- 1Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad, India

- 2Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India

- 3St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai, India

Magnetite (Fe3O4), a common byproduct associated with the serpentine deposits, plays a pivotal role in catalyzing prebiotic chemical pathways to produce several important biological precursors relevant to the origin of life. On Mars, serpentine is identified on the Noachian surface, denoting the period of abundant surface water and water-rock interactions. During serpentinization, magnetite commonly forms as a byproduct controlled mainly by Fe-Mg lattice diffusion in olivine, contributing to reducing gases like hydrogen and methane through iron oxidation. This study utilizes selected analog serpentinized sites to investigate the critical role of magnetite in catalyzing and, therefore, facilitating key prebiotic pathways. The various sites are rift settings, obducted settings, plate-margin, and intraplate settings. This helps to understand the probable mineral assemblages associated with magnetite and potential prebiotic pathways in various settings and chemical environments. We discuss here the potential prebiotic pathways like Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis, Water Gas Shift, Haber-Bosch process, role of cyanide in magnetite preservation, and abiotic organic synthesis in the context of magnetite’s role as a potential catalytic surface and mineralogical marker in serpentinization systems. We also explore the potential role of subzero interfacial water films in mediating oxidant decomposition and magnetite-driven redox reactions, highlighting their implications for low-temperature serpentinization and habitability on Mars. This study may advance our understanding in shortlisting the prime targets for prebiotic studies, astrobiological investigations, and Mars sample return missions.

1 Introduction

Magnetite’s cation-deficient sites and surface adsorption properties make it a highly effective catalyst in key prebiotic reaction pathways, facilitating the formation of essential biomolecules (Samulewski et al., 2020). Studies suggest that these properties support prebiotic chemistry, with RNA-like precursors crystallizing on magnetite surfaces, potentially playing a role in the emergence of biological homochirality (Ozturk et al., 2023). In serpentinized environments, magnetite may catalyze abiotic organic synthesis, including amino acids, lipids, nucleosides, and sugars (Holm and Charlou, 2001; Schwander et al., 2023).

Serpentinization, a water-mediated alteration process of olivine- and pyroxene-rich rocks, is crucial in shaping planetary environments and fostering habitability. On Earth, this process has been integral to the long-term evolution of surface conditions (Evans, 2004). Similarly, on Mars, serpentinization is proposed to have significantly influenced its early climate by contributing to warm conditions (Ramirez et al., 2014; Wordsworth et al., 2017; 2021) and controlling the planet’s hydrological and geochemical cycles (Schulte et al., 2006). NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) identified the presence of serpentine in association with olivine-rich units within the mélange terrains of Nili Fossae and Claritas Rise (Ehlmann et al., 2010; Viviano et al., 2013). Additional occurrences of serpentine have also been detected in various regions across the Martian surface (Ehlmann et al., 2010; Viviano et al., 2013; Amador et al., 2018). The widespread distribution of olivine on Mars (Evans, 2004) and its high reactivity in aqueous conditions (Oze and Sharma, 2005) suggest that serpentinization could have occurred extensively during interactions between liquid water and the mafic crust (Oze and Sharma, 2005; Schulte et al., 2006). On Mars, serpentinization has the potential to form serpentine minerals while creating chemically distinct subsurface environments characterized by high pH, reducing conditions, and low silica activity (Evans, 2004; Tutolo and Tosca, 2023). This process may also produce molecular hydrogen (H2), which could serve as an energy source for hypothetical chemosynthetic life. Furthermore, under suitable conditions, serpentinization might drive abiotic methane production through reactions between hydrogen and carbon dioxide—both of which have been detected on Mars (Kelley et al., 2005; Russell et al., 2010; Amador et al., 2018; Kakkassery et al., 2022).

Depending on fluid geochemistry during serpentinization, magnetite (Fe3O4) commonly forms as a byproduct, contributing to hydrogen (H2) production through iron (Fe) oxidation in serpentine (Andreani et al., 2013; Klein et al., 2014). The detection of magnetite on Mars is challenging due to its near-infrared opacity, making it undetectable by hyperspectral instruments such as CRISM (Ehlmann et al., 2010). Strong magnetic fields have been detected from orbit over Mars’ ancient southern highlands and at the InSight landing site, though the processes behind this magnetization remain uncertain (Nazarova and Harrison, 2000; Lillis et al., 2008; Ehlmann et al., 2010; Bultel et al., 2025). One hypothesis suggests that serpentinization generated magnetite, which was magnetized by an ancient global magnetic field (Bultel et al., 2025). Thermodynamic modeling indicates that, while serpentinization occurs, dunitic protolith composition could generate up to 6 wt% magnetite owing to its proneness to dissolution through aqueous alteration, explaining strong magnetic anomalies (Bultel et al., 2025). In contrast, basaltic compositions require high water-to-rock ratios to produce more than 0.4 wt% magnetite, aligning with weaker magnetizations at the landing site of the InSight (Bultel et al., 2025).

At some handful of locations, serpentines occur on the Martian surface, and orbiter observations do not allow for the identification of serpentine polymorphs (Ehlmann et al., 2010), which necessitates terrestrial analog studies to gain insights into the water-rock interactions in the Martian distant past. This study investigates the critical role of magnetite in facilitating key prebiotic pathways, including Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis (FTS), Water-Gas Shift (WGS) reaction, and ammonia production via the Haber-Bosch process. This study further facilitates comparisons among different formation conditions of magnetites in terrestrial serpentinized sites like the Duluth Complex of Minnesota USA, Samail Ophiolites of Oman, and the serpentine-rich sites in Sri Lanka (Figure 1). Understanding the possibility of such pathways could help us to identify and shortlist prime sites for prebiotic chemistry research and astrobiological exploration, especially given that Mars missions such as Viking, Phoenix, Curiosity, and Perseverance have observed preserved organics (Ansari, 2023). In this context, ESA’s ExoMars mission not only prioritizes the search for organics but also specifically targets the subsurface, where organic molecules and potential biomarkers are better preserved (Altieri et al., 2023).

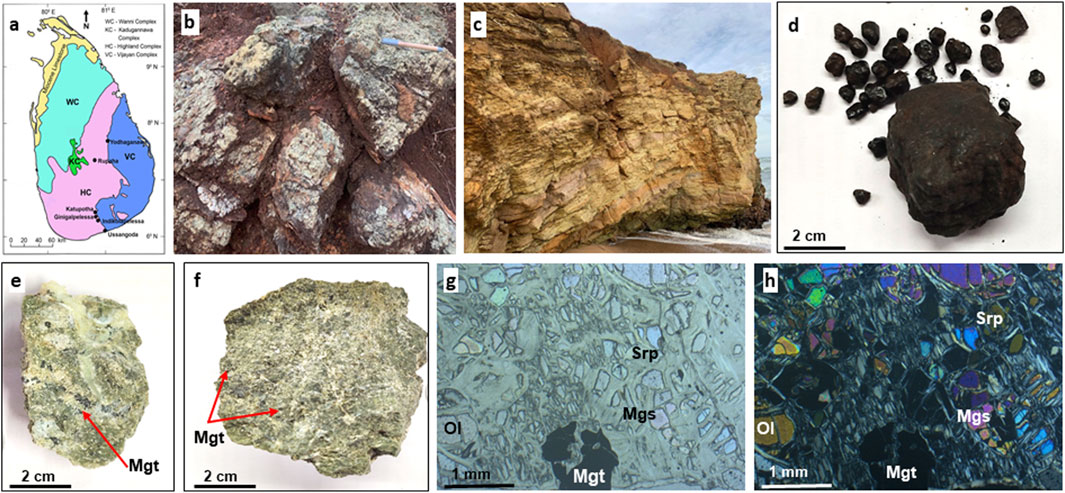

Figure 1. (a) Serpentinite deposits in Sri Lanka along with the tectonic boundaries (modified after Dilshara et al., 2025); (b) Highly weathered serpentinite deposits in the Ginigalpelessa region are characterized by the red color of the sand, which indicates significant leaching of iron from the serpentinite; (c) A layered serpentinite outcrop on the coastal cliff of Ussangoda; (d) Iron (Fe) concretions from serpentinite soil in the Ginigalpelessa region; (e) Serpentinite sample from Ussangoda with magnetite (Mgt) marked; (f) Serpentinite sample from Ginigalpelessa showing magnetite (Mgt). Photomicrographs of serpentinite collected from Ginigalpelessa, showing serpentine (Srp), magnetite (Mgt), and magnesite (Mgs) minerals with characteristic mesh texture of olivine (Ol) using a polarization microscope: (g) viewed under plane-polarized light, and (h) the same field of view under crossed polar.

2 Formation of serpentine-magnetite assemblage on the surface of Mars

The reaction of forsterite and fayalite with CO2 and water leads to the formation of serpentine, magnetite, and methane (R1), underscoring the role of serpentinization as a fundamental process in Mars’ aqueous history and geochemical evolution (Ehlmann et al., 2010; Viviano et al., 2013; Amador et al., 2018; Kakkassery et al., 2022). Additionally, under low-temperature, CO2-rich Martian conditions, magnetite can form through the oxidation of Fe2+-bearing brucite, releasing molecular hydrogen (R2) (Beard et al., 2009; Templeton et al., 2021). The Fe2+-Fe3+ redox transformation, driven by water-rock interactions, has been identified as a key mechanism in Martian serpentinization (McCollom and Bach, 2009; Mustard et al., 2009), with experimental studies demonstrating its viability under low oxygen fugacity and alkaline conditions (Frost et al., 2013; Klein et al., 2014).

