- 1Department of General Surgery, Zhongshan Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine Affiliated to Guangzhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Zhongshan, Guangdong, China

- 2Department of Gastroenterology, The Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China

- 3Department of Gastroenterology, Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital, the First Affiliated Hospital of Hunan Normal University, Changsha, Hunan, China

- 4Hunan Provincial University Key Laboratory of the Fundamental and Clinical Research on Functional Nucleic Acid, Changsha Medical University, Changsha, Hunan, China

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), a key gastric mucosal pathogen, causes chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers, and gastric cancer. H. pylori remodel the gastric microenvironment through metabolic reprogramming to drive pathogenesis. CagA+ strains disrupt lipid metabolism, increasing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, cardiovascular, and Alzheimer’s risks via PPAR interference, GBA1 demethylation, and altered FABP1/APOA1 expression, reversible by eradication. In glucose metabolism, H. pylori promote carcinogenesis via Lonp1-induced glycolysis, PDK1/Akt dysregulation, and HKDC1/TGF-β1/MDFI-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition, while exacerbating high-fat diet-induced dysbiosis. Infection manipulates macrophage immunometabolism. Bacterial utilization of host L-lactate through H. pylori gene clusters enables proliferation, gland colonization, and immune evasion by suppressing complement activation and TNF/IL-6 secretion. Lactate-targeting strategies show therapeutic promise. Amino acid dysregulation involves H. pylori biotin protein ligase (HpBPL)-mediated catabolism and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase-induced glutathione hydrolysis, depleting antioxidants while inducing dendritic cell tolerance. branched-chain amino acids accumulation activates mTORC1, and cystine-glutamate transporter inhibition with miR-30b upregulation exacerbates mucosal damage, forming a self-sustaining “metabolic reprogramming-immune evasion-tissue destruction” cycle. These mechanisms collectively enable H. pylori to propel gastric carcinogenesis, highlighting metabolism-targeted interventions as future solutions. This review summarizes how H. pylori remodel the gastric microenvironment and drives pathogenesis by manipulating host lipid, glucose, lactate, and amino acid metabolism.

1 Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a Gram-negative, microaerophilic, spiral-shaped bacterium that colonizes the gastric mucosa and damages gastric epithelial cells (GECs). In 1982, Warren and Marshall first discovered this bacterium, identified it as a cause of chronic gastritis, and successfully isolated it. Their groundbreaking work was later awarded the Nobel Prize (Warren and Marshall, 1983; Pincock, 2005). H. pylori is the most common cause of chronic gastritis and can lead to peptic ulcers, gastric cancer (GC), and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma in some patients (Arnold et al., 2020; Malfertheiner et al., 2023; Salvatori et al., 2023). The diverse pathological changes induced by H. pylori infection arise from interactions between the host’s genetic makeup, environmental factors, and bacterial virulence factors, resulting in different phenotypes of chronic gastritis: antral-predominant, corpus-predominant, or pangastritis (Baj et al., 2020; Sharndama and Mba, 2022; Tran et al., 2024; Duan et al., 2025). Globally, approximately 50% of the population is infected. While about 80% of carriers are asymptomatic, all infected individuals develop gastritis. Significant geographical variations exist in prevalence, though a general declining trend is observed. Classified as a Group 1 carcinogen by the World Health Organization, H. pylori is a major risk factor for GC (Che et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2024). Its ability to robustly survive in the highly acidic gastric environment and evade host immune responses makes it a key driver in the progression of gastrointestinal diseases.

The pathogenesis of H. pylori is increasingly linked to its ability to manipulate host cellular processes, particularly metabolic reprogramming. This process refers to the adaptive alteration of metabolic pathways, fluxes, and key metabolite levels in response to environmental changes, playing a pivotal role in cancer malignant transformation, immune cell activation, and pathogen infections. Within the tumor microenvironment (TME), tumor cells reprogram glucose, lipid, and amino acid metabolism to competitively deplete critical nutrients (e.g., glucose, glutamine, arginine) and accumulate inhibitory metabolites (e.g., lactate), thereby suppressing CD8+ T cell function and proliferation to facilitate immune evasion (Tharp et al., 2024; Liang et al., 2025). The metabolic reprogramming of immune cells further fosters an immunosuppressive TME that dampens antitumor immunity. Targeting these metabolic pathways (e.g., combining immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) with metabolic inhibitors) and exploring the role of gastrointestinal microbiota in the TME represent potential therapeutic strategies (Zhao et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024).

In gastric disease research, metabolic reprogramming features prominently. For instance, adipocytes promote GC omental metastasis via phosphatidylinositol transfer protein, cytoplasmic 1 (PITPNC1)-mediated fatty acid metabolic reprogramming (Tan et al., 2018). Fenofibrate reprograms glycolipid metabolism in GC cells by acting on carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 (CPT1) and fatty acid oxidation pathways, activating the AMPK pathway, and inhibiting the HK2 pathway, thereby suppressing proliferation and inducing apoptosis (Chen et al., 2020). LIM Homeobox 9 (LHX9), highly expressed in GC, transcriptionally activates pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) to induce glycolytic reprogramming, enhancing the malignant properties of GC stem cells and driving tumor progression (Zhao et al., 2023). Beyond tumor cells themselves, pathogen infections also involve metabolic reprogramming: H. pylori develops drug resistance and undergoes virulence-associated metabolic alterations when exposed to clarithromycin in vitro (Rosli et al., 2024). Under cytotoxin-associated gene A+ (CagA+) H. pylori infection, mitochondrial Sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) deficiency promotes reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation by inhibiting its deacetylase activity, thereby stabilizing HIF-1α protein and enhancing its transcriptional activity; conversely, SIRT3 overexpression suppresses HIF-1α stability and activity, thereby influencing metabolic alterations (Lee et al., 2017). Thus, metabolic reprogramming serves as a core biological process linking tumorigenesis, immune evasion, pathogen infection, and therapeutic responses, making a deep understanding of its mechanisms essential for developing novel treatment strategies.

This review conducted a comprehensive literature search using the PubMed database to screen relevant studies. The search strategy employed the following keywords: “Helicobacter pylori/H. pylori,” “metabolic reprogramming,” “lipid metabolism,” “glucose metabolism,” “lactate metabolism,” “amino acid metabolism,” “gastric cancer,” “virulence factors,” and related terms. Boolean operators (AND, OR) were used to appropriately combine the terms. The inclusion criteria were: (1) original research articles and review articles; (2) studies focusing on H. pylori infection and host metabolic changes; (3) studies published in English. Exclusion criteria included: (1) studies not directly related to Helicobacter pylori or metabolism; (2) conference abstracts.

