Abstract

In the early stages of mammalian embryonic development, the bipotential gonads can differentiate into the testes or ovaries. These organs are essential for gamete production, transmitting genetic information to offspring via sperm or oocytes. Testis differentiation is triggered by the Y chromosome sex-determining region (SRY) genetic program, with male reproductive health largely established during the early stages of testis development. However, SRY is only transiently activated in precursor Sertoli cells, initiating their differentiation. At later stages, differentiated Sertoli cells are crucial for male sex determining in other cell lineages, including germ cells, Leydig cells involved in steroid hormone synthesis, and the establishment of vascular patterns. Clearly, Sertoli cells play an essential role in testis development and function, and are indispensable for male reproduction. In this review, we examine the composition and functional dynamics of the testis, highlighting how single-cell transcriptomics has redefined our understanding of testicular cellular architecture and functional diversity. We focus on the pivotal regulatory roles of Sertoli cells in orchestrating the development and functional coordination of germ cells, Leydig cells, peritubular myoid cells, and testicular macrophages. Furthermore, we discuss the pathological consequences of Sertoli cell dysfunction and its mechanistic contributions to male reproductive disorders, providing molecular insights into spermatogenic failure and androgen dysregulation.

1 Introduction

The testis is the primary organ of male sexual development and reproduction, secreting androgens to promote body masculinization and producing sperm for reproduction (Jiménez et al., 2021; Luo et al., 2022). Sertoli cells (SCs), as essential somatic cells in the testis, play a central role in testis formation during fetal development, as well as in the initiation and maintenance of spermatogenesis during puberty and adulthood. SCs also establish an immunoprivileged environment for germ cells (GCs), preventing autoimmune responses triggered by neoantigens during spermatogenesis (Luaces et al., 2023). Furthermore, SCs are key regulators of cell lineage differentiation within the testis, which promote male gonadal development (Rotgers et al., 2018), and specifies Leydig cells (LCs) and peritubular myoid cells (PMCs) fate (Li et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2021). Postnatally, SCs also play a significant role in androgen production by LCs, development of PMCs, and regulation of the vasculature. Disruption of SCs function can lead to male reproductive disorders (see Figure 1). In this review, we systematically describe the central role of SCs in the testis, explore the mechanisms underlying their pathological dysfunction, and highlight how SCs serve as key factors in testicular development and functional maintenance. We hope this review offers insights into testis function and male reproductive health, encouraging further detailed investigations.

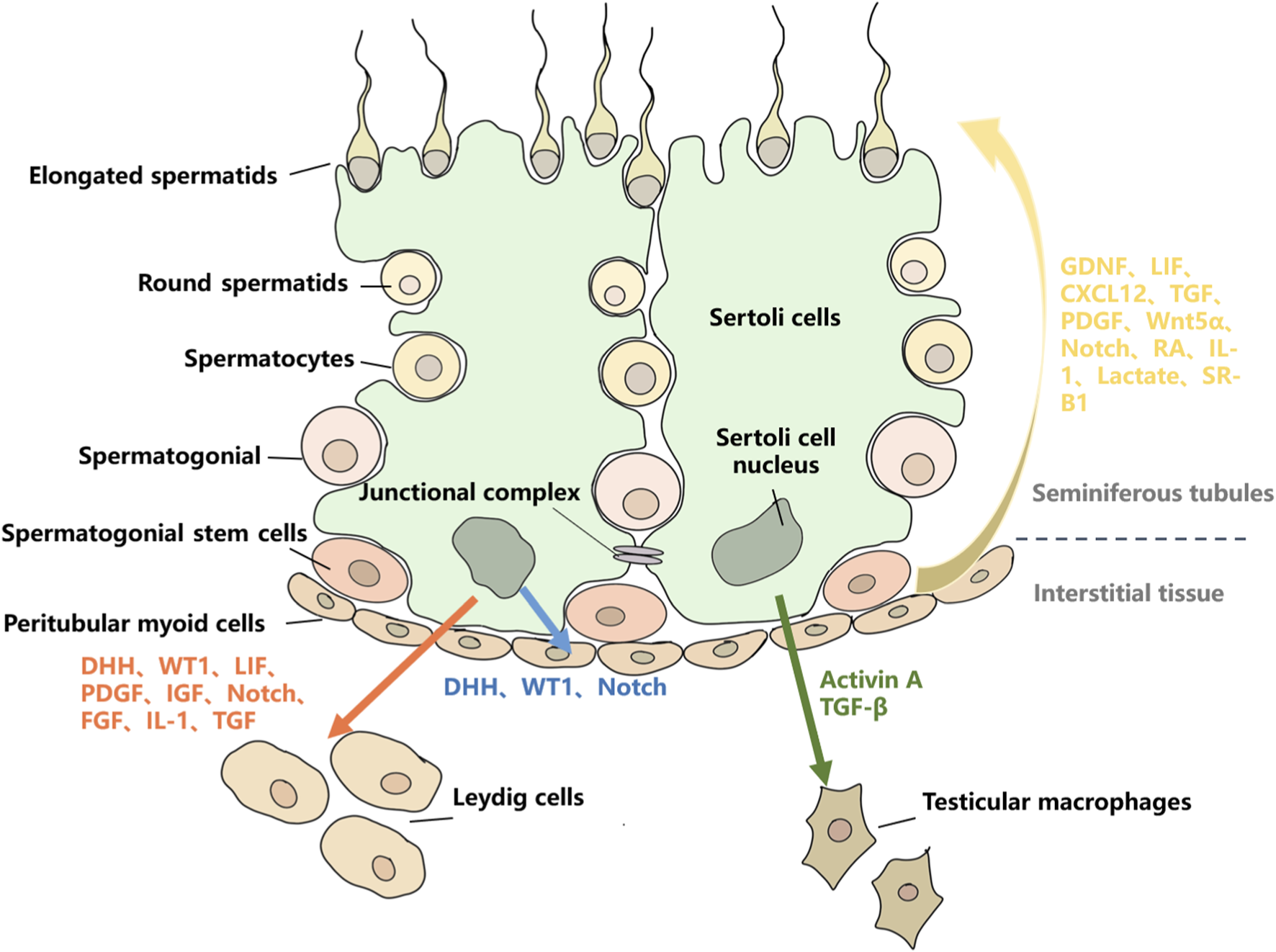

FIGURE 1

The regulatory roles of SCs on other testicular cell types. Red arrows represent the regulatory effects of SCs on LCs, mainly through the secretion of DHH, WT1, LIF, PDGF, IGF, Notch, FGF, IL-1, and TGF. Blue arrows represent the regulatory effects of SCs on PMCs, mainly through the secretion of DHH, WT1, and Notch. Green arrows represent the regulatory effects of SCs on TMs, mainly through the secretion of Activin-A and TGF-β. Yellow arrows represent the regulatory effects of SCs on GCs, mainly through the secretion of GDNF, LIF, CXCL12, TGF, PDGF, Wnt5α, Notch, RA, IL-1, Lactate, and SR-B1.

2 Composition and function of testis

The testis comprises various types of cells, including GCs, SCs, LCs, PMCs, and testicular macrophages (TMs) (Mäkelä et al., 2019). Its tissue structure is primarily divided into two regions: the seminiferous tubules and the interstitial tissue (Oatley and Brinster, 2012). In the seminiferous tubules, SCs and PMCs form the basal lamina. GCs are located on the basal membrane and are classified into three types: spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs, undifferentiated spermatogonia), spermatogonia (SSCs that undergo active mitosis), and preleptotene spermatocytes (differentiated spermatogonia) (Wanjari and Gopalakrishnan, 2024). SCs support normal spermatogenesis by providing a cellular matrix and secreting specific growth factors (Chojnacka et al., 2016; Luca et al., 2018a). During spermatogenesis, SCs exhibit significant dynamic changes and are capable of supporting the simultaneous development of various types of GCs (Sawaied et al., 2025). The types and numbers of GCs supported by SCs vary at different stages of the spermatogenic cycle, typically including one to two types of spermatogonia, one to two types of spermatocytes, and one to two types of haploid spermatids. The number of GCs supported by SCs is regulated by various factors, primarily including species differences, the developmental status of SCs before puberty, SCs density within the seminiferous tubules, and the endocrine environment. In the mouse, spermatogenesis is divided into 12 stages, forming a complete spermatogenic cycle (O’Donnell et al., 2022a). In rodents such as mice, the spermatogenic cycle occurs sequentially along the length of the tubules, while in humans and primates, multiple spermatogenic cycles are interwoven, forming a more complex spermatogenic structure (O’Donnell et al., 2022b). The interstitial space contains LCs, mesenchymal cells, and immune cells (Oatley and Brinster, 2012). LCs produce androgens and cytokines, which may act directly or indirectly to regulate SSCs self-renewal (Zaker et al., 2022). GCs, Somatic cells, and various cytokines synthesized and secreted within the testis together form the testicular microenvironment (see Figure 2) (Zhou et al., 2019). Studies have shown that within the microenvironment, different types of cells communicate through cytokines to promote spermatogenesis and testosterone synthesis (Arora et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023). These interactions are essential for the normal functioning of the testis, including cell proliferation, differentiation, metabolism, and protein transport (Arora et al., 2022). SCs are the most critical somatic cells in testis, closely associated with GCs, supporting and guiding their development into mature spermatozoa during spermatogenesis (Griswold, 2018). Similarly, SCs play a vital role in maintaining the stability of SSCs pool (Ibtisham et al., 2020).

