- 1Faculty of Applied Economics, University of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (UCASS), Beijing, China

- 2School of Software and Microelectronics, Peking University, Beijing, China

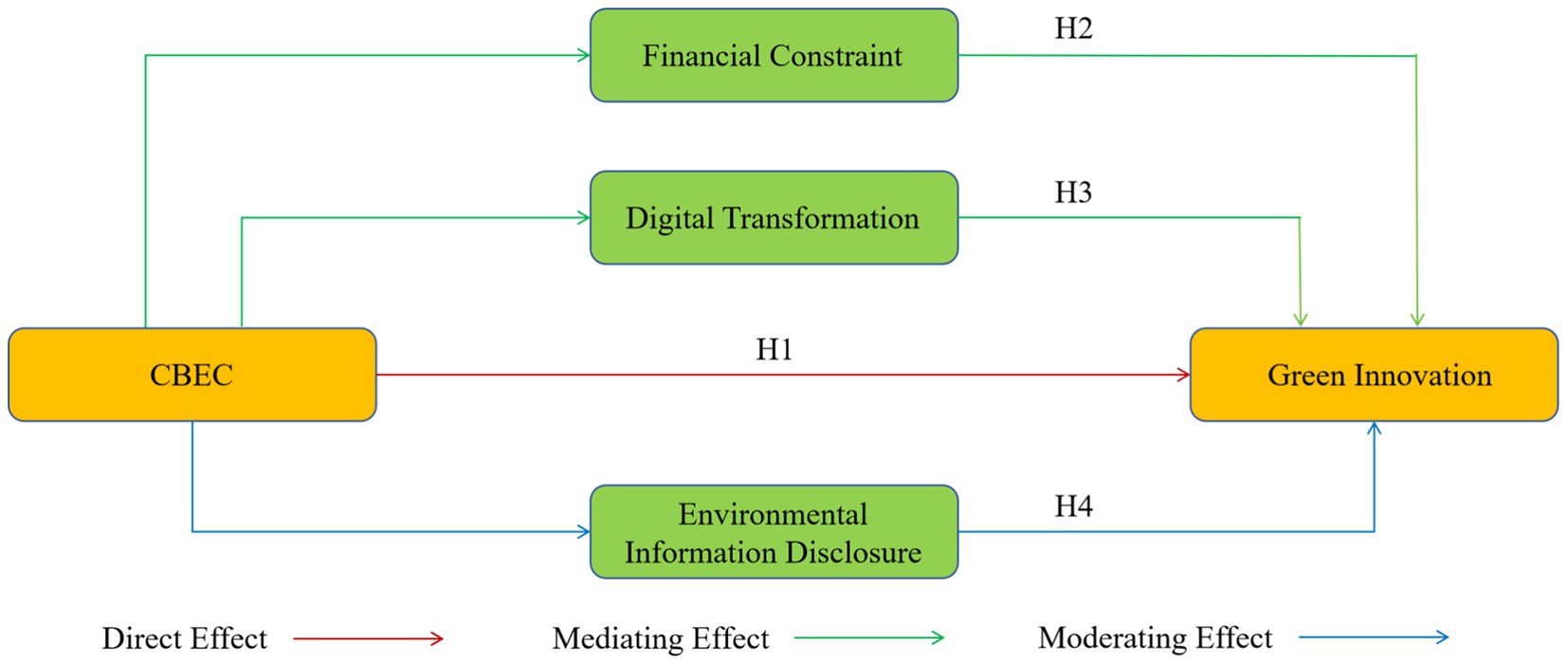

The rapid development of cross-border e-commerce has not only helped businesses expand into international markets but also facilitated technological exchanges and resource sharing among enterprises, ultimately promoting green innovation. This study is based on data from Chinese listed companies from 2013 to 2023, utilizing web scraping technology to extract corporate announcements and employing a cross-border e-commerce keyword dictionary to identify specific time points when companies engaged in cross-border e-commerce activities. These time points are treated as policy shock events, and a difference-in-differences model is employed for empirical analysis. The findings reveal that engaging in cross-border e-commerce significantly enhances a company’s level of green innovation. Mechanism analysis indicates that cross-border e-commerce indirectly promotes increases in green patent applications by alleviating firms’ financial constraint and promoting their digital transformation, while environmental information disclosure also plays a positive moderating role. Heterogeneity analysis shows that this promotional effect is more pronounced among high-tech enterprises, firms in high-pollution industries, large state-owned enterprises, and companies in China’s central and western regions. The study’s conclusions provide a reference for enterprises to achieve sustainable development through cross-border e-commerce activities.

1 Introduction

In recent years, cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) has become a vital driver of global trade’s digital transformation, directly linking producers and consumers through B2B/B2C models and digital platforms, thereby reducing transaction costs and improving supply chain efficiency (Eg and Huang, 2014). In China, the CBEC market has grown rapidly, with B2B transactions accounting for over 70% of the total, and transaction volume rising from 1.06 trillion yuan in 2018 to 2.63 trillion yuan in 2024 (Lai and Wang, 2014). This shift reflects the industry’s transition from rapid expansion to high-quality development, contributing substantially to foreign trade stability and export growth. Meanwhile, under the global push for sustainable development, corporate green innovation has become a central policy priority. The Chinese government has introduced multiple measures—such as promoting green trade and encouraging the use of recyclable, reusable, and biodegradable products—to integrate low-carbon principles into foreign trade strategies. At the same time, foreign regulatory frameworks, including the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and the New Battery Law, are imposing stricter environmental requirements on exporters, pressuring CBEC firms to reduce carbon footprints and disclose emission data. These developments highlight both opportunities and challenges for CBEC enterprises to engage in green innovation.

Cross-border e-commerce enterprises, by virtue of their global operational reach, are directly exposed to tightening environmental regulations in major economies. Mechanisms such as the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and the New Battery Law not only impose explicit costs through carbon pricing but also create implicit pressures to upgrade production processes and develop low-carbon technologies (Zeng et al., 2022). On digital platforms, ESG certification requirements and supply chain transparency standards further push firms toward greener practices by influencing visibility to consumers and market access. While these pressures can increase short-term costs—especially for small and medium-sized firms—they simultaneously open up opportunities for brand differentiation, market expansion, and integration into higher value-added global value chains through green innovation.

The platform-based nature of cross-border e-commerce amplifies these dynamics. For instance, Amazon’s “Climate Pledge Friendly” program and OTTO’s preferential exposure for certified green products provide tangible traffic and sales incentives for eco-friendly goods. Large Chinese enterprises like China Duty-Free Group have responded proactively, launching environmental campaigns, adopting biodegradable packaging, and collaborating on sustainable product development. However, resource constraints hinder many SMEs from engaging in substantial green R&D, and varying international environmental standards raise adaptation costs. These realities highlight both the potential and the uneven accessibility of green innovation within the cross-border e-commerce landscape.

The current literature directly studying the impact of cross-border e-commerce on corporate green innovation is limited. This paper primarily investigates whether cross-border e-commerce can effectively promote corporate green innovation, further explores how cross-border e-commerce provides opportunities for green innovation, and analyzes whether there are differences in the impact of cross-border e-commerce operations on green innovation levels among different types of enterprises. The potential marginal contributions of this paper are mainly reflected in the following three aspects: First, it broadens the conceptual boundaries of cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) research. It breaks through the prevailing economic-cost orientation of existing literature by incorporating the environmental-strategy dimension into the analytical framework, unveiling CBEC participation as a vital catalyst for corporate green innovation. By integrating insights from international trade theory and environmental economics, we bridge two previously distinct strands of scholarship, positioning CBEC as a digital trade platform with profound strategic environmental significance. Second, it advances the theoretical understanding of how digital trade shapes green innovation. It elucidates the micro-foundations through which CBEC engagement influences corporate environmental strategy. Specifically, we find that CBEC fosters green innovation by alleviating financial constraints (Ayyagari et al., 2011), strengthening environmental management routines (Testa and Iraldo, 2010), and accelerating digital transformation processes (Pan et al., 2021). This redefines CBEC from a mere market-access tool into a transformative mechanism for reshaping firms’ sustainability-oriented innovation pathways. Third, it reveals the heterogeneity of CBEC’s green innovation effects. Multi-level heterogeneity analysis shows that CBEC’s positive impact on green innovation is more pronounced among enterprises in high-tech and heavily polluting industries, firms located in western regions, and state-owned enterprises. These findings contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the differentiated mechanisms linking digital trade and environmental strategy under varying contextual and structural conditions. Fourth, it extends methodological approaches at the micro level. In contrast to existing research, which predominantly relies on the establishment of CBEC comprehensive pilot zones as a proxy variable (e.g., Zhang and Zhang, 2013b), we follow the approach of Yang et al. (2023) by employing web-scraping techniques and corporate disclosure text analysis to directly identify CBEC-active firms. This precise micro-level operationalization not only strengthens the credibility of causal inference but also offers a replicable methodological template for future inquiries into the firm-level impacts of digital trade on innovation behavior.

2 Literature review

2.1 Cross-border e-commerce

Eg and Huang (2014) define cross-border e-commerce as a form of international trade in which market entities in different customs territories rely on electronic trading platforms to conclude contracts, complete payment settlements, and facilitate commodity circulation through cross-border logistics systems. The business models in this field are diverse, spanning B2B, B2C, and C2C formats. From a market structure perspective, B2B transactions remain dominant in China, accounting for more than 70% of the total market share, though in recent years the B2C segment has shown rapid expansion, driving diversification within the industry.

In terms of measurement approaches, researchers generally face a key challenge: the lack of a unified and directly observable statistical indicator for cross-border e-commerce enterprises, especially given the large number of SMEs and the diversity of transaction platforms. Existing studies have addressed this issue through three main approaches. First, policy zone perspective. Many scholars (Wang and Rui, 2022; Ma and Guo, 2022; Zhang and Zhang, 2023a; Liu and Chen, 2024; Lin and Fu, 2024) take cross-border e-commerce comprehensive pilot zones as a proxy variable, investigating policy-induced differences in regional or corporate performance. Second, platform and customs data approach. Another stream of literature accesses transaction and firm-level information from specific e-commerce platforms or customs import/export records. For example, Ju et al. (2020) use DHgate data to examine how cross-border e-commerce reduces trade costs, while Liu and Gu (2022) draw on Alibaba International membership data to analyze impacts on value-chain participation. Third, web scraping & text analysis approach. A newer but less widely adopted method combines large-scale web crawling with text mining to identify cross-border e-commerce firms and their behaviors (Yang et al., 2023). This approach can cross-reference multiple platforms, corporate websites, and news sources, thereby reducing platform-specific bias and enabling dynamic, granular data collection at the enterprise level. It also allows for integration with other corporate characteristics (e.g., ownership, industry classification, innovation outputs), making it particularly suitable for micro-level impact studies.

While prior studies have made substantial contributions through pilot zone and platform-based approaches, there remains a scarcity of research leveraging high-frequency, multi-source identification methods such as web scraping and text analysis for comprehensive firm-level measurement. This methodological gap may partly explain the limited understanding of how cross-border e-commerce participation influences more nuanced corporate behaviors—such as green innovation—beyond broad trade and export effects. Compared with the policy-zone proxy approach, which has been widely used as a quasi-natural experiment for causal inference, our text-based identification method offers several advantages for this research context. First, pilot-zone assignment may not accurately capture actual CBEC participation at the firm level, especially given the heterogeneity of firms within zones and policy spillovers beyond designated regions. Second, the policy-zone approach inherently constrains the sample to specific geographic areas, limiting generalizability across non-zone firms. Third, identifying actual CBEC operators through web scraping and text mining allows for precise firm-level matching with innovation data, enabling micro-founded tests of the CBEC–green innovation link that policy-zone proxies cannot directly support. While quasi-experimental designs are valuable for estimating average policy impacts, our focus on heterogeneity and internal mechanisms requires a more granular and comprehensive measurement of CBEC engagement.

