- 1Department of Soil and Crop Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, United States

- 2Department of Horticultural Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, United States

- 3Grain Legume Genetics and Physiology Research Unit, USDA-ARS, Pullman, WA, United States

Sustainable food production is essential for long-duration Lunar missions, driving the development of in situ resource utilization strategies that use lunar regolith (LR) as a growth substrate for food crop cultivation. Although LR contains essential plant nutrients, it lacks organic matter and beneficial microbes. Its poor structure, low nitrogen content, and the presence of phytotoxic metals pose major challenges for plant germination, establishment, health, and successful fruit/seed production. On Earth, plant health and productivity are aided by microbial symbioses with mycorrhizal fungi, diazotrophic bacteria, and other rhizosphere colonizing organisms that facilitate nutrient availability, detoxify metals, and improve soil structure. This study evaluated 16 chickpea (Cicer arietinum) genotypes for seeding establishment, early plant development, and effective microbial symbiosis with rhizobia (Mesorhizobium ciceri) grown in vermicompost amended lunar regolith simulant (LRS) LHS-1. Chickpea is an ideal candidate for Lunar agriculture because it is a nutritionally dense food source and forms symbiotic relationships with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and rhizobia. Genotypes exhibited distinct growth strategies under LRS conditions, with considerable variation in total biomass production, differing by as much as 116 percent across genotypes, and in aboveground and belowground allocation. Notably, most genotypes showed strong nodulation with Mesorhizobium ciceri, suggesting potential for biological nitrogen fixation. These results inform breeding strategies for chickpea cultivars adapted to regolith-based systems and agriculture in challenging environments.

Introduction

Lunar regolith (LR), the predominant surface material on the Moon, is a complex mixture of mineral fragments, impact glass, and agglutinates. It contains the essential plant nutrients phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, iron, sulfur, manganese, and sodium, and in trace amounts, zinc, copper, and nickel. These elements are primarily derived from minerals such as plagioclase feldspar, pyroxenes, olivine, and glass, though most occur in mineral-bound forms with limited bioavailability (Demidova et al., 2007; Fackrell et al., 2024).

Unlike Earth soils, which are shaped by organic matter, microbial activity, and chemical and biological weathering, LR is not subjected to the processes that drive terrestrial soil formation (Heiken et al., 1991). LR consists of fine, angular particles, ranging from submicron dust to particles several millimeters in diameter that are abrasive in nature, generally hydrophobic, and carry a net positive surface charge due to constant exposure to solar wind and radiation (Carrier, 2003; Kunneparambil Sukumaran et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2025). These properties distinguish it from Earth’s dynamic soil systems and pose unique challenges for its use in space agriculture.

As a plant growth medium, LR presents several elemental constraints, particularly LR from the aluminum-rich highlands near the lunar south pole, which are the planned landing sites for upcoming Artemis missions (NASA, 2020). Aluminum is highly concentrated in highland regolith and is known to be phytotoxic at elevated levels (Papike et al., 1982). Iron, while essential in trace amounts, is also present in substantial quantities and may cause phytotoxicity depending on its concentration, oxidation state, and pH (Olaleye et al., 2001; Emamverdian et al., 2015). Other metals of concern include chromium (Cr) and titanium (Ti), which are significantly more abundant in basaltic mare regions and generally less problematic in the highlands. Hypothetically, the low concentrations of Ti typically found in highland regolith may be beneficial, as prior studies have shown that Ti can promote root development and enhance plant stress tolerance when leaf tissue levels remain below ∼15 mg kg-1 dry weight, or when applied at modest levels (e.g., 100–500 mg L-1) (Lyu et al., 2017; Šebesta et al., 2021). Although Cr and Ti may still occur in magnesium-rich lithologies, they are not the dominant toxicity drivers in highland regolith. Despite these challenges, the elemental composition, mineral content, and widespread availability of lunar regolith make it a practical base material for engineered substrates, provided it is amended through biological or physicochemical treatments to improve structure, increase nutrient accessibility, and reduce elemental toxicity and particle abrasiveness.

