- 1Departamento de Ciencias de la Comunicación, Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja, Loja, Ecuador

- 2Dirección de Investigación, Responsabilidad Social & Innovación, Universidad Privada del Norte, Trujillo, Peru

- 3Centro de Estudios en Industrias Culturales [Cultural Industries Centre] - CONICET, Universidad Nacional de Quilmes, Bernal, Buenos Aires, Argentina

- 4National University of General San Martín, San Martín, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Digital citizenship implies people's participation in managing their rights and civic engagements. However, definitions clash with reality due to institutional conditions, perceptions, and limited information literacy skills. In this context, it is of interest to determine the perceptions, forms of intervention and treatment of the concept of digital citizenship from the perspectives of citizens and the media in the Andean countries (Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru). The methodology is qualitative and quantitative with a descriptive scope. The research techniques used are a survey, semi-structured interviews and content analysis. 497 people from the Andean countries responded to an online questionnaire between 16 June and 23 July 2023. Participants were selected on the basis of non-probabilistic sampling. The semi-structured interviews were conducted between 15 and 30 May 2023 through Zoom; and the sample of newspaper articles corresponds to quotas. It is concluded that the media and social networks are effective tools for citizen participation, but it is suggested that the agendas to be revised to include the voices of the protagonists. There is a predominance of an instrumental conception, and social networks have been valued as means of communication. Andean inhabitants show resistance to the defense of rights or the management of social change, which could be fostered through a conscious and broad exercise of digital citizenship.

1 Introduction

Digital citizenship involves skills and values for the responsible use of information and communication technologies (ICTs). For the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, digital citizenship is the set of competences that “empower individuals to access, retrieve, understand, evaluate, use and share information and media content, using various tools ethically and effectively in order to participate and engage in personal, professional and social activities” (Working Group on Citizenship Digital, 2020). And digital citizen is “that individual, whether or not a citizen of another community or State, who exercises all or part of his or her political and social rights through the Internet, independently or through membership in a virtual community” (Robles, 2009, p. 55).

From the concept of digital citizenship proposed by Ribble and Bailey (2007), focused on technological aspects and digital competencies, the definition of Emejulu and McGregor (2019) is derived, which highlights social justice and alternative technology as the axis of online citizenship practices. Today, presence in the digital world includes emancipations and collective identities that are manifested through social media platforms, and influence public opinion.

Under any conceptual perspective, achieving online citizenship involves literacy, critical thinking and skills to manage information and privacy online, as well as competences to execute effective and ethical communication (Ohler, 2012; Selwyn, 2014; Fraillon et al., 2019). However, digital citizenship does not replace the concept of citizenship, it refers to a set of practices through which civic activities are performed in digital environments (Yue et al., 2019; Runchina et al., 2022). In general, it describes a more understanding and inclusive community that participates meaningfully in the digital society (Mossberger, 2010; Ribble, 2015), but requires access and skills, i.e., that all people are able to use ICTs and the Internet to bring about impact or change in collectivities (Warschauer, 2003; Rheingold, 2008).

According to Jenkins et al. (2009), digital citizenship involves active participation in the circulation of media content, and is fundamental to an informed democracy. It has been pointed out that democracy is unviable without free and pluralistic public communication. In this context, active participation acquires a crucial relevance to strengthen freedom of expression. It is even an opportunity for the protagonism of young people “by providing them with new spaces and means to express and share their opinions, going beyond the referential frameworks of the family and school environment” (Lebrusán et al., 2022, p. 1).

One of the indispensable factors to consolidate digital citizenship is the participation of people in the management of their needs, in this purpose, the media and virtual platforms serve the circulation of opinions, play an essential role for people to intervene in public debates and thus foster digital citizenship, that is, there are political and social motivations, the first “have the purpose of solving the problems of a community or group, while the social ones refer to the predisposition to get involved in discussions about specific public issues and the need to obtain information, express opinions and persuade” (Contreras et al., 2023, p. 93).

Training in and for citizenship is a mission that begins at school, and is enhanced through access to the Internet, which is categorized as a basic human right because of its transformative nature and as an avenue for freedom of expression (United Nations General Assembly, 2011). The right to browse the Internet “is a condition for participation in contemporary times, for the full exercise of citizenship, for broad and transparent access and expression to information and the means for its production, exchange and social participation” (Almeida and Silva, 2014, p. 1240).

In this context, it highlights the importance of digital citizenship from a shared commitment between school and family, where the contributions of the International Society for Technology in Education (Ribble, 2015, 2021) are guiding, pointing out nine elements that help educators to understand the variables that constitute the formation of digital citizenship and provide a guide for its approach in schools. The elements proposed by Ribble, which are grouped into the categories of respect, educate and protect are: Digital Access, Digital Commerce, Digital Communication, Digital Literacy, Digital Etiquette, Digital Law, Digital Rights and Responsibilities, Digital Health and Wellness, and Digital Security. Addressing these components helps teachers to understand the diversity of digital citizenship, discuss it and prepare students to exercise their citizenship fully.

The human right to communication enshrines the principles of access, social participation, universality, diversity and equity (MacBride, 1980, in Segura et al., 2023, p. 8), which are valid offline and online. Thus, digital rights are the rights to access, use, create and publish by digital means; and, to access and use electronic devices and telecommunications networks (Bizberge and Segura, 2020). To guarantee participation, access to the Internet is necessary, however, several episodes show that those who have the possibilities to get involved in the digital world contribute little or even erode public debates. Improving relations between citizens and between them and governments depends on the appropriation of the Internet, despite the risks that arise in these environments (Mossberger et al., 2007).

However, these rights can be obstructed because digital platforms entail inconsistencies, they appear egalitarian but are hierarchical; almost exclusively corporate, but serves public values; They look neutral but their architecture carries ideological values; its effects seem local while its reach and impact is global; It aims to reverse the top-down government logic in which citizens are empowered, however, it does so through a highly centralized structure that is opaque to users (Van Dijck et al., 2018). That is why, in a scenario of globalization and expansion of digital networks, the development of new technologies cannot be left to market forces. Its sociopolitical repercussions will depend on digital inclusion policies that counteract the notion of citizenship that reduces its interpellation to mere subjects of consumption (De Charras et al., 2013).

Therefore, it is important to identify people's involvement in the challenges of local development and, at the same time, to evaluate the impact on the construction of a critical citizenship and public sphere (Scolari et al., 2018). It is also worth recovering the idea of digital media and networks as spaces of recognition for communicational citizenship oriented toward the exercise and enjoyment of rights.

An analysis is carried out in the Andean Community of Nations, whose acronym is CAN (2023), made up of four countries: Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, because they share culture, history and have formed a political and economic bloc since 1969, as well as experiencing similar moments in the discussion of Internet regulation and the protection of digital rights (Dinegro, 2022, p. 11).

Tackling the challenges of developing digital citizenship involves empowering people and communities, especially those that have been historically marginalized. In the Andean region, where digital divides and deep socio-economic inequalities exist, access to technology plays a liberating role in promoting social justice. Therefore, digital citizenship research offers opportunities to address disparities, promote citizen participation, equal access to information and digital inclusion of marginalized groups. It helps to build a fairer and more equitable society in which all citizens have the opportunity to benefit from digital technologies and participate fully in democratic and social life.

