- 1School of Creative Media, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

- 2beClaws.org, London, United Kingdom

- 3Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 4Centre for Gambling Research, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada

- 5Biopsychology Lab, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

By Tang ACY, Lee PH, Lam SC, Siu SCN, Ye CJ and Lee RLT (2022) Front. Psychiatry 13:940281. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.940281

1 Introduction

Modifying core items created a novel construct wrongly identified as measuring problem gambling. Tang et al. (1) purported to report that ‘problem gambling’, as they defined it, is associated with monetary spending on video game mechanics that involve randomisation (e.g., gacha mechanics (2, 3) and loot boxes (4)) amongst young Hong Kong players of games containing such mechanics. At face value, that assertion is not surprising, as a consistent line of research has previously established that relationship in Western countries (5–7), which has been relied upon in policymaking (8, 9). Research conducted subsequent to Tang et al. in Mainland China has also replicated the relationship (10).

However, unfortunately, the study of Tang et al. suffered from a fundamental flaw. That study did not, in fact, measure ‘problem gambling’ as traditionally defined because Tang et al. significantly modified the measurement scale. Instead, Tang et al. measured only ‘problematic participation in gacha mechanics’ and proved that various relationships existed between that construct and other variables, which arguably is less meaningful (11, 12). The development of that new scale lacked transparency and evidence of reliability and validity. It is unclear whether that new measure is related to ‘problem gambling’ and, if so, to what extent. In any case, it is not, and cannot be used as, a direct replacement without further validation.

Tang et al. could not, in fact, have been able to report on any issues concerning ‘problem gambling’ because by definition, they did not measure ‘problem gambling’. They should not have claimed to have been able to test or comment on any psychological relationships concerning ‘problem gambling’. The current framing of that paper and its conclusions is misleading to readers whose attention is not specifically drawn to this highly significant measurement modification. This commentary intends to correct that misimpression. Simply put, Tang et al. did not prove what their title suggested. That paper must be treated with due caution and considered for exclusion from meta-analyses.

2 Discussion

Specifically, when purporting to measure ‘problem gambling’, Tang et al. used a significantly modified version of the Chinese version of the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI). The PGSI was originally created in English (13) but has since been translated and validated in Chinese (14). Therefore, the use of the Chinese language version of the PGSI instead of the English version is not at issue. In fact, the Chinese PGSI has been used with success in other loot box studies in China (10, 15).

