- 1Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Bangalore, India

- 2Department of Applied Optics and Photonics, University of Calcutta, Kolkata, India

- 3M.P. Birla Institute of Fundamental Research, Bangalore, India

- 4LUNEX EuroMoonMars EuroSpaceHub, Leiden, Netherlands

- 5Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, India

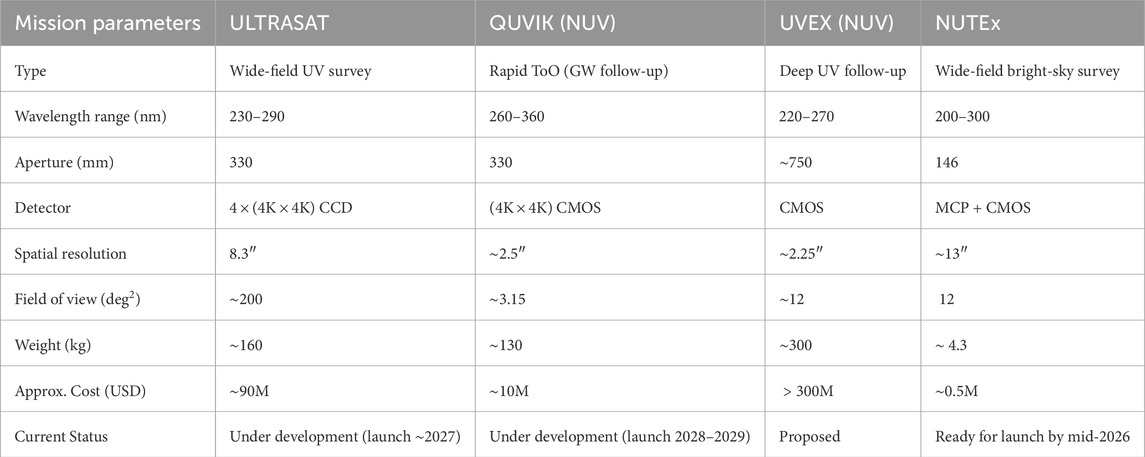

The Near Ultraviolet Transient Explorer (NUTEx) is a CubeSat-based near-ultraviolet (NUV) imaging payload designed for transient sky surveys and is currently under development. CubeSats are compact and cost-effective satellite platforms that have emerged as versatile tools for scientific exploration and technology demonstrations in space. NUTEx is an imaging telescope operating in the 200–300 nm wavelength range, intended for deployment on a micro-satellite bus. The optical system is based on a Ritchey–Chrétien (RC) telescope configuration, featuring a 146-mm primary mirror. The detector is a photon-counting microchannel plate (MCP) device with a solar-blind photocathode, paired with an in-house-developed readout unit. The instrument has a wide field of view (FoV) of 4°, a peak effective area of approximately 18 cm2 at 260 nm, and can reach a sensitivity of 21 AB magnitude (SNR = 5) in a 1200-s exposure. The primary scientific objective of NUTEx is to monitor the night sky for transient phenomena, such as supernova remnants, flaring M-dwarf stars, and other short-timescale events. The payload is currently scheduled for launch in Q2-2026. This paper presents the NUTEx instrument design, outlines its scientific goals and capabilities, and provides an overview of the electronics and mechanical subsystems, including structural analysis.

1 Introduction

CubeSats are standardized miniature satellites that have emerged as a transformative platform for space-based astrophysical research, particularly in observational regimes such as the ultraviolet that are inaccessible from the ground. Their ability to deliver rapid, flexible, and cost-effective access to space allows them to complement larger observatories and respond swiftly to transient events. The growing availability of commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) components, ranging from power systems to precision attitude control units, has further streamlined CubeSat development, significantly reducing both cost and time (Douglas et al., 2019; Spence et al., 2022). With mission budgets typically in the range of US$5–10 million and development cycles of just 2–3 years, CubeSats enable rapid mission turnaround, opening new opportunities for focused science, technology demonstrations, and broader participation in space science by smaller institutions and emerging space programs (Shkolnik, 2018; Woellert et al., 2011).

We, the Space Payload Group (SPG) at the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IIA), are dedicated to designing and building innovative, low-cost instruments for ultraviolet (UV) astronomy. Our designs and results have been published in the open literature and adopted by other groups. For example, our recent payloads (Bharat Chandra et al., 2024c) showcase our expertise in compact space instruments, including a star camera built around a Raspberry Pi (Bharat Chandra et al., 2024d). These efforts illustrate that compact, resource-efficient instruments can still address important scientific questions in UV astronomy.

The Near Ultraviolet Transient Explorer (NUTEx) is a near-ultraviolet (NUV) imaging telescope currently under development to fly on a microsatellite bus. The instrument is a Ritchey–Chrétien (RC) telescope with a 146-mm diameter aperture, covering the 200–300 nm wavelength band using a solar-blind photocathode. It has a mean effective area of 15 cm2 across this band and can detect objects as faint as 21 AB magnitude (SNR = 5) with a 1200-s exposure. With a wide field of view (4°), NUTEx is optimized to observe and follow up variable NUV events such as stellar flares, supernova explosions, and other transient astrophysical events. NUTEx is particularly well suited to observe bright sky regions, like the Galactic plane, that are typically avoided by larger missions due to the sensitivity of their detectors. This enables the instrument to capture data from underexplored regions of the UV sky.

2 Motivation and scientific goals

The ultraviolet sky, particularly in the time domain, remains relatively underexplored despite its potential to provide important insights into explosive and variable astrophysical phenomena. Earlier missions provided valuable data but were constrained by narrow fields of view and a focus on targeted observations. Their sensitivity limits also prevented observations of brighter regions of the sky (Martin et al., 2005; Morrissey et al., 2005), such as the Galactic plane. These factors have left gaps in the systematic monitoring of transients and variables in the NUV, thereby limiting their ability to conduct broad time-domain surveys. This highlights the need for a dedicated UV survey instrument with wide-field capabilities. NUTEx, with its relatively lower sensitivity, is well suited to observe and survey these brighter regions of the sky that have been inaccessible to previous instruments.

