- School of Foreign Languages, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China

Introduction: This study investigates how Chinese newspapers frame the cultural practice of bride price (caili) and explores how such representations reflect broader socio-cultural tensions between tradition and modernity in contemporary China.

Methods: Using Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), 113 articles published between 2019 and 2023 are collected from 52 national and local newspapers. The analysis focuses on identifying thematic patterns and discursive strategies.

Results: The study identifies four dominant themes: (1) high bride price as a socio-economic burden, (2) changing social norms and modernizing marriage practices, (3) governmental interventions and policy reforms, and (4) interplay of gender dynamics. Newspapers predominantly frame high bride prices as detrimental to rural economic development while advocating for “zero bride price” and simplified marriages as markers of modernity and progress. Employing various legitimation strategies, particularly rationalization, moral evaluation, authorization, and mythopoesis, media discourse constructs bride price as a cultural practice requiring reform while acknowledging its traditional significance. Women are portrayed both as commodified objects and strategic agents, revealing ambivalence in gender representation.

Discussion: These competing narratives reflect broader societal negotiations between preserving cultural heritage and embracing modern values in Chinese society. By examining the discursive construction of bride price, this research provides insights into the media's role in shaping cultural practices and contributes to understanding how traditional customs are negotiated within modernizing societies.

1 Introduction

In contemporary China, the practice of bride price, where the groom's family gives money or goods to the bride's family (known as caili (彩礼)), persists despite significant social and economic modernization. This deeply ingrained custom has adapted through various historical periods, influenced by tradition, gender norms, and economic forces (To, 2015). While it symbolizes family honor and commitment, bride price has become increasingly controversial, igniting public debate as modern ideals clash with traditional expectations (Ji, 2015).

Despite the practice's cultural significance, research has largely overlooked how Chinese newspaper discourse frames bride price, particularly in terms of how women are portrayed at the intersection of tradition and modernity. Few studies have examined whether such media portrayals of bride price reinforce traditional patriarchal norms or instead challenge them by introducing modern, egalitarian perspectives on gender roles. This study addresses that gap by critically analyzing newspaper discourse on bride price through a gender lens, revealing how media narratives construct women's roles and identities while negotiating the tension between preserving cultural traditions and embracing social change in contemporary China.

Chinese newspapers, as influential shapers of public opinion, play a crucial role in constructing and disseminating views on bride price (Erigha, 2015; Foster et al., 2011). This study employs CDA to investigate how these newspapers portray bride price and how these representations reflect broader sociocultural tensions between tradition and modernity, as well as the evolving dynamics of gender relations in contemporary Chinese society.

The discourse on bride price is complex, intertwining economic, cultural, and gender factors. Economically, it is linked to rising housing prices and financial burdens on young men, especially in rural areas, where marriage costs can lead to significant debt (Wei and Zhang, 2011). Culturally, bride price reflects the intersection of traditional values about marriage and family honor with modern ideals of love, equality, and personal choice (Ruele, 2021). From a gender perspective, it is criticized for commodifying women and reinforcing patriarchal systems, while some scholars defend it as a valuable cultural tradition that strengthens social bonds and provides economic security for brides and their families (Jiang and Sánchez-Barricarte, 2012).

To comprehensively address this complex issue, this study poses the following research questions:

RQ1: How is the practice of bride price represented and framed in Chinese newspapers?

RQ2: What discursive strategies are employed to legitimize or critique the practice of bride price?

RQ3: How do Chinese newspaper representations of bride price portray women in relation to tradition and modernity, and thereby reinforce or challenge patriarchal norms?

By critically examining media discourse, this study provides insights into the ongoing negotiation between tradition and modernity, the evolving dynamics of gender relations, and the media's role in shaping cultural practices. It contributes to the growing body of literature on media representations of cultural practices in China (Sun and Zhao, 2009) and extends the application of CDA to non-Western contexts.

2 Theoretical framework and literature review

2.1 Critical discourse analysis and discursive strategies

This study employs CDA as its primary theoretical and methodological framework, viewing language as a social practice intertwined with power and ideology (Fairclough, 2003). Drawing on theorists like Foucault, Habermas, and Bourdieu, CDA emphasizes how discourse constructs social realities and reinforces power hierarchies (Meyer and Wodak, 2015). CDA's focus on power relations makes it particularly suitable for analyzing how bride price is framed in Chinese media.

This study specifically draws upon the discourse-historical approach (DHA) within CDA, as developed by Reisigl and Wodak (2000). DHA examines the historical and socio-political contexts in which discourses are embedded and operates on three analytical levels: (1) the macro-level of discourse topics/themes; (2) the meso-level of discursive strategies and genre-specific conventions; and (3) the micro-level of linguistic realizations and textual features. Within this framework, DHA focuses on four main discursive strategies: (1) referential strategies (how social actors are named and referred to); (2) predicational strategies (what qualities, traits, or characteristics are attributed to these actors); (3) argumentation strategies (how claims are justified through topoi or fallacies); and (4) perspectivization strategies (how speakers position their point of view). By applying these strategies systematically to newspaper texts, we can uncover how bride price is discursively constructed and legitimized or delegitimized.

The study also incorporates Van Leeuwen's (2008) framework of legitimation, which identifies four main legitimation strategies: (1) authorization (legitimation through reference to authority of tradition, custom, law, or persons with institutional authority); (2) moral evaluation (legitimation based on values); (3) rationalization (legitimation by reference to goals, uses, and effects of institutionalized social action); and (4) mythopoesis (legitimation conveyed through narratives). These strategies help reveal how media discourse justifies or criticizes bride price practices.

2.2 Socio-cultural context and media narratives of bride price in China

Bride price has been an integral part of Chinese marriage customs for over 2,500 years (Zhang, 2000). Historically, it symbolized the groom's financial commitment to the bride's family (Croll, 1981). Banned during the Maoist era (1949–1976) as part of efforts to eliminate “feudal” practices (Diamant, 2000), it re-emerged during the post-reform era (1978–present) due to the revival of traditional norms and new economic pressures (Yan, 2003). This modern resurgence is closely tied to socio-economic factors, including the gender imbalance caused by the one-child policy, which intensified competition for brides (Sun, 2012).

The one-child policy, implemented from 1980 to 2015, created significant demographic consequences that directly impact marriage and bride price practices. By 2005, the national sex ratio reached 119 boys per 100 girls, with rural second births skewing further to 112:100 due to son preference (Chen et al., 2024). The resulting scarcity of marriageable women, especially in rural areas, has driven bride price inflation, as families with sons compete fiercely for brides, which is a trend amplified by persistent traditional marriage customs.

Additionally, several recent policy developments have shaped the context of this study. In 2016, China implemented the “two-child policy,” relaxing family planning restrictions. In 2018, a national campaign against extravagant weddings was launched, with the government explicitly targeting “unhealthy” marriage customs including high bride prices. During 2018–2019, the rural revitalization strategy further emphasized reforming excessive marriage expenses as part of broader rural development goals. These policy interventions form an important backdrop for analyzing media discourse on bride price during our study period.

In rural areas, bride price is both a financial burden and a status symbol, whereas in urban areas, it reflects socio-economic shifts, often linked to property ownership and financial stability (Wei and Zhang, 2011).