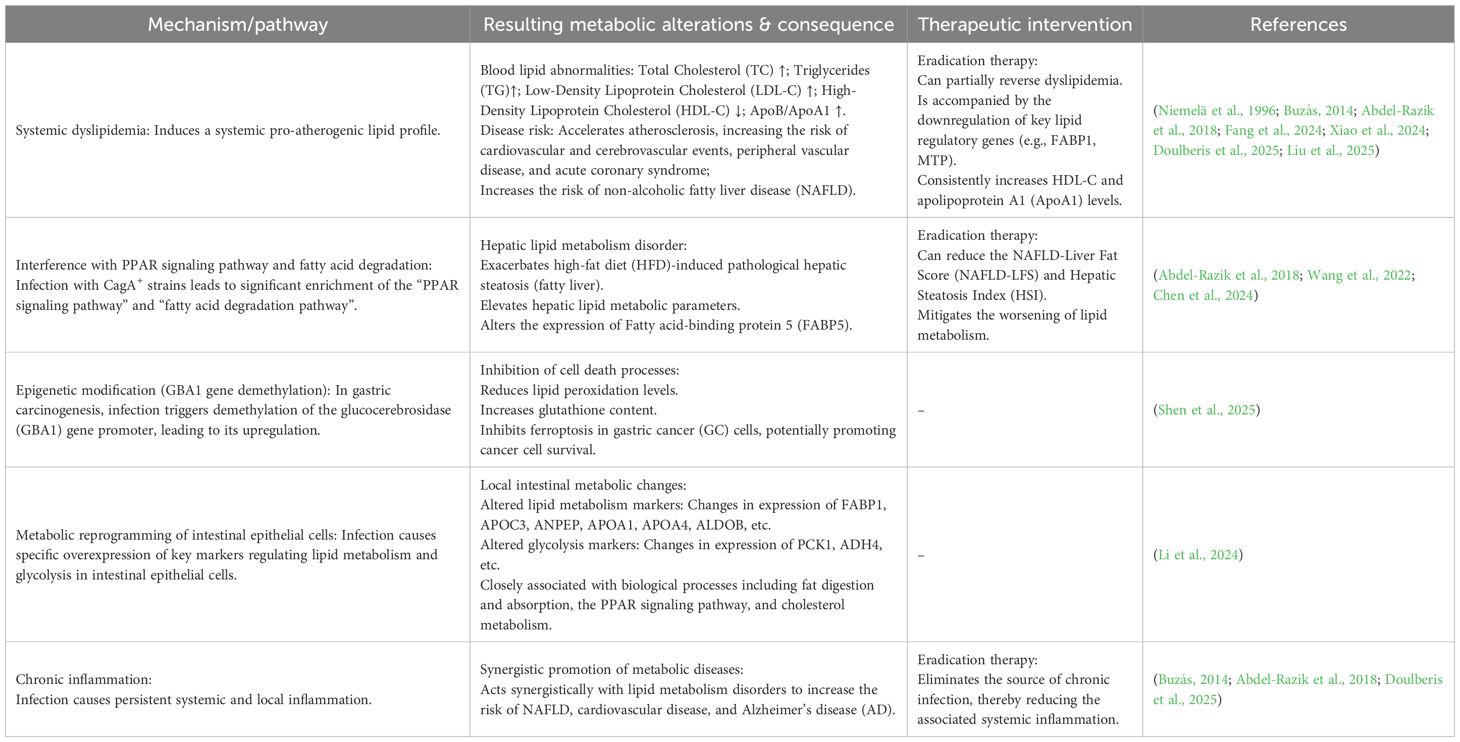

Despite the core concept of “metabolic reprogramming” being crucial in tumorigenesis, immune evasion, and infection, a systematic understanding is lacking regarding how H. pylori infection triggers and regulates this process in host GECs and the microenvironment, or how it specifically drives progression from chronic inflammation to GC. This review therefore systematically integrates current research on the interaction between H. pylori infection and host metabolic reprogramming (Table 1–4, Figure 1). It aims to elucidate the pivotal role of metabolic reprogramming in H. pylori pathogenesis, provide new insights into disease progression, and lay the groundwork for developing novel metabolism-targeted diagnostics, preventions, and therapies for H. pylori-related diseases, especially GC.

Table 1. Impact of H. pylori infection on lipid metabolism: mechanisms, abnormalities, and therapeutic interventions.

Figure 1. Pathophysiological mechanisms of metabolic reprogramming induced by H. pylori infection and potential therapeutic interventions. The diagram illustrates how H. pylori virulence factors (CagA+, gGT, lactate utilization genes hp0137–0141/hp1222) disrupt host metabolic pathways, driving disease progression. Lipid metabolism dysregulation: CagA+ strains inhibit PPAR signaling and fatty acid degradation, upregulate FABP5, and alter lipid marker expression (FABP1↑, APOA1↓). Epigenetic demethylation activates GBA1, suppressing ferroptosis and promoting atherogenic dyslipidemia (↑LDL, ↓HDL, ↑TG), which contributes to hepatic steatosis (NAFLD), cardiovascular disease (CVD), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Glucose metabolism reprogramming: Infection induces Lonp1-mediated glycolytic switching and PDK1 dephosphorylation, destabilizing Akt signaling and disrupting the apoptosis/proliferation balance. HKDC1 drives EMT via TGF-β1, while MDFI activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling—collectively promoting gastric carcinogenesis, proliferation, and metastasis. lactate metabolism: H. pylori imports host-derived lactate via hp0140–0141 and metabolizes it through hp0137–0139/hp1222. Lactate serves as a chemoattractant, enhancing bacterial proliferation and migration. Concurrently, lactate uptake inhibits complement activation, downregulates adhesins (sabA/labA), and suppresses TNF/IL-6 secretion in macrophages, facilitating immune evasion and gland colonization. Amino acid metabolism disruption: gGT hydrolyzes GSH into glutamate, depleting antioxidants and inducing oxidative stress. Glutamate inhibits dendritic cell cAMP signaling and IL-6 production, promoting immune tolerance. BCAA accumulation activates mTORC1, modulating inflammation and autophagy to support bacterial colonization. xCT inhibition upregulates miR-30b, exacerbating mucosal damage. Disease outcomes: Metabolic dysregulation drives gastric pathologies (cancer, mucosal damage), systemic inflammation, NAFLD, CVD, and AD. Therapeutic strategies: Eradication therapy (antibiotics) improves lipid profiles; garlic H2Sn-loaded microreactors target HpG6PD; rabeprazole inhibits STAT3/HK2 signaling; targeting of HKDC1/TGF-β1 signaling; GPR30/PDK inhibitors; probiotics (L. paracasei) increase lactate and block NF-κB signaling; and inhibitors of miR-30b, mTORC1, or gGT may mitigate mucosal damage and immune tolerance. CagA+, Cytotoxin-associated gene A positive; gGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; PPAR, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; FABP, Fatty acid-binding protein; GBA1, Glucocerebrosidase; LDL, Low-density lipoprotein; HDL, High-density lipoprotein; TG, Triglycerides; NAFLD, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; CVD, Cardiovascular disease; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; Lonp1, Lon protease 1; PDK1, Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1; EMT, Epithelial–mesenchymal transition; MDFI, MyoD family inhibitor; TNF, Tumor necrosis factor; GSH, Glutathione; BCAA, Branched-chain amino acid; xCT, Cystine/glutamate antiporter; HpG6PD, H. pylori glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; HK2, Hexokinase 2; DC, Dendritic cell.

2 Lipid metabolism

Lipogenesis refers to the process by which organisms convert excess ingested carbon sources like carbohydrates into fatty acids, which are further synthesized into triacylglycerols. Glucose, glutamine, lactate, ethanol, etc., are converted into acetyl-CoA, which is transported from the mitochondria to the cytosol via the citrate–pyruvate shuttle. Acetyl-CoA is then used in a multi-step reaction to synthesize palmitic acid (a 16-carbon saturated fatty acid). Triglycerides are assembled by esterifying a glycerol backbone (derived from 3-phosphoglycerate) stepwise to form storage fats (Song et al., 2018). Lipids are fundamental components of cell membranes and play crucial roles in mediating intracellular oncogenic signaling, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and the bidirectional crosstalk between TME cells and cancer cells (Beloribi-Djefaflia et al., 2016).

Tumor cells reprogram their lipid metabolism (increasing uptake, synthesis, oxidation, and storage) to survive hypoxic and nutrient-deficient conditions. This reprogramming, driven by genetic mutations and environmental pressures, reshapes the TME and induces lipid metabolic alterations in various TME cells, including cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), regulatory T cells (Tregs), CD8+ T cells, and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) (Munir et al., 2019; Jin et al., 2023). Such metabolic adaptability (or metabolic flexibility) enables cancer cells to support rapid proliferation, sustained growth, and survival under hostile conditions (Boroughs and DeBerardinis, 2015; Obre and Rossignol, 2015; Melone et al., 2018). Therefore, therapeutic strategies targeting these adaptive metabolic pathways hold significant promise for future cancer treatment.

Notably, external factors such as chronic H. pylori infection also significantly contribute to systemic dyslipidemia and influence cancer-related metabolic reprogramming. H. pylori infection can trigger lipid metabolism disruption, characterized by elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL), thereby promoting the risk of fatty liver diseases (such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD), cardiovascular diseases, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Doulberis et al., 2025). It is increasingly recognized as a contributor to dyslipidemia. Accumulating evidence indicates that infected individuals exhibit a characteristic atherogenic lipid profile, marked by elevated levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), along with reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) (Niemelä et al., 1996; Abdel-Razik et al., 2018; Xiao et al., 2024). This pattern was initially observed in early Finnish studies and subsequently confirmed by a large-scale Chinese investigation, which further identified an elevated ApoB/ApoA1 ratio as an independent risk factor for the infection (Liu et al., 2025). The resulting pro-atherogenic state is believed to accelerate the development of atherosclerosis, thereby increasing the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, as well as peripheral vascular disease (Buzás, 2014). Additionally, through mechanisms involving chronic inflammation and altered lipid metabolism, H. pylori infection may elevate the risk of NAFLD (Abdel-Razik et al., 2018).

