- 1University of South Australia, Clinical and Health Sciences, Adelaide, SA, Australia

- 2Australian Research Centre for Interactive and Virtual Environments, University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA, Australia

Introduction: As a defining feature of virtual reality, the sense of presence has been a focal point of research for decades. Navigating the extensive body of presence research can be challenging, yet it is essential for understanding the evolution of the concept over time, recognising the contributions of key scholars, and charting new research pathways. This study applied a bibliometric analysis to map networks of influence and conceptual frameworks spanning over 30 years of presence research to highlight the disciplines, authors, articles, and concepts that have gained prominence in scholarly discourse.

Method: Bibliographic data for 6636 documents from 1992 to 2024 were extracted from Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus citation indexes for analysis using Biblioshiny and VOSviewer. Outputs from WoS and Scopus databases were combined to provide high-quality bibliographic records for co-occurrence, co-citation, and bibliographic network analysis using Biblioshiny and VOSviewer. An extended analysis of contemporary research discusses considerations for presence research.

Results: Publication output since 2015 has grown rapidly. A source analysis reflects a dominance of the discipline of computer science and engineering, while interdisciplinary connections in applied settings are an emerging area of growth. Citation and publication output are heavily dominated by the top 10 authors, indicating a reliance on relatively few contributors. Terminology that co-occurs with presence remains dominated by the technical aspects of immersion and experience design, while also reflecting more recent growth in the use of virtual reality in applied settings. This demonstrates that recent contributors and newer concepts have yet to be significantly reflected in global presence research.

Discussion: This analysis underscores the need to view presence as a multidimensional construct that requires a multidisciplinary approach and methodologies providing user-centred, holistic perspectives that embrace the nuances of individual psychological experiences. The present bibliometric review provides a valuable overview of the evolving landscape of presence research as a complement to previous, more focused systematic and scoping reviews. This bibliometric analysis of the past 30 years of research demonstrates that presence remains a defining concept in virtual reality and a field that warrants further investigation and development to achieve compelling, relevant and memorable virtual reality experiences.

1 Introduction

The sense of presence has been studied and cited as a defining feature of virtual reality (VR) for over 4 decades (Krassmann et al., 2024; Lombard et al., 2000; Minsky, 1980; Slater et al., 2022; Tran et al., 2024). A computer-generated world viewed through a head-mounted display (HMD) immerses users in an experience that no other technology can provide (Sutherland, 1968). Despite knowing they have not left their physical environment, users can become so immersed that the virtual world almost entirely dominates their perceptual experience. This sense of ‘being there’ in this virtual world has been described as the sense of presence (Heeter, 1992; Lioce et al., 2020; Minsky, 1980; Sanchez-Vives and Slater, 2005; Sheridan, 1992; Steuer, 1992; Sheridan, 1996; Wirth et al., 2007). In those moments when immersive virtual reality provides the most compelling experiences, the sense of presence most aptly describes the user experience. Presence is, therefore, the most investigated construct in VR research (Wienrich and Gramlich, 2020). While the sense of presence experienced in well-designed virtual reality has been described as providing some of the most immersive, meaningful, and memorable experiences for users, the term remains an elusive concept to define and measure (Kelly et al., 2024; Slater et al., 2022; Souza et al., 2021; Tran et al., 2024).

Therefore, the questions that emerge are:

Does the concept of presence continue to hold relevance in the research and design of virtual reality experiences?

What are the disciplines, authors, articles, and concepts that have, for better or worse, emerged as predominant in scholarly discourse?

What do the patterns of scholarly discourse reveal regarding the evolution of research within the field?

Where might opportunities for future research be identified through an extended qualitative analysis of contemporary publications?

The current study uses bibliometric methods to explore over 30 years of research to present a cartographic overview of the research landscape, with insight into publication themes, terminology, influential researchers, and key publications. A bibliometric analysis reveals the evolution of the field over time, highlighting dominant themes that may perpetuate biased practices to be challenged by emerging research methodologies and frameworks. The search string (“Presence” and “virtual reality” (“VR”)) was used to extract 6,636 documents from the Web of Science and Scopus databases to be analysed using VOSviewer and Biblioshiny. Until now, no bibliometric review has considered the field of presence in VR. Given the exponential growth of research within this domain, the present moment represents an ideal opportunity for such an analysis.

1.1 Presence in virtual reality

The sense of presence is a concept that resonates with laypeople, artists, designers, and scholars, offering multiple dimensions of relationality, profound existential questions, and diverse interpretative frameworks (Beck et al., 2011). Indeed, the term ‘being’—embedded in most definitions of presence as the sense of ‘being there’—has been a focus of intense philosophical discourse for thousands of years, from Plato to Descartes, Edmund Husserl to Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and continues to be highly relevant in contemporary discussions, particularly in relation to the experience of presence in virtual reality (Chalmers, 2022; Clark and Chalmers, 1998; Mantovani and Riva, 1999; Sartre, 1956; Merleau-Ponty, 2014). Presence is a term, however, that evades reductive definitions as any attempt at categorisation inevitably excludes essential dimensions of the presence experience (Kelly et al., 2024; Slater et al., 2003). Consequently, there remains a need to adequately describe what makes presence such a compelling concept in VR research and to offer practical frameworks to guide both scholarly inquiry and design practice. This current study aims to enhance scholarly discourse by providing a bibliometric overview of over 3 decades of presence research.

At this point, it is important to note the distinction between immersion and presence. Slater and Wilbur (1997) consider immersion to refer to the objective technical specifications required to provide the virtual experience to users (Bowman and McMahan, 2007). Also framed as perceptual immersion, it is “the set of sensorimotor and effective valid actions supported by the system” (Skarbez et al., 2021). In contrast, presence is understood to be the subjective psychological experience of the user (Wiepke and Heinemann, 2024). The phrase “immersive VR” (IVR) is frequently used in the literature to refer to virtual experiences that involve a head-mounted display (HMD) that entirely occludes the vision of a user’s physical environment, providing a virtual environment that surrounds them in 360° (Bodzin et al., 2021; Slater, 2009). An HMD enables the user to turn their head to look around the environment and, in some virtual worlds, to move amongst objects or other VR user avatars (Mancuso et al., 2024; Sanchez-Vives and Slater, 2005; Soler-Domínguez et al., 2020). If full spatial audio is enabled within the design, moving closer to a sound source will make it more audible, and users can locate a sound by turning their heads and moving closer to the source (Larsson et al., 2010). Driving the global expansion of VR has been the release of stand-alone headsets that operate without the need to connect to a powerful computer to drive the graphics required to generate virtual experiences. These stand-alone headsets now come at a cost point that enables home users to enter a host of virtual worlds from the comfort of their homes. Despite this more rapid recent progress, widespread implementation as an education modality and through enterprise applications remains in its infancy (Aebersold and Gonzalez, 2023; Mota et al., 2024; Radianti et al., 2020; Rojas-Sánchez et al., 2023).

1.2 Bibliometric reviews

Bibliometric reviews offer a range of mathematical and statistical methods to map complex networks of publications within a given field of research (Donthu et al., 2021). Bibliometric reviews have become increasingly popular due to the improved accessibility of bibliometric software for individuals without programming expertise, the capacity to manage extensive volumes of bibliographic data, and the production of high-impact research (Donthu et al., 2021). The proliferation of scientific research in many fields has required literature review approaches that enable researchers to extract and analyse insights from publications that can number in the thousands. What emerges from the visualisations of these networks is a birds-eye view of a vast field of study, revealing networks of collaboration, evolving terminologies, and patterns of influence (Mukherjee et al., 2022). Bibliometric reviews enable researchers to explore topics more broadly and objectively across many thousands of publications, providing a cartographic summary of the intellectual structure of a field through an analysis of the networked connections between publications (Donthu et al., 2021). It is acknowledged that quantitative bibliometric measures do not alone reflect the entirety of academic research in any given field. To provide a necessary analytical balance, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or scoping reviews typically offer a focused scope, tighter inclusion criteria, and an in-depth exploration of more specific questions. Taken together, bibliometric analyses alongside scoping, meta-analyses and systematic reviews provide a comprehensive view of a field of study.

Until now, no bibliometric review has considered the field of presence in VR. While several reviews focusing on a select group of papers have attempted to refine and formalise definitions, the broader application of the concept of presence in VR is largely unmapped and fragmented across many research fields. These reviews have proven valuable, as evidenced by the number of attributed citations and contributions to academic discourse in the field of VR presence. For example, Skarbez et al. (2017), receiving 309 citations at the time of this review provides an extensive survey of presence constructs found throughout the literature. Similarly, Felton and Jackson (2022) unify disparate definitions and identify presence determinants. Wilkinson et al. (2021) limited their search to PsycINFO and ProQuest in their mini-review of presence and immersion through a thematic content analysis of 17 articles. A more recent review by Chen et al. (2023) examines ways in which presence constructs have been applied in the field of interactive marketing. A systematic review by Wiepke and Heinemann (2024) explored the factors that influence presence in virtual reality learning applications. From yet another perspective, Caroux (2023) narrowed their focus to 55 articles from the Web of Science Core Collection, PsycINFO, and Medline to investigate the relationship between game design and presence. The role of immersive media as a tool for persuasive communications is examined in a review by Breves (2023) focusing on 108 articles taking spatial presence as the core focus. Oh et al. (2018) carried out a systematic review of social presence, examining the implications of various definitions and antecedents, gathering 495 citations. An early review of social presence theories and measurement was carried out by Biocca et al. (2003), culminating in 1221 citations. Further reviews have considered presence in connection to embodiment (Schultze, 2010), human behaviour in virtual environments (Barranco Merino et al., 2023), nonverbal communication (Xenakis et al., 2022), sound design (Chaurasia and Majhi, 2022), social robots (Almeida et al., 2022), flow and narrative absorption (Pianzola, 2021), clinical care (Hilty et al., 2020), presence questionnaires and physiological correlates (Grassini and Laumann, 2020), cybersickness (Weech et al., 2019, with 453 citations), and emotions (Diemer et al., 2015, receiving 585 citations). The following reviews consider presence in applied settings such as serious games (Basille et al., 2023), augmented reality games (Marto and Gonçalves, 2022), learning in virtual reality (Hsu and Wang, 2021; Krassmann et al., 2024), pilot training (Walters and Walton, 2021), social-emotional learning (Hamzah et al., 2023), and cybertherapy (Spagnolli et al., 2014). More recently, a systematic review by Kukshinov et al. (2025) found that the use of presence questionnaires is frequently not a valid or reliable measure of presence, and questionnaire modifications perpetuate “confusion about the fundamental aspects of presence” (p. 8). The present bibliometric review will complement these previous reviews by providing a valuable overview of presence in VR research that is unavailable through the limited scope of systematic or scoping reviews.

A bibliometric analysis is carried out using two main techniques: performance analysis and science mapping (Donthu et al., 2021). A performance analysis examines contribution measures, such as the number of publications and citations per year, which become proxies for productivity and influence. Science mapping examines the relationships within a network through techniques such as co-citation analysis, bibliographic coupling, and co-occurrence analysis. Bibliometric reviews, therefore, require access to bibliographic data that include document titles, abstracts, keywords, and authors. Co-citation analyses and bibliographic coupling require access to complete reference lists and, therefore, provide a unique insight into the ways in which publications, authors, and institutions are interconnected. Bibliographic coupling examines the relatedness between documents, authors, or journals based on the extent to which they share identical references. For example, two papers are considered more bibliometrically coupled if their reference lists include a number of identical papers. A co-citation analysis considers document, author, or journal relatedness based on how often they are cited together (Ma et al., 2022). For example, two papers frequently included in the reference lists across multiple publications have a strong co-citation relationship. Keyword co-occurrence networks can also be used to visualise terminology used across a body of scientific literature. A co-occurrence network analysis extracts and visualises the relationships between terms in titles, abstracts, and keywords of a literature set to provide a map of conceptual structures. A bibliometric review, therefore, provides valuable insight into large fields of study to reveal key researchers, pivotal papers, emerging themes, and network dependencies not available through other literature review methods. The diversity and spread of presence research make bibliometrics an ideal approach to objectively gain insight into this complex field (Kraus et al., 2022; Lim and Kumar, 2024). A further aim of this study, as advocated by Mukherjee et al. (2022), is to go beyond descriptions of the quantitative measures entailed in performance analysis and science mapping to challenge critical theoretical frameworks that dominate the extant literature and uncover novel approaches for design and research.

