- 1State Key Laboratory of Microbial Technology, Microbial Technology Institute, Shandong University, Qingdao, China

- 2School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Shandong University, Qingdao, China

- 3Qilu Hospital Qingdao, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Qingdao, China

- 4Shanghai Key Laboratory of Atmospheric Particle Pollution and Prevention (LAP), Shanghai, China

The rise of antibiotic-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae poses a significant global health threat. Plasmids, as mobile genetic elements, play a critical role in bacterial adaptation by facilitating the spread of resistance genes. To analyze plasmid-mediated antibiotic and heavy metal resistance in clinical Klebsiella strains, 33 Klebsiella strains isolated from wastewater were subjected to third-generation nanopore sequencing to obtain high-quality whole-genome assemblies. The presence and diversity of plasmids associated with antibiotic and heavy metal resistance were analyzed, and phenotypic assays were conducted to confirm metal resistance. A total of 81 plasmids were identified across 24 strains, including 28 (34.6%) novel plasmids. Among them, 22 plasmids carried antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), with 12 containing integrons, four of which were complex Class I integrons and two unconventional integrons. Notably, a novel conjugative plasmid, pKP228-1, was discovered carrying a complex Class I integron with a unique gene cassette array encoding 12 ARGs, and harboring blaNDM-1 in the adjacent ISCR1-associated region. Another plasmid, pKP174-2, harbored mcr-8.1 and tporJ1-tmexCD1. Additionally, 24 plasmids encoded resistance to eight heavy metals/metalloids, and 12 plasmids co-harbored both ARGs and metal resistance genes, indicating potential co-selection mechanisms. This study highlights the extensive diversity and novel structures of plasmids carrying both antibiotic and heavy metal resistance in clinical Klebsiella isolates. The observed co-occurrence of the two resistance types highlights the need for comprehensive genomic surveillance to monitor the spread of multi-resistance determinants.

1 Introduction

In recent years, the increasing prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria has become a significant threat to public health worldwide. Klebsiella species, particularly Klebsiella pneumoniae, have emerged as critical opportunistic pathogens accountable for a wide range of infections associated with healthcare settings (Prestinaci et al., 2015; Tacconelli et al., 2018). K. pneumoniae is a prevalent Gram-negative bacteria belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family are responsible for various illnesses, including pneumonia, bacteremia, liver abscess, and urinary tract infections (Navon-Venezia et al., 2017). This bacterium is also known for its high level of antibiotic resistance, which has significantly impacted the treatment of its infections.

The primary reason for multidrug resistance of Klebsiella strains is its accumulation of antibiotic-resistant plasmids (Li et al., 2018). Plasmids allow for the horizontal transfer of resistance traits between bacterial strains (Giraud et al., 2017; Rozwandowicz et al., 2017; Su et al., 2024). Certain antibiotic-resistant bacteria can harbor several plasmids, facilitating the exchange of antibiotic-resistance genes (ARGs) among them (Weingarten et al., 2018). It has been recognized that ARG transfer across plasmids is widespread, and 87% of ARGs were identified to transfer among distinct plasmids among 8,229 plasmid-borne ARGs (Wang et al., 2024a). In hospital settings, the transfer of antibiotic-resistant plasmids between bacteria is accelerated under the selective pressure exerted by antibiotics in the environment, which contributes to the emergence of highly antibiotic resistant pathogens (Li et al., 2022).

In addition to antibiotics, heavy metals are also known to contaminate hospital wastewater (Emmanuel et al., 2009). This is likely caused by the frequent pharmaceutical use of heavy metals. For instance, silver is often used as a disinfectant (Silvestry-Rodriguez et al., 2007), whereas mercury is commonly used as tooth fillings (Pradhan and Srivastava, 2022). Studies have shown that hospital effluents can contain both heavy metals and pharmaceuticals, as observed in wastewater from Indonesian hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic (Sakina et al., 2023), highlighting potential environmental and health risks. Therefore, clinical Klebsiella strains are often found to be heavy metal-resistant or heavy metal-tolerant (Radisic et al., 2024). Whether the emergence of heavy metal resistance is also driven similarly as antibiotic resistance, aka by accumulation of resistance plasmids, still needs further investigations.

Surveillance of plasmids in Klebsiella strains has shown that a high percentage of detected plasmids are new (Wang et al., 2024b; Xu et al., 2024). This can be attributed to the higher level of variability of plasmids due to carriage of recombination-related genes, as well as the lack of affordable sequencing technologies that can reliably detect and sequence whole plasmids. Application of 3rd generation sequencing technologies, with the fast decrease of sequencing costs, has enabled cost-effective detection of plasmids. Therefore, we are now at a position to better understand plasmid-mediated antibiotic and heavy metal resistance in Klebsiella and other pathogenic bacteria.

This work aims to analyze plasmid-encoded antibiotic and heavy metal resistance in Klebsiella strains in a clinical setting. Specifically, we investigated (1) the role of plasmids in heavy metal resistance, (2) the co-occurrence between antibiotic and heavy metal resistance, and (3) the occurrence and characteristics of newly identified heavy metal-resistant plasmids similar to antibiotic-resistant plasmids.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Bacterial strains

Klebsiella spp. used in this work were isolated from wastewater collected from a wastewater treatment facility between 2019 and 2020 from Qilu Hospital in Qingdao, China, as described in our previous publication (Li et al., 2022). Klebsiella strains were purified by growth overnight at 37°C on MacConkey agar plates without antibiotics.

2.2 Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Antibiotic MICs were determined using the broth microdilution method in 96-well plates, following the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines. The antibiotics tested included Imipenem, Tigecycline, Polymyxin E, Ampicillin, Cefotaxime, Kanamycin, Streptomycin, Trimethoprim, Tetracycline, Ciprofloxacin, Gatifloxacin, Meropenem, and Sulfisoxazole. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as a quality control strain for antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

2.3 DNA extraction and whole-genome sequencing

The genomic DNA of Klebsiella strains was extracted using the TIANamp DNA Kit (Tiangen Biotech (Beijing) Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity and quantity of DNA were determined using a Qubit™ 4.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, US). The sequencing library was constructed from 150 ng of genomic DNA using the Oxford Nanopore rapid barcoding kit SQK-RBK114.96. It was sequenced on the Nanopore p2solo platform (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) with an R10.4.1 flow cell. To obtain raw data, Basecalling was performed using Dorado version 0.5.3 (https://github.com/nanoporetech/dorado/).

2.4 Bioinformatics

The analysis of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data for all isolates was conducted utilizing various bioinformatics tools. Flye version 2.8.1-b1676 was employed to assemble the genomes from long reads (Kolmogorov et al., 2019) and to determine sequence circularity. Additionally, Quast version 5.0.2 and CheckM2 version 1.0.2 were utilized to assess the assembly’s quality and completeness and check for contamination (Mikheenko et al., 2018; Chklovski et al., 2023). GTDB-Tk version 2.1.1 was used to determine the taxonomic classification of genomes. The genomes were annotated with the Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipleline (Tatusova et al., 2016). AMRFinder version 3.11.26 and Plasmidfinder version 2.1.1 were utilized to identify antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) and plasmid replicon types (Carattoli et al., 2014; Feldgarden et al., 2019). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and serotypes were identified using kleborate.