Importantly, eradication therapy has been shown to partially reverse these metabolic abnormalities, accompanied by downregulation of key lipid regulatory genes such as FABP1 and MTP, and a consistent increase in HDL-C and apolipoprotein A levels (Tsai et al., 2006; Buzás, 2014; Iwai et al., 2019; Watanabe et al., 2021). Furthermore, H. pylori eradication can reduce NAFLD-Liver Fat Score (NAFLD-LFS) and Hepatic Steatosis Index (HSI) (Abdel-Razik et al., 2018), and mitigate the worsening of lipid metabolism (Wang et al., 2022). Notably, one study focusing on the Chinese population yielded contrasting findings. It reported that H. pylori infection itself did not significantly affect lipid metabolism markers in this population but was associated with a 4-fold increased risk of acute coronary syndrome. This heightened risk was independent of H. pylori virulence factors such as CagA or vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA) (Fang et al., 2024). Overall, existing evidence suggests that H. pylori infection, potentially through disrupting lipid metabolism (particularly elevating LDL and lowering HDL) and inducing inflammation, acts as a significant contributing factor in promoting the pathogenesis of fatty liver disease, cardiovascular disease, and AD. Eradicating H. pylori infection offers a beneficial strategy for improving lipid metabolism abnormalities and reducing the associated disease risks.

At the mechanistic level, H. pylori infection disrupts host lipid metabolism and cell death processes through multiple pathways. Specifically, infection with CagA+ strains of H. pylori was found to exacerbate high-fat diet (HFD)-induced pathological hepatic steatosis and elevate lipid metabolic parameters. RNA-seq analysis revealed that in the HFD group, differentially expressed genes were significantly enriched in the “fatty acid degradation pathway” and the “PPAR signaling pathway,” with fatty acid-binding protein 5 (FABP5) showing differential expression specifically in the context of CagA+ H. pylori infection (Chen et al., 2024). In the context of gastric carcinogenesis, H. pylori infection triggers demethylation of the glucocerebrosidase (GBA1) gene promoter, leading to its upregulation. This subsequently reduces lipid peroxidation levels and increases glutathione content, ultimately inhibiting ferroptosis in GC cells (Shen et al., 2025). Furthermore, within the intestinal epithelial cell population, key markers regulating lipid metabolism (such as FABP1, APOC3, ANPEP, APOA1, APOA4, and ALDOB) and markers regulating glycolysis (such as PCK1 and ADH4) were found to be specifically overexpressed. Further enrichment analysis indicated that these changes are closely associated with biological processes including fat digestion and absorption, the PPAR signaling pathway, and cholesterol metabolism (Li et al., 2024). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that H. pylori infection—particularly by CagA+ strains—may promote lipid metabolic dysregulation by interfering with core pathways such as PPAR signaling, inducing epigenetic modifications (e.g., demethylation of GBA1), and altering the expression of key metabolic markers in intestinal epithelial cells (Table 1, Figure 1).

3 Glucose metabolism

Glucose metabolism involves the breakdown, transformation, and utilization of glucose to provide energy (ATP) and biosynthetic precursors for life processes. Multiple metabolic pathways participate in this process. Glycolysis occurs in the cytoplasm, converting glucose to pyruvate; the most critical step is the phosphorylation of glucose to glucose-6-phosphate (G6P), which serves as a convergence point for glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), the hexosamine pathway, and glycogen synthesis. Rate-limiting enzymes in this process include hexokinase (HK), phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1), and pyruvate kinase (PK). Under aerobic conditions, pyruvate is converted to acetyl-CoA for entry into the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle; under anaerobic conditions, it is converted to lactate, thereby regenerating NAD+ to sustain glycolysis. The TCA cycle takes place in the mitochondrial matrix, utilizing acetyl-CoA derived from glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids. Key enzymes in this cycle are citrate synthase, isocitrate dehydrogenase (the rate-limiting enzyme), and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase. The PPP occurs in the cytoplasm, where glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) catalyzes the conversion of G6P to ribose-5-phosphate, a precursor for nucleotide/nucleic acid synthesis (Hay, 2016; Li and Zhang, 2016).

Beyond its role in cellular energy supply, glucose metabolic reprogramming is also implicated in various pathological processes. For instance, H. pylori infection has been shown to exacerbate glucose metabolism abnormalities and promote atherosclerosis (Yoshikawa et al., 2007; Vijayvergiya and Vadivelu, 2015). Specifically, H. pylori infection synergizes with a HFD to worsen gut microbiota dysbiosis (loss of diversity, increased Helicobacter/reduced Lactobacillus), significantly impairing the ability of antibiotics to repair HFD-induced glucose metabolism abnormalities (hyperglycemia, insulin resistance), and causing persistent Klebsiella-dominated dysbiosis (Peng et al., 2021). Thus, H. pylori infection not only disrupts glucose metabolism but also alters gut flora, thereby hindering the efficacy of antibiotic treatment in diet-induced metabolic disorders.

At the molecular level, H. pylori infection contributes to gastric carcinogenesis through multiple mechanisms. In H. pylori-infected GECs, the significantly induced Lon protease (Lonp1) promotes excessive cell growth by regulating mitochondrial stress response and driving a glycolytic metabolic switch, thereby driving gastric carcinogenesis (Luo et al., 2016). H. pylori infection induces dephosphorylation of PDK1 (at serine 241) in GECs, leading to abnormal Akt phosphorylation and degradation, disrupting cell survival signaling, and ultimately breaking the dynamic balance between apoptosis and proliferation (King and Obonyo, 2015). In CagA-positive GC cells, targeted inhibition of Akt phosphorylation or key glycolytic enzymes (HK2/LDHA) synergistically enhances 5-Fu’s killing effect on CagA-overexpressing cells, significantly reversing their drug resistance (Gao et al., 2020). In H. pylori-induced GC progression, significantly elevated HKDC1 drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) via the TGF-β1/p-Smad2 signaling axis, promoting proliferation and metastasis; inhibiting HKDC1 or TGF-β1 effectively reverses this (Fang et al., 2024). Knocking down MyoD family inhibitor (MDFI) suppresses H. pylori-induced GC cell proliferation and enhanced glycolysis; the infection promotes MDFI expression and activates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (Mi et al., 2022). Collectively, H. pylori may drive carcinogenesis via metabolic reprogramming (e.g., Lonp1-mediated glycolytic switch), disrupted signaling (PDK1/Akt), and facilitation of EMT (e.g., HKDC1/TGF-β1, MDFI/Wnt pathways).

H. pylori infection also modulates immunometabolism and inflammation. In H. pylori-induced pediatric gastritis, Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase-2 (SHP2) promotes inflammation by activating macrophage glycolysis, with its downstream transcription factor SPI1 regulating metabolic gene expression and inflammation (Li et al., 2022). Bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) mediates H. pylori clearance by macrophages through HIF-1α-mediated transcriptional activation of glycolytic genes (Slc2a1 and Hk2) and stabilizing Nos2 mRNA to promote NO production; its loss impairs glycolysis, reduces NO bactericidal capacity, lessens inflammation but increases bacterial colonization in vivo (Modi et al., 2024). Thus, H. pylori manipulates immune cell metabolism—promoting inflammation via SHP2/glycolysis and influencing bacterial clearance via BRD4-mediated glycolytic activation and NO production.