The formation of magnetite during serpentinization is controlled mainly by Fe-Mg lattice diffusion in olivine, which varies with temperature (Evans, 2010; Müntener, 2010). At low temperatures (<300 °C), sluggish Fe-Mg diffusion leads to the formation of serpentine, magnetite, molecular hydrogen, and occasionally brucite and Fe-Ni-Co alloys. Ferric iron is primarily stored in magnetite and some in lizardite (an Mg-rich serpentine) at 100–200 °C (Evans, 2010). The Mg-rich nature of serpentine plays a key role in magnetite production at these temperatures. In contrast, at higher temperatures (>400 °C), Fe-Mg diffusion accelerates, and above ∼600 °C, thermodynamic equilibrium is reached, prompting olivine to be fayalitic and lower its magnesium number (Mg# = molar Mg/(Mg + Fe) ×100) (Evans, 2010). At temperatures above 400 °C, antigorite becomes the stable serpentine phase and begins incorporating ferric iron, which reduces the availability of Fe3+ for magnetite formation. As a result, magnetite is less likely to be part of the stable mineral assemblage at higher temperatures (Evans, 2010; Müntener, 2010).

3 Geochemical factors driving magnetite formation in terrestrial analog sites

Magnetite forms during serpentinization as Fe2+ from olivine or pyroxene oxidizes, generating hydrogen under reducing conditions. Its stability is enhanced in low-silica, alkaline environments but suppressed in high-silica settings, where Fe-bearing serpentine dominates (Evans, 2010; Klein et al., 2014). Optimal formation of magnetite occurs below ∼300 °C, while higher temperatures (400–600 °C) promote Fe-Mg diffusion, limiting magnetite formation (Evans, 2010; Müntener, 2010). To better understand the geochemical controls, this study examines three well recognized terrestrial serpentine analog sites (Table 1): Duluth Complex’s ferrous acidic environment in rift settings (Evans et al., 2017; Tutolo and Tosca, 2023), Samail ophiolite’s variable fluid interactions at obducted settings (Seyfried et al., 2007; McCollom and Bach, 2009; Bonnemains et al., 2016), and Sri Lanka’s Mg-rich chemical composition in plate-margin to intraplate settings (He et al., 2016; Fernando et al., 2017; Malaviarachchi et al., 2024; Nair et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024) — each representing distinct serpentinization conditions.

Duluth Complex, emplaced during the mid-continent rift magmatism (1,109–1,084 Ma), consists of layered mafic and ultramafic lithologies through multiple intrusive events. The complex consists of tholeiitic basalt with FeO and MgO concentrations consistent with Martian meteorites, reinforcing its relevance as an Earth-based analog (Tutolo and Tosca, 2023). In the layered peridotite samples, the serpentine formed from Fe-rich olivine (Fa38-43) shows notable Fe enrichment, reaching at least 30% of the Fe end member composition. This site offers valuable insights into the formation of Fe-rich serpentinite and magnetite, both of which are closely linked to the hydration of Fe-rich olivine and Fe2+/Mg2+ exchange under conditions of low oxygen fugacity (Evans, 2008; Evans et al., 2017). In some cases, this alteration is accompanied by the formation of hisingerite [3Fe3+2Si2O5(OH)4], a Fe-rich phyllosilicate that forms through the oxidation of Fe and mobilization of silica in acidic conditions (Evans et al., 2017; Tutolo and Tosca, 2023). Around 300 °C, magnetite may also form alongside Mg-rich serpentine (e.g., lizardite) in some part of the Duluth complex, as acidic aqueous fluids promote Mg leaching, thereby increasing the Fe/Mg ratio in the alteration assemblage to form magnetite (Evans, 2008). The co-occurrence of hisingerite, magnetite, and Fe-enriched serpentine under acidic fluid conditions highlights the critical role of fluid chemistry in controlling serpentinization and associated magnetite formation and offers key analogs for understanding similar processes that may have influenced the evolution of the Martian crust.

Samail ophiolites represent a thrust sheet of oceanic crust and upper mantle emplaced onto the Arabian continental margin during Late Cretaceous time (96–94 Ma) (Mayhew et al., 2018). Therefore, Samail provides a key example location of low-temperature serpentinization and Fe transformation aided by varying Fe incorporation and Fe mobility due to the extent of alteration and fluid chemistry (Sleep et al., 2004; McCollom and Bach, 2009; Klein et al., 2014; Mayhew et al., 2018). Samail peridotites are predominantly harzburgites (∼90%; Mg# 92) and dunites (∼10%; Mg# 92), occurring as isolated lenses (Godard et al., 2000; Monnier et al., 2006; Hanghøj et al., 2010), and all outcrop samples exhibit varying degrees of alteration, ranging from partial serpentinization (∼30–60%) to complete serpentinization and carbonation (Hanghøj et al., 2010; Streit et al., 2012; Kelemen et al., 2013; Falk and Kelemen, 2015). Previous studies suggest that low-temperature alteration of the Samail ophiolite begins with the formation of Mg2+–HCO3− rich fluids, as atmospheric CO2-bearing rainwater causes significant Mg leaching from peridotites during near-surface weathering (Fones et al., 2019; de Obeso et al., 2021). As a result, the less altered peridotites converted to a diverse assemblage of Fe-enriched olivine and pyroxene along with chromite and secondary alteration phases (Fe-serpentine and Fe-brucite). Fe oxidation in serpentine (Fe2+ to Fe3+) (Cooperdock et al., 2020) and potential for Fe3+ substitution in magnetite in these less altered rocks suggest that magnetite formation could occur under high temperature conditions (>200 °C) or during episodic fluid interaction with less silica activity (Andreani et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2016), creating localized magnetite-rich zones in Samail. In contrast, low-temperature serpentinization took place in the highly altered rocks, which display a simplified mineralogy dominated by Fe3+-bearing serpentine and carbonate, with the notable absence of olivine, brucite, and magnetite (Streit et al., 2012; Mayhew et al., 2018). Even in the absence of magnetite, completely serpentinized rocks have the potential to generate H2, as evidenced by measurements in hyperalkaline subsurface and spring waters in Samail, which is commonly attributed to the incorporation of Fe3+ into serpentine or other Fe-bearing phases such as hematite (Andreani et al., 2013; Klein et al., 2014; Bonnemains et al., 2016; Mayhew et al., 2018).

Sri Lanka’s serpentinite bodies (Figure 1), particularly in Ussangoda, Indikolapelessa, and Ginigalpelessa, mark a subduction zone boundary (He et al., 2016; Nair et al., 2024). In contrast, the Rupaha serpentinite body of Sri Lanka occurs away from the tectonic boundary within the intraplate settings of the highland complex (Fernando et al., 2017; Nair et al., 2024). These altered ultramafic rocks, formed through the hydration of peridotite and pyroxenite, exhibit Mg# variations 91–93 along the convergent margin and 98–99 in the Rupaha region (Fernando et al., 2013; 2017; Nair et al., 2024). The increase in Mg# of serpentinite away from the tectonic boundary is notable and may indicate differing protolith compositions or fluid interactions. In the Rupaha region, the dunitic protolith (Mg# 98–99) lacks significant Fe content, and serpentinization occurs under high SiO2 activity, which is likely sourced from surrounding granulite leaching (Fernando et al., 2013). This elevated silica activity, along with the Fe-poor protolith, may stabilize serpentine minerals while preventing magnetite formation by inhibiting Fe oxidation governed by the serpentinization reaction, R3. In contrast, the relatively Fe-rich sites near the tectonic boundary show that magnetite is one of the major associated minerals, especially in Ginigalpelessa (Kumarathilaka et al., 2014) and Ussangoda (Rajapaksha et al., 2012). Our preliminary observations on the serpentinite samples from these locations reveal the presence of magnetite as an associated phase (Figures 1d–f), with the thin section of the Ginigalpelessa rocks showing a clear association of magnetite with serpentine and magnesite, along with a characteristic olivine mesh texture (Figures 1g,h). While many Martian analog studies focus on ophiolitic serpentinization, the Sri Lanka serpentinites serve as an excellent analog for Mg-rich ultramafic protolith, providing insights into alternative serpentinization processes at the subduction settings and intraplate settings.

Hereafter, we discuss the variable abundances of magnetite in the terrestrial analog serpentinization settings to gain insight into the key prebiotic reaction pathways and the formation scenarios of essential biomolecules.