2 Materials and methods

Selecting the source of bibliographic data is a central consideration for a bibliometric review. The Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus databases were selected because they are regarded as two of the largest world-leading multidisciplinary citation databases (Pranckutė, 2021; Zhu and Liu, 2020). Both provide high-quality bibliographic records and, most importantly, a complete list of references necessary for co-citation and bibliographic analyses. Google Scholar, in contrast, offers limited search capabilities and no reference lists despite possibly providing more comprehensive coverage (Wouters et al., 2015).

WoS and Scopus databases have been shown to contain highly overlapping records; however, sufficient differences exist indicating that selecting only one database would inevitably exclude papers only available in the other source (Echchakoui, 2020; Visser et al., 2021; Wouters et al., 2015). Caputo and Kargina (2022), Kumpulainen and Seppänen (2022) and Ullah et al. (2023) have demonstrated methods for integrating bibliographic data from WoS and Scopus to comprehensively understand a research landscape. While merging data from both WoS and Scopus creates data-wrangling hurdles, these challenges can be outweighed by the importance of gathering a data set that is as comprehensive as possible to ensure that critical authors and papers are not excluded from analysis. Irregularities and duplicates in bibliographic records can be corrected using systematic processes and iterative corrections. Our approach began with a detailed data identification process to ensure all relevant data were extracted from WoS and Scopus (see Section 2.1). Data cleaning involved combining the two data sets from each database, the removal of duplicate or irrelevant documents, and the identification of data irregularities during the creation of the tables and data visualisations (see Section 2.2).

For this study, Biblioshiny–an open-source R package from Bibliometrix (Aria and Cuccurullo, 2017) version 4.0.0 (available at https://www.bibliometrix.org/home/index.php/layout/biblioshiny) – was used in conjunction with VOSviewer version 1.6.20 (van Eck and Waltman, 2010, https://www.vosviewer.com/). Biblioshiny provides a user-friendly web interface to access Bibliometrix without the need for coding and was used in the current study to convert the WoS and Scopus files to a format amenable to merging and to provide overviews of the entire dataset. Biblioshiny also provided clear visualisations of the bibliographic data, ideal for preliminary quantitative analysis (see Figures 2–7) and data cleaning. VOSviewer was then selected to create the network visualisations not available in Biblioshiny. VOSviewer uses the Leiden algorithm to iteratively map and cluster nodes based on calculations of similarity (Traag et al., 2019). VOSviewer applies a probabilistic calculation of similarity using “association strength normalisation” resulting in coloured clusters of closely related nodes [for a detailed discussion of normalisation calculations, refer to van Eck and Waltman (2009)]. VOSviewer optimisations provide flexible ways to adjust visualisation parameters, zoom and pan across network maps, search results, and overlay visualisations of additional parameters. “Fractional counting” used for calculating link strength in co-citation or bibliographic coupling network maps provided a more balanced view of parameter counts than “full-counting” methods by reducing the excessive weighting influence of documents with larger numbers of authors [see van Eck and Waltman (2018) for more details]. Combined, VOSviewer and Biblioshiny present multiple perspectives on a bibliographic dataset that go beyond citation counts as proxies for impact. They examine how publications, authors and terminology are interconnected giving insight into the structure of a scientific landscape.

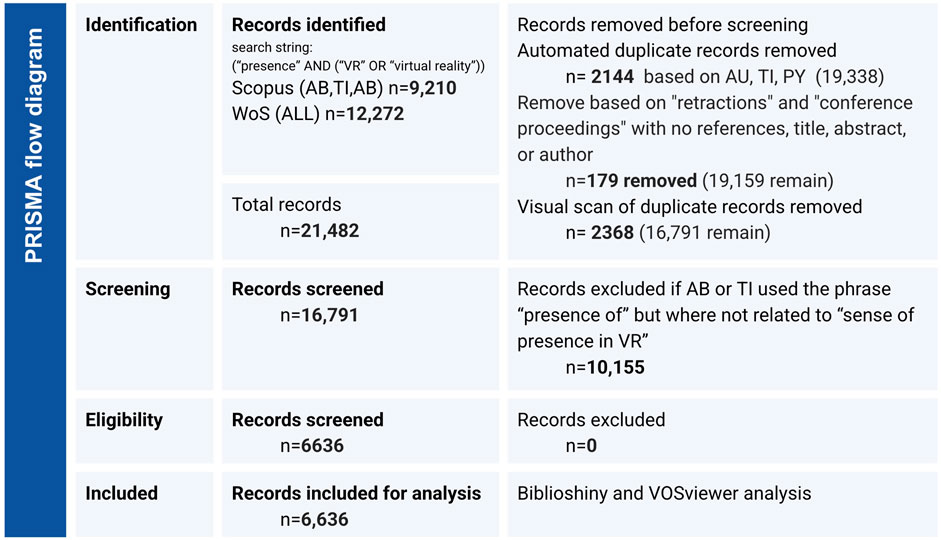

The workflow for the current study followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) reporting guidelines, as illustrated in Figure 1 (Page et al., 2021). Although PRISMA was designed primarily for systematic reviews, the workflow provides a useful structure for systematically and transparently reporting each stage of the review process (Page et al., 2021).

Figure 1. A summary of the process following the PRISMA workflow. Title (TI), author (AU), abstract (AB) and publication year (PY) (Page et al., 2021).

Data analysis followed a sensemaking process involving an iterative motion between scanning, sensing, and substantiating to examine “where plausible meanings and rationales [can be] ascribed to an observed phenomenon, subject, or trend after rigorous evaluation, with the insights obtained having significant implications for decision-making” (Lim and Kumar, 2024). Scanning was required while adjusting algorithm parameters to become familiar with the various network maps produced in VOSviewer, to examine a map’s initial usefulness and to detect data errors. Sensing involved a deeper analysis of the resultant network maps to understand the underlying dynamics and relationships that gave rise to the emergent patterns. Substantiating involved a deeper reading of publications that emerged as prominent in network maps. The third stage also included searches for papers that offered novel insights but were less prominent in the network maps. An extended analysis of these papers is beyond the scope of this bibliometric analysis; however, this paper will present potential future research directions to showcase links to the current study.

2.1 Data identification, search, and extraction

Inclusion criteria were broad and inclusive of book chapters, peer reviewed articles, conference presentations, and theses. Book reviews, letters, publications in languages other than English, retractions, and conference proceedings with no bibliographic data were excluded. WoS and Scopus were searched in June 2024 using the following search strings, yielding a total of 21,482 records:

Scopus: TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Presence” AND (“Virtual Realit*” OR “VR”)) yielding 9,210 results.

WoS: ALL = ((“Presence” AND (“Virtual Realit*” OR “VR”))) yielding 12,272 results.

Scopus records were downloaded in one CSV file (BibTeX format was unavailable for such a large file download). WoS records could be downloaded in BibTeX format using the “Full Record and Cited References” option, allowing 500 records to be downloaded one at a time. Once downloaded, the WoS files were opened in a text editor and then copy-pasted into one combined document.

Following the work of Caputo and Kargina (2022), the WoS and Scopus data were merged by importing the raw data into Biblioshiny and then immediately saving them as two Microsoft Excel files, in effect aligning formatting. The Scopus and WoS files were then opened in Microsoft Excel, arranged vertically on the screen so the WoS document was aligned under the Scopus file, then, the columns in the WoS spreadsheet were rearranged to match the tags in the Scopus sheet. Finally, the WoS data could then be manually copied into the Scopus master spreadsheet to merge the two data sets.

2.2 Data cleaning

Several separate systematic and iterative processes were required to clean the data set. First, duplicate records were removed, and second, records that included presence in the title or abstract but did not relate to presence in VR were removed.

2.2.1 Duplicate removal

The find and remove duplicates feature of Microsoft Excel was used for a combination of the Title (TI) AND author (AU) AND publication year (PY) fields; however, this process was insufficient to remove all duplicates. As stated by Ullah et al. (2023) “human decision-making will always need to be involved in the selection and merging process”. In this case, the most effective method in Excel involved using Conditional Formatting (in the Home Tab) with Highlight Cell rules to highlight duplicate values. A visual scan of the highlighted TI, AU, abstract (ABS) and/or PY fields, although lengthy, produced the most thorough and reliable method to identify and mark duplicate records. Once marked, the sheet was reordered, and duplicates were deleted. For consistency, the Scopus record was retained in most cases, and the duplicate WoS record was deleted. As the analysis through VOSviewer and Biblioshiny proceeded, further duplicate or formatting discrepancies were discovered and corrected in the Microsoft Excel file.

2.2.2 Dealing with the “presence of” phrase

A significant challenge for the database search was the many different ways that “presence” was used in the title or abstract fields. For example, presence was frequently used in a sentence where the “presence of” a factor was under investigation and, in many cases, these articles were not related to the study of presence in VR. The search also brought in articles that included authors with “vr” in their names. Furthermore, there was no consistency in the authors’ selection of presence as a keyword, which rendered a keyword search insufficient for the retrieval of all presence-related publications. As a result, it was not possible to use the WoS or Scopus search engines to discriminate between the use of the phrase “presence of” in unrelated studies. Consequently, the search string (“Presence” AND (“Virtual Realit*” OR “VR”)), was used to capture all documents and data cleaning was carried out in Microsoft Excel to remove irrelevant titles.

The following process was used to highlight potentially irrelevant articles with coloured text and a high-contrast background to enable a visual scan through the Microsoft Excel sheet. Firstly, conditional formatting was employed to highlight any TI, AB, or Keyword cells that contained the term ‘presence’ with a high-contrast background colour. Secondly, a Microsoft Excel macro was constructed to search for terms and to make text colour changes. The following sequence was used:

1. “Presence” and “Presence” changed to lighter pink (colour code 7).

2. “Presence of” and “Presence of”, “presence/absence”, and “presence or absence” “Presence and absence” changed to dark blue (colour code 32).

3. “Sense of presence” and “Sense of presence” (including “sensation of presence”, “immersion”, “copresence”, “embodiment”, “level of presence”, “levels of presence”, “feeling of presence”, “feelings of presence”, “co-presence”, “feeling of presence”, “presence questionnaire”, “telepresence”, “being there”, “cybersickness”, “virtual presence”, “tele-presence”, “psychological presence”, “immersive presence”, “spatial presence” and “social presence”) were changed to yellow (colour code 6) for ease of identification of relevant articles.

As a result, articles that contained “presence of” without other phrases relevant to the current analysis could be identified and marked for removal (these fields in the Excel spreadsheet were highlighted in yellow in step (3)). This method combined automated processes to reduce the errors introduced by human decision-making for relevance. If it was not clear whether an article was relevant, the article was included since it would be unlikely to significantly impact the overall data analysis, because calculations of similarity for co-citation, co-occurrence, and bibliometric coupling would be very low for an article not cited within the field of presence research.

3 Results

The resultant data set now included 6,636 articles that addressed presence in VR in some way. Several articles addressed the concept of presence as the primary subject of investigation, while others identified presence as a crucial factor in the selected research topic. Additionally, some articles merely referenced presence within the context of their background discussions. All were considered relevant to this analysis with the aim of surveying all papers that describe presence in VR as playing a role in their investigation.

