- 1Department of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing, China

- 2Institute of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, Peking University, Beijing, China

Background: Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection represents a prevalent global health burden. Current eradication strategies are complicated by increasing antibiotic resistance and detrimental alterations to the gut microbiome. Jinghuaweikang capsule (JWC), a traditional Chinese medicine, has demonstrated efficacy against H. pylori, yet its mechanisms involving microbiota-inflammation interactions remain incompletely elucidated.

AIM: This study aimed to investigate the effects of the JWC on gastric mucosal inflammation and the expression of drug-resistance genes in H. pylori-infected mice.

Methods: Sixty Kunming mice were randomly allocated into six groups, including normal control group (Control), model group (Model), Western medicine triple group (AC), low-dose JWC group (JWCL), medium-dose JWC group (JWCM), and high-dose JWC group (JWCH). A mouse model of H. pylori infection was established by intragastric administration of an H. pylori SS1 solution for two weeks. The efficacy of this model was evaluated using rapid urease test (RUT) and Warthin-Starry (WS) silver stain. Subsequently, the experimental cohort of mice underwent pharmacological intervention. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) were used to assess the impact of JWC on inflammation within the gastric mucosa of mice infected with H. pylori. Metagenomic sequencing technology was used to identify alterations in the intestinal microbiota and antibiotic resistance genes in the murine models. Western blotting was used to assess the expression levels of proteins involved in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway.

Results: JWC mitigated gastric mucosal inflammation induced by H. pylori infection and reduced the concentrations of interleukin- (IL-) 6, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) while inhibiting gene expression level. Metagenomic sequencing revealed that triple therapy in Western medicine markedly diminished the diversity of the intestinal microbiota while elevating the abundance of antibiotic-resistance genes, including macB, arlR, evgS, tetA(58), and mtrA. The diversity and richness of the intestinal microbiota in the JWC group were comparable to those in the control group, with an increase in the abundance of beneficial bacteria such as Muribaculaceae_bacterium. Furthermore, the expression levels of the antibiotic resistance genes macB, tetA(58), bcrA, oleC, and arlS were downregulated. Moreover, the activation of MAPK signaling pathway components phospho-ERK and phospho-p38 was inhibited.

Conclusion: JWC preserves microbial diversity and promotes a beneficial compositional shift, mitigates the risk of antibiotic resistance, modulates the MAPK signaling pathway, and alleviates gastric mucosal inflammation in mice infected with H. pylori.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), a prominent gut microbe, is among the most extensively studied bacteria. The global prevalence of H. pylori infection is estimated to be 48.5%, and approximately 55.8% of the population in China is affected by this infection (Hooi et al., 2017). Eradicating H. pylori can mitigate gastric mucosal inflammation and decrease the risk of developing gastric cancer (Helicobacter pylori Group CSoG and Zhou, 2022). The widespread implementation of triple or quadruple therapies, comprising proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and antibiotics, as the primary strategy for eradicating H. pylori has resulted in the emergence of antibiotic resistance and disruption of the intestinal microbiota (Liou et al., 2019; Liou et al., 2020). Recently, the global prevalence of H. pylori antibiotic resistance has escalated to a concerning level (Herzlinger et al., 2023; Wang Y. et al., 2023; Hong et al., 2024; Okimoto et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2024). Moreover, gut microbiota dysbiosis has been increasingly recognized as a key contributor to the persistence of H. pylori infection and the associated inflammatory response. Furthermore, disruption of the intestinal microbiota is associated with an increased risk of various human diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (Nguyen et al., 2020), obesity (Cox and Blaser, 2015), colorectal cancer (Akimoto et al., 2021), and gastrointestinal infections (Johnson et al., 1999; Lynch and Martinez, 2002). The duration and dosage of antibiotics can no longer be increased further, and the range of available antibiotics is severely restricted. The search for new paths to eradicate H. pylori is an inevitable path for treating H. pylori.

In contrast to conventional antibiotic-based regimens, traditional Chinese medicine offers a holistic approach that may restore microbial diversity and mitigate inflammation with fewer adverse effects on commensal flora (Qu et al., 2022; Gong et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024). However, the precise mechanisms underlying these beneficial effects remain poorly understood, necessitating further investigation. Jinghuaweikang capsule (JWC) is the most frequently utilized traditional Chinese medicine for the clinical management of H. pylori, formulated from potent ingredients derived from chenopodium ambrosioides and adina pilulifera. Additionally, JWC is the sole traditional Chinese medicine explicitly endorsed by the guidelines for managing refractory H. pylori infections (Helicobacter pylori Study Group, 2022). Previous in vitro research has demonstrated that JWC and chenopodium oil can inhibit and eradicate standard and resistant H. pylori strains. Furthermore, JWC has been demonstrated to reduce the expression of the hefABC active efflux pump system in H. pylori (Liu, 2014), and chenopodium oil effectively inhibits the formation of biofilms associated with resistant H. pylori (Zhang et al., 2020). In addition, the combination of JWC with bismuth therapy in triple or quadruple regimens has been exhibited to enhance the eradication rate of H. pylori, alleviate clinical symptoms, and decrease the incidence of adverse events in patients with H. pylori-related gastritis (Wang et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013). Despite these promising findings, in vivo studies on the mechanism of JWC against H. pylori remain scarce. In this study, we investigated the impact of JWC on the intestinal microbiota and antibiotic-resistance genes through metagenomic sequencing. Moreover, we evaluated the effect of JWC on gastric mucosal inflammation and examined the changes in MAPK pathway proteins in H. pylori-infected mice.

Materials and methods

Culture and collection of H. pylori strains

The standard H. pylori strain SS1, which is positive for both the cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) and the vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA), generously provided by the Department of Gastroenterology at Peking University First Hospital, was preserved at −80°C in a low-temperature freezer. The cryopreservation solution was formulated using Brain Heart Infusion (OXOID, Basingstoke, UK) in conjunction with glycerol (Solarbio, Beijing, China). The bacterial suspension was inoculated onto Columbia blood agar plates (OXOID, Basingstoke, UK) enriched with 8% sheep blood (LABLEAD, Beijing, China) and incubated under microaerophilic conditions (85% N2, 10% CO2, and 5% O2) at 37°C for 48–72 h (Lin et al., 2024). Subsequently, the positive colonies were subcultured. The bacteria were collected in Brucella broth (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) before intragastric administration.

Preparation of intervention drugs

The volatile oil of JWC (Tianshi Li, Tianjin, China) exhibited a density of 937 mg/mL, was dissolved in edible oil, and then administered by gavage. The pharmaceutical powders of amoxicillin (Aladdin, Shanghai, China), clarithromycin (Aladdin, Shanghai, China), and lansoprazole (Aladdin, Shanghai, China) were solubilized in double-distilled water and administered by gavage. The representative gas chromatographic fingerprint of JWC is provided in Supplementary Material Figure S1.

Grouping and handling experimental animals

Sixty specific pathogen-free male Kunming (KM) mice (Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd.) weighing between 18 and 22 g were kept in a barrier environment at the Experimental Animal Center of Peking University First Hospital (license number: SCXK (Jing) 2024-0005). The mice were adaptively housed for three days, during which they had unrestricted access to water and food.

The mice in the other groups were administered cyclophosphamide (200 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal injection to transiently suppress the immune system and facilitate the subsequent colonization of H. pylori (Ye et al., 2015), followed by intragastric administration of 0.3 mL H. pylori SS1 solution (12×108 CFU/mL) every other day for seven doses. The mice in the Control group received an equivalent volume of normal saline through intraperitoneal injection and intragastric administration. Two weeks following the final gavage, one mouse from each group was randomly sacrificed to assess H. pylori colonization using rapid urease test (RUT) and Warthin-Starry (WS) silver stain.

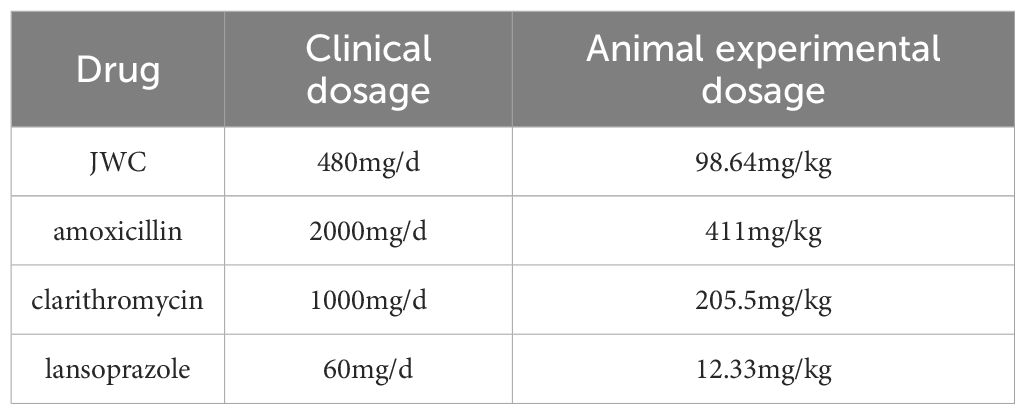

Following the successful establishment of the model, the drug intervention was administered the following day. The dosages used for the animal experiments are detailed in Table 1. For an adult weighing 60 kg, the conversion formula was Db = Da × Rab, where the conversion coefficient Rab was 12.33. The JWCH group received JWC at the clinical equivalent dose (98.64 mg/kg), while the JWCL and JWCM groups were administered JWC at one-quarter (24.66 mg/kg) and one-half (49.32 mg/kg) of this dose, respectively. Control and Model mice received equal volumes of physiological saline via gastric lavage. The mice were euthanized 14 days after oral administration, antral tissues were harvested, serum was separated, and intestinal contents were collected (Figure 1a). The body weight and behavioral patterns of the mice were monitored weekly during the gavage procedure. The experimental protocol was approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital (approval number: J202122).

