- School of Global Development, University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom

Alternative media is increasingly a strategic tool in environmental justice movements. One area that remains especially understudied is how marginalised women, specifically, indigenous and Dalit women, use alternative media in India to put forward their own perspectives on environmental justice, sustainable development, and climate change. This paper contributes by bringing together studies of digital media and environmental justice using their shared concepts of reclaiming power, justice, and citizenship. The research provides a feminist perspective on whose knowledge is valued; who creates knowledge; and whether production of alternative knowledge challenges dominant discourses in media and policy about environmental justice. The paper shares select findings about research on the communicative practice of an Indian grassroots women’s collective which has recently started using digital media to share rural perspectives on environmental justice. The paper foregrounds an Ecolinguistic analysis of the media produced by these women, bolstered by findings from participatory workshops and interviews which point to the production context as well as power asymmetries women face. Analysing the women’s narratives, we see that they document traditional practices of farming, seed diversity, accessing small forest produce, and heritage skills such as weaving. The analysis reveals how women use their stories to make women’s roles visible in farming, local crafts, rituals and conservation. They also use the stories to position themselves as experts and memory keepers of traditional ways of life. Further, they produce discourses about development which value a symbiotic relationship between humans and nature; where culture, spirituality and nature are enmeshed, and which is critical of a neo-liberal development agenda.

1 Introduction

When it comes to conversations and debates around environmental justice, sustainable development, and climate change, whose voices are we listening to? And who makes it to the spaces (physical or virtual) where these conversations take place? These questions underpin my research which explores how marginalised women in India, especially Dalit and Indigenous women, use alternative media to share their perspectives on environmental justice and development alternatives. The main premise of this research is that since media plays a seminal role in setting the agenda of how a capitalist, hetero-patriarchal world operates, it is also a space where these discriminatory social, political, and economic structures need to be challenged. Alternative media literatures and practices have investigated aspects such as the medium’s role in expanding the digital public sphere (Couldry, 2010), creating counterpublics for subaltern groups (Fraser, 2007; Dutta, 2016), and in being fundamental pillars of active citizenship (Livio, 2017). Further, a small subset of this literature asserts that the digital public sphere can reproduce hegemonies of social structures. Questions of physical and technological access and user literacy should be seen alongside racial, ethnic, economic and gender imbalances which marginalise those already on the peripheries (Pleyers and Suzina, 2016; Gurumurthy and Chami, 2019).

Despite current power asymmetries that shape it, alternative media is increasingly a strategic tool in environmental justice movements. Place-based movements and conflicts over environment have rooted themselves in seeking justice for their communities and for their ecology globally. Justice here, goes beyond the distribution of benefits and costs of environmental resources (Jamieson, 2007; Martinez-Alier, 2014). Justice includes participation – including who is included in environmental decision making; and recognition of diverse knowledges and cosmovisions about environments, and about what constitutes development (Jamieson, 2007; Temper et al., 2015; Schroeder and González, 2019). Environmental justice movements in that sense are about creating wider transformations in the power asymmetries (Temper et al., 2018) which have for instance placed the burden of pollution or extreme weather events on marginalised communities; they are about including perspectives that have been kept out of public policy on environmental planning, notably indigenous worldviews; and they are about recognising that many ways of seeing exist beyond the confines of western ‘scientific’ knowledge. By making marginalised perspectives visible, alternative media is most closely aligned with justice as recognition and as an advocacy tool it enables participatory justice.

It is in this wider context that this paper examines the communicative practices of Maati Collective, an autonomous women’s collective based in the Himalayan state of Uttarakhand. The Collective, along with its sister organisation Himal Prakriti, works with people from across 50 villages in Munsiari Sub-Division located in the Gori River Valley. There are currently ten core members of the collective – seven women and three men – who carry out the bulk of the work under the aegis of Himal Prakriti. These core members come from the neighbouring villages of Sarmoli-Jainti and Shankhdhura. Like the community it operates in, the Collective has a mix of social groups – people from the Indigenous Bhotiya community, Dalits, land-owning Jimdars, and ‘upper caste’. For three decades, the Collective has sought a vision for development rooted in social and environmental justice, centring women’s rights in the process. They work on stopping violence against women, eco homestays, reviving woollen weaving, food security and forest conservation, amongst others. Maati Collective works in an ecologically sensitive area with diverse forest cover ranging from sub-tropical (1,000 metres above sea level) to alpine types (>4,200 metres) (Foundation for Ecological Security, 2005). The river valley and Munsiari particularly, is a popular spot for the local and international birding community. The communities here have historically relied on forest commons for their survival. Like many communities in India, they face active conflict because of dwindling forest resources on one hand, and systematic restriction of access rights on the other (Foundation for Ecological Security, 2005). Between 2006–2010 members of the Collective, along with the wider community, were instrumental in mobilising against a dam along the Gori River to be built by the National Thermal Power Corporation; the dam would have required 280 hectares of forest land, mostly under forest commons (field notes, 2023). Further, this community has a rich repository of living heritage in the form of historic transhumance practices, oral storytelling, weaving and textiles, festivals, music, amongst others. These are the life experiences which Maati Collective’s media making and storytelling draws upon; their grassroots perspectives on environmental justice. Drawing on a small sample of media produced by the women in Maati Collective I examine what discourses do marginalised women produce through alternative media? Do these discourses position their knowledge systems as counter narratives to the dominant discourses on development and environmental justice?

The Indian constitution refers to Indigenous communities as ‘Scheduled Tribes’ based on the affirmative action they receive. But beyond that they are not recognised as Indigenous as they are in many countries such as in Bolivia, Peru, New Zealand, etc. The communities refer to themselves as Adivasis or Tribal depending on the region. In this paper I call them Indigenous people as an umbrella term. Indigenous people who represent 8.6% of the Indian population, and Dalits, who make up 16.6% of the population (Government of India, 2011), barely have representation in the Indian media. A 2019 survey by Oxfam and Newslaundry (2019) on the diversity of 50 Indian newsrooms (print, TV, digital and magazines) found that only 5% articles in English newspapers and 10% in Hindi ones were written by Adivasis or Dalits. The search for women in Indian newsrooms is as elusive. A UN Women and Newslaundry (2019) report on women in the media found that while newspapers had no women in leadership positions, digital portals had 26.3%, TV had 20.9% and magazines had 13.6%. The Global Media Monitoring Project’s (GMMP) (2020) report found that only 14% news analysed across print, TV and radio had women as subjects and sources. This number has consistently dropped: it was 21% in 2015 and 22% in 2010. Since neither the UN Women report nor GMMP further disaggregate their data it is impossible to tell how many women were Indigenous or Dalit.

The exclusion of such marginalised voices from Indian media is telling of the inequalities that run rampant in Indian society and indeed of what gets reported about marginalised groups. Since the economic liberalisation of India in 1991, the number of TV channels has grown exponentially: from one state owned public service broadcasting channel to 900 private TV channels currently (BBC, 2023). There have been strong critiques of how commercial media pays little attention to rural issues at the cost of selling a neoliberal agenda (Himal South Asian, 2010) and of the media’s obsession with crime, cinema and cricket (Thussu, 1999). There is a strong nexus between corporate houses, media and politicians. A media house with stakes in a mining company is unlikely to report on protests by local Adivasi communities against it (Sharma 2013 in Dutta, 2016).

Cumulatively, these factors shape the dominant discourses about marginalised communities in the Indian media and policy-making circles – as hindrances to forest conservation rather than as allies; as anti-development or “anti-national” when they protest projects like national parks, mining industries, highways, dams and wind power projects. On the one hand, we see conservationists petitioning for the removal of some 7.5 million people from their forest homes (International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, 2019) despite having land use rights. On the other hand, State agencies often divert such protected forests for extractive development projects (Domínguez and Luoma, 2020). Meanwhile, the neo-liberal model of development followed by the country has left many communities further impoverished. Oxfam’s (2023) report “Survival of the Richest” finds that 30 per cent of India’s population own more than 90 per cent of the total wealth whilst the bottom 50 percent own 3 % of the wealth.

