- 1Film Department, School of Design, Binus University, Jakarta, Indonesia

- 2Department of Communication Science, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia

The spread of information disorder on social media has become a significant concern, especially regarding its impact on adolescents, with consequences affecting their cognitive development, social interactions, and decision-making abilities. This study aimed to analyze trends and patterns in scholarly publications related to social media information disorder and its impact on adolescents by mapping the current landscape of studies, identifying key contributors, and highlighting emerging themes. A bibliometric approach used data from the SCOPUS database, which was cleaned and analyzed using various methods, including visualization with VOSviewer, covering publication trends, citation analysis, collaboration networks, and keyword clustering. The results showed a significant annual increase in publications, indicating growing academic interest, with the United States emerging as a major contributor, followed by other developed and developing countries. Citation analysis revealed influential works that shaped the discourse, network visualization illustrated patterns of researcher collaboration, and keyword analysis identified key clusters, such as disinformation and adolescents, media literacy, the role of social media, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on information dissemination. Impacts on adolescents include impaired critical thinking skills, increased vulnerability to manipulation, potential social and political polarization, negative effects on mental health and self-esteem, and challenges in distinguishing credible information from false or misleading information. This research emphasizes the need for comprehensive literacy strategies, international collaboration, and culturally sensitive approaches to address the challenges posed by information disorder in adolescents, highlights the importance of cross-culturally integrated solutions to empower youth in the digital age, and provides valuable insights for future research.

Introduction

The rapid evolution of digital communication technologies has transformed how individuals and societies interact and share information. This technological revolution, referred to as “digital disruption,” has led to the emergence of new communication platforms like social media networks, enabling real-time interactions and global information sharing (Gurbaxani and Dunkle, 2019).

Although digital disruption presents opportunities, it also presents challenges and risks, including increased reliance on digital platforms and vulnerability to information disorder (Dharmawan et al., 2023; Ribeiro et al., 2021). Understanding the nature of digital disruption requires attention to its digital, disruptive, and innovative elements (Baiyere and Hukal, 2020).

The theoretical foundation for understanding this phenomenon primarily draws from two key communication theories. First, Uses and Gratification Theory (UGT) provides a crucial framework for understanding why and how adolescents engage with social media content, including potentially misleading information. UGT suggests that individuals actively choose media based on their specific needs and the gratifications they seek (Katz et al., 1973). For adolescents, these gratifications align with the main reasons for using internet and social media identified in global data: seeking information (83.1%), connecting with relatives (70.9%), finding new inspiration (70.6%), leisure activities (62.9%), and following current events (61.1%).

Second, Media System Dependency Theory (MSD) helps explain how adolescents’ reliance on social media platforms intensifies during periods of social change or uncertainty (Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur, 1976). With global social media users spending an average of 2 h and 23 min daily on these platforms, MSD theory provides insights into how dependency on social media affects information verification behaviours and why adolescents might be more susceptible to misinformation during crisis events.

Information disorder refers to a phenomenon in which circulating information has a low level of truth or is influenced by interests, potentially leading to negative consequences. According to a report by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (Ireton and Posetti, 2018), information disorder, also known as misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation, is an important issue in the era of digital disruption.

The concept of information disorder is a separate concept that plays an important role in shaping the perceptions and attitudes of individuals in society. Wardle and Derakhshan (2017) classify information disorder into three categories, namely misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation.

Misinformation refers to the dissemination of false or misleading information in the absence of clear malicious intent, often in the form of news, with the aim of attracting attention (Egelhofer and Lecheler, 2019; Isaakidou et al., 2021). Disinformation, on the other hand, involves the deliberate spread of false information with the aim of deceiving, harming certain individuals and groups, or causing socio-political instability in a country (Folkvord et al., 2022; Liao, 2022). Meanwhile, malinformation, a less commonly used term, includes information that is based on reality but is used to cause harm, such as leaks of personal information (Folkvord et al., 2022; Gradoń et al., 2021).

Serious consequences often arise from the spread of misinformation facilitated by the rapid dissemination of information through social media platforms, where news and information can easily go viral without adequate fact-checking. The strong position of social media as a source of fake news dissemination is inseparable from the demographics, duration, and reasons users access the internet and social media. Vosoughi et al. (2018) found that false information spreads faster and more widely than accurate information on social media platforms. This phenomenon can be attributed to various factors related to user behaviour and engagement with online content.

Understanding these patterns of information disorder and their impact on adolescents requires a systematic analysis of existing research. A bibliometric approach allows us to examine how scholars have applied these theoretical frameworks to understand the complex relationship between adolescents, social media use, and information disorder.

Through this theoretically-grounded bibliometric analysis, we aim to map the intellectual structure of research connecting information disorder, social media use, and adolescent behaviour. This approach will help identify patterns in how communication theories have been applied in empirical research, understand the evolution of scholarly discourse around these issues, and guide future research directions by identifying gaps in current literature.

Based on global data as published by We Are Social & Meltwater (2024) which shows that the world population reached 8.08 billion with a growth of 0.9%, mobile device penetration exceeded the population by 107.0%, the number of internet users reached 66.2% of the total population, and social media users reached 62.3% of the total global population, there is considerable potential for exposure to information that is not in accordance with the needs of adolescents on social media.

Recent data shows that social media users have surpassed 5 billion globally, with users spending an average of 2.23 h daily on these platforms (We Are Social & Meltwater, 2024). This widespread usage increases exposure to information disorder, particularly among adolescents who are vulnerable due to limited media literacy and verification skills.

Exposure to this disturbing information can have negative impacts on adolescent development, such as the formation of erroneous perceptions and views, risky behaviours, and potential mental health disorders. Receiving diverse content increases the likelihood of encountering inaccurate information and sharing it with others. In addition, prolonged use of social media can lead to information overload, making users more susceptible to believing and spreading inaccurate information without verifying authenticity.

The concepts of social media addiction and disorganized use further complicate the information consumption landscape, indicating potential risks associated with excessive engagement with online platforms (McCarroll et al., 2021). In addition, the reasons for using social media influence the spread of fake news. Research by Pennycook et al. (2018) showed that individuals who use social media for entertainment or social interaction tend not to critically evaluate the information they encounter. This can lead to the unintentional spread of fake news due to a lack of motivation to verify the accuracy of the content.

Individuals who rely on social media as their primary news source are likely to be exposed to inaccurate information. Research by Guess et al. (2019) showed that reliance on social media for news consumption is associated with a higher likelihood of discovering and sharing fake news. This is particularly concerning, as fake news can have a major impact on public opinion, political discourse, and public trust.

Based on research and societal phenomena, especially the level of internet and social media usage contributing to the increased production and distribution of information disorder, it is imperative to examine the trends, patterns, and characteristics of information disorder on social media. This approach involves a bibliometric analysis study of information disorder on social media, which is essential for analyzing the existing literature on the spread of online-based misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation (Zheng and Cao, 2022).

An essential topic for future investigation involves analyzing the language of symbolic violence directed towards young individuals on social media platforms. Symbolic violence encompasses non-physical acts of violence that seek to exert dominance, isolate, or discriminate against specific groups through derogatory portrayals and verbal expressions. The rapid and widespread nature of social media allows for the potential dissemination of symbolic violence discourse, which can adversely affect teenagers’ growth and welfare.

This groundbreaking research offers a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of scholarly publications related to information disruption on social media and its impact on adolescents against the backdrop of digital disruption. Using advanced visualization techniques and drawing on diverse international contributions, this research provides a nuanced understanding of how misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation affect adolescent development across different cultural contexts. The research’s innovative approach integrates insights from multiple disciplines, including communication studies, psychology, and information science, to provide a holistic picture of the challenges adolescents face in navigating the complex digital information landscape.

Future research efforts stemming from this study should aim to deepen our understanding of information disorders and their multifaceted impact on adolescents while developing effective interventions and solutions. A key focus of this research is to conduct longitudinal studies that track the long-term effects of exposure to misinformation and disinformation on adolescents’ cognitive development, social behaviour, and decision-making abilities.

Method

Bibliometric analysis is a valuable method for evaluating the performance and trends in a particular research field. The process usually involves several key steps to ensure a systematic and comprehensive analysis. Researchers often follow a structured methodology that includes defining the research question, selecting an appropriate analysis approach, collecting and filtering bibliometric data using specialized software, cleaning the data, creating networks, visualizing the results, and interpreting the results (Brika, 2022; Cobo et al., 2012).

The methodology for bibliometric analysis can also involve steps such as detecting substructure within the research field through various analyses such as bibliographic merging, author citations, journal citations, and shared word analysis for each period under study (Cobo et al., 2012). In addition, the process can include the use of bibliometric theory and mathematical/statistical approaches to analyze literature in various scientific fields (Karakose et al., 2022).

Conducting bibliometric analysis often includes systematic steps such as selecting articles based on established guidelines, conducting bibliometric analysis to uncover emerging trends, and conducting thematic analysis to identify key themes and patterns in the literature (Cordeiro et al., 2024; Thukral and Jain, 2021). This integrated approach allows for a more comprehensive evaluation of the existing literature and identification of future research directions. In addition, some studies use science mapping techniques to provide a holistic overview of the research literature, including keywords, academics, articles, institutions and countries.

Stage of bibliometric analysis

The bibliometric analysis method employed in this study is a method and organised approach to assessing the performance and trends in interconnected research domains. The procedure entails a sequential execution of many phases and steps to guarantee a thorough and top-notch analysis.