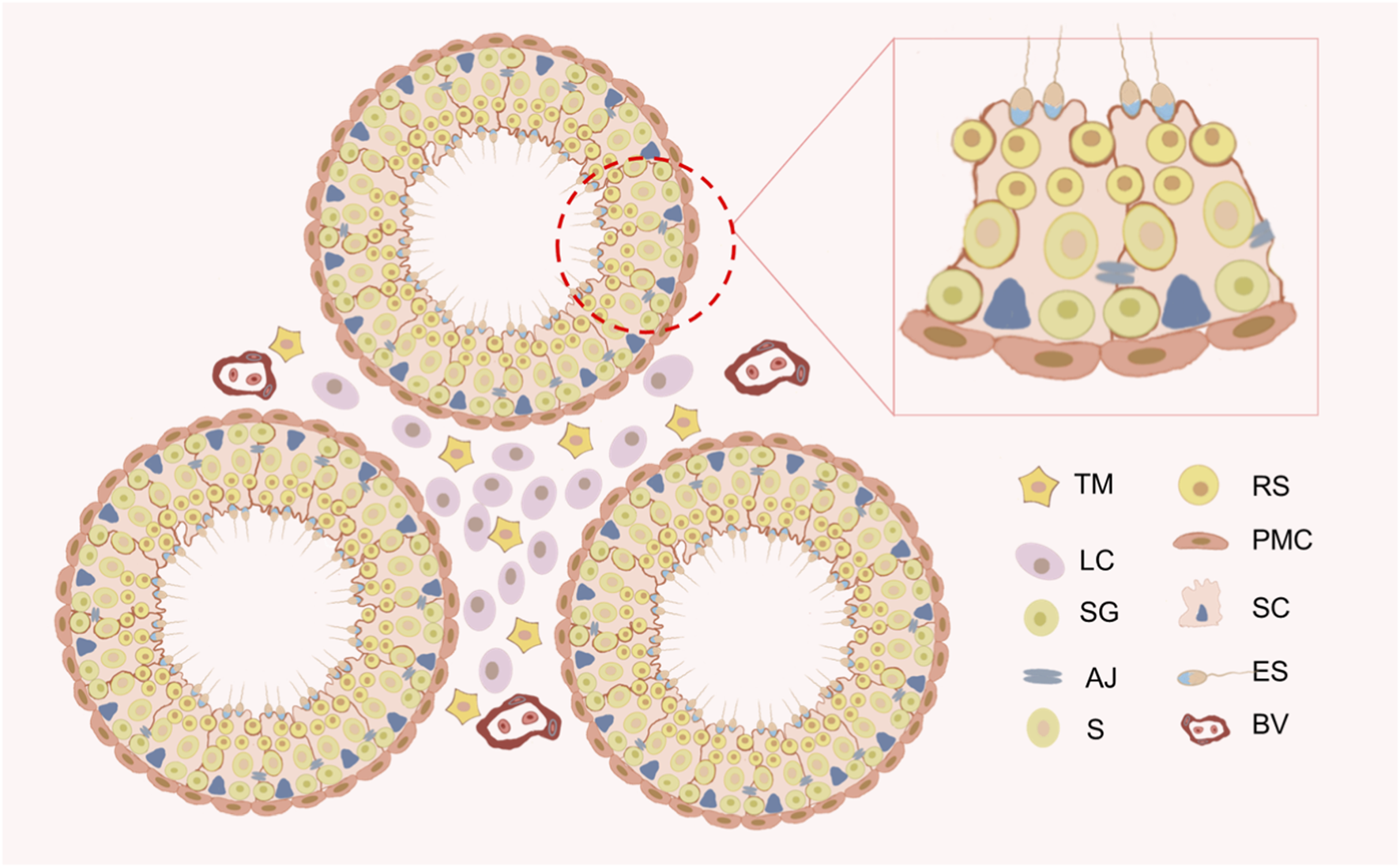

FIGURE 2

Schematic diagram of the testicular microenvironment of the mouse. The testis comprises two main components: the seminiferous tubules and the interstitial spaces. Peritubular myoid cells (PMCs) and Sertoli cells (SCs) together form the basal lamina of the seminiferous tubules. Germ cells develop in the seminiferous epithelium formed by SCs. Germ cells include spermatogonium (SG), spermatocytes (S), round spermatids (RS), and elongated spermatids (ES). The interstitial spaces primarily consist of Leydig cells (LCs) and testicular macrophages (TMs). Blood vessels (BV) are located within the interstitial spaces.

2.1 SCs

SCs, also known as “nanny cells”, are among the most intricate cells in the testis (França et al., 2016) and play crucial roles in protecting spermatogenic cells, providing nutrients and physical support for spermatogenesis and testis development (Griswold, 2018). SCs are classified based on stages into two types: immature Sertoli cells (ISCs, from fetal to pre-pubertal) and adult Sertoli cells (ASCs, from pubertal and post-pubertal) (You et al., 2021). ISCs participate in fetal sexual differentiation and pre-pubertal testicular development (Sekido and Lovell-Badge, 2013). Studies have shown that at E10-11 of mouse embryonic development, coelomic epithelial cells differentiate into gonadal somatic cells, which are bipotential can develop into either an ovary or a testis (Poulsen et al., 2019). The transition from the ovarian to the testis pathway is driven by the SRY gene expressed in pre-SCs during the narrow window of embryonic development (E10.5) (Hiramatsu et al., 2009; Bunce et al., 2023). By E12.5 of embryonic development, SCs form seminiferous cords around gonocytes (Yokonishi and Capel, 2021). Fetal Sertoli cells (FSCs) proliferation is essential for the lengthening and expansion of testicular seminiferous cords (Archambeault and Yao, 2010). After birth, SCs continue to proliferate until puberty, at which point they become non-proliferative and terminally differentiated (Meroni et al., 2019). ASCs maintain spermatogenesis during puberty and adulthood (Griswold, 2018) and provide immune protection for spermatogenic cells (Kaur et al., 2014). Normal SCs function is essential for GCs survival and fertility, and SCs dysfunction can lead to testicular pathology and male sterility (Murphy and Richburg, 2014; Ni et al., 2020). SCs exhibit strong secretory function, releasing various of substances, such as growth factors (including GDNF (Garcia et al., 2017), TGFs (Fang et al., 2023), NFG (Niu et al., 2020), SCF (Chui et al., 2011), ILs (Fadlalla, 2019), IGFs (Cannarella et al., 2019), FGFs (Tian et al., 2019), Activin (O’Donnell et al., 2022a)), transport protein (such as transferrin (Yefimova et al., 2008), androgen-binding proteins (Yefimova et al., 2008), sulfated glycoprotein (Hartmann et al., 2016), and ceruloplasmin-like protein proteins (Skinner and Griswold, 1983)) and regulatory proteins (AMH (Rodriguez et al., 2022), endothelin (Chan et al., 2008), and inhibin (Lucas-Herald and Mitchell, 2022)), these substances regulate the self-renewal and differentiation of spermatogenic cells, as well as the growth and development of the male reproductive system.

2.2 LCs

LCs are located in the interstitial spaces of the seminiferous tubules and are mainly responsible for androgen synthesis and secretion, essential for spermatogenesis (Fang et al., 2021; Medici et al., 2024). In mammals, at least two types of LCs exist: fetal Leydig cells (FLCs) and adult Leydig cells (ALCs). FLCs synthesize androgen in the testis before birth, while ALCs perform this function after birth (Teerds and Huhtaniemi, 2015; Shima, 2019). FLCs produce androstenedione, which requires converted to testosterone in the presence of FSCs (Shima et al., 2013). During embryonic development, FLCs and FSCs jointly produce high androgen levels, promoting male reproductive organ differentiation and brain masculinization (Lee et al., 2024). Postnatally, FLCs decrease in number, resulting in reduced androgen production, which eventually reaches a minimum. With the development of ALCs from testicular stem cells, androgen levels gradually increase (Chauvigné et al., 2012; Zirkin and Papadopoulos, 2018). Testosterone regulates mammalian spermatogenesis, and its deficiency in adults leads to reduced fertility, fat accumulation, impaired cognitive function, weakened immune response, and fatigue (Chen H et al., 2017). Rodent LCs development proceeds through four main stages: stem Leydig cells (SLCs), progenitor Leydig cells (PLCs), immature Leydig cells (ILCs), and ALCs, as illustrated in Figure 3A (Chen M et al., 2017). However, another type of LCs exists in the primate and human testis, short-lived during the neonatal stage, thought their origin remains unclear (Nistal et al., 1986; Prince, 1992; Prince, 2001). The hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis (HPTA) is transiently activated during the first 6 months after birth, promoting neonatal LCs development and increasing androgen levels. After this period, the HPTA returns to inactivity, and neonatal LCs either involute or dedifferentiate (as shown in Figure 3B) (Prince, 1990). During this brief period, the function of nascent LCs is largely unstudied and remains unknown. It is hypothesized that testosterone synthesis by neonatal LCs is linked to the central nervous system and contributes to brain development (Martin, 2016).

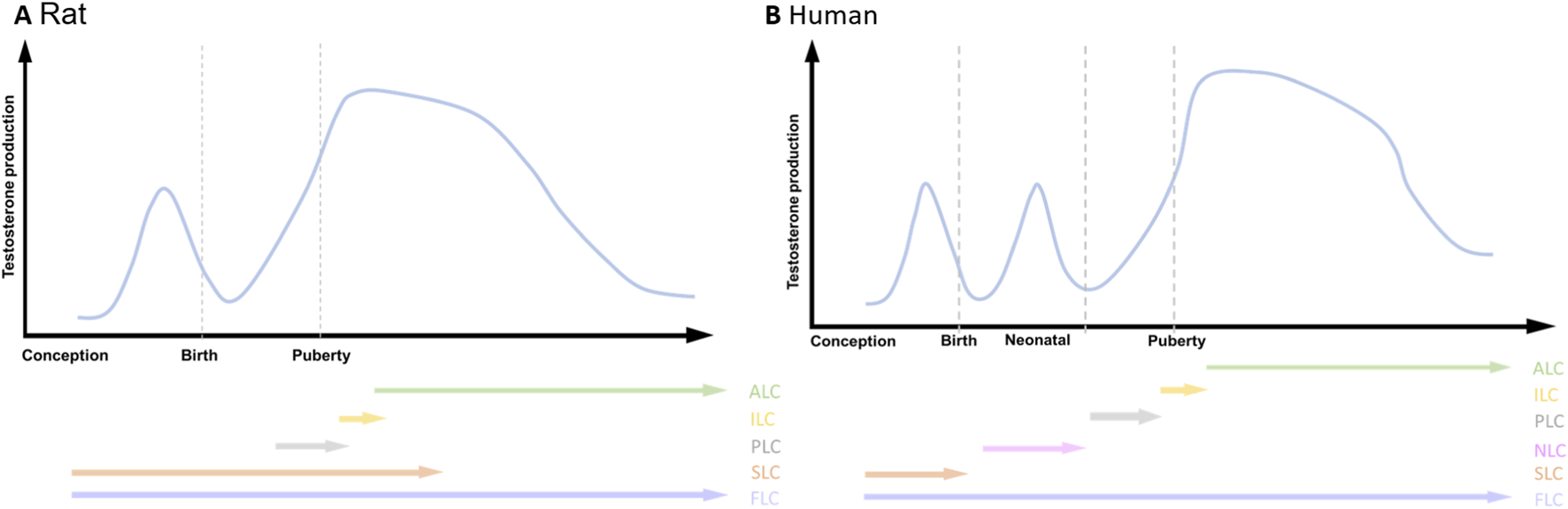

FIGURE 3

Testosterone production and the emergence of LCs during the life span. (A) Rat; (B) Human. adult Leydig cells (ALC), immature Leydig cells (ILC), progenitor Leydig cells (PLC), neonatal Leydig cells (NLC), stem Leydig cells (SLC), fetal Leydig cells (FLC). Two androgenic peaks are present in Rat, while three androgenic peaks are present in human.