Caught in this web, marginalised communities have been at the forefront of environmental justice movements and grassroots experiments to not only secure their own rights but of the nature around them. These movements also envision development beyond the neo-liberal agenda adopted by the country, and instead root alternatives on principles of socio-political and economic equity. A significant coalition leading this effort is Vikalp Sangam, of which Maati Collective is a member. Examples of their alternatives to development include a range of solutions from access to food, water and energy to citizen science and grassroots innovations and democratising knowledge for transformations. Many of these movements have used alternative media to exercise agency and gather support. Some examples include: The Save Mahan campaign where indigenous communities used radio to mobilise against coal mines in a pristine forest in Madhya Pradesh; the anti POSCO protests in Odisha, where communities positioned local fisheries and cashew farms as sustainable development in opposition to a steel factory through participatory video; farmers in north India using citizen journalism to report their stories whilst protesting discriminatory laws because the mainstream media villainised them as terrorists.

This contingent, especially the Vikalp Sangam coalition, sees alternative media as both, a form of transformation and the medium through which ideas about alternatives are shared with wider communities. As transformative projects, alternative media brings to the surface questions and narratives that are ignored by mainstream media such as the knowledge that women from Indigenous and Dalit communities have about local seeds or about alternative forms of democracy. They open media making to a range of citizens who have been excluded from these spaces, for instance, Dalit women farmers, fisher folk, adivasi communities living in forests. And because these communities often have unique perspectives on the dominant political and economic systems, the media they make can be seen as strategies that could pave the way for alternative futures (Sangam, 2017).

Drawing on commonalities between alternative media and environmental justice, Foxwell-Norton (2015) suggests that both pursue the goal of citizen participation and democracy and giving voice. Drawing on Foucault, she further says that alternative media represents the possibility that the cultural recognition will in turn pave the way for a more structural recognition of community rights in environment. Sharing the diverse cosmovisions which enmesh culture, spirituality and the natural world through stories results in actions of cultural revitalisation (Rodríguez and Inturias, 2018). The revitalisation is critical especially where younger generations are losing touch with the nature around them.

I consider Maati Collective’s use of alternative media as a counterpublic (Fraser, 2007)—a place where people from subaltern groups can come together to challenge the dominant mainstream narratives. In the Indian context, feminist publics as well as marginalised communities have used digital media to create such counterpublics (Zaslavsky, 2016; Gurumurthy and Chami, 2019). These spaces are seen as a challenge to dominant discourses about them (e.g., victims of violence; anti-national when they protest), especially since they find little representation in mainstream media. Thakur (2020) finds that Dalits see “internet-enabled media in enabling political discourse among marginalized groups” (no pg.). Adivasis too, create their own media to get recognition of their knowledge, as well as build solidarities amongst each other (Dutta, 2016). Maati Collective, then challenge whose knowledge is valued; who creates knowledge; and whether production of alternative knowledge challenges dominant discourses in media and policy about environmental justice.

In following paper, I first explain the method of Ecolinguistics used here, along with the sample selection and framework of analysis. I then analyse the media produced by Maati Collective where I reveal that women are able to make their unrecognised roles in agriculture, crafts, care-work and conservation. The storytelling highlights discourses about women’s pivotal roles as memory keepers of traditional ways of life like farming, weaving and ritualistic aspects of life. They also position themselves as experts. Further, the women share a discourse of development and environmental justice which is rooted on the values of ecological integrity, and recognises diverse cosmologies and knowledge systems. The selection of stories here should be read as a call for a more sustainable and just way of development, where both humans and nature can flourish in co-existence.

2 Materials and methods

The wider research within which this particular Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) is based involved a partnership with Maati Collective. To understand the discourses produced by marginalised women through alternative media the sample for CDA is drawn from articles and videos produced by members of Maati Collective and published on the website Voices of Rural India (VoRI). The website was founded in 2021 (Himal Prakriti was a co-founder) as a platform for rural storytellers across India to document and showcase the living heritage of communities like Munsiari. The storytellers all come from communities dependent on nature-based tourism, which was severely impacted by the pandemic; VoRI aimed to create additional livelihood sources through digital journalism. The stories here are a way to show another side to tourist destinations – their cultural heritage, and people’s spiritual and material bond with ecologies.

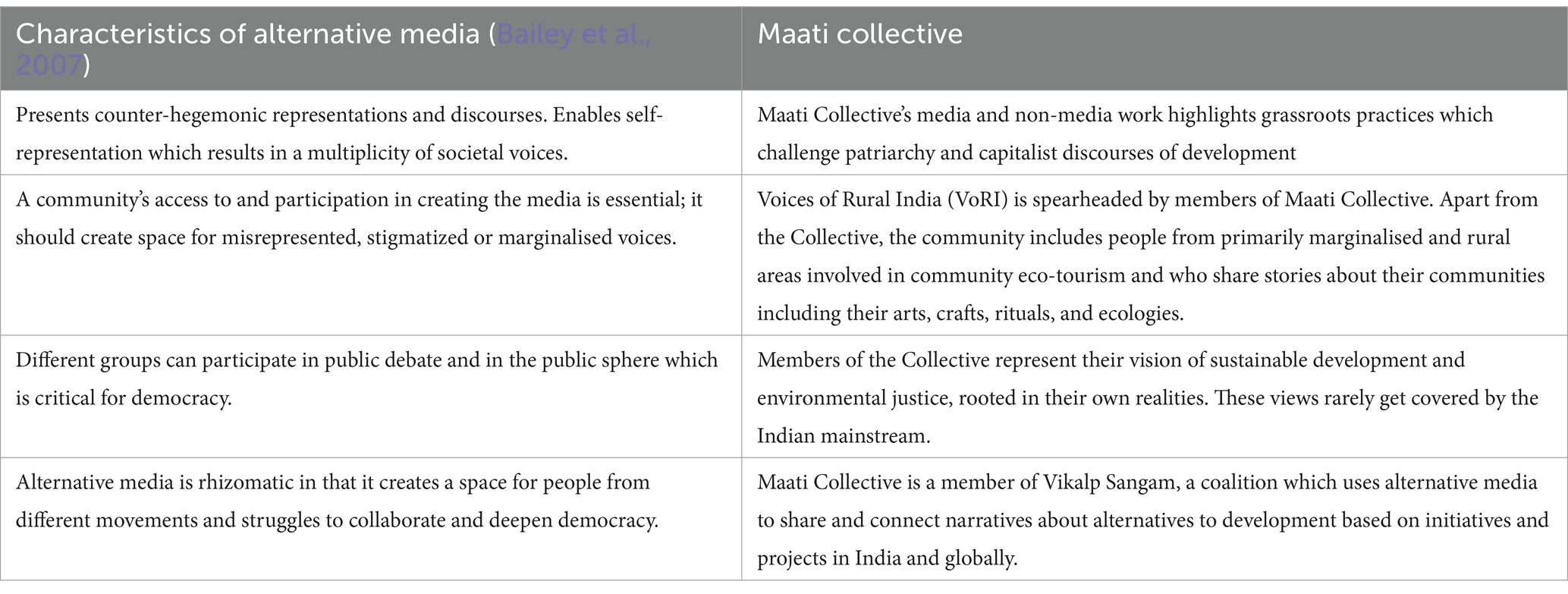

All the Collective’s core members have published at least one article or video on the website. In fact, stories from other parts of India came only in the initial months of the website while members of the Collective continue to publish in a more sustained way. Members of the Collective decide the subject of their story based on their own interest areas and sometimes to feed into other projects being run by Himal Prakriti such as the documentation of folklores about natural habitats. The Collective and VoRI were a good fit for this research because they represent multiple criteria of alternative media platforms as described by Bailey, et al. (2007). They suggest a framework which incorporates a vast number of positionalities to capture the diverse but specific nature of alterative media. I demonstrate these characteristics in Table 1.

I analysed Maati Collective’s work in two ways. First, the CDA this paper primarily draws on. This method is well suited to examine the socio-political contexts that go into the creation of a text and how it is understood and interpreted. The analysis is complemented by eight in-depth interviews and a power analysis workshop that I conducted with members of Maati Collective during two visits in 2023 and 2024. Since this paper foregrounds the CDA, I will focus this methodology section on laying out the contours of Ecolinguistics, a growing field within Critical Discourse Studies which understands how ecology is shaped and imagined through the stories that are told about it (Stibbe, 2014, 2015, 2018). I draw closely on the method as laid out by Arran Stibbe, which I outline in steps two and three below. “The stories we live by” or the popular stories in a culture influence how “people think, talk and act” (Stibbe, 2015) which in turn affects how ecosystems get treated. This connects with how environmental justice movements view storytelling as a means for securing justice as recognition, and what Maati Collective is trying to achieve with their storytelling – to highlight local narratives about alternatives to development and environmental justice.