2.2 The economic effects of cross-border e-commerce

The economic implications of cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) have been a central focus of academic inquiry, given its rapid expansion and transformative impact on traditional trade patterns. Existing studies can be broadly categorized into three interrelated research streams: cost reduction effects, export and brand promotion effects, and inclusive trade effects. First, cost reduction effects. A substantial body of literature emphasizes CBEC’s ability to lower trade barriers and transaction costs. Ma et al. (2018) and Guo et al. (2018) argue that CBEC streamlines multi-tier distribution chains, significantly reducing intermediate stages and enabling broader market participation, especially by disadvantaged groups. Ju et al. (2020) further differentiate between fixed and variable costs, finding that CBEC most effectively reduces fixed costs, while its influence on variable costs is sensitive to market conditions. Second, export promotion and brand internationalization. Another research strand highlights CBEC’s role in enhancing export performance and accelerating brand globalization. Ma and Fang (2021) show that industrial policies supporting CBEC expand both the intensive (export scale) and extensive (market scope) margins, with the extensive margin responding most immediately. Wei and Xing (2019) emphasize that CBEC platforms reduce brand-building costs, thus shortening the time required for international market penetration. Yang et al. (2023) demonstrate that listed companies adopting CBEC improve internationalization through supply chain restructuring, expanded financing channels, and digital transformation. Third, inclusive trade effects. CBEC is also recognized for democratizing access to international markets. Ju et al. (2020) document its role in integrating inland provinces and high-value-added industries into global trade networks. Zhang and Pan (2021), through cross-country analysis, confirm that CBEC reduces bilateral trade costs, with more pronounced effects for developing economies.

Collectively, these research streams demonstrate CBEC’s cost efficiency, export and brand-enhancing functions, and inclusivity. However, most studies adopt macro or trade-centric perspectives, measuring outcomes in terms of cost savings, export volumes, or market access, without systematically examining how these economic effects feed into more complex forms of firm capability building, such as green innovation. Moreover, existing analyses often stop at performance outcomes without assessing the mediating mechanisms—such as changes in financing conditions, supply chain transparency, or ESG compliance requirements—that could link CBEC participation to environmental innovation.

2.3 Factors influencing green innovation

Research on the determinants of green innovation spans multiple levels, integrating external market and regulatory pressures with internal firm-level resources and strategic choices. The literature can be broadly encapsulated within three interrelated streams: policy and regulatory drivers, financial constraints and incentives, and market and consumer-driven factors. First, policy and regulatory drivers. The “Porter Hypothesis” (Porter and Linde, 1995) and its variants remain foundational in this stream. It posits that appropriately designed environmental regulations can stimulate innovation, with efficiency gains offsetting compliance costs and potentially boosting competitiveness. Guo (2019), focusing on China, finds that economic instruments—such as pollution discharge fees and increased environmental protection expenditure—are more effective than administrative penalties or local regulations in motivating corporate green innovation. Second, financial constraints and green credit policies. Financial resource availability constitutes a critical bottleneck for green innovation, given the high upfront R&D costs and uncertain returns. He et al. (2019) report that the innovation-promoting effect of green credit policies is more pronounced among firms facing tighter financing constraints. In contrast, Cao et al. (2021) argue that green credit policies can suppress GI in heavily polluting enterprises by restricting long-term financing channels. Wang and Wang (2021) further note that post—“Green Credit Guidelines,” restricted industries experienced an “increase in quantity but decline in quality” of innovation outputs, suggesting that financial policies must be complemented by capability-building measures. Third, market- and consumer-driven factors. A smaller but growing body of research highlights the role of market preferences, competitive positioning, and supply chain requirements in spurring green innovation. Internationally, demand for eco-labeled products or compliance with global buyers’ environmental standards can exert significant pressure on exporters to innovate. Such market-driven mechanisms are particularly relevant in sectors where buyers or platforms mandate ESG certifications as a condition for market access. Current literature provides rich insights into policy regulation and financial constraint channels, with emerging recognition of market-driven forces. However, there is a notable absence of research integrating these drivers within the context of digital, globally networked business models such as CBEC.

3 Hypothesis

3.1 The direct impact of cross-border e-commerce on green innovation

Cross-border e-commerce’s trading activities enable it to leverage export competition effects and export learning effects, accumulating technical capabilities for green innovation.

The export competition effect refers to enterprises enhancing their technological capabilities and product advantages through international market competition, thereby driving green innovation. When entering international markets, enterprises face competition from existing rivals and must contend with host countries’ market protection mechanisms. The changing competitive environment imposes higher demands on enterprises’ dynamic capabilities, compelling them to strengthen their core competitiveness. Green innovation is a crucial pathway for export enterprises to establish quality differentiation barriers (Cheng and Lu, 2024). Liu and Chen (2024) argue that the widespread adoption of digital technology and the emergence of cross-border e-commerce platforms have lowered market entry barriers, triggering a “catfish effect” that spurs innovation and attention to international demand. As global markets intensify competition, environmental protection and green innovation become central to competitiveness, prompting enterprises to increase green R&D investments, enhance eco-friendly product capabilities, and seek first-mover advantages.

The export learning effect involves enterprises gaining international market experience and knowledge through export activities, thereby enhancing their green innovation capabilities. Kang (2011) and Wagner (2012) both suggest that interactions with foreign consumers help enterprises better understand international demands for product quality and environmental standards, aiding in improving product design and production processes to drive green innovation. Additionally, collaborations with foreign enterprises facilitate technology spillovers, enabling enterprises to adopt advanced foreign environmental technologies, production methods, and management experiences, thereby elevating their green innovation levels. Liu and Chen (2024) propose that cross-border e-commerce promotes international green technology exchanges via digital platforms, allowing enterprises to efficiently access developed nations’ clean production technologies. Importing environmentally friendly intermediate goods enhances enterprises’ green knowledge reserves, fostering technological imitation and re-innovation. In addition, in international markets, developed countries impose stringent environmental standards on products, and the demand for green technologies among foreign consumers is continuously rising. These factors provide export-oriented enterprises with market-driven incentives to promote green innovation.

Based on the above analysis, Hypothesis 1 is proposed:

H1: The development of cross-border e-commerce has a positive impact on enterprises' green innovation levels.

3.2 The mediation effect of financial constraint

Cross-border e-commerce can also play a positive role in alleviating corporate financial constraints, thereby promoting green innovation practices. The knowledge outcomes of green innovation possess certain public goods attributes, requiring substantial financial investments from enterprises during the research, development, and implementation of green technologies. These investments may not be fully recouped through market returns in the short term. Yang and Xi (2019) point out that when enterprises face high levels of financial constraints, they tend to prioritize reducing their R&D expenditures on green innovation. Xu et al. (2021) argue that green innovation is characterized by high risk, high capital investment, and high uncertainty, making investors more sensitive to information asymmetry. Therefore, the availability of smooth internal and external financing channels can help enterprises increase their investments in green innovation and enhance their green innovation capabilities.

From the perspective of internal capital accumulation, the export scale effects brought about by cross-border e-commerce assist enterprises in improving their profitability. Krugman (1980) propose that exports can expand a company’s production scale and reduce costs through economies of scale. Palmer and Truong (2017) found that the introduction of green products is positively correlated with a company’s profitability. Kang (2011) notes that as the scale of exports increases, the per-unit transportation costs faced by enterprises decrease, motivating them to engage in green innovation. Furthermore, with the advancement of the Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese multinational corporations have expanded their production scale by investing in factories along the route. This has also facilitated further growth in export volumes through vertical linkages with their parent companies. Zhu and Sun (2020) suggest that investing in cross-border markets to expand production capacity reduces the per-unit green innovation costs of products. The resulting increases in revenue and profits provide financial security for green innovation efforts.

From the perspective of the external financing environment, the internal and external constraints of cross-border e-commerce have optimized the information disclosure mechanism, improved financing efficiency, and effectively alleviated the financing difficulties of enterprises. The digital characteristics of cross-border e-commerce can optimize the information disclosure process, significantly enhance corporate financing efficiency, and help alleviate the financing challenges and financing cost issues faced by enterprises. Ma and Guo (2022) found that the institutional innovations in the comprehensive pilot zones for cross-border e-commerce have contributed to the alleviation of corporate financing constraints, working together with the reduction of trade costs to play a moderating role and promote new export growth.

Based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis 2 is proposed:

H2: The development of cross-border e-commerce positively influences corporate green innovation by alleviating financing constraints.

3.3 The mediation effect of digital transformation

The development trend of cross-border e-commerce drives the full-chain digitization of offline transactions, payments, logistics, and other processes, inherently possessing the characteristics of digital transformation. Cross-border e-commerce enterprises apply digital technologies to promote green development practices through optimizing resource allocation, and improving governance efficiency.

From the perspective of optimizing resource allocation, digital trade strengthens the green collaborative capabilities of the cross-border e-commerce industrial chain. The introduction of digital supply chain management systems enables enterprises to quickly connect with green suppliers and partners, optimize logistics and production processes, reduce carbon footprints and resource waste, thereby constructing a more green and efficient industrial chain ecosystem. Wang and Li (2018) emphasize that technologies such as big data and artificial intelligence enhance the interconnectivity of information systems and the integration capabilities of supply chains, improving enterprises’ responsiveness to market demands and optimizing resource allocation. Cainiao has announced that it has achieved full-cycle green management from order generation to terminal delivery. In terms of order management, Cainiao has popularized the use of electronic waybills, dynamic route planning systems, and large-scale application of eco-friendly packaging materials. At the logistics infrastructure level, Cainiao has also developed innovative models such as solar-powered parks and recycling networks, creating a green solution covering warehouse management, packaging design, main road transportation, and last-mile delivery throughout the entire lifecycle.

Digital transformation of enterprises can also optimize governance levels both internally and externally, promoting green innovation by strengthening external supervision of stakeholders and alleviating internal principal-agent conflicts. Kim et al. (2017) conducted research on the European cross-border e-commerce market, finding that digital transformation enhances management transparency, compresses the space for managerial opportunism, reduces discretionary power, and lowers supervision costs. Chen and Hu (2022) proposed that digital tools can strengthen real-time monitoring of various corporate operations, enabling external stakeholders such as investors, governments, and consumers to better understand the company’s operational status, reduce information costs, and encourage enterprises to focus more on long-term sustainable development in their decision-making. Additionally, digital transformation enhances the professional allocation of authority, alleviating internal agency conflicts. Alignment of goals between management and employees reduces short-term interest pursuit by management in green innovation, thereby creating a more favorable internal and external environment for the company’s green transformation (Dai and Shen, 2024). Therefore, digital transformation not only optimizes the corporate governance structure but also effectively promotes investment and development in green innovation.

Based on the above analysis, we propose Hypothesis 3:

H3: The development of cross-border e-commerce positively influences corporate green innovation by promoting digital transformation.