Studies have shown that plants can germinate and grow in lunar regolith collected during the Apollo missions; however, they exhibit physiological stress, including stunted growth and oxidative damage, and metabolic disruption, likely due to the regolith’s harsh physical and chemical properties (Paul et al., 2022). These findings highlight both the promise and the limitations of using LR for plant-based life support systems in extraterrestrial environments. To address these challenges, recent experiments using Lunar regolith simulants (LRS) have explored biological amendments to improve plant performance. For example, chickpeas have been successfully cultivated in 75% LRS amended with 25% vermicompost and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) achieving full growth cycles, though with signs of stress and delayed maturation (Atkin and Santos, 2024; Atkin, 2025). Vermicompost is produced through the activity of red wiggler earth worms (Eisenia fetida) and contributes both nutrient rich organic matter and microorganisms important for nutrient cycling. On Earth, mycorrhization has been associated with reduced elemental toxicity and improved substrate structure, suggesting a dual role in mitigating stress and enhancing growing conditions (Diagne et al., 2020; You et al., 2021; Abdelaal et al., 2024). Other studies have reviewed sustainable approaches for improving LRS fertility, emphasizing the role of microbiota and organic matter in transforming regolith into a viable growth medium (Duri et al., 2022; Fackrell et al., 2024). Together, these findings suggest that with appropriate treatment, regolith may be engineered into a functional substrate for space agriculture.

Seedling vigor is a strong predictor of adult plant performance and yield potential, particularly under abiotic stress (Reed et al., 2022). In the context of LRS, early plant development serves as a vital indicator of a genotype’s ability to tolerate multiple, overlapping constraints, including nutrient deficiencies, metal toxicity, poor aeration, compaction, and limited water availability. These initial stages are critical for establishing root system architecture, initiating microbial symbioses, and enabling effective resource acquisition, all of which are foundational to long-term plant survival and productivity. Seedling establishment serves not only as a practical screening metric but also as a predictive indicator of long-term adaptability to complex abiotic stress conditions. Identifying genotypes with strong early vigor accelerates the selection of crop lines suited to the unique pressures of regolith-based cultivation and supports the development of resilient plant systems for extraterrestrial agriculture.

Among candidate crops, leguminous plants like chickpea (Cicer arietinum) are particularly promising for space agriculture due to their high nutritional content, stress tolerance, and capacity to form beneficial symbioses with microorganisms: namely, rhizobia, which enable biological nitrogen (N) fixation, and AMF, which enhance nutrient uptake, increase substrate stability, and reduce elemental toxicity (Laranjeira et al., 2022; Yonas and Zawar, 2024). Although the Moon lacks an atmosphere and native nitrogen sources, future Lunar habitats with controlled nitrogen-containing environments could leverage these symbioses to fix atmospheric N2 via establishment with rhizobia (Leonard, 2005), minimizing the dependence on chemical fertilizers and fostering a more self-sufficient nutrient cycle. In addition to its symbiotic potential, chickpea is nutritionally dense, containing up to 22% protein, essential amino acids, iron, and other micronutrients that make it a valuable dietary component for long-duration space missions (Jukanti et al., 2012).

Previous studies have demonstrated that AMF consistently form symbioses with chickpea roots (genotype Myles) in LRS (unpublished). Despite chickpea’s potential for space agriculture, the capacity of diverse chickpea genotypes to establish seedlings, form nodules, and maintain effective symbioses under LRS conditions remains uncharacterized. This study addresses that gap by characterizing growth responses and nodulation capacity across multiple chickpea lines grown in vermicompost and AMF-amended LRS and inoculated with rhizobia (Mesorhizobium ciceri). In previous work (Atkin and Santos, 2024), vermicompost and AMF were required to produce healthy chickpea growth to seed and thus were included in the present study to ensure plants were healthy enough to form symbioses with rhizobia. By identifying genotypes with superior early vigor, establishment, and symbiotic efficiency in LRS, we lay the groundwork for breeding legume cultivars tailored to regolith-based cropping systems. These findings support not only sustainable in situ agriculture on the Moon, but also broader efforts to adapt legumes to extreme and degraded environments on Earth.

Results and discussion

The ability to establish root systems, engage with microbial symbionts, and access essential nutrients are critical for plant growth in LR for long-term survival and productivity in a lunar habitat (Lynch, 1995). Seedlings were grown in LRS amended with vermicompost and AMF to ensure the plants were healthy enough to form symbioses with rhizobia. All treatments except the control were inoculated with rhizobia. To assess seedling establishment and vigor, we evaluated biomass production and allocation patterns, SPAD relative chlorophyll content measurements and bacterial nodulation across 16 chickpea genotypes. These parameters collectively showcase the genetic variation in adaptability to the abiotic stressors in LRS.