2.1 Selecting the sample

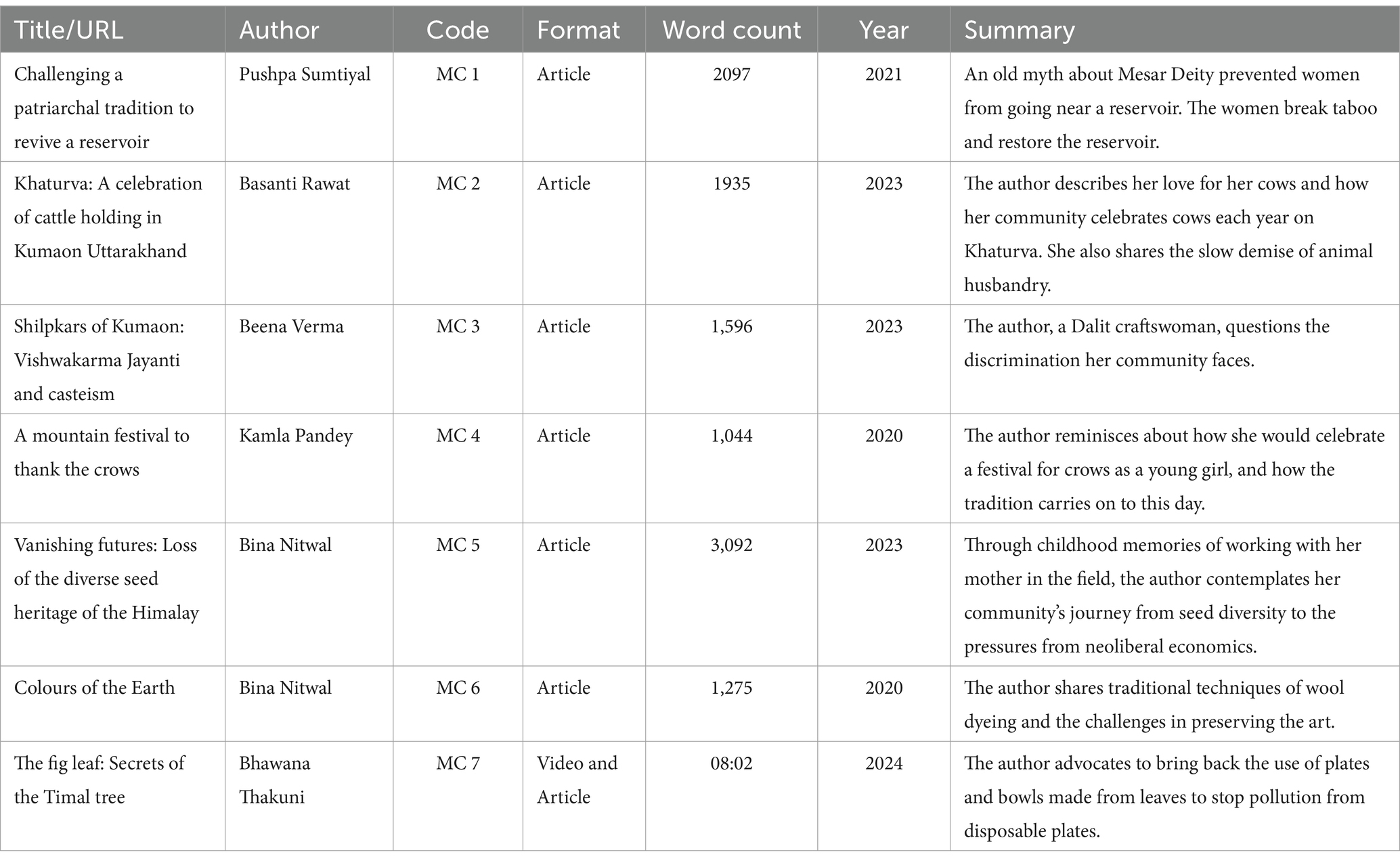

The sample consisted of seven pieces – six articles and one video – which were purposively selected to include one story each from every female member of the Collective. Only one author in this sample has two articles; however, she is the only author who had multiple articles published on the VoRI until March 2024 when the sample was created. Given my focus on women’s use of alternative media, I chose to include media created only by women who were active members of the Collective at the time that I visited them in 2023 and again in 2024. The authors, identify themselves as farmers, pastoralists and weavers. Except one woman in her 20s, the other five are all in their late 40s-early 50s, married and have children. Their years in formal education varied; most had attended high-school, and one completed her bachelor’s degree. The authors belong to the following social groups: Indigenous Bhotiya community, Dalits, land-owning Jimdars, and ‘upper caste’. Limiting the sample size to this specific group provides an opportunity to analyse the stories in depth and understand them in the context of interviews and power analysis with members of the collective. However, I acknowledge that such a selection excludes articles and videos created by the three male members at the Collective, and all the articles produced in communities outside of Munsiari. There is therefore future scope to conduct a wider analysis of media produced on VoRI. Table 2 has a summary of the sample.

2.2 Developing a framework for analysis

Stibbe draws on Fairclough’s (2001) conception of how certain ideas are perceived as ‘common sense’ and in fact uphold unequal power relations. Revealing these ideas for what they are paves the way for social change. Further, ecolinguistics expands the definition of ‘oppressed groups’ that would typically be considered within CDA to include “animals, current generations of humans who are suffering from pollution and resource depletion, and future generations of humans who will find it harder to meet their need” (Stibbe, 2018, pp. 500). In this research I position the dominant discourses about neoliberal development as that perceived common sense, and the discourses produced by Maati Collective serve as a contestation to that. Further, the discourses are produced by people who are impacted by pollution and resource depletion among other environmental injustices.

The task for this analysis is to reveal the specific nature of discourses produced by marginalised women; their own knowledge systems on development and environmental justice. Following Stibbe’s work, my analysis will reveal the ‘stories’ or cognitive models which shape how the women at Maati Collective view their environment. ‘Stories’ can take the form of ideologies; framings; metaphors; identities (what it means to be a specific kind of person); evaluations of something as good or bad; convictions of whether or not certain descriptions of reality are true or false; and erasure or salience which highlight what aspects of life are considered important (Stibbe, 2018, PP 502). For the rest of the paper, I use the term ‘story’ to refer to such cognitive models as they appear in the analysis.

These “stories” are then judged against an ecological philosophy (ecosophy)—a combination of social and ecological values which guide how humans and other organisms interact with each other, as well as an ethical framework of who ‘deserves’ to flourish and why (Stibbe, 2014). Stibbe suggests that each ecolinguist will have their own ecosophy, and following Gavriely-Nuri (2012 in Stibbe, 2014) he suggests that the underpinning values should be made explicit. In the next few paragraphs, I outline my own ecosophy which I use to analyse Maati Collective’s media.

First, I draw on Agarwal’s (1992) idea of Feminist environmentalism which recognises, women as crucial actors in environmental conservation and regeneration movements and a key task is to challenge the dominant groups who control how we think about environmental resources “via educational, media, religious, and legal institutions” (Agarwal, 1992). Feminist environmentalism sees that women’s relationship with nature is governed by gender and class, caste and race; they care because their daily lives (especially in marginalised, rural communities) are linked to it through “production, reproduction and distribution” (Rao, 2023). These relationships are context specific unlike ecofeminism’s view that women have an innate connection with nature.

Second, I draw on Vikalp Sangam’s Alternatives Transformation Format (Kalpvriksh, 2017) which was created to understand what alternatives are and how transformative they are. To qualify as an alternative, the activities, policies, processes, technologies, and concepts/frameworks, under discussion must have the interconnected spheres as a foundation. Alternatives are seen to arise out of a conflict with a neoliberal, exploitative vision of development. It is important to note that though I use the spheres of the Alternatives Transformation Format (ATF) to create my ecosophy and conduct a CDA, their original intention of use was to evaluate alternative initiatives. For instance, Maati Collective’s entire practice could be analysed using this format. In this analysis however, I analyse how the spheres appear as discourses in the stories produced by the women in Maati Collective. The spheres are as follows (Kalpvriksh, 2017):

• Ecological integrity and resilience: Maintaining “eco-regenerative processes that conserve ecosystems, species, functions, cycles, respect for ecological limits at various levels (local to global), and an ecological ethic in all human endeavour.”

