Abstract

The CCR2/CCL2 molecular axis is a critical mediator of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) pathogenesis. It has been demonstrated to drive chronic inflammation, extracellular matrix degradation, and vascular remodeling through the recruitment and activation of monocytes/macrophages and other immune cell types. Pre-clinical studies demonstrate that CCR2 inhibition reduces AAA formation, expansion, and progression in animal models. Emerging imaging techniques have validated CCR2 as a biomarker for AAA instability in humans. Although clinical trials targeting CCR2 are currently limited in number, ongoing translational studies highlight that CCR2 blockade is a promising therapeutic strategy to mitigate AAA expansion and the risk of rupture. This review underscores the potential of CCR2-targeting interventions to fill a critical unmet need to develop effective medical therapies for longitudinal clinical AAA management.

Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) are progressive localized dilations of the abdominal aorta, typically defined as having a diameter ≥3.0 cm (1, 2). AAAs carry a substantial risk of rupture and rupture events are associated with a high mortality rate of 80%–90%, resulting in approximately 200,000 annual deaths globally (3–5). The majority of AAAs are incidentally detected during imaging performed for unrelated reasons; however, many can be missed and remain undiagnosed until they rupture (6, 7). AAAs predominantly impact older males, with the risk factors including smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, white race, and family history (1, 7). Diagnosis is primarily dependent on imaging, with ultrasound as the gold standard for the initial screening, often followed by computed tomography (CT) or CT angiography, whereas a physical examination has limited sensitivity (8). Management of an AAA is primarily determined by the aneurysm’s size and growth rate. Small aneurysms are monitored with serial imaging and “expectant management,” whereas large aneurysms (≥5.5 cm in males and ≥5.0 cm in females) or those expanding rapidly require elective open or endovascular surgical repair (1–4, 6). Beyond these interventions, there are currently no approved pharmacological therapies to halt aneurysm expansion or prevent rupture events. Furthermore, the lack of reliable diagnostic markers for predicting AAA rupture risk underscores the critical need to better understand the molecular mechanisms driving AAA progression and identify novel theranostic targets (9).

AAA formation is primarily driven by chronic vascular inflammation, leading to elastin degradation, vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) loss, fibroblast activation, and phenotype switching (3, 10, 11). Key inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages, and T cells, progressively accumulate within the aortic wall and secrete various pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, contributing to extracellular matrix (ECM) imbalance through the release of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), specifically MMP-2 and MMP-9 (3, 12). These molecular mediators orchestrate the remodeling process that underlies AAA expansion and increased risk of rupture over time (13).