2.3 TMs

TMs represent the largest reservoir of immune cells in the mammalian testis, accounting for over 20% of interstitial cells (Hume et al., 1984; Masone, 2023). TMs preserve testicular immune privilege by modulating the innate immune response (Bhushan et al., 2015; Bhushan and Meinhardt, 2017), thus attenuating pro-inflammatory responses triggered by external stimuli (Meinhardt et al., 2018). TMs are categorized into two types: interstitial macrophages and peritubular macrophages, with the former originating from embryo yolk sac cells (DeFalco et al., 2014). Fetal TMs play a crucial role in testicular morphological changes during early gonadal development and regulate vascular remodeling (Li Q et al., 2021). After birth, bone marrow progenitor cells differentiated into peritubular macrophages, which colonize empty niches as specialized tissue-resident macrophages (Mossadegh-Keller et al., 2017). Cytokines secreted by TMs promote LCs proliferation and differentiation (Gaytan et al., 1994), and stimulate steroid hormone synthesis (Hales, 2002; Hutson, 2006). These factors also contribute to the maintenance and differentiation of SSCs (DeFalco et al., 2015; Mossadegh-Keller et al., 2017), which are essential for testicular development and spermatogenesis.

2.4 PMCs

PMCs are a major component of the seminiferous tubule wall, characterized by smooth muscle-like features and playing a key role in sperm transport (Wang et al., 2018a). Evidence suggests that PMCs are closely related to spermatogenesis. During embryonic development, PMCs and SCs together form the basal lamina of the seminiferous epithelium, creating a unique microenvironment for SSCs self-renew, which maintain the number of spermatogonia and spermatocytes in the testis (Richardson et al., 1995; Uchida et al., 2020; Min et al., 2022). PMCs secrete leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 4 (LGR4), colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1), and glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), all of which regulate spermatogenesis and testicular function (Maekawa et al., 1996; Fernandez et al., 2008; Qian et al., 2013; Chen and Liu, 2016). However, when spermatogenesis is disrupted, the structure and function of PMCs undergo changes (Mayerhofer, 2013). Additionally, other cells in the TME secrete paracrine factors that can act on PMCs, promoting cell contraction, relaxation, and seminiferous tubule peristalsis (Fleck et al., 2021; Kawabe et al., 2022). Loss of PMCs contractile function results in sterility (Wang et al., 2018b).

2.5 GCs

In contrast to somatic cells in the testis, GCs play a crucial role in reproduction by accurately transmitting genetic information from one generation to the next (Yamashita, 2020). GCs comprise SSCs, spermatogonia, early spermatocytes, spermatids, and elongated spermatozoa (Hancock et al., 2021; Ren et al., 2022). In mammals, including mice and humans, male GCs development occurs in three main stages (see Figure 4): specification of primordial germ cells (PGCs), male sex differentiation, and spermatogenesis (Saitou and Miyauchi, 2016). PGCs are induced following the differentiation of trophectoderm and primitive endoderm (Saitou and Yamaji, 2012; Sasaki et al., 2016). PGCs, the earliest GCs in mice (appearing at E6.25), are detected around E7.25 (Richardson and Lehmann, 2010; Saitou and Yamaji, 2010). PGCs begin migrating at E7.5 and colonize the genital ridge at E10.5 (Seki et al., 2007; Nicholls and Page, 2021). Upon reaching the genital ridge, PGCs undergo mitotic arrest, remaining in the G0/G1 phase and becoming quiescent (Western et al., 2008). The first spermatogonia typically appear shortly after birth, and then the spermatogonia migrate from the center of the seminiferous tubules to the periphery, where they continue to proliferate (De Rooij and Russell, 2000; Nagano et al., 2000). In many male species (such as rats, mice, cats, sheep, donkeys, cattle), spermatogenesis occurs continuously, forming meiotic spermatocytes, spermatids, and ultimately elongated sperm. However, in humans and other primates, there is a long interval between the appearance of spermatogonia and the completion of spermatogenesis, which typically begins at puberty. Additionally, in seasonally breeding mammals, the first wave of spermatogenesis must occur at the start of each breeding season because a complete set of germ cells must be formed from spermatogonia (Jones et al., 2021). It has been reported that spermatogenesis begins on postnatal day 5 in mice, and a portion of the PGCs are recruited as SSCs, which migrate to the basement membrane of the seminiferous tubules and gradually move toward the lumen as their differentiation progresses (Oatley and Brinster, 2012; Yoshida, 2020). SSCs Self-renewal and differentiation maintain the stem cell pool, forming the foundation for sperm production (Walker, 2010). In rodents, Asingle spermatogonium are considered SSCs. Through mitosis, Asingle spermatogonium form two Apaired spermatogonia, if no intercellular bridges are present, they undergo self-renewal, producing two new Asingle spermatogonium; if intercellular bridges form, they differentiate into Aaligned-4, Aaligned-8, and Aaligned-16 (Dym et al., 2009). Aaligned-16 differentiate into A1 spermatogonia, which give rise to A2, A3, A4, intermediate, and B spermatogonia through successive mitotic divisions, eventually forming primary spermatocytes (Wakayama et al., 2015). Primary spermatocytes undergo two meiotic divisions to form secondary spermatocytes and round spermatids, which then undergo spermatid metamorphosis to become elongated spermatozoa (Zhang L. et al., 2022). In mice, Asingle, Apair, and Aaligned are considered undifferentiated spermatogonia, with Asingle accounting for 10% of this cell population (Nakagawa et al., 2007; Fayomi and Orwig, 2018). However, in primates, the classification of spermatogonia differs from that in mice. The spermatogonia of primates are classified into three types: Adark, Apale, and B. Adark spermatogonia are considered reserve-type, while Apale spermatogonia are proliferative-type, and B spermatogonia correspond to the differentiated cell population in mice (Lord and Oatley, 2017; Potter and DeFalco, 2017). Research indicates that Adark spermatogonia are a form of quiescent SSCs that typically only proliferate during puberty or when a large number of spermatogonia are lost due to certain factors, in order to restore the self-renewal capacity of SSCs. Apale spermatogonia constitute the majority of SSCs and undergo self-renewal and proliferation in a regulated manner according to the spermatogenic epithelial cycle (Kubota and Brinster, 2018). However, there is some debate surrounding this concept.

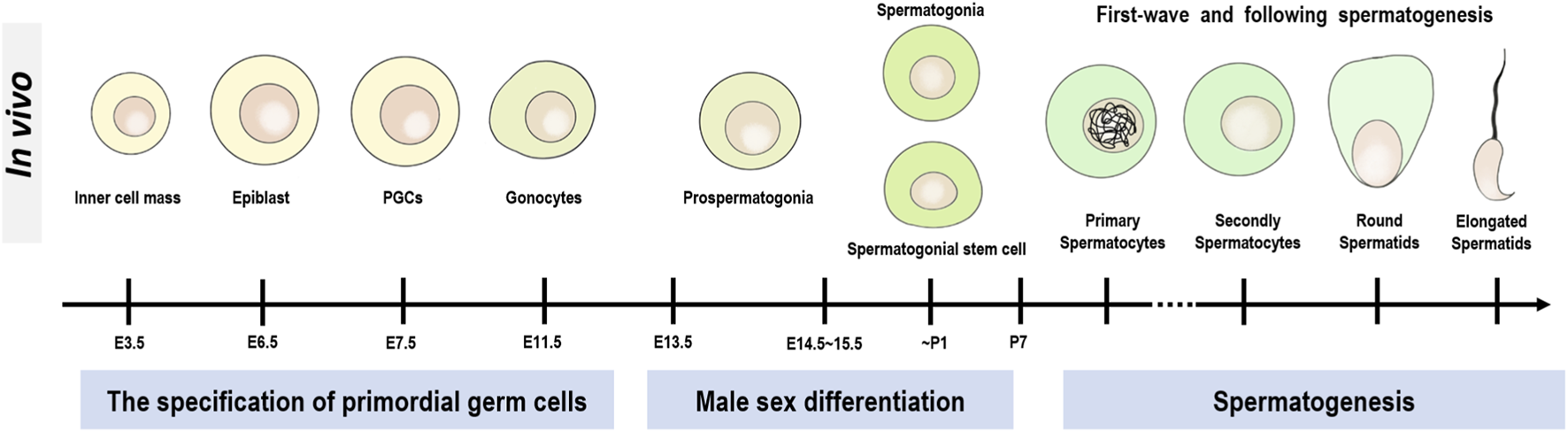

FIGURE 4

Development of GCs in male mice. The entire development of male mice GCs is divided into three main stages, the first being the specification of primordial germ cells (PGCs), the second being the stage of male sex differentiation, and the third being the stage of spermatogenesis.

2.6 Single-cell transcriptomics redefines testicular cellular architecture and functional diversity

Spermatogenesis, the cornerstone of male reproduction, involves the proliferation and differentiation of diploid germ cells into haploid flagellated spermatozoa. This tightly orchestrated process relies on intricate interactions between testicular somatic cells (e.g., SCs and LCs) and GCs. However, its pronounced cellular heterogeneity has posed long-standing challenges in resolving stage-specific cellular populations. While the roles of somatic cells in spermatogenesis are relatively well-defined, the molecular mechanisms governing their developmental maturation remain incompletely elucidated.

The application of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has systematically characterized the heterogeneity of mammalian testicular cells and redefined their cellular atlases. In yaks, pigs, humans, and other species, scRNA-seq has identified GCs subpopulations (spermatogonial stem cells, spermatocytes, and spermatids) and somatic subtypes (SCs, LCs, PMCs) with distinct markers (e.g., UCHL1, SOX9, PRND) (Wang et al., 2023a; Yan et al., 2024). Pseudotime trajectory analyses further indicate a shared progenitor origin for LCs and PMCs (Yan et al., 2024), and functional enrichment demonstrated synergistic regulation between somatic signaling pathways (PI3K-AKT, Wnt) and germline modules (spermatogenesis, DNA binding) (Yan et al., 2024). Cross-species comparisons show that these cell types exhibit both conserved functions and species-specific heterogeneity in pigs, humans, and mice (Zhang W. et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2024).