3.1 Overview

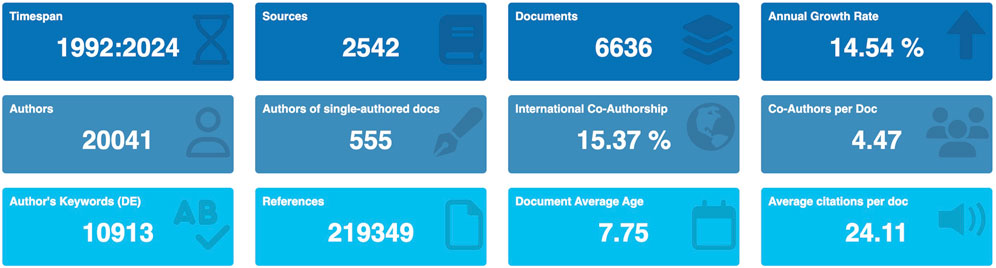

A total of 6,636 documents (which included written works such as conference papers, journal articles, and book chapters) were included for analysis using Biblioshiny. Figure 2 shows the time span from 1992 to June 2024 and includes 20,041 authors, 2,542 sources (which include journals, repositories, publishers and conference proceedings), and 219,349 references (extracted from reference lists found in document bibliographies). Please refer to the Supplementary Table S1 for the complete bibliographic dataset of 6636 references.

3.1.1 Annual scientific publication

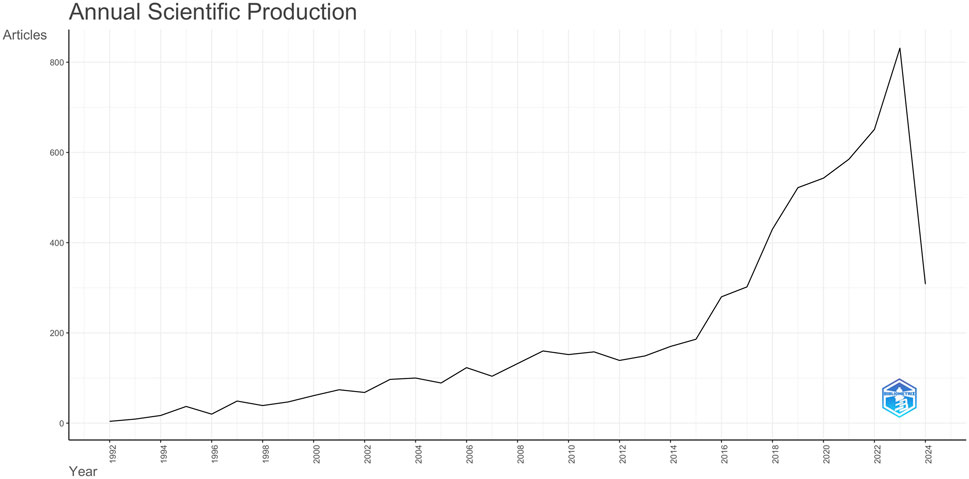

While consistent publication growth has occurred since 1992, annual scientific production exhibits exponential growth, with the most dramatic increase beginning in 2015 (see Figure 3). The average annual growth rate was 14.54%. The sharp drop in 2024 appears because the data set only includes one-half of the year.

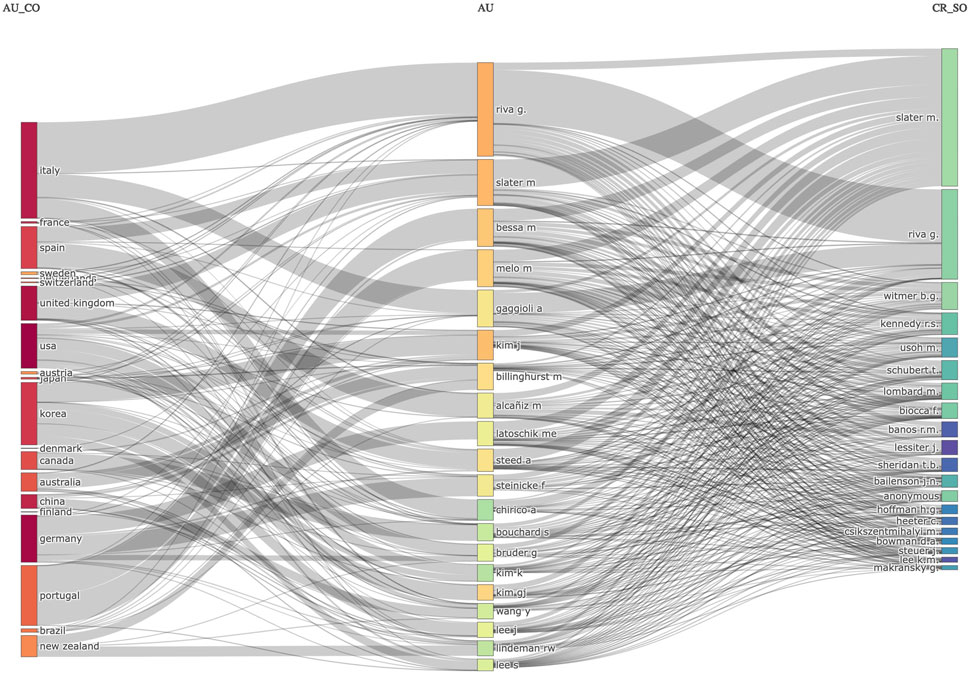

3.1.2 Three-field plot of author-country, authors, and cited references

A three-field plot is a Sankey diagram that traces the flow of interactions across three bibliographic domains. Figure 4 provides a view of interactions from author country (AU_CO) on the left, author name (AU) in the middle, and cited references by name (CR_SO) on the right (Riehmann et al., 2005). Sankey diagrams provide a means to explore the complex information flows in highly connected systems. The size of each rectangular node is proportional to the strength of the interrelationships between each column.

Figure 4. The three-field plot (Sankey diagram) of author country (AU_CO) on the left, author name (AU) in the middle, and cited references by name (CR_SO) on the right, created using Biblioshiny.

In this case, while Italy shows the largest node, the spread of countries indicates no single dominant country amongst the most prominent authors. Several authors are affiliated by country, such as Riva and Gaggioli in Italy, Latoschik and Steinicke in Germany, Kim J, Kim GJ, Lee J and Lee S in the Republic of Korea, and Bessa and Melo in Portugal. In general, thick lines of connection indicate that most authors are strongly affiliated with one country, while thin lines of connection to other countries suggest that some international collaborations are evident. Line weightings connecting to cited authors (CR_SO) on the right indicate a heavy focus on frequently cited authors. For example, Slater in the right column strongly connects to all authors in the middle column. Authors, at times, frequently cite themselves, as is the case for Riva and Slater. There is also a high incidence of authors (AU) in the middle column, highly connected to many of the commonly cited authors (CR_SO) in the right column. Therefore, while country affiliations dominate researcher collaborations, citations indicate strong reference connections across commonly cited authors.

3.1.3 Most relevant sources

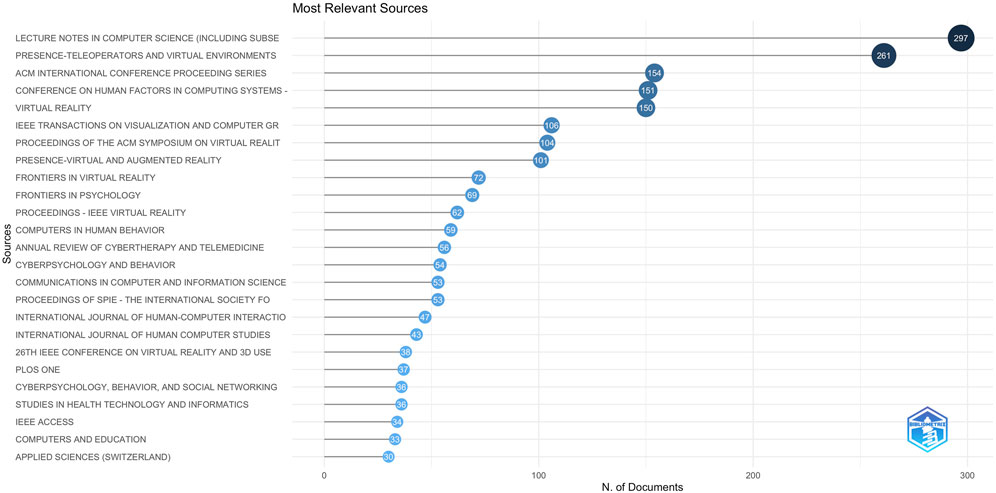

A total of 2,542 sources were represented that refer to presence in virtual reality. The top 25 sources are illustrated in Figure 5, showing a dominance of the fields of computer science and human-computer interaction journals in the top 10. Conference proceedings are also prominent in this data set as evidenced by references to Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) and ACM (Association of Computing Machinery) publications. Psychology, communications, health, and education fields appear as related fields lower in the list. This source analysis reflects a dominance of computer science and engineering sources, while interdisciplinary connections in applied settings are emerging growth sectors. Note that “Presence-Virtual and Augmented Reality” was formerly “Presence-Teleoperators and Virtual Environments”, both titles included in Figure 5.

3.1.4 Authors’ production over time

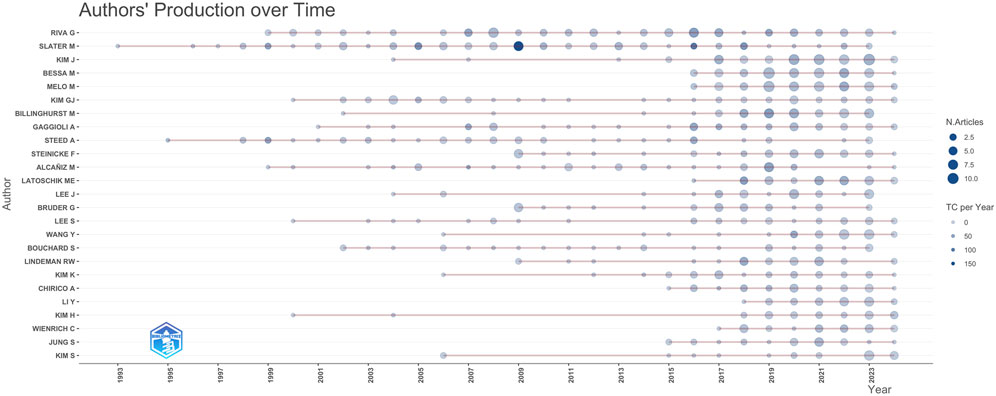

A longitudinal plot of authors’ production over time is presented in Figure 6 where the size of each node indicates the number of articles published, and the shade indicates tonal darkness proportional to the total citations of articles from that year. A dominant feature is the rapid increase in the number of researchers from 2015 onwards and the evenness of distribution of total citations during this period. A number of authors with a long history of research related to presence in VR include Riva, Slater, Steed, Alcañiz, Kim GJ, Gaggioli, Billinghurst, Lee S, Bouchard, Lee J, Wang, Kim J, Kim H, and Kim S.