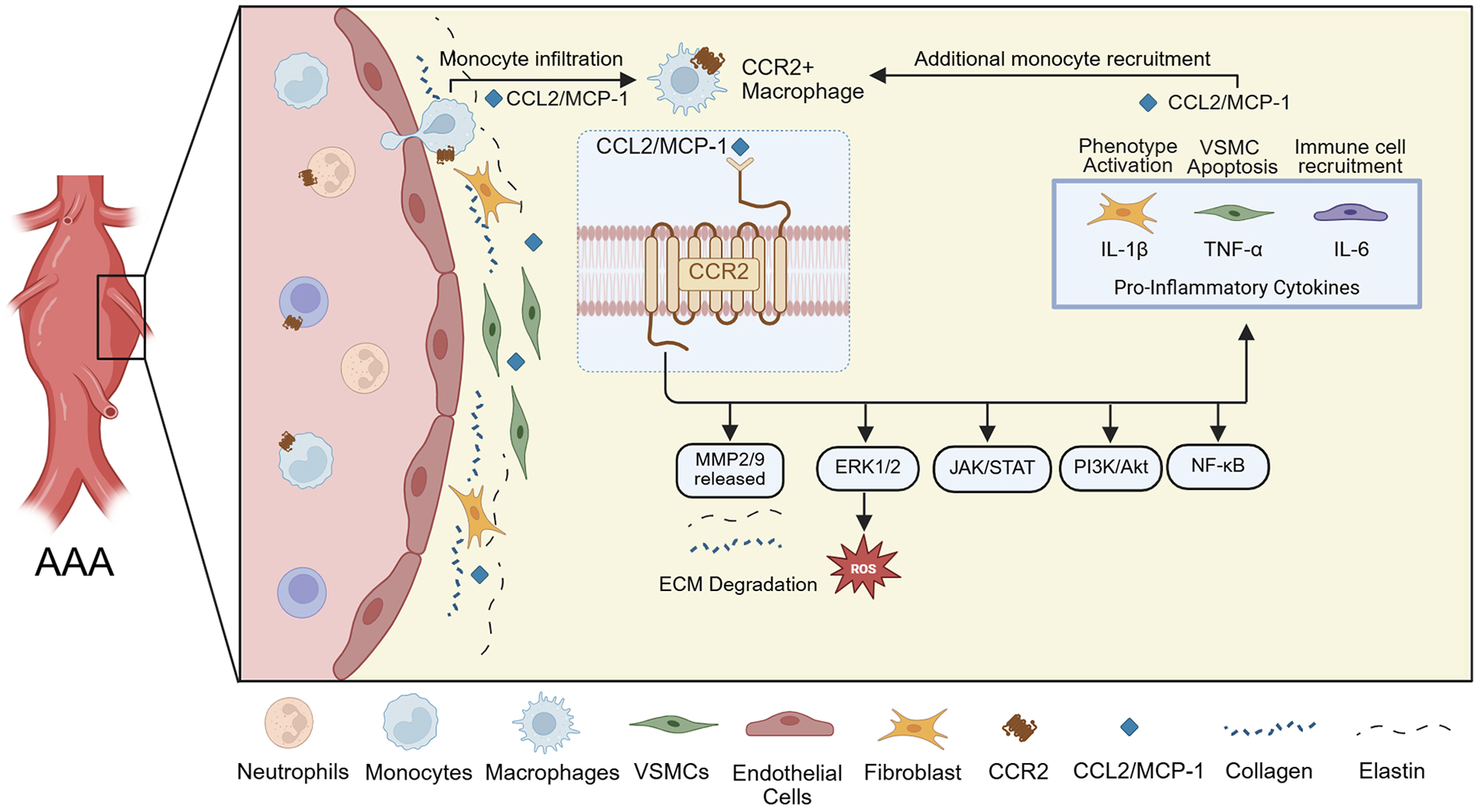

Chemokines, in particular, are small signaling proteins that play a vital role in vascular inflammation by mediating leukocyte recruitment to sites of tissue injury (14). These molecules interact with chemokine receptors, typically G protein-coupled receptors, to form chemotactic gradients that guide immune cell migration (14). Chemokines are classified into structural families, most notably CC and CXC, based on the arrangement of disulfide bonds on their conserved cysteine residues. In the context of AAA development, the C-C motif chemokine ligand and receptor type 2 (CCL2 and CCR2, respectively) represent a key molecular axis in the early inflammatory cascade (14–16). CCL2 (also known as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 or MCP-1) is secreted by activated endothelial cells, fibroblasts, VSMCs, and macrophages within the aortic tissue in response to vascular injury (17). Bone-marrow-derived, circulating immune cells expressing CCR2, especially monocytes, are drawn to sites of inflammation by the CCL2 gradient, leading to their infiltration into the aortic wall, where they contribute to the chronic inflammatory environment that drives aneurysm formation and progression (Figure 1) (17, 18). This chemokine-mediated recruitment of inflammatory cells can set the stage for the cellular and molecular remodeling events central to AAA pathology.

Figure 1

Schematic representation of CCR2+ monocyte recruitment and downstream effects in the AAA wall. The inflammatory environment is associated with elevated MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression in wall tissue, leading to ECM degradation, and the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 maintain further CCR2+ monocyte recruitment.

The CCR2 receptor binding to its principal ligand, CCL2, triggers a cascade of intracellular signaling pathways, including ERK1/2, PI3K/Akt, JAK/STAT, and NF-κB (Figure 1) (19, 20). These pathways converge on key pro-inflammatory and tissue remodeling responses. Upon activation, CCR2 also promotes monocyte migration and activation, leading to the release of MMP-2 and MMP-9, reactive oxygen species, and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Figure 1) (21–23). These MMPs present in aneurysmal tissue degrade the ECM, with collagen type I/IV, laminin, and E-cadherin serving as substrates (24). Moreover, CCR2 signaling is thought to affect fibroblast and VSMC behavior, contributing to phenotypic switching, apoptosis, and further weakening of the aortic wall (Figure 1) (22). These mechanisms are critical in AAA pathogenesis, as persistent CCR2 activity sustains a chronic inflammatory state that drives ECM breakdown, wall thinning, and expansion of the aneurysmal segment. Subsequent inflammation and cell activation lead to further secretion of MCP-1, promoting additional monocyte recruitment, occasionally becoming a circled loop of inflammation that cannot be well-balanced by anti-inflammatory mediators (22, 24, 25). This excessive inflammatory activation is believed to promote AAA progression and contributes to its eventual rupture, despite the tissue’s attempt to repair the wall.