3.4 The moderating effect of environmental information disclosure

The China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) and environmental regulatory authorities have gradually strengthened the environmental information disclosure requirements for listed companies through a phased and multi-tiered policy framework, aiming to mitigate environmental risks, protect investor interests, and promote green transitions. Since 1997, the CSRC has issued a series of documents requiring listed companies to disclose environmental risks and the compliance of investment projects in their prospectuses and periodic reports. In 2017, it explicitly mandated key polluting entities to disclose their emissions information, while other enterprises were required to follow the “disclose or explain” principle. Exchanges and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment have also coordinated their regulatory efforts. For instance, in 2008, the Shanghai Stock Exchange mandated the immediate disclosure of six categories of major environmental incidents, and in 2021, the “Reform Plan for the Legal Disclosure of Environmental Information” systematically established a mandatory disclosure framework encompassing four pillars: unified standards, interdepartmental collaboration, oversight and accountability, and legal safeguards. Overall, the policy framework has evolved from soft to hard constraints, combining industry-specific mandatory disclosures with “disclose or explain” mechanisms to drive companies from vague statements toward data-driven and transparent environmental information disclosure, thereby serving environmental governance and the “dual carbon” goals.

In the context of tightening environmental regulation and deepening green development concepts, the synergistic effects of corporate environmental information disclosure and green innovation have garnered significant attention. Environmental information disclosure facilitates green innovation through dual channels: exerting external pressures and promoting resource allocation (Zhang and Dong, 2023). Specifically, in terms of external pressure effects, Wang and Ning (2020) found that when companies face dual compliance requirements from policymakers and public opinion, they tend to proactively optimize their internal environmental management systems through green innovation to enhance their market image. Zhang et al. (2021) further noted that companies facing negative environmental coverage significantly increase their technological innovation investments, with this “pressure-driven” mechanism prompting a shift from passive rectification to proactive upgrading. The quality of internal corporate controls plays a crucial moderating role in this process, as proactive environmental management reduces the pressure from media scrutiny.

In terms of external resource effects, Xu et al. (2021) found that high-quality environmental information disclosure can convey signals to capital markets that a company’s environmental risks are controllable, reducing investors’ concerns about penalty and litigation risks and gaining more external support. Zhao (2012) studied Chinese and Russian enterprises and found that companies actively disclosing ESG information and actively participating in public welfare activities can attract government attention, making it easier to obtain tax incentives and relevant policy support.

Cross-border e-commerce platforms build a new institutional environment through green admission standards. To maintain their platform operating rights, enterprises must continuously improve their environmental performance, forming a positive cycle from compliance to proactive innovation. Moreover, the platform’s environmental standards are not static but dynamically upgraded in response to international policies (e.g., the EU’s new battery law) and consumer preferences. From the perspective of institutional theory, this digital regulatory pressure has unique advantages. Compared to traditional government regulation, it is more immediate; when a company’s product violates regulations, the platform typically removes the non-compliant product within 24 h. This efficient supervision mechanism forces companies to increase their green innovation investment intensity, thereby enhancing their green innovation levels.

Based on the above analysis, Hypothesis 4 is proposed:

H4: Corporate environmental information disclosure positively moderates the direct relationship between cross-border e-commerce operations and corporate green innovation levels, such that the positive impact of CBEC on green innovation is stronger for firms with higher-quality environmental disclosure.

The theoretical derivation and hypothetical relationships of this research are summarized in Figure 1.

4 Research design

4.1 Sample selection and data sources

This study selects Chinese A-share listed companies from 2013 to 2023 as research samples. 2013 is regarded as the starting year of cross-border e-commerce (Wang and Rui, 2022), during which relevant policies were intensively introduced. Traditional manufacturing enterprises, trading companies, and China’s brand companies actively laid out digital trade, driving the rapid development of cross-border e-commerce. Therefore, 2013 was chosen as the starting year. According to data from the Ministry of Commerce, China’s cross-border e-commerce transaction volume grew from 3.1 trillion yuan in 2013 to 16.85 trillion yuan by 2023, accounting for 40.35% of the total value of goods trade imports and exports nationwide. This signifies that cross-border e-commerce has become a crucial growth driver for China’s foreign trade.

The listed company data was screened based on the following criteria. Companies marked as ST or ST* were excluded, as ST companies face financial irregularities or delisting risks, and their operational behaviors may systematically differ from those of normal companies. Removing such observations during the study period helps avoid outliers. Financial sector companies were also excluded, as their financial statement structures, regulatory policies, and characteristics of innovative activities significantly differ from non-financial enterprises. Therefore, companies were excluded based on the CSRC industry classification standards (2012 edition). Only companies that remained in continuous operation from 2013 to 2023 were retained to ensure temporal continuity. After applying these criteria, the final dataset included 1,851 listed companies with 19,905 observations, covering major sectors of the real economy such as manufacturing, information technology, and energy.

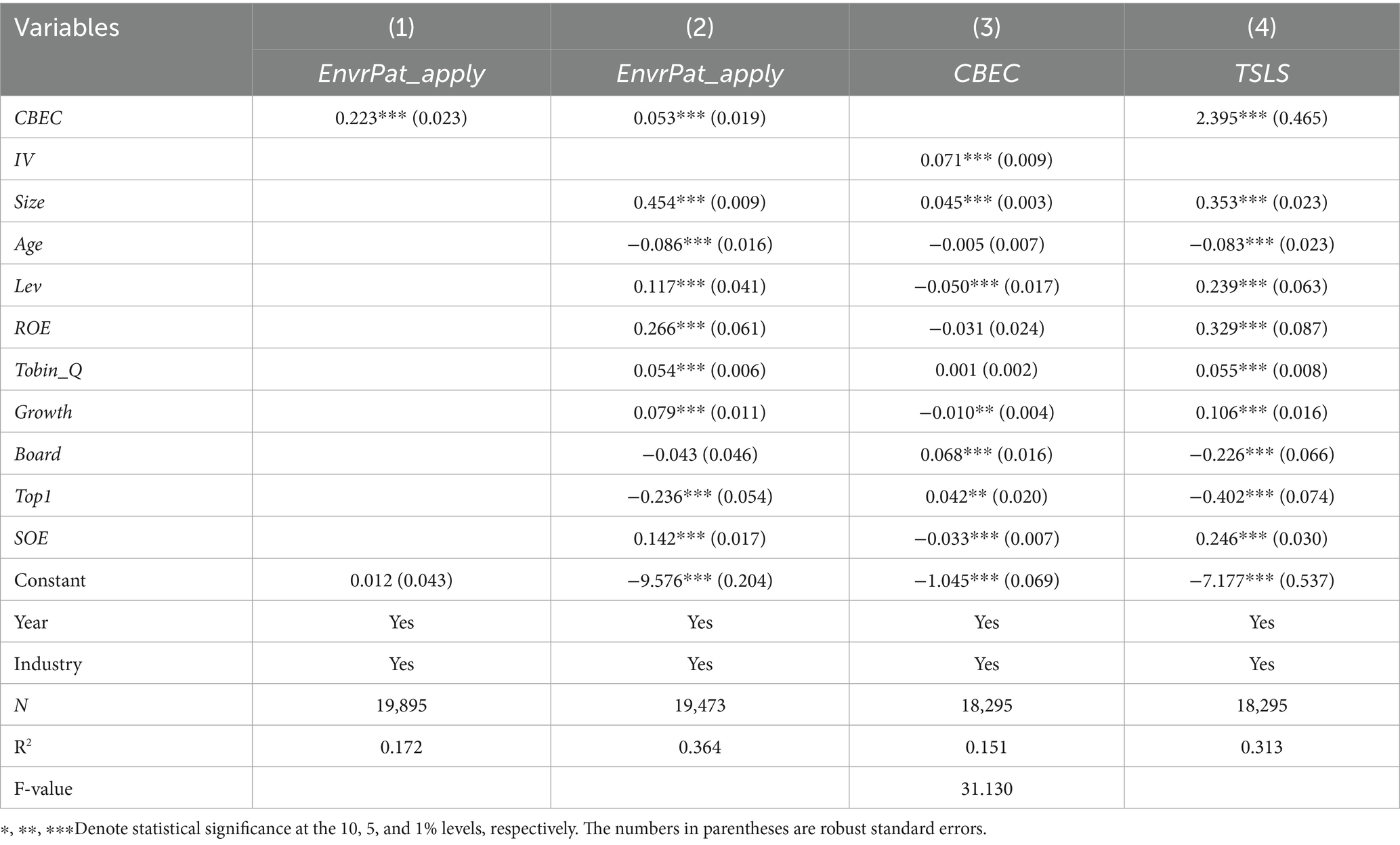

4.2 Variable definition

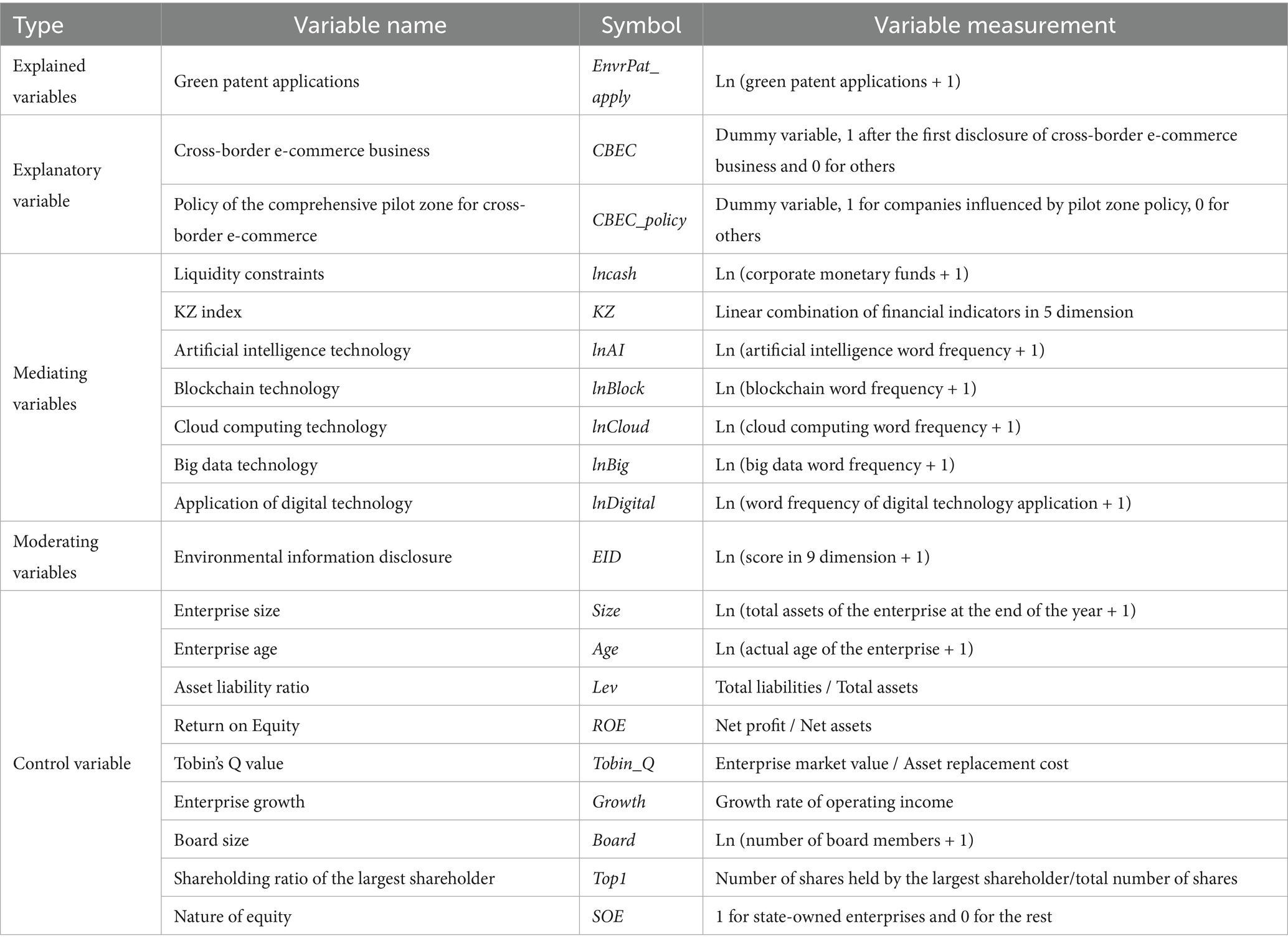

Table 1 shows the definition of variables in this article.