• Social well-being and justice: There should be socio-economic and political equity between and within communities in terms of “political entitlements, benefits, rights and responsibilities”; and exploitation, oppression, hierarchy and discrimination on grounds of faith, gender, caste, class, ethnicity, ability, and other attributes are removed from society.

• Direct and delegated democracy: “Decision-making starts at the smallest unit of human settlement, in which every human has the right, capacity and opportunity to take part, and builds up from this unit to larger levels of governance by delegates that are downwardly accountable to the units of direct democracy.”

• Economic democracy: “Local communities and individuals (including producers and consumers, wherever possible combined into one as ‘prosumers’) have control over the means of production, distribution, and exchange (including markets)”; Localisation, equal exchange and commons become key principles.

• Cultural diversity and knowledge democracy: “Pluralism of ways of living, ideas and ideologies is respected, where creativity and innovation are encouraged, and where the generation, transmission and use of knowledge (traditional/modern, including science and technology) are accessible to all.”

2.3 Analysis of discourses

For each article and video analysed, I noted two things. First, I noted how they match up to values of feminist environmentalism. Here I look at the frequency and characterisation of women characters in the stories – were they central or peripheral; what are their roles in the pieces. Secondly, I noted how the pieces match up to elements from the alternatives transformation framework, especially how the different sub themes appear in the articles and video. The articles in this sample were originally written in Hindi and were then translated in English by volunteers working with VoRI; both versions are available online. The video is in Hindi, with English subtitles. I primarily analysed the English versions of the articles and video, but I cross-checked frequently with the Hindi version to make sure the original meaning came through. Where I saw differences in the spoken Hindi and English I made a note of it – though in most cases these changes had not altered the meaning. Where I have done a linguistic analysis, I rely more on analysing the essence of what’s being said rather than breaking components of a sentence. I have also refrained from analysing certain aspects such as ‘passive’ sentences because this is in some ways a quirk of translation. The following analysis then reveals the prominent ‘stories’ that appear in the articles and video along with the degree to which they support or refute the ecosophy laid out in step two. The findings of the Ecolinguistic analysis are supplemented by findings from in-depth interviews and power analysis workshop.

3 Results

3.1 Portrayal of women in the stories

I begin this analysis by revealing the discourses that women from Maati Collective produce about themselves and about other women in their community. This section helps to address the extent to which the assumption holds true that bringing more women into the field of reporting (both mainstream and alternative) adds the marginalised perspectives of women on issues ranging from economies, education, to environmental justice. This section analyses the extent to which the pieces from Maati Collective share the values of feminist environmentalism which recognises, women as crucial actors in environmental conservation and regeneration movements, and acknowledges that caste, class, race amongst other factors influence women’s relationship with nature. These become the cues through which I understand how women as authors position themselves and other women in their community. Within the overall theme of highlighting women’s roles, the two major discourses are that women are memory keepers and that they are experts in their own right. I conclude this section by showing that the prominent ‘stories’ here are of salience, metaphor and identity.

3.1.1 Recognising women’s roles

My conversations with members of the Collective revealed that making the role of women visible in the community is a major impetus for making media and storytelling; a natural extension of three decades of their work on women’s rights. They shared several examples with me about how many women in their community were still hesitant to play major roles in the community. In fact, the women of the Collective stand out in the community in their negotiation of traditional norms of care-work expected of women. Two authors told me that their husbands were teased by neighbours for doing housework while the women went to work.

Of the seven articles analysed, four stories had women as central protagonists of the story; they offered perspectives of multiple women in the community, not just their own. This included Pushpa Sumtiyal’s article about women breaking significant taboos to conserve a local reservoir (MC 1), Bina Nitwal’s two articles about women being central to practices like farming (MC 5) and weaving (MC 6) and Bhawana Thakuni’s video (MC 7) about the many uses of the Fig leaf, including combatting pollution. In three pieces, the authors primarily share their own perspectives and memories on an issue and other women from the community are only mentioned in passing. For instance, in her article about caste-based discrimination of artisan communities (MC 3), Beena Verma writes about one woman politician’s experience but not about women artisans. While writing about a cattle worship festival (MC 2), Basanti Rawat writes about practicing animal husbandry herself but not explicitly about how women in her community look after their cattle, milk them, and feed them. Similarly in MC 4, Kamla Pandey shares her childhood memories of a festival which celebrates crows and only briefly mentions her mother’s role in the celebration.

The women who are in the stories hold a range of social roles and they are shown as actively doing things, rather than passive observers of life. They are political actors (MC 1, MC 3), farmers (MC 2, MC 5), conservationists (MC 1 and MC 6 and MC 7). In three articles and one video, the visuals reinforce women’s roles and depict their daily lives. In the article documenting local grains (MC 5), four photographs show the grains cupped in women’s hands symbolising a connection with the hands that till the fields. In MC 6 we see a woman use traditional wool dying methods and young girls learning the method. In the video (MC 7) not only does Bhawana position herself centrally while appealing to people to use disposable plates made from fig leaves, but she shows other women speaking about how they use fig leaves in festivals and for fodder; other women sing a song about the tree as well. The article about the cattle worship festival (MC 5) has three photos of the author and her cows and four photos of women in the field and offering prayers, establishing their key role even though it is not written about.

One story – “Challenging a patriarchal tradition…” – particularly stands out, as women are shown to shake the status quo:

“But when a woman was elected the sarpanch [head] of the Sarmoli-Jainti Van Panchayat [Forest Council] in 2003, the women of the village came together to discuss amongst ourselves if we could take on the task of reviving the dried-out reservoir.” (Challenging a Patriarchal Tradition to Revive a Reservoir)

Demonstrating that often when one woman is able to gain power, she brings others along with her. In this case (MC 1) the women had been prevented from going near Mesar Kund, the large water reservoir in the village owing to a myth about a local deity. This is the primary source of water for the community. And yet as the water level in it began to reduce, the women (on whom the brunt of fetching water would fall) took steps to restore it. The restoration of Mesar Kund was a landmark moment for the women of Maati Collective as well as for the women in general who are beneficiaries of the forest commons. At the time when the reservoir restoration started in 2003 women were not formally listed as beneficiaries of the forest commons, only men were. Yet, women were the ones primarily engaged in picking small forest produce like firewood, farming etc. The process of women from the village contributing to the laborious restoration process and getting them listed as beneficiaries unfolded simultaneously and were spearheaded by Maati Collective. The article is important in that it documents this historical moment for the community; an official recognition of women’s roles and rights in the forest commons.

This section demonstrates that the ‘story’ here is of salience. Stibbe (2015) calls this a story which considers whether an area of life is worth consideration. And historically, women in India have not been worth consideration. For instance, women make up 42% of the agricultural labour force in India, yet own only 12.8% of operational land holdings (NCAER and CLG Index in The Third Eye, 2021). As authors, the women bring women’s perspectives into consideration and make their opinions and roles visible through storytelling. For Maati Collective this is part of a larger project of claiming their rights to have a say in the management of natural resources and to have a political voice; the most prominent example of this is the story “Challenging a patriarchal tradition…”.

3.1.2 Women as memory keepers

Within the various roles that women are shown to hold, the most common one is their role as memory keepers of their community’s ways of life including of crafts, ritual, and folklore. In four articles out of the seven the authors relate to a folklore or historic fact by referring to what they have heard from their mothers or grandmothers. For instance, talking about a festival which celebrates crows (MC 4), Kamla says the day would end when the children “would gather at home as our mother related the tale of how the Ghughuti festival began.” In her article about caste-based discrimination (MC 3) Beena writes, “Today, there have been many changes in the lives of Shilpkars1, but I remember my grandmother’s stories (about servitude and hardships).”

