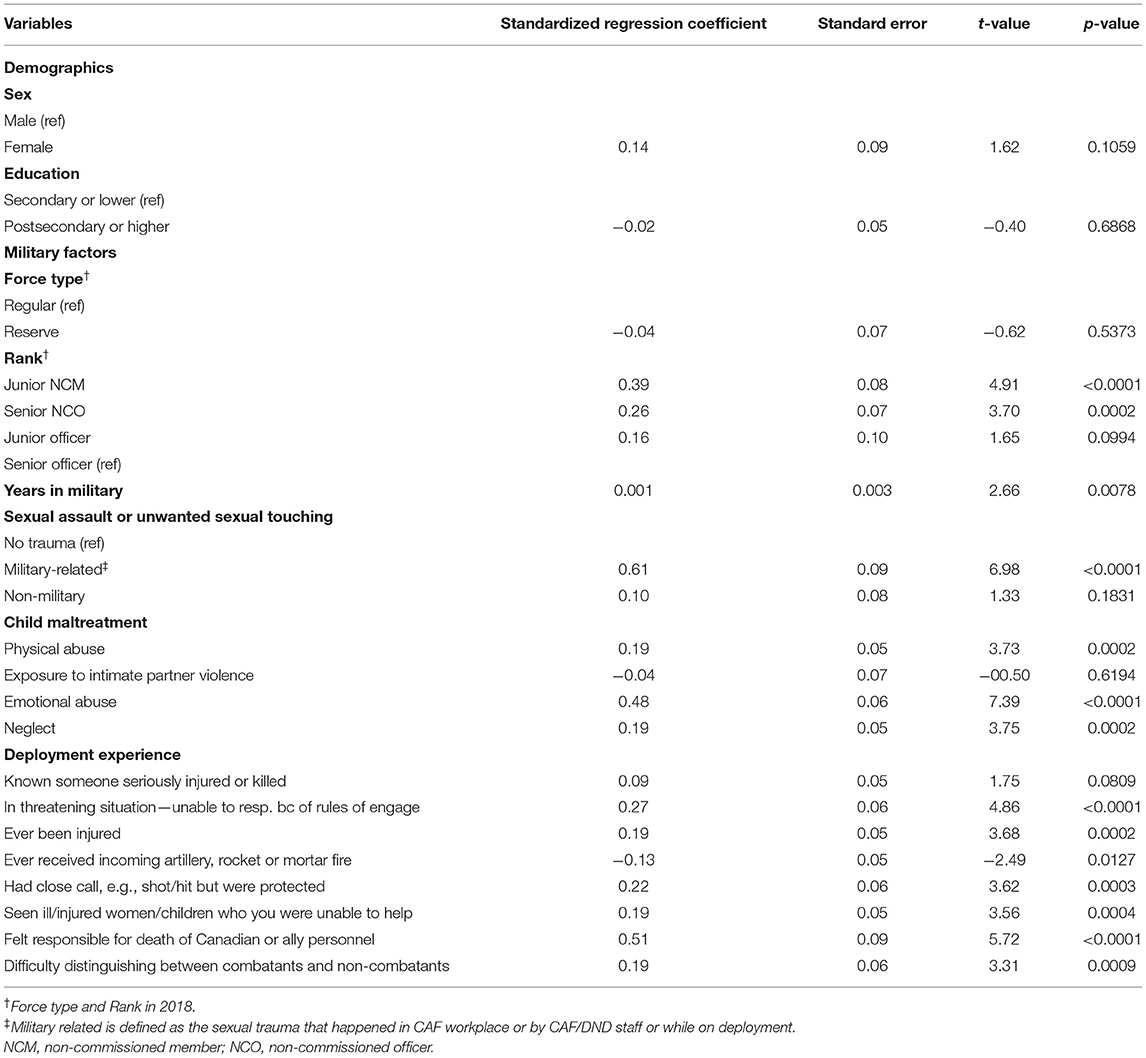

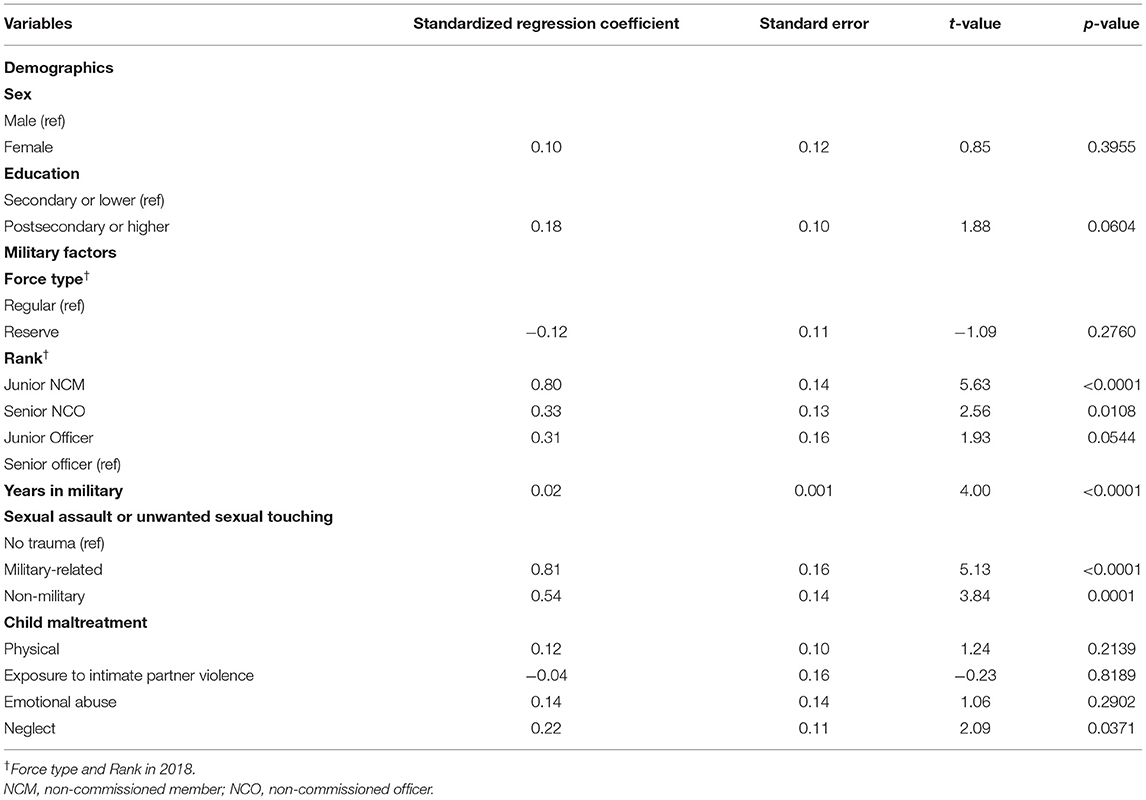

Multiple linear regression models to determine independent risk factors for increased MI score are reported in Tables 4, 5. The independent variables accounted for approximately 25% of the variance in MI scores in the deployed sample and 17% in non-deployed CAF personnel. Rank, years in military, military-related sexual trauma, childhood physical and emotional abuse, childhood neglect, and stressful deployment experiences were predictors of increased MI score in the deployed sample (Table 4). When all variables were included in the model, the strongest deployment-related predictors of higher MI score were feeling responsible for the death of an ally and inability to respond in a threatening situation due to rules of engagement. Within the non-deployed sample, rank, experiencing sexual trauma (military or civilian), years in the military, and childhood neglect were the only significant predictors of increased MI scores (Table 5).

Table 4. Multiple linear regression model of MIES scores regressed on military/sociodemographic factors among deployed CAF personnel (weighted n = 43,700).

Table 5. Multiple linear regression model of MIES scores regressed on military/sociodemographic factors among non-deployed CAF personnel (weighted n = 8,800).

Discussion

This is the first study to identify factors associated with increased MI using a representative survey of Canadian military personnel. Among non-deployed CAF personnel, experiencing either military-related or civilian sexual trauma, and junior non-commissioned member rank (compared to senior officer) were significantly associated with increased MI total scores. Among the previously deployed CAF personnel, child maltreatment (i.e., neglect, physical abuse and emotional abuse), experiencing military-related sexual trauma, and stressful deployment experiences (e.g., feeling responsible for the death of an ally) were significant predictors of MI total scores.

Specific military variables, including deployment experiences and individual rank, were independently associated with MIES score in deployed personnel. These experiences, such as seeing ill or injured children and being unable to help, may be categorized as PMIEs as they are situations that may lead to the violation of moral values (24), a precursor to MI. Further, in both deployed and non-deployed samples, rank was independently associated with MIES score, which is consistent with previous findings (11). Interestingly with regards to rank, being a junior non-commissioned member, regardless of deployment status, conferred the strongest association with MIES scores when compared to senior officers. This could be due to a multitude of factors, including differences in duties, increased likelihood of deployment related PMIEs, and power structure dynamics inherent in the military rank system.