Understanding the final stages of massive stars lives, particularly the processes leading to supernova (SN) explosions, remains an active area of research. While direct detections of SN progenitors are possible in rare, nearby cases, early UV observations provide an alternative way to probe stellar properties such as radius and surface composition before explosion (Chevalier, 1992). These early signals, including shock breakout and the subsequent UV shock-cooling emission, evolve rapidly, especially in compact stars, and are therefore inaccessible to most ground-based surveys (Nakar and Sari, 2010). A wide-field NUV imager can detect such fast transients, including breakout flares from extended stars and those embedded in dense circumstellar material (Ofek et al., 2010), and follow their shock-cooling signatures to help constrain parameters such as explosion energy, ejecta mass, and extinction (Rabinak and Waxman, 2011). With broad sky coverage, such an instrument would enable observations of a larger sample of these events, contributing to a better understanding of the final stages of massive stellar evolution (Sagiv et al., 2014).

These objectives, focused on surveying and mapping the sky for transient events in the NUV, define the primary science goals of NUTEx. The instrument’s wide field of view and tolerance to bright regions were chosen to support these goals, which remain the central driver of the mission.

Another key scientific objective that NUTEx can address is the study of stellar flaring events, including those occurring on M-dwarf stars. Stellar flares are transient bursts of radiation caused by magnetic reconnection in stars with convective envelopes, releasing energy across nearly all wavelengths (Davenport, 2016). Studying these flares in the NUV is important to capture emission components that are underestimated in optical bands, which allows more accurate energy assessments and a better understanding of their impact on stellar and close-in exoplanet environments (Brasseur et al., 2019). The Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s LSST is expected to detect large numbers of such flares in the optical domain, enabling statistical studies of their frequency, duration, and spatial distribution (Jacklin et al., 2015). However, the NUV emission, which arises from the hotter layers of the stellar atmosphere during flaring events, remains largely unexplored. NUTEx, with its wide field of view and tolerance to bright regions, may provide the missing higher energy coverage of these flare signatures and complement LSST by extending flare studies into the NUV region. Together, this combined approach may improve estimates of flare energetics and activity patterns in M-dwarf stars.

Although NUTEx is primarily designed for wide-field NUV surveys to detect transients and variable sources across large regions of the sky, it is also capable of responding to rapid alerts from rare events, such as GW170817 (Evans et al., 2017). This event was a luminous and rapidly fading UV transient associated with a binary neutron star merger, with emission peaking around the wavelength range where NUTEx has maximum effective area, making the instrument suitable for such observations. Rapid follow-ups by NUTEx can complement facilities specifically dedicated to gravitational wave follow-up, such as QUVIK (Werner et al., 2024), by providing additional sky coverage and timely early UV measurements.

Feasibility of detecting near-Earth objects (NEOs) in the NUV band has been demonstrated in earlier studies (Sagiv et al., 2014), and wide-field surveys such as the Palomar Transient Factory (PTF) have shown the ability to discover small, fast-moving objects using real-time pipelines (Waszczak et al., 2017; Polishook et al., 2012). While NEO detection is not a primary science goal for NUTEx, these studies highlight how incidental discoveries of such objects can naturally arise in wide-field survey observations. In the NUV, however, such capability is complicated by the sudden appearance of fast or bright transients in the field of view, which has previously triggered Bright Object Protection systems (e.g., in HST/STIS (Clampin, 1997) and AstroSat/UVIT (Srivastava et al., 2009; Ghosh et al., 2021)). Some of these triggers have been attributed to unexpected non-celestial objects, possibly NEOs.

In contrast, NUTEx is designed with a wider FoV and improved tolerance to bright regions, enabling it to handle such events without detector saturation. This characteristic is presented here not as a dedicated science driver, but as a demonstration of the instrument’s robustness: NUTEx can continue uninterrupted UV observations even when confronted with bright or fast-moving objects that might otherwise compromise detector safety. This resilience directly supports its main science objectives by ensuring long-duration, wide-field monitoring of transients and variable sources without unplanned interruptions. A comparison of NUTEx with relevant existing and proposed missions is provided in Table 1, highlighting differences in wavelength coverage, survey strategy, and other mission parameters. Mission parameters for other facilities, such as cost and mass, are taken from recent official releases and may be subject to change as these missions proceed through development and launch phases.