On the basis of the background information presented, the purpose of the research is to determine the perceptions, implications and forms of intervention of citizens in the media and the media's approach to the concept of digital citizenship. The research questions are: (1) What are the appreciations, implications and forms of intervention of citizens in the Andean countries with respect to digital citizenship? (2) How does the media address the concept and practices of digital citizenship?

2 Methodology

The research is deployed from the socio-critical paradigm, which combines quantitative and qualitative methodologies (Ortiz, 2015), or integrationist, as it enables, legitimizes and uses these orientations (Batthyány and Cabrera, 2011). The study is assumed under the integration of quantitative and qualitative aspects, the main articulating element of the mixed methodology (Creswell and Plano, 2018), which resolves the meaning and possibilities of what Creswell (2015) baptized as the third research paradigm.

From the quantitative, the descriptive scope, “aims to define, classify, catalog or characterize the object of study” (Chorro, 2020), after measuring variables, describing them as they manifest themselves in reality (Hernández-Sampieri et al., 2014), produces data in “people's own words” (Taylor and Bodgan, 1984, p. 20). Qualitatively, the typology is phenomenological (Vasilachis de Gialdino, 2006), using testimonies and intersubjective human experiences (Ortiz, 2015). A mixed design is followed, of type VIII “sequential, in stages. One stage one approach, the next the other. Each stage strengthens the previous one” (Pereira, 2011, p. 20). There are three units of analysis, (1) citizens from the four CAN countries, (2) citizenship-related experts from the CAN, and (3) online journalistic articles from the CAN, with an emphasis promoting digital citizenship.

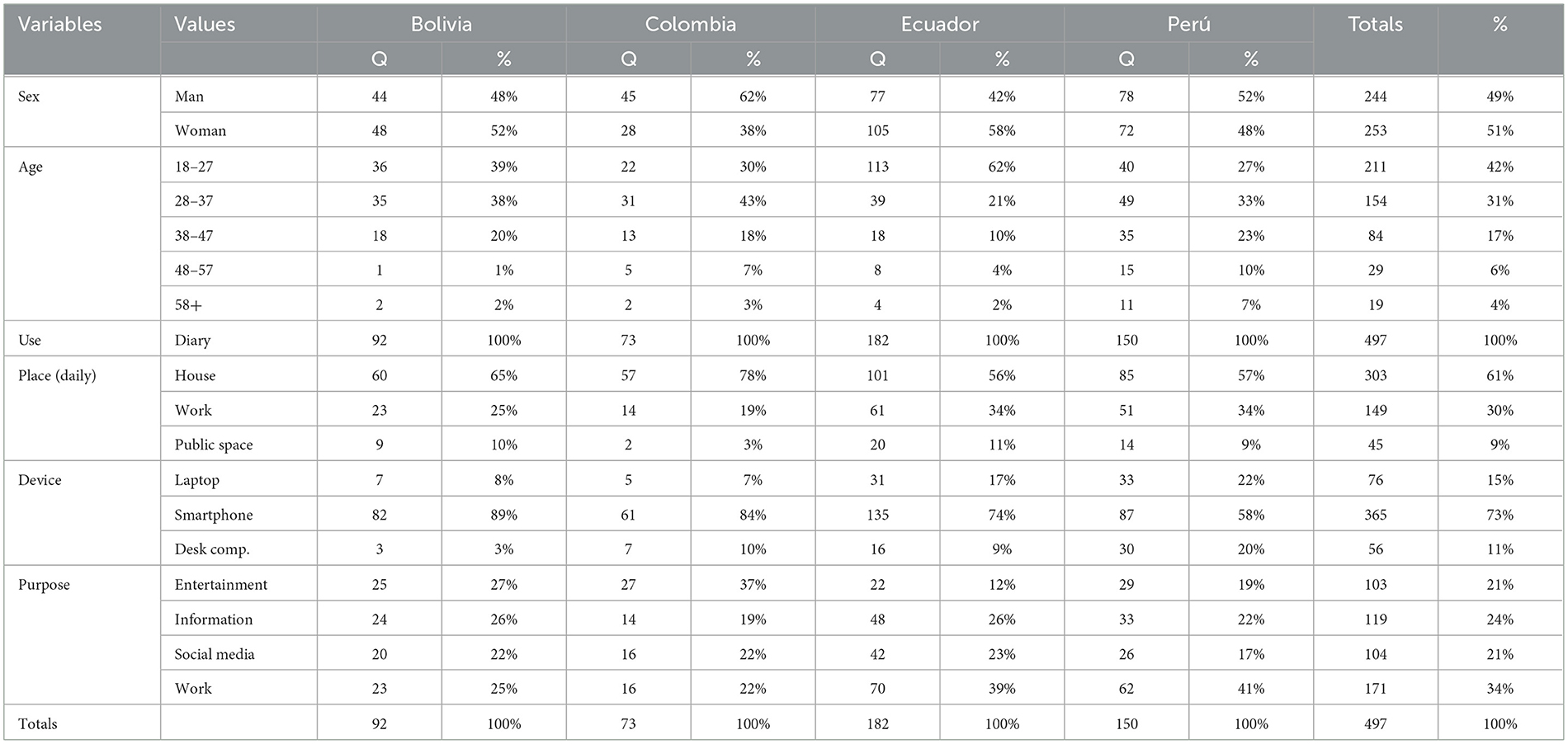

The study involved 497 people from the Andean countries (Table 1), who responded to an online questionnaire published on Google Forms, a useful tool for opinion surveys (Arias, 2020), between 16 June and 23 July 2023. The surveys are consistent with the quantitative approach, aimed at people who provide their perceptions and show behaviors (Arias and Covinos, 2021). The selection of participants responds to a non-probabilistic sampling by convenience due to their availability, and because it optimizes time “according to the specific circumstances that surround both the researcher and the subjects or groups investigated” (Sandoval, 2002, p. 124). The dissemination of the survey occurs through the snowball or chain sampling procedure, thanks to contacts with colleagues in Bogotá, Lima, Piura, La Paz, Quito and Loja, who then refer the instrument to third parties (Meneses et al., 2019; Pérez et al., 2020), who then refer the instrument to others, until reaching about half a thousand people.

Those who respond are citizens of legal age, carry out regular digital activity and are willing to collaborate in the study. It was avoided that they be authors or collaborators in similar research, and that they have ties of blood or friendship with the project team. The resulting data are processed in the statistical software SPSS, version 22.

The survey was developed based on the comparative analysis of measurement scales by Fernández-Prados et al. (2021). There is no international standard, but models that assess social contexts, engagement and participation are presented, as in Choi (2016), which groups “large categories that construct digital citizenship: ethics, media and information literacy, participation/commitment and critical resistance” (p. 565). Specifically, the model proposed by Choi et al. (2017) is considered, composed of 26 items on a Likert-type scale with seven options ranging from completely disagree (1) to completely agree (7). The items are grouped into five factors, 1. Political activism on the Internet, 2. Technical skills, 3. Local/global awareness, 4. Critical approach, 5. Communicative activism. When the instrument was designed, its validity was assumed, but internal consistency reliability testing was used. The reliability coefficient of the measurement scale is high, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.94.