4 Potential catalytic roles of magnetite in abiotic organic synthesis across analog sites

Given the distinct serpentinization across the sites of interest, it becomes evident that the variation among Fe/Mg ratio, silica activity, and temperature has influenced the magnetite’s abundance and associated redox transitions (McCollom and Bach, 2009; Mayhew and Ellison, 2020; Preiner et al., 2020). These parameters not only control mineral assemblages but also help in defining potential prebiotic pathways. In Fe-dominant systems like Duluth, acidic fluids and optimal thermal conditions make it ideal for extensive Fe2+ oxidation, producing abundant magnetite and molecular hydrogen, a potent combination for driving abiotic organic synthesis pathways such as FTS reactions (Papineau and Du, 2025). In the case of Samail, the varying alkaline to hyperalkaline fluid-rock interactions may create episodic and localized zones of magnetite formation, particularly under deep subsurface conditions where extensive olivine hydration and Fe2+ oxidation produce redox-active phases such as magnetite and hydrogen, which can act as key catalysts for abiotic reactions (Fones et al., 2019; Leong and Shock, 2020). When such fluids mix with shallow, carbonate- and dissolved inorganic carbon like CO2(aq), HCO3−, CO32− rich waters, they can establish strong redox gradients and chemical disequilibria, further enhancing localized catalytic activity of magnetite and enabling transient zones of prebiotic reactions (Fones et al., 2019; de Obeso and Kelemen, 2020). The Sri Lankan serpentinites formed from relatively Mg-dominant protoliths, where iron is predominantly locked in the silicate or spinel phases. This limits the availability of Fe for redox reactions and suppressing magnetite formation, potentially shifting the system toward alternative catalytic regimes involving Mg-bearing phases or silica-mediated processes (Wang et al., 2024). Notably, the occurrence of round ferruginous concretions in the Ginigalpelessa serpentinite soils (Figure 1d), which closely resemble the Fe-oxide concretions observed at the Utah analog site (Yoshida et al., 2018) and offers a valuable opportunity to investigate similar diagenetic processes that may have occurred on Mars. These Fe-oxide concretions can provide insights into redox-driven fluid interactions and potential biogeochemical pathways involved in their formation, thereby shedding light on past aqueous conditions. Such terrestrial analogs are particularly important for understanding the origin, mineralogy, and habitability implications of hematite-rich features detected on Mars through orbital and rover-based observations (Squyres et al., 2004). Fe-oxide concretions, especially in soils derived from weathered serpentinites, are compelling from both prebiotic chemistry and astrobiological perspectives. Their redox-driven formation, specifically the oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ and the precipitation of Fe-oxides such as magnetite, results in the release of H2, a potent electron donor in early Earth systems (Yoshida et al., 2018). These redox and geochemical gradients can drive key abiotic reactions, including Fischer-Tropsch-type (FTT) synthesis and Haber-Bosch-type reactions, enabling the production of prebiotic compounds such as formate, glycine, and ammonia (Preiner et al., 2018). Additionally, the serpentinization process is thought to have contributed to early biochemical pathways—such as methanogenesis, CO2 fixation, and N2 reduction—through the generation of native metals (Ni0, Fe0) and inorganic catalysts that likely preceded biological enzymes like carbon monoxide dehydrogenase and nitrogenase (Preiner et al., 2018).

4.1 Fischer-Tropsch synthesis and water gas shift processes

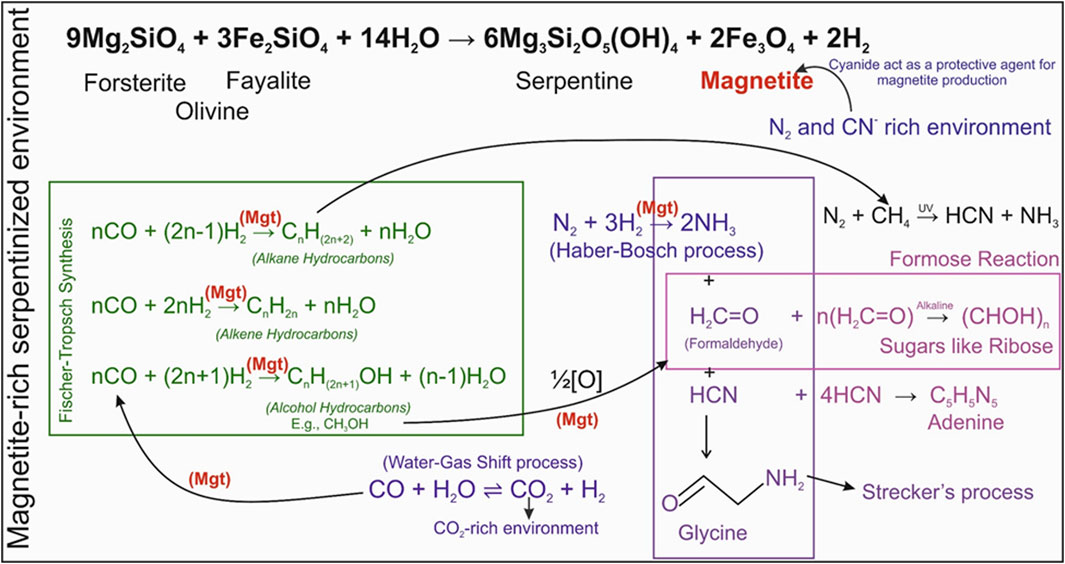

On the early Earth, serpentinization-driven hydrothermal systems created environments enriched with H2 and CO2, essential precursors for abiotic organic synthesis. These conditions closely resemble modern industrial Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis (FTS) processes (R5), where syngas (CO and H2) is converted into hydrocarbons (Lang et al., 2010; Preiner et al., 2018; Barbier et al., 2020; Papineau and Du, 2025). The FTS processes are further supported by the release of CO2 from the Water Gas Shift (WGS) reaction (R4), making the environment CO2-rich, which is ideal for FTS reactions. Magnetite, a key byproduct of serpentinization, emerged as a natural heterogeneous catalyst, playing a pivotal role in these reactions as shown in Figure 2. Studies highlight that cation-deficient sites on magnetite surfaces facilitate the adsorption and activation of reactants like CO and H2O, stabilize intermediates and transition states, and enable efficient electron transfer (Bach et al., 2006; Santos-Carballal et al., 2018). Hence, the magnetite’s catalytic ability drives the reduction of CO and H2 into hydrocarbons while supporting the WGS process (R4) (Hla et al., 2010).

Figure 2. Schematic representation of prebiotic chemical pathways in serpentine-rich environments. The interaction of olivine with water during serpentinization results in the formation of serpentine and magnetite (Mgt), along with the release of molecular hydrogen (H2). Magnetite functions as a key catalyst in several prebiotic reactions, including Fischer–Tropsch-type (FTS) synthesis (producing hydrocarbons and alcohols), the water–gas shift (WGS) reaction, and ammonia synthesis via a prebiotic analogue of the Haber–Bosch process. Experimental studies have shown that magnetite can facilitate abiotic hydrocarbon formation through FTS reactions under serpentinized conditions (Chen and Bahnemann, 2000; Holm and Charlou, 2001). Partial oxidation of formaldehyde from methanol on the magnetite surface is shown by Li and Paier (2019). Although methane (CH4) and other simple hydrocarbons are the predominant FTS products, these compounds can serve as feedstocks for the synthesis of more complex organics (Rushdi and Simoneit, 2001; McCollom and Seewald, 2007; Omran et al., 2023). Additionally, related downstream pathways involving formaldehyde and hydrogen cyanide have been further explained in detail by Kovalenko (2020).

Temperature variation across the Duluth, Samail, and Sri Lankan serpentinized regions directly impacts the magnetite-driven R4 and R5 synergic reactions. The temperature range (200–400 °C) for Duluth Complex enables extensive Fe2+ oxidation and magnetite formation, supporting both WGS and FTS reactions (McCollom and Seewald, 2007). Higher temperatures (∼300–350 °C) favor the formation of short-chain hydrocarbons such as methane and light olefins, while cooler zones (∼200–250 °C) may facilitate the formation of longer-chain hydrocarbons. While such compounds could potentially serve as precursors to more complex organics, including those relevant to membrane formation, the extent to which these abiotic processes contribute to biologically significant molecules in natural serpentinization systems remains an open question and an active area of research investigation (McCollom and Seewald, 2007; Gholami et al., 2022). In contrast, the Samail ophiolite exhibits localized serpentinization between <100 °C and ∼200 °C, with variable fluid-rock interactions and limited magnetite formation, thus offering a narrower window for hydrocarbon synthesis (Bach et al., 2006; Hla et al., 2010). Sri Lankan serpentinites exhibit a notable gradient in serpentinization conditions. Rupaha, away from active tectonic settings, shows limited magnetite production and antigorite formation at relatively high (200–400 °C) temperatures (Fernando et al., 2017). This thermal regime restricts the potential for complex hydrocarbon synthesis. In contrast, other sites located along the tectonic contact between the Vijayan Complex (VC) and Highland Complex (HC) have a lower Mg# compared to Rupaha, yet still support antigorite formation (Wang et al., 2024). These tectonically influenced sites also contain some magnetite as minor phases, less than that observed in the Duluth Complex, making them more favorable for supporting catalyst-mediated prebiotic pathways, even if the potential for hydrocarbon formation remains limited.

4.2 Magnetite as a driving force for the Haber-Bosch process

Ammonia (NH3) is a key precursor for amino acids and nucleotides, both essential for the origin of life. Magnetite-rich environments share similarities with the catalytic conditions of the Haber-Bosch process by acting as both an electron transfer mediator and a surface catalyst (Liu, 2013; Gao et al., 2025). Such environments may have provided localized conditions favorable for abiotic ammonia synthesis. The presence of NH3 and its ionized form, NH4+, may have high relevancy for prebiotic organic synthesis, further showing the significance of these reactions in the early Earth’s chemistry (Hennet et al., 1992; Smirnov et al., 2008). Reactions such as reductive amination (Afanasyev et al., 2019) and the Strecker synthesis, which produce amino acids, depend on NH3 availability (Hennet et al., 1992; Smirnov et al., 2008). In reductive amination, carbonyl compounds (e.g., pyruvic acid) react with NH3 to form amino acids. Meanwhile, the Strecker synthesis involves NH3, cyanide, and aldehydes or ketones (products of FTS process) to produce α-aminonitriles, which are hydrolyzed to amino acids like glycine as shown in Figure 2 (Gröger, 2003; Afanasyev et al., 2019).

Studies suggest that magnetite surfaces can enhance the catalytic reduction of N2 to NH3 under certain conditions (Liu, 2013; Gao et al., 2025), although the extent of this process under natural prebiotic conditions remains an open question. Abundancy of N2 is primarily required to be present in the environment along with CO2, where N2 can actively react with H2 formed from serpentinization and the WGS process (Figure 2). Studies highlight the broader relevance of magnetite-catalyzed NH3 synthesis in a planetary context conducive to abiotic organic synthesis and the search for prebiotic pathways beyond Earth (Barge et al., 2022; Gao et al., 2025). Magnetite has also been hypothesized to be involved in nitrogen fixation on Mars, forming NH3 and other nitrogenous compounds in the ancient hydrothermal systems (Summers and Khare, 2007; Fornaro et al., 2018). This further gives a deeper reason to investigate magnetite-mediated prebiotic pathways at the Martian analog sites.

