- 1School of Medicine, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada

- 2Autism Research Centre, Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 3Department of Paediatrics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Background: Practitioners report a lack of knowledge and confidence in treating autistic children, resulting in unmet healthcare needs. The Extension of Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) Autism model addresses this through discussion of participant-generated cases, helping physicians provide best-practice care through co-created recommendations. Recommendations stemming from ECHO cases have yet to be characterized and may help guide the future care of autistic children. Our objective was to characterize and categorize case discussion recommendations from Project ECHO Ontario Autism to better identify gaps in clinician knowledge.

Methods: We conducted a summative content analysis of all ECHO Ontario Autism case recommendations to identify categories of recommendations and their frequencies. Two researchers independently coded recommendations from five ECHO cases to develop the coding guide. They then each independently coded all remaining cases and recommendations from three cycles of ECHO held between October 2018 to July 2021, meeting regularly with the ECHO lead to consolidate the codes. A recommendation could be identified with more than one code if it pertained to multiple aspects of autism care. Categories from the various codes were identified and the frequency of each code was calculated.

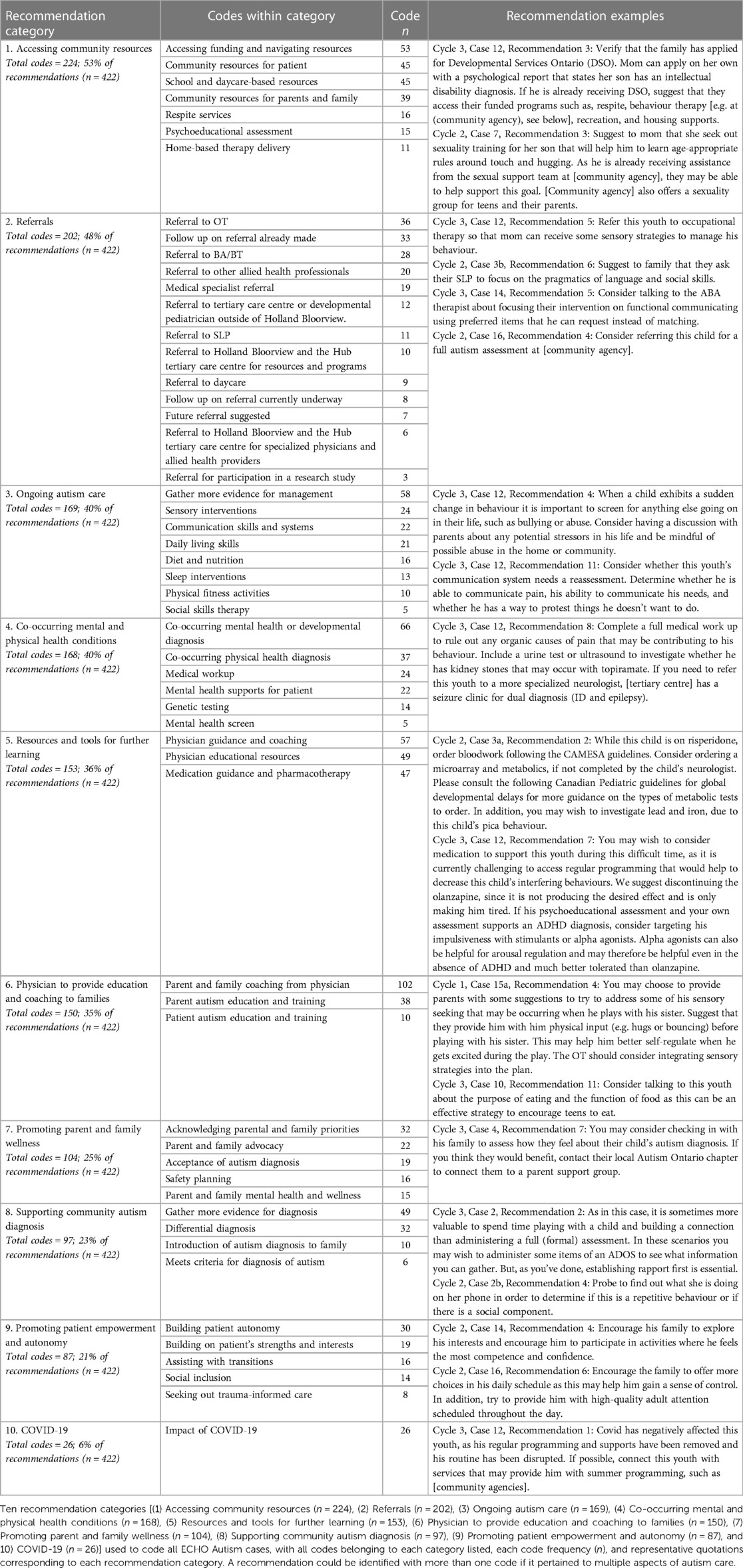

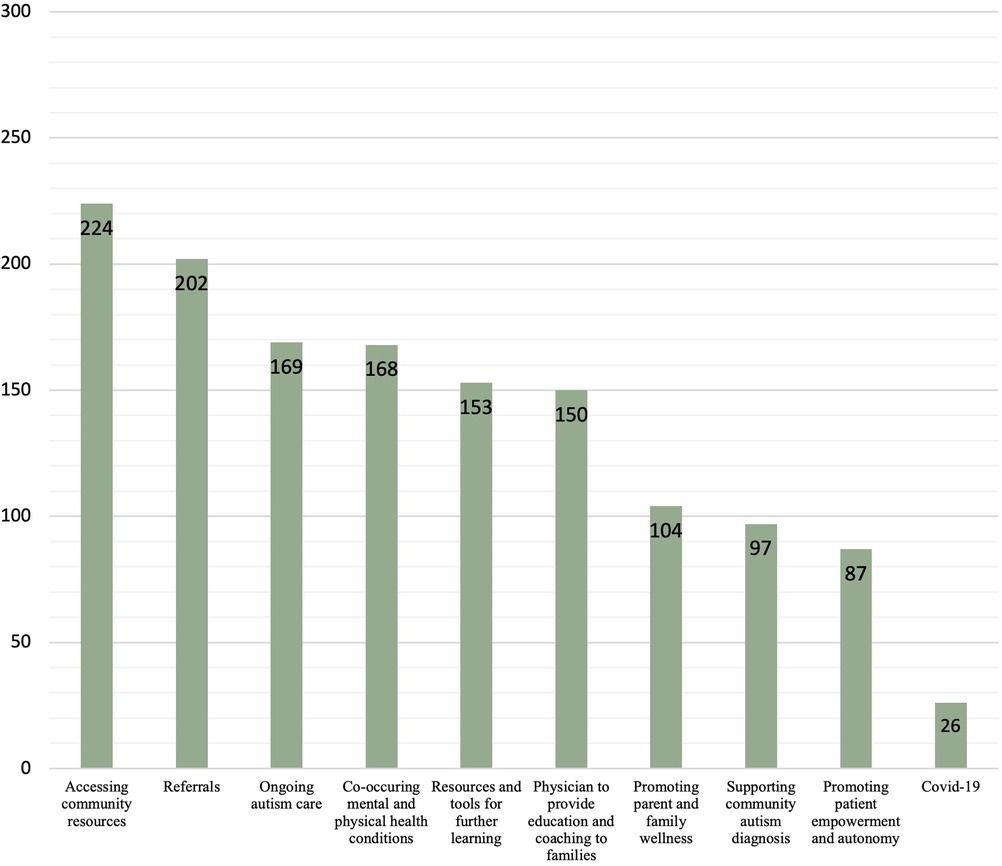

Results: Of the 422 recommendations stemming from 62 cases, we identified 55 codes across ten broad categories. Categories included accessing community resources (n = 224), referrals to allied health and other providers (n = 202), ongoing autism care (n = 169), co-occurring mental and physical health conditions (n = 168), resources and tools for further learning (n = 153), physician to provide education and coaching to families (n = 150), promoting parent and family wellness (n = 104), supporting community autism diagnosis (n = 97), promoting patient empowerment and autonomy (n = 87), and COVID-19 (n = 26).

Conclusion: This is the first time that recommendations from ECHO Autism have been characterized and grouped into categories. Our results show that advice for autism identification and management spans many different facets of community-based care. Specific attention should be paid to providing continued access to education about autism, streamlining referrals to allied health providers, and a greater focus on patient- and family-centered care. Physicians should have continued access to autism education to help fill knowledge gaps and to facilitate families' service navigation.

Introduction

Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition affecting one in 66 children and youth aged five to 17 in Canada (1). The complex nature of autism can lead to a difficult journey in the healthcare system for families. This includes unmet needs for healthcare and family supports, delayed or foregone care, and difficulty obtaining access to medical care and allied health services (2). Data from the United States National Survey of Children's Health showed that autistic children have a four times higher risk of unmet healthcare needs compared to children without disabilities (3). A survey collecting data from caregivers of autistic children found that around one third experienced unmet healthcare service needs like speech-language