Importantly, sexual trauma was a significant predictor of MIES score in the simple linear regression models for both deployed and non-deployed CAF members, perhaps due to feelings of perceived betrayal from these experiences (25). However, when all variables were considered together, military sexual trauma was the only sexual trauma variable significantly associated with MIES score in deployed CAF personnel. Military sexual trauma perpetrated by CAF personnel or DND staff or at a CAF workplace, defined in this study as unwanted touching or sexual assault, was a significant predictor of increased MIES score in both the deployed and non-deployed samples. These definitions largely overlap with the concept of Military Sexual Misconduct (MSM), which has been associated with adverse mental and physical health outcomes, including PTSD, in U.S. military populations (26, 27). In 2018, 70% of CAF respondents reported experiencing targeted MSM during the previous 12 months of military service (28), indicating that this is a pervasive and preventable risk factor for the development of MI. Although civilian sexual trauma was not a significant predictor of MI in deployed CAF personnel, it did significantly predict MI scores in the non-deployed sample and among both simple linear regression models. It is plausible that there was overlapping variance between, for example, civilian sexual trauma and other variables (e.g., childhood maltreatment) that rendered these associations non-significant in the full deployed model. Additional research regarding the relative risk of civilian and military-related sexual trauma and their overlap in both deployed and non-deployed samples is warranted. Such studies are likely to shed additional light on the mechanisms and contextual factors associated with the development of MI.

Our analyses further indicated that childhood physical and emotional abuse and childhood neglect were positive predictors of increased MI scores in deployed CAF personnel, though only childhood neglect was a positive predictor in non-deployed personnel. The deployed sample results were consistent with previous findings in treatment-seeking CAF Veteran convenience samples (29). Consistent with our findings, a history of childhood abuse and its implications for negative mental and physical health outcomes in adults has been well-documented (30–35). In the same way that research has shown that childhood/earlier traumatic experiences increase risk for exposure to future trauma and PTSD (23), these findings indicate that the same may be true for PMIEs and MI, with increased exposure to PMIEs in childhood possibly increasing the risk for exposure to other PMIEs or development of MI later in life. Although childhood trauma variables except neglect were not significant predictors of increased MI in non-deployed personnel, there were significant associations between childhood maltreatment variables and MIES scores in the simple regression models. It is plausible, then, that child maltreatment shared common variance with non-military-related sexual trauma that attenuated the associations between childhood maltreatment variables and MIES scores.

Limitations

Although the findings of this study provide novel information regarding predictors of MI in deployed and non-deployed CAF personnel, we acknowledge several limitations. Due to the longitudinal nature of the CAFVMHS, the 2018 sample is representative of the original 2002 CAF sample that took part in the initial survey and is not necessarily representative of current CAF demographics. In addition, because the sample was primarily composed of men, this limited our ability to assess how sex and gender may be associated with moral distress in the CAF. Furthermore, variables included in the analyses are not an exhaustive list of potential predictors of MI, especially given that the study of MI remains in its infancy. Importantly, psychological traumas external to military experiences aside from sexual assault were not included in analysis, as the MIES alludes exclusively to military experiences. There is also the possibility that other peri-deployment or post-deployment experiences captured in this survey that were not included in the analyses may have influenced the endorsement of MI. Due to response bias, there may also be unknown differences between survey responders and non-responders, which may theoretically have altered findings of this study. However, previous research on attrition in this sample found that military status, mental health disorders, traumatic experiences and childhood adversity were not associated with loss to follow-up (18).

Childhood maltreatment was also assessed retrospectively during adulthood in this survey, which may introduce recall bias. However, research indicates that this is unlikely, as retrospective recall of childhood trauma seems to be reliable (18, 36, 37). Although relevant literature points to a strong correlation between childhood sexual abuse and negative mental health outcomes (38–43), childhood sexual trauma was not included in the regression models due to being captured by the item endorsing lifetime sexual trauma. This precluded us from determining how or whether childhood sexual trauma may influence MI endorsement in this population.