4.3 Cyanide preservation and abiotic organic synthesis

Cyanide (−CN), abundant in certain prebiotic environments, likely played a dual role as both a reactant and a preservative in magnetite-dominant early Earth and potential Martian environments. Its abundance was supported by hydrothermal serpentinization, volcanic outgassing, and atmospheric photochemistry driven by UV radiation or electric discharges (Segura and Navarro-González, 2005; Ferus et al., 2017). In reducing conditions of mafic and ultramafic rock systems, serpentinization produced hydrogen (H2), methane (CH4), and Fe-rich magnetite, the key precursors for cyanide synthesis from nitrogen species (Hara, 2023).

Magnetite formed through serpentinization processes can be selectively stabilized and preserved in the presence of cyanide. Experimental studies demonstrate that cyanide prevents the transformation of Fe2+ into competing mineral phases such as goethite and ferrihydrite by stabilizing ferrous ions in solution, thereby promoting the crystallization of pure magnetite (Samulewski et al., 2020). Cyanide does not significantly adsorb onto magnetite surfaces or get consumed during synthesis, indicating that it plays a modulatory role in directing mineral pathways rather than acting as a reactant. These findings suggest that cyanide-rich niches on the early Earth may have not only supported magnetite synthesis during serpentinization but also helped preserve mineral phases favorable for catalytic processes, though long-term catalytic activity under natural prebiotic conditions remains to be fully demonstrated.

Furthermore, the abiotic formation of nucleobases and sugars are thermodynamically feasible under specific hydrothermal conditions, particularly when precursor molecules such as formaldehyde and HCN are present (Kovalenko, 2020). A detailed illustration of the possible reaction pathways has been demonstrated by Kovalenko (2020). In context of adsorption on magnetite, cyanide plays a dual role: it not only stabilizes magnetite surfaces but also catalyzes complex organic reactions, highlighting its significance as a key molecule in prebiotic chemistry (Oró, 1961; Hara and Templeton, 2024). Among nucleobases, purines (e.g., adenine) are more readily synthesized and tend to adsorb more efficiently on mineral surfaces compared to pyrimidines, whose formation is comparatively limited in prebiotic settings.

5 Preservation potential of magnetite and a potent chemical factory for astrobiological research

Magnetite serves as both a catalytic surface and a mineralogical marker of past redox activity, underscoring its significance in astrobiological studies of serpentinization systems. Its frequent association with reducing environments, where hydrogen (H2) and methane (CH4) are the key byproducts of serpentinization, makes it a valuable indicator of geochemical conditions that may support prebiotic chemistry and potentially, life. The mixed valence states of magnetite (Fe2+/Fe3+) contribute to redox-active conditions that could support microbial metabolism in extraterrestrial settings. A study by Mitra et al. (2024) indicates that magnetite exhibits a high resistance to oxidative weathering in Mars-relevant fluids, even in the presence of strong oxidants like oxy-halogen brines. Their results demonstrate that these brines effectively produce non-stoichiometric magnetite with lattice parameters similar to those observed at Gale crater. This suggests that magnetite has a low reactivity compared to other Fe2+-bearing minerals, such as sulfides, highlighting magnetite’s stability and it’s potential for long-term preservation on Mars. Consequently, magnetite remains an essential target for geochemical, paleomagnetic, and astrobiological studies in the Mars sample return missions (Mitra et al., 2024).

The significance of magnetite has been highly debated in many celestial bodies. For instance, the detection of magnetite in Martian meteorites, such as ALH84001, has been a subject of debate, with some attributing its origin to biological activity and others to abiotic mechanisms like thermal metamorphism (Taylor et al., 2001; Shen et al., 2023). Hence, detecting preserved magnetite and serpentinization by-products may point to environments where catalytic processes such as Fischer-Tropsch-type synthesis, nitrogen reduction, or Strecker-type reactions could have occurred under prebiotic conditions. In this context, magnetite-rich regions such as the Duluth Complex and specific localities at the Samail ophiolite zones represent promising sites for studying prebiotic organic synthesis relevant to the origins of life and astrobiological exploration. Furthermore, detailed investigations into the serpentinized ultramafic rocks of Sri Lanka may uncover alternative prebiotic pathways. Such research conducted at terrestrial analog sites could shed light on microbe-mineral interactions relevant to astrobiology and planetary habitability studies. These studies collectively advance our understanding of life’s emergence, adaptability, and sustainability beyond Earth as well as on early Earth.

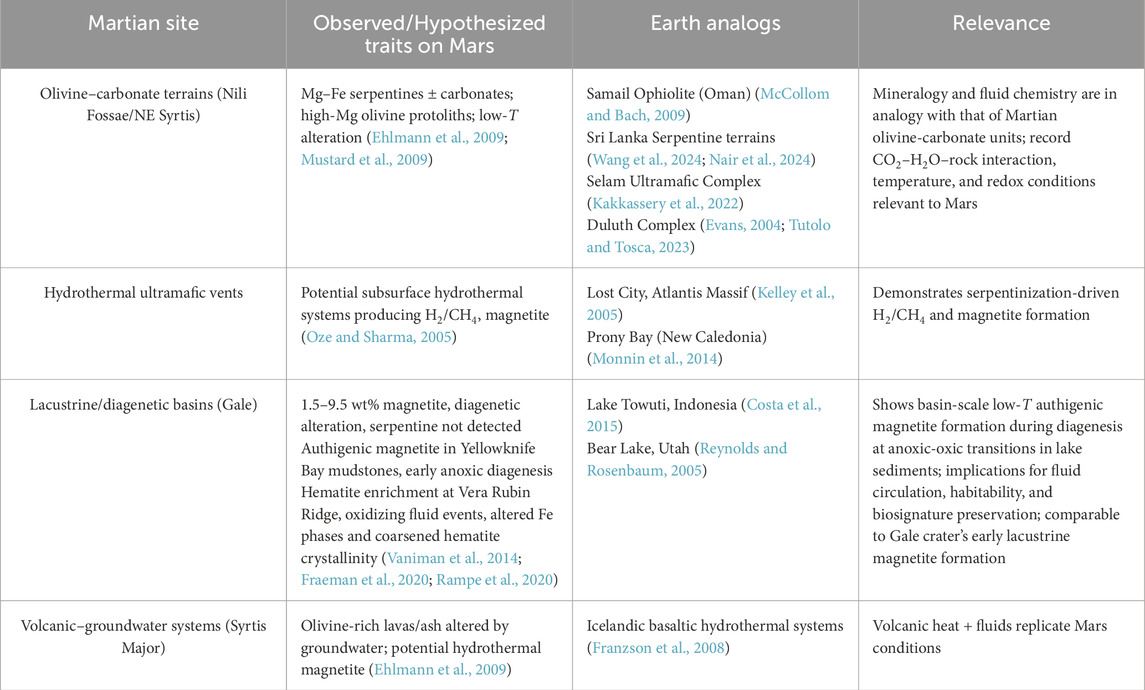

In addition to the examples discussed above, submarine hydrothermal systems such as the Lost City hydrothermal field on Atlantis Massif demonstrate magnetite generation through Fe(II) oxidation, closely coupled to H2 and CH4 fluxes, making them highly relevant to Martian hydrothermal provinces (Kelley et al., 2001; Proskurowski et al., 2008). Shallow marine alkaline systems such as Prony Bay of New Caledonia (Monnin et al., 2014), along with continental alkaline springs including The Cedars of California (Morrill et al., 2013), Hakuba Happo of Japan (Suda et al., 2022), and the Tablelands of Newfoundland (Brazelton et al., 2012) serve as important low-temperature analogs for surface or lacustrine serpentinization on Mars. Extensive magnetite formation in the Samail ophiolite (Kelemen and Matter, 2008; Beinlich et al., 2020) provides insights into large-scale crustal serpentinization that may approximate ultramafic provinces in Martian volcanic terrains. Table 1 summarizes key Martian environments where magnetite formation has been identified, both in association with and independent of serpentinization, and presents comparable terrestrial analog sites for each setting.

6 Potential role of sub-zero interfacial water in Martian serpentinization

Although the role of subzero temperature in serpentinization on Mars is poorly understood, it is worth noting that the microscopic thin liquid water films, also known as interfacial water, potentially persist in temperatures below 0 °C due to its ability to exist between solid surface and air/ice, leading to host localized chemical reactions (Kossacki and Markiewicz, 2010; Kereszturi and Góbi, 2014; Scheller et al., 2022). Within such films, strong oxidants like H2O2 have not been directly detected in the Martian surface materials, although it has been detected in the Martian atmosphere and is a suspected component of the highly oxidizing surface soil and atmosphere (Encrenaz et al., 2004; Aoki et al., 2011). The oxidants can decompose into water and oxygen, altering local redox conditions (Encrenaz et al., 2004; Aoki et al., 2011). The generated oxygen (O2) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) can accelerate Fe2+ oxidation during serpentinization, with catalysts such as magnetite and hematite enhancing the decomposition process. While this may influence the rate of magnetite formation, high oxidant levels could reduce net H2 production, whereas moderate oxidant levels may still allow hydrogen generation and create redox gradients that provide chemical energy for hypothetical microbial life (Molamahmood et al., 2022).