therapy, occupational therapy, and social skills training, while almost one quarter expressed needs for family support services such as respite care and parent/sibling support groups (4). Unmet healthcare needs may also extend to co-occurring mental health and physical health conditions, including dental health (5). Co-occurring mental health conditions in autistic individuals have been reported at an increased prevalence compared to the general population, including attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (28%), anxiety disorders (20%), sleep-wake disorders (13%), disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders (12%), and depressive disorders (11%) (6).

In the Canadian context, community practitioners caring for autistic individuals may include primary care physicians, consultant pediatricians, subspecialists, nurse practitioners, and other allied health providers situated outside of tertiary care centres (7). While primary care physicians have a wide scope of practice, which includes health promotion, preventative care, and the diagnosis and treatment of a variety of illnesses and injuries, consultant pediatricians are consulted by a child's primary care physician if there are concerns that require more specialized care (8). If the consultant pediatrician does not feel that they can provide the necessary expertise, they may refer to a subspecialist, such as a developmental pediatrician or multidisciplinary team. Community practitioners have reported a lack of knowledge, competence, and comfort in treating autistic children, contributing to these unmet healthcare needs (9, 10). Factors associated with discomfort in autism screening and diagnosing children include time limitations, a lack of familiarity with screening tools, and perceived difficulty of use (11, 12). Parents are reported to consult an average of three to five professionals before obtaining an autism diagnosis, with the time from first concern to diagnosis ranging from 12 to 55 months (13). Importantly, early diagnosis and therapies are associated with improvements in cognition, language, daily living skills, and social behaviour (14). The Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) has stressed the importance of conferring a diagnosis at the earliest age possible, and highlights the need to expand autism diagnostic capacity by including community practitioners (15). Beyond diagnosis, the clinical complexity of autism care and associated co-occurring conditions may be difficult to address in the community, contributing to higher rates and durations of hospitalizations, greater expenditures, and greater use of psychotropic medications (16–20). There is a critical need to improve community-based autism care in early identification, diagnosis, and management of common issues such as sleep, constipation, and co-occurring neurodevelopmental and mental health conditions (16).

To address these shortcomings, targeted autism training programs may effectively educate community-based professionals on diagnosis and management. One widely used training program is the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) model, which aims to reduce barriers between specialists and community providers in treating complex conditions. ECHO uses videoconferencing to create learning communities through didactic learning, mentoring, and participant-generated case presentations and discussions. The ECHO model was first developed in 2003 by Dr. Sanjeev Arora, with its original application used in improving treatment outcomes for patients with hepatitis C virus (21).

