- 1Planetary Environmental and Astrobiological Research Laboratory, School of Atmospheric Sciences, Sun Yat-sen University, Zhuhai, China

- 2Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

- 3Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Munich, Germany

Cold plasma of ionospheric origin, with energies less than a few tens of electronvolts, dominates the plasma population in the magnetosphere and plays a crucial role in magnetospheric dynamics. Although the velocity distribution of cold plasma in the magnetotail is measured, little is known about the changes in its temperatures because of the difficulty in directly measuring the cold plasma. In this study, we examine the electric field measurements in the plasma wake, which is created by charged spacecraft interacting with the cold plasma flow, to infer the changes in the electron-to-ion temperature ratio of the cold plasma. We present observations from the Cluster mission during the years 2001–2010 and the distributions of the observed electric potential decrease in the plasma wake. The results confirm the correlation between the wake potential and the plasma flow speed and indicate that the electron-to-ion temperature ratio of the cold plasma decreases with increasing geocentric distance, suggesting that electrons are heated differently from ions as the cold plasma is transported into the tail.

1 Introduction

The plasma in the Earth’s magnetotail lobes primarily originates from the ionospheric polar wind, consisting of ions and electrons with energies and temperatures below a few tens of electronvolts (André et al., 2015; Engwall et al., 2009), and is often referred to as cold plasma. Ions in the cold plasma are accelerated by an ambipolar electric field generated by faster moving electrons (Axford, 1968; Collinson, 2024) in the topside ionosphere and escape together with electrons along the open field lines of the polar region. Cold plasma has been confirmed (Haaland et al., 2012; Nilsson et al., 2010) to be further accelerated by the centrifugal force in the tail lobes as it flows into the tail.

The lobe magnetic fields that connect the tail and the ionosphere act as a waveguide for Alfvén waves. Alfvén waves in the lobes are known to interact with ionospheric outflow (Keiling et al., 2005; Takada et al., 2006; Sauvaud et al., 2004); it remains unclear how significantly the electrons and ions of the cold outflowing plasma are heated. To address this question, it is important to measure the electron-to-ion temperature ratio of cold plasma.

The main difficulty in measuring the cold ion temperature arises from the spacecraft’s electric potential, which is normally positive for spacecraft in a sunlit and tenuous plasma environment. The spacecraft’s potential is large enough to repel cold ions, preventing them from being measured using the ion spectrometers onboard the spacecraft.

An alternative is to use the in situ electric field measurements. As the cold plasma has a bulk kinetic energy larger than its thermal energy, it is often supersonic in the lobes. When a spacecraft encounters the cold plasma in the lobes, a plasma wake downstream of the spacecraft with an imbalanced electric charge distribution is formed. For more details on the plasma wake, we refer to André et al. (2021).

