- 1Institute for Open and Distance Learning, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

- 2Department of Applied Educational Sciences, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia

- 3Department of Language and Social Education, National University of Lesotho, Roma, Lesotho

- 4Department of Guidance and Counselling, Faculty of Education, Delta State University, Abraka, Nigeria

The language competencies of the deaf students are key to various academic discourses that are associated with the learning outcome of deaf students and social interaction between deaf individuals and non-deaf members of society. Methods to assist the deaf in building appreciable language capacities have been encouraged in various studies. Hence, translanguaging has been found as a concept that could influence the linguistic repertoire of deaf students but there is a dearth of systematic review studies on the influence of translanguaging in deaf education, this study therefore provided evidence on the implication of translanguaging in the education of deaf students. Ten bibliographic databases were identified and comprehensively searched for academic papers on translanguaging in deaf education. Thirteen published articles were carefully selected for in-depth content analysis from 5,937 academic papers. The findings revealed that there is a scarcity of studies on translanguaging in deaf education in Sub-Saharan Africa. This study showed that translanguaging serves as an inclusive fulcrum in deaf education. Furthermore, findings showed that translanguaging can be delivered through a multi-modal approach and such approach can significantly improve the language capabilities of deaf students. Implications were advised for research, policies, and practices of translanguaging in deaf education.

Introduction

There are longstanding academic discourses on the issues surrounding the education of deaf people, and the academic discourses regarding education of the deaf have continued unabated for several decades. Such discussions within the academic space are not limited to a single geographical location, but academic discourses and research into deafness and deaf education are more evident in the developed countries/economies than in the developing nations of Sub-Saharan Africa. This is despite the fact that many developing countries, especially Sub-Saharan African nations, have an appreciable diverse population of deaf students (Kiyaga and Moores, 2003). Of the estimated 360 million deaf persons worldwide, the WHO reports indicate that about 39.9 million Africans are deaf (Adigun et al., 2024; WHO, 2017; World Bank, 2021). Despite the largely reported population of deaf people in Africa, there is less research effort coming from the continent on the issues of deaf education and deaf studies. In fact, there is sparse research evidence on issues of language dynamics and translanguaging in particular among deaf student from various countries of Africa whereas, there are numerous research activities that has been reported in literature on language issues among deaf people in developed nations (for instance, see: Lindberg, 2021; Miller et al., 2020; Simpson and Mayer, 2023; Villwock et al., 2021; Zhou, 2022).

Several studies have documented the language deprivations and linguistic competencies among deaf students for academic purposes (Adigun and Ajayi, 2015; Dostal and Wolbers, 2014; Humphries et al., 2016; Musyoka, 2023). In particular, evidence was gathered regarding the negative effects of deafness on the expected written language competency (particularly in the English Language) in the academic performance of deaf students (Howerton-Fox and Falk, 2019; Hrastinski and Wilbur, 2016; Kumatongo and Muzata, 2021). Following various heated debates surrounding issues on oralism1 versus the use of sign language2 in education of the deaf, Musyoka (2023) noted that there has been development and implementation of language policies in deaf education. However, Grosjean (2008) and Holmström and Schönström (2018) averred that some educational systems place emphasis on the use of sign language according to their beliefs that deaf students must be given the privilege of being bilingual, that is, using sign language and the English language for communication. Based on the submissions by Grosjean (2008), Holmström and Schönström (2018), Aldersson (2023), and Musyoka (2023) asserted that the belief and/or expectation that educational systems should place emphasis on bi/multi-lingualism for deaf students was in agreement with the principles of translanguaging. However, a scoping review of the implication of translanguaging as a concept and a construct to influence the academic performances of deaf learners has remained vague in existing academic research papers until now. This study was hence designed to:

i. Determine the extent of the research on the implications of translanguaging in education of deaf students.

ii. Cumulatively establish the effects of translanguaging on the learning outcomes of deaf students.

Literature review

Deaf education and deaf people’s language use for academic purposes

Deaf education has a long-standing history in the discourse of education for learners with special educational needs. For several decades, the education of deaf people has undergone several modifications based on the need to enhance linguistic competencies and academic performances in accordance with recurrent changes in educational curricula. As indicated by Marschark and Knoors (2012) and Richardson et al. (2010) education of deaf students have over the years aimed to address various dimension of educational, cultural, linguistic and psychosocial issues that influence daily experience of deaf people. Hence, Richardson et al. (2010) stated that deaf education is provided on a continuum of services based on their individual differences and needs. Recent studies have shown that diversities among deaf people based on various characteristics that include but not limited to type, degrees, onset or severities of deafness, use of sign language or amplification devices and or family type among other have been established as factors that influence education of deaf people as well as their linguistic competencies (Adigun and Nzima, 2021; Allen and Morere, 2020; Alothman, 2021; Marschark et al., 2007; Howerton-Fox and Falk, 2019).

Despite decades of research, evidence available in literature have shown that deaf students lag behind in linguistic competency of deaf students when compared with their non-deaf peers (Adigun and Ajayi, 2015; Glaser and Van Pletzen, 2012; Kumatongo and Muzata, 2021; Lindberg, 2021; Napier et al., 2019; Richardson et al., 2010). While such existing studies have further established that linguistic competencies are significantly needs for communication, calls and recommendations have been made by various stakeholders to work toward the development of modalities that will further increase the linguistic capacities and potentials of deaf students for academic and social purposes. Although, researchers in deaf education and deaf studies have initiated various action research to determine the efficacies of various strategies that can enhance the linguistic performance and competencies of deaf students but until this current time, there is yet a paucity of studies that have cumulative determine the implication of translanguaging in deaf education. Therefore, this current study has bridged the existing research gap through this current systematic review of the implication of translanguaging on the linguistic competencies of deaf students.

Translanguaging: an exposé of concept and meaning

Translanguaging is a term used to describe the language practices of bilingual and/or multilingual persons. The concept of translanguaging is a practice in which an individual makes complex, simultaneous use of two or more languages for communication (Garcia, 2014). In other words, Garcia (2014) alluded that the praxis of translanguaging underscores an individuals’ flexibility in the use of their complex linguistic potentials to converse meaningfully with others. The concept of translanguaging has been discussed extensively in various academic fora for more than three decades (Canagarajah, 2011; Catherine, 2017; Chaka, 2020; Liu and Fang, 2022). Existing studies have also shown that language practices have been theorized using translanguaging to further explain the principle of choice when there is contention in the interpretations of languages (Mendoza, 2020). As described by Catherine (2017), translanguaging is a language ideology and practice where the use of language is transformational. Others, for example, Canagarajah (2011) and Liu and Fang (2022), averred that translanguaging is “the ability of multilingual speakers to shuttle between languages, treating the diverse languages that form their repertoire as an integrated system.”

Holmström and Schönström (2018) viewed translanguaging as a set of pedagogical practices where multilingualism is the norm. Translanguaging as a concept has gained recognition within the educational sector. According to Wright and Baker (2017), De Meulder et al. (2019), García and Wei (2014), Musyoka (2023), and Swanwick et al. (2022), there has been an unprecedented increase in concerns within academic spaces about how individuals naturally use known languages to promote teaching and learning activities. Over the past few years, a plethora of studies have advanced the pedagogical implications of translanguaging (Catherine, 2017; Chaka, 2020; García and Wei, 2014; Holmström and Schönström, 2018; Liu and Fang, 2022). Williams (1996) asserted that translanguaging is a pedagogical construct within the educational sector that is used to designate or describe how bi−/multilingualism is used in the teaching and learning domain to clarify terms and concepts. Thus, Wright and Baker (2017) averred that translanguaging is a dynamic but holistic view of language praxis that provides a platform where the use of a variety of languages (bi−/multilingualism) influences the shifting from “context-to-context,” “construct-to-construct” and “relationship-to-relationship.”