2.5 Quality control and assembly assessment

Raw reads were subjected to quality control using fastp (v0.23.4). Adapter sequences and low-quality bases (Q < 20) were trimmed, and reads shorter than 500 bp after trimming were removed. The quality of clean reads was checked with FastQC, ensuring that >90% of bases reached Q30. Genome assemblies were subsequently evaluated with QUAST (v5.2.0) to obtain metrics including N50, GC content, and genome size. Assembly completeness and contamination were assessed using CheckM (v1.0.2).

2.6 Metal resistance assays

Heavy metal resistance assays were performed by agar dilution using Mueller-Hinton Agar plates. Overnight cultures of strains were diluted and adjusted to an OD600 value of 0.08–0.1 using LB medium. A 5 µL aliquot of the diluted cultures was inoculated onto MH Agar plates containing various concentrations of metals. Metal salts, including K2TeO3, CuSO4, CoCl2, AgNO3, K2Cr2O7, NiSO4, and HgCl2, were added to the media, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. Experiments were performed with three (n=3) independent technical replicates. K. pneumoniae ATCC13883 was used as the control strain.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Klebsiella strains isolated from hospital wastewater and whole genome sequencing

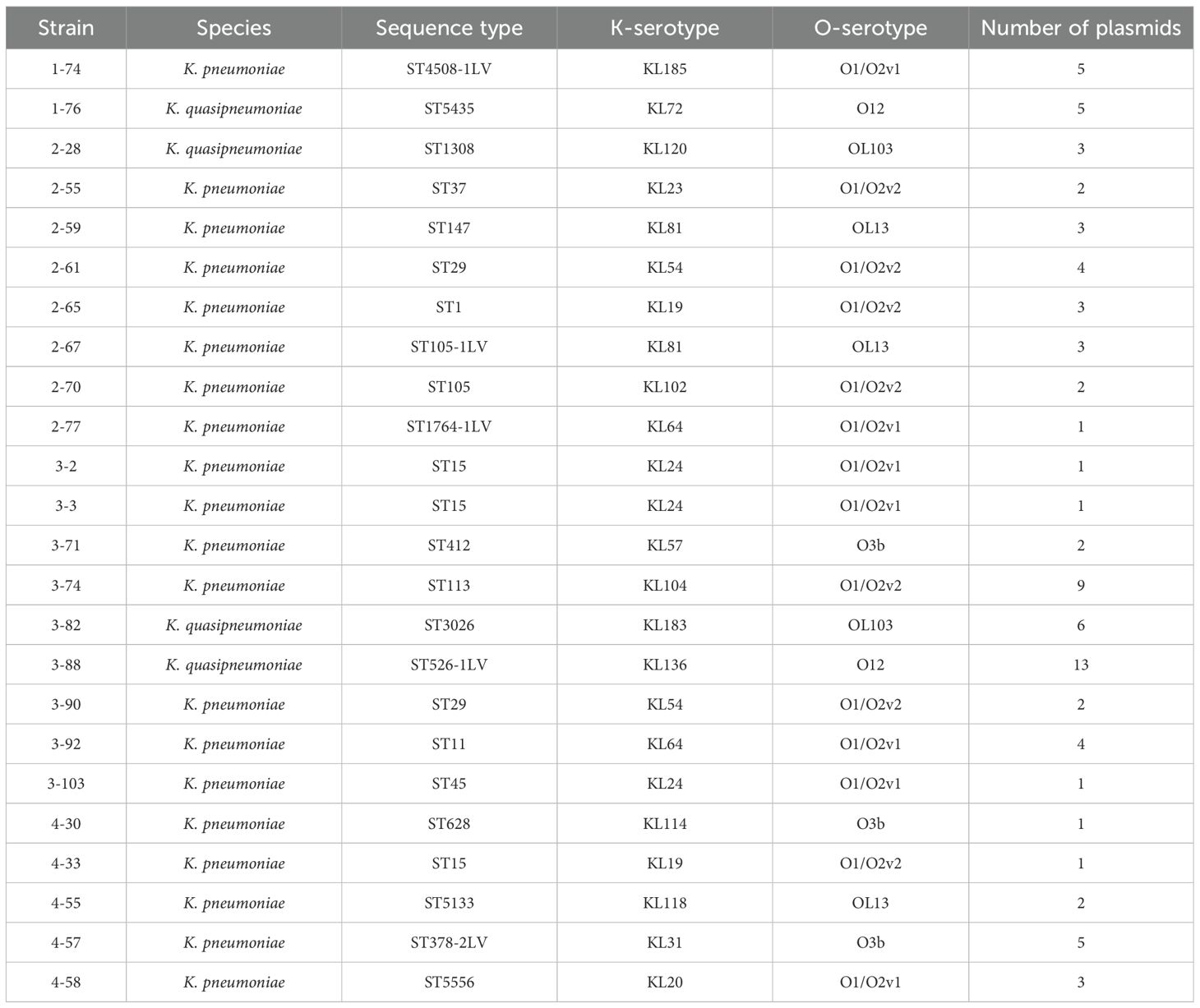

Thirty-three Klebsiella isolates were obtained from the wastewater of Qilu Hospital Qingdao as part of a large-scale surveillance of wastewater bacterial communities previously reported by our group (Li et al., 2022). Four of the isolates, 1-76, 2-28, 3-82, and 3-88, are Klebsiella quasipneumoniae strains, while the remaining strains are K. pneumoniae strains. Third generation Nanopore sequencing was performed to obtain the whole genome sequences of these isolates. The long reads of this technology led to the assembly of high quality genomes, with the generation of near-perfect plasmid maps. All 33 isolates have their chromosomes well assembled to their circular forms, with the sizes of 5.34 ± 0.11 Mb, in agreement with the common sizes of Klebsiella chromosomes. Only four of the isolates were free of plasmids, all of which are K. pneumoniae. Analysis of plasmid-containing Klebsiella isolates suggested that they belong to 24 genomically distinct strains, as determined by whole-genome sequence similarity and assigned LIN codes using the Pathogenwatch cgMLST-based classification system (Supplementary Table 1). These strains were subject to further studies. Features of these strains are documented in Table 1. These strains belong to various and diverse sequence types and serotypes, showing high levels of heterogeneity. On average, they carry 3.4 plasmids per strain.

Among the 81 plasmids identified from the 24 Klebsiella strains, 28 (34.6%) were considered novel (Supplementary Table 1). Plasmid novelty was assessed by BLASTn comparison against the NCBI NT database, using <80% backbone sequence identity and <70% coverage as thresholds. The comparison was made with previously reported plasmids in public databases. These findings, consistent with our earlier report (Xu et al., 2024), suggest ongoing plasmid diversification and structural rearrangement within Klebsiella populations.