4.2.1 Dependent variable: green patent

In measuring the level of green innovation for enterprises, existing studies generally use the number of green patents as an indicator. The construction method of the dependent variable index in this study draws on the research results of Xu and Cui (2020), employing the annual green patent applications (EnvrPat_apply) of enterprises to represent their level of green innovation. The choice of the current year’s green patent applications as the core dependent variable is based on the following rationales. First, the number of patent applications can more promptly and stably reflect the dynamics of innovation. As pointed out by Li and Zheng (2016), patent technologies may influence corporate performance even during the application process. Second, since patents typically require a 1–2 year review period from application to authorization, authorized data exhibits significant lag, potentially failing to capture the immediate effects of policy or market incentives. However, patent applications are usually submitted during the R&D phase, and the technology is already application-ready at the time of application, thereby offering a more real-time reflection of corporate innovation investments.

Green patent identification is based on the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) green patent classification list, which categorizes green patents into seven primary classifications according to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Patent data for listed companies is sourced from the National Intellectual Property Administration’s patent database, precisely matched by company name. By screening green innovations through the International Patent Classification (IPC codes), this study uses the green patent applications for enterprises. To eliminate the effects of scale and zero values, the number of green patent applications are each incremented by one before taking the logarithm for processing.

4.2.2 Independent variable: cross-border e-commerce

Previous research on cross-border e-commerce has primarily focused on cross-border e-commerce comprehensive pilot zones as an entry point. However, this approach has limitations since not all enterprises within these zones engage in cross-border e-commerce activities. This study draws on Yang et al. (2023), conducting text analysis of listed company announcements and matching them with a cross-border e-commerce dictionary to identify relevant enterprises. This method offers a finer granularity and greater targeting in the research.

First, a cross-border e-commerce dictionary is constructed, categorized into four sections based on the business processes: an overview of cross-border e-commerce, cross-border e-commerce platforms, logistics and payments, and policies. To determine specific terms within the dictionary, this study references classic literature, authoritative textbooks, significant policy documents, the annual reports on China’s e-commerce released by the Ministry of Commerce, and the annual reports of listed companies explicitly engaged in cross-border e-commerce. Ultimately, a dictionary containing 263 keywords is developed, accurately reflecting the cross-border e-commerce development levels of different enterprises. This research selects Chinese A-share listed companies from 2013 to 2023 as the sample, crawling their announcements and conducting text analysis. By matching the dictionary with the announcements, a word frequency statistical indicator for cross-border e-commerce activities of listed companies is obtained. Based on the word frequency results, a dummy variable (CBEC) is calculated. The variable is set to 1 for the year a company first discloses cross-border e-commerce-related business in its announcements and subsequent years, with 0 for other years.

In robustness tests, this study uses the cross-border e-commerce comprehensive pilot zone policy as a quasi-natural experiment to examine its promotional effect on green innovation in enterprises. The year a company’s location is designated as a cross-border e-commerce comprehensive pilot zone is considered the policy year. The cross-border e-commerce comprehensive pilot zone policy variable (CBEC_policy) is set to 1 for the policy year and subsequent years, with 0 for other years.

4.2.3 Mediating variables: financial constraint and digital transformation

To examine the financing constraint mechanism, this study references the methods of Liu and Chen (2024) as well as Si et al. (2024), employing corporate monetary funds and the KZ index to measure the degree of financing constraints for enterprises, thereby investigating the impact of cross-border e-commerce on enterprises’ financing constraints. The KZ index is sourced from CSMAR and was proposed by Kaplan and Zingales (1997) to measure the degree of financing constraints for enterprises. This index comprehensively reflects multiple financial indicators, including cash flow, dividend payments, cash holdings, debt ratio, and Tobin’s Q value, to determine the extent of financing constraints faced by enterprises. Specifically, a higher KZ index indicates greater financing constraints for the enterprise.

To examine the mechanisms of digital transformation, this study draws on the research of Wu et al. (2021) and evaluates enterprise digitalization levels from five dimensions: artificial intelligence technology, big data technology, cloud computing technology, blockchain technology, and the application of digital technology. The relevant data are sourced from the Digital Transformation Database of CSMAR, which measures corporate digitalization levels by statistically analyzing 76 digital-related word frequencies in listed company announcements. After logarithmic transformation of the obtained word frequency data, five digital transformation indicators were derived as variables for mechanism testing: lnAI, lnBlock, lnCloud, lnBig, and lnDigital.

4.2.4 Moderating variable: environmental disclosure

The moderating variable is the degree of corporate environmental information disclosure. The study draws on the approaches of Xu et al. (2021) as well as Zhang and Dong (2023), constructing an index from nine dimensions: whether the company has obtained ISO14001 certification, whether it has obtained ISO9001 certification, whether it discloses environmental protection objectives, whether it has an environmental protection management system, whether it conducts environmental protection education and training, whether it carries out environmental protection special actions, whether it has an emergency mechanism for environmental incidents, whether it has environmental protection honors or rewards, and whether it has the “three simultaneous” system. The data are sourced from the CSMAR database, specifically the tables on environmental regulation and certification disclosure of listed companies and environmental management disclosure of listed companies. The nine-dimensional indicators are summed to obtain a composite score, which is then log-transformed to measure the level of corporate green information disclosure (EID). These indicators cover core aspects such as institutional certification, conceptual objectives, management systems, implementation of actions, risk management, compliance, and honors, comprehensively reflecting the situation of corporate environmental information disclosure.

4.2.5 Control variables

The control variables’ foundational data are sourced from the CSMAR database, encompassing key corporate-level variables such as firm characteristics, financial metrics, and governance structure. Firm characteristics include firm size (Size), firm age (Age), which reflect the firm’s market position and maturity, significantly influencing green innovation decisions. Financial metrics include debt-to-equity ratio (Lev), return on equity (ROE), Tobin’s Q (Tobin_Q), and revenue growth rate (Growth), indicating the firm’s profitability and risk levels. Governance structure includes variables such as board size (Board), the top shareholder’s holding ratio (Top1) and state-owned enterprise status (SOE), with different stakeholders’ interests exerting substantial influence on corporate behavior.

4.3 Model setting

We build on the two-way fixed effects regression approach used by Qing et al. (2024) as well as Yang et al. (2023) and Lin and Fu (2024) to investigate whether conducting cross-border e-commerce business can enhance the green innovation level of enterprises, as shown in Equation 1. Chaisemartin and Haultfoeuille (2020) and Imai and Kim (2021) found that the fixed effects model is a superior estimator in terms of consistency and efficiency in measurement. This is because it effectively deals with issues such as omitted variable difficulties and unobserved heterogeneity.

where EnvrPat_applyi,t represents the dependent variable, which is the logarithm of the total number of green patent applications by a firm. The subscripts i and t represent the individual and year, respectively. CBECi,t is a treatment period dummy variable, where the year a company first discloses cross-border e-commerce related businesses in its announcement and subsequent years are coded as 1, and others as 0. Controlsi,t represents a series of control variables that affect the green patent applications of firm i in year t, this paper refers to the research methods of Jiang (2022), including the shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder, ownership nature, debt-to-asset ratio, return on net assets, Tobin’s Q value, revenue growth rate, firm age, number of board members, and firm size. Yeart represents time fixed effects, Industryk represents industry fixed effects, and εi,t represents the random error term.

The choice of control variables is reflected in the relevant research (Cai et al., 2021; Qu et al., 2022), as follows: (1) Enterprise size (Size): The natural logarithm of one plus the total assets amount of the enterprise was used to represent the enterprise size (Chen et al., 2021). When the enterprise is large, the asset size is large, and the financing constraint is small. Moreover, large-scale enterprises choose to participate more in innovation activities (Lv et al., 2021); (2) enterprise age (age): enterprise age is the natural logarithm of the company’s years since its establishment; (3) asset-liability ratio (lev): asset-liability ratio is measured by the ratio of total liability to total assets. Moderate debt management allows firms to have more capital for R&D innovation; (4) return on net assets (ROE): return on net assets represents the profitability of enterprises. The company with higher profitability has stronger innovation willingness and innovation ability (Huang et al., 2021); (5) Tobin_Q: Tobin’s Q encourages innovation by motivating firms to invest in new projects that boost their market value when it exceeds the cost of replacing assets; (6) enterprise growth (growth): enterprise growth (Growth) is the rate of operating revenue; (7) board size (board): board size is the natural logarithm of board members; (8) ownership concentration (first): ownership concentration is the proportion of the largest shareholder; (9) SOE: ownership structure influences innovation by shaping the incentives and resources available for managers and owners to pursue long-term, risky projects.

5 Empirical analysis results

5.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics of the main variables. The dependent variable, total green patent applications, shows a significant right-skewed distribution with substantial differences among firms. The top 25% of firms account for more applications than the bottom 75%, indicating that a few firms dominate innovation output while most have low participation. The treatment period dummy variable (CBEC) has a mean of 0.184, indicating that approximately 18.4% of the observations are in the post-policy implementation period. From the results of the control variables, the descriptive statistics of firm basic characteristics, firm financial indicators, and corporate governance structure are all within a reasonable range.

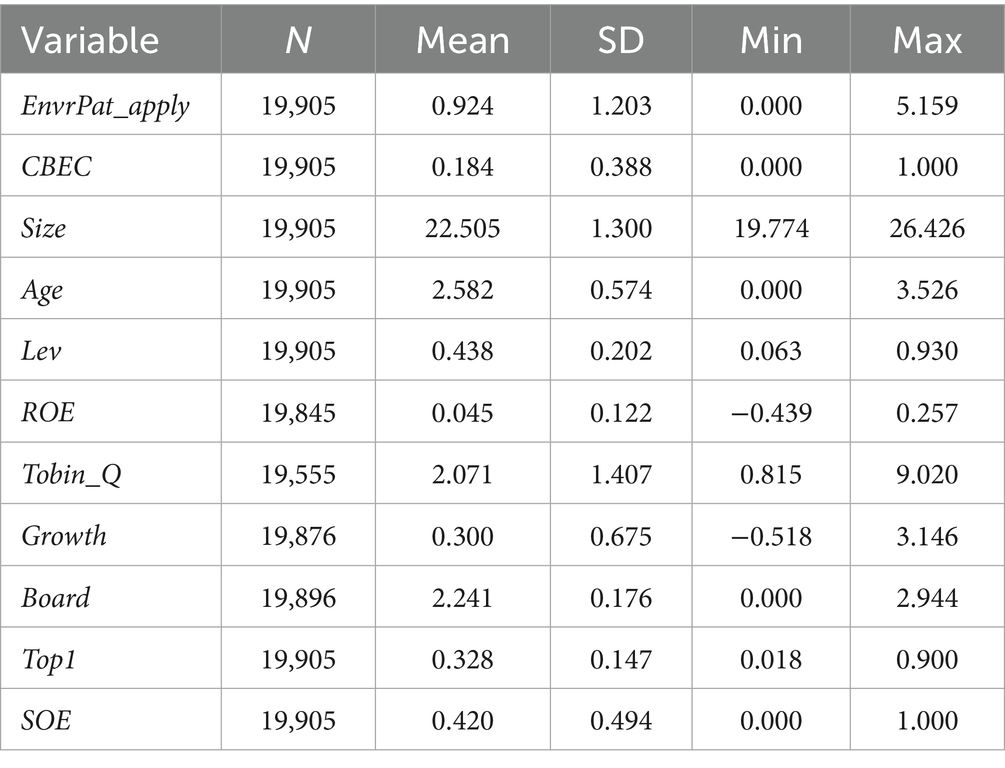

5.2 Benchmark regressions

Table 3 presents the benchmark regression results for the impact of cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) on enterprises’ green innovation, with the dependent variable being the number of green patent applications. The benchmark regression controls for time and industry fixed effects. Column (1) shows the regression results without additional control variables, while Column (2) includes control variables such as corporate governance and financial characteristics. Without control variables, the coefficient of CBEC for total green patent applications is 0.223, significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that the development of cross-border e-commerce has a significant positive impact on green innovation of enterprises. When control variables such as corporate governance and financial characteristics are introduced, the estimated coefficient of CBEC decreases to 0.053 but remains significant at the 1% level, demonstrating the robustness of the positive effect of cross-border e-commerce on green innovation.