3 The instrument

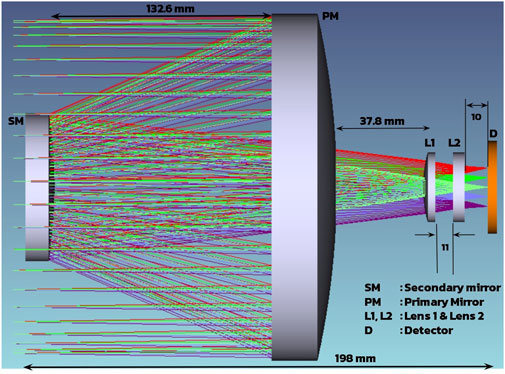

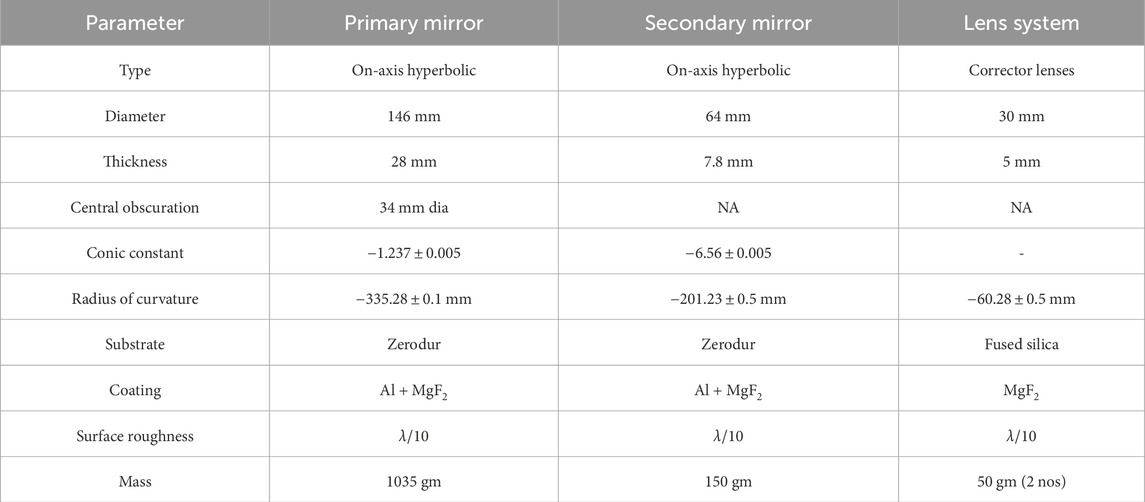

The optical design of NUTEx, as shown in Figure 1, has been developed to meet its primary science goal of surveying the transient sky in the NUV with a wide field of view capability. For the structure of the instrument, we have nominally chosen microsatellite platforms provided by the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO), which constrain the instrument volume to approximately 12U and impose a no-moving-parts requirement. The combination of these constraints and the intrinsically low UV photon flux from our targets required an optical design that minimizes reflective losses and maximizes throughput, with efficiency in the NUV band guiding the choice of coatings and materials. The mirrors are made from Zerodur, the lenses from fused silica, and the fixtures from aluminum alloy Al 6061-T6, providing stability while staying within the allocated mass and power budgets.

3.1 Optical design

To minimize reflection losses, the optical system uses only two reflecting surfaces: the primary mirror and the secondary mirror. The wide-field Ritchey-Chrétien configuration introduces additional optical aberrations, which are corrected by a set of two identical lenses positioned before the focal plane. An MCP-based photon-counting detector (PCD) is placed at the focal plane of the telescope. The optical design has been developed in coordination with the structural constraints and detector specifications, and the following sections provide a detailed discussion of the key components.

The primary mirror (PM) is a 146-mm diameter on-axis hyperbolic mirror, fabricated from Zerodur to minimize thermal expansion and ensure stability in space environment. It is coated with aluminum and overlaid with an

The detector system consists of a 40-mm MCP-based PCD developed by Photek1, paired with a Raspberry Pi (RPi) based readout unit. This compact readout architecture, as demonstrated by Bharat Chandra et al. (2024a), successfully integrated and qualified for the SING payload (Bharat Chandra et al., 2024b), is well-suited for CubeSat-class instruments. Together, the detector and the readout form a complete photon-counting imaging assembly for NUTEx.

3.1.1 Design analysis

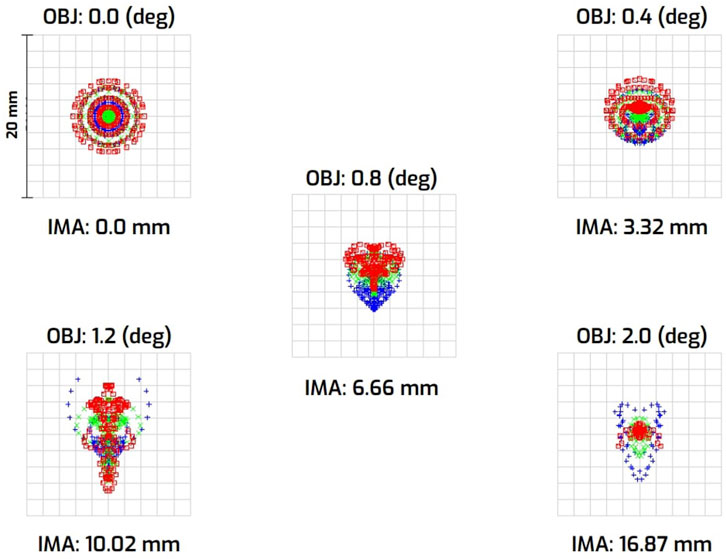

The field of view of 4° in NUTEx arises directly from the optical and detector configuration. With an effective focal length of 476 mm (f/3.3), a 146 mm primary mirror, a 64 mm secondary mirror, and a 40 mm diameter circular detector at the focal plane, the resulting coverage is limited to 4°. Expanding the FoV would either require shortening the focal length, which would degrade image quality and make aberration control more difficult in a Ritchey Chrétien configuration, or increasing the detector size, which is constrained by practical considerations. The adopted parameters therefore represent a balance between optical feasibility, detector coverage, and aberration control.

While the Ritchey Chrétien design eliminates spherical aberration and coma, residual field curvature and astigmatism are present. In the baseline RC design, the geometric spot radius varies between 70 and 120

Figure 2. Spot diagrams at the telescope focal plane for different field angles (0°–2°) marked with different wavelengths (blue: 2000 Å, green: 2500 Å, red: 3000 Å).

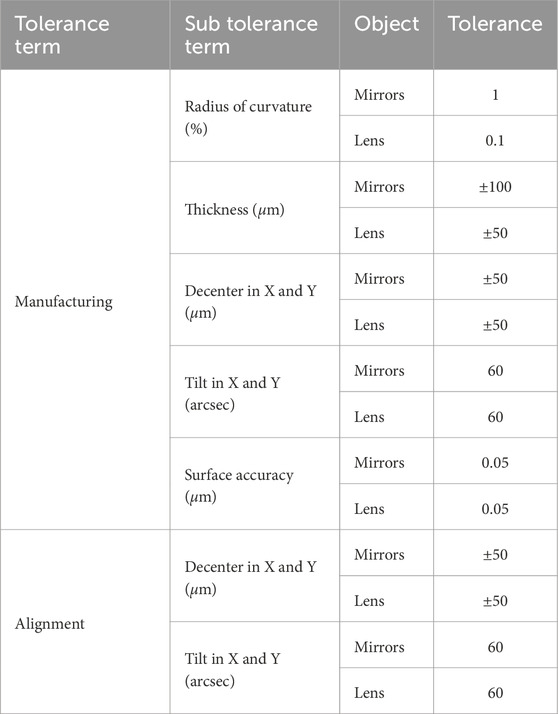

A sensitivity tolerance analysis was conducted for NUTEx to evaluate the impact of manufacturing deviations, alignment errors, and thermal shifts on its optical performance, and to establish acceptable tolerance limits for the optical components. The analysis was performed using Zemax®, incorporating tolerance specifications provided by the component manufacturers and constraints dictated by the practical alignment strategy. The evaluation criterion required achieving 80% encircled energy within a 20