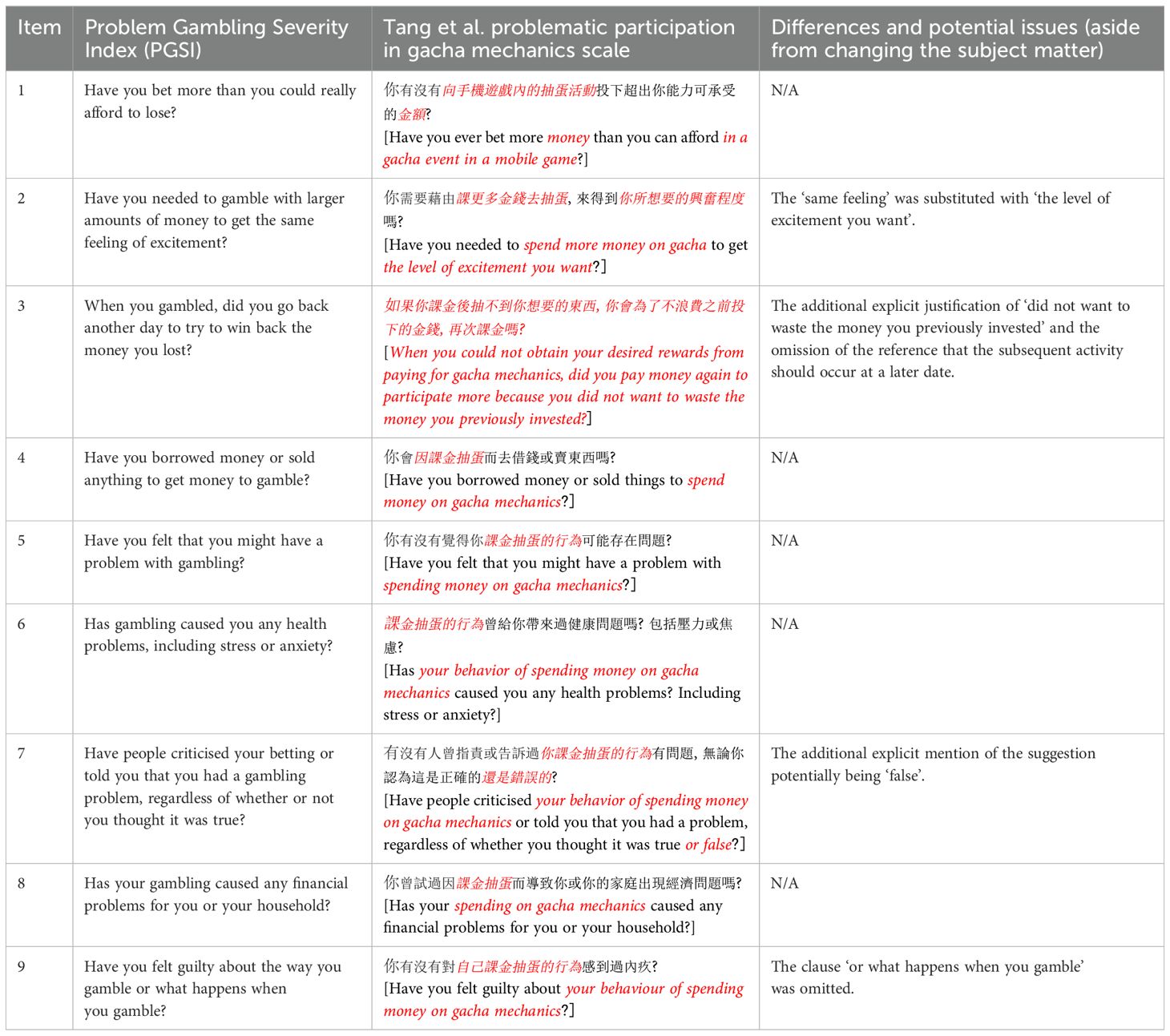

The problem was that Tang et al. modified the wording of the PGSI beyond a mere translation: references to ‘gambling [賭博]’ were all converted to ‘spending money on gacha mechanics [課金抽蛋]’, as the authors revealed in a personal response to LX’s query and as shown in Table 1. This modification was disclosed at page 4 of the original paper only very vaguely and not sufficiently prominently (‘As PGSI-C was originally developed for screening general gambling activities, the authors had modified a few words on some items to fit the context of gacha games’) (1). All modifications made should have been fully disclosed in detail.

Table 1. The Problem Gambling Severity Index compared to the Tang et al.’s problematic participation in gacha mechanics scale (with changes marked with red italics).

In theory, making such modifications to create a new scale is not problematic in and of itself, although when not done properly and transparently, it might constitute so-called ‘measurement schmeasurement’ or ‘questionable measurement practices’ that ‘raise doubts about the validity of the measures, and ultimately the validity of study conclusions’ (16, p.456). Other constructs, whose developments were much better detailed, have sought to measure potentially problematic engagement with loot boxes, e.g., the ‘Risky Loot Box Index’ (RLI) (10, 17–19) and the ‘Problematic Use of Loot Boxes Questionnaire’ (PU-LB) (20, 21). However, Tang et al.’s continued representation of the modified scale as if it measured ‘problem gambling’ as traditionally understood was misleading because following the modification, the scale instead measured ‘problematic participation in gacha mechanics’—a completely different construct. The modification effectively created a new and, importantly, unvalidated problematic gacha engagement scale more comparable to the RLI (10, 17, 18). This means that Tang et al. misrepresented their construct of ‘problematic participation in gacha mechanics’ as a measure of ‘problem gambling’ throughout the paper, from title to abstract, through the results, and into the conclusion.

Other substantive changes were also made to the PGSI. For example, the third item of the PGSI was not just slightly amended by having a few words modified but completely replaced, causing its meaning to change. The original question was: ‘When you gambled, did you go back another day to try to win back the money you lost?’ (13). The third question in the modified scale used by Tang et al. was: ‘When you could not obtain your desired rewards from paying for gacha mechanics, did you pay money again to participate more because you did not want to waste the money you previously invested?’ It is obvious that Tang et al. tried to replicate a similar sentiment of ‘loss chasing’ in both contexts (22), but there is a conceptual difference between a) more actively wanting to win back past losses and b) more passively not wanting to waste previous investments referenced by Tang et al.’s new item, which is more akin to entrapment and the sunk cost fallacy (23). The explicit reference to wasting previous investments could have been omitted in the modified scale, which could have just asked whether the participant tried to win the desired reward again by spending more money at a later date. Again, the question that was asked may have been perfectly acceptable for measuring the underlying behaviour. However, there was a lack of transparent disclosure of the modification and the justifications thereof, which casts doubt on the reliability of the measurement construction, its validity, and resultant findings (16).