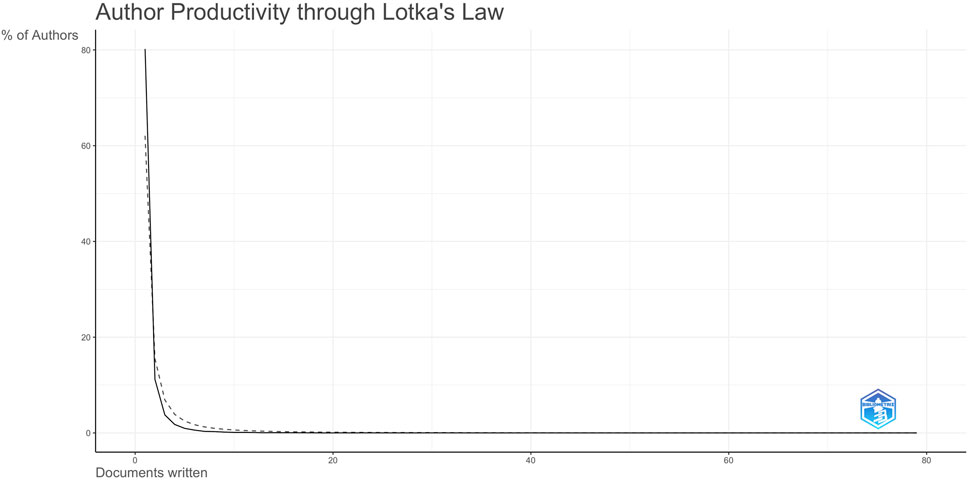

3.1.5 Lotka’s law

A classical bibliometric law used in scientometrics is Lotka’s law, which sheds light on author productivity, positing that a small number of authors disproportionately contribute to an overall body of research while most authors contribute less (Lotka, 1926). Figure 7 produced with Biblioshiny demonstrates such a pattern of heavily imbalanced productivity in presence research, with 16,073 authors contributing one publication. Alternatively, 20,031 authors collectively produced a total of 468 publications, whereas the top 10 authors contributed 480 publications.

3.2 Network analysis

VOSviewer version 1.6.20 was selected to visualise the following maps for the co-occurrence network, co-citation network, and bibliographic coupling. Detailed VOSviewer settings are provided with each analysis.

3.2.1 Co-occurrence analysis (title and abstract)

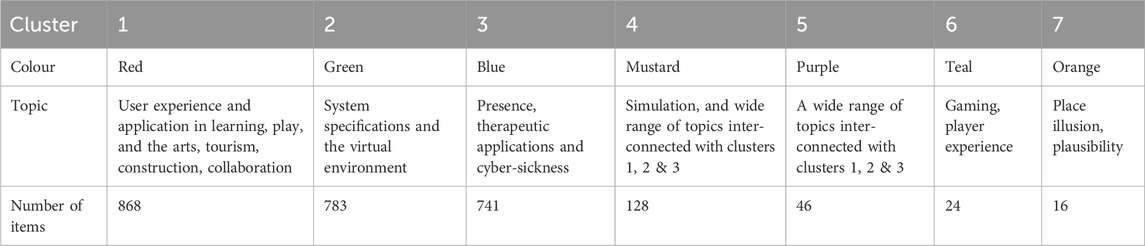

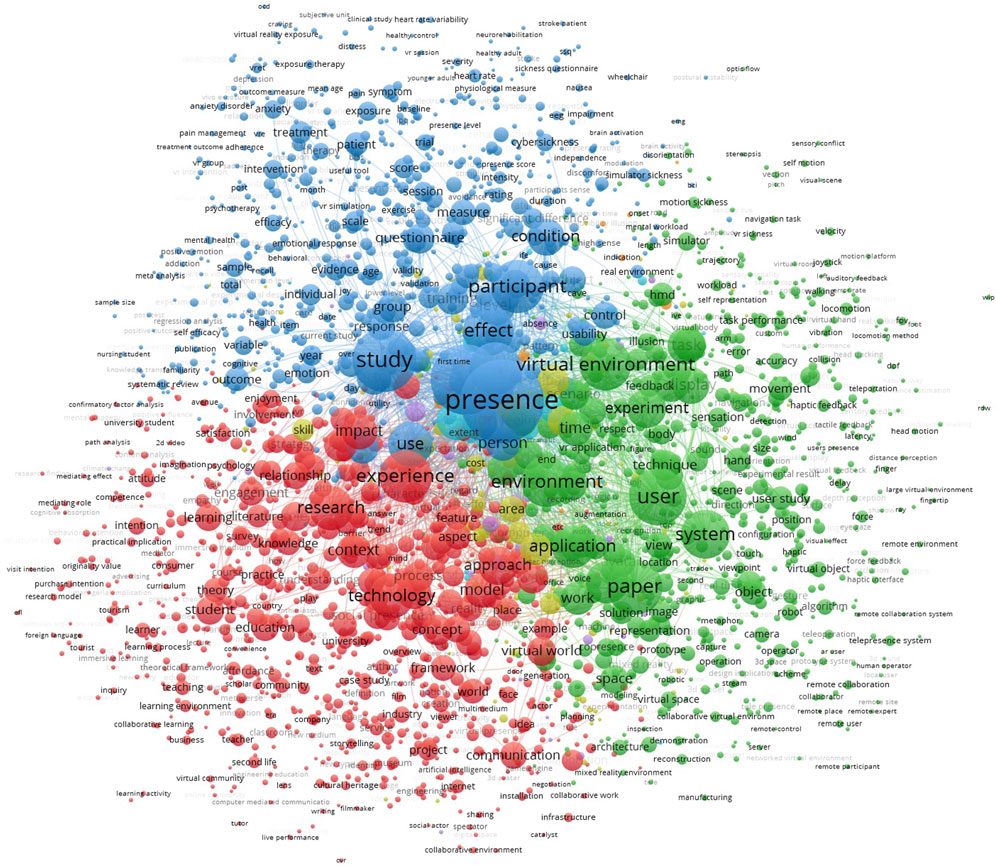

A co-occurrence analysis was carried out for words in the title and abstract fields, representing a measure of the number of documents where two words appear together. The size of each node corresponds to the number of publications where the corresponding term appears (van Eck and Waltman, 2014). The proximity of nodes is proportional to the extent to which terms co-occur. Of the seven clusters created, the first three dominate the visualisation (See Table 1, and visualisation in Figure 8).

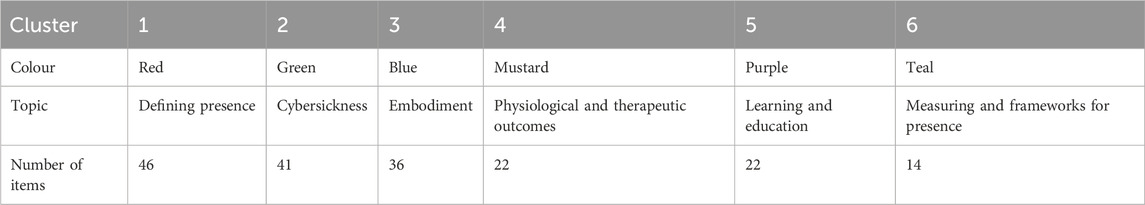

Table 1. Co-occurrence clusters mapped in Figure 8.

Figure 8. A co-occurrence map generated by VOSviewer. Node size reflects ‘total link strength’, colour indicates the cluster to which a node belongs, and lines between nodes represent links. The distance between nodes approximates relatedness (van Eck and Waltman, 2018).

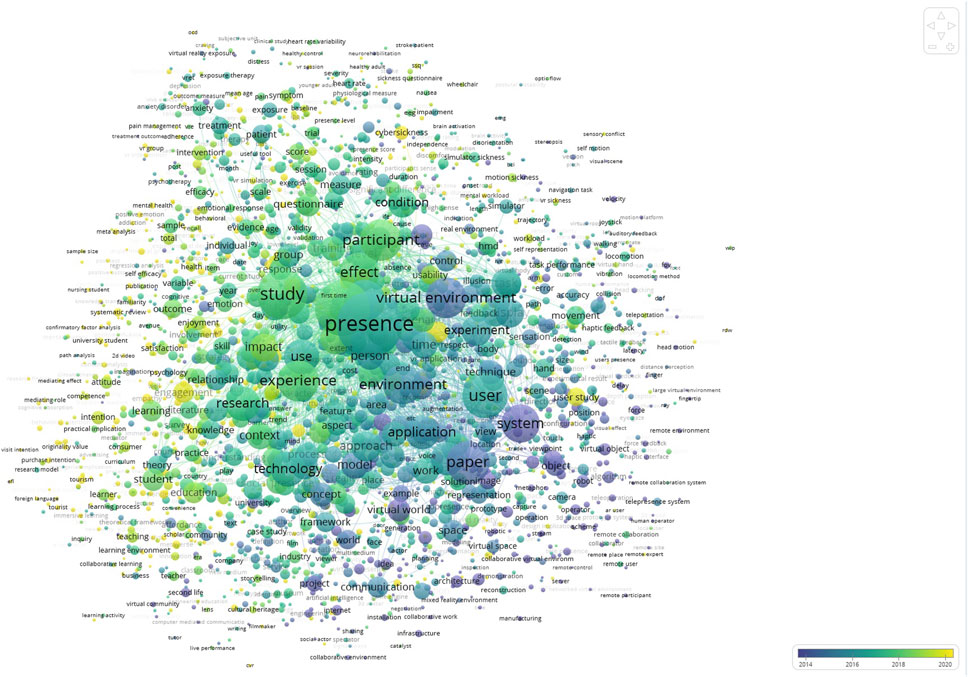

The VOSviewer settings for Figure 8 and Figure 9 were as follows: Type: Co-occurrence Matrix (map) created based on text data; Fields: Title and abstract (‘Ignore structured abstract labels’; ‘Ignore copyright statements’); Counting method: Binary counting; Thesaurus used to correct formatting errors; Minimum number of occurrences of a term: 10 (Of the 99,735 terms, 2,606 met the threshold); Number of terms chosen: 2,606 chosen; Visualisation: Weights: ‘Total link strength’ (not ‘total occurrences’, or ‘links’); Colours: based on Clusters in Figure 8 and “Ave. pub. Year” in Figure 9.

Figure 9. A co-occurrence average year of publication overlay map generated by VOSviewer. Node size reflects ‘total link strength’, coloured by the average year of publication.

As expected, the term presence features in the central portions of this visualisation in the blue cluster 3, as does virtual reality, sense, immersion, experience, simulation and participant. The Blue cluster centrally features terms related to studies of presence including terms such as ‘study’, ‘effect’, ‘participant’, ‘data’, ‘level’ and ‘factor’. Moving toward the upper left quadrant, the terminology centres on therapeutic applications with terminology such as ‘intervention’, ‘efficacy’, ‘treatment’, ‘anxiety’, ‘disorder’, ‘symptom’, and ‘exposure’. Terms related to the measurement of presence such as ‘questionnaire’, ‘measure’, ‘reaction’, and ‘evidence’ also occur within the blue cluster. To the upper central area are terms that relate to adverse effects of VR including ‘cybersickness’ and ‘simulator sickness’.

The green cluster 2 is centred on the ‘user’ and the technical elements required to provide an ‘environment’ or ‘virtual environment’. Other terms related to the technical aspects of immersive experiences such as ‘application’, ‘interaction’, ‘system’, ‘display’, ‘avatar’ and ‘performance’ appear in this lower right quadrant. The red cluster 1 included the largest number of terms with a focus on the ‘experience’ of users particularly in to context of ‘learning’, ‘education’, ‘engagement’, and ‘teaching’.

The mustard, purple, teal and orange clusters are largely hidden behind the three dominant clusters however if the larger nodes in these clusters are selected in the VOSviewer map, connecting lines to the first three clusters indicate that these nodes are interconnected throughout the map. This is a unique feature of this map. In contrast, co-occurrence networks in other fields of study frequently show very distinct clusters positioned apart from each other on the map. Of note in Figure 8 are the very few occurrences of terms such as ‘illusion’, ‘place illusion’, ‘plausibility’ and ‘coherence’ which contrasts with their prominence in recent literature reviews in the field of presence (Skarbez et al., 2017; Weber et al., 2021). Similarly, the ‘gaming’ teal cluster 6 includes only 24 terms with lower occurrences compared with the larger clusters, and is therefore not prominent in the presence of VR literature. Cluster 6 includes terms such as ‘gameplay’, ‘player’, and ‘game’.