Establishment

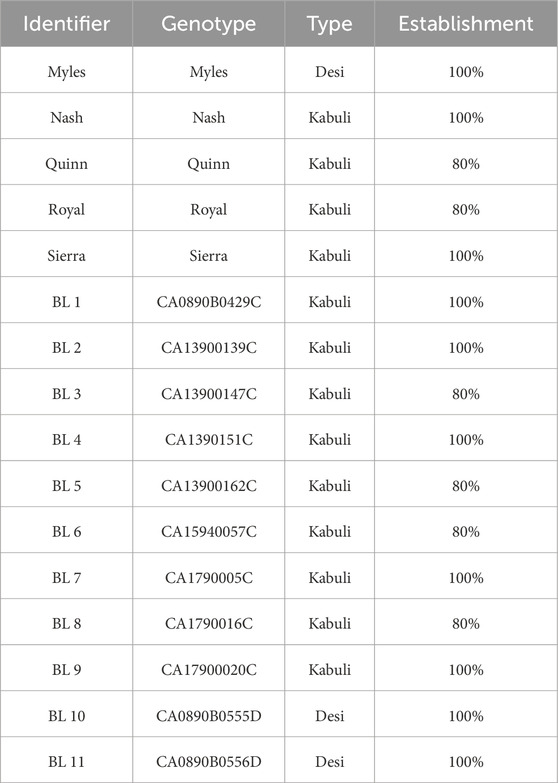

Germination and establishment in the vermicompost, AMF and rhizobia amended LRS was high, with many genotypes having 100% germination and survival to the end of the 30-day growth period (Table 1). Germination refers to the initial emergence of the radicle from the seed coat, while establishment denotes the successful transition to autotrophic growth and sustained seedling survival until harvest.

Table 1. Chickpea genotypes used in the study and their establishment data. The identifier indicates how each variety is referred to in this study. The set includes five released varieties and eleven breeding lines (BL) from the USDA Chickpea Diversity Panel; BL denotes unreleased varieties. Each genotype’s market type (Desi or Kabuli) is noted. Percent establishment represents the proportion of planted seeds that germinated, emerged, and survived to day 30.

Biomass

Biomass production and allocation patterns provide insight into how plants respond to environmental constraints, revealing tradeoffs between aboveground and belowground investment strategies (Poorter et al., 2012).

Total biomass captures cumulative growth outcomes and serves as a comparative metric of genotype performance under the tested conditions (Poorter et al., 2012). Aboveground allocation supports photosynthetic function and gas exchange, whereas belowground allocation facilitates water uptake, nutrient acquisition, and microbial symbioses. Root-shoot ratio provides a useful measure of allocation patterns.

At Day 30 (end of experiment), total biomass varied widely across genotypes (Figure 1A), with Quinn and several of the other Kabuli genotypes (BL 4, BL 5, BL 6, BL 8) generally producing the greatest total biomass. The difference between the smallest and largest values represented a 116 percent increase, highlighting substantial genotypic variation in growth performance under LRS conditions.

Figure 1. Dryweight biomass production and root–shoot allocation pattern of chickpea genotypes grown in amended LRS at day 30: (A) total, (B) aboveground, (C) belowground biomass, (D) root–shoot ratio. Biomass data are means of dry weight measurements with standard errors. Different letters denote significant differences among chickpea genotypes; treatments sharing the same letter are not significantly different (p < 0.05). Root-shoot ratio was calculated as below-ground dry weight/above-ground dry weight for individual plants. The individual root-shoot ratios were then averaged and the mean and standard error for each treatment is provided. The horizontal line at 1.0 indicates equivalent root and shoot production.

Aboveground biomass (Figure 1B), measured as dry shoot weight, averaged 0.67 g/plant across all genotypes. Quinn produced the greatest average aboveground biomass (0.97 ± 0.27 g/plant, mean ± standard error), and the same Kabuli genotypes with the greatest total biomass also were good canopy producers. Belowground biomass (Figure 1C) also varied widely, reflecting differences in genotype response to the structural and nutrient limitations of LRS. The same genotypes (Quinn, BL 4, BL 5, BL 6, BL 8) also generally produced the greatest root biomass, suggesting these lines did not sacrifice good root establishment for canopy production.

In terms of total biomass, many of the Kabuli genotypes grown in LRS mixture did as well as the Myles control grown in commercial potting mix with fertilization. However, nearly all genotypes produced as much or more root biomass than the Myles control (total biomass = 1.5 ± 0.2 g, above ground biomass = 1.2 ± 0.2 g, below ground biomass = 0.3 ± 0.1 g, root-shoot ratio = 0.3 ± 0.4). In the amended LRS with AMF and rhizobia symbionts, Myles plants were smaller, but allocated more of their production to root growth (root-shoot ratio = 0.8 ± 0.1).

Although many genotypes prioritized above ground production under LRS conditions, as indicated by root-shoot ratios less than 1.0 (Figure 1D), the Desi genotypes had more balanced allocation patterns (i.e., root-shoot ratios above 0.8). Only two genotypes, Royal and BL 1 had root-shoot ratios above 1, but neither of these were thriving in terms of biomass production. Despite some genotype-level trends, biomass allocation patterns did not converge on a single dominant strategy. This variability likely reflects high phenotypic plasticity in allocation, where biomass investment shifts in response to environmental inputs such as substrate structure, nutrient accessibility, or microbial signaling (Sultan, 2003). It should be noted that AMF colonization may contribute to differences in aboveground and belowground allocation patterns.