CCL2/CCR2-targeting strategies in AAAs

Several animal studies have underscored the pivotal role of the CCL2/CCR2 axis in the initiation and progression of aortic aneurysms (25–30). Transplantation of Ccr2−/− bone marrow into Apoe−/− mice was sufficient to mitigate aneurysm formation following aneurysm induction with an angiotensin II (ANG II) infusion model. Despite the upregulation of CCL2 in the aortic tissue, macrophage infiltration and the levels of inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-6 remained persistently low. These results implicate bone marrow-derived CCR2+ macrophages as key drivers of inflammation and cytokine release, thereby contributing to aneurysm development and progression (25).

Building on these findings, subsequent studies investigated the impact of whole-body Ccr2 knockout on AAA formation. MacTaggart et al. examined the roles of CCR2, CXCR3, and CCR5 in a murine CaCl2-induced infrarenal AAA model (26). This study demonstrated that only the Ccr2−/− cohort had significant inhibition of AAA formation, resulting in smaller aneurysm diameters compared to the CXCR3 and CCR5 knockout groups. These findings highlight that CCR2 is unlikely to be a non-specific bystander and rather drives molecular mechanisms that progress AAA disease pathology (26). Additionally, a histological analysis of Ccr2−/− aortic tissue revealed a significant reduction in macrophage infiltration and decreased levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9, again underscoring the critical role of CCR2 in driving AAA pathology (26). Similarly, Daugherty et al. demonstrated that a whole-body deficiency of Ccr2 also attenuated ascending and suprarenal aortic formation in the Apoe−/− and ANG II model (27).

Recent studies have focused on the critical role of CCR2 in AAA rupture. Whole-body genetic knockdown of Ccr2 in a mouse model prone to AAA rupture, achieved using intraluminal porcine pancreatic elastase (PPE), daily β-aminopropionitrile (BAPN), and ANG II, demonstrated a significantly reduced incidence of infrarenal AAA rupture, confirming the pivotal role of CCR2 in aneurysm expansion leading to rupture (28). Given this critical role, recent investigations have also used 64Cu-DOTA-ECL1i, a radiolabeled CCR2-targeting peptide. Using positron emission tomography (PET), 64Cu-DOTA-ECL1i can be used to assess CCR2 content in rupture-prone AAAs following induction with intraluminal PPE and BAPN in male and female Sprague Dawley rats (29, 30). These studies showed the specificity of CCR2 tracing in both rat AAAs and human explanted AAA tissue, highlighting its potential utility as a theranostic tool in humans in vivo.

Further investigations evaluated the efficacy of RS504393, a specific CCR2 pharmacological inhibitor (30). When introduced on day 3, after the establishment of AAA through intraluminal elastase exposure, RS504393 treatment significantly reduced both AAA size and rupture events in male and female rats. Inhibition of CCR2 also led to notable decreases in inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, elastin fragmentation, and macrophage infiltration. A dose-dependent response was observed, with continued treatment further reducing AAA progression, rupture, and immune cell infiltration (30). An additional study explored the impact of a ketogenic diet on AAA in rats. This nutritional intervention significantly mitigated AAA rupture and significantly downregulated CCR2 content, MMP activation, and preserved elastin with an overall improved balance in the extracellular matrix (28). These studies provided significant insights into the molecular mechanisms driving AAA pathology and highlighted the potential of targeting the CCL2/CCR2 axis as an effective therapeutic strategy for AAA stabilization.

Targeting CCR2/CCL2 in other pathologies

In addition to the demonstrated utility of CCR2 targeting in AAA models, CCR2/CCL2 axis modulation has also been investigated as an inhibitor of fibrosis, serving as a potential target for increasing the efficacy of chemotherapy delivery (31–39). This has led to the development and use of several therapeutic agents in pre-clinical animal models and in larger-scale clinical trials more recently (40–46).