The co-occurrence visual overlay illustrated in Figure 9 presents an average year of publication spanning from 2014 to 2020. This data indicates a notable increase in the frequency of the term’s utilisation over the past decade. The lower right quadrant tends toward an average age of 2014, while the upper left quadrant tends toward an average age of 2020. Terms in 2014 are centred on descriptions of the immersive features of a VR experience. These include dominant terms such as system, environment, technology, object, scene, display, real-time, tracking, etc. The upper and lower left quadrant terms tend toward applied settings for VR, such as intervention, efficacy, outcome, investigation, engagement, treatment, teaching, learning, consumer, and user experience. The top right quadrant features a range of terminology such as cybersickness, sensory conflict, heart rate, intensity, and other terminology describing the potentially adverse effects of VR. Overall, the colour gradient from deep blue (average age 2014) to yellow (average age 2020) indicates a tendency toward emerging terms related to VR applications in various fields, such as tourism, construction, training, education, and medical interventions focusing on mental health, anxiety, psychotherapy, and virtual reality exposure therapy.

A search for the term presence in the VOSviewer map reveals a host of directly related words: cognitive presence; copresence; experienced presence; greater presence; high presence; higher presence; higher social presence; human presence; igroup presence questionnaire; immersive presence; low presence; overall presence; personal presence; physical presence; presence; presence effect; presence experience; presence inventory; presence level; presence questionnaire; presence rating; presence research; presence score; presence theory; remote presence; self presence; social presence; social presence theory; spatial presence; subjective presence; telepresence; telepresence system; user presence; users presence; and virtual presence (refer to Supplementary Table 2 for a complete list of all 2608 terms).

It is significant to note that of the 6636 publications found, only 2038 included presence as a keyword.

Presence remains a frequently used term in VR research and is associated with many aspects of the VR experience, as evidenced by its centrality in the map (Figure 9) and the number of connections to other related words across the network. Furthermore, far from being a simple conception, presence touches on all aspects of virtual reality implementation. Therefore, presence remains a relevant and multidimensional term. For a detailed review of presence terminology, readers are encouraged to refer to reviews by Skarbez et al. (2017), Oh et al. (2018), Felton and Jackson (2022), Weber et al. (2021), Wilkinson et al. (2021) and Pianzola (2021).

3.2.2 Co-citation network

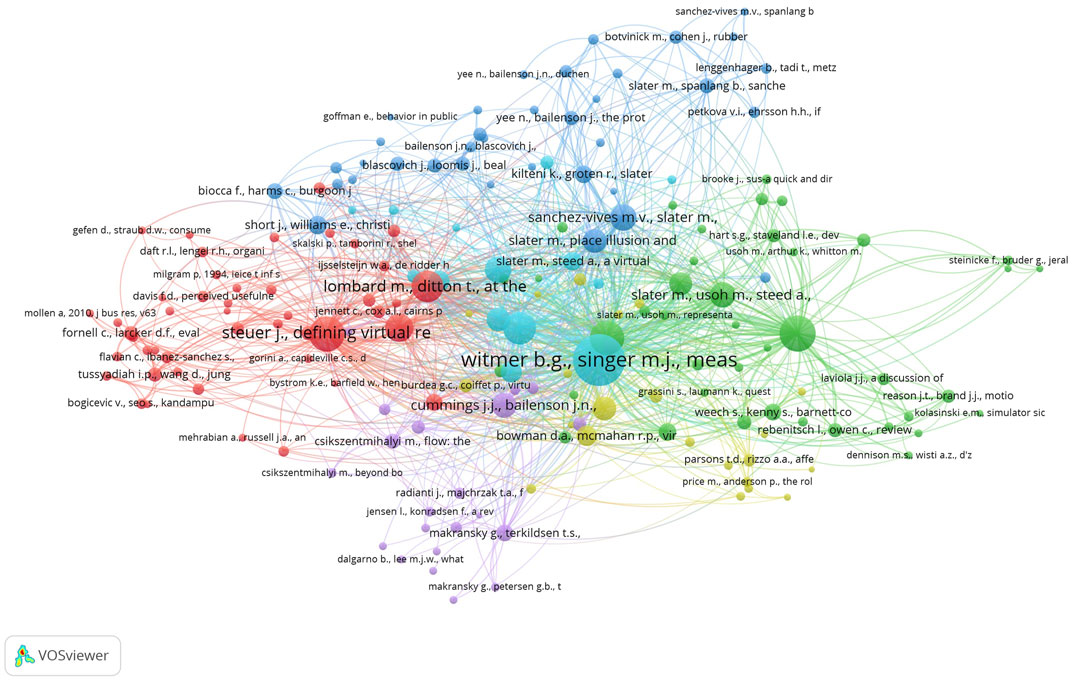

The VOSviewer settings for Figure 10 were as follows: Type: co-citation analysis; Counting method: Fractional; Unit of analysis: Cited references; Thesaurus used to correct formatting errors; Minimum number of citations of a cited reference: 20 (Of 215,696 cited references, 181 met the threshold); Output: 6 clusters (see Table 2). Normalisation: by association strength.

Figure 10. A co-citation map generated by VOSviewer. Node size reflects ‘total link strength’, colour indicates the cluster to which a node belongs, and lines between nodes represent links. The distance between nodes approximates the relatedness (van Eck and Waltman, 2018, p. 9).

Table 2. Co-citation clusters as displayed in Figure 10.

A co-citation network analysis of cited references examines the degree to which references are cited within the same document (Perianes-Rodriguez et al., 2016). Each node represents a single reference, and the size of the circle is proportional to the “total link strength” of that reference. The distance between two nodes indicates the link strength between two references as a measure of their relatedness (van Eck and Waltman, 2018). A connecting line indicates the co-citation links, and node colours indicate which cluster the reference belongs to. A co-citation map provides insight into the most interconnected documents within the global research network. In this case, there are 181 references organised into six clusters as outlined in Table 2 below. Figure 10 illustrates the co-citation map generated by VOSviewer.

The distinctive feature of this graph is the very high levels of relationality between coloured clusters. While distinct clusters were generated, there remains a high level of connection between clusters, indicated by the numerous interconnected curved lines and the centrality on the map of the largest nodes. The publications indicated by the central large nodes in the map have topics that focus on defining, measuring, and establishing a framework to understand presence (Cummings and Bailenson, 2015; Heeter, 1992; Lee, 2004; Lombard and Ditton, 1997; Sanchez-Vives and Slater, 2005; Slater et al., 1994; Slater and Wilbur, 1997; Steuer, 1992; Witmer and Singer, 1998). Furthermore, these large nodes around which the clusters form are highly interconnected across clusters and are located in relatively close proximity to each other, indicating high levels of relatedness (van Eck and Waltman, 2018).

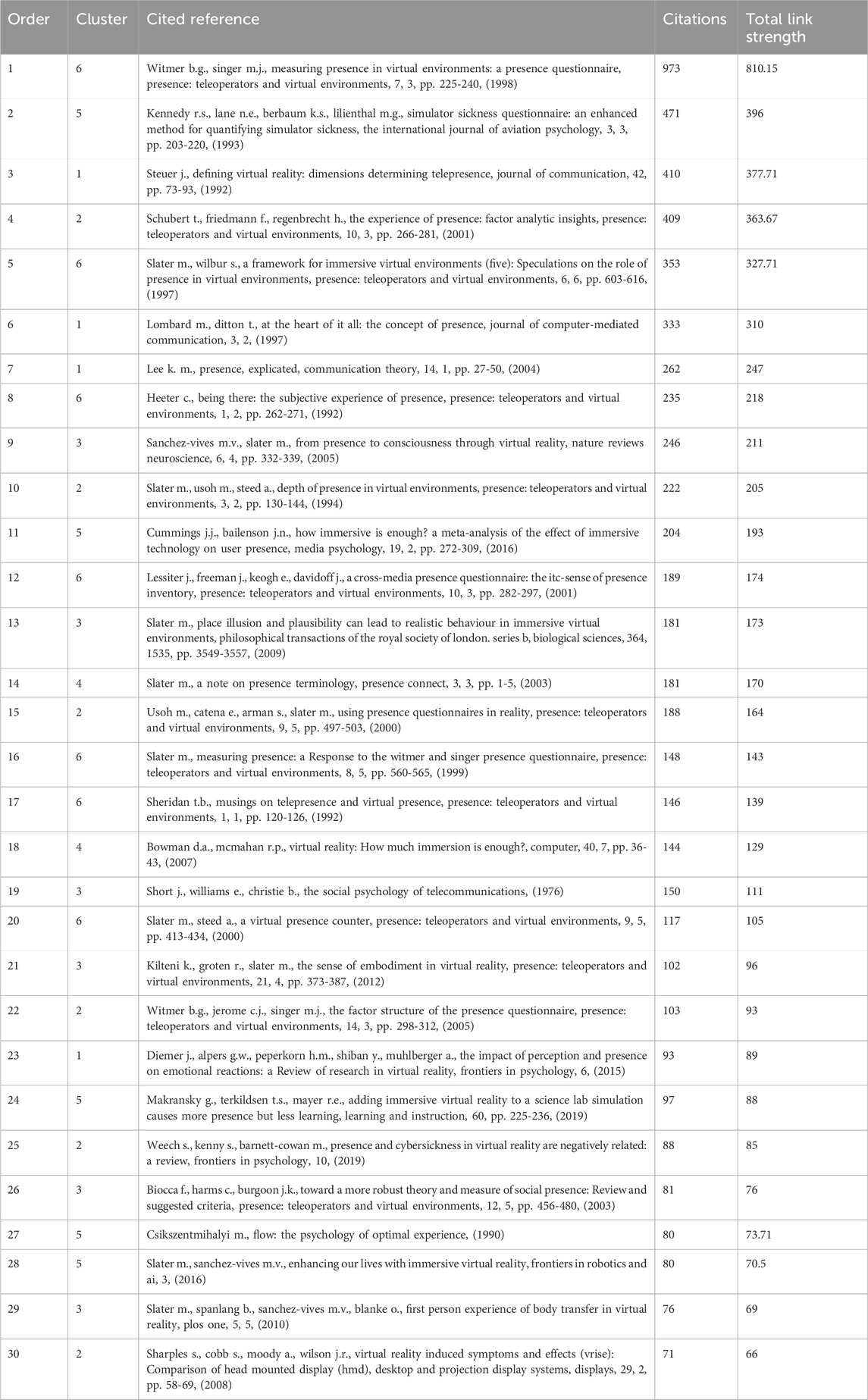

The top 30 references by citation count and “total link strength” were published between 1976 and 2019 (average of 2002, see Table 3). After the top 30 references shown in Table 3, the total link strength shows only a marginal decrease among the remaining references. Despite the rapid growth of publication output since 2015, the 181 references that met the link strength threshold for inclusion in Figure 10, have an average age of 13 years (see Supplementary Table S3 for a complete list of all 181 references included in Figure 10). This shows both the extended period in which presence has been researched and discussed while also highlighting the elusive nature of generating one authoritative definition and definitive measure of presence. The majority of the earlier articles are concerned with describing, defining, and explicating the concept of presence (Cummings and Bailenson, 2015; Heeter, 1992; Lee, 2004; Lombard and Ditton, 1997; Sanchez-Vives and Slater, 2005; Slater et al., 1994; Slater and Wilbur, 1997; Steuer, 1992; Witmer and Singer, 1998), while more recent articles expand to explore the impact of presence on users (Diemer et al., 2015; Makransky et al., 2019; Sharples et al., 2008; Slater and Sanchez-Vives, 2016; Weech et al., 2019).