The media plays a crucial role in shaping public discourse around bride price by negotiating traditional values and modern ideals. Both state-controlled and commercial news outlets often frame bride price as a cultural practice in need of reform, consistent with official discourses on gender equality and social stability (Stockmann, 2013). Conversely, some narratives highlight the cultural importance of bride price, portraying it as a tradition that strengthens familial bonds. This dual representation reflects ongoing societal negotiations between preserving tradition and adapting to modernization.

2.3 Gender dynamics in media representations of bride price

The practice of bride price is highly controversial from a gender perspective. Feminist scholars argue that it commodifies women and reinforces patriarchal norms (Eisenstein, 2005). Others defend it for its cultural significance and its role in providing economic security, particularly in rural areas (Najmabadi, 2008). Generational differences add another layer of complexity: younger urban individuals often challenge traditional practices, while older generations view bride price as a marker of family honor (Lindsey, 2015). This tension highlights the broader societal negotiation between tradition and modernity, intricately reflected in media narratives.

While existing research has extensively explored the socio-economic and gender dimensions of bride price, scholarly attention to media's role in shaping public discourse on this practice remains limited. Recent studies have begun addressing this gap, though with differing scopes and emphases. Wei (2020) examines Weibo posts through feminist discourse analysis, focusing on gendered power dynamics and the negotiation of women's bodies. Ma (2024a) also looks at social media, but focuses on the contrast between supporters and detractors of bride wealth, emphasizing how it is framed as protective or exploitative. In contrast, Ma (2024c) compares individual vs. organizational media, noting that individual users express a range of opinions, while organizational media uniformly adopt a negative stance due to China's pronatalist agenda. Finally, Ma (2024b) shifts to state media, revealing an androcentric discourse that operates within the framework of Beijing's anti-bride-price campaign yet paradoxically reinforces patriarchal norms. This study addresses that lacuna by examining how newspapers negotiate and reinterpret bride price, shedding light on the interplay between cultural practices and evolving public discourse.

2.4 Framing and agenda-setting in media discourse

This study draws on framing and agenda-setting theories to understand how newspapers shape public discourse on bride price. Framing theory, as conceptualized by Entman (1993), examines how media selectively emphasize certain aspects of an issue while downplaying others, thereby promoting particular problem definitions, causal interpretations, moral evaluations, and treatment recommendations. In the Chinese context, framing is particularly significant as it reveals how newspapers construct narratives that correspond to broader ideological positions while appearing to present objective reporting (Duan and Takahashi, 2017).

Agenda-setting theory, developed by McCombs and Shaw (1972), posits that media attention to specific issues increases their salience in public discourse. The theory distinguishes between first-level agenda-setting (media telling audiences what to think about) and second-level agenda-setting (media influencing how audiences think about issues). This study examines how bride price is positioned on the media agenda through coverage frequency, prominence in headlines, and contextual framing (McCombs, 2005).

The integration of these theoretical frameworks allows us to analyze not only the linguistic features of bride price discourse (through CDA) but also the broader patterns of representation that shape public understanding. By examining which aspects of bride price are highlighted or omitted in coverage, and how consistently these frames appear across different publications, we can identify the dominant narratives that shape public discourse on this cultural practice.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research approach and analytical framework

CDA allows for an in-depth examination of how media narratives construct and contest power relations and socio-cultural norms (Fairclough, 2013). By integrating agenda-setting and framing theories, this study examines how Chinese newspapers represent and frame bride price, particularly in their portrayals of women, and how these depictions reinforce or challenge traditional patriarchal norms (McCombs and Shaw, 1972). This multi-theoretical approach provides a comprehensive lens to understand the negotiation between tradition and modernity.

For framing analysis specifically, we applied Entman's (1993) framework to identify how newspapers defined the bride price problem, diagnosed causes, made moral judgments, and suggested remedies. This involved examining headlines, leads, metaphors, exemplars, catchphrases, and visual elements that communicate frame packages (Van Gorp, 2010). Agenda-setting analysis focused on the frequency, placement, and sustained coverage of bride price issues across the sample period, examining both the quantity of coverage and the qualitative aspects of how bride price was positioned as a public issue.

3.2 Data collection and analysis

Data for this study were drawn from the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) database, China's most comprehensive repository of print media. CNKI covers the vast majority of Chinese newspapers (national, provincial, and local) since 2000, making it ideal for analyzing mainstream news coverage of bride price. We focused on articles published from January 1, 2019, to December 31, 2023—a period chosen to capture media responses following major policy measures (such as the two-child policy and campaigns against extravagant weddings and “unhealthy” marriage customs since 2018) when public debate on bride price intensified.

A systematic search was conducted using keywords such as “彩礼” (bride price) and “婚俗' (marriage customs) across both national and regional/local newspapers. Our final dataset included 16 national newspapers (representing official party viewpoints and progressive urban perspectives) and 36 local/regional newspapers (reflecting regional concerns and cultural specificities). After manual verification and the elimination of duplicates, 113 articles were selected, forming the “Bride Price (BP) Corpus” of 231,597 tokens. Articles explicitly discussing bride price were included regardless of perspective, with our analysis identifying and categorizing the variety of viewpoints presented across the corpus.

We employed a multi-phase analytical approach that combined quantitative and qualitative methods. First, a keyword-in-context (KWIC) analysis identified high-frequency terms related to bride price, providing an overview of prevalent vocabulary in the corpus. Second, using DHA within CDA, we qualitatively analyzed how bride price was depicted and evaluated, examining how social actors were labeled, what attributes they were given, how arguments were constructed, and how perspectives were positioned. Third, drawing on van Leeuwen's legitimation model, we coded each text for occurrences of four legitimation strategies: authorization, moral evaluation, rationalization, and mythopoesis. Together, these phases captured both surface-level lexical patterns and deeper discursive strategies in the media's construction of bride price.

The coding process followed a hybrid approach blending deductive and inductive techniques. Deductive coding was guided by categories defined in the DHA and van Leeuwen frameworks to systematically identify known patterns. In parallel, inductive open coding allowed new themes to emerge from the data without preconceived categories. All articles were imported into NVivo software to manage and organize the coding. Two researchers coded the data collaboratively. Each initially coded a portion of the articles independently, then the team compared results and refined the codebook through discussion. Next, we performed axial coding to cluster related codes into higher-order themes that captured broader recurring ideas in the discourse. This process yielded key thematic categories that inform our findings. Intercoder reliability was assessed on a subset of the data, yielding a high agreement (Cohen's Kappa of 0.82). Any coding discrepancies were resolved by consensus, further reinforcing the rigor of the analysis.

4 Findings and discussion

This study reveals a complex portrayal of bride price in Chinese newspapers, illustrating how this practice is constructed as a site of cultural negotiation and social tension. The discourse is shaped by an interplay of economic, cultural, and gender-related factors, reflecting the broader dynamics of tradition and modernity in Chinese society.

The analysis of news coverage (Supplementary Table 1) reveals a balanced distribution of attention between national and local publications, with 55 articles from national newspapers and 58 from local ones. This balance provides a comprehensive overview of how bride price is framed in Chinese media.