Holmström and Schönström (2018) averred that the adoption of bilingual and multilingual educational settings may have a positive impact on social relationships and identities among learners. Other studies such as those by García and Wei (2014), Mendoza (2020), and Seltzer and Collins (2016) have indicated that the theory and praxis of translanguaging in the classroom has fostered cultural and social identities among individuals with linguistic repertoires (spoken and written) and semiotic resources. Mendoza (2020) and Aldersson (2023) were of the opinion that translanguaging as a pedagogic approach reinforces the flexibility of the language practices of bilingual or multilingual students. Mendoza (2020) and Wolbers et al. (2023) believed that translanguaging is a paradigm shift that provides advanced opportunities for an accessible and inclusive education where students’ diversity is equally valued. Therefore, based on these previous studies and the submissions by Aldersson (2023), Mendoza (2020); and Musyoka (2023), translanguaging may be a transformative pedagogical strategy that offers possibilities for advancing the learning outcomes of deaf students. In other words, through translanguaging, deaf students may have unrestrained capacities to use their linguistic repertoires (written, signed and spoken) for communication within academic spaces.

Translanguaging, deaf students, and learning outcomes

The deaf population is diverse, with variations in language usage and competency. Variation among the deaf population is a complex phenomenon that cannot only be explained by the onset or degree of deafness, but also by cultural and social diversities especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. Regardless of the variations, difficulties with the efficient use of hearing for auditory-verbal communication remain a unifying factor for all deaf people. Deaf people also have the special ability to develop and employ various strategies and techniques to advance their linguistic resources for written and spoken communication (Adigun, 2019). Kusters et al. (2017) indicated that deaf people use a combination of strategies to increase clarity and understanding of their ideas for their audience. In other words, Kusters et al. (2017) believe that deaf people make their feelings, ideas, messages and thoughts known to their audience through monolingual, bi- and multi-lingual approaches based on varying degrees of proficiencies.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, there are variations in the sign languages used by Africans (Kaniei, 2004). While sign languages are used in teaching and learning processes in deaf mainstream/inclusive deaf schools particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, many schools for such schools combine the use of the English language and sign language in teaching deaf students (Matende et al., 2021; Ngobeni et al., 2020; Obosu et al., 2023). This approach has predominantly been adopted based on the variations in the characteristics of the deaf students in the classrooms. Such variations include factors that involve, but are not limited to, the onset and degrees of deafness; usage of assistive listening devices; and family factors, such as whether the students use spoken and/or signed communication and/or whether the deaf students come from deaf families. Irrespective of the forgoing factors, when compared to spoken languages, the use of sign language allows deaf people to convey meanings, messages, and thoughts in a single sign with a combination of expressions, gestures and/or other body movements (Adigun, 2019; Wolbers et al., 2023).

As students, deaf students are expected to be able to convey their thoughts and express themselves in writing (Adigun and Ajayi, 2015; Holcomb, 2023). Studies have shown that though, deaf students may have enough signed linguistic repertoire, they may have challenges with linguistic structures when documenting their ideas on paper (Adigun and Ajayi, 2015; Hoffmeister et al., 2022; Holcomb, 2023), As indicated by Hoffmeister et al. (2022), the writing patterns of deaf students may display errors such as disconnected words, incorrect use of conjunctions, mistakes in the agreement of verbs, as well as disjointed sentences or phrases. Despite the challenges in the writing skills of deaf students (Adigun and Ajayi, 2015), some studies reveal a significant positive effect of using sign language and fingerspelling on deaf students’ potential to recognize English letters and words. Sign language and fingerspelling can thus assist these students and foster proper sentence construction in the English language (Allen and Morere, 2020; Wolsey et al., 2018).

The research focus has recently shifted to the assessment of the potency of the effect of translanguaging on language practices among deaf students. In other words, there has been an ideological shift in how to further understand the language repertoire and the use of translanguaging among deaf students for academic purposes. Wolbers et al. (2023) admitted that this ideological shift has helped with recognition and appreciation of the linguistic resources of deaf people and of the diversity across personal communicative and language repertoires. In line with this submission by Wolbers et al. (2023) and Scott and Cohen (2023) noted that the linguistic repertoires and communicative diversities made possible with the pedagogical approach of translanguaging go beyond the exposure of deaf students to the complexities of language for daily usage, as translanguaging has the potential to assist deaf students to present complex information in a manner that can easily be understood. According to Holcomb (2023), translanguaging in deaf education has continuously been identified as a concept that has the capacity to expand social accessibilities and interaction between the deaf members of communities.

The findings from the studies of Duggan et al. (2023), Hoffman et al. (2017), and Swanwick et al. (2022) similarly extended the value of translanguaging as a pedagogical strategy to boost the academic efficiency of deaf students. Furthermore, while Hoffman et al. (2017) affirmed that translanguaging supports the reading abilities of deaf students, Swanwick et al. (2022) averred that implementing translanguaging in the education process for deaf students may foster inclusivity and expand the communication potentials significantly by exposing deaf students to complex linguistic repertoires. Despite the long existence of the application of translanguaging on the linguistic repertoires of the non- deaf populace, the application of translanguaging in the education of deaf people seems only to have started gaining research interest in recent times.

Some scholars have therefore suggested the need for a deeper exploration and investigation of the concept of translanguaging as well as the effect of translanguaging on the linguistic competence and educational outcomes of deaf students (Canagarajah, 2011; Chaka, 2020; De Meulder et al., 2019; McGovern, 2023). This study was thus undertaken to determine the extent of research on the implications of translanguaging in the education of deaf students and to cumulatively establish the effects of translanguaging on the learning outcomes of deaf students. We (Authors) believe that the outcome of this systematic review will reveal the gaps in previous research that has been conducted on translanguaging among deaf students. Subsequently, findings from this study will guide future empirical research on the effects of translanguaging on the academic outcomes of deaf students with a view of providing research direction for scholars in deaf education and deaf studies on the implication of translanguaging in deaf education.

