Abstract

Microplastics (MPs) are increasingly implicated in cancer biology through effects on gene expression, stress responses, and treatment susceptibility; however, causal links remain provisional. We systematically screened PubMed and Google Scholar (through September 2025) to identify cancer-related genes reported to be altered by MP exposure and then evaluated microRNAs (miRNAs) with anticancer activity that may target those genes. Mature miRNA sequences were retrieved from RNAcentral and assessed against MP-altered genes using RNAhybrid for target-site prediction and minimum free-energy (mfe) hybridization. MPs were reported to modulate genes across multiple tumor types—including breast, gastric, liver, lung, colorectal, cervical, pancreatic, and skin. In silico analyses identified candidate miRNAs with favorable mfe values for these targets, including miR-483-3p, miR-365, miR-331-3p, miR-138-5p, miR-760, miR-1-3p, miR-665, miR-490-3p, miR-370-3p, miR-520a, miR-638, miR-559, miR-532-3p, miR-593-5p, and miR-29b. These interactions suggest putative avenues to counter MP-associated oncogenic programs and therapy resistance. Because mfe predictions do not establish functional regulation, all findings should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating. Priorities for validation include reporter assays, gene/protein modulation, phenotypic rescue, and in vivo testing in MP-exposed models. Collectively, our results nominate miRNAs as candidate tools to interrogate and potentially mitigate MP-associated carcinogenic mechanisms.

1 Introduction

Microplastics (MPs) are conventionally defined as plastic particles <5 mm (5,000 µm) in diameter, while nanoplastics (NPs) are generally <1 µm. For the purposes of this review, we focused on the range of 1–5,000 μm, consistent with commonly reported experimental studies (Hale et al., 2020). Among these, human health is one of the most critical concerns. Studies have confirmed the presence of MPs in the human body worldwide, where they can accumulate in various types of cells (Vethaak and Legler, 2021). This accumulation may lead to several adverse health outcomes, including gut microbiota disruption and respiratory disorders (Winiarska et al., 2024).

Microplastics (MPs < 5 mm) have been detected in human tissues and may perturb cancer-related pathways including oxidative stress, lipid metabolism, inflammation, and drug transport. Studies report that MPs can upregulate efflux transporters (ABCB1/ABCG2) and alter chemotherapeutic susceptibility (Rosellini et al., 2023), enhance metastatic features in breast cancer (Park et al., 2023), promote therapy resistance via ASGR2 in gastric cancer (Kim et al., 2022), and aggravate radiation-induced intestinal injury (Chen Y. et al., 2024). Despite these observations, mechanisms remain poorly defined.

One of the most concerning potential health impacts of MPs is cancer. Previous studies have suggested MPs as possible contributors to carcinogenic processes, but the evidence remains preliminary and largely associative (Kumar et al., 2024). In addition to initiating tumorigenesis through mechanisms such as DNA damage (Hu et al., 2022), may also influence the response of cancer cells to anti-cancer therapies, potentially contributing to drug resistance (Kim et al., 2022). These findings underscore the need to explore novel strategies for cancer treatment.

Therefore, scientists have attempted to develop various kinds of anti-cancer therapeutic agents in recent years (Sun et al., 2023). Recent research has focused on developing innovative anticancer strategies, including advanced drug platforms (Kaliyev et al., 2024), stem-cell–based therapies (Kaliyev et al., 2024), and public education initiatives (Barani, 2024). Among these, microRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as promising anti-cancer agents.

miRNAs are ∼22-nucleotide non-coding RNAs that guide Argonaute complexes to complementary mRNA regions, leading to mRNA degradation or translational repression. Each miRNA regulates many targets, allowing broad control of oncogenic networks involving proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, and drug resistance (Szczepanek et al., 2022). These regulatory properties make miRNAs attractive therapeutic candidates for MP-associated cancers. miRNAs possess several advantageous properties, including the ability to regulate cancer-related pathways, modulate drug sensitivity, deliver therapeutic molecules, and enable personalized treatment approaches (Szczepanek et al., 2022), making them strong candidates for treating MP-associated cancers. However, there is still a lack of comprehensive understanding regarding the potential of miRNAs to treat MP- associated tumors and the molecular mechanisms through which they exert anti-cancer effects. Most previous studies have focused on how MPs alter miRNA expression and function (Chen T. et al., 2024).

Therefore, the present study aims to investigate the therapeutic potential of miRNAs in MP-associated cancers through an in silico analysis. Additionally, this review explores possible molecular mechanisms underlying the anti-cancer activity of miRNAs and offers insights for future in-vivo and in-vitro research to further clarify their role in treating MP-associated malignancies.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Literature identification and selection

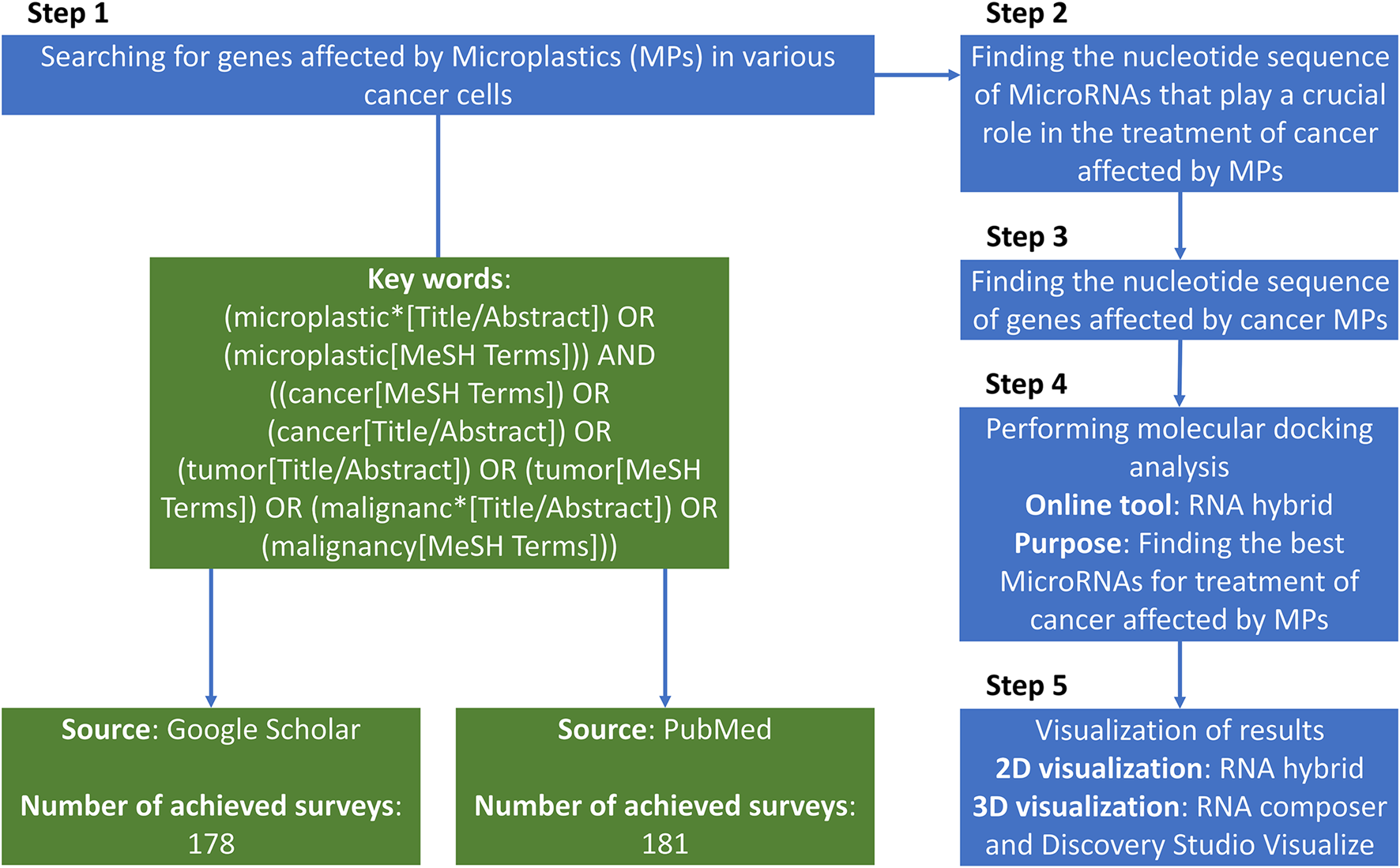

We queried PubMed and Google Scholar from database inception to 30 September 2025 (Figure 1). Example search string (PubMed): (microplastic* OR nanoplastic* OR “plastic-related”) AND (cancer OR tumor OR carcinoma OR leukemia) AND (gene OR transcript* OR “drug resistance” OR efflux OR MAPK OR ABCB1 OR ABCG2) and for miRNAs: (microRNA OR miRNA) AND (anticancer OR tumor suppress* OR apoptosis OR chemosensit*) AND (breast OR gastric OR liver OR lung OR colorectal OR cervical OR pancreatic OR melanoma).

FIGURE 1

The total paradigm of the searching strategy of the present study.

Inclusion criteria: (i) primary in vitro/in vivo/clinical studies in human cancer models or human tissues reporting MP exposure (or plastic-related compounds) and gene/protein/pathway changes; (ii) peer-reviewed; (iii) English. Exclusion: reviews, editorials, non-human non-cancer models, studies reporting expression changes without cancer relevance, or miRNAs lacking anticancer functional evidence. Two reviewers independently screened titles/abstracts and full texts; disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer.

2.2 Sequence sources and target selection

Mature miRNA sequences were retrieved from RNAcentral; human gene sequences (mRNA/UTR/coding region where available) were obtained from NCBI Gene/RefSeq. We evaluated genes previously reported as MP-altered in cancer contexts (Tables 1–3). (Chen T. et al., 2024).