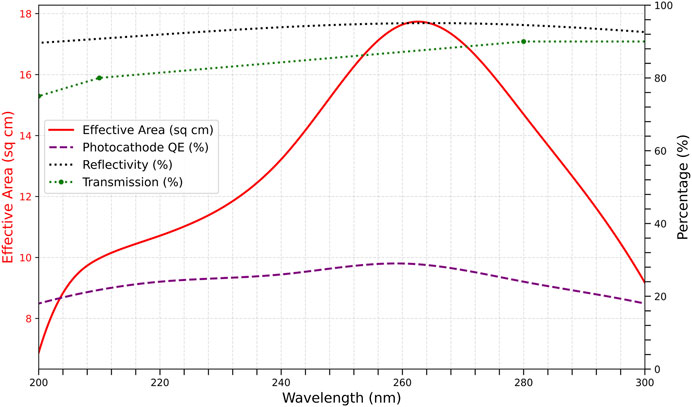

Effective area, expressed in cm2, quantifies the total system response by representing how efficiently the telescope transmits incident light to the detector. The effective area for NUTEx can be calculated from Equation 1,

Figure 3. Effective area of NUTEx (red curve) as a function of wavelength, overlaid with contributing factors: photocathode quantum efficiency (purple dashed), mirror reflectivity (black dotted), and optical transmission (green dotted).

The photocathode’s quantum efficiency (QE) is expressed as the proportion of photoelectrons generated

The typical maximum photon gain for a specific input wavelength and phosphor screen is given by Equation 3:

Considering

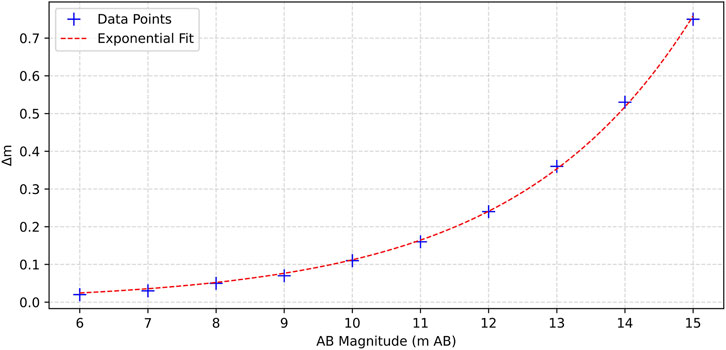

Figure 4. Photometric sensitivity of NUTEx: Minimum detectable brightness variation across AB magnitudes for a 10-s exposure at SNR = 5.

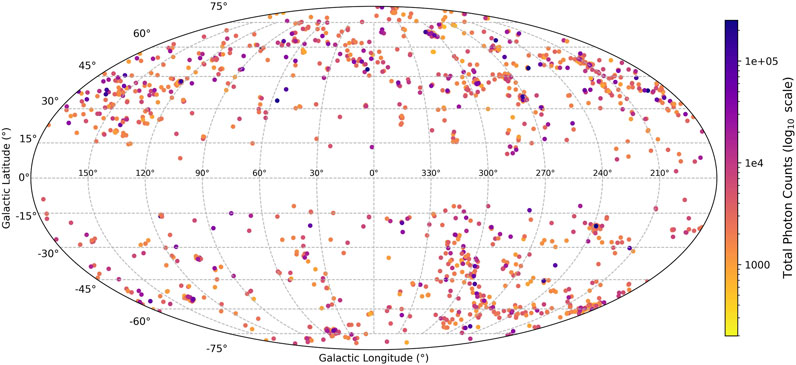

Figure 5. Simulated NUTEx photon count response for GALEX-detected UV variable sources from the GFCAT, assuming a 1K seconds exposure and the estimated effective area of NUTEx, plotted in Galactic coordinates.

3.2 Observation strategy

NUTEx will operate as an all-sky survey instrument with public data access, rather than following proposal-driven operations typical of large observatories. Data will be released without a proprietary lock period, providing open access for the community and positioning NUTEx as a community-serving facility. A low-Earth orbit (LEO) is sufficient for the scientific goals, allowing coverage of most of the sky within approximately 2 years; the specific orbital parameters are not critical for the mission objectives. Pointing constraints include maintaining roughly 90° Sun avoidance, while thermal control is ensured through multilayer insulation and design validation on the engineering model over the expected temperature range. Radiation tolerance of onboard electronics, including Raspberry Pis and STM32 controllers, has been considered based on existing space heritage and the recent Starberry-Sense launch (Bharat Chandra et al., 2024d). Observations will be carried out primarily during orbital night.

The observing strategy is designed to fulfill the primary science goals of surveying the sky for UV transients, monitoring bright regions, and conducting time-domain studies. The survey mode, combining continuous sky scanning with targeted monitoring of selected regions, allows systematic coverage to build statistically meaningful datasets for fast-evolving events such as supernova shock breakouts and stellar flares. A representative daily plan could include monitoring about five regions for 1 hour each, with the remainder of the orbit used for scanning. Rapid follow-up of transient alerts, such as gravitational wave triggers, for example, the GW170817 event, can be implemented as pointed observations; however, survey operations remain the core strategy, ensuring broad coverage while enabling timely response to high-priority events.

Several structural configurations were evaluated for NUTEx, including tubular, breadboard style, and modular cage designs, based on criteria such as alignment accuracy, assembly simplicity, and mass constraints. The modular cage was selected for its structural efficiency, ease of integration, and suitability for launch. Its implementation and analysis are discussed below.