In recent batch reactor experiments and thermodynamic modeling demonstrated by Geymond et al. (2023), magnetite itself can act as a low-temperature H2 source. Traditionally viewed only as a by-product and catalyst of serpentinization, magnetite (α-Fe3O4) has now been shown to generate measurable H2 during interaction with water at <200 °C, while partially converting to maghemite (γ-Fe2O3). These results reveal that magnetite-rich lithologies, such as banded iron formations (BIFs), can sustain natural hydrogen emissions at near-ambient temperatures (Geymond et al., 2023). This dual behavior (direct hydrogen release and catalytic decomposition of H2O2) positions magnetite as a potential mineral in regulating Martian redox chemistry (Geymond et al., 2023).

Laboratory studies by Molamahmood et al. (2022) confirm that H2O2 decomposition is strongly surface-driven. Among iron oxides, magnetite and maghemite are particularly active for both H2O2 breakdown and O2 release under neutral to basic conditions. These results suggest that the specific mineralogy of Martian surfaces could determine whether interfacial H2O2 decomposition favors ROS-driven Fe2+ oxidation or O2 release, thereby modulating hydrogen yields during serpentinization where meteoritic and possibly indigenous organics are present. Moreover, the study emphasizes that trace organic compounds suppress O2 release by more than 60%, thereby increasing the efficiency of ROS pathways. On Mars, where meteoritic and possibly indigenous organics are present, this suppression may enhance magnetite-mediated ROS chemistry in interfacial films without eliminating H2 generation (Kereszturi and Góbi, 2014; Lasne et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2019; Molamahmood et al., 2022). The effect of H2O2 decomposition in thin films that can modulate the chemical environment is described below:

• High H2O2 decomposition → high oxidation → less H2 available → less energy for microbes

• Moderate H2O2 decomposition → O2 released → potential electron acceptor for life

Also, the kinetic models and laboratory studies have already demonstrated that thin films can mediate significant geochemical transformations under Martian conditions. For example, decomposition of oxidants such as H2O2 within such films has been shown to proceed more efficiently in the presence of Fe catalysts (Kereszturi and Góbi, 2014), while no study has directly demonstrated that interfacial H2O2 films control magnetite production during serpentinization. Multiple lines of evidence suggest a plausible coupled reactions. Sub-zero interfacial films on Mars can catalyze H2O2 decomposition on mineral surfaces, especially on magnetite in a serpentine setting. This convergence motivates targeted experiments under Mars-relevant temperatures, humidity, and Fe-silicate substrates to test whether interfacial H2O2 accelerates or redirects Fe partitioning toward magnetite. Also, the cryogenic experiments and modeling indicate that sulfate formation from volcanic SO2 interacting with sub-zero films could explain surface sulfate deposits without the need for large bodies of liquid water (Niles et al., 2017; Góbi and Kereszturi, 2019).

Moreover, similar processes in principle can support low-temperature serpentinization. Although typically associated with bulk liquid water at higher temperatures, serpentinization reactions may still occur in the presence of nm- to µm-scale aqueous films at ultramafic surfaces, particularly at subsurface rock–ice interfaces (Vance et al., 2007; Scheller et al., 2022). A useful analog comes from outer solar system bodies: thermal models of Kuiper belt objects that suggest serpentinization can proceed within cryogenic aqueous phases, even below the melting point of ice, and may significantly affect thermal evolution through self-heating feedbacks (Vance et al., 2007; Farkas-Takács et al., 2022). Further, terrestrial thin-film analogs demonstrated how micrometer-thick amorphous silicate films interacting with water developed hydrated Fe-rich layers with H2 (Le Guillou et al., 2015). This shows that alteration and redox reactions can occur at nanoscale interfaces (Le Guillou et al., 2015). Similarly, Lamadrid et al. (2017) used olivine micro-reactors with fluid inclusions to reveal that reduced water activity, an analog to thin-film environments, significantly slows the serpentinization rates. These findings demonstrate that nm- to µm-scale aqueous films, though water-limited, can sustain serpentinization-related chemistry even on cold Mars, under conditions unfavorable to bulk liquid water (Lamadrid et al., 2017).

As a result, these studies highlight the importance of magnetite-bearing serpentinization sites as not only catalytic environments for prebiotic reactions but also as promising targets for future experimental work. Investigating whether microscopic subzero liquid films can drive serpentinization and magnetite formation under Mars-relevant conditions would represent a critical step in evaluating the astrobiological potential of such environments.

7 Conclusion

Serpentinization and magnetite formation together define some of the most chemically dynamic environments on Earth and Mars, linking mineralogical transformations with catalytic processes essential to prebiotic chemistry. The stability, redox activity, and catalytic potential of magnetite make it a critical mineralogical marker for evaluating past and present habitability. Terrestrial analog studies from hydrothermal systems and ophiolitic complexes to cryogenic thin-film environments demonstrate the multiple pathways by which magnetite can regulate hydrogen fluxes, redox gradients, and organic synthesis. On Mars, the persistence of magnetite in oxidizing conditions and its association with serpentinization underscores its value as a priority target for orbital, rover, and eventual sample return investigations. To advance our understanding of serpentinization and magnetite formation on Mars, future investigations should prioritize high-resolution mineralogical characterization of serpentine–magnetite assemblages through orbital and rover-based spectroscopy, with particular emphasis on discriminating Mg- versus Fe-rich variants. These mineralogical studies need to be integrated with isotopic and isotopologue analyses (Fe, H, C) to disentangle abiotic and potential biotic contributions to H2 and CH4 production. Accessing alteration fronts through deep drilling into olivine-rich crustal sections, as exemplified by the Oman Drilling Project, will be critical for reconstructing reaction pathways. Parallel investigations at terrestrial analog sites, combining geochemistry and microbiology, will provide essential insights into the catalytic and habitability roles of magnetite. Furthermore, experimental studies conducted under Mars-relevant cryogenic and oxidizing conditions are required to constrain reaction mechanisms and assess the viability of magnetite-mediated processes. By bridging Earth analog research with targeted Martian exploration, these integrated efforts will significantly advance our understanding of how serpentinization-driven magnetite systems may have influenced the emergence, adaptability, and sustainability of life on the planetary bodies.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

VN: Validation, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Formal Analysis. SJ: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Methodology, Validation. AB: Validation, Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support by the Department of Space, Government of India. We thank Haitao Shang and Deepali Singh for their meaningful discussions and suggestions. Furthermore, the three reviewers and the handling editor Long Xiao are thanked for thorough and constructive reviews of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor LX declared a current collaboration with the author ABS large RT.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Afanasyev, O. I., Kuchuk, E., Usanov, D. L., and Chusov, D. (2019). Reductive amination in the synthesis of pharmaceuticals. Chem. Rev. 119 (23), 11857–11911. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00383

Altieri, F., Frigeri, A., Lavagna, M., Le Gall, A., Nikiforov, S. Y., Stoker, C., et al. (2023). Investigating the Oxia planum subsurface with the ExoMars rover and drill. Adv. Space Res. 71 (11), 4895–4903. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2023.01.044

Amador, E. S., Bandfield, J. L., and Thomas, N. H. (2018). A search for minerals associated with serpentinization across Mars using CRISM spectral data. Icarus 311, 113–134. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2018.03.021

Andreani, M., Muñoz, M., Marcaillou, C., and Delacour, A. (2013). μXANES study of iron redox state in serpentine during oceanic serpentinization. Lithos 178, 70–83. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2013.04.008

Ansari, A. H. (2023). Detection of organic matter on Mars, results from various Mars missions, challenges, and future strategy: a review. Front. Astronomy Space Sci. 10, 1075052. doi:10.3389/fspas.2023.1075052

Aoki, S., Kasaba, Y., Giuranna, M., Geminale, A., Sindoni, G., Nakagawa, H., et al. (2011). Detection of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in the Martian atmosphere with MEX/PFS. EPSC-DPS Jt. Meet. 2011, 622Available online at: https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EPSC-DPS2011/EPSC-DPS2011-622.pdf

Bach, W., Paulick, H., Garrido, C. J., Ildefonse, B., Meurer, W. P., and Humphris, S. E. (2006). Unraveling the sequence of serpentinization reactions: petrography, mineral chemistry, and petrophysics of serpentinites from MAR 15 N (ODP leg 209, site 1274). Geophys. Res. Lett. 33 (13). doi:10.1029/2006GL025681

Barbier, S., Huang, F., Andreani, M., Tao, R., Hao, J., Eleish, A., et al. (2020). A review of H2, CH4, and hydrocarbon formation in experimental serpentinization using network analysis. Front. Earth Sci. 8, 209. doi:10.3389/feart.2020.00209

Barge, L. M., Flores, E., Weber, J. M., Fraeman, A. A., Yung, Y. L., VanderVelde, D., et al. (2022). Prebiotic reactions in a Mars analog iron mineral system: effects of nitrate, nitrite, and ammonia on amino acid formation. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 336, 469–479. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2022.08.038

Beard, J. S., Frost, B. R., Fryer, P., McCaig, A., Searle, R., Ildefonse, B., et al. (2009). Onset and progression of serpentinization and magnetite formation in olivine-rich troctolite from IODP hole U1309D. J. Petrology 50 (3), 387–403. doi:10.1093/petrology/egp004

Beinlich, A., Plümper, O., Boter, E., Müller, I. A., Kourim, F., Ziegler, M., et al. (2020). Ultramafic rock carbonation: constraints from listvenite core BT1B, Oman drilling project. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 125 (6), e2019JB019060. doi:10.1029/2019JB019060

Bonnemains, D., Carlut, J., Escartín, J., Mével, C., Andreani, M., and Debret, B. (2016). Magnetic signatures of serpentinization at ophiolite complexes. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 17 (8), 2969–2986. doi:10.1002/2016GC006321

Brazelton, W. J., Nelson, B., and Schrenk, M. O. (2012). Metagenomic evidence for H2 oxidation and H2 production by serpentinite-hosted subsurface microbial communities. Front. Microbiol. 2, 268. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2011.00268

