- 1Goddard Planetary Heliophysics Institute, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 2NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, United States

- 3Department of Physical and Chemical Sciences, University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy

- 4Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica - Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, INFN Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Rome, Italy

- 5INFN - Sezione di Roma “Tor Vergata”, Rome, Italy

- 6Lancaster University, Lancaster, United Kingdom

- 7Heliophysics, Planetary Science and Aeronomy Division, National Institute of Space Research (INPE), São José dos Campos, Brazil

- 8Space Environment Technologies, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 9National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico, Mexico

- 10Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, Daytona Beach, FL, United States

Editorial on the Research Topic

Impacts of the extreme Gannon geomagnetic storm of May 2024 throughout the magnetosphere-ionosphere-thermosphere system

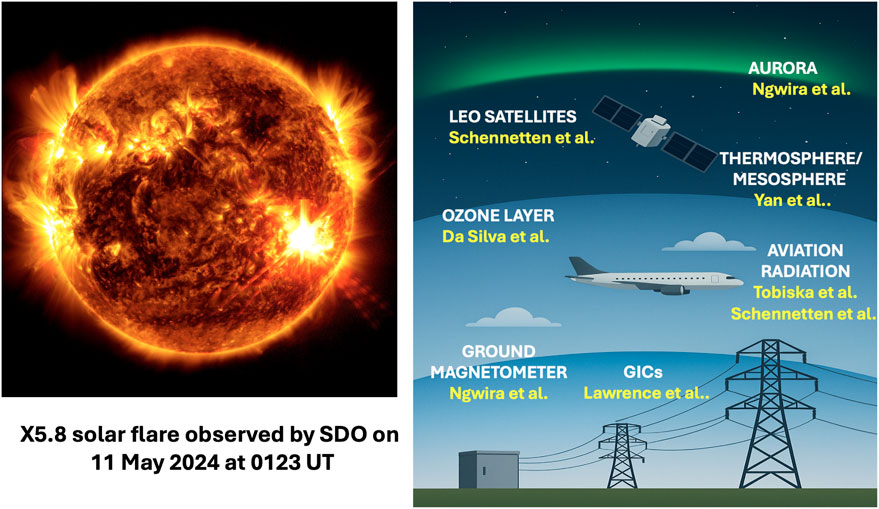

Hayakawa et al. (2025) provided a concise data report about the drivers of the extreme geomagnetic storm of May 2024, also known as the Gannon storm. The event was primarily driven by a rapid succession of large coronal mass ejections (CMEs) emanating from a highly active sunspot region, unleashing several X-class solar flares into the interplanetary space. Figure 1 (right part), available at https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/14703/, shows a Solar Dynamic Observatory image of the most intense solar flare (X5.8 class) of that period whose peak occurred at 0123 UT of 11 May 2024. The flare is indicated by the intense flash in the image at near the eastern limb slightly below the solar equator. The figure shows a blend of light with wavelengths of 171, 304, and 131 Å, which indicate extreme ultraviolet light. The solar flares and CMEs significantly increased solar energetic particle (SEP) fluxes and radiation levels near Earth, forming temporary radiation belts (Li et al., 2025) and elevating high-altitude radiation exposure (Hayakawa et al., 2025; Papaioannou et al., 2025).

Figure 1. Left: Solar Dynamics Observatory observation of an X5.8 solar flare (bright region near the eastern solar limb a few degrees below the Sun’s equator) associated with Active Region 13664 on 11 May 2024 at 0123 UT. That active region also ejected many CMEs that struck the magnetosphere in early May, inducing the most extreme geomagnetic storms of solar cycle 25. Right: Schematic illustration of key space-weather impacts throughout the geospace environment addressed in this editorial. Effects include thermospheric and mesospheric disturbances, auroral activity, radiation levels measured by satellites at low-Earth orbit, ozone layer variability, aviation radiation exposure, ground magnetic field perturbations, and geomagnetically induced currents in power systems. Text labels highlight the studies addressing each of these domains reported in this editorial.