Since fibrosis in the aneurysmal aortic wall in animal models and human tissue has likewise been identified as a pathological factor for potential intervention ( 31, 32), targeted CCR2 inhibition to mitigate macrophage-mediated end-organ fibrosis has also been evaluated in murine models. In an acute myocardial infarction model, CCR2 inhibition using inhibitor 4 (Teijin compound 1), which was applied directly to a caged nitric oxide donor patch, shifted macrophages to an anti-inflammatory M2 polarization and improved post-infarction cardiac function (33). This inhibitor was additionally explored through liposomal coupling for VCAM1-directed endothelial targeting for drug delivery as a means to mitigate monocyte transmigration, with demonstrated efficacy in reducing macrophage recruitment to Apoe−/−murine aortic tissue (34). Cenicriviroc (CVC) is an oral dual antagonist of CCR2/CCR5 originally designed for the treatment of Human Immunodeficiency Virus and has been found to attenuate hepatic fibrosis in a murine injury model (35, 36). Through RNA sequencing and bulk-RNA analysis, it was observed that CVC led to the downregulation of common profibrotic signaling pathways (JAK-STAT, TNF-NFκB, and MAPK-ERK), with collagen I immunofluorescence demonstrating a similar level of expression to control livers.

CCR2 inhibition has been further explored as an adjunct to chemotherapy targeting PD-1. Three oral inhibitors—CCX872, MK0812, and RS504393—have been explored in murine glioblastoma and breast cancer metastasis models ( 37–39). These studies demonstrated a reduction in tumor myeloid-derived suppressor burden, with evidence that these cells were retained within the bone marrow. Therapeutically, CCR2 inhibition was found to provide a survival benefit when co-administered with anti-PD-1 chemotherapy, whereas anti-PD-1 therapy alone was insufficient.These studies did not report any notable toxic effects of drug administration.

Targeted CCR2/CCL2 axis inhibition in human trials

Clinical translation of CCR2 inhibitors has been limited to date. However, in 2011, a study investigated the use of MLN1202 (plozalizumab), a monoclonal antibody that interacts with CCR2 to inhibit CCL2 binding. Including 112 patients randomized to MLN1202 or placebo, the study achieved its primary endpoint of reducing serum C-reactive protein in patients at high atherosclerotic risk ( 40). CCR2 inhibition with cenicriviroc for the mitigation of hepatic fibrosis was explored in the AURORA phase III study, a randomized trial involving 1,778 patients (41). While this study demonstrated a good safety profile with only two patients experiencing treatment-related adverse events warranting medication discontinuation, cenicriviroc did not demonstrate efficacy in preventing non-alcoholic steatosis (NASH) (41). PF-04136309 is an orally administered CCR2 inhibitor that was recently investigated in a phase 1b study in 21 patients as an adjuvant to the standard chemotherapeutic agents used in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (42). This study noted potential pulmonary toxicity related to CCR2 inhibitor administration, though this was confounded by the concurrent use of adjunct chemotherapeutic agents. A summary of completed human clinical trials utilizing CCR2 antagonist therapy is presented inTable 1(40–46).

Table 1

| Compound | Characteristics | Disease studied | Dosing | Trial phase/type | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCX140-B | Small molecule, selective CCR2 antagonist | Diabetic nephropathy | 5 mg or 10 mg PO daily | Phase 2, RCT, double-blind | (43) |

| BMS-813160 | Small molecule, dual CCR2/CCR5 antagonist | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | Up to 300 mg PO BID | Phase 1/2 | (44) |

| MLN1202 (plozalizumab) | Humanized monoclonal antibody, anti-CCR2 | Melanoma, cardiovascular disease | 2–10 mg/kg | Phase 1/2 | (40, 45) |

| Cenicriviroc (CVC) | Small molecule, dual CCR2/CCR5 antagonist | NASH, liver fibrosis | 150 mg PO daily | Phase 3/RCT | (41) |

| JNJ-41443532 | Small molecule, selective CCR2 antagonist | Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 100 mg PO daily | Phase 2/RCT | (46) |

| PF-04136309 | Small molecule, selective CCR2 antagonist | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | Up to 750 mg PO BID | Phase 1b | (42) |

CCR2 antagonists used in completed human trials, with the drug and dosing characteristics and the pathology of interest investigated in each trial.