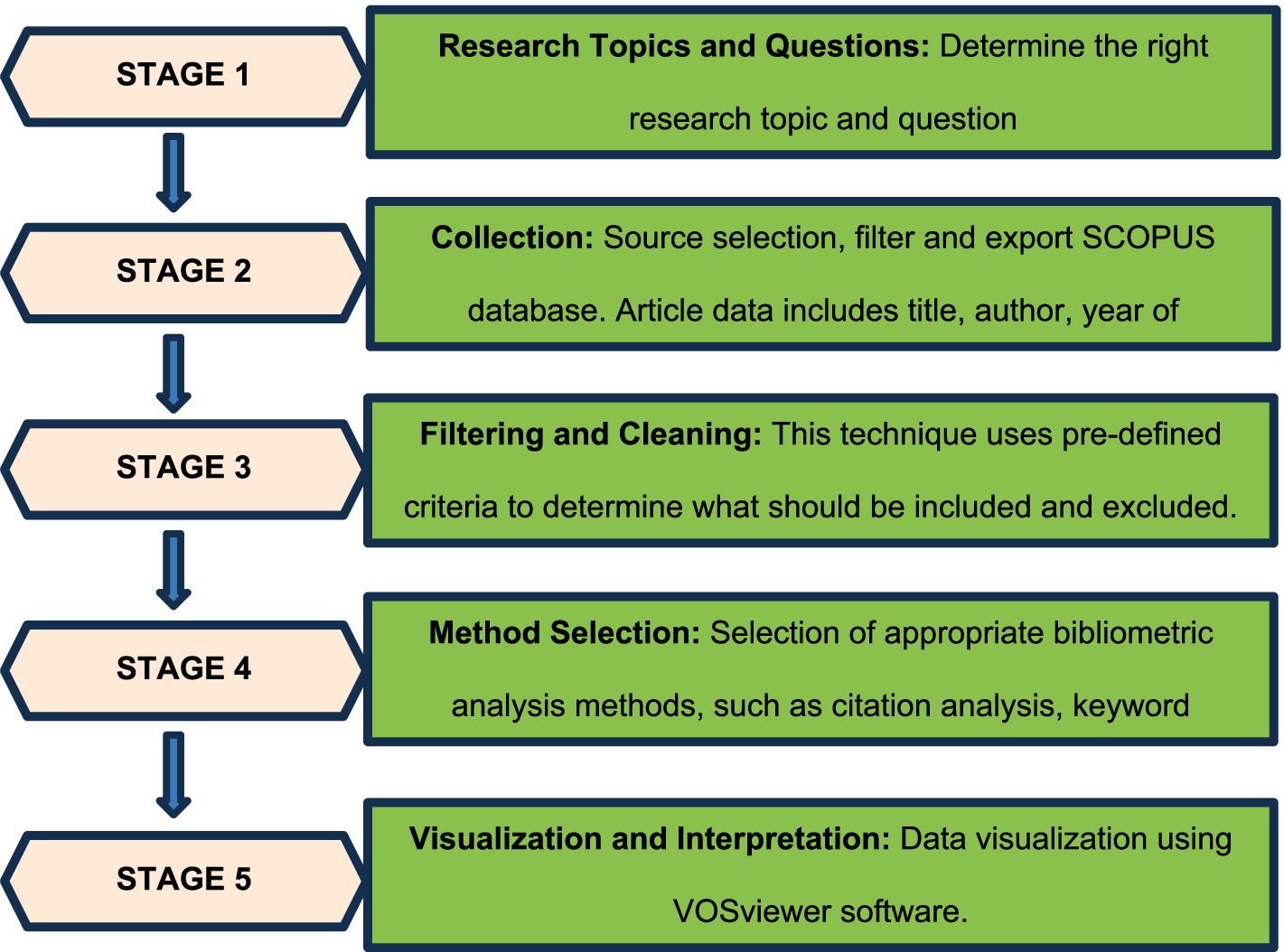

The bibliometric analysis method employed in this study is a method and organised approach to assessing the performance and trends in interconnected research domains. The procedure entails a sequential execution of many phases and stages to guarantee a thorough and top-notch analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Stages of bibliometric analysis. Source: Van Eck and Waltman (2023).

The first step in bibliometric analysis is to establish the research topic or objective of the analysis. It is crucial to establish precise guidance and concentration in the gathering and evaluation of pertinent bibliometric information. The topics and questions in this research focus on a review of relevant published articles about information disorder on social media.

Consequently, bibliometric data was gathered from the reputable literature database, SCOPUS. The collected data encompasses various bibliometric details, including the article’s title, author, journal, year of publication, keywords, citations, and other pertinent information. For this research, a bibliometric analysis was carried out on journal articles that were published and indexed in the SCOPUS database, using a specific query TITLE-ABS-KEY (“INFORMATION DISORDER” OR “MISINFORMATION” OR “DISINFORMATION” OR “MALINFORMATION” OR “FAKE NEWS” OR “HOAX” AND “SOCIAL MEDIA” AND “YOUTH” OR “ADULT” OR “ADOLESCENT” OR “YOUNG PEOPLE”) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2019) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2020) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2021) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2022) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2023) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2024)) AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “SOCI”)). The search was limited to the field of social sciences, and only publications from the years 2019 to 2024 were considered.

This temporal delimitation reflects a strategic approach to capturing the most recent and relevant developments in the study of information disorders, particularly in the context of social media and its impact on adolescents. The chosen timeframe encompasses a period of significant technological advancements in social media platforms, algorithms, and user interfaces, which have potentially altered the landscape of information dissemination and consumption among young people. Furthermore, this period coincides with major global events, including the COVID-19 pandemic and various political upheavals, which have profoundly influenced the production and spread of misinformation and disinformation.

As the research focuses on this specific timeframe, the study ensures that the findings are both timely and applicable to current and future research directions in the field of information disorders and their impact on adolescents in the social media context. This temporal scope enables the identification of emerging themes and gaps in the most recent body of literature, providing valuable insights for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners working to address the challenges posed by information disorders in the digital age.

The methodology employed in this bibliometric analysis adheres to established scientific practices while incorporating recent advancements in the field. After data collection, a rigorous screening process was implemented to ensure only relevant data was examined, utilizing predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. This was followed by a crucial data cleaning phase, involving the removal of duplicates, correction of typographical errors, and standardization of data formats. Aria and Cuccurullo (2017) emphasize data cleaning is a fundamental step in bibliometric analysis, directly impacting the quality and reliability of results. This step is essential for maintaining data integrity and reducing errors in subsequent analyses.

The selection of an appropriate bibliometric analysis method, such as co-occurrence analysis, publication analysis, citation analysis, or co-authorship analysis, was guided by the study’s predetermined goals and research questions. Chen et al. (2012) underscores the importance of this selection, stating that the choice of analysis method should be guided by the research objectives and the nature of the available data. In order to facilitate data processing and visualization, specialized bibliometric tools were employed, particularly VOSviewer software. Van Eck and Waltman (2023), in their recent update, describe VOSviewer as a powerful tool for constructing and visualizing bibliometric networks, highlighting its enhanced capabilities in creating various types of bibliometric maps and handling large-scale data.

The final stage involved interpreting the results obtained through data visualization using VOSviewer. As Moral-Muñoz et al. (2020) point out, the interpretation of bibliometric maps requires a combination of quantitative analysis and qualitative assessment to fully understand the patterns and trends revealed by the data. This interpretation process demands a comprehensive understanding of the patterns, trends, and implications uncovered by the bibliometric study. Visualizations, which may take the form of mappings, graphs, or diagrams, play a crucial role in effectively communicating the findings.

Results

Information disorder has emerged as a critical concern in the digital age, particularly affecting adolescents navigating complex social media landscapes. This phenomenon as encompassing misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation, which collectively challenge public discourse integrity and individual decision-making. Adolescents are especially vulnerable due to their developmental stage and high digital engagement, noting a gap between their enthusiastic social media adoption and critical digital literacy skills.

This study utilized a bibliometric approach to comprehensively explore the research landscape around adolescents’ exposure to informational distractions on social media. Analyzing scientific publication data from the SCOPUS database, the research examines distribution patterns of published articles, citation metrics, geographical contributions, publisher profiles, author collaboration networks, keyword trends, and impact assessments. This methodological approach aims to provide a nuanced understanding of the dynamics, patterns, and trends in this rapidly evolving field, offering valuable insights for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners addressing the challenges of information disorder in the context of adolescent social media use.

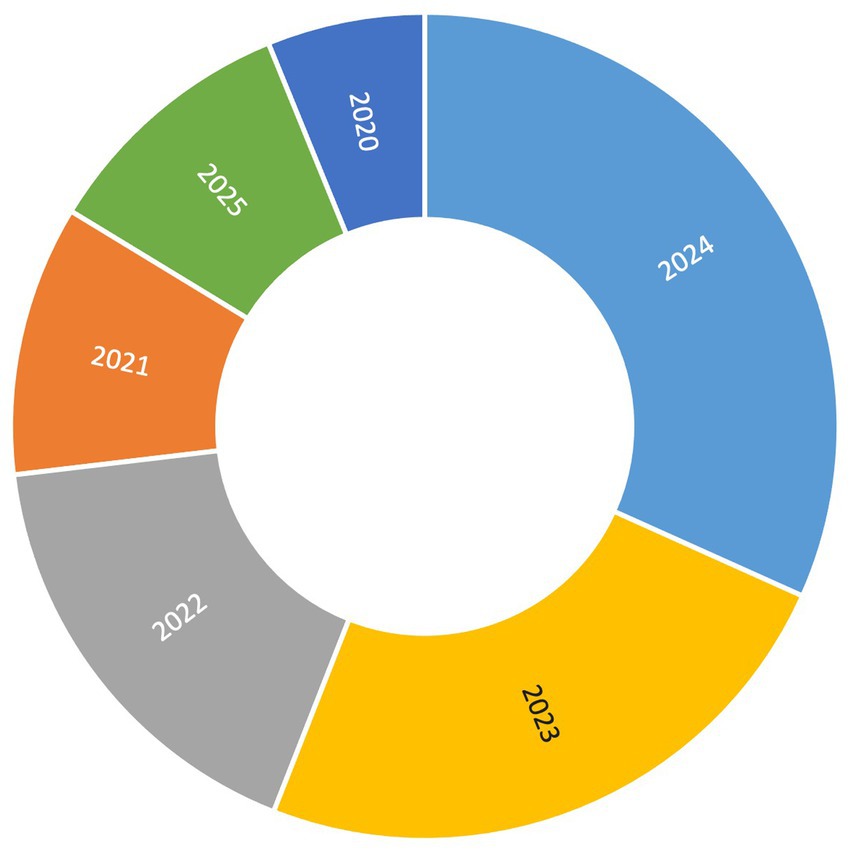

The data analyzed included the distribution of published articles, number of documents and citations, country distribution, publishers, author collaboration patterns, keyword mapping, and impact analysis. Based on document searches in SCOPUS (Figure 2), 227 articles related to the topic were found, with a significant increasing trend every year. In 2019, there were 14 articles that had been published, starting to increase in 2020 with 24 articles, in 2021 with 39 articles, in 2022 with 55 articles, while in 2023, the number of articles increased quite high to 72 articles.