Materials and methods

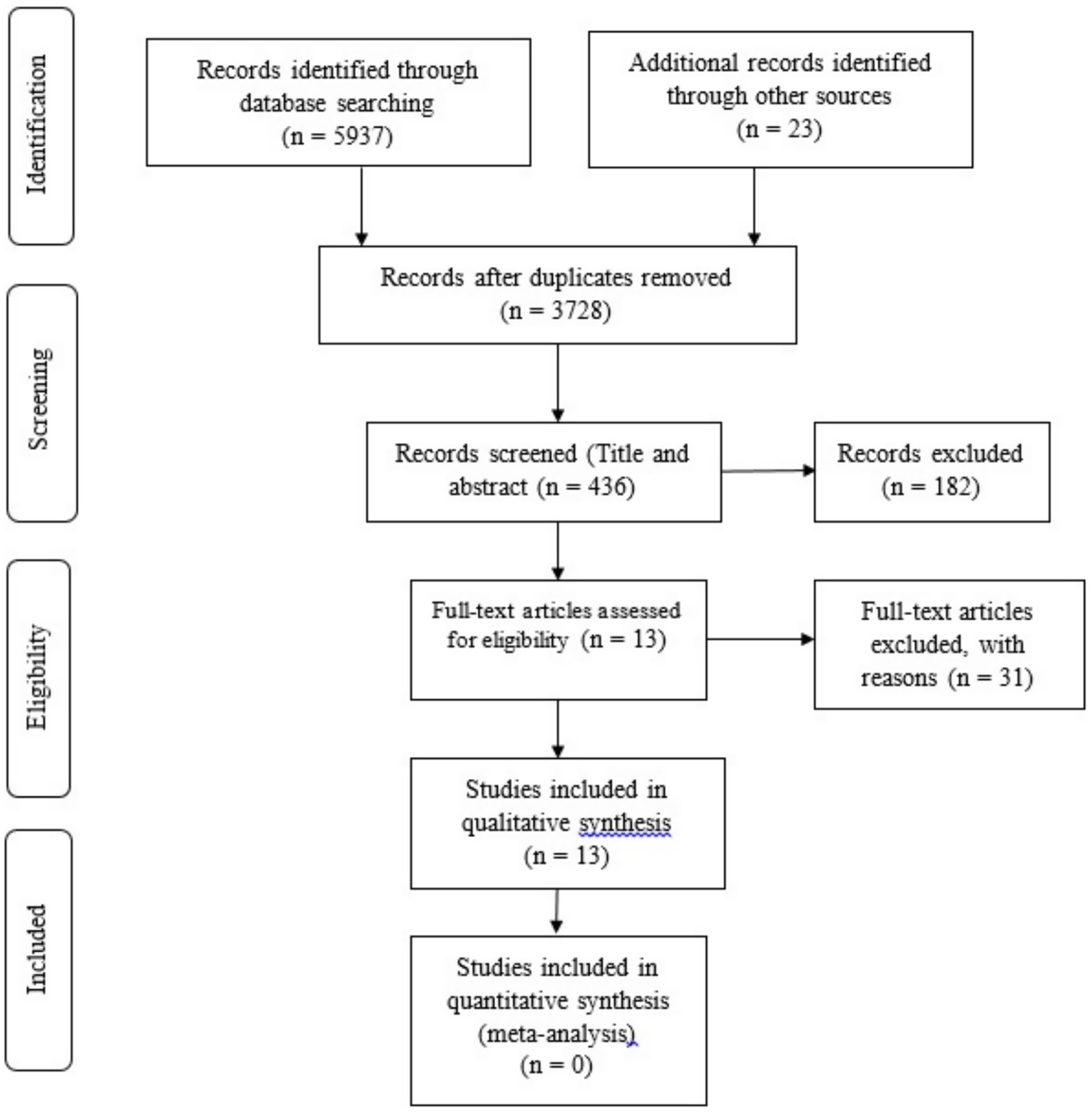

We carefully adopted the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting of Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement (Doo et al., 2023; Moher et al., 2009) for the conduct of systematic reviews in this study which determined the implication of translanguaging on the linguistic competencies of deaf students. The PRISMA guideline is a set of 27-item checklist that ensures transparency and completeness of reportage of existing studies for the completion of both systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Moher et al., 2009). For the propose of transparency and reproducibility, Vrabel (2009) affirmed that the flow diagram based on the PRISMA guideline helps readers to assess the trustworthiness and applicability of the review’s conclusions. Above all, the PRISMA guideline ensures or provide clear understanding of why the review was conducted, what methods were used, and what results were found.

The study purposively selected relevant studies that were published between January 2012 and June 2023. As indicated by Doo et al. (2023), the processes followed in this study were as follows: (i) identification of the research problems; (ii) search for and collection of relevant and eligible existing studies; (iii) evaluation of the data (from existing studies) in order to harvest relevant studies; (iv) analysis and synthesis of existing studies for data collection; and (v) presentation of the findings. A critical appraisal of the study was ensured as espoused by Burls (2014) and Katrak et al. (2004). Further in the process of critical appraisal, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklists (Aromataris et al., 2020) were used to guide the process in the review. The JBI critical appraisal checklists is a tool designed to assess the methodological quality and risk of bias in various types of published research studies to ascertain its trustworthiness, relevance and results for the conduct of systematic reviews (Hilton, 2024). Thus, through processes of critical appraisal, the trustworthiness (Gunawan, 2015; Polit and Beck, 2014) were assessed and established. According to Polit and Beck (2014) trustworthiness is a study rigor that is used to describe the (i) degree of confidence in data, (ii) interpretation, and (iii) methods used to ensure the quality of a study.

Data sources and search strategies

The relevant existing research studies on translanguaging and deaf education/deaf learners were accessed in various bibliographic databases. These databases included the African Journals Online, Annual Reviews, Ebscohost, Emerald, Google Scholar, JSTOR, Project Muse, PubMed, Research4life, and Scopus. Keywords (translanguaging and deaf education) were selected to capture adequately all the existing research studies on translanguaging in deaf education between January 2012 and June 2023. The search was thus conducted using “translanguaging” and “deaf education” as keywords and we also searched for article titles and abstracts containing the terms, “translanguage*” or “translanguaging” AND “deaf education” or “deaf learn*” or “deaf student*” or “deaf school.” As shown in Figure 1, the search strategy used in the study was also based on the exclusion–inclusion criteria indicated in Table 1.

Data extraction and analysis

The authors of this study independently assessed and extracted relevant information from the identified and selected research studies on translanguaging in deaf education. Based on the keywords identified for search of various data bases for the purpose of this study, a total of 5,937 published documents of translanguaging was found. We double checked the references of the earlier found documents for possible research document we could not find in our previous search and during the process, another 23 relevant published documents on variable of interest were found. Further, we were about to sort for duplication of published documents in our earlier searches. We removed a total of 3,728 duplicates. We further screened the remaining 2,232 documents for titles and abstract that are relevant to the study. We found only 436 publications to be relevant to this study based on their titles and abstracts. Out of the 436 publications, a total of 182 documents were further removed because they were not empirical based research on issues of tranlanguaging in deaf education. We further screened the remaining 254 document for either open or closed access publications, this process left us with just 44 publications out of which only 13 met the inclusion criteria set for the study.

The data generated by each of the authors was tabulated and later cross-checked and merged following a conference by the authors. The data was gathered and merged based on the objective of the study. The authors sought the assistance of an independent assessor (a linguist) to cross-check the data input and this further ensured the validity of the information gathered and inserted into each column. The independent assessor provided constructive criticism of the data extracted from all of the studies identified and we made some changes to the extracted data based on his suggestions.