Compared with other testicular somatic cell types, the developmental trajectory of SCs has been extensively characterized by scRNA-seq. Most studies classify SCs into three stages: immature (during fetal/perinatal phase/neonatal), maturing (during juvenile/prepubertal life), and mature (at puberty and adulthood) (Guo et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020; Su et al., 2025). In human testes, SCs undergo three consecutive stages during normal maturation: Stage_a, b, and c, each with a distinct gene expression profile. Stage_a is characterized by high expression of EGR3, JUN, and NR4A1; Stage_b by S100A13, ENO1, and BEX1; and Stage_c cells primarily express HOPX, DEFB119, and CST9L. This trajectory shows marked age dependence. Stage_a cells are mainly SCs from 2 years old. The numbers of Stage_a and Stage_b cells decrease with age, reaching a minimum at 11 years. Thereafter, functionally mature Stage_c cells emerge and become predominant in late adolescence and adulthood. Functional enrichment analysis further supports the transition between developmental stages. Stage_a cells are significantly enriched for biological processes such as “stem cell differentiation” and “cell number maintenance”, indicating that SCs at this stage primarily exhibit characteristics of stem or progenitor cells. In contrast, Stage_c cells are enriched for processes including “compound rescue in cellular metabolism”, “protein transmembrane transport”, and “phagosome maturation”, indicating that mature SCs primarily function to phagocytose GCs and their metabolic byproducts (Zhao et al., 2020). Guo et al. also identified two immature SCs stages in human testes, designated Immature #1 and Immature #2, which ultimately merged into mature SCs at 11 years of age (Guo et al., 2020). Comparing the two studies, we observe that Immature one resembles Stage_a, while Immature two is closer to Stage_b. In testicular disease research, transcriptomic analyses comparing normal and Klinefelter syndrome (KS) testes indicate that SCs are the most severely affected somatic cell type (Winge et al., 2020). KS SCs are largely arrested at Stage_b and display altered energy metabolism features, such as upregulation of genes associated with oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis, while triglyceride metabolism levels are suppressed (Zhao et al., 2020). They also show broad transcriptional dysregulation, including upregulation of immune-related genes (B2M and MIF (del Campo et al., 2014; Sumaiya et al., 2022)) and reduced expression of sex hormone-regulated gene GNRH1 (Zhao et al., 2020). Notably, X-linked genes are overexpressed in KS SCs. Mahyari et al. provide a key explanation for this phenomenon: they identified a distinct subset of KS SCs lacking XIST expression, this mechanistic defect likely contributes to the upregulation of X-linked genes within KS SCs (Mahyari et al., 2021).

However, scRNA-seq’s reliance on tissue dissociation limits spatial insights into microenvironmental interactions. Recent advances in spatial transcriptomics now enable the characterization of molecular features and intercellular dynamics within native tissue contexts. These technologies map spatially variable genes, delineate cellular neighborhoods, reconstruct communication networks, and detect molecular alterations under pathological conditions (Xu and Chen, 2025). For instance, Slide-seq preserves spatial information to systematically unveil germ-somatic interaction networks (e.g., spermatogonial stem cells adjacent to SCs) within seminiferous tubules (Rajachandran et al., 2023). They also identify conserved (mouse-human) and disease-specific spatial gene modules (e.g., inflammatory signaling in diabetic models), providing a transformative framework for understanding testicular pathologies and therapeutic development (Chen et al., 2021).

3 Influence of SCs on gonadal development

3.1 SCs coordinate gonadal sex differentiation

Gonadal development is a complex process initiated by the migration of PGCs (Yildirim et al., 2020). During embryonic development, PGCs migrate alongside other cell types to the gonadal ridge, where they are induced to differentiate into ovaries or testes in response to different factors (Poulsen et al., 2019). In the early formation of the mouse genital ridge, coelomic epithelial cells express transcription factors WT1, SF1, GATA4, and LHX9, all of which are essential for the gonad formation (Birk et al., 2000; Wilhelm and Englert, 2002; Klattig et al., 2007; Chen H et al., 2017). The supporting cells are the first differentiated somatic cells, playing a pivotal role in orchestrating gonadal sex determination and promoting gametogenesis (Rotgers et al., 2018). These cells differentiate into SCs in the testis and granulosa cells in the ovary (Carré and Greenfield, 2016). This review focuses on the relationship between SCs and male gonadal development.

In mice, sex determination occurs shortly after the coelomic epithelium migrates into the gonadal ridge, simultaneously, the tunica albuginea forms at the junction between the gonad and the coelomic epithelium, preventing cell entry (Karl and Capel, 1998). Compared to other somatic lineages, SCs are almost entirely XY in chromosome composition of the XX-XY mouse chimera (Palmer and Burgoyne, 1991), that is: the SRY acts cell-autonomously in pre-SCs to trigger their differentiation, with further somatic masculinization resulting from SCs signaling. Karl and his colleagues’ research confirms this view, in the testis, SCs differentiate from the first wave of cells entering the gonads, while subsequent progenitor cells differentiate into LCs, PMCs, and TMs (Karl and Capel, 1998). Before differentiation, coelomic epithelial progenitor pools express both SF1 and WT1 (Liu et al., 2016). After differentiation, SCs retain WT1 expression, whereas LCs maintain higher levels of SF1 (Schmahl et al., 2000; Miyabayashi et al., 2013; McClelland et al., 2015). When the WT1 gene is deleted in the gonadal primordium before sex determination, progenitor cells fail to activate the development programs for XX and XY gonads, leading instead to their differentiation into SF1-expressing steroidogenic cells (Chen M et al., 2017). One study indicates that WT1 influences progenitor cell fate towards SCs differentiation by reducing Nr5a1 transcription (Bale and Epperson, 2015).

Testis differentiation is regulated by the sex-determining gene SRY on the Y chromosome, which is expressed only in pre-SCs (Okashita and Tachibana, 2021). At the onset of sex determination, SRY genes are transiently upregulated in SCs (Del Valle et al., 2017). After sex determination, the SRY gene is silenced in mice, while in humans, there are lower levels of SRY gene expression persist even in mature testes (Hanley et al., 2000; Bullejos and Koopman, 2001). SRY gene expression is initiated by transcription factors, including SF1, WT1, GATA4, FOG2 and CBX2, in null mutant of these factors, the gonads exhibit reduced or missing SRY expression, resulting in XY sex reversal (Barbara et al., 2001; Hossain and Saunders, 2001; Tevosian et al., 2002; Miyamoto et al., 2008; Katoh-Fukui et al., 2012; Warr et al., 2012). As well, histone modifications, DNA methylation, and chromatin repression also regulate SRY expression (Kuroki and Tachibana, 2018). The SRY protein binds DNA, activating genes involved in testis development and repressing genes associated with ovary differentiation (Rotgers et al., 2018). The primary target gene of SRY is SOX9. SRY expression activates SOX9, which in turn activates FGF9, promoting the differentiation of pre-SCs (Sekido and Lovell-Badge, 2008; Zhao and Koopman, 2012). Once SCs are formed, they induce FLCs development through hedgehog signaling (Yao et al., 2002), promoting the production of testosterone and insulin-like 3 (INSL3) (Barsoum et al., 2009). This process further induces testicular descent and the masculinization of external genitalia (Hutson, 2013; Roth et al., 2021). In parallel, SOX9 recruits other proteins (PADI, AMH, and PDGS) to facilitate testis development (Otake and Park, 2016; Tsuji-Hosokawa et al., 2018; Lucas-Herald and Mitchell, 2022). However, the absence of SRY expression in pre-SCs leads to the differentiation of the gonad into ovaries (Albrecht and Eicher, 2001). Similarly, abnormal SRY expression causes the genital ridge to develop into ovaries (Larney et al., 2014). Therefore, SRY expressed by pre-SCs is essential for directing gonadal development towards masculinization.

3.2 SCs induce testis cords formation

After the gonadal primordium is established and the fate of the supporting cells is determined, the gonad develops into either ovaries or testes (Poulsen et al., 2019). Once specified for testis development, pre-SCs polarize, aggregate, and assemble around pre-GCs to form SC-GC clusters, then endothelial cells migrate and guide to form testis-specific tubular structures, known as testis cords, which later develop into seminiferous tubules in the adult testis (Rossi et al., 2000; Combes et al., 2009; Svingen and Koopmam, 2013). The maintenance of fetal testis cords is normal testis development (Archambeault and Yao, 2010; Chen et al., 2010; Cool et al., 2012; Zheng et al., 2015). The dramatic changes in testis cords morphology are driven by the rapid proliferation of FSCs, alterations in FSCs number influence the cord structures development, potentially leading to involution and the formation of blind-ending tubules (Bagheri-Fam et al., 2011). The initiation of cord formation requires a large number of FSCs to separate and enclose the GCs within the lumen (Brennan and Capel, 2004; Svingen and Koopman, 2013; Chen et al., 2016). Growing evidence suggests that TGFβ is associated with testis cord formation, though its effects may be indirect. TGFβ plays an important role in regulating and SCs proliferation. The specific deletion of Smad4 (a core component of TGFβ signaling) in SCs leads to defective proliferation and dysplastic testis cords (Archambeault and Yao, 2014). DNA damage binding protein 1 (DDB1) promotes SCs proliferation by activation of the TGFβ pathway, deletion of DDB1 in the FSCs impairs their proliferation and disrupts the coiling of testis cords, leading to smaller testes and reduced sperm production (Zheng et al., 2019). In addition, activin A, produced by FSCs, is a unique regulator of SCs proliferation and cords expansion (Archambeault and Yao, 2010). Taken together, FSCs play a significant role in promoting the elongation and expansion of cord structures, laying the foundation for postnatal testis development.

4 SCs promote spermatogenesis

4.1 SCs maintain the SSCs pools homeostasis

The SSCs niche consists of GCs, SCs, interstitial cells, PMCs, and growth factors from the vascular network (Kanatsu-Shinohara et al., 2007; Oatley and Brinster, 2012). A stable niche facilitates the self-renewal of SSCs and maintains the stem cell pool (Ibtisham et al., 2020). SSCs are located on the basement membrane of the seminiferous tubule, in close contact with SCs (Oatley and Brinster, 2012; Guo et al., 2020). In the presence of SCs, SSCs resume proliferation and undergo several mitotic divisions to form spermatocytes, which give rise to haploid spermatids by meiosis (Zhang et al., 2012). Studies have shown that SCs are activated to produce GDNF in response to FSH, it is a key factor in SSCs self-renewal (Garcia et al., 2017). Ablation of GDNF or its receptors Ret and Gfra1 in SSCs leads to the loss of stem cells and their progeny (Naughton et al., 2006). However, excessive GDNF inhibits differentiation, leading to more undifferentiated SSCs (Hofmann, 2008; Zhang et al., 2012). Furthermore, NOTCH signaling in SCs regulates GDNF expression through HES1 and HEY1 transcription factors, and undifferentiated GCs expressing the NOTCH ligand JAG1 participate in GDNF modulation within the stem cell niche via negative feedback regulation (Garcia et al., 2017). SCs stabilize the SSCs niche by secreting leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and chemokines CXCL12 (Oatley et al., 2011; Oatley and Brinster, 2012; Yang et al., 2021). SCs also secrete fibroblast growth factor (FGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and Wnt5a, which contribute to SSCs self-renewal (Yeh et al., 2011; Hasegawa and Saga, 2014; Ren et al., 2020). These factors are regulated by FSH signaling, which activates the FSH receptor (FSHR) on SCs and targets functional and transcription factors via the cAMP/PKA pathway (Lim and Hwang, 1995; Sharpe et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2022). Interestingly, exogenous increases SCs leads to a corresponding increase in the number of niches (Oatley et al., 2011). However, excessive self-renewal or differentiation of SSCs can disrupt spermatogenesis, ultimately leading to male infertility (Li S et al., 2021).