According to gender, participants are 49% male and 51% female. All access the Internet daily, mostly from home (61%) and preferably via their smartphones (73%), with the main purpose of working (34%). Ages range from 18 to 75, with an average age of 32.

The semi-structured interviews were carried out between May 15 and 30, 2023 via Zoom, to determine the experts' opinions on the exercise of digital citizenship. The experts are communicators, university professors or researchers related to the topic of study. The interviews were proposed as conversations where people make sense of reality, respecting concrete choice guidelines consistent with the focus of the study (Benites and Villanueva, 2015). The questions asked are What is digital citizenship? Is digital citizenship important for democracy? How to strengthen digital citizenship? How to involve people in the concept of digital citizenship? The profiles are below.

• Interviewee 1. Bolivian. Communicator and sociologist. Researches on rural areas. University lecturer.

• Interviewee 2. Bolivian. Communicator and university lecturer. Expert in radio and TV.

• Interviewee 3. Bolivian. PhD in humanities for development. Research on political, intercultural communication and journalism.

• 4. Colombian. Anthropologist and PhD in communication. Researches on communication and culture.

• Interviewee 5. Colombian. University lecturer. Researches in science, cyberculture, and techno-society.

• Interviewee 6. Ecuadorian. PhD in communication. Research on media skills for citizenship.

• Interviewee 7. Ecuadorian. Communicator and journalist. Member of the LATAM Network of Young Journalists.

• Interviewee 8. Peruvian. Journalist. Teacher. Expert in sound and audiovisual production.

• Interviewee 9. Peruvian. Social communicator. Radio host and university lecturer.

• Interviewee 10. Peruvian. Journalist, runs a digital portal. Radio and TV producer.

The sample of news articles corresponds to quotas, subject to defined strata and lacking randomness. The quota was set at eight, in total, two digital media per country, representing 56 news articles. They are the online versions of newspapers and digital native media, they were selected because they offer their content without payment restrictions, cover events across the geography of their nations and are at the top of the Similar Web ranking, and incomplete and subscription versions were excluded. The reviewed pieces were published between May and June 2023, and were located through the composite week method (Hansen et al., 2002).

Frequent characteristics of news stories that promote digital citizenship are (a) Emphasis on responsibility and accountability, (b) Focus on inclusion and diversity, (c) Encouraging citizen participation, (d) Promoting media literacy, (e) Veracity and precision of the information (Chadwick et al., 2016; López-Jacobo et al., 2023). The perspectives of digital citizenship information are related to (a) Cultural capital, (b) Democratic culture, (c) Human rights, and (d) Digital inclusion (Richardson and Milovidov, 2019; Working Group on Citizenship Digital, 2020; Lebrusán et al., 2022).

To obtain data from journalistic pieces, the quantitative technique of content analysis was used, optimal for systematically describing formal and semantic elements of messages in order to draw reasonable inferences (Colle, 2011). A coding sheet was constructed to display quantifiable categories and subcategories of analysis, allowing the counting of specific aspects, present or not, of a variable. In analyzing the data, the focus and narrative routes were followed. In the surveys and content analysis, the phases proposed by Arispe et al. (2020) were followed: provision of software, quality control, evaluation of validity and reliability, exploratory and descriptive analysis, and representation of the data.

3 Results

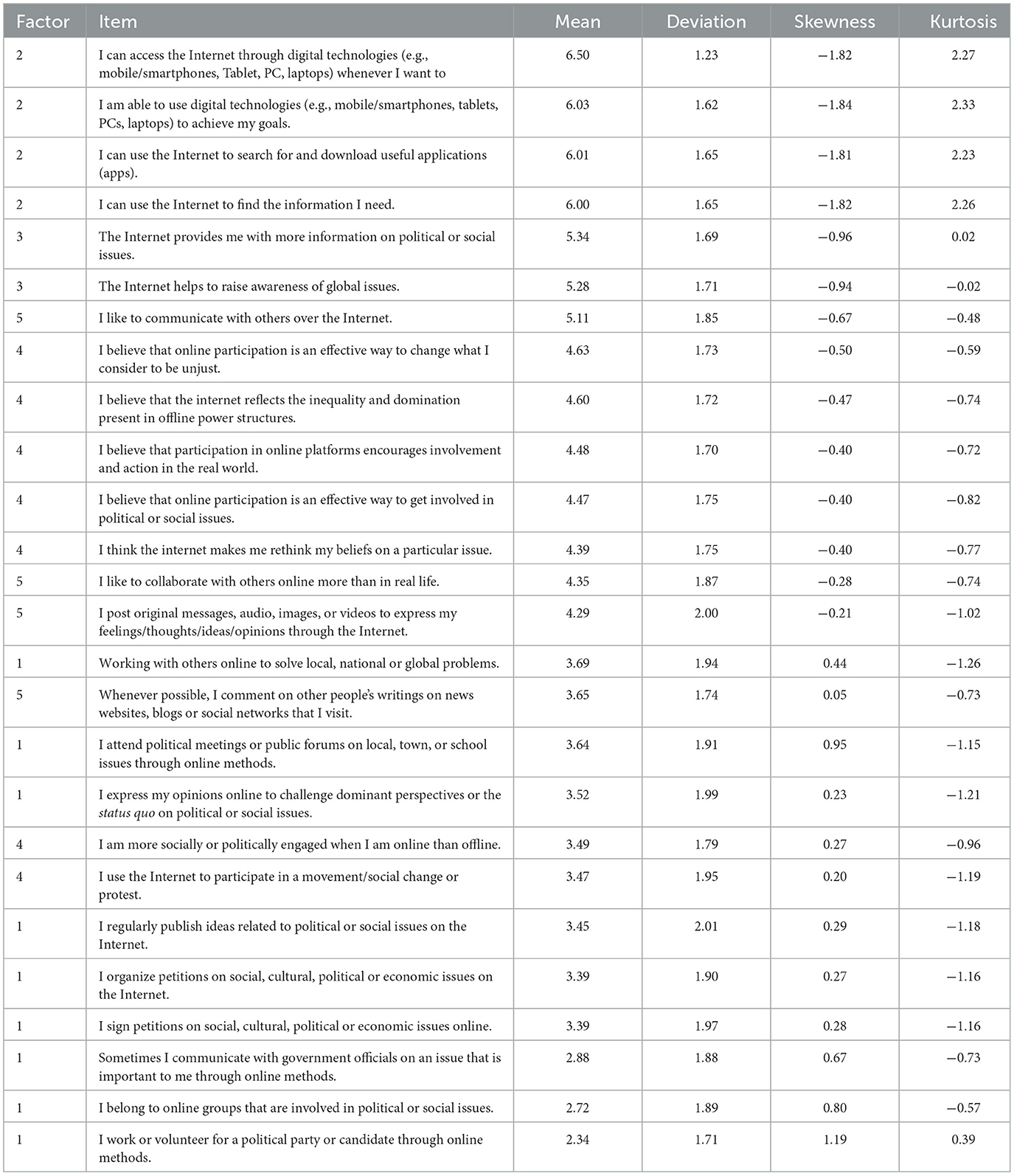

The results of the survey are summarized in Table 2, ranking the surveyed items in their final values from highest to lowest according to arithmetic means. The strength of the data is confirmed by other statistics such as standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis. Thus, the items related to technical skills with respect to digital citizenship show higher and better measures of central tendency and distribution. There is evidence of instrumental skills as opposed to other characteristics of digital competences (knowledge and attitudes), and weak critical approaches and community actions (political activism on the Internet), in the assessments of the inhabitants of Andean countries. In terms of technical skills that would facilitate digital citizenship, the following stand out: (1) access to the Internet via digital technologies, (2) ability to use digital technologies, (3) being able to use the Internet for searches and utility downloads, (4) being able to use the Internet to find data.

