- 1Department of Psychology, University of Kaiserslautern-Landau (RPTU), Landau, Germany

- 2Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

There has been growing interest in research on news-related user comments. Here we conduct the first systematic review of this literature—quantitatively and qualitatively (248 studies)—that covers the entire communication process (content analyses, surveys, experiments). Results indicate a focus on online news articles (vs videos) and little consideration for major social media platforms (Instagram, TikTok). Research often assesses incivility in comments but offers conflicting conclusions on the actual level of incivility in comment threads—and seldom considers how to effectively combat any incivility. We propose four priorities for future work: more comparative and longitudinal approaches; exploring social media and video content; examining platform design, content moderation and artificial intelligence; and implementing measures to reduce incivility and protect the integrity of journalism.

Introduction

User-generated content (UGC) represents an ever-increasing proportion of media content where users evaluate, disseminate and comment on news (Bruns, 2005; Hermida and Thurman, 2008). User comments are the most prominent form of UGC and user participation (Stroud et al., 2016b) and are usually presented below news articles, thus reaching the same audience as professionally journalistic content (Springer et al., 2015).

From the perspective of democratic theory, user participation in comment sections was welcomed in the early 2000s, when online newspapers included user comments underneath news content (Santana, 2011). By 2013, 90% of news platforms in the United States provided a comment section on their website (Stroud et al., 2016a). Many celebrated the benefits of comment sections, suggesting it would usher an era of deliberative democracy (Habermas, 1962; Engelke, 2020) and create new public spaces where people easily and quickly voice their opinions—allowing citizens to understand what others think about issues (Lee and Jang, 2010).

On the other hand, others have been pessimistic (including journalists; Bergström and Wadbring, 2015) arguing that user comments do not enrich public discourse and comment sections do not automatically promote healthy democratic exchange. User comments can spread negativity (Winter et al., 2015), misleading or false information (Anspach and Carlson, 2020), and extreme populist ideas (Blassnig et al., 2019). Further, comments can include uncivil language (Anderson et al., 2014) that insults others (i.e., dark participation, Frischlich et al., 2019).

Researchers also recognized these user comment sections impact others who read comment threads—swaying attitudes (Lee and Jang, 2010), risk perceptions (Anderson et al., 2014), public opinion perceptions (Lee et al., 2021) and behaviors (Hsueh et al., 2015). Importantly, many recognized user comments can hurt the reputations of journalists and media platforms—making them seem less credible and trustworthy (Walther et al., 2010; von Sikorski and Hänelt, 2016; Naab et al., 2020). Some news organizations like USA Today, Reuters and NPR have responded by dropping comment sections from their websites.

Given the disconnect between what many hoped news-related user comments could do to help society and public discourse (Habermas, 1962, 2022; Engelke, 2020), and findings suggesting news-related user comments may be detrimental, it is imperative to comprehensively assess current understandings of news related user comments (and their effects).

Over the past two decades, the number of quantitative studies focusing on news-related user comments has exploded and the large number of results now obscures central findings. Researchers have begun to present initial overviews of sub-areas of the field (e.g., on the content of user comments), but an up-to-date and systematic overview, from the content to the effects of user comments, is lacking.

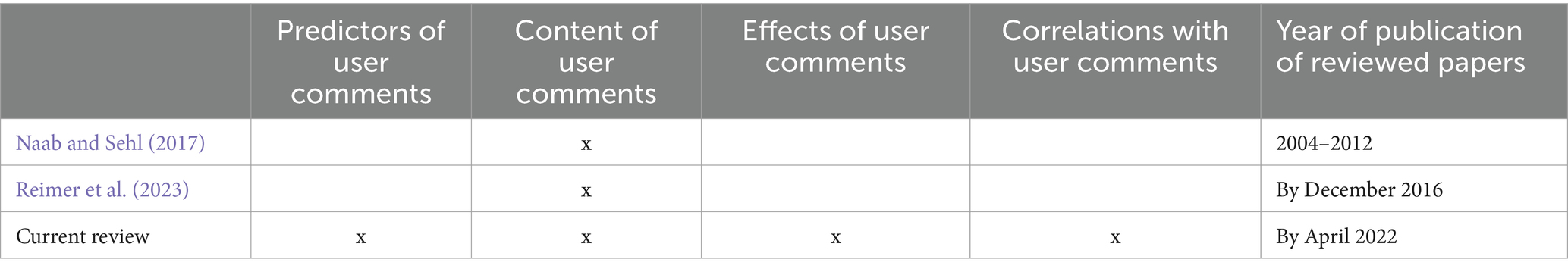

Researchers have taken first steps in systematically examining findings related to user comments. Naab and Sehl (2017), conducted a systematic review of content analyses regarding user comments published in nine academic journals between 2004 and 2012. They explored processes such as the theoretical frameworks employed by scholars and the modality examined (e.g., text vs. moving image). Reimer et al. (2023) conducted another systematic review of content analyses of user comments, primarily focused on methodology. They found an overabundance of analyses from Anglo-American newspapers and a focus on incivility.

While these systematic reviews provide valuable insights into user comments research, and others have added to the literature through non-systematic reviews of user comments (e.g., Ksiazek and Springer, 2018; Naab and Küchler, 2023), we suggest it is essential to systematically re-assess the current state of knowledge in the literature. Given the fast paced and changing media market (Newman et al., 2023), it is essential to re-examine current understandings of user comments frequently. However, previous systematic reviews included papers published by 2012 in nine pre-selected academic journals (Naab and Sehl, 2017) and by 2016 (Reimer et al., 2023)—meaning any recent insights have yet to be considered within a systematic review. Further, the systematic reviews focused on current understandings of content analyses (i.e., what comments look like) and less so on many other questions related to comments. For example, what commenting is related to, and the effects of commenting.

In the current research we are the first to conduct a broad systematic review—quantitatively and qualitatively oriented—where we consider the contents of user comments, motives that predict commenting, demographic factors like gender, news use, and levels of political participation that correlate with user comments, and effects of news-related user comments. See Table 1. Additionally, we report our systematic review in-line with PRISMA guidelines for writing reviews (Page et al., 2021).

Table 1. Comparison of previous systematic reviews of user comments as compared to current systematic review.

While past reviews provide meaningful insights, questions regarding news-related user comments remain. In the current research, we close these gaps and answer three research questions. RQ1 is quantitatively oriented and asks: How can the current state of research on news-related user comments be characterized in terms of (a) the development of the research over time, (b) the demographics of samples, (c) and the methods used? RQ2 is qualitatively oriented and asks: What do we know about news-related user comments regarding (a) the content of comments (e.g., are user comments frequently uncivil?) (b) what factors correlate with commenting (e.g., is commenting associated with news use?) and (c) the effect of comments (e.g., can user comments shape others’ attitudes?). The third research question (RQ3) is both quantitatively and qualitatively oriented and asks: How are news-related user comments examined in the literature?

Methods

For this systematic review, we conducted analyses using a 2-stage approach. In Stage 1, we determined which papers fit the criteria for being included in our review using a systematic coding approach. In Stage 2, we systematically coded papers (a quantitative approach), and extracted key findings from each paper (a qualitative approach). Further details about each step are found below.

Stage 1: determining inclusion criteria

To answer our research questions, we conducted a systematic literature search using Web of Science (aligned with previous systematic reviews; see Ahmed and Matthes, 2017; von Sikorski, 2018; Tsfati et al., 2020; Kubin and von Sikorski, 2021) to identify potentially relevant articles. Our search terms focused on user-generated comments and news media. Example search terms include: “user comment,” “reader comment,” “online comment,” and “news,” “news article,” “press coverage.” We searched for articles that referenced both user comments and news—checking article titles, abstracts, and the keywords of articles. Through this search process (conducted on April 4th, 2022),1 553 articles were identified that contained a combination of keywords from both categories.

Our Web of Science search was complemented by also considering articles from other available reviews about news-related user comments (Ksiazek and Springer, 2018; Reimer et al., 2023). In this step, we included articles that were accessible through Web of Science that were not already included in our search query (N = 57).2 Reasons why these papers were not included related to divergent terminology used by authors (e.g., using the term “post” rather than “comment” in the abstract; Colley and Maltby, 2008). This resulted in a total of 610 papers that were further examined regarding whether they should be included in this review.

