- 1English Linguistics, TU Dortmund University, Dortmund, Germany

- 2English Department I,University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

In Croatia, speaking many different languages is popular and perceived as a prestigious skill. English is one of the most commonly spoken additional languages and many Croats engage with it frequently, e.g., when watching undubbed American or British TV programs and movies. Due to this frequent engagement as well as the rise of English as a global language, especially younger Croats and those who work in the tourism sector tend to be quite proficient users of English. When interacting with tourists, Croats use accommodation strategies to cater to the tourists’ linguistic needs to increase understanding and communicative success (cf., e.g., Kaur, 2022 on pragmatic strategies). The present investigation centers on the specific pragmatic strategies present in such interactions between international tourists and local tourism workers and, based on a subset of 48 conversations recorded at the Franjo Tuđman Airport Zagreb, it illustrates the pragmatic strategies in the negotiation of directions to the city center. It shows that tourists and tourism workers tend to use the investigated pragmatic strategies in the following order of frequency: SMs>DMs>HMS>repetition>rephrasing>other features. However, taking a closer look, the study unveils how tourism workers balance the needs for efficiency and sociability when engaging with international tourists and offers a first take at understanding why the answers to similar questions often vary as the quality and quantity of the provided answers are influenced not only by linguistic factors.

1 Introduction

Tourism is, and has always been, a highly volatile context for multi-language use. In addition to the local language(s), the tourists’ languages are traditionally part of the linguistic environment of tourism. In recent times, English has conquered a considerable portion of these contexts and has become the dominant language and lingua franca in international tourism. However, as the tourism sector is highly diverse, defining and describing English in tourism is challenging. English is used in numerous countries by speakers of various other (first) languages to interact for a multitude of purposes – private and professional. Hence, English in tourism is not the use of a certain variety of English by a specific speaker group, nor the use of ‘just’ Learner English or English as a Lingua Franca; English in tourism is – or can be – a mix of all these Englishes and its users can be considered a transient multilingual community (cf. Mortensen, 2017; Pitzl, 2018). Croatia is the ideal place to study English in tourism contexts, as it has a unique multilingual ecology to which visitors and their use of various other languages add. A space in which many such international interactions in English occur is airports. Hence, the paper at hand investigates the pragmatic strategies used in tourism interactions at a visitor center in Franjo Tuđman Airport in Zagreb. In extending the research on pragmatic strategies that have so far been studied and commonly found in ELF (English as a Lingua Franca) conversations to tourism contexts, further insights into the nature and hybridity of English in tourism are developed. Exploring pragmatic strategies and structures will unveil which pragmatic strategies are characteristic of brief interactions in tourism and if and how their use converges or diverges from ELF use in ‘traditional’, i.e., educational, settings. Tourism is a unique context of ELF use, due to varying levels of speakers’ fluency and agency as well as the interlocutors’ different intentions and goals in the investigated conversations. Tourism contexts are found to be a melting pot of private, professional, practiced, spontaneous, fluent, and basic language use that offer valuable insights into the nature of communication as well as English in transient multilingual communities.

2 Multilingual Croatia

The Republic of Croatia is a small country in southeastern Europe bordering the Adriatic Sea. Prior to its independence in 1991 and together with Serbia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Macedonia, Croatia constituted the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. All languages of these member republics of Yugoslavia, i.e., Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian, and Slovenian, had equal rights and institutional support. In addition, multilingualism was encouraged and a multilingual approach to education was widely implemented, allowing students to learn and be taught in both their mother tongue and/or Serbo-Croatian (Bugarski, 2012; Požgaj Hadži, 2014). Still, Serbo-Croatian was the primary language of approximately 73% of the inhabitants of Yugoslavia and was promoted as the common language of the various ethnic groups of Yugoslavia (Bugarski, 2004, 2012).

Serbo-Croatian was conceptualized as a pluricentric language with two main standard varieties, namely Serbian and Croatian, on the federal level and another standard variety for each of the two constituent republics Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the aftermath of the demise of Yugoslavia, declaring a unique and independent national language was an important step toward building a feeling of nationality for these now-independent countries. Besides the use of only the Latin alphabet (Croatian and Bosnian) or both the Latin and the Cyrillic alphabet (Serbian and Montenegrin), the differences between the declared languages are minimal. However, they functioned as a sign of each country’s close identification with their respective ethnic majority group(s). Hence, in the early 1990s, Croatia declared their national variety to be Croatian, while the successor state of Yugoslavia, which comprised Serbia and Montenegro, declared Serbian their official language, and the de facto official languages of Bosnia and Herzegovina are Bosnian, Serbian, and Croatian (Gröschel, 2009).

While Croatian has been the sole official language of Croatia since independence (cf. Bunčić, 2008), most of its inhabitants speak multiple languages (e.g. Mihaljević Djigunović, 2013) and the country’s language policies have developed accordingly. In addition to Croatian, which is a/the first language of the vast majority of inhabitants (95.25% per 2021 census, cf. Croatian Bureau of Statistics, 2023), several minority languages are spoken in Croatia contributing to the country’s linguistic and cultural diversity. After an initial interest in linguistic purism and Croatisation immediately after the independence of Croatia, these languages have been recognized in and protected by the Croatian Constitution since 2002 (cf. Petričušić, 2004). Furthermore, due to the mutual intelligibility of the Serbo-Croatian languages, namely Croatian, Serbian, Bosnian, and, later, Montenegrin, members of other ethnic groups of former Yugoslavia (continued to) inhabit Croatia. As of 2021, the most commonly spoken first languages in Croatia are Croatian (95.25%), Serbian (1.16%), and Bosnian (0.45%). Other minority languages, such as Romani, Albanian, Italian, Hungarian, Czech, German, and Russian (in order of speaker numbers), are each spoken as a first language by less than 1 % of the population (Croatian Bureau of Statistics, 2023).1 In regions inhabited by a significant number of members of other ethnic groups, these groups’ languages receive the status of an official language in local administration and have the right to education in their languages (preschool to high school, see European Commission, 2022). Whether a language is considered an official language in local administration is based on (current) speaker numbers in the respective region and may be changed in case these numbers vary considerably. In addition to these official measures, ethnic minorities in Croatia preserve and execute their languages and (cultural) identities through media, e.g., newspapers and radio and TV programs, and cultural institutions. Besides the official language Croatian and the introduced minority languages, English holds a special position within Croatia’s linguistic ecology.

English is a central language in Croatia. Although there is a small minority of inhabitants for whom English is their first language (cf. Croatian Bureau of Statistics, 2023), it is more widely used as a foreign or additional language (cf. Strang, 1970). International movies and TV programs are often in English, resulting in many Croats being in contact with English on a regular, if not daily, basis. Further stressing its global relevance, English is the only foreign language that is obligatory to study for all students. Foreign language learning starts in the first grade and English is by far the most widely learned and taught foreign language in Croatian first-grade classrooms (85–90%, cf. Medved Krajnović and Letica, 2009). While learning additional foreign languages is optional if English was chosen in the first grade, students who chose another foreign language, such as German, Italian, French, or Spanish, must start learning English in grade four. Secondary education in international schools and a small but increasing number of tertiary education programs use English as the medium of instruction (cf., e.g., Drljača Margić and Vodopija-Krstanović, 2018, 2020 for an overview). Similarly to other countries, English is the language of communication in international contexts, such as business or tourism, in Croatia. With its more than 5,800 kilometers of coastline to the Adriatic Sea, many beautiful islands and picturesque old towns, as well as stunning mountainous regions, Croatia is very popular with foreign and domestic tourists. In 2021, 12.8 million tourists visited Croatia, 10.6 million of whom were foreign. Tourism has become one of the major sources of income for the economy of Croatia. Although most visitors are German-speaking, i.e., 2.7 million from Germany and 1 million from Austria in 2021, closely followed by visitors from Slovenia (just under 1 million in 2021; Croatian Bureau of Statistics, 2022), English serves as the main lingua franca in the tourism industry. The role of English in international tourism in general is discussed in the following section.

3 English in tourism contexts

Tourism – or rather mobility in general – used to be linked to using a foreign language. This required either visitors to have a certain command of local languages for basic communication or locals to learn the language(s) of frequently visiting speaker groups. The rise of English as a global language has brought change to these dynamics; English is the global language of our times and often serves as the default language in international contexts, such as tourism. As a result of increasing levels of proficiency of many speakers around the globe, based on more extensive engagement in learning and teaching English, communicational success when using English is often greater than it was prior to the rise of English. Describing characteristics of English in these contexts is a challenge, as the use of English in tourism is not limited to locals, such as Croats in Croatia, but also includes visitors from various other countries. These might be speakers from all Kachruvian circles (Kachru, 1985) who speak different and often multiple first languages and all use English as a first, second, or additional/foreign language for communication. Adding to its complexity, tourists come and go causing a major portion of this user group to constantly change in any given local setting. Hence, they can also be considered Transient Multilingual Communities (cf. Mortensen, 2017; Pitzl, 2018 for an introduction and definition). Transient Multilingual Communities are quite similar to Communities of Practice (Eckert, 2006) as they are defined as “social configurations where people from diverse sociocultural and linguistic backgrounds come together (physically or otherwise) for a limited period of time around a shared activity” (Mortensen and Hazel, 2017: 256). However, they are characterized by an anthropological focus that enables the inclusion of communities that lack linguistic norms, are less stable and often short-lived (Pitzl, 2019).