Regarding knowledge and attitudes about digital in connection to citizenship, respondents acknowledge that (1) the Internet provides them with more information on political or social issues, (2) it helps raise awareness of global issues, and (3) they like to communicate with others online. More specifically, including (4) they believe that online participation is effective in overcoming injustices, (5) they believe that the Internet reflects the inequality and domination present in power structures, and (6) they believe that online participation encourages real involvement and action.

However, already in practical terms, on digital political activism itself, participants admit very little to (1) regularly posting political or social ideas on the Internet, (2) organizing social, cultural, political, etc. petitions, (3) signing petitions of the same kind. Even less (4) communicating online with officials on issues of importance to them and (5) being part of online civic communities.

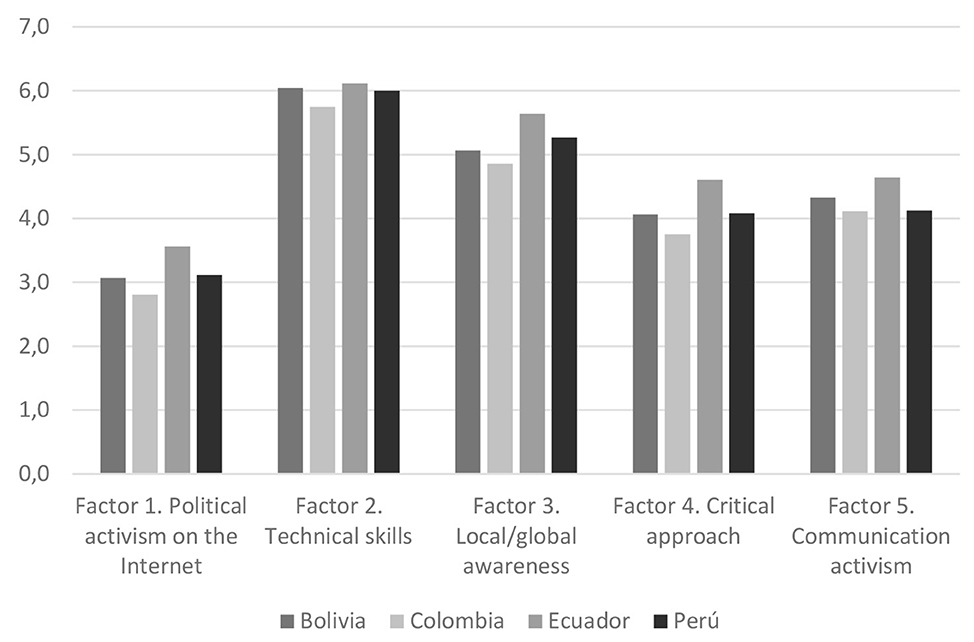

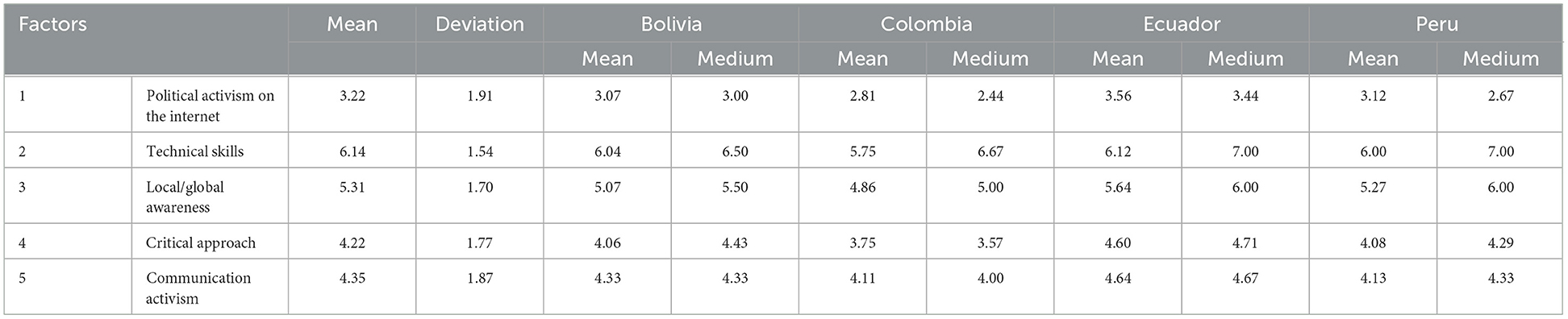

Figure 1 shows the medians of the factors by country. Table 2 gives a numerical breakdown of the medians. Means in combination with the medians give an objective reading by country. Although similar trends appear, Colombia stands out as showing lower means and medians as shown in the figures in Table 3. Ecuador and Bolivia have equal medians in global awareness and technical skills; in the other factors they show close measures, although the numbers of respondents differ by 90 participants. Peru is approaching, discretely, either below or above but very close to the total values.

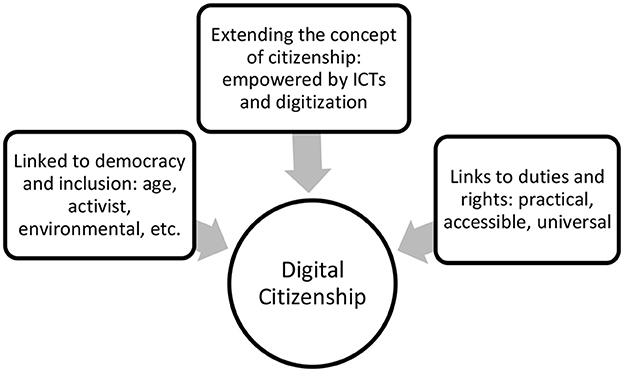

As a result of the interviews, there are approximations, first on the concept of digital citizenship, in key words are in Figure 2. Some see features on the very being of democracies and commitments to inclusion (age, activist, gender, environmental). Digital citizenship is “an unavoidable dimension of the new forms of democracy, with respect for the rights of others that they nurture. Digital citizenship is linked, not exclusively, to the new generations” (K. Herrera, personal communication, 17 May 2023). “It involves emerging citizenships, social movements, cyberfeminism, network society, care for the environment” (I. Jiménez, personal communication, 19 May 2023).

Others conceptualize it in its tensions with respect to the macro concept of citizenship, although the use of technologies and digitalization have enhanced the scope of citizenship practice. Digital citizenship “has to do with the digital transformation that goes hand in hand with the possibilities generated by ICTs” (D. Rivera, personal communication, 20 May 2023), it implies “the exercise of politics through the Internet, where we can expand to global citizenship” (A. Alemán, personal communication, 15 May 2023), it is noted that it is “weaving networks directly without intermediaries” (K. Crespo, personal communication, 22 May 2023). But, “it is not different from physical citizenship. Today, in the digital world there is a dispute over the exercise of citizenship, but it is still citizenship” (D. García, personal communication, 18 May 2023).