Several potential therapeutic strategies targeting metabolic pathways have been proposed. H. pylori glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (HpG6PD) may be a potential target for novel anti-H. pylori drugs (Ortiz-Ramírez et al., 2022). Hydrogen polysulfides (H2Sn) from garlic inhibit H. pylori metabolism by targeting and inactivating HpG6PDH; converting organic sulfur to Fe3S4 greatly boosts H2Sn yield, which can be encapsulated into gastric-adapted microreactors (GAPSR), enabling highly efficient (250-fold increase), rapid, and microbiota-friendly H. pylori eradication in a single dose (Wang et al., 2025). Rabeprazole inhibits GC cell proliferation by suppressing STAT3 phosphorylation and its binding to the HK2 promoter, thereby reducing HK2-mediated glycolysis—an effect reversible by exogenous STAT3 overexpression (Zhou et al., 2021). GPR30 (a G-protein-coupled form of the estrogen receptor) is specifically expressed in chief cells. Expression of mutant Kras in these cells or administration of a high dose of H. pylori infection both lead to a reduction in the number of labeled chief cells. Upon metaplastic stimulation, chief cells are eliminated from the epithelium via a cell competition mechanism dependent on GPR30 and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK) activity; conversely, loss of GPR30 or inhibition of PDK activity effectively preserves the chief cell population (Hata et al., 2020). In summary, these strategies—targeting H. pylori metabolism (inhibition of HpG6PDH, garlic-derived H2Sn microreactors) and host pathways (STAT3/HK2, GPR30/PDK)—have shown efficacy in experimental models through unique mechanisms. Their effectiveness highlights the potential of dual-targeting therapeutic strategies, though further clinical studies are needed for validation. (Table 2, Figure 1)

Table 2. Impact of H. pylori infection on glucose metabolism: mechanisms, abnormalities, and therapeutic interventions.

4 Lactate metabolism

Lactate metabolism is a dynamic process involving multi-tissue coordination, centered on the recycling of lactate between hypoxic and oxygen-rich tissues through the “lactate shuttle.” Most glucose is converted to pyruvate via glycolysis, where lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) reduces pyruvate to lactate in an NADH-dependent manner. This regenerates NAD+ to sustain ongoing glycolysis, particularly under hypoxia, while simultaneously clearing intracellular protons (H+) to mitigate acidosis, as observed in the TME. Lactate and H+ are co-transported out of the cell via monocarboxylate transporters (MCT1 and MCT4), maintaining intracellular pH homeostasis and acidifying the extracellular space. During aerobic metabolism, lactate is oxidized back to pyruvate by LDH. Pyruvate is then converted to acetyl-CoA by pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) for entry into the TCA cycle, generating ATP for energy production. During starvation or post-exercise, lactate is transported to the liver via the Cori cycle to generate glucose (Ippolito et al., 2019; Brooks, 2020; Li et al., 2022). Additionally, lactate serves as a metabolic precursor for fatty acid synthesis and amino acid biosynthesis.

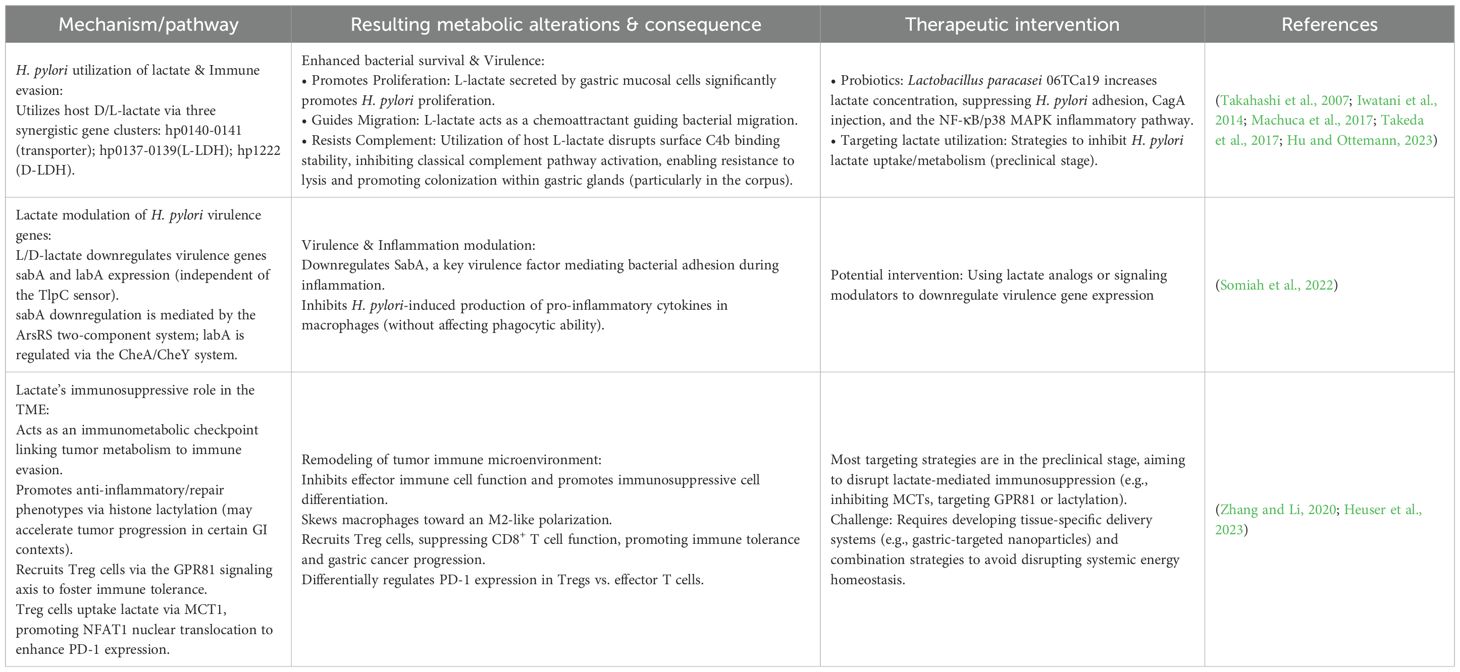

Notably, the gastric pathogen H. pylori has evolved sophisticated mechanisms to utilize lactate, enhancing its survival and virulence. H. pylori utilizes lactate through the synergistic action of three gene clusters: hp0137–0139 (L-LDH), hp1222 (D-LDH), and hp0140–0141 (lactate transporter). Specifically, hp0140–0141 mediates the transport of both D-lactate and L-lactate; hp0137–0139 mediates the NAD-dependent oxidation of L-lactate; and hp1222 mediates the NAD-independent oxidation of D/L-lactate (Iwatani et al., 2014). In a gastric organoid co-culture system, L-lactate secreted by gastric mucosal cells significantly promotes H. pylori proliferation (Takahashi et al., 2007). Furthermore, L-lactate serves as an important chemoattractant guiding bacterial migration (Machuca et al., 2017). Critically, through uptake of host-derived L-lactate, H. pylori disrupts the stability of surface C4b binding, specifically inhibiting activation of the classical complement pathway. This enables the bacterium to resist lytic effects and promotes its colonization within the gastric glands, particularly in the corpus region, identifying lactate as a key factor conferring complement resistance (Hu and Ottemann, 2023).

Both L- and D-lactate can downregulate the expression of the sabA and labA genes, though this process is independent of the lactate chemosensor TlpC. The downregulation of sabA is mediated by the ArsRS two-component system, while labA is regulated through the CheA/CheY system, indicating distinct molecular mechanisms underlying their response to lactate. Additionally, lactate can inhibit H. pylori-induced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in macrophages without affecting their phagocytic ability. Notably, SabA, a key virulence factor, mediates bacterial adhesion to host cells during inflammation (Somiah et al., 2022). In a related probiotic context, Lactobacillus paracasei 06TCa19 significantly increases lactate concentration, simultaneously suppressing H. pylori adhesion and CagA protein injection while blocking the NF-κB/p38 MAPK inflammatory signaling pathway, thereby comprehensively downregulating IL-8/RANTES gene transcription and protein synthesis (Takeda et al., 2017).

Beyond its role in bacterial pathogenesis, lactate also serves as a key immunomodulatory metabolite in the TME. It contributes to an immunosuppressive milieu by inhibiting the function of effector immune cells, promoting the differentiation of immunosuppressive cells, and participating in epigenetic modifications (Heuser et al., 2023). Its effects are both cell-type and context-dependent, establishing lactate as a critical metabolic checkpoint that links tumor metabolism with immune evasion (Heuser et al., 2023). For instance, lactate can skew macrophages toward an M2-like polarized state (Zhang and Li, 2020). Lactylation, a novel histone modification induced by lactate, has been shown to play a dual role in macrophage-mediated immune responses: it generally promotes anti-inflammatory and repair phenotypes, though in certain gastrointestinal contexts it may instead accelerate tumor progression and induce immunosuppression (Che et al., 2025). Additionally, lactate recruits regulatory T (Treg) cells via the G-protein-coupled receptor 81 (GPR81) signaling axis to foster immune tolerance. Deficiency in this pathway releases the suppression of CD8+ T cells, thereby inhibiting GC progression (Su et al., 2024). In highly glycolytic tumor microenvironments, Treg cells actively take up lactate through monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1), which promotes nuclear translocation of NFAT1 and subsequent enhancement of PD-1 expression. Conversely, PD-1 expression in effector T cells is suppressed under the same conditions (Kumagai et al., 2022).