Somewhat independent of the transitory nature of the tourism industry and its stakeholders, scholars have resorted primarily to two frameworks when investigating and describing English in tourism. Some have theorized it as English for Specific Purposes (ESP, e.g., Maci, 2018; Wilson, 2019), especially when pursuing a focus on how to learn and teach English for tourism contexts (e.g., Kostic Bobanovic and Grzinic, 2011; Ennis and Petrie, 2019; Stainton, 2019). Others use the English as a lingua franca framework (cf. e.g., Jenkins, 2000, 2007; Seidlhofer, 2004, 2011 on the framework, Jaroensak and Saraceni, 2019, on its use in tourism), due to the national, social, and linguistic variety of the speakers involved. ELF emerged around the turn of the century and might be defined as “any use of English among speakers of different first languages for whom English is the communicative medium of choice […]” (Seidlhofer, 2011: 7). The conceptualization of ELF is rooted in the assumption that English belongs to its users rather than to those that were born in specific environments and, therefore, happen to be native speakers of English. Scholars have initially focused on identifying and describing morphosyntactic and phonological characteristics of ELF that facilitate non-native speakers’ communication and on finding norms of use that could improve the teaching of English to those speakers (Jenkins, 2000: 11; Jenkins, 2007: xii, see Jenkins, 2000 on phonological features and the Lingua Franca Core; Seidlhofer, 2004; Dewey, 2007; Cogo and Dewey, 2012; Mortensen, 2013, on grammatical features; Seidlhofer, 2004; Jenkins, 2007, on teaching ELF, among others). Subsequently, research in ELF has shifted its interest toward specific settings of use, such as ELF in Academic Settings (see, e.g., ELFA, 2008; Mauranen, 2012; Hynninen, 2016) or Business ELF (BELF) (see, e.g., Gerritsen and Nickerson, 2009; Murata, 2015) and sociolinguistic aspects of ELF, such as pragmatic strategies. These pragmatic strategies of ELF will be introduced in more detail in the following section.

4 Pragmatics of ELF

The pragmatics of ELF and the interrelation of ELF and the speakers’ identities have received increasing attention in recent years as scholars have focused more on the sociolinguistics of ELF (e.g., House, 2003, 2010, 2011, 2012; Meierkord, 2004; Canagarajah, 2007; Hülmbauer, 2009; Sung, 2015, among others). Since ELF is not defined and understood as a variety of English, its users cannot select from a fixed set of rules and norms for its use but must negotiate strategies to ensure successful communication in culturally and linguistically diverse settings. Scholarly attention has been focused on understanding how interactants in ELF conversations ensure and construct understanding, resolve potential misunderstandings, and accommodate each other in doing so. In the early years, ELF research focused on misunderstandings, which were expected to be caused by the just-mentioned missing set of rules and norms. Scholars have investigated strategies of negotiating meaning, i.e., how these misunderstandings are resolved and prevented (e.g., Schegloff, 2000; House, 2003; De Bartolo, 2014). Early in these studies, researchers have found surprisingly few misunderstandings in ELF conversations (see, e.g., Meierkord, 1996). Furthermore, if misunderstandings occurred, they often were ‘let pass’ and remained unresolved. This ‘let-it-pass’ principle has been found to be commonly adopted, especially if the social aspect of communication is perceived as more central than the content that is shared. In domain-specific interactions, in which the content of the interaction is more crucial, the principle has been found to be adhered to less frequently (Cogo and House, 2018). Recent work on the pragmatics of ELF shows more diverse interests and can be broadly divided into focusing, for example, on the construction and negotiation of meaning, the use of multilingual resources, and the use of discourse elements. As the paper at hand will focus on the use of discourse elements, specifically discourse markers and backchanneling, as well as the co-construction of meaning and the role of interruptions in these constructions, the theoretical introduction will be limited to these concepts.2

To enable successful communication between speakers of different first languages and potentially different proficiency levels in English, co-constructing meaning is a powerful resource as this joint activity reflects and deepens the interlocutors’ feelings of group belonging and consensus. This co-construction might be actively invited, for example by asking for clarification, a lexical gap to be filled, or a repair or rephrasing to be provided, or it might occur uninvitedly, which might cause interruptions and overlapping utterances. Rather than considering, for example, such interruptions as impolite, both types of co-constructions are typically perceived as positive interactions and as expressions of support. Studies have furthermore shown that strategies of co-construction are not only implemented in cases of trouble but also to show and prevent anticipated difficulties or misunderstandings (cf., e.g., Pitzl, 2005; Mauranen, 2006, 2012; Watterson, 2008; Kaur, 2009, 2010, 2011; Cogo, 2010; Björkman, 2011, 2014; O’Neal, 2015; Pietikäinen, 2018).

Concerning discourse elements, ELF users have been found to use discourse markers, such as you know, I think, and so, to manage their interactions (e.g., House, 2009). Cogo and House (2018) point out that, while these discourse markers are also used prototypically, especially you know is often found in instances in which the speaker is momentarily incoherent or needs time to repair previous utterances or plan the upcoming ones. Its use rarely signals an invitation for the interlocutor to engage in the construction of the utterance in question – as the second person pronoun you might suggest – but can rather be understood as a solidarity marker to create an in-group feeling between the conversational partners. Similar tendencies hold for the use of so (cf. Cogo and House, 2018). Other discourse markers, such as I think and I mean have been found to be used mostly in their prototypical meaning, with the former often expressing the speaker’s opinion and the latter often introducing the speaker’s evaluation (Baumgarten and House, 2010a). Backchanneling is a further frequently used strategy in ELF conversations (cf., e.g., Cogo, 2009; Baumgarten and House, 2010b; Kalocsai, 2011; Wolfartsberger, 2011; House, 2013, 2014). These minimal items of agreement, such as yeah, hm, ok, mmh, etc., are also solidarity markers which serve an encouraging function and can be a signal of active listening. Yes and yeah, in addition, can be used as an indication of turn-taking or processing when used at the beginning of an utterance or as an invitation for confirmation when used in utterance-final position (Baumgarten and House, 2010b).

The strategies presented so far are mostly based on studies conducted in academic or private contexts, with only one (Pitzl, 2005) focusing on business meetings. Tourism, however, is neither a purely private context nor only business; it represents a unique mix of both contexts. The few studies that have focused on the use of ESP in tourism contexts, such as Jaroensak (2018) and Wilson (2018), have found co-construction of utterances, repetition, and reformulation to be the most prominently used strategies. However, as interactions in tourism contexts often include one party engaging in a professional or business interaction and the other in a leisure and private one, each interlocutor’s purpose for communication potentially differs and, hence, the strategies used might differ as well. In addition, especially in interactions such as tourists asking for advice in visitor centers, i.e., the setting central to the paper at hand, the initiation of the conversation as well as the first utterance or question might be prepared by the tourist and consequently rather be considered a monolog. Monologs, following Kaur (2022), include less use of pragmatic strategies than dialogs.

5 Data and method

The data and findings presented in this section are part of a more extensive investigation of multilingualism in tourism interactions in Croatia. The overall project encompasses three regions in Croatia: the North West, specifically the island Krk and the town Rovinj; Dalmatia, specifically Croatia’s second largest city Split; and the capital Zagreb. In the course of this large-scale project, the author collected four different types of data, i.e., 104 ethnographic questionnaires, 71 recordings of qualitative sociolinguistic interviews, 79 recordings of conversations between tourism workers and tourists, as well as extensive linguistic landscaping data. The following insights into the pragmatic strategies employed in tourism interactions are based on the above-mentioned conversations, which were audio-recorded in Zagreb in 2023. They all are conversations between tourists and employees of the Zagreb Tourist Board,3 working in one of the three Visitor Centers in the city. 72 conversations were recorded at the Visitor Center at Franjo Tuđman Airport, Zagreb. Seven of these conversations were not conducted in English and another 17 consisted of only a basic exchange, i.e., one question that was answered. Hence these 24 conversations were excluded from the data set for this paper. The remaining 48 conversations build the subset used for this study. As the focus of the study at hand is on interactions that include asking for ways into the city center, the remaining conversations are categorized as being concerned with traveling into the city center (N = 34) and not being concerned with this topic (N = 14).

Concerning the participants of the study, four tourism workers and 84 tourists agreed to participate in the study and to be recorded. The tourism workers were informed about the study and asked for their consent at the beginning of each day of the recordings. Tourists were approached after entering the Visitor Center and informed about the study and the included recording before being asked for their consent. After the consent was given, there has not been any further engagement between the tourists and the researcher during or before the conversations and all speakers remained anonymous. The recordings were transcribed orthographically in ELAN4 based on MacWhinney’s (2000) CHAT (Codes for the Human Analysis of Transcripts), as this is a commonly used and accepted format. The guidelines were adapted to meet the needs and focus of this investigation.5 The lengths of the conversations vary between 13 and 281 s. Due to their responsibility to answer the tourists’ (brief) questions, the tourism workers are responsible for the majority of utterances in all conversations. In preparation for the analysis, the conversations were grouped by topics discussed, such as asking for directions to the city center, receiving a brochure, or inquiring about rental car services, and annotated for their structure and the pragmatic strategies at use. The structures annotated for are discourse markers, solidarity markers, repetitions, rephrasing without misunderstanding, repairs, hesitations markers, multilingual elements, interruptions, wrap-ups, and co-construction of meaning.