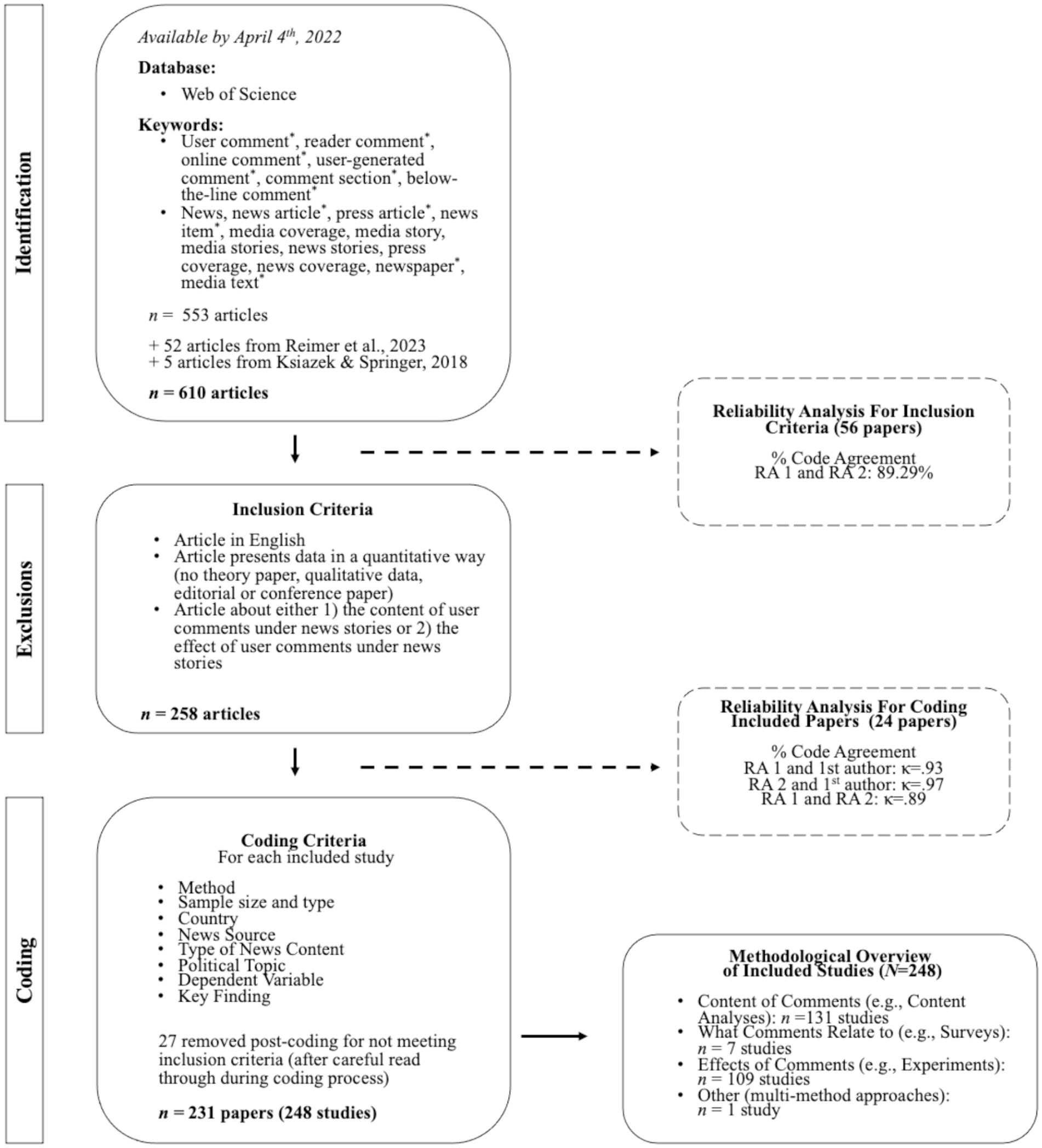

In a next step, two trained research assistants independently assessed a total of 610 papers (based on instructions provided in a codebook; see Appendix A) to determine which papers would be included in the systematic review. Articles were included in the sample when: (a) the article was in English, (b) the article was quantitative in nature and published in an academic journal, and (c) the article focused on the content of comments, constructs that correlated with user comments or the effects of news-related user comments. To ensure reliability, approximately 10% of the identified research papers were assessed by both research assistants (there was 89.29% agreement between research assistants). Based on our exclusion criteria we identified 258 articles that should be coded in this systematic review (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow chart of paper identification, inclusion determination, coding criteria, reliability analysis and the methodology utilized in papers included in systematic review.

Stage 2: coding included papers

Two research assistants coded the included papers (N = 258) on a variety of dimensions following a systematic codebook (see Appendix B). Both research assistants were extensively trained3 and read through each paper—coding a variety of quantitative and qualitative categories for each relevant study within a paper. Each research assistant was responsible for independently coding half of all papers (i.e., approximately 130 papers each). Key quantitative categories include year of publication, study method, country of sample, the news source, type of news content, whether the study was focused on news or social media, if on social media—which social media site was used, and whether the paper explicitly studied incivility.4 Research assistants also reported the topics being considered within the study (e.g., what topic the news content discussed). A more qualitative category was related to key findings from each study.

To ensure reliability, both coders and the 1st author coded the same 24 papers. There was high reliability in codes between the 1st author and RA 1 (κ = 0.93),5 the 1st author and RA 2 (κ = 0.97), and between RA 1 and RA 2 (κ = 0.89). Reliability analysis indicated interrater reliability was moderately to strongly reliable. More information about reliability can be found in Appendix C. All articles included in this review, their codes, and codebooks can be found here: https://osf.io/swx76/?view_only=30aa778596aa4c469634fe84a3de63bb. We encourage other scholars to use these materials in future research on user comments.

During the coding process, we recognized some papers (N = 27) that were originally included in this systematic review did not actually qualify (e.g., because the article was more qualitatively focused than originally thought or because the comments were not news-related). This was determined after a more careful and complete read through during the coding process—231 papers (248 studies) were included in analyses.

Results

We present both quantitative and qualitative results. Due to space limitations, we cannot report every finding from every paper, but provide a broad scope for understanding the key areas of agreement (and disagreement) between scholars, key methods and perspectives, and overarching patterns (and gaps) in current understandings of news-related user comments.

Quantitative analyses

Year of publication

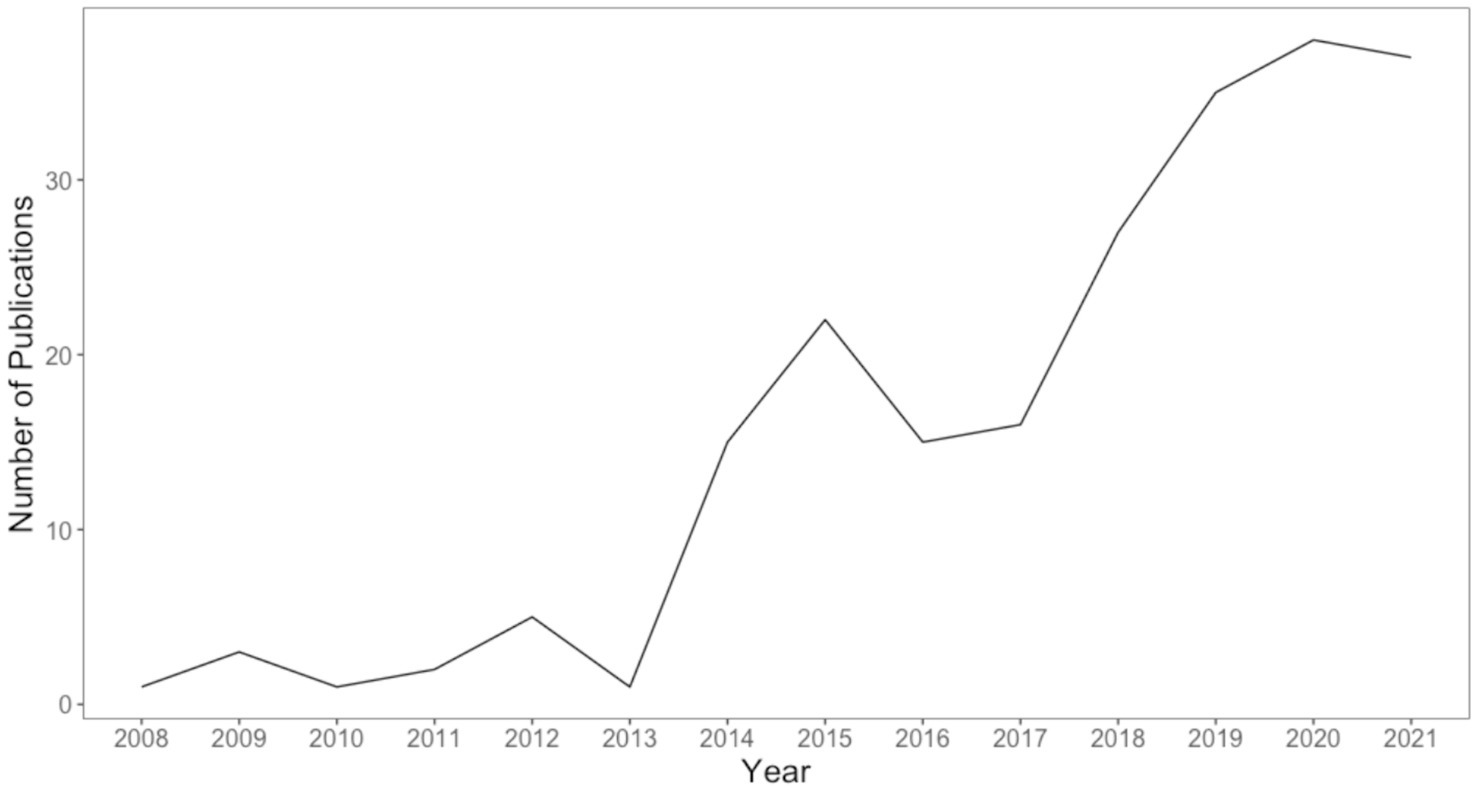

We answer RQ1a (i.e., assessing development of research over time), by assessing when articles on news-related user comments were published, results revealed growing interest in this research. The earliest article was published in 2008—since then there has been exponential growth in publications. See Figure 2.

Figure 2. Number of publications on news-related user comments per publication year. For papers published as Early Access papers on the day of retrieval (April 4th 2022), we checked when those papers were published first online and included that information in the graph above. Of these early access papers; 4 papers were published first online in 2020, 8 in 2021, and 9 in 2022. We do not depict the papers published in 2022 as we only collected papers published by April 4th 2022–thus we had incomplete data for 2022. Therefore 4 published papers (and 9 early access papers) are excluded from this figure.