4.2 SCs create a unique metabolic microenvironment for spermatogenesis

One important event in spermatogenesis is the metabolic cooperation between SCs and developing GCs. After birth, the initial entry into the spermatogenic cycle is triggered by a pubertal upsurge in retinoic acid (RA) (Teletin et al., 2019). RA is an intermediate metabolite of vitamin A (Raverdeau et al., 2012). Within SCs, retinol is oxidized to retinal by RDH10 and then to RA by RALDH1a1 (Theodosiou et al., 2010). RDH10 is essential for the biosynthesis of RA and its absence in SCs results in defective spermatogonia differentiation (Sandell et al., 2012; Tong et al., 2013). RA interacts with heterodimers of the RA receptors (RARs) and the retinoid X receptors (RXRs), binding to RA response elements (RAREs) in target genes, and recruiting co-activators or co-repressors to either induce or inhibit transcription (Mark et al., 2015). Studies have shown that RA deficiency gradually reduces the number of GCs in rats, leaving only SCs and undifferentiated spermatogonia in the seminiferous tubules (Li et al., 2019). Besides, RARα is an important RA member expressed in SCs, when lack RARα, sperm release fails (Vernet et al., 2008). The spermatogenic cycle is supported by subsequent RA pulses (Hogarth et al., 2015; Hofmann and McBeath, 2022). These pulses were observed to influence spermiation at stages VIII–IX of the seminiferous epithelium cycle and were linked to the stage-specific localization of mRNAs associated with retinoid storage, RA synthesis, and degradation (van Pelt and de Rooij, 1990; Vernet et al., 2006). This was confirmed by the discovery of the RA-responsive gene Stra8, which is primarily expressed at stages VIII–IX of the seminiferous cycle (Endo et al., 2015).

The testis is a highly specialized organ characterized by low and unevenly distributed oxygen levels. In the testis, SCs exhibit a high glycolytic flux to produce the elevated lactate levels necessary for GCs development (Qian et al., 2023). Glucose is absorbed from the extracellular space via glucose transporter proteins, particularly GLUT1 and GLUT3, and then converted to lactate, in this process, the lactate dehydrogenase system plays a key role by reversibly catalyzing the conversion of pyruvate to lactate (Custódio et al., 2021). Lactate is then transported across the plasma membrane by monocarboxylate transporters (MCT) to the GCs as an energy source (Bernardino et al., 2019). Studies have shown that during spermatogenesis, increased expression of mitochondrial respiratory-related genes in differentiated GCs leads to pyruvate and lactate replacing glucose as the fuel for mitochondrial respiration in spermatogonia and spermatocytes (Mita and Hall, 1982; Nakamura et al., 1984; Ren et al., 2022). Furthermore, intratesticular injection of lactate significantly improved spermatogenesis in the testes of adult cryptorchid rats (Courtens and Plöen, 1999). In this metabolic environment, SCs are co-regulated by both external and internal factors, such as insulin, sex hormones, cytokines, and AMP-activated kinases (Boussouar and Benahmed, 2004). Research suggests that a lack of insulin decreases the expression of LDHA, which in turn reduces the conversion of pyruvate to lactate and MCT4 (Oliveira et al., 2012). These findings align with another study, which demonstrated that insulin and FSH increase lactate production in ISCs, suggesting a positive correlation between insulin levels and lactate production (Oonk et al., 1985).

4.3 The blood-testis barrier (BTB) established by SCs is involved in spermatogenesis

The BTB comprises multiple protein complexes between adjacent SCs, including tight junctions (TJ), ectoplasmic specialization (ES, specific adhesion junctions in the testis), gap junctions (GJ) and desmosome junctions (DJ) (Mao et al., 2020). TJ forms barriers dividing the seminiferous epithelium into basal and apical compartments, preventing the diffusion of soluble substances and macromolecules into the apical compartment and limiting the translocation of proteins and lipids between these compartments (Mruk and Cheng, 2015). SCs express occludin and claudin-11, the major regulators of TJ (McCabe et al., 2016). The basal compartment contains SSCs, spermatogonia, and preleptotene spermatocytes (Wanjari and Gopalakrishnan, 2024). Preleptotene spermatocytes enter the apical compartment through the transient opening of the BTB junction complex, where they undergo two meiotic divisions to form spermatocytes, eventually becoming elongated spermatozoa, which enter the lumen of the seminiferous tubules (Cheng and Mruk, 2012). To prevent the self-antigens of spermatocytes and spermatozoa in the apical compartment from triggering an immune response, the BTB isolates many GCs specific antigens, acting as an immune barrier for spermatogenesis (Luaces et al., 2023). ES is mainly composed of cadherin-catenin complexes and can be categorized into two types based on their location: one is basal ES between the SCs (Qian et al., 2014). The other is the apical ES between SCs and spermatids, they interact with the acrosomal region of the spermatid and promote rapid elongation and maturation by mechanically grasping the head of the spermatids (Mruk and Cheng, 2004; Berruti and Paiardi, 2014; Qian et al., 2014). SCs participate in spermatogenesis by providing nutrients (sugars, amino acids) and secreting cytokines (Chojnacka et al., 2016; Luca et al., 2018b). GJ-mediated intercellular substance transport realizes this function in SCs, and GJ can selectively release substances according to those required by GCs at different times (Haverfield et al., 2014; Ni et al., 2019), this regulation of bioactive substance concentration provides a suitable microenvironment for spermatogenesis (O’Donnell et al., 2011). In addition, GJ expresses abundant connexin43 (Pointis et al., 2010), which interacts with Plakophilin2, β-catenin, N-cadherin, and c-Src to mediate signaling during the reconstruction of the seminiferous epithelium in spermatogenesis and regulate the migration of preleptotene spermatocyte (Carette et al., 2010; Gerber et al., 2016).

The BTB is a highly dynamic ultrastructure that undergoes cyclic reorganization in response to various factors, facilitating the completion of meiosis in leptotene spermatocytes (Mruk and Cheng, 2015; Liu et al., 2024). It has been shown that TGF-β and TNF-α regulate BTB reorganization by activating the MAPK signaling pathway, promoting protein endocytosis and ectosome degradation, which interfere with TJ barrier function (Xia et al., 2009; Liu J et al., 2018). Besides, spermatocytes induce SCs to produce and highly IL-1 during stage VIII of the spermatogenic epithelial cycle, regulating the BTB reorganization and spermatozoa release (Sarkar et al., 2008). Androgens promote not only the completion of meiosis and development of spermatocytes (Christin-Maitre and Young, 2022) but also the production of TJ proteins, which maintain the SCs’ barrier function and BTB integrity (McCabe et al., 2012; Kabbesh et al., 2022). In the testis, where androgen concentration fluctuates markedly, the BTB isolates seminiferous tubules from the interstitial tissue, allowing SCs to express androgen-binding protein (ABP) (Walker, 2010; Chen T et al., 2022; Washburn and Dufour, 2023). Androgen binds to ABP, alleviating fluctuations and enabling stable release (Ma et al., 2015). Androgens regulate GCs adhesion and sperm release through the activation of a non-classical testosterone pathway, binding to DNA regulatory elements via androgen receptors (AR) on SCs (Holdcraft and Braun, 2004; Cheng et al., 2007; Deng et al., 2017). Transferrin, located on SCs, transfers iron ions from the blood to cell membranes and transmit them to GCs at different stages, promoting the development, differentiation, and maturation of GCs (Yefimova et al., 2008). Additionally, the BTB confers polarity to the spermatogenic epithelium and guides GCs migration, ensuring proper directional movement of spermatogenic cells (Liu Y et al., 2018). In summary, the BTB established by SCs contributes to spermatogenesis. when damaged, it leads to abnormalities in the testicular microenvironment, including disorganization and loss of polarity of SCs and GCs, disrupting normal spermatogenesis in the testis.

4.4 Sperm production and output are directed by SCs

Normal spermatogenesis depends on specific signals from the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (HPGA). The hypothalamus produces of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which stimulates the anterior pituitary to synthesize and secrete FSH and LH through activation of its receptor (GnRHR) (Lenzi et al., 2009; Smith and Walker, 2014). However, GCs do not express FSH receptors (FSHR) and must signal through SCs to produce cytokines and metabolites that promote GCs maturation (Meachem et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2015). Specifically, binding of FSH to FSHR induces GTP-binding protein in SCs to recruit other molecules, stimulate Gαs or inhibit Gαi, and regulate the cAMP synthesis, subsequently, cAMP activates the downstream transcription factor CREB, maintaining the supportive role of SCs in spermatogenesis (Scobey et al., 2001). LH acts on receptors (LHR) on LCs to promote testosterone synthesis by inducing proliferation, differentiation and maturation of LCs (Smith and Walker, 2014). Testosterone induces spermatogonia to complete meiosis via the AR on SCs, ensuring that GCs acquire the ability to divide (De Gendt et al., 2004; Larose et al., 2020). Testosterone deficiency alters the expression of proteins involved in RNA processing, modification, apoptosis, oxidative stress, and meiosis thereby impeding spermatogenesis (Stanton et al., 2012). Damage to FSH or AR on SCs leads to GCs apoptosis and reduced spermatogenesis efficiency (Ruwanpura et al., 2010; Willems et al., 2010; De Gendt et al., 2014). One study demonstrated that LHR knockout mice lacked testosterone production and exhibited impaired spermatogenesis (Lei et al., 2001), whereas exogenous testosterone administration restored spermatogenesis (Oduwole et al., 2014). It is suggested that SCs play a critical role in transducing of FSH and androgen signaling to coordinate spermatogenesis.