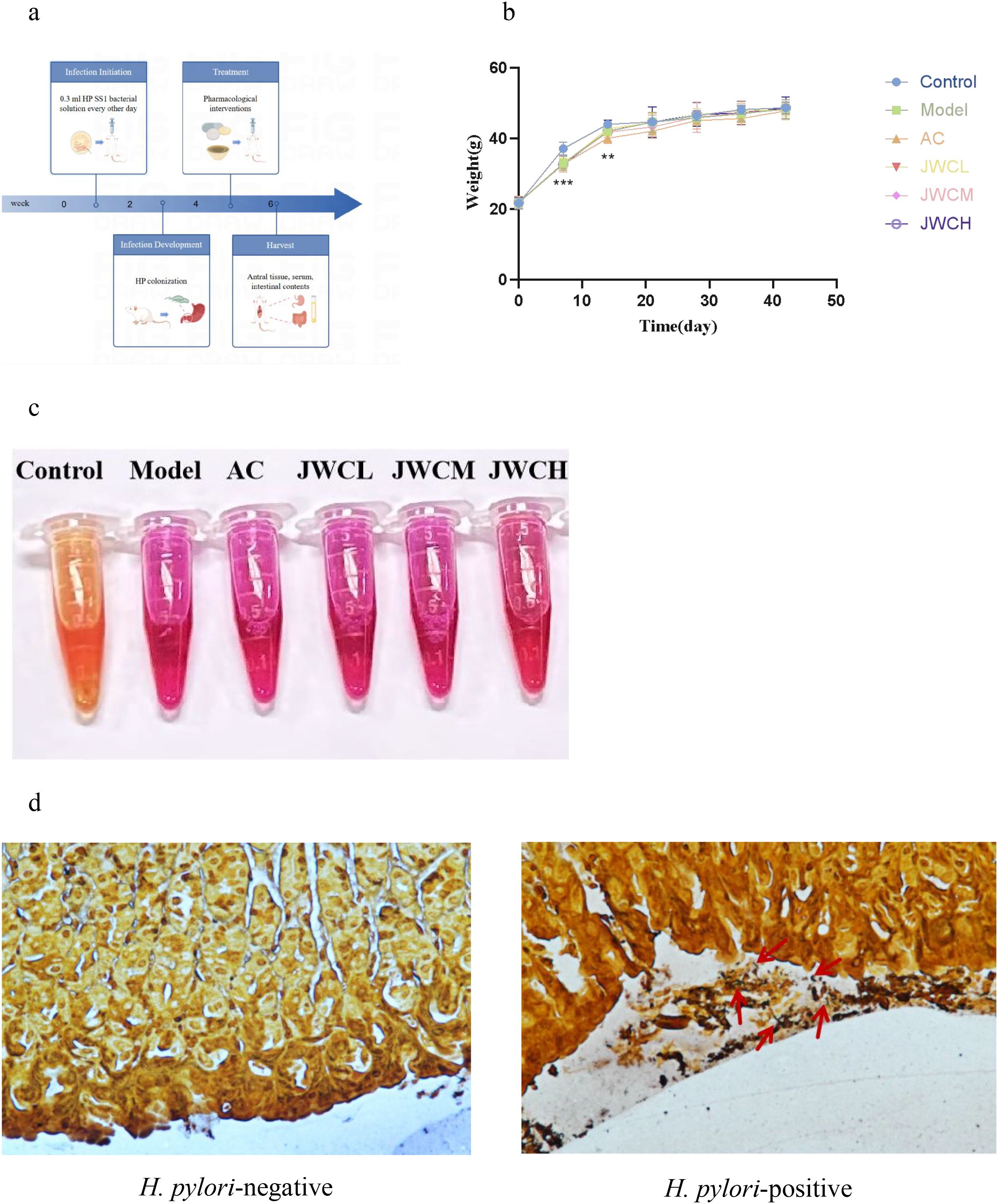

Figure 1. Animal treatment and model determination. (a) Flow chart of modeling and drug intervention. (b) Changes in body weight of mice during modeling and drug intervention. (c) RUT. The solution turning red indicated the presence of H. pylori infection. (d) WS. The red arrow indicated H. pylori colonized in the gastric mucosa.

Rapid urease test

The entire stomach of each mouse was isolated, an incision was made along the greater curvature, the gastric contents were thoroughly rinsed with distilled water, and a portion of the gastric antral tissue was subsequently transferred into an Eppendorf tube containing rapid urease solution. Any color changes were monitored in the solution, and these observations were documented using photographs. It was necessary to focus on the sampling site and ensure that the tissue size was consistent in each group. The sampling tools were sterilized to avoid cross-contamination.

Warthin–Starry silver stain

The WS silver stain kit (Beijing Solarbio Technology Co. LTD. Beijing, China) was used for the subsequent experiment. The paraffin sections of mouse gastric antral tissue sections were deparaffinized in water and then stained in acidic Ag solution in a water bath at 56°C for 1 h. The sections were immersed in the prepared staining solution (B1: B2: B3 = 3:9:4) and placed in a water bath at 56°C. They were stained until a yellow-brown color was achieved, subsequently removed, and washed with preheated distilled water at 56°C. The sections were removed until they turned yellowish-brown color and then rinsed with preheated distilled water at a temperature of 56°C. The sections were dehydrated in absolute ethanol, clarified in xylene, and sealed with neutral gum. Finally, the sections were photographed and analyzed under a microscope. The precautions for tissue sampling were the same as before.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

The antrum tissue sections of the mice were deparaffinized and hydrated, followed by staining the nucleus with hematoxylin and the cytoplasm with eosin. Subsequently, dehydration was performed again, followed by xylene transparency. Finally, the slices were sealed with neutral gum to fix them and prevent deformation.

Measurement of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α in supernatants of mouse gastric antral tissue

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for IL-6 (RK00008, ABclonal), IL-1β (RK00006, ABclonal), and TNF-α (RK00027, ABclonal) were used to detect the levels of inflammatory factors in the supernatants of the gastric antral tissue.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

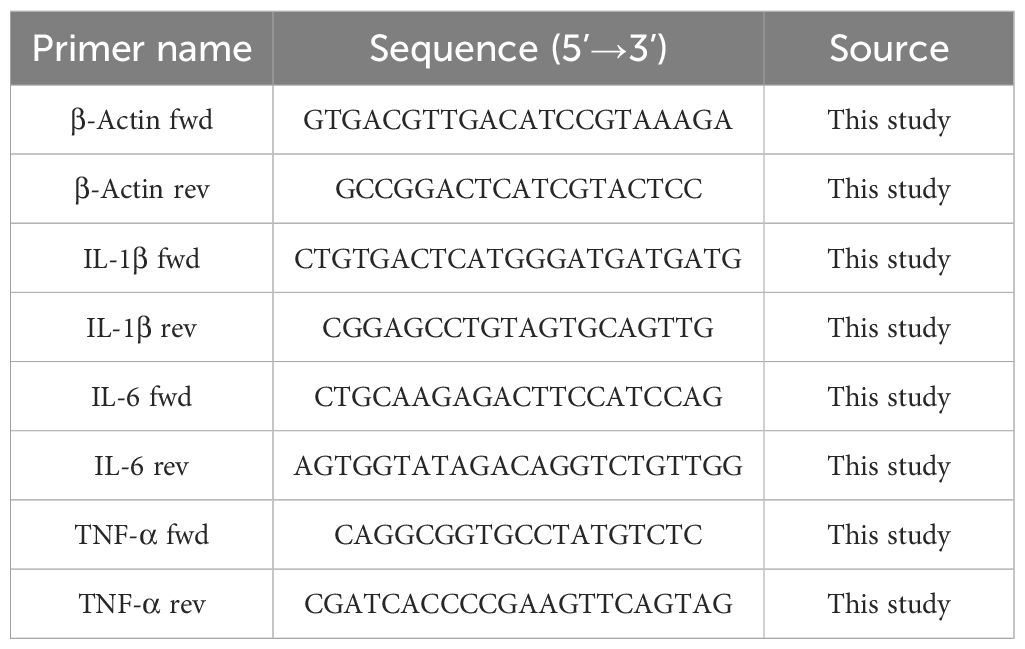

RNA was extracted from the gastric antral tissue of mice using TRIzol reagent. Following the determination of the RNA concentration, complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using a cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara, Japan). The relative expression levels of mRNA were quantified employing the 2−△△Ct method (Chu et al., 2022). The primer sequences utilized for quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) are presented in Table 2. β-Actin served as the reference gene.

Western blotting

Protein concentration was assayed in RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors and PMSF using a bicinchoninic acid kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Electrophoresis was performed using 4%–12% precast gels (LABLEAD, Beijing, China) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, USA). The membranes were blocked in 5% BSA for 1 h at room temperature and then stored overnight at 4°C containing the corresponding antibodies. After washing the membranes with TBST, the secondary antibodies were left at room temperature for 1 h. Images of the membranes were obtained using a BIO-RAD instrument (BIO-RAD Laboratories, Hercules, USA). The following antibodies were used: β-Actin (4970S; 1:1000; CST), anti-p38 (8690T; 1:1000; CST), anti-p-p38 (4511T; 1:1000; CST), anti-ERK (4695T; 1:1000; CST), and anti-p-ERK (4370T; 1:1000; CST).