The multiple CMEs interacted and merged en-route to Earth, resulting in a complex ejecta structure that compressed the magnetosphere (magnetopause standoff position to

Many space weather and geomagnetic effects have been reported for this storm. This includes the generation of very large Kelvin-Helmholtz waves at the CME ejecta-sheath boundaries upstream of the Earth (Nykyri, 2024), low-latitude auroras (Hayakawa et al., 2025), the largest geomagnetically induced current (GIC) peak ever observed in Latin America (Caraballo et al., 2025), positioning outrages of Global Positioning System (GPS) due to ionospheric disturbances (Yang and Morton, 2025), caused the largest upward satellite migration ever performed in low-Earth orbit (LEO) (Parker and Linares, 2024), and accelerated satellite re-entry from LEO with respect to a reference altitude

This Research Topic received 6 articles dealing with different aspects of elevated radiation levels and geomagnetic activity in May 2024. The findings reported in these articles are briefly summarized below.

We begin this editorial with the Research Topic of aviation radiation effects. Tobiska et al. evaluate how aviation radiation mitigation strategies performed during the extreme Gannon storm due to high solar activity. The authors compare real-time radiation monitoring and mitigation tools at flight altitudes, demonstrating that the established ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) frameworks successfully limited exposure even as SEP fluxes and atmospheric dose rates surged. Their findings highlight the importance of robust, validated aviation-radiation procedures during extreme space weather events. Such mitigation actions correspond to lowering altitudes and route deviations to equator-ward magnetic latitudes due to magnetic shielding effects (Gao et al., 2022), reinforcing that terrestrial infrastructure and high-altitude aviation are vulnerable–and yet that mitigation protocols can work effectively under extreme conditions.

Addressing the same Research Topic of aviation radiation, Schennetten et al. used a physics-based radiation transport and dose-calculation model to simulate radiation dose rates at aviation altitudes and LEO, combining three distinct contributions: 1) the additional dose from SEPs; 2) changes in geomagnetic shielding (cut-off rigidities) evaluated during the storm; and 3) the effect of a Forbush decrease reducing the galactic cosmic ray background. Using this approach, Schennetten et al. found that although the SEPs during the Gannon storm did contribute to the radiation field at aviation altitudes, but the dose rates remained relatively low. However, dose rates in LEO reached much higher values. Moreover, when all effects are combined for a hypothetical flight from Frankfurt to Los Angeles, the additional total effective dose was estimated at 14%–24% above baseline. The study thereby highlights that while SEPs can elevate doses during an extreme storm, this is not necessarily the case for every such event, because the actual impact depends strongly on the SEP energy spectrum, geomagnetic conditions, and atmospheric shielding.

Using data from the SuperMAG ground network, the Spherical Elementary Current System method–which maps ionospheric currents–and mid-latitude auroral imagery, Ngwira et al. examine ground geomagnetic activity during the Gannon storm. Those authors show that powerful CME–CME interactions and prolonged southward interplanetary magnetic field (IMF)

Lawrence et al. present both direct ground magnetic and electric field observations across the United States and combine these with magnetotelluric-derived resistivity models of the subsurface and a high-voltage transmission network model to estimate GICs. The key findings include the auroral electrojet intrusion to surprisingly low latitudes (below

Da Silva et al. combine multi-instrument satellite and ground-based observations to investigate how the Gannon storm affected the South Atlantic Magnetic Anomaly (SAMA), a region with the weakest geomagnetic field (Gledhill, 1976). Using particle detectors aboard LEO satellites, Da Silva et al. monitored the behavior of low-energy electrons in the inner radiation belt, while ionospheric radars and digisondes provided measurements of ionization changes over South America. In addition, satellite-borne sensors tracked variations in ozone concentration in the upper atmosphere. The study found that the flux of low-energy electrons in the inner radiation belt vanished at the same time that energy input into the magnetosphere ceased–indicating a strong coupling between these processes. This period coincided with enhanced ionization in the ionospheric E-region over SAMA and pronounced variability in electron fluxes.

Finally, Yuan et al. used coordinated lidar and optical observations from a midlatitude station to reveal how the neutral atmosphere responded to the Gannon storm. Their analysis show that during the storm, the upper portion of the sodium layer nearly disappeared at the same time that thermospheric temperatures increased and strong equatorward winds developed. These simultaneous changes indicate that energy and momentum from high-latitude geomagnetic activity penetrated deeply into midlatitudes, directly altering both the dynamics and composition of the mesosphere and lower thermosphere. The results demonstrate that even regions far from the auroral zones can experience significant coupling between magnetospheric forcing, neutral winds, and atmospheric chemistry during extreme space weather events. The right panel of Figure 1 presents a schematic diagram highlighting the key regions and technological systems affected by space weather, along with the first author associated with each contributing study.