A third concept is related to the exercise of duties and rights, in more practical, accessible and universal terms. Digital citizenship “should provide the opportunity to fulfill obligations and exercise rights in a direct, transparent and less onerous way in all spaces, especially public spaces” (I. Reque, personal communication, 16 May 2023) because when barriers occur it is “like a country to which we belong, but we do not know and, therefore, we do not exercise duties or rights related to this concept” (A. Cornejo, personal communication, 26 May 2023).

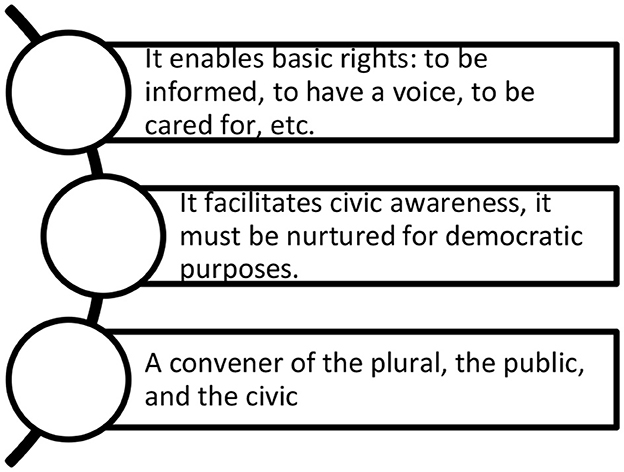

For the experts, secondly, digital citizenship is important for democracy in that (1) it enables the exercise of rights, basically the right to be informed, to have a voice and to be listened to, (2) it facilitates active awareness for democratic purposes, (3) it brings together the plural, political and civic aspects of a society. These evaluations are present in Figure 3. Supporting these ideas, in fact, the interviewees reflected that “it allows citizens to exercise their rights. For example, be informed, raise opinions and improve attention to your needs” (I. Reque, personal communication, May 16, 2023). Through digital citizenship “an active consciousness is developed. But, if we promote an uninformed culture, we make democracy impossible” (K. Crespo, personal communication, May 22, 2023). “Talking about citizenship implies plurality, political culture and civic culture” (I. Jiménez, personal communication, 19 May 2023), where “we can find a space to be part of” (A. Alemán, personal communication, 15 May 2023).

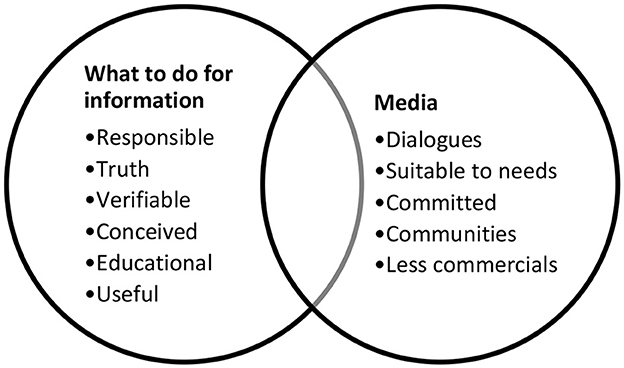

The interviewees were asked how to strengthen digital citizenship. A first group of opinions are linked to the informative, responsible and more filtering characteristics. In order to strengthen digital citizenship, it is necessary to start with “the verification of news, especially in times of crisis” (A. Alemán, personal communication, 15 May 2023), “think carefully about the content, about what I write, about what I comment” (J. León, personal communication, 30 May 2023). “You cannot create citizenship with an uninformed base. As long as people are not educated to identify threats, you cannot build a digital citizenship that can supervise and lead to democracy” (K. Crespo, personal communication, 22 May 2023).

It extends to the need for a media shift in response to citizen engagement, instead of commercial aspects “in this new ecosystem the media have forgotten to converse with the audience, that is why the audience started to follow social networks and digital platforms, because there they see a space for dialogue” (D. Rivera, personal communication, 20 May 2023). The media “could adapt their tools to the needs of citizens. However, there is a very cold commercial vision. There is probably openness and adaptation in alternative community media, where there is more responsibility” (A. Cornejo, personal communication, 26 May 2023), and, as a result, “small media should continue to focus on citizens” (D. García, personal communication, 18 May 2023). A succinct account of the testimonies is given in Figure 4.

When asked how to involve people in the concept of digital citizenship, the answers turn toward education, from the family. People are involved “through critical education to discern what we have in front of us, to distinguish the true from the false” (A. Alemán, personal communication, 15 May 2023). “Educate from the family, include a new pedagogy, create values” (K. Herrera, personal communication, 17 May 2023). “The main challenge we have is literacy” (D. Rivera, personal communication, 20 May 2023).

A group of responses will be refined toward shared values from others, and from oneself. Expression in this sense is “to qualify participation, to form responsible, supportive, inclusive citizenship. Currently there is an explosion of participation, but freedom of expression is not guaranteed” (K. Herrera, personal communication, 17 May 2023). “Preparation is fundamental, you have to think well, construct each content well” (J. León, personal communication, 30 May 2023).

The public entity is mentioned in its controls over circulating digital information as a factor to involve citizens. “The State should train to be aware of what type of content should be consumed. If we do not have literate users, they will continue consuming low-quality information” (D. Rivera, personal communication, May 20, 2023). “States would have to pay more attention to the implications of these platforms on democracy, on public discussions, and on excess information” (D. García, personal communication, May 18, 2023).

In this involvement, the active participation of the media is also called for, within a critical and ethical framework. “(They) must commit themselves to a north in information in general, and the responsibilities it entails. Preserve a critical view, with spaces for social interaction” (A. Cornejo, personal communication, 26 May 2023), likewise “try to ensure that the digital media have certainties. It is a challenge of our time, to take advantage of technological advances, but in accordance with truth and ethics” (I. Reque, personal communication, 16 May 2023).

It is recalled that “traditional media found in digital platforms an opportunity to expand content. Now the user, through their device, can interact with them” (H. Urpeque, personal communication, 29 May 2023), Mass media “can rely on WhatsApp or TikTok groups to show speeches and opinions. Also, Twitter (now X) as a fundamental space for participation” (A. Alemán, personal communication, 15 May 2023).

Getting involved with digital citizenship, in the voice of experts, requires a careful look at the risks. “We are entering a new social rupture with ICT, especially with the Internet that opened the possibility of extending rights and duties, but there are also many risks that we have to mitigate” (K. Herrera, personal communication, May 17, 2023), for this reason “we need involved digital citizens, aware of their duties and rights” (D. Rivera, personal communication, May 20, 2023).