In one article, women’s role as the primary practitioners of crafts like weaving and wool dyeing is made explicit (MC 6) and reinforced by statements like “I heard stories about natural methods of wool dyeing from my mother.” In this case the author also cautions that the art is getting lost with that older generation of women. Bina writes,

“My mother-in-law was well versed in the art of extracting natural dyes, but most people had begun to purchase chemical colors from the bazaar. After she died, it seemed that using local herbs, plants, and trees to create natural colors was on the verge of disappearing. So about a decade back, I joined the Maati Women’s Collective in our village, to be part of the effort to preserve this local tradition.” (Colors of the Earth)

Another author, Bhawana (MC 7) shares what her grandmother told her about using fig leaves as biodegradable plates,

“In the earlier days, we would sit together on festive and auspicious occasions and prepare ‘pur’ or bowls and plates made of the Timal (Fig) leaves to eat on. Where were there any thalis or disposable plates to be had like today that are now the cause of so much pollution!” (The fig leaf: Secrets of the Timal tree)

In this case the grandmother does not only reminisce about the past but also makes an observation about the increasing pollution in her community; something her granddaughter (Bhawana) attempts to solve by encouraging the use of biodegradable plates through her film. In this case the author is learning about the practice as she films; we see her learning how to make bowls out of leaves.

And in three cases (MC 2, MC 4, MC 5) the authors are documenting their own knowledge and experiences in the form of memories. Here they often invoke childhood memories. For instance, in her article about the loss of diverse seed heritage (MC 5) of her community Bina writes,

“All of us in our village were happy to be there (the fields), both playing and working. I share some of those memories in this story and also wonder- how is it that we got to where we are today [from growing their food to market dependence].” (Vanishing Futures)

The articles analysed here should be seen as systematised attempts at preserving this knowledge and practices for the next generation. The ‘story’ here is of a metaphor – memory and childhoods (especially of women) become ways of signifying a sense of historical continuity in the ways in which women have engaged with practices like farming, weaving and ritualistic aspects of life. Equally, they can signify changes – both good and bad – as seen in the cases of MC 3 and MC 5, respectively. When women are acknowledged as memory keepers, and are central protagonists, the stories document the knowledge systems of the women. We also see how this knowledge was passed on to the next generation – people now in their 40s-50s – who now shoulder the responsibility of passing it on to their children.

3.1.3 An insider-expert perspective

All six authors from Maati Collective narrate in first person, positioning themselves as members of the community rather than outsiders. It is through their memories and observations that the viewer learns about their community. We get a glimpse of their perspectives on the issues they are writing about, including the underlying conflicts in their communities. When referring to conflicts, authors often use rhetorical questions, which encourage the reader to pause and reflect on the conflict. For instance, Pushpa (MC 1) asks whether it is wrong to challenge a custom if it leads to the preservation of their primary source of drinking water:

“If we women took up this work, will we be going against the traditional beliefs, and will that lead to a disaster? But why would Mesar Devta [Deity] be angry with us if we were only saving the source of water and maintaining the site of the Devta? Why would Mesar Devta consider it bad to revive that reservoir? After all, Mesar Devta had fallen in love with two women [This is the belief].” (Challenging a Patriarchal Tradition to Revive a Reservoir)

In another case, Beena forces the reader to confront the rampant caste-based discrimination of Dalit artisans:

“Why are skilled artisans who are involved in various crafts like house construction, bamboo work, goldsmiths, blacksmiths, and woodworking- including the making and playing of traditional instruments, still referred to as a lower caste? In any other part of the world, these artisans are celebrated as artists who contribute to society!” (Shilpkars of Kumaon- Vishwakarma Jayanti and Casteism)

Positioning themselves as part of the community is partly enabled by alternative media’s function of being rooted in community experience. The women demonstrate that their knowledge of practices like weaving and dyeing (MC 6) farming and (MC 2, and MC 5) conservation (MC 1, MC 7) is based on their generational connection with the community and its way of life. For instance, Bina, the author of “Vanishing Futures…” says,

“I used to go to the fields with my mother and work through the day with her. While working, often the sound of melodious songs would drift across the distance, as women working in the fields would sing to keep their spirits up.” (Vanishing Futures)

In her other article, “Colors of the earth” Bina says,

“I was born in the Bhotiya community, widely known for its woolcraft and transhumant lifestyle. My people travelled with their livestock along a fixed migration route, from the plains to the high altitude alpine meadows of Uttarakhand”

The use of a first-person narratives shows that the authors are claiming the identity of experts. Writing about the advantages and pitfalls of first-person storytelling, Sheikh (2019) suggests that this technique is useful to locate the story in a moment or place; it provides the author an opportunity to lay out their positionality; used with other sources it can be an authoritative voice or opinion on an issue. These instances implicitly tell the reader, this is a person rooted in the community and knows what she is writing about because it is her lived reality.

Maati Collective has been the subject of several mainstream media articles about their work in responsible tourism, and the women positioning themselves as experts subverts a dynamic often seen in reporting about them. The articles overwhelmingly credit the success of the homestay initiative and the revival of weaving to the Collective’s co-founder, Malika Virdi (who moved to Munsiari from an urban area) while portraying the rural women as beneficiaries of these processes. For instance, an article in Mongabay says:

“Sarmoli’s journey from a migration-prone village to where it is today took years. It was the consistent efforts of Virdi and the women of the village that brought the change. When she made Sarmoli her home in 1992, Vardi stressed that the village had its share of social evils such as alcoholism, domestic violence and poverty but she realised that these issues would not go away by mere talking. The realisation was followed by the birth of “Maati Sangathan”, a women’s collective, which was formed by Virdi and a group of women in 1994 when they came together to protest against rampant alcoholism that used to lead to severe domestic violence cases.” (Singh, 2021)

The articles written by the members of Maati Collective, complete that picture; they show that projects like the homestays are rooted in their traditional wisdoms and ways of life; that they too know a thing or two about challenging patriarchy (MC 1) and about combating poverty by ensuring food security (MC 5). During our interviews, the women said that their impetus for sharing their own narratives of the work they do and how they challenge the mainstream idea of development partly comes from the backlash they have received for their work with forest commons, protesting a dam, and leading an alcohol ban campaign. They see writing and filming stories on VoRI is the beginning of contributing counter-perspectives to it. None of the women explicitly stated the backlash as an obstacle in telling their stories. However, they said that when they send press releases to local press, they are more likely to get coverage on ‘soft issues’ like their annual festival than about ‘hard issues’ like the botched Van panchayat (Forest Council) election in February 2023.

Seen collectively, the ‘story’ here is about identity; what it means to be a certain kind of person (Stibbe, 2015). The authors are positioning themselves as experts in their fields of knowledge in addition to showing that women like themselves play important roles in their communities. Though I have discussed examples of ‘stories’ of salience, metaphor and identity individually, they should be read as layered upon each other. Simultaneously these ‘stories’ also reveal the degree to which the authors’ views align with the feminist environmentalism ecosophy, I laid out earlier. The articles and video from Maati collective reflect feminist environmentalism to the extent that they emphasise that women are producers and conservers of knowledge and practices as well as organise to protect the environment (Rao, 2023). However, beyond this the pieces do not take a nuanced look at different gender identities. This specific sample does not explicitly talk about how caste or class shape different women’s relationship to the environment they live in nor of how these identities influence their role in its conservation. In the following sections I examine the stories through the ecosophy of the ATF to see what discourses women produce about development and environmental justice.

3.2 Alternatives to neoliberal development

Maati Collective is emphatic that they use their stories to create alternative discourses on development and conservation. This section analyses the extent to which these articles show or aspire to the values that I draw from the spheres of the Alternatives Transformation Format (ATF), which provides the ecosophy the stories are being measured against. The values of the ecosophy become the cues about which discourses on environmental justice and sustainable development are portrayed in these stories. Of the five spheres listed in the ATF, values from three appear most prominently in the sample: Ecological integrity and Cultural Diversity and Knowledge and Economic Democracy. These values are forwarded by ‘stories’ of giving salience to Ecological integrity and Cultural Diversity and Knowledge and of evaluation in the case of Economic Democracy.