3 Conclusion

Research conducted in Mainland China after Tang et al. has confirmed that spending on loot boxes is associated with problem gambling as traditionally understood (10), thus alleviating concerns that the relationship may not be replicable beyond Western samples (15, 24). Nonetheless, it must be clarified that Tang et al. did not measure ‘problem gambling’ but ‘problematic participation in gacha mechanics’ instead, which is a possibly related but substantially different construct. Readers must be informed that they ought to approach Tang et al. by mentally amending all references to ‘problem gambling’ in the paper (including title and abstract) to the new, unvalidated construct of ‘problematic participation in gacha mechanics’ instead, which is incredibly burdensome. Tang et al. must be corrected to ensure the accuracy and integrity of the scientific record. Attempts should also be made to validate the modified scale used by Tang et al. to better understand how that new construct is related to the traditional ‘problem gambling’ construct and whether the modified scale may have future utility as an alternative to the RLI (10, 17–19) and the PU-LB (20, 21).

Author’s note

LX plays and enjoys video games and broadly views the activity very positively, except for certain aspects (e.g., monetisation) that he believes should be subject to more scrutiny. In terms of LX’s personal engagement with loot boxes, he has played and continues to play video games containing loot boxes, such as Hearthstone (Blizzard Entertainment, 2014) until 2018 and Genshin Impact (miHoYo, 2020) and Zenless Zone Zero (miHoYo, 2024) since their initial release. He, therefore, engaged and continues to engage with non-paid loot boxes on a regular basis. However, he has never purchased any loot boxes with real-world money aside from negligible spending for research purposes, e.g., to confirm the presence of paid loot boxes.

Author contributions

LX: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NB: Writing – review & editing. CE: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. LX is supported by a Presidential Assistant Professors Scheme Start-Up Research Grant awarded by the City University of Hong Kong [香港城市大學] (March 2025). CE is funded by a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Action fellowship, the ‘GamblingEmotion’ Project No. 101150127, under the European Union’s Horizon Europe Programme (https://marie-sklodowska-curie-actions.ec.europa.eu).