During spermatogenesis, SCs continuously alter their function, cytoskeleton, specialized junctions, gene and protein expression to provide nutrients and physical support to GCs at various stages (Dunleavy et al., 2019). As sperm mature, they need to detach from SCs and enter the seminiferous tubules, eventually being transported to the epididymis for further processing (O’Donnell, 2014). During sperm release, SCs also act as “quality inspectors” by screening and phagocytosing abnormal spermatozoa (O’Donnell et al., 2011). This process dependent on the binding of the scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-B1) in SCs to the membrane phospholipid phosphatidylserine on the target cell (Nakagawa et al., 2005; Zohar-Fux et al., 2022). Phosphatidylserine is normally confined to the inner leaflet of the bilayer membrane, but is transferred to the outer leaflet and exposesd on the cell surface during apoptosis (Park and Kim, 2019). In the process of GCs deformation, a large amount of waste is produced, and SCs recycle this waste for their own energy production (Regueira et al., 2018). Sperm are highly sensitive to microenvironmental changes, and disruptions in SC signaling pathways or drastic hormonal changes can lead to sperm release failure (Kumar et al., 2018). The GCs undergo spermatogenesis to form species-specific elongated spermatids, which are eventually released from the seminiferous epithelium (Du et al., 2021). In the mouse testis, a complete spermatogenic cycle occurs along the seminiferous tubules, while in humans, multiple cycles are intertwined (Johnston et al., 2008; O’Donnell et al., 2022a), meaning that human SCs undergo a more complex process during spermatogenesis.

5 SCs determine the fate of LCs

5.1 SCs promote LCs differentiation and maturation

At least two types of LCs are present in mammalian embryonic and postnatal testis: FLCs and ALCs (Heinrich and DeFalco, 2020). During early embryonic development, pre-SCs promote the formation of fetal PLCs (Rotgers et al., 2018), once FLCs are appointed, their dependence on FSCs diminishes (Fouchécourt et al., 2016; Mäkelä and Hobbs, 2019). Cytokines secreted by FSCs are involved in the proliferation and survival of FLCs, including KIT ligand (Tsikolia et al., 2009), Desert Hedgehog (DHH) (Yao et al., 2002), and PDGF-A (Brennan et al., 2003). Studies have shown that knocking down DHH in mice reduces the number of FLCs (Yao et al., 2002), while activation of DHH induces the expression of SMO and the downstream transcription factors GLI-1, promoting the proliferation of FLCs (Barsoum et al., 2013). FLCs express PDGFRα, which promotes their differentiation in response to PDGF-A secreted by FSCs (Basciani et al., 2002; Brennan et al., 2003). In contrast, the absence of PDGF-A leads to developmental defects in ALCs but does not affect the number of FLCs (Gnessi et al., 2000). Male gonadal differentiation is facilitated by the interaction of FLCs and FSCs (Svingen and Koopman, 2013; Shima, 2019). Although both FLCs and ALCs are capable of producing androgens (Val et al., 2003), testosterone during the fetal period requires conversion by the 17β-HSD enzyme in FSCs, as FLCs only synthesize androstenedione (O’Shaughnessy et al., 2002). Androgens produced by FLCs and FSCs contribute to the development of the epididymis, seminal vesicles, and vas deferens (O’Donnell et al., 2022b). During the fetal period, genital tissues produce 5α-reductase, which converts testosterone produced by FSCs to dihydrotestosterone, inducing the development of the male urethra, prostate, and penis (Kim et al., 2002; Markouli and Michala, 2023).

After birth, ALCs gradually replace FLCs and begin synthesizing and secreting androgens at puberty (Shima, 2019). The genealogical relationship between FLCs and ALCs has not been fully elucidated. Some scholars believe that ALCs originate from stem cells and are independent of FLCs (Habert, 1993; Lo et al., 2004; Ge et al., 2006; Griswold and Behringer, 2009). Others suggest that a subset of the ALCs arises from a subpopulation of de-differentiated FLCs that remain after birth (Kilcoyne et al., 2014; Kaftanovskaya et al., 2015; Shima et al., 2015; Shima et al., 2018), which is regulated by WT1 in SCs (Wen et al., 2014). WT1 is highly expressed in SCs and induces LCs proliferation and differentiation by regulating DHH in SCs, promoting DHH binding to the Ptch1 receptor on LCs (Chen et al., 2014; Min et al., 2022). WT1 knockout in mice leads to reduced numbers of ALCs, downregulation of steroidogenic enzyme expression, and decreased testosterone levels (Chen et al., 2014). Additionally, Rebourcet’s study found that the number of SCs during development predicts the number of LCs in the adult testis (Rebourcet et al., 2017). Complete ablation of SCs in neonates restricts the differentiation and development of the LCs population (Rebourcet et al., 2014a).

5.2 SCs contribute to LCs steroid hormone synthesis

At the onset of spermatogenesis, SCs play a crucial role in providing continuous support to LCs, ensuring their optimal functionality. Studies have shown that the removal of ASCs leads to the apoptosis of ALCs and a significant reduction in their cell number (Rebourcet et al., 2014b). This suggests a dependency between the number of SCs and LCs. SCs secrete various cytokines, such as LIF, PDGF, IGF1, FGF2, TGF, Kit ligand, and Notch ligand, which regulate LCs development and steroidogenesis (Hu et al., 2010; Martin, 2016; Chen M et al., 2017). Among them, IGF1, FGF2 and TGF increased the expression of StAR, promoting the transfer of cholesterol from the outer to the inner mitochondrial membrane to form pregnenolone (Manna et al., 2006). Additionally, SCs can convert testosterone to estrogen via aromatase, which negatively regulates steroidogenesis (Zhang Z. et al., 2022). In co-cultured studies, a reciprocal relationship between SCs and LCs was observed, suggesting that SCs might influence LCs function. In the co-culture system, LCs exhibit a more developed smooth endoplasmic reticulum and higher testosterone content (Saez et al., 1989), while medium collected from SCs increased LCs steroid hormone synthesis (Khan and Rai, 2005). In addition, reducing estrogen levels in SCs promotes testosterone synthesis in co-cultured LCs (Deng et al., 2018). LCs can also influence the metabolic activity of SCs by secreting cytokines (Khan and Rai, 2004). SCs release numerous exosomes, which can cross the BTB to act on LCs functions, providing new evidence for exosomal communication between SCs and LCs. Ma et al. demonstrated that exosomes secreted by SCs promote the survival of LCs by activating the CCL20-AKT pathway (Ma et al., 2022). Exposure to PFOS significantly increases the expression level of miR-9-3p in both SCs and their exosomes, and this miRNA can be transferred to LCs, where it targets and suppresses StAR expression, thereby inhibiting the testosterone synthesis and secretion (Huang et al., 2022). Furthermore, Liang found that miR-145-5p can be transported to LCs via SCs-derived exosomes and exert its function by targeting the SF-1 gene, which in turn downregulated the expression of steroidogenesis-related genes, ultimately inhibited testosterone production (Liang et al., 2021).

In summary, SCs play a crucial role in regulating the development and function of both FLCs and ALCs. The interactions between these 2 cell types are essential for the spermatogenesis, and their crosstalk may underlie various male reproductive dysfunctions. Further research is needed to elucidate the specific mechanisms of these interactions.

6 Effects of SCs on other somatic cells in the testis

6.1 Influence of SCs on PMCs

PMCs are the least studied cells in the testis, and their origin remains controversial. Most researchers believe that PMCs and LCs originate from a common progenitor, a mesenchymal stem cell (Ademi et al., 2022; Aksel et al., 2023; Robinson et al., 2023; Tao et al., 2023), This was also confirmed by Guo useing single-cell transcriptome sequencing, who found that in human testis, LCs and PMCs share a common progenitor, and these progenitor cells co-express LCs and PMCs markers (Guo et al., 2020). SCs are essential for the proliferation and differentiation of PMCs. It has been shown that DHH secreted by SCs promotes the proliferation and differentiation of PMCs, and knocked out of the DHH gene in SCs results in impaired PMCs during development in the testis (Pierucci-Alves et al., 2001). DHH signaling confer polarity to PMCs in organoid culture studies and promotes reorganization of spermatogenic tubules in vitro (Min et al., 2022). SCs also produce WT1, and early reports indicated that specific knockdown of WT1 on SCs using Amh-Cre mice disrupts fetal testicular cords formation (Gao et al., 2006). Wen and colleagues discovered that WT1 regulates the development of FLCs and interstitial progenitor cell lineages through Notch signaling and plays a role in PMCs development, and that the absence of WT1 in SCs leads to reduced differentiation of PMCs and impedes fetal testis compartmentalization (Wen et al., 2016). During testicular cord assembly, PMCs secrete collagen I, collagen IV, and fibronectin, while SCs produce and deposit collagen IV and small amounts of laminin, forming the basal lamina of the seminiferous tubules, which is important for maintaining the ecological niche stability of SSCs after birth (Creemers et al., 2002; Kanatsu-Shinohara et al., 2003; Zhou et al., 2019). The stable number of neonatal SCs facilitates the maintenance of PMCs polarity. When SCs are ablated, PMCs depolarization accelerates, leading to disorganized seminiferous tubules morphology (Rebourcet et al., 2014a; Tao et al., 2023). In the adult testis, SCs ablation does not reduce the number of PMCs but diminishes their activity, which subsequently induces the loss of ALCs (Rebourcet et al., 2014b). It is evident that SCs are crucial for PMCs differentiation and contribute to the maintenance of normal PMCs function in adulthood.

6.2 SCs impact on TMs

The testis is a unique immune microenvironment where dendritic cells, mast cells, lymphocytes, and TMs play important roles (Pérez et al., 2013; Bhushan et al., 2015; Bhushan et al., 2020). In the testis, immune responses are generally suppressed, which protects GCs from the immune system and sustaining fertility (Fijak et al., 2011; Li et al., 2012). SCs secrete various immunomodulatory factors that are essential for the function of interstitial immune cells (Luca et al., 2018a). However, SCs derived immunomodulators require androgens support, and when AR are absent in SCs, TJ in SCs are damaged, leading to changes in interstitial immune cells and loss of immune privilege (Meng et al., 2011). TMs constitute a significant portion of the testicular immune microenvironment and are key contributors to its immune function (Bhushan et al., 2020). TMs are present in early undifferentiated fetal gonads (DeFalco et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2021) and are recruited by FSCs to promote organ-specific developmental functions during a narrow time window of embryonic development (Gu et al., 2023). Activin A, a member of the TGF-β superfamily, is primarily secreted by SCs and exerts both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects (Hedger and de Krester, 2013; Wijayarathna and de Kretser, 2016), promoting the production of various inflammatory mediators by TMs (de Kretser et al., 2012; Morianos et al., 2019). Activin A also plays a crucial role in regulating macrophage development and function (Hedger and de Kretser, 2013) and helps maintain TMs numbers and testicular immune privilege (Biniwale et al., 2022). It has been long believed that SCs protect GCs from immune attacks by forming the BTB (Kaur et al., 2014; França et al., 2016). However, recent studies suggest that SCs can produce GCs-specific proteins and release them into the interstitial space, potentially promoting peripheral immune tolerance (Tung et al., 2017; O’Donnell et al., 2021). These findings reveal the complex mechanisms by which SCs maintain testicular immune privilege.