Macrogenome sequencing

The purity and integrity of the extracted DNA samples were assessed using agarose gel electrophoresis. The DNA was subsequently fragmented to obtain a fragment size of approximately 350 bp using Covaris M220 (Gene Corporation, China). PE libraries were constructed using end repair, adaptor addition, and PCR. Library sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq™ X Plus platform (Illumina, USA). The sequence assembly was optimized using MEGAHIT software (https://github.com/voutcn/megahit, version 1.1.2). Gene prediction was conducted using Prodigal software (https://github.com/hyattpd/Prodigal, version 2.6.3), and gene indexes, along with their abundances, were obtained. Diamond software (https://github.com/bbuchfink/diamond, version 2.0.13) was used for non-redundant gene set comparison against amino acid sequences in the NR database and taxonomic species annotation from the corresponding NR library database information. The abundance of each species was calculated by summing up the abundances of its corresponding genes. Unigenes were compared against functional databases, such as The Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) and The Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD), using DIAMOND software for functional annotation of genes at different levels, followed by calculation of relative abundance at functional and classification levels. Subsequently, various statistical analyses, including similarity clustering, grouping sorting, difference comparison, and visual display of the results, were performed.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism software (version 8) and the Majorbio platform were used for data analysis and graphing. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare the means between groups, and Tukey’s and Dunnett’s tests were used to compare the means between two groups. Differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Results

JWC alleviated gastric mucosal inflammation and modulated inflammatory cytokines

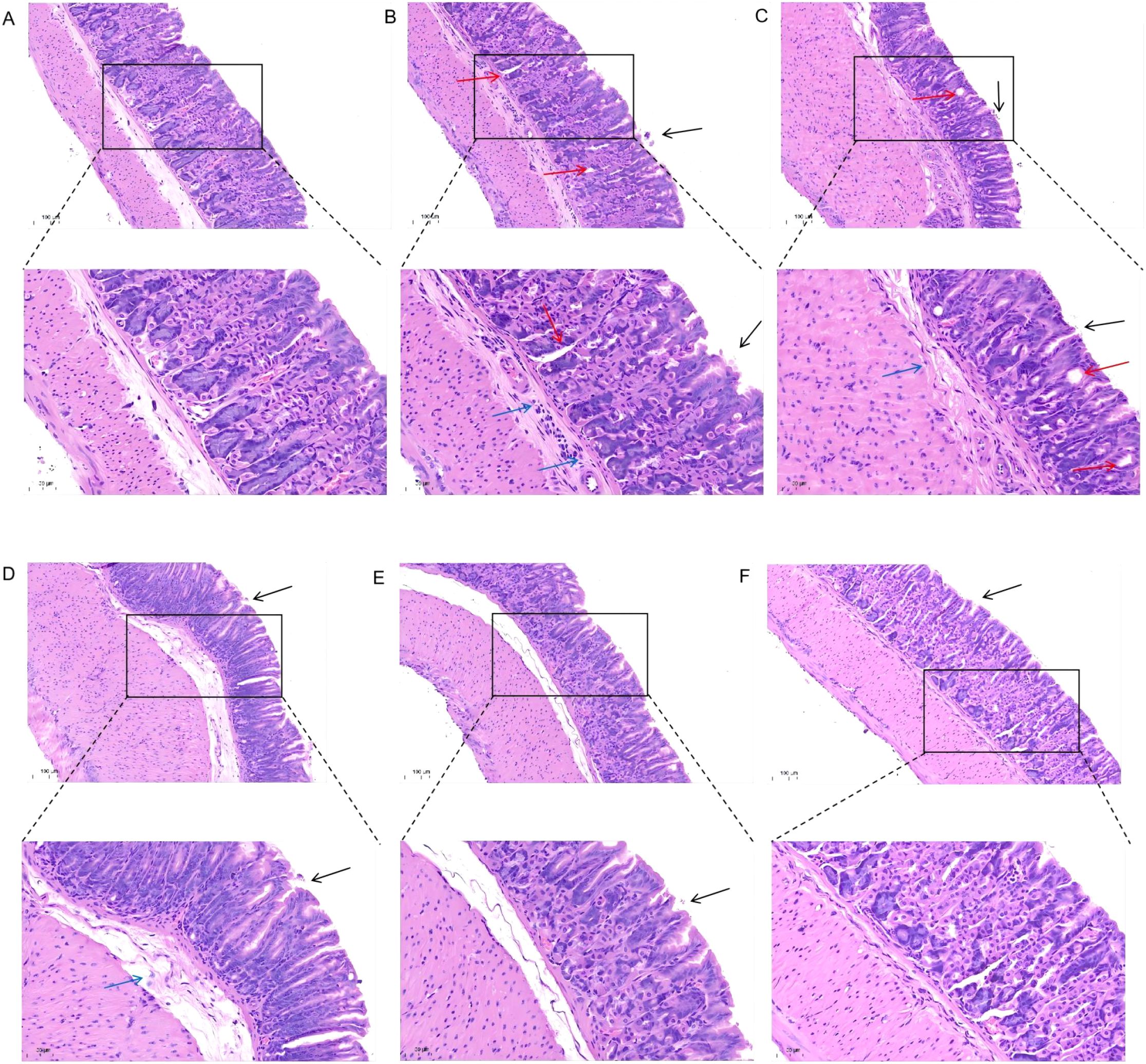

Following H. pylori infection, mice in the Model group exhibited slower weight gain compared to the Control group (Figure 1b). Successful colonization of H. pylori was confirmed by a positive RUT (Figure 1c) and visualization of bacteria via WS silver stain (Figure 1d). Histopathological examination revealed that H. pylori infection induced damage to the gastric mucosal epithelium and inflammatory cell infiltration. These pathological changes were markedly alleviated in the JWCM and JWCH groups, which showed relatively intact mucosal structures similar to the Control group (Figure 2).

Figure 2. H&E staining to observe the effect of JWC on gastric mucosal damage in mice. (A) Control group. (B) Model group. (C) AC triple group. (D) JWCL group. (E) JWCM group. (F) JWCH group. epithelial cell exfoliation (black arrows), mild dilation of gastric glands (red arrows), and inflammatory cell infiltration (blue arrows). (20× magnification, scale bar 100 µm; 40× magnification, scale bar 50 µm).

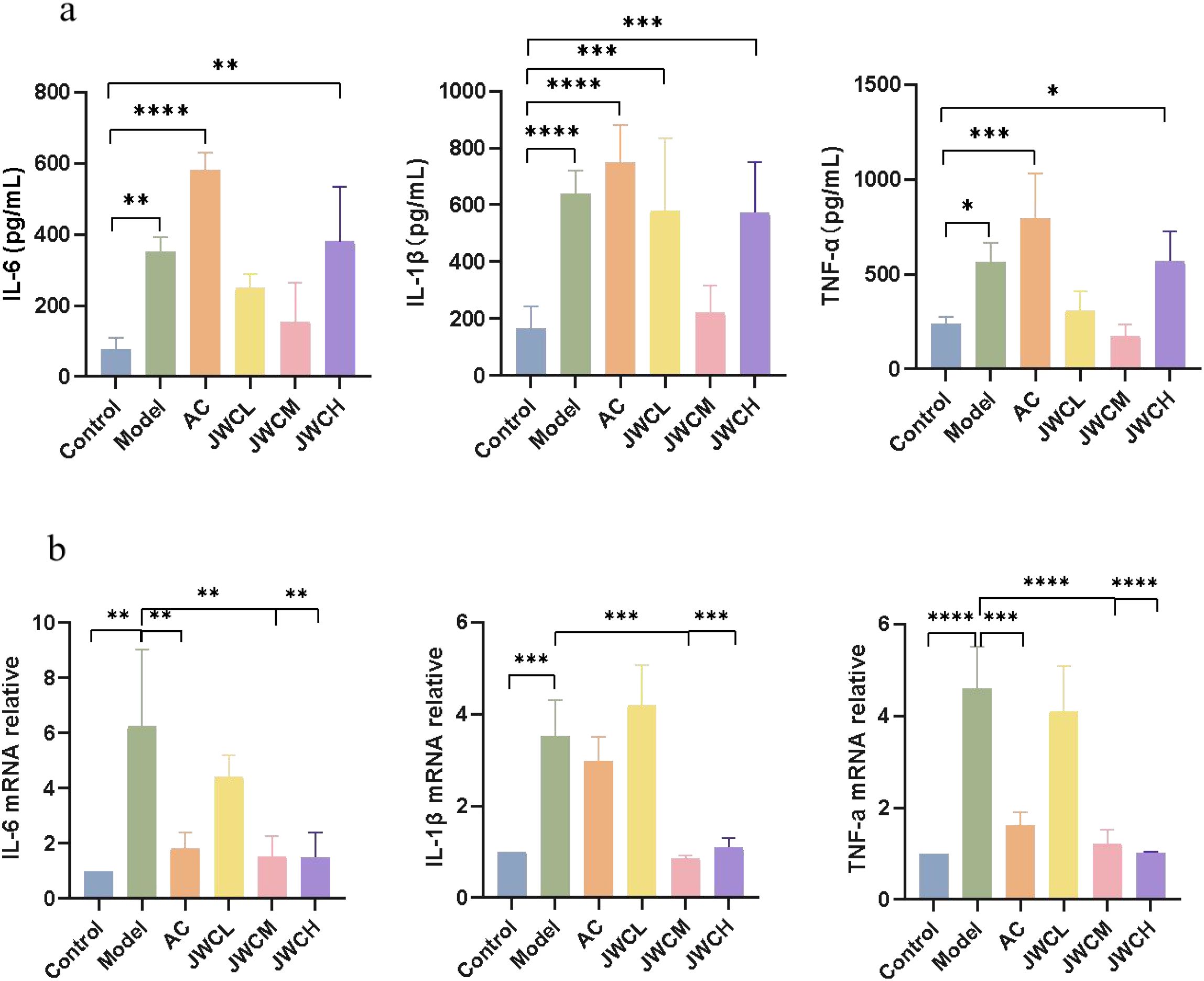

Consistent with the histopathological findings, H. pylori infection significantly increased the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α in gastric antral tissue supernatants. While the AC triple therapy group showed a continued increase in these cytokines, JWC treatment, particularly at medium and high doses, significantly downregulated their concentrations (Figure 3a). Similarly, qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that JWC treatment significantly reduced the mRNA expression levels of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α in the gastric mucosa (Figure 3b).