ECHO Ontario Autism is a specific learning program under the ECHO Autism umbrella. When Project ECHO Ontario Autism was first developed, the curriculum from the original ECHO Autism pilot, designed in the United States, was expanded on and adapted to include the diagnosis of autism. This adaptation was made to meet the diagnostic needs in the Ontario community and increase the capacity of community practitioners to provide autism diagnoses. This led to the creation of two distinct learning objectives of Project ECHO Ontario Autism, in consultation with the Ontario Ministry of Health. Firstly, the program aims to build province-wide community capacity and ability to screen, diagnose, and manage children and youth with autism in Ontario (22). Secondly, the programs hopes to reduce wait times for specialized care by increasing community provider capacity, thereby reserving specialized care for complex cases (22). Furthermore, the team realized an important voice of autistic representation was needed, and prioritized the inclusion of autistic advocates to offer the team and participants a valuable lived experience perspective of the diagnostic process and navigating the system. While recent iterations of ECHO Autism programs have included elements of diagnosis and inclusion of autistic advocates, including ECHO Autism STAT and ECHO Autism Transition, respectively, ECHO Ontario Autism combines these factors while placing them in the contextual needs of the Ontario healthcare system (23, 24). In each session, a participant presents a challenging case of one of their patients to other participating community providers and an interdisciplinary “Hub” team composed of autistic advocates, parents of autistic children, and interdisciplinary autism specialists. Community participants and the Hub team discuss the case and co-develop recommendations for best-practice care, which are summarized by facilitators and disseminated to participants after each session.

Studies of the ECHO Autism program with primary care providers in Missouri found significant improvements in clinicians’ relationships with their patients and families, increased rates of accepting autism referrals for diagnostic evaluation, an increase in their autism caseload, increased self-efficacy scores from pre- to post-ECHO training, greater use of autism-specific resources, and higher participant-reported satisfaction (23, 25). A multi-centre North American trial demonstrated improved clinician knowledge and self-efficacy, although no changes were seen in autism screening or management of co-occurring conditions (26). A more recent study found that ECHO Autism facilitated successful integration of expertise in a remote and COVID-19-friendly fashion to improve knowledge and clinical practice (27). Reflective qualitative analyses of learning experiences of ECHO Autism participants in India and Hub facilitators in the United States have produced helpful markers of program evaluation and strengths (28, 29).

Despite existing studies, there remain important aspects of ECHO Autism that have not been explored. ECHO Autism case recommendations have not yet undergone qualitative or summative study; such examination is important to identify ongoing gaps in autism knowledge and teaching, with implications across medical autism training. Each ECHO session generates a unique list of recommendations, which provides an important data set for learning about post-training education and support needs for community-based clinicians. Existing qualitative evaluations of the ECHO learning model have focused on more traditional sources of information such as interviews and focus groups with ECHO participants, but no known studies have examined ECHO recommendations (30). As the data presented in our study are derived directly from the ECHO program and sessions, rather than participant reflections, our data set identifies timely on-the-ground care needs for autistic individuals and comprises a valuable dataset representing real-world challenges that clinicians are actively facing to best understand and support these care needs. The objective of our study was to characterize and categorize recommendations from Project ECHO Autism Ontario case discussions.

Materials and methods

Project ECHO Ontario Autism

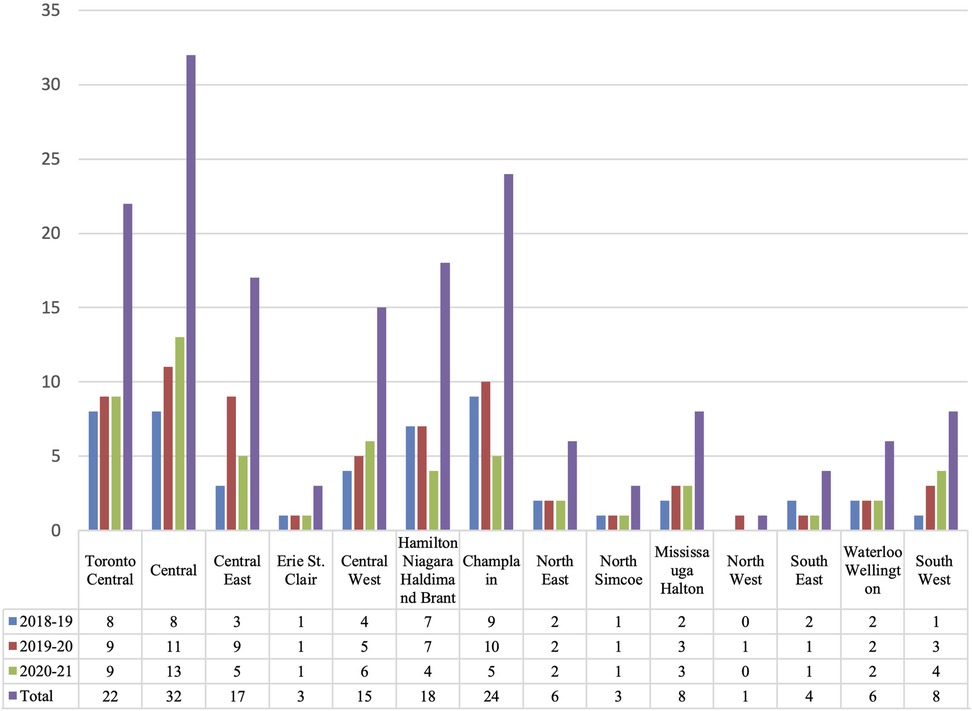

ECHO Autism is currently offered through Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital and funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health. At the time of writing this manuscript, three cycles of ECHO were completed from October 2018 to July 2021. Participation was steady across all three cycles, with 53, 51, and 43 attendees in at least one session in cycles 1, 2, and 3, respectively. ECHO Ontario Autism participation was open to any physician or nurse practitioner in Ontario, Canada. Information about the ECHO program was distributed through the Pediatric Section of the Ontario Medical Association. Demographic data about the professional disciplines of participants across all three cycles are presented in Table 1. Participants joined from across Ontario, with most located in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). Demographic data about the geographic location of Ontario participants, organized by Local Health Integration Network, are presented in Figure 1. There were also a select few observers from other provinces and countries including Saskatchewan, Québec, British Columbia, The Bahamas, and India. Based on our inclusion criteria of participants working as physicians or nurse practitioners, we did not collect additional information about socioeconomic status and educational attainment for ECHO participants due to the homogenous and high level of education of our cohort.