National newspapers, such as China Women's News, People's Daily, and Legal Daily, tend to highlight broader societal trends, policy initiatives, and ideological discussions related to bride price reform. For instance, China Women's News contributed 11 articles, emphasizing themes such as advocating for “零彩礼” (zero bride price) and promoting gender equality. In contrast, local newspapers often focus on specific cases, regional initiatives, and local community responses to bride price reforms. For instance, Shangqiu Daily and Jiangxi Daily frequently address how traditional customs influence community practices. Moreover, legal discourse surrounding bride price is prominently featured in specialized publications like People's Court Daily and local legal newspapers such as Henan Legal News.

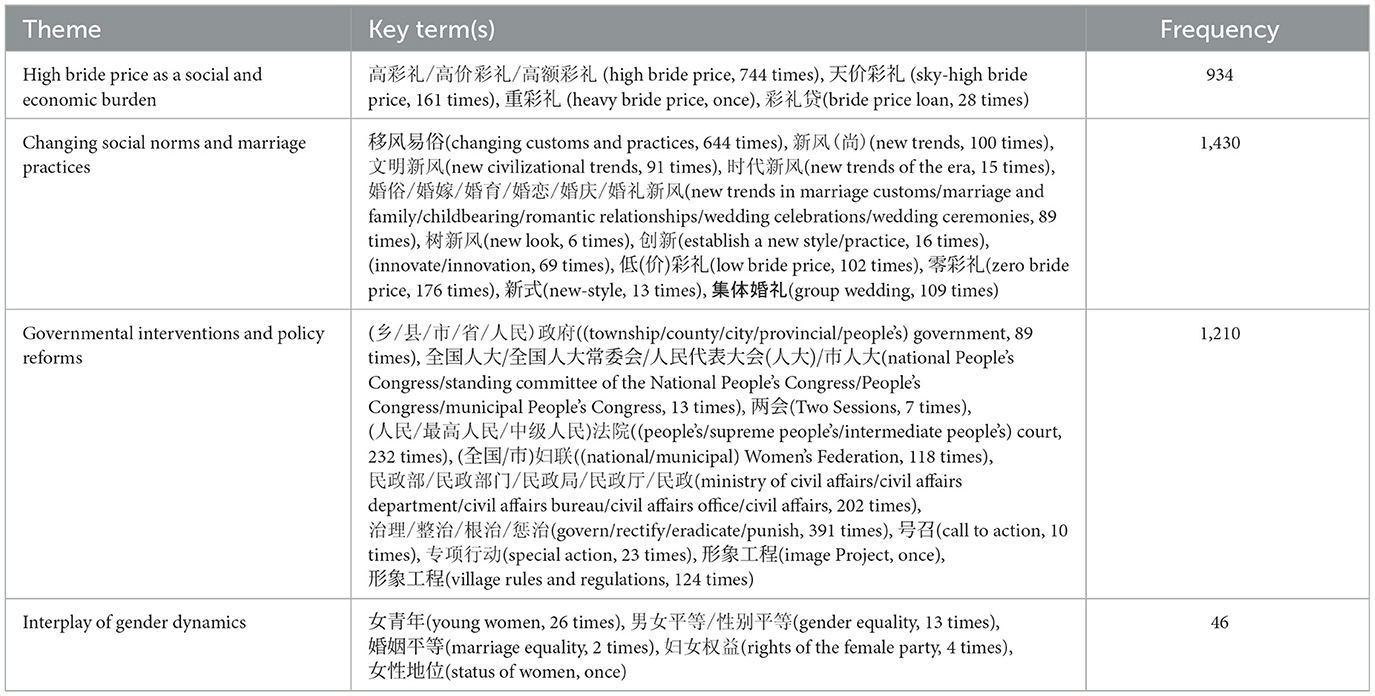

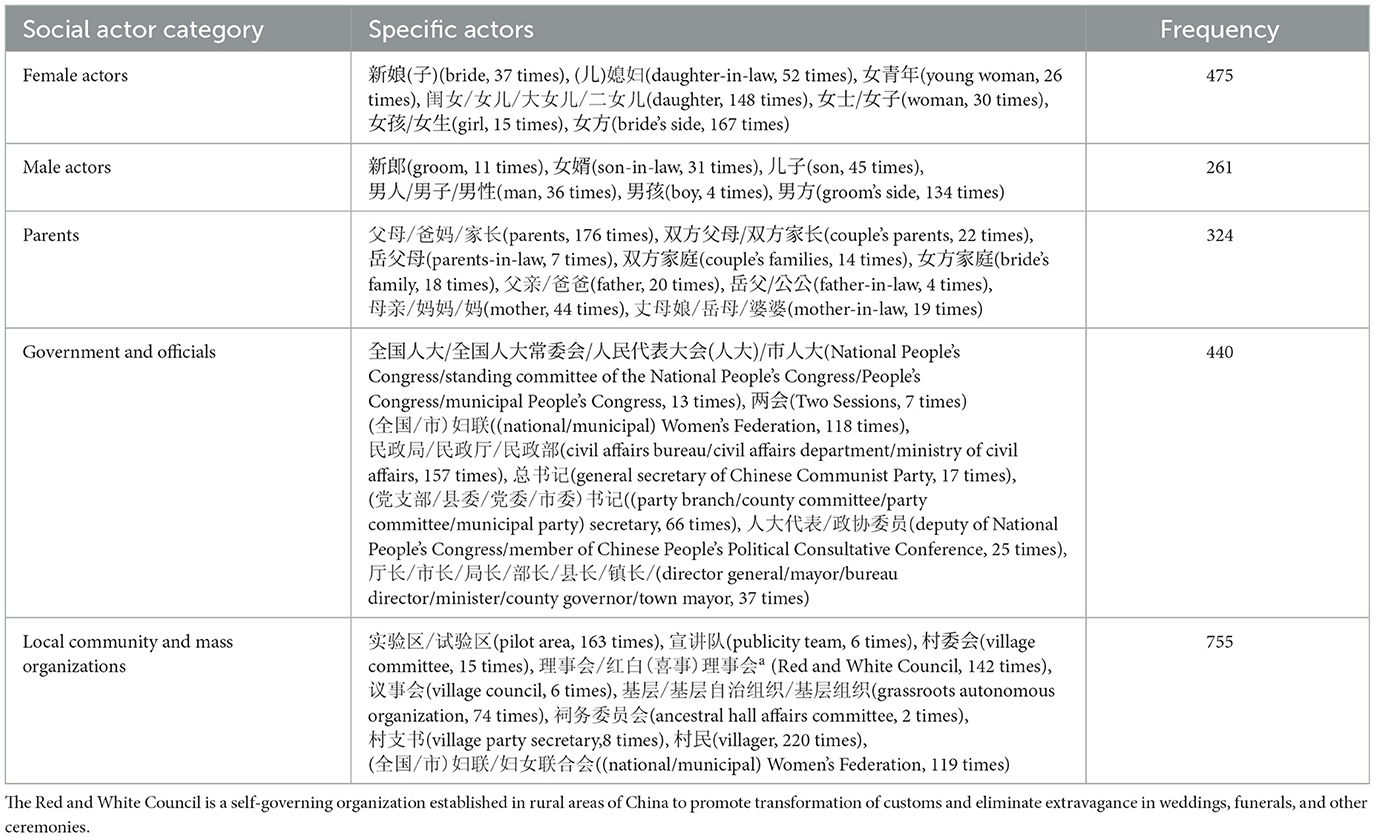

By applying CDA and integrating discursive strategies, the study identifies recurring themes (see Table 1), key social actors (see Table 2), and specific argumentative structures that shape media narratives on bride price.