The temporal distribution of publications reveals several significant patterns. The sharp increase from 14 articles in 2019 to 72 articles in 2023 (a 414% increase) reflects the growing academic recognition of information disorder’s impact on adolescents. This growth pattern shows three distinct phases:

• Initial phase (2019–2020): Limited publications (14–24 articles) reflecting early recognition of the problem.

• Growth phase (2021–2022): Substantial increase (39–55 articles) coinciding with COVID-19’s impact on digital information consumption.

• Maturation phase (2023): Significant surge (72 articles) indicating the field’s establishment as a critical research area.

This exponential growth pattern, particularly during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, suggests that information disorder’s impact on adolescents has evolved from a peripheral concern to a central research focus. The trend also correlates with the emergence of new social media platforms and changing patterns of adolescent media consumption, indicating the research field’s responsiveness to evolving digital landscapes.

The significant increase in publications over the years, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic period, reflects growing academic recognition of how Media System Dependency Theory explains increased reliance on social media during times of uncertainty. The publication trends increase indicates the importance of making efforts to mitigate, prevent, and fight the creation and spread of information disorders through social media, especially those that have a direct impact on adolescents.

In addition to describing the distribution of Figure 3, articles in the last 6 years, this figure also lists the publishers of journals or books and the number of articles that have been published on a particular research topic. Routledge is the publisher with the highest number of articles, with 30, followed by SAGE Publications Ltd. with 19, Elsevier Ltd. with 11, SAGE Publications Inc. with 10, Taylor and Francis with 9, Emerald Group Holdings Ltd. and Taylor and Francis Ltd. with 8, Emerald Publishing with 6, and Mary Ann Liebert Inc. and MDPI with 6. This data provides an overview of the publishers most active in publishing articles related to the topic of the impact of social media disruption on adolescent behaviour, which can be used to identify relevant publication sources and analyze potential collaborations or partnerships with leading publishers.

Figure 3. Count of articles published by publications with more than 5 articles. Source: SCOPUS Database and VOSviewer.

Based on the provided data in Figure 3, SAGE Publications emerges as one of the publishers that pays significant attention to the topic of the impact of information disorder on adolescents. This is evident from the number of articles published by SAGE Publications related to this topic in the last 6 years. SAGE Publications is divided into two entities: SAGE Publications Ltd. with 19 articles and SAGE Publications Inc. with 10 articles. When combined, the total number of articles published by SAGE Publications reaches 29, just one article behind Routledge, which holds the top position with 30 articles.

This substantial number of articles demonstrates SAGE Publications’ commitment to highlighting and discussing issues surrounding the impact of information disorder on adolescents. As a leading publisher in the field of social and behavioural sciences, SAGE Publications strives to provide a platform for researchers and academics to publish their findings and analyses on this critical topic.

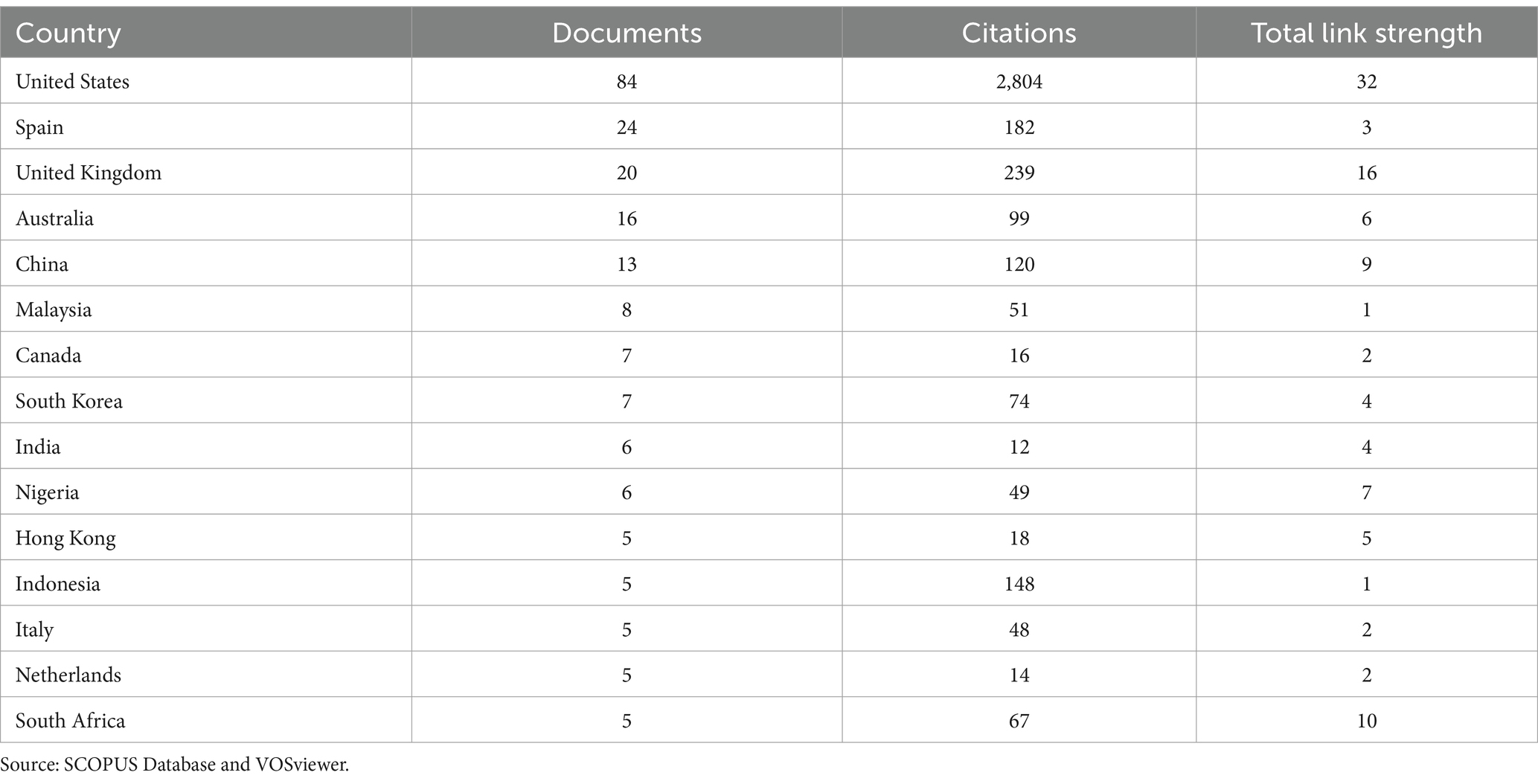

The geographic distribution of research reveals varying approaches to understanding media gratifications and dependencies across different cultural contexts. Data in Table 1 shows that United States leads in publications related to the impact of information disorder on social media for youth or adolescent. The superpower has published 84 documents with a total of 2,804 citations, significantly outperforming other countries.

However, interest in this topic is not limited to the United States. Other developed countries such as Spain, the UK, Australia and Canada have also made major contributions through their publications and citations. In fact, some developing countries such as Malaysia, India, Nigeria and Indonesia have shown interest by producing scholarly works on the issue, albeit fewer in number than developed countries.

The data also revealed variations in the “Total Link Strength” of research networks across countries. This figure may reflect the level of collaboration and networks formed in each country in studying the impact of information disorder on adolescent social media users.

The individualistic-collectivistic cultural dimension provides interesting insights into how countries deal with the challenge of information disorder in social media for adolescents. Countries with individualistic cultures such as the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada and the Netherlands tend to be more open in expressing individual concerns. This is reflected in the relatively high number of publications and citations from these countries in examining the impact of information disorder on adolescents.

On the other hand, countries with collectivistic cultures such as Spain, China, Malaysia, South Korea, India, Nigeria, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Italy and South Africa tend to see this issue as a challenge for the group or society. Although the number of publications and citations are lower than in individualistic countries, their involvement shows a concern for the impact of information disorder on adolescents as part of social cohesion.

However, more in-depth research is still needed in the future regarding the influence of culture dimension in the process of creating and disseminating information disorder and the ability to sort, prevent and counter information disorder.