6 Findings

6.1 Pragmatic strategies in conversations concerning directions to the city center

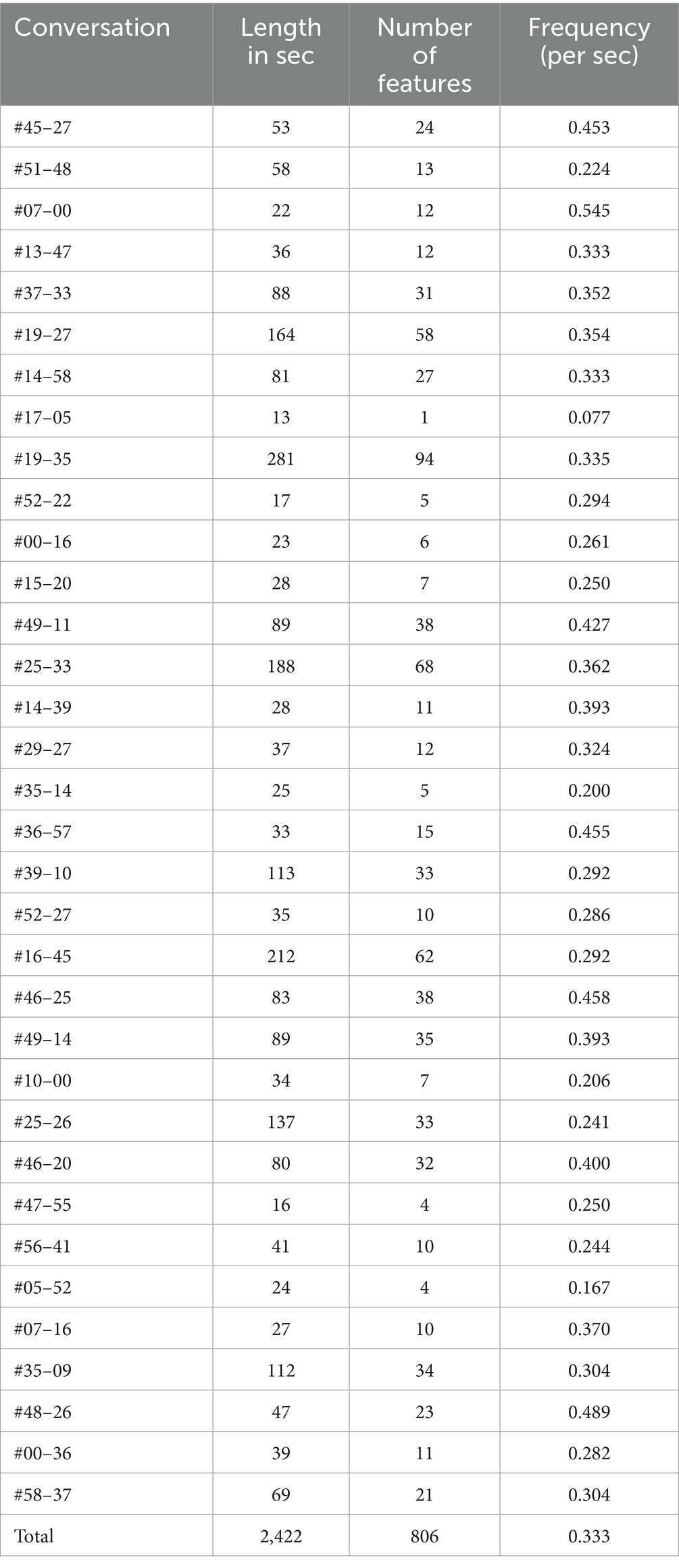

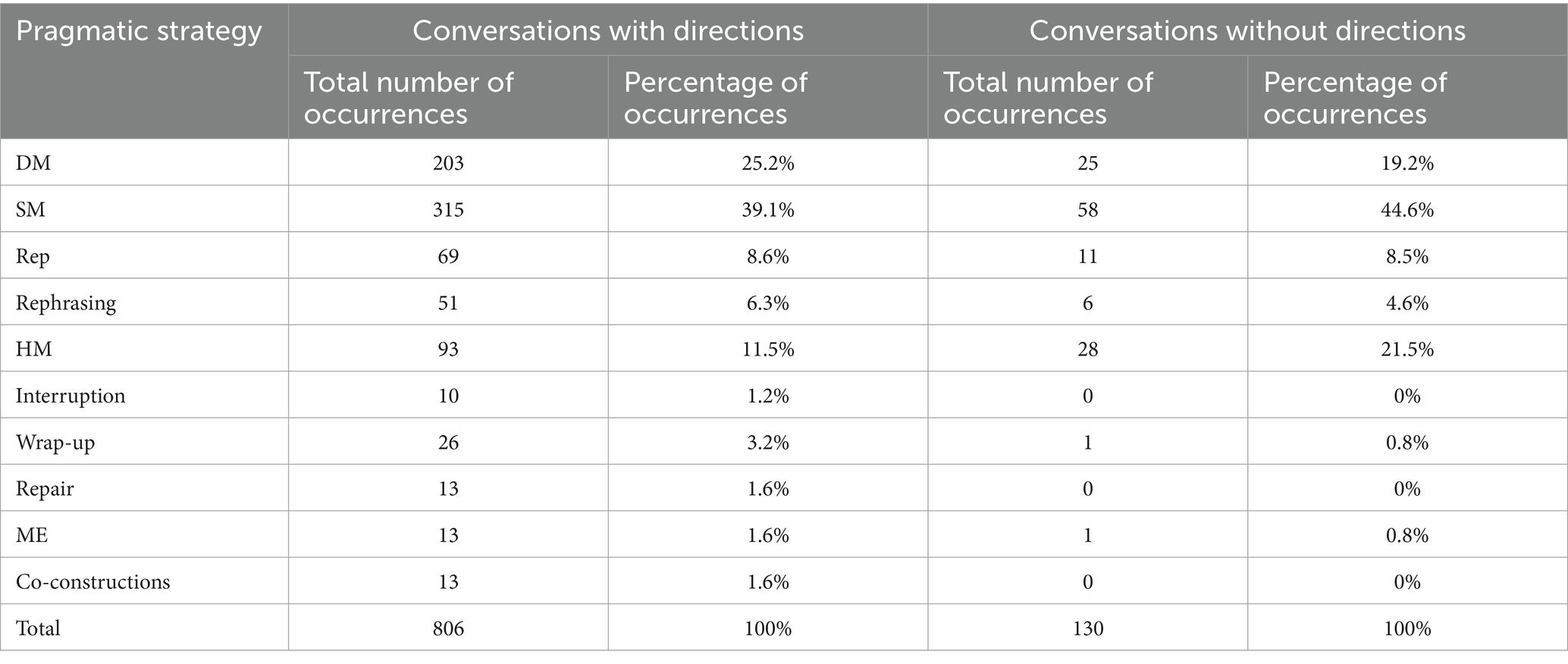

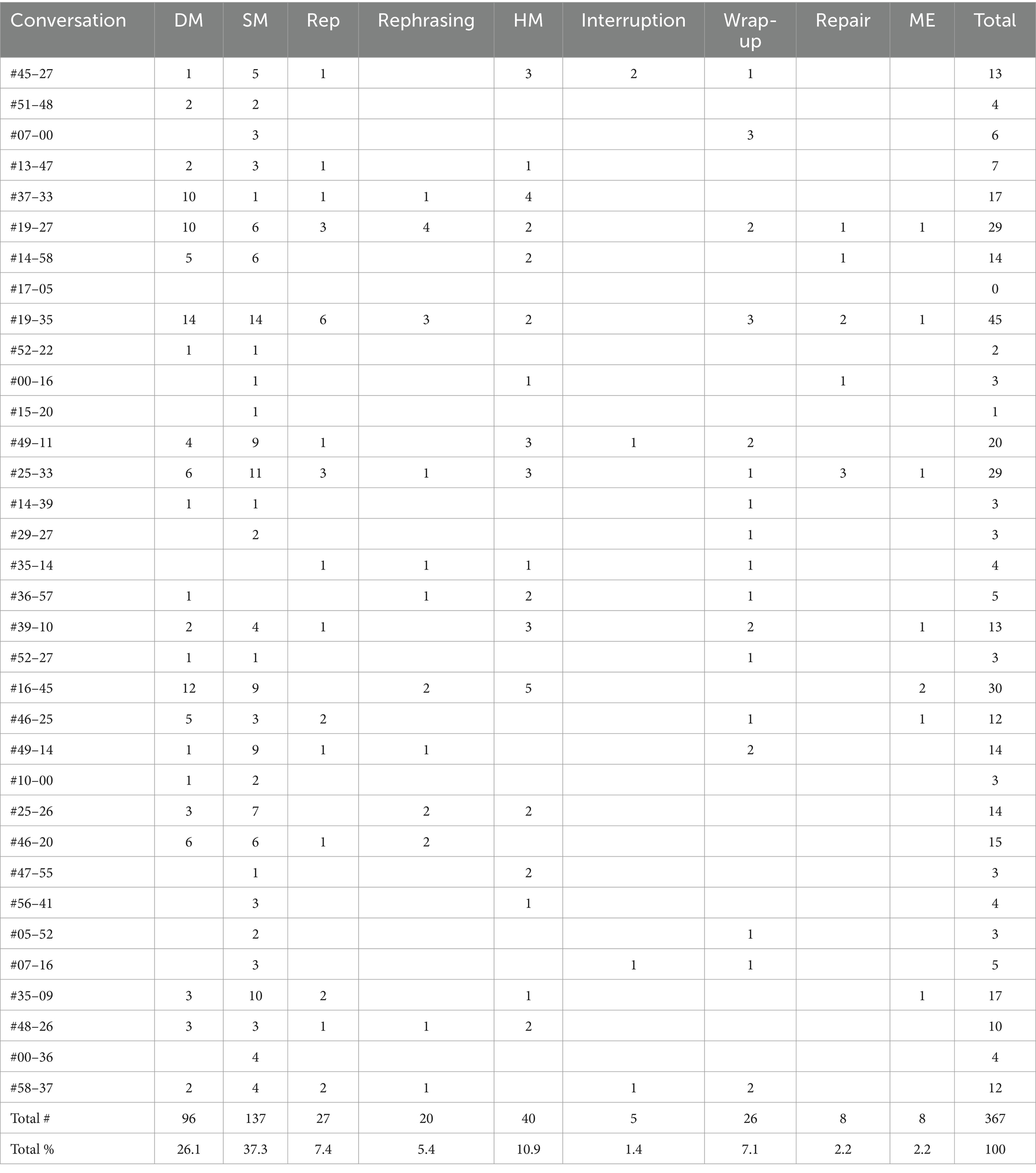

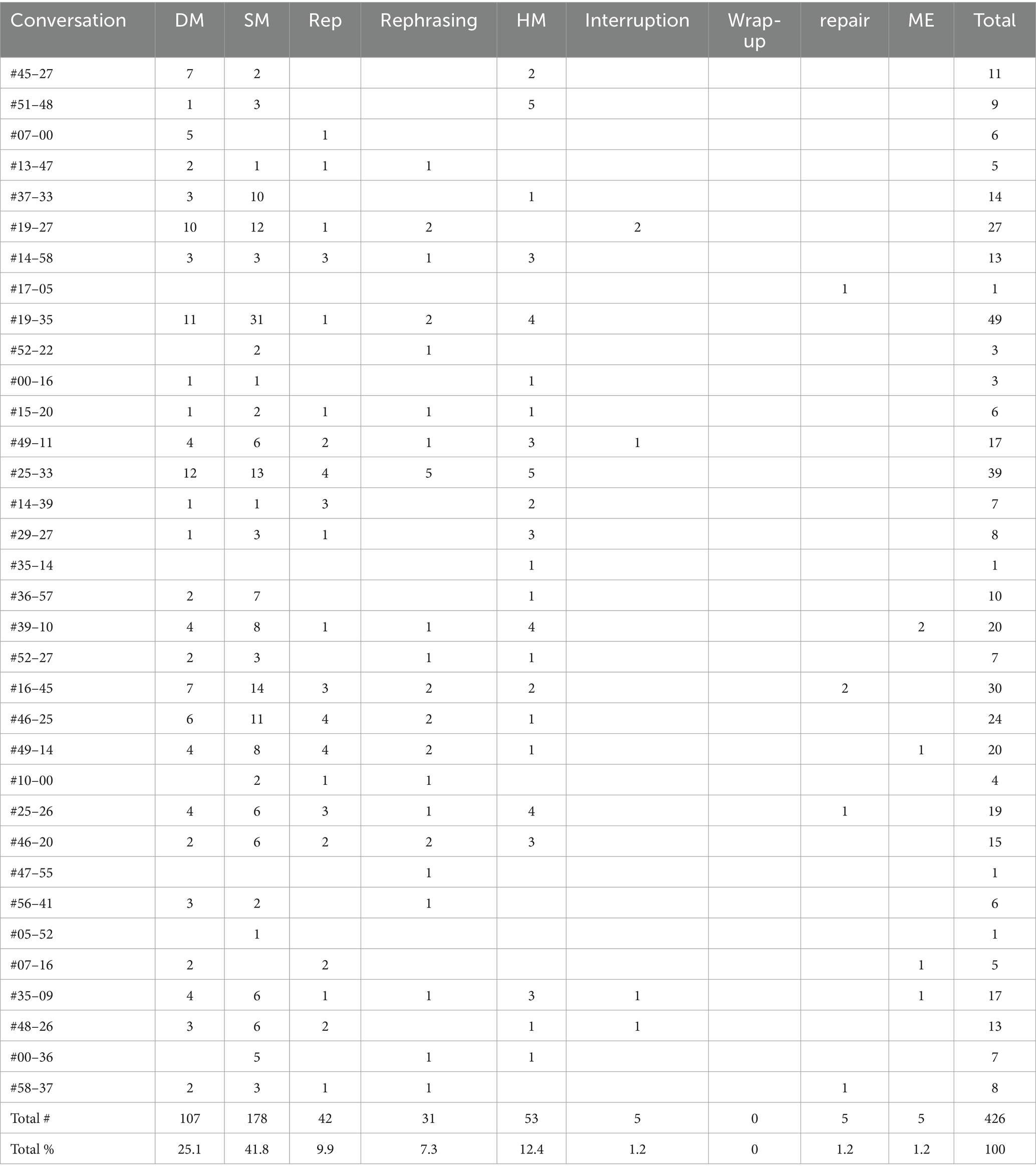

The recordings in this study were examined for the occurrence of nine different pragmatic features and the frequencies of their use. Starting with the data subset which is concerned with tourists asking for directions to the city center, the 34 relevant conversations include a total of 806 pragmatic features which is an average of 23.7 features per conversation. The conversations are between 13 and 281 s long and the frequency of use of pragmatic strategies ranges between 0.489 and 0.077 features/s with an average of 0.322 features/s (cf. Table 1). As shown in Table 2, the features found can be categorized as 203 discourse markers (henceforth DM, cf. Example 1), most often so, you know, and well; 315 solidarity markers (henceforth SM, cf. Example 1), most often yes, yes yes, yeah, and okay; 69 repetitions (henceforth Rep, cf. Example 1); 51 rephrasings that do not involve the communication partner (cf. Example 2); 93 hesitation markers (henceforth HM, cf. Example 1), such as eh, hm, and ehm; 13 repairs, i.e., rephrasings that are caused by a miscommunication that has been made explicit by one of the interlocutors (cf. Example 3); and 13 multilingual elements, which, in this dataset, consist exclusively of Croatian location names (cf. Example 4). The conversations further include 10 interruptions (cf. Example 5), 26 wrap-ups, i.e., instances in which the employee answered a set of routinely subsequent questions before the first one was (fully) uttered (cf. Example 6), and 13 co-constructions which involve both conversational partners (cf. Example 7). As these final three strategies cannot always be separated clearly, they were identified and categorized according to the purpose of the used feature that was considered dominant. Local tourism workers use 367 (Table 3) and tourists use 426 (Table 4) of the 793 features.6

Assessing tourists and local tourism workers separately, Table 3 shows that tourism workers most often use SMs (N = 137; 37.3%) followed by DMs (N = 96; 26.1%). Other pragmatic strategies are used considerably less often with 27 (7.4%) repetitions, 20 (5.4%) rephrasings, 40 (10.9%) HMs, five (1.4%) interruptions, 26 (7.1%) wrap-ups, eight repairs, and eight multilingual elements (2.2% each). Although the exact numbers vary a little, Table 4 shows that tourists appear to have similar preferences as they also use SMs most often (N = 178; 41.8%). Furthermore, they use 107 (25.1%) DMs, 42 (9.9%) repetitions, 31 (7.3%) rephrasings, 53 (12.4%) HMs, five (1.2%) interruptions, no wrap-ups, five repairs, and five multilingual elements (1.2% each).

Some pragmatic strategies are used considerably more often by tourists than by tourism workers, i.e., SMs, Reps, HMs, and rephrasings (cf. Example 2 for rephrasings and Example 1 for the rest). Others are used more often by tourism workers, i.e., wrap-ups, repairs, and multilingual elements (cf. Examples 1, 3, 4, respectively).