In summary, this Research Topic enhances our understanding of solar and geomagnetic effects during the May 2024 storm on aviation radiation, GICs and geoelectric fields in the US and the United States, effects on the atmosphere at mid-latitude mesosphere and lower thermosphere, and perturbations in the neutral and ionized atmosphere over the SAMA region. Although our focus was on the Gannon storm, the October 2024 storm can also offer further insights of extreme space weather effects. Even though the October event was the third extreme event since the Halloween storms of 2003 (Oliveira et al., 2025b), very few studies have focused on that event thus far. Examples are intense red aurora observations by citizen scientists (Kataoka et al., 2025), impacts of merging electric field on field-aligned currents and polar electrojets (Xia et al., 2025), and a premature re-entry of a Starlink satellite (Oliveira et al., 2025b). Studies comparing many aspects of the extreme 2024 events–including their drivers and subsequent space weather effects–could be the focus of a future Rearch Topic in Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences.

Jennifer L. Gannon was a distinguished space-weather scientist whose research profoundly advanced our understanding of GICs and ground-magnetic disturbances (Lugaz et al., 2024). Dr. Gannon’s work established essential connections between magnetospheric physics and the protection of technological infrastructure on Earth. The extreme geomagnetic storm of May 2024, now known as the Gannon storm and the Research Topic of this editorial, fittingly honors her enduring contributions and impact on the geospace community. We dedicate this editorial and Research Topic to the memory of Dr. Gannon.

Author contributions

DO: Funding acquisition, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft. MP: Project administration, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft. M-TW: Writing – original draft, Project administration, Writing – review and editing. LA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Project administration. WT: Writing – original draft, Project administration, Writing – review and editing. XB-C: Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration. KN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Project administration.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. DMO acknoledges funding provided by UMBC’s START (Strategic Awards for Research Transitions) program (grant code SR25OLIV), NASA’s Living With a Star (LWS) program (NNH22ZDA001N-LWS), NASA’s Internal Scientist Funding Model (ISFM), and NSF’s EMpowering BRoader Academic Capacity and Education (EMBRACE) program (AGS-2432908). MTW acknowledges funding from UKRI through the ErnestRutherford Fellowship (ST/X003663/1). LRA acknowledges funding from CNPq grant PQ-C- 304482/2024-2. KN acknowledges funding from NASA LWS award # 80NSSC23K0899 and NASA ISFM, and Magnetosphere Multiscale (MMS) mission programs.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Caraballo, R., González-Esparza, J. A., Pacheco, C. R., Corona-Romero, P., Arzate-Flores, J. A., and Castellanos-Velazco, C. I. (2025). The impact of Geomagnetically induced currents (GIC) on the Mexican power grid: numerical modeling and observations from the 10 may 2024, geomagnetic storm. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2024GL112749. doi:10.1029/2024GL112749

Gao, J., Korte, M., Panovska, S., Rong, Z., and Wei, Y. (2022). Geomagnetic field shielding over the last one hundred thousand years. J. Space Weather Space Clim. 12, 31. doi:10.1051/swsc/2022027

Gledhill, J. A. (1976). Aeronomic effects of the South Atlantic anomaly. Rev. Geophys. 14, 173–187. doi:10.1029/RG014i002p00173

Gonzalez-Esparza, J. A., Sanchez-Garcia, E., Sergeeva, M., Corona-Romero, P., Gonzalez-Mendez, L. X., Valdes-Galicia, J. F., et al. (2024). The mother’s day geomagnetic storm on 10 May 2024: aurora observations and low latitude space weather effects in Mexico. Space Weather. 22, e2024SW004111. doi:10.1029/2024SW004111

Hayakawa, H., Ebihara, Y., Mishev, A., Koldobskiy, S., Kusano, K., Bechet, S., et al. (2025). The solar and geomagnetic storms in 2024 May: a flash data report. Astrophysical J. 979, 49. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ad9335

Kataoka, R., Nakano, S., Uchino, S., and Reddy, S. A. (2025). Extended red aurora associated with super substorm igniting the October 10, 2024 magnetic storm as revealed by citizen science. Earth, Planets Space 77, 64. doi:10.1186/s40623-025-02178-w