Figure 3. JWC regulated the expression of inflammation factors in gastric sinus tissues of (H) pylori infected mice. (a) The contents of IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α. (b) The mRNA expression level of IL-6, IL-1β and TNF -α. The results of each experiment are the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Analysis of gut microbial diversity and composition

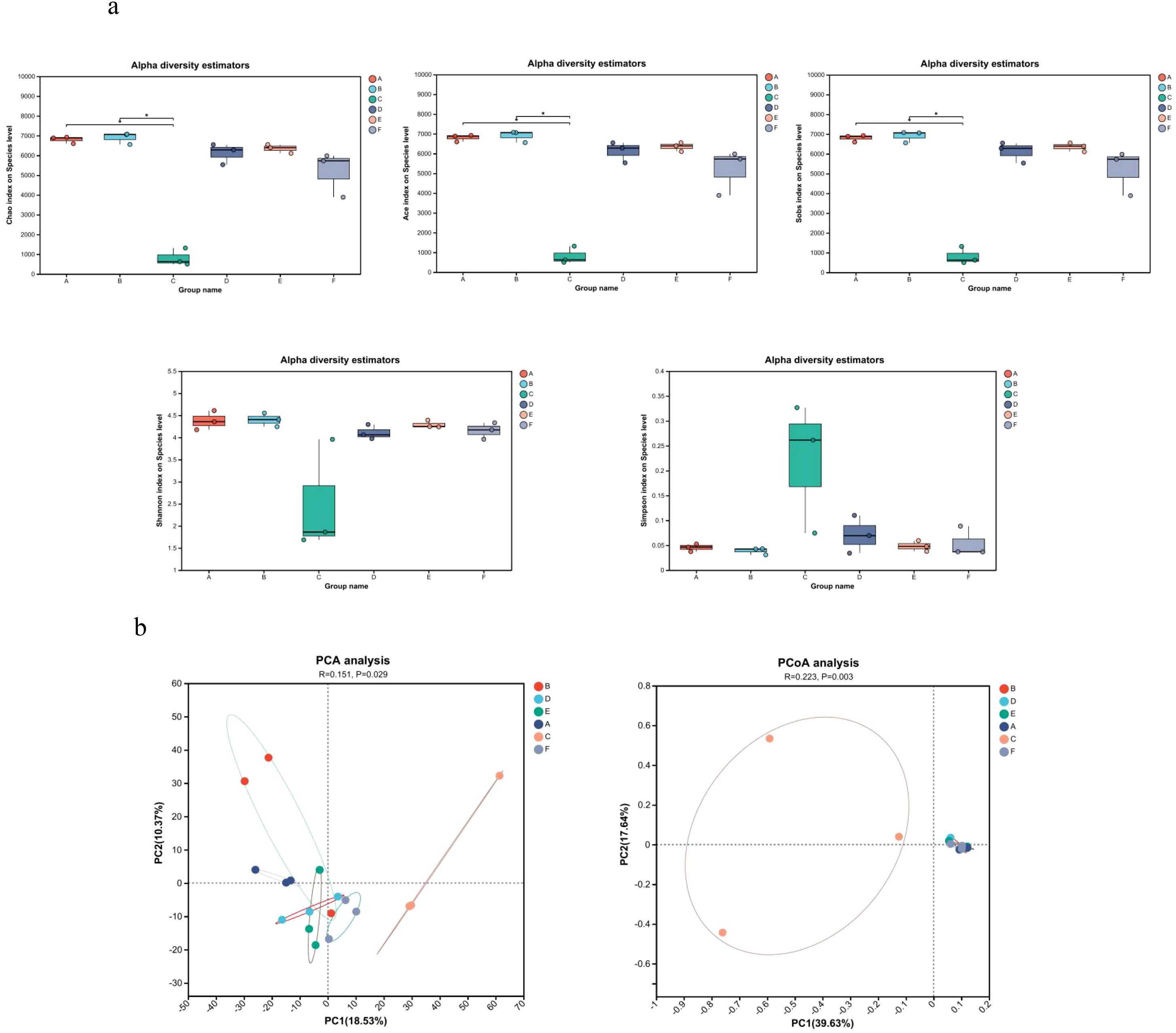

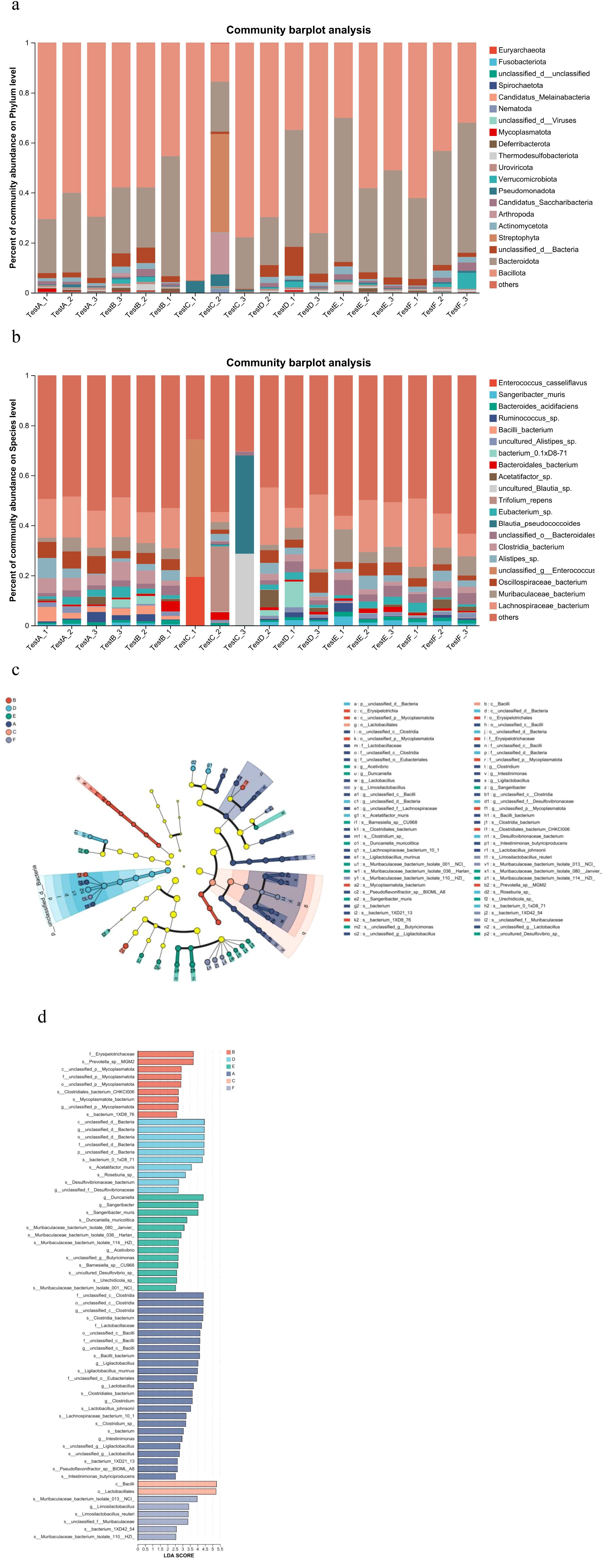

Analysis of α diversity, reflecting species richness and evenness, showed no significant differences between the Model and Control groups (Figure 4a). In contrast, the AC triple therapy group exhibited significantly reduced Chao, Ace, Sobs, and Shannon indices, alongside an elevated Simpson index, indicating markedly decreased microbial diversity. β diversity analysis, assessing inter-group compositional differences, revealed substantial separation of the AC triple group from others in PCA/PCoA plots, while JWC-treated groups clustered closely with Control group, suggesting minimal microbial community disruption (Figure 4b). Taxonomic analysis demonstrated pronounced dysbiosis in AC triple group. At the phylum level (Figure 5a), AC treatment led to drastic reduction in Bacteroidota (7% vs 14%) and Actinomycetota (1% vs 16%), with abnormal expansion of Streptophyta (99% vs 0), Pseudomonadota (61% vs 9%) and Arthropoda (92% vs 0). Species level analysis (Figure 5b) showed near disappearance of Lachnospiraceae_bacterium (2% vs 18%), Oscillospiraceae_bacterium (3% vs 28%), Muribaculaceae_bacterium (5% vs 14%), and Clostridia_bacterium (1% vs 31%), while opportunistic pathogens like Enterococcus and Blautia pseudococcoides proliferated extensively. The JWCM group exhibited a microbial profile characterized by an increased abundance of Bacteroidota (24% vs 14%) at the phylum level, while maintaining levels of Actinomycetota, Streptophyta, and Arthropoda comparable to Control group. Notably, Muribaculaceae_bacterium showed substantial enrichment (30% vs 14%), whereas Oscillospiraceae_bacterium (18% vs 28%) and Clostridia_bacterium (13% vs 31%) were reduced. The abundances of Lachnospiraceae_bacterium and Alistipes_sp remained similar to Control group.

Figure 4. Microbial diversity analysis. (a) Microbial α diversity analysis. Chao index difference analysis, Ace index difference analysis, Sobs index difference analysis, Shannon index difference analysis and Simpson index difference analysis. (b) Microbial β diversity analysis. PCA analysis and PCoA analysis. A, Control group; B, Model group; C, AC triple group; D, JWCL group; E, JWCM group; F, JWCH group. *P < 0.05.