Although it is currently the most widely used measure of MI, the MIES has been previously criticized for conflating MI exposure and subjective experience without differentiating between the constructs during scoring, which may inadvertently introduce extraneous variance when attempting to determine severity of MI (20). The subjective self-report nature of the measure, as well as the logic skipping that was used during Statistics Canada administration may also have introduced response biases in the survey. The CAFVMHS 2018 MIES scoring logic, wherein a participant selecting strongly disagree for certain items automatically imputed strongly disagree for a subsequent item, could have created issues with total MIES scoring. However, following previous research (20) regarding MIES response patterns in this population, we believe that it is unlikely that this logic skipping introduced bias within the survey.

Future directions should include assessing MI using a scale that focuses on the expressed outcomes that make up the MI construct (e.g., spiritual struggles, guilt) and investigate the nuances present in how exposures and outcomes are related. Since the time that data were collected for this study, a number of measures that clearly differentiate outcomes of PMIEs from exposures to PMIEs have been developed, although additional psychometric validation for these measures is warranted. Future research should also consider separate risk factors for endorsement of MI that were not captured in this survey, such as personality traits. Finally, while consensus is amounting that MI is a clinically useful construct [e.g., (44, 45)], additional research is needed to establish effective screening and intervention strategies within military and other populations at heightened risk of MI. Implications of these results indicate that specific care should be taken to incorporate discussion surrounding MI, and tailored treatments to reduce symptoms of MI (e.g., anger, shame) within treatment-seeking military contexts. Focus of future interventions should also be placed on pre-deployment training and preparation for military personnel to effectively understand and cope with morally injurious experiences.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this is the first study to evaluate predictors of MI endorsement in a representative sample of CAF personnel. Our findings emphasize the critical importance of explicitly screening for and addressing deployment experiences and military sexual trauma in the context of evaluating and addressing MI in military populations. Results also point to several demographic and developmental factors that should be further investigated in future research aiming to understand individual vulnerability to MI.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data can be accessed in Canada with permission of Statistics Canada through the Statistics Canada Research Data Centers. Statistics Canada collected and provided the data for academic purposes, but the analyses are the sole responsibility of the authors. The opinions expressed do not represent the views of Statistics Canada. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Statistics Canada's Statistical Information Service, U1RBVENBTi5pbmZvc3RhdHMtaW5mb3N0YXRzLlNUQVRDQU5AY2FuYWRhLmNh. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Statistics Canada. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

BE, AN, SH, RP, AL, MM, and JR contributed to the conception, design of this project, and made changes in online comments. BE, AN, SH, RP, and AL created the conceptual models. AL conducted the analyses. BE wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SH, RP, AA, NM, TA, and ME made important contributions to sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Boulos D, Zamorski MA. Deployment-related mental disorders among Canadian Forces personnel deployed in support of the mission in Afghanistan, 2001-2008. CMAJ. (2013) 185:E545–52. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.122120

2. Van Til L, Sweet J, Poirier A, McKinnon K, Pedlar D. Well-Being of Canadian Regular Forces Veterans, Findings From LASS 2016 Survey. Charlottetown, PE: Veterans Affairs Canada. Research Directorate Technical Report (2017).

3. Norman SB, Haller M, Hamblen JL, Southwick SM, Pietrzak RH. The burden of co-occurring alcohol use disorder and PTSD in U. S Military veterans: comorbidities, functioning, and suicidality. Psychol Addict Behav. (2018) 32:224–9. doi: 10.1037/adb0000348

4. Arenson MB, Whooley MA, Neylan TC, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and suicidal ideation in veterans: results from the mind your heart study. Psychiatr Res. (2018) 265:224–30. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.04.046

5. Ramchand R, Rudavsky R, Grant S, Tanielian T, Jaycox L. Prevalence of, risk factors for, and consequences of posttraumatic stress disorder and other mental health problems in military populations deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Curr Psychiatr Rep. (2015) 17:37. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0575-z

6. Fikretoglu D, Liu A, Zamorski MA, Jetly R. Perceived need for and perceived sufficiency of mental health care in the Canadian Armed Forces: changes in the past decade and comparisons to the general population. Can J Psychiatr. (2016) 61(Suppl. 1):36S−45S. doi: 10.1177/0706743716628855

7. Rusu C, Zamorski MA, Boulos D, Garber BG. Prevalence comparison of past-year mental disorders and suicidal behaviours in the Canadian Armed Forces and the Canadian general population. Can J Psychiatr. (2016) 61(Suppl. 1): 46S−55S. doi: 10.1177/0706743716628856

8. Statistics Canada. Canadian Armed Forces Members and Veterans Mental Health Follow-Up Survey 2018. Available online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/190423/dq190423d-eng.htm (accessed April 3, 2021).

9. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, Stein MB, Belik SL, Meadows G, et al. Combat and peacekeeping operations in relation to prevalence of mental disorders and perceived need for mental health care. Arch Gen Psychiatr. (2007) 64:843–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.843

10. Nazarov A, Jetly R, McNeely H, Kiang M, Lanius R, McKinnon MC, et al. Role of morality in the experience of guilt and shame within the armed forces. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2015) 132:4–19. doi: 10.1111/acps.12406

11. Nazarov A, Fikretoglu D, Liu A, Thompson M, Zamorski MS. Greater prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression in deployed Canadian Armed Forces personnel at risk for moral injury Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2018) 137:1–13. doi: 10.1111/acps.12866

12. Thompson MM. Moral Injury in Military Operations: A Review of the Literature and Key Considerations for the Canadian Armed Forces. Ottawa, Scientific Report. Defence Research and Development Canada Publications, DRDC-RDDC-2015-R029, (2015).

13. Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, Lebowitz L, Nash WP, Silva C, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. (2009) 29:695–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

15. Wisco BE, Marx BP, May CL, Martini B, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, et al. Moral injury in US combat veterans: results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. Depress Anxiety. (2017) 34:340–7. doi: 10.1002/da.22614

16. Smith-MacDonald LA, Morin JS, Brémault-Phillips S. Spiritual dimensions of moral injury: Contributions of mental health chaplains in the Canadian Armed Forces. Front Psychiatr. (2018) 9:592. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00592

17. Afifi TO, Bolton SL, Mota N, Marrie RA, Steib MB, Enns MW, et al. Rationale and Methodology of the 2018 Canadian Armed Forces Members and Veterans Mental Health Follow-up Survey (CAFVMHS): a 16-year follow-up survey. Can J Psychiatr. (2020) 66:942–50. doi: 10.1177/0706743720974837

18. Bolton SL, Afifi TO, Mota NP, Enns MW, de Graaf R, Marrie RA, et al. Patterns of attrition in the Canadian Armed Forces Members and Veterans Mental Health Follow-up Survey (CAFVMHS). Can J Psychiatry. (2021) 66:996–8. doi: 10.1177/07067437211002697

19. Nash WP, Marino Carper TL, Mills MA et al. Psychometric evaluation of the moral injury events scale. Mil Med. (2013) 1778:646–52. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00017

20. Plouffe RA, Easterbrook B, Liu A, McKinnon MC, Richardson JD, Nazarov A. Psychometric evaluation of the moral injury events scale in two Canadian armed forces samples. Assessment. (2021) 10731911211044198. doi: 10.1177/10731911211044198. [Epub ahead of print].

21. Guyker WM, Donnelly K, Donnelly JP et al. Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the combat experiences scale. Mil Med. (2013) 178:377–84. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-12-00223

22. Walsh CA, MacMillan HL, Trocme N, Jamieson E, Boyle MH. Measurement of victimization in adolescence: development and validation of the Childhood Experiences of Violence Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. (2008) 32:1037–57. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.05.003

23. Afifi TO, MacMillan HL, Boyle M, Taillieu T, Cheung K, Sareen J. Child abuse and mental disorders in Canada. Can Med Assoc J. (2014) 186:E324–32. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131792

24. Currier JM, Drescher KD, Nieuwsma J. Introduction to moral injury. In: Currier JM, Drescher KD, Nieuwsma J, editors. Addressing Moral Injury in Clinical Practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association (2021). p. 3–18

25. Bryan CJ, Bryan AO, Anestis MD, Anestis JC, Green BA, Etienne N, et al. Measuring moral injury: psychometric properties of the moral injury events scale in two military samples. Assessment. (2015) 23:557–70. doi: 10.1177/1073191115590855

26. Skinner KM, Kressin N, Frayne S, Tripp TJ, Hankin CS, Miller DR, et al. The prevalence of military sexual assault among female Veterans' Administration outpatients. J Interpersonal Violence. (2000) 15:291–310. doi: 10.1177/088626000015003005

27. El-Gabalawy R, Blaney C, Tsai J, Sumner JA, Pietrzak RH. Physical health conditions associated with full and subthreshold PTSD in US military veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Affective Disorders. (2018) 227:849–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.058

28. Cotter A. Sexual misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces Regular Force, 2018. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada (2019).