TABLE 1

| Microplastic | Type of cancer cell | Cancer type | Affected gene | Effect of microplastics on gene | The final impact on the cancer cell | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP | CEM/ADR5000 cells | Leukemia | ABCB1 ABCG2 | Inhibition | Increasing cytotoxicity | Rosellini et al. (2023) |

| MDA-MB-231-BCRP cells | Breast cancer | Disruption of detoxification pathways | ||||

| Heightening cell susceptibility to xenobiotics | ||||||

| PMMA | HepG2 | Liver cancer | HO-1 | Upregulation | Increasing oxidative stress | Boran et al. (2024) |

| Promotion of inflammation | ||||||

| PPARγ | Increasing lipid accumulation | |||||

| LXR-α | Disruption of lipid homeostasis | |||||

| Increasing inflammation | ||||||

| FABP1 | Downregulation | Promoting inflammation | ||||

| Promoting lipid accumulation | ||||||

| PPARα | Downregulation | Mitochondrial damage | ||||

| Lipid metabolism disruption | ||||||

| Polythene | SCL-1 | Skin cancer | NLRP3 | Increased expression | Enhancing proliferation | Wang et al. (2023) |

| A431 | Enhancing the inflammatory response | |||||

| PP | MDA-MB-231 | Breast cancer | TMBIM6 | Increased expression | Enhancing cell cycle progression | Park et al. (2023) |

| AP2M1 | Increased expression | Increasing secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 | ||||

| PTP4A2 | Increased expression | Promoting metastatic features | ||||

| FTH1 | Reduced expression | |||||

| PS | NCI-N87 | Gastric cancer | CD44 | Increased expression | Multidrug resistance | Zhao et al. (2024),Brynzak-Schreiber et al. (2024),Li et al. (2023),Yan et al. (2020) |

| ASGR2 | Increased expression | Enhancing cancer hallmarks | ||||

| Enhancing proliferation | ||||||

| Enhancing migration | ||||||

| Drug resistance | ||||||

| Colorectal cancer cells | MUC2 | Reduced expression | Loss of mucosal barrier protection | |||

| Increasing inflammation-driven carcinogenesis | ||||||

| Promotion of colorectal cancer risk | ||||||

| Lung cancer cells | TIM4 | Potential binding and internalization of PS microplastics | Altering the tumor immune microenvironment | |||

| Cervical cancer cells | Immune suppression and modulation | |||||

| Colorectal cancer cells | Tumor progression | |||||

| Gastric cancer cells | ||||||

| Pancreatic cancer cells | ||||||

| AGS | Gastric cancer cells | Bax | Overexpression | Decreasing cell viability | ||

| Inducing apoptosis | ||||||

| Inducing DNA damage | ||||||

| PTFE | A549 | Lung cancer | MAPK Family | Activating | Induction of oxidative stress | K et al. (2023) |

| NLRP3 | Reduced expression | Induction of an inflammatory response | ||||

| BCL2 | Increased expression | Induction of carcinogenic processes |

Genes that are affected by microplastics (MPs) in various types of cancer cells.

A431, human epidermoid carcinoma cell line; ABCB1, ATP-binding cassette sub-family B member 1; ABCG2, ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 2; AGS, adenocarcinoma gastric cancer cells; AP2M1, adaptor-related protein complex 2 subunit mu 1; ASGR2, asialoglycoprotein receptor 2; A549, human lung carcinoma cell line; Bax, Bcl-2-associated X protein; BCL2, B-cell lymphoma 2; CEM/ADR5000 cells, doxorubicin-resistant human acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells; CD44, cluster of differentiation 44; FABP1, fatty acid-binding protein 1; FTH1, ferritin heavy chain 1; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; LXR-α, liver X receptor alpha; MAPK, family, mitogen-activated protein kinase family; MDA-MB-231, human breast adenocarcinoma cell line; MDA-MB-231-BCRP, cells, breast cancer resistance protein-overexpressing MDA-MB-231, cells; MP, microplastic; MUC2, mucin 2; NCI-N87, human gastric carcinoma cell line; NLRP3, NACHT, LRR, and PYD, domains-containing protein 3; PMMA, polymethyl methacrylate; PP, polypropylene; PPARα, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; PS, polystyrene; PTFE, polytetrafluoroethylene; PTP4A2, protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 2; SCL-1, squamous cell carcinoma cell line; TMBIM6, transmembrane BAX, inhibitor motif-containing 6; TIM4, T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 4.

TABLE 2

| Gene | The total function of genes in cancer | Type of cancer | Function of the gene in cancer cells | The molecular mechanism by which genes exert their function in cancer | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCB1 | + Substance transportation + Role in Vascular Transport + Vascular Processes in the Circulatory System + Ion Channel Interactions | + Breast cancer + Leukemia | Preventing the accumulation of toxic substances inside cells | Actively pumps chemotherapeutic drugs out of cancer cells, thereby reducing intracellular drug accumulation | Miao et al. (2017),Altamura et al. (2022) |

| Preventing the accumulation of certain chemotherapeutic drugs | |||||

| Controlling the transport of substances between blood and tissues | Contributes to MDR by lowering the efficacy of various anticancer drugs | ||||

| Reducing drug penetration into certain tissues | Increased efflux of chemotherapeutic drugs, reducing their cytotoxic effects | ||||

| Impacting pharmacokinetics and limiting drug efficacy in cancer therapy | |||||

| Influencing the selective permeability of blood vessels | Barrier Integrity and Selectivity: By regulating the efflux of molecules, P-gp contributes to maintaining the selective permeability of vascular barriers | ||||

| Affecting drug distribution and clearance | Drug Resistance in Circulatory Tumors: P-gp impacts drug efficacy by limiting the systemic retention of drugs within the vascular environment | ||||

| Regulating apoptosis | P-gp may regulate or interact with ion channels, contributing to cellular responses and influencing apoptosis and drug resistance | ||||

| Regulating proliferation | Facilitating cellular adaptation to stress conditions, such as chemotherapy exposure | ||||

| ABCG2 | + Response to the drug + Substance transportation | + Breast Cancer + Leukemia | Increasing drug efflux | Reducing intracellular retention of chemotherapeutic agents | Wang et al. (2020),Franczyk et al. (2022) |

| Transporting a wide range of chemotherapeutic agents and limiting their cytotoxic effects in cancer cells | |||||

| Acting as a barrier in tissues like the blood-brain barrier, liver, and intestines | Regulating the bioavailability and toxicity of drugs | ||||

| AP2M1 | Vesicle coat | Breast Cancer | Promoting intracellular trafficking | Coating vesicles during endocytosis | Shin et al., 2021; Münz (2020),Xue et al. (2021) |

| Promoting cancer progression | Facilitating the recruitment of cargo proteins to clathrin-coated vesicles | ||||

| Maintaining cellular homeostasis | |||||

| Regulating the availability of key signaling molecules | |||||

| Promoting tumor growth and progression | Influencing the internalization and trafficking of cancer-related receptors such as EGFR | ||||

| Antigen Processing | Playing a role in endocytosis | Modulating cancer cell signaling | |||

| Modulating cancer cell nutrient uptake | |||||

| Modulating cancer cell receptor recycling or degradation | |||||

| Curbing oncogenic pathways | |||||

| Internalization of MHC class I molecules | Regulating the trafficking and recycling of MHC molecules | ||||

| Ensuring proper antigen display to T cells | |||||

| receptor-mediated endocytosis | Promoting cancer progression | Increasing receptor endocytosis | |||

| Modulating cancer cell proliferation and survival pathways | Regulating CME | ||||

| Mediating the trafficking of receptors such as EGFR | |||||

| ASGR2 | Regulation of immune response | Gastric Cancer | Influencing the tumor microenvironment | + Targeting glycoproteins with terminal galactose or N-acetylgalactosamine residues for degradation + Glycoprotein recycling + Immune regulation | Xue et al. (2021) |

| Promoting tumor metastasis | |||||

| Worsening of tumor prognosis | |||||

| Increasing tumor aggressiveness | |||||

| Increasing tumor survival | |||||

| Bax | Gastric cancer | Inducing apoptosis in cancer cells | Collapsing the mitochondrial membrane potential, which results in the release of cytochrome C, which leads to apoptosis | Shabani et al. (2020),Shen et al. (2023) | |

| Activation caspases 3, 7, and 9 | |||||

| BCL2 | Regulation of the extrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway | Lung cancer | Preventing cancer cell death | + Inhibiting the pro-apoptotic protein Bax + Inhibiting the activation of caspases 3, 7, and 9 + Inhibiting the activation of the cleavage of PARP | Ramkumar et al. (2023),Alam et al. (2022a),Alam et al. (2022b) |

| Promoting cancer cell survival | |||||

| Promoting resistance to chemotherapy and radiation | |||||

| Preventing the induction of apoptosis | |||||

| Avoiding programmed cell death | |||||

| Blocking the activation of downstream caspases | Preventing the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria | ||||

| Promoting cancer growth | |||||

| Promoting the persistence of cancer cells | |||||

| CD44 | Cell-matrix adhesion | Gastric cancer | Enhancing antioxidant defense | Stabilizing the xCT cystine transporter | Jang et al., 2011; Zavros (2017) |

| Reducing oxidative stress | |||||

| Enhancing the antioxidant defense of cancer stem cells | |||||

| Tumor cell survival | |||||

| Promoting tumor growth | |||||

| Tumor initiation | Interaction with extracellular matrix components such as hyaluronan | ||||

| Tumor progression | Involvement in signaling pathways like c-Met activation | ||||

| FABP1 | Lipid oxidation | Liver cancer | Enhancing tumor progression | Interacting with PPARG in TAMs to promote FAO | Tang et al. (2023) |

| Maintaining the M2 phenotype of TAMs | |||||

| Immune suppression | |||||

| FTH1 | Iron ion homeostasis | Breast Cancer | Iron storage | Activating, binding, and stabilizing the tumor suppressor p53 under oxidative stress | Di Sanzo et al. (2020),Jia et al. (2024) |

| Oxidative damage protection | |||||

| Regulation of angiogenesis | |||||

| Inhibiting ferroptosis | Chelating ferrous iron and reducing ROS accumulation | ||||

| Inhibiting chemotherapy resistance | |||||

| Stabilizing high levels of antioxidant capacity in breast cancer cells | |||||

| HO-1 | Heme metabolic process | Liver cancer | Reducing oxidative stress | Playing a role in the Nrf2 signaling pathway | Alharbi et al. (2022) |

| Creating Cytoprotective Effects | Facilitating the production of biliverdin, CO, and free iron from heme | ||||

| Modulating tumor cell proliferation | Anti-apoptotic and antioxidant properties | ||||

| Enhancing cancer cell resistance to treatment | Activation of survival pathways | ||||

| Enhancing tumor progression | Suppression of apoptosis | ||||

| Enhancing metastasis | |||||

| LXR-α | Fatty acid biosynthetic process | Liver cancer | Lipid accumulation | Modulating downstream target genes, such as SREBP-1c, PPARγ, and FAS | Han et al. (2023) |

| Inflammation | Inhibiting Cancer Progression | ||||

| Immune responses | Inhibiting tumor cell proliferation | Upregulation of genes like SOCS3 and suppression of oncogenes like FOXM1 | |||

| Inducing cell cycle arrest | |||||

| Inducing apoptosis | |||||

| Reducing tumor invasiveness | Interacting with the Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signaling pathways | ||||

| Reducing tumor migration | |||||

| MAPK Family | Lung cancer | Increasing cancer cell proliferation | Activation of Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK cascade | Jain et al. (2021),Zhou et al. (2020a) | |

| Increasing cancer cell metastasis | |||||

| Promoting cancer cell resistance to targeted therapies | |||||

| Promoting cancer cell proliferation | Activation of receptor α4β1 integrin leads to phosphorylation of MAPK components such as JNK and p38 | ||||