Figure 1. ECHO Ontario Autism participants by LHIN (n). Demographic information of ECHO Autism participants across all three cycles (2018–2019, 2019–2020, 2020–2021) by number of participants (n) from each Local Health Integration Network, including: (1) Toronto Central (n = 22), (2) Central (n = 32), (3) Central East (n = 17), (4) Erie/St. Clair (n = 3), (5) Central West (n = 15), (6) Hamilton/Niagara/Haldimand/Brant (n = 18), (7) Champlain (n = 24), (8) North East (n = 6), (9) North Simcoe (n = 3), (10) Mississauga/Halton (n = 8), (11) North West (n = 1), (12) South East (n = 4), (13) Waterloo/Wellington (n = 6), and (14) South West (n = 8).

Research ethics approval was obtained from the Holland Bloorview Research Ethics Board (REB #: 0267). All ECHO Autism case presentations and resulting recommendations were presented without any personal identifying information to ensure confidentiality. The recommendations were generated by the ECHO Autism team for distribution to ECHO participants; for this reason, we did not seek consent from the ECHO participants.

Description of data set

Each ECHO session consists of 1–2 case presentations (cycle 1: 24 cases, cycle 2: 20 cases, cycle 3: 18 cases). Recommendations were informed by multiple verbal comments made by participants during group discussions in each session, with recommendations being uniquely generated for each case. ECHO Autism staff took notes during the session and formulated written recommendations after the session, which were then edited by Hub leads before distribution to participants. There were between 4 and 16 recommendations generated for each of the 62 ECHO cases, with 422 total recommendations forming our data set. The Hub team for each session consisted of the following members: an autistic advocate, one to two family advisors, a developmental pediatrician, a child neurologist, a psychologist, a registered nurse, a board-certified behaviour analyst, an occupational therapist, and a social worker. All Hub members, including autistic advocates and family advisors, were directly involved in the process of discussing and generating the recommendations used in this study.

Summative approach

We adopted a social constructivist paradigm, acknowledging that as researchers we actively participated in the generation of knowledge (31). This is particularly important given that members of the research team routinely participated in ECHO Autism sessions and have contributed to the generation and writing of recommendations.

A comprehensive content analysis of all Project ECHO Ontario Autism case recommendations was completed using an inductive approach to develop codes and categories of recommendations (32). We employed a summative content analysis approach, in which codes are quantified by calculated frequency counts and interpreted to draw conclusions from the contextual usage of the codes (33).

Data analysis

Two research team members (one medical student and one ECHO staff member) independently read the recommendations once through and made notes on their first impressions. Next, the two team members developed an original coding guide using recommendations from five ECHO cases that were carefully chosen to ensure a representative sample of cases across all three cycles. The guide was reviewed with a third team member (ECHO Ontario Autism lead and Hub developmental pediatrician) and then was continuously updated during the analytic process. Please see the Supplementary Material for the final version of the coding guide.

Once the initial guide was developed, two research staff independently coded every case and recommendation, meeting regularly to compare and contrast the codes. Any discrepancies were reviewed and resolved with an ECHO lead, including revision of the coding guide and addition of new codes. The team then met to group like codes and identify overarching categories of codes in a hierarchical structure. Finally, the frequencies of each code and category were calculated. Due to the multifaceted nature of the recommendations, a recommendation could be identified with more than one code if it pertained to multiple aspects of autism care. Throughout the entire process, we generated definitions for the categories and codes and kept track of all decisions and changes through analytic memoing. Coding discrepancies between coders that were resolved with the ECHO lead were tracked and used to calculate inter-rater reliability.

Results

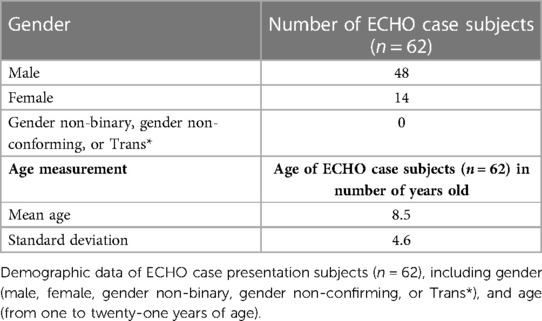

Demographic information about case subjects of the ECHO Autism case presentations are presented in Table 2. Table 2 showcases gender and mean age of all 62 case subjects. Of the 62 cases, 48 (77%) featured male patients, while 14 (23%) featured female patients. Case subject ages ranged from 1.4 years to 21 years. The mean age was 8.5 years, with a standard deviation of 4.6.

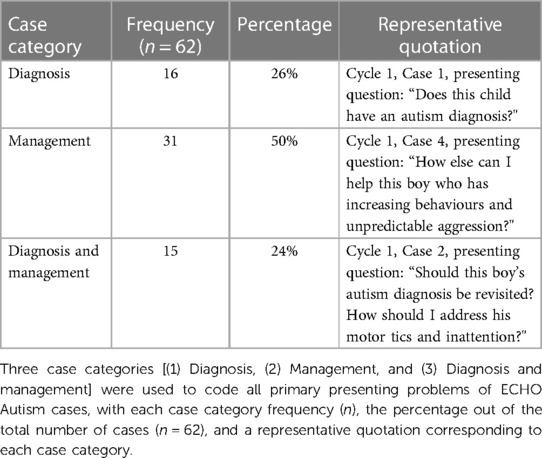

Primary presenting problems of each case were summarized by 3 case codes (Table 3), while case recommendations were described by 55 recommendation codes (Table 4) included in the coding guide, with recommendation codes grouped into ten overarching categories. The three case codes were: (1) diagnosis, (2) management, and (3) both diagnosis and management. Categories of recommendation codes included, in descending order of frequency (n/422 total recommendations): (1) accessing community resources (n = 224; 53%), (2) referrals (n = 202; 48%), (3) ongoing autism care (n = 169; 40%), (4) co-occurring mental and physical health conditions (n = 168; 40%), (5) resources and tools for further learning (n = 153; 36%), (6) physician to provide education and coaching to families (n = 150; 35%), (7) promoting parent and family wellness (n = 104; 25%), (8) supporting community autism diagnosis (n = 97; 23%), (9) promoting patient empowerment and autonomy (n = 87; 21%), and (10) COVID-19 (n = 26; 6%) (see Figure 2). Of the 1,380 total in-text codes, 68 (4.93%) contained discrepancies that were brought to the ECHO lead for resolution. Therefore, the percent agreement between the two principal coders was 95%.