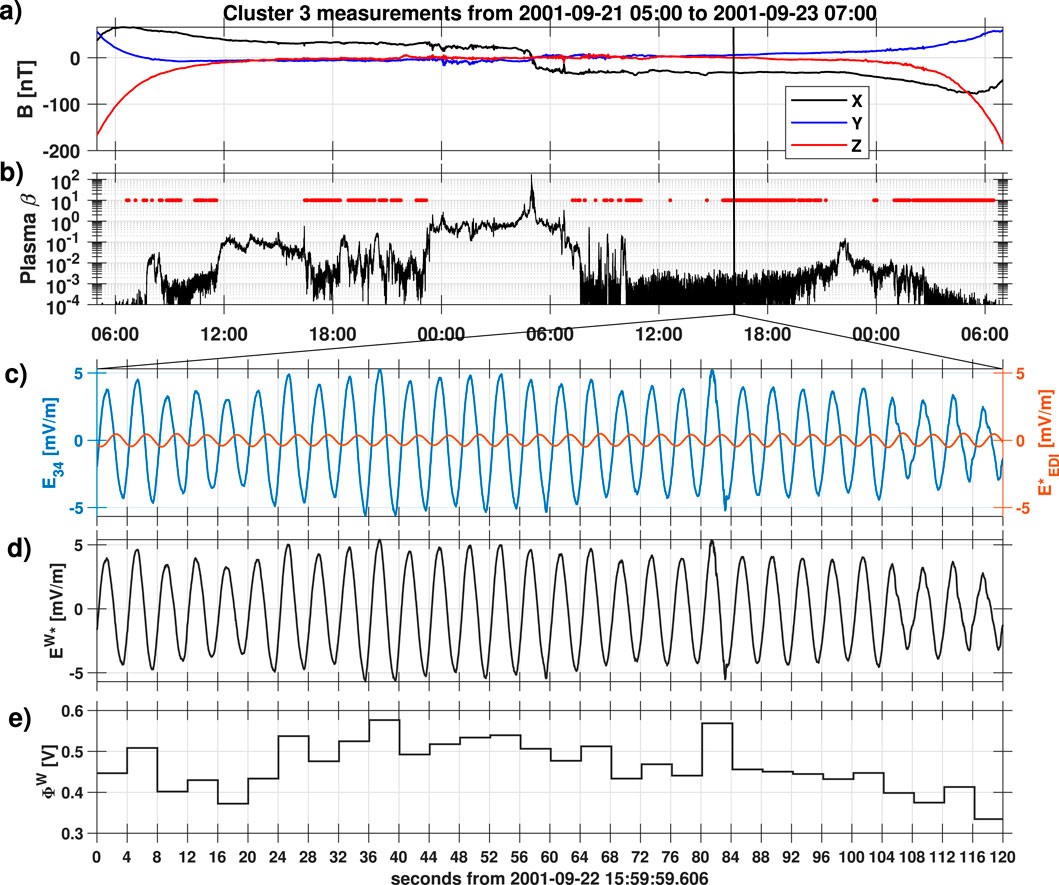

Figure 1 shows the examples of wake detection during a lobe crossing by Cluster 3. Figure 1a shows the magnetic field measurements made using the fluxgate magnetometer (FGM) (Balogh et al., 2001). From the X-component of the B-field, it is observed that the spacecraft moved from the northern lobe to the central plasma sheet before joining the southern lobe. Figure 1b shows the plasma

Figure 1. Example of plasma wake detection during a lobe crossing by Cluster 3. (a) In situ magnetic field in the Geocentric Solar Ecliptic coordinates measured using the FGM instrument. (b) Plasma beta calculated from the CIS data (black curve) and periods in which the plasma wake was detected (red dots). (c) Electric fields measured using the EFW (spacecraft-scale) and the EDI (background). (d) Electric field derived from the differences in the measurements between the two electric field instruments

The wake detection relies on observations from the electric-field and wave experiment (EFW) (Gustafsson et al., 1997) and the electron drift instrument (EDI) (Paschmann et al., 2001) onboard the Cluster spacecraft. Figures 1c–e show the electric-field measurements during a period of the lobe crossing that is marked by the vertical lines in Figures 1a,b. As the probe pair of EFW co-rotates with the spinning Cluster spacecraft, the potential difference between the two probes separated by 88 m produces a periodic signal. The electric field between probes 3 and 4

Following Engwall et al. (2006) and André et al. (2015), the wake electric field is identified when the maximal discrepancy between two instruments

2 Inferring the temperature ratio from the wake depth measurements

This section summarizes the main factors that affect the wake depth measurements and show how the temperature ratio is inferred.

2.1

For simplicity, we first consider the situation under which a spacecraft has a neutral surface charge. According to theoretical calculations by Alpert et al. (1965) and André et al. (2021), the wake depth is influenced by the ion flow Mach number (M):

where

2.2

The wake depth is also influenced by the electron-to-ion temperature ratio of the background plasma

Engwall et al. (2006) carried out numerical simulations using a constant

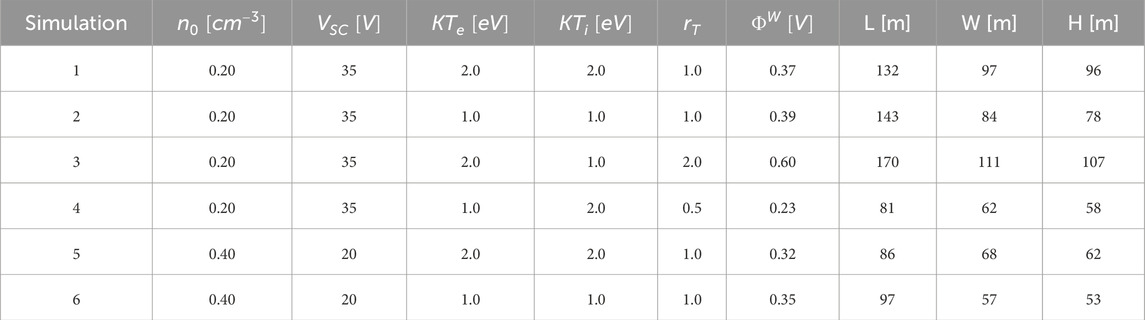

Table 1. Values of

Their simulations indicate that

Therefore,

The dataset derived from the Cluster mission contains the measurements of

3 Data

The cold ion dataset used in this study includes measurements of the wake electric field, which has been used to derive the bulk flow velocity of ions with energies of a few tens of eV. For details of the dataset, we refer to Engwall et al. (2009) and André et al. (2015). Numerous studies have used this dataset to investigate the characteristics of the ionospheric outflow. For a comprehensive overview of the wake method and related research, we refer readers to the reviews by André et al. (2021) and Li et al. (2021).