Across all biomass metrics, a consistent trend emerged: several of the Kabuli genotypes, including Quinn, BL 4, BL 5, BL 6, and BL 8 grew well as indicated by their total, aboveground, and belowground biomass production, making them the most well-rounded performers under LRS conditions. Quinn is the most recent (2021) chickpea variety developed by USDA and was released based on its consistently high yield and large seed size across multiple years and locations in Idaho and Washington. Given its balanced allocation pattern and consistent performance, Quinn represents a promising candidate for plant breeding efforts to improve productivity in challenging terrestrial environments and lunar-based agriculture. The other breeding lines also appear promising, suggesting that multiple lines may offer genetic potential for optimizing plant performance in extreme or resource-limited systems. Among the Desi genotypes Myles performed about the same as the two breeding lines in the amended LRS.

Biological nitrogen fixation

Lunar agriculture will require a habitat containing an Earth-like atmosphere, including nitrogen, such as used on the International Space Station (Leonard, 2005). Consequently, biological nitrogen fixation could be a vital contributor to successful Lunar agriculture. The ability of chickpea genotypes to engage effectively with rhizobia would reduce the need for synthetic nitrogen inputs and reflects a broader capacity for microbial symbiosis to add nitrogen to the system. Thus, the formation of effective legume:rhizobia symbioses is important for both legume adaptation and the bioremediation of extraterrestrial regolith.

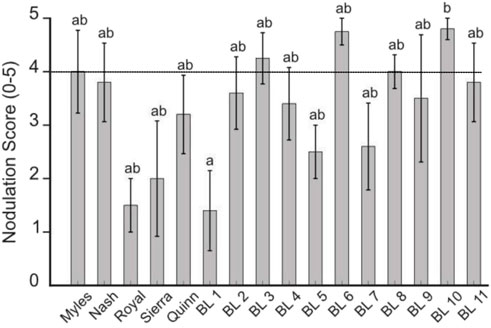

Nodulation was scored on a 0 to 5 scale, with 0 indicating no nodulation and 5 representing extensive bacterial colonization (Unkovich et al., 2005). Briefly, the system considers nodule number, size, pigmentation and distribution. Nodules from each root were cut open to determine active biological nitrogen fixation, with pink internal pigmentation indicating leghemoglobin production within the nodule for active nitrogenase activity (Ott et al., 2005). Nodules formed on all genotypes and nodulation scores ranged from 2.5 to 4.8 (Figure 2). Most genotypes displayed good nodulation (i.e., nodulation score of 4 or greater) which corresponds to abundant, well-distributed, pink nodules indicative of effective symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Two of the genotypes with the poorest nodulation scores (Royal and BL 1) also had the highest root-shoot ratios (suggesting poor canopy development) and were among the smallest plants.

Figure 2. Nodulation scores (0–5) of chickpea genotypes inoculated with rhizobia and grown in amended LRS at day 30. Different letters denote significant differences among chickpea genotypes; treatments sharing the same letter are not significantly different (p < 0.05). The horizontal line indicates a nodulation score of 4.0. Many genotypes displayed good nodulation (i.e., scores ≥ 4).

Although some of the best biomass producers also had nodulation scores above 4 (BL 6, BL 8), this was not a consistent trend, with Quinn and BL 5 having more modest scores. Additionally, despite modest performance in biomass metrics even compared to the other Desi varieties, BL 10’s superior nodulation suggests a strong potential for supporting closed-loop nitrogen cycling. Its consistent partnership with nitrogen-fixing microbes makes it a valuable line for reducing input requirements and supporting plant productivity in controlled environments. BL 10, and similar performers, e.g., BL 6, BL 8 are promising candidates for breeding programs aimed at enhancing biological nitrogen fixation and broader microbial symbiosis, both of which are essential for sustainable legume cultivation in extraterrestrial systems.

Nitrogen status

Leaf greenness, measured non-destructively using a Soil Plant Analysis Development (SPAD) meter, is a well-established proxy for nitrogen status and photosynthetic capacity in plants. In chickpea, higher SPAD values have been linked to improved drought tolerance and nitrogen acquisition, particularly in semi-arid environments. Our SPAD meter operates on a 0–100 scale, with values above 45 generally indicating healthy chlorophyll content and physiological resilience (Parry et al., 2014). Given LR’s significant limitations, including anhydrous conditions, poor structure, and lack of organic nutrients, these traits are especially relevant for Lunar agriculture.