Figure 5. Analysis of microbial composition and difference. (a) Relative abundance of microorganisms at the phylum level. X-axis: Sample names. The labels testA-1, testA-2, and testA-3 correspond to the individual samples in Group (A) Y-axis: Relative abundance of species. Each colored segment in the bar plot represents a different species, and its length denotes the proportion of that species in the sample. (b) Relative abundance of microorganisms at the species level. X-axis: Sample names. Y-axis: Relative abundance of species. Each colored segment in the bar plot represents a different species, and its length denotes the proportion of that species in the sample. (c) LEFSe multi-species hierarchical tree. Statistical analyses were performed only from the phylum to the species level. Nodes of different colors represented microbiomes significantly enriched in the corresponding group. The diameter of each circle was proportional to the abundance of the group. Yellow nodes indicated microbiomes that were not significantly different between groups. (d) LDA discrimination result map (LDA score>2.5). A, Control group; B, Model group; C, AC triple group; D, JWCL group; E, JWCM group; F, JWCH group.

Community structure analysis revealed group-specific microbial signatures through hierarchical clustering (Figure 5c) and LDA effect size discrimination (Figure 5d). Significant biomarker taxa were identified for each group: g:unclassified_c:Clostridia and f:Lactobacillaceae in Control group; g:unclassified_p:Mycoplasmatota in Model group; c:Bacilli and o:Lactobacillales in AC triple group; and Muribaculaceae_bacterium in JWC-treated groups.

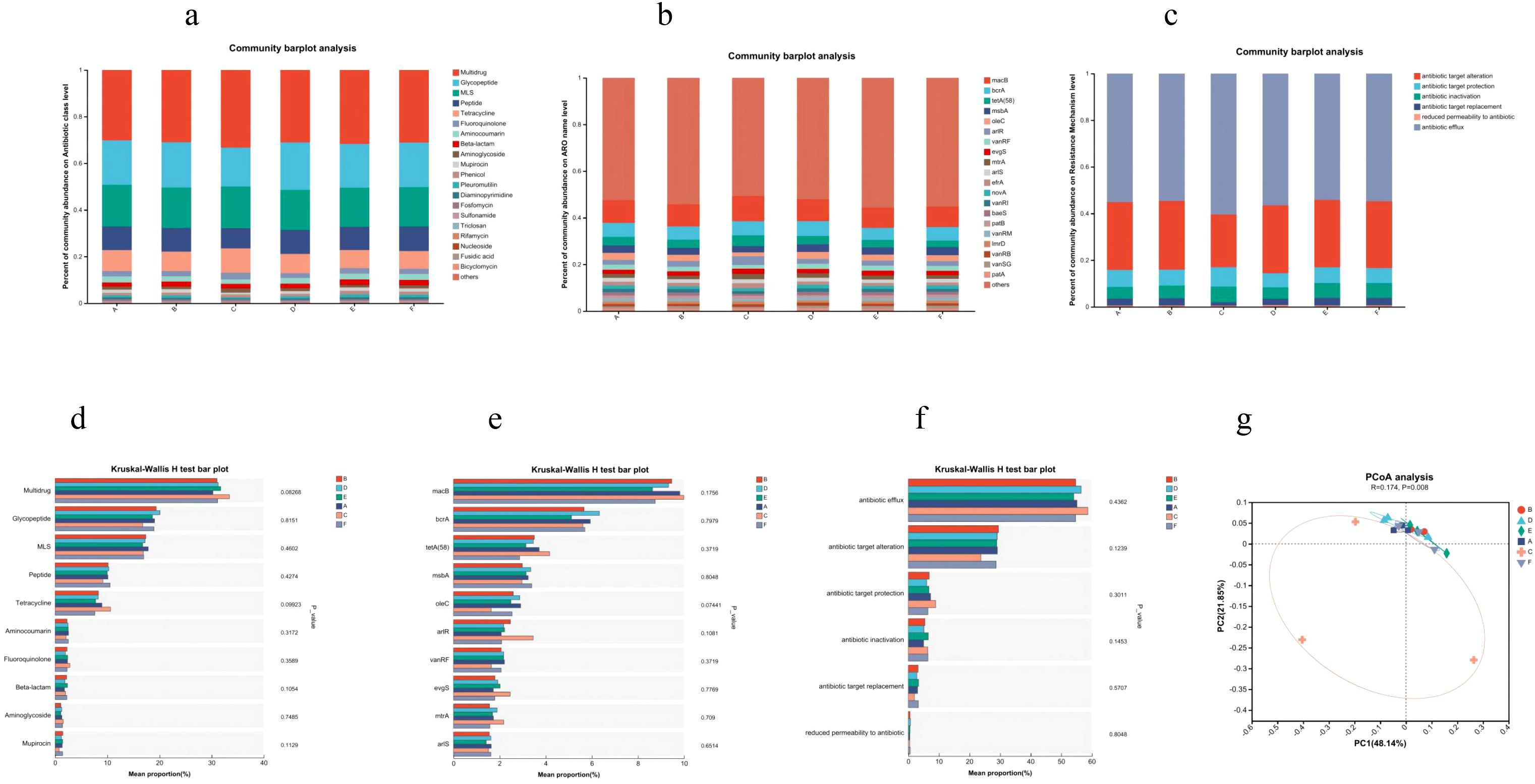

Analysis of antibiotic resistance genes

Principal coordinate analysis revealed significant separation of the AC triple therapy group from other groups in the resistome profile (Figure 6g). The AC triple group showed enrichment in antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) across multiple classes, including multidrug (18% vs 16%), tetracycline (20% vs 17%), fluoroquinolone (20% vs 17%), and aminoglycoside (23% vs 16%) resistance. Specifically, key ARGs such as macB (19% vs 17%), arlR (25% vs 14%), evgS (19% vs 15%), tetA(58) (22% vs 17%), and mtrA (22% vs 16%) were elevated (Figures 6a, b, d, e). Mechanistically, AC therapy increased genes encoding efflux pumps (18% vs 16%), antibiotic target protection (20% vs 17%), and antibiotic inactivation (19% vs 14%), while reducing those involved in target alteration (13% vs 17%) and replacement (9% vs 18%) (Figures 6c, f). In contrast, JWCM treatment downregulated tetracycline (15% vs 17%) and aminoglycoside (14% vs 16%) resistance levels, with specific suppression of macB, tetA(58), bcrA, oleC, and arlS genes. The overall ARG profile in JWCM group resembled that of Control group, demonstrating JWC’s capacity to restrict the expansion of the gut resistome.

Figure 6. CARD results. (a) Distribution of antibiotic classes in the top 20 of abundance. (b) Distribution of the top 20 AROs in abundance. (c) Distribution of major resistance mechanisms. (d) Antibiotic class analysis of variance. (e) ARO Difference analysis. (f) Resistance mechanism difference analysis. (g) PCoA analysis. A, Control group; B, Model group; C, AC triple group; D, JWCL group; E, JWCM group; F, JWCH group.

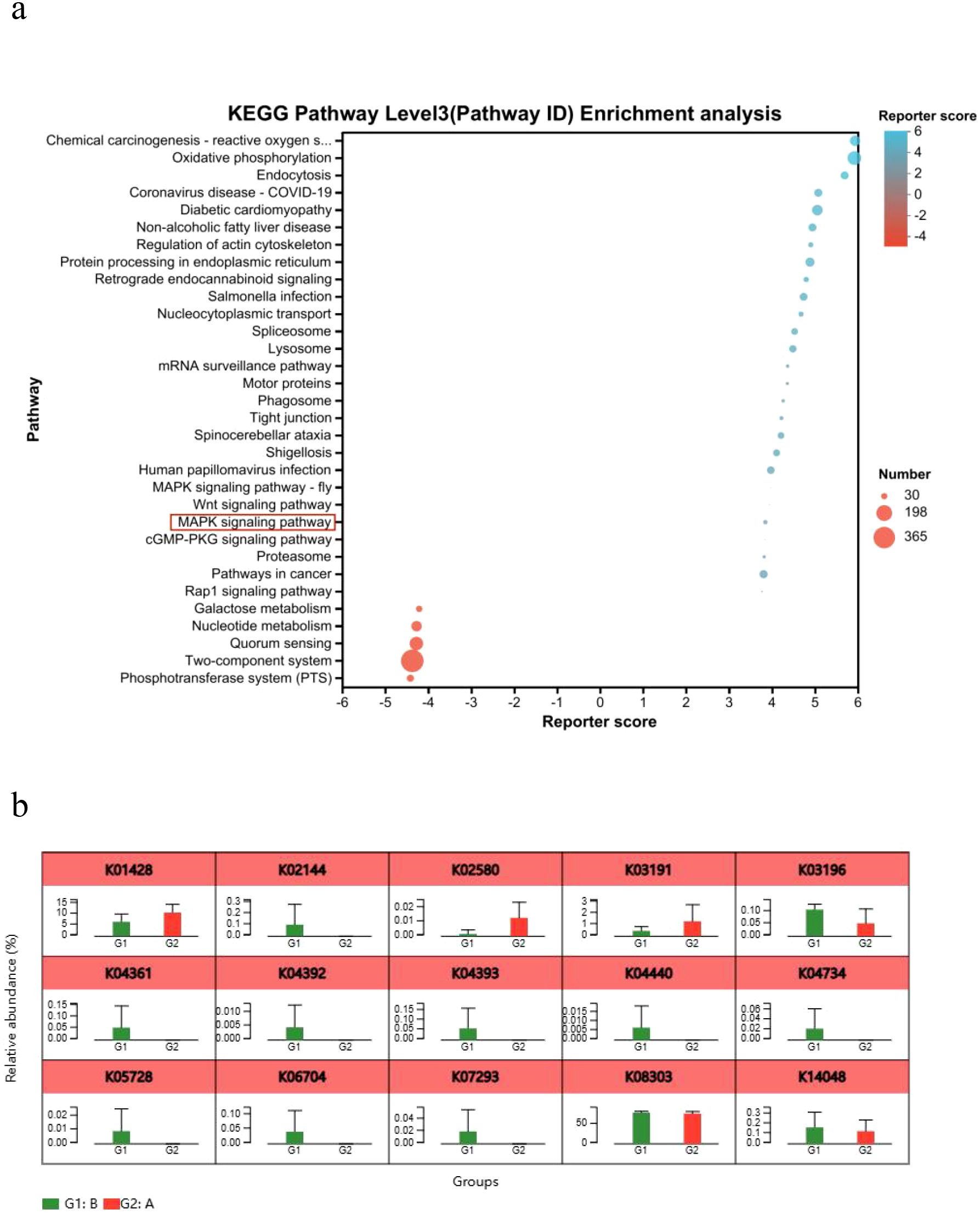

KEGG pathway enrichment and MAPK pathway activation

KEGG analysis revealed significant enrichment of the MAPK signaling pathway in the Model group compared to Controls (Figure 7a). Consistent with this, key genes (K04361, K06704, K07293, K05728) involved in epithelial cell signaling during H. pylori infection were upregulated (Figure 7b), confirming MAPK pathway activation.