Li, X., Xiang, Z., Mei, Y., O’Brien, D., Brennan, D., Zhao, H., et al. (2025). A new electron and proton radiation belt identified by CIRBE/REPTile-2 measurements after the magnetic super storm of 10 May 2024. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 130, e2024JA033504. doi:10.1029/2024JA033504

Lugaz, N., Knipp, D., Morley, S. K., Liu, H., Hapgood, M., Carter, B., et al. (2024). In Memoriam of editor Jennifer L. Gannon. Space Weather. 22, e2024SW004016. doi:10.1029/2024SW004016

Nilam, B., Tulasi Ram, S., Oliveira, D. M., Remya, B., Shiokawa, K., Rai, D., et al. (2025). Strong westward current pulse at auroral latitudes extending to dawn-side low-latitudes due to enhanced density within Kelvin-Helmholtz wave vortex in solar wind. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2025GL117032. doi:10.1029/2025GL117032

Nykyri, K. (2024). Giant Kelvin-Helmholtz (KH) waves at the boundary layer of the coronal mass ejections (CMEs) responsible for the largest geomagnetic storm in 20 years. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL110477. doi:10.1029/2024GL110477

Oliveira, D. M., Zesta, E., and Garcia-Sage, K. (2025a). Tracking reentries of starlink satellites during the rising phase of solar cycle 25. Front. Astronomy Space Sci. 12, 1572313. doi:10.3389/fspas.2025.1572313

Oliveira, D. M., Zesta, E., and Nandy, D. (2025b). The 10 October 2024 geomagnetic storm may have caused the premature reentry of a Starlink satellite. Front. Astronomy Space Sci. 11, 1522139. doi:10.3389/fspas.2024.1522139

Papaioannou, A., Mishev, A., Usoskin, I., Heber, B., Vainio, R., Larsen, N., et al. (2025). The high-energy protons of the ground level enhancement (GLE74) event on 11 May 2024. Sol. Phys. 300, 73. doi:10.1007/s11207-025-02486-0

Parker, W. E., and Linares, R. (2024). Satellite drag analysis during the May 2024 gannon geomagnetic storm. J. Spacecr. Rockets 61, 1412–1416. doi:10.2514/1.A36164

Piersanti, M., Oliveira, D. M., D’Angelo, G., Diego, P., Napoletano, G., and Zesta, E. (2025). On the geoelectric field response to the SSC of the May 2024 super storm over Europe. Space Weather. 23, e2024SW004191. doi:10.1029/2024SW004191

Tulasi Ram, S., Veenadhari, B., Dimri, A. P., Bulusu, J., Bagiya, M., Gurubaran, S., et al. (2024). Super-intense geomagnetic storm on 10–11 May 2024: possible mechanisms and impacts. Space Weather. 22, e2024SW004126. doi:10.1029/2024SW004126

Xia, X., Hu, X., Wang, H., and Zhang, K. (2025). Correlation study of auroral currents with external parameters during 10-12 October 2024 superstorm. Remote Sens. 17, 394. doi:10.3390/rs17030394

Keywords: Gannon storm, extreme events, aviation radiation, ozone layer, geomagnetically induced current (GIC), ground magnetometer

Citation: Oliveira DM, Piersanti M, Walach M-T, Alves LR, Tobiska WK, Blanco-Cano X and Nykyri K (2025) Editorial: Impacts of the extreme Gannon geomagnetic storm of May 2024 throughout the magnetosphere-ionosphere-thermosphere system. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 12:1742847. doi: 10.3389/fspas.2025.1742847

Received: 09 November 2025; Accepted: 21 November 2025;

Published: 09 December 2025.

Edited and reviewed by:

Yongliang Zhang, Johns Hopkins University, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Oliveira, Piersanti, Walach, Alves, Tobiska, Blanco-Cano and Nykyri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Denny M. Oliveira, ZGVubnkubS5kZW9saXZlaXJhQG5hc2EuZ292

Denny M. Oliveira

Denny M. Oliveira Mirko Piersanti

Mirko Piersanti Maria-Theresia Walach

Maria-Theresia Walach Livia R. Alves

Livia R. Alves W. Kent Tobiska

W. Kent Tobiska Xochitl Blanco-Cano

Xochitl Blanco-Cano Katariina Nykyri

Katariina Nykyri