| Promoting cancer cell migration | |||||

| Promoting cancer cell invasion | |||||

| MUC2 | Glycoprotein biosynthetic process | Colorectal cancer cells | Regulating immune response and inflammation | + Decreasing IL-6 secretion + Inhibiting the STAT3 and Chk2 signaling pathway + Activation of CREB phosphorylation + Upregulation of E-cadherin | Hsu et al. (2017) |

| Decreasing tumor cell migration | |||||

| Decreasing EMT | |||||

| Decreasing metastasis | |||||

| Decreasing cancer progression | |||||

| NLRP3 | Regulation of the inflammatory response | + Skin Cancer + Lung cancer | Inducing inflammation | Activation of NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1 which leads to Activating IL-1β and IL-18 | Ciazyn et al. (2020) |

| Regulation of cytokine production is involved in the inflammatory response | Increasing tumor growth | ||||

| Increasing tumor angiogenesis | |||||

| Increasing tumor immune evasion mechanisms | |||||

| Inducing DNA damage | |||||

| Suppressing apoptosis | |||||

| Creating a tumor-promoting environment | |||||

| PPARα | Regulation of the inflammatory response | Liver cancer | + Increasing tumor cell proliferation + Decreasing tumor cell apoptosis + Increasing tumor cell invasiveness | Regulating lipid metabolism | Pan et al. (2024) |

| Regulation of cytokine production is involved in the inflammatory response | Regulating glucose metabolism | ||||

| Regulating oxidative stress | |||||

| Regulating inflammation | |||||

| Interacting with several signaling pathways like NF-κB | |||||

| PPARγ | Transcription coactivator activity | Liver cancer | Inducing the transcription of genes involved in anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, and anti-oxidative responses | Binding with the RXR to specific DNA sequences called PPREs | Pan et al. (2024),Ishtiaq et al. (2022) |

| Ligand-activated transcription factor activity | Anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects | + Inhibiting the expression of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1 through inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway + Promoting the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10, TGF-β + Inducing the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and catalase + reduces ROS levels + Limiting DNA damage and oxidative stress | |||

| Regulation of the inflammatory response | Inhibiting hepatic fibrosis progression and inflammation | ||||

| Regulation of cytokine production is involved in the inflammatory response | Suppressing tumor microenvironment remodeling | ||||

| Decreasing cancer cell apoptosis | |||||

| Suppressing ECM deposition in liver fibrosis | Suppressing the activation of HSCs | ||||

| Enhancing glucose consumption | |||||

| Enhancing lactate generation | |||||

| Enhancing cancer cell proliferation | |||||

| PTP4A2 | Breast Cancer | Promoting angiogenesis | Regulation of VEGF-A and DLL-4/Notch-1 signaling pathways | Yu et al. (2023) | |

| Enhancing tumor cell migration | Regulation ERK signaling pathway | ||||

| Enhancing tumor cell invasion | |||||

| Supporting oncogenesis | Interaction with CNNM3 | ||||

| Enhancing tumor progression and metastasis | Regulating intracellular magnesium concentration | ||||

| TIM4 | Antigen processing and presentation | Lung cancer cells | Tumor progression | Binding to PtdSer on apoptotic cells, mediating their uptake by DCs | Liu et al. (2020),Wang et al. (2021),Astuti et al. (2024),Caronni et al. (2021) |

| Leukocyte migration | Lung cancer cells | Tumor cell proliferation | Interacting with αvβ3 integrin via its Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) motif | ||

| Colorectal cancer cells | Enhancing the EMT | ||||

| Gastric cancer cells | Enhancing the migration of cancer cells | ||||

| Enhancing the invasion of cancer cells | |||||

| Recruitment of tumor-associated macrophages | Activating PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway | ||||

| Activation of angiogenesis | |||||

| Pancreatic cancer cells | Suppressing the immune system | Arg1 upregulation, which suppresses CD8+ T cell activity | |||

| Facilitating tumor immune evasion | |||||

| TMBIM6 | Regulation of response to endoplasmic reticulum stress | Breast Cancer | Increasing chemo resistance | Elevating the levels of cytosolic ROS and calcium | Robinson et al. (2025),Junjappa et al. (2019),Shin et al. (2023) |

| Apoptotic mitochondrial changes | Increasing cancer metastasis | Inducing paraptosis via ERAD II mechanisms | |||

| Increasing cancer progression | Activating lysosomal biogenesis | ||||

| Enhancing migration and invasion | Activating the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway | ||||

| Increasing the expression of mesenchymal markers, MMP-9, and Snail-1 and Snail-2 | |||||

| Cancer progression | PKC activation enhances Sp1-mediated TMBIM6 transcription | ||||

| Supporting cellular processes like metastasis | |||||

| Facilitating resistance to apoptosis |

Detailed information about gene function and molecular mechanisms that are affected by MPs, based on previous studies.

Arg1, Arginase-1; CME, clathrin-mediated endocytosis; CO, carbon monoxide; DCs, dendritic cells; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; ERK, Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinase; FAO, fatty acid oxidation; HSC, hepatic stellate cell; MDR, multidrug resistance; MEK, MAPK/ERK, kinase; MMPs, metalloproteinases; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase-9; PARP, poly-ADP, ribose polymerase; P-gp, P-glycoprotein; PKC, Protein kinase-C; PPARG, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; PtdSer, phosphatidylserine; Raf, Rapidly Accelerated Fibrosarcoma; Ras, Rat Sarcoma virus; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TAMs, tumor-associated macrophages.

TABLE 3

| Type of MP | Type of MP-affected cancer | Affected anti-cancer agent | Effect of MP on anti-cancer agents | Effect of MP on cancer | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic-related compounds | Breast cancer cells | Doxorubicin | Altering the uptake and intracellular accumulation of doxorubicin | Increasing the cytotoxicity in cancer cells | Rosellini et al. (2023) |

| Leukemia cells | Enhancing the intracellular concentration of doxorubicin | Affecting the therapeutic outcome | |||

| PS | Abdominal and pelvic tumors | Radiotherapy | Aggravating radiation-induced intestinal injury | Enhancing the side effects of the anti-cancer approaches | Chen et al. (2024a),Yan et al. (2020),Zhou et al. (2020b) |

| Decreasing the efficacy of radiotherapy | |||||

| Gastric cancer | Bortezomib | + Inducing drug resistance + Influencing the bioavailability and toxicity of Tetracycline | Enhancing cancer progression | ||

| Paclitaxel | Enhancing cancer proliferation | ||||

| Gefitinib | Enhancing cancer migration | ||||

| Lapatinib | Enhancing cancer invasion | ||||

| Trastuzumab | Poor survival rates | ||||

| Tetracycline | Enhancing the cytotoxicity of cancer cells | ||||

| Reducing cancer cell viability | |||||

| Increasing oxidative stress in cancer cells | |||||

| Increasing cancer cell apoptosis |

Various effects of MPs on the anti-cancer agents and the final effect caused by these impacts on cancer cells.

2.3 In silico hybridization

We used RNAhybrid to predict target-site hybridization and minimum free energy (mfe). Default parameters were applied unless noted; where possible we scanned 3′UTRs preferentially and considered coding sequence if 3′UTR data were unavailable. For each gene, we screened multiple miRNAs with anticancer evidence and recorded the lowest mfe site per miRNA-gene pair. Lower (more negative) mfe was interpreted as more stable predicted binding. No single mfe threshold was used for exclusion; instead, candidates were prioritized by relative mfe within gene-specific comparisons (Chen T. et al., 2024; Jain et al., 2021). MFE criteria included: RNAhybrid minimum-free-energy (mfe) values were interpreted as strong (≤−20 kcal mol−1), suggestive (−15 to −19.9), and borderline (>−15). Pairs above −20 were retained only if supported by prior functional evidence and are flagged as low-priority hypothese.