EXAMPLE 1

Tourist: “Er, what’s the best way getting in there? We’re here for two days. Is there any sort of travel pass we can have for two days?”

Tourism worker: “Er, yes. There is a shuttle bus that goes from here to the bus station in the city.”

Tourist 1: “Yeah.”

Tourism worker: “Or you can take a public transport.”

Tourist 1: “Right.”

Tourism worker: “I will show you.”

Tourist 1: “Yeah, which would be [/] which would be +/?”

Tourism worker: “So, if you take a shuttle, it will leave you here on the main bus station. Then|.”

Tourist 1: “Okay.”

Tourism worker: “| with tram number six, you can come to here to the main square.

(Conversation 19–35, 00:23:00–00:50:98)

Example 1 shows the use of several pragmatic strategies by both interlocutors. The tourist starts their turn with an HM (“Er”) before stating the question of how to best get into the city. The tourism worker starts the response utterance also with an HM (“Er”) before confirming the preceding question. The elaborations are followed by the tourist’s use of SMs (“Yeah.” and “Right.”) but are not interrupted by them. The invitation to show the directions on a map is accepted by the tourist, who aims at specifying the need, presumably, to see the best way. This request is interrupted by the tourism worker’s elaborations that are initiated by the use of a DM (“So”). These explanations are interrupted by the tourist (“Okay”). However, this interruption does not serve a turn-taking purpose but is a confirmation of understanding and serves as a SM.

Example 2 shows the tourist rephrasing their utterance before a misunderstanding can occur while Example 3 shows the tourism worker repairing their utterance after the second tourist explicitly asked for a confirmation of previously given information and a mistake becomes apparent. The only multilingual elements, i.e., elements taken from a language other than English, that can be found in this dataset are location names (cf. Example 4).

EXAMPLE 2

Tourist 1: “We are staying [//] we got an, erm, booking_dot_com apartment. It’s near the funicular railway.” (Conversation #19–35, 00:07:12–00:15:68).

EXAMPLE 3

Tourist 2: “And it’s [four?] Kuna [/] Kuna?”

Tourism worker: “No, no, no. Euro! Sorry! Euros.” (Conversation #19–35, 02:28:20–02:32:45).

EXAMPLE 4

Tourism worker: “If you wanna go to Maksimir or Jarun with tram, you can buy the ticket forty minutes.” (Conversation #19–35, 01:47:97–01:52:99).

EXAMPLE 5

Tourism worker: “You can buy it there. Three or four [/] three o& [//] three days +/?”

Tourist: “How do [/] how do I get there?”

Tourism worker: “Where are you staying in the city center?” (Conversation #19–27, 00:54:36–01:01:40).

EXAMPLE 6

Tourist: “So I wanted to ask where can I take the airport bus and can I pay with the card?”

Tourism worker: “No cash only. 6 euro per person. Outside on the right. Only you can try to buy it online.” (Conversation #56–41, 00:08:32–00:14:64).

EXAMPLE 7

Tourist: “This says get a tram.”

Tourism worker: “Number +/.”

Tourist: “Seventeen.”