Many genotypes achieved SPAD values within the range considered optimum for plant health (i.e., ≥45), with BL 3 and BL 8 generally having the highest average SPAD values (Figure 3). These results suggest that many of the genotypes were able to establish and maintain a relatively healthy green canopy having good plant nitrogen status and capacity to sustain photosynthetic activity under stress to harvest. These findings reveal the potential of many of these genotypes as foundational material for breeding programs focused on improving stress resilience, which is critical not only for systems in Lunar agriculture but also for resource-limited regions on Earth, where water scarcity and poor soil structure constrain legume productivity.

Figure 3. SPAD values measured on day 30 across chickpea genotypes grown in amended LRS. Data represent means ± standard errors. Different letters denote significant differences among chickpea genotypes; treatments sharing the same letter are not significantly different (p < 0.05). SPAD readings serve as a proxy for leaf nitrogen status and photosynthetic capacity. The horizontal line indicates a SPAD value of 45.

Of note, leaf greenness at day 30 did not correlate well with nodulation or total biomass production in this study. Initially, we hypothesized that plants with the best nodulation would have the best nitrogen status. Of the 10 genotypes with nodulation scores over 4, only 4 genotypes (Nash, BL 3, BL 4, and BL 8) had mean SPAD values above 45 and two genotypes with the poorest nodulation scores (Royal and BL 1) had mean SPAD scores above 45. Additionally, although Quinn and BL 5 produced substantial total biomass, they had comparatively moderate nodulation and SPAD values, whereas BL 3 displayed some of the highest mean SPAD values and had good nodulation but lower biomass accumulation. The disconnect between SPAD measurements, nodulation, and plant production suggest that single time point SPAD measurements at harvest are not good predictors of biological nitrogen fixation or plant growth that took place over the course of the entire study. We suggest that because SPAD measurements are nondestructive, measurements at earlier time points could yield more useful information to more fully capture integrated growth responses across the entire experimental period. We note that given the dissected nature of the compound leaves, SPAD measurements are somewhat challenging to perform.

Conclusion

Building on the optimal substrate composition identified in our previous study, we amended LRS with vermicompost (25% based on weight) and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Atkin and Santos, 2024), and inoculated with rhizobia to create a biologically active, low-input growth medium for evaluating chickpea genotype performance. Our findings highlight genotype-specific strategies for adaptation to LRS conditions, with distinct advantages in biomass partitioning, microbial symbiosis, nitrogen acquisition, and leaf nitrogen maintenance (Figure 4). Several of the Kabuli lines including Quinn, BL 4, BL 5 and BL 6, BL 8 consistently grew well as indicated by their total, aboveground, and belowground biomass production, positioning them as strong candidates for general-purpose cultivation. Most genotypes displayed good nodulation (i.e., nodulation score of 4 or greater) in LRS, including all of the Desi genotypes, with BL 10 having the highest average score. This finding demonstrates the potential for strong microbial symbiosis and efficient nitrogen acquisition in LRS, key traits for low-input systems where fertilizers are limited. Many genotypes achieved SPAD values within the range considered optimum for plant health with BL 3 and BL 8 generally having the highest average SPAD values. These findings highlight the ability of many of the genotypes tested to establish and maintain a canopy having good plant nitrogen status and capacity to sustain photosynthetic activity under stress. Together, these lines offer complementary strengths that support different strategies for maintaining productivity in extreme environments.

Figure 4. Comparative plant morphology at day 30 of chickpea genotypes grown in amended LRS compared to the Myles control. The genotypes shown include the control (Myles grown in commercial potting mix) along with genotypes that performed well in terms of biomass production (Quinn), rhizobial nodulation (BL 10) or SPAD measurement of greenness (BL 3).

Given that seedling vigor is a strong predictor of adult plant performance, our findings highlight the potential of these chickpea genotypes for full-term success in lunar-based agriculture. This study has provided a foundation for developing legume cultivars optimized for extreme environments by identifying genotypes with superior establishment, vigor, and microbial synergism. Future work should explore the genetic and physiological mechanisms underlying these traits and how microbial symbioses and substrate engineering could maximize genotype performance and sustainability in space-based cropping systems.

Materials and methods

Genotypes and market types

A set of 16 Cicer arietinum (chickpea) genotypes were selected from the USDA Chickpea Diversity Panel: five named cultivars and eleven USDA breeding lines (BL) (Table 1). Entries included both major market types of chickpea: ‘Desi’, which have purple flowers and a ‘teardrop’ shaped seed with a pigmented seed coat, and ‘Kabuli’, which have white flowers and produce seed with a light beige seed coat that have a ‘rams head’ shape and tend to be larger than Desi chickpeas (Toker, 2009).