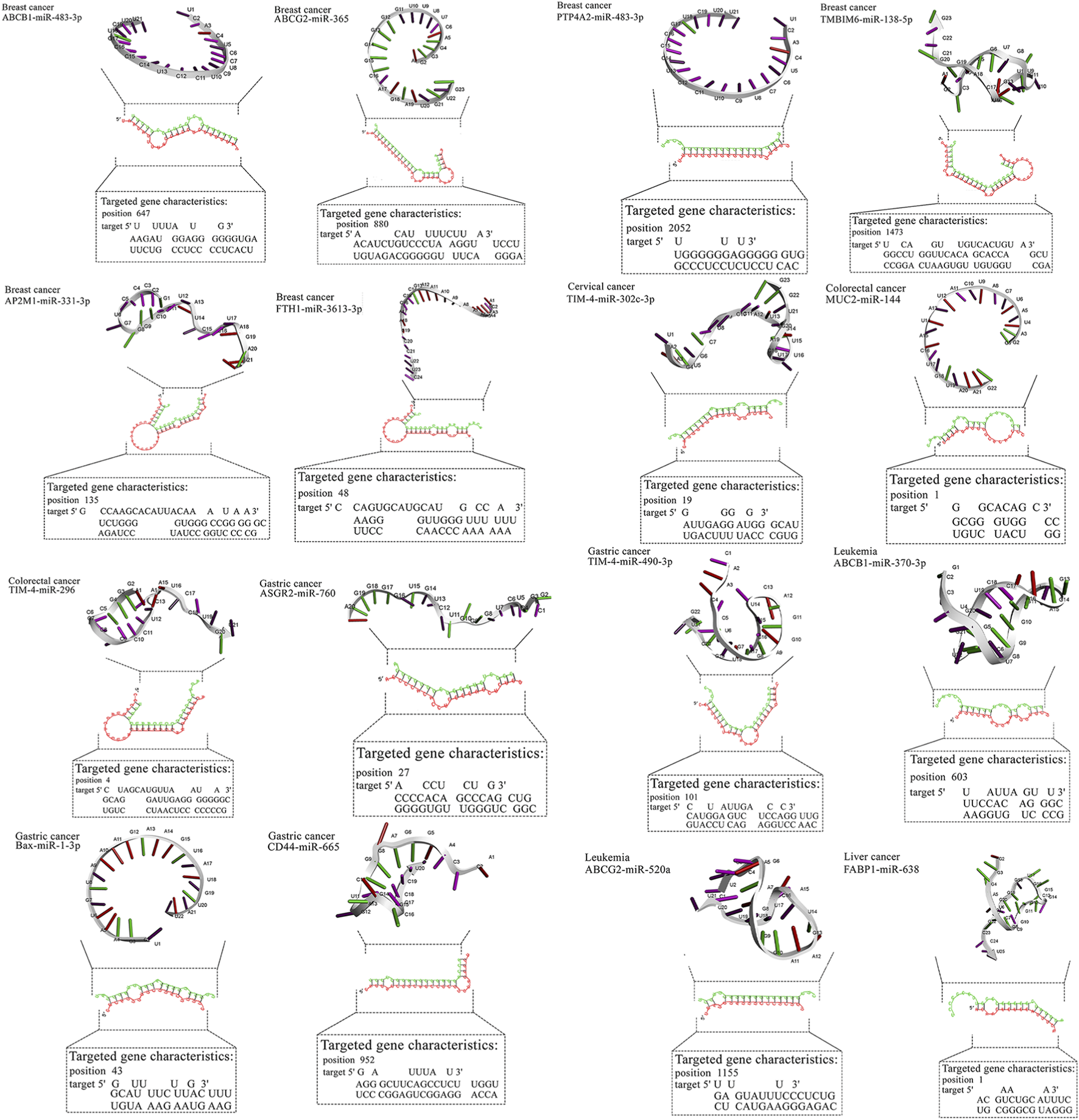

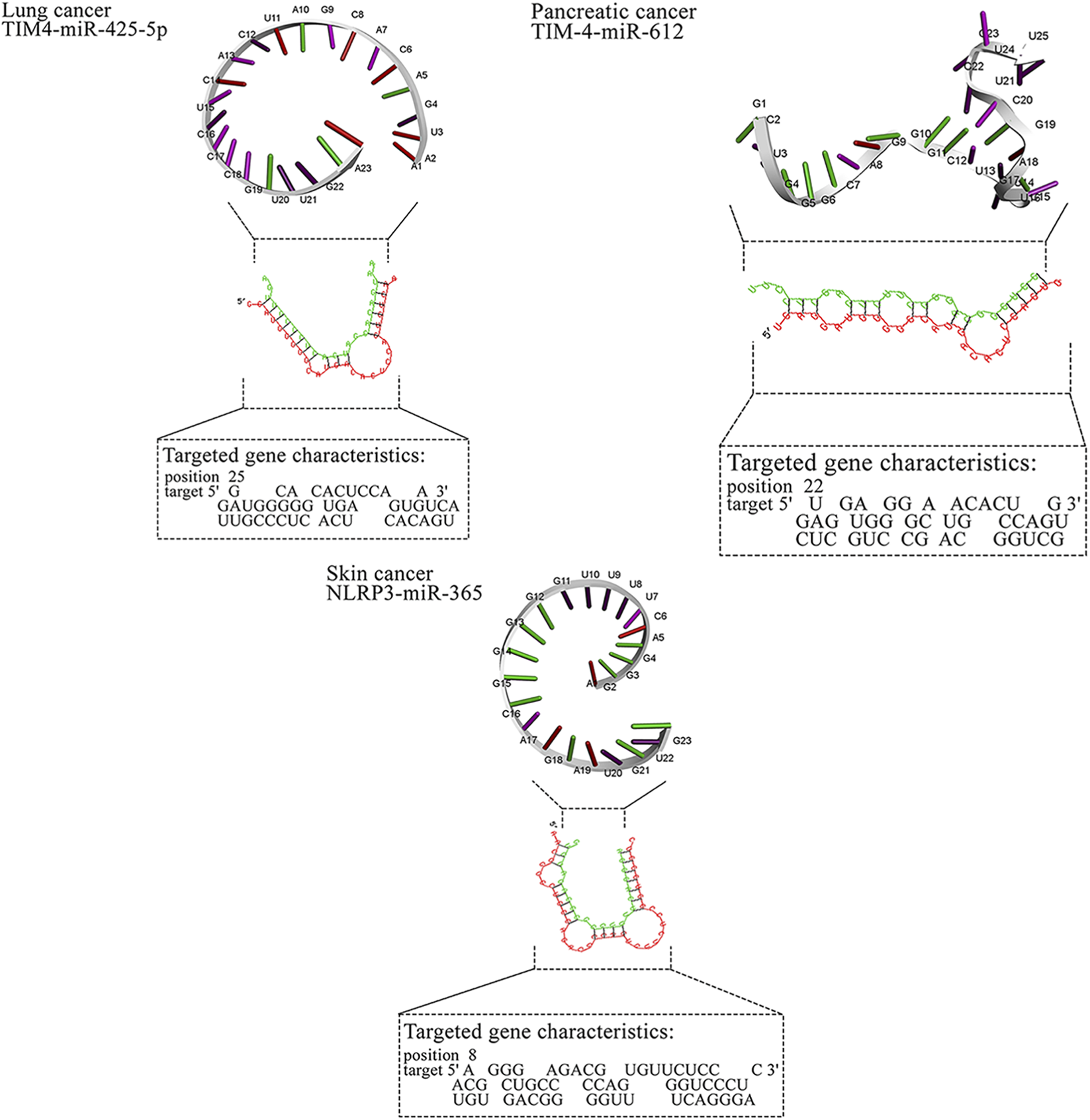

2.4 Visualization and networks

Two-dimensional pairing diagrams were exported from RNAhybrid. 3D miRNA cartoons were rendered in Discovery Studio Visualizer for illustrative purposes only. Cytoscape was used to depict miRNA–gene–pathway relationships (Figure 2). Representative 2D pairing plots, 3D illustrations, and network diagrams are shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 2

Detailed data about molecular interactions between microRNAs with anti-cancer activity and genes affected by MPs. The 3D structure at the top of the figure represents microRNA with the highest binding affinity toward the gene affected by MPs. The data about the targeted gene is depicted in the lower part of the figure. ABCB1, ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily B Member 1; ABCG2, ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily G Member 2; AP2M1, Adaptor Related Protein Complex 2 Subunit Mu 1; ASGR2, Asialoglycoprotein Receptor 2; Bax, BCL2 Associated X, Apoptosis Regulator; BCL2, B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2; BRAF, B-Raf Proto-Oncogene, Serine/Threonine Kinase; c-jun, Jun Proto-Oncogene, AP-1 Transcription Factor Subunit; CD44, CD44 Molecule (Indian Blood Group); ERK, Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase; FABP1, Fatty Acid Binding Protein 1; FTH1, Ferritin Heavy Chain 1; HO-1, Heme Oxygenase 1; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal Kinase; KRAS, KRAS Proto-Oncogene, GTPase; LXR-α, Liver X Receptor Alpha; MAP2K1, Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 1; MAP2K4, Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 4; MAPK14, Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase 14; MUC2, Mucin 2; NLRP3, NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3; NLRP3, NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3; PPARα, Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha; PPARγ, Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma; PTP4A2, Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Type IVA, Member 2; TMBIM6, Transmembrane BAX Inhibitor Motif Containing 6; TIM4, T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain Containing-4; TIM4, T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain Containing-4; TIM4, T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain Containing-4; TIM4, T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain Containing-4; TIM4, T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain Containing-4.

FIGURE 3

MicroRNAs with the in-silico capability to suppress genes in MPs-based cancers and their possible targeted molecular pathways. The blue, red, green, and gray arrows represent activation (or upregulation), inhibition (or downregulation), regulation, and interaction, respectively. Moreover, yellow hexagons, blue ovals, and green ovals demonstrate microRNAs, targeted genes, and pathways affected by targeted genes, respectively. ABCB1, ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily B Member 1; ABCG2, ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily G Member 2; AP2M1, Adaptor Related Protein Complex 2 Subunit Mu 1; ASGR2, Asialoglycoprotein Receptor 2; Bax, BCL2 Associated X, Apoptosis Regulator; BCL2, B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2; BRAF, B-Raf Proto-Oncogene, Serine/Threonine Kinase; c-jun, Jun Proto-Oncogene, AP-1 Transcription Factor Subunit; CD44, CD44 Molecule (Indian Blood Group); ERK, Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase; FABP1, Fatty Acid Binding Protein 1; FTH1, Ferritin Heavy Chain 1; HO-1, Heme Oxygenase 1; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal Kinase; KRAS, KRAS Proto-Oncogene, GTPase; LXR-α, Liver X Receptor Alpha; MAP2K1, Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 1; MAP2K4, Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 4; MAPK14, Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase 14; MUC2, Mucin 2; NLRP3, NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3; NLRP3, NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3; PPARα, Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha; PPARγ, Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma; PTP4A2, Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Type IVA, Member 2; TMBIM6, Transmembrane BAX Inhibitor Motif Containing 6; TIM4, T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain Containing-4; TIM4, T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain Containing-4; TIM4, T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain Containing-4; TIM4, T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain Containing-4; TIM4, T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain Containing-4.

2.5 Interpretive caveats

mfe predictions do not prove targeting; they require orthogonal validation (reporter assays with wild-type/mutant sites, miRNA gain/loss, protein readouts, and phenotypic rescue under MP exposure).

3 Results

3.1 MPs modulate cancer-relevant genes across tumor types

Across studies, MPs were linked to changes in efflux transporters (ABCB1, ABCG2), stress and survival mediators (TMBIM6, HO-1), immune modulators (TIM4), metabolic regulators (PPARα/γ, LXR-α, FABP1), and ECM/adhesion factors (CD44). In breast cancer models, polypropylene increased AP2M1, PTP4A2, and TMBIM6 while reducing FTH1, a pattern consistent with enhanced trafficking/ER-stress signaling and diminished iron-mediated tumor suppressive functions. In gastric cancer, polystyrene exposure associated with higher CD44 and ASGR2, aligning with stemness/adhesion and glycoprotein handling. In liver cancer, PMMA upregulated HO-1 and downregulated PPARα/FABP1, suggesting oxidative stress and lipid dysregulation. Lung cancer models exposed to PTFE implicated MAPK cascade genes and BCL2, consistent with proliferation and apoptosis evasion. Collectively, these reports converge on MP-associated activation of survival and resistance programs with tumor- and polymer-specific nuances. An overview of MP-altered genes by tumor type is summarized in Figure 3 (Table 1).

3.2 Functional roles of MP-altered genes

Table 2 maps each gene to cancer functions and mechanisms. Notable axes include: (i) drug efflux (ABCB1/ABCG2) → reduced intracellular drug levels; (ii) endocytosis/trafficking (AP2M1) → receptor signaling and nutrient uptake; (iii) immune modulation (TIM4) → efferocytosis and immune tolerance; (iv) metabolism/oxidative balance (PPARs, LXR-α, FABP1, HO-1) → growth and stress adaptation; (v) MAPK signaling → proliferation/migration; and (vi) cell death control (BAX↑, BCL2↑) → apoptosis set-point shifts. These roles provide mechanistic context for potential miRNA interventions (Table 2).

3.3 Impact of MPs on anticancer therapies

Reports indicate both sensitization and resistance, but the weight of evidence suggests attenuation of therapy efficacy in several contexts (e.g., altered uptake/efflux; MAPK-mediated survival; inflammation-mediated radioprotection). The table summarizes polymer/tumor-specific patterns and implicated agents (e.g., doxorubicin, taxanes, HER2/EGFR inhibitors), emphasizing the need to measure MP exposure in preclinical efficacy studies (Table 3).

3.4 miRNAs as therapeutic candidates

We collated anticancer miRNAs with functional evidence (apoptosis, invasion, chemosensitization). This pool served as input to the in silico screen. Where multiple candidates mapped to one target, prioritization was by relative mfe plus prior functional plausibility. Examples of anticancer miRNAs selected for screening are illustrated in Figure 3 (Supplementary Table S1).