Tourism worker: “No, number eleven or twelve.” (Conversation #19–27, 02:00:06–02:05:40).

Half of the conversations that are concerned with directions to the city center include wrap-ups (cf. Table 3). Examples 6, 8, 9 show such wrap-ups. When wrap-ups are used, the tourism worker deduces the question the tourist is about to ask (Where is the bus stop?, Where can tickets be bought?, How much is a ticket?, etc.) based on the preceding line of questioning, a few initial words, possibly a gesture or shift of gaze, and their experience on the job. This deduction of future (sets of) questions requires these lines of questioning to be of high frequency. Due to this high frequency, it has been assumed that tourism workers would have developed a routine in answering them, i.e., would answer them in a similar way – or even with always the same internalized and routinized chunk of utterances – every time they occur. The dataset at hand, however, shows that this is not the case. For high-frequency questions, such as those concerned with asking for directions to the city center, the content and scope of the provided information in the tourism workers’ answers vary considerably. In the 34 conversations this section is concerned with, the participating tourism workers mention the following topics exclusively or in different constellation with another topic mentioned in this list: Public bus service/Bus #290; shuttle bus, location of bus stops, costs of ticket, transportation schedule, point-of-sale for tickets, possible/preferred destination. The shuttle bus has been mentioned most often, specifically in more than two-thirds of the conversations (N = 23) and the costs of the ticket the least often (N = 6). While all explicit inquiries about how to get to the main station result in the recommendation of the shuttle bus and questions about either the shuttle bus or the local bus specifically also result (first) in elaborations on the respective service only, how the more general question of how to get into the city center is answered cannot be predicted based on the dataset. While in some instances the tourist is presented with both options (Example 8), in others only one is presented. However, if the tourists ask specifically for the bus station, the shuttle bus is most often recommended (Example 9).

EXAMPLE 8

Tourism worker: “Hello, can I help you?”

Tourist: “Yes, we are planning to go with the bus to the city center.”

Tourism worker: “With the shuttle bus or public transport?”

Tourist: “Public transport.”

Tourism worker: “It stays over there across the road on the left side.”

Tourist: “Okay, and to pay, do we need +/?”

Tourism worker: “Yeah, you can buy the ticket here at the newspaper kiosk, here in the hall on the right.”

Tourist: “Okay, that’s fine. That’s all we need to know. Thank you.”

Tourism worker: “You’re welcome. Bye.” (Conversation #29–27, 00:06:12–00:31:02).

EXAMPLE 9

Tourism worker: “Hello.”

Tourist: “Hello, right. I understand there’s a bus into the bus station.”

Tourism worker: “Yeah, shuttle bus over there, outside on the right.”

Tourist: “And the tickets, can I get on [=!lengthening of vowel, rising intonation].”

Tourism worker: “In the bus from the driver. Cash only.”

Tourist: “Cash only, is it?”

Tourism worker: “Yeah. Six Euro.”

Tourist: “And there’s ATM standing by here, is it?”

Tourism worker: “Yeah, on the right side.”

Tourist: “Super, that’s all [/] That’s all, thank you.”

Tourism worker: “Okay. Bye.” (Conversation #07–00, 00:01:35–00:19:76).

Having assessed the pragmatic strategies used in conversations concerned with receiving directions to the city center, we now briefly turn to conversations held in the same setting that are concerned with other topics.