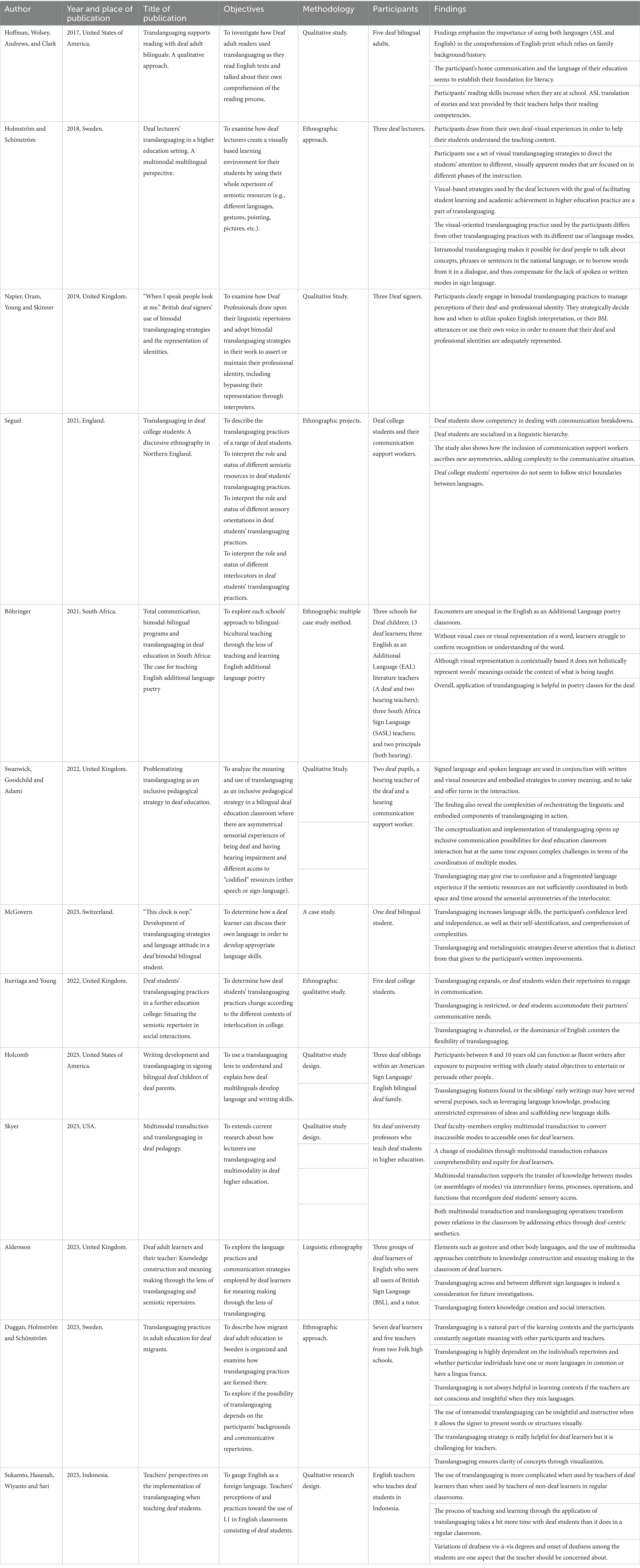

A seven-column table (Table 2) was created in order to synthezise and synchronize the existing issues on translanguaging in deaf education. This seven-column table was used to collate the extracted data from the existing studies, and the data was later synthesized to provide further undestanding on the implications of translanguaging for the learning outcomes of deaf students. The columns in Table 2 contain information regarding the names of the authors of the studies utilized; the year of publication and country where the studies were done; the titles of the peer reviewed articles; whether the research was a journal article or a thesis; the study design adopted in the identified studies; the participants; the objectives of the study; and the findings of the studies.

Results

In the decade of research on translanguaging (January, 2012–June, 2023) among deaf people that this study examined, five of the studies on translanguaging among the deaf was found to have emanated from the United Kingdom; three emanated from the United States of America; two emanated from Sweden; and one study each emanated from Indonesia and South Africa, respectively. As revealed in Table 2, out of the 13 studies extracted and assessed for the implication of translanguaging in education of deaf students, six of the articles extracted for this study were published in 2023, two each were published in 2021 and 2022, respectively, while other were found to be published in 2017, 2018 and 2019, respectively. Studies of Aldersson (2023), Böhringer (2021), Holmström and Schönström (2018), Iturriaga and Young (2022), Seguel (2021), and Duggan et al. (2023) adopted ethnographic approach for data collection in their study while Hoffman et al. (2017), Holcomb (2023), Napier et al. (2019), Skyer (2023), Swanwick et al. (2022), and Sukamto et al. (2023) employed the qualitative research design for collection of data for their studies. Only the study of McGovern (2023) employed a case study approach for his study.

A total of eight studies out of the 13 studies identified and analysed in this current study, had solely deaf individuals who participated in their studies (Aldersson, 2023; Hoffman et al., 2017; Holcomb, 2023; Holmström and Schönström, 2018; Iturriaga and Young, 2022; McGovern, 2023; Napier et al., 2019; Skyer, 2023) with varying evidence on the implications of translanguaging on both academic outcomes and linguistic competencies and performance of the deaf. Other studies collected data from a combination of the deaf individual and non-deaf individuals whose profession includes school principals, teachers, and communication workers (Böhringer, 2021; Duggan et al., 2023; Seguel, 2021; Sukamto et al., 2023; Swanwick et al., 2022).

The textual analysis of the 13 studies on translanguaging among school-going deaf people was grouped into three themes as follows:

Theme 1: translanguaging as an inclusive fulcrum

Several of the existing studies on the issues of translanguaging within the context of the education of Deaf students indicated that the pedagogical approach of translanguaging fosters the principle of inclusive philosophy. As shown in Table 2, existing studies echoed that the use of translanguaging promotes social interaction between Deaf students and their non- Deaf peers (Aldersson, 2023; Böhringer, 2021; Duggan et al., 2023; Hoffman et al., 2017; Iturriaga and Young, 2022; Skyer, 2023; Swanwick et al., 2022). Aldersson (2023), Böhringer (2021), and Skyer (2023) noted that Deaf students have the capacity to engage in communication with their peers following efficient implementation of translanguaging. Böhringer (2021) specifically observed that Deaf students in poetry classrooms can communicate with their non- Deaf peers as equals after being taken through the process of translanguaging. Findings synthesised from the study of Böhringer (2021) was achieved through a qualitative- ethnographic study of Deaf students from three different South African Deaf school that employs bilingual-bicultural teaching approach for the teaching and learning of English language poetry. Böhringer (2021) gathered relevant data via observations, note-taking and semi-structured interviews with Deaf learners in their poetry classrooms, supporting staff members and teachers during poetry classes. Böhringer (2021) acknowledged diverse teaching and learning experiences regarding individual cognitive schema, experiences, social interactions, and textual cues but the use of translanguaging was sufficient to create inclusive learning experience by creating a text world relevant to the time and space of the learners. Above all, Böhringer (2021) assert that translanguaging could eliminate critical complexity inherent in English poetry classroom.

Aldersson (2023) and Skyer (2023) submitted that translanguaging fosters knowledge creation and social interaction and enhances comprehensibility and equity for Deaf students. Aldersson’s study involved six-week lessons with three groups of Deaf adult learners aged 20–50 (Aldersson, 2023). During the six-week interactions with the Aldersson (2023) gathered relevant data from the study participants using lesson plans, reflective notes and video-recorded observations which aided triangulation of data collected. Over the 6 weeks, 10 activities in British Sign Language (visual modality) and English (manually-encoded modality and written modality) were video recorded from different angles of the classroom to capture both the participants and instructor. Aldersson adopted the use of thematic analysis and annotations to analyse data gathered through the lesson plans/reflective notes over the six-week period while ELAN3 was used to analyse video recorded sign language data (Aldersson, 2023). While the study of Aldersson (2023) on translanguaging is said to foster knowledge creation and social interaction and enhances comprehensibility and equity for Deaf students, the study furthers the incorporation of signed and written modalities which involved manually-coded English systems that can advance a dynamic communicative environment in a manner that foster inclusivity.

Inference synthesised from the study of Skyer (2023) on translanguaging among the Deaf points to the fact that translanguaging enhances knowledge creation and social interaction and enhances comprehensibility and equity for Deaf students. The study of Skyer (2023) which had period of six faculty members and some Deaf students who were ASL–English bilinguals in a University in the United States over a period of 3 years was based observation and theorization of Deaf pedagogic interactions by identifying visual pedagogic theories, tools, and methods. As against visual modality, Skyer (2023) adopted the multimodal theories of education to frame his study on “Multimodal Transduction and Translanguaging in Deaf Pedagogy.” While Skyer (2023) ensured triangulation of data gathered through observations of Deaf faculty teaching Deaf students in STEM disciplines and in the Humanities fields, document analysis, interviews with Deaf faculty about pedagogic processes and, stimulated recall. Findings obtained after data analysis by Skyer (2023) revealed that the use of multimodal transduction and translanguaging provides accessibilities to difficult pedagogical concepts and thereby enhance epistemological equity and comprehensibility of concepts by all students. In other words, application of translanguaging through multimodal transduction transform power relations in the classroom due its power of adaptiveness and flexibility (Skyer, 2023). In view of the findings obtained by this study, it was observed that the concept of translanguaging can serve to foster further social inclusion and socio/interpersonal relationships between Deaf people and the non-Deaf members of the society. Deaf people can make their intentions clear through the application and use of translanguaging and the rich repertoire of language enrichments. They can express themselves to non- Deaf people, thereby creating easy access into the entire fabric of the community.