Previous research has focused primarily on the interactions between SCs and GCs. However, the specific mechanisms and pathways by which SCs regulate other somatic cells in the testis remain unclear and warrant further investigation. SCs secrete various specific mRNAs and proteins that affect only neighboring somatic and GCs but may also regulate overall male reproductive health. Therefore, an in-depth study of SC-specific gene expression will help elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which SCs modulate the function of somatic cells within the testicular microenvironment.

7 Dysfunction of SCs affects male reproduction

SCs are the “custodians” of the spermatogenic microenvironment, the integrity of their structure and function directly determines the efficiency of spermatogenesis and male fertility. The principal drivers affecting SC function fall into three categories: genetic factors, environmental exposures, and lifestyle/dietary patterns. These factors can disrupt BTB, perturb the HPG axis and immune homeostasis, trigger oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage, and remodel metabolic and paracrine signaling, thereby weakening nutritional and protective support for GCs and ultimately leading to impaired spermatogenesis.

7.1 Key genes regulation

In most mammals (including humans and mice), early gonadal development is non-dimorphic, generating a primordial, bipotential gonad. Its fate is determined by expression of the sex-determining gene SRY on the Y chromosome (Chen R et al., 2022). SRY cooperates with NR5A1/SF1 to bind the testicular enhancer core (TESCO) sequence, rapidly initiating SOX9 expression and thereby establishing the SC lineage (Sekido and Lovell-Badge, 2008; Gonen et al., 2017). Once activated, SOX9 forms a positive feedback loop through prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) and FGF9, and directly inhibits the RSPO1/WNT4/β-catenin pathway that drives ovarian differentiation, ensuring testis cord formation and AMH expression (Rotgers et al., 2018; Chen and Gao, 2022). During this process, FGF9/FGFR2 signaling is critical for promoting proliferation of precursor cells and for inhibiting WNT4 to stabilize the male developmental trajectory (Bagheri-Fam et al., 2017). Studies also show that loss of RSPO1 can cause abnormal expansion of androgen-producing cells (Rotgers et al., 2018). The upstream regulator WT1 functions as a hub with multiple roles, it guides somatic cells of the genital ridge toward differentiation into SCs or FLCs during early development; after sex determination, it maintains cell polarity and BTB function by activating non-canonical Wnt pathways (Wnt-PCP and Wnt/Ca2+), while continuously inhibiting β-catenin signaling. Experiments confirm that absence of Wt1 during the fetal or prepubertal period severely disrupts testicular architecture and LCs development, resulting in male infertility (Rotgers et al., 2018; Liang et al., 2019). Notably, WT1 exerts time-dependent bidirectional control over SF1 expression (enhancing it before sex determination but antagonizing it in SCs thereafter), highlighting WT1’s central role in maintaining lineage stability and the testicular microenvironment (Wilhelm and Englert, 2002; Chen et al., 2012).

In the late differentiation phase and after birth, DMRT1 becomes essential for preserving SCs identity. From E12.5 onward, DMRT1 consolidates male fate by continuously repressing ovarian genes such as Wnt4 and Foxl2, while upregulating Ptgds, Fgfr2, and Gdnf (Matson et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2020). Postnatal loss of DMRT1 leads to transdifferentiation of SCs into granulosa-like cells and can even trigger reversal of gonadal fate (Matson et al., 2011). Furthermore, absence of Raptor, a core component of the mTORC1 pathway, induces dedifferentiation of ASCs, suggesting that nutrient sensing and epigenetic programs jointly establish a metabolic gate that secures mature cellular homeostasis (Xiong et al., 2018). At the hormone regulation level, NR5A1/SF1 directly activates the AMH promoter, and its specific deletion in SCs also downregulates AR expression and delays cellular maturation (Kato et al., 2012; Anamthathmakula et al., 2019), providing a molecular explanation for phenotypes observed in certain pathogenic NR5A1/SF1 variants. X-linked loss-of-function mutations in AR are the predominant cause of androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS), a prototypical SC-related disorder/difference of sex development (DSD). In complete AIS, AR variants are detectable in more than 95% of cases, underscoring the indispensability of this pathway for terminal SCs maturation (Delli Paoli et al., 2023; Karseladze et al., 2024). Importantly, the molecular underpinnings of 46,XY DSD are highly heterogeneous. More than 60 genes have been implicated, and approximately 60% of cases can be attributed to mutations in AR, SRD5A2, or NR5A1/SF1 (Delot and Vilain, 2021; Zheng et al., 2023). A recent study further identified DHX37, MYRF, and PPP2R3C as 46,XY DSD-associated genes. DHX37 encodes a DEAD-box RNA helicase; hotspot mutations within its RecA-like domains (e.g., p.R308Q, p.R674W) are strongly associated with gonadal dysgenesis, cryptorchidism, and micropenis, suggesting that ribosome biogenesis, cell-cycle control, and the NF-κB and Wnt signaling pathways may collectively mediate the impact of DHX37 on the SCs lineage (McElreavey et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2025).

7.2 Etiologies of sertoli cell-only syndrome

Sertoli cell-only syndrome (SCOS) is the most common and severe subtype of nonobstructive azoospermia (NOA), with a detection rate of 26.3%–69.6% among NOA patients, thereby posing a serious threat to male reproductive health (Chen T et al., 2022). The etiology of SCOS is complex and involves genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors, including Y-chromosome microdeletions, chromosomal abnormalities, cryptorchidism, varicocele, radiotherapy, and harmful occupational exposures (Ghanami Gashti et al., 2021; Hamoda et al., 2025). Studies indicate that karyotypic abnormalities (e.g., Klinefelter syndrome) and microdeletions in the Y-chromosome azoospermia factor (AZF) regions are key markers for SCOS subtyping. The AZF loci are located on the long arm of the Y chromosome (Yq11). There are five fragile sites on Yq11, and their disruption can lead to recurrent deletions of large DNA segments ranging from 0.8 Mb to 7.7 Mb (Wang et al., 2023b; Krausz et al., 2024). Histologically, seminiferous tubules in SCOS contain only SCs, with a complete absence of GCs, and are often accompanied by tubular atrophy and basement membrane thickening (Ghanami Gashti et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023a). In a minority of cases, focal “residual spermatogenesis” may be present, offering the possibility of biological fatherhood via testicular sperm extraction (TESE) combined with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), although this also carries genetic risks for the offspring (Ghanami Gashti et al., 2021; Krausz et al., 2024). Patients with SCOS typically exhibit elevated FSH with largely normal LH and testosterone levels, suggesting compensatory pituitary feedback for spermatogenic failure and relatively preserved LC function (Ghanami Gashti et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023a). SCOS can be classified as primary or secondary: the former originates from defects in the directed migration or differentiation of PGCs during embryogenesis and most commonly presents as complete SCOS (cSCOS). The latter relates to abnormalities in the maintenance, self-renewal, or differentiation of SSCs after birth, or to dysfunction of the somatic niche, typically presenting early as incomplete SCOS (iSCOS) and potentially progressing over time to cSCOS. The evolution of iSCOS into cSCOS has been demonstrated in multiple genetically engineered models (Wang et al., 2023b), indicating that “intrinsic SSC defects” and “niche failure” are two key mechanisms that converge on a common terminal phenotype. In addition to the classic AZF deletion, aberrant expression of genes such as NANOS1, SYCP3, TEX11, and HSF has been implicated in SCOS (Chen T et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023a). Transcriptomic analyses further show that downregulated genes in SCOS are enriched in cell-cycle and reproduction-related pathways, whereas upregulated genes are associated with inflammation and immune responses. Protein–protein interaction network analysis identifies hub genes centered on CCNB1, AURKA, and CDC20, these all belong to suppressed cell-cycle modules, suggesting that spermatogenic arrest is accompanied by marked cell-cycle dysregulation (Chen R et al., 2022). Additionally, immune cell infiltration is increased in SCOS samples, and CD56bright NK cells are significantly associated with multiple hub genes, indicating that “cell-cycle arrest” and “activation of the immune microenvironment” together constitute the dual molecular underpinnings of SCOS. In addition, noncoding RNAs participate in niche imbalance and the regulation of SSC fate by modulating signaling pathways such as Notch, EGFR, and LIF/IL-6, thereby providing new insights for a comprehensive elucidation of SCOS pathogenesis (Hofmann and McBeath, 2022; Wang et al., 2023b).

7.3 Sertoli cell tumor

Sertoli cell tumor (SCT) is the second most common testicular sex cord–stromal tumor in males and accounts for approximately 1% of all testicular neoplasms. Based on histopathological features, SCTs are categorized into two types: not otherwise specified (NOS) and large cell calcifying SCT (LCCSCT) (Patrikidou et al., 2023). LCCSCT occurs in prepubertal and postpubertal patients, and some of them are associated with cancer-predisposition syndrome and germline variations (Al-Obaidy et al., 2022). SCT may arise from system-level imbalances of SCs in the multilayered development and homeostatic regulatory network and involves three interrelated pathological modules. First, the non-classical Wnt/PCP pathway regulated by WT1 maintains cell polarity and lineage stability, whereas the classical Wnt/β-catenin pathway is physiologically restrained to preserve the resting state and the BTB. When this regulatory axis is perturbed, it drives aberrant proliferation and dedifferentiation of SCs (Wang et al., 2013; Lobo et al., 2023). Evidence indicates that miR-202-3p targets LRP6 and cyclin D1 within the Wnt/β-catenin cascade, thereby restraining cell-cycle progression (Yang et al., 2019), suggesting that “enhancement of Wnt signaling” together with “cell-cycle propulsion” constitutes a key pro-proliferative circuit in SCs whose molecular features closely align with tumorigenesis. In addition to abnormalities in the Wnt pathway, loss of the homeostatic functions of developmental transcription factors further accelerates malignant transformation; for example, SF1/NR5A1 regulates the survival and ordered proliferation of embryonic SCs through the MDM2/TP53 signaling pathway (Anamthathmakula et al., 2019), and imbalance of this pathway may attenuate TP53-dependent checkpoint control, permitting expansion of aberrant clones. Finally, epigenetic disequilibrium amplifies these processes. Pervasive histone acetylation abnormalities have been observed in testes with SCOS (Ghanami Gashti et al., 2021), indicating systemic alterations in the SC microenvironment and chromatin openness; this provides an epigenetic basis for sustained activation of pro-proliferative transcriptional programs, including the Wnt–cyclin D axis. Notably, some SCOS pathological specimens show loss of epithelial characteristics in SCs accompanied by disruption of seminiferous tubule architecture (Peirouvi et al., 2021). This deterioration of the tissue microenvironment confers spatial growth advantages and immune-evasion conditions to abnormal clones, providing a plausible explanation for the clinically observed low-grade malignant tendency and risk of local recurrence in SCT.