Figure 7. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. (a) Bubble plot of KEGG functional enrichment analysis. (b) Analysis of relative gene abundance of key enzymes in the epithelial cell signaling pathway in H. pylori infection. A, Control group; B, Model group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

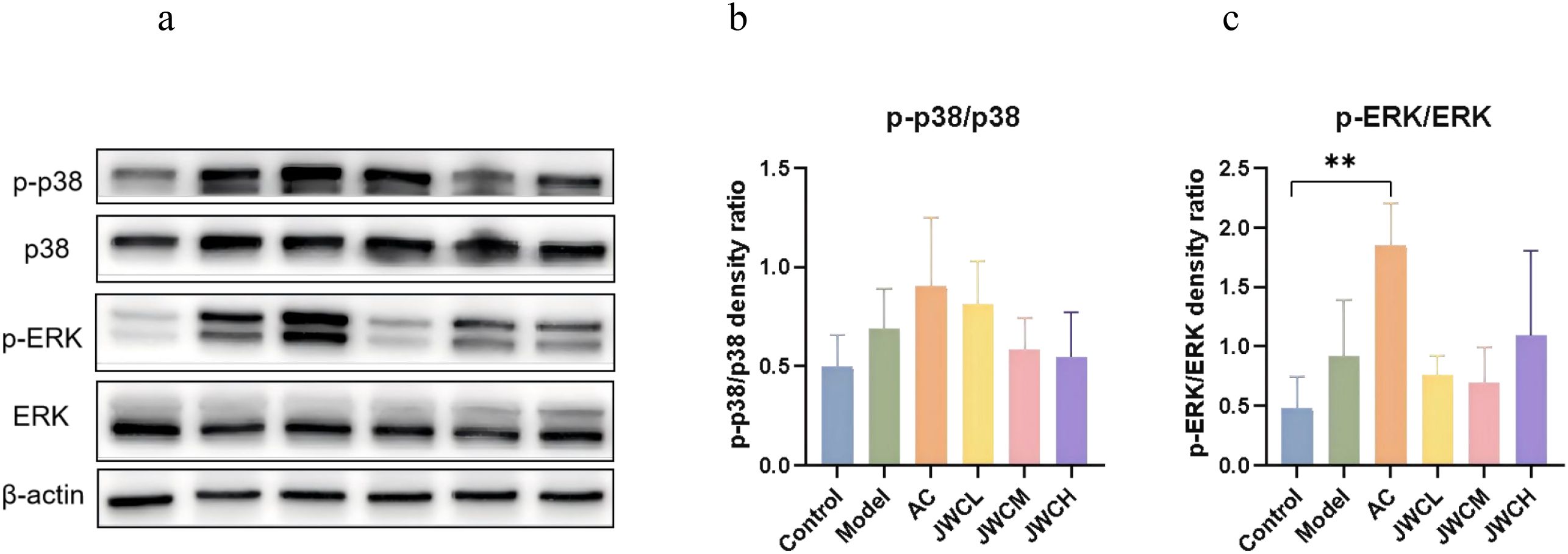

At the protein level, phosphorylation of ERK and p38 was elevated in infected mice. While AC triple therapy sustained this activation, JWC treatment significantly suppressed both p-ERK and p-p38 expression (Figure 8), indicating direct modulation of the MAPK pathway.

Figure 8. JWC regulated the expressions of MAPK pathway proteins in (H) pylori-infected mice. (a) WB detection of p38, p-p38, ERK, p-ERK expression. (b) Relative expression of p-p38/p38. (c) Relative expression of p-ERK/ERK. Results of each experiment are the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Discussion

H. pylori establishes persistent colonization in the gastric epithelium, leading to chronic inflammation that can progress to peptic ulcers and gastric cancer (Kumar et al., 2021). This study demonstrates that JWC effectively alleviates H. pylori-induced gastric inflammation in mice. Its mechanism appears to be multi-faceted, involving the preservation of intestinal microbial ecology, mitigation of antibiotic resistance gene enrichment, and modulation of the host MAPK signaling pathway, offering a contrasting profile to the ecological drawbacks of conventional triple therapy.

Compared to the Control group, mice in the Model group exhibited a slower increase in body weight following intraperitoneal injection of cyclophosphamide and H. pylori. On days 7 and 14 of modeling, the body weights of mice in the Model group were lower than that of the control group, indicating that H. pylori infection can impede mouse growth rate (Figure 1b). A meta-analysis demonstrated that eradication of H. pylori is associated with an increase in body weight and mass index (Upala et al., 2017). The body weight of H. pylori-infected mice was also lower in animal experiments (Noh et al., 2017), potentially indicating an association between H. pylori and alterations in body metabolism.

Our findings confirm that JWC significantly mitigates gastric mucosal damage and reduces the levels of key pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α. A notable observation was that while the AC triple therapy effectively eradicated the pathogen, it failed to significantly reduce IL-1β levels. This phenomenon may be attributed to several factors. First, antibiotics can induce gastrointestinal discomfort and transient mucosal stress, potentially perpetuating local inflammatory cytokine release even during pathogen clearance (Zhao et al., 2021). Second, as our metagenomic sequencing revealed, AC therapy caused severe gut dysbiosis, characterized by a loss of diversity and an expansion of opportunistic pathogens like Enterococcus. Such dysbiosis can adversely modulate the host immune system, potentially sustaining the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Ye et al., 2020; Nabavi-Rad et al., 2022). Third, and perhaps most critically, the AC regimen did not significantly inhibit the activation of the MAPK signaling pathway, a key regulator of IL-1β synthesis. In contrast, JWC treatment effectively suppressed this pathway, providing a plausible mechanism for its superior control of this specific cytokine.

Consistent with previous reports (Iino et al., 2020; Cui et al., 2022), H. pylori was undetectable in the intestinal microbiota of infected mice, indicating a lack of bacterial translocation from the stomach. This supports the notion that H. pylori influences the gut ecosystem indirectly—likely through host immune modulation or gastric environmental changes (Chen et al., 2021). While some studies report variable effects of H. pylori on gut microbial diversity (Kienesberger et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2021), we observed no significant alteration in α- or β-diversity in KM mice, possibly due to the short infection duration and low gastric colonization density observed histologically. In contrast, AC triple therapy markedly reduced both α diversity and β diversity, aligning with known antibiotic-induced microbial depletion (Du et al., 2024). Notably, JWC treatment preserved intestinal microbial structure and composition, showing no significant divergence from the Control and Model groups. This suggests that JWC exerts minimal disruptive effects on the gut microbiota while alleviating gastric inflammation.

The focus on intestinal microbiota rather than gastric microbiota was deliberate, as the gut serves as a primary site for antibiotic resistance development and systemic immune regulation. Furthermore, the low bacterial biomass of the murine stomach poses technical challenges for metagenomic analysis. Gastric infection and inflammation were robustly assessed via histopathology and cytokine profiling. Future study incorporating concurrent gastric microbial analysis would provide a more comprehensive perspective (Wang C. et al., 2023).

Muribaculaceae and Alistipes_sp, belonging to Bacteroidota, metabolize propionic acid. Oscillospiraceae_bacterium, Lachnospiraceae_bacterium, and Clostridia_bacterium are primary butyric acid producers. These short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) serve as the main energy source for colonic epithelial cells and help lower intestinal pH, inhibiting pathogens, promoting probiotics, and enhancing nutrient absorption (Agus et al., 2021). SCFAs also protect the intestinal mucosal barrier and exhibit anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, and immune-regulatory functions (Dalile et al., 2019). In contrast, Enterococcus, an opportunistic pathogen tolerant to salt and acid, often shows β-lactam resistance due to its weak-binding penicillin-binding proteins (Torres et al., 2018). A meta-analysis revealed that in the short-term follow-up period post-eradication, the abundance of Enterobacteriaceae and Enterococcus at the genus level increased (Ye et al., 2020). The AC triple therapy profoundly diminished gut microbiota diversity and richness, drastically altering its composition by depleting beneficial SCFAs and promoting opportunistic pathogens. In contrast, JWC treatment preserved microbial diversity and promoted a beneficial compositional shift, notably increasing the abundance of Muribaculaceae, a bacterium associated with anti-inflammatory properties. Recent evidence suggests that dietary components profoundly influence gut microbial composition and function (Liu et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2025). The plant-derived ingredients in JWC may mimic dietary fibers or polyphenols, thereby promoting the growth of SCFA-producing bacteria and helping to counteract antibiotic-induced dysbiosis by supporting a resilient microbial network. While we did not directly measure SCFAs levels, the observed structural changes are consistent with a shift towards a more favorable microbial state.