Sample characteristics

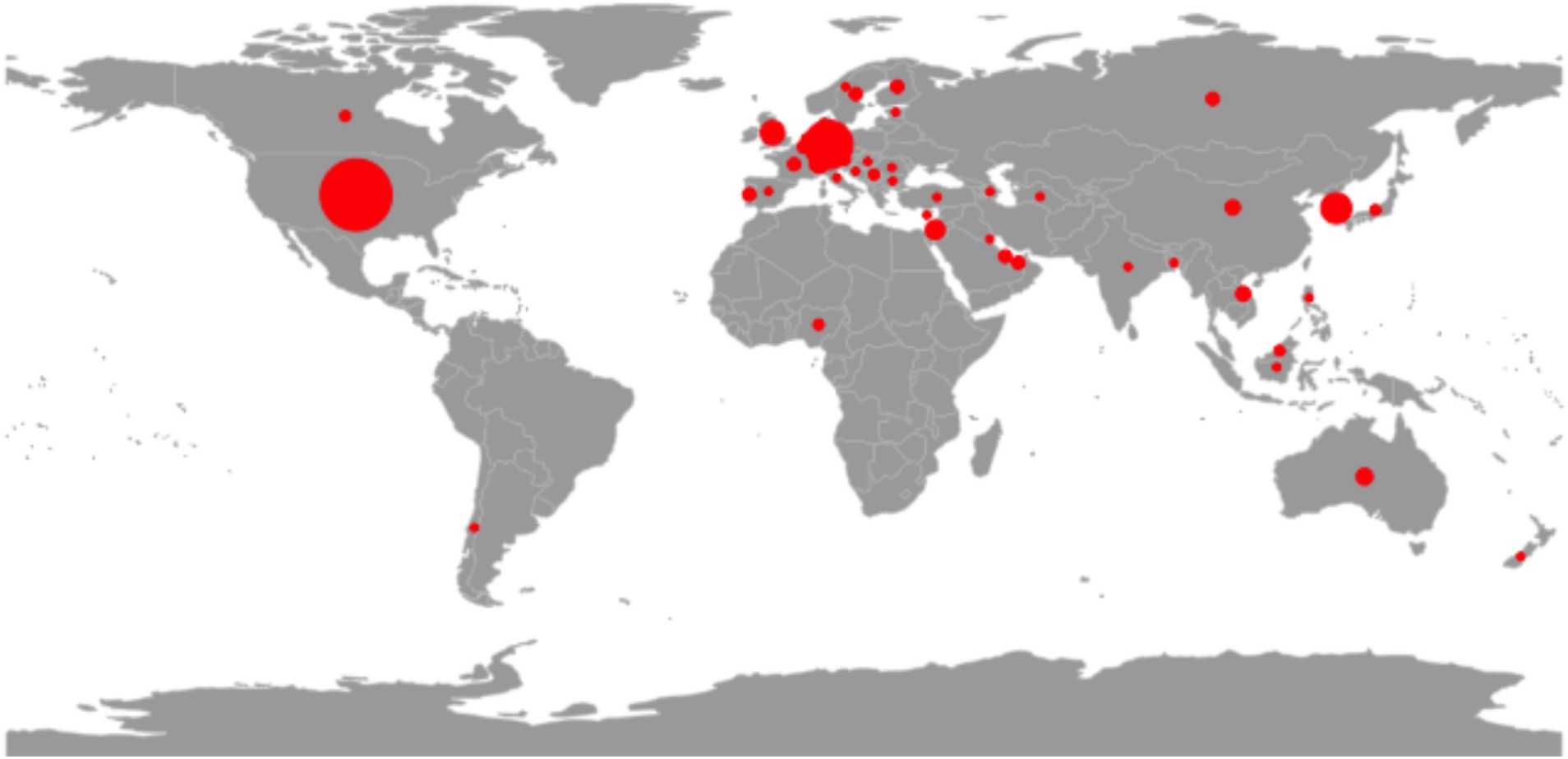

To assess RQ1b (i.e., the demographics of samples in user comment research), we next focused on where samples came from. We found an overabundance of research conducted in Western societies—especially in the United States (N = 100) and Germany (N = 46), but also found numerous studies in South Korea (N = 18). While there was a lot of research conducted within Western societies––there was still great diversity in samples (e.g., in India, Israel, China, Russia, and Chile)—though there were few samples from the Global South. See Figure 3.

Figure 3. Distribution of samples across countries. Red circles represent samples from that country, the larger the circle the more samples from that country. 13 studies did not provide clear information regarding the country the sample came from and 7 studies included worldwide samples (e.g., recruiting participants through the Internet). These studies were not included in the above map.

Methodology

Answering RQ1c (i.e., regarding methodology), we found that studies exploring news-related user comments frequently used content analyses (131 studies, 52.82%), followed by experiments (109 studies, 43.95%), and then surveys (7 studies, 2.82%).

News source

To answer RQ3 (i.e., how news-related user comments are examined in the literature), we explored what kinds of news sources (and their comments) were examined. Most studies (221 studies, 89.52%) solely considered news articles (and their accompanying user comments). Of which, only 49 (22.17%) assessed effects in non-Western samples. Thirteen studies (5.24%) considered news videos (e.g., TV content) and their accompanying comments, though only 2 of these studies came from non-Western samples (15.38%). Some studies (13 studies, 5.24%), considered a variety of news sources within a given study (e.g., consider both news articles and TV news).

Traditional news vs. social media news content

To further answer RQ3, we coded for whether researchers considered comments under news content on a news site or social media. Results indicated 72.18% of studies (N = 179) focused solely on traditional news content, 19.35% of studies (N = 48) focused solely on news media content on social media (e.g., news article posted to Facebook) and 6.85% of studies (N = 17) considered both social media and traditional news media content.

Social media platforms

Of the studies considering news content on social media (N = 65), most assessed news shared on Facebook (N = 52, 80.00%), though only 5 of those studies that focused on Facebook used non-Western samples (11.54%)—a serious gap in the literature given Facebook’s much higher prevalence in non-Western societies (Statista, 2024). Six studies considered content on Twitter (9.23%) (only 1 of which was a non-Western sample), only 2 studies (3.08%) considered news-related user comments on Instagram (1 was a non-Western sample), and 10 studies explored content on YouTube (15.38%), 2 of which focused on non-Western samples. There were several studies (4 studies, 6.15%) that used less well-known social media platforms (e.g., Vkontakte; Toepfl and Litvinenko, 2021). No studies explored user comments under news content on TikTok. These results (in part) answer RQ3 by explaining the contexts and places where user comments are frequently assessed.

Outcome measures

We also coded whether or not studies focused on questions related to the incivility of user comments—believing this could be a key outcome variable. Results suggested a sizeable proportion of studies did research incivility (N = 72, 29.03%). This outcome measure is discussed more in the qualitative section.

Qualitative analyses

In addition to our quantitative analyses, we also took a more qualitative approach in understanding the topics and themes of included studies to further assess RQ2 and RQ3.

Diversity in news and user comment topics

There were a variety of topics discussed in the news content (and comments) across studies—providing some partial insights in RQ3 (i.e., how user comments are examined in the literature). Topics ranged from political (elections; Saldana and Rosenberg, 2020) to apolitical topics (celebrity news; Van den Bulck and Claessens, 2014; sports; Waddell, 2020). We outline some key topics frequently studied below.

Many studies considered hot-button issues in the news. Examples include climate change (e.g., Walter et al., 2018), gun policy (Stroud et al., 2015; Gearhart et al., 2020), and immigration (e.g., Blassnig et al., 2019). Many studies also considered social issues like LGBTQ adoption rights (Wang, 2020) and abortion access (e.g., Chen and Ng, 2017).

There was a heavy focus on health-related topics. Many considered vaccinations (Masullo et al., 2021), mental health care (Cabrera et al., 2018), and disease outbreak (Rodin et al., 2019). Some news content focused on scandals (von Sikorski and Hänelt, 2016).

Finally, many studies considered news content (and comments) about science communication and education. Examples of science communication include reports on research about differences between men and women’s brains (O’Connor and Joffe, 2014) and diabetes (Vehof et al., 2019). In terms of education, scholars considered laws for schools (Lee, 2012), lawsuits against schools (Sherrick and Hoewe, 2018) and appropriate conduct between educators and students (Jahng, 2018). Taken together, and answering RQ3, there is a great variety of contexts where user comments are analyzed.

Key results from user comments research

To understand the overarching themes of results across studies, and to answer RQ2, we next break down results into three subsections: the content of comments (RQ2a), what factors correlate with comments (RQ2b), and the effects of comments (RQ2c).

The content of user comments

To answer RQ2a, we first qualitatively examined all content analyses–exploring key findings related to the contents of comments.

Incivility

Many content analyses explored incivility, examining what drives incivility and the frequency of incivility in comments. Some research suggests when there are more sources referenced within a news article and there is journalistic participation in comment sections, people leave fewer uncivil comments (e.g., Ksiazek, 2018). Incivility was common under news stories about politics (Szabo et al., 2021). Further, there was consistent evidence that anonymity on platforms drives incivility (Ksiazek, 2015).

Others explored whether incivility varies by platform. Researchers found conservative news and local news (as compared to liberal and national news) tends to include more uncivil comments (Su et al., 2018). Others found uncivil commenting may be more common in conservative news (vs. liberal news) (Chen et al., 2019). These results suggest conservative media may insight greater incivility in user comments.

Another important consideration that had little attention is whether there are societal differences in commenting uncivilly. In one study, comments under Chilean news were found to be especially uncivil (and more so than comments under news from the Global North; Saldana and Rosenberg, 2020). In another analysis, uncivil comments occurred more often in majoritarian (rather than consensus-based) democracies (Jakob et al., 2023)6. These results indicate societal differences may be a key factor for understanding the incivility of comments—but more research is needed to explore these differences.

A looming question is whether incivility is increasing over time and in its pervasiveness. Again, there has been little research focused on this longitudinal perspective, though in one study in Hungary between 2017 and 2019, researchers found incivility in comments remained stable over time (Szabo et al., 2021).