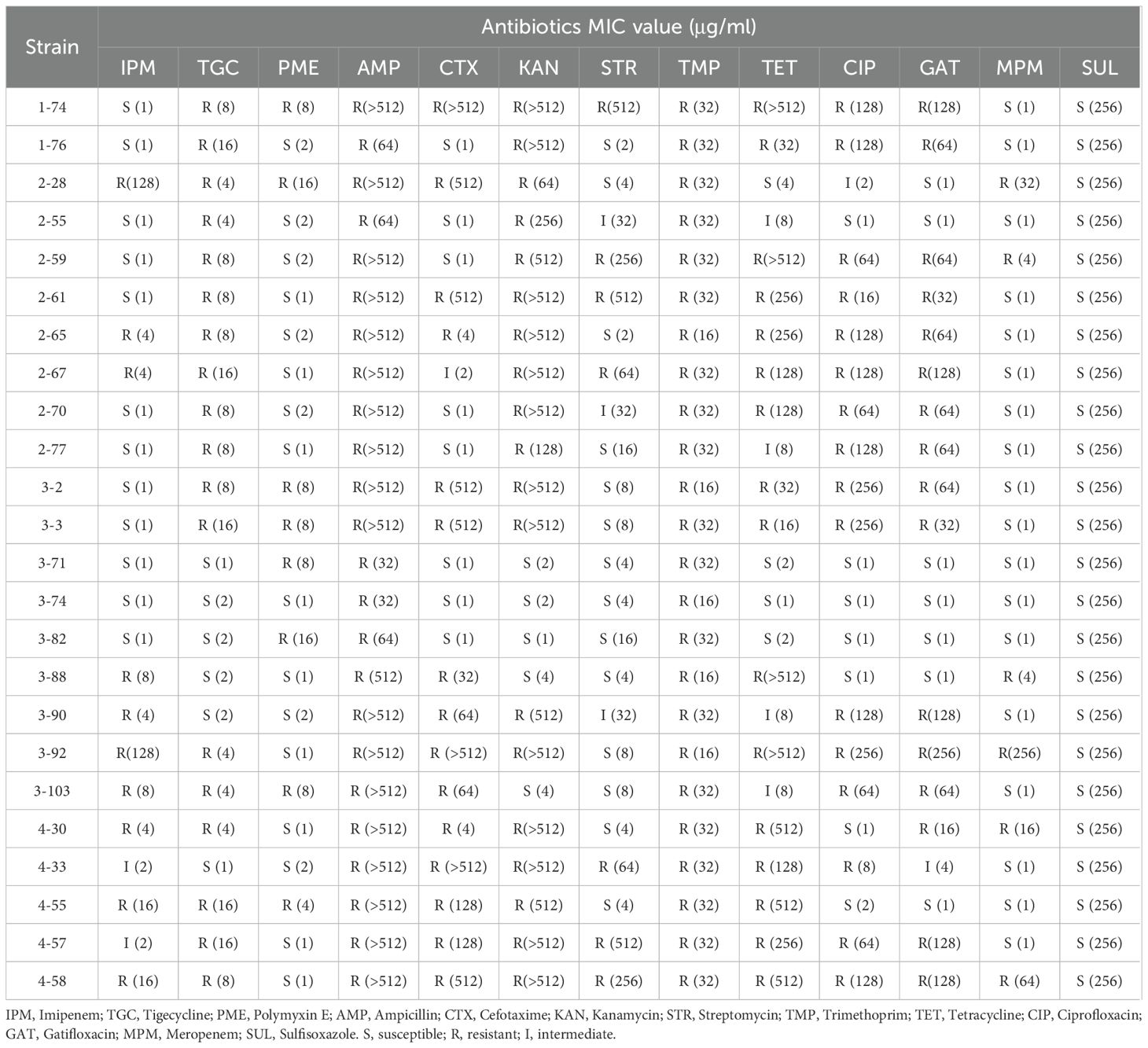

3.2 Antimicrobial resistance determinants in isolated Klebsiella strains

Fifteen of the 24 isolated Klebsiella strains carry antimicrobial resistance determinants on their plasmids (Supplementary Table 1), consistent with our previous finding that K. pneumoniae acquire antibiotic resistant plasmids for its antibiotic resistance (Li et al., 2018). A total of 22 such antibiotic resistant plasmids were identified. Five Klebsiella strains carried more than one antibiotic resistant plasmid, agreeing with the hypothesis that acquisition of multiple antibiotic resistant plasmids can lead to multidrug resistance in Klebsiella. To further evaluate their phenotypic resistance, minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of representative antibiotics were determined for all strains. The MIC data, summarized in Table 2, reveal substantial variation in resistance levels among the isolates, with several strains exhibiting high-level resistance to multiple antibiotics.