A significant increase in antibiotic resistance genes was observed following the completion of bismuth quadruple therapy for H. pylori eradication, consisting of amoxicillin, clarithromycin, bismuth, and esomeprazole (Abdulkhakov et al., 2024). The genes were primarily associated with resistance to β-lactam antibiotics, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, and glycopeptides. Concomitant with its impact on microbiota composition, AC therapy elevated the abundance of a broad spectrum of antibiotic resistance genes in the gut resistome in our study. This enrichment suggests that antibiotic pressure can selectively favor resistant commensals, potentially augmenting the reservoir for horizontal gene transfer (Malfertheiner et al., 2017; Liou et al., 2023). However, JWC downregulated these resistance genes. It is critical to distinguish this gut resistome from pathogen-specific resistance. Our study didn’t characterize the primary resistance mechanisms within the H. pylori strains themselves, such as clarithromycin resistance (23S rRNA mutations) or metronidazole resistance (rdxA mutations), which are key drivers of clinical eradication failure (Iqbal et al., 2024). Therefore, elucidating the comprehensive impact of JWC on antimicrobial resistance represents a critical future research direction.

H. pylori infection activates the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway, initiating downstream ERK signaling (Du et al., 2007). This process involves the upregulation of epidermal growth factor (EGF) and ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 (ADAM10), which disrupts the shedding of heparin-binding EGF (HB-EGF), leading to EGFR transactivation (Keates et al., 2001). Furthermore, the bacterial cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) protein is translocated into host cells via the type IV secretion system, where it binds to and enhances the phosphatase activity of SHP2 in a phosphorylation-dependent manner, thereby activating both RAS-dependent and independent MAPK cascades (Maroun et al., 2000; Schaeper et al., 2000). Although transcriptional upregulation of EGFR, ADAM10, and SHP2 genes in the Model group was not statistically significant, metagenomic analysis confirmed significant enrichment of the MAPK pathway, accompanied by increased phosphorylation of ERK and p38. This indicates that H. pylori infection triggers a cascade within the MAPK signaling pathway. This indicates that H. pylori infection triggers a cascade within the MAPK signaling pathway, which is consistent with previous reports (Keates et al., 1999; Slomiany and Slomiany, 2001; Slomiany and Slomiany, 2002).

The MAPK pathway, comprising ERKs, JNKs and p38, is crucial for regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, and inflammatory responses (Morrison, 2012). Our findings demonstrate that JWC treatment significantly inhibits the phosphorylation of p38 and ERK. This suppression of MAPK activation likely represents a key mechanism by which JWC mitigates gastric mucosal inflammation. In contrast, AC triple therapy showed no significant effect on this pathway. The anti-inflammatory effects of JWC appear to operate primarily through these host-directed pathways rather than solely via direct bactericidal activity. It should be noted that this study did not evaluate the direct antibacterial effect of JWC. Future research should quantify the gastric H. pylori load through CFU counts to provide a more direct and precise measure of JWC’s antibacterial efficacy.

Beyond therapeutic development, the field of H. pylori management is also advancing in diagnostics. Techniques such as Linked Color Imaging and Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy now enable precise detection and real-time, cellular-level visualization of H. pylori gastritis, with some methods allowing objective quantification of mucosal inflammation (Sun et al., 2023). Although these tools remain limited by cost and technical demands, they offer promising avenues for translational research. Future clinical studies on JWC could leverage such non-invasive imaging to quantitatively monitor gastritis resolution, providing a synergistic approach to treatment evaluation.

Conclusion

In contrast to AC triple therapy which induces gut dysbiosis and expands the antibiotic resistome, JWC effectively ameliorates gastric inflammation while preserving intestinal microbial diversity and richness, reducing the abundance of antibiotic resistance genes, and suppressing MAPK signaling pathway activation.

We acknowledge the limitations of our current study. Future study should: first, quantitatively evaluate JWC’s direct antibacterial efficacy through CFU counting to strengthen the evidence of its antimicrobial activity; second, perform functional analysis of microbial metabolites, particularly SCFAs, to validate the physiological relevance of the observed microbiota shifts; and third, identify the precise molecular targets of JWC within the MAPK pathway to elucidate its mechanism of action.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital (Approval number: J202122). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

YY: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Data curation. X-FJ: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. G-HC: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Formal analysis. Q-YH: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Project administration. M-ML: Software, Writing – review & editing. Z-MS: Software, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. HY: Formal analysis, Project administration, Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Software. X-ZZ: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by General Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 81973615, No: 81803910), National Natural Science Foundation of China Youth Program (No: 82405061), National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (Scientific Research Seed Fund of Peking University First Hospital) (No: 2024SF87), Plan for the Construction of Innovative Teams in Traditional Chinese Medicine of the Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Shanxi Province (No: zyytd2024030) and Key Laboratory Construction Project of Shanxi Province (No: zyyyjs2024026).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Department of Gastroenterology at Peking University First Hospital for generously providing the H. pylori strains.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2025.1628594/full#supplementary-material

References

Abdulkhakov, S., Markelova, M., Safina, D., Siniagina, M., Khusnutdinova, D., Abdulkhakov, R., et al. (2024). Butyric acid supplementation reduces changes in the taxonomic and functional composition of gut microbiota caused by H. pylori Eradication Ther. Microorganisms. 12, 319. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12020319

Agus, A., Clément, K., and Sokol, H. (2021). Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as central regulators in metabolic disorders. Gut 70, 1174–1182. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323071

Akimoto, N., Ugai, T., Zhong, R., Hamada, T., Fujiyoshi, K., Giannakis, M., et al. (2021). Rising incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer - a call to action. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18, 230–243. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-00445-1

Chen, C. C., Liou, J. M., Lee, Y. C., Hong, T. C., El-Omar, E. M., and Wu, M. S. (2021). The interplay between Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes 13, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1909459

Chu, Y. M., Wang, T. X., Jia, X. F., Yang, Y., Shi, Z. M., Cui, G. H., et al. (2022). Fuzheng Nizeng Decoction regulated ferroptosis and endoplasmic reticulum stress in the treatment of gastric precancerous lesions: A mechanistic study based on metabolomics coupled with transcriptomics. Front. Pharmacol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1066244

Cox, L. M. and Blaser, M. J. (2015). Antibiotics in early life and obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 11, 182–190. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.210

Cui, M. Y., Cui, Z. Y., Zhao, M. Q., Zhang, M. J., Jiang, Q. L., Wang, J. J., et al. (2022). The impact of Helicobacter pylori infection and eradication therapy containing minocycline and metronidazole on intestinal microbiota. BMC Microbiol. 22, 321. doi: 10.1186/s12866-022-02732-6

Dalile, B., Van Oudenhove, L., Vervliet, B., and Verbeke, K. (2019). The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 461–478. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0157-3

Du, L., Chen, B., Cheng, F., Kim, J., and Kim, J. J. (2024). Effects of helicobacter pylori therapy on gut microbiota: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Dis. 42, 102–112. doi: 10.1159/000527047

Du, Y., Danjo, K., Robinson, P. A., and Crabtree, J. E. (2007). In-Cell Western analysis of Helicobacter pylori-induced phosphorylation of extracellular-signal related kinase via the transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Microbes Infect. 9, 838–846. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.03.004

Gong, H., Zhao, N., Zhu, C., Luo, L., and Liu, S. (2024). Treatment of gastric ulcer, traditional Chinese medicine may be a better choice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 324, 117793. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2024.117793

Helicobacter pylori Group CSoG and Zhou, L. Y. (2022). Sixth chinese national consensus report on management of helicobacter pylori infection(Treatment excluded). Chin. J. Gastroenterol. 27, 289–304. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-7125.2022.05.006

Helicobacter pylori Study Group (2022). Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, Chinese Medical Association. 2022 Chinese national clinical practice guideline on Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment. Chin. J. Dig 42, 745–756. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn311367-20220929-00479

Herzlinger, M., Dannheim, K., Riaz, M., Liu, E., Bousvaros, A., and Bonilla, S. (2023). Helicobacter pylori antimicrobial resistance in a pediatric population from the new england region of the United States. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21, 3458–3460.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.02.026

Hong, T. C., El-Omar, E. M., Kuo, Y. T., Wu, J. Y., Chen, M. J., Chen, C. C., et al. (2024). Asian Pacific Alliance on Helicobacter and Microbiota. Primary antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori in the Asia-Pacific region between 1990 and 2022: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9, 56–67. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00281-9

Hooi, J. K. Y., Lai, W. Y., Ng, W. K., Suen, M. M. Y., Underwood, F. E., Tanyingoh, D., et al. (2017). Global prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 153, 420–429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.022

Iino, C., Shimoyama, T., Chinda, D., Sakuraba, H., Fukuda, S., and Nakaji, S. (2020). Influence of helicobacter pylori infection and atrophic gastritis on the gut microbiota in a Japanese population. Digestion 101, 422–432. doi: 10.1159/000500634

Iqbal, S., Ullah, W., Shah, S. F., Gul, A., and Basit, A. (2024). Characterization of metronidazole, clarithromycin and amoxicillin resistance genes in helicobacter pylori isolated from gastroenteritis patients. Discov. Med. 36, 1848–1857. doi: 10.24976/Discov.Med.202436188.171

Johnson, S., Samore, M. H., Farrow, K. A., Killgore, G. E., Tenover, F. C., Lyras, D., et al. (1999). Epidemics of diarrhea caused by a clindamycin-resistant strain of Clostridium difficile in four hospitals. N Engl. J. Med. 341, 1645–1651. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911253412203

Keates, S., Keates, A. C., Warny, M., Peek, R. M., Jr, Murray, P. G., and Kelly, C. P. (1999). Differential activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in AGS gastric epithelial cells by cag+ and cag- Helicobacter pylori. J. Immunol. 163, 5552–5559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.163.10.5552

Keates, S., Sougioultzis, S., Keates, A. C., Zhao, D., Peek, R. M., Jr, Shaw, L. M., et al. (2001). cag+ Helicobacter pylori induce transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor in AGS gastric epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 48127–48134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107630200