Conflict of interest

LX has provided paid consultancy for (i) Public Group International Ltd (t/a PUBLIC) (Companies House number: 10608507), commissioned by the UK Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) to conduct independent research on understanding player experiences of loot box protections (October 2024–May 2025) and (ii) the Council of Europe International Cooperation Group on Drugs and Addiction (the Pompidou Group) on a project concerning the risks of online gambling and gaming to young people co-funded by the European Union via the Technical Support Instrument and implemented by the Council of Europe, in cooperation with the European Commission (December 2024–May 2025). LX was supported by a PhD Fellowship funded by the IT University of Copenhagen [IT-Universitetet i København] (December 2021–November 2024). LX was employed by LiveMe, then a subsidiary of Cheetah Mobile (NYSE: CMCM), as an in-house counsel intern from July to August 2019 in Beijing, China. LX was not involved with the monetisation of video games by Cheetah Mobile or its subsidiaries. LX undertook a brief period of voluntary work experience at Wiggin LLP (Solicitors Regulation Authority number: 420659) in London, England, in August 2022. LX has contributed to research projects enabled by data access provided by the video game industry, specifically Unity Technologies (NYSE:U) (October 2022–August 2023). LX has been invited to provide advice to the UK Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and its successor (the Department for Culture, Media and Sport; DCMS) on the technical working group for loot boxes and the Video Games Research Framework. LX was the (co-)recipient of three Academic Forum for the Study of Gambling (AFSG) postgraduate research support grants (March 2022, January 2023, and July 2024) and a minor exploratory research grant (May 2024) derived from ‘regulatory settlements applied for socially responsible purposes’ received by the UK Gambling Commission and administered by Gambling Research Exchange Ontario (GREO) and its successor (Greo Evidence Insights; Greo). LX accepted funding to publish open-access academic papers from GREO and the AFSG that was received by the UK Gambling Commission as above (October, November, and December 2022, November 2023, and May 2024). LX was the recipient of an Elite Research Travel Grant 2024 [EliteForsk-rejsestipendium 2024] awarded by the Agency for Higher Education and Science of the Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science [Uddannelses-og Forskningsstyrelsen under Uddannelses-og Forskningsministeriet] (February 2024). LX has accepted conference travel and attendance grants from the Socio-Legal Studies Association (February 2022 and February 2023); the Current Advances in Gambling Research Conference Organising Committee with support from GREO (February 2022); the International Relations Office of The Jagiellonian University (Uniwersytet Jagielloński), the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange (NAWA; Narodowa Agencja Wymiany Akademickiej), and the Republic of Poland (Rzeczpospolita Polska) with co-financing from the European Social Fund of the European Commission of the European Union under the Knowledge Education Development Operational Programme (May 2022); the Society for the Study of Addiction (November 2022, March 2023, and November 2024); the organisers of the 13th Nordic SNSUS (Stiftelsen Nordiska Sällskapet för Upplysning om Spelberoende; the Nordic Society Foundation for Information about Problem Gambling) Conference, which received gambling industry sponsorship (January 2023); the MiSK Foundation (Prince Mohammed bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Foundation) (November 2023); and the UK Gambling Commission (March 2024). LX has received honoraria from the Center for Ludomani for contributing parent guides about mobile games for Tjekspillet.dk, which was funded by the Danish Ministry of Health’s gambling addiction pool (Sundhedsministeriets Ludomanipulje) (March and December 2023), the Fundació Pública Tecnocampus Mataró-Maresme (TecnoCampus Mataró-Maresme Foundation) for a guest lecture (November 2023), the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) of Greater Toronto Youth Gambling Awareness Program for a presentation, which was funded by the Government of Ontario, Canada (March 2024), Lunds universitet (Lund University) for the right to translate parent guides about mobile games into Swedish for Kollaspelet.se, which was funded by Mediamyndigheten (the Swedish Agency for the Media) and Barnahus Stockholm (December 2024); Shenkar College of Engineering, Design and Art for a guest lecture (December 2024); and DiGRA Korea and the Game-n-Science Institute [게임과학연구원] under the Game Culture Foundation [게임문화재단] under the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism of South Korea [문화체육관광부] for participating in an academic research survey (January 2025). LX received royalties by virtue of the copyright subsisting in some of his publications from the Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society (ALCS) (Companies House number: 01310636) (March 2023, 2024, and 2025). A full gifts and hospitality register-equivalent for LX is available at: https://www.leonxiao.com/about/gifts-and-hospitality-register. The up-to-date version of LX’s conflict-of-interest statement is available at: https://www.leonxiao.com/about/conflict-of-interest.

CE is affiliated with the Centre for Gambling Research at University of British Columbia (UBC), which is supported by the Province of British Columbia government and the British Columbia Lottery Corporation (BCLC; a Canadian Crown Corporation).

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Tang ACY, Lee PH, Lam SC, Siu SCN, Ye CJ, and Lee RLT. Prediction of problem gambling by demographics, gaming behavior and psychological correlates among gacha gamers: A cross-sectional online survey in Chinese young adults. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13. Article 940281. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.940281

2. Woods O. The economy of time, the rationalisation of resources: discipline, desire and deferred value in the playing of gacha games. Games Cult. (2022) 17:1075–92. doi: 10.1177/15554120221077728

3. Blom J. The genshin impact media mix: free-to-play monetization from east asia. MeChademia. (2023) 16:144–66.

4. Drummond A and Sauer JD. Video game loot boxes are psychologically akin to gambling. Nat Hum Behav. (2018) 2:530–2. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0360-1

5. Zendle D and Cairns P. Video game loot boxes are linked to problem gambling: Results of a large-scale survey. PloS One. (2018) 13:e0206767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206767

6. Garea SS, Drummond A, Sauer JD, Hall LC, and Williams MN. Meta-analysis of the relationship between problem gambling, excessive gaming and loot box spending. Int Gambling Stud. (2021) 21:460–79. doi: 10.1080/14459795.2021.1914705

7. Spicer SG, Nicklin LL, Uther M, Lloyd J, Lloyd H, and Close J. Loot boxes, problem gambling and problem video gaming: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. New Media Soc. (2022) 24:1001–22. doi: 10.1177/14614448211027175

8. Xiao LY, Henderson LL, Nielsen RKL, and Newall PWS. Regulating gambling-like video game loot boxes: a public health framework comparing industry self-regulation, existing national legal approaches, and other potential approaches. Curr Addict Rep. (2022) 9:163–78. doi: 10.1007/s40429-022-00424-9

9. Leahy D. Rocking the boat: loot boxes in online digital games, the regulatory challenge, and the EU’s unfair commercial practices directive. J Consum Pol. (2022) 45:561–92. doi: 10.1007/s10603-022-09522-7