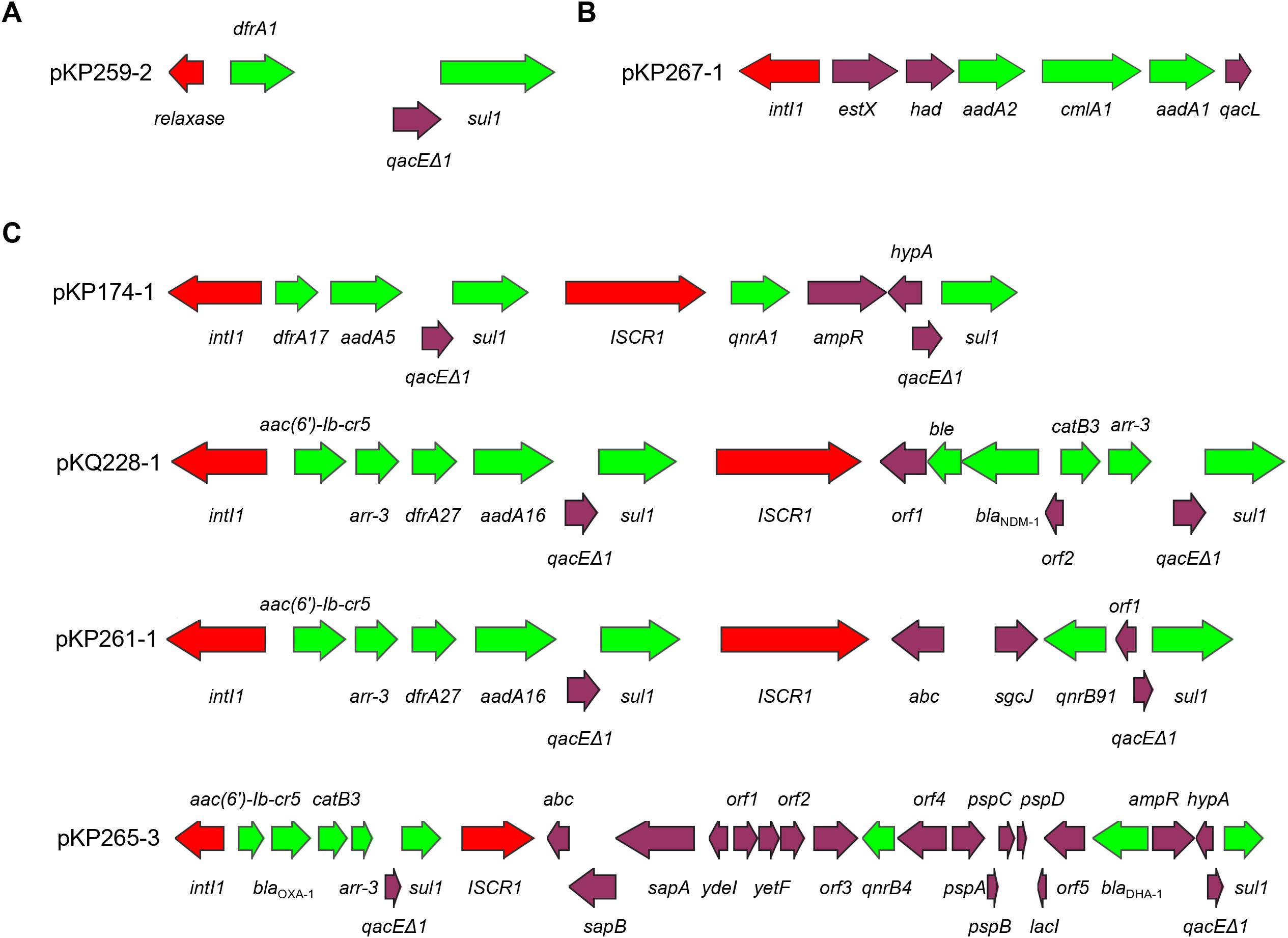

A high level prevalence of integrons were found to be associated to ARGs. Of the 22 antibiotic resistant plasmids, 12 carry integrons, four of which are complex Class I integrons (Table 3). Two of the integrons are unconventional. The integron carried by pKP265–1 has the exact structure of a common Class I integron, but does not carry an integrase-coding gene. Instead, it carries a relaxase-coding gene (Figure 1A). Whether this gene can encode an enzyme that functions similarly to an integrase is unknown. K. pneumoniae 2–67 carries an IncFII(K)-type antibiotic resistant plasmid p267–1 that also carries an unusual but not unprecedented Class I integron with the gene cassette array ending with qacL and lacking sul1 (Figure 1B) (Alves et al., 2025).

Figure 1. Intergrons in antibiotic resistant plasmids. Panel (A) pKP259–2 in which an ‘integron’ carries a relaxase-coding gene rather than intI1; Panel (B) an unconventional Class I integron in pKP267-1; Panel (C) complex Class I integrons found in this work. Red color indicates integrase/transposase-coding gene, green color indicates antibiotic resistance gene.

Four antibiotic resistant plasmids carry complex Class I integrons that are diverse in their structures (Figure 1C). Of particular interest is pKQ228-1, an unreported potentially conjugative plasmid that carries a very large complex Class I integron with a novel gene cassette array harboring 12 ARGs, including blaNDM-1, which is located within the ISCR1-associated integron region. Comparative analysis with regional blaNDM-1 plasmids carrying complex class 1 integrons revealed distinct integron structures in pKQ228-1 (Supplementary Figure S1). Complex Class I integrons carrying blaNDM-1 were previously reported in Proteus mirabilis (Li et al., 2023), Enterobacter hormaechei (Doualla-Bell et al., 2021), Enterobacter cloacae (Zhu et al., 2020), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Kostyanev et al., 2020), and Raoultella ornithinolytica (Yu et al., 2020). To our knowledge, blaNDM-1 has not previously been reported within complex Class I integrons in Klebsiella species. The identification of such a structure in clinical Klebsiella strain may suggest a new approach of dissemination of carbapenem resistance in Klebsiella.

K. pneumoniae 1–74 hosts a conjugative pKP174–2 plasmid that carries mcr-8.1 and tporJ1-tmexCD1. This plasmid may serve as a vehicle for the dissemination of resistance to polymyxin and tigecycline, both considered last-line antibiotics. Indeed, K. pneumoniae 1–74 is resistant to both polymyxin (MIC = 8 μg/ml) and tigecycline (MIC = 8 μg/ml). To verify transferability, a conjugation assay using K. pneumoniae 1-74 (donor) and E. coli BW25113+pRedCas9 (recipient) was performed. Transconjugants selected on MacConkey agar with streptomycin (200 µg/mL) and polymyxin E (2 µg/mL) were PCR-positive for mcr-8.1, confirming plasmid transfer. The transconjugant exhibited elevated MICs (Polymyxin E: 64 μg/mL; Tigecycline: 8 μg/mL), indicating that pKP174–2 confers transferable resistance. This plasmid is closely related to pHNAH8I-1 from which tigecycline-resistant tporJ1-tmexCD1 was first identified (Lv et al., 2020). The two plasmids share conserved regions carrying mcr-8.1, tmexCD1-toprJ1, and conjugation-associated genes, highlighting their structural similarity and potential for horizontal dissemination (Supplementary Figure S2). However, K. pneumoniae strain AH8I that carried pHNAH8I-1, along with the other four reported similar strains were from chicken fecal samples (Lv et al., 2020). The identification of K. pneumoniae 1–74 that is from hospital samples suggested that this plasmid has now entered clinical settings and poses a direct threat to patients.

The extent of transferability of ARGs found in Klebsiella strains in this work, either in the form of plasmids or integrons, showed that Klebsiella strains quickly exchange and acquire antibiotic resistance with mobile genetic elements. This is important for the clinical setting, particularly in hospitals, because the chances of antibiotic resistant strains meet and exchange antibiotic resistance are much higher than in communities. Antibiotic resistant genetic elements can accumulate to a high level in these settings, as can be confirmed by the finding of plasmid- and integron-rich multidrug resistant Klebsiella strains in this work.