Some scholars suggest incivility in news-related user comments is not widespread (e.g., Aji and Sapto, 2020). In one study, comments posted under news videos on YouTube showed higher levels of civility than hostility (Ksiazek et al., 2015). However, other research suggests incivility is common in online discussions (e.g., San Pascual, 2020). Others find that incivility is more common than other more deliberative forms of commenting (Chen et al., 2020). These results suggest an ongoing debate in scholarly research regarding incivility.

Positive and negative comments

Some content analyses examined the positive and negative sentiment of comments. For example, people responded more positively to news articles when those articles discuss cures for diabetes as compared to preventative measures for diabetes (Vehof et al., 2019). These findings are in-line with other research suggesting whether people respond to news content positively or negatively is highly dependent on the topic itself (e.g., Cabrera et al., 2018). Several studies made inferences about peoples’ attitudes towards specific issues depending on whether they responded positively or negatively to news content. For example, to understand how people feel about the European Union (Galpin and Trenz, 2019).

Additional themes within the content of user comments

While many studies focused on the incivility or sentiment in user comments, others found that commenters often discuss themes or topics that are seemingly disconnected or unrelated to the news content itself (e.g., Jaques et al., 2019). However, other research disputes this idea (Lee and McElroy, 2019).

In some research, scholars focused on how people feel towards specific policies or political issues by analyzing the content of their comments. For example, exploring how people felt about Driving Under the Influence (DUI) enforcement (Connor and Wesolowski, 2009), migration issues (Ademmer et al., 2019), beliefs about organic foods (Danner and Thøgersen, 2022), national safety and security (Bogain, 2020), celebrity suicide (Rosen et al., 2020), vaccine effectiveness (Lei et al., 2015), and trigger warnings (George and Hovey, 2020).

Several studies explored the use of narratives and facts and data within user comments—a promising area of research as past work suggests narratives can be persuasive (e.g., Oschatz and Marker, 2020) and help bridge divides between people who disagree (Kubin et al., 2023). Scholars find narratives are commonplace in comment threads (Cabrera et al., 2019) and that many commenters discussed personal opinions rather than facts or data (Lee and McElroy, 2019).

The predictors of user comments

We found that other scholars assessed the predictors of user comments and their contents (e.g., what causes people to comment, which factors shape certain types of commenting behavior). In these studies, authors examine the content of user comments (e.g., content analyses), but focus on what predicts this content.

How news shapes commenting

Some research explored how the type of content in news media can influence if and how people comment—considering the news content itself or differences across news platforms (e.g., Stroud et al., 2016a)— key considerations for understanding commenting behavior (Szabo et al., 2021; Aldous et al., 2023). Some found that news content about political and social issues are especially likely to be commented on (Tenenboim and Cohen, 2015), and that sentiment and polarizing language in news media influences commenting behaviors (Arapakis et al., 2014). Additionally, news events that have geographic proximity to readers increases commenting behavior (Maier, 2015), but there is no evidence of differences in volume of comments below hard and soft news (Ksiazek et al., 2016). However, understanding when people are likely to comment is complex as others have found that distributions of which types of news content people comment on can differ across news media sources (Ürper and Çevikel, 2016), and may be dependent on whether news reports are in-line with readers’ views (Kim et al., 2021).

In terms of the potential differing effects of news platforms (or news sources) on comments, there is less research. Some suggest news outlets with larger reach are more likely to have comment sections and are more likely to have numerous comments below their content (Stroud et al., 2016a). Multiple studies also explored differences in commenting across platforms—finding meaningful differences between news sites (Esau et al., 2017).

Not only can news content and platforms influence when people write comments, but they also shape opinions expressed in comments. Multiple studies found comments mirrored the views presented in news content (e.g., Lien, 2022)—though others find this may not be the case (e.g., Holton et al., 2014), and that comment sections may push back against media portrayals (e.g., Taylor et al., 2016).

Demographics and motives of commenters

Other studies explored who comments (and the motives for why they do it). Results indicated that while women participate less than men and tend to write more civil comments than men, women still receive similar numbers of uncivil replies as men (Küchler et al., 2023). Further, women are more likely to leave comments under news related to social issues and celebrities whereas men often leave comments under news about politics and sports (Lee and Ryu, 2019). There was evidence for differences in where people comment depending on age. People in their 30s and 40s are more likely to post comments than other age groups and teenagers are especially unlikely to comment (Lee and Ryu, 2019).

Other scholars explored how political ideology may shape user comments. For example, liberals were more willing to include cross-cutting justifications and questions within their comments than conservatives (Freelon, 2015), and moral disengagement was significantly more common in comments on right-wing (vs. left-wing) newspapers (Woods et al., 2018). The political slant of user comments in conservative media paralleled news outlets’ political leaning; yet, a similar pattern was not observed in progressive medias’ comment sections (Han et al., 2023). Taken together, these results suggest demographic considerations are important for considering who comments under which news content.

Based on analyses of comments, scholars have also pointed to peoples’ motivation for commenting as connected to their motives for information sharing, entertainment, and voicing disapproval (Otieno et al., 2021). Several scholars showed that comments can also be used as a tool to counter public opinion. For example, multiple studies found that minority groups (e.g., political movements) can make up large majorities of comments sections in leading newspapers’ comments threads—making their ideas potentially powerful in countering majority opinion (e.g., De Kraker et al., 2014; Toepfl & Piwoni, 2015).

A few studies explored the differences between frequent and infrequent commenters. Some found that frequent commenters are more civil (Coe et al., 2014), but others found frequent commenters are less likely to be civil (Blom et al., 2014). Others find when ones’ own incivility is reaffirmed by others (e.g., by up voting this content), they are more likely to continue commenting uncivilly (Shmargad et al., 2022).

Downstream consequences in comments threads

Some content analyses also explored the consequences of comments in terms of how they shaped further commenting. Results indicate populist themes (Blassnig et al., 2019), and controversial comments (Ziegele et al., 2014) all drove others to comment. On the other hand, comments that sowed doubt were less popular and were not recommended as frequently as other types of comments (Evans et al., 2023).

Correlates of user comments

As noted earlier, very few studies were survey based (i.e., correlational), meaning there are still many gaps in our understanding of what factors are correlated with news-related user comments (answering RQ2b). One study found that commenting was positively associated with political participation (Brundidge et al., 2014). Others focused on how perceptions of user comments are related to who people believe is responsible for moderating user comment content (Riedl et al., 2021). Another study found sadistic personality traits were more associated with incivility in user comments (Beckert and Ziegele, 2020).

The effects of user comments

We also qualitatively examined insights from experimental research—exploring the effect of comments to answer RQ2c.

Incivility

In experiments focusing on the consequences of user comments, many scholars focused on how uncivil comments influence others’ attitudes and perceptions—there was clear evidence that incivility was associated with negative effects. Readers were more likely to have hostile cognitions (Rösner et al., 2016), discussions in online threads were less deliberative (Lück and Nardi, 2019), caused negative emotions and aggressive intentions (Chen and Lu, 2017), and increased perceptions of attitude polarization in society (Hwang et al., 2014).

There was nearly consistent evidence that uncivil comments provoked negative perceptions of news content and journalists. Uncivil comments reduced perceptions of journalistic quality (Weber et al., 2019) and credibility (Searles et al., 2020; Masullo et al., 2023) whereas civil comments increased credibility of news outlets (Masullo et al., 2023). However, one study suggested uncivil (vs civil) comments did not influence participants’ perceptions of the credibility of the news story (Kim and Chen, 2021). Uncivil comments invoked negative attitudes towards the editorial and pushed people away from the editorial’s point of view (Liu and McLeod, 2019). Journalists can deal with uncivil comments using content moderation—however there are consequences of this as well. While uncivil comments in moderated environments are less likely to cause perceptions of news article bias (Yeo et al., 2019), some evidence suggests this is only the case when threads are moderated by machines (rather than journalists; Wang, 2021)—suggesting artificial intelligence may be a helpful tool to combat the negative effects of incivility in user comments.

Uncivil comments also shaped behavior. People were more likely to engage with uncivil comment threads (e.g., Kim and Park, 2019)—and react negatively towards them (e.g., Chen and Ng, 2017). One study found conservatives (but not liberals) were more likely to engage with uncivil comments when those comments discussed politically divisive issues (Su et al., 2021). Others found that civil comments also increased engagement in discussions (Molina and Jennings, 2018).

Thoughts about uncivil commenters tended to be negative. People believed commenters writing uncivil comments should be censored or moderated (Wang and Kim, 2020; Naab et al., 2021), and information conveyed through uncivil comments was less trustworthy (Graf et al., 2017) than other types of comments—though other research suggests people still believe these comments will be persuasive to others (Wang and Kim, 2020). Further, other research suggests people see uncivil comments from in-group members as less uncivil than uncivil comments from out-group members (Kim, 2018). Overall, there is a strong focus on research examining the effects of uncivil comments; future studies could shed further light on the effects of civil news-related user comments.

News evaluations

Beyond the many studies that suggested uncivil comments can negatively affect attitudes towards news content and journalists (Weber et al., 2019; Searles et al., 2020; Masullo et al., 2023), others have found that user comments shape evaluations of news media (e.g., Clementson, 2019). In terms of attitudes towards the news platform, results indicated it was beneficial for journalists to respond directly to commenters, as this increased positive evaluations (Masullo et al., 2022). News coverage with positive user comments was evaluated more positively than news coverage with negative comments (Dohle, 2018). Further disrespectful comments led readers to view the editorial more negatively (Liu and McLeod, 2019).