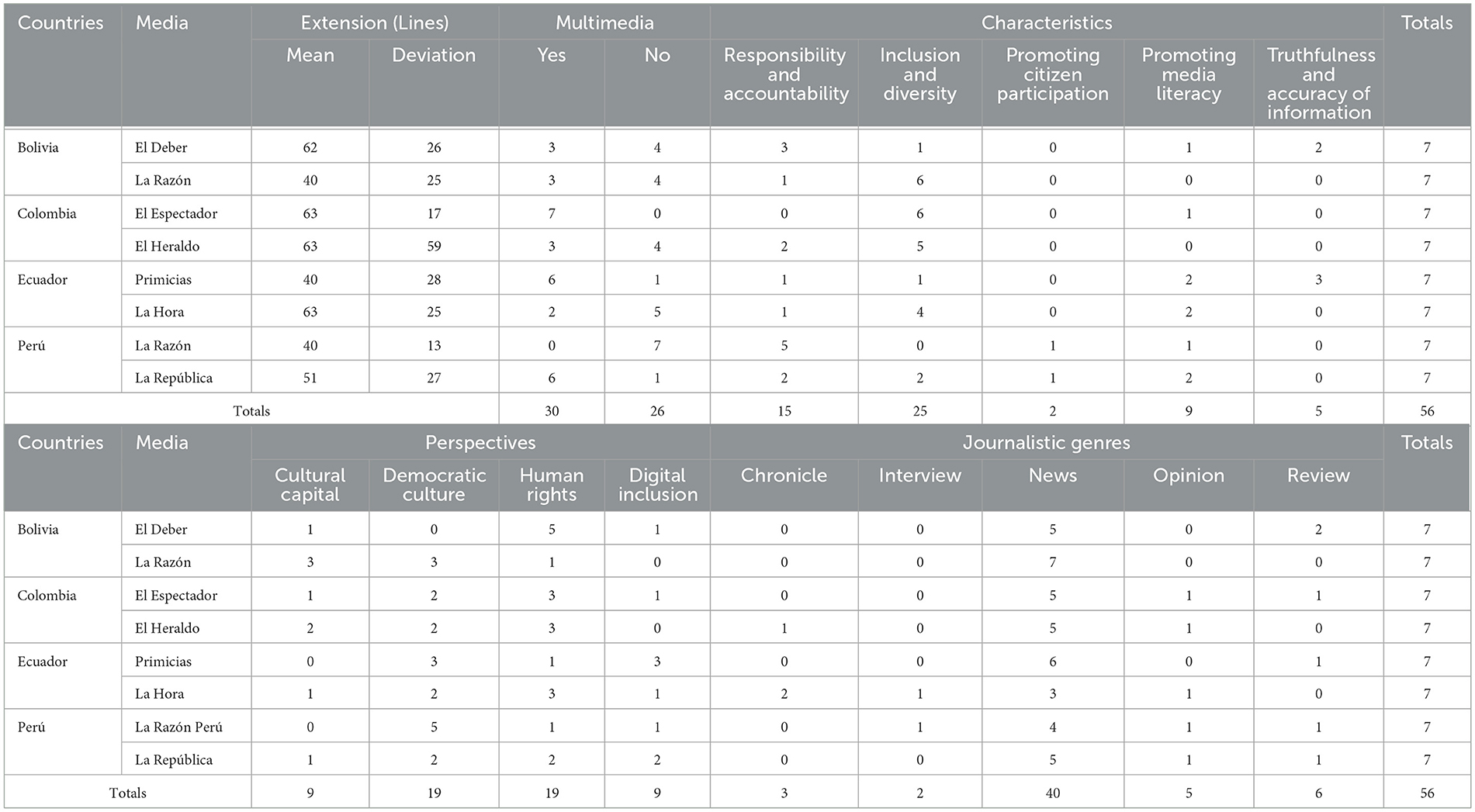

Table 4 compiles the results of the content analysis of digital citizenship information from the pieces published in each country. First of all, the average length, measured in lines, is 53, which for digital media is the classic news structure, which allows for details and contexts, and it is stated that the most frequent informative genre is news in 71% of the pieces analyzed. Nearly 60% are supported by multimedia resources.

At a specific level, the characteristics of digital citizenship that stand out the most are inclusion and diversity, in 45% of the publications, followed by responsibility and accountability, with 27%, with the promotion of media literacy being further away (16%), veracity and precision of information (9%), and promotion of citizen participation (3.5%).

The perspectives attributable to citizen communication present in the information that stand out most are democratic culture (34%) and human rights (34%). Cultural capital and digital inclusion are in second place with 16% each. The media analyzed in Peru positively emphasize the perspective of democratic culture, with half of the 14 pieces showing evidence of this. This same perspective is very little explored in the Bolivian media, only three of its articles do so; however, the human rights perspective is the most present in the CAN media.

4 Discussion and conclusions

Digital citizenship is the current expression of coexistence around social institutions; it demands a set of skills to participate responsibly, safely and ethically in virtual environments. Citizens can make the most of the opportunities offered by technology, which is why the aim is to strengthen digital skills through formal and informal media and information literacy mechanisms. The importance of the articulated role of families, schools and governments in promoting digital citizenship is recognized. Educational institutions should “provide knowledge in relation to the use of technological tools not only for the mediation of learning, but also for inclusion in digital citizenship” (Torres-Gastelú et al., 2019, p. 42).

The survey results (Table 2) indicate that people have competences to use ICTs, but the variables of understanding, social impact and direct participation in digital environments receive the lowest responses of agreement, with respondents noting their disagreement with criteria describing practices in advocacy or social change management. Statistical measures show the dispersion of responses.

The results also confirm other studies, such as in Lozano-Díaz and Fernández-Prados (2019) where they assess digital citizenship by means of the Choi et al. (2017) scale to test the profile, dimensions and needs of digital citizenship characterizing a sample of 250 participants. In the end, it was shown that participants possess high technical skills, but poor critical approaches and political activism.

Respondents show that the instrumental uses of ICTs allow them a first approach to online citizenship, but the development of citizenship and democracy “cannot be thought of in isolation from the phenomena of restructuring and transformation of the social order. It is at the intersection of economic, social, political and cultural coordinates, where a nascent digital citizenship has made an appearance” (Alva de la Selva, 2020, p. 101). Effective democracy and an equitable economic model that seeks to reduce social conflicts can be achieved by listening to citizens in order to agree on ways to reduce poverty, social inequality and violence; it is a matter of motivating citizen participation in public affairs. The premise to advance in the indicated direction is to participate, to get involved in the political, social, cultural agendas, etc. of the Andean countries in order to exercise rights and fulfill civic obligations; only in this way will it be possible to achieve digital citizenship.

The more information and opinions are shared, the more tolerance is promoted and the more the efforts of minority groups are understood and integrated. Attempts to minimize dissenting voices undermine peaceful coexistence.

The media can become permanent spaces of accountability, because that is what the laws provide for, but above all because they have the conditions to receive the manifestations of neighbors, management reports of public servants, collect expressions from associations and collectives, which in concrete terms will achieve participation, diversity and plurality (Suing, 2023, p. 1).

Given the new dimensions of government, citizenship and digital processes, it is urgent to promote media training to guarantee the rights and responsibilities of the governed and the governed. The first step is to address, not ignore, that the goal of innovation is to promote human wellbeing.

Based on the results, it can be noted that digital media are a tool to promote citizen participation. The initiatives that should be taken in the media to promote citizen participation involve a review of content agendas, including the voices of citizens in broadcasts so that they can present their positions and generate debates to feed public opinion.