Kienesberger, S., Cox, L. M., Livanos, A., Zhang, X. S., Chung, J., Perez-Perez, G. I., et al. (2016). Gastric helicobacter pylori infection affects local and distant microbial populations and host responses. Cell Rep. 14, 1395–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.017

Kumar, S., Patel, G. K., and Ghoshal, U. C. (2021). Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation: possible factors modulating the risk of gastric cancer. Pathogens 10, 1099. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10091099

Lin, M. M., Yang, S. S., Huang, Q. Y., Cui, G. H., Jia, X. F., Yang, Y., et al. (2024). Effect and mechanism of Qingre Huashi decoction on drug-resistant Helicobacter pylori. World J. Gastroenterol. 30, 3086–3105. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i24.3086

Liou, J. M., Jiang, X. T., Chen, C. C., Luo, J. C., Bair, M. J., Chen, P. Y., et al. (2023). Second-line levofloxacin-based quadruple therapy versus bismuth-based quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication and long-term changes to the gut microbiota and antibiotic resistome: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8, 228–241. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00384-3

Liou, J. M., Lee, Y. C., El-Omar, E. M., and Wu, M. S. (2019). Efficacy and long-term safety of H. pylori eradication for gastric cancer prevention. Cancers (Basel). 11, 593. doi: 10.3390/cancers11050593

Liou, J. M., Lee, Y. C., and Wu, M. S. (2020). Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection and its long-term impacts on gut microbiota. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 35, 1107–1116. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14992

Liu, Y. (2014). Effects and mechanism of Jinghua Weikang capsule and its decoction on drug-resistant Helicobacter pylori (Beijing: Beijing University of Chinese Medicine).

Liu, S., Wang, K., Lin, S., Zhang, Z., Cheng, M., Hu, S., et al. (2023). Comparison of the effects between tannins extracted from different natural plants on growth performance, antioxidant capacity, immunity, and intestinal flora of broiler chickens. Antioxidants (Basel). 12, 441. doi: 10.3390/antiox12020441

Lynch, J. P., III and Martinez, F. J. (2002). Clinical relevance of macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae for community-acquired pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34 Suppl 1, S27–S46. doi: 10.1086/324527

Malfertheiner, P., Megraud, F., O’Morain, C. A., Gisbert, J. P., Kuipers, E. J., Axon, A. T., et al. (2017). Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut 66, 6–30. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312288

Maroun, C. R., Naujokas, M. A., Holgado-Madruga, M., Wong, A. J., and Park, M. (2000). The tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 is required for sustained activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and epithelial morphogenesis downstream from the met receptor tyrosine kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 8513–8525. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.22.8513-8525.2000

Morrison, D. K. (2012). MAP kinase pathways. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a011254. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011254

Nabavi-Rad, A., Sadeghi, A., Asadzadeh Aghdaei, H., Yadegar, A., Smith, S. M., and Zali, M. R. (2022). The double-edged sword of probiotic supplementation on gut microbiota structure in Helicobacter pylori management. Gut Microbes 14, 2108655. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2022.2108655

Nguyen, L. H., Örtqvist, A. K., Cao, Y., Simon, T. G., Roelstraete, B., Song, M., et al. (2020). Antibiotic use and the development of inflammatory bowel disease: a national case-control study in Sweden. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5, 986–995. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30267-3

Noh, H. J., Koh, H. B., Kim, H. K., Cho, H. H., and Lee, J. (2017). Anti-bacterial effects of enzymatically-isolated sialic acid from glycomacropeptide in a Helicobacter pylori-infected murine model. Nutr. Res. Pract. 11, 11–16. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2017.11.1.11

Okimoto, T., Ando, T., Sasaki, M., Ono, S., Kobayashi, I., Shibayama, K., et al. (2024). Antimicrobial-resistant Helicobacter pylori in Japan: Report of nationwide surveillance for 2018-2020. Helicobacter 29, e13028. doi: 10.1111/hel.13028

Qu, L., Liu, C., Ke, C., Zhan, X., Li, L., Xu, H., et al. (2022). Atractylodes lancea rhizoma attenuates DSS-induced colitis by regulating intestinal flora and metabolites. Am. J. Chin. Med. 50, 525–552. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X22500203

Schaeper, U., Gehring, N. H., Fuchs, K. P., Sachs, M., Kempkes, B., and Birchmeier, W. (2000). Coupling of Gab1 to c-Met, Grb2, and Shp2 mediates biological responses. J. Cell Biol. 149, 1419–1432. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1419

Slomiany, B. L. and Slomiany, A. (2001). Role of ERK and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in gastric mucosal inflammatory responses to Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide. IUBMB Life. 51, 315–320. doi: 10.1080/152165401317190833

Slomiany, B. L. and Slomiany, A. (2002). Disruption in gastric mucin synthesis by Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide involves ERK and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase participation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 294, 220–224. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00463-1

Sun, X. T., Ma, C. Y., Zhang, X. T., Lu, C., Yu, H. Y., Zhang, W., et al. (2023). Linked color imaging and color analytic model based on pixel brightness for diagnosing H. Pylori infection in gastric antrum. Eurasian J. Med. Oncol. 7, 160–164. doi: 10.14744/ejmo.2023.33713

Torres, C., Alonso, C. A., Ruiz-Ripa, L., León-Sampedro, R., Del Campo, R., and Coque, T. M. (2018). Antimicrobial Resistance in Enterococcus spp. of animal origin. Microbiol. Spectr. 6 (4), 10.1128. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.ARBA-0032-2018

Upala, S., Sanguankeo, A., Saleem, S. A., and Jaruvongvanich, V. (2017). Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on insulin resistance and metabolic parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 29, 153–159. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000774

Wang, Y., Du, J., Zhang, D., Jin, C., Chen, J., Wang, Z., et al. (2023). Primary antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob Antimicrob. Resist. 34, 30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2023.05.014

Wang, C., Jiang, S., Zheng, H., An, Y., Zheng, W., Zhang, J., et al. (2024). Integration of gut microbiome and serum metabolome revealed the effect of Qing-Wei-Zhi-Tong Micro-pills on gastric ulcer in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 319, 117294. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2023.117294

Wang, C., Yu, X., Lin, H., Wang, G., Liu, J., Gao, C., et al. (2023). Integrating microbiome and metabolome revealed microbe-metabolism interactions in the stomach of patients with different severity of peptic ulcer disease. Front. Immunol. 14. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1134369

Wang, T. T., Zhang, Y. M., Zhang, X. Z., Cheng, H., Hu, F. L., Han, H. X., et al. (2013). Jinghuaweikang gelatin pearls plus proton pump inhibitor-based triple regimen in the treatment otchronic atrophic gastritis with Helicobacter pylori infection: a multicenter. randomized, controlled clinical study. Natl. Med. J. China. 93, 3491–3495. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2013.44.002

Xu, W., Yang, B., Lin, L., Lin, Q., Wang, H., Yang, L., et al. (2024). Antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Chinese children: A multicenter study from 2016 to 2023. Helicobacter 29, e13038. doi: 10.1111/hel.13038

Yang, A., Ye, Y., Liu, Q., Xu, J., Li, R., Xu, M., et al. (2025). Response of nutritional values and gut microbiomes to dietary intake of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in tenebrio molitor larvae. Insects 16, 970. doi: 10.3390/insects16090970

Ye, H., Li, N., Yu, J., Zhang, X. Z., and Cheng, H. (2015). The establishment of animal model by Helicobacter pylori infected Kunming mice. Chin. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 24, 3. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-5709.2015.03.013

Ye, Q., Shao, X., Shen, R., Chen, D., and Shen, J. (2020). Changes in the human gut microbiota composition caused by Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter 25, e12713. doi: 10.1111/hel.12713

Zhang, Y. M., Wang, T. T., Ye, H., Zhang, X. Z., Cheng, H., Li, J. X., et al. (2013). Jinghuaweikang Capsules combined with triple therapy in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori associated gastritis: a multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical study. Chin. J. Integrated Traditional Western Med. Digestion. 21, 587–590. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-038X.2013.11.008

Zhang, E. E., Ye, H., Jia, X. F., Huang, Q. Y., Zhang, X. Z., and Liu, Y. (2020). Effect of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. @ on Biofilm Formation of Helicobacter pylori in Vitro. Chin. J. Integrated Traditional Western Med. 40, 1241–1245. doi: 10.7661/j.cjim.20200904.334

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori infection, inflammation, drug resistance genes, intestinal microbiota, metagenomic sequencing

Citation: Yang Y, Jia X-F, Cui G-H, Huang Q-Y, Lin M-M, Shi Z-M, Ye H and Zhang X-Z (2025) Jinghuaweikang capsule alleviates Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric mucosal inflammation and drug resistance by regulating intestinal microbiota and MAPK pathway. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 15:1628594. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2025.1628594

Received: 14 May 2025; Accepted: 11 November 2025; Revised: 07 November 2025;

Published: 28 November 2025.

Edited by:

Imran Khan, Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan, PakistanReviewed by:

Raees Khan, National University of Medical Sciences (NUMS), PakistanChao Wang, Shandong Tumor Hospital, China

Arghyadeep Bhattacharjee, Kingston College of Science, India

Copyright © 2025 Yang, Jia, Cui, Huang, Lin, Shi, Ye and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hui Ye, YnJpZ2h0bGVhZjcyM0AxNjMuY29t; Xue-Zhi Zhang, emhhbmcueHVlemhpQDI2My5uZXQ=

†These authors share first authorship

Yao Yang

Yao Yang Xiao-Fen Jia

Xiao-Fen Jia Guang-Hui Cui

Guang-Hui Cui Qiu-Yue Huang

Qiu-Yue Huang Miao-Miao Lin

Miao-Miao Lin Zong-Ming Shi

Zong-Ming Shi Hui Ye

Hui Ye Xue-Zhi Zhang

Xue-Zhi Zhang