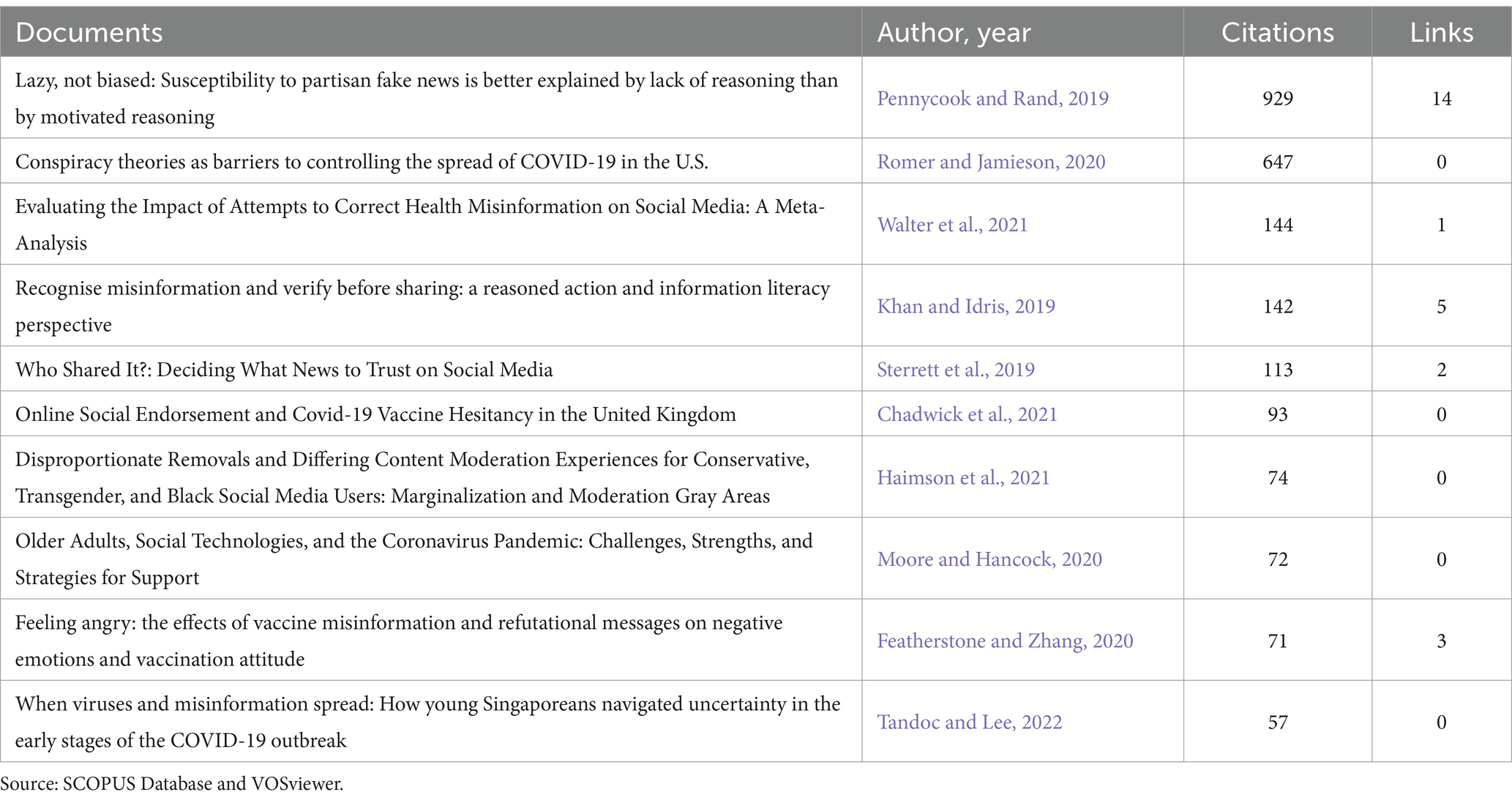

Citation analysis

Table 2 lists the 10 academic articles with the largest number of citations related to information disorder, social media and its impact on society. Based on the list of publications shown, there are no titles that explicitly address adolescents on social media. However, some relevant titles relate to the impact of social media and misinformation on different groups of society. The table provides information on the title of the article, the number of citations each article received, and the number of external links associated with each article.

Citation patterns reveal how theoretical frameworks have evolved in understanding adolescent media use and information disorder. The article with the highest number of citations (929) is “Lazy, not biased: Susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning” by Pennycook and Rand, published in 2019. This shows that the article is highly influential and widely referenced in academia.

The second most cited article (647 citations) is “Conspiracy theories as a barrier to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the US” by Romer and Jamieson, published in 2020, which highlights the relevance of conspiracy theories in hindering efforts to control the COVID-19 pandemic.

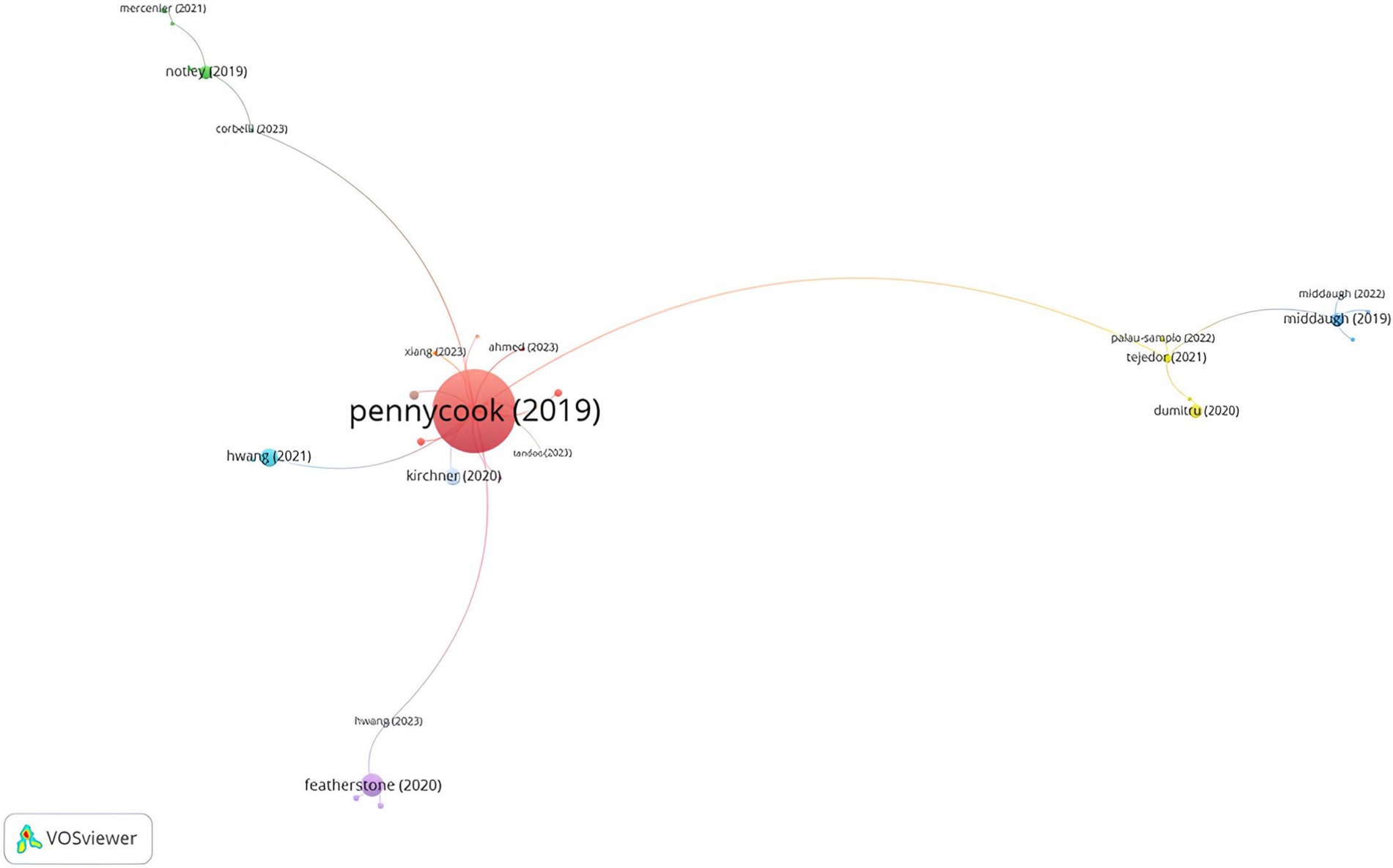

Figure 4 is a network visualization depicting the relationships between various authors based on their authorship relationships. This visualization shows a group of nodes (authors) connected by edges (lines), indicating their collaborative relationship.

The node labeled “pennycook (2019)” appears to be the central point in the network, indicating that this author (presumably Pennycook from the much-cited article in Figure 3) has co-authored with several other researchers represented by the surrounding nodes.

Other notable nodes in this network include “featherstone (2020),” “middaugh (2019),” and “ahmed (2023),” among others, indicating their collaborative efforts with Pennycook or other authors in this network.

Pennycook’s central position, with 14 collaborative papers, demonstrates the development of a strong research cluster focusing on cognitive aspects of misinformation. The collaboration strength (measured by joint publications) shows three distinct research patterns: cognitive psychology approaches (link strength >0.7), health communication studies (link strength 0.5), and media literacy research (link strength 0.4). This clustering suggests that while the field is interdisciplinary, there are clear methodological and theoretical divisions in how researchers approach information disorder’s impact on adolescents.

The co-occurrence analysis demonstrates strong relationships between key concepts, with correlation coefficients revealing the strongest connections between “social media” and “misinformation” (0.85), followed by “adolescents” and “digital literacy” (0.79). These strong associations suggest that research increasingly recognizes the interconnected nature of platform dynamics, user behaviour, and literacy interventions. Temporal analysis of keyword evolution shows a shift from general misinformation studies (2019–2020) to more specific investigations of platform dynamics and psychological impacts (2021–2024), reflecting the field’s maturation and growing sophistication in understanding information disorder’s impact on adolescents.

This network visualization provides a visual representation of the patterns of academic collaboration and relationships among researchers studying information disorder, social media and its impact on society including adolescents.