The data include both the wake depth

To ensure that the plasma flow lies in the spin plane and that the measurement of the wake depth is reliable, we used a maximum elevation angle

4 Results

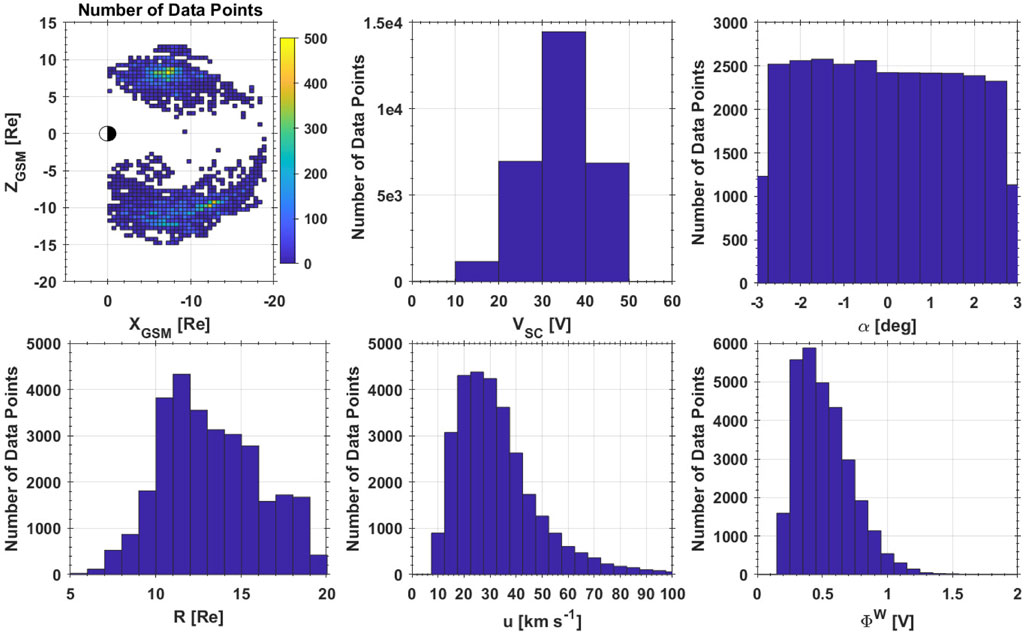

Figure 2 shows the distributions of the selected data. Measurements were made in a large part of the tail lobes, with values of