In terms of news credibility, people were more likely to question the credibility of the news source when comments suggested it was “fake news” (Jahng et al., 2021), or included negative sentiment (Waddell, 2018). Also, mixed comments (a mix of positive and negative comments) negatively affected readers’ perceived quality of a news article (von Sikorski and Hänelt, 2016). News articles were seen as less credible when a comment critiqued the news—but only when that comment was also “liked” by other readers (Naab et al., 2020). Others found no effect of news credibility based on whether comments were present or not (Marchionni, 2015).

There was little research exploring how comments affect perceived news bias. In one experiment, participants who saw like-minded comments (i.e., comments that agreed with the news story) perceived the news as less biased (Gearhart et al., 2020). People also viewed news content as less trustworthy when negative comments were present (Awobamise and Jarrar, 2021).

In terms of persuasion, comments reduced the third person effect (i.e., thinking others would be more influenced by the news article than oneself) (Chung et al., 2015). Further, those who read opinion challenging articles with comments in-line with the article’s view, perceived the article as more useful (Jahng, 2018).

Few considered over time effects regarding how comments shape perceptions of news. In one study, results indicated user comments can reduce the persuasion of a news article in the short (but not long) term (Heinbach et al., 2018). Another study found order effects and evidence for a negativity bias (i.e., interaction effect) showing that exposure to negative (vs positive) comments after (vs before) a news article decreased people’s journalistic quality perceptions (Kümpel and Unkel, 2021).

Congruent vs incongruent comments

Research indicated readers had more positive evaluations of comments that were pro-attitudinal to their beliefs (Petit et al., 2021). People also assessed in-group commenters more favorably than outgroup commenters—but only when in-group members also held a similar issue position to the participant (Kim, 2018). People with strong opinions were more likely to comment on counter-attitudinal threads (Duncan et al., 2020).

Participants perceived news-congruent user comments as more credible and better argued than comments disagreeing with news content (Kunst, 2021). Others found whether comments were congruent or not with a news story shaped perceptions of the issue discussed in that news article, especially when comments came from high-status commenters (von Sikorski, 2016).

Many studies considering (in)congruent comments focused on how these comments shape public opinion perceptions and political polarization. For example, Lee et al. (2021) showed that participants perceived both public opinion and the news tone to be more congenial to their own position when they were exposed to opinion-reinforcing (vs. opinion-challenging) news-related user comments, which (indirectly) increased opinion polarization.

Other research found those who read news related user comments not in-line with their own personal views, believed that public opinion disagreed with their own views and also held greater hostile media perceptions—but this was only true for people with higher levels of ego-involvement (Lee, 2012). Contrarily, other research informed by spiral of silence theory (Matthes et al., 2018) found incongruent user comments did not shape perceptions of public opinion, but rather made participants believe their opinion was in the minority of this particular news source (Yun et al., 2016).

Positive vs negative comments

Other research focused on the sentiment of user comments and how this impacted attitudes and perceptions. News articles about scandals including comments with negative sentiment towards the scandalized individual, were associated with readers seeing the scandalized individual as more responsible (von Sikorski and Hänelt, 2016). However, negative sentiment towards news content itself can also have implications for how people see news. Such comments can reduce the credibility of news (e.g., Waddell, 2018).

Positive and negative comments can also shape how people feel both about society (e.g., public opinion climate; Waddell, 2020), and specific issues (e.g., negative comments can reduce issue importance; Waddell, 2018) and shift peoples’ attitudes (Winter, 2019). Importantly, user comments also shape how people view others. In one study, exposure to positive comments reduced prejudice, the beneficial effects of positive comments were present even one week later—suggesting stability in this attitude change (Stylianou and Sofokleous, 2019).

Platform design, moderation, and anonymity

Fewer experiments explored how the design of the online commenting spaces shapes effects. Some research suggested that when readers were aware news sites moderate their comment threads (and that some comments are deleted), it can make readers less likely to agree with the news content (Sherrick and Hoewe, 2018)—a potential backfire effect of news platforms attempting to moderate comments. Further, others have focused on developing strategies to increase user engagement, finding that allowing users to categorize their viewpoints encourages more commenting (Peacock et al., 2019). Others studied the effect of organizations and companies responding within comment threads, finding it can increase their reputation (Spence et al., 2019), and credibility (Lin et al., 2019)—suggesting interactions within comment threads can be advantageous for organizations.

Commentor anonymity is also an important factor to consider in user comments research—though there is little research on this topic. People are more likely to share views in comment threads when they are anonymous (Wu and Atkin, 2018). However, other research found that men (but not women) are more likely to respond to comments when they are anonymous (Suh et al., 2018).

Discussion

In this systematic review, we analyzed articles assessing news-related user comments. We find a growing interest in this topic, with many articles being published after the systematic reviews of Reimer et al. (2023)—which analyzed papers published by 2016, and Naab and Sehl (2017)—which analyzed papers published by 2012. This growth in recent research emphasizes the need for our re-assessment of the literature. Additionally, previous systematic reviews focused on content analyses of user comments—we go beyond that by also considering the correlates and effects of user comments through also examining correlational and experimental research. Based on our review, we formulate several implications for research and digital journalism practice and have 4 take away messages.

Steep increase in studies, but lack of comparative and longitudinal approaches

Our analyses suggested a steep increase in research on user comments. One explanation for this increasing interest could be related to the growing use of social and digital media for news (Newman et al., 2023), and the growing pervasiveness of user comment threads in news content (e.g., Stroud et al., 2016b). We also find great diversity in the countries considered in user comment research—though more data is still needed from non-Western countries. However, few compare user-comments cross-culturally (or overtime)—making it difficult to infer whether the content, corollaries, and effects of news-related comments are universal or societally specific or have long-lasting effects. We encourage future research to take a more cross-cultural and longitudinal perspective in understanding news-related user comments.

Stronger focus on social media and video-based content

Research was narrow in terms of the type of news content (and comments) being assessed. Most studies considered text-based news content (e.g., online news articles), rather than video-based content—content frequently used on both online news platforms and social media (see Newman et al., 2023). In line with this, more than 70% of the studies examined traditional digital news. In contrast, less than 20% of studies examined news-related user comments on social media. Further emphasizing this point is that only two studies assessed news-related user comments on Instagram (Toepfl and Litvinenko, 2021; Aldous et al., 2023) and none considered TikTok—both visual-based platforms that many increasingly use to access news content (Newman et al., 2023). Future research should expand analyses to consider video-based news content (see Walther et al., 2010) and a more diverse set of social media platforms to gain a clearer understanding of the content (and effects) of user comments when presented in social media contexts.

Regarding for platform design, content moderation and artificial intelligence

Further research needs to assess the influence of platform design in comment threads, particularly regarding the role of anonymity. While some suggest anonymity in comment sections negatively influences comments (e.g., making them more uncivil; Ksiazek, 2015; see also the online disinhibition effect, Suler, 2004), other findings revealed that anonymity increased the likelihood that people share their views in a comments thread (Wu and Atkin, 2018). Many questions remain, for example, understanding the psychological mechanisms for why anonymity drives people to engage more uncivilly.

One way, journalists can deal with these uncivil comments is via content moderation. However, while some research reveals that uncivil comments in moderated environments are less likely to cause perceptions of news article bias (Yeo et al., 2019), users may feel confused or even frustrated when journalists use content moderation systems that remove content without informing people about particular reasons for content removal (Myers West, 2018), sometimes interactive or motivational moderation techniques may be more beneficial (Stockinger et al., 2023).

Further, content moderation of news-related user comments by journalists can drive negative perceptions of news media platforms, for example negatively influencing the credibility of a news story (Wang, 2021). In this context, a promising new line of research shows that artificial intelligence (AI) may be one way for journalistic organizations to deal with uncivil user comments, while simultaneously protecting news credibility. Wang (2021) showed that news bias was reduced when uncivil comments were moderated by AI (vs a human journalist). Future research should consider new possibilities offered by AI and examine these in the context of user comments. For example, understanding the psychological mechanisms for why artificial intelligence can reduce perceived news bias better than journalists.

Search for measures to reduce incivility and negative impact on digital journalism

While many explore incivility in user comments (in terms of both content and effects), there is one glaring gap in the literature—how we can motivate people to be less uncivil in their comments. The literature indicates uncivil comments have many negative consequences, for example, driving negative emotions and aggressive intentions (Chen and Lu, 2017), fostering more negative attitudes towards journalism (Liu and McLeod, 2019; Weber et al., 2019; Searles et al., 2020; Masullo et al., 2023); but also (see Kim and Chen, 2021) and promotion of (political) polarization (Hwang et al., 2014). Further, research suggests uncivil comments tend to invoke further uncivil comments by others (see Kim and Park, 2019)—potentially reducing the quality of online conversations. Based on these findings, we suggest future research should find new ways to reduce peoples’ willingness to write (or respond to) uncivil news-related comments. Finding new intervention strategies to reduce both incivility and the corresponding negative (unwanted) effects incivility has on journalism is a promising avenue for future research.

Limitations

While the review provides unique insights into current understandings of news-related user comments, it also has limitations. We focused only on peer-reviewed quantitative articles—meaning we do not consider qualitative papers nor conference or theory papers in these analyses. Focusing on quantitative papers allowed for a systematic coding of each article—however, of course, this leads to a limitation of not considering the full breadth of scholarly research on news-related user comments. Additionally, all potentially relevant papers may not have been included in our review due to divergent terminology used across papers (e.g., “posts” rather than “comments”)—a limitation we attempted to address (in part) by also collecting potentially relevant papers from other reviews (Ksiazek and Springer, 2018; Reimer et al., 2023). Finally, we view the current review as a first step in deeply understanding research on user comments. With this, we took a qualitative approach to understanding current findings. This means we do not systematically assess individual results but rather take a broad approach—examining overarching patterns and trends. We encourage scholars to further assess user comments through our open access list of included papers. These limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting results.