4 Mechanical design and structural analysis

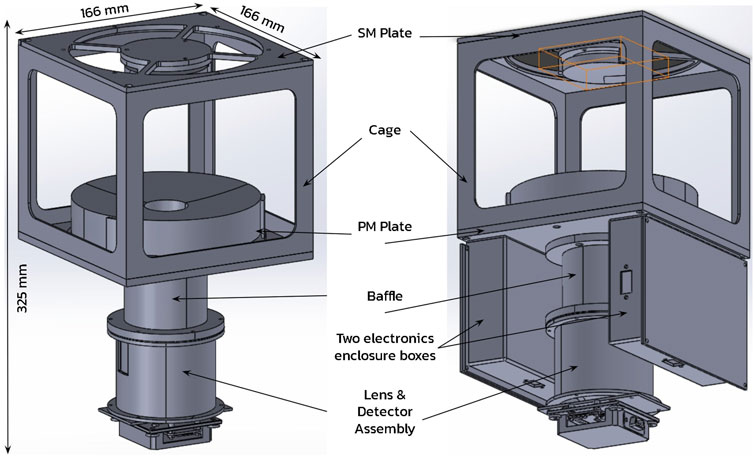

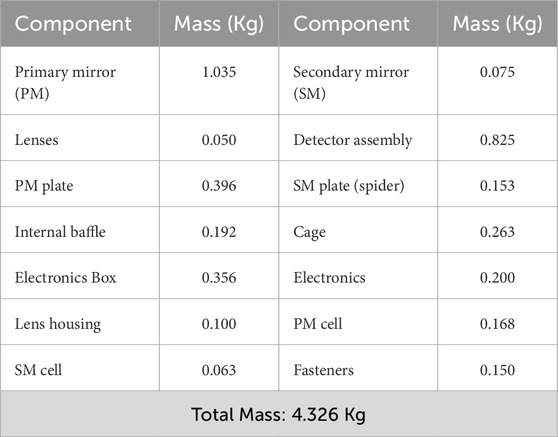

The NUTEx payload uses a modular cage structure that reduces mass while maintaining mechanical integrity, an important factor for ensuring launch viability on low-cost missions. Although launch costs to low Earth orbit declined by about 5.5% annually between 2000 and 2020 (Adilov et al., 2022), current rates still range from $5,000 to $50,000 per kilogram (Jones, 2018; Xu et al., 2019). Drawing from prior experience with cylindrical telescope housings, we selected an open-frame cage design (see Figure 6) over traditional enclosed tubes that restrict access during alignment. This configuration offers multi-sided access for integration and alignment, better accommodating clean-room procedures while simplifying mechanical layout.

The primary and secondary mirrors are bonded to mirror cells mounted on support plates at each end of the cage, with a spider-type secondary plate to reduce optical obstruction. An internal baffle supports the lens and detector assemblies while blocking stray light, eliminating the need for additional mounts. Integration involves mounting the mirrors and securing the baffle, with fine alignment adjustments made using precision shims. The onboard computer (OBC) and high-voltage power supply (HVPS) are enclosed in compact housings attached to the primary mirror plate, efficiently utilizing space. The assembled payload measures approximately 325 mm

4.1 Finite element analysis (FEA)

Performing structural analyses on any CubeSat model is crucial to ensure its reliability and survivability during launch and operation. Simulation tests, such as finite element analysis (FEA) that include static analysis, thermal analysis and modal analysis help identify potential structural weaknesses and optimize the design before manufacturing, reducing cost and preventing failures (Mathew et al., 2017; Li et al., 2014).

4.1.1 Frequency response (modal) analysis

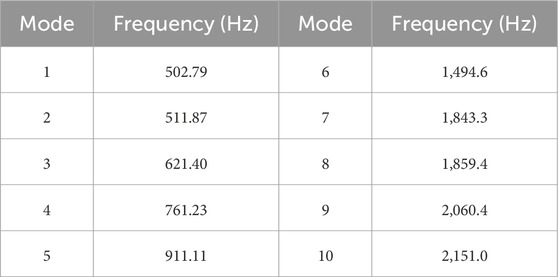

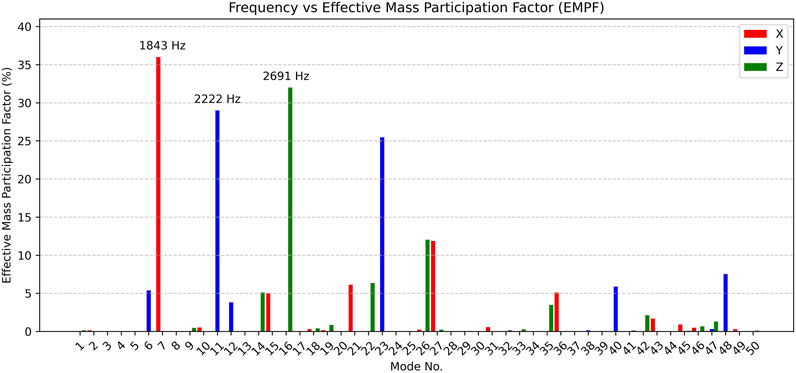

The dynamic response characteristics of the payload have been tailored to avoid resonance with the excitation profiles of the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV). As specified in the launcher’s guidelines, the system must exhibit primary resonant modes above 35 Hz in the longitudinal direction and 20 Hz in the lateral direction (Cihan et al., 2011; Raviprasad and Nayak, 2015). Additionally, during launches, significant harmonic frequencies occur below 100 Hz. To prevent resonance, the payload’s natural frequencies should ideally exceed 100 Hz (Raviprasad and Nayak, 2015). To verify mechanical stability, a modal analysis was performed on the NUTEx structural model using mechanical design software SolidWorks, including frequency versus Effective Mass Participation Factor (EMPF) and Cumulative Mass Participation Factor (CMPF) assessments. The first ten modal frequencies are listed in Table 5, with the first mode at approximately 500 Hz, well above the 100 Hz critical threshold, confirming structural adequacy. EMPF results, shown in Figure 7, reveal three dominant modes: Mode seven in the X-direction at 1843 Hz (36% participation), Mode 11 in the Y-direction at 2222 Hz (29%), and Mode 16 in the Z-direction at 2691 Hz (32%). The CMPF analysis up to the 50th mode shows dynamic participation of about 80% of the total mass, supporting the robustness of the cage-based design.