4.1 Effects of

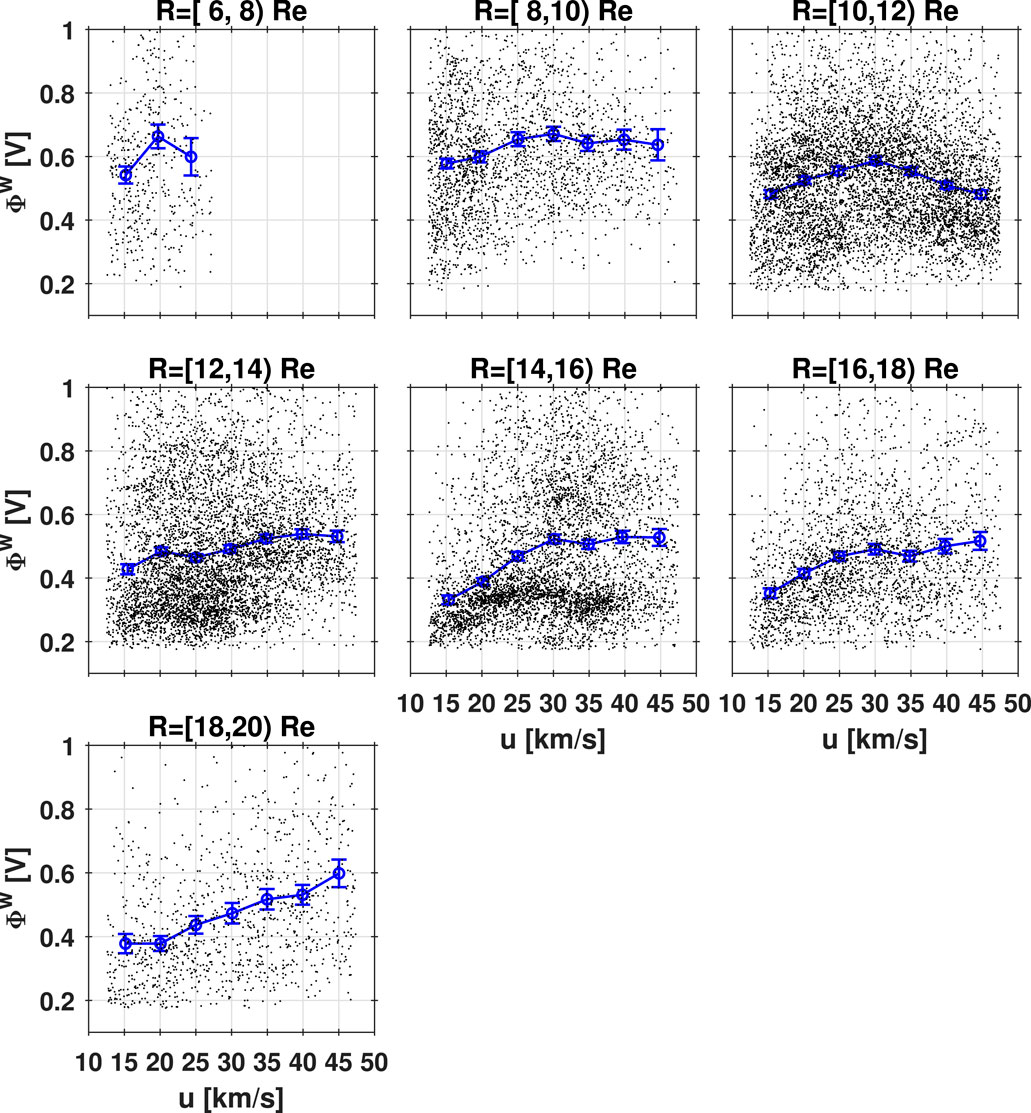

Figure 3 shows the measured

Figure 3. Correlation between

The positive correlation between

4.2 Correlation between

Since the spacecraft acquired a positive electric potential, the size of the wake observed in our study is enhanced. In addition to

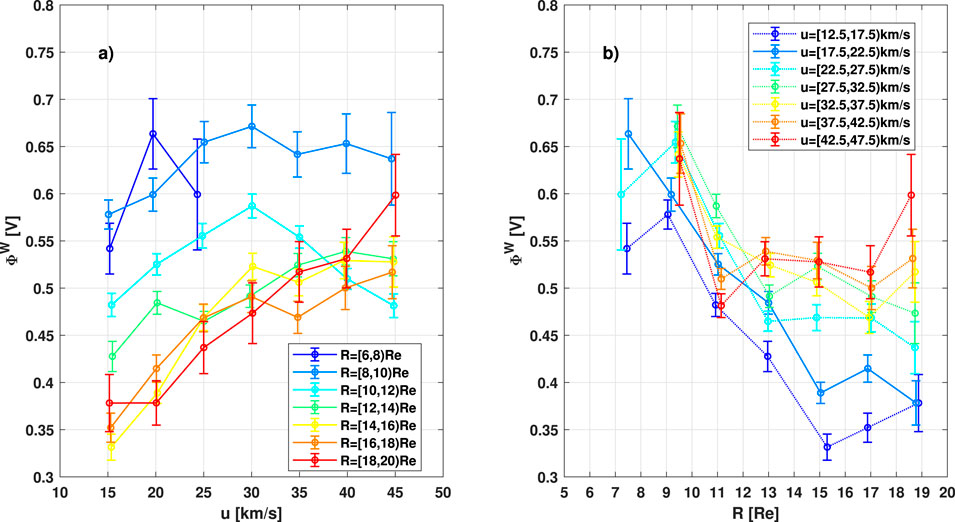

In Figure 3a, we combine the curves of all panels in Figure 3. These curves are color-coded by the ranges of

Figure 4. (a) Mean values of

Since the simulations by Engwall et al. (2006) were performed only for

For other values of

5 Discussion

As mentioned in Section 2, our method uses a comparison of the measured

In general, the ion temperature is not necessarily the same as the electron temperature in the collisionless plasma of the tail lobes. Although there is no direct measurement of temperatures for both ions and electrons of cold plasma from the Cluster mission, our observation of the anti-correlation between