Table 1 presents the frequency of key themes identified through a critical discourse analysis of Chinese newspaper articles on bride price. Under each theme, specific keywords (in Chinese with English translations) were identified and grouped for clarity. Total counts per theme are included to highlight their prominence in the discourse.

Table 2 presents the frequency of key social actors identified through a critical discourse analysis of Chinese newspaper articles on bride price. Under each social actor, specific keywords (in Chinese with English translations) were identified and grouped for clarity. Total counts per actor are included to highlight their prominence in the discourse.

4.1 Recurring themes

4.1.1 High bride price as a social and economic burden

A prominent theme in the media discourse is the portrayal of high bride prices as an unsustainable financial burden, particularly for rural families. As shown in Table 1, terms such as “高彩礼”/“高价彩礼”/“高额彩礼” (high bride price), “天价彩礼” (sky-high bride price), “重彩礼” (heavy bride price), and “彩礼贷” (bride price loan) appear 934 times, emphasizing the media's focus on the economic strain that bride prices place on families. Media outlets frequently utilize these terms to frame bride prices as a significant contributor to rural poverty, particularly in impoverished areas, thereby intensifying both financial and social pressures on households. For example, reports often dramatize the severity of this issue by presenting case studies that illustrate the devastating impact of high bride prices on family wellbeing.

Reports from Liangshan Daily highlight how soaring bride prices have turned weddings into burdens, with families falling into debt or being pushed back into poverty due to marriage expenses. For instance, one account notes: “在凉山的不少地方,一路飙升的彩礼,不仅让喜事变‘难事', 一些家庭甚至因此负债累累, 因婚致贫, 因婚返贫” (“In many parts of Liangshan, skyrocketing bride prices have not only turned joyous occasions into hardships but also left families deeply indebted, with ‘marriage-induced poverty' or ‘poverty caused by marriage”'). These articles employ predicational strategies by characterizing rural families with phrases such as “因婚致贫” (marriage-induced poverty) and “因婚返贫” (poverty caused by marriage), attributing to them the qualities of economic vulnerability and financial instability directly resulting from bride price demands. This framing evokes a powerful image of social and economic desperation, aligning with the frequent use of terms associated with the economic burden theme.

In another example, an article from China Discipline Inspection and Supervision Daily amplifies the portrayal of bride price as a financial burden through the detailed account of a family in Qingdao County, Shandong Province. The article employs language that emphasizes the severity of the situation with phrases such as “难以承受之重” (unbearable weight) and “令适婚青年望而却步” (causing marriageable young people to hesitate). These examples reflect a rationalization legitimation strategy (Van Leeuwen, 2008) that emphasizes the negative consequences of bride price to delegitimize the practice. These representations are strategically framed using argumentation strategies, citing local officials and social workers who describe high bride prices as a ““不良风气”” (unhealthy trend) that threatens the economic stability and cohesion of rural communities. By framing bride price as a public issue, the media calls for urgent policy intervention and reform.

The strategic use of referential strategies is evident in the emphasis on affected groups, frequently mentioning “贫困家庭” (impoverished families) and “低收入” (low-income) households to evoke empathy and moral outrage among readers. This aligns with the media's use of high-frequency terms to underscore the social and economic burdens posed by high bride prices.

A notable example appears in People's Political Consultative Conference Daily, where a local resident in Jingyuan County, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, argues that high bride prices have led to a “攀比之风” (trend of unhealthy comparison) among families, escalating costs to over 250,000 yuan in the region and putting immense pressure on both grooms' and brides' families. This discourse employs a moral evaluation legitimation strategy (Van Leeuwen, 2008) by presenting high bride prices as morally problematic, using value-laden terms like “攀比之风” (trend of unhealthy comparison) to condemn the practice. By constructing a compelling narrative, the media presents government action and social reform as necessary measures to mitigate the harmful consequences of the practice. The frequent mention of governance-related terms, such as “治理” (govern), “整治” (rectify), “根治” (eradicate) and “惩治” (punish), appearing 391 times under the theme of governmental interventions), further emphasizes the call for policy responses.

To achieve a more balanced perspective, the media also incorporates narratives that depict bride price as an important cultural safeguard for economic security and social honor. For instance, many locals explain that “彩礼其实是一种‘礼节', 大多数情况下, 女方父母会让 女儿带走这笔钱, 让她在婚后多一份保障一份底气” (bride price functions as a “courtesy ritual” and in most cases, the bride's parents let her keep the money as financial security and empowerment in marriage). This helps balance the predominant narrative critiquing bride price by acknowledging its cultural and emotional significance for many families.

4.1.2 Changing social norms and modernizing marriage practices

The media discourse on bride price in contemporary China highlights a significant shift in social norms, emphasizing the importance of ““移风易俗” (changing customs and practices) and promoting “新风尚” (new trends) in marriage rituals. As indicated in Table 1, terms like “移风易俗” (changing customs and practices) appears 644 times, ““低(价)彩礼” (low bride price) 102 times, ““新风尚” (new trends) 295 times, “新貌” (new look) 6 times, “树新风” (establish a new style/practice) 16 times and “零彩礼” (zero bride price) 176 times, “创新” (innovate/innovation) 69 times, ““新式” (new-style) 13 times and “集体婚礼” (group wedding) 109 times, totaling 1,430 mentions under this theme. The high frequency of these terms underscores the media's focus on advocating new ideals of equality, mutual respect, and financial prudence in modernizing marriage practices.

This theme is represented through positive narratives of families and couples who reject or minimize bride price demands, embracing concepts like “zero bride price” and “low bride price.” These decisions are depicted as symbols of progressive social values, often contrasted with traditional expectations to underscore the tension between old and new values. For instance, an article in Xinhua Daily Telegraph describes a Guizhou Province couple who chose “zero bride price” and held a simple wedding ceremony, accompanied by gifts and best wishes from parents on both sides, relatives, and friends. The article uses authorization legitimation (Van Leeuwen, 2008) by presenting this case as exemplary, implicitly suggesting that readers should follow this model because it represents the modern values endorsed by authority figures. This narrative is congruent with the theme of “changing customs and practices,” frequently highlighted in the discourse.

Similarly, China Women's News describes a “不要婚礼要幸福” (no bride price, just happiness) Group Wedding organized in Jiangxi Province, encouraging couples to pledge against high bride price demands and publicly support simplified marriage customs. This event involved 48 couples who took a public oath to “破除婚嫁旧俗” (eliminate outdated customs) and “做到婚事新办、喜事简办” (hold weddings with new practices and keep celebrations simple). The article employs perspectivization strategies by positioning these couples as moral exemplars, framing them as role models for the younger generation. The article underscores a societal shift toward more equitable and financially sustainable marriage practices, reflecting the adoption of “新风尚” (new trends) in both urban and rural communities. The frequent mention of “新风尚” (new trends) throughout the narrative reflects the media's endorsement of these progressive shifts.