3.2.1 Ecological integrity

Ecological integrity, as envisioned in the ATF, refers to “maintaining the eco-regenerative processes that conserve ecosystems, species, functions, cycles, respect for ecological limits at various levels (local to global), and an ecological ethic in all human endeavour” (Kalpvriksh, 2017). Six pieces in the sample explicitly espouse values of ecological integrity as a meta narrative; the only exception is the article, “Shilpkars of Kumaon…” (MC 3) which examines caste-based discrimination. The articles about women restoring Mesar Kund (MC 1); celebrating cattle because of their significance in farming (MC 2); celebrating crows because of an old folklore (MC 4); reviving traditional wool dyeing methods which are chemical free (MC 6); and urging people to stop using single use plastic (MC 7) all further the values of ecological integrity. The article about decreasing seed diversity (MC 5) approaches the value in a slightly different way. It uses the devices of childhood memory and invokes the close links of culture to a farming lifestyle to warn readers of what is being lost. Simultaneously the article also tells readers what Maati Collective are doing to conserve seeds.

In five stories, the value of ecological integrity is forwarded visually as well. The images accompanying articles act as devices to establish the landscape of the region. We see long shots and close ups of corn fields, black barley fields, step fields of mustard in different articles. The Panchachuli peaks, a defining visual feature of the skyline, are often in the background. Given that the pieces often describe conflict over access to resources (MC 1 and MC 3); the changing value systems towards nature (MC 2) and a loss of ways of life owing to the imposition of neo-liberal economics (MC 5, MC 6), the images are establishing a story of salience. That these ecologies are rich with a diverse range of flora and fauna; a visual representation of what could be lost without conservation.

Within the overarching theme of ecological integrity, the stories depict further nuances of co-existence with nature, and of sustainable use. We see co-existence explicitly in two articles in how people refer to animals. This relates to what Stibbe (2015) calls an eco-centric view where both nature and humans are given equal consideration in discourses, in contrast to an anthropocentric view which puts humans above nature. In MC 4 the Kamla tells us how crows are fed to thank them. While talking about the Khaturva festival (MC 2) where cows are celebrated, Basanti shares her own relationship with her milk cows.

“My cows are as dear to me as my own children. I still remember the names of those first four cows –Dhauli, Kali, Ratuli, and Furkuli… When you spend a large part of your day with these animals, you tend to develop a special attachment to them.” (Khaturva- A celebration of cattle holding in Kumaon)

The sustainable use of resources is referred to explicitly in two pieces (MC 5 and MC 7). The film about fig leaves (MC 7) explicitly espouses the value of sustainability by reminding viewers about the once-ubiquitous plates and bowls made of leaves should be brought back. Across India, these were a crucial part of any community food event until disposable plastic and Styrofoam plates became popular in the late 1990s. Further, we see in the below case how every part of a plant is used for different things. Whilst talking about the diminishing seed diversity in the farming practices of her community (MC 5), Bina shows the prevalent elements of sustainability.

“Sarsoon (Yellow Mustard and Black Mustard) is cultivated extensively for our edible oil needs. We also cook a saag or vegetable dish with its green leaves. After extracting mustard oil from the seeds, the oil cake residue is fed to our cows and buffaloes.”- (Vanishing Futures—Loss of the diverse seed heritage of the Himalay)

The ‘story’ here is of giving salience to co-existence within the eco-system. Humans are part of nature and are not ranked as more important than it. By mentioning livelihoods based on cultivation (MC 5) and animal husbandry (MC 2), wool craft (MC 6), and by seeking its conservation (MC 1, MC 7) these stories suggest that dependence on natural resources should make the humans in the equation seek justice for these by protecting them from damage. Further, they suggest that alternatives do exist to capitalist forms of development with an anthropocentric view. In the context of ongoing socio-environmental conflicts in the community the pieces highlight community perspectives on environmental justice and sustainable development. In the next section I examine a parallel aspect of this relationship of ecological integrity – the spiritual practices which enmesh the two together. I discuss this in the wider context of the theme of cultural diversity seen in the articles.

3.2.2 Cultural diversity and knowledge democracy

Six pieces espouse the value of cultural diversity and knowledge democracy either overtly or as an underlying theme. In the ATF this value aspires to societies where pluralism of ways of living, ideas and ideologies is respected, creativity is encouraged, and knowledge is accessible to all. I identified three sub themes in the stories: 1) a spiritual basis for human-nature relations; 2) questioning some aspects of culture; 3) and of nature’s imprint on language and art. I cover these one by one in the following paragraphs.

The spiritual basis for human-nature relations is seen in three articles. The article, “Challenging a Patriarchal Tradition to Revive a Reservoir” (MC 1), shares the folklore about the deity associated with the local reservoir. Pushpa writes, “Mesar Kund (a forest pond) is the abode of Mesar Devta (deity) and is situated in the middle of the forest.” In all three cases the authors (and communities) situate local folklore as the source of present-day reality. In case of the Mesar Kund, the folklore blames one community from a neighbouring village for the reservoir’s deterioration2. Here the author brings the two parallel worlds together but sifts belief from fact.

“In the last two decades, there has been a new twist in the story of Mesar Kund. It used to be a huge pond, which began drying up. The belief is that the Barnia people are responsible for its drying up, but it is clear that the erosion and denudation of the slopes above the kund has caused the pond to dry up. All the big trees are gone and there is no new regeneration because of grazing cattle.” (Challenging a Patriarchal Tradition to Revive a Reservoir)

The ‘twist’ in the original folklore is of actual present-day damage being done to the reservoir by the loss of tree cover and excessive grazing. She alludes that the facts are obfuscated by people (possibly those who profit from tree cutting) by relying on the age-old myth.

Simultaneously, we see that nature is celebrated and venerated in recognition of its value in daily life. While writing about Ghughuti, a festival which celebrates crows (MC 4), Kamla explains that the festival’s origins are in a folklorewhere crows rescue a young prince and the royal couple throw the crows a lavish feast in gratitude. Writing about another festival, Khaturva (MC 2) Basanti writes,

“Cattle has a special significance in the life of us mountain folk. The farmyard manure and compost we apply to our fields, the milk and curd we give to our children– we get all of this from our animals. I believe that we celebrate our cows because they are not just a source of livelihood for us, but it is a way of expressing our love and gratitude towards them.” (Khaturva- A celebration of cattle holding in Kumaon)

In all three cases the existing spiritual links to nature are strengthened by ceremonies which acknowledge the gifts of food, fodder and a protection. Simultaneously some leaves and grains are considered sacred because they are used often in religious ceremonies. Some festivals mark a change in seasons, and local wisdom for the health of the animals is expressed through cultural beliefs. Because Khaturva (MC 2) marks the beginning of winter and the grass starts to dry out, the author writes, “That is why we cut a lot of grass for our cows a day before, and cutting grass on the day of Khaturva is considered inauspicious for the cows.” Similarly, in MC 5, Bina says, “The popular belief is that after Hariyali (the day in the month of July considered auspicious for planting), when standing crops begin to ripen…” The end of one phase in farming is termed ‘inauspicious’ and the beginning of a new phase is “auspicious”.

Despite the importance of culture in these communities, aspects of culture and tradition which cause harm to nature or result in discrimination against a group, are resisted and questioned by the authors explicitly in two articles (MC 1, and MC 3). Coming back to the case of Mesar Kund, the women started preserving the reservoir after challenging taboos based on the Mesar Devta folklore which prevented from women being near the reservoir. The author, Pushpa, writes that prayers are still offered at Mesar Kund every year, but in the last 15 years they have taken on a new form of celebration and veneration of this source of water. It has also become an occasion to celebrate the local food and music and of awarding locals who make great contributions towards conservation in the area. Similarly, the article “Shilpkars of Kumaon…” (MC 3) explicitly calls out caste-based discrimination of the Shilpkar community. The author, Beena, uses the devices of memories and rhetorical questions to show that while progress has been made, the community are prevented from leading respectful lives. Seen together, the stories expand the concept of “who is within the domain of justice” (Jamieson, 2007)—in the case of Mesar Kund and Shilpkar stories it is women and Dalits, respectively.