Table 3. Top 30 cited references ordered by ‘total link strength’ extracted from the co-citation map using VOSviewer.

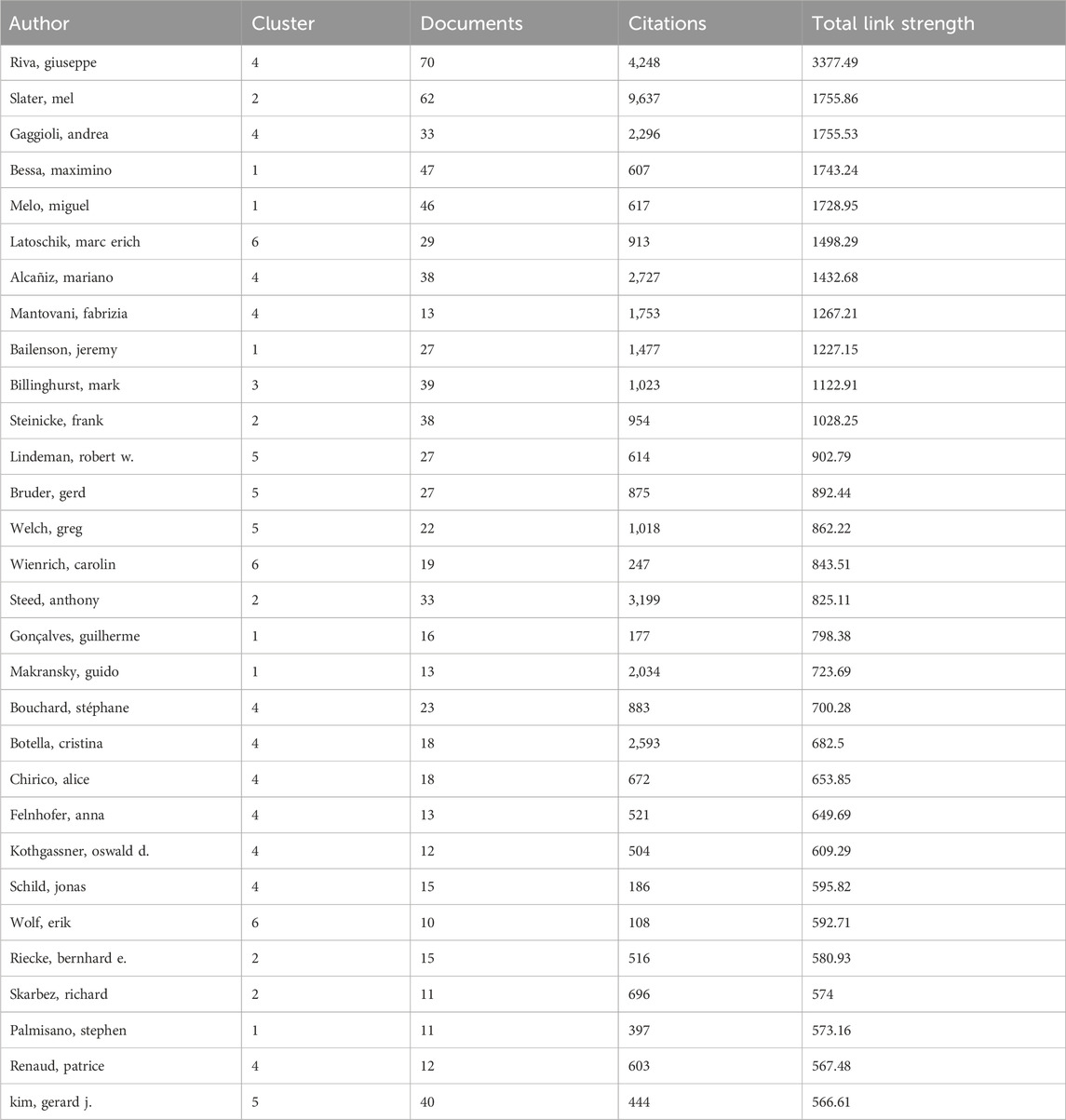

3.2.3 Bibliographic coupling

A bibliographic coupling analysis of author networks is a method that establishes a connection between two authors based on the number of shared references in the documents they have authored. If two authors cite one or more of the same document, they become bibliographically coupled. Bibliographic coupling networks are used to identify research communities and groups of authors working on similar projects and topics within similar domains. Analysing the relatedness between authors in a bibliographic network can also reveal influential researchers and thought leaders within a field of inquiry. The network map in Figure 11 provides a social network analysis for visualising how authors are interconnected.

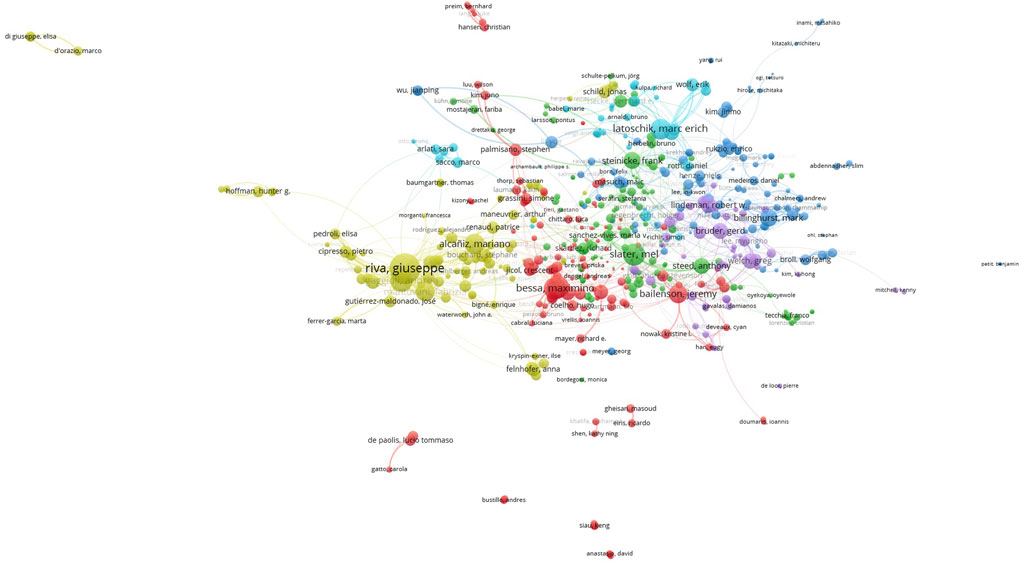

Figure 11. Bibliographic coupling map network of researchers generated by VOSviewer using fractional counting methodology–Node size reflects ‘total link strength’, colour indicates cluster to which a node belongs, and lines between nodes represent links. The distance between nodes approximates relatedness (van Eck and Waltman, 2018, p. 9).

A bibliographic coupling network analysis of authors examines the degree to which authors cite the same document (Perianes-Rodriguez et al., 2016). Each circle represents a single author, and the size of the circle is proportional to the “total link strength” of that author. The distance between two circles indicates the link strength between two authors as a measure of their relatedness (van Eck and Waltman, 2018). Therefore, authors who frequently co-author will be located in close proximity to each other. For example, ‘melo, miguel’ and ‘bessa, maximino’ appear in very close proximity in Figure 11; a scan through their output reveals that they frequently co-author publications and therefore, their bibliographies are closely related. A connecting line indicates the coupling links, and node colours indicate which cluster the reference belongs to. A bibliographic coupling map provides insight into authors who are most interconnected within the global research network, with a focus on presence in virtual reality. Some of the 545 authors in the network were not connected, so VOSviewer provides the option only to include the 541 authors representing the most extensive set of connected authors. In this case, the 541 authors were organised into 34 clusters. The minimum cluster size was adjusted to 35 to make the map more readable. Figure 11 illustrates the bibliographic coupling map generated by VOSviewer.

The VOSviewer settings for Figure 11 and Figure 12 were as follows: Analysis Type: Bibliographic coupling Unit of analysis: Author; Counting method: fractional counting (Maximum number of authors per document: 25); Thesaurus used to correct formatting errors and duplications; Threshold: Minimum number of documents of an author: 4; Minimum citations of an author: 20. Number of authors: 546; 541 connected authors included. Clustering: min. cluster size: 1; Weights: by Total link strength. NOTE: Adjust settings to select Overlay Visualisation: Weights: by Total link strength, Scores: Average publication date.

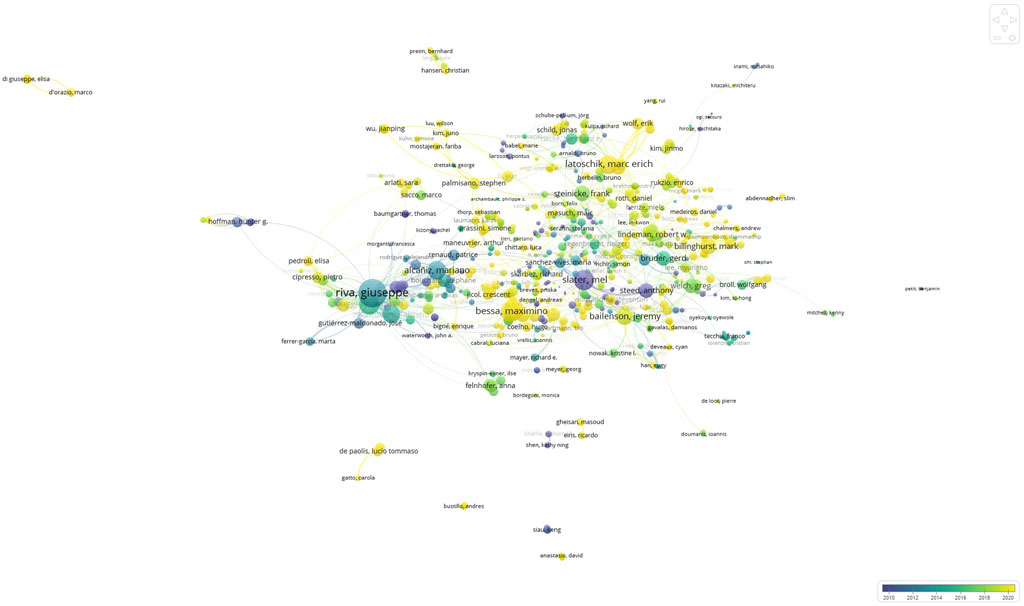

Figure 12. An overlay bibliographic coupling network map of researchers generated by VOSviewer using fractional counting methodology. Colour indicates the average age of publication. Node size reflects ‘total link strength’, and lines between nodes represent links. The distance between nodes approximates relatedness (van Eck and Waltman, 2018, p. 9).

Figure 12 shows the same data set and map with an overlay that colours each node based on the average publication year, providing a longitudinal view of author output and network relatedness. Darker teal coloured nodes indicate an average year closer to 2010 and the yellow coloured nodes tend toward an average year of publication of 2020.

Similar to the co-citation network above, the bibliographic coupling map presents a number of distinct clusters of authors that align with instances of co-authorship. However, there are also evident moderately high levels of relationality between clusters. Several large clusters are centred around the authors with the highest link strength (see Table 4). Cluster 4 appears distinct to the left of the map (Figure 11), while clusters 1 and 2 are more central and interconnected throughout the network.

Table 4. Top 30 authors ordered by ‘total link strength’ extracted from the map of bibliographic coupling using VOSviewer.