Figure 2. Frequency of categories in recommendations (n). Frequency of recommendation categories (n) in absolute value of total recommendations (n = 422). Categories include: (1) Accessing community resources (n = 224), (2) Referrals (n = 202), (3) Ongoing autism care (n = 169), (4) Co-occurring mental and physical health conditions (n = 168), (5) Resources and tools for further learning (n = 153), (6) Physician to provide education and coaching to families (n = 150), (7) Promoting parent and family wellness (n = 104), (8) Supporting community autism diagnosis (n = 97), (9) Promoting patient empowerment and autonomy (n = 87), and (10) COVID-19 (n = 26).

The most common category was accessing community resources. Recommendations in this category included parent and sibling support groups, respite services, funding/tax benefits, school and daycare-based resources, requesting a psychoeducational assessment through the school board, and home-based therapy delivery. An example of a representative recommendation in this category is: “Suggest to mom that she seek out sexuality training for her son that will help him to learn age-appropriate rules around touch and hugging. As he is already receiving assistance from the sexual support team at [community agency], they may be able to help support this goal. [Community agency] also offers a sexuality group for teens and their parents.”

The second most common category was referrals, which included all references made to referrals to various specialists and allied health providers. Common recommendations were for referrals to be immediately made for speech language pathologists (n = 11), occupational therapists (n = 36), behavioural therapists (n = 28), medical specialists (n = 19), and allied health professionals including dieticians, social workers, audiologists, and psychologists (n = 20). Please see Table 4 for the complete list of referrals. Recommendations in this category could also include future referrals (n = 7), checking in on a referral in-progress (n = 8), or noting that the ECHO participant had already made the necessary referral (n = 33). One example recommendation suggests: “Refer this youth to occupational therapy so that mom can receive some sensory strategies to manage his behaviour.”

The next category of ongoing autism care included building daily living skills such as eating, bathing, and dressing, communication skills and systems, development of social skills, sensory interventions, and prioritizing healthy lifestyle modifications such as physical fitness, nutrition, and sleep habits. An example of a recommendation focusing on communication skills urges participants to “Consider whether this youth's communication system needs a reassessment. Determine whether he is able to communicate pain, his ability to communicate his needs, and whether he has a way to protest things he doesn’t want to do.”

Following this, the next category of recommendations captured diagnosis and management of co-occurring conditions. The most common mental health conditions included depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, while co-occurring neurodevelopmental disorders included attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and a learning or intellectual disability. The most common physical health conditions included feeding and gastrointestinal difficulties, weight-related issues, hearing impairments, and seizures. This category also included recommendations for investigations, such as genetic and medical testing. For example, one recommendation suggested that a clinician “Complete a full medical work up to rule out any organic causes of pain that may be contributing to his behaviour… If you need to refer this youth to a more specialized neurologist, [tertiary centre] has a seizure clinic for dual diagnosis (ID and epilepsy).”

The next category captured resources and tools for further learning provided to physician participants. This included recommendations for education programs/materials, such as workshops, training sessions, books, or best practice guidelines. For example, one recommendation advised a clinician that “While this child is on risperidone, order bloodwork following the CAMESA guidelines. Consider ordering a microarray and metabolics, if not completed by the child's neurologist. Please consult the following Canadian Pediatric guidelines for global developmental delays for more guidance on the types of metabolic tests to order.” Recommendations providing education about psychoactive medications were particularly common (n = 47).

The following category focused on recommendations asking the physician to provide education and coaching to families. Recommendations could be for resources, educational materials, and informal suggestions directed to families and patients to help them better understand autism and self-care strategies. One provider was advised that “You may choose to provide parents with some suggestions to try to address some of his sensory seeking that may be occurring when he plays with his sister. Suggest that they provide him with him physical input (e.g., hugs or bouncing) before playing with his sister.”

The next category centered around promoting parent and family wellness, which included a variety of recommendations centering the family's needs and how to best support them. One recommendation suggested that “You may consider checking in with his family to assess how they feel about their child's autism diagnosis. If you think they would benefit, contact their local Autism Ontario chapter to connect them to a parent support group.” Additional recommendations spoke to helping families with pursuing advocacy initiatives, caring for their own mental health, acknowledging parent and family priorities, and family safety planning.

Nearly one quarter of recommendations pertained to community-based autism diagnosis, such as encouraging the physician to gather more information from various sources to inform and/or proceed with a possible diagnosis, navigating the differential diagnosis, indicating that the patient meets autism diagnostic criteria, and introducing an autism diagnosis to a child and their family. One community clinician was advised that “… it is sometimes more valuable to spend time playing with a child and building a connection than administering a full (formal) assessment. In these scenarios you may wish to administer some items of an ADOS to see what information you can gather. But, as you’ve done, establishing rapport first is essential.”

A particularly salient category of recommendations spoke to promoting patient empowerment and autonomy, with recommendations pertaining to championing social inclusion, assisting with major life transitions, building personal autonomy, acknowledging strengths and interests, and using a trauma-informed care approach. Examples of these recommendations include: “Encourage his family to explore his interests and encourage him to participate in activities where he feels the most competence and confidence” and “Encourage the family to offer more choices in his daily schedule as this may help him gain a sense of control.”

Lastly, a COVID-19 category was added part way through cycle 2, which corresponded with the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 category was created to highlight resources which were either created specifically during the pandemic, or were adapted to online service delivery, especially virtual therapy and social activities. This contrasts with general community resources which existed prior to COVID-19 or were not known to be delivered virtually. One youth's experience with COVID-19 was described as follows: “Covid has negatively affected this youth, as his regular programming and supports have been removed and his routine has been disrupted. If possible, connect this youth with services that may provide him with summer programming, such as [community agencies].”