Barriers that hinder digital participation are, according to interviewees, the digital divide and misinformation. Toward a fully connected citizenry, advantages and disadvantages are evaluated, mainly knowledge, social connections and support networks (Boyd, 2014), because digital platforms, which facilitate social relations, also generate risks.

Interviewees agree that training, media and information literacy education, as well as the creation of instructional content, are necessary initiatives to promote citizen participation and strengthen digital citizenship. The ease with which unverified information is spread online leads to misinformation, which undermines trust in the media, therefore, digital citizenship poses challenges in terms of trust and security, users must manage their data, protect themselves against cyber threats and understand the implications of their actions (Van Dijck, 2013; Pennycook et al., 2020).

As in other researching works, this study analyzed people's attitudes toward digital citizenship in order to, among other reasons, improve the use of technologies, and confirms that the process of appropriation of digital citizenship is still a pending task (Rendón et al., 2023), and even more so in governments that are not very open, or with governance problems. It also was found a predominance of the conception of social networks as digital media—they are not, but in practice citizens use them as such, although there are privacy and personal data protection dangers.

The “platformisation” of the Internet generates a number of challenges that cover different aspects such as the market dominance of some providers, the responsibility of intermediaries, the promotion of diversity in digital environments and data ownership derived from people's use of services in public and private spheres, among others. These concerns have returned the issue of communication policies to the public agenda in Latin America. However, debates on internet regulation in the region reveal a strong distrust, both from the corporate sector and from citizens, regarding the transparency and effectiveness of the role of the state in guaranteeing rights (Bizberge et al., 2023). In this sense, the analysis of internet regulation for the exercise of collective rights emerges as a line for future research.

Other lines of research are to complement this study with the support of more qualitative methodology instruments to review trends in media publications, and to compare the results with other countries. Despite addressing an issue of the utmost importance for democracy from a mixed approach, there are recognized limitations. One is that the study focuses its analysis on the CAN countries, which, although valid, does not make its results generalizable. Another limitation lies in the typologies chosen; there are options to explore with other techniques and instruments. A third limitation is the restriction of units of analysis, which are not the only ones linked to digital citizenship. It is up to other researchers to overcome the gaps, and to enrich the spectrum by incorporating complementary methodological routes and involving more actors.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study involving humans was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research on Human Beings—Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (CEISH399 UTPL), dated 16th September 2021. The study was conducted in accordance with all institutional and national legislation and requirements. The participants provided written informed consent for participation in the study and for the publication of any identifying information included in the article.

Author contributions

AS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. L-RA-L: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The article arises from the project “Fomento de la ciudadanía digital en los países andinos a través de los medios de comunicación” PROY_PROY_ARTIC_CC_2022_3655, sponsored by the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (Ecuador).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Almeida, F., and Silva, M. (2014). The curriculum as a right and digital culture. Rev. Curric. 12, 1233–1247.

Alva de la Selva, A. (2020). Scenarios and challenges of digital citizenship in Mexico. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Polít. Soc. 65, 81–105. doi: 10.22201/fcpys.2448492xe.2020.238.68337

Arias, J. (2020). Métodos de investigación on line. Herramientas digitales para recolectar datos. Enfoques [Online research methods. Digital tools for data collection]. Arequipa: Ciencia y Sociedad.

Arias, J. L., and Covinos, M. (2021). Diseño y metodología de investigación [Research design and methodology]. Arequipa: Enfoques Consulting EIRL.

Arispe, C. M., Yangali, J. S., Guerrero, M. A., Rivera, O., Acuña, L. A., and Arellano, C. (2020). La investigación científica. Una aproximación para los estudios de posgrado [Scientific research. An approach for postgraduate studies]. Guayaquil: Universidad Internacional del Ecuador.

Batthyány, K., and Cabrera, M. (2011). Metodología de la investigación en ciencias sociales. Apuntes para un curso inicial [Research methodology in the social sciences. Notes for an initial course]. Montevideo: Universidad de la República.

Benites, S. H., and Villanueva, L. (2015). Retroceder investigando ¡nunca! Rendirse con la tesis ¡Jamás! Metodología de la investigación en comunicación social. [Backtrack on research - never! Give up on the thesis - never! Methodology of social communication research]. Lima: Fondo Editorial Cultura Peruana.

Bizberge, A., Mastrini, G., and Gómez, R. (2023). Discussing internet platform policy and regulation in Latin America. J. Dig. Media Policy 14, 135–148. doi: 10.1386/jdmp_00118_2

Bizberge, A., and Segura, S. (2020). Digital rights during the COVID-19 pandemic in Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. Rev. Comun. 19, 61–85. doi: 10.26441/RC19.2-2020-A4

Boyd, D. (2014). It's Complicated: the Social Lives of Networked Teens. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press .

CAN (2023). Who are we?. Available online at: https://goo.su/5Ogzb (accessed October 17, 2023).

Chadwick, A., Dennis, J., and Smith, A. P. (2016). “Politics in the age of hybrid media: power, systems, and media logics,” in The Routledge Companion to Social Media and Politics, eds A. Bruns, G. Enli, E. Skogerbø, A. Olof, and C. Christensen (London: Routledge), 56–73.

Choi, M., Glassman, M., and Cristol, D. (2017). What it means to be a citizen in the internet age: development of a reliable and valid digital citizenship scale. Comp. Educ. 107, 100–112. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.01.002

Choi, M. A. (2016). Concept analysis of digital citizenship for democratic citizenship education in the internet age. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 44, 565–607. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2016.1210549

Chorro, L. (2020). Descriptive Statistics. Available online at: https://goo.su/tbRy9BS (accessed October 17, 2023).

Colle, R. (2011). El análisis de contenido de las comunicaciones [The content analysis of communications]. Tenerife: Sociedad Latina de Comunicación Social.

Contreras, C., Rivas, J., Franco, R., Gómez-Plata, M., and Luengo Kanacri, B. P. (2023). Digital media and school civic engagement: a parallel mediation model. Comunicar 31, 91–102. doi: 10.3916/C75-2023-07

Creswell, J. W., and Plano, V. L. (2018). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

De Charras, D., Lozano, L., and Rossi, D. (2013). “Citizenship(s) and the right(s) to communicate,” in Las políticas de comunicación en el siglo XXI. Nuevos y viejos desafíos, eds G. Mastrini, A. Bizberge, and D. de Charras (Buenos Aires: La Crujía), 26–33.

Dinegro, A. (2022). El desafío de regular las plataformas en Perú [The challenge of regulating platforms in Peru]. Lima: Fundación Friedrich Ebert-Perú.

Emejulu, A., and McGregor, C. (2019). Towards a radical digital citizenship in digital education. Crit. Stud. Educ. 60, 131–147. doi: 10.1080/17508487.2016.1234494

Fernández-Prados, J. S., Lozano-Díaz, A., and Ainz-Galende, A. (2021). Measuring digital citizenship: a comparative. Anal. Inf. 8:18. doi: 10.3390/informatics8010018

Fraillon, J., Ainley, J., Schulz, W., Friedman, T., and Duckworth, D. (2019). Preparing for Life in a Digital World: IEA International Computer and Information Literacy Study 2018 International Report. Berlin: Springer.