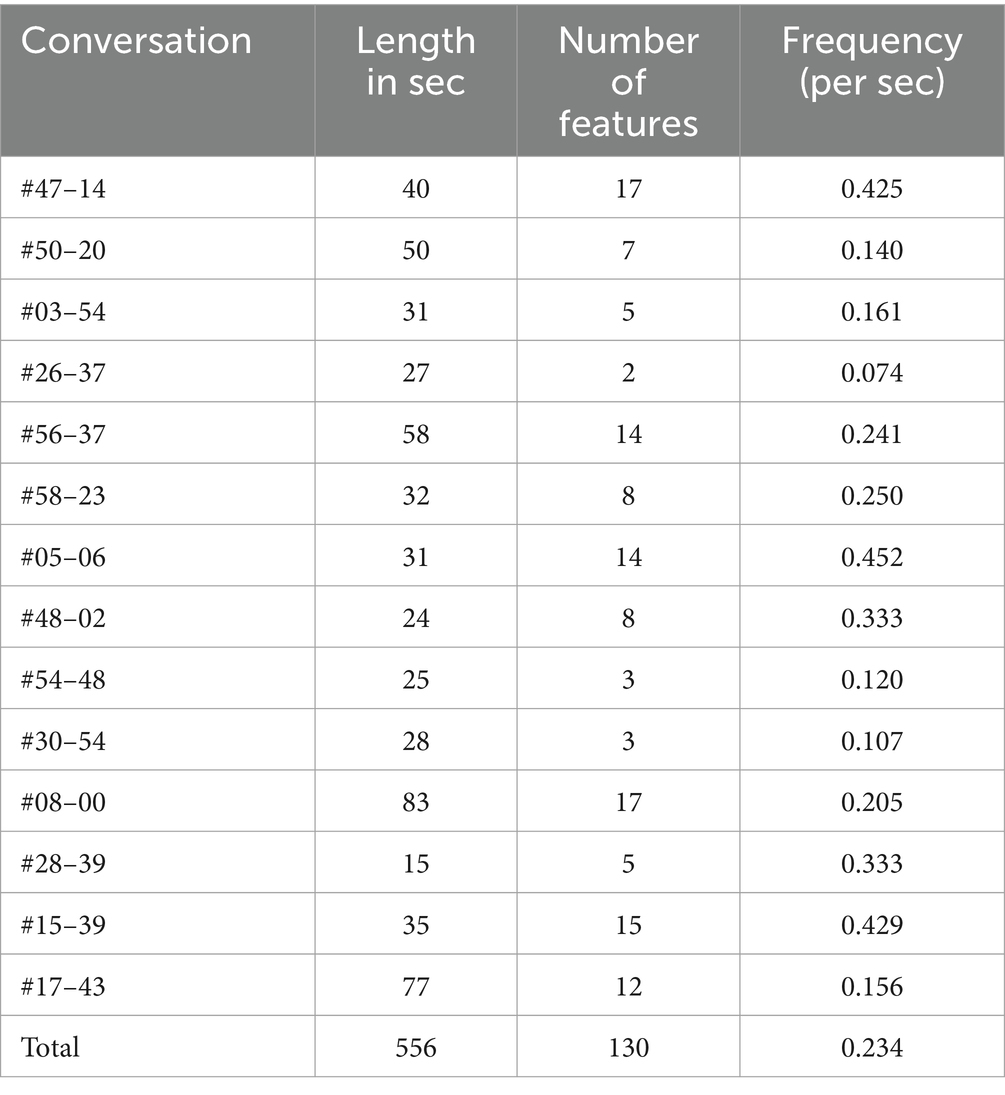

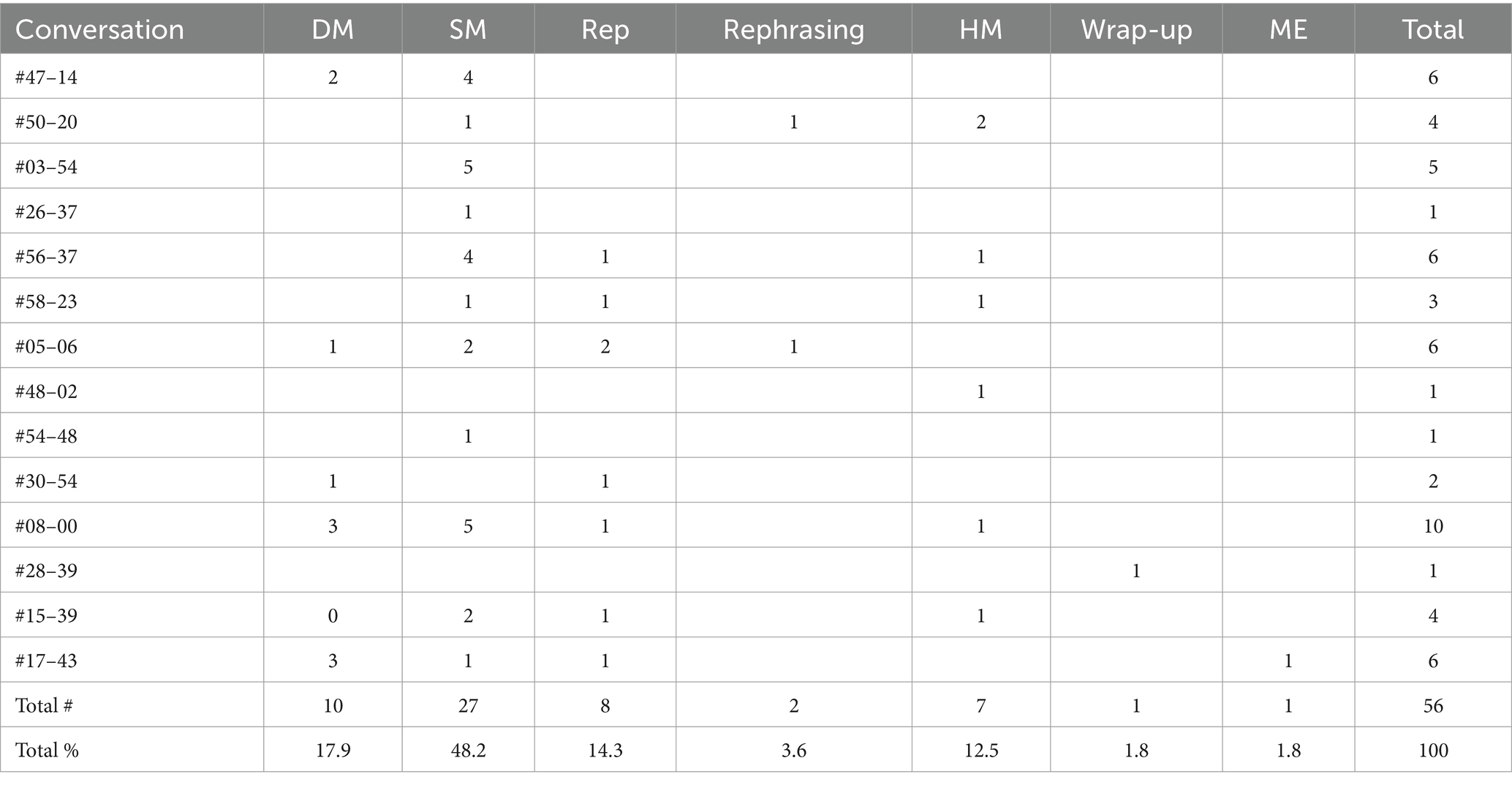

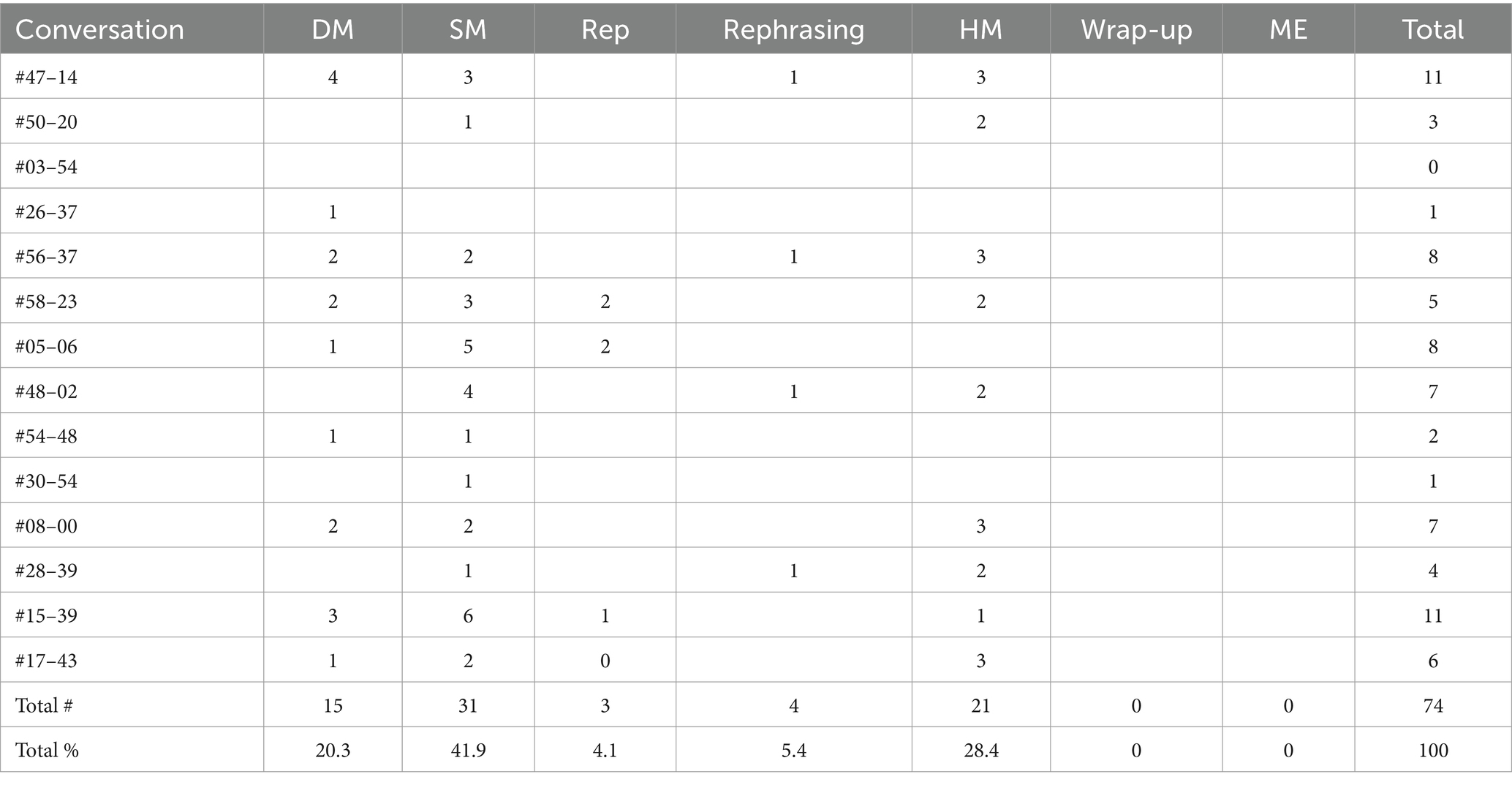

6.2 Pragmatic strategies in conversations concerning other topics

Moving to the 14 conversations that are concerned with other topics than directions to the city center, 130 pragmatic features have been found which represents an average of 8.7 features per conversation. The conversations’ lengths range between 15 and 83 s and the frequency of use of pragmatic strategies ranges between 0.074 and 0.452 features/s with an average of 0.245 features/s (cf. Table 5). These features can be further specified as 25 DMs; 58 SMs, 11 Reps; six rephrasings that do not involve the communication partner; 28 HMs; no repairs; and one multilingual element. In addition, they include neither interruptions nor co-constructions of meaning and only one warp-up, i.e., instances in which the employee answered one or more questions before the first one was fully uttered (cf. Table 2). Similar to the dataset in Section 6.1, tourists make more extensive use of pragmatic strategies than tourism workers. While local tourism workers use 56 (Table 6), tourists use 74 (Table 7) of these 130 pragmatic strategies and features. Table 6 shows that tourism workers use SMs most often (N = 27; 48.2%), followed by DMs (N = 10; 17.9%). They use eight (14.3%) Reps, seven (12.5%) HMs, two (3.6%) rephrasings, one wrap-up, and one multilingual element 1.8% each. This represents the same order of frequency in the use of pragmatic strategies as in the dataset described in Section 6.1. Tourists, however, appear to behave differently as they also use SMs mostly (N = 31; 41.9%) but use more HM (N = 21; 28.4%) than DMs (N = 15; 20.3%). Furthermore, they use three (4.1%) Reps, four (5.4%) rephrasings, and neither wrap-ups nor multilingual elements (cf. Table 7). The topics of these conversations include asking for a map or brochure, asking if one could get a receipt from a taxi driver, as well as inquiries about rental car services, sim card purchases, and sightseeing recommendations.

7 Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, the pragmatic strategies used in English conversations between tourists and tourism workers at Zagreb Airport in Croatia have been assessed. Despite the great differences in context and content, pragmatic strategies found in studies on ELF in educational and business contexts, among others the discourse markers so and you know (e.g., House, 2009), the solidarity markers yes and okay (e.g., Baumgarten and House, 2010b), and hesitation markers, have also been found in the dataset at hand. While this similarity allows the positioning of the presented tourism interactions within the ELF framework, their structure and speaker dynamics differ from most other ELF contexts. When assessing the data and findings of the study at hand, two features must be considered: (1) all conversations were initiated by arriving tourists, who would like to be helped with one or more very specific questions; (2) the conversations are comparably short and structurally very similar. The first feature reflects the presuppositions of most tourism interactions being professional interactions for one conversational party and private ones for the other(s). Furthermore, it is linked to the unique power dynamics of such conversations in which the tourists seek assistance – and hence might be considered the less powerful party – while the tourism worker is obliged to help and content the tourists. Consequently, both parties are interested in a successful and amicable conversation. The aspects of the second feature both largely stem from the specific context of the conversations, i.e., a Visitor Center at the airport. Tourists in the arrival hall of an airport have just arrived and are concerned with practical matters such as reaching their accommodation, rather than being interested in general recommendations or highlights for Zagreb. Moreover, tourists who feel less confident using English spontaneously might prepare or translate the most pressing questions beforehand and do not initiate or engage in longer conversations. The resulting brevity and the similar concerns of tourists result in similarly structured conversations and a somewhat limited range of pragmatic features used.

While tourists in conversations about other topics use solidarity markers the most, followed by hesitation markers and discourse markers, both parties in conversations concerned with directions to the city center as well as tourism workers in conversations concerning other topics use the investigated pragmatics elements in the following order of frequency: SMs>DMs>HMS>repetition>rephrasing>other features. While the prominent second position of discourse markers might be due to their general high frequency in conversations as well as their function to create time to process for the user (cf. Cogo and House, 2018), more interestingly, backchanneling as solidarity markers are used most frequently by all user groups in all conversations. While some of this higher number can be explained by the nature of the situation these conversations were held in, i.e., the tourists would approach a staff member of the local Tourist Board to ask for advice or obtain information, and the relatively higher portion of time the tourists (signal) listening, the conversations at hand hint toward a more complex function of these SMs: they signal solidarity, active listening, and receipt of the provided information all at once (cf. Example 1). Tourists use more SMs than tourism workers, needing to signal understanding of the explanation more often than tourism workers do.