Discussion

This is the first time that recommendations from ECHO Autism have been characterized and categorized. Our results demonstrate several key areas of learning, including common categories of accessing community resources, making appropriate referrals, and providing ongoing autism care. These categories and their relative frequencies provide important insights into knowledge and care gaps for autistic children and youth.

Our categories are consistent with key areas identified in other studies. Firstly, one study used an originally-developed questionnaire with similar overarching categories to assess self-efficacy of physicians participating in ECHO Autism (25). The questionnaire had five domains, including autism screening and identification, referrals, resources, assessment and treatment of both medical and psychiatric co-occurring conditions, and additional aspects of care for autistic children, all of which are domains replicated in our analysis (25). A Canadian study highlighted several provider-perceived needs for autism identification, including enhanced autism education and greater accessibility of community resources, which were also common categories of recommendations in our study (11). Studies investigating perspectives of Canadian pediatricians on autism diagnosis reported many findings consistent with the ECHO recommendations related to diagnosis, such as strategies for introducing an autism diagnosis to families (34, 35).

Our results reinforce that autism is a multifaceted, heterogeneous condition that often requires input from diversely-skilled professionals. A study investigating Ontario physicians’ perspectives on providing autism care reported that working with interprofessional teams was a facilitator in caring for this population (36). Although interdisciplinary input is ideal, the CPS highlights how access to these resource-intensive teams is scarce and can lead to delays in diagnosis (15). ECHO Autism enables providers to access an interprofessional team despite geographical location, facilitating access to interdisciplinary and specialized knowledge.

Our findings also highlight the importance of access to resources. ECHO participants joined from across Ontario, with presumed varying geographic access to resources. Even still, pediatricians in urban areas expressed difficulties navigating autism resources, which has been previously documented (12). Despite the existence of local autism resources, physicians and families may not be aware of their options, which speaks to the need for effective knowledge sharing of available resources to all stakeholders. Research shows that physicians continue to play a key role in resource dissemination, with parents needing assistance to find reliable autism information (37). A particularly salient finding of our data is a common recommendation for physicians to follow up on referrals that were already made. This points to the increased workload of physicians to be a point of contact between families and providers and spend additional time when communication breaks down in the system of care.

Our findings further demonstrate that clinicians can do more to advocate for autistic children and youth to have more agency and control of their lives, including facilitating social inclusion, building personal autonomy, and acknowledging strengths and interests. Other work has also demonstrated the importance of patient-centered care for autistic patients, including ensuring effective communication, fostering healthy patient-physician relationships, and enabling patient self-management (38). Our findings highlight the importance of training physicians to include family members in autism care; several studies also cite the benefits of shared decision-making, including higher parent satisfaction (39, 40).

Our results have identified post-training gaps in clinical knowledge. Similarly, studies show that autism education remains inadequate in pediatrics residency programs across North America (41). Ontario physicians surveyed about barriers to providing autism care reported a limited focus on autism in medical school and professional development training (36). A study validating objectives of Canadian pediatrics residency programs found that pediatricians reported their preparation for practice was less than adequate in the domain of development and behaviour competencies, including autism (42). Our results suggest that ongoing medical education about autism is needed, as well as guidance about available resources and training to encourage family wellness and prioritize patient empowerment in this population. Based on previously noted comparisons to findings from similar studies across Canada and North America, we believe our results are generalizable to health systems and populations with similar structures to that of Ontario, Canada.

In the international health context, a recent systematic review reported the global prevalence of autism to be 100 per 10,000 individuals (43). While most research into diagnosis and treatment of autism is based on studies in high-income countries such as Canada, similarities between global challenges and our findings exist. For example, one author notes how early detection of autism continues to be a major global challenge, both in high- and low-income countries (44). Furthermore, barriers in access to care including delayed diagnosis, challenges in navigating health systems, and the lack of services and care providers are common issues encountered globally, which are echoed in our results (44). Another similarity stems from available diagnostic and educational services being concentrated in major urban hubs and capital cities, as pointed out in an Ethiopian study (45). Our findings echoed the overrepresentation of ECHO participants and resources from urban areas compared to rural areas. Finally, one study highlights how the innovative use of technology may have the potential to better meet the global needs of autistic individuals and their families (46). ECHO Autism researchers have previously noted the program's flexibility and adaptability to a global context (47).

Our study's key findings point to a greater need for accessibility and awareness of community autism resources and the importance of streamlining allied health referrals, which may be applicable to providers practicing in differently structured healthcare systems than in our study. We believe targeted medical education through programs like ECHO Autism and similar models may benefit practitioners worldwide. ECHO Autism may be further tailored to meet the individual care needs of global communities and systems, such as aiming to increase community autism diagnostic capacity as was the objective with ECHO Ontario Autism, focusing on ongoing management strategies, or a combination of these. Furthermore, engaging in collaborative practice models and resource sharing may help practitioners address our study's recommendations.

Our study was not without limitations. While all ECHO participants had an education level equivalent to that of a medical doctor (MD) or nurse practitioner (NP) practicing in Ontario, ECHO participants may have a higher baseline level of engagement and interest in autism education. Therefore, the cases and knowledge gaps of presenting clinicians may not be representative of all Ontario clinicians. Furthermore, since most participants were based in the GTA, urban perspectives may be over-represented in our findings. Our research team was mostly comprised of ECHO Autism Hub team members and staff, which influenced the interpretation of the data. The data set was composed of summarized key recommendations discussed at each session, which may not represent the diverse set of voices present and capture all individual perspectives that also contributed to learning in the program.

Our results show there is still important work to do in educating clinicians and families to effectively navigate existing autism resources and improve access. Key takeaways include providing continued access to education about autism, streamlining referrals to allied health providers, and having a greater focus on patient autonomy and family well-being.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

This study involved was reviewed and approved by the Holland Bloorview Research Ethics Board, Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada.