Bultel, B., Wieczorek, M., Mittelholz, A., Johnson, C. L., Gattacceca, J., Fortier, V., et al. (2025). Aqueous alteration as an origin of Martian magnetization. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 130 (1), e2023JE008111. doi:10.1029/2023JE008111

Chen, Q. W., and Bahnemann, D. W. (2000). Reduction of carbon dioxide by magnetite: implications for the primordial synthesis of organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122 (5), 970–971. doi:10.1021/ja991278y

Cooperdock, E. H. G., Stockli, D. F., Kelemen, P. B., and de Obeso, J. C. (2020). Timing of magnetite growth associated with peridotite-hosted carbonate veins in the SE samail ophiolite, wadi fins, Oman. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 125 (5), e2019JB018632. doi:10.1029/2019JB018632

Costa, K. M., Russell, J. M., Vogel, H., and Bijaksana, S. (2015). Hydrological connectivity and mixing of Lake towuti, Indonesia in response to paleoclimatic changes over the last 60,000 years. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 417, 467–475. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.10.009

Dilshara, P., Abeysinghe, B., Premasiri, R., Dushyantha, N., Ratnayake, N., Senarath, S., et al. (2025). Transforming nickel toxicity into resource recovery through phytomining: opportunities and applications in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 22, 8405–8424. doi:10.1007/s13762-025-06362-z

Ehlmann, B. L., Mustard, J. F., Swayze, G. A., Clark, R. N., Bishop, J. L., Poulet, F., et al. (2009). Identification of hydrated silicate minerals on Mars using MRO-CRISM: geologic context near nili fossae and implications for aqueous alteration. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 114 (E2). doi:10.1029/2009JE003339

Ehlmann, B. L., Mustard, J. F., and Murchie, S. L. (2010). Geologic setting of serpentine deposits on Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37 (6). doi:10.1029/2010GL042596

Encrenaz, T., Bézard, B., Greathouse, T. K., Richter, M. J., Lacy, J. H., Atreya, S. K., et al. (2004). Hydrogen peroxide on Mars: evidence for spatial and seasonal variations. Icarus 170 (2), 424–429. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.05.008

Evans, B. W. (2004). The serpentinite multisystem revisited: chrysotile is metastable. Int. Geol. Rev. 46 (6), 479–506. doi:10.2747/0020-6814.46.6.479

Evans, B. W. (2008). Control of the products of serpentinization by the Fe2+ mg− 1 exchange potential of olivine and orthopyroxene. J. Petrology 49 (10), 1873–1887. doi:10.1093/petrology/egn050

Evans, B. W. (2010). Lizardite versus antigorite serpentinite: magnetite, hydrogen, and life (?). Geology 38 (10), 879–882. doi:10.1130/G31158.1

Evans, B. W., Kuehner, S. M., Joswiak, D. J., and Cressey, G. (2017). Serpentine, iron-rich phyllosilicates and fayalite produced by hydration and Mg depletion of peridotite, duluth complex, Minnesota, USA. J. Petrology 58 (3), 495–512. doi:10.1093/petrology/egx024

Falk, E. S., and Kelemen, P. B. (2015). Geochemistry and petrology of listvenite in the samail ophiolite, Sultanate of Oman: complete carbonation of peridotite during ophiolite emplacement. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 160, 70–90. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2015.03.014

Farkas-Takács, A., Kiss, C., Góbi, S., and Kereszturi, Á. (2022). Serpentinization in the thermal evolution of icy kuiper belt objects in the early solar system. Planet. Sci. J. 3 (3), 54. doi:10.3847/psj/ac5175

Fernando, G. W. A. R., Baumgartner, L. P., and Hofmeister, W. (2013). High-temperature metasomatism in ultramafic granulites of highland complex, Sri Lanka. J. Geol. Soc. Sri Lanka 15, 163–181. Available online at: http://repository.ou.ac.lk/handle/94ousl/389.

Fernando, G. W. A. R., Dharmapriya, P. L., and Baumgartner, L. P. (2017). Silica-undersaturated reaction zones at a crust–mantle interface in the highland complex, Sri Lanka: mass transfer and melt infiltration during high-temperature metasomatism. Lithos 284, 237–256. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2017.04.011

Ferus, M., Kubelík, P., Knížek, A., Pastorek, A., Sutherland, J., and Civiš, S. (2017). High energy radical chemistry formation of HCN-Rich atmospheres on early Earth. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 6275. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-06489-1

Fones, E. M., Colman, D. R., Kraus, E. A., Nothaft, D. B., Poudel, S., Rempfert, K. R., et al. (2019). Physiological adaptations to serpentinization in the samail ophiolite, Oman. ISME J. 13 (7), 1750–1762. doi:10.1038/s41396-019-0391-2

Fornaro, T., Steele, A., and Brucato, J. R. (2018). Catalytic/Protective properties of Martian minerals and implications for possible origin of life on Mars. Life 8 (4), 56. doi:10.3390/life8040056

Fraeman, A. A., Edgar, L. A., Rampe, E. B., Thompson, L. M., Frydenvang, J., Fedo, C. M., et al. (2020). Evidence for a diagenetic origin of vera rubin ridge, gale crater, Mars: summary and synthesis of Curiosity's exploration campaign. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 125 (12), e2020JE006527. doi:10.1029/2020JE006527

Franzson, H., Zierenberg, R., and Schiffman, P. (2008). Chemical transport in geothermal systems in Iceland: evidence from hydrothermal alteration. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 173 (3-4), 217–229. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2008.01.027

Frost, B. R., Evans, K. A., Swapp, S. M., Beard, J. S., and Mothersole, F. E. (2013). The process of serpentinization in dunite from New Caledonia. Lithos 178, 24–39. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2013.02.002

Gao, Y., Lei, M., Kumar, B. S., Smith, H. B., Han, S. H., Sangabattula, L., et al. (2025). Geological ammonia: stimulated NH3 production from rocks. Joule 9, 101805. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2024.12.006

Geymond, U., Briolet, T., Combaudon, V., Sissmann, O., Martinez, I., Duttine, M., et al. (2023). Reassessing the role of magnetite during natural hydrogen generation. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1169356. doi:10.3389/feart.2023.1169356

Gholami, Z., Gholami, F., Tišler, Z., Hubáček, J., Tomas, M., Bačiak, M., et al. (2022). Production of light olefins via fischer-tropsch process using iron-based catalysts: a review. Catalysts 12 (2), 174. doi:10.3390/catal12020174

Góbi, S., and Kereszturi, Á. (2019). Analyzing the role of interfacial water on sulfate formation on present Mars. Icarus 322, 135–143. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2019.01.005

Godard, M., Jousselin, D., and Bodinier, J. L. (2000). Relationships between geochemistry and structure beneath a palaeo-spreading centre: a study of the mantle section in the Oman ophiolite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 180 (1-2), 133–148. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(00)00149-7

Gröger, H. (2003). Catalytic enantioselective strecker reactions and analogous syntheses. Chem. Rev. 103 (8), 2795–2828. doi:10.1021/cr020038p

Le Guillou, C., Dohmen, R., Rogalla, D., Müller, T., Vollmer, C., and Becker, H. W. (2015). New experimental approach to study aqueous alteration of amorphous silicates at low reaction rates. Chem. Geol. 412, 179–192. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2015.06.027

Hanghøj, K., Kelemen, P. B., Hassler, D., and Godard, M. (2010). Composition and genesis of depleted mantle peridotites from the wadi tayin massif, Oman ophiolite; major and trace element geochemistry, and Os isotope and PGE systematics. J. Petrology 51 (1-2), 201–227. doi:10.1093/petrology/egp077

Hara, E. K. (2023). Cyanide dynamics in serpentinizing systems: implications for prebiotic chemistry. University of Colorado at Boulder. Doctoral dissertation.

Hara, E. K., and Templeton, A. S. (2024). Releasing cyanide from ferrocyanide through carbon monoxide ligand exchange in alkaline aqueous environments. ACS Earth Space Chem. 8 (5), 900–906. doi:10.1021/acsearthspacechem.4c00038

He, X. F., Santosh, M., Tsunogae, T., Malaviarachchi, S. P., and Dharmapriya, P. L. (2016). Neoproterozoic arc accretion along the ‘eastern suture’ in Sri Lanka during gondwana assembly. Precambrian Res. 279, 57–80. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2016.04.006

Hennet, R. C., Holm, N. G., and Engel, M. H. (1992). Abiotic synthesis of amino acids under hydrothermal conditions and the origin of life: a perpetual phenomenon? Naturwissenschaften 79, 361–365. doi:10.1007/BF01140180

Hla, S. S., Duffy, G. J., Morpeth, L. D., Cousins, A., Roberts, D. G., Edwards, J. H., et al. (2010). Catalysts for water–gas shift processing of coal-derived syngases. Asia-Pacific J. Chem. Eng. 5 (4), 585–592. doi:10.1002/apj.439

Holm, N. G., and Charlou, J. L. (2001). Initial indications of abiotic formation of hydrocarbons in the rainbow ultramafic hydrothermal system, mid-atlantic ridge. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 191 (1-2), 1–8. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(01)00397-1

Huang, R., Sun, W., Song, M., and Ding, X. (2019). Influence of pH on molecular hydrogen (H2) generation and reaction rates during serpentinization of peridotite and olivine. Minerals 9 (11), 661. doi:10.3390/min9110661

Kakkassery, A. I., Haritha, A., and Rajesh, V. J. (2022). Serpentine-magnesite association of Salem ultramafic complex, southern India: a potential analogue for Mars. Planet. Space Sci. 221, 105528. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2022.105528