In the solar wind, the temperature ratio also varies with the increasing distance from the Sun. Shi et al. (2023) used the measurements from the Parker Solar Probe (PSP) below 30 solar radii and from the WIND at 1 AU. They found that the electron-to-proton temperature ratio evolves as the solar wind propagates from the Sun to the Earth. The observation is compared to their simulations, suggesting that the changes in the temperature ratio depend on the portion of the dissipated Alfvén wave energy that heats the protons or electrons. Their work suggests that Alfvén waves are one possible explanation for the evolution of proton and electron temperatures in the solar wind.

To explain the anti-correlation between

In Figure 4b, the violation of the anti-correlation is observed in

In general, electrons have a gyroradius much smaller than the scale thickness of the DF. Electrons are well magnetized and efficiently heated/accelerated by betatron acceleration due to the compression of magnetic flux in the DF (Fu et al., 2012; Gabrielse et al., 2016; Runov et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2018). Ions are often demagnetized and are less affected by DFs. This explanation is consistent with the fact that Cluster spacecraft were in the vicinity of the PSBL at large

6 Conclusion

In this study, the electric-field measurements of the plasma wake, formed by the Cluster spacecraft as it interacts with cold plasma escaping from the ionosphere, are used to examine how the electron-to-ion temperature ratio evolves as cold plasma flows into the tail lobes for the first time. Our findings are as follows.

• At the same distance from the Earth, we observe a correlation between the wake potential and the plasma flow speed, which aligns with theoretical predictions.

• For a constant plasma flow speed, the electron-to-ion temperature ratio decreases with increasing distance from the Earth up to 16

• Beyond 16

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found at http://cosmos.esa.int/web/csa.

Author contributions

KL: Project administration, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Resources, Investigation, Data curation, Software. JC: Software, Visualization, Writing – review and editing, Validation. LC: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review and editing. EK: Funding acquisition, Writing – review and editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation. ND: Writing – review and editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work is funded by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation under grants 2023A1515010887. KL, EK, and ND acknowledge the LMU-China Academic Network for the support. EK is also funded by the DFG Heisenberg under grant number 516641019. ND is supported by DFG project number 520916080.

Acknowledgements

KL thanks Anders Eriksson and Mats André at the Swedish Institute of Space Physics for a helpful discussion.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alpert, Y. L., Gurevich, V. G., and Pitaevskii, P. L. (1965). Space physics with artificial satellite. Consultants Bureau.

André, M., Li, K., and Eriksson, A. I. (2015). Outflow of low-energy ions and the solar cycle. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 120, 1072–1085. doi:10.1002/2014JA020714

André, M., Eriksson, A. I., Khotyaintsev, Y. V., and Toledo-Redondo, S. (2021). The spacecraft wake: interference with electric field observations and a possibility to detect cold ions. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 126, e29493. doi:10.1029/2021JA029493

Axford, W. I. (1968). The polar wind and the terrestrial helium budget. J. Geophys. Res. 73, 6855–6859. doi:10.1029/JA073i021p06855

Balogh, A., Carr, C. M., Acuña, M. H., Dunlop, M. W., Beek, T. J., Brown, P., et al. (2001). The cluster magnetic field investigation: overview of in-flight performance and initial results. Ann. Geophys. 19, 1207–1217. doi:10.5194/angeo-19-1207-2001

Collinson, G. A., Glocer, A., Pfaff, R., Barjatya, A., Conway, R., Breneman, A., et al. (2024). Earth’s ambipolar electrostatic field and its role in ion escape to space. Nature 632, 1021–1025. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07480-3

Engwall, E., Eriksson, A. I., and Forest, J. (2006). Wake formation behind positively charged spacecraft in flowing tenuous plasmas. Phys. Plasmas 13, 062904. doi:10.1063/1.2199207

Engwall, E., Eriksson, A. I., Cully, C. M., André, M., Torbert, R., and Vaith, H. (2009). Earth’s ionospheric outflow dominated by hidden cold plasma. Nat. Geosci. 2, 24–27. doi:10.1038/ngeo387

Fu, H. S., Khotyaintsev, Y. V., Vaivads, A., André, M., and Huang, S. Y. (2012). Electric structure of dipolarization front at sub-proton scale. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L06105. doi:10.1029/2012GL051274