Author contributions

AJ helped with study conception and design, data collection, data analysis, drafting of the manuscript, and revising of the manuscript. LK and AP helped with data collection, data analysis, and revising of the manuscript. EA and JB helped with revising of the manuscript. Finally, MP helped with study conception and design, data collection, data analysis, and revising of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the entire ECHO Autism Hub team at our centre for their time, dedication, and expertise on providing recommendations for these cases, including Maddy Dever, Susan Cosgrove, Adrienne Zarem, Philippa Howell, Gunjan Seth, Moira Pena, Justine Wiegelmann, Erica Laframboise, Cathy Petta, and Robin Hermolin. We would also like to thank the ECHO Autism participants for attending and seeking out knowledge and support for their patients. Finally, we would like to thank Andrea Guerin for her encouragement and help in connecting the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fresc.2023.1096314/full#supplementary-material.

References

1. Public Health Agency of Canada. Autism spectrum disorder among children and youth in Canada (2018). Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/autism-spectrum-disorder-children-youth-canada-2018.html#shr-pg0 (Accessed December 17, 2021).

2. Kogan MD, Strickland BB, Blumberg SJ, Singh GK, Perrin JM, van Dyck PC. A national profile of the health care experiences and family impact of autism spectrum disorder among children in the United States, 2005–2006. Pediatrics. (2008) 122(6):e1149–58. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1057

3. Karpur A, Lello A, Frazier T, Dixon PJ, Shih AJ. Health disparities among children with autism spectrum disorders: analysis of the national survey of children’s health 2016. J Autism Dev Disord. (2019) 49:1652–64. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3862-9

4. Srinivasan S, Ekbladh A, Freedman B, Bhat A. Needs assessment in unmet healthcare and family support services: a survey of caregivers of children and youth with autism spectrum disorder in Delaware. Autism Res. (2021) 14(8):1736–58. doi: 10.1002/aur.2514

5. McKinney CM, Nelson T, Scott JM, Heaton LJ, Vaughn MG, Lewis CW. Predictors of unmet dental need in children with autism spectrum disorder: results from a national sample. Acad Pediatr. (2014) 14(6):624–31. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.06.023

6. Lai MC, Kassee C, Besney R, Bonato S, Hull L, Mandy W, et al. Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6(10):819–29. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30289-5

7. Young E, Green L, Goldfarb R, Hollamby K, Milligan K. Caring for children with mental health or developmental and behavioural disorders: perspectives of family health teams on roles and barriers to care. Can Fam Physician. (2020) 66(10):750–7.33077456

8. Health Canada. About primary health care (2012). Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/primary-health-care/about-primary-health-care.html (Accessed February 4, 2023).

9. Carbone PS, Behl DD, Azor V, Murphy NA. The medical home for children with autism spectrum disorders: parent and pediatrician perspectives. J Autism Dev Disord. (2010) 40(3):317–24. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0874-5

10. Golnik A, Ireland M, Borowsky IW. Medical homes for children with autism: a physician survey. Pediatrics. (2009) 123(3):966–71. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1321

11. Ws A, Zwaigenbaum L, Nicholas D, Sharon R. Factors influencing autism spectrum disorder screening by community paediatricians. Paediatr Child Health. (2015) 20(5):e20–4. doi: 10.1093/pch/20.5.e20

12. Ip A, Dupuis A, Anagnostou E, Loh A, Dodds T, Munoz A, et al. General paediatric practice in autism spectrum disorder screening in Ontario, Canada: opportunities for improvement. Paediatr Child Health. (2019) 26(1):e33–8. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxz150

13. Makino A, Hartman L, King G, Wong PY, Penner M. Parent experiences of autism spectrum disorder diagnosis: a scoping review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. (2021) 8:267–84. doi: 10.1007/s40489-021-00237-y

14. Elder JH, Kreider CM, Brasher SN, Ansell M. Clinical impact of early diagnosis of autism on the prognosis and parent-child relationships. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2017) 10:283–92. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S117499

15. Canadian Paediatric Society. Early detection for autism spectrum disorder in young children (2019). Available at: https://www.cps.ca/en/documents/position/asd-early-detection (Accessed December 17, 2021).

16. Lake JK, Denton D, Lunsky Y, Shui AM, Veenstra-VanderWeele J, Anagnostou E. Medical conditions and demographic, service and clinical factors associated with atypical antipsychotic medication use among children with an autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. (2017) 47(5):1391–402. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3058-8

17. Buescher AV, Cidav Z, Knapp M, Mandell DS. Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatr. (2014) 168(8):721–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.210

18. Mandell DS, Morales KH, Marcus SC, Stahmer AC, Doshi J, Polsky DE. Psychotropic medication use among medicaid-enrolled children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. (2008) 121(3):e441–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0984

19. Mandell DS. Psychiatric hospitalization among children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. (2008) 38(6):1059–65. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0481-2

20. Park SY, Cervesi C, Galling B, Molteni S, Walyzada F, Ameis SH, et al. Antipsychotic use trends in youth with autism spectrum disorder and/or intellectual disability: a meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2016) 55(6):456–68.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.03.012

21. Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G, Deming P, Kalishman S, Dion D, et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med. (2011) 364(23):2199–207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009370

22. Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. ECHO Autism (2020). Available at: https://hollandbloorview.ca/services/programs-services/echo-autism (Accessed December 17, 2021).