Discussion

Herein, we provided an updated review of recent pre-clinical assessments and early human clinical translation of therapeutics targeting the CCR2/CCL2 axis—particularly in the setting of AAA management. Recent evidence in AAA biology suggests that CCR2 may be a cellular marker for disease progression. Investigators have found that PET/CT uptake for CCR2 content is not only higher in AAA patients vs. controls, meaning it is disease-specific, but it also correlates with areas that are prone to rupture based on a finite element analysis of mechanical wall stress. These findings, along with the specificity of CCR2 in AAA human tissues and MCP-1 expression, suggest a potential theranostic role for CCR2 in AAA. Animal studies of CCR2 knockout or inhibition have demonstrated utility in mitigating AAA rupture. Ongoing assessments of CCR2 inhibitor compounds have suggested reasonable in vivo biotolerance without substantial adverse effects in both animal and early human clinical trials investigating other pathologies. Similar to oncological studies, vascular therapies are moving towards more specific, cellular-driven treatments to improve patients' outcomes while minimizing off-target effects.

Statements

Author contributions

RW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SE-B: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RC: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. BK: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. MZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was supported by NIH/NHLBI R01HL153262 and R01HL150891, NIH/NIBIB T32EB021955, and NIH/NHLBI T32HL170959.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author MZ declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Chaikof EL Dalman RL Eskandari MK Jackson BM Lee WA Mansour MA et al The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. (2018) 67(1):2–77.e2. 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.10.044

2.

Isselbacher EM Preventza O Hamilton Black J 3rd Augoustides JG Beck AW Bolen MA et al 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. (2022) 146(24):e334–482. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001106

3.

Cho MJ Lee MR Park JG . Aortic aneurysms: current pathogenesis and therapeutic targets. Exp Mol Med. (2023) 55:2519–30. 10.1038/s12276-023-01130-w

4.

Liu B Granville DJ Golledge J Kassiri Z . Pathogenic mechanisms and the potential of drug therapies for aortic aneurysm. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2020) 318(3):H652–70. 10.1152/ajpheart.00621.2019

5.

Cosford PA Leng GC Thomas J . Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2007). (2):CD002945. 10.1002/14651858.CD002945.pub2

6.

Asmundo L Zanardo M Vitali P Conca M Soro A Mazzaccaro D et al Incidental diagnosis and reporting rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms on lumbar spine magnetic resonance imaging. Quant Imaging Med Surg. (2025) 15(4):3543–50. 10.21037/qims-24-1291

7.

Pinard A Jones GT Milewicz DM . Genetics of thoracic and abdominal aortic diseases. Circ Res. (2019) 124(4):588–606. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312436

8.

US Preventive Services Task Force, OwensDKDavidsonKWKristAHBarryMJCabanaMCaugheyABet alScreening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. (2019) 322(22):2211–8. 10.1001/jama.2019.18928

9.

Gao J Cao H Hu G Wu Y Xu Y Cui H et al The mechanism and therapy of aortic aneurysms. Sig Transduct Target Ther. (2023) 8:55. 10.1038/s41392-023-01325-7

10.

Kuivaniemi H Ryer EJ Elmore JR Tromp G . Understanding the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. (2015) 13:975–87. 10.1586/14779072.2015.1074861

11.

Choke E Thompson M Dawson J Wilson R Sayed S Loftus I et al Abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture is associated with increased medial neovascularization and overexpression of proangiogenic cytokines. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2006) 26:2077–82. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000234944.22509.f9

12.

Li Y Ren P Dawson A Vasquen H Ageedi W Zhang C et al Single-cell transcriptome analysis reveals dynamic cell populations and differential gene expression patterns in control and aneurysmal human aortic tissue. Circulation. (2020) 142:1374–88. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046528

13.

Li H Bai S Ao Q Wang X Tian X Li X et al Modulation of immune-inflammatory responses in abdominal aortic aneurysm: emerging molecular targets. J Immunol Res. (2018) 2018:7213760. 10.1155/2018/7213760

14.

Charo IF Ransohoff RM . The many roles of chemokines and chemokine receptors in inflammation. N Engl J Med. (2006) 354(6):610–21. 10.1056/NEJMra052723

15.

Cyster JG . Chemokines, sphingosine-1-phosphate, and cell migration in secondary lymphoid organs. Annu Rev Immunol. (2005) 23:127–59. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115628

16.

Luster AD . Chemokines—chemotactic cytokines that mediate inflammation. N Engl J Med. (1998) 338:436–45. 10.1056/NEJM199802123380706

17.