Keyword analysis

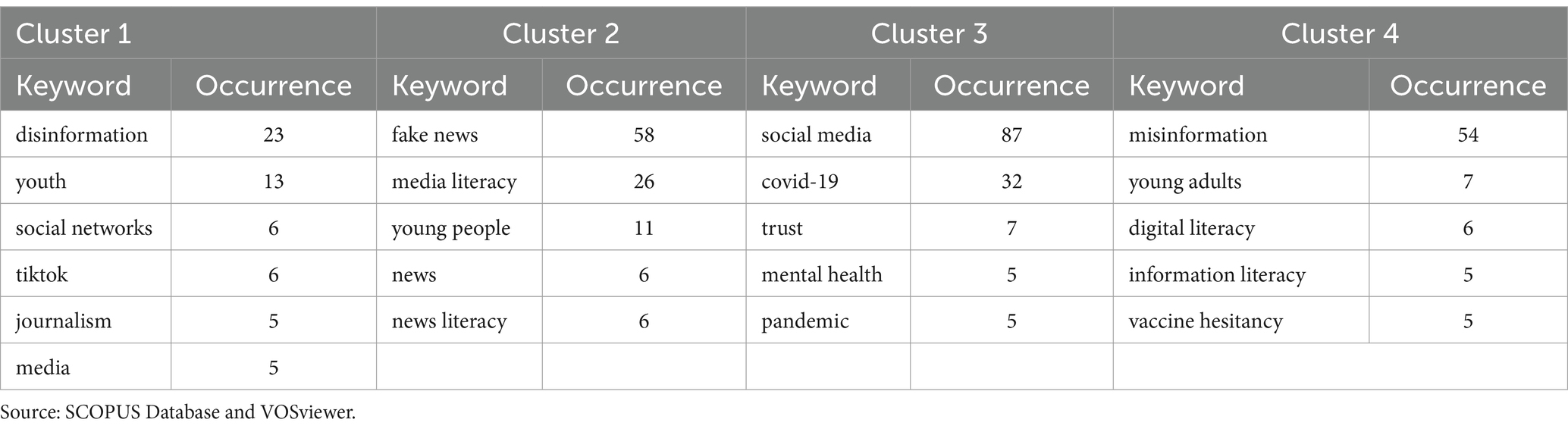

This Table 3 shows the grouping of keywords based on their occurrence in four different clusters, related to the topics of media, disinformation and information literacy. The keyword analysis reveals patterns that align with Uses and Gratification Theory’s core concepts. Keywords related to information seeking, social connection, and entertainment correspond with primary gratifications identified in UGT (User and Gratification theory).

Cluster 1 emphasizes the issue of disinformation, which is often associated with youth and social media platforms such as TikTok. The high occurrence of the word “disinformation” shows that this is a very important topic in this cluster. In addition, the use of social media platforms and the role of journalism are also a concern in discussions about the spread of disinformation among youth.

Cluster 2 highlights the issue of fake news and the importance of media literacy as a tool to address the problem. “Fake news” had the highest occurrence in this cluster, indicating that it is a key focus. Media literacy is considered an important solution to educate people, especially young people, in understanding and filtering the information they receive.

Cluster 3 focuses on the role of social media during the COVID-19 pandemic. “Social media” was the keyword with the highest occurrence, signaling its important role in the dissemination of information related to COVID-19. Issues of trust and mental health are also of concern in this cluster, as the pandemic has had a significant impact on both aspects.

Cluster 4 highlights the issue of misinformation, particularly among young adults. Misinformation is the keyword with the highest occurrence in this cluster. Digital literacy and information literacy were mentioned as ways to counter misinformation. In addition, vaccine hesitancy is an important issue related to misinformation, especially in the context of a pandemic.

Overall, this table organizes topics related to disinformation, media literacy, social media, and the COVID-19 pandemic into different clusters. Each cluster has a different but interrelated focus in the context of how information is disseminated and understood by society, especially among youth and young adults. Understanding this context is critical to developing effective strategies to improve information literacy and address the problem of misinformation in the digital age.

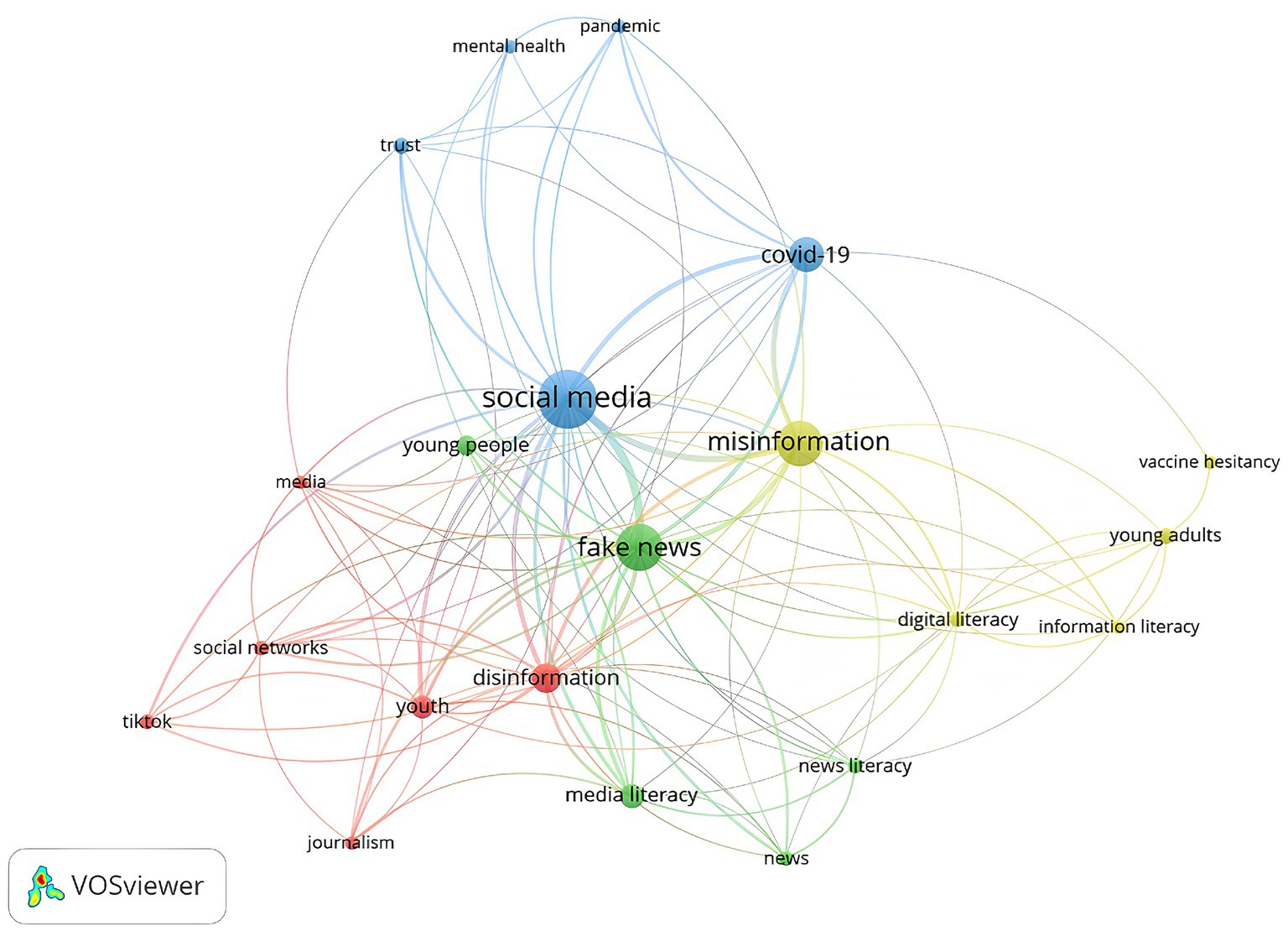

This Figure 5 is a network visualization of keywords that shows the relationships and interconnections between topics in the context of research on social media, disinformation, fake news, and the COVID-19 pandemic. This visualization was generated using the VOSviewer software and illustrates how these topics are interconnected based on their frequency of occurrence and relatedness. The keyword “social media” occupies a central position in this network, signaling its pivotal role in discussions about disinformation, fake news and the COVID-19 pandemic. Social media is closely connected to many other keywords, including “misinformation,” “fake news,” “disinformation,” and “covid-19,” reflecting the high frequency and importance of the role of social media in the spread of information and misinformation.

The keyword “misinformation” also stood out with many links to other keywords such as “fake news,” “vaccine hesitancy,” and “digital literacy,” indicating that misinformation is a broad topic and related to many other aspects. This highlights how misinformation can affect public trust during a health crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic. “Fake news” has a close relationship with “media literacy” and “news literacy,” indicating that media literacy is considered one way to tackle the spread of fake news. In addition, the association with “young people” and “young adults” reflects special attention to the impact of fake news on the younger generation.

“Disinformation” is closely connected with “youth,” “social networks,” and “TikTok,” indicating that disinformation is often spread through platforms that are popular among youth. The connection with “journalism” signifies the important role journalism plays in addressing disinformation issues. The keyword “covid-19” connects with “mental health,” “pandemic,” and “trust,” highlighting the widespread impact of the pandemic on mental health and public trust. The association with “misinformation” reflects the challenges of disseminating accurate information during the pandemic.

This figure shows how different keywords are interconnected through lines that represent relationships between topics. The thickness and number of lines indicate how strongly and how often two keywords co-occur in the same research context. The thick connection between “social media” and “misinformation” indicates a strong link between the use of social media and the spread of misinformation. The connections between “fake news,” “media literacy,” and “news literacy” highlight the importance of literacy in combating fake news and improving public understanding of the media.

This visualization provides deep insights into the structure and dynamics of discussions related to disinformation, social media, and media literacy. Keywords such as “social media,” “misinformation,” “fake news,” and “disinformation” occupy a central position and have many relationships with other topics, reflecting their key role in the current information landscape. The close relationship with literacy and health-related keywords indicates the importance of education and health approaches in addressing information challenges in the digital age. This analysis can serve as a basis for further research in developing effective strategies to improve information literacy and reduce the negative impact of misinformation and disinformation in society.

Discussion

The findings of this bibliometric analysis have significant implications for future research on information disorder and its impact on adolescents in the context of social media. The findings of this bibliometric analysis both support and extend our understanding of how Uses and Gratification Theory and Media System Dependency Theory apply to adolescents’ interaction with information disorder. The increasing trend in publications, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, aligns with MSD theory’s prediction about increased media dependency during periods of uncertainty. Similarly, the keyword analysis revealing themes of information seeking, social connection, and entertainment corresponds with the gratifications identified in UGT.

The geographic distribution of research contributions suggests that while information disorder is a global phenomenon, its study and theoretical understanding may be influenced by cultural and social contexts. This raises important questions about how UGT and MSD theory might need to be adapted or extended to account for cultural differences in media use and dependency patterns.