Experimental design

The experiment was conducted in a climate-controlled growth chamber maintained at 25 °C day/night. The light intensity was set at 200 μmol m-2 s-1 with a photoperiod of 14 h light and 10 h dark over a 30-day growth period. Each genotype was replicated five times within a randomized complete block design. Due to the limited availability of authentic lunar regolith, a commercial lunar regolith simulant (LRS) was used to replicate the chemical and physical characteristics of lunar surface materials. Specifically, LHS-1 (Exolith Lab, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL) was selected based on its mineral profile and particle size distribution (Space Resource Technology, 2025) (Supplementary Table S1). The simulant was mixed with vermicompost (Black Diamond Vermicompost, Paso Robles, CA) at a 75:25 weight ratio (LRS:vermicompost) to enhance organic content, biological activity, and nutrient availability. The bulk densities of LRS and vermicompost were 1.3 g/cm3 and 0.39 g/cm3, respectively.

Five seeds per genotype were planted in a mixture of 75:25 LRS:vermicompost (pH 6.4). As an establishment control, five seeds of Myles were planted in 100% commercial potting mix (Miracle-Gro Performance Organics All Purpose In Ground Soil, Scotts Miracle-Gro, Marysville, OH). Genotype Myles was chosen as the control because it is a well-known commercial variety we used in previous studies. Plants were evaluated for effects following 21 days after 50% emergence of the seedlings in the control group according to test number 208: Terrestrial Plant Test (OECD, 2006). Endpoints measured are visual assessment of seedling emergence, biomass measurements, shoot height, and SPAD readings. All plants were cultivated in Ray Leach Cone-tainers (3.8 cm diameter × 25 cm depth, Stuewe and Sons, Tangent, OR), which provide sufficient rooting depth for early-stage chickpea development. Seeds were surface-sterilized in 5% sodium hypochlorite for 1 min, rinsed twice with deionized water, and blot-dried. Prior to planting, seeds were inoculated with a commercial arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) blend (MycoApply Ultrafine Endo, Mycorrhizal Applications, Grants Pass, OR) containing Glomus intraradices, Glomus mosseae, Glomus aggregatum, Glomus etunicatum and the nitrogen-fixing rhizobia Mesorhizobium ciceri (Exceed Peat Garbanzo Bean, Visjon Biologics, Henrietta, TX) as a seed coating at twice the manufacturer’s recommended rate, to mitigate early-stage microbial inhibition due to potential LRS toxicants.

A single seed was sown per Cone-tainer at a depth of approximately 4 cm. Plants were watered immediately after sowing, again on day two, and then every other day using a bottom-wick irrigation system. The wicking setup consisted of 6.35 mm cotton cords connected to water reservoirs, allowing passive and consistent moisture delivery. The control group was watered (also using the wick method) with a nutrient solution containing 75 mg L-1 nitrogen and other essential nutrients, prepared using an all-purpose water-soluble fertilizer (12N–1.75P–13.3K; Jack’s Nutrients FeED 12–4–16 RO; JR Peters, Inc., Allentown, PA) dissolved in deionized water, with an additional 10 mg L-1 sulfur supplied as magnesium sulfate (MgSO4.7H2O).

Immediately before harvest, a SPAD-502 Plus chlorophyll meter (Soil and Plant Analysis Development optical device, Spectrum Technologies, Inc., Aurora, IL) was used to non-destructively assess the nitrogen status of the plant by determining the intensity of leaf greenness. Measurements targeted the youngest fully expanded leaves within the lower 5 cm of the canopy. At harvest, plants were extracted and gently rinsed with tap water to remove residual substrate. Shoot height was measured from the second node to the apex of the highest leaf. Above-ground dryweight biomass (from the first node upward) and below-ground dryweight biomass (from the first node and below) were collected, photographed, dried at 55 °C for 24 h, and weighed. Root: shoot ratio was calculated as below-ground dry weight/above-ground dry weight for individual plants. The individual root-shoot ratios were then averaged and the mean and standard error for each treatment is provided. Nodulation frequency was assessed visually on a 0–5 scale (where 0 = no nodules and 5 = extensive nodulation across the root system using a method described in (Unkovich et al., 2005). Briefly, the system considers nodule number, size, pigmentation and distribution. The nodule score is determined by the number of effective nodules in the crown-root zone (i.e., the region up to 5 cm below the first lateral roots) and secondarily on deeper parts of roots. Whole plant images were produced via the merger of the separate consistently proportioned images of root and shoot biomass using Microsoft Designer.