10. Xiao LY, Fraser TC, Nielsen RKL, and Newall PWS. Loot boxes, gambling-related risk factors, and mental health in Mainland China: A large-scale survey. Addictive Behav. (2024) 148. Article 107860. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107860

11. Sidloski B, Brooks G, Zhang K, and Clark L. Exploring the association between loot boxes and problem gambling: are video gamers referring to loot boxes when they complete gambling screening tools? Addictive Behav. (2022) 131:107318. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107318

12. Xiao LY, Newall P, and James RJE. To screen, or not to screen: An experimental comparison of two methods for correlating video game loot box expenditure and problem gambling severity. Comput Hum Behav. (2024) 151. Article 108019. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2023.108019

13. Ferris J and Wynne H. The Canadian Problem Gambling Index: Final Report. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse (2001). Available online at: https://www.greo.ca/Modules/EvidenceCentre/files/Ferris%20et%20al(2001)The_Canadian_Problem_Gambling_Index.pdf (Accessed July 31, 2025).

14. Loo JMY, Oei TPS, and Raylu N. Psychometric evaluation of the problem gambling severity index-chinese version (PGSI-C). J Gambl Stud. (2011) 27:453–66. doi: 10.1007/s10899-010-9221-1

15. Xiao LY, Fraser TC, and Newall PWS. Opening pandora’s loot box: weak links between gambling and loot box expenditure in China, and player opinions on probability disclosures and pity-timers. J Gambling Stud. (2023) 39:645–68. doi: 10.1007/s10899-022-10148-0

16. Flake JK and Fried EI. Measurement schmeasurement: questionable measurement practices and how to avoid them. Adv Methods Pract psychol Sci. (2020) 3:456–65. doi: 10.1177/2515245920952393

17. Brooks GA and Clark L. Associations between loot box use, problematic gaming and gambling, and gambling-related cognitions. Addict Behav. (2019) :96:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.04.009

18. Forsström D, Chahin G, Savander S, Mentzoni RA, and Gainsbury S. Measuring loot box consumption and negative consequences: Psychometric investigation of a Swedish version of the Risky Loot Box Index. Addictive Behav Rep. (2022) 16:100453. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2022.100453

19. Guo P, Liu Y, Tan L, Xu Y, Huang H, and Deng Q. Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of Risky Loot Box Index (RLI) and cross-sectional investigation among gamers of China. PeerJ. (2025) 13:e19164. doi: 10.7717/peerj.19164

20. González-Cabrera J, Basterra-González A, Montiel I, Calvete E, Pontes HM, and Machimbarrena JM. Loot boxes in Spanish adolescents and young adults: Relationship with internet gaming disorder and online gambling disorder. Comput Hum Behav. (2022) 126. Article 107012. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.107012

21. González-Cabrera J, Caba-MaChado V, Díaz-López A, Jiménez-Murcia S, Mestre-Bach G, and Machimbarrena JM. The mediating role of problematic use of loot boxes between internet gaming disorder and online gambling disorder: cross-sectional analytical study. JMIR Serious Games. (2024) 12:e57304. doi: 10.2196/57304

22. Zhang K and Clark L. Loss-chasing in gambling behaviour: neurocognitive and behavioural economic perspectives. Curr Opin Behav Sci. (2020) 31:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.10.006

23. Karlsen F. Entrapment and near miss: A comparative analysis of psycho-structural elements in gambling games and massively multiplayer online role-playing games. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2011) 9:193–207. doi: 10.1007/s11469-010-9275-4

Keywords: loot boxes, gacha, problem gambling, measurement schmeasurement, survey question design, scale construction and development

Citation: Xiao LY, Ballou N and Eben C (2025) Commentary: Prediction of problem gambling by demographics, gaming behavior and psychological correlates among gacha gamers: A cross-sectional online survey in Chinese young adults. Front. Psychiatry 16:1576323. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1576323

Received: 13 February 2025; Accepted: 24 July 2025;

Published: 25 August 2025.

Edited by:

Wulf Rössler, Charité University Medicine Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Stuart Spicer, University of Plymouth, United KingdomCopyright © 2025 Xiao, Ballou and Eben. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Leon Y. Xiao, bGVvbi54aWFvQGNpdHl1LmVkdS5oaw==

†ORCID: Leon Y. Xiao, orcid.org/0000-0003-0709-0777

Nick Ballou, orcid.org/0000-0003-4126-0696

Charlotte Eben, orcid.org/0000-0001-9423-1261

Leon Y. Xiao

Leon Y. Xiao Nick Ballou3†

Nick Ballou3†