4.1.3 Governmental interventions and policy reforms

Governmental interventions are portrayed as essential in addressing the negative social impacts associated with high bride prices. Table 1 highlights the prevalence of terms related to governmental actions: “法院” (court) and “政府” (government) at all levels appear 232 times and 89 times respectively, national and municipal “人大” (People's Congress) and its standing committee 13 times, “两会” (Two Sessions) 7 times„ “民政” (civil affairs) and relevant institutions such as ““民政部” (ministry of civil affairs) and “民政局” (civil affairs bureau) 202 times, “治理” (govern)/“整治” (rectify)/“根治” (eradicate)/“惩治” (punish) 391 times, “号召” (call to action) 10 times, national and municipal “妇联” (Women's Federation) 118 times, “专项行动” (special action) 23 times, “形象工程” (image project) once, and “村规民约” (village rules and regulations) 124 times, totaling 1,210 mentions. This prominence emphasizes the media's focus on the government's role in driving policy reforms and initiating social change. The Women's Federation, a mass organization operating under government supervision, acts as an intermediary between top-down policy and grassroots implementation, highlighting its dual role in both enforcing state directives and engaging with local communities.

Media outlets often underscore the proactive stance of local and provincial governments, portraying them as authoritative agents of social reform. For instance, in Kunming, Yunnan Province, the local government launched a “Rural Wedding Cost Reform Action Plan” aimed at curbing high bride prices through public campaigns, legal frameworks, and community guidelines. The frequent mention of “专项行动” (special action) underscores the emphasis on targeted governmental initiatives. These interventions are framed through authorization legitimation strategies (Van Leeuwen, 2008), presenting local officials as legitimate authorities to implement social reforms. The media employs referential strategies that position officials as “先锋” (pioneers) challenging outdated customs to promote social stability and economic development.

A detailed report in China Women's News highlights the impact of these initiatives in Dingxi City, Gansu, where officials implemented a cap on bride prices and organized village meetings to promote simpler wedding ceremonies. Articles frequently cite community leaders and civil affairs officials to validate these interventions through authorization legitimation, presenting institutional authority as sufficient justification for bride price reform. Nevertheless, some reports reveal resistance from rural families who perceive bride price as integral to preserving family honor and securing the bride's future. For example, an article in Xinhua Daily Telegraph describes community members defending high bride prices as “地方习惯” (local customs) and “传统风俗” (traditional practices) – an example of counter-authorization legitimation that appeals to the authority of tradition rather than institutions. This dynamic illustrates the broader cultural negotiation required for effective policy implementation, suggesting that educational initiatives must complement legal measures to achieve sustainable reform.

The media's frequent references to governmental bodies and policy terms reflect the portrayal of government-led reforms as pivotal in reshaping gender dynamics. While women are increasingly depicted as active agents of change, this empowerment is framed within a state-guided approach to social reform. For instance, the Women's Federation is depicted as enforcing state policies while also engaging at the grassroots level to foster change. This dual role underscores the portrayal of the government not only as a policy enforcer but also as a facilitator of evolving social norms, working alongside organizations like the Women's Federation to address the complexities of the bride price practice.

Ultimately, the framing of governmental interventions conveys a broader narrative of state-led efforts to modernize marriage customs and foster social stability. By positioning local officials and organizations like the Women's Federation as key actors in this transformation, the media reinforces the importance of collaboration between governmental bodies and community entities. These narratives reflect a belief that combining top-down interventions with grassroots initiatives is crucial to addressing entrenched cultural practices and fostering lasting social change.

4.1.4 Interplay of gender dynamics

The discourse surrounding bride price reveals a complex negotiation of gender dynamics, oscillating between narratives of commodification and empowerment. As indicated in Table 1, terms related to gender dynamics appear less frequently compared to other themes, with a total count of 46 mentions: “女青年” (young women) appears 26 times, “妇女权益” (women's rights) 4 times, “男女平等”/““性别平等”” (gender equality) 13 times, “婚姻平等” (marriage equality) 2 times and “女性地位” (status of women) only once. This relatively low frequency suggests that, although gender dynamics are present, they receive less media attention compared to themes like the economic burden or governmental interventions.

Newspapers employ discursive strategies to construct dual narratives that both reproduce and resist traditional gender norms, reflecting broader sociocultural tensions between patriarchal values and evolving ideals of gender equality. Several articles utilize predicational strategies to attribute qualities to women that reinforce their objectification, describing them as “隐形资产” (intangible assets) and “摇钱树” (money tree) whose value is measured by the bride price. This language reflects a predicational strategy that characterizes women in economic terms, reinforcing patriarchal structures by diminishing women's autonomy and positioning them as dependent on marriage for economic security, perpetuating traditional gender norms. Such narratives suggest that a woman's primary role in the marital transaction is to alleviate family financial pressures, reinforcing patriarchal expectations.

Moreover, narratives that emphasize governmental intervention in reducing high bride prices often implicitly support traditional gender roles by portraying women as dependent on external authorities for protection and guidance. The repeated use of phrases like “彩礼包袱” (bride price burden) employs predication that attributes dependency to women, reinforcing the idea that a woman's worth is tied to marital transactions. For instance, framing daughters as economic burdens, as seen in cases where families “借女儿外嫁达到脱贫的目的” (leverage daughters' marriages to escape poverty), further portrays women as passive beneficiaries of state intervention rather than as active agents capable of negotiating their social standing. The limited frequency of terms such as “男女平等”/“性别平等” (gender equality) and “婚姻平等” (marriage equality), appearing only 15 times, indicates that explicit discussions on gender equality remain marginal in the broader media discourse.

Conversely, some reports defend bride price as an economic safeguard for women, providing them with financial security and affirming their value within their families. For instance, an article in China Youth Daily quotes some families of the bride stating, “婚礼是男方对女方的尊重,也是今,也是今后婚姻生活的保障金” (the bride price is a sign of respect from the groom to the bride and also serves as a financial guarantee for their future married life). This perspective employs moral evaluation legitimation (Van Leeuwen, 2008) by presenting bride price as ethically sound because it ensures financial security for women. This perspective correlates with mentions of “妇女权益” (women's rights), suggesting that, in some contexts, bride price is framed as a protective measure, particularly in rural areas with limited social safety nets.

Other newspapers similarly depict bride price negotiations as instances of female agency, wherein women and their families use the practice strategically to assert power and achieve improved socio-economic outcomes in marriage. For instance, Farmers' Daily includes a quote from a young bride: “结婚时, 婆家给点钱, 生育时才有生活保障” (when getting married, the husband's family provides some money, which serves as financial support for the wife during childbirth). While this statement grammatically positions “the wife” in a passive role receiving support, the broader context of the article presents this as a strategic negotiation. The article employs perspectivization strategies that frame this practice from the viewpoint of women who actively secure financial guarantees through marriage. This representation portrays women not merely as passive recipients but as strategic agents utilizing bride price to gain financial security. Nevertheless, such narratives are relatively uncommon, as evidenced by the low frequency of terms related to women's status and agency within the broader discourse.