7.4 Systemic aging

SCs are the most age-sensitive cell type in the testis; compared to young individuals, the number of age-related differentially expressed genes increases in elderly testes (Huang et al., 2023). Systemic factors associated with aging, along with changes in the local microenvironment, reduce the number of SCs and impair their function, further affecting spermatogenesis (Rebourcet et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2024). At the ultrastructural level, aging leads to changes in SCs, including abnormal nuclear morphology, periodic loss of organelles, relaxation of the endoplasmic reticulum, and enlarged lysosomes, resulting in a decline in their function (Santiago et al., 2019).

Specifically, aging leads to lipid metabolism disorders in SCs. Studies have shown that genes involved in sterol biosynthesis and transport (such as Msmo1, Sqle, Tspo, Hmgcr, Elovl5, Fads1, and Dhcr24) are upregulated in aged SCs (Nie et al., 2022), indicating the accumulation of lipid inclusions within SCs (Paniagua et al., 1987; Santiago et al., 2019). Sulfogalactosylglycerolipid (SGG) is essential for spermatogenesis (Tanphaichitr et al., 2018), and arylsulfatase A (ARSA) produced by SCs can degrade SGG in apoptotic GCs and their remnants (Kongmanas et al., 2021). When SCs fail to degrade SGG promptly, lipid droplet accumulation occurs. However, whether reduced ARSA activity in senescent SCs leads to SGG accumulation, accompanied by higher ROS levels, thereby affecting spermatogenesis, requires further investigation. Moreover, SCs secrete various signaling molecules, and their secretory capacity gradually declines with aging. For example, GDNF secreted by SCs regulates the self-renewal of SSCs (Parekh et al., 2019), but its expression levels in SCs decrease with advancing age (Ryu et al., 2006). This may be one of the key reasons for the reduced number of SSCs in aged individuals. Additionally, periodic RA pulses serve as key regulators of spermatogenesis (Endo et al., 2017; Saracino et al., 2020). The RA receptor signaling pathway is significantly decreased in aged SCs (Huang et al., 2023). This suggests that aged SCs have a reduced capacity to guide spermatocyte differentiation, resulting in slower GCs entry into meiosis. scRNA-seq analysis further revealed that key transcription regulators such as WT1, GATA4, and AR exhibited significantly reduced expression levels in aged SCs (Huang et al., 2023). This will affect the expression levels of FYN, a gene closely associated with GCs’ survival and differentiation (Luo et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2022). In addition to secretory functions, SCs also have prominent phagocytic functions (Tysoe, 2024). During spermatogenesis, SCs are responsible for clearing metabolic waste and residual cytoplasm generated throughout the process (Yefimova et al., 2018; Tysoe, 2024). However, in aged animals, the seminiferous tubules harbor substantial accumulations of residual bodies and arrested round spermatids that have not been cleared. This buildup may disrupt the microenvironmental homeostasis of the seminiferous tubules and impede spermatogenesis (Dong et al., 2016). Additionally, increased expression of inflammation-related genes (such as Il1a, Il6st, Ifi27, Ccl2, and Mif) was observed in aged SCs (Nie et al., 2022). Given the nutritional and supportive role of SCs in the GCs lineage, these altered transcriptional levels indicate a decline in overall metabolic function and heightened inflammation in aged SCs, thereby impairing their capacity to support GCs development.

7.5 Endocrine disrupting chemicals

Endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are pollutants widely present in the environment, originating largely from the pharmaceutical, cosmetics, and packaging industries. These substances can enter the human body, interfere with normal endocrine activity, and adversely affect male reproductive health (Feijo et al., 2025). In the male reproductive system, EDCs impair the function of SCs by inhibiting proliferation, disrupting the cytoskeleton and BTB integrity, and interfering with adhesion junctions between SCs and GCs, ultimately leading to testicular dysfunction and infertility (Mitra et al., 2017; Stukenborg et al., 2021; Adegoke et al., 2023). Common EDCs that may adversely affect male reproductive health include cadmium, phthalates, bisphenol A (BPA), perfluorinated compounds, pesticides, among others (Gao et al., 2025).

As industrial development continues, heavy metals are increasingly released into the environment, either intentionally or unintentionally, harming human and animal health through inhalation or consumption of contaminated water sources. Cadmium (Cd), a prevalent environmental pollutant from industrial processes and cigarette smoking, has been shown to accumulate in the body, particularly in the testes, despite a daily intake as low as 1.06 μg/kg body weight (Wan et al., 2013). This accumulation can disrupt various bodily functions. SCs are a primary target of Cd, pregnant rats on GD12 received low-dose intraperitoneal injections of Cd, which led to decreased expression DHH and FSHR genes in SCs, although it did not significantly affect SCs number, it may have impacted the development and function of other testicular cells (Li et al., 2018). Cd exposure in lactating rats led to vacuolization of SCs and loss of spermatogenic epithelial cells in adult rats (Bekheet, 2011). Additionally, Cd induces excessive autophagy in SCs, leading to apoptosis and an increase in reactive ROS (Chen et al., 2024). SCs support spermatogenesis by forming the BTB (Luaces et al., 2023). However, in rats, Cd disrupts BTB structure by upregulating TGF-β3, which activates p38MAPK signaling (Lui et al., 2003; Wong et al., 2004). Focal adhesion kinase (FAK), a non-receptor protein tyrosine kinase, regulates the TJ proteins (such as occludin and ZO-1) in the BTB, and Cd downregulates FAK expression, damaging the BTB and further inhibiting spermatogenesis (Venditti et al., 2021; Li et al., 2024).

BPA, a prototypical environmental estrogen, is a significant EDC that negatively affects male reproductive health. Most human exposure to BPA occurs through household items, medical devices, and food packaging made from polycarbonate plastics (Corpuz-Hilsabeck and Culty, 2023). BPA can induce metabolic disorders and abnormal spermatogenesis through mechanisms including mimicking estrogenic activity, interfering with DNA methylation, and altering enzyme activities (Barbagallo et al., 2020; Deng et al., 2024). Numerous studies indicate that the reproductive toxicity of BPA primarily arises from impairment of SCs function (Corpuz-Hilsabeck and Culty, 2023). During fetal development, the effects of BPA are complex. One study reported that intrauterine BPA exposure downregulates the expression of AMH, a marker of male fetal SCs, and reduces testosterone levels, suggesting impaired function of both SCs and LCs (Lv et al., 2019). However, an organ culture study observed that BPA exposure increased numbers and markers of FSCs in mice, while GCs and FLCs were significantly reduced, the authors therefore hypothesized that BPA may disrupt the normal proportions and cellular communication among various testicular cell types, and that this imbalance in cellular niche serving as a key mechanism of reproductive dysfunction (Park et al., 2021). Rossi et al. examined primary SCs isolated from 7-day-old postnatal mice and found that exposure to 0.5 μM BPA enhanced endocannabinoid (eCB) signaling, a lipid-based signaling system that acts on cannabinoid receptors and is known to regulate spermatogenesis and sperm fertilization capacity. Because FSH regulates eCB signaling in ISCs, the authors propose that BPA may disrupt FSH signaling (Rossi et al., 2020). In a TM4 cell model, BPA showed a biphasic effect: micromolar levels of BPA inhibited cell proliferation, whereas nanomolar levels stimulated energy metabolism, evidenced by elevated ATP levels and increased mitochondrial activity (Ge et al., 2014). Additionally, BPA induces apoptosis in adolescent rat SCs (PND 18–22) via activating the Fas/FasL and p38/JNK pathways (Qi et al., 2014). Co-exposure to BPA and phthalates has been reported to synergistically disrupt Sertoli–germ cell tight and gap junctions, markedly reducing AR and junctional protein expression and thereby compromising BTB integrity (de Freitas et al., 2016).

7.6 Lifestyle/dietary patterns

In recent years, rapid socio-economic development, combined with unhealthy eating habits and poor lifestyles, has led to a steady increase in global obesity rates (Chooi et al., 2019). Obesity is a major risk factor for non-communicable diseases and is strongly associated with diabetes, fatty liver disease, cardiovascular disease, and cancer (Lauby-Secretan et al., 2016). Obesity has been shown to cause reproductive dysfunction in men, and excess body fat affecting sperm production and quality, making men more susceptible to oligozoospermia and azoospermia (Ma et al., 2019). Previous studies have found that obesity impairs spermatogenesis by disrupting the BTB (Zhang et al., 2014). Recent studies suggest that male obesity cause hormonal imbalances in the HPGA, leading to secondary hypogonadism (Fernandez et al., 2019). Specifically, white adipose tissue produces high levels of cytochrome P450 aromatase, which converts androgens to estrogens, and estrogens then act on the hypothalamus through negative feedback, inhibiting the production and secretion of FSH and LH, thereby impairing testosterone synthesis and spermatogenesis (Barbagallo et al., 2021). The inflammasome NLRP3 is a sensor of cellular damage, once activated, it recruits ASCs to form a caspase-1 activation platform, inducing interleukin secretion and creating an inflammatory microenvironment (Karki and Kanneganti, 2019). Researchers found that decreased AMPKα expression and increased NADPH oxidase activity activated NLRP3 expression in the testes of obese mice, further exacerbating obesity induced SCs dysfunction and male infertility (Mu et al., 2022). Leptin, produced by adipocytes, regulates the body’s energy balance, however, plasma leptin concentrations are high in most obese individuals and are proportional to systemic adiposity. Evidence suggests that leptin promotes the phosphorylation of IRS family members in the hypothalamus, and that phosphorylation of IRS inhibitory sites can impair interactions between FSH and IGF1 in SCs, potentially affecting spermatogenesis (Duan et al., 2004). The impairment of spermatogenesis caused by obesity is regulated by multiple factors, and the specific mechanisms remain to be further investigated.

8 Conclusion and outlook