Conclusion

With the introduction of comment sections under news content, came normative ideas that such sections could be beneficial for public discourse and democracy (e.g., Engelke, 2020; see Habermas, 1962, 2022). However, current scholarly understandings of user comments suggest there may be many ill-effects (e.g., sowing distrust of journalism and snowballing incivility between commenters). We call on scholars to further consider (1) comparative and longitudinal approaches, (2) social media and video-based content, (3) platform design, content moderation, and artificial intelligence, and (4) search for measures to reduce incivility and negative impacts on digital journalism. Addressing these gaps will bring us one step closer to more fully understanding news-related user comments.

Author contributions

EK: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. PM: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization, Validation. MW: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. CD: Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. KG: Writing – review & editing. CS: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. We are grateful for support from the Schlieper Foundation to Christian von Sikorski (No. 4507-LD-28202).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Lisa Mai for her help with proofreading the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1447457/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^All papers included in this systematic review were available by the date of retrieval (i.e., April 4th 2022).

2. ^Fourteen of the 57 additional papers were included in this systematic review after being assessed by research assistants for whether they met inclusion criteria. Specific reasons for why each paper had not been found in our original Web of Science search query can be found in our Online Supplementary Materials (https://osf.io/swx76/?view_only=30aa778596aa4c469634fe84a3de63bb).

3. ^Research assistants were trained on papers that were included in the systematic review but that were not part of their own final set of assigned papers (i.e., not part of the approximately 130 papers they would code).

4. ^Research assistants also coded for whether the sample was a student sample or quota-based (representative), whether coding analyses (of content analyses) were automated or conducted manually, and whether the study considered dependent variables. However, reliability analyses indicated low reliability for these codes, therefore we do not consider these measures in our systematic review.

5. ^We conducted reliability analysis (Cohen’s Kappa; Cohen, 1960), on all codes that were quantitative in nature (i.e., ones where coders did not need to write in a free response box as these free response codes were uninterpretable with Cohen’s Kappa).

6. ^While this paper was published in 2023, it was available on the date of our paper retrieval (April 4th, 2022) because it was published online first. This occurred with several papers. We have provided the year of publication that is most up to date at the time of writing this review.

References

Ademmer, E., Leupold, A., and Stöhr, T. (2019). Much ado about nothing? the (non) politicisation of the European Union in social media debates on migration. Eur. Union Polit. 20, 305–327. doi: 10.1177/1465116518802058

Ahmed, S., and Matthes, J. (2017). Media representation of Muslims and Islam from 2000 to 2015: a meta-analysis. Int. Commun. Gaz. 79, 219–244. doi: 10.1177/1748048516656305

Aji, A. P., and Sapto, A. (2020). Incivility and disrespectfulness in online political discussion. Masyarakat Kebudayaan Politik 33, 278–285. doi: 10.20473/mkp.V33I32020.278-285

Aldous, K. K., An, J., and Jansen, B. J. (2023). What really matters? Characterising and predicting user engagement of news postings using multiple platforms, sentiments and topics. Behav. Inform. Technol. 42, 545–568. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2022.2030798

Anderson, A. A., Brossard, D., Scheufele, D. A., Xenos, M. A., and Ladwig, P. (2014). The “nasty effect:” online incivility and risk perceptions of emerging technologies. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 19, 373–387. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12009

Anspach, N. M., and Carlson, T. N. (2020). What to believe? Social media commentary and belief in misinformation. Polit. Behav. 42, 697–718. doi: 10.1007/s11109-018-9515-z

Arapakis, I., Lalmas, M., Cambazoglu, B. B., Marcos, M. C., and Jose, J. M. (2014). User engagement in online news: under the scope of sentiment, interest, affect, and gaze. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 65, 1988–2005. doi: 10.1002/asi.23096

Awobamise, A. O., and Jarrar, Y. (2021). The use of user-generated comments and their effects on the perception of news: An experimental study. Catalan J. Commun. Cult. Stud. 13, 83–100. doi: 10.1386/cjcs_00040_1

Beckert, J., and Ziegele, M. (2020). The effects of personality traits and situational factors on the deliberativeness and civility of user comments on news websites. Int. J. Commun. 14, 3924–3945.

Bergström, A., and Wadbring, I. (2015). Beneficial yet crappy: journalists and audiences on obstacles and opportunities in reader comments. Eur. J. Commun. 30, 137–151. doi: 10.1177/0267323114559378

Blassnig, S., Engesser, S., Ernst, N., and Esser, F. (2019). Hitting a nerve: populist news articles lead to more frequent and more populist reader comments. Polit. Commun. 36, 629–651. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2019.1637980

Blom, R., Carpenter, S., Bowe, B. J., and Lange, R. (2014). Frequent contributors within U.S. newspaper comment forums: An examination of their civility and information value. Am. Behav. Sci. 58, 1314–1328. doi: 10.1177/0002764214527094

Bogain, A. (2020). Understanding public constructions of counter-terrorism: An analysis of online comments during the state of emergency in France (2015-2017). Crit. Stud. Terror. 13, 591–615. doi: 10.1080/17539153.2020.1810976

Brundidge, J., Garrett, R. K., Rojas, H., and Gil De Zúñiga, H. (2014). Political participation and ideological news online: “differential gains” and “differential losses” in a presidential election cycle. Mass Commun. Soc. 17, 464–486. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2013.821492

Cabrera, L. Y., Bittlinger, M., Lou, H., Müller, S., and Illes, J. (2018). Reader comments to media reports on psychiatric neurosurgery: past history casts shadows on the future. Acta Neurochir. 160, 2501–2507. doi: 10.1007/s00701-018-3696-4

Cabrera, L. Y., Brandt, M., McKenzie, R., and Bluhm, R. (2019). Online comments about psychiatric neurosurgery and psychopharmacological interventions: public perceptions and concerns. Soc. Sci. Med. 220, 184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.11.021

Chen, G. M., Fadnis, D., and Whipple, K. (2020). Can we talk about race? Exploring online comments about race-related shootings. Howard J. Commun. 31, 35–49. doi: 10.1080/10646175.2019.1590256

Chen, G., and Lu, S. (2017). Online political discourse: exploring differences in effects of civil and uncivil disagreement in news website comments. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 61, 108–125. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2016.1273922

Chen, G. M., and Ng, Y. M. M. (2017). Nasty online comments anger you more than me, but nice ones make me as happy as you. Comput. Hum. Behav. 71, 181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.010

Chen, G. M., Riedl, M. J., Shermak, J. L., Brown, J., and Tenenboim, O. (2019). Breakdown of democratic norms? Understanding the 2016 US presidential election through online comments. Soc. Med. Soc. 5:843637. doi: 10.1177/2056305119843637

Chung, M., Munno, G. J., and Moritz, B. (2015). Triggering participation: exploring the effects of third-person and hostile media perceptions on online participation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 53, 452–461. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.037

Clementson, D. E. (2019). How web comments affect perceptions of political interviews and journalistic control. Polit. Psychol. 40, 815–836. doi: 10.1111/pops.12560

Coe, K., Kenski, K., and Rains, S. A. (2014). Online and uncivil? Patterns and determinants of incivility in newspaper website comments. J. Commun. 64, 658–679. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12104

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 20, 37–46. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000104

Colley, A., and Maltby, J. (2008). Impact of the internet on our lives: male and female personal perspectives. Comput. Hum. Behav. 24, 2005–2013. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2007.09.002

Connor, S. M., and Wesolowski, K. (2009). Posts to online news message boards and public discourse surrounding DUI enforcement. Traffic Inj. Prev. 10, 546–551. doi: 10.1080/15389580903261105

Danner, H., and Thøgersen, J. (2022). Does online chatter matter for consumer behaviour? A priming experiment on organic food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 46, 850–869. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12732

De Kraker, J., Kuijs, S., Cörvers, R., and Offermans, A. (2014). Internet public opinion on climate change: a world views analysis of online reader comments. Int. J. Climate Change Strat. Manag. 6, 19–33. doi: 10.1108/IJCCSM-09-2013-0109

Dohle, M. (2018). Recipients’ assessment of journalistic quality: do online user comments or the actual journalistic quality matter? Digit. J. 6, 563–582. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2017.1388748

Duncan, M., Pelled, A., Wise, D., Ghosh, S., Shan, Y., Zheng, M., et al. (2020). Staying silent and speaking out in online comment sections: the influence of spiral of silence and corrective action in reaction to news. Comput. Hum. Behav. 102, 192–205. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.026

Engelke, K. M. (2020). Enriching the conversation: audience perspectives on the deliberative nature and potential of user comments for news media. Digit. J. 8, 447–466. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2019.1680567

Esau, K., Friess, D., and Eilders, C. (2017). Design matters! An empirical analysis of online deliberation on different news platforms. Policy Internet 9, 321–342. doi: 10.1002/poi3.154

Evans, A. M., Stavrova, O., Rosenbusch, H., and Brandt, M. J. (2023). Expressions of doubt in online news discussions. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 41, 163–180. doi: 10.1177/08944393211034163

Freelon, D. (2015). Discourse architecture, ideology, and democratic norms in online political discussion. New Media Soc. 17, 772–791. doi: 10.1177/1461444813513259

Frischlich, L., Boberg, S., and Quandt, T. (2019). Comment sections as targets of dark participation? Journalists’ evaluation and moderation of deviant user comments. J. Stud. 20, 2014–2033. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2018.1556320

Galpin, C., and Trenz, H. J. (2019). Participatory populism: online discussion forums on mainstream news sites during the 2014 European parliament election. J. Pract. 13, 781–798. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2019.1577164