3.5 Predicted miRNA–gene interactions

For breast cancer, miR-483-3p and miR-138-5p showed favorable predictions against ABCB1/PTP4A2 and TMBIM6, respectively, while miR-365 and miR-331-3p mapped to ABCG2/AP2M1. In gastric cancer, miR-665 and miR-760 targeted CD44 and ASGR2; in liver cancer, miR-638 showed broad predictions (e.g., HO-1, PPARα/γ). Lung cancer candidates clustered on MAPK nodes (miR-532-3p, miR-593-5p, miR-29b). These pairings nominate tractable validation sets (reporter assays ± MP exposure, phenotypic readouts). Representative RNAhybrid pairing diagrams and 3D cartoons for top-ranked pairs appear in Figure 3, and the integrated miRNA–gene–pathway network is provided in Figure 3 (Table 4).

TABLE 4

| Type of cancer affected by MPs | The kind of gene affected by MPs in this cancer | MicroRNA with therapeutic in silico effect on the gene affected by MPs | Sequence of microRNA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The most proper therapeutic microRNA based on in silico data | Binding affinity | |||

| Breast cancer | ABCB1 | miR-483-3p | −28.2 | UCACUCCUCUCCUCCCGUCUU |

| ABCG2 | miR-365 | −31.8 | AGGGACUUUUGGGGGCAGAUGUG | |

| AP2M1 | miR-331-3p | −28.7 | GCCCCUGGGCCUAUCCUAGAA | |

| FTH1 | miR-3613-3p | −16.7 | ACAAAAAAAAAAGCCCAACCCUUC | |

| PTP4A2 | miR-483-3p | −31.9 | UCACUCCUCUCCUCCCGUCUU | |

| TMBIM6 | miR-138-5p | −34.4 | AGCUGGUGUUGUGAAUCAGGCCG | |

| Cervical cancer | TIM4 | miR-302c-3p | −25.1 | UAAGUGCUUCCAUGUUUCAGUGG |

| Colorectal cancer | MUC2 | miR-144 | −13.8 | GGAUAUCAUCAUAUACUGUAAG |

| TIM4 | miR-296 | −31.9 | AGGGCCCCCCCUCAAUCCUGU | |

| Gastric cancer | ASGR2 | miR-760 | −32 | CGGCUCUGGGUCUGUGGGGA |

| Bax | miR-1-3p | −14.1 | UGGAAUGUAAAGAAGUAUGUAU | |

| CD44 | miR-665 | −35.5 | ACCAGGAGGCUGAGGCCCCU | |

| TIM4 | miR-490-3p | −27.9 | CAACCUGGAGGACUCCAUGCUG | |

| Leukemia | ABCB1 | miR-370-3p | −24.7 | GCCUGCUGGGGUGGAACCUGGU |

| ABCG2 | miR-520a | −26.6 | CUCCAGAGGGAAGUACUUUCU | |

| Liver cancer | FABP1 | miR-638 | −20 | AGGGAUCGCGGGCGGGUGGCGGCCU |

| HO-1 | miR-638 | −37.4 | AGGGAUCGCGGGCGGGUGGCGGCCU | |

| miR-4270-5p | −37.4 | UCAGGGAGUCAGGGGAGGGC | ||

| LXR-α | miR-559 | −15.7 | UAAAGUAAAUAUGCACCAAAA | |

| PPARα | miR-638 | −39.3 | AGGGAUCGCGGGCGGGUGGCGGCCU | |

| PPARγ | miR-638 | −29.2 | AGGGAUCGCGGGCGGGUGGCGGCCU | |

| Lung cancer | BRAF | miR-532-3p | −31 | CCUCCCACACCCAAGGCUUGCA |

| miR-593-5p | −31 | AGGCACCAGCCAGGCAUUGCUCAGC | ||

| c-jun | miR-92b | −33.8 | AGGGACGGGACGCGGUGCAGUG | |

| ERK | miR-593-5p | −34.9 | AGGCACCAGCCAGGCAUUGCUCAGC | |

| JNK | miR-532-3p | −34.9 | CCUCCCACACCCAAGGCUUGCA | |

| MAP2K1 | miR-593-5p | −33.9 | AGGCACCAGCCAGGCAUUGCUCAGC | |

| MAP2K4 | miR-611 | −36.2 | GCGAGGACCCCUCGGGGUCUGAC | |

| MAPK14 | miR-377 | −30.7 | AGAGGUUGCCCUUGGUGAAUUC | |

| KRAS | miR-29b | −30.8 | GCUGGUUUCAUAUGGUGGUUUAGA | |

| NLRP3 | miR-92b | −33.1 | AGGGACGGGACGCGGUGCAGUG | |

| BCL2 | miR-593-5p | −37.7 | AGGCACCAGCCAGGCAUUGCUCAGC | |

| TIM4 | miR-425-5p | −25.7 | AAUGACACGAUCACUCCCGUUGA | |

| Skin cancer | NLRP3 | miR-365 | −28.9 | AGGGACUUUUGGGGGCAGAUGUG |

| Pancreatic cancer | TIM4 | miR-612 | −25.4 | GCUGGGCAGGGCUUCUGAGCUCCUU |

Detailed information about the binding affinity of microRNAs and genes in cancer affected by MPs.

Lower (more negative) mfe = stronger binding. Strong (≤−20), Suggestive (−15 to −19.9), Borderline (>−15). Borderline values are shown for completeness but require experimental validation.

Most high-affinity interactions showed mfe ≤ −20 kcal mol−1 (e.g., TMBIM6/miR-138-5p, CD44/miR-665, PPARα/miR-638, MAP2K4/miR-611). Moderate (−15 to −19.9) values such as FTH1/miR-3613-3p were retained due to prior experimental evidence of anticancer function. Borderline pairs (e.g., BAX/miR-1-3p, −14.1) were listed for transparency but are considered exploratory. Representative hybridization structures are illustrated in Figure 3.

4 Discussion

Our results are consistent with prior evidence that MP exposure modulates canonical cancer pathways. Enhanced efflux and drug resistance observed experimentally (Rosellini et al., 2023) parallel our identification of ABCB1/ABCG2 as MP-responsive genes and their suppression by miR-483-3p and miR-365. Polypropylene-induced metastasis (Park et al., 2023) corresponds to increased AP2M1/PTP4A2/TMBIM6, predicted to be inhibited by miR-331-3p and miR-138-5p. Upregulation of ASGR2 in gastric cancer (Kim et al., 2022) matches our predicted targeting by miR-760. Similarly, activation of MAPK and BCL2 signaling (Jain et al., 2021; Ramkumar et al., 2023; Zhou Z. et al., 2020) is reflected in our miR-532-3p/miR-593-5p predictions. These consistencies strengthen the biological plausibility of our computational findings while emphasizing the need for experimental validation.

Besides, MPs affect some genes in cancer cells and suppress their effects. For instance, Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) inhibits liver cancer cells by downregulating FABP1 and PPAR alpha. According to prior surveys, MPs can downregulate specific genes in tumor cells, such as BCAS3, PHF19, and PRKCD, whose expression has been suppressed by microplastics in previous studies (Chen et al., 2025).

Moreover, our study demonstrates that MPs can affect some genes in breast cancer. ABCB1 is one of these genes that encodes P-glycoprotein (P-gp), an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) efflux transporter involved in multidrug resistance (MDR) in breast cancer, which expels chemotherapeutic drugs from cells, reduces drug efficacy, and contributes to treatment failure (Miao et al., 2017). It regulates ion channels, affecting apoptosis, proliferation, and other cancer-related processes (Altamura et al., 2022).

ABCG2 is another gene affected by MPs, and it encodes Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP), another ABC transporter involved in MDR by exporting chemotherapeutic agents, such as mitoxantrone and doxorubicin, out of cancer cells, reducing drug efficacy (Zhang et al., 2022). It also influences drug bioavailability and toxicity, acting as a barrier in the blood-brain barrier, liver, and intestines, with alterations linked to treatment failure in cancers with high ABCG2 expression (Wang et al., 2020; Franczyk et al., 2022).

AP2M1, a key component of the clathrin adaptor protein complex, facilitates receptor-mediated endocytosis in cancer cells, enhancing nutrient and growth factor uptake, which supports tumor growth and survival (Shin et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Münz, 2020). Its overexpression is associated with aggressive cancer phenotypes and chemoresistance (Liu et al., 2023). Notably, this gene is also influenced by MPs in breast cancer.

Other genes affected by MPs in breast cancer include FTH1, PTP4A2, and TMBIM6. FTH1, a tumor suppressor, regulates iron storage and oxidative stress protection in cancer cells and stabilizes p53 under stress conditions. Silencing FTH1 leads to increased tumor growth, migration, and chemoresistance, along with upregulation of oncogenes like c-MYC and G9a (Di Sanzo et al., 2020; Ali et al., 2021). PTP4A2, upregulated in breast cancer, promotes cancer progression through various pathways (Chouleur et al., 2024). TMBIM6, a key regulator of stress responses, is linked to increased chemoresistance, cancer progression, and metastasis in breast cancer, as well as reduced patient survivalTMBIM6, a key regulator of stress responses, is linked to increased chemoresistance, cancer progression, and metastasis in breast cancer, as well as reduced patient survival (Robinson et al., 2025).

The other effect on MPs on genes in cancer cells is their effect on cervical cancer cells. Based on prior surveys, TIM4, along with TIM3, plays an essential role in the degradation of dying tumor cells via autophagy, reducing antigen presentation and impairing cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses, creating immune tolerance, and weakening the antitumor immune response (Junjappa et al., 2019).

Furthermore, the present study demonstrates that two genes in colorectal cancer (CRC) cells are affected by MPs: MUC2 and TIM4. MUC2 is a protective barrier in epithelial cells, playing a role in cell differentiation and maintaining the balance of adhesion. Altered MUC2 expression impacts the progression of CRC by influencing cellular proliferation, apoptosis, and epithelial integrity (Iranmanesh et al., 2021). Notably, the silencing of MUC2 increases IL-6 secretion, which activates the STAT3 signaling pathway, promoting tumor cell migration, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and metastasis. MUC2 downregulation leads to the activation of STAT3 and Chk2, suppression of CREB phosphorylation, and loss of E-cadherin, facilitating cancer progression and metastasis (Hsu et al., 2017). Moreover, TIM4 acts as an oncogene through different mechanisms, including supporting tumor cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and immune evasion, and contributing to tumor immune tolerance by impairing antigen presentation and cytotoxic T cell responses (Liu et al., 2020).