The integration of Uses and Gratification Theory (UGT) and Media System Dependency Theory (MSD) provides a sophisticated theoretical framework essential for understanding how adolescents interact with information disorder on social media platforms. UGT, originally developed by Katz et al. (1973), posits that individuals actively select media based on specific needs and anticipated gratifications—an approach particularly relevant for comprehending why adolescents engage with potentially misleading content. Our bibliometric analysis reveals that recent research by Walter et al. (2021) extends this theory to demonstrate how adolescents’ gratification-seeking behaviour intensifies during periods of uncertainty, creating a complex interplay between motivation and vulnerability to misinformation.

The patterns identified in our citation analysis reflect the evolution of UGT applications in the digital environment, where traditional gratifications (information-seeking, social connection, entertainment) are now complicated by platform-specific features that may amplify these motivations in potentially problematic ways. This theoretical development is evident in clusters 1 and 2 of our keyword analysis, where terms like “disinformation,” “youth,” and “media literacy” frequently co-occur, suggesting a recognition in research of how gratification mechanisms influence adolescents’ interactions with problematic content.

Media System Dependency Theory, as conceptualised by Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur (1976), complements UGT by elucidating how reliance on media systems intensifies during societal uncertainty—a phenomenon strikingly apparent in our temporal publication analysis, which shows significant increases during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Tandoc and Lee's (2022) highly cited work, identified in our bibliometric analysis, demonstrates how information-seeking gratifications became increasingly entangled with systemic media dependencies during this crisis period, generating conditions where adolescents became particularly susceptible to misinformation.

Our analysis of collaboration networks further reveals how researchers are increasingly examining the intersection of these theories. For instance, Pennycook’s central position in the citation network (with 14 links) illustrates the growing recognition that cognitive aspects of misinformation processing cannot be separated from motivation and dependency factors. Similarly, Featherstone and Zhang's (2020) research, prominently featured in our citation analysis, found that emotional gratifications sought through social media sharing can override critical evaluation processes, particularly when media dependency is high during crisis events. This directly corresponds with cluster 3 in our keyword analysis, where “social media,” “COVID-19,” and “mental health” are closely associated.

The geographic distribution of research contributions identified in our analysis suggests cultural variations in how UGT and MSD manifest across different societies. Our findings show that researchers from individualistic cultures (United States, United Kingdom) tend to emphasise personal gratification aspects, while those from collectivistic cultures (China, Malaysia, Indonesia) more frequently examine community-oriented dependencies and social validation gratifications—a distinction that has significant implications for developing culturally appropriate interventions.

The technological dimension revealed in our bibliometric analysis adds further complexity to traditional UGT and MSD frameworks. Studies by Haimson et al. (2021), which appear in our top citation list, suggest that platform-specific algorithmic features can create unique gratification-dependency cycles. This technological mediation of gratification and dependency processes necessitates an evolution of these theoretical frameworks to account for how platform design influences user behaviour and information exposure—a connection clearly visible in the co-occurrence of “TikTok” with “disinformation” and “youth” in our keyword cluster 1.

These theoretical insights derived from our bibliometric analysis not only enrich our understanding of the relationship between adolescents and information disorder but also suggest more targeted approaches for intervention strategies. The integration of UGT and MSD perspectives helps explain why certain platform features may be particularly problematic for adolescent users and how intervention strategies might be better tailored to address both gratification-seeking behaviours and dependency patterns simultaneously. For example, media literacy programmes (prominently featured in keyword cluster 2) could be enhanced by addressing not just critical evaluation skills but also the gratification mechanisms that drive engagement with problematic content.

Furthermore, the evolution of these theories, as reflected in our temporal analysis of publications, suggests that future research should continue to explore how emerging technologies like AI-generated content interact with existing patterns of gratification and dependency among adolescents. This theoretical trajectory is particularly important as we consider potential interventions in the rapidly evolving information ecosystem identified in our research recommendations.

Critical analysis of research landscape: gaps, limitations, and contradictions

Our bibliometric analysis not only reveals important trends in research on information disorder and adolescents, but also sheds light on several critical issues that warrant deeper examination. A thorough review of the literature uncovers significant gaps, methodological limitations, and conceptual contradictions that collectively hinder our understanding of how adolescents engage with misinformation in digital environments.

The current research landscape exhibits a concerning imbalance between descriptive documentation and causal investigation. While Pennycook and Rand's (2019) highly cited work has enhanced our understanding of cognitive factors in susceptibility to misinformation, the field markedly lacks robust longitudinal studies that explore how repeated exposure to misinformation affects adolescent cognitive development over time. This gap is particularly troubling, considering that adolescence is a crucial period for developing critical thinking skills and epistemic beliefs. The predominance of cross-sectional designs in the literature—evident in our citation patterns—restricts our ability to establish causal relationships between exposure to misinformation and long-term psychological or behavioural outcomes.

Furthermore, our keyword analysis reveals a concerning disconnect between research streams focusing on interventions (cluster 2: “media literacy,” “news literacy”) and those examining psychological impacts (cluster 3: “mental health,” “trust”). This fragmentation suggests that interventional studies seldom incorporate robust psychological outcome measures, while mental health research frequently neglects media literacy dimensions. Consequently, we lack integrated models that connect media literacy interventions with measurable psychological outcomes—a link essential for developing effective educational approaches.

This siloed approach is further complicated by inconsistent operationalisation of key concepts. The terms “youth,” “young people,” and “adolescents” appear across different keyword clusters but often reference divergent age ranges—some narrowly focusing on teenagers (13–18 years), others encompassing broader youth populations (up to 25 years). This definitional inconsistency undermines cross-study comparisons and hinders the development of developmentally calibrated interventions. Similarly, terms like “fake news,” “misinformation,” and “disinformation” frequently appear in separate keyword clusters, suggesting conceptual fragmentation that complicates theoretical integration.

Methodologically, numerous influential studies in our citation analysis rely heavily on self-reported measures of media consumption and misinformation exposure—an approach particularly problematic with adolescent populations who may lack awareness of their own susceptibility or exposure levels. The relative scarcity of behavioural and experimental measures in highly cited works raises questions about the ecological validity of current findings. Additionally, content analysis methodologies—essential for understanding the nature of misinformation that adolescents encounter—seem underutilised in the literature compared to survey-based approaches, creating an incomplete picture of the information environment.

The geographic distribution of research represents another significant limitation. Despite social media’s global reach, research contributions remain heavily concentrated in Western contexts, with the United States alone accounting for 84 documents and 2,804 citations in our analysis. While some developing nations appear in our country analysis (Malaysia, Nigeria, Indonesia), their proportional representation remains limited. This imbalance is particularly concerning given that social media usage patterns, regulatory frameworks, and misinformation dynamics vary substantially across cultural contexts. The research community’s limited engagement with diverse cultural settings raises questions about the generalisability of current findings and potentially overlooks unique manifestations of information disorder in non-Western contexts.

Platform-specific research patterns reveal additional blind spots. Our keyword analysis shows TikTok emerging in cluster 1 alongside “disinformation” and “youth,” indicating a growing recognition of its importance. However, the volume of TikTok-focused research remains disproportionately small compared to its rapidly expanding user base among adolescents. This lag between platform adoption and research attention creates a perpetual knowledge gap about emerging vectors of misinformation—a gap that widens as new platforms continually emerge and gain popularity among younger users.

Aside from these gaps and limitations, our analysis reveals several significant contradictions in research findings that warrant critical examination. For example, differing theoretical frameworks provide competing explanations for adolescent vulnerability to misinformation. Some highly cited studies, such as Pennycook and Rand (2019), emphasise cognitive processing deficiencies, while others, like Chadwick et al. (2021), underscore emotional and social influences. These apparent contradictions likely reflect the complex, multi-faceted nature of misinformation susceptibility—a complexity that many studies fail to adequately capture by concentrating on isolated factors rather than integrated models.

Likewise, the efficacy of interventions presents contradictory evidence across the literature. Walter et al.'s (2021) meta-analysis of correction attempts on social media indicates modest overall effects, which contradicts the more optimistic findings of individual intervention studies. This disparity suggests a potential publication bias favouring successful interventions and highlights methodological inconsistencies in how effectiveness is measured. The contradictions surrounding intervention efficacy are particularly troubling given the pressing need for evidence-based approaches to addressing information disorder among vulnerable adolescent populations.

The influence of prior knowledge and beliefs represents another area of contradictory findings. While some research indicates that domain expertise offers protection against misinformation, other studies point out that strong prior beliefs can actually heighten vulnerability through motivated reasoning processes. These contradictions emphasise the complex interaction between cognitive, affective, and social factors in misinformation processing—interactions that remain insufficiently theorised in much of the literature. The field’s propensity to examine these factors in isolation, rather than through integrated models, limits our understanding of how different variables interact within real-world information environments.

Conceptually, most research adopts a relatively narrow focus on factual accuracy, neglecting broader dimensions of information quality such as contextualisation, framing effects, and emotional manipulation. This conceptual limitation hinders the development of comprehensive interventions that address the full spectrum of problematic content adolescents encounter. Furthermore, the research community has insufficiently examined how algorithmic curation shapes adolescent exposure to misinformation—a critical gap given that platform algorithms increasingly dictate what content users encounter.

Perhaps most fundamentally, much research implicitly regards adolescents as passive recipients of misinformation rather than as active participants who may create, modify, and amplify content. This conceptual limitation overlooks adolescents’ agency within information ecosystems, failing to recognise how developmental factors shape their engagement with digital content. A more nuanced approach would acknowledge both adolescents’ active participation in information environments and the developmental constraints that may limit their critical evaluation capabilities.

These critical gaps, methodological limitations, and conceptual contradictions not only highlight the evolving nature of this research field but also provide valuable direction for future studies. Addressing these issues will require methodological innovation, theoretical refinement, and greater interdisciplinary collaboration across the research clusters identified in our bibliometric analysis. Future research must advance beyond descriptive documentation towards explanatory models that capture the complex, multifaceted nature of adolescent engagement with information disorder in digital environments.