3.3 Enriched transferrable heavy metal resistance genes in hospital-origined Klebsiella strains

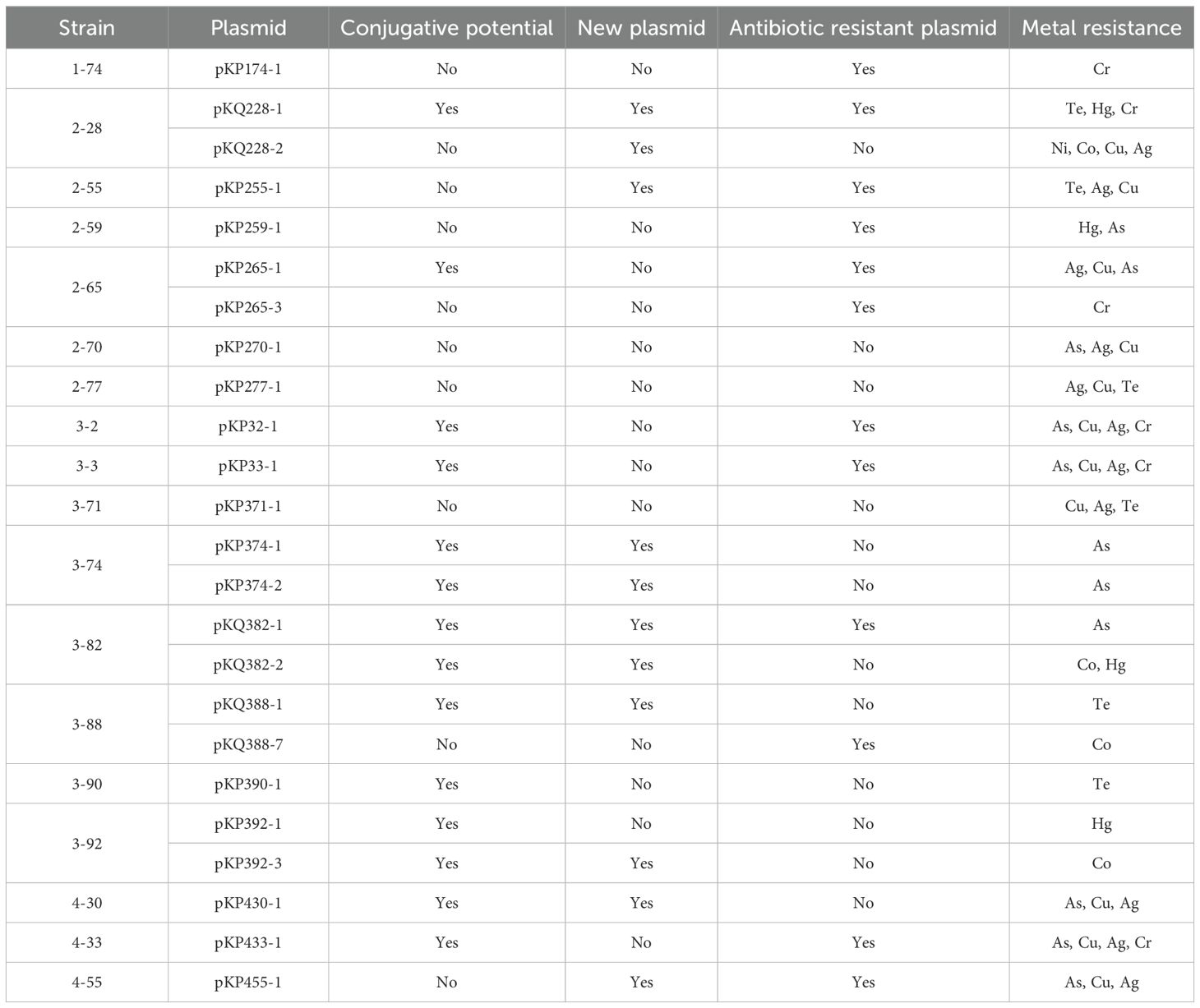

One alarming finding is the extent of heavy metal resistance genes in isolated Klebsiella strains. Eighteen out of 24 strains carry heavy metal resistance genes, more than that carry antibiotic resistance genes (Table 4). Resistance genes for eight metals and metalloids were found: chromate, tellurium, silver, copper, nickel, arsenate, cobalt, and mercury. These resistance genes were identified on 24 distinct plasmids, indicating their potential for horizontal transfer and contribution to metal resistance dissemination. This number is also larger than the 22 antibiotic resistant plasmids found. This reflects that heavy metal resistance is even more prevalent than antibiotic resistance in clinical Klebsiella strains isolated in this work.

The enriched transferrable heavy metal resistance genes in Klebsiella showed that metal resistance is even worse than, or at least comparable with, antibiotic resistance in the hospital setting studied in this work. This makes sense, because in hospitals heavy metals are commonly used for medication. In the case of traditional Chinese medicine, herbs are also often contaminated by heavy metals (Yang et al., 2018). This may explain the level of heavy metal resistance observed in this study. Previous research has shown that hospital effluents often contain heavy metals and other pollutants. For example, analyses of hospital wastewater from hospitals in Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic, detected heavy metals and pharmaceuticals that may exert co-selection pressure on bacteria (Sakina et al., 2023). Although specific data for Chinese hospitals remain limited, these findings suggest that hospital-originated Klebsiella strains may be exposed to both antibiotic and heavy metal selective pressures, warranting further investigation.

The level of transferability for metal resistance genes is high. Not only are they hosted by plasmids, 58.3% (14) of these plasmids also carry transconjugation gene cassettes (Table 4). This prompted us to wonder whether heavy metal resistance, similarly to antibiotic resistance, is also enriched in clinical Klebsiella strains under constant selection pressure, and induced by high transferability of the heavy metal resistance determinants.

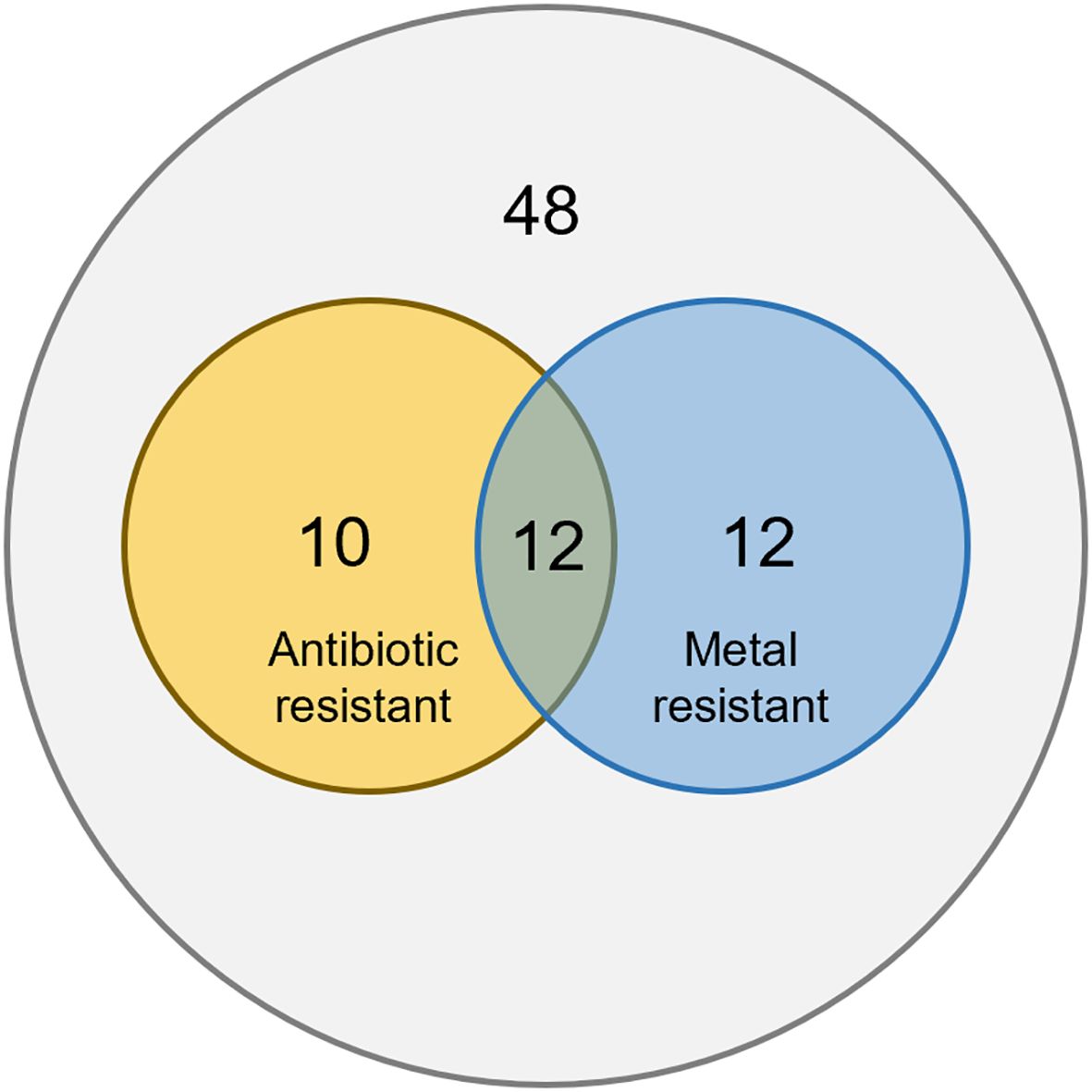

Twelve plasmids were found to host both antibiotic resistance genes and heavy metal resistance genes. This accounts for 54.5% of antibiotic resistant plasmids, and 50% of heavy metal resistant plasmids. This suggests co-selection of antibiotic and metal resistance on plasmids (Figure 2). Previous studies have shown that exposure to antibiotics or heavy metals can promote co-selection of resistance determinants across different stressors (Wales and Davies, 2015; Mustafa et al., 2021), indicating that environmental contaminants can drive the aggregation and dissemination of multiple resistance traits. We suspect that antibiotic or heavy metal stress can induce the evolution and aggregation of not only the resistance against the exposed stress, but also resistance against the other stress.