Theme 2: multi-modal approach as a driver of translanguaging

Translanguaging is a concept or pedagogical approach to improve the linguistic repertoire of Deaf student and can be influenced by various factors (Liu and Fang, 2022). In other words, the combined use of several teaching methodologies strengthens the concept of translanguaging. Translanguaging consists of a complex use of combinations of gestures, visual cues and other body language, transitional forms, processes, operations, and functions, as well as multimedia approaches together with the use of sign language to create knowledge and construct meanings (Aldersson, 2023; Böhringer, 2021; Duggan et al., 2023; Holmström and Schönström, 2018; Napier et al., 2019; Skyer, 2023; Sukamto et al., 2023; Swanwick et al., 2022). While Napier et al. (2019) described the foregoing as a bimodal process, Holmström and Schönström (2018) and Skyer (2023) averred that the process of translanguaging is multimodal in nature. The basis of the “bimodal” nature of translanguaging as found by Napier et al. (2019) was because of findings obtained from a research engagement with three British adult-Deaf signers (two females and one male) who adopted bimodal translanguaging strategies. Data obtained in the study of Napier et al. (2019) through interviews which were thematically analysed draws upon respondents’ linguistic repertoires and how they were able to bypass their representation through Sign language interpreters. Expressively the three interviewees were found to engage in bimodal translanguaging practices. However, three British adult-Deaf signers felt that their bimodal translanguaging process was less accepted because people sometime fail to understand and approve of its usage. Therefore, implication of the findings of Napier et al. (2019) advanced the need to draw upon multimodal repertoires to extend the understanding of the nexus between language use, personal and social identities, as well as representation.

The implication of the multimodal process of translanguaging as advanced by Napier et al. (2019), provided support for the assertions of Archer (2006) and Li (2014) who posit that the multimodality process in translanguaging has positive implication for pedagogical and social communication approach. Thus, multimodality in translanguaging process accounts for the multiplicity of modes of meaning-making with links between shifting globalization, re-localization, semiotic landscapes, the and identity formation (Archer, 2006; Napier et al., 2019). Interestingly, the studies of Holmström and Schönström (2018) and Skyer (2023) further expand the concept of multimodal approach as a driver of translanguaging. In their ethnographical study which had three Deaf lecturers, Deaf and hearing (signing) students in a higher education setting in Sweden, their analysis video-recorded data showed how Deaf lecturers taught using multimodal approach by creatively using several semiotic resources4 (Swedish sign language and American sign language, PowerPoint and whiteboard notes and other communication strategies) to teach Deaf and hearing (signing) students. Overall, Holmström and Schönström (2018) and Skyer (2023) illustrated that multimodal process of translanguaging provide the Deaf the opportunity the use diverse and interconnectedness processes of concept, phrase, or sentences to ensure meaningful dialogues. In other words, multimodal process of translanguaging words, helps Deaf people to compensate for spoken and written language challenges (Holmström and Schönström, 2018; Skyer, 2023). The synthesis of evidence therefore showed that through multimodal process, translanguaging is a complex process through which Deaf people strategically decide and manage their Deaf identity. While various studies recognized many positives associated with translanguaging, Swanwick et al. (2022) remarked that translanguaging exposes complex challenges in terms of the co-ordination of multiple modes for both the teacher and Deaf students.

Theme 3: language competency through translanguaging

Building the linguistic repository or repertoire and language competence of Deaf students is one of the goals of translanguaging within the classroom. Existing studies on translanguaging among the Deaf have established an improvement in the linguistic repertoires of Deaf students after exposure to translanguaging (Holcomb, 2023; Iturriaga, 2022; McGovern, 2023; Seguel, 2021; Skyer, 2023). The ethnographic study by Seguel (2021) among some Deaf students in England revealed that the students showed increased language competencies after exposure to translanguaging. However, despite the recorded improvement in language competencies, as well as a rise in independence and confidence levels of Deaf people (Holcomb, 2023; McGovern, 2023; Iturriaga, 2022; Skyer, 2023). Seguel (2021) noted that the Deaf students who participated in his studies were not following the strict rules of language adequately during communication activities. In his ethnographic study of five Deaf college students in Northern England which aimed to analyse translanguaging practices, Seguel (2021) collected relevant data using analytical memos, field notes, interviews, language portraits, photos, and reflective journal entries. A qualitative analysis of various data collected from the participants led to the conclusion that semiotic repertoires is an emergent dynamic property of shared communication spaces. In other words, the richness of semiotic repertoires is important to the use of translanguaging for the Deaf but differential in shared hearing peers. The differences in richness of semiotic repertoires between Deaf learners and non-Deaf peers is largely due to differential sensory orientation complexities which reflect in dialogical learning opportunities and outcomes.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine the extent of the research between January, 2012 and June, 2023 on the implications of translanguaging in the education of deaf students and to cumulatively establish the effects of translanguaging on the learning outcomes of deaf students. It has been documented in existing literature that translanguaging is a concept and construct which could influence the linguistic development of deaf students. Thirteen existing studies on translanguaging in deaf education met the inclusion criteria. Finding based on the origin of the identified studies highlight the advances in research activities that centers on deaf education in the developed countries based on the fact that 11 of the identified studies were from United Kingdom, United States of America, and Sweden based researchers. The output of studies on tranlanguaging in deaf education as found in developed countries of Europe and America further reinforced historic development of deaf education in Europe and the Unites States of America as indicated in the studies of Marschark et al. (2007), Marschark and Knoors (2012), and Richardson et al. (2010). Although, a study on tranlanguaging in deaf education was identified from South Africa, but it may be said that such singular evidence of translanguaging in deaf education on the continent of Africa is not enough and it should be a source of concern to researchers and other relevant stakeholders in deaf education. It seems unspeakable that despite the fact that Africa has the largest population of deaf people (Adigun, 2019; Adigun and Nzima, 2021; Kiyaga and Moores, 2003; WHO, 2017) whose language abilities and linguistic repertoires fall below the expected threshold when compared with their non- deaf counterparts, there is almost no research output on the implication of translanguaging on learning outcomes of her deaf students.

It is noteworthy to acknowledged that there is plethora of research evidence on linguistic capacities and academic outcomes of deaf students from Africa which have established the implication of diverse factors that may account for variations in linguistic repertoires (Adigun et al., 2021; Böhringer, 2021; Matende et al., 2021; Ngobeni et al., 2020; Obosu et al., 2023). However, application of translanguaging as a catalyst for the improvement of linguistic competencies of deaf students is yet to be prioritized in the education of the deaf people particularly in Africa as it is observed in the studies of Aldersson (2023), Duggan et al. (2023), Hoffman et al. (2017), Holcomb (2023), Holmström and Schönström (2018), Iturriaga and Young (2022), Napier et al. (2019), Seguel (2021), Skyer (2023), and Swanwick et al. (2022). Evidence from the identified studies have shown that despite language and cultural diversity, translanguaging may foster language acquisition and promote interactive learning among deaf students. Since 2004, Kaniei had indicated that variations exist in the sign languages and there is vast diversity in the syntax, morpheme, and structure of sign language for communication among deaf people. As a result, there is untapped translanguaging research potential among the deaf community, particularly those from the Sub-Saharan African nations. Lamentably, only one dissertation on translanguaging among the deaf was found to have emanated from Sub-Saharan Africa (Böhringer, 2021).