To address potential endogeneity issues and enhance the reliability of the estimation results, this study employs the instrumental variables (IV) approach. Following the methodology of Huang et al. (2019), the number of post offices per million people in each city in 1984 is selected as the core instrumental variable. In constructing the dynamic panel model, the lagged number of city internet access users is interacted with the 1984 postal service density index. On one hand, the instrumental variable is relevant, as the development of cross-border e-commerce relies on the support of new infrastructure, and the historical accumulation of postal and telecommunications infrastructure affects the deployment efficiency of subsequent digital communication networks, satisfying the endogeneity relationship between the instrumental variable and the explanatory variable. On the other hand, the level of postal and telecommunications development is primarily influenced by strategic planning and does not have a direct association with current micro-level enterprise innovative behaviors, fulfilling the exclusion restriction requirement.

The instrumental variables test shows that in the first-stage regression, the instrumental variable has a significant positive effect on CBEC, with a coefficient of 0.071, meeting the relevance requirement of the instrumental variable. The first-stage F-value is 31.130, and the CD-Wald F-statistic is 57.915, ruling out the issue of weak instrumental variables. The KP-LM statistic is 56.741, rejecting the null hypothesis of “instrumental variables are not identified,” indicating sufficient correlation between the instrumental variables and the endogenous variables. Since there is only one instrumental variable, there is no need to conduct over-identifying test. The second-stage estimation reveals that, after controlling for endogeneity, cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) has a significant positive causal effect on the number of green patent applications of enterprises, with the effect intensity being stronger than in the benchmark regression model, possibly reflecting a more accurate capture of the local average treatment effect after improvements in instrumental variable design.

5.3 Parallel trends

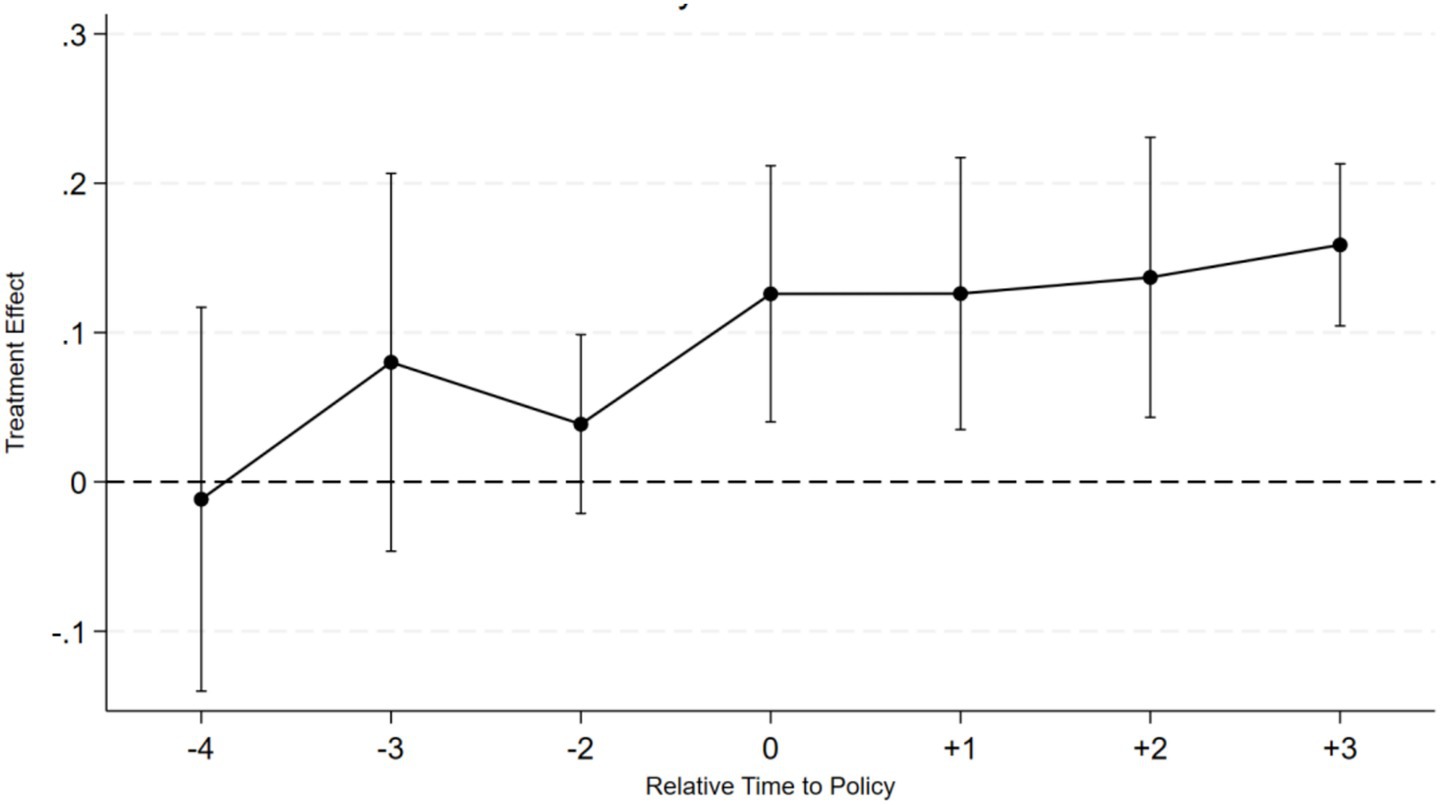

Parallel trend test is a core assumption of the Difference-in-Differences (DID) model, used to verify whether the trends of the treatment group and control group are consistent before policy intervention. If there is no significant difference in the trends before intervention, the estimated policy effect by DID is credible. This paper uses Equation 2 to conduct a parallel trend test in the four periods before and three periods after the cross-border e-commerce business, selecting the period before policy implementation as the reference group to verify whether there is a significant difference in the trends before intervention. Companies that disclosed cross-border e-commerce related announcements during the sample period are defined as the treatment group (Treat = 1), while companies that did not disclose such information are set as the control group (Treat = 0). Taking the time point when a company first publicly discloses cross-border e-commerce related information as the reference point t, a time window of [−4, +3] is constructed. To avoid potential multicollinearity issues, the period before policy implementation is used as the reference group. The periods from t-4 to t-2 are the observation periods before policy implementation, t is the policy impact point, and t + 1 to t + 3 are the effect periods after policy implementation.

Regression results show that, in the four years prior to enterprises engaging in cross-border e-commerce business, the difference in the total number of green patent applications between the treatment group and the control group did not pass the significance test, indicating that the innovation activity trends of the treatment group and control group were basically consistent before policy intervention, satisfying the parallel trend assumption of the difference-in-differences (DID) method. A positive impact was generated in the early stages of business operations, followed by a continuous expansion of the effects, suggesting that policy benefits were gradually released, and enterprises began to increase their innovation investments or technology absorption. The results in Figure 2 also indicate that the parallel trend test passed, supporting the validity of the DID model.

5.4 Robustness tests

5.4.1 Propensity score matching (PSM)-DID

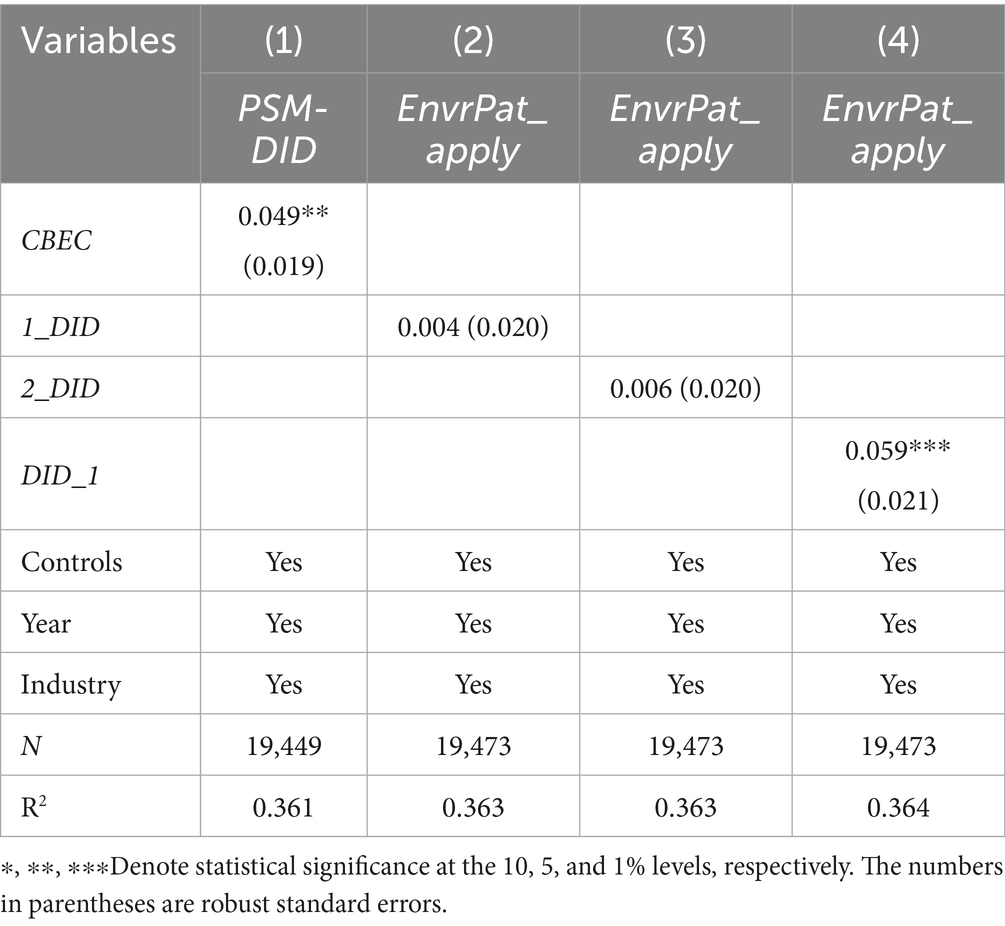

Propensity Score Matching (PSM) aims to address estimation bias caused by sample self-selection in research. By eliminating observable variable differences between the treatment and control groups through PSM and then isolating the net effect of policy intervention using the Difference-in-Differences (DID) method, endogeneity issues can be resolved. In this study, the PSM-DID approach is employed, where control variables are treated as covariates. A Logit model is used to calculate the probability of sample entry into the treatment group, and a kernel matching method is applied to match each treatment group individual with a control group individual with a similar propensity score. After matching, a new DID analysis is conducted on the matched samples. At this stage, the pre-policy implementation characteristics of the treatment and control groups are largely consistent, resulting in a purer estimated effect that may be closer to the true value. As shown in Table 4 column (1), the CBEC coefficient is 0.049 and is significant at the 5% level, indicating that the policy has a significant promoting effect on green innovation. This suggests that, even after controlling for sample selection bias, the development of cross-border e-commerce by enterprises still has a significant positive impact on patent applications.