Most lactate-targeting strategies remain preclinical, focusing on inhibiting H. pylori lactate uptake/metabolism or disrupting lactate-mediated immunosuppression in the TME (Heuser et al., 2023; Gu et al., 2025). However, as lactate is a central metabolic and signaling molecule, systemic targeting poses risks—including disrupted energy homeostasis, acidosis, or unintended immunomodulation. Future translation requires developing tissue-specific delivery systems (e.g., gastric-targeted nanoparticles) and combination strategies that selectively inhibit microbial or tumor-related lactate pathways without altering systemic physiological functions.

In summary, these findings reveal that H. pylori coordinately utilizes host-derived lactate through multiple synergistic pathways—stimulating its own growth, guiding migration, and critically disabling host immune defenses by suppressing complement-mediated lysis and pro-inflammatory signaling. This multifaceted lactate-dependent strategy facilitates its successful colonization within the protected niche of the gastric glands. Furthermore, lactate’s role as an immunometabolite in the TME adds another layer of complexity to its involvement in H. pylori-associated gastric pathogenesis and carcinogenesis (Table 3, Figure 1).

Table 3. Interaction between H. pylori and lactate metabolism: mechanisms, abnormalities, and interventions.

5 Amino acid metabolism

Amino acids are crucial organic molecules containing amino and carboxyl groups, categorized as α-, β-, γ-, or δ- amino acids based on the position of these functional groups. Among these, the 22 α-amino acids that constitute proteins are the most significant. They serve not only as fundamental building blocks for synthesizing proteins, polypeptides, and other biomolecules, but also as an energy source via oxidative pathways involving deamination and the urea cycle (Brosnan, 2000). Cellular uptake of amino acids relies on amino acid transporters (AATs). These transporters not only facilitate the transmembrane transport of amino acids but also act as sensors of amino acid concentration and initiators of nutrient signaling, and can be classified based on their substrates and mechanisms (Hediger et al., 2013). Beyond their core roles as biosynthetic precursors and energy sources, amino acids profoundly regulate key cellular processes: They activate signaling pathways like mTOR (via glutamine, arginine, leucine, etc.) to regulate protein synthesis and cell growth; modulate metabolic pathways (such as gluconeogenesis and the urea cycle) through specific amino acids (e.g., alanine, arginine); and play indispensable roles in the proliferation, activation, and function of immune cells (e.g., T cells). Deficiency in certain amino acids (e.g., tryptophan, arginine, leucine) directly impairs immune cell function (Paulusma et al., 2022; Ling et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2024). Therefore, amino acids are essential, multifunctional molecules vital for sustaining life activities, integral to core biological processes including biosynthesis, energy metabolism, signal transduction, and immune regulation.

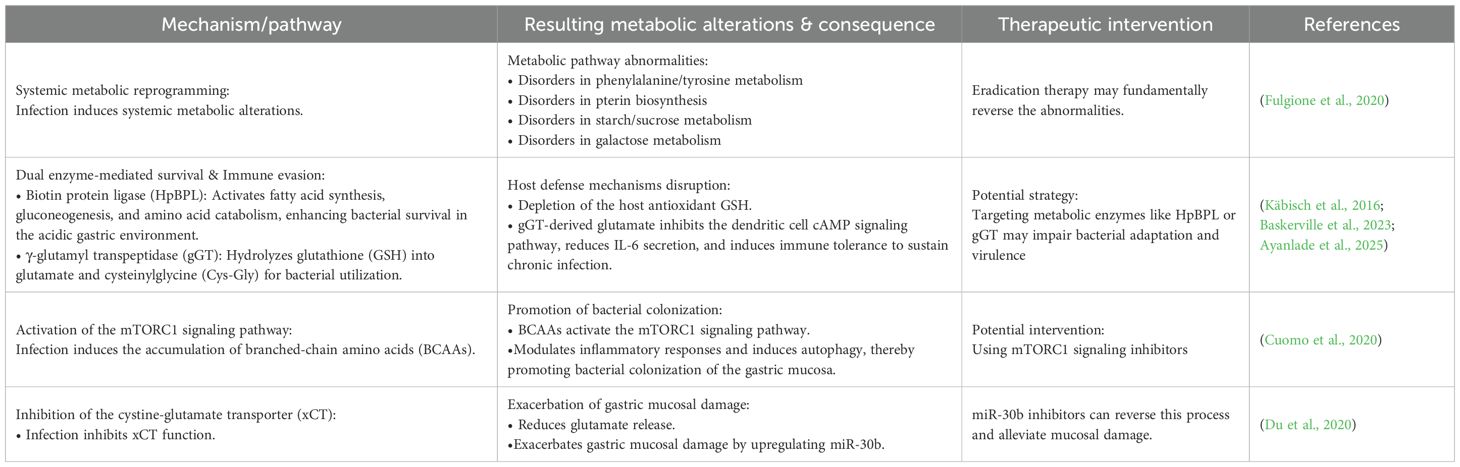

In the context of infection, H. pylori extensively disrupts host amino acid metabolism to facilitate its survival and persistence. Metabolomic analyses, such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), reveal that H. pylori infection induces systemic metabolic alterations, including abnormalities in phenylalanine/tyrosine metabolism, pterin biosynthesis, starch/sucrose metabolism, and galactose metabolism pathways (Fulgione et al., 2020). To adapt to and manipulate the gastric environment, H. pylori employs a dual enzyme-mediated mechanism: Its biotin protein ligase (HpBPL) activates fatty acid synthesis, gluconeogenesis, and amino acid catabolism, enhancing bacterial survival in the acidic gastric environment (Ayanlade et al., 2025). Meanwhile, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (gGT) hydrolyzes glutathione (GSH) to glutamate and cysteinylglycine (Cys-Gly) for internalization, leading to the depletion of host antioxidant defenses due to GSH loss (Baskerville et al., 2023). Moreover, gGT-derived glutamate inhibits the dendritic cell cAMP signaling pathway, reduces IL-6 secretion, and induces immune tolerance to sustain chronic infection (Käbisch et al., 2016).

This metabolic disorder further triggers a cascade of pathological effects: H. pylori-induced accumulation of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) activates the mTORC1 signaling pathway, modulating inflammatory responses and inducing autophagy to promote bacterial colonization of the gastric mucosa (Cuomo et al., 2020). Concurrently, infection-induced inhibition of the cystine-glutamate transporter (xCT) reduces glutamate release, exacerbating gastric mucosal damage through upregulation of miR-30b, a process reversible by miR-30b inhibitors (Du et al., 2020). In summary, H. pylori establishes chronic infection and induces tissue damage through a self-reinforcing pathogenic cycle, which integrates metabolic reprogramming (via HpBPL and gGT), immune tolerance (gGT-mediated dendritic cell suppression), and miR-30b-dependent mucosal injury (through xCT inhibition). Targeting any node within this loop—such as modulating metabolic enzymes, inhibiting miR-30b, or restoring antioxidant and immune signaling—may offer novel opportunities for disrupting chronic infection and mitigating gastric pathology (Table 4, Figure 1).

Table 4. Impact of H. pylori infection on amino acid metabolism: mechanisms, abnormalities, and interventions.

6 Conclusion and future directions

This review underscores metabolic reprogramming as a central mechanism by which H. pylori infection drives the progression from chronic inflammation to GC. The pathogen disrupts host lipid, glucose, lactate, and amino acid metabolism through virulence factors like CagA, leading to significant pathophysiological consequences. Key disruptions include elevated LDL and reduced HDL promoting extra-gastric diseases, enhanced glycolysis via pathways involving HKDC1, Lonp1, and PDK1/Akt fueling epithelial proliferation and EMT, exploitation of host lactate (mediated by genes like hp0140-0141) facilitating bacterial colonization and immune evasion, and amino acid imbalances (BCAA accumulation activating mTORC1, gGT depleting GSH) causing oxidative stress and immune tolerance. These metabolic alterations are fundamental to H. pylori pathogenesis and carcinogenesis.