Gearhart, S., Moe, A., and Zhang, B. (2020). Hostile media bias on social media: testing the effect of user comments on perceptions of news bias and credibility. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2, 140–148. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.185

George, E., and Hovey, A. (2020). Deciphering the trigger warning debate: a qualitative analysis of online comments. Teach. High. Educ. 25, 825–841. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2019.1603142

Graf, J., Erba, J., and Harn, R.-W. (2017). The role of civility and anonymity on perceptions of online comments. Mass Commun. Soc. 20, 526–549. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2016.1274763

Habermas, J. (2022). Ein neuer Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit und die deliberative Politik. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Han, J., Lee, Y., Lee, J., and Cha, M. (2023). News comment sections and online echo chambers: the ideological alignment between partisan news stories and their user comments. Journalism 24, 1836–1856. doi: 10.1177/14648849211069241

Heinbach, D., Ziegele, M., and Quiring, O. (2018). Sleeper effect from below: long-term effects of source credibility and user comments on the persuasiveness of news articles. New Media Soc. 20, 4765–4786. doi: 10.1177/1461444818784472

Hermida, A., and Thurman, N. (2008). A clash of cultures: the integration of user-generated content within professional journalistic frameworks at British newspaper websites. J. Pract. 2, 343–356. doi: 10.1080/17512780802054538

Holton, A., Lee, N., and Coleman, R. (2014). Commenting on health: a framing analysis of user comments in response to health articles online. J. Health Commun. 19, 825–837. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.837554

Hsueh, M., Yogeeswaran, K., and Malinen, S. (2015). “Leave your comment below”: can biased online comments influence our own prejudicial attitudes and behaviors? Online comments on prejudice expression. Hum. Commun. Res. 41, 557–576. doi: 10.1111/hcre.12059

Hwang, H., Kim, Y., and Huh, C. U. (2014). Seeing is believing: effects of uncivil online debate on political polarization and expectations of deliberation. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 58, 621–633. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2014.966365

Jahng, M. R. (2018). From reading comments to seeking news: exposure to disagreements from online comments and the need for opinion-challenging news. J. Inform. Tech. Polit. 15, 142–154. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2018.1449702

Jahng, M. R., Stoycheff, E., and Rochadiat, A. (2021). They said it’s fake: effects of discounting cues in online comments on information quality judgments and information authentication. Mass Commun. Soc. 24, 527–552. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2020.1870143

Jakob, J., Dobbrick, T., Freudenthaler, R., Haffner, P., and Wessler, H. (2023). Is constructive engagement online a lost cause? Toxic outrage in online user comments across democratic political systems and discussion arenas. Commun. Res. 50, 508–531. doi: 10.1177/00936502211062773

Jaques, C., Islar, M., and Lord, G. (2019). Post-truth: hegemony on social media and implications for sustainability communication. Sustain. For. 11:2120. doi: 10.3390/su11072120

Kim, J. W. (2018). Online incivility in comment boards: partisanship matters - but what I think matters more. Comput. Hum. Behav. 85, 405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.015

Kim, J. W., and Chen, M. G. (2021). Exploring the influence of comment tone and content in response to misinformation in social media news. J. Pract. 15, 456–470. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2020.1739550

Kim, J. W., and Park, S. (2019). How perceptions of incivility and social endorsement in online comments (dis) encourage engagements. Behav. Inform. Technol. 38, 217–229. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2018.1523464

Kim, S., Rim, H., and Sung, K. H. (2021). Online engagement of active communicative behaviors and news consumption on internet portal sites. Journalism 22, 3048–3065. doi: 10.1177/1464884919894409

Ksiazek, T. B. (2015). Civil interactivity: how news organizations' commenting policies explain civility and hostility in user comments. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 59, 556–573. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2015.1093487

Ksiazek, T. B. (2018). Commenting on the news: explaining the degree and quality of user comments on news websites. J. Stud. 19, 650–673. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2016.1209977

Ksiazek, T. B., Peer, L., and Lessard, K. (2016). User engagement with online news: conceptualizing interactivity and exploring the relationship between online news videos and user comments. New Media Soc. 18, 502–520. doi: 10.1177/1461444814545073

Ksiazek, T. B., Peer, L., and Zivic, A. (2015). Discussing the news: civility and hostility in user comments. Digit. J. 3, 850–870. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2014.972079

Ksiazek, T. B., and Springer, N. (2018). “User comments in digital journalism: current research and future directions” in The Routledge handbook of developments in digital journalism studies. eds. S. Eldrige II and B. Franklin (London: Routledge), 475–486.

Kubin, E., Gray, K., and von Sikorski, C. (2023). Reducing political dehumanization by pairing facts with personal experiences. Polit. Psychol. 44, 1119–1140. doi: 10.1111/pops.12875

Kubin, E., and von Sikorski, C. (2021). The role of (social) media in political polarization: a systematic review. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 45, 188–206. doi: 10.1080/23808985.2021.1976070

Küchler, C., Stoll, A., Ziegele, M., and Naab, T. K. (2023). Gender-related differences in online comment sections: findings from a large-scale content analysis of commenting behavior. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 41, 728–747. doi: 10.1177/08944393211052042

Kümpel, A. S., and Unkel, J. (2021). (why) does comment presentation order matter for the effects of user comments? Assessing the role of the availability heuristic and the bandwagon heuristic. Commun. Res. Rep. 38, 217–228. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2021.1915269

Kunst, M. (2021). Assessments of user comments with “alternative views” as a function of media trust. J. Media Psychol. 33, 113–124. doi: 10.1027/1864-1105/a000287

Lee, E. J. (2012). That's not the way it is: how user-generated comments on the news affect perceived media bias. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 18, 32–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2012.01597.x

Lee, E.-J., and Jang, Y. J. (2010). What do others’ reactions to news on internet portal sites tell us? Effects of presentation format and readers’ need for cognition on reality perception. Commun. Res. 37, 825–846. doi: 10.1177/0093650210376189

Lee, E.-J., Jang, Y. J., and Chung, M. (2021). When and how user comments affect news readers’ personal opinion: perceived public opinion and perceived news position as mediators. Digit. J. 9, 42–63. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2020.1837638

Lee, N. Y., and McElroy, K. (2019). Online comments: the nature of comments on health journalism. Comput. Hum. Behav. 92, 282–287. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.006

Lee, S. Y., and Ryu, M. H. (2019). Exploring characteristics of online news comments and commenters with machine learning approaches. Telemat. Inform. 43:101249. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2019.101249

Lei, Y., Pereira, J. A., Quach, S., Bettinger, J. A., Kwong, J. C., Corace, K., et al. (2015). Examining perceptions about mandatory influenza vaccination of healthcare workers through online comments on news stories. PLoS One 10:e0129993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129993

Lien, A. N. (2022). A battle for truth: Islam-related counter public discourse on Scandinavian news media Facebook pages. New Media Soc. 26, 839–858. doi: 10.1177/14614448211068436

Lin, X., Kaufmann, R., Spence, P. R., and Lachlan, K. A. (2019). Agency cues in online comments: exploring their relationship with anonymity and frequency of helpful posts. South Commun. J. 84, 183–195. doi: 10.1080/1041794X.2019.1584828

Liu, J., and McLeod, D. M. (2019). Counter-framing effects of user comments. Int. J. Commun. 13, 2484–2503.

Lück, J., and Nardi, C. (2019). Incivility in user comments on online news articles: investigating the role of opinion dissonance for the effects of incivility on attitudes, emotions and the willingness to participate. SCM Stud. Commun. Media 8, 311–337. doi: 10.5771/2192-4007-2019-3-311

Maier, S. R. (2015). Compassion fatigue and the elusive quest for journalistic impact: a content and reader-metrics analysis assessing audience response. J. Mass Commun. Q. 92, 700–722. doi: 10.1177/1077699015599660

Marchionni, D. (2015). Online story commenting: An experimental test of conversational journalism and trust. J. Pract. 9, 230–249. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2014.938943

Masullo, G. M., Lu, S., and Fadnis, D. (2021). Does online incivility cancel out the spiral of silence? A moderated mediation model of willingness to speak out. New Media Soc. 23, 3391–3414. doi: 10.1177/1461444820954194

Masullo, G. M., Riedl, M. J., and Huang, Q. E. (2022). Engagement moderation: what journalists should say to improve online discussions. J. Pract. 16, 738–754. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2020.1808858

Masullo, G. M., Tenenboim, O., and Lu, S. (2023). “Toxic atmosphere effect”: uncivil online comments cue negative audience perceptions of news outlet credibility. Journalism 24, 101–119. doi: 10.1177/14648849211064001

Matthes, J., Knoll, J., and von Sikorski, C. (2018). The “spiral of silence” revisited: a meta-analysis on the relationship between perceptions of opinion support and political opinion expression. Commun. Res. 45, 3–33. doi: 10.1177/0093650217745429

Molina, R. G., and Jennings, F. J. (2018). The role of civility and metacommunication in Facebook discussions. Commun. Stud. 69, 42–66. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2017.1397038

Myers West, S. (2018). Censored, suspended, shadowbanned: user interpretations of content moderation on social media platforms. New Media Soc. 20, 4366–4383. doi: 10.1177/1461444818773059

Naab, T. K., Heinbach, D., Ziegele, M., and Grasberger, M.-T. (2020). Comments and credibility: how critical user comments decrease perceived news article credibility. J. Stud. 21, 783–801. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2020.1724181

Naab, T. K., and Küchler, C. (2023). “Content analysis in the research field of online user comments” in Standardisierte Inhaltsanalyse in der Kommunikationswissenschaft–standardized content analysis in communication research: Ein Handbuch-a handbook. eds. F. Oehmer-Pedrazzi, S. H. Kessler, E. Humprecht, K. Sommer, and L. Castro (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 441–450.