Kelemen, P. B., and Matter, J. (2008). In situ carbonation of peridotite for CO2 storage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105 (45), 17295–17300. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805794105

Kelemen, P., Al Rajhi, A., Godard, M., Ildefonse, B., Köpke, J., MacLeod, C., et al. (2013). Scientific drilling and related research in the samail ophiolite, Sultanate of Oman. Sci. Drill. 15, 64–71. doi:10.5194/sd-15-64-2013

Kelley, D. S., Karson, J. A., Blackman, D. K., FruÈh-Green, G. L., Butterfield, D. A., Lilley, M. D., et al. (2001). An off-axis hydrothermal vent field near the mid-atlantic ridge at 30 N. Nature 412 (6843), 145–149. doi:10.1038/35084000

Kelley, D. S., Karson, J. A., Fruh-Green, G. L., Yoerger, D. R., Shank, T. M., Butterfield, D. A., et al. (2005). A serpentinite-hosted ecosystem: the lost city hydrothermal field. Science 307 (5714), 1428–1434. doi:10.1126/science.1102556

Kereszturi, Á., and Góbi, S. (2014). Possibility of H2O2 decomposition in thin liquid films on Mars. Planet. Space Sci. 103, 153–166. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2014.07.017

Klein, F., Bach, W., Humphris, S. E., Kahl, W. A., Jöns, N., Moskowitz, B., et al. (2014). Magnetite in seafloor serpentinite—Some like it hot. Geology 42 (2), 135–138. doi:10.1130/G35068.1

Kossacki, K. J., and Markiewicz, W. J. (2010). Interfacial liquid water on Mars and its potential role in formation of hill and dune gullies. Icarus 210 (1), 83–91. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2010.06.029

Kovalenko, S. P. (2020). Physicochemical processes that probably originated life. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 46, 675–691. doi:10.1134/S1068162020040093

Kumarathilaka, C. B., Dissanayake, P., and Vithanage, M. A. (2014). Geochemistry of serpentinite soils: a brief overview. J. Ceologicol Soc. Sri Lanka 16 (2014), 53–63.

Lamadrid, H. M., Rimstidt, J. D., Schwarzenbach, E. M., Klein, F., Ulrich, S., Dolocan, A., et al. (2017). Effect of water activity on rates of serpentinization of olivine. Nat. Commun. 8 (1), 16107. doi:10.1038/ncomms16107

Lang, S. Q., Butterfield, D. A., Schulte, M., Kelley, D. S., and Lilley, M. D. (2010). Elevated concentrations of formate, acetate and dissolved organic carbon found at the lost city hydrothermal field. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 74 (3), 941–952. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2009.10.045

Lasne, J., Noblet, A., Szopa, C., Navarro-González, R., Cabane, M., Poch, O., et al. (2016). Oxidants at the surface of Mars: a review in light of recent exploration results. Astrobiology 16 (12), 977–996. doi:10.1089/ast.2016.1502

Leong, J. A. M., and Shock, E. L. (2020). Thermodynamic constraints on the geochemistry of low-temperature, Continental, serpentinization-generated fluids. Am. J. Sci. 320 (3), 185–235. doi:10.2475/03.2020.01

Li, X., and Paier, J. (2019). Partial oxidation of methanol on the Fe3O4 (111) surface studied by density functional theory. J. Phys. Chem. 123 (13), 8429–8438. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b10557

Lillis, R. J., Frey, H. V., Manga, M., Mitchell, D. L., Lin, R. P., Acuña, M. H., et al. (2008). An improved crustal magnetic field map of Mars from electron reflectometry: highland volcano magmatic history and the end of the Martian dynamo. Icarus 194 (2), 575–596. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.09.032

Malaviarachchi, S. P. K., Dharmapriya, P., Chandrajith, R., Pitawala, H. M. T. G. A., Karunatillake, S., Hughes, E., et al. (2024). Overview of Sri Lanka's rare occurrence of serpentinites within Proterozoic high-grade metamorphic basement rocks as a Mars-context research site. LPI Contrib. 3040, 2324.

Mayhew, L. E., and Ellison, E. T. (2020). A synthesis and meta-analysis of the Fe chemistry of serpentinites and serpentine minerals. Philosophical Trans. R. Soc. A 378 (2165), 20180420. doi:10.1098/rsta.2018.0420

Mayhew, L. E., Ellison, E. T., Miller, H. M., Kelemen, P. B., and Templeton, A. S. (2018). Iron transformations during low temperature alteration of variably serpentinized rocks from the samail ophiolite, Oman. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 222, 704–728. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2017.11.023

McCollom, T. M., and Bach, W. (2009). Thermodynamic constraints on hydrogen generation during serpentinization of ultramafic rocks. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 73 (3), 856–875. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2008.10.032

McCollom, T. M., and Seewald, J. S. (2007). Abiotic synthesis of organic compounds in deep-sea hydrothermal environments. Chem. Rev. 107 (2), 382–401. doi:10.1021/cr0503660

Miller, H. M., Matter, J. M., Kelemen, P., Ellison, E. T., Conrad, M. E., Fierer, N., et al. (2016). Modern water/rock reactions in Oman hyperalkaline peridotite aquifers and implications for microbial habitability. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 179, 217–241. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2016.01.033

Mitra, K., Bahl, Y., Ledingham, G. J., Hernandez-Robles, A., Stevanovic, A., Westover, G., et al. (2024). Magnetite survivability and non-stoichiometric magnetite formation in presence of oxyhalogen brines on Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51 (19), e2024GL111114. doi:10.1029/2024GL111114

Molamahmood, H. V., Geng, W., Wei, Y., Miao, J., Yu, S., Shahi, A., et al. (2022). Catalyzed H2O2 decomposition over iron oxides and oxyhydroxides: insights from oxygen production and organic degradation. Chemosphere 291, 133037. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.133037

Monnier, C., Girardeau, J., Le Mée, L., and Polvé, M. (2006). Along-ridge petrological segmentation of the mantle in the Oman ophiolite. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 7 (11). doi:10.1029/2006GC001320

Monnin, C., Chavagnac, V., Boulart, C., Ménez, B., Gérard, M., Gérard, E., et al. (2014). The low temperature hyperalkaline hydrothermal system of the prony bay (new caledonia). Biogeosci. Discuss. 11, 6221–6267. doi:10.5194/bgd-11-6221-2014

Morrill, P. L., Kuenen, J. G., Johnson, O. J., Suzuki, S., Rietze, A., Sessions, A. L., et al. (2013). Geochemistry and geobiology of a present-day serpentinization site in California: the cedars. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 109, 222–240. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2013.01.043

Müntener, O. (2010). Serpentine and serpentinization: a link between planet formation and life. Geology 38 (10), 959–960. doi:10.1130/focus102010.1

Mustard, J. F., Ehlmann, B. L., Murchie, S. L., Poulet, F., Mangold, N., Head, J. W., et al. (2009). Composition, morphology, and stratigraphy of Noachian crust around the isidis basin. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 114 (E2). doi:10.1029/2009JE003349

Nair, V. M., Basu Sarbadhikari, A., Srivastava, Y., Dharmapriya, P. L., Malaviarachchi, S. P. K., Karunatillake, S., et al. (2024). A potential intraplate serpentinization site of Sri Lanka as a Mars analogue. LPI Contrib. 3040, 2005. Available online at: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2024LPICo3040.2005N/abstract.

Nazarova, K. A., and Harrison, C. G. A. (2000). Serpentinization of Martian crust and mantle and the nature of Martian magnetic anomalies. Eos Trans. AGU 81 (19).

Niles, P. B., Michalski, J., Ming, D. W., and Golden, D. C. (2017). Elevated olivine weathering rates and sulfate formation at cryogenic temperatures on Mars. Nat. Commun. 8 (1), 998. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01227-7

de Obeso, J. C., and Kelemen, P. B. (2020). Major element mobility during serpentinization, oxidation and weathering of mantle peridotite at low temperatures. Philosophical Trans. R. Soc. A 378 (2165), 20180433. doi:10.1098/rsta.2018.0433

de Obeso, J. C., Santiago Ramos, D. P., Higgins, J. A., and Kelemen, P. B. (2021). A Mg isotopic perspective on the mobility of magnesium during serpentinization and carbonation of the Oman ophiolite. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126 (2), e2020JB020237. doi:10.1029/2020JB020237

Omran, A., Gonzalez, A., Menor-Salvan, C., Gaylor, M., Wang, J., Leszczynski, J., et al. (2023). Serpentinization-associated mineral catalysis of the protometabolic formose system. Life 13 (6), 1297. doi:10.3390/life13061297

Oró, J. (1961). Mechanism of synthesis of adenine from hydrogen cyanide under possible primitive Earth conditions. Nature 191 (4794), 1193–1194. doi:10.1038/1911193a0

Oze, C., and Sharma, M. (2005). Have olivine, will gas: serpentinization and the abiogenic production of methane on Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32 (10). doi:10.1029/2005GL022691

Ozturk, S. F., Liu, Z., Sutherland, J. D., and Sasselov, D. D. (2023). Origin of biological homochirality by crystallization of an RNA precursor on a magnetic surface. Sci. Adv. 9 (23), eadg8274. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adg8274

Papineau, D., and Du, M. (2025). Abiotic synthesis of organic matter in deep-sea basalt gives clues for the origin of life on earth and beyond. Innovation Life 3, 100139. doi:10.59717/j.xinn-life.2025.100139

Preiner, M., Xavier, J. C., Sousa, F. L., Zimorski, V., Neubeck, A., Lang, S. Q., et al. (2018). Serpentinization: connecting geochemistry, ancient metabolism and industrial hydrogenation. Life 8 (4), 41. doi:10.3390/life8040041