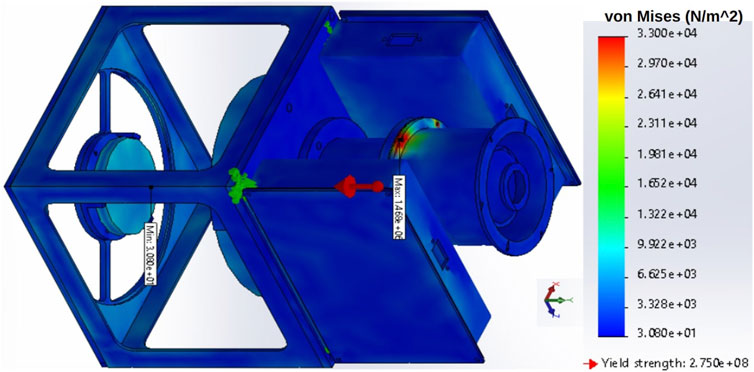

4.1.2 Static response analysis

Static structural analysis was performed to evaluate the response of the model under quasi-static loads representative of launch conditions. A static load of 25g was applied individually along the X, Y and Z-axes, and the resulting von Mises stress distributions were examined (Mathew et al., 2017). Figure 8 illustrates the stress distribution for the case when the load was applied in the Y direction, with the maximum and minimum stress locations marked. The maximum von Mises stress observed in this scenario was

5 Electronics subsystem

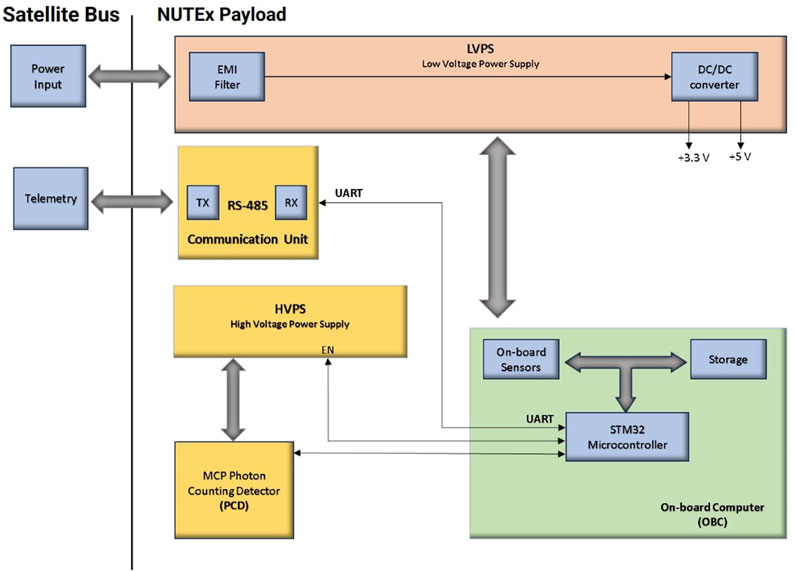

The electronics subsystem onboard a CubeSat is central to payload operations, handling data acquisition, storage, and communication with the satellite bus for command and telemetry. Recent advancements in COTS components enable the development of compact, low-cost, and power-efficient electronics tailored to specific mission needs. This has opened the way for deploying dedicated scientific instruments on resource-limited small satellite platforms. The electronics of NUTEx have been developed with these considerations in mind, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Block diagram of the NUTEx onboard electronics subsystem highlighting power, data handling, and communication interfaces.

The payload draws power from the satellite bus, which is down-converted to required voltage levels. The OBC, based on an STM32 microcontroller, follows a compact and modular design previously demonstrated in Ghatul et al. (2024), and can be adapted to NUTEx with minimal changes. Communication with the satellite bus uses an RS-485 interface, a UART-compatible protocol aligned with ISRO’s POEM platform on the PSLV (Bharat Chandra et al., 2024d).

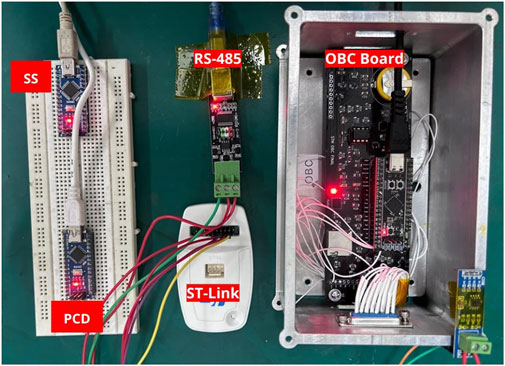

OBC and communication performance were validated using a laboratory setup (Figure 10). Two Arduino boards emulated data from peripheral devices such as the PCD and a potential star sensor (SS). The OBC hardware and software were verified by transmitting commands and receiving data via the integrated RS-485 interface.

Figure 10. Test setup for validating the onboard computer and RS-485 communication interface using simulated peripheral inputs.

6 Summary and development schedule

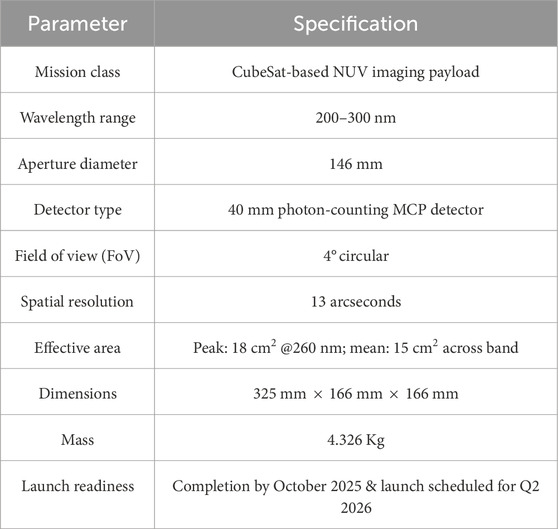

Scheduled for launch in Q2-2026, the NUTEx instrument is presented here with its optical design, science objectives, observing performance, and mechanical configuration. All optical components are manufactured, coated, and stored in a Class-1000 cleanroom, while mechanical elements are currently in fabrication and due for completion by October-2025. Assembly, integration, and calibration will be carried out at the MGKM Laboratory, Indian Institute of Astrophysics (CREST Campus), which previously supported the UVIT payload on AstroSat (Kumar et al., 2012). Both engineering and flight models will be built at this facility; the engineering model will undergo vibration and thermal-vacuum tests using the laboratory infrastructure. A full 3D-printed model of NUTEx was built and evaluated to verify the structural feasibility and integration compatibility of the design. The onboard electronics, including the OBC, power supply, and communication unit, have been developed in-house and will be further validated during system-level testing. Some of the key parameters of NTUEx are listed in Table 6.