These conflicting narratives—women as commodified objects vs. women as agents of negotiation—highlight the ambivalence of bride price in the evolving gender discourse within Chinese society. While several articles critique the practice for reducing women to tradable commodities and reinforcing traditional norms, these critiques are not prominently featured, as indicated by the lower frequency counts. This duality is further complicated by articles promoting a shift away from bride price but often portraying women as victims in need of rescue rather than as agents capable of redefining the terms of their marriage. Such representations simultaneously resist and reproduce patriarchal norms by challenging the economic aspect of bride price while still framing women as passive beneficiaries of societal reforms.

The competing narratives in Chinese newspapers reflect broader societal debates on gender roles, commodification, and agency. Articles addressing governmental interventions, such as those in Legal Daily, often adopt a top-down perspective, reinforcing the notion that women need external assistance to overcome the detrimental effects of high bride prices. In contrast, some local reports from rural communities depict women as active agents, using bride price to leverage better outcomes for themselves and their families, though such portrayals are less common.

By critically engaging with these conflicting narratives, the media constructs diverse portrayals of women's roles, ultimately reflecting the broader tensions between tradition and modernity in contemporary Chinese society. The relatively low frequency of gender-related terms suggests that, while gender dynamics are an important aspect of the bride price discourse, they are not the primary focus of media narratives, which tend to prioritize themes such as economic burdens and governmental interventions.

4.2 Dominant social actors

The media discourse on bride price in Chinese newspapers involves a diverse array of social actors, each playing a significant role in shaping narratives around the practice. An analysis of key social actors reveals how the issue is framed and which perspectives are prioritized.

The media discourse on bride price in Chinese newspapers involves a diverse array of social actors, each playing a significant role in shaping narratives around the practice. Our analysis of referential strategies reveals patterns in how different actors are named and positioned within the discourse.

Female actors are prominently featured: terms like “新娘(子)” (bride) appears 37 times, “(儿)媳妇” (daughter-in-law) 52 times, “女青年” (young woman) 26 times, “闺女”/“女儿”/“大女儿”/“二女儿” (daughter) 148 times, “女士”/“女子” (woman) 30 times, “女孩”/“女生” (girl) 15 times and “女方” (bride's side) 167 times, totaling 475 mentions.

This emphasis underscores the central role women play in the bride price practice, both as participants and as subjects affected by its implications. The referential strategies employed in naming female actors often position them in relation to the marriage institution or family structure (e.g., “bride,” “daughter-in-law”) rather than as independent agents, reflecting an implicit predicational strategy that attributes dependency to women. And the frequent references to daughters suggest a focus on familial relationships and the emotional dimensions of marriage customs, highlighting societal expectations placed on women and their families. In contrast, male actors, such as “儿子” (son), “新郎” (groom), “女婿” (son-in-law), “男人”/“男子”/“男性” (man) and “男方” (groom's side) are mentioned less frequently, with counts of 134 in total, indicating that men's perspectives are less prominently featured in the media discourse on bride price.

Parents, collectively, are among the most frequently mentioned social actors, appearing 324 times with terms such as “父母”/“爸妈”/“家长” (parents), “双方父母/“双方家长” (couple's parents), and “岳父母” (parents-in-law). Mothers are specifically mentioned 44 times, while fathers are mentioned 20 times, highlighting the significant involvement of parents in marriage arrangements and bride price negotiations. This referential pattern constructs bride price as a family affair rather than an individual decision, employing argumentation strategies that emphasize family involvement as justification for maintaining or reforming the practice. The higher frequency of mothers may indicate that they are portrayed as more actively engaged or influential in the negotiation processes.

Government entities and officials also feature heavily, underscoring the state's active role in addressing the bride price issue, with the key terms appearing 440 times such as “总书记” (general secretary of Chinese Communist Party), and “人大代表” (deputy of National People's Congress), and “政协委员” (member of Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference). The frequent reference to government officials functions as an authorization legitimation strategy, constructing state involvement as appropriately authoritative in regulating cultural practices. This substantial representation suggests that efforts to reform bride price practices are driven at multiple administrative levels, with media narratives portraying the state as a key agent in promoting social change and modernizing marriage practices.

Local community actors and organizations are prominently featured as well. “村民” (villager) is mentioned 220 times and “妇联” (Women's Federation) appears 62 times, indicating strong community involvement in the discourse on bride price. These referential strategies construct a collaborative social effort, employing perspectivization that frames bride price reform as a grassroots movement rather than solely a top-down imposition. The inclusion of organizations like the Village Committee and the Red and White Council (a self-governing body established to eliminate extravagance in ceremonies) points to grassroots efforts to address the social and economic issues associated with bride price.

It is worth noting that the Women's Federation is categorized under both “Government and Officials” and “Local Community and Mass Organization,” reflecting its unique positioning as both an extension of governmental efforts and an advocate within local communities. This dual categorization reveals a perspectivization strategy that legitimizes the organization's influence by presenting it as simultaneously authoritative (government-affiliated) and representative (community-based). By actively engaging at the community level, the Women's Federation not only enforces state policies but also empowers local actors through education and community events, advocating for the transformation of marriage customs.

Media reports detail stories of young women in Jiangxi Province who defied tradition by refusing the expected bride price, supported by the Women's Federation and emphasizing values of mutual respect and equality. These narratives employ mythopoesis legitimation, using exemplary stories to illustrate the positive outcomes of rejecting high bride prices. The Women's Federation also supports initiatives where young women sign pledges to resist high bride prices and are celebrated as “践行者” (practitioner) of new marital customs. These narratives underscore the agency of women in challenging traditional patriarchal norms, with the Women's Federation serving as a crucial intermediary in these changes.

The varying frequencies of social actors reveal how the media frames the discourse: emphasizing familial and gender dynamics, highlighting governmental involvement, and acknowledging community engagement. However, the underrepresentation of grooms and fathers suggests a potential gap in the discourse regarding men's perspectives and responsibilities.

4.3 Argumentation strategies in newspaper discourse

Analyzing the argumentation strategies employed in newspaper discourse on bride price is significant because it reveals how media narratives shape representations of this culturally sensitive practice. By applying DHA's focus on argumentation strategies, we can identify the topoi (conventional argumentative patterns) and fallacies used to justify particular positions on bride price.

Newspapers utilize various argumentation strategies to frame, justify, or contest the practice of bride price, including appeals to social norms, consequences, and endorsements from authoritative voices. These strategies play a crucial role in shaping representations of bride price, contributing to the ongoing negotiation between tradition and modernity in Chinese society.

The topos of burden is frequently employed to delegitimize high bride price. For example, an article in Dingxi Daily employs predicational strategies that attribute negative qualities to high bride prices, describing them as “蚕食脱贫攻坚成果” (eroding the achievements of poverty alleviation) and “阻碍乡村振兴步伐” (hindering the progress of rural revitalization). These predicational strategies link bride price to broader economic and social concerns. The article employs moral evaluation legitimation (Van Leeuwen, 2008) by contrasting the morally problematic “高价彩礼” (high bride prices) with the morally virtuous “低价彩礼” (low bride price), positioning the latter as aligned with national development goals. The story features a father from Gansu Province who defied high bride price demands for his daughter. Through mythopoesis legitimation (Van Leeuwen, 2008), this narrative functions as a moral tale where rejection of high bride price leads to positive outcomes, encouraging readers to view zero bride price as progressive and high bride price as outdated.