The order of frequency of pragmatic strategies is the same for most group-conversation permutations, the frequencies differ across groups. In all conversations, tourism workers use interruptions, wrap-ups, repairs, and multilingual elements more frequently or even exclusively. Tourists, however, use more SMs, Reps, rephrasings, and HMs than tourism workers in conversations concerned with directions to the city center. In conversations that are not concerned with directions to the city center, tourists use more DMs, rephrasings, and HMs than local tourism workers. While the small dataset used in this study does not allow for a generalization of these tendencies, the analysis might still hint toward (1) a topic-independent difference between the two conversational parties in the use of pragmatic strategies as well as (2) a pragmatic difference between conversations with and without directions – or more generally conversations about topics that are very and those that are less common. Concerning (1), the lesser used strategies, i.e., repair, interruption, multilingual elements, and wrap-ups, might be used more or exclusively by tourism workers, as they function as the experts in this kind of conversation as well as speakers of Croatian and hence are able to include Croatian place names. They ensure tourists understand them by repairing their utterances more frequently than tourists do as their professional success depends on being understood. Concerning the five more commonly used strategies, DMs, SMs, HMs, Reps, and rephrasings, the use of DMs and rephrasings differs only slightly between tourists and tourism workers in both types of conversations (with directions: 1% (DMs) and 1.9% (rephrasings) difference, without directions 2.4% (DMs) and 1.8% (rephrasings) difference). In conversations without directions, the different roles of the two conversational parties are represented in their respective use of two pragmatic strategies: (1) repetitions are used 10.2% more often by tourism workers, likely to stress the information just uttered and to ensure it is correctly processed by the tourists; and (2) HMs are used 15.9% more often by tourists, potentially due to higher processing costs, i.e., they are less familiar with the situation and possibly less fluent and comfortable when using English.

Most interesting for the study at hand, however, are the wrap-ups. As mentioned above, this is the only one of the assessed pragmatic strategies that is used exclusively by tourism workers. Wrap-ups are instances in which the tourism worker interrupts the tourist to answer the question the latter is about to ask or provide the information they are expected to ask for in upcoming questions. These wrap-ups might hint toward the second tendency mentioned above, as they occur considerably more often in conversations that concern the directions to the city center, which hints at the high frequency and increased predictability of which questions will be asked. Staff members can identify the question or even the set of questions that are concerned with this topic, e.g., which bus leaves for the city center, how much is one way, where is the bus stop, where and how do I get tickets, and so on, based on former encounters with tourists. Although the line of questioning might be predictable for tourism workers, the fact that they ‘wrap the conversation up’ appears to be linked closely to the unique context of tourism. In private or business conversations, such wrap-ups would likely be considered impolite and lead to irritation at best and loss of business or sympathy at worst. However, as the employees of the Visitor Centers in Zagreb do not sell anything but answer questions, they can risk anticipating the tourists’ needs and do their job more efficiently with less time spent with each tourist and, consequently, helping more tourists in a shorter amount of time – which is very much appreciated at an airport. When it comes to routines in answering questions, however, tourism workers sometimes choose to be less efficient, and hence more social, than could have been expected.

As discussed above, the brevity and the similar concerns of conversations on directions to the city center result in similarly structured conversations and a somewhat limited range of pragmatic features used. These similar structures and concerns could have easily led tourism workers to prepare and offer the same answer – at least content wise – to every tourist asking a specific question; they could even have developed a routine to answer the most frequently asked questions. The findings of this study, however, show some variation in the answers to such high-frequency questions. The tourism workers answer certain questions, i.e., where a specific bus stops and how to get to a specific location, similarly and might even add further useful information in a wrap-up. More generic questions, such as how to get into the city, however, are answered differently, depending on how they interpret the question and the tourist’s needs. Personal conversations with the tourism workers have offered a first glimpse into the factors that influence their answers. In addition to minimalizing the complexity of the answer based on the English language proficiency of the tourist, i.e., how easily the answer would be understood, personal factors, such as motivation, previous working hours, and biological needs, appear to influence the employees’ choice. Although the answers elicited by asking a question along the lines of how to get into the city center vary to some extent, they all share one critical aspect: they all recommend public or commercial regular transportation services, i.e., the respective bus operated by Zagreb’s public transport services or a shuttle bus operated by a local airline.7 When asked about the difference in their recommendation, one of the local tourism workers stated that, as the shuttle bus provides a direct connection and the municipal transportation would be a little more complex to explain, they tend to only inform about the shuttle bus. Structured follow-up interviews with the respective tourism workers might offer further insights into this issue.

In conclusion, this study has shown the complexity of short conversations in tourism contexts. While English is the language of international tourism, the variety and diversity of speakers, their language repertoires and proficiencies, as well as their communicative purposes, i.e., private vs. professional, and the hybridity of internationally used English must be considered when investigating tourism contexts. It has been found that most pragmatic strategies and structures converge with ELF use in ‘traditional’, i.e., educational, settings while some diverge from them, e.g., wrap-ups. The use of English in tourism interactions is a melting pot of private, professional, practiced, spontaneous, fluent, and basic language use that must be assessed carefully by considering each individual context for an adequate understanding. In tourism interactions, this unique mix is also reflected in the use of pragmatic strategies. Despite the contextual similarity, the importance of the social meaning performed in all interactions is reflected on the form level, for example by the high usage frequency of SMs, as well as on the content level, for example by the varying types of answers to the same question by the same tourism worker. The study has positioned tourism interactions on a continuum between efficiency and sociability, as toursim workers use wrap-ups to be more efficient at times and choose not to use them and engage with the tourists, i.e. being more sociable, at other times. Furthermore, the tourism workers’ communicative and linguistic sensitivity when engaging with tourists with different needs and varying English language proficiencies were reflected in their use of pragmatic strategies. This is a topic that certainly warrants further research.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article can be made available upon request, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Commission of TU Dortmund University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because participants’ information was not elicited. The researcher did not interact with the participants besides asking for consent. Each participant provided informed oral consent before the recording started.

Author contributions

MV-M: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^These findings have to be interpreted against the fact that in the 2011 census, the only language that could be chosen in the used questionnaire was Croatian – other languages had to be added manually (cf., https://web.dzs.hr/Hrv/censuses/census2011/forms/langs/Englezi%20OP.pdf). If the elicitation tool had not been revised, the clear dominance of Croatian in the 2021 census is assumed to represent the government’s bias rather than accurate speaker numbers.

2. ^For an overview of other pragmatic strategies mentioned (cf. Cogo and Dewey, 2012; Cogo and House, 2018; Kaur, 2022).

3. ^I would like to thank the participants of my study, especially the local participants who kindly allowed me to accompany their workday. Furthermore, I am grateful to the Zagreb Tourist Board for their support during my stay in Zagreb and their willingness to allow their employees to participate in and, thus, support my study.

4. ^https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/elan

5. ^The transcription codes relevant for this chapter are: [/]: repetition without correction; [//]: rephrasing; [=!text]: paralinguistic material; | simultaneous speech; +/? interruption of question.

6. ^These numbers exclude co-constructions as they include both conversational parties.

7. ^Only in one instance, the alternative of using a taxi or an Uber is mentioned.

References

Baumgarten, N., and House, J. (2010a). I think and I don’t know in English as a lingua franca and native English discourse. J. Pragmat. 42, 1184–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2009.09.018

Baumgarten, N., and House, J. (2010b). Discourse markers in high-stakes academic ELF interactions: Oral exams. Paper given at the 3d ELF conference, Vienna, May 2010.

Björkman, B. (2011). Pragmatic strategies in English as an academic lingua franca: ways of achieving communicative effectiveness. J. Pragmat. 43, 950–964. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.033

Björkman, B. (2014). An analysis of polyadic English as a lingua franca (ELF) speech: a communicative strategies framework. J. Pragmat. 66, 122–138. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2014.03.001

Bugarski, R. (2004). “Language and boundaries in the Yugoslav context” in Language discourse and Borders in the Yugoslav successor states. eds. B. Busch and H. Kelly-Holmes (Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters), 21–37.

Bugarski, R. (2012). Language, identity and borders in the former Serbo-Croatian area. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 33, 219–235. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2012.663376

Bunčić, D. (2008). “Die (Re-)Nationalisierung der serbokroatischen Standards,” in Deutsche Beiträge zum 14. Internationalen Slavistenkongress Ohrid 2008, eds. Kempgen, S., Gutschmidt, K., Jekutsch, U., and Udolph, U. L. (München: Sagner), 89–102.

Canagarajah, S. (2007). Lingua Franca English, multilingual and language communities, acquisition. Mod. Lang. J. 91, 923–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00678.x

Cogo, A. (2009). “Accommodating difference in ELF conversations: a study of pragmatic strategies” in English as a lingua franca: Studies and findings. eds. A. Mauranen and E. Ranta (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing), 254–273.

Cogo, A. (2010). Strategic use and perceptions of English as a lingua franca. Poznan Stud. Contemp. Linguist. 46, 295–312. doi: 10.2478/v10010-010-0013-7

Cogo, A., and Dewey, M. (2012). Analysing English as a lingua Franca: A corpus-based investigation. London: Continuum.

Cogo, A., and House, J. (2018). “The pragmatics of ELF” in The Routledge handbook of English as a lingua franca. eds. J. Jenkins, W. Baker, and M. Dewey (London: Routledge), 210–223.

Croatian Bureau of Statistics. (2022). 1700 tourism, 2021. Available at: https://podaci.dzs.hr/media/gwcghawn/si-1700_turizam-u-2021.pdf

Croatian Bureau of Statistics. (2023). Census of population, households and dwellings in 2021 – population of Republic of Croatia. Available at: https://podaci.dzs.hr/media/3hue4q5v/popis_2021-stanovnistvo_rh.xlsx (Accessed June 14, 2023)

De Bartolo, A. M. (2014). Pragmatic strategies and negotiation of meaning in ELF talk. EL.LE 3, 453–464. doi: 10.14277/2280-6792/115p

Dewey, M. (2007). English as a lingua franca and globalization: an interconnected perspective. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 17, 332–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-4192.2007.00177.x

Drljača Margić, B., and Vodopija-Krstanović, I. (2018). Language development for English-medium instruction: teachers’ perceptions, reflections and learning. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 35, 31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2018.06.005

Drljača Margić, B., and Vodopija-Krstanović, I. (2020). “The benefits, challenges and prospects of EMI in Croatia: an integrated perspective” in Integrating content and language in multilingual universities. eds. S. Dimova and J. Kling, vol. 44 (Springer, Cham: Educational Linguistics)

Eckert, P. (2006). “Communities of practice” in Encyclopedia of language and linguistics. ed. K. Brown. 2nd Edn. (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 683–685.