The infection-induced metabolic perturbations reshape the TME, creating conditions conducive to persistence and malignancy. Metabolite accumulation (lactate) and nutrient competition suppress CD8+ T cell function and promote immunosuppressive phenotypes in macrophages and Tregs. Furthermore, gut microbiota dysbiosis, characterized by increased Helicobacter and reduced Lactobacillus, synergizes with metabolic dysregulation (like glucose imbalance) to form a vicious cycle that undermines antibiotic efficacy. Strategies like specific probiotics (L. paracasei) that increase lactate or innovative approaches such as H2Sn-loaded microreactors offer novel preventive and therapeutic avenues by targeting bacterial metabolism and virulence.

Future research must prioritize several key areas to translate these insights into clinical impact. Mechanistically, deeper exploration of the spatiotemporal dynamics of strain-specific metabolic interference and how reprogramming initiates the “inflammation-metaplasia-carcinoma” cascade is essential, including dissecting crosstalk between mitochondrial stress (Lonp1), epigenetics (GBA1 methylation), and transcriptional regulation of metabolic enzymes. Technologically, applying spatial multi-omics and developing advanced organoid-microbe co-culture models are needed to resolve in situ host-bacteria-immune metabolic interactions within the gastric niche. Translationally, efforts should focus on screening metabolic biomarkers for early diagnosis and prognosis, designing precision drug delivery systems targeting metabolism (potentially combined with immunotherapy or antibiotics), and exploring combined “metabolic intervention-microbiota regulation” strategies for prevention. Finally, understanding host heterogeneity, such as links between genetic background (paradoxical lipid profiles in Asians), environmental factors, and metabolic phenotypes, is crucial for personalized approaches. A comprehensive understanding of H. pylori-driven metabolic reprogramming will pave the way for novel “metabolism-targeted therapies” aimed at blocking gastric carcinogenesis.

Author contributions

TL: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation. XZ: Writing – review & editing, Visualization. TC: Writing – review & editing. MZ: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. WL: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by National Demonstration Pilot Project for the Inheritance and Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine–Construction project between Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine and Zhongshan Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. GZYZS2024XKZ05); University–Hospital Joint Fund Project of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (No. GZYZS2024G39); The First Batch of Social Welfare and Foundation in Zhongshan City in 2024 Research project (general project in the field of medical and health No.2024B1030); Scientific Research Project of the Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Guangdong Province (No.20261446).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdel-Razik, A., Mousa, N., Shabana, W., Refaey, M., Elhelaly, R., Elzehery, R., et al. (2018). Helicobacter pylori and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A new enigma? Helicobacter 23, e12537. doi: 10.1111/hel.12537

Arnold, M., Park, J. Y., Camargo, M. C., Lunet, N., Forman, D., and Soerjomataram, I. (2020). Is gastric cancer becoming a rare disease? A global assessment of predicted incidence trends to 2035. Gut 69, 823–829. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320234

Ayanlade, J. P., Davis, D. E., Subramanian, S., Dranow, D. M., Lorimer, D. D., Hammerson, B., et al. (2025). Co-crystal structure of Helicobacter pylori biotin protein ligase with biotinyl-5-ATP. Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 81, 11–18. doi: 10.1107/s2053230x24012056

Baj, J., Forma, A., Sitarz, M., Portincasa, P., Garruti, G., Krasowska, D., et al. (2020). Helicobacter pylori virulence factors-mechanisms of bacterial pathogenicity in the gastric microenvironment. Cells 10, 27. doi: 10.3390/cells10010027

Baskerville, M. J., Kovalyova, Y., Mejías-Luque, R., Gerhard, M., and Hatzios, S. K. (2023). Isotope tracing reveals bacterial catabolism of host-derived glutathione during Helicobacter pylori infection. PLoS Pathog. 19, e1011526. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1011526

Beloribi-Djefaflia, S., Vasseur, S., and Guillaumond, F. (2016). Lipid metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells. Oncogenesis 5, e189. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2015.49

Boroughs, L. K. and DeBerardinis, R. J. (2015). Metabolic pathways promoting cancer cell survival and growth. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 351–359. doi: 10.1038/ncb3124

Brooks, G. A. (2020). Lactate as a fulcrum of metabolism. Redox Biol. 35, 101454. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101454

Brosnan, J. T. (2000). Glutamate, at the interface between amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism. J. Nutr. 130, 988s–990s. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.4.988S

Buzás, G. M. (2014). Metabolic consequences of Helicobacter pylori infection and eradication. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 5226–5234. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5226

Che, T. H., Nguyen, T. C., Ngo, D. T. T., Nguyen, H. T., Vo, K. T., Ngo, X. M., et al. (2022). High prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection among school-aged children in ho chi minh city, vietNam. Int. J. Public Health 67, 1605354. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2022.1605354

Che, X., Zhang, Y., Chen, X., Xie, G., Li, J., Xu, C., et al. (2025). The lactylation-macrophage interplay: implications for gastrointestinal disease therapeutics. Front. Immunol. 16, 1608115. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1608115

Chen, J., Cui, L., Lu, S., and Xu, S. (2024). Amino acid metabolism in tumor biology and therapy. Cell Death Dis. 15, 42. doi: 10.1038/s41419-024-06435-w

Chen, Y. C., Malfertheiner, P., Yu, H. T., Kuo, C. L., Chang, Y. Y., Meng, F. T., et al. (2024). Global prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection and incidence of gastric cancer between 1980 and 2022. Gastroenterology 166, 605–619. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.12.022

Chen, X., Peng, R., Peng, D., Liu, D., and Li, R. (2024). Helicobacter pylori infection exacerbates metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease through lipid metabolic pathways: a transcriptomic study. J. Transl. Med. 22, 701. doi: 10.1186/s12967-024-05506-y

Chen, L., Peng, J., Wang, Y., Jiang, H., Wang, W., Dai, J., et al. (2020). Fenofibrate-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolic reprogramming reversal: the anti-tumor effects in gastric carcinoma cells mediated by the PPAR pathway. Am. J. Transl. Res. 12, 428–446.

Cuomo, P., Papaianni, M., Sansone, C., Iannelli, A., Iannelli, D., Medaglia, C., et al. (2020). An in vitro model to investigate the role of helicobacter pylori in type 2 diabetes, obesity, alzheimer’s disease and cardiometabolic disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 8369. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218369

Doulberis, M., Tsilimpotis, D., Polyzos, S. A., Vardaka, E., Salahi-Niri, A., Yadegar, A., et al. (2025). Unraveling the pathogenetic overlap of Helicobacter pylori and metabolic syndrome-related Porphyromonas gingivalis: Gingipains at the crossroads and as common denominator. Microbiol. Res. 299, 128255. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2025.128255

Du, J., Li, X. H., Liu, F., Li, W. Q., Gong, Z. C., and Li, Y. J. (2020). Role of the outer inflammatory protein A/cystine-glutamate transporter pathway in gastric mucosal injury induced by helicobacter pylori. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 11, e00178. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000178

Duan, Y., Xu, Y., Dou, Y., and Xu, D. (2025). Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: mechanisms and new perspectives. J. Hematol. Oncol. 18, 10. doi: 10.1186/s13045-024-01654-2

Fang, Y., Fan, C., Li, Y., and Xie, H. (2024). The influence of Helicobacter pylori infection on acute coronary syndrome and lipid metabolism in the Chinese ethnicity. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 14, 1437425. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1437425

Fang, Z., Zhang, W., Wang, H., Zhang, C., Li, J., Chen, W., et al. (2024). Helicobacter pylori promotes gastric cancer progression by activating the TGF-β/Smad2/EMT pathway through HKDC1. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 81, 453. doi: 10.1007/s00018-024-05491-x

Fulgione, A., Papaianni, M., Cuomo, P., Paris, D., Romano, M., Tuccillo, C., et al. (2020). Interaction between MyD88, TIRAP and IL1RL1 against Helicobacter pylori infection. Sci. Rep. 10, 15831. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72974-9