NUTEx demonstrates a cost-effective approach to space-based NUV astronomy, enabling scientific observations at a fraction of the cost of larger facilities such as ULTRASAT (Shvartzvald et al., 2024). This affordability is made possible through a Raspberry Pi-based electronics architecture and the use of commercially available COTS components. As a pathfinder, NUTEx can inform the development of future constellations of small payloads to map the transient UV sky across the NUV and FUV bands. Its capability for extended observations of individual targets, lasting up to 6 months, broadens its scientific utility. The mission highlights how focused science goals can be addressed through compact platforms, providing a practical model for future instruments in this domain.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SG: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Data curation, Methodology. RM: Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review and editing. JM: Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review and editing. MS: Resources, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. PK: Software, Writing – review and editing. MG: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing. SJ: Writing – review and editing. SM: Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IIA), Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India.

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere gratitude to S. Sriram and P. U. Kamath of the Indian Institute of Astrophysics for their invaluable suggestions and assistance. Some of the data used in this study were obtained from the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST). The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., under NASA contract NAS5-26555, manages MAST. Support for non-Hubble data is provided by the NASA Office of Space Science through grant NNX09AF08G and other funding sources.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adilov, N., Alexander, P., Cunningham, B., and Albertson, N. (2022). An analysis of launch cost reductions for low Earth orbit. Econ. Bull. 42, 1561–1574. Available online at: https://ideas.repec.org/a/ebl/ecbull/eb-22-00204.html

Bharat Chandra, P., Nair, B. G., Ghatul, S. J., Babu S, M., Jain, S., Rai, R., et al. (2024a). Development of raspberry Pi-based processing unit for UV photon-counting detectors. J. Astronomical Instrum. 13, 2450005. doi:10.1142/S2251171724500053

Bharat Chandra, P., Nair, B. G., Ghatul, S. J., Jain, S., Mahesh Babu, S., Safonova, M., et al. (2024b). “Spectroscopic investigation of nebular gas (SING): instrument design, assembly and testing,”, 13093. SPIE: International Society for Optics and Photonics. doi:10.1117/12.3019583

Bharat Chandra, P., Nair, B. G., Ghatul, S. J., Jain, S., Sriram, S., Mahesh Babu, S., et al. (2024c). Spectroscopic investigation of nebular gas (SING): instrument design, assembly and calibration. Exp. Astron. 57, 18. doi:10.1007/s10686-024-09937-9

Bharat Chandra, P., Nair, B. G., Jain, S., Ghatul, S. J. S. M. B., Mohan, R., et al. (2024d). Low-cost raspberry Pi star sensor for small satellites. II: starberrysense flight and in-orbit performance. J. Astronomical Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 10, 026002. doi:10.1117/1.JATIS.10.2.026002

Brasseur, C. E., Osten, R. A., and Fleming, S. W. (2019). Short-duration stellar flares in galex data. Astrophysical J. 883, 88. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab3df8

Chevalier, R. A. (1992). Early expansion and luminosity evolution of supernovae. Astrophysical J. 394, 599. doi:10.1086/171612

Cihan, M., Çetın, A., Kaya, M. O., and İnalhan, G. (2011). “Design and analysis of an innovative modular cubesat structure for ITU-pSAT II,” in Proceedings of 5th international conference on recent advances in space technologies - rast2011, 494–499. doi:10.1109/RAST.2011.5966885

Clampin, M. (1997). Bright object protection mechanisms for STIS. Instrum. Sci. Rep. STIS 97-031 97-031, Space Telesc. Sci. Inst. Available online at: https://stsci.recollectcms.com/nodes/view/1947

Davenport, J. R. A. (2016). The kepler catalog of stellar flares. Astrophysical J. 829, 23. doi:10.3847/0004-637x/829/1/23

Douglas, E., Cahoy, K. L., Morgan, R. E., and Knapp, M. (2019). CubeSats for astronomy and astrophysics. Bull. Am. Astronomical Soc. 51, 160. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1907.07634

Evans, P. A., Cenko, S. B., Kennea, J. A., Emery, S. W. K., Kuin, N. P. M., Korobkin, O., et al. (2017). Swift and NuSTAR observations of GW170817: detection of a blue kilonova. Science 358, 1565–1570. doi:10.1126/science.aap9580

Ghatul, S., Bharat Chandra, P., Jain, S., Nair, B. G., Babu, M., Mohan, R., et al. (2024). “CubeOps: development of an STM32-based on-board computer (OBC) for small satellites and CubeSat missions,”, 13093. SPIE: International Society for Optics and Photonics. doi:10.1117/12.3027481

Ghosh, S. K., Joseph, P., Kumar, A., Postma, J., Stalin, C. S., Subramaniam, A., et al. (2021). In-orbit performance of UVIT over the past 5 years. J. Astrophys. Astron. 42, 20. doi:10.1007/s12036-020-09685-0

Jacklin, S., Lund, M. B., Pepper, J., and Stassun, K. G. (2015). TRANSITING PLANETS WITH LSST. II. PERIOD DETECTION OF PLANETS ORBITING 1M⊙HOSTS. Astron. J. 150, 34. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/150/1/34

Jones, H. W. (2018). “The Recent large reduction in space launch cost,” in 48th International Conference on Environmental Systems, 8-12 July 2018, Albuquerque, New Mexico (Albuquerque, NM: NASA ames Research Center).