23. Mazurek MO, Curran A, Burnette C, Sohl K. ECHO Autism STAT: accelerating early access to autism diagnosis. J Autism Dev Disord. (2019) 49(1):127–37. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3696-5

24. Mazurek MO, Stobbe G, Loftin R, Malow BA, Agrawal MM, Tapia M, et al. ECHO Autism transition: enhancing healthcare for adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. (2020) 24(3):633–44. doi: 10.1177/1362361319879616

25. Mazurek MO, Brown R, Curran A, Sohl K. ECHO Autism. Clin Pediatr (Phila). (2017) 56(3):247–56. doi: 10.1177/0009922816648288

26. Mazurek MO, Parker RA, Chan J, Kuhlthau K, Sohl K, ECHO Autism Collaborative. Effectiveness of the extension for community health outcomes model as applied to primary care for autism: a partial stepped-wedge randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. (2020) 174(5):e196306. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.6306

27. Brandt L, Warne-Griggs M, Hoffman K, Popejoy L, Mutrux ER. Embracing the power of show-me ECHO learning communities to transform clinical practice in Missouri. Mo Med. (2020) 117(3):216–21.32636553

28. Sengupta K, Lobo L, Krishnamurthy V. Physician voices on ECHO autism India-evaluation of a telementoring model for autism in a low-middle income country. J Dev Behav Pediatr. (2022) 43(6):335–45. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000001060

29. Vinson AH, Iannuzzi D, Bennett A, Butter EM, Curran AB, Hess A, et al. Facilitator reflections on shared expertise and adaptive leadership in ECHO autism: center engagement. J Contin Educ Health Prof. (2022) 42(1):e53–9. doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000395

30. Agley J, Delong J, Janota A, Carson A, Roberts J, Maupome G. Reflections on project ECHO: qualitative findings from five different ECHO programs. Med Educ Online. (2021) 26(1):1936435. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2021.1936435

31. Appleton JV, King L. Journeying from the philosophical contemplation of constructivism to the methodological pragmatics of health services research. J Adv Nurs. (2002) 40(6):641–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02424.x

32. Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. (2006) 27(2):237–46. doi: 10.1177/1098214005283748

33. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. (2005) 15(9):1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

34. Penner M, King GA, Hartman L, Anagnostou E, Shouldice M, Hepburn CM. Community general pediatricians’ perspectives on providing autism diagnoses in Ontario, Canada: a qualitative study. J Dev Behav Pediatr. (2017) 38(8):593–602. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000483

35. Das J, Hartman L, King G, Jones-Stokreef N, Moore Hepburn C, Penner M. Perspectives of Canadian rural consultant pediatricians on diagnosing autism spectrum disorder: a qualitative study. J Dev Behav Pediatr. (2022) 43(3):149–58. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000001006

36. Ghaderi G, Watson SL. Autism spectrum disorder knowledge, training and experience: Ontario physicians’ perspectives about what helps and what does not. J Dev Disabil. (2019) 24(2):51–60.

37. Hall CM, Culler ED, Frank-Webb A. Online dissemination of resources and services for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs): a systematic review of evidence. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. (2016) 3(4):273–85. doi: 10.1007/s40489-016-0083-z

38. Iannuzzi D, Kopecky K, Broder-Fingert S, Connors SL. Addressing the needs of individuals with autism: role of hospital-based social workers in implementation of a patient-centered care plan. Health Soc Work. (2015) 40(3):245–8. doi: 10.1093/hsw/hlv032

39. Golnik A, Maccabee-Ryaboy N, Scal P, Wey A, Gaillard P. Shared decision making: improving care for children with autism. Intellect Dev Disabil. (2012) 50(4):322–31. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-50.4.322

40. Gabovitch EM, Curtin C. Family-centered care for children with autism spectrum disorders: a review. Marriage Fam Rev. (2009) 45(5):469–98. doi: 10.1080/01494920903050755

41. Major NE. Autism education in residency training programs. AMA J Ethics. (2015) 17(4):318–22. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2015.17.4.medu1-1504

42. Amin HJ, Singhal N, Cole G. Validating objectives and training in Canadian paediatrics residency training programmes. Med Teach. (2011) 33(3):e131–44. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.542525

43. Zeidan J, Fombonne E, Scorah J, Ibrahim A, Durkin MS, Saxena S, et al. Global prevalence of autism: a systematic review update. Autism Res. (2022) 15(5):778–90. doi: 10.1002/aur.2696

44. Hahler EM, Elsabbagh M. Autism: a global perspective. Curr Dev Disord. (2015) 2:58–6. doi: 10.1007/s40474-014-0033-3

45. Tekola B, Baheretibeb Y, Roth I, Tilahun D, Fekadu A, Hanlon C, et al. Challenges and opportunities to improve autism services in low-income countries: lessons from a situational analysis in Ethiopia. Glob Ment Health (Camb). (2016) 3:e21. doi: 10.1017/gmh.2016.17

46. de Vries PJ. Thinking globally to meet local needs: autism spectrum disorders in Africa and other low-resource environments. Curr Opin Neurol. (2016) 29(2):130–6. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000297

Keywords: Autism, ECHO, diagnosis, summative analysis, medical education, health services

Citation: Jane A, Kanigsberg L, Patel A, Eldon S, Anagnostou E, Brian J and Penner M (2023) Summative content analysis of the recommendations from Project ECHO Ontario Autism. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 4:1096314. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2023.1096314

Received: 12 November 2022; Accepted: 9 March 2023;

Published: 30 March 2023.

Edited by:

Eric J. Moody, University of Wyoming, United StatesReviewed by:

Micah Mazurek, University of Virginia, United StatesChetwyn C. H. Chan, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

© 2023 Jane, Kanigsberg, Patel, Eldon, Anagnostou, Brian and Penner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Melanie Penner bXBlbm5lckBob2xsYW5kYmxvb3J2aWV3LmNh

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Translational Research in Rehabilitation, a section of the journal Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences

Abbreviations ABA, Applied Behaviour Analysis; ADHD, Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ADOS, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; BA/BT, Behaviour Analyst/Behaviour Therapist; CAMESA, Canadian Alliance for Monitoring Effectiveness and Safety of Antipsychotics in Children; CPS, Canadian Paediatric Society; DSO, Developmental Services Ontario; ECHO, Extensions of Community Healthcare Outcomes; GTA, Greater Toronto Area; ID, Intellectual disability; LHIN, Local Health Integration Network; MD, Medical Doctor; NP, Nurse Practitioner; OT, Occupational therapist; REB, Research Ethics Board; SLP, Speech language pathologist.

Alanna Jane

Alanna Jane Lisa Kanigsberg2

Lisa Kanigsberg2 Evdokia Anagnostou

Evdokia Anagnostou Jessica Brian

Jessica Brian Melanie Penner

Melanie Penner