According to our findings, ASGR2, Bax, CD44, and TIM4 are genes impacted by MPs in gastric cancer cells. ASGR2 enhances tumor survival and metastasis, with higher levels linked to poor prognosis in gastric cancer (Xue et al., 2021). CD44 regulates cell adhesion, motility, and survival, promoting gastric cancer progression through tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis (Jang et al., 2011). It also supports tumor survival by enhancing antioxidant defenses and reducing oxidative stress (Zavros, 2017). TIM4 is overexpressed in gastric cancer tissues, correlating with increased angiogenesis, tumor growth, and poorer patient survival outcomes (Wang et al., 2021). In contrast, Bax induces apoptosis in gastric cancer cells through the mitochondrial pathway, promoting pro-apoptotic signaling, mitochondrial membrane collapse, and subsequent caspase activation (Shabani et al., 2020; Shen et al., 2023).

The other genes affected by MPs in cancer cells are ABCB1 and ABCG2 in Leukemia. ABCB1 is an efflux transporter that helps pump chemotherapy drugs out of cells, and its activation contributes to MDR. In AML, overexpression of ABCB1 has been linked to poor treatment outcomes ABCB1 (Sucha et al., 2022). ABCG2 functions as an efflux transporter that can extrude a wide variety of chemotherapy drugs out of the cells, thereby reducing their effectiveness and contributing to drug resistance in leukemia cells. Moreover, the overexpression of ABCG2 in leukemia cells is associated with poor clinical outcomes, including reduced complete remission rates and overall survival (Damiani and Tiribelli, 2023).

In addition, FABP1, HO-1, LXR-α, PPAR-alpha (PPARα), and PPARγ have been affected by MPs in liver cancer cells. FABP1 supports tumor progression by maintaining the M2 phenotype of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which is associated with immune suppression and cancer progression. FABP1 deficiency in TAMs reduced tumor growth, invasion, and migration in vitro, highlighting its role in enhancing cancer cell proliferation and aggressiveness (Tang et al., 2023). HO-1 promotes cancer cell survival by suppressing pro-apoptotic pathways, regulating mitochondrial oxidative stress, activating the transcription of antioxidant and detoxifying genes, and enhancing the cell’s ability to counteract oxidative damage and resist apoptosis (Alharbi et al., 2022). LXR-α plays a crucial role in regulating lipid metabolism, inflammation, and immune responses in HCC. Its activation inhibits tumor cell proliferation by inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, and reduces tumor invasiveness and migration (Han et al., 2023).

PPARα plays a significant role in the development and progression of liver cancer by controlling lipid metabolism, glucose regulation, and inflammation in the liver cells (Pan et al., 2024). PPARγ is a protective factor in liver cancer by some mechanisms, including inhibiting hepatic fibrosis progression and inflammation, suppressing tumor microenvironment remodeling, and promoting apoptosis and senescence in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells (Ishtiaq et al., 2022).

Additionally, genes involved in the MAPK signaling pathway include BRAF, c-Jun, ERK, JNK, MAP2K1, MAP2K4, MAPK14, and KRAS, which are genes affected by MPs in lung cancer cells. These genes are crucial for cell proliferation and survival, and their activation leads to the uncontrolled growth of cancer cells (Pradhan et al., 2019). Other genes, such as NLRP3, BCL2, and TIM4, are also affected by MPs in the mentioned cancer. The activation of NLRP3 creates chronic inflammation that promotes tumors by inducing DNA damage, enhancing angiogenesis, and suppressing apoptosis in cancer cells (Tang et al., 2020). The BCL2 gene contributes to the resistance of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) to Aurora kinase B (AURKB) inhibitors. It suppresses apoptosis and DNA damage caused by these inhibitors, allowing cells to avoid programmed cell death even under therapeutic stress (Ramkumar et al., 2023). TIM4 acts as an oncogene by supporting tumor cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and immune evasion, and also contributes to tumor immune tolerance by impairing antigen presentation and cytotoxic T cell responses (Liu et al., 2020).

Additionally, MPs affect NLRP3 in skin cancer cells. NLRP3 enhances inflammation, stimulates angiogenesis, and promotes the proliferation and migration of tumor cells (Ciazyn et al., 2020). Additionally, our study revealed that TIM4 is another gene in pancreatic cancer cells that MPs can influence. TIM4 is crucial in creating an immune-suppressive environment, enabling tumor cells to evade immune detection. It also supports tumor progression by reducing the effectiveness of immune cells, such as macrophages and T cells, in targeting cancer cells (Shi et al., 2021).

MPs may also influence the efficacy of cancer therapies. They can alter the metabolism and bioavailability of therapeutic drugs by interfering with their absorption and distribution in the body. This could lead to either reduced or enhanced drug activity, depending on the interactions between the MPs and the drugs (Deng et al., 2025). Interestingly, our study also shows that MPs can reduce and enhance the anti-cancer drug activity. However, according to the prior surveys and our study, MPs can deteriorate the impacts of anti-cancer drugs (Zhao et al., 2024) and exert this resistance against various anticancer agents.

The present study highlights the potential of certain microRNAs as candidate therapeutics in breast cancer models; however, these predictions are hypothesis-generating and require validation in experimental and clinical contexts (Zhao et al., 2019). Our in silico analysis highlights microRNAs targeting genes influenced by MPs in breast cancer cells, aligning with prior findings on their anti-breast cancer capabilities (Menbari et al., 2020). Specific microRNAs, including miR-483-3p, miR-365, miR-331-3p, and miR-138-5p, demonstrated strong binding affinity for genes such as ABCB1, ABCG2, AP2M1, PTP4A2, and TMBIM6, marking them as promising candidates for microRNA therapy. These microRNAs also target various molecular pathways, enhancing their anti-cancer effects (Liu et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2020; Rasoolnezhad et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2020). In-silico analysis also revealed miR-3613-3p’s potential to target FTH1, a gene involved in iron homeostasis and oxidative stress regulation in cancer cells (Di Sanzo et al., 2020), making it a key therapeutic candidate.

In addition to breast cancer, microRNAs also exhibit anti-cancer effects in cervical cancer (Hasanzadeh et al., 2019; Ding et al., 2021), colorectal cancer (Cheng et al., 2020), gastric cancer (Spitz and Gavathiotis, 2022), leukemia (Gil-Kulik et al., 2024; Xiao et al., 2024), liver cancer (K et al., 2020; Ramalingam et al., 2024), lung cancer (Pradhan et al., 2019; Naeli et al., 2020), pancreatic cancer (Li et al., 2021; Javadrashid et al., 2021), and skin cancer (Mohamm et al., 2021). Our study corroborates these findings, with in silico analyses revealing specific microRNAs that interact with key genes associated with tumorigenesis in these cancers. For instance, miR-302c-3p targets TIM4 in cervical cancer, miR-144 targets MUC2 in colorectal cancer, miR-706 and miR-665 target ASGR2 and CD44 in gastric cancer, and miR-532-3p and miR-593-5p target MAPK genes in lung cancer. These microRNAs demonstrate their therapeutic potential by influencing various molecular pathways, as shown in Figure 4. Overall, the study reinforces the growing potential of microRNAs as targeted therapies across multiple malignancies.

FIGURE 4

MicroRNAs with the in silico capability to suppress genes in MPs-based cancers and their possible targeted molecular pathways. The blue, red, green, and gray arrows represent activation (or upregulation), inhibition (or downregulation), regulation, and interaction, respectively. Moreover, yellow hexagons, blue ovals, and green ovals demonstrate microRNAs, targeted genes, and pathways affected by targeted genes, respectively. ABCB1, ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily B Member 1; ABCG2, ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily G Member 2; AP2M1, Adaptor Related Protein Complex 2 Subunit Mu 1; ASGR2, Asialoglycoprotein Receptor 2; Bax, BCL2 Associated X, Apoptosis Regulator; BCL2, B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2; BRAF, B-Raf Proto-Oncogene, Serine/Threonine Kinase; c-jun, Jun Proto-Oncogene, AP-1 Transcription Factor Subunit; CD44, CD44 Molecule (Indian Blood Group); ERK, Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase; FABP1, Fatty Acid Binding Protein 1; FTH1, Ferritin Heavy Chain 1; HO-1, Heme Oxygenase 1; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal Kinase; KRAS, KRAS Proto-Oncogene, GTPase; LXR-α, Liver X Receptor Alpha; MAP2K1, Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 1; MAP2K4, Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 4; MAPK14, Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase 14; MUC2, Mucin 2; NLRP3, NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3; NLRP3, NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3; PPARα, Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha; PPARγ, Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma; PTP4A2, Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Type IVA, Member 2; TMBIM6, Transmembrane BAX Inhibitor Motif Containing 6; TIM4, T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain Containing-4; TIM4, T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain Containing-4; TIM4, T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain Containing-4; TIM4, T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain Containing-4; TIM4, T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain Containing-4.

4.1 Limitations

First, studies linking MPs to gene changes are heterogeneous in polymer type, size, dose, and exposure model; many use surrogates (e.g., plastic-related compounds) rather than standardized particles. Second, mfe predictions do not demonstrate binding or regulation; off-targeting and RNA context effects are likely. Third, we did not perform a quantitative meta-analysis due to heterogeneity and incomplete reporting.

4.2 Future work

We propose a tiered pipeline: 1. verify MP-induced gene changes under standardized exposures; 2. validate miRNA targeting (luciferase wild-type/mutant, protein knockdown, rescue); 3. evaluate phenotypes (viability, invasion, efflux, radiosensitization) with and without MPs; 4. test delivery and safety in vivo.

5 Conclusion

MP exposure has been reported to perturb cancer-relevant genes and therapy responses across tumor types. Our in silico analyses nominate miRNAs that may counter these MP-associated programs. These findings are hypothesis-generating and require rigorous experimental and translational validation.