A third theme within cultural diversity is nature’s imprint on language and art. Five out of seven stories (MC 1, MC 2, MC 4, MC 5, MC 7) showcase a rich vocabulary for seasons, months, seeds, and animals. For instance, in many of the stories the authors use local names (not Hindi ones) for grains and trees – Chuwa for Amaranth; Munna for millet; Timal for Fig. Seasons and months are named based on the Hindu calendar rather than the Gregorian calendar. In the article “Vanishing Futures…” (MC 5) we see many examples of how characteristics of grains make them the root of proverbs. Bina writes,

“There is also a saying in our village that describes what happens when we put Chuwa (Amaranth) in a hot pan and roast it, and how it splutters with a sound that goes- ‘Charar charar charar’. That is why when someone speaks in anger, they compared to roasting Chuwa and as the expression goes- “What a noise you make, just like the Chuwa!”

Similarly in the article “Colors of the Earth” (MC 6) the author, Bina writes about in the process of reviving natural wool dying, they also made new designs for the carpets they weave. She says that “To preserve our Indigenous art and knowledge, we started creating both old and new designs using natural herb-based dyes. The aasans [carpets] we made depicting the birdlife of Munsiari became sought after by travellers…” Nature is shown as a muse in this case.

The ‘story’ here is of giving salience to the human-nature relationship and a ‘story’ of evaluating certain traditions that are discriminatory and against justice. Stibbe (2015) suggests that using specific words, instead of stock words (or in this case the equivalents) like ‘flora’ fauna’ ‘species’ gives salience to the aspect of nature being discussed. In turn, the salience reflects a connection to nature and shows that the author sees value in the element. The readers too can visualise what is being spoken about. Ecology also shapes elements of language by creating what are called sense images (Stibbe, 2015). Here the author creates a clear image for a reader by describing the natural element’s effect on senses. Macfarlane (2015) similarly writes that people connect with a landscape intimately when they use specific language to describe it while landscapes with generic descriptions are more prone to being damaged.

3.2.3 Economic democracy

Four pieces talk about the value of Economic Democracy, which the ATF describes as “Local communities and individuals (including producers and consumers, wherever possible combined into one as ‘prosumers’) have control over the means of production, distribution, and exchange (including markets).” The authors present an implicit critique of a dominant neo-liberal economic model because they result in the loss of ways of life; once small economies based on prosumers, and which depended on the nature around them for livelihoods.

These four pieces focus on how people have reduced or completely stopped traditional practices like farming (MC 5), animal husbandry (MC 2) and weaving (MC 6) because they can now easily buy things from the market; the video talks about growing pollution (MC 7). For instance, people have stopped growing crops like some species of kidney bean because there is not a demand for it in the market. While speaking about animal husbandry, Basanti (MC 2) writes,

“Four decades back, all the houses in our village kept cows and buffaloes. In those days, a cowherd was hired to take the cows out to graze in the village forest… Today, very few people in the village take their animals to the forest and no one works as a cowherd. Animal husbandry has reduced, milk is bought from market dairy and farming has also taking a beating.” (Khaturva—A celebration of cattle holding in Kumaon)

It is not just a matter of buying milk from the market, the author points out that there is a knock-on effect on agriculture too since cattle are a primary source of manure. So, if there are no cattle, there is no manure, and there is no agriculture – it potentially wipes out an entire way of life. In her article “Vanishing futures…” (MC 5) Bina elaborates on this theme,

“Farming was both our way of life and our source of livelihood. At that time, we did not depend on the market for food, rather we used to grow food for the whole year from our agricultural fields. We bought soap, sugar and tea and few basic necessities from the market and grew all our food grains.” (Vanishing Futures—Loss of the diverse seed heritage of the Himalay)

Both authors here suggest that farming or keeping cattle are not just things people do, they are a “way of life.” Framing the situation in such a way demonstrates a complex web of activities, and human relations involved. It is a powerful message to the reader that this way of life is distinct from say, a capitalist order based on market dependence. We see another element of this way of life in the story “Colors of the Earth” (MC 6) where the author, Bina, writes about how natural wool dyes were replaced by artificial colours which need acid (harmful to humans and the environment) for the fixing process.

“My mother-in-law was well versed in the art of extracting natural dyes, but most people had begun to purchase chemical colors from the bazaar. After she died, it seemed that using local herbs, plants, and trees to create natural colors was on the verge of disappearing. So about a decade back, I joined the Maati Women’s Collective in our village, to be part of the effort to preserve this local tradition.” (Colors of the earth)

These articles show both a sense of loss as well as the reserve to stem the loss. They show that communities and organisations are making genuine attempts to keep alive certain practices. During COVID-19, Maati Collective conducted workshops about making natural dyes with young people in the village, to get them interested in the art. The conflict with a market-based economy also brings about a conflict with pollution, as pointed out in the film, “The fig leaf…” (MC 7).

“I believe that not only the Timla leaves, but the many broad leaves to be found in our forests and village can be made into pur (plates) and bowls to eat food on at large events. This would reduce the unsightly garbage heaps caused by the extensive use of disposable plates”—(The Fig Leaf- Secrets of the Timal Tree)

The author talks about the need for biodegradable plates whilst sitting beside a heap of garbage in the forest adjacent to her village, showing the scale of the problem. The story shows a conflict in terms of waste management – who bears the brunt of excess pollution (the community) and whose responsibility is it to clean up the waste. Simultaneously, the film shows that with the onslaught of things from the market, the coming generation might lose the knowledge about their local flora and fauna. The film starts with a vox-pop, asking children if they have seen what a Timal tree is. Only one out of five children says a confident yes; the others seem unsure or have not at all.

The implicit conflict seen in these articles is largely between a neo-liberal/market economy impinging upon rural way of life which has been very rooted in its land and by and large based on sustainable practices. The members of Maati Collective and many in the village prefer the latter. While there are likely to be different opinions about the degree to which their ‘traditional’ way of life should continue, these are not shown in the articles. The pieces here are part of a larger story playing out in Munsiari, which women spoke about in our interviews. When I visited, the area was categorised as a rural community and therefore governed by village councils, and this gave the community specific access rights to their forest. Following an administrative push, this area was turned into a municipal council in 2024, removing forest access rights. During interviews the women said that they are often excluded from important meeting about these issues because their views are seen as troublesome to the establishment. Members of Maati Collective are now engaged in other forms of direct action, such as establishing a tourism committee which, though not officially recognised, might be able to advocate for the continued protection of the forest commons. Bina, in her article, “Vanishing Futures…” sums up the contestation between the old and new most succinctly:

“To be provided with basic civic amenities, it is not necessary to make the villages into a peri-urban settlement or Nagar Panchayats. As citizens of the state, are villagers not entitled to basic facilities? We all need a good hospital, school with staff and good roads. If this is assured, we as mountain people should continue with our agrarian tradition, with the active support of our governments, and keep these seeds and crops from disappearing. The key to our food sovereignty, security and future of the Himalaya is to keep this wisdom from vanishing from our lives.” (Vanishing Futures—Loss of the diverse seed heritage of the Himalay)

She uses a rhetorical question forcing the reader to think about the “basic facilities” her community wants. She simultaneously negates the false narrative of development which assumes that a community will give up its ways of life if they get access to roads, hospitals, and schools. By explicitly naming the need for “active support of our governments” she also alludes to the fact that there are powerful forces – neo-liberalism – which prevent their way of life from continuing.

The pieces touch on themes we spoke about during our in-person conversations; the issues that the Collective has worked on for thirty years. For instance, members of the Collective have gone on strike demanding teachers for the local school and gynaecologists for the local health centre. Simultaneously, the Collective’s work is related to keeping many aspects of their “way of life” alive, including the revival of crops like millet and black barley again. In fact, in 2021, the white Kidney Bean that is local to Munsiari was given a Geographical Indicator Tag and Intellectual Property Recognition for the state of Uttarakhand. This is an encouragement to farmers (and readers as well) that market/profit logic should not be the sole factor dictating practices. A significant strategy in keeping their way of life alive is to engage in making their culture visible to the next generation and to the wider community. Recently Maati Collective has been showing the films they make at local screenings. They have also published a book so that members of the community who would not usually go on a website like VoRI can read the stories. The idea behind these strategies is to celebrate their culture to re-invigorate the need to protect it.