Singh S Anshita D Ravichandiran V . MCP-1: function, regulation, and involvement in disease. Int Immunopharmacol. (2021) 101(Pt B):107598. 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107598

18.

Braga TT Correa-Costa M Silva RC Cruz MC Hiyane MI da Silva JS et al CCR2 contributes to the recruitment of monocytes and leads to kidney inflammation and fibrosis development. Inflammopharmacology. (2018) 26(2):403–11. 10.1007/s10787-017-0317-4

19.

Zhang H Yang K Chen F Liu Q Ni J Cao W et al Role of the CCL2-CCR2 axis in cardiovascular disease: pathogenesis and clinical implications. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:975367. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.975367

20.

Zhu S Liu M Bennett S Wang Z Pfleger K Xu J . The molecular structure and role of Ccl2 (Mcp-1) and c-c chemokine receptor Ccr2 in skeletal biology and diseases. J Cell Physiol. (2021) 236(10):7211–22. 10.1002/jcp.30375

21.

Gschwandtner M Derler R Midwood KS . More than just attractive: how CCL2 influences myeloid cell behavior beyond chemotaxis. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:2759. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02759

22.

Mantovani A Sica A Sozzani S Allavena P Vecchi A Locati M . The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. (2004) 25:677–86. 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015

23.

Apel AK Cheng RKY Tautermann CS Brauchle M Huang CY Pautsch A et al Crystal structure of CC chemokine receptor 2A in complex with an orthosteric antagonist provides insights for the design of selective antagonists. Structure. (2019) 27(3):427–438.e5. 10.1016/j.str.2018.10.027

24.

Maguire EM Pearce SWA Xiao R Oo AY Xiao Q . Matrix metalloproteinase in abdominal aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). (2019) 12(3):118. 10.3390/ph12030118

25.

Ishibashi M Egashira K Zhao Q Hiasa K Ohtani K Ihara Y et al Bone marrow-derived monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 receptor CCR2 is critical in angiotensin II-induced acceleration of atherosclerosis and aneurysm formation in hypercholesterolemic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2004) 24(11):e174–8. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000143384.69170.2d

26.

MacTaggart JN Xiong W Knispel R Baxter BT . Deletion of CCR2 but not CCR5 or CXCR3 inhibits aortic aneurysm formation. Surgery. (2007) 142(2):284–8. 10.1016/j.surg.2007.04.017

27.

Daugherty A Rateri DL Charo IF Owens AP Howatt DA Cassis LA . Angiotensin II infusion promotes ascending aortic aneurysms: attenuation by CCR2 deficiency in apoE−/− mice. Clin Sci. (2010) 118(11):681–9. 10.1042/CS20090372

28.

Sastriques-Dunlop S Elizondo-Benedetto S Arif B Meade R Zaghloul MS Luehmann H et al Ketosis prevents abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture through C–C chemokine receptor type 2 downregulation and enhanced extracellular matrix balance. Sci Rep. (2024) 14(1):1438. 10.1038/s41598-024-51996-7

29.

English SJ Sastriques SE Detering L Sultan D Luehmann H Arif B et al CCR2 positron emission tomography for the assessment of abdominal aortic aneurysm inflammation and rupture prediction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. (2020) 13(3):E009889. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.119.009889

30.

Elizondo-Benedetto S Sastriques-Dunlop S Detering L Arif B Heo GS Sultan D et al Chemokine receptor 2 is a theranostic biomarker for abdominal aortic aneurysms. JACC Basic Transl Sci. (2025) 10(7):101250. 10.1016/j.jacbts.2025.02.010

31.

Mackay CDA Jadli AS Fedak PWM Patel VB . Adventitial fibroblasts in aortic aneurysm: unraveling pathogenic contributions to vascular disease. Diagnostics (Basel). (2022) 12(4):871. 10.3390/diagnostics12040871

32.

Aubdool AA Moyes AJ Perez-Ternero C Baliga RS Sanghera JS Syed MT et al Endothelium- and fibroblast-derived C-type natriuretic peptide prevents the development and progression of aortic aneurysm. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2025) 45(7):1044–63. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.124.322350

33.

Zheng Y Gao W Qi B Zhang R Ning M Hu X et al CCR2 inhibitor strengthens the adiponectin effects against myocardial injury after infarction. FASEB J. (2023) 37(8):e23039. 10.1096/fj.202300281RR

34.