Statements

Author contributions

AB: Writing – review and editing, Visualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis. AZ: Investigation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft. NM: Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Validation, Data curation. NT: Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration. KZ: Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing, Visualization, Data curation. RSS: Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Project administration. RS: Writing – review and editing, Data curation. GY: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. AK: Writing – review and editing, Methodology, Validation. AU: Writing – review and editing, Data curation, Project administration. ANZ: Resources, Investigation, Writing – review and editing. AT: Project administration, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The study was supported by the grant financing on scientific programs of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan «Investigation of Microplastic Contamination in Packaged Foods and Water in Kazakhstan and Its Impact on Cancer Cell Proliferation: An In Vitro Study» (IRN AP26100885).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2025.1699693/full#supplementary-material

References

1

AlamS.MohammadT.PadderR. A.HassanM. I.HusainM. (2022a). Thymoquinone and quercetin induce enhanced apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer in combination through the Bax/Bcl2 cascade. J. Cell Biochem.123 (2), 259–274. 10.1002/jcb.30162

2

AlamM.AlamS.ShamsiA.AdnanM.ElasbaliA. M.Al-SoudW. A.et al (2022b). Bax/Bcl-2 Cascade is regulated by the EGFR pathway: therapeutic targeting of non-small cell lung cancer. Front. Oncol.12, 869672. 10.3389/fonc.2022.869672

3

AlharbiK. S.AlmalkiW. H.AlbrattyM.MerayaA. M.NajmiA.VyasG.et al (2022). The therapeutic role of nutraceuticals targeting the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway in liver cancer. J. Food Biochem.46 (10), e14357. 10.1111/jfbc.14357

4

AliA.ShafarinJ.Abu JabalR.AljabiN.HamadM.SualehM. J.et al (2021). Ferritin heavy chain (FTH1) exerts significant antigrowth effects in breast cancer cells by inhibiting the expression of c-MYC. FEBS Open Bio11 (11), 3101–3114. 10.1002/2211-5463.13303

5

AltamuraC.GavazzoP.PuschM.DesaphyJ. F. (2022). Ion channel involvement in tumor drug resistance. J. Pers. Med.12 (2), 210. 10.3390/jpm12020210

6

AstutiY.RaymantM.QuarantaV.ClarkeK.AbudulaM.SmithO.et al (2024). Efferocytosis reprograms the tumor microenvironment to promote pancreatic cancer liver metastasis. Nat. Cancer5 (5), 774–790. 10.1038/s43018-024-00731-2

7

BaraniM. (2024). The role of environmental education in improving human health: literature review. West Kazakhstan Med. J.66 (4), 373–386. 10.18502/wkmj.v66i4.17769

8

BoranT.ZenginO. S.SekerZ.AkyildizA. G.KaraM.OztasE.et al (2024). An evaluation of a hepatotoxicity risk induced by the microplastic polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) using HepG2/THP-1 co-culture model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int.31 (20), 28890–28904. 10.1007/s11356-024-33086-3

9

Brynzak-SchreiberE.SchoglE.BappC.CsehK.KopatzV.JakupecM. A.et al (2024). Microplastics role in cell migration and distribution during cancer cell division. Chemosphere353, 141463. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.141463

10

CaronniN.PipernoG. M.SimoncelloF.RomanoO.VodretS.YanagihashiY.et al (2021). TIM4 expression by dendritic cells mediates uptake of tumor-associated antigens and anti-tumor responses. Nat. Commun.12 (1), 2237. 10.1038/s41467-021-22535-z

11

ChenY.ZengQ.LuoY.SongM.HeX.ShengH.et al (2024a). Polystyrene microplastics aggravate radiation-induced intestinal injury in mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.283, 116834. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.116834

12

ChenT.LinQ.GongC.ZhaoH.PengR. (2024b). Research progress on micro (nano)Plastics exposure-induced miRNA-Mediated biotoxicity. Toxics12 (7), 475. 10.3390/toxics12070475

13

ChenY.ZhangZ.JiK.ZhangQ.QianL.YangC. (2025). Role of microplastics in the tumor microenvironment (review). Oncol. Lett.29 (4), 193. 10.3892/ol.2025.14939

14

ChengB.ZhangY.WuZ. W.CuiZ. C.LiW. L. (2020). MiR-144 inhibits colorectal cancer cell migration and invasion by regulating PBX3. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci.24 (18), 9361–9369. 10.26355/eurrev_202009_23019

15

ChouleurT.EmanuelliA.SouleyreauW.DerieppeM. A.LeboucqT.HardyS.et al (2024). PTP4A2 promotes glioblastoma progression and macrophage polarization under microenvironmental pressure. Cancer Res. Commun.4 (7), 1702–1714. 10.1158/2767-9764.CRC-23-0334

16

CiazynskaM.BednarskiI. A.WodzK.NarbuttJ.LesiakA. (2020). NLRP1 and NLRP3 inflammasomes as a new approach to skin carcinogenesis. Oncol. Lett.19 (3), 1649–1656. 10.3892/ol.2020.11284

17

DamianiD.TiribelliM. (2023). ABCG2 in acute myeloid leukemia: old and new perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24 (8), 7147. 10.3390/ijms24087147

18

DengX.GuiY.ZhaoL. (2025). The micro(nano)plastics perspective: exploring cancer development and therapy. Mol. Cancer24 (1), 30. 10.1186/s12943-025-02230-z

19

Di SanzoM.QuaresimaB.BiamonteF.PalmieriC.FanielloM. C. (2020). FTH1 pseudogenes in cancer and cell metabolism. Cells9 (12), 2554. 10.3390/cells9122554

20

DingH. M.ZhangH.WangJ.ZhouJ. H.ShenF. R.JiR. N.et al (2021). miR-302c-3p and miR-520a-3p suppress the proliferation of cervical carcinoma cells by targeting CXCL8. Mol. Med. Rep.23 (5), 322–10. 10.3892/mmr.2021.11961

21

FranczykB.RyszJ.Gluba-BrzozkaA. (2022). Pharmacogenetics of drugs used in the treatment of cancers. Genes (Basel)13 (2), 311. 10.3390/genes13020311

22

Gil-KulikP.KluzN.PrzywaraD.PetniakA.WasilewskaM.Fraczek-ChudzikN.et al (2024). Potential use of exosomal non-coding MicroRNAs in leukemia therapy: a systematic review. Cancers (Basel)16 (23), 3948. 10.3390/cancers16233948

23

HaleR. C.SeeleyM. E.La GuardiaM. J.MaiL.ZengE. Y. (2020). A global perspective on microplastics. J. Geophys. Research-Oceans125 (1), e2018JC014719. 10.1029/2018JC014719

24

HanN.YuanM.YanL.TangH. (2023). Emerging insights into liver X receptor alpha in the tumorigenesis and therapeutics of human cancers. Biomolecules13 (8), 1184. 10.3390/biom13081184

25

HasanzadehM.MovahediM.RejaliM.MalekiF.Moetamani-AhmadiM.SeifiS.et al (2019). The potential prognostic and therapeutic application of tissue and circulating microRNAs in cervical cancer. J. Cell Physiol.234 (2), 1289–1294. 10.1002/jcp.27160

26

HsuH. P.LaiM. D.LeeJ. C.YenM. C.WengT. Y.ChenW. C.et al (2017). Mucin 2 silencing promotes colon cancer metastasis through interleukin-6 signaling. Sci. Rep.7 (1), 5823. 10.1038/s41598-017-04952-7

27

HuX.YuQ.Gatheru WaigiM.LingW.QinC.WangJ.et al (2022). Microplastics-sorbed phenanthrene and its derivatives are highly bioaccessible and may induce human cancer risks. Environ. Int.168, 107459. 10.1016/j.envint.2022.107459

28

IranmaneshH.MajdA.MojaradE. N.ZaliM. R.HashemiM. (2021). Investigating the relationship between the expression level of mucin gene cluster (MUC2, MUC5A, and MUC5B) and clinicopathological characterization of colorectal cancer. Galen. Med. J.10, e2030. 10.31661/gmj.v10i0.2030

29

IshtiaqS. M.ArshadM. I.KhanJ. A. (2022). PPARγ signaling in hepatocarcinogenesis: mechanistic insights for cellular reprogramming and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol. Ther.240, 108298. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2022.108298

30

JainA. S.PrasadA.PradeepS.DharmashekarC.AcharR. R.EkaterinaS.et al (2021). Everything old is new again: drug repurposing approach for non-small cell lung cancer targeting MAPK signaling pathway. Front. Oncol.11, 741326. 10.3389/fonc.2021.741326

31

JangB. I.LiY.GrahamD. Y.CenP. (2011). The role of CD44 in the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy of gastric cancer. Gut Liver5 (4), 397–405. 10.5009/gnl.2011.5.4.397

32

JavadrashidD.MohammadzadehR.BaghbanzadehA.SafaeeS.AminiM.LotfiZ.et al (2021). Simultaneous microRNA-612 restoration and 5-FU treatment inhibit the growth and migration of human PANC-1 pancreatic cancer cells. EXCLI J.20, 160–173. 10.17179/excli2020-2900

33

JiaS.YangY.ZhuY.YangW.LingL.WeiY.et al (2024). Association of FTH1-Expressing circulating tumor cells with efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for patients with breast cancer: a prospective cohort study. Oncologist29 (1), e25–e37. 10.1093/oncolo/oyad195

34

JunjappaR. P.KimH. K.ParkS. Y.BhattaraiK. R.KimK. W.SohJ. W.et al (2019). Expression of TMBIM6 in cancers: the involvement of Sp1 and PKC. Cancers (Basel)11 (7), 974. 10.3390/cancers11070974

35

KarbasforooshanH.HayesA. W.MohammadzadehN.ZirakM. R.KarimiG. (2020). The possible role of sirtuins and microRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. Cell Cycle19 (23), 3209–3221. 10.1080/15384101.2020.1843813

36

KC. P.MaharjanA.AcharyaM.LeeD.KusmaS.GautamR.et al (2023). Polytetrafluorethylene microplastic particles mediated oxidative stress, inflammation, and intracellular signaling pathway alteration in human derived cell lines. Sci. Total Environ.897, 165295. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165295

37

KaliyevA. A.MussinN. M.TamadonA. (2024). The importance of mesenchymal stromal/stem cell therapy for cancer. West Kazakhstan Med. J., 106–110. 10.18502/wkmj.v66i2.16452

38

KimH.ZaheerJ.ChoiE. J.KimJ. S. (2022). Enhanced ASGR2 by microplastic exposure leads to resistance to therapy in gastric cancer. Theranostics12 (7), 3217–3236. 10.7150/thno.73226

39

KumarN.LambaM.PacharA. K.YadavS.AcharyaA. (2024). Microplastics - a growing concern as carcinogens in cancer etiology: emphasis on biochemical and molecular mechanisms. Cell Biochem. Biophysics82 (4), 3109–3121. 10.1007/s12013-024-01436-0

40

LiX.JiangW.GanY.ZhouW. (2021). The application of exosomal MicroRNAs in the treatment of pancreatic cancer and its research progress. Pancreas50 (1), 12–16. 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001713

41

LiS.KeenanJ. I.ShawI. C.FrizelleF. A. (2023). Could microplastics be a driver for early onset colorectal cancer?Cancers (Basel)15 (13), 3323. 10.3390/cancers15133323

42

LiuF.ZhuangL.WuR. X.LiD. Y. (2019). miR-365 inhibits cell invasion and migration of triple negative breast cancer through ADAM10. J. Buon24 (5), 1905–1912.