Statistics

Normality and equality of variance were tested using Assumption Checks, JASP software (JASP Version 0.19.3, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way and two-way ANOVA to evaluate genotype and substrate effects. Post-hoc means separation was performed using Tukey’s HSD to identify significant pairwise differences using JASP software. Compact letter displays (a, b, and ab) were generated using MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA, United States) to aid in the interpretation of statistically significant differences among treatments.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. HAS: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review and editing. EAP: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review and editing. SZ: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review and editing. GV: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. TG: Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the United States Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS) under a Non-Assistance Cooperative Agreement [Project Number: 2090-21000-038-013-S], as part of the project Chickpea seedling vigor in simulated lunar regolith and the USDA NIFA Hatch program [Project 8092-0]. The work was conducted at Texas A&M University in collaboration with the Grain Legume Genetics Physiology Research Unit, USDA-ARS, Pullman, WA.

Acknowledgements

We thank Vision Biologics (Henrietta, TX), makers of Exceed, for providing the rhizobia microbial inoculant used in this study. We thank Cristy Christie of Black Diamond Vermicompost for supplying vermicompost materials. We also thank the Zhen Lab for their collaboration, and Jasmine Goode for her assistance with data collection at harvest.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fspas.2025.1670807/full#supplementary-material

References

Abdelaal, K., Alaskar, A., and Hafez, Y. (2024). Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on physiological, bio-chemical and yield characters of wheat plants (Triticum aestivum L.) under drought stress conditions. BMC Plant Biol. 24, 1119. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-05824-9

Atkin, J. (2025). Using fungi for the bioremediation of lunar regolith. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 6, 550. doi:10.1038/s43017-025-00691-w

Atkin, J. A., and Santos, S. O. (2024). From dust to seed: a lunar chickpea story. doi:10.1101/2024.01.18.576311

Carrier, W. D. (2003). Particle size distribution of lunar soil. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 129, 956–959. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(2003)129:10(956)

Demidova, S. I., Nazarov, M. A., Lorenz, C. A., Kurat, G., Brandstätter, F., and Ntaflos, Th. (2007). Chemical composition of lunar meteorites and the lunar crust. Petrology 15, 386–407. doi:10.1134/S0869591107040042

Diagne, N., Ngom, M., Djighaly, P. I., Fall, D., Hocher, V., and Svistoonoff, S. (2020). Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on plant growth and performance: importance in biotic and abiotic stressed regulation. Diversity 12, 370. doi:10.3390/d12100370

Duri, L. G., Caporale, A. G., Rouphael, Y., Vingiani, S., Palladino, M., De Pascale, S., et al. (2022). The potential for lunar and Martian regolith simulants to sustain plant growth: a multidisciplinary overview. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 8, 747821. doi:10.3389/fspas.2021.747821

Emamverdian, A., Ding, Y., Mokhberdoran, F., and Xie, Y. (2015). Heavy metal stress and some mechanisms of plant defense response. Sci. World J. 2015, 756120. doi:10.1155/2015/756120

Fackrell, L. E., Humphrey, S., Loureiro, R., Palmer, A. G., and Long-Fox, J. (2024). Overview and recommendations for research on plants and microbes in regolith-based agriculture. Npj Sustain. Agric. 2, 15. doi:10.1038/s44264-024-00013-5

Heiken, G. H., Vaniman, D. T., and French, B. M. (1991). Lunar sourcebbook: a user’s guide to the moon.

Jukanti, A. K., Gaur, P. M., Gowda, C. L. L., and Chibbar, R. N. (2012). Nutritional quality and health benefits of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.): a review. Br. J. Nutr. 108, S11–S26. doi:10.1017/S0007114512000797

Kunneparambil Sukumaran, A., Zhang, C., Nisar, A., and Agarwal, A. (2024). Recent trends in tribological performance of aerospace materials in lunar regolith environment – a critical review. Adv. Space Res. 73, 846–869. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2023.10.039

Laranjeira, S., Reis, S., Torcato, C., Raimundo, F., Ferreira, L., Carnide, V., et al. (2022). Use of plant-growth promoting rhizobacteria and mycorrhizal fungi consortium as a strategy to improve chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) productivity under different irrigation regimes. Agronomy 12, 1383. doi:10.3390/agronomy12061383

Leonard, D. J. (2005). International space station (ISS) nitrogen and oxygen logistics; predictions verses actuals. 1 2896. doi:10.4271/2005-01-2896

Lynch, J. (1995). Root architecture and plant productivity. Plant Physiol. 109, 7–13. doi:10.1104/pp.109.1.7

Lyu, S., Wei, X., Chen, J., Wang, C., Wang, X., and Pan, D. (2017). Titanium as a beneficial element for crop production. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 597. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.00597

NASA (2020). Artemis plan: NASA’s lunar exploration program overview. Available online at: https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/artemis_plan-20200921.pdf.