Cumulative finding on the implication of translanguaging among deaf students showed that translanguaging could foster philosophy of inclusive education (Aldersson, 2023; Böhringer, 2021; Duggan et al., 2023; Hoffman et al., 2017; Iturriaga and Young, 2022; Seguel, 2021; Skyer, 2023; Swanwick et al., 2022). Inclusive education is conceptualized as an educational approach that places an emphasis on non-discrimination and the full participation of all students in education processes in a manner that promotes the prevention of conditions that lead to exclusion (Adigun et al., 2021). Interestingly, some previous studies have expressed concerns about the place of the language ability of deaf students within the inclusive classroom (Alasim, 2019; Goico, 2019; Glaser and Van Pletzen, 2012; Hoffman et al., 2017; Swanwick et al., 2022). In other words, the ability of deaf people to engage in irresistive interpersonal communication using the concepts of translanguaging could promote social inclusion, enhanced psychosocial wellbeing and improved learning outcome. Such ability may build capacities deaf student to favorably compete among other students and peers.

Several existing studies have expressed concern about the implication of language delay and language deprivation among deaf students (Böhringer, 2021; Cawthon, 2001; Marschark et al., 2007; Ngobeni et al., 2020; Obosu et al., 2023). Lamentably, the negative effect of delay in language of deaf students and difficulties at using appropriate communication processes is evident in the poor academic outcomes recorded. An earlier study by Savage-Rumbaugh et al. (1986) has long advocated for strategies to improve language competencies of the deaf child. Thus, recent research evidence has revealed the potential efficacy of translanguaging in deaf classrooms. As presented by Aldersson (2023), Böhringer (2021), Duggan et al. (2023), Hoffman et al. (2017), Iturriaga and Young (2022), Seguel (2021), Skyer (2023), and Swanwick et al. (2022), translanguaging has capacity to advance inclusion of deaf student into the mainstream society. Based on the available evidence, translanguaging may adequately foster deaf students’ acceptance, belongingness and promote values through effective interpersonal communication for the development of positive academic outcomes.

Further, this study found that translanguaging extols the principles of multimodal teaching strategies (Aldersson, 2023; Böhringer, 2021; Duggan et al., 2023; Holmström and Schönström, 2018; Napier et al., 2019; Skyer, 2023; Sukamto et al., 2023; Swanwick et al., 2022); and (iii) translanguaging has great potential to improve the language competency of deaf people (Duggan et al., 2023; Hoffman et al., 2017; Holcomb, 2023; Iturriaga and Young, 2022; McGovern, 2023; Seguel, 2021; Skyer, 2023). A multimodal teaching strategy is an approach where teachers use several modes and ideas in multiple ways to explain a concept. The implementation of a multimodal approach in translanguaging, established as necessary in this study, strengthens the earlier reports by Allen and Morere (2020), Almumen (2023), Jessica and Cohen (2023), Kusters et al. (2017), Wolbers et al. (2023), and Wolsey et al. (2018). These researchers reported that a multimodal approach is effective in building the linguistic repertoires and improving the academic outcomes of deaf students.

Building the linguistic repository or repertoire and language competence of deaf students is one of the goals of translanguaging within the classroom. Existing studies on translanguaging in deaf education have established an improvement in the linguistic repertoires of deaf students after exposure to translanguaging (Duggan et al., 2023; Hoffman et al., 2017; Holcomb, 2023; Iturriaga and Young, 2022; McGovern, 2023; Seguel, 2021; Skyer, 2023). For more than a decade, mainstream studies on translanguaging confirmed the potency of translanguaging on the linguistic competencies of students in relation to their academic outcome (Canagarajah, 2011; Catherine, 2017; Chaka, 2020; Garcia, 2014; Liu and Fang, 2022; Mendoza, 2020). According to Garcia (2014), Chaka (2020) as well as Liu and Fang (2022) the application of translanguaging provides an individual with the flexibility required to effectively exchange communication and use of their complex linguistic potentials to have meaningful interpersonal conversation. In other words, translanguaging may provide ample opportunities for deaf students on the choice of vocabulary and manner of expression based on content and interpretations of languages (Holmström and Schönström, 2018; Mendoza, 2020). The foregoing therefore implies that translanguaging may provide deaf students the opportunities to shuttle between languages, signs and symbols from their repertoire as an integrated language system, linguistic repertoires (spoken and written) and semiotic resources (Aldersson, 2023; Mendoza, 2020; Musyoka, 2023; Wolbers et al., 2023). From the existing evidence, translanguaging is a paradigm shift that provides advanced opportunities for an accessible and inclusive education where students’ diversity is equally valued. Therefore, a transformative pedagogical strategy that offers possibilities for advancing the learning outcomes of deaf students should be considered in language development of deaf people.

Conclusion

This study raised awareness for researchers of the implications of translanguaging among the deaf by looking at studies that were conducted on this pedagogical practice between 2012 and 2022. Analysis of the 13 articles reviewed in this study provided a comprehensive understanding of the possible implications of translanguaging, as well as the potential opportunities that translanguaging may present for the social and academic inclusion of deaf people. In essence, this study can conveniently conclude that translanguaging fosters inclusivity and development of linguistic competencies among the deaf through a multimodal approach strategy. Moreover, this systematic review of existing literature established that there is almost no research effort by African scholars to assess the impact of translanguaging on the linguistic repertoires of deaf students for active academic, social and interpersonal engagements. Lack of substantive research evidence on the implication of translanguaging among Deaf students in Africa could be due to the significant socio-cultural and language diversity of the average classroom in almost all countries of Sub-Saharan Africa and/or perhaps, such paucity of research evidence could be due to existential financial crisis.

Limitations of the study

Empirical studies on translanguaging among deaf students were considered for analysis in this study. Unfortunately, only 13 suitable studies were found and analyzed and had their findings presented. While our study had considered only articles on translanguaing in deaf education which were published in English Language, we acknowledged our limitation at assessing and analyzing studies of similar nature that have been published in other languages with regards to the keywords used in this study. We did not consider opinion/theoretical articles on issues of translanguaging among deaf people in this study. There are currently no existing studies that analyzed quantitative data nor any cross-sectional studies on issues of translanguaging among deaf people. Hence, we admit that generalization of the findings of the existing studies should be implemented carefully and mindfully.

Implications and recommendations for research, policies, and practice

The use of language transcends interactive purposes. Language is crucial for self-identity and cultural awareness and addressing the issue of language competency among deaf students will go a long way to further improve their psychosocial wellbeing. In other words, increases in deaf people’s linguistic repertoires could promote the philosophy of inclusive education. This study therefore notes the importance of extensive research studies to examine the implications of translanguaging among deaf people in various institutions of higher learning. A collaborative cross-sectional study may provide an extensive understanding of the role of translanguaging in personal adjustment, written and spoken language skills, and the social inclusion of deaf people. Such research efforts may improve the enactment of language policies in schools for the benefit of deaf students, as earlier described in the study by Musyoka (2023). Such policy formulation and implementation can only be successful when generalization of the findings on translanguaging is achieved. Training institutions for teachers of deaf students may consider the inclusion of the concept of translanguaging, not only in the training of teachers of deaf students, but in all teacher training and retraining programs. Raising the general public’s awareness about deafness and the related struggles could also assist in the achievement of social inclusion and application of translanguaging for enhance linguistic competencies of deaf students.

Author contributions

OA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^This is the education of deaf students through oral language by using lip reading, speech, and mimicking the mouth shapes and breathing patterns of speech.

2. ^A system of communication using visual gestures, fingerspelling and signs, as used by deaf people.

3. ^A multi-media annotation software that was designed for the creation of time-aligned text annotations to audio and video files.

4. ^Semiotic resources can be described as actions, artifacts, and materials that are used to achieve effective communication.

References

Adigun, O. T. (2019). Burnout and sign language interpreters in Africa. J. Gend. Inf. Dev. Afr. 8, 91–109. doi: 10.31920/2050-4284/2019/8n3a5

Adigun, O. T., and Ajayi, E. O. (2015). Teacher’s perception of the writing skills of deaf/hard of hearing students in Oyo state, Nigeria. Int. J. Educ. Found. Manag. 9, 212–222. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290441918_Teachers’_Perception_of_the_Writing_Skills_of_DeafHard_of_Hearing_Students_in_Oyo_State_Nigeria (Accessed January 23, 2024).