Adolescent-specific vulnerabilities to information disorder: cognitive, psychological, and social dimensions

The results of the bibliometric analysis highlight the need for a more nuanced understanding of why and how adolescents are uniquely vulnerable to information disorder. While general patterns of misinformation susceptibility have been well documented in the broader literature, adolescents exhibit distinct vulnerabilities arising from their developmental stage, social contexts, and digital engagement patterns—facets that require more detailed examination.

From a cognitive development perspective, adolescence represents a critical period characterised by significant neural reorganisation and the development of executive functions essential for information evaluation. Research by Breakstone et al. (2021), identified in our citation analysis, demonstrates that adolescents’ ability to distinguish between credible and misleading information is still maturing, with many lacking the advanced metacognitive skills necessary to effectively evaluate source credibility. This developmental limitation is particularly consequential in digital environments where content is abundant, attention is fragmented, and cues to credibility may be subtle or manipulated.

The cognitive vulnerability of adolescents to information disorder extends beyond basic fact-checking abilities to encompass more complex cognitive biases that affect information processing. Studies have found that confirmation bias—the tendency to favour information that confirms existing beliefs—may be particularly pronounced during adolescence as individuals develop and solidify their identities and worldviews. This vulnerability intersects with the algorithmic curation of content on social media platforms, creating personalised information environments that can reinforce existing beliefs while limiting exposure to diverse perspectives. This phenomenon appears particularly problematic for adolescent cognitive development, as suggested by the co-occurrence of “social media” and “misinformation” in our keyword analysis.

The cognitive dimensions of adolescent vulnerability are further complicated by emotional and social factors specific to this developmental stage. Adolescence is characterised by heightened emotional reactivity and sensitivity to social rewards, which may influence information-sharing behaviours by prioritising peer approval over accuracy considerations. Featherstone and Zhang's (2020) research on emotional reactions to vaccine misinformation, prominently featured in our citation analysis, indicates that emotional content is particularly likely to be shared without critical evaluation—a finding with significant implications for understanding adolescent engagement with misinformation given their heightened emotional responsivity.

From a psychological perspective, information disorder poses several specific threats to adolescent well-being that extend beyond mere exposure to inaccurate content. Our keyword analysis reveals an emerging recognition of these connections, with “mental health” appearing in cluster 3 alongside “social media” and “covid-19.” This association suggests growing research attention to how exposure to conflicting information during crisis events may contribute to psychological distress among adolescents—a connection that requires further empirical investigation given the potential long-term consequences for adolescent development.

The psychological impact of information disorder on adolescents is multifaceted. First, exposure to conflicting information may contribute to heightened uncertainty and anxiety, particularly around health-related topics, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, engagement with polarising misinformation may reinforce group-based identities in ways that intensify social division and identity-based conflicts—a particular concern during adolescence when identity formation is a central developmental task. Third, repeated exposure to fake news and the recognition of being misled may contribute to a generalised epistemic mistrust that extends beyond specific content to include legitimate information sources and institutions—potentially undermining adolescents’ civic development and engagement.

These psychological vulnerabilities are not uniformly distributed across adolescent populations. Our geographic analysis reveals significant variations in research attention towards different populations, with studies from Western contexts predominating. This global interest underscores the universal nature of the challenge and the need for international collaborative efforts (Vraga and Bode, 2020). Such collaborative efforts are crucial for developing comprehensive strategies to address adolescent information disorder (Freelon and Wells, 2020).

The social contexts in which adolescents engage with digital media further shape their vulnerability to information disorder. While peer influence has been extensively studied in relation to adolescent risk behaviours, its role in misinformation susceptibility requires greater attention. The social validation of content through likes, shares, and comments—metrics highly visible on platforms popular among adolescents—may override critical evaluation processes, particularly given adolescents’ heightened sensitivity to peer approval. This aligns with Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory, which suggests that cultural values significantly impact how individuals interpret and respond to information (Hofstede, 2011). Such research could provide valuable insights into the development of culturally sensitive interventions and policies (Nisbett and Masuda, 2003).

Educational contexts also play a crucial role in shaping adolescent vulnerability to misinformation. Our keyword analysis identifies “media literacy” and “news literacy” as significant terms in cluster 2, indicating recognition of the importance of educational interventions. However, substantial disparities exist in access to quality media literacy education, with many school systems lacking comprehensive curricula that address contemporary digital challenges. These educational gaps, which often align with existing socioeconomic disparities, create uneven protection against misinformation exposure and may compound existing social inequalities.

The intersection of cognitive development, psychological vulnerability, and social context creates complex patterns of risk that current research has only partially addressed. Most notably, longitudinal studies examining how exposure to misinformation affects adolescent development over time remain scarce, limiting our understanding of long-term consequences. Additionally, research typically treats adolescents as a homogeneous group rather than recognising significant developmental differences between early, middle, and late adolescence—differences that likely influence misinformation susceptibility and processing in important ways.

Furthermore, our keyword analysis reveals a limited integration between research on information disorder and developmental psychology, with few studies explicitly incorporating developmental frameworks to understand age-specific vulnerabilities. This represents a significant missed opportunity, as developmental science offers robust theoretical models for understanding the cognitive, emotional, and social changes that define adolescence and shape engagement with digital information. Addressing these gaps requires more nuanced research approaches that consider adolescent-specific vulnerabilities while avoiding simplistic narratives of digital victimisation. Adolescents are not merely passive recipients of misinformation; they are active participants in complex information ecosystems, often demonstrating considerable digital proficiency alongside specific vulnerabilities. Future research must balance recognition of developmental constraints with an acknowledgment of adolescents’ agency and capacity for critical engagement when properly supported. Moreover, intervention approaches must progress beyond generic media literacy towards developmentally calibrated programmes that address the specific cognitive, emotional, and social factors influencing adolescent engagement with misinformation. Such interventions should be culturally responsive, recognising how cultural contexts impact both the manifestation of information disorder and effective response strategies—a dimension highlighted by the geographic distribution of research identified in our bibliometric analysis.

The study highlights the particular vulnerability of adolescents to misinformation and disinformation, emphasizing the need for more focused research on how these phenomena affect adolescent cognitive development, decision-making abilities, and social interactions (Breakstone et al., 2021). As revealed in the analysis, the United States leads in publications related to the impact of misinformation, with significant contributions from countries such as Spain, the United Kingdom, and Australia. This global interest underscores the universal nature of the challenge and the need for international collaborative efforts (Vraga and Bode, 2020). These collaborative efforts are crucial for developing comprehensive strategies to address adolescent information disorder (Freelon and Wells, 2020).

Given the global nature of social media and information disorder, there is a pressing need for cross-cultural comparative analysis. The study reveals that countries such as Korea, India, and Nigeria view misinformation as a social challenge, emphasizing the need for more research on how cultural dimensions influence the creation and spread of misinformation. This aligns with Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory, which suggests that cultural values significantly impact how individuals interpret and respond to information (Hofstede, 2011). Such research could provide valuable insights into developing culturally sensitive interventions and policies (Nisbett and Masuda, 2003).

The emergence of TikTok as a significant vector for information disorder presents unique challenges and research opportunities. Our keyword analysis shows “TikTok” appearing in Cluster 1 alongside “disinformation” and “youth,” indicating its growing significance in the information disorder ecosystem. This platform’s distinctive features—short-form videos, algorithmic content distribution, and predominantly young user base—create novel dynamics for misinformation spread. Recent studies by Basch et al. (2021) demonstrate how TikTok’s format can amplify the viral spread of health misinformation, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. The platform’s unique characteristics, such as rapid content replication through “duets” and “stitches,” create new patterns of information disorder that differ from traditional social media platforms.

Furthermore, the platform’s sophisticated algorithm and emphasis on entertainment align with Uses and Gratification Theory, as adolescents seek both information and entertainment simultaneously. This dual gratification pattern may increase vulnerability to misinformation, as entertainment-focused content modalities can make misleading information more engaging and shareable. The rise of “infotainment” on TikTok represents a significant evolution in how adolescents encounter and interact with potential misinformation, necessitating new approaches to digital literacy and platform-specific intervention strategies.

This research could inform the development of more effective platform-level interventions to mitigate the spread of false information. The study emphasizes the central role of platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram in spreading misinformation, particularly during events such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Cinelli et al., 2020).

This study’s key finding is the importance of media literacy as a tool to combat fake news and improve public understanding, especially among adolescents. Media literacy is recognised as a vital means of protecting against false information, leading to debates on the efficacy of current initiatives and the optimal methods for incorporating them into educational institutions (Bennett and Livingston, 2018). Partnerships between media literacy campaigns and technology tools, such as fact-checking techniques, are crucial.

Additional research is required to identify and tackle the difficulties linked to implementing media literacy in various cultural contexts. Future research should focus on developing and evaluating targeted interventions to enhance adolescents’ digital literacy skills. This includes assessing the effectiveness of current media literacy programs and exploring innovative approaches to equip young people with the critical thinking skills necessary to navigate the complex digital information landscape (Kahne and Bowyer, 2017; Martens and Hobbs, 2015).

These theoretical insights not only enrich our understanding of the relationship between adolescents and information disorder but also suggest more targeted approaches for intervention strategies. The integration of UGT and MSD perspectives helps explain why certain platform features may be particularly problematic for adolescent users and how intervention strategies might be better tailored to address both gratification-seeking behaviours and dependency patterns simultaneously.

The potential link between exposure to misinformation and mental health outcomes, particularly during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, warrants further investigation. Research is needed to explore the psychological effects of persistent exposure to false information and how social media platforms might promote beneficial mental health practices (Gao et al., 2020; McCashin and Murphy, 2023). This highlights the necessity for multidisciplinary studies incorporating psychology, communication, and public health perspectives.