Heavy metal resistance genes were organized in a limited number of gene clusters in the metal resistant plasmids found (Figure 3). This is another piece of evidence suggesting the transferability of heavy metal resistance among Klesiella strains. Identical metal resistant clusters could be found in different plasmid types, under different genetic contexts, in different strains, and even in different species (K. pneumoniae and K. quasipneumoniae).

Figure 3. Plasmid-borne heavy metal resistance gene clusters. Panel (A) Chromate-resistant gene clusters; Panel (B) Tellurium-resistant gene clusters; Panel (C) Silver-resistant gene clusters; Panel (D) Copper-resistant gene clusters; Panel (E) Nickel-resistant gene cluster; Panel (F) Arsenate-resistant gene clusters; Panel (G) Cobalt-resistant gene clusters; Panel (H) Mercury-resistant gene clusters. Red coloor indicates integrase/transposase-coding gene, blue color indicates heavy metal resistance gene, purple color indicates others genes. Strain 3–82 harbors plasmid pKQ382-2, which contains an incomplete mercury resistance cluster.

The genetic organization of heavy metal resistance gene clusters were inspected. All chromate resistance was generally associated with the presence of chrA that encodes a membrane-bound efflux pump (Caballero-Flores et al., 2012). Three genetic structures were found associated with chrA, with a IS6100-eal-padR-chrA structure present in both K. pneumoniae and K. quasipneumoniae (Figure 3A). Three conserved genetic structures were found to be related to tellurium resistance, with the gene cluster in pKP388–1 being a variant of that in pKP228-1 (Figure 3B). All silver-resistant gene clusters are similar. Those present in pKP32-1, pKP33-1, and pKP371–1 are IS903 insertion variants of those found in pKQ228-2. In hospitals, silver is widely used as disinfectants for its antibacterial properties (Li and Xin, 2025). Therefore, the prevalence of its resistance in hospital wastewaters is not a surprise. Similarly, a copper resistant gene cluster (like in pKP228-2) and its ΔpcoE2 variant led to copper resistance. Both nickel and cobalt resistance were encoded in the same gene cluster in pKQ228-2 (Figure 3E and 3G), whereas in three plasmids nonspecific transporter corA may be responsible for cobalt resistance (Gibson et al., 1991). Arsenic resistance was prevalent and three forms of gene clusters were found to encode arsenic resistance (Figure 3F). Arsenic trioxide is a well-known medicine for acute promyelocytic leukemia, explaining the prevalence of its resistance mechanisms (Paul et al., 2023). Resistance gene clusters for mercury, an environmental pollution and widely used dental filling (Iqbal and Asmat, 2012), was also found in four plasmids in three formats. While some resistant strains lacked the corresponding genes, the observed associations are supported by previous reports and suggest potential genotype–phenotype correlations.