Kumar, A., Ghosh, S., Hutchings, J., Kamath, P., Kathiravan, s., Mahesh, P., et al. (2012). Ultraviolet imaging telescope (UVIT) on ASTROSAT. Proc. SPIE 8443. doi:10.1117/12.924507

Li, Z., Chen, B., Song, K., Wang, X., Liu, S., Yang, L., et al. (2014). Opto-mechanisms Design of Extreme-ultraviolet camera Onboard Chang E lunar lander. Opt. Express 22, 15932–15940. doi:10.1364/OE.22.015932

Martin, D. C., Fanson, J., Schiminovich, D., Morrissey, P., Friedman, P. G., Barlow, T. A., et al. (2005). The galaxy evolution explorer: a space ultraviolet survey mission. Astrophysical J. 619, L1–L6. doi:10.1086/426387

Mathew, J., Prakash, A., Sarpotdar, M., Sreejith, A., Kj, N., Suresh, A., et al. (2017). Prospect for UV observations from the Moon. II. Instrumental design of an ultraviolet Imager LUCI. Astrophysics Space Sci. 362, 37. doi:10.1007/s10509-017-3010-6

Million, C. C., Clair, M. S., Fleming, S. W., Bianchi, L., and Osten, R. (2023). The GFCAT: a catalog of ultraviolet variables observed by GALEX with subminute resolution. Astrophysical J. Suppl. Ser. 268, 41. doi:10.3847/1538-4365/ace717

Morrissey, P., Schiminovich, D., Barlow, T. A., Martin, D. C., Blakkolb, B., Conrow, T., et al. (2005). The on-orbitperformance of the galaxy evolution explorer. Astrophysical J. 619, L7–L10. doi:10.1086/424734

Nakar, E., and Sari, R. (2010). Early supernovae light curves following the shock breakout. Astrophysical J. 725, 904–921. doi:10.1088/0004-637x/725/1/904

Ofek, E. O., Rabinak, I., Neill, J. D., Arcavi, I., Cenko, S. B., Waxman, E., et al. (2010). Supernova PTF 09UJ: a possible shock breakout from a dense circumstellar wind. Astrophysical J. 724, 1396–1401. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/724/2/1396

Polishook, D., Ofek, E. O., Waszczak, A., Kulkarni, S. R., Gal-Yam, A., Aharonson, O., et al. (2012). Asteroid rotation periods from the Palomar Transient Factory survey. MNRAS 421, 2094–2108. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.20462.x

Rabinak, I., and Waxman, E. (2011). The early uv/optical emission from core-collapse supernovae. Astrophysical J. 728, 63. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/728/1/63

Raviprasad, S., and Nayak, N. (2015). Dynamic analysis and verification of structurally optimized nano-satellite systems. J. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 1, 78–90. doi:10.17265/2332-8258/2015.02.005

Sagiv, I., Gal-Yam, A., Ofek, E. O., Waxman, E., Aharonson, O., Kulkarni, S. R., et al. (2014). Science with a wide-field uv transient explorer. Astronomical J. 147, 79. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/147/4/79

Shkolnik, E. L. (2018). On the verge of an astronomy CubeSat revolution. Nat. Astron. 2, 374–378. doi:10.1038/s41550-018-0438-8

Shvartzvald, Y., Waxman, E., Gal-Yam, A., Ofek, E. O., Ben-Ami, S., Berge, D., et al. (2024). ULTRASAT: a wide-field time-domain UV space telescope. Astrophysical J. 964, 74. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ad2704

Spence, H. E., Caspi, A., Bahcivan, H., Nieves-Chinchilla, J., Crowley, G., Cutler, J., et al. (2022). Achievements and lessons learned from successful small satellite missions for space weather-oriented research. Space weather. 20, e2021SW003031. doi:10.1029/2021sw003031

Srivastava, M. K., Prabhudesai, S. M., and Tandon, S. N. (2009). Studying the imaging characteristics of Ultra violet imaging telescope (UVIT) through numerical simulations. Publ. Astronomical Soc. Pac. 121, 621–633. doi:10.1086/603543

Waszczak, A., Prince, T. A., Laher, R., Masci, F., Bue, B., Rebbapragada, U., et al. (2017). Small near-earth asteroids in the palomar transient factory survey: a real-time streak-detection System. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 129, 034402. doi:10.1088/1538-3873/129/973/034402

Werner, N., Řípa, J., Thöne, C., Münz, F., Kurfürst, P., Jelínek, M., et al. (2024). Science with a small two-band uv-photometry mission i: mission description and follow-up observations of stellar transients. Space Sci. Rev. 220, 11. doi:10.1007/s11214-024-01048-3

Woellert, K., Ehrenfreund, P., Ricco, A. J., and Hertzfeld, H. (2011). Cubesats: cost-Effective science and technology platforms for emerging and developing nations. Adv. Space Res. 47, 663–684. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2010.10.009

Keywords: CubeSats, small payloads, UV instrumentation, imaging telescope, payload structure, mechanical design

Citation: Ghatul S, Mohan R, Murthy J, Safonova M, Kumar P, Gopinathan M, Jain S and Mahesh Babu S (2025) Near ultraviolet transient explorer (NUTEx): a CubeSat-based NUV imaging payload for transient sky surveys. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 12:1670437. doi: 10.3389/fspas.2025.1670437

Received: 21 July 2025; Accepted: 26 November 2025;

Published: 11 December 2025.

Edited by:

Cong Zhang, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

P. S. Athiray, University of Alabama in Huntsville, United StatesRudy Wijnands, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands

Copyright © 2025 Ghatul, Mohan, Murthy, Safonova, Kumar, Gopinathan, Jain and Mahesh Babu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shubham Ghatul, c2h1YmhhbS5qYW5raXJhbUBpaWFwLnJlcy5pbg==, c2h1YmhhbS5naGF0dWw0MUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Shubham Ghatul

Shubham Ghatul Rekhesh Mohan1

Rekhesh Mohan1 Margarita Safonova

Margarita Safonova Shubhangi Jain

Shubhangi Jain