The study also underscores the significance of examining the extent to which young adults are exposed to misinformation and the factors contributing to vaccine hesitancy among this demographic (Buchanan and Benson, 2019; Loomba et al., 2021). Developing targeted public health initiatives and engaging community leaders and healthcare providers are essential strategies that require further research and evaluation.

The role of cultural dimensions in understanding and addressing information disorders globally is a crucial aspect highlighted in this study. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory provides a valuable framework for analyzing how cultural values impact individuals’ reactions to misinformation (Hofstede, 1984, 2011). This emphasizes the need for tailored strategies and international collaboration to combat information disorder across diverse cultural contexts effectively (Huettinger, 2008; Kirkman et al., 2006).

The influence of cultural aspects on addressing information disorder is a crucial aspect of research, which examines how cultural elements affect endeavours to combat disinformation (Jamalzadeh et al., 2022). Gaining an understanding of cultural norms and values can offer valuable insights into how individuals interpret and react to misinformation. Effective mitigation of information disorder requires the implementation of culturally sensitive measures, which can be achieved through collaborative initiatives and international cooperation (MacKinnon et al., 2021).

Geert’s cultural dimensions theory has been widely used in empirical studies, particularly in international business and psychology contexts (McSweeney, 2002). This framework offers a structured approach to analyzing cultural differences and their implications for various societal aspects, including information dissemination and collaboration strategies (Hofstede and McCrae, 2004).

Future research should also focus on developing strategies to build cognitive resilience among adolescents to mitigate the negative impacts of exposure to misinformation. This could include studying the effectiveness of critical thinking training and emotional regulation techniques (Guess et al., 2020). Research could contribute to developing educational programs that equip young people with the skills to navigate the complex digital information ecosystem.

This bibliometric analysis provides a comprehensive overview of the current research landscape regarding information disorder and its impact on adolescents. It highlights key areas for future research, including cross-cultural studies, platform-specific investigations, interdisciplinary approaches, and the development of targeted interventions. By pursuing these diverse research directions, scientists can contribute to developing more effective strategies to empower adolescents in navigating the digital information landscape, ultimately leading to more robust solutions for this pressing global challenge (Livingstone and Stoilova, 2021).

Conclusion

The bibliometric analysis of research on information disorder and its impact on adolescents reveals a complex, multifaceted challenge that demands continued interdisciplinary investigation and global collaboration. The significant annual increase in publications underscores the growing academic interest in this critical issue, with contributions from both developed and developing countries highlighting its global nature. The centrality of social media platforms in the spread of misinformation among adolescents, coupled with the recurring theme of media literacy, emphasizes the need for targeted interventions and comprehensive educational strategies.

The analysis uncovers the profound psychological and social impacts of information disorder on adolescent development, particularly in the context of major global events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the emerging importance of cultural dimensions in addressing information disorder globally suggests the necessity for culturally sensitive approaches in combating misinformation. As the digital landscape continues to evolve with new platforms like TikTok, ongoing research is crucial to understand their influence on information dissemination among young people.

Our bibliometric analysis of 227 articles (2019–2024) yields several actionable insights. The citation patterns reveal that cross-disciplinary research tends to have higher impact, as demonstrated by highly-cited works combining psychological, social, and technological perspectives. Geographic analysis shows that while the United States leads in quantity (84 publications), significant contributions come from diverse regions, suggesting the need for more international collaborative efforts. The keyword analysis highlighting “media literacy” and “digital literacy” points to the growing recognition of educational interventions as crucial solutions.

Based on our comprehensive bibliometric analysis, we propose several actionable recommendations for key stakeholders addressing the impact of information disorder on adolescents. For educational institutions and practitioners, we recommend implementing developmentally appropriate media literacy programmes that go beyond simple fact-checking to address the emotional and social dimensions of misinformation. These programmes should be integrated across the curriculum rather than treated as standalone units, with particular attention to emerging platforms like TikTok, which our analysis identifies as increasingly significant vectors for misinformation among youth. Educational approaches should balance critical evaluation skills with recognition of adolescents’ agency and digital capabilities, avoiding deficit-focused narratives while providing appropriate scaffolding.

For technology platforms and policymakers, our findings highlight the inadequacy of current content moderation approaches in addressing adolescent-specific vulnerabilities. Priority should be given to developing transparent, age-appropriate mechanisms that introduce reflective friction before sharing emotionally evocative content, while establishing regulatory frameworks that mandate greater platform transparency. The significant representation of policy-focused research in our citation analysis underscores the importance of evidence-based approaches to platform governance that specifically consider adolescent development.

For researchers, our bibliometric analysis reveals critical gaps that should guide future investigations, particularly the need for longitudinal studies tracking the developmental impacts of exposure to information disorder, methodologies that overcome the limitations of self-reported measures, and expanded research in underrepresented geographic regions. The interdisciplinary nature of research clusters identified in our analysis suggests that collaboration across fields—connecting media studies, developmental psychology, and education—will yield the most comprehensive understanding of this complex phenomenon.

For families and communities, our findings emphasise the importance of collaborative rather than restrictive approaches to supporting adolescents’ information literacy development. Community organisations, libraries, and health professionals can play crucial roles in bridging digital literacy gaps, particularly for underserved populations, by providing accessible resources, hosting intergenerational programmes, and integrating information literacy into existing youth services.

These recommendations require coordinated implementation across multiple levels, recognising both universal aspects of adolescent development and context-specific factors that shape the impact of information disorder. The cross-cultural variations in research focus identified in our geographic analysis highlight the importance of culturally responsive approaches that consider local information ecosystems and social contexts. Through such comprehensive, evidence-informed strategies, we can better equip adolescents with the skills, support systems, and protective environments needed to navigate information disorder while supporting their healthy development in an increasingly complex digital landscape.

Author contributions

II: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TB: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AU: Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2025.1495536/full#supplementary-material

References

Aria, M., and Cuccurullo, C. (2017). Bibliometrix: an R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informet. 11, 959–975. doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007

Baiyere, A., and Hukal, P. (2020). Digital disruption: a conceptual clarification. doi: 10.24251/HICSS.2020.674

Ball-Rokeach, S. J., and DeFleur, M. L. (1976). A dependency model of mass-media effects. Commun. Res. 3, 3–21. doi: 10.1177/009365027600300101

Basch, C. H., Meleo-Erwin, Z., Fera, J., Jaime, C., and Basch, C. E. (2021). A global pandemic in the time of viral memes: COVID-19 vaccine misinformation and disinformation on TikTok. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 17, 2373–2377. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1894896

Bennett, W. L., and Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. Eur. J. Commun. 33, 122–139. doi: 10.1177/0267323118760317

Breakstone, J., Smith, M., Wineburg, S., Rapaport, A., Carle, J., Garland, M., et al. (2021). Students’ civic online reasoning: a national portrait. Educ. Res. 50, 505–515. doi: 10.3102/0013189X211017495

Brika, S. K. M. (2022). A bibliometric analysis of Fintech trends and digital finance. Front. Environ. Sci. 9:796495. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2021.796495

Buchanan, T., and Benson, V. (2019). Spreading disinformation on Facebook: do Trust in message source, risk propensity, or personality affect the organic reach of “fake news”? Soc. Media Soc. 5:205630511988865. doi: 10.1177/2056305119888654

Chadwick, A., Kaiser, J., Vaccari, C., Freeman, D., Lambe, S., Loe, B. S., et al. (2021). Online social endorsement and Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy in the United Kingdom. Soc. Media Soc. 7:205630512110088. doi: 10.1177/20563051211008817

Chen, C., Hu, Z., Liu, S., and Tseng, H. (2012). Emerging trends in regenerative medicine: a scientometric analysis in CiteSpace. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 12, 593–608. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.674507

Cinelli, M., Quattrociocchi, W., Galeazzi, A., Valensise, C. M., Brugnoli, E., Schmidt, A. L., et al. (2020). The COVID-19 social media infodemic. Sci. Rep. 10:16598. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73510-5

Cobo, M. J., López-Herrera, A. G., Herrera-Viedma, E., and Herrera, F. (2012). SciMAT: a new science mapping analysis software tool. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 63, 1609–1630. doi: 10.1002/asi.22688

Cordeiro, E. R., Lermen, F. H., Mello, C. M., Ferraris, A., and Valaskova, K. (2024). Knowledge management in small and medium enterprises: a systematic literature review, bibliometric analysis, and research agenda. J. Knowl. Manag. 28, 590–612. doi: 10.1108/JKM-10-2022-0800

Dharmawan, A., Dewi, P. A. R., and Gusma, F. D. (2023). Autopoeisis of local Media in East Java in the era of information disruption (pp. 236–243). doi: 10.2991/978-2-38476-008-4_27

Egelhofer, J. L., and Lecheler, S. (2019). Fake news as a two-dimensional phenomenon: a framework and research agenda. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 43, 97–116. doi: 10.1080/23808985.2019.1602782

Featherstone, J. D., and Zhang, J. (2020). Feeling angry: the effects of vaccine misinformation and refutational messages on negative emotions and vaccination attitude. J. Health Commun. 25, 692–702. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2020.1838671

Folkvord, F., Snelting, F., Anschutz, D., Hartmann, T., Theben, A., Gunderson, L., et al. (2022). Effect of source type and protective message on the critical evaluation of news messages on Facebook: randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands. J. Med. Internet Res. 24:e27945. doi: 10.2196/27945

Freelon, D., and Wells, C. (2020). Disinformation as political communication. Polit. Commun. 37, 145–156. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2020.1723755

Gao, J., Zheng, P., Jia, Y., Chen, H., Mao, Y., Chen, S., et al. (2020). Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One 15:e0231924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924

Gradoń, K. T., Hołyst, J. A., Moy, W. R., Sienkiewicz, J., and Suchecki, K. (2021). Countering misinformation: a multidisciplinary approach. Big Data Soc. 8:205395172110138. doi: 10.1177/20539517211013848

Guess, A. M., Lerner, M., Lyons, B., Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., et al. (2020). A digital media literacy intervention increases discernment between mainstream and false news in the United States and India. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 15536–15545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1920498117