43

LiuW.XuL.LiangX.LiuX.ZhaoY.MaC.et al (2020). Tim-4 in health and disease: friend or foe?Front. Immunol.11, 537. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00537

44

LiuQ.Bautista-GomezJ.HigginsD. A.YuJ.XiongY. (2021). Dysregulation of the AP2M1 phosphorylation cycle by LRRK2 impairs endocytosis and leads to dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Sci. Signal14 (693), eabg3555. 10.1126/scisignal.abg3555

45

LiuX.ZhaoX.YangJ.WangH.PiaoY.WangL. (2023). High expression of AP2M1 correlates with worse prognosis by regulating immune microenvironment and drug resistance to R-CHOP in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Eur. J. Haematol.110 (2), 198–208. 10.1111/ejh.13895

46

MenbariM. N.RahimiK.AhmadiA.Mohammadi-YeganehS.ElyasiA.DarvishiN.et al (2020). miR-483-3p suppresses the proliferation and progression of human triple negative breast cancer cells by targeting the HDAC8>oncogene. J. Cell Physiol.235 (3), 2631–2642. 10.1002/jcp.29167

47

MiaoL.GuoS.LinC. M.LiuQ.HuangL. (2017). Nanoformulations for combination or cascade anticancer therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.115, 3–22. 10.1016/j.addr.2017.06.003

48

MohammadiM.SpotinA.Mahami-OskoueiM.ShanehbandiD.AhmadpourE.CasulliA.et al (2021). MicroRNA-365 promotes apoptosis in human melanoma cell A375 treated with hydatid cyst fluid of Echinococcus granulosus sensu stricto. Microb. Pathog.153, 104804. 10.1016/j.micpath.2021.104804

49

MünzC. (2020). Autophagy proteins influence endocytosis for MHC restricted antigen presentation (Elsevier).

50

NaeliP.YousefiF.GhasemiY.SavardashtakiA.MirzaeiH. (2020). The role of MicroRNAs in lung cancer: implications for diagnosis and therapy. Curr. Mol. Med.20 (2), 90–101. 10.2174/1566524019666191001113511

51

PanY.LiY.FanH.CuiH.ChenZ.WangY.et al (2024). Roles of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) in the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Biomed. Pharmacother.177, 117089. 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.117089

52

ParkJ. H.HongS.KimO. H.KimC. H.KimJ.KimJ. W.et al (2023). Polypropylene microplastics promote metastatic features in human breast cancer. Sci. Rep.13 (1), 6252. 10.1038/s41598-023-33393-8

53

PradhanR.SinghviG.DubeyS. K.GuptaG.DuaK. (2019). MAPK pathway: a potential target for the treatment of non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Future Med. Chem.11 (8), 793–795. 10.4155/fmc-2018-0468

54

RamalingamP. S.ElangovanS.MekalaJ. R.ArumugamS. (2024). Liver X receptors (LXRs) in cancer-an Eagle's view on molecular insights and therapeutic opportunities. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.12, 1386102. 10.3389/fcell.2024.1386102

55

RamkumarK.TanimotoA.Della CorteC. M.StewartC. A.WangQ.ShenL.et al (2023). Targeting BCL2 overcomes resistance and augments response to Aurora kinase B inhibition by AZD2811 in small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res.29 (16), 3237–3249. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-23-0375

56

RasoolnezhadM.SafaralizadehR.HosseinpourfeiziM. A.Banan-KhojastehS. M.BaradaranB. (2021). MiRNA-138-5p: a strong tumor suppressor targeting PD-L-1 inhibits proliferation and motility of breast cancer cells and induces apoptosis. Eur. J. Pharmacol.896, 173933. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.173933

57

RobinsonK. S.SennhennP.YuanD. S.LiuH.TaddeiD.QianY.et al (2025). TMBIM6/BI-1 is an intracellular environmental regulator that induces paraptosis in cancer via ROS and Calcium-activated ERAD II pathways. Oncogene44 (8), 494–512. 10.1038/s41388-024-03222-x

58

RoselliniM.TurunenP.EfferthT. (2023). Impact of plastic-related compounds on P-Glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein in vitro. Molecules28 (6), 2710. 10.3390/molecules28062710

59

ShabaniF.MahdaviM.ImaniM.Hosseinpour-FeiziM. A.GheibiN. (2020). Calprotectin (S100A8/S100A9)-induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis in human gastric cancer AGS cells: alteration in expression levels of Bax, Bcl-2, and ERK2. Hum. Exp. Toxicol.39 (8), 1031–1045. 10.1177/0960327120909530

60

ShenS.ZhangS.LiuP.WangJ.DuH. (2020). Potential role of microRNAs in the treatment and diagnosis of cervical cancer. Cancer Genet.248-249, 25–30. 10.1016/j.cancergen.2020.09.003

61

ShenJ.YangH.QiaoX.ChenY.ZhengL.LinJ.et al (2023). The E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM17 promotes gastric cancer survival and progression via controlling BAX stability and antagonizing apoptosis. Cell Death Differ.30 (10), 2322–2335. 10.1038/s41418-023-01221-1

62

ShiB.ChuJ.HuangT.WangX.LiQ.GaoQ.et al (2021). The scavenger receptor MARCO expressed by tumor-associated macrophages are highly associated with poor pancreatic cancer prognosis. Front. Oncol.11, 771488. 10.3389/fonc.2021.771488

63

ShinJ.NileA.OhJ. W. (2021). Role of adaptin protein complexes in intracellular trafficking and their impact on diseases. Bioengineered12 (1), 8259–8278. 10.1080/21655979.2021.1982846

64

ShinY.ChoiH. Y.KwakY.YangG. M.JeongY.JeonT. I.et al (2023). TMBIM6-mediated miR-181a expression regulates breast cancer cell migration and invasion via the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. J. Cancer14 (4), 554–572. 10.7150/jca.81600

65

SpitzA. Z.GavathiotisE. (2022). Physiological and pharmacological modulation of BAX. Trends Pharmacol. Sci.43 (3), 206–220. 10.1016/j.tips.2021.11.001

66

SuchaS.SorfA.SvorenM.VagiannisD.AhmedF.VisekB.et al (2022). ABCB1 as a potential beneficial target of midostaurin in acute myeloid leukemia. Biomed. Pharmacother.150, 112962. 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.112962

67

SunL.LiuH.YeY.LeiY.IslamR.TanS.et al (2023). Smart nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther.8 (1), 418. 10.1038/s41392-023-01642-x

68

SzczepanekJ.SkorupaM.TretynA. (2022). MicroRNA as a potential therapeutic molecule in cancer. Cells11 (6), 1008. 10.3390/cells11061008

69

TangD.LiuH.ZhaoY.QianD.LuoS.PatzE. F.Jr.et al (2020). Genetic variants of BIRC3 and NRG1 in the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway are associated with non-small cell lung cancer survival. Am. J. Cancer Res.10 (8), 2582–2595.

70

TangW.SunG.JiG. W.FengT.ZhangQ.CaoH.et al (2023). Single-cell RNA-sequencing atlas reveals an FABP1-dependent immunosuppressive environment in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer11 (11), e007030. 10.1136/jitc-2023-007030

71

VethaakA. D.LeglerJ. (2021). Microplastics and human health. Science.371 (6530), 672–674. 10.1126/science.abe5041

72

WangY.FangZ.HongM.YangD.XieW. (2020). Long-noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in drug metabolism and disposition, implications in cancer chemo-resistance. Acta Pharm. Sin. B10 (1), 105–112. 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.09.011

73

WangW.MinK.ChenG.ZhangH.DengJ.LvM.et al (2021). Use of bioinformatic database analysis and specimen verification to identify novel biomarkers predicting gastric cancer metastasis. J. Cancer12 (19), 5967–5976. 10.7150/jca.58768

74

WangY.XuX.JiangG. (2023). Microplastics exposure promotes the proliferation of skin cancer cells but inhibits the growth of normal skin cells by regulating the inflammatory process. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.267, 115636. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.115636

75

WiniarskaE.JutelM.Zemelka-WiacekM. (2024). The potential impact of nano- and microplastics on human health: understanding human health risks. Environ. Res.251 (Pt 2), 118535. 10.1016/j.envres.2024.118535

76

XiaoJ.WanF.TianL.LiY. (2024). Tumor suppressor miR-520a inhibits cell growth by negatively regulating PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in acute myeloid leukemia. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med.33 (7), 729–738. 10.17219/acem/171299

77

XueS.MaM.BeiS.LiF.WuC.LiH.et al (2021). Identification and validation of the immune regulator CXCR4 as a novel promising target for gastric cancer. Front. Immunol.12, 702615. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.702615

78

YanX.ZhangY.LuY.HeL.QuJ.ZhouC.et al (2020). The complex toxicity of tetracycline with polystyrene spheres on gastric cancer cells. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health17 (8), 2808. 10.3390/ijerph17082808

79

YuM.LinC.WeiM. (2023). A pan-cancer analysis of oncogenic protein tyrosine phosphatase subfamily PTP4As. J. Holist. Integr. Pharm.4 (2), 185–198. 10.1016/j.jhip.2023.07.001

80

ZavrosY. (2017). Initiation and maintenance of gastric cancer: a focus on CD44 variant isoforms and cancer stem cells. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.4 (1), 55–63. 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.03.003

81

ZhangY. S.YangC.HanL.LiuL.LiuY. J. (2022). Expression of BCRP/ABCG2 protein in invasive breast cancer and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Oncol. Res. Treat.45 (3), 94–101. 10.1159/000520871

82

ZhaoJ.LiD.FangL. (2019). MiR-128-3p suppresses breast cancer cellular progression via targeting LIMK1. Biomed. Pharmacother.115, 108947. 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108947

83

ZhaoM.ZhangM.TaoZ.CaoJ.WangL.HuX. (2020). miR-331-3p suppresses cell proliferation in TNBC cells by downregulating NRP2. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat.19, 1533033820905824. 10.1177/1533033820905824

84

ZhaoJ.ZhangH.ShiL.JiaY.ShengH. (2024). Detection and quantification of microplastics in various types of human tumor tissues. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.283, 116818. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.116818

85

ZhouZ.ZhouQ.WuX.XuS.HuX.TaoX.et al (2020a). VCAM-1 secreted from cancer-associated fibroblasts enhances the growth and invasion of lung cancer cells through AKT and MAPK signaling. Cancer Lett.473, 62–73. 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.12.039

86

ZhouZ. G.XuC.DongZ.WangY. P.DuanJ. Y.YanC. Q. (2020b). MiR-497 inhibits cell proliferation and invasion ability by targeting HMGA2 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci.24 (1), 122–129. 10.26355/eurrev_202001_19901

Summary

Keywords

microplastics, microRNAs, cancer, therapy resistance, in silico, RNAhybrid

Citation

Baspakova A, Zare A, Mussin NM, Tanideh N, Zhilisbayeva KR, Safarzoda Sharoffidin R, Suleimenova R, Yelgondina G, Kaliyeva AE, Umbetova AA, Zinaliyeva A and Tamadon A (2025) In-silico pharmacological insights into the therapeutic potential of microRNAs for microplastic-associated cancers. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 13:1699693. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2025.1699693

Received

05 September 2025

Revised

17 October 2025

Accepted

29 October 2025

Published

25 November 2025

Volume

13 - 2025

Edited by

Angelo Sparaneo, IRCCS Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza Hospital, Italy

Reviewed by

Sevgi Marakli, Yıldız Technical University, Türkiye

Zixuan Gou, Peking University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Baspakova, Zare, Mussin, Tanideh, Zhilisbayeva, Safarzoda Sharoffidin, Suleimenova, Yelgondina, Kaliyeva, Umbetova, Zinaliyeva and Tamadon.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amin Tamadon, amintamaddon@yahoo.com

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.