OECD (2006). Test No. 208: terrestrial plant test: seedling emergence and seedling growth test. Paris: OECD. doi:10.1787/9789264070066-en

Olaleye, A. O., Tabi, F. O., Ogunkunle, A. O., Singh, B. N., and Sahrawat, K. L. (2001). Effect of toxic iron concentrations on the growth of lowlands rice. J. Plant Nutr. 24, 441–457. doi:10.1081/PLN-100104971

Ott, T., Van Dongen, J. T., Gu¨nther, C., Krusell, L., Desbrosses, G., Vigeolas, H., et al. (2005). Symbiotic leghemoglobins are crucial for nitrogen fixation in legume root nodules but not for general plant growth and development. Curr. Biol. 15, 531–535. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.042

Papike, J. J., Simon, S. B., and Laul, J. C. (1982). The lunar regolith: chemistry, mineralogy, and petrology. Rev. Geophys. 20, 761–826. doi:10.1029/RG020i004p00761

Parry, C., Blonquist, J. M., and Bugbee, B. (2014). In situ measurement of leaf chlorophyll concentration: analysis of the optical/absolute relationship. Plant Celland Environ. 37, 2508–2520. doi:10.1111/pce.12324

Paul, A.-L., Elardo, S. M., and Ferl, R. (2022). Plants grown in apollo lunar regolith present stress-associated transcriptomes that inform prospects for lunar exploration. Commun. Biol. 5, 382. doi:10.1038/s42003-022-03334-8

Poorter, H., Niklas, K. J., Reich, P. B., Oleksyn, J., Poot, P., and Mommer, L. (2012). Biomass allocation to leaves, stems and roots: meta-analyses of interspecific variation and environmental control. New Phytol. 193, 30–50. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03952.x

Reed, R. C., Bradford, K. J., and Khanday, I. (2022). Seed germination and vigor: ensuring crop sustainability in a changing climate. Heredity 128, 450–459. doi:10.1038/s41437-022-00497-2

Šebesta, M., Ramakanth, I., Zvěřina, O., Šeda, M., Diviš, P., and Kolenčík, M. (2021). “Effects of titanium dioxide nanomaterials on plants growth,” in Nanotechnology in plant growth promotion and protection. Editor A. P. Ingle (Wiley), 17–44. doi:10.1002/9781119745884.ch2

Space Resource Technology (2025). LHS-1 lunar highlands simulant fact sheet. Available online at: https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0398/9268/0862/files/lhs-1-spec-sheet-Jun2025-house-basalt.pdf?v=1753368205.

Sultan, S. E. (2003). Phenotypic plasticity in plants: a case study in ecological development. Evol. Dev. 5, 25–33. doi:10.1046/j.1525-142X.2003.03005.x

Toker, C. (2009). A note on the evolution of kabuli chickpeas as shown by induced mutations in Cicer reticulatum Ladizinsky. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 56, 7–12. doi:10.1007/s10722-008-9336-8

Unkovich, M., Herridge, D., Peoples, M., Cadisch, G., Boddey, B., Giller, K., et al. (2005). Measuring plant-associated nitrogen fixation in agricultural systems.

Yonas, M. W., and Zawar, S. (2024). Optimizing chickpea growth: unveiling the interplay of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and rhizobium for sustainable agriculture. Soil Use Manag. 40, e13057. doi:10.1111/sum.13057

You, Y., Wang, L., Ju, C., Wang, G., Ma, F., Wang, Y., et al. (2021). Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on the growth and toxic element uptake of Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud under zinc/cadmium stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 213, 112023. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112023

Keywords: lunar regolith simulant, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, rhizobia, chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.), breeding - genetic variations and germplasm development, in situ resource utilisation (ISRU)

Citation: Atkin J, Skabelund H, Pierson E, Zhen S, Vandemark GJ and Gentry T (2025) Genotype selection and microbial partnerships influence chickpea establishment in lunar regolith simulant. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 12:1670807. doi: 10.3389/fspas.2025.1670807

Received: 22 July 2025; Accepted: 30 October 2025;

Published: 09 December 2025.

Edited by:

Suniti Karunatillake, Louisiana State University, United StatesReviewed by:

David G. Mendoza-Cozatl, University of Missouri, United StatesVikram Singh, Amrapali University, India

Sashidhar Burla, ATGC Biotech Private Limited, India

Copyright © 2025 Atkin, Skabelund, Pierson, Zhen, Vandemark and Gentry. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jessica Atkin, amF0a2luQHRhbXUuZWR1

Jessica Atkin

Jessica Atkin Hikari Skabelund

Hikari Skabelund Elizabeth Pierson

Elizabeth Pierson Shuyang Zhen

Shuyang Zhen George J. Vandemark

George J. Vandemark Terry Gentry

Terry Gentry