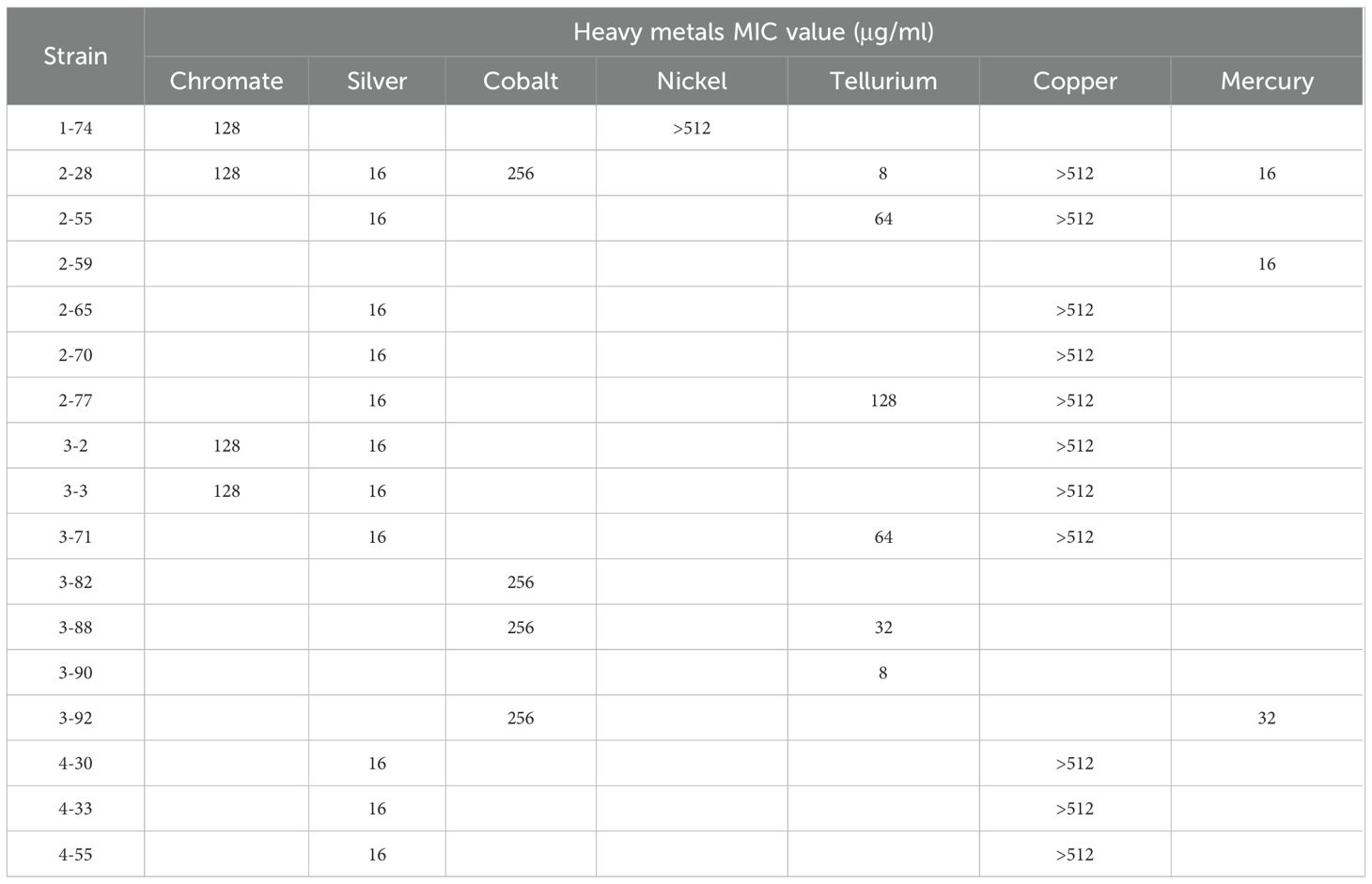

Phenotypic analysis of heavy metal resistance was performed for Klebsiella strains that host heavy metal resistance genes, except for arsenic resistance because arsenic-containing compounds are heavily regulated and cannot be purchased. A high level of concordance was found on the carriage of heavy metal resistance and heavy metal resistance phenotypes (Supplementary Figure S3). The detailed MIC results for different heavy metals are summarized in Table 5, further supporting the observed genotype–phenotype consistency. Several exceptions exist: strains 2-28, 2-65, 3-2, and 4–33 carry chromate resistance genes but did not show chromate resistance; strain 3–82 carries mercury resistance genes but didn’t show mercury resistance. The case for 3-82 (pKQ382-2) should be due to the incompleteness of the mercury resistance cluster in strain 3-82 (Figure 3).

The analysis of antibiotic resistance and heavy metal resistance can provide answers to the questions we aimed to answer in this work. Plasmids play a major role in heavy metal resistance in Klebsiella species, as heavy metal resistance plasmids are similarly prevalent in the clinical Klebsiella strains studied. Antibiotic resistance and heavy metal resistance showed a high level of correlation, and co-selection of the two resistance types could be taking place. Similarly to antibiotic resistance plasmids, a large portion (45.8%) of heavy metal resistance plasmids are new. This work showed how little we know about the structure and types of antibiotic and heavy metal resistance plasmids in Klebsiella, and provides rationale for truly large scale surveillance. We believe this work serves as a starting point for such investigations.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, PRJNA1273660.

Author contributions

GE: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. WS: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SW: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. ZY: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. MZ: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. XG: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. HX: Writing – review & editing. LL: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by National Key Research and Development Program of China [grant number 2022YFE0199800], the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 82271658], SKLMT Frontiers and Challenges Project [grant number SKLMTFCP-2023-01], the Intramural Joint Program Fund of State Key Laboratory of Microbial Technology [grant number SKLMTIJP-2025-02], Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation [grant numbers ZR2024QD228 and ZR2024QC311], Qingdao Natural Science Foundation [grant number 24-4-4-zrjj-40-jch], and Opening Project of Shanghai Key Laboratory of Atmospheric Particle Pollution and Prevention (LAP) [grant number FDLAP24008].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2025.1653886/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Comparative analysis of the blaNDM-1 regions of plasmid pKQ228–1 and representative blaNDM-1-harboring plasmids carring complex class 1 integrons. Arrows represent open reading frames, colored according to functional annotation.

Supplementary Figure 2 | Comparative plasmid map of pKP174–2 and pHNAH8I-1. Resistance genes (mcr-8.1, tmexCD1-toprJ1) and conjugation-related modules are highlighted with distinct colors and symbols.

Supplementary Figure 3 | Heavy metal resistance phenotypes. Panel A. Chromate resistance; Panel B. Silver resistance; Panel C. Cobalt resistance; Panel D. Nickel resistance; Panel E. Tellurium resistance; Panel F. Copper resistance; Panel G. Mercury resistance. K. pneumoniae ATCC13883 was used as the control strain. All K. pneumoniae ATCC13883 figures at zero heavy metal concentrations are the same plate, as they are essentially the same experiment (no metal, the same strain).

References

Alves, T. D. S., Rosa, V. S., Lara, G. H. B., Ribeiro, M. G., and da Silva Leite, D. (2025). High frequency of chromosomal polymyxin resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from dairy farm animals and genomic analysis of mcr-1-positive strain. Braz. J. Microbiol. 56, 1303–1310. doi: 10.1007/s42770-025-01634-9

Caballero-Flores, G. G., Acosta-Navarrete, Y. M., Ramírez-Díaz, M. I., Silva-Sánchez, J., and Cervantes, C. (2012). Chromate-resistance genes in plasmids from antibiotic-resistant nosocomial enterobacterial isolates. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 327, 148–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02473.x

Carattoli, A., Zankari, E., García-Fernández, A., Voldby Larsen, M., Lund, O., Villa, L., et al. (2014). In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14

Chklovski, A., Parks, D. H., Woodcroft, B. J., and Tyson, G. W. (2023). CheckM2: a rapid, scalable and accurate tool for assessing microbial genome quality using machine learning. Nat. Methods 20, 1203–1212. doi: 10.1038/s41592-023-01940-w

Doualla-Bell, F., Boyd, D. A., Savard, P., Yousfi, K., Bernaquez, I., Wong, S., et al. (2021). Analysis of an IncR plasmid carrying blaNDM-1 linked to an azithromycin resistance region in Enterobacter hormaechei involved in an outbreak in quebec. Microbiol. Spectr. 9, e0199821. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01998-21

Emmanuel, E., Pierre, M. G., and Perrodin, Y. (2009). Groundwater contamination by microbiological and chemical substances released from hospital wastewater: Health risk assessment for drinking water consumers. Environ. Int. 35, 718–726. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2009.01.011

Feldgarden, M., Brover, V., Haft, D. H., Prasad, A. B., Slotta, D. J., Tolstoy, I., et al. (2019). Validating the AMRFinder tool and resistance gene database by using antimicrobial resistance genotype-phenotype correlations in a collection of isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63, e00483–e00419. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00483-19

Gibson, M. M., Bagga, D. A., Miller, C. G., and Maguire, M. E. (1991). Magnesium transport in Salmonella typhimurium: The influence of new mutations conferring Co2+ resistance on the CorA Mg2+ transport system. Mol. Microbiol. 5, 2753–2762. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01984.x

Giraud, E., Rychlik, I., and Cloeckaert, A. (2017). Editorial: Antimicrobial resistance and virulence common mechanisms. Front. Microbiol. 8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00310

Iqbal, K. and Asmat, M. (2012). Uses and effects of mercury in medicine and dentistry. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 24, 204–207.