ELFA. (2008). The Corpus of English as a lingua Franca in academic settings. Director: Anna Mauranen.

Ennis, M., and Petrie, G. (2019). Teaching English for tourism: Bridging research and praxis. London: Routledge.

European Commission. (2022). Croatia. Available at: http://eurydice.Eacea.Ec.Europa.Eu/national-education-systems/Croatia/population-demographic-situation-languages-and-religions (Accessed June 12, 2023)

Gerritsen, M., and Nickerson, C. (2009). “BELF: business English as a lingua Franca” in The handbook of business discourse. ed. F. Bargiela-Chiappini (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), 180–192.

Gröschel, B. (2009). Das Serbokroatische zwischen Linguistik und Politik: Mit einer Bibliographie zum postjugoslavischen Sprachenstreit. München: Lincom Europa.

House, J. (2003). English as a lingua franca: a threat to multilingualism? J. Socioling. 7, 556–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9841.2003.00242.x

House, J. (2009). Subjectivity in English as a lingua franca: the case of you know. Intercult. Pragmat. 6, 171–194. doi: 10.1515/IPRG.2009.010

House, J. (2010). “The pragmatics of English as a lingua franca” in Handbook of pragmatics. ed. A. Trosborg, vol. 7 (Berlin: de Gruyter), 363–387.

House, J. (2011). “Global and intercultural communication” in Handbook of pragmatics. eds. K. Aijmer and G. Andersen, vol. 5 (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton), 563–390.

House, J. (2012). English as a lingua franca and linguistic diversity. J. English Lingua 1, 173–175. doi: 10.1515/jelf-2012-0008

House, J. (2013). Developing pragmatic competence in English as a lingua franca. J. Pragmat. 59, 57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2013.03.001

House, J. (2014). Managing academic discourse in English as a lingua franca. Funct. Lang. 21, 50–66. doi: 10.1075/fol.21.1.04hou

Hülmbauer, C. (2009). “‘We don’t take the right way. We just take the way that we think you will understand’ – the shifting relationship between correctness and effectiveness in ELF communication” in English as a lingua franca: Studies and findings. eds. A. Mauranen and E. Ranta (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing), 323–347.

Hynninen, N. (2016). Language regulation in English as a lingua Franca: Focus on academic spoken discourse. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Jaroensak, T. (2018). The use of pragmatic strategies in touristic ELF in Thailand [PhD Dissertation]. Portsmouth: University of Portsmouth.

Jaroensak, T., and Saraceni, M. (2019). ELF in Thailand: variants and coinage in spoken ELF in tourism encounters. Reflections 26, 115–133. doi: 10.61508/refl.v26i1.203948

Jenkins, J. (2000). The phonology of English as an international language: New models, new norms, new goals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jenkins, J. (2007). English as a lingua Franca: Attitudes and identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kachru, B. B. (1985). “Standards, codification and sociolinguistic realism: the English language in the outer circle” in English in the world: Teaching and learning the language and literatures. eds. R. Quirk and H. G. Widdowson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press for The British Council), 11–30.

Kalocsai, K. (2011). “The show of interpersonal involvement and the building of rapport in an ELF community of practice” in Latest trends in ELF research. eds. A. Archibald, A. Cogo, and J. Jenkins (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing), 113–137.

Kaur, J. (2009). “Pre-empting problems of understanding in English as a lingua franca” in English as a lingua franca: Studies and findings. eds. A. Mauranen and E. Ranta (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing), 107–125.

Kaur, J. (2010). Achieving mutual understanding in world Englishes. World Englishes 29, 192–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-971X.2010.01638.x

Kaur, J. (2011). Raising explicitness through self-repair in English as a lingua franca. J. Pragmat. 43, 2704–2715. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2011.04.012

Kaur, J. (2022). “Pragmatic strategies in ELF communication: key findings and a way forward” in Pragmatics in English as a lingua Franca: Findings and developments. ed. I. Walkinshaw (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton), 35–54.

Kostic Bobanovic, M., and Grzinic, J. (2011). The importance of English language skills in the tourism sector: a comparative study of students/employees perceptions in Croatia. Almatourism 2, 10–23. doi: 10.6092/issn.2036-5195/2476

Maci, S. M. (2018). An introduction to English tourism discourse. Sociolinguistica 32, 25–42. doi: 10.1515/soci-2018-0004

MacWhinney, B. (2000), The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk, 3rd edn, Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Mauranen, A. (2006). Signalling and preventing misunderstanding in English as lingua franca communication. Int. J. Sociol. Lang. 177, 123–150. doi: 10.1515/IJSL.2006.008

Mauranen, A. (2012). Exploring ELF – Academic English shaped by non-native speakers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Medved Krajnović, M., and Letica, S. (2009). “Učenje stranih jezika u Hrvatskoj: politika,znanost i javnost [foreign language learning in Croatia: policy, science and the public]” in Jezičnapolitika i jezična Stvarnost[Language policy and language reality]. ed. J. Granić (Zagreb: Croatian Association of Applied Linguistics), 598–607.

Meierkord, C. (1996). Englisch als Medium der interkulturellen Kommunikation: Untersuchungen zum non-native−/non-native-speaker Diskurs. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Meierkord, C. (2004). Syntactic variation in interactions across international Englishes. English World-Wide 25, 109–132. doi: 10.1075/eww.25.1.06mei

Mihaljević Djigunović, J. (2013). “Multilingual attitudes and attitudes to multilingualism in Croatia” in Current multilingualism: A new linguistic dispensation. eds. D. Singleton, J. Fishman, L. Aronin, and M. Ó. Laoire (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton), 163–186.

Mortensen, J. (2013). Notes on English used as a lingua franca as an object of study. J. English Lingua Franca 2, 25–46. doi: 10.1515/jelf-2013-0002

Mortensen, J. (2017). Transient multilingual communities as a field of investigation: challenges and opportunities. J. Linguistic Anthropol. 27, 271–288. doi: 10.1111/jola.12170

Mortensen, J., and Hazel, S. (2017). “Lending bureaucracy voice: negotiating English in institutional encounters” in Changing English. eds. M. Filppula, J. Klemola, A. Mauranen, and S. Vetchinnikova (Berlin: De Gruyter), 255–275.

Murata, K. (2015). Exploring ELF in Japanese academic and business contexts: Conceptualization, research and pedagogic implications. New York: Taylor and Francis Inc.

O’Neal, G. (2015). Segmental repair and interactional intelligibility: the relationship between consonant deletion, consonant insertion, and pronunciation intelligibility in English as a lingua franca in Japan. J. Pragmat. 85, 122–134. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2015.06.013

Petričušić, A. (2004). Constitutional law on the rights of national minorities in the Republic of Croatia. European Yearbook of Minority Issues 2, 607–629.

Pietikäinen, K. (2018). Misunderstanding and ensuring understanding in private ELF talk. Appl. Linguis. 39, 188–212. doi: 10.1093/applin/amw005

Pitzl, M.-L. (2005). Non-understanding in English as a lingua franca: examples from a business context. Vienna English Working Papers 14, 50–71.

Pitzl, M. (2018). Transient international groups (TIGs): exploring the group and development dimension of ELF. J. English Lingua Franca 7, 25–58. doi: 10.1515/jelf-2018-0002

Pitzl, M.-L. (2019). Investigating communities of practice (CoPs) and transient international groups (TIGs) in BELF contexts. Iperstoria 13, 5–14. doi: 10.13136/2281-4582/2019.i13.233

Požgaj Hadži, V. (2014). Language policy and linguistic reality in former Yugoslavia and its successor states. Inter Faculty 5, 49–91. doi: 10.15068/00143222

Schegloff, E. A. (2000). When “others” initiate repair. Appl. Linguis. 21, 205–243. doi: 10.1093/applin/21.2.205

Seidlhofer, B. (2004). Research perspectives on teaching English as a lingua franca. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 24, 209–239. doi: 10.1017/S0267190504000145

Stainton, H. (2019). TEFL tourism: Principles, commodification & the sustainability of teaching English as a foreign language. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing.

Sung, C. C. M. (2015). Exploring second language speakers’ linguistic identities in ELF communication: a Hong Kong study. J. English Lingua Franca 4, 309–332. doi: 10.1515/jelf-2015-0022

Watterson, M. (2008). Repair of non-understanding in English in international communication. World Englishes 27, 378–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-971X.2008.00574.x

Wilson, A. (2018). International tourism and (linguistic) accommodation: Convergence towards and through English in tourist information interactions, Anglophonia, 25. Available at: http://journals.openedition.org/anglophonia/1377 (Accessed February 18, 2024)

Wilson, A. (2019). Adapting English for the specific purpose of tourism: a study of communication strategies in face-to-face encounters in a French tourist office. ASp 73, 53–73. doi: 10.4000/asp.5118

Keywords: ELF, Croatia, English in tourism, pragmatic strategies, international communication, conversation structure, international interactions

Citation: Vida-Mannl M (2024) “How can I get into the city center?”—pragmatic strategies at use in international tourism interactions in Croatia. Front. Commun. 9:1407295. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1407295

Edited by:

Gordana Hrzica, University of Zagreb, CroatiaReviewed by:

JoséRuiz Mas, University of Granada, SpainAlcina Sousa, University of Madeira, Portugal

Copyright © 2024 Vida-Mannl. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Manuela Vida-Mannl, bWFudWVsYS52aWRhbWFubmxAdHUtZG9ydG11bmQuZGU=

Manuela Vida-Mannl

Manuela Vida-Mannl