They have also formed an eco-tourism/homestay cooperative. The premise of the homestay is to invite tourists in the area to come and get a glimpse into the traditional rural way of life such as their food, showing them their day-to-day lives including weaving and farming, and by showing them the nature in the village. The success of their homestay model has encouraged people from neighbouring areas, including the Munsiari market area to cater to tourists. Recognising that tourism itself will lead to a strain in natural resources like water, and lead to pollution, the Collective has been a part of extensive studies on ‘tourism-carrying capacity’ and have been trying to engage other stakeholders of the local tourism industry with mixed success.

The ‘story’ here is about an evaluation about the state of flux where ways of life that are rooted in sustainability are giving way to a dependence on market economies. In no way do members of the Collective or wider community advocate for the complete removal of the ‘market’ from the equation; the argument is more along the lines of regulating ‘growth’ or the use of markets to allow for certain sustainable traditional ways of life to thrive, aligning with the ATF’s conception of economic democracy. When read along with how women articulate the values of ecological integrity and cultural diversity and knowledge, we can see that these pieces from Maati Collective support the ecosophy of the ATF. On one hand the authors give salience to the co-existence of humans and nature, and of diverse cosmologies and practices; on the other hand, they evaluate the existing economic ‘story’ as a bad one. Instead, they make an explicit case for continuing their practices which ensure sovereignty, food security and environmental health.

4 Discussion and conclusion

This small sample of stories produced by women in a Himalayan community illustrates the discourses that marginalised women produce about sustainable development and environmental justice through alternative media. This paper highlights two aspects of these discourses: first the discourses that women produce about themselves and other women from their community. Second, the specific discourses about development and environmental justice. In the following section I summarise the findings and discuss their implications.

In these articles and video, the women use the affordance of alternative media in enabling typically unheard groups position themselves as experts of their lived reality. The articles and video showcase a deep, historical link between women, their ecological knowledge and their cultures – about the use of certain plants and grains for illnesses and daily household uses; of practices that allow the land to regenerate naturally; about farming practices that enabled food security. Maati Collective’s media is a systematised attempt at preserving this knowledge and practices for the next generation in the context that these are now threated by climate change, ecological degradation and an increasing dependence on markets. The pieces here evidence feminist environmentalism in practice by establishing that women’s relationship with nature is based on how they engage with it in their daily lives – growing food, fetching water, tending the cattle, etc. This in turn shapes the roles women play in producing and conserving knowledge and practices as well as is an impetus to organise themselves to protect the environment (Rao, 2023).

The discourses about women’s vital roles are counter narratives to how women are viewed (rather, unseen) in dominant discourses of development and environmental justice. The pieces subvert the denial of their expertise in both, decision-making arenas and in media produced about the Collective by others. Over three decades Maati Collective has advocated to make women’s roles visible and simultaneously ensured they are named as rightsholders to the forest commons. Their media making is an extension of this process. If women’s roles are made explicit through documentation, they could have wider implications in terms of official recognition and access to rights. This claim to expertise is directly linked to justice as recognition (recognition of marginalised local knowledge of women and of Indigenous communities) and of participation (who gets to have a say in decision-making).

I now turn to the specific discourses women produce about development and environmental justice. The selected sample furthers three values of Ecological integrity and Cultural Diversity and Knowledge and Economic Democracy from the ATF. The authors make the importance of ecological integrity visible through their livelihoods deeply enmeshed with nature – cultivation, animal husbandry, wool craft. The pieces here also demonstrate that the community’s religious, spiritual and artistic expressions interlink nature and humans and sanction their protection. By seeking conservation these stories suggest that dependence on natural resources should make the humans in the equation seek justice for these by protecting them from damage. Further, aspects of culture and tradition which cause harm to nature (pollution) or result in discrimination against a group (women and Dalits), are resisted by the authors. Finally, the narratives highlight how the dominant neo-liberal economic model is diminishing their existing ways of life. Instead, they make an explicit case for continuing their practices which ensure sovereignty, food security and environmental health.

This section particularly demonstrates that the women are actively countering the dominant views on development and environmental justice. By showing the viewer their lives and livelihoods they make the case that alternatives do exist to capitalist forms of development with an anthropocentric view. Just the fact that conflict exists at the intra-community level and with the state means that communities are not passively accepting a neo-liberal vision of development. They are using alternative media as a means to air out these conflicts. In the context of ongoing socio-environmental conflicts in the community, the pieces highlight community perspectives on environmental justice and sustainable development. Through alternative media the women have been able to forward their goal of justice as recognition—of diverse worldviews, of marginalised knowledge systems.

I began this article by asking whose voices are we listening to in conversations and debates about environmental justice and sustainable development. Maati Collective and VoRI’s practices highlight that when given the platforms, women produce discourses with unique worldviews; they create “counterpublics” (Fraser, 2007) to establish competing and unrecognised claims to environmental justice. The question remains about how far these voices are heard. There is a need to comprehend the interplay between mainstream and alternative media because the remaining issues of poor visibility are because of the “reality effects” (Pleyers and Suzina, 2016)—the ways in which certain social groups are characterised and represented and therefore the dominant imagination about them. This means that ultimately even the movements who use alternative media must rely on heavy visibility tactics to get mainstream attention.

In its initial moments VoRI was able to capitalise on mainstream platforms. For instance, after VoRI was launched, leading papers and magazines including The Caravan and Conde’ Nast India wrote celebratory articles about the concept of opening up journalism and storytelling to rural communities. An early batch of stories published on VoRI were also published as a special print edition of Outlook Traveller Magazine, which calls itself India’s number one travel magazine. Re-iterating what some members of the Collective said in their interviews, it could be that this celebration comes down to way these stories are written – sharp critiques disguised in a celebration of their culture. It would be important to see through further research whether the Collective’s stories manage to break into mainstream spaces, especially publications with historically antagonistic views about marginalised communities and environmental justice.

The transformative potential of such media lies in the fact that the Collective (and the wider alternative media movement in India) are in the process of breaking the hegemony of who can tell their life stories or do journalism. For Maati Collective, the act of doing so involves overcoming significant power asymmetries in terms of entrenched views about what women can and cannot do; about learning how to navigate platforms in a relatively alien language; about who has the resources to start and sustain alternative media initiatives. Significantly, producing such narratives involves re-learning to have faith in their own voices which have been so-often dismissed. And when these voices start being heard there are wider implications for expanded civic spaces and for securing democracy, in the sense that their articulation of their concerns, and self-representation present cornerstones of claiming citizenship (Livio, 2017; Saeed, 2009). In the case of Maati Collective this can be seen in the everyday acts of resistance to an imposed form of development by actively preserving their ways of life. The resistance is both in doing and documentation of it. Bringing women’s personal narratives into the public, should be seen as a political act.

By examining the communicative practices of Maati Collective, I demonstrate that alternative media and environmental justice movements have similar goals in terms of enabling access to a full spectrum of justices – distributive, representative and participatory. Maati Collective’s media ‘give voice’ to the environment because of their rootedness in location (Foxwell-Norton, 2015). These authors demonstrate that the contestation of the current hegemonic view of development from grassroots communities is based on lived experience, and therefore should not be dismissed by the establishment. The collection of stories provide evidence that other ways of knowing can result in a more sustainable and just way of development, where both humans and nature can flourish in co-existence.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by School of Global Development Research Ethics Subcommittee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

KK: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AH/X003442/1) as well as by a Postgraduate Studentship from the School of Global Development, University of East Anglia.

Acknowledgments

This paper would not have been written without the stories first told by the women at Maati Collective. My deepest gratitude for inviting me to stay with you, and enabling me to learn from you, for allowing me to ask many questions and for being fierce defenders of the unique lives you have created.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction note

A correction has been made to this article. Details can be found at: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1670525.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Dalit craftsmen from a collection of different sub-castes who do artisanal work. They are categorized as Scheduled Castes in Uttarakhand.

2. ^The folklore is that the Mesar Deity took two Barnia cowgirls into his universe because he fell in love with them. The Barnias tried to get them back, the Deity got angry when they did not accept his bargain of gold, and eventually sent back the lifeless bodies back to earth. The Barnias got condemned to die out for distrubing the deity and ruining the reservoir. Until recently women were not allowed to go near it.

References

Agarwal, B. (1992). The gender and environment debate: lessons from India. Fem. Stud. 18, 119–158. doi: 10.2307/3178217

Bailey, O., Cammaerts, B., and Nico, C. (2007). Understanding alternative media. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education. ProQuest Ebook Central.