4 Discussion

This bibliometric analysis of the past 30 years of research demonstrates that presence remains a defining concept in virtual reality. The exponential growth in usage (see Figure 3) signifies that it continues to hold relevance in an expanding array of applied settings. Nevertheless, it is also clearly demonstrated that, beyond the concept of ‘being there’, how presence is defined continues to be a focus for ongoing development (Kelly et al., 2024; Slater et al., 2022; Souza et al., 2021; Tran et al., 2024). Figure 5 indicates that virtual reality research is multidisciplinary in nature, yet it is also evident that research outputs have been dominated by the domains of computer science, psychology, telecommunications, and human-computer interactions. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, researchers were drawn to investigating how cognitive, emotional, and sensory factors contributed to a user’s sense of presence (Figure 9 overlay co-occurrence map). The early focus was also on the technical aspects of immersion and the impact of adjusting various parameter settings in virtual reality, such as realism in graphics, spatial audio, haptic feedback, and user interfaces (Figure 9). More recent studies have diversified to explore the application of virtual reality more broadly in domains such as tourism, construction, psychology (such as VR exposure therapy), education and training (Figure 9). Of note in Figure 8 is that current presence in VR terminology—such as ‘place illusion’, ‘plausibility’ (cluster 7 in orange), ‘coherence’, ‘embodiment’ (the blue cluster 3 in Figure 10; Table 2), and ‘flow’—do not feature in the 6636 articles reviewed in this study. It is also notable that despite being an important feature in virtual reality design, ‘sound design’ (12 occurrences), ‘spatial audio’ (20 occurrences) or ‘audio’ (93 occurrences) receive very little attention in the presence literature (Figure 8). Compare this with terms such as ‘haptic’ (297 occurrences), ‘display’ (864 occurrences), ‘virtual environment’ (1728 occurrences), ‘environment’ (1643), ‘visual’ (654 occurrences) and ‘realism’ (401 occurrences), indicating a more frequent focus in particular on visual aspects of virtual reality design. In comparison, ‘sickness’ (in relation to cybersickness, simulation sickness and motion sickness) accounts for 632 occurrences. The largest growth in terminology usage as seen in the left region of Figure 9 (indicated by the shading of colour from teal to yellow) is in the use of presence in applied settings such as in education, arts, tourism, construction and collaborative environments. A call for further development of interdisciplinary efforts and affordances of virtual reality have been echoed by van der Meer et al. (2023), Chirico and Gaggioli (2023), Chatain et al. (2023), Hartmann and Hofer (2022) and Pianzola et al. (2021).

While many authors in Figure 4 are affiliated with multiple countries, most tend to collaborate primarily with colleagues from one or two specific countries. It is also interesting to note the evenness of distribution of cited authors across the countries of Italy, Portugal, Korea, Spain, UK, USA, Germany and Australia (Figure 4). The Lotka graph in Figure 7 indicates that the discourse has been dominated by a few key authors. This provides a guide for researchers new to the field to understand who the most prominent voices have been, however this may also indicate the potential for bias due the dominance of a small number of authors (Figure 6; Table 4). Figure 6 shows that this is changing as more researchers have become increasingly prolific, especially since 2016. A closer look at output over the last 9 years from these authors also indicates emerging approaches to understanding and researching presence in VR (see Section 4.1).

The results of this current study indicate that the historical emphasis in the VR literature has been on the “technological properties of the system rather than the human abilities or other cognitive/affective variables” (red cluster 2 in Figure 8 and associated Table 1; (Chen et al., 2023). Similarly, the historical focus on technological properties of VR is showing signs of diversifying as user-experience terminology and the expansion of applied settings for VR indicates gradual change (indicated by the yellow terms in Figure 9). Slater and Wilbur (1997) have ascribed these objective technical features of VR to properties of immersion rather than presence, therefore for the scholarly presence discourse to move forward, this distinction needs to continue to become more clearly reflected in the literature. Another imbalance in presence terminology made apparent in Figures 8, 9, is a dominating emphasis on the spatial dimensions of presence, where the user feels that they are ‘there’, with the resultant associated terminology focused on the immersive characteristics of VR that surround the user rather than the psychological experience of presence. This observation is echoed by Kelly et al. (2024), Latoschik and Wienrich (2022) and Riva and Mantovani (2000). Furthermore, Wiepke and Heinemann (2024) found that the personal psychological dispositions of users, such as domain-specific interest, spatial intelligence, agreeableness, and absorption, were the most prominent factors influencing learner presence. This emphasises the influence of socio-cultural factors beyond the technical and virtual features of a VR experience that are yet to be reflected in the extant literature. The dominance of the use of presence questionnaires and quantitative measures of presence is represented in the literature sample by the terms most frequently associated with presence (shown in italics following Figure 9), such as “igroup presence”, “presence inventory”, and “presence score”. The co-citation map (Figure 10) and associated Table 3, presenting the top 30 cited articles, illustrate that descriptions and the use of post-experience presence questionnaires dominate the most commonly cited papers. Despite being the most commonly used measure of a user’s perception of presence, the value of the presence questionnaire has been challenged because it “may bring about the very feelings that it is supposed to measure” (Slater et al., 2022), leading to a “methodological circularity” (Graf and Schwind, 2020; Sanchez-Vives and Slater, 2005). In a recent systematic review by Kukshinov et al. (2025), a lack of standardisation diminishes the reliability of presence questionnaires, which may also lack necessary validation. Questionnaires that examine the there-ness or the realism of an experience are helpful but may not be sufficient to provide insight into the phenomenology of presence. As noted by Kelly et al. (2024) phenomenological methodologies that move beyond the technical descriptions of immersion and prescriptive descriptions of the presence experience are not significantly represented in the literature. A number of studies utilise group discussions and interviews to address this bias, however, these studies do not feature in the extant literature (see Figures 8, 9, and discussion by Slater et al., 2022).

Considering that only a third of the included papers applied presence as a keyword in Scopus and WoS, it follows that a more consistent use of presence as a keyword in related research would facilitate future bibliometric, systematic, or scoping literature reviews. Bibliographic data provide the foundation of searchability for researchers navigating a body of research, therefore, implementing greater consistency in keyword allocation would provide a simple means to connect research from disparate disciplines engaged with presence in VR. The consistent application of presence as a keyword would enable researchers to create database alerts that would give new researchers fast access to a readership interested in their field of research and give readers convenient access to the most current developments in the field of presence research.

The results of this bibliometric review, therefore, present a unique overview of publishing trends in relation to author networks, evolution of presence terminology, seminal papers, and dominant themes in presence research. These papers serve as valuable resources not only for information regarding the evolution of research trends but also potential points of departure for the exploration of emerging concepts in presence research.

4.1 An extended analysis of contemporary publications

The following discussion represents an extended analysis of contemporary publications that present several examples of nascent areas for development that are yet to feature in bibliographic data. These emerging considerations for presence research are not a comprehensive list or an in-depth analysis however they serve to illustrate ways in which future research can both complement and depart from dominant themes evident in the broader presence literature.

One emerging approach capable of considering the multidimensionality of presence is the phenomenological perspective as described by Kelly et al. (2024). A phenomenological approach retains space for the ongoing work of defining and describing key aspects of the user experience while embracing complex systems views where the multiple entangled factors can be considered and approached from different design, implementation, and research perspectives (Libin, 2001). It is at this juncture where opportunities for researchers to explore presence through different ontologies offer holistic approaches to understanding user experiences.

Latoschik and Wienrich (2022) (see Table 4; Figure 11) challenge current presence terminology arguing that “place illusion cannot be the major construct” defining the sense of presence and that illusion is an unnecessary suffix to place or plausibility since all qualia are, by definition, subjective psychological experiences. This is not a new idea. For Mantovani and Riva (1999) who also feature in Table 4 and Figure 11, the meaning of presence is an ontological concept embedded in a sociocultural web of interactions rather than based solely on a literal physical conception of ‘being there’. They aim to escape an artificially dualistic notion of distinguishing between “real” and “virtual” and the dependency of presence on the fidelity of reproduction of physical realities. Therefore, presence is more broadly described as “relational and interactive; from here, we can start to see environments as networks in which people and things construct themselves mutually” (Mantovani and Riva, 1999). This sociocultural concept expands possible avenues for research by considering the experience of presence in a way that recognises the multidimensionality of the human experience of reality. This is particularly relevant when considering VR as an educational modality for meaning-making.

A bibliometric review provides insight into dominant influences within a body of research however it is essential to examine what is not made visible in the network maps. If we stop simply at examining the most visible themes and trends in the presented data, we risk reinforcing these trends without critically analysing whether these trends indicate future directions or a need for change and development. We can take, for example, two recent publications by Pianzola et al. (Pianzola, 2021; Pianzola et al., 2021) to illustrate this point. Pianzola (2021) examined questionnaires most commonly used in studies of “presence”, “flow”, and “narrative absorption”, uncovering the many overlapping concepts and, in the process, revealing how bringing together convergent themes from multiple domains provides useful insights for future design and research. Pianzola et al. (2021) embody these opportunities in their follow-up publication, where they “propose a new cognitive model of presence-related phenomena for mediated and non-mediated experiences” (p. 1) based on predictive processing. As such, a domain that does not feature in this bibliometric review is the contribution of cognitive neuroscience (41 occurrences in the cooccurrence map Figure 8). As highlighted by Pianzola (2021), for example, the concept of predictive processing appears to provide important insights into the phenomenon of presence, however, the impact of such ideas and research is yet to be fully realised in the extant presence research. Neither these papers nor the concepts mentioned (such as ‘embodied cognition’) feature in the bibliometric data.

A further avenue of research related to predictive processing not prominent in the bibliometric data is the cognitive science theory of embodied cognition (Lakoff, 2012; Schubert et al., 2001; Felisatti and Fischer, 2024). This concept is distinct (but not exclusively) from embodiment, which is commonly referred to in VR literature as the extent to which a user integrates virtual entities, such as their avatar, into their personal body representations (see Table 2; Figure 9; Table 4; Forster et al., 2022). In contrast, embodied cognition refers to the ways in which thinking and learning are inseparably entangled with bodily states, actions, and interactions with the environment (Walkington et al., 2023; Wilson, 2002). Walkington et al. (2023) propose a Multimodal Analysis of Embodied Technologies (MAET) to take advantage of the affordances of VR technologies that give users up to 6 degrees of freedom (6DOF), haptics and body tracking, engaging the user’s whole body in a virtual experience. While embodiment in virtual environments is more frequently discussed in the literature (301 occurrences in Figure 8), the bibliometric review revealed that embodied cognition surprisingly receives little mention (no occurrences in Figure 8) despite being a prominent feature of VR technologies where the whole body can be involved and tracked in a virtual experience (Pianzola et al., 2021). As an emerging educational modality, VR is capable of providing interactive, non-linear, dynamic, and multi-sensory simulations engaging the potential of embodied cognition to enhance learning (Johnson-Glenberg and Megowan-Romanowicz, 2017; Liu, 2024; Radianti et al., 2020). Felisatti and Fischer (2024) used bibliometric data to show a rapid growth in the number of journal publications and citations that contain the term ‘embodied cognition’ in the last 10 years. Bibliometric data in the field of presence in virtual reality research does not follow this trend, representing a potential area for future research.

5 Strengths and limitations

A bibliometric analysis provides a view of data from a certain vantage point that risks an over-emphasis on quantitative measures of scholarly output, which may not necessarily reflect the most salient ideas in the extant research. Readers are encouraged to use the presented data to guide further investigations of cited authors, sources, and publications. The CoARA statement on the role of scientometrics in the assessment of research advocates for the need to use a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches in the evaluation of research and that research assessment reform needs scientometrics (Balboa et al., 2024; Mukherjee et al., 2022). Narrative bibliometrics as described by Torres-Salinas et al. (2024) and the sense-making approach outlined by Lim and Kumar (2024) provided methodological guidance to give meaningful context to the presented quantitative data. The reader is also encouraged to explore the list of literature reviews in Section 1.2 to provide additional context to the overview of this bibliometric analysis.