Adigun, O. T., Akinrinoye, O., and Obilor, H. N. (2021). Including the excluded in antenatal care: a systematic review of concerns for D/deaf pregnant women. Behav. Sci. 11:67. doi: 10.3390/bs11050067

Adigun, O. T., and Nzima, D. R. (2021). The predictive influence of gender, onset of deafness and academic self-efficacy on attitude of deaf students towards biology. S. Afr. J. Educ. 41, 1–11. doi: 10.15700/saje.v41n2a1894

Adigun, O., Oyewumi, A., Mngomezulu, T., and Adekeye, B. (2024). Awareness and knowledge of congenital cytomegalovirus as an agent of hearing loss: a descriptive evidence from Nigeria. Open J. Public Health. 17:e18749445305521. doi: 10.2174/0118749445305521240516051327

Alasim, K. N. (2019). Reading development of students who are deaf and hard of hearing in inclusive education classrooms. Educ. Sci. 9:201. doi: 10.3390/educsci9030201

Aldersson, R. (2023). Deaf adult learners and their teacher: knowledge construction and meaning-making through the lens of translanguaging and semiotic repertoires. DELTA (São Paulo). 39:202359756. doi: 10.1590/1678-460x202359756

Allen, T. E., and Morere, D. A. (2020). Early visual language skills affect the trajectory of literacy gains over a three-year period of time for preschool aged deaf children who experience signing in the home. PLoS One 15:e0229591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229591

Almumen, H. (2023). Technology and multimodality in teaching pre-service teachers: fulfilling diverse learners’ needs. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 28, 745–767. doi: 10.1007/s10758-021-09550-1

Alothman, A. A. (2021). Language and literacy of deaf children. Psychol. Educ. J. 58, 799–819. doi: 10.17762/pae.v58i1.832

Archer, A. (2006). A multimodal approach to academic ‘literacies’: problematising the visual/verbal divide. Lang. Educ. 20, 449–462. doi: 10.2167/le677.0

Aromataris, E., Fernandez, R., Godfrey, C., Holly, C., Khalil, H., and Tungpunkom, P. (2020). Chapter 10: umbrella reviews. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI, 5.

Böhringer, C. R. (2021). Total communication, bimodal-bilingual programs and translanguaging in deaf education in South Africa: the case for teaching English additional language poetry (doctoral dissertation). Johannesburg: School of Education, Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand. Available at: https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/bitstreams/1a5f5611-a103-4ee6-8887-87914965cf14/download

Canagarajah, S. (2011). Codemeshing in academic writing: identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. Mod. Lang. J. 95, 401–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01207.x

Catherine, M. (2017). “Theorizing translanguaging practices in higher education” in Translanguaging in higher education: Beyond monolingual ideologies. eds. M. Catherine and C. Kevin (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 1–10.

Cawthon, S. W. (2001). Teaching strategies in inclusive classrooms with deaf students. J. Deaf. Stud. Deaf. Educ. 6, 212–225. doi: 10.1093/deafed/6.3.212

Chaka, C. (2020). Translanguaging, decoloniality, and the global south: an integrative review study. Scrutiny2 25, 6–42. doi: 10.1080/18125441.2020.1802617

De Meulder, M., Kusters, A., Moriarty, E., and Murray, J. J. (2019). Describe, don't prescribe. The practice and politics of translanguaging in the context of deaf signers. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 40, 892–906. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2019.1592181

Doo, M. Y., Zhu, M., and Bonk, C. J. (2023). A systematic review of research topics in online learning during COVID-19: documenting the sudden shift. Online Learn. 27, 15–45. doi: 10.24059/olj.v27i1.3405

Dostal, H. M., and Wolbers, K. A. (2014). Developing language and writing skills of deaf and hard of hearing students: a simultaneous approach. Literacy Res. Instr. 53, 245–268. doi: 10.1080/19388071.2014.907382

Duggan, N., Holmström, I., and Schönström, K. (2023). Translanguaging practices in adult education for deaf migrants. Delta 39:202359764. doi: 10.1590/1678-460x202359764

Garcia, O. (2014). “Countering the dual: Transglossia, dynamic bilingualism and translanguaging in education” in The global-local interface, language choice and hybridity. eds. R. Rubdy and L. Alsagoff (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 100–118.

García, O., and Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Glaser, M., and Van Pletzen, E. (2012). Inclusive education for deaf students: literacy practices and south African sign language. South. Afr. Linguist. Appl. Lang. Stud. 30, 25–37. doi: 10.2989/16073614.2012.693707

Goico, S. A. (2019). The impact of “inclusive” education on the language of deaf youth in Iquitos, Peru. Sign Lang. Stud. 19, 348–374. doi: 10.1353/sls.2019.0001

Gunawan, J. (2015). Ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research. Belitung Nurs. J. 1, 10–11. doi: 10.33546/bnj.4

Hilton, M. (2024). JBI critical appraisal checklist for systematic reviews and research syntheses (product review). J. Can. Health Libr. Assoc. 45:29801. doi: 10.29173/jchla29801

Hoffman, D., Wolsey, J. L., Andrews, J., and Clark, D. (2017). Translanguaging supports reading with deaf adult bilinguals: a qualitative approach. Qual. Rep. 22, 1925–1944. Retrieved from: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol22/iss7/12

Hoffmeister, R., Henner, J., Caldwell-Harris, C., and Novogrodsky, R. (2022). Deaf children’s ASL vocabulary and ASL syntax knowledge supports English knowledge. J. Deaf. Stud. Deaf. Educ. 27, 37–47. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enab032

Holcomb, L. (2023). Writing development and translanguaging in signing bilingual deaf children of deaf parents. Language 8:37. doi: 10.3390/languages8010037

Holmström, I., and Schönström, K. (2018). Deaf lecturers’ translanguaging in a higher education setting. A multimodal multilingual perspective. Appl. Ling. Rev. 9, 89–111. doi: 10.1515/applirev-2017-0078

Howerton-Fox, A., and Falk, J. L. (2019). Deaf children as ‘English learners’: the psycholinguistic turn in deaf education. Educ. Sci. 9:133. doi: 10.3390/educsci9020133

Hrastinski, I., and Wilbur, R. B. (2016). Academic achievement of deaf and hard of hearing students in an ASL/English bilingual program. J. Deaf. Stud. Deaf. Educ. 21, 156–170. doi: 10.1093/deafed/env072

Humphries, T., Kushalnagar, P., Mathur, G., Napoli, D. J., Padden, C., Rathmann, C., et al. (2016). Avoiding linguistic neglect of deaf children. Soc. Serv. Rev. 90, 589–619. doi: 10.1086/689543

Iturriaga, C. S. (2022). Translanguaging in deaf college students: A discursive ethnography in northern England (Doctoral dissertation). Manchester: University of Manchester.