Gao, S., Song, D., Liu, Y., Yan, H., and Chen, X. (2020). Helicobacter pylori cagA protein attenuates 5-fu sensitivity of gastric cancer cells through upregulating cellular glucose metabolism. Onco Targets Ther. 13, 6339–6349. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S230875

Gu, X. Y., Yang, J. L., Lai, R., Zhou, Z. J., Tang, D., Hu, L., et al. (2025). Impact of lactate on immune cell function in the tumor microenvironment: mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Front. Immunol. 16, 1563303. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1563303

Hata, M., Kinoshita, H., Hayakawa, Y., Konishi, M., Tsuboi, M., Oya, Y., et al. (2020). GPR30-expressing gastric chief cells do not dedifferentiate but are eliminated via PDK-dependent cell competition during development of metaplasia. Gastroenterology 158, 1650–1666.e1615. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.046

Hay, N. (2016). Reprogramming glucose metabolism in cancer: can it be exploited for cancer therapy? Nat. Rev. Cancer 16, 635–649. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.77

Hediger, M. A., Clémençon, B., Burrier, R. E., and Bruford, E. A. (2013). The ABCs of membrane transporters in health and disease (SLC series): introduction. Mol. Aspects Med. 34, 95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.12.009

Heuser, C., Renner, K., Kreutz, M., and Gattinoni, L. (2023). Targeting lactate metabolism for cancer immunotherapy - a matter of precision. Semin. Cancer Biol. 88, 32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.12.001

Hu, S. and Ottemann, K. M. (2023). Helicobacter pylori initiates successful gastric colonization by utilizing L-lactate to promote complement resistance. Nat. Commun. 14, 1695. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-37160-1

Ippolito, L., Morandi, A., Giannoni, E., and Chiarugi, P. (2019). Lactate: A metabolic driver in the tumour landscape. Trends Biochem. Sci. 44, 153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2018.10.011

Iwai, N., Okuda, T., Oka, K., Hara, T., Inada, Y., Tsuji, T., et al. (2019). Helicobacter pylori eradication increases the serum high density lipoprotein cholesterol level in the infected patients with chronic gastritis: A single-center observational study. PLoS One 14, e0221349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221349

Iwatani, S., Nagashima, H., Reddy, R., Shiota, S., Graham, D. Y., and Yamaoka, Y. (2014). Identification of the genes that contribute to lactate utilization in Helicobacter pylori. PLoS One 9, e103506. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103506

Jin, H. R., Wang, J., Wang, Z. J., Xi, M. J., Xia, B. H., Deng, K., et al. (2023). Lipid metabolic reprogramming in tumor microenvironment: from mechanisms to therapeutics. J. Hematol. Oncol. 16, 103. doi: 10.1186/s13045-023-01498-2

Käbisch, R., Semper, R. P., Wüstner, S., Gerhard, M., and Mejías-Luque, R. (2016). Helicobacter pylori γ-glutamyltranspeptidase induces tolerogenic human dendritic cells by activation of glutamate receptors. J. Immunol. 196, 4246–4252. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501062

King, C. C. and Obonyo, M. (2015). Helicobacter pylori modulates host cell survival regulation through the serine-threonine kinase, 3-phosphoinositide dependent kinase 1 (PDK-1). BMC Microbiol. 15, 222. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0543-0

Kumagai, S., Koyama, S., Itahashi, K., Tanegashima, T., Lin, Y. T., Togashi, Y., et al. (2022). Lactic acid promotes PD-1 expression in regulatory T cells in highly glycolytic tumor microenvironments. Cancer Cell 40, 201–218.e209. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.01.001

Lee, D. Y., Jung, D. E., Yu, S. S., Lee, Y. S., Choi, B. K., and Lee, Y. C. (2017). Regulation of SIRT3 signal related metabolic reprogramming in gastric cancer by Helicobacter pylori oncoprotein CagA. Oncotarget 8, 78365–78378. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18695

Li, N., Chen, S., Xu, X., Wang, H., Zheng, P., Fei, X., et al. (2024). Single-cell transcriptomic profiling uncovers cellular complexity and microenvironment in gastric tumorigenesis associated with Helicobacter pylori. J. Adv. Res. 74, 471–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2024.10.012

Li, Y., Choi, H., Leung, K., Jiang, F., Graham, D. Y., and Leung, W. K. (2023). Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection between 1980 and 2022: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8, 553–564. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00070-5

Li, C., Lu, C., Gong, L., Liu, J., Kan, C., Zheng, H., et al. (2022). SHP2/SPI1axis promotes glycolysis and the inflammatory response of macrophages in Helicobacter pylori-induced pediatric gastritis. Helicobacter 27, e12895. doi: 10.1111/hel.12895

Li, X., Yang, Y., Zhang, B., Lin, X., Fu, X., An, Y., et al. (2022). Lactate metabolism in human health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7, 305. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01151-3

Li, Z. and Zhang, H. (2016). Reprogramming of glucose, fatty acid and amino acid metabolism for cancer progression. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 73, 377–392. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2070-4

Liang, P., Li, Z., Chen, Z., Chen, Z., Jin, T., He, F., et al. (2025). Metabolic reprogramming of glycolysis, lipids, and amino acids in tumors: impact on CD8+ T cell function and targeted therapeutic strategies. FASEB J. 39, e70520. doi: 10.1096/fj.202403019R

Lin, J., Rao, D., Zhang, M., and Gao, Q. (2024). Metabolic reprogramming in the tumor microenvironment of liver cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 17, 6. doi: 10.1186/s13045-024-01527-8

Ling, Z. N., Jiang, Y. F., Ru, J. N., Lu, J. H., Ding, B., and Wu, J. (2023). Amino acid metabolism in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8, 345. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01569-3

Liu, C., Zhu, X., Pu, J., Zou, Z., Zhou, L., and Zhu, X. (2025). Helicobacter pylori infection and apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A1 ratio: a cross-sectional study. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 15, 1582843. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2025.1582843

Luo, B., Wang, M., Hou, N., Hu, X., Jia, G., Qin, X., et al. (2016). ATP-dependent lon protease contributes to helicobacter pylori-induced gastric carcinogenesis. Neoplasia 18, 242–252. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2016.03.001

Machuca, M. A., Johnson, K. S., Liu, Y. C., Steer, D. L., Ottemann, K. M., and Roujeinikova, A. (2017). Helicobacter pylori chemoreceptor TlpC mediates chemotaxis to lactate. Sci. Rep. 7, 14089. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14372-2

Malfertheiner, P., Camargo, M. C., El-Omar, E., Liou, J. M., Peek, R., Schulz, C., et al. (2023). Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 9, 19. doi: 10.1038/s41572-023-00431-8

Melone, M. A. B., Valentino, A., Margarucci, S., Galderisi, U., Giordano, A., and Peluso, G. (2018). The carnitine system and cancer metabolic plasticity. Cell Death Dis. 9, 228. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0313-7

Mi, C., Zhao, Y., Ren, L., and Zhang, D. (2022). Inhibition of MDFI attenuates proliferation and glycolysis of Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric cancer cells by inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Cell Biol. Int. 46, 2198–2206. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11907

Modi, N., Chen, Y., Dong, X., Hu, X., Lau, G. W., Wilson, K. T., et al. (2024). BRD4 regulates glycolysis-dependent nos2 expression in macrophages upon H pylori infection. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 292–308.e291. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2023.10.001

Munir, R., Lisec, J., Swinnen, J. V., and Zaidi, N. (2019). Lipid metabolism in cancer cells under metabolic stress. Br. J. Cancer 120, 1090–1098. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0451-4

Niemelä, S., Karttunen, T., Korhonen, T., Läärä, E., Karttunen, R., Ikäheimo, M., et al. (1996). Could Helicobacter pylori infection increase the risk of coronary heart disease by modifying serum lipid concentrations? Heart 75, 573–575. doi: 10.1136/hrt.75.6.573

Obre, E. and Rossignol, R. (2015). Emerging concepts in bioenergetics and cancer research: metabolic flexibility, coupling, symbiosis, switch, oxidative tumors, metabolic remodeling, signaling and bioenergetic therapy. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 59, 167–181. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.12.008

Ortiz-Ramírez, P., Hernández-Ochoa, B., Ortega-Cuellar, D., González-Valdez, A., Martínez-Rosas, V., Morales-Luna, L., et al. (2022). Biochemical and kinetic characterization of the glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from helicobacter pylori strain 29CaP. Microorganisms 10, 1359. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10071359