5.4.2 Placebo test

To validate the reliability of the benchmark regression results, this study employs a counterfactual estimation approach for placebo testing. Following Shi et al. (2018), pseudo-policy implementation nodes are constructed to conduct the placebo test. When the policy implementation time is advanced, if the estimated coefficients are not significant, it indicates that the original policy identification results are exclusive; when the policy implementation nodes are delayed, the estimated coefficient values remain significant, and their absolute values show an increasing trend, reflecting the dynamic persistence characteristics of policy impacts.

This study assumes policy timing advanced by 1 and 2 periods, and lagged by 1 period for estimation, obtaining the placebo test results. As shown in Table 4 columns (2)–(3), the estimated coefficients for the fictional advanced policy timing are all insignificant, indicating that changes in green patent applications are only related to the actual policy timing, excluding the possibility that policy effects are driven by other time trends or random factors, thereby inversely verifying the authenticity of the policy effects in the benchmark regression. Table 4 column (4) shows that the regression coefficient for policy timing lagged by 1 period is 0.059, which is similar in effect strength and direction to the benchmark model, suggesting that policy effects may have persistence or lagged cumulative effects. The counterfactual test results are consistent with theoretical expectations, indicating that the DID design in the benchmark regression is reliable, and the policy effects are not spurious. Based on the above test results, this study believes that the likelihood of the benchmark model estimation results being influenced by unobserved factors is low, and the core conclusions have strong robustness.

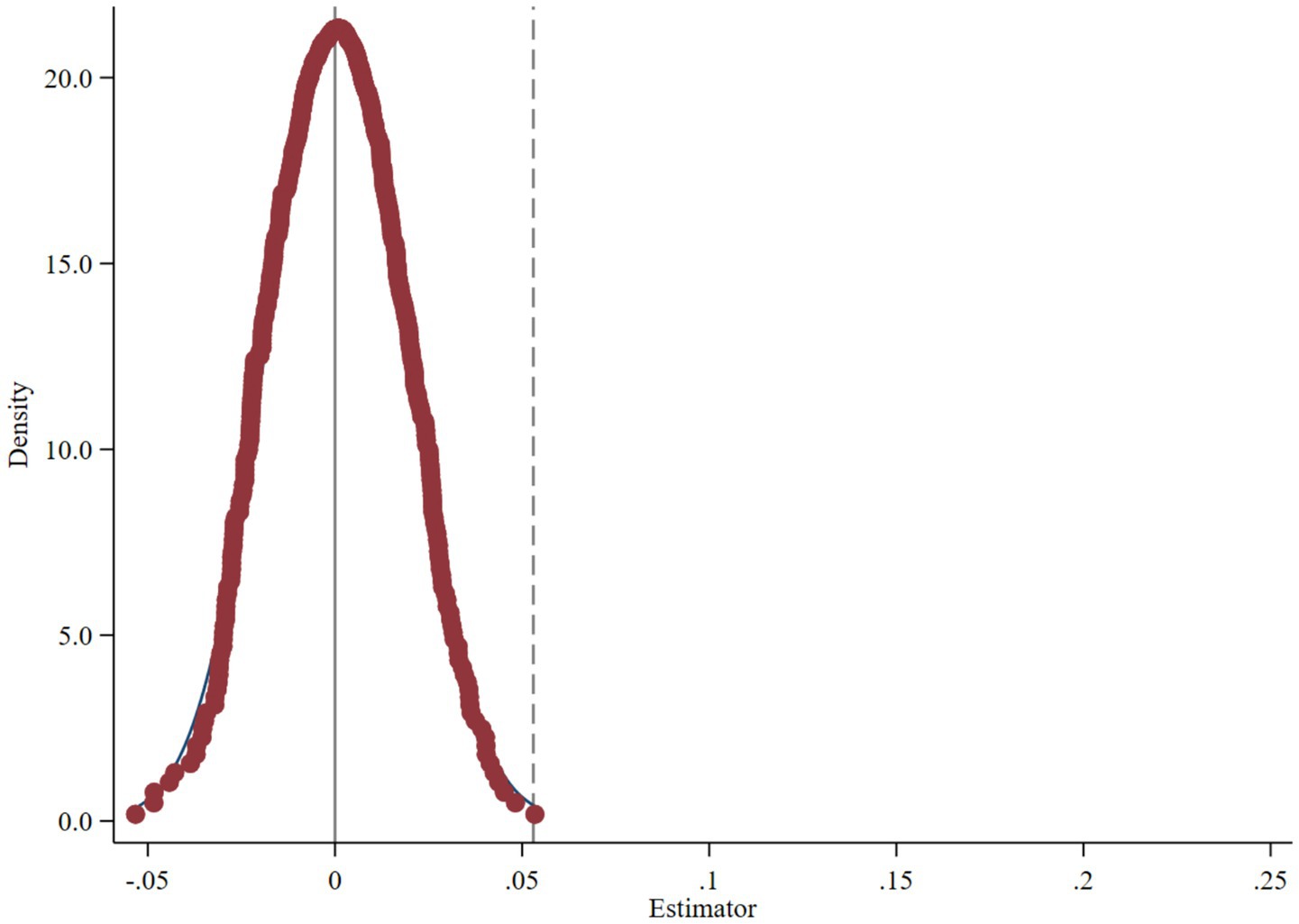

To eliminate the influence of randomness, this paper employs a placebo test method, randomly assigning enterprises to the treatment group and repeating the process 500 times to examine whether the coefficient of the “pseudo-policy dummy variable” is statistically significant. Figure 3 reports the distribution of the estimated coefficients and their corresponding p-values generated from the 500 randomization tests. The results show that the mean core regression coefficient obtained from the random tests is close to zero, with the vast majority of p-values exceeding 0.1. Furthermore, the position of the vertical dashed line in the figure (the regression coefficient of 0.053 from column (2) in Table 3) is clearly an outlier in this distribution. This indicates that factors other than cross-border e-commerce cannot drive the improvement of corporate green innovation levels.

5.4.3 Replace the explanatory variable

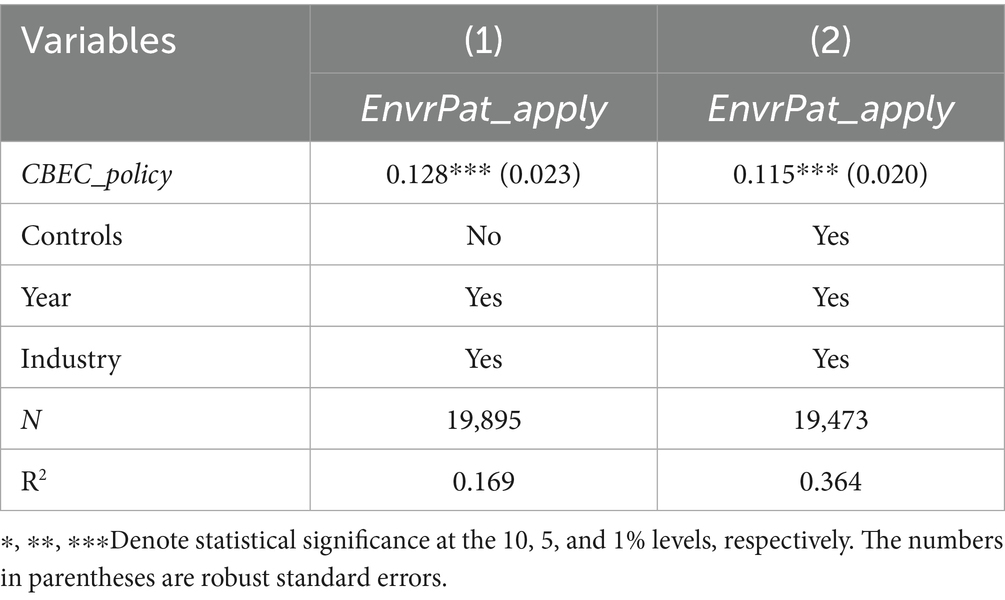

To further examine the impact of cross-border e-commerce operations on a company’s level of green innovation, this study references the methods of Lin and Fu (2024) as well as Liu and Chen (2024). It uses the policy of cross-border e-commerce comprehensive pilot zones as a quasi-natural experiment to investigate the promotional effect of cross-border e-commerce on green innovation in enterprises. Since the launch of the pilot program for China’s cross-border e-commerce comprehensive pilot zones in 2015, the scope of these zones has been gradually expanded. To date, seven batches of comprehensive pilot zones have been approved, with a total of 165 zones established. As a institutional innovation platform for the development of national digital trade, the pilot zones have achieved initial results in policy breakthroughs, optimization of the business environment, construction of cross-border logistics systems, and facilitation of payment settlements. Based on this institutional context, this study employs a multi-period difference-in-differences model to evaluate the impact of the cross-border e-commerce comprehensive pilot zone policy on green innovation in enterprises.

The empirical results show that in Table 5 column (1), when only the policy variable is included, the coefficient is 0.128, which is significant at the 1% level, indicating that the cross-border e-commerce comprehensive pilot zone policy significantly increases the number of green patent applications by enterprises. In Table 5 column (2), after adding control variables, the coefficient decreases to 0.115 but remains highly significant.

5.5 Mechanism analysis

In the theoretical analysis section above, we proposed that cross-border e-commerce promotes enterprise green innovation by alleviating corporate financial constraints and facilitating corporate digital transformation, while being moderated by corporate environmental information disclosure. Following Jiang’s (2022) approach, to validate hypotheses H2, H3, and H4, this study constructs the following model to conduct mechanism testing:

5.5.1 Financial constraint

Cross-border e-commerce optimizes corporate financing constraints through multiple approaches. On one hand, enterprises expand their international market share, enhancing profitability; shorten the collection period, reduce inventory costs, and optimize cash flow management. On the other hand, engaging in international business subjects enterprises to domestic and international regulations as well as platform oversight, necessitating mandatory disclosure mechanisms and standardized financial management systems. This regulated operation improves information quality, enabling enterprises to overcome limitations of traditional financing channels and alleviate financing constraints. This paper references methods from Liu and Chen (2024) and Si et al. (2024), using corporate monetary funds and the KZ index to measure financing constraint levels, to examine the impact of cross-border e-commerce on corporate financing constraints.