Rationalization legitimation strategies (Van Leeuwen, 2008) are also prevalent, particularly in reports focusing on the socio-economic impacts of high bride prices. These strategies delegitimize bride price by emphasizing its negative consequences. A report in Xinhua Daily Telegraph highlights a case in a severely poverty-stricken rural area, where a young man had to spend an additional 320,000 yuan to meet bride price demands immediately after covering his father's 200,000 yuan funeral costs. The financial strain led to heavy debt. The article employs argumentation strategies based on the topos of burden, presenting high bride prices as a societal problem that “低价彩礼” (slowed down the pace of striving for a happy life) and “乡风文明'沦为空谈” (turned “rural cultural civility” into empty talk). This represents both rationalization and moral evaluation legitimation, presenting high bride price as both harmful in its consequences and morally problematic in undermining cultural values.

Authorization legitimation strategies (Van Leeuwen, 2008) are frequently employed through the inclusion of authoritative voices, such as legal experts, policymakers, and sociologists. By citing experts and respected figures, the media enhances the persuasive power of their narratives. This strategy legitimizes viewpoints by appealing to the authority of expertise rather than providing independent justification. For instance, an article in China Youth Daily cites Professor Jin Xiaoyi, a sociologist in China, who asserts that high bride prices lead to “婚姻缔结过度物化” (excessive commodification of marriage), increasing the risk of rural families falling into or returning to poverty due to marriage, infringing upon the marriage rights of rural women, and causing significant difficulties for many rural men in getting married, with some even remaining unmarried permanently. This example combines authorization legitimation through expert authority with rationalization legitimation through enumeration of negative consequences.

Media discourse also frequently employs moral evaluation legitimation strategies (Van Leeuwen, 2008) to appeal to readers' ethical sensibilities. In an article in Farmers' Daily, Zhou Shihong, a Member of the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference and Chairman of the Supervisory Board of the Anhui Provincial Lawyers Association, is cited as saying that “高价彩礼把婚姻异化为买卖” (high bride prices have turned marriage into a transaction), worsening social customs. This statement employs moral evaluation by invoking the value-laden concept of marriage being “turned into a transaction” implicitly constructing an opposition between proper marriage (based on love and commitment) and improper marriage (reduced to a financial transaction). The article also employs referential strategies that position high bride price as a corrupting force, portraying it as a societal ill that threatens familial harmony and erodes community values. This combination of moral evaluation and authorization legitimation (through the official's credentials) strongly delegitimizes high bride price practices.

4.4 Generational tensions and intergenerational negotiations

The issue of bride price generates significant generational tensions, as older and younger generations often hold conflicting views on its necessity and value. Media discourse constructs this generational divide through predicational strategies that attribute different values to each generation. Newspapers frequently frame these tensions as a clash between “传统观念” (traditional beliefs) held by older family members and “现代文明” (modern civilization) embraced by younger people, especially in urban areas where education and exposure to modern values have shifted attitudes. This binary construction employs perspectivization strategies that position modernity as progressive and tradition as outdated, reflecting the media's implicit stance favoring bride price reform. Such narratives portray intergenerational negotiations over bride price as microcosms of the broader societal struggle between preserving tradition and adapting to modernity.

A detailed example of intergenerational conflict uses mythopoesis legitimation to illustrate the tension between traditional and modern values. An article from Workers' Daily highlights the story of a young couple in Chongqing City, who faced resistance from the bridegroom's parents, staunch advocates of traditional customs, when they insisted on marrying without a bride price. The article employs referential strategies that position the parents as defenders of tradition, citing their argument that a bride price of 99,000 yuan symbolized “长长久久” (forever and ever), a phrase that sounds similar to the pronunciation of “99” in Chinese. This example illustrates the topos of tradition, where cultural symbolism is used to justify maintaining bride price practices. This cultural symbolism underscores a deep wish for longevity and enduring unity within the marriage. The insistence on this specific amount reflects not only adherence to traditional customs but also the symbolic importance of numbers in Chinese culture. Through this narrative, the article constructs a perspectivization that represents the generational divide as a clash between symbolic tradition and practical modernity. This case demonstrates how cultural symbolism and generational values intersect, with older generations prioritizing gestures they believe will ensure a successful and harmonious marriage. By emphasizing the symbolic significance of bride price, older generations may unintentionally place pressure on younger family members to conform, even when these expectations clash with modern views on marriage or the financial wellbeing of the couple. Thus, this example illustrates how the influence of cultural symbolism and generational beliefs can perpetuate bride price practices, often at the expense of younger generations' preferences and financial considerations.

Another narrative employs the topos of compromise to suggest a middle path between tradition and modernity. An article from Nanjing Daily recounts the experience of a young couple in Nanjing who faced intense pressure from the bride's parents to adhere to traditional marriage customs and offer a substantial bride price. The article employs predicational strategies by attributing traditional motivations to the father, stating he hoped to “让女儿嫁得风光” (let the daughter marry with prestige), constructing prestige and social status as core values for the older generation. This reinforces the idea that older generations view bride price as essential for preserving social status. The article employs rationalization legitimation by presenting community intervention as an effective solution, narrating how the bride's parents managed to reduce the bride price and simplify the wedding process by involving local community workers who mediated the negotiations, thereby framing community intervention as a way to ease generational tensions and promote more sustainable marriage practices.

In summary, generational tensions over bride price illustrate broader societal conflicts between tradition and modernity, with older generations valuing customs tied to social status and cultural heritage, while younger generations prefer egalitarian and practical marriage approaches. Media discourse constructs this tension through predicational strategies that attribute different values to each generation and perspectivization strategies that generally favor modern approaches. Community intervention is presented through rationalization legitimation as a compromise solution, presenting a potential pathway for reconciling generational differences and gradually transforming marriage practices in China.

5 Conclusion

This study uses CDA to examine how Chinese newspapers represent the issue of bride price, focusing on the discursive construction of social actors and their sociocultural implications. Four main themes are identified: bride price as a socio-economic burden, evolving social norms and modernizing marriage practices, governmental interventions and policy reforms, and gender dynamics. These themes highlight bride price as both a deeply rooted cultural tradition and a socio-economic challenge, illustrating the tension between tradition and modernity.

The findings show that media representations largely depict high bride prices as a significant financial burden, particularly for rural families. Discursive strategies link bride price demands to rural poverty, intergenerational debt, and social instability, framing it as a systemic issue needing urgent policy intervention. A shift in discourse is noted in the media's growing advocacy for “zero bride price” and “low bride price” marriages, presented as symbols of modernity and financial responsibility. The media employs moral evaluation to portray these alternatives as aligning with contemporary values of equality and mutual respect, highlighting support from local officials, community leaders, and women's federations.