29. Battaglia AM, Protopopescu A, Boyd JE, Lloyd C, Jetly R, O'Connor C, et al. The relation between adverse childhood experiences and moral injury in the Canadian Armed Forces. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2019) 10:1546084. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2018.1546084

30. Bifulco A, Bernazzi O, Moran PM. Ball C. Lifetime stressors and recurrent depression: preliminary findings of the Adult Life Phase Interview (ALPHI). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2000) 35:264–75. doi: 10.1007/s001270050238

31. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. (1998) 14:245–58. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

32. Ferguson KS, Dacey CM. Anxiety, depression, and dissociation in women health care providers reporting a history of childhood psychological abuse. Child Abuse Negl. (1997) 21:941–52. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00055-0

33. Kessler RC, Magee WJ. Childhood family violence and adult recurrent depression. J Health Soc Behav. (1994) 35:13–27. doi: 10.2307/2137332

34. Widom CS. Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up. Am J Psychiatry. (1999) 156:1223–9.

35. Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, Hettema JM, Myers J, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: an epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2000) 57:953–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.953

36. Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2004) 45:260–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x

37. Hardt J, Sidor A, Bracko M, Egle UT. Reliability of retrospective assessments of childhood experiences in Germany. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2006) 194:676–83. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000235789.79491.1b

38. Hardt J, Vellaisamy P, Schoon I. Sequelae of prospective versus retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences. Psychol Rep. (2010) 107:425–40. doi: 10.2466/02.04.09.10.16.21.PR0.107.5.425-440

39. Amado BG, Arce R, Herraiz A. Psychological injury in victims of child sexual abuse: a meta-analytic review. Psychosoc Interv. (2015) 24:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.psi.2015.03.002

40. Chen LP, Murad MH, Paras ML, Colbenson KM, Sattler AL, Goranson EN, et al. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. (2010) 85:618–29. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0583

41. Maniglio R. Child sexual abuse in the etiology of anxiety disorders: a systematic review of reviews. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2013) 14:96–112. doi: 10.1177/1524838012470032

42. Hillberg T, Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Dixon L. Review of meta-analyses on the association between child sexual abuse and adult mental health difficulties: a systematic approach. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2011) 12:38–49. doi: 10.1177/1524838010386812

43. Lindert J, von Ehrenstein OS, Grashow R, Gal G, Braehler E, Weisskopf MG. Sexual and physical abuse in childhood is associated with depression and anxiety over the life course: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Public Health. (2014) 59:359–72. doi: 10.1007/s00038-013-0519-5

44. Drescher K. D., Foy D. W., Kelly C., Leshner A., Schutz K., Litz B. (2011). An Exploration of the Viability and Usefulness of the Construct of Moral Injury in War Veterans. Traumatology, 17:8–13. doi: 10.1177/1534765610395615

45. Yeterian J. D., Berke D. S., Carney J. R., McIntyre-Smith A., St Cyr K., King L., Kline N. K., Phelps A., Litz B. T., Members of the Moral Injury Outcomes Project Consortium (2019). Defining and Measuring Moral Injury: Rationale, Design, and Preliminary Findings From the Moral Injury Outcome Scale Consortium. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32:363–372. doi: 10.1002/jts.22380

Keywords: mental health, deployment, military personnel, stress disorder, post-traumatic, moral injury, child maltreatment

Citation: Easterbrook B, Plouffe RA, Houle SA, Liu A, McKinnon MC, Ashbaugh AR, Mota N, Afifi TO, Enns MW, Richardson JD and Nazarov A (2022) Risk Factors for Moral Injury Among Canadian Armed Forces Personnel. Front. Psychiatry 13:892320. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.892320

Received: 08 March 2022; Accepted: 21 April 2022;

Published: 11 May 2022.

Edited by:

R. Michael Bagby, University of Toronto, CanadaReviewed by:

Mary Jo Larson, Brandeis University, United StatesJan Ilhan Kizilhan, University of Duhok, Iraq

Copyright © 2022 Easterbrook, Plouffe, Houle, Liu, McKinnon, Ashbaugh, Mota, Afifi, Enns, Richardson and Nazarov. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anthony Nazarov, YW50aG9ueS5uYXphcm92QHNqaGMubG9uZG9uLm9uLmNh

†These authors share senior authorship

Bethany Easterbrook

Bethany Easterbrook Rachel A. Plouffe

Rachel A. Plouffe Stephanie A. Houle5

Stephanie A. Houle5 Margaret C. McKinnon

Margaret C. McKinnon Natalie Mota

Natalie Mota J. Don Richardson

J. Don Richardson Anthony Nazarov

Anthony Nazarov