Kolmogorov, M., Yuan, J., Lin, Y., and Pevzner, P. A. (2019). Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 540–546. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0072-8

Kostyanev, T., Nguyen, M. N., Markovska, R., Stankova, P., Xavier, B. B., Lammens, C., et al. (2020). Emergence of ST654 Pseudomonas aeruginosa co-harbouring blaNDM-1 and blaGES-5 in novel class I integron In1884 from Bulgaria. J. Glob Antimicrob. Resist. 22, 672–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.06.008

Li, C.-A., Guo, C.-H., Yang, T.-Y., Li, F.-Y., Song, F.-J., and Liu, B.-T. (2023). Whole-genome analysis of blaNDM-bearing Proteus mirabilis isolates and mcr-1-positive Escherichia coli isolates carrying blaNDM from the same fresh vegetables in China. Foods 12, 492. doi: 10.3390/foods12030492

Li, C. and Xin, W. (2025). Different disinfection strategies in bacterial and biofilm contamination on dental unit waterlines: A systematic review. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 23, 516–527. doi: 10.1111/idh.12899

Li, W., Yang, Z., Hu, J., Wang, B., Rong, H., Li, Z., et al. (2022). Evaluation of culturable ‘last-resort’ antibiotic resistant pathogens in hospital wastewater and implications on the risks of nosocomial antimicrobial resistance prevalence. J. Hazard Mat 438, 129477. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129477

Li, L., Yu, T., Ma, Y., Yang, Z., Wang, W., Song, X., et al. (2018). The genetic structures of an extensively drug resistant (XDR) Klebsiella pneumoniae and its plasmids. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 8. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00446

Lv, L., Wan, M., Wang, C., Gao, X., Yang, Q., Partridge, S. R., et al. (2020). Emergence of a plasmid-encoded Resistance-Nodulation-Division efflux pump conferring resistance to multiple drugs, including tigecycline, in Klebsiella pneumoniae. mBio 11, e02930–e02919. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02930-19

Mikheenko, A., Prjibelski, A., Saveliev, V., Antipov, D., and Gurevich, A. (2018). Versatile genome assembly evaluation with QUAST-LG. Bioinformatics 34, i142–i150. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty266

Mustafa, G. R., Zhao, K., He, X., Chen, S., Liu, S., Mustafa, A., et al. (2021). Heavy metal resistance in Salmonella Typhimurium and its association with disinfectant and antibiotic resistance. Front. Microbiol. 12. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.702725

Navon-Venezia, S., Kondratyeva, K., and Carattoli, A. (2017). Klebsiella pneumoniae: A major worldwide source and shuttle for antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 41, 252–275. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux013

Paul, N. P., Galván, A. E., Yoshinaga-Sakurai, K., Rosen, B. P., and Yoshinaga, M. (2023). Arsenic in medicine: Past, present and future. Biometals 36, 283–301. doi: 10.1007/s10534-022-00371-y

Pradhan, S. and Srivastava, A. (2022). Roadmap to mercury-free dentistry era: Are we prepared? Dent. Res. J. (Isfahan) 19, 77. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.356812

Prestinaci, F., Pezzotti, P., and Pantosti, A. (2015). Antimicrobial resistance: A global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog. Glob Health 109, 309–318. doi: 10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000030

Radisic, V., Salvà-Serra, F., Moore, E. R. B., and Marathe, N. P. (2024). Tigecycline-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains from sewage in Norway carry heavy-metal resistance genes encoding conjugative plasmids. J. Glob Antimicrob. Resist. 36, 482–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2023.10.023

Rozwandowicz, M., Brouwer, M. S. M., Zomer, A. L., Bossers, A., Harders, F., Mevius, D. J., et al. (2017). Plasmids of distinct IncK lineages show compatible phenotypes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, e01954–e01916. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01954-16

Sakina, N. A., Sodri, A., and Kusnoputranto, H. (2023). Heavy metals assessment of hospital wastewater during COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Public Health Sci. 12, 187–195. doi: 10.11591/ijphs.v12i1.22490

Silvestry-Rodriguez, N., Sicairos-Ruelas, E. E., Gerba, C. P., and Bright, K. R. (2007). Silver as a disinfectant. Rev. Environ. Contam Toxicol. 191, 23–45. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-69163-3_2

Su, W., Wang, W., Li, L., Zhang, M., Xu, H., Fu, C., et al. (2024). Mechanisms of tigecycline resistance in Gram-negative bacteria: A narrative review. Eng. Microbiol. 4, 100165. doi: 10.1016/j.engmic.2024.100165

Tacconelli, E., Carrara, E., Savoldi, A., Harbarth, S., Mendelson, M., Monnet, D. L., et al. (2018). Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: The WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3

Tatusova, T., DiCuccio, M., Badretdin, A., Chetvernin, V., Nawrocki, E. P., Zaslavsky, L., et al. (2016). NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 6614–6624. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw569

Wales, A. D. and Davies, R. H. (2015). Co-Selection of resistance to antibiotics, biocides and heavy metals, and its relevance to foodborne pathogens. Antibiotics (Basel) 4, 567–604. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics4040567

Wang, Y., Su, W., Zeng, X., Liu, Z., Zhu, J., Wang, M., et al. (2024b). Surprising diversity of new plasmids in bacteria isolated from hemorrhoid patients. PeerJ 12, e18023. doi: 10.7717/peerj.18023

Wang, X., Zhang, H., Yu, S., Li, D., Gillings, M. R., Ren, H., et al. (2024a). Inter-plasmid transfer of antibiotic resistance genes accelerates antibiotic resistance in bacterial pathogens. ISME J. 18, wrad032. doi: 10.1093/ismejo/wrad032

Weingarten, R. A., Johnson, R. C., Conlan, S., Ramsburg, A. M., Dekker, J. P., Lau, A. F., et al. (2018). Genomic analysis of hospital plumbing reveals diverse reservoir of bacterial plasmids conferring carbapenem resistance. mBio 9, e02011–e02017. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02011-17

Xu, Z., Shi, L., Meng, T., Luo, M., Zhu, J., Wang, M., et al. (2024). Diverse new plasmid structures and antimicrobial resistance in strains isolated from perianal abscess patients. Front. Microbiol. 15. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1452795

Yang, B., Xie, Y., Guo, M., Rosner, M. H., Yang, H., and Ronco, C. (2018). Nephrotoxicity and Chinese herbal medicine. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, 1605–1611. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11571017

Yu, C., Wei, X., Wang, Z., Liu, L., Liu, Z., Liu, J., et al. (2020). Occurrence of two NDM-1-producing Raoultella ornithinolytica and Enterobacter cloacae in a single patient in China: Probable a novel antimicrobial resistance plasmid transfer in vivo by conjugation. J. Glob Antimicrob. Resist. 22, 835–841. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.06.022

Keywords: Klebsiella, plasmid, hospital wastewater, metal resistance, antimicrobial resistance, integron

Citation: Engobo GP, Su W, Wang S, Yan Z, Zhang Y, Zhang M, Geng X, Xu H, Li L and Wang M (2025) Prevalent and diverse new plasmid-encoded heavy metal and antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella strains isolated from hospital wastewater. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 15:1653886. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2025.1653886

Received: 25 June 2025; Accepted: 07 November 2025; Revised: 06 November 2025;

Published: 25 November 2025.

Edited by:

Michael Marceau, Université Lille Nord de France, FranceReviewed by:

Adam Valcek, Vrije University Brussel, BelgiumBarbara Ghiglione, National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), Argentina

Copyright © 2025 Engobo, Su, Wang, Yan, Zhang, Zhang, Geng, Xu, Li and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mingyu Wang, d2FuZ21pbmd5dUBzZHUuZWR1LmNu; Ling Li, bGluZ2xpQHNkdS5lZHUuY24=

Grace Pascale Engobo

Grace Pascale Engobo Wenya Su1

Wenya Su1 Shengyao Wang

Shengyao Wang Youming Zhang

Youming Zhang Hai Xu

Hai Xu Ling Li

Ling Li Mingyu Wang

Mingyu Wang