Gender dynamics are complex, with narratives depicting women as both commodified subjects and empowered agents. This ambivalence reflects the intricate gender discourse in bride price narratives, where support for gender equality is often counterbalanced by reinforcement of patriarchal norms. Media portrayal of government actors suggests a top-down approach to gender reforms, with women's empowerment framed within state-defined stability.

The study identifies how media discourse actively constructs representations of bride price through discursive strategies. Notably, rationalization and moral evaluation emerged as the most frequently employed legitimation strategies in the coverage. Journalists detail the socio-economic consequences of bride price to rationalize the need for change, and they issue moral judgments condemning exorbitant bride price as an unhealthy or unjust practice. Authorization is also evident, as the press frequently invokes government directives, laws, and authoritative voices to bolster calls for reform, while mythopoesis is used in the form of personal stories and case studies to illustrate the harms of high bride prices or the benefits of reform. Collectively, these discursive strategies present bride price as a cultural practice in urgent need of change, even as some reporting acknowledges its traditional legitimacy and social functions.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the exclusive focus on newspapers potentially overlooks insights from other media forms like television, online forums, and social media. Second, the study's timeframe (2019–2023) may not capture long-term complexities of bride price discourse. Third, this study's qualitative design examines media representations without direct audience data, so we cannot make claims about how these representations influence public perception. Future research should explore how digital media and grassroots movements construct alternative narratives about bride price, as well as how audiences interpret and respond to media representations. This study provides valuable insights for policymakers, gender advocates, and media scholars into how media discursively construct and negotiate cultural practices in contemporary China.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

WL: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. SZ: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CS: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank our reviewers and editors for their extensive support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2025.1525371/full#supplementary-material

References

Chen, F., Wang, C., and WangDing, Y. (2024). The interplay of sibling sex composition, son preference, and child education in China: evidence from the one-child policy. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 43:65. doi: 10.1007/s11113-024-09910-6

Croll, E. (1981). The Politics of Marriage in Contemporary China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Diamant, N. J. (2000). Revolutionizing the Family: Politics, Love, and Divorce in Urban and Rural China, 1949–1968. Berkeley: University of California Press. doi: 10.1525/9780520922389

Duan, R., and Takahashi, B. (2017). The two-way flow of news: a comparative study of American and Chinese newspaper coverage of Beijing's air pollution. Int. Commun. Gazette 79, 83–107. doi: 10.1177/1748048516656303

Eisenstein, H. (2005). A dangerous liaison? Feminism and corporate globalization. Sci. Soc. 69, 487–518. doi: 10.1521/siso.69.3.487.66520

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 43, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Erigha, M. (2015). Race, gender, hollywood: representation in cultural production and digital media's potential for change. Sociol. Compass 9, 78–89. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12237

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203697078

Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315834368

Foster, N., Cook, K., Barter-Godfrey, S., and Furneaux, S. (2011). Fractured multiculturalism: Conflicting representations of Arab and Muslim Australians in Australian print media. Media, Cult. Soc. 33, 619–629. doi: 10.1177/0163443711399034

Ji, Y. (2015). Between tradition and modernity: “Leftover” women in Shanghai. J. Marriage Fam. 77, 1057–1073. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12220

Jiang, Q., and Sánchez-Barricarte, J. J. (2012). Bride price in China: the obstacle to “Bare Branches” seeking marriage. Hist. Fam. 17, 2–15. doi: 10.1080/1081602X.2011.640544

Lindsey, T. (2015). Post-Ferguson: A “herstorical” approach to black violability. Feminist Stud. 41, 232–237. doi: 10.1353/fem.2015.0041

Ma, J. (2024a). Protection or commodification of women? Discursive construction of bridewealth on Chinese social media. Feminist Media Stud. 1–17. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2024.2356547

Ma, J. (2024b). Alignment, negation, and androcentricity: representation of bride price by Chinese state media. Soc. Semiotics 1–20. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2024.2413565

Ma, J. (2024c). A comparative study of bride price representation on Chinese social media. J. Humaniti. Arts Soc. Sci. 8, 2636–2644. doi: 10.26855/jhass.2024.11.029

McCombs, M. (2005). A look at agenda-setting: past, present and future. J. Stud. 6, 543–557. doi: 10.1080/14616700500250438

McCombs, M. E., and Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin. Q. 36, 176–187. doi: 10.1086/267990

Najmabadi, A. (2008). Transing and transpassing across sex-gender walls in Iran. Women's Stud. Q. 36, 23–42. doi: 10.1353/wsq.0.0117

Reisigl, M., and Wodak, R. (2000). Discourse and Discrimination: Rhetorics of Racism and Antisemitism. London: Routledge.

Ruele, M. (2021). “Contextual African theological interpretation of ilobola as a gender issue in the era of globalization,” in Lobola (bridewealth) in Contemporary Southern Africa, eds. L. Togarasei and E. Chitando (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 329–342. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-59523-4_21

Stockmann, D. (2013). Media Commercialization and Authoritarian Rule in China. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139087742

Sun, W. (2012). Desperately seeking my wages: justice, media logic, and the politics of voice in urban China. Media Cult. Soc. 34, 864–879. doi: 10.1177/0163443712452773

Sun, W., and Zhao, Y. (2009). “Television culture with “Chinese characteristics”: The politics of compassion and education,” in Television Studies After TV: Understanding Television in the Post-Broadcast Era, eds. G. Turner, and J. Tay (London: Routledge), 96-104.

To, S. (2015). China's Leftover Women: Late Marriage Among Professional Women and Its Consequences. New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315857596

Van Gorp, B. (2010). “Strategies to take subjectivity out of framing analysis,” in Doing News Framing Analysis: Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives, eds. eds. P. D'Angelo, and J. Kuypers (New York: Routledge), 84–109.

Van Leeuwen, T. (2008). Discourse and Practice: New Tools for Critical Discourse Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195323306.001.0001

Wei, S. (2020). A feminist critical discourse analysis of ideological conflicts in the We-Media representation of bride price in Mainland China (dissertation). National University of Singapore, Singapore.

Wei, S. J., and Zhang, X. (2011). The competitive saving motive: evidence from rising sex ratios and savings rates in China. J. Polit. Econ. 119, 511–564. doi: 10.1086/660887

Yan, Y. (2003). Private Life Under Socialism: Love, Intimacy, and Family Change in a Chinese Village, 1949–1999. Stanford: Stanford University Press. doi: 10.1515/9780804764117

Keywords: bride price, critical discourse analysis (CDA), Chinese newspapers, gender dynamics, tradition and modernity, marriage customs

Citation: Liu W, Zhang S and Sun C (2025) Negotiating tradition and modernity: a critical discourse analysis of bride price representations in Chinese newspapers. Front. Commun. 10:1525371. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1525371

Received: 09 November 2024; Accepted: 16 April 2025;

Published: 12 May 2025.

Edited by:

Niki Murray, Massey University Business School, New ZealandReviewed by:

Ahnlee Jang, Hongik University, Republic of KoreaMelissa Yoong, University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, Malaysia

Copyright © 2025 Liu, Zhang and Sun. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chengzhi Sun, Y3pzdW5AZGx1dC5lZHUuY24=

Wenyu Liu

Wenyu Liu Siqi Zhang

Siqi Zhang Chengzhi Sun

Chengzhi Sun