Paulusma, C. C., Lamers, W. H., Broer, S., and van de Graaf, S. F. J. (2022). Amino acid metabolism, transport and signalling in the liver revisited. Biochem. Pharmacol. 201, 115074. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115074

Peng, C., Xu, X., He, Z., Li, N., Ouyang, Y., Zhu, Y., et al. (2021). Helicobacter pylori infection worsens impaired glucose regulation in high-fat diet mice in association with an altered gut microbiome and metabolome. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 105, 2081–2095. doi: 10.1007/s00253-021-11165-6

Pincock, S. (2005). Nobel prize winners robin warren and barry marshall. Lancet 366, 1429. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67587-3

Rosli, N. A., Al-Maleki, A. R., Loke, M. F., Tay, S. T., Rofiee, M. S., Teh, L. K., et al. (2024). Exposure of Helicobacter pylori to clarithromycin in vitro resulting in the development of resistance and triggers metabolic reprogramming associated with virulence and pathogenicity. PLoS One 19, e0298434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0298434

Salvatori, S., Marafini, I., Laudisi, F., Monteleone, G., and Stolfi, C. (2023). Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: pathogenetic mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 2895. doi: 10.3390/ijms24032895

Sharndama, H. C. and Mba, I. E. (2022). Helicobacter pylori: an up-to-date overview on the virulence and pathogenesis mechanisms. Braz. J. Microbiol. 53, 33–50. doi: 10.1007/s42770-021-00675-0

Shen, C., Liu, H., Chen, Y., Liu, M., Wang, Q., Liu, J., et al. (2025). Helicobacter pylori induces GBA1 demethylation to inhibit ferroptosis in gastric cancer. Mol. Cell Biochem. 480, 1845–1863. doi: 10.1007/s11010-024-05105-x

Somiah, T., Gebremariam, H. G., Zuo, F., Smirnova, K., and Jonsson, A. B. (2022). Lactate causes downregulation of Helicobacter pylori adhesin genes sabA and labA while dampening the production of proinflammatory cytokines. Sci. Rep. 12, 20064. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-24311-5

Song, Z., Xiaoli, A. M., and Yang, F. (2018). Regulation and metabolic significance of de novo lipogenesis in adipose tissues. Nutrients 10, 1383. doi: 10.3390/nu10101383

Su, J., Mao, X., Wang, L., Chen, Z., Wang, W., Zhao, C., et al. (2024). Lactate/GPR81 recruits regulatory T cells by modulating CX3CL1 to promote immune resistance in a highly glycolytic gastric cancer. Oncoimmunology 13, 2320951. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2024.2320951

Takahashi, T., Matsumoto, T., Nakamura, M., Matsui, H., Tsuchimoto, K., and Yamada, H. (2007). L-lactic acid secreted from gastric mucosal cells enhances growth of Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 12, 532–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00524.x

Takeda, S., Igoshi, K., Tsend-Ayush, C., Oyunsuren, T., Sakata, R., Koga, Y., et al. (2017). Lactobacillus paracasei strain 06TCa19 suppresses inflammatory chemokine induced by Helicobacter pylori in human gastric epithelial cells. Hum. Cell 30, 258–266. doi: 10.1007/s13577-017-0172-z

Tan, Y., Lin, K., Zhao, Y., Wu, Q., Chen, D., Wang, J., et al. (2018). Adipocytes fuel gastric cancer omental metastasis via PITPNC1-mediated fatty acid metabolic reprogramming. Theranostics 8, 5452–5468. doi: 10.7150/thno.28219

Tharp, K. M., Kersten, K., Maller, O., Timblin, G. A., Stashko, C., Canale, F. P., et al. (2024). Tumor-associated macrophages restrict CD8(+) T cell function through collagen deposition and metabolic reprogramming of the breast cancer microenvironment. Nat. Cancer 5, 1045–1062. doi: 10.1038/s43018-024-00775-4

Tran, S. C., Bryant, K. N., and Cover, T. L. (2024). The Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island as a determinant of gastric cancer risk. Gut Microbes 16, 2314201. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2314201

Tsai, C. J., Herrera-Goepfert, R., Tibshirani, R. J., Yang, S., Mohar, A., Guarner, J., et al. (2006). Changes of gene expression in gastric preneoplasia following Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 15, 272–280. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0632

Vijayvergiya, R. and Vadivelu, R. (2015). Role of Helicobacter pylori infection in pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. World J. Cardiol. 7, 134–143. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v7.i3.134

Wang, Z., Wang, W., Gong, R., Yao, H., Fan, M., Zeng, J., et al. (2022). Eradication of Helicobacter pylori alleviates lipid metabolism deterioration: a large-cohort propensity score-matched analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 21, 34. doi: 10.1186/s12944-022-01639-5

Wang, X., Zhou, N., Gao, X. J., Zhu, Z., Sun, M., Wang, Q., et al. (2025). Selective G6PDH inactivation for Helicobacter pylori eradication with transformed polysulfide. Sci. China Life Sci. 68, 1158–1173. doi: 10.1007/s11427-024-2775-3

Warren, J. R. and Marshall, B. (1983). Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet 1, 1273–1275.

Watanabe, J., Hamasaki, M., and Kotani, K. (2021). The effect of helicobacter pylori eradication on lipid levels: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 10, 904. doi: 10.3390/jcm10050904

Xiao, Q. Y., Wang, R. L., Wu, H. J., Kuang, W. B., Meng, W. W., and Cheng, Z. (2024). Effect of helicobacter pylori infection on glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism and inflammatory cytokines in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients. J. Multidiscip Healthc 17, 1127–1135. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S453429

Yang, L., Chu, Z., Liu, M., Zou, Q., Li, J., Liu, Q., et al. (2023). Amino acid metabolism in immune cells: essential regulators of the effector functions, and promising opportunities to enhance cancer immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 16, 59. doi: 10.1186/s13045-023-01453-1

Yoshikawa, H., Aida, K., Mori, A., Muto, S., and Fukuda, T. (2007). Involvement of Helicobacter pylori infection and impaired glucose metabolism in the increase of brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity. Helicobacter 12, 559–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00523.x

Zhang, L. and Li, S. (2020). Lactic acid promotes macrophage polarization through MCT-HIF1α signaling in gastric cancer. Exp. Cell Res. 388, 111846. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2020.111846

Zhang, H., Li, S., Wang, D., Liu, S., Xiao, T., Gu, W., et al. (2024). Metabolic reprogramming and immune evasion: the interplay in the tumor microenvironment. biomark. Res. 12, 96. doi: 10.1186/s40364-024-00646-1

Zhao, H., Jiang, R., Feng, Z., Wang, X., and Zhang, C. (2023). Transcription factor LHX9 (LIM Homeobox 9) enhances pyruvate kinase PKM2 activity to induce glycolytic metabolic reprogramming in cancer stem cells, promoting gastric cancer progression. J. Transl. Med. 21, 833. doi: 10.1186/s12967-023-04658-7

Zhao, L., Liu, Y., Zhang, S., Wei, L., Cheng, H., Wang, J., et al. (2022). Impacts and mechanisms of metabolic reprogramming of tumor microenvironment for immunotherapy in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 13, 378. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-04821-w

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, metabolic reprogramming, lipid metabolism, glucose metabolism, lactate metabolism, amino acid metabolism, gastric carcinogenesis

Citation: Liu T, Zhao X, Cai T, Li W and Zhang M (2025) Metabolic reprogramming in Helicobacter pylori infection: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 15:1678044. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2025.1678044

Received: 04 August 2025; Accepted: 22 September 2025;

Published: 13 October 2025.

Edited by:

Elba Mónica Vermeulen, Instituto de Biología y Medicina Experimental, ArgentinaReviewed by:

Romina Jimena Fernandez-Brando, Academia Nacional de Medicina, ArgentinaLei Peng, Peking University, China

Copyright © 2025 Liu, Zhao, Cai, Li and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Minglin Zhang, bWluZ2xpbnpoYW5nMTk5M0AxNjMuY29t; Wei Li, cmlpMTUyeGlhbGlAb3V0bG9vay5jb20=

Tong Liu

Tong Liu Xuelin Zhao2

Xuelin Zhao2 Minglin Zhang

Minglin Zhang