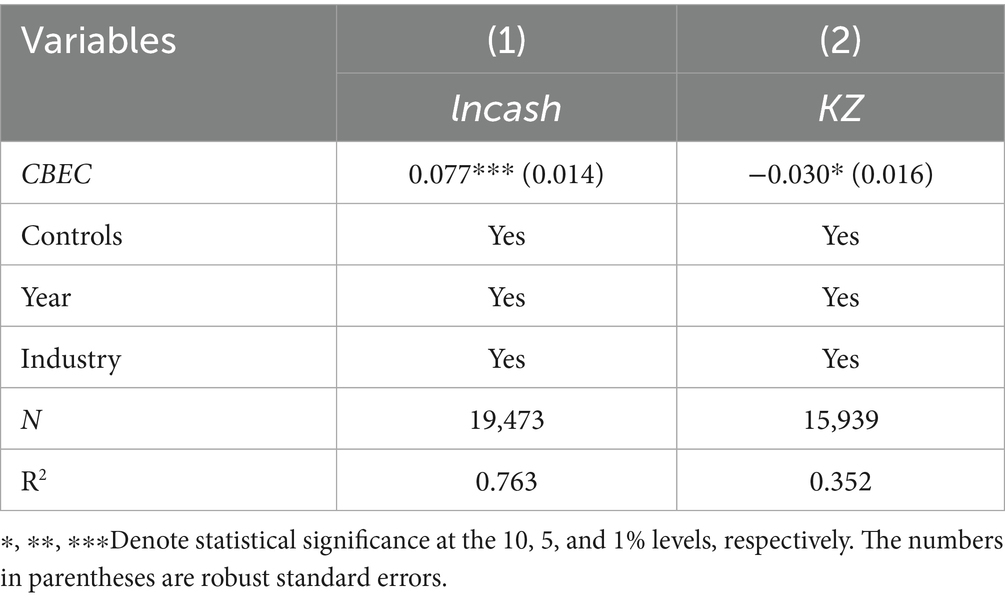

First, based on Equation 3, we test the role of cross-border e-commerce in increasing corporate liquidity and alleviating financing constraints. Table 6 column (1) shows that in the cash holding model, the coefficient for cross-border e-commerce is 0.077, indicating that enterprises participating in cross-border e-commerce can significantly increase their internal cash reserves. Cross-border e-commerce expands market boundaries, optimizes collections, and actively manages supply chains, enhancing profitability and credit ratings, thereby strengthening equity financing capabilities and internal cash reserves. In the KZ index model, Table 6 column (2) shows that the coefficient for cross-border e-commerce is −0.030, significant at the 10% level, indicating a significant reduction in financing constraints. The KZ index is positively correlated with financing constraints; a higher value implies stronger constraints. The negative relationship suggests that cross-border e-commerce significantly alleviates financing constraints, primarily through enhanced information transparency. The traceability of transaction data on digital trade platforms significantly reduces adverse selection risks, enabling financial institutions to more accurately assess repayment capabilities and reduce credit rationing.

Financing constraints are a key factor influencing green innovation. When enterprises face financing constraints, their ability to obtain funds is limited, hindering green technology R&D and innovation activities, thereby suppressing green innovation investment and development. Green innovation, characterized by high investment, long cycles, and high risks, requires stable, long-term financial support to cover costs. Yang and Xi (2019) noted that when enterprises face high financing constraints, they prioritize reducing R&D expenditures on green innovation. Thus, when enterprises secure “patient capital” through internal cash flows or equity financing, management can overcome short-term investment myopia and allocate funds to green innovation projects with long technological lock-in periods but strategic option value. Additionally, the emergence of green financial instruments reduces external financing costs. Green bonds and other financial products offer interest rate discounts and term matching, providing a more secure financing environment and incentivizing green innovation activities.

5.5.2 Digital transformation

This article focuses on the perspective of digital transformation, exploring how enterprises participating in cross-border e-commerce can drive green innovation through digital transformation. First, the rapid development of cross-border e-commerce is inseparable from the widespread application of information technology, as cross-border e-commerce itself is a new form of trade driven by information technology. Second, the introduction of digital technology not only significantly improves enterprise operational efficiency but also gives rise to new business model innovations. Specifically, cross-border e-commerce enterprises enhance user experience through digital means, achieve more precise marketing and personalized services, and expand customer coverage to a broader scope. At the same time, digital transformation enables enterprises to better address the challenges of global competition. In cross-border logistics, enterprises use digital technology for intelligent route planning to improve logistics efficiency.

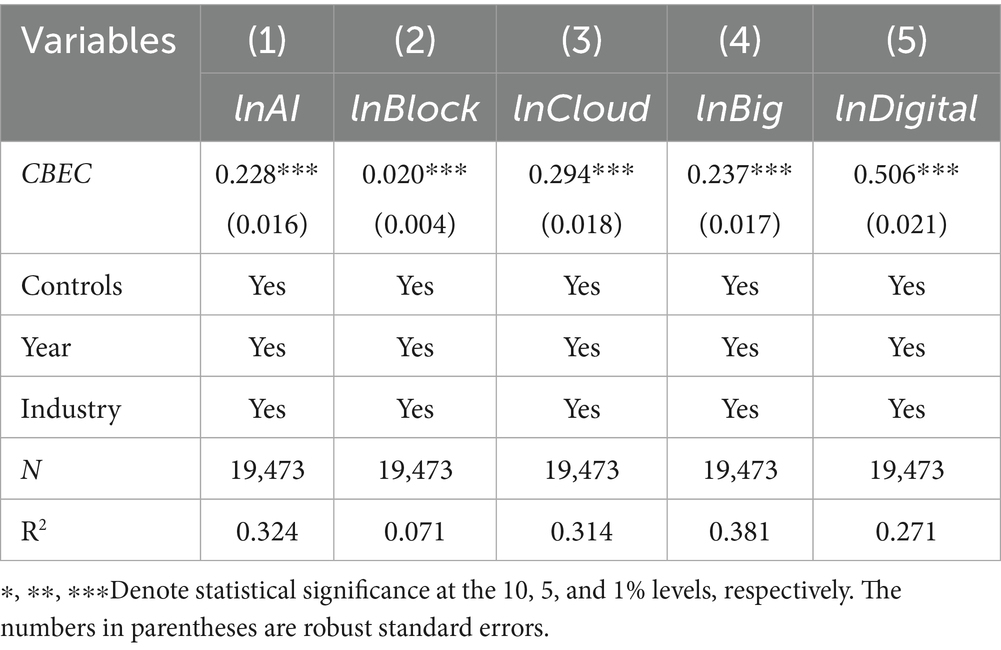

According to Equation 3, the role of cross-border e-commerce operations in promoting enterprise digital transformation is tested. Table 7 shows that the coefficients of cross-border e-commerce are significantly positive at the 1% significance level in all five models. The coefficients for artificial intelligence, blockchain, cloud computing, big data, and digital technology applications are 0.228, 0.020, 0.294, 0.237, and 0.506, respectively. This indicates that enterprise participation in cross-border e-commerce can systematically drive multi-dimensional digital transformation.

With the continuous enhancement of environmental awareness, an increasing number of cross-border e-commerce enterprises are integrating green development concepts into their business models and promoting sustainable development through digital technology. Rong et al. (2025) found that enterprise digital transformation can significantly suppress greenwashing and promote genuine green innovation. The application of digital technology allows enterprises to more precisely monitor environmental impacts in supply chain processes. Cao et al. (2023) focused on the manufacturing sector, revealing the co-evolutionary patterns between digital transformation and green transformation. Enterprise digitalization drives green innovation from equipment upgrades to process optimization and comprehensive emission reductions across the entire supply chain. The application of digital technology enables real-time monitoring of energy consumption and carbon emissions during logistics processes, allowing enterprises to optimize logistics routes and reduce negative environmental impacts. Additionally, digital platforms effectively disseminate green environmental protection concepts, encouraging consumers to choose green products. By showcasing the environmental attributes of products and the recyclability of packaging materials on e-commerce platforms, enterprises not only enhance green consumption awareness but also promote actual participation in green consumption.

5.5.3 Environmental information disclosure

This paper examines the moderating effect of environmental information disclosure on the process of cross-border e-commerce operations influencing corporate green innovation. Drawing on the approaches of Xu et al. (2021) as well as Zhang and Dong (2023), we construct an index using nine dimensions, including whether the company has obtained environmental certifications, whether it discloses environmental goals, and whether it has an environmental management system, among others. The comprehensive score obtained by summing these dimensions is used to measure the level of corporate environmental information disclosure (EID). The index covers core contents such as institutional certification, conceptual objectives, management systems, implementation actions, risk management, compliance, and honors, providing a relatively comprehensive reflection of corporate environmental information disclosure.

Environmental information disclosure fundamentally serves as a credible commitment signal regarding a company’s environmental responsibilities to the market. The physical distance and cultural differences between cross-border e-commerce enterprises and overseas markets exacerbate the risk of information asymmetry. High-level environmental information disclosure conveys signals of sustainable development to international consumers, investors, and regulatory bodies by disclosing environmental certifications, management systems, and honors. To a certain extent, this can offset “greenwashing” suspicions, reduce compliance-related doubts from international markets towards emerging economy enterprises, thereby amplifying the marginal contribution of cross-border e-commerce enterprises to green innovation. Additionally, by disclosing environmental information to regulatory bodies, companies can demonstrate their commitment to compliance, which also helps mitigate environmental penalty risks.

Environmental information disclosure can drive green innovation by reallocating resources. To avoid green trade barriers, companies proactively enhance their green management levels and increase their investment in green initiatives. These investments manifest as explicit green management systems. Furthermore, companies with high green transparency are more likely to secure government subsidies and green financing, which support their green innovation efforts. Lastly, environmental information disclosure can also drive green innovation through innovation incentives. Environmental education and training enhance employees’ ability to absorb green technologies, facilitating the conversion of tacit knowledge into explicit technical applications.

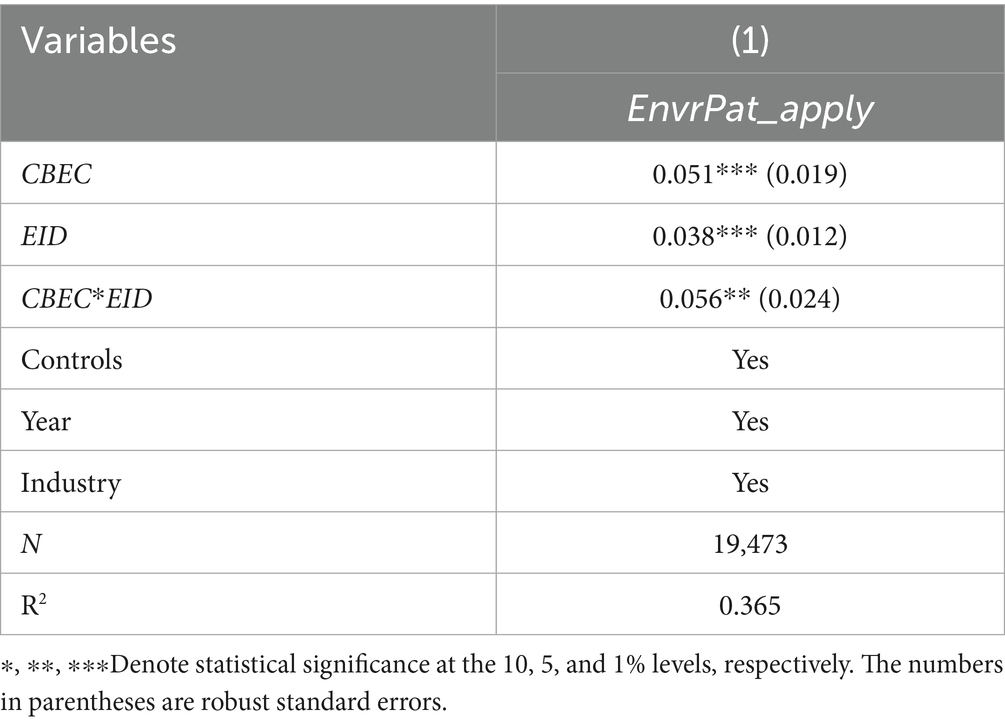

According to Equation 4, the results of the moderating effect test are shown in Table 8, aligning with theoretical expectations, with the interaction term’s coefficient being 0.056 and statistically significant at the 5% level. This indicates that environmental information disclosure has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between cross-border e-commerce operations and green patent applications, amplifying the innovative incentive effects of cross-border e-commerce operations. Additionally, environmental information disclosure itself has a positive impact on green patent applications. The more comprehensive the disclosure of a company’s environmental policies, management frameworks, and circular economy models, the more it reflects the management’s strategic emphasis on environmental protection, and the more likely it is to increase investment in green innovation and strengthen corporate green innovation activities.