Preiner, M., Igarashi, K., Muchowska, K. B., Yu, M., Varma, S. J., Kleinermanns, K., et al. (2020). A hydrogen-dependent geochemical analogue of primordial carbon and energy metabolism. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4 (4), 534–542. doi:10.1038/s41559-020-1125-6

Proskurowski, G., Lilley, M. D., Seewald, J. S., Früh-Green, G. L., Olson, E. J., Lupton, J. E., et al. (2008). Abiogenic hydrocarbon production at lost city hydrothermal field. Science 319 (5863), 604–607. doi:10.1126/science.1151194

Rajapaksha, A. U., Vithanage, M., Oze, C., Bandara, W. M. A. T., and Weerasooriya, R. (2012). Nickel and manganese release in serpentine soil from the ussangoda Ultramafic Complex, Sri Lanka. Geoderma 189, 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2012.04.019

Ramirez, R. M., Kopparapu, R., Zugger, M. E., Robinson, T. D., Freedman, R., and Kasting, J. F. (2014). Warming early Mars with CO2 and H2. Nat. Geosci. 7 (1), 59–63. doi:10.1038/ngeo2000

Rampe, E. B., Bristow, T. F., Morris, R. V., Morrison, S. M., Achilles, C. N., Ming, D. W., et al. (2020). Mineralogy of vera rubin ridge from the Mars science laboratory CheMin instrument. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 125 (9), e2019JE006306. doi:10.1029/2019JE006306

Reynolds, R. L., and Rosenbaum, J. G. (2005). Magnetic mineralogy of sediments in bear Lake and its watershed, Utah, Idaho, and Wyoming: support for paleoenvironmental and paleomagnetic interpretations. U. S. Geol. Surv. doi:10.1130/2009.2450(06)

Rushdi, A. I., and Simoneit, B. R. T. (2001). Lipid formation by aqueous Fischer–tropsch-type synthesis over a temperature range of 100–400 oC. Orig. Life Evol. Biosphere 31 (1–2), 103–118. doi:10.1023/A:1006702503954

Russell, M. J., Hall, A. J., and Martin, W. (2010). Serpentinization as a source of energy at the origin of life. Geobiology 8 (5), 355–371. doi:10.1111/j.1472-4669.2010.00249.x

Samulewski, R. B., Gonçalves, J. M., Urbano, A., da Costa, A. C. S., Ivashita, F. F., Paesano, A., et al. (2020). Magnetite synthesis in the presence of cyanide or thiocyanate under prebiotic chemistry conditions. Life 10 (4), 34. doi:10.3390/life10040034

Santos-Carballal, D., Roldan, A., Dzade, N. Y., and De Leeuw, N. H. (2018). Reactivity of CO2 on the surfaces of magnetite (Fe3O4), greigite (Fe3S4) and mackinawite (FeS). Philosophical Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 376 (2110), 20170065. doi:10.1098/rsta.2017.0065

Scheller, E. L., Razzell Hollis, J., Cardarelli, E. L., Steele, A., Beegle, L. W., Bhartia, R., et al. (2022). Aqueous alteration processes in jezero crater, mars—implications for organic geochemistry. Science 378 (6624), 1105–1110. doi:10.1126/science.abo5204

Schulte, M., Blake, D., Hoehler, T., and McCollom, T. (2006). Serpentinization and its implications for life on the early Earth and Mars. Astrobiology 6 (2), 364–376. doi:10.1089/ast.2006.6.364

Schwander, L., Brabender, M., Mrnjavac, N., Wimmer, J. L., Preiner, M., and Martin, W. F. (2023). Serpentinization as the source of energy, electrons, organics, catalysts, nutrients and pH gradients for the origin of LUCA and life. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1257597. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1257597

Segura, A., and Navarro-González, R. (2005). Nitrogen fixation on early Mars by volcanic lightning and other sources. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32 (5). doi:10.1029/2004GL021910

Seyfried, W. E., Foustoukos, D. I., and Fu, Q. (2007). Redox evolution and mass transfer during serpentinization: an experimental and theoretical study at 200oC, 500 bar with implications for ultramafic-hosted hydrothermal systems at mid-Ocean Ridges. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 71 (15), 3872–3886. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2007.05.015

Shen, J., Paterson, G. A., Wang, Y., Kirschvink, J. L., Pan, Y., and Lin, W. (2023). Renaissance for magnetotactic bacteria in astrobiology. ISME J. 17 (10), 1526–1534. doi:10.1038/s41396-023-01495-w

Sleep, N. H., Meibom, A., Fridriksson, T., Coleman, R. G., and Bird, D. K. (2004). H2-rich fluids from serpentinization: geochemical and biotic implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101 (35), 12818–12823. doi:10.1073/pnas.0405289101

Smirnov, A., Hausner, D., Laffers, R., Strongin, D. R., and Schoonen, M. A. (2008). Abiotic ammonium formation in the presence of Ni-Fe metals and alloys and its implications for the Hadean nitrogen cycle. Geochem. Trans. 9, 5–20. doi:10.1186/1467-4866-9-5

Squyres, S. W., Grotzinger, J. P., Arvidson, R. E., Bell III, J. F., Calvin, W., Christensen, P. R., et al. (2004). In situ evidence for an ancient aqueous environment at Meridiani Planum, Mars. science 306 (5702), 1709–1714. doi:10.1126/science.1104559

Streit, E., Kelemen, P., and Eiler, J. (2012). Coexisting serpentine and quartz from carbonate-bearing serpentinized peridotite in the samail ophiolite, Oman. Contributions Mineralogy Petrology 164, 821–837. doi:10.1007/s00410-012-0775-z

Suda, K., Aze, T., Miyairi, Y., Yokoyama, Y., Matsui, Y., Ueda, H., et al. (2022). The origin of methane in serpentinite-hosted hyperalkaline hot spring at hakuba happo, Japan: radiocarbon, methane isotopologue and noble gas isotope approaches. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 585, 117510. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2022.117510

Summers, D. P., and Khare, B. (2007). Nitrogen fixation on early Mars and other terrestrial planets: experimental demonstration of abiotic fixation reactions to nitrite and nitrate. Astrobiology 7 (2), 333–341. doi:10.1089/ast.2006.0032

Taylor, A. P., Barry, J. C., and Webb, R. I. (2001). Structural and morphological anomalies in magnetosomes: possible biogenic origin for magnetite in ALH84001. J. Microsc. 201 (1), 84–106. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2818.2001.00760.x

Templeton, A. S., Ellison, E. T., Glombitza, C., Morono, Y., Rempfert, K. R., Hoehler, T. M., et al. (2021). Accessing the subsurface biosphere within rocks undergoing active low-temperature serpentinization in the samail ophiolite (oman drilling project). J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 126 (10), e2021JG006315. doi:10.1029/2021JG006315

Tutolo, B. M., and Tosca, N. J. (2023). Observational constraints on the process and products of Martian serpentinization. Sci. Adv. 9 (5), eadd8472. doi:10.1126/sciadv.add8472

Vance, S., Harnmeijer, J., Kimura, J., Hussmann, H., DeMartin, B., and Brown, J. M. (2007). Hydrothermal systems in small ocean planets. Astrobiology 7 (6), 987–1005. doi:10.1089/ast.2007.0075

Vaniman, D. T., Bish, D. L., Ming, D. W., Bristow, T. F., Morris, R. V., Blake, D. F., et al. (2014). Mineralogy of a mudstone at yellowknife Bay, gale crater, Mars. Science 343 (6169), 1243480. doi:10.1126/science.1243480

Viviano, C. E., Moersch, J. E., and McSween, H. Y. (2013). Implications for early hydrothermal environments on Mars through the spectral evidence for carbonation and chloritization reactions in the nili fossae region. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 118 (9), 1858–1872. doi:10.1002/jgre.20141

Wang, Y. X., Ouyang, D. J., Dharmapriya, P., Chandrajith, R., Pitawala, H. M. T. G. A., Karunatilake, S., et al. (2024). Serpentinite in Sri Lanka: preliminary petrological and geochemical constraints and implication for Martian comparisons. LPI Contrib. 3040, 1870.

Wordsworth, R., Kalugina, Y., Lokshtanov, S., Vigasin, A., Ehlmann, B., Head, J., et al. (2017). Transient reducing greenhouse warming on early Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44 (2), 665–671. doi:10.1002/2016GL071766

Wordsworth, R., Knoll, A. H., Hurowitz, J., Baum, M., Ehlmann, B. L., Head, J. W., et al. (2021). A coupled model of episodic warming, oxidation and geochemical transitions on early Mars. Nat. Geosci. 14 (3), 127–132. doi:10.1038/s41561-021-00701-8

Keywords: serpentinization, magnetite, prebiotic pathways, terrestrial analogs, habitability

Citation: Nair VM, Jagmag SH and Basu Sarbadhikari A (2025) The role of magnetite-rich environments in prebiotic chemistry and astrobiology: insights into serpentinization processes on Mars. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 12:1622043. doi: 10.3389/fspas.2025.1622043

Received: 02 May 2025; Accepted: 21 October 2025;

Published: 21 November 2025.

Edited by:

Long Xiao, China University of Geosciences Wuhan, ChinaReviewed by:

Akos Kereszturi, Hungarian Academy of Sciences (MTA), HungaryDominic Papineau, University College London, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Nair, Jagmag and Basu Sarbadhikari. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Varsha M. Nair, dmFyc2hhQHBybC5yZXMuaW4=

Varsha M. Nair

Varsha M. Nair Sana Hasan Jagmag

Sana Hasan Jagmag Amit Basu Sarbadhikari

Amit Basu Sarbadhikari