Gabrielse, C., Harris, C., Angelopoulos, V., Artemyev, A., and Runov, A. (2016). The role of localized inductive electric fields in electron injections around dipolarizing flux bundles. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 121, 9560–9585. doi:10.1002/2016JA023061

Gustafsson, G., Bostrom, R., Holback, B., Holmgren, G., Lundgren, A., Stasiewicz, K., et al. (1997). The electric field and wave experiment for the cluster mission. Space Sci. Rev. 79, 137–156. doi:10.1023/A:1004975108657

Haaland, S., Eriksson, A., Engwall, E., Lybekk, B., Nilsson, H., Pedersen, A., et al. (2012). Estimating the capture and loss of cold plasma from ionospheric outflow. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 117, A07311. doi:10.1029/2012JA017679

Keiling, A. (2009). Alfvén waves and their roles in the dynamics of the Earth’s Magnetotail: A Reviewm Space Sci. Rev. 142, 73–156. doi:10.1007/s11214-008-9463-8

Keiling, A., Parks, G. K., Wygant, J. R., Dombeck, J., Mozer, F. S., Russell, C. T., et al. (2005). Some properties of Alfvén waves: Observations in the tail lobes and the plasma sheet boundary layer. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 110, A10S11. doi:10.1029/2004JA010907

Li, K., André, M., Eriksson, A., Wei, Y., Cui, J., and Haaland, S. (2021). High-latitude cold ion outflow inferred from the Cluster wake observations in the magnetotail lobes and the polar cap region. Front. Phys. 9, 620. doi:10.3389/fphy.2021.743316

Nilsson, H., Engwall, E., Eriksson, A., Puhl-Quinn, P. A., and Arvelius, S. (2010). Centrifugal acceleration in the magnetotail lobes. Ann. Geophys. 28, 569–576. doi:10.5194/angeo-28-569-2010

Paschmann, G., Quinn, J. M., Torbert, R. B., Vaith, H., McIlwain, C. E., Haerendel, G., et al. (2001). The Electron Drift Instrument on Cluster: overview of first results. Ann. Geophys. 19, 1273–1288. doi:10.5194/angeo-19-1273-2001

Rème, H., Aoustin, C., Bosqued, J. M., Dandouras, I., Lavraud, B., Sauvaud, J. A., et al. (2001). First multispacecraft ion measurements in and near the earth’s magnetosphere with the identical cluster ion spectrometry (cis) experiment. Ann. Geophys. 19, 1303–1354. doi:10.5194/angeo-19-1303-2001

Runov, A., Angelopoulos, V., Gabrielse, C., Zhou, X.-Z., Turner, D., and Plaschke, F. (2013). Electron fluxes and pitch-angle distributions at dipolarization fronts: THEMIS multipoint observations. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 118, 744–755. doi:10.1002/jgra.50121

Sauvaud, J. A., Louarn, P., Fruit, G., Stenuit, H., Vallat, C., Dandouras, J., et al. (2004). Case studies of the dynamics of ionospheric ions in the Earth’s magnetotail. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 109, A01212. doi:10.1029/2003JA009996

Shi, C., Velli, M., Lionello, R., Sioulas, N., Huang, Z., Halekas, J. S., et al. (2023). Proton and Electron Temperatures in the Solar Wind and Their Correlations with the Solar Wind Speed. ApJ 944, 82. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/acb341

Takada, T., Nakamura, R., Baumjohann, W., Seki, K., Vörös, Z., Asano, Y., et al. (2006). Alfvén waves in the near-PSBL lobe: Cluster observations. Ann. Geophys. 24, 1001–1013. doi:10.5194/angeo-24-1001-2006

Keywords: cold plasma, temperature ratio, spacecraft potential, magnetotail lobes, plasma wake

Citation: Li K, Chen J, Chai L, Kronberg E and Doepke N (2025) Evolution of the electron-to-ion temperature ratio of cold plasma in the lobes. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 12:1683785. doi: 10.3389/fspas.2025.1683785

Received: 11 August 2025; Accepted: 05 November 2025;

Published: 26 November 2025.

Edited by:

Joseph E. Borovsky, Space Science Institute (SSI), United StatesReviewed by:

Megha Pandya, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, United StatesShipra Sinha, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, United States

Copyright © 2025 Li, Chen, Chai, Kronberg and Doepke. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kun Li, bGlrdW4zN0BtYWlsLnN5c3UuZWR1LmNu

Kun Li

Kun Li Junhan Chen1

Junhan Chen1 Lihui Chai

Lihui Chai Elena Kronberg

Elena Kronberg Nicolas Doepke

Nicolas Doepke