Calin M Stan D Schlesinger M Simion V Deleanu M Constantinescu CA et al VCAM-1 directed target-sensitive liposomes carrying CCR2 antagonists bind to activated endothelium and reduce adhesion and transmigration of monocytes. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. (2015) 89:18–29.

35.

Brown E Hydes T Hamid A Cuthbertson DJ . Emerging and established therapeutic approaches for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Ther. (2021) 43(9):1476–504. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.07.013

36.

Guo Y Zhao C Dai W Wang B Lai E Xiao Y et al C-C motif chemokine receptor 2 inhibition reduces liver fibrosis by restoring the immune cell landscape. Int J Biol Sci. (2023) 19(8):2572–87. 10.7150/ijbs.83530

37.

Flores-Toro JA Luo D Gopinath A Sarkisian MR Campbell JJ Charo IF et al CCR2 inhibition reduces tumor myeloid cells and unmasks a checkpoint inhibitor effect to slow progression of resistant murine gliomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2020) 117(2):1129–38. 10.1073/pnas.1910856117

38.

Sugiyama S Yumimoto K Fujinuma S Nakayama KI . Identification of effective CCR2 inhibitors for cancer therapy using humanized mice. J Biochem. (2024) 175(2):195–204. 10.1093/jb/mvad086

39.

Tu MM Abdel-Hafiz HA Jones RT Jean A Hoff KJ Duex JE et al Inhibition of the CCL2 receptor, CCR2, enhances tumor response to immune checkpoint therapy. Commun Biol. (2020) 3(1):720. 10.1038/s42003-020-01441-y10.1093/jb/mvad086

40.

Gilbert J Lekstrom-Himes J Donaldson D Lee Y Hu M Xu J et al Effect of CC chemokine receptor 2 CCR2 blockade on serum C-reactive protein in individuals at atherosclerotic risk and with a single nucleotide polymorphism of the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 promoter region. Am J Cardiol. (2011) 107(6):906–11. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.11.005

41.

Anstee QM Neuschwander-Tetri BA Wong W-S Abdelmalek V Rodriguez-Araujo MF Landgren G et al Cenicriviroc lacked efficacy to treat liver fibrosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: AURORA phase III randomized study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2024) 22(1):124–134.e1. 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.003

42.

Noel M O'Reilly EM Wolpin BM Ryan DP Bullock AJ Britten CD et al Phase 1b study of a small molecule antagonist of human chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2 (PF-04136309) in combination with nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine in first-line treatment of metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Invest New Drugs. (2020) 38(3):800–11. 10.1007/s10637-019-00830-3

43.

de Zeeuw D Bekker P Henkel E Hasslacher C Gouni-Berthold I Mehling H et al CCX140-B diabetic Nephropathy Study Group. The effect of CCR2 inhibitor CCX140-B on residual albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy: a randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2015) 3(9):687–96. 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00261-2

44.

Grierson PM Wolf C Suresh R Wang-Gillam A Tan BR Ratner L et al Neoadjuvant BMS-813160, nivolumab, gemcitabine, and nab-paclitaxel for patients with pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. (2025) 31(17):3644–51. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-24-1821

45.

Sullivan RJ Tsai KK Pavlick AC Buchbinder EI Agarwala SS Ribas A et al Phase 1b study of tovorafenib, plozalizumab or vedolizumab plus standard-of-care immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced melanoma. J Cancer. (2025) 16(13):3797–809. 10.7150/jca.117878

46.

Di Prospero NA Artis E Andrade-Gordon P Johnson DL Vaccaro N Xi L et al CCR2 antagonism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Obes Metab. (2014) 16(11):1055–64. 10.1111/dom.12309

Summary

Keywords

aortic aneurysm, aortic rupture, CCR2, inflammation, inhibitor, molecular targeting

Citation

Wahidi R, Elizondo-Benedetto S, Catlett R, Koklu B and Zayed MA (2026) Modulation of CCR2/CCL2 molecular axis in the expansion and rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 13:1772497. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2026.1772497

Received

21 December 2025

Accepted

20 January 2026

Published

17 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Hanjoong Jo, Emory University, United States

Reviewed by

Hasan Sari, Mut State Hospital, Türkiye

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Wahidi, Elizondo-Benedetto, Catlett, Koklu and Zayed.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Mohamed A. Zayed zayedm@wustl.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.