Iturriaga, C., and Young, A. (2022). Deaf students’ translanguaging practices in a further education college: situating the semiotic repertoire in social interactions. J. Deaf. Stud. Deaf. Educ. 27, 101–111. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enab033

Kaniei, N. (2004). The sign languages of Africa. J. Afr. Stu. 64, 43–64. doi: 10.11619/africa1964.2004.43

Katrak, P., Bialocerkowski, A. E., Massy-Westropp, N., Kumar, V. S., and Grimmer, K. A. (2004). A systematic review of the content of critical appraisal tools. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 4, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-4-22

Kiyaga, N. B., and Moores, D. F. (2003). Deafness in sub-saharan Africa. Am. Ann. Deaf 148, 18–24. doi: 10.1353/aad.2003.0004

Kumatongo, B., and Muzata, K. K. (2021). Barriers and facilitators to academic performance of learners with hearing impairments in Zambia: a review of literature. J. Educ. Res. Child. Parents 2, 169–189. Available online at: https://ercptjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/JERCPT-002.pdf

Kusters, A., Spotti, M., Swanwick, R., and Tapio, E. (2017). Beyond languages, beyond modalities: transforming the study of semiotic repertoires. Int. J. Multiling. 14, 219–232. doi: 10.1080/14790718.2017.1321651

Li, W. (2014). Translanguaging knowledge and identity in complementary classrooms for multilingual minority ethnic children. Classroom Discourse 5, 158–175. doi: 10.1080/19463014.2014.893896

Lindberg, H. (2021). “National Belonging through Signed and spoken languages: the case of Finland-Swedish deaf people in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries” in Lived, Nation as the History of Experiences and Emotions in Finland, 1800–2000. eds. V. Kivimäki, S. Suodenjoki, and T. Vahtikari (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 217–239.

Liu, Y., and Fang, F. (2022). Translanguaging theory and practice: how stakeholders perceive translanguaging as a practical theory of language. RELC J. 53, 391–399. doi: 10.1177/0033688220939222

Marschark, M., Convertino, C. M., Macias, G., Monikowski, C. M., Sapere, P., and Seewagen, R. (2007). Understanding communication among deaf students who sign and speak: a trivial pursuit? Am. Ann. Deaf 152, 415–424. doi: 10.1353/aad.2008.0003

Marschark, M., and Knoors, H. (2012). Educating deaf children: language, cognition, and learning. Deafness Educ. Int. 14, 136–160. doi: 10.1179/1557069X12Y.0000000010

Matende, T., Sibanda, C., Chandavengerwa, N. M., and Sadiki, M. (2021). Critical language awareness in the education of students who are deaf in Zimbabwe. S. Afr. J. Afr. Lang. 41, 240–248. doi: 10.1080/02572117.2021.2010918

McGovern, R. (2023). “This clock is Oop” development of Translanguaging strategies and language attitude in a deaf bimodal bilingual student. Language 8:34. doi: 10.3390/languages8010034

Mendoza, A. (2020). What does translanguaging-for-equity really involve? An interactional analysis of a 9th grade English class. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 22, 1–21. doi: 10.1515/applirev-2019-0106

Miller, M. S., Moores, D. F., Andrews, J. F., and Wang, Q. (2020). Literacy and deaf education: Toward a global understanding. 1st Edn. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Musyoka, M. M. (2023). Translanguaging in bilingual deaf education teacher preparation programs. Language 8:65. doi: 10.3390/languages8010065

Napier, J., Oram, R., Young, A., and Skinner, R. (2019). “When I speak people look at me”: British deaf signers’ use of bimodal translanguaging strategies and the representation of identities. Transl. Translanguaging Multilingual Contexts 5, 95–120. doi: 10.1075/ttmc.00027.nap

Ngobeni, W. P., Maimane, J. R., and Rankhumise, M. P. (2020). The effect of limited sign language as barrier to teaching and learning among deaf learners in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Educ. 40, 1–7. doi: 10.15700/saje.v40n2a1735

Obosu, G. K., Vanderpuye, I., Opoku-Asare, N. A., and Adigun, T. O. (2023). A qualitative inquiry into the factors that influence deaf children's early sign language acquisition among deaf children in Ghana. Sign Lang. Stud. 23, 527–554. doi: 10.1353/sls.2023.a905538

Polit, D. F., and Beck, C. T. (2014). Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice. 8th Edn. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Richardson, J. T., Marschark, M., Sarchet, T., and Sapere, P. (2010). Deaf and hard-of-hearing students’ experiences in mainstream and separate postsecondary education. J. Deaf. Stud. Deaf. Educ. 15, 358–382. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enq030

Savage-Rumbaugh, S., McDonald, K., Sevcik, R. A., Hopkins, W. D., and Rubert, E. (1986). Spontaneous symbol acquisition and communicative use by pygmy chimpanzees (Pan paniscus). Journal of Experimental Psychology General 115, 211–235.

Scott, J., and Cohen, S. (2023). Multilingual, multimodal, and multidisciplinary: deaf students and translanguaging in content area classes. Language 8:55. doi: 10.3390/languages8010055

Seguel, C. I. (2021). Translanguaging in deaf college students: a discursive ethnography in northern England. Manchester: The University of Manchester (United Kingdom). Available online at: https://search.proquest.com/openview/22588d5076c7a57069cad694e335a858/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=51922&diss=y

Seltzer, K., and Collins, B. (2016). “Navigating turbulent waters: Translanguaging to support academic and socioemotional well-being” in Translanguaging with multi-lingual students: Learning from classroom moments. eds. O. Garcia and T. Kleyn (New York, NY: Routledge), 140–159.

Simpson, M. L., and Mayer, C. (2023). Spoken language bilingualism in the education of deaf learners. Am. Ann. Deaf 167, 727–744. doi: 10.1353/aad.2023.0009

Skyer, M. E. (2023). Multimodal transduction and translanguaging in deaf pedagogy. Language 8:127. doi: 10.3390/languages8020127

Sukamto, R. C. D., Hasanah, R. D. I., Wiyanto, U. V., and Sari, S. N. (2023). Teacher's perspective on the implementation of trans-languaging in teaching deaf students. KnE Soc. Sci. 27, 184–193. doi: 10.18502/kss.v8i7.13249

Swanwick, R., Goodchild, S., and Adami, E. (2022). Problematizing translanguaging as an inclusive pedagogical strategy in deaf education. Int. J. Bil. Educ. Bil. 27, 1271–1287. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2022.2078650

Villwock, A., Wilkinson, E., Piñar, P., and Morford, J. P. (2021). Language development in deaf bilinguals: deaf middle school students co-activate written English and American sign language during lexical processing. Cognition 211:104642. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2021.104642

Vrabel, M. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Rev. Esp. Nutr. Hum. Diet. 18:e123. doi: 10.1188/15.ONF.552-554

WHO. (2017). Prevention of deafness and hearing loss. Available online at: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA70/A70_R13-en.pdf (Accessed March 20, 2022).

Williams, C. (1996). Secondary education: teaching in the bilingual situation. Lang. Policy Taking stock 12, 193–211.

Wolbers, K., Holcomb, L., and Hamman-Ortiz, L. (2023). Translanguaging framework for deaf education. Language 8:59. doi: 10.3390/languages8010059

Wolsey, J.-L. A., Diane Clark, M., and Andrews, J. F. (2018). ASL and English bilingual shared book reading: an exploratory intervention for signing deaf children. Biling. Res. J. 41, 221–237. doi: 10.1080/15235882.2018.1481893

World Bank (2021). Population, total – Botswana. Available online at: data.worldbank.org (accessed March 24, 2022).

Wright, W. E., and Baker, C. (2017). Key concepts in bilingual education. Biling. Multilingual Educ., 65–79. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-02258-1_2

Keywords: translanguaging, deaf education, deaf students, linguistic competence, linguistic repertoire

Citation: Adigun OT, Mathosa M and Anyanwu CJ (2025) The implication of translanguaging on the linguistic competencies of deaf students. Front. Commun. 10:1515836. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1515836

Edited by:

Douglas Ashwell, Massey University Business School, New ZealandReviewed by:

Gabriel Simungala, University of Zambia, ZambiaDeden Novan Setiawan Nugraha, Universitas Widyatama, Indonesia

Ana Cecília Cossi Bizon, State University of Campinas, Brazil

Copyright © 2025 Adigun, Mathosa and Anyanwu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Olufemi Timothy Adigun, b2x1cGhlbW15NTRAeWFob28uY29t

Olufemi Timothy Adigun

Olufemi Timothy Adigun Mots’elisi Mathosa3

Mots’elisi Mathosa3