Hansen, A., Cottle, S., Negrine, R., and Newbold, C. (2002). Mass Communication Research Methods. New York, NY: MacMillan.

Hernández-Sampieri, R., Fernández-Collado, C., and Baptista-Lucio, P. (2014). Research Methodology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Jenkins, H., Purushotma, R., Weigel, M., Clinton, K., and Robison, A. (2009). Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lebrusán, I., Larrañaga, K. P., and Monguí Monsalve, M. M. (2022). Digitalisation as an opportunity for citizenship development in children and adolescents. Polít. Soc. 59, 1–15. doi: 10.5209/poso.81906

López-Jacobo, D. R., Angulo-Armenta, J., Mortis-Lozoya, S. V., and Torres-Gastelú, C. A. (2023). Level of digital citizenship among young Mexican university students. Form. Univ. 16, 63–72. doi: 10.4067/s0718-50062023000300063

Lozano-Díaz, A., and Fernández-Prados, J. (2019). Towards an education for critical and active digital citizenship in universities. Rev. Latinoam. Tecnol. Educ. 18, 175–187. doi: 10.17398/1695-288X.18.1.175

MacBride, S. (1980). Communication and Society Today and Tomorrow, Many Voices One World, Towards a New More Just and More Efficient World Information and Communication Order. UNESCO. Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000372754 (accessed October 17, 2023).

Meneses, J., Rodríguez, D., and Valeri, S. (2019). Investigación educativa: una competencia profesional para la intervención [Educational research: a professional competence for intervention]. Catalunya: Editorial UOC.

Mossberger, K. (2010). “Toward digital citizenship: addressing inequality in the information age,” in Routledge Handbook of Internet Politics, ed P. N. Howard (Milton Park, Abingdon: Taylor and Francis), 173–185.

Mossberger, K., Tolbert, C., and McNeal, R. (2007). Digital Citizenship: The Internet, Society, and Participation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ortiz, A. (2015). Enfoques y métodos de investigacion en ciencias sociales y humanas [Research approaches and methods in the social and human sciences]. Bogotá: Ediciones de la U.

Pennycook, G., Bear, A, Collins, E., and Rand, D. (2020). The implied truth effect: attaching warnings to a subset of fake news headlines increases perceived accuracy of headlines without warnings. Manage. Sci. 66, 4944–4957. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2019.3478

Pereira, Z. (2011). Mixed-method designs in educational research: a concrete experience. Rev. Electrón. Educ. XV, 15–29.

Pérez, L., Pérez, R., and Seca, M. (2020). Metodología de la investigación científica [Cientific investigation methodology]. Buenos Aires: Editorial Maipue.

Rendón, J., Angulo, J., and Torres, C. (2023). Attitudes towards digital citizenship in university students in southern Sonora, Mexico. Apertura 15, 70–83. doi: 10.32870/Ap.v15n1.2309

Rheingold, H. (2008). “Using participatory media and public voice to encourage civic engagement,” in Civic Life Online: Learning How Digital Media Can Engage Youth, ed W. L. Bennet (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press), 97–118.

Ribble, M. (2015). Digital Citizenship in Schools: Nine Elements all Students Should Know. 3rd Edn. Washington, DC: International Society for Technology in Education.

Ribble, M. (2021). Essential Elements of Digital Citizenship. In Digital Citizenship and Media Literacy. Washington, DC: International Society for Technology in Education.

Ribble, M., and Bailey, G. (2007). Digital Citizenship in Schools. Washington, DC: International Society for Technology in Education.

Richardson, J. E, and Milovidov (2019). Digital citizenship education handbook: being online, well-being online, and rights online. Namur: Council of Europe.

Robles, J. (2009). Ciudadanía digital: introducción a un nuevo concepto de ciudadano [Digital citizenship: introduction to a new concept of citizen]. Catalunya: UOC.

Runchina, C., Fauth, F., Sánchez-Caball,é, A., and González-Martínez, J. (2022). New media literacies and transmedia learning… Do we really have the conditions to make the leap? An analysis from the context of two Italian licei classici. Soc. Sci. 11:32. doi: 10.3390/socsci11020032

Sandoval, C. (2002). Investigación cualitativa. Programa de especialización en teoría, métodos y técnicas de investigación social [Qualitative research. Specialisation programme in theory, methods and techniques of social research]. Bogotá: Arfo Editores.

Scolari, C., Masanet, J., Guerrero-Pico, M., and Estables, J. (2018). Transmedia literacy in the new media ecology: teens' transmedia skills and informal learning strategies. Prof. Inf. 27, 801–812. doi: 10.3145/epi.2018.jul.09

Segura, M., Fernández, C., and Longo, V. (2023). How Do We Study Communicational, Cultural and Digital Inequalities? RAICCED. Available online at: https://bit.ly/3SotXKv (accessed October 17, 2023).

Selwyn, N. (2014). Digital Technology and the Contemporary University: Degrees of Digitization. London: Routledge.

Suing, A. (2023). Renovar la comunicación desde los gobiernos locales [Renewing communication from local governments]. Loja: Zenodo.

Taylor, J., and Bodgan, R. (1984). Introducción a los métodos cualitativos de investigación. La búsqueda de significados [Introduction to qualitative research methods. The search for meaning]. Barcelona: Paidos Ibérica S.A.

Torres-Gastelú, C., Cordero-Guzmán, D., Soto-Ortíz, J., and Mory-Alvarado, A. (2019). Influence of factors on the manifestation of digital citizenship. Rev. Prisma Soc. 26, 27–49.

United Nations General Assembly (2011). Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression, Frank La Rue. OHCHR. Available online at: https://bit.ly/3uynFQu (accessed October 17, 2023).

Van Dijck, J. (2013). The Culture of connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Dijck, J., Poell, T., and De Waal, M. (2018). The Platform Society as a Contested Concept. Oxford University Press.

Vasilachis de Gialdino, I. (2006). Estrategias de investigación cualitativa [Qualitative research strategies]. Barcelona: Editorial Gedisa S.A.

Warschauer, M. (2003). Technology and Social Inclusion: Rethinking the Digital Divide. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Working Group on Citizenship Digital (2020). Digital Citizenship Strategy for an Information and Knowledge Society. Presidency of the Republic. Available online at: https://tinyurl.com/yz48dfee (accessed October 17, 2023).

Keywords: digital citizenship, media literacy, human rights, internet, media, participation

Citation: Suing A, Alarcon-Llontop L-R and Bizberge A (2024) Appreciations and practices of digital citizenship in the Andean community. Front. Commun. 9:1336528. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1336528

Received: 10 November 2023; Accepted: 19 February 2024;

Published: 07 March 2024.

Edited by:

Vincenzo Auriemma, University of Salerno, ItalyReviewed by:

Gülcan Öztürk, Balikesir University, TürkiyeLesley Farmer, California State University, Long Beach, United States

Agnese Davidsone, Vidzeme University of Applied Sciences, Latvia

Copyright © 2024 Suing, Alarcon-Llontop and Bizberge. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abel Suing, YXJzdWluZ0B1dHBsLmVkdS5lYw==

Abel Suing

Abel Suing Luis-Rolando Alarcon-Llontop

Luis-Rolando Alarcon-Llontop Ana Bizberge

Ana Bizberge