6 Conclusion

Charting the landscape of presence in virtual reality research has provided insight into publication themes, the evolution of terminology, influential researchers, and central documents. In answer to the guiding research questions, the concept of presence continues to hold relevance in the research and design of virtual reality experiences. Defining, measuring, and designing for presence have been the topic of scholarly discourse for over 3 decades and it continues to be an evolving concept. Researchers engage with presence recognising its significance in VR experiences despite being challenged by the idiosyncrasies of individual user perceptions. This bibliometric review suggests that cross-disciplinary connections in the conceptualisation of presence are necessary due to the use of VR technologies in an ever-widening range of applied settings. Despite this growth, what is evident is that this research history has been dominated by computer science and engineering publications. Multidisciplinary approaches open pathways for understanding presence by combining methodologies and conceptual approaches that embrace multiple complex variables. The dominance of quantitative measures of presence highlights the need to explore other methodologies that can provide richer data relevant to the idiosyncratic user experience of presence. The increasing diversity of terminology, authors, and article citations published since 2016 reflects this expanding scholarly conversation. The extended analysis of contemporary publications further revealed where research is beginning to challenge established definitions of presence emphasising the need for future research that complements and departs from dominant themes evident in the bibliometric data.

Patterns of scholarly discourse evident in the network maps have revealed dominant authors, papers, and themes, thereby inviting further discussion about where opportunities lie to challenge established practices and to identify future research opportunities. What is apparent from the wealth of research is that presence is a multidimensional and complex phenomenon contingent on multiple interconnected influences that are entangled in individual subjective human experiences. As an emerging educational modality, presence offers a rich conceptual framework to examine the unique affordances of VR for learning and meaning-making. Similarly, fields such as psychology, communications, and health are showing a significant growth in research output. As the market for virtual reality hardware and content continues to grow, educators, artists, technologists, and scholars can find in the concept of presence rich opportunities to continue to explore how best to implement VR in their own settings.

7 Statements and declarations

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Data collection from the Web of Science and Scopus, and analysis were performed by Philip Williams. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Philip Williams, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statement

The complete bibliographic dataset analysed in this article is included in the supplementary material (Supplementary Table S1). Interactive versions of the network maps are available at https://www.presenceinvr.com. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

PW: Investigation, Resources, Conceptualization, Visualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Data curation, Software. MK: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Investigation, Methodology. DR: Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation. IG: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Supervision, Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. No content was generated using generative AI. All content was created through original authorship by acknowledged contributors. The authors declare that Generative AI was used to help with editing for spelling and correcting grammar.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frvir.2025.1691240/full#supplementary-material

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE S1 | Complete bibliographic dataset as downloaded from Biblioshiny.

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE S2 | Co-occurrence terms included in Figure 8. The number of occurrences and relevance score are included.

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE S3 | Extended version of Table 3 with all 181 references included in Figure 10.

References

Aebersold, M., and Gonzalez, L. (2023). Advances in technology mediated nursing education. OJIN Online J. Issues Nurs. 28, 2. doi:10.3912/OJIN.Vol28No02Man06

Almeida, L., Menezes, P., and Dias, J. (2022). Telepresence social robotics towards co-presence: a review. Appl. Sci. 12, 5557. doi:10.3390/app12115557

Aria, M., and Cuccurullo, C. (2017). Bibliometrix: an r-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Inf. 11 (4), 959–975. doi:10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007

Balboa, L., Gadd, E., Mendez, E., Pölönen, J., Stroobants, K., Cithra, E. T., et al. (2024). Lse impact blog: the role of scientometrics in the pursuit of responsible research assessment. Available online at: https://coara.eu/news/lse-impact-blog-the-role-of-scientometrics-in-the-pursuit-of-responsible-research-assessment/.

Barranco Merino, R., Higuera-Trujillo, J. L., and Llinares Millán, C. (2023). The use of sense of presence in studies on human behavior in virtual environments: a systematic review. Appl. Sci. 13, 24. doi:10.3390/app132413095

Basille, A., Lavoué, É., and Serna, A. (2023). “Presence and embodiment in serious games: a literature review,” in ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, 2023 (New York, NY, United States: Association for Computing Machinery). doi:10.1145/3583961.3583982

Beck, D. E., Fishwick, P. A., Kamhawi, R., Coffey, A. J., and Henderson, J. (2011). Synthesizing presence: a multidisciplinary review of the literature. J. Virtual Worlds Res. 3. doi:10.4101/jvwr.v3i3.1999

Biocca, F., Harms, C., and Burgoon, J. K. (2003). Toward a more robust theory and measure of social presence: review and suggested criteria. Teleoperators and Virtual Environ. 12, 456–480. doi:10.1162/105474603322761270

Bodzin, A., Junior, R. A., Hammond, T., and Anastasio, D. (2021). Investigating engagement and flow with a placed-based immersive virtual reality game. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 30 (3), 347–360. doi:10.1007/s10956-020-09870-4

Bowman, D. A., and Mcmahan, R. P. (2007). Virtual reality: how much immersion is enough? Computer 40 (7), 36–43. doi:10.1109/MC.2007.257

Breves, P. (2023). Persuasive communication and spatial presence: a systematic literature review and conceptual model. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 47 (2), 222–241. doi:10.1080/23808985.2023.2169952

Caputo, A., and Kargina, M. (2022). A user-friendly method to merge scopus and web of science data during bibliometric analysis. J. Mark. Anal. 10 (1), 82–88. doi:10.1057/s41270-021-00142-7

Caroux, L. (2023). Presence in video games: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of game design choices. Appl. Ergon. 107, 103936. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2022.103936

Chalmers, D. J. (2022). Reality+: virtual worlds and the problems of philosophy. New York, Ny: W. W. Norton and Company.

Chatain, J., Kapur, M., and Sumner, R. (2023). Three perspectives on embodied learning in virtual reality opportunities for interaction design, 23. Hamburg, Germany: CHI EA, 1–8. doi:10.1145/3544549.3585805

Chaurasia, H. K., and Majhi, M. (2022). “Sound design for cinematic virtual reality: a state-of-the-art review,” in Lecture notes in networks and systems. Editors D. Chakrabarti, S. Karmakar, and U. R. Salve (Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH), 357–368. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-94277-9_31

Chen, C., Hu, X., and Fisher, J. T. (2023). “The conceptualization of “presence” in interactive marketing: a systematic review of 30 years of literature,” in The palgrave handbook of interactive marketing. Editor C. L. Wang (Cham: Springer International Publishing). doi:10.1007/978-3-031-14961-0_18

Chirico, A., and Gaggioli, A. (2023). “Virtual reality for awe and imagination,” in Virtual reality in behavioral neuroscience: new insights and methods. doi:10.1007/7854_2023_417

Clark, A., and Chalmers, D. (1998). The extended mind. Anal. Oxf. 58 (1), 7–19. doi:10.1111/1467-8284.00096

Cummings, J. J., and Bailenson, J. N. (2015). How immersive is enough? A meta-analysis of the effect of immersive technology on user presence. Media Psychol. 19 (2), 272–309. doi:10.1080/15213269.2015.1015740

Diemer, J., Alpers, G. W., Peperkorn, H. M., Shiban, Y., and Mühlberger, A. (2015). The impact of perception and presence on emotional reactions: a review of research in virtual reality. Front. Psychol. 6, 26. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00026

Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., and Lim, W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: an overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 133, 285–296. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070

Echchakoui, S. (2020). Why and how to merge scopus and web of science during bibliometric analysis: the case of sales force literature from 1912 to 2019. J. Mark. Anal. 8 (3), 165–184. doi:10.1057/s41270-020-00081-9

Felisatti, A., and Fischer, M. H. (2024). Experimental methods in embodied cognition: how cognitive psychologists approach embodiment. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Felton, W. M., and Jackson, R. E. (2022). Presence: a review. Int. J. Human-Computer Interact. 38 (1), 1–18. doi:10.1080/10447318.2021.1921368

Forster, P.-P., Karimpur, H., and Fiehler, K. (2022). Why we should rethink our approach to embodiment and presence. Front. Virtual Real. 3, 838369. doi:10.3389/frvir.2022.838369

Graf, S., and Schwind, V. (2020). “Inconsistencies of presence questionnaires in virtual reality,” in Proceedings of the 26th ACM symposium on virtual reality software and technology. Canada: Association for Computing Machinery. doi:10.1145/3385956.3422105

Grassini, S., and Laumann, K. (2020). Questionnaire measures and physiological correlates of presence: a systematic review. Front. Psychol. 11, 349. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00349

Hamzah, I., Salwana, E., Billinghurst, M., Baghaei, N., Ahmad, M. N., Rosdi, F., et al. (2023). “Virtual reality for social-emotional learning: a review,” in Advances in Visual informatics: 8th International visual informatics conference, IVIC 2023, Selangor, Malaysia, November 15–17, 2023, proceedings. Editors H. B. Zaman, P. Robinson, A. F. Smeaton, R. L. D. Oliveira, B. N. Jørgensen, T. K. Shihet al. (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.), 119–130. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-7339-2

Hartmann, T., and Hofer, M. (2022). I know it is not real (and that matters) media awareness vs. presence in a parallel processing account of the vr experience. Front. Virtual Real. 3, 694048. doi:10.3389/frvir.2022.694048

Heeter, C. (1992). Being there: the subjective experience of presence. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 1 (2), 262–271. doi:10.1162/pres.1992.1.2.262

Hilty, D. M., Randhawa, K., Maheu, M. M., Mckean, A. J. S., Pantera, R., Mishkind, M. C., et al. (2020). A review of telepresence, virtual reality, and augmented reality applied to clinical care. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 5 (2), 178–205. doi:10.1007/s41347-020-00126-x

Hsu, H. C. K., and Wang, C. (2021). “Assessing the impact of immersive virtual reality on objective learning outcomes based on presence, immersion, and interactivity: a thematic review,” in Learning technologies and user interaction: diversifying implementation in curriculum, instruction, and professional development. New York, NY, United States: Taylor & Francis. doi:10.4324/9781003089704-5

Johnson-Glenberg, M. C., and Megowan-Romanowicz, C. (2017). Embodied science and mixed reality: how gesture and motion capture affect physics education. Cognitive Res. Princ. Implic. 2, 24. doi:10.1186/s41235-017-0060-9

Kelly, N. J., Hallam, J., and Bignell, S. (2024). Using interpretative phenomenological analysis to gain a qualitative understanding of presence in virtual reality. Virtual Real. 28, 1–58. doi:10.1007/s10055-024-00940-1

Krassmann, A. L., Melo, M., Pinto, D., Peixoto, B., Bessa, M., and Bercht, M. (2024). How are the sense of presence and learning outcomes being investigated when using virtual reality? A 24 years systematic literature review. Interact. Learn. Environ. 32 (7), 1–24. doi:10.1080/10494820.2023.2184388

Kraus, S., Breier, M., Lim, W. M., Dabić, M., Kumar, S., Kanbach, D., et al. (2022). Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice. Rev. Manag. Sci. 16 (8), 2577–2595. doi:10.1007/s11846-022-00588-8

Kukshinov, E., Tu, J., Szita, K., Senthil Nathan, K., and Nacke, L. E. (2025). Widespread yet unreliable: a systematic analysis of the use of presence questionnaires. Interact. Comput., iwae064. doi:10.1093/iwc/iwae064

Kumpulainen, M., and Seppänen, M. (2022). Combining web of science and scopus datasets in citation-based literature study. Scientometrics 127 (10), 5613–5631. doi:10.1007/s11192-022-04475-7

Lakoff, G. (2012). Explaining embodied cognition results. Top. Cognitive Sci. 4 (4), 773–785. doi:10.1111/j.1756-8765.2012.01222.x