5.6 Heterogeneity analysis

5.6.1 High-technology enterprises

To investigate the impact of cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) on green innovation among high-tech enterprises, the study divides the sample into high-tech enterprise samples and non-high-tech enterprise samples, conducting separate regression analyses. Following the classification by Lin and Fu (2024), enterprises with “China Securities Regulatory Commission” industry codes C25, C26, C27, C28, C29, C31, C32, C34, C35, C36, C37, C38, C39, C40, I63, I64, I65, and M73 are categorized as high-tech industry enterprises, while the remaining enterprises are classified as non-high-tech industry enterprises.

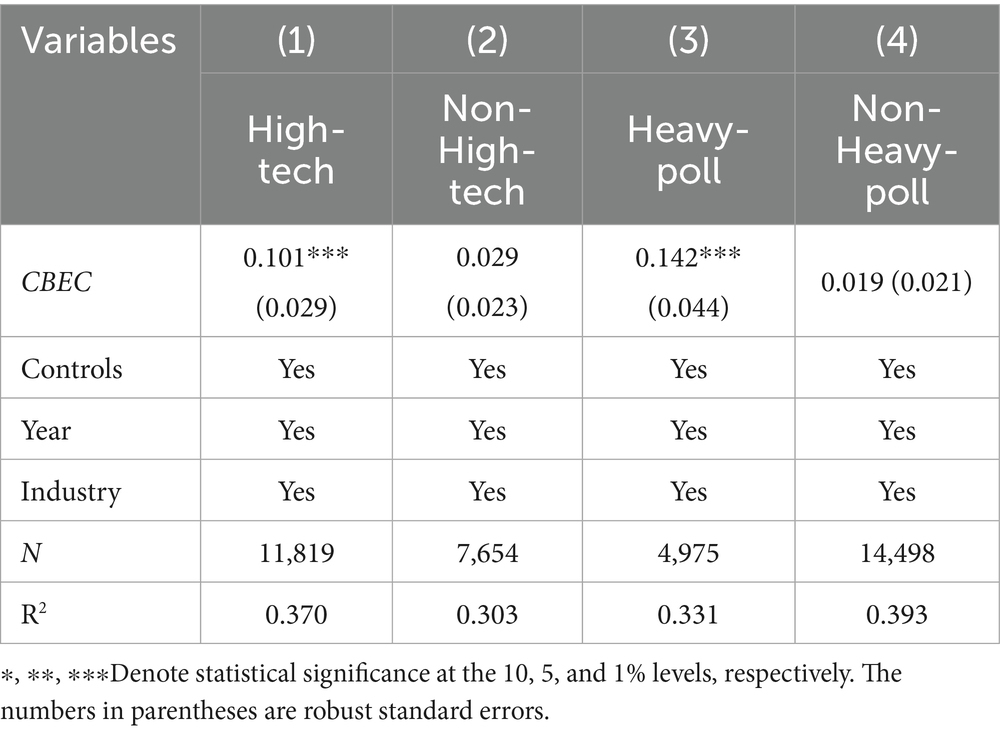

In Table 9 column (1), the coefficient of CBEC for high-tech enterprise samples is 0.101 and is significant at the 1% significance level. In contrast, the coefficient of CBEC for non-high-tech enterprise samples does not reach significance, as shown in column (2). For high-tech enterprises, the promotion of cross-border e-commerce on green innovation is more pronounced. High-tech enterprises may inherently possess advantages in technology research and development and innovation capabilities. Cross-border e-commerce provides them with broader markets, more opportunities for technological exchanges, and resource acquisition channels, thereby further stimulating their potential for green innovation. For non-high-tech enterprises, the development of cross-border e-commerce does not significantly enhance their green innovation levels, possibly due to their relative weaknesses in technology, funding, and talent. Even with the implementation of cross-border e-commerce, they may struggle to effectively leverage opportunities for green innovation.

5.6.2 Heavy-polluting enterprises

This paper refers to the heterogeneity test conducted by Liu and Chen (2024), which categorizes enterprises based on whether they operate in heavy-polluting industries. Heavy-polluting industries are defined according to the “Catalogue of Environmental Protection Verification for Listed Companies” issued by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment in 2008, specifically including “China Securities Regulatory Commission” industry codes B06, B07, B08, B09, C17, C19, C22, C25, C26, C27, C28, C30, C31, C32, C33, and D44. Non-heavy-polluting industries refer to those outside the scope of this Catalogue.

Table 9 column (3) indicates that for enterprises in heavy-polluting industries, the promotion of green innovation through cross-border e-commerce is more pronounced, with a regression coefficient of 0.142, which is significant at the 1% level. For non-heavy-polluting industries, the regression coefficient for cross-border e-commerce is only 0.019 and is not significant, as shown in column (4). The engagement of heavy-polluting enterprises in cross-border e-commerce has facilitated green innovation, possibly due to the high environmental protection pressures and stringent international market requirements, which have prompted these industries to increase their investment in green technology research and development. Additionally, cross-border e-commerce enables heavy-polluting enterprises to access advanced international environmental protection technologies and management experiences, thereby facilitating the spillover effect of technology. For non-heavy-polluting industries, environmental protection pressures are relatively low, and green innovation is more influenced by internal factors such as scale and profitability, resulting in limited stimulation from cross-border e-commerce on their green innovation.

5.6.3 State-owned enterprises

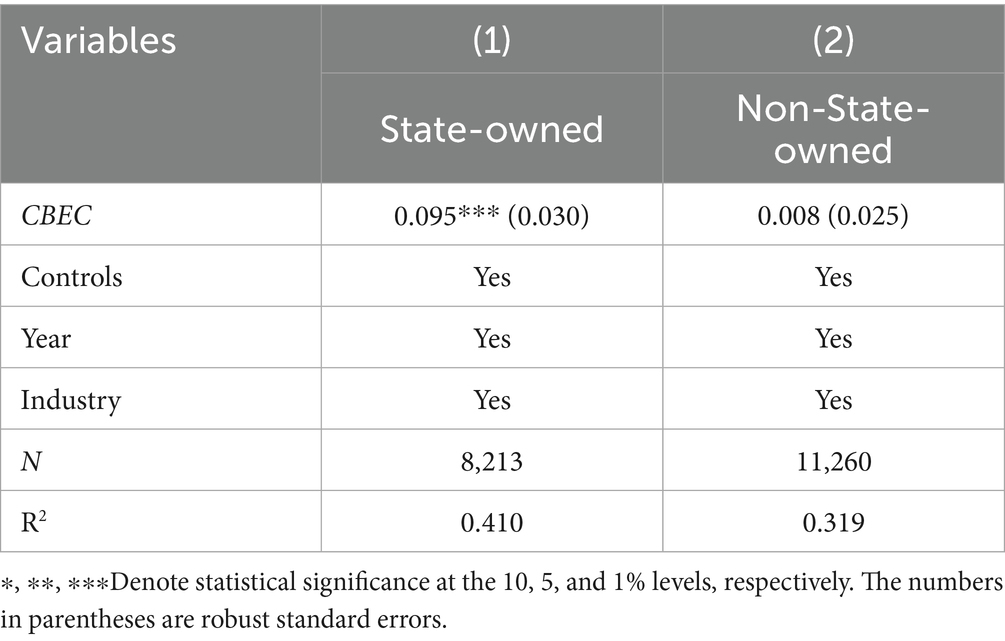

Grouped regression analysis is conducted based on the ownership nature of enterprises. Compared to non-state-owned enterprises, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) demonstrate significant advantages in innovation. SOEs leverage their high credit ratings, substantial asset bases, and institutional resources such as policy support to access diverse financing channels at lower costs. Non-state-owned enterprises, lacking implicit government guarantees, often face higher debt and equity financing rates for innovation projects, resulting in significantly higher capital costs compared to SOEs. This financing constraint disparity is reflected in the intensity of R&D investment.

Table 10 column (1) indicates that for SOEs, the CBEC coefficient is 0.095, which is significant at the 1% level, highlighting the pronounced promotional effect of cross-border e-commerce on green innovation. In contrast, the CBEC coefficient for non-state-owned enterprises is 0.008, which is not significant, as shown in column (2). SOEs, when engaging in cross-border e-commerce, are better positioned to integrate resources and utilize policy advantages to introduce advanced international green technologies and management experiences, thereby driving their green innovation development.

The significantly stronger promoting effect of CBEC on green innovation in SOEs, compared to their non-SOE counterparts, may initially appear counterintuitive given the conventional wisdom regarding the latter’s market agility and innovative efficiency. However, this finding can be reconciled by considering the distinct nature of green innovation and the institutional context in China. Green innovation often requires substantial upfront capital investment and involves long payback periods with high uncertainty. In this context, SOEs’ inherent advantages in resource mobilization become decisive. Their superior access to policy-directed bank loans and government subsidies allows them to better absorb the high costs and risks associated with importing and integrating advanced international green technologies and management practices through CBEC channels. Furthermore, aligned with national strategic priorities such as the “dual-carbon” goals, SOEs are often incentivized to pursue foundational green technological breakthroughs, which are more likely to be captured by patent-based metrics. Conversely, while non-SOEs may exhibit stronger adaptive innovation in market-oriented applications, their constrained access to capital and policy support might limit their ability to engage in large-scale, patent-generating green innovation in the short term, leading to an statistically insignificant coefficient. This divergence highlights that the drivers of green innovation extend beyond market adaptability and are profoundly shaped by the resource-based and institutional dimensions of firm ownership.

6 Conclusion

This paper examines the impact of cross-border e-commerce on corporate green innovation, conducting an empirical analysis using a multi-period difference-in-differences model based on data from Chinese listed companies from 2013 to 2023. The main findings are as follows:

First, the development of cross-border e-commerce significantly enhances the level of corporate green innovation. Its positive impact is primarily reflected in its promotional effect on the number of green patent applications, indicating that cross-border e-commerce has gradually become an important driver of green technology development for enterprises.

Second, the mechanism analysis shows that cross-border e-commerce indirectly promotes green innovation by alleviating financing constraints and facilitating corporate digital transformation. Cross-border e-commerce provides enterprises with more profit opportunities and financing channels, thereby mitigating the financial shortages faced during green innovation processes. The development of cross-border e-commerce also necessitates enterprises to enhance their digital capabilities, such as optimizing supply chain management and improving production efficiency, which indirectly promote green innovation. Additionally, corporate environmental information disclosure plays a positive moderating role in this process, further enhancing the effectiveness of green innovation.

Third, the heterogeneity analysis indicates that the promotional effect of cross-border e-commerce on corporate green innovation varies significantly. High-tech enterprises, enterprises in heavily polluting industries and state-owned enterprises demonstrate outstanding performance in green innovation. From a regional perspective, enterprises in central and western regions benefit more than those in eastern regions, reflecting the inclusive effect of cross-border e-commerce and its role in promoting balanced regional development.

6.1 Theoretical implications