Naab, T. K., Naab, T., and Brandmeier, J. (2021). Uncivil user comments increase users’ intention to engage in corrective actions and their support for authoritative restrictive actions. J. Mass Commun. Q. 98, 566–588. doi: 10.1177/1077699019886586

Naab, T. K., and Sehl, A. (2017). Studies of user-generated content: a systematic review. Journalism 18, 1256–1273. doi: 10.1177/1464884916673557

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Eddy, K., Robertson, C. T., and Nielsen, R. K. (2023). Reuters institute: digital news report 2023. Available at: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-06/Digital_News_Report_2023.pdf

O’Connor, C., and Joffe, H. (2014). Gender on the brain: a case study of science communication in the new media environment. PLoS One 9:110830. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110830

Oschatz, C., and Marker, C. (2020). Long-term persuasive effects in narrative communication research: a meta-analysis. J. Commun. 70, 473–496. doi: 10.1093/joc/jqaa017

Otieno, A. W., Roark, J., Khan, M. L., Pant, S., Grijalva, M. J., and Titsworth, S. (2021). The kiss of death – unearthing conversations surrounding Chagas disease on YouTube. Cogent Soc. Sci. 7:1858561. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2020.1858561

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

Peacock, C., Scacco, J. M., and Jomini Stroud, N. (2019). The deliberative influence of comment section structure. Journalism 20, 752–771. doi: 10.1177/1464884917711791

Petit, J., Li, C., and Ali, K. (2021). Fewer people, more flames: how pre-existing beliefs and volume of negative comments impact online news readers’ verbal aggression. Telematics Inform. 56:101471. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2020.101471

Reimer, J., Häring, M., Loosen, W., Maalej, W., and Merten, L. (2023). Content analyses of user comments in journalism: a systematic literature review spanning communication studies and computer science. Digit. J. 11, 1328–1352. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2021.1882868

Riedl, M. J., Naab, T. K., Masullo, G. M., Jost, P., and Ziegele, M. (2021). Who is responsible for interventions against problematic comments? Comparing user attitudes in Germany and the United States. Policy Internet 13, 433–451. doi: 10.1002/poi3.257

Rodin, P., Ghersetti, M., and Odén, T. (2019). Disentangling rhetorical subarenas of public health crisis communication: a study of the 2014–2015 Ebola outbreak in the news media and social media in Sweden. J. Contingenc. Crisis Manag. 27, 237–246. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12254

Rosen, G., Kreiner, H., and Levi-Belz, Y. (2020). Public response to suicide news reports as reflected in computerized text analysis of online reader comments. Arch. Suicide Res. 24, 243–259. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2018.1563578

Rösner, L., Winter, S., and Krämer, N. C. (2016). Dangerous minds? Effects of uncivil online comments on aggressive cognitions, emotions, and behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 58, 461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.01.022

Saldana, M., and Rosenberg, A. (2020). I don't want you to be my president! Incivility and media bias during the presidential election in Chile. So. Media Soc. 6:891. doi: 10.1177/2056305120969891

San Pascual, M. R. S. (2020). The climate of incivility in Philippine daily Inquirer's social media environment. Plaridel 17, 177–207. doi: 10.52518/2020.17.1-06snpscl

Santana, A. D. (2011). Online readers' comments represent new opinion pipeline. Newsp. Res. J. 32, 66–81. doi: 10.1177/073953291103200306

Searles, K., Spencer, S., and Duru, A. (2020). Don’t read the comments: the effects of abusive comments on perceptions of women authors’ credibility. Inf. Commun. Soc. 23, 947–962. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2018.1534985

Sherrick, B., and Hoewe, J. (2018). The effect of explicit online comment moderation on three spiral of silence outcomes. New Media Soc. 20, 453–474. doi: 10.1177/1461444816662477

Shmargad, Y., Coe, K., Kenski, K., and Rains, S. A. (2022). Social norms and the dynamics of online incivility. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 40, 717–735. doi: 10.1177/0894439320985527

Spence, P. R., Lachlan, K. A., Lin, X., Westerman, D., Sellnow, T. L., Rice, R. G., et al. (2019). Let me squeeze a word in: exemplification effects, user comments and response to a news story. West. J. Commun. 83, 501–518. doi: 10.1080/10570314.2019.1591495

Springer, N., Engelmann, I., and Pfaffinger, C. (2015). User comments: motives and inhibitors to write and read. Inf. Commun. Soc. 18, 798–815. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2014.997268

Statista (2024). Leading countries based on Facebook audience size as of April 2024. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/268136/top-15-countries-based-on-number-of-facebook-users/

Stockinger, A., Schäfer, S., and Lecheler, S. (2023). Navigating the gray areas of content moderation: professional moderators’ perspectives on uncivil user comments and the role of (AI-based) technological tools. New Media Soc. 1. doi: 10.1177/14614448231190901

Stroud, N. J., Scacco, J. M., and Curry, A. L. (2016a). The presence and use of interactive features on news websites. Digit. J. 4, 339–358. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2015.1042982

Stroud, N. J., Scacco, J. M., Muddiman, A., and Curry, A. L. (2015). Changing deliberative norms on news organizations' Facebook sites. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 20, 188–203. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12104

Stroud, N. J., Van Duyn, E., and Peacock, C. (2016b). News commenters and news comment readers engaging news project. Available at: https://mediaengagement.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/ENP-News-Commenters-and-Comment-Readers1.pdf

Stylianou, S., and Sofokleous, R. (2019). An online experiment on the influence of online user comments on attitudes toward a minority group. Commun. Soc. 32, 125–142. doi: 10.15581/003.32.4.125-142

Su, L. Y.-F., Scheufele, D. A., Brossard, D., and Xenos, M. A. (2021). Political and personality predispositions and topical contexts matter: effects of uncivil comments on science news engagement intentions. New Media Soc. 23, 894–919. doi: 10.1177/1461444820904365

Su, L. Y. F., Xenos, M. A., Rose, K. M., Wirz, C., Scheufele, D. A., and Brossard, D. (2018). Uncivil and personal? Comparing patterns of incivility in comments on the Facebook pages of news outlets. New Media Soc. 20, 3678–3699. doi: 10.1177/1461444818757205

Suh, K.-S., Lee, S., Suh, E.-K., Lee, H., and Lee, J. (2018). Online comment moderation policies for deliberative discussion–seed comments and identifiability. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 19, 182–208. doi: 10.17705/1jais.00489

Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. CyberPsychol. Behav. 7, 321–326. doi: 10.1089/1094931041291295

Szabo, G., Kmetty, Z., and Molnar, E. K. (2021). Politics and incivility in the online comments: what is beyond the norm-violation approach? Int. J. Commun. 15, 1659–1684.

Taylor, C. A., Al-Hiyari, R., Lee, S. J., Priebe, A., Guerrero, L. W., and Bales, A. (2016). Beliefs and ideologies linked with approval of corporal punishment: a content analysis of online comments. Health Educ. Res. 31, 563–575. doi: 10.1093/her/cyw029

Tenenboim, O., and Cohen, A. A. (2015). What prompts users to click and comment: a longitudinal study of online news. Journalism 16, 198–217. doi: 10.1177/1464884913513996

Toepfl, F., and Piwoni, E. (2015). Public spheres in interaction: Comment sections of news websites as counterpublic spaces. J. Commun, 65, 465–488. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12156

Toepfl, F., and Litvinenko, A. (2021). Critically commenting publics as authoritarian input institutions: how citizens comment beneath their news in Azerbaijan, Russia, and Turkmenistan. Journal. Stud. 22, 475–495. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2021.1882877

Tsfati, Y., Boomgaarden, H. G., Strömbäck, J., Vliegenhart, R., Damstra, A., and Lindgren, E. (2020). Causes and consequences of mainstream media dissemination of fake news: literature review and synthesis. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 44, 157–173. doi: 10.1080/23808985.2020.1759443

Ürper, D., and Çevikel, T. (2016). Editorial policies, journalistic output and reader comments: a comparison of mainstream online newspapers in Turkey. J. Stud. 17, 159–176. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2014.969491

Van den Bulck, H., and Claessens, N. (2014). Of local and global fame: a comparative analysis of news items and audience reactions on celebrity news websites people, heat, and HLN. Journalism 15, 218–236. doi: 10.1177/1464884913488725

Vehof, H., Heerdink, E., Sanders, J., and Das, E. (2019). Associations between characteristics of web-based diabetes news and readers’ sentiments: observational study in the Netherlands. J. Med. Internet Res. 21:e14554. doi: 10.2196/14554

von Sikorski, C. (2016). The effects of reader comments on the perception of personalized scandals: exploring the roles of comment valence and commenters’ social status. Int. J. Commun. 10, 4480–4501.

von Sikorski, C. (2018). The aftermath of political scandals: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Commun. 12, 3109–3133.

von Sikorski, C., and Hänelt, M. (2016). Scandal 2.0: how valanced reader comments affect recipients’ perception of scandalized individuals and the journalistic quality of online news. J. Mass Commun. Q. 93, 551–571. doi: 10.1177/1077699016628822

Waddell, T. F. (2018). What does the crowd think? How online comments and popularity metrics affect news credibility and issue importance. New Media Soc. 20, 3068–3083. doi: 10.1177/1461444817742905

Waddell, T. F. (2020). The authentic (and angry) audience: how comment authenticity and sentiment impact news evaluation. Digit. Journal. 8, 249–266. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2018.1490656

Walter, S., Brueggermann, M., and Engesser, S. (2018). Echo chambers of denial: explaining user comments on climate change. Environ. Commun. 12, 204–217. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2017.1394893