- Department of Communication Science, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Singaperbangsa Karawang, Karawang, Indonesia

This perspective article examines the ongoing debate surrounding the Indonesian Ulema Council’s (MUI) fatwa on interfaith greetings, highlighting tensions between religious purity and social tolerance in Indonesia’s pluralistic society. It traces MUI’s position from its 1981 fatwa prohibiting greetings such as Assalamu’alaikum, Shalom, Om Swastiastu, Namo Buddhaya, and Salam Kebajikan to continued discussions in the 2000s and 2020s. The Ministry of Religion (Kemenag) has promoted religious moderation as a means to balance religious diversity and national unity, presenting an alternative stance to MUI’s prohibitive approach. Using Ting-Toomey’s Negotiated Identity Theory, this article explores how religious identity is shaped by social interactions and adaptation within multicultural settings. The negotiation of religious identity in Indonesia is particularly complex, as religious groups must reconcile theological principles with the realities of coexistence. The article emphasizes the need for open dialogue and collaboration between religious communities to foster mutual understanding. While some perspectives strictly adhere to MUI’s fatwa, others advocate for contextual consideration, recognizing the influence of diverse cultural and educational backgrounds. The discussion highlights differing interpretations of religious teachings and the socio-political dynamics that shape this discourse. Ultimately, this article advocates for a balanced approach—one that respects religious traditions while fostering social cohesion. By promoting inclusivity and mutual respect, Indonesia can cultivate a harmonious society where interfaith relationships are nurtured, ensuring that diversity becomes a source of unity rather than division.

1 Introduction

The fatwa issued by the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) regarding the prohibition of interfaith greetings has sparked significant controversy and attention from various groups. This is because such greetings have become a common practice in Indonesian society, even during official state events. According to the MUI fatwa commission, greetings are seen as a form of prayer and carry religious significance, making it inappropriate to mix them with greetings from other religions. The polemic surrounding interfaith greetings has therefore become a hot issue in Indonesia, with the MUI firmly supporting the ban. However, this debate goes beyond the technical aspects of the greetings themselves. It also touches upon the broader issue of the sustainability of multiculturalism in Indonesia (Jati et al., 2022).

In the public sphere, religion must play a more active role in providing a foundation and ethical orientation for a fair, tolerant, and open coexistence (Indainanto et al., 2023; Muhaemin et al., 2023; Muhammad, 2021). However, as demonstrated by Noviandy et al. (2023), religious diversity does not necessarily lead to greater acceptance of pluralism. Instead, the presence of multiple religious groups may intensify social contestation, where public space becomes an arena for asserting competing religious identities. Religions that focus too much on protecting symbols and rituals may end up creating division and engaging in trivial quarrels over narrow, short-term interests, while the fundamental responsibilities of achieving justice, fraternity, and peace are neglected. This debate also highlights the differing opinions among Muslims themselves. The Ministry of Religious Affairs, for example, offers a contrasting view, suggesting that interfaith greetings are a means to encourage harmony and have no adverse effect on faith (Singgih, 2023). These greetings are simply a form of acceptance and respect for diverse realities.

The MUI fatwa prohibiting interfaith greetings is based on Islamic legal principles that emphasize the purity of faith and worship. From a fiqh perspective, greetings in Islam are not merely social expressions but are part of prayers with deep spiritual significance. The greetings conveyed hold the meaning of a prayer directed to God in each respective religion. Therefore, MUI refers to theological arguments, such as the hadith of Prophet Muhammad SAW, which establishes boundaries on giving greetings to non-Muslims (HR. Abu Dawud), as well as the principle of sadd al-dzari’ah (preventing potential deviations in faith). Additionally, this fatwa is also based on Q.S. Al-Kafirun: 6, which emphasizes the separation of worship practices between Muslims and adherents of other religions. From a legal standpoint, although the MUI fatwa does not have binding legal authority, it is often used as a reference by Muslim groups in shaping social and religious practices in Indonesia. For example, the greeting Assalamualaikum warahmatullahi wabarakatuh means “may peace, mercy, and blessings from Allah be upon you.” Om Swastiastu means “may you always be in a state of safety by the grace of Hyang Widhi.” Meanwhile, Namo Buddhaya means “praise be to the Buddha.” In Confucianism, De dong tian means “only goodness can move Tian (God).”

However, this difference in opinion is part of a larger debate that concerns the future of multiculturalism in Indonesia. While the MUI views interfaith greetings as prayers inseparable from worship thus prohibiting the use of God’s name in other religious contexts the Ministry of Religion considers them a means of fostering religious moderation and tolerance. This disagreement reflects the ongoing challenge of maintaining and strengthening Indonesia’s multicultural identity (Thohir and Lukluk Atsmara Anjaina, 2022).

In this context, it is crucial to recognize that interfaith greetings are not merely a technical matter of language use but are deeply connected to broader issues of interreligious harmony and social cohesion. Given the diverse backgrounds, cultures, and theological perspectives within MUI and Indonesian society at large, reaching a common understanding requires continuous dialogue and mutual respect. Therefore, an inclusive and open discussion must be encouraged, not only to bridge differing interpretations but also to establish a sustainable framework that respects religious traditions while promoting peaceful coexistence in Indonesia’s pluralistic society.

1.1 Interfaith greetings in the practice of building tolerance

Interfaith greetings are a practice in which a person gives greetings that contain elements of various religions, with the aim of showing tolerance and respect for religious diversity in Indonesia. For example, in official events or activities involving various religious believers, the delivery of greetings such as “Assalamu’alaikum, Shalom, Om Swastiastu, Namo Buddhaya, and Salam Kebajikan” is often done as a form of respect for all religions present. However, this practice sparked controversy among religious groups. As an influential religious authority in Indonesia, the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) issued a fatwa prohibiting the use of aith greetings by Muslims. According to the MUI, interfaith greetings are considered to violate Islamic teachings because they are special and sacred prayers, which should only be addressed to fellow Muslims. The use of greetings from other religions is considered damaging to the faith and beliefs of Muslims. With a constructive and collaborative approach, it is hoped that Indonesia will find the right formula for managing religious diversity, where the purity of religious teachings can be maintained without sacrificing the values of tolerance and social harmony (Indainanto et al., 2023; Pangalila et al., 2024). Only with an inclusive and mutually respectful middle way can the sustainability of tolerance and harmony between religious communities in Indonesia be maintained and strengthened.

However, the Ministry of Religion of the Republic of Indonesia (KEMENAG) has a different view. The Ministry of Religion implements the concept of religious moderation as an effort to create a tolerant, inclusive, and harmonious religious life (Suntana and Tresnawaty, 2022; Daheri et al., 2023; Rusyana et al., 2023). Religious moderation teaches religious people to be middle-of-the-road, not extreme in understanding and practising their religious teachings and respecting differences in beliefs. According to the Ministry of Religion, interfaith greetings are a form of religious moderation and tolerance among religious communities. This practice is considered important in building good communication and reducing the potential for conflict between religious communities. Interfaith greetings are also seen as a form of appreciation for diversity in Indonesia as well as strengthening the spirit of national unity and unity.

1.2 The recurring polemic of interfaith greetings

The polemic surrounding interfaith greetings in Indonesia is not a new issue; rather, it is a recurring debate that has emerged repeatedly alongside the social and religious dynamics within society. Each time a fatwa or regulation regarding interfaith greetings is issued or debated, society is once again divided between those who support and those who oppose it. This issue resurfaces in various contexts, whether in public discourse, religious education, or mass media, with each side presenting arguments about the importance of protecting the purity of religious teachings and fostering better interfaith relations. This creates tensions that often lead to social polarization within Indonesia’s pluralistic society.

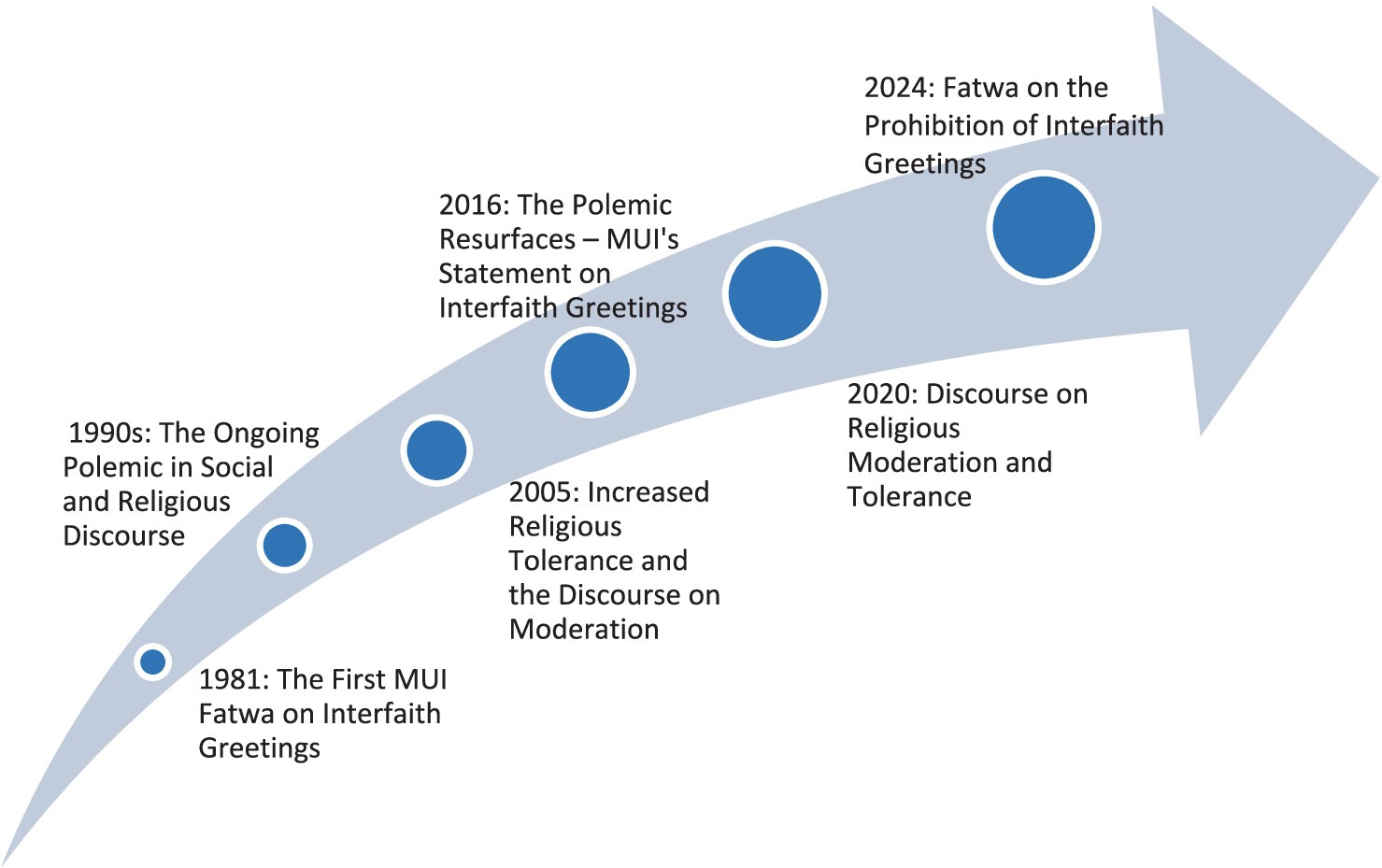

Figure 1 illustrates the journey of the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) in opposing interfaith greetings. It began with the first fatwa in 1981, which prohibited greetings like “Merry Christmas” and “Om Swastiastu,” arguing they conflicted with Islamic teachings. Despite the controversy, MUI maintained its stance, even as religious moderation discourse emerged in the early 2000s. In 2016, the debate resurfaced amid government efforts to promote religious tolerance, but MUI continued to uphold its prohibition. In 2024, MUI issued a similar fatwa, reflecting the ongoing tension between preserving religious purity and fostering tolerance in Indonesia’s pluralistic society.

Figure 1. Timeline of the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) fatwa on interfaith greetings: a journey of controversy and debate from 1981 to 2024.

At its core, this polemic revolves around two conflicting understandings. On one hand, some argue that interfaith greetings are a form of respect for diversity and a means of fostering unity in a multicultural society. On the other hand, some groups view it as a practice that dilutes religious identity and may lead to syncretism, which is seen as contrary to their faith. The tension between these two perspectives often leads to endless debates, creating divides among religious communities in Indonesia (Parhusip, 2024).

Although this polemic is recurring, it is important to note that each time the issue arises, new dynamics emerge, whether from religious, political, or socio-cultural perspectives. This shows that the debate over interfaith greetings is not just a matter of technicalities or rituals, but is deeply tied to religious identity, national values, and the understanding of tolerance. Therefore, it is crucial to delve into the roots of this polemic and attempt to find a middle ground that can strengthen interreligious harmony without compromising the authenticity of each belief.

2 Methodology

This study employs a comprehensive qualitative approach, utilizing literature review, media discourse analysis, and empirical case studies as its primary data collection methods. The literature review examines a range of academic sources, including scholarly journals, books, and policy documents, which pertain to the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) fatwa on interfaith greetings and the broader theme of religious moderation as advocated by the Indonesian Ministry of Religious Affairs (Daffa, 2023; Yusuf et al., 2023). Specifically, this review considers the relevance and application of the Abu Dhabi Document in Indonesia’s religious moderation narrative, as well as the framework within which the Ministry of Religious Affairs has formulated its policies (Daffa, 2023). These references provide a contextual backdrop for understanding how religious moderation operates within Indonesia’s socio-political and policy landscape (Yusuf et al., 2023).

In addition to the literature review, media discourse analysis is utilized to comprehensively examine how interfaith interactions and related issues are framed across various media outlets, including traditional (print) and digital (online news portals). This method is essential in revealing how religious identity, tolerance, and public debates surrounding interfaith greetings are represented in Indonesia (Idi and Priansyah, 2023; Wildan and Muttaqin, 2022). By analyzing these discourses, the study seeks to uncover the underlying narratives that contribute to public perception, religious identity negotiation, and interfaith dialogue in a multicultural society like Indonesia (Pajarianto et al., 2022; Sulaiman et al., 2022). This analysis serves as a critical lens to examine societal dynamics, particularly in relation to religious tolerance and identity construction (Abdurrahim, 2023; Faozan and Rasyidi, 2023).

Furthermore, the qualitative methodology employed in this study facilitates an exploration of the complex socio-communicative dynamics that shape public discourse related to interfaith greetings (Akhmadi, 2022; Wildan and Muttaqin, 2022). The application of negotiated identity theory provides an analytical framework to examine how individuals and religious communities navigate their identities within interfaith dialogues, reflecting broader societal values of moderation and religious tolerance (Astana et al., 2024). This theoretical perspective is particularly relevant in multicultural and multi-religious settings, where such interactions may either promote interfaith harmony or exacerbate tensions, depending on how they are socially and politically constructed (Musyarrofah and Zulhannan., 2023; Sulaiman et al., 2022). To complement the literature review and discourse analysis, the study also conducts a systematic analysis of news articles, online opinion pieces, and social media discussions from 2019 to 2024 to identify dominant narratives surrounding interfaith greetings. The selection criteria for media sources are based on the following factors:

1. Diversity of perspectives—Ensuring a balanced representation of both proponents and opponents of interfaith greetings.

2. Credibility of sources—Prioritizing reputable news organizations, religious publications, and official government statements.

3. Public engagement—Focusing on topics that have sparked significant public debate, controversy, or discourse in digital and traditional media.

By integrating literature review, media discourse analysis this study offers a comprehensive exploration of the communicative and social dynamics surrounding interfaith greetings in Indonesia. This multi-faceted approach ensures a balanced and nuanced understanding of the issue, providing both theoretical insights and empirical evidence on how religious identity is shaped, negotiated, and contested in a pluralistic society. This qualitative research strategy enables the study to encapsulate not only the theoretical foundations of religious moderation but also its practical implications in everyday interactions and policy-making (Mutaqin, 2024; Ramli, 2019). Through a systematic synthesis of literature, media analysis, and empirical observations, the research aims to present a holistic view of the multiple factors influencing interfaith greetings and the broader discourse on religious moderation in Indonesia (Susanto S. et al., 2022; Yusuf et al., 2023). By adopting this integrated methodological approach, this study seeks to contribute meaningfully to ongoing discussions on religious pluralism and interfaith engagement, particularly in the Indonesian context (Daffa, 2023; Rante Salu et al., 2023; Susanto T. et al., 2022).

3 Discussion

In facing the issue of interfaith greetings, it is important to find a way to accommodate the MUI’s concerns about maintaining the purity of faith while encouraging the spirit of tolerance and harmony carried out by the Ministry of Religion. Some middle-ground solutions that can be considered include the following: Building a constructive dialogue between the MUI, the Ministry of Religion, and other religious leaders to find common ground and understand limitations and ethics in the use of interfaith greetings. This dialogue must be based on the spirit of mutual respect, empathy, and the desire to find a win-win solution by creating a universal greeting that is acceptable to all religions in Indonesia (Faidi et al., 2021; Muhaemin et al., 2023; Rachmadtullah et al., 2020). Develop guidelines or guidelines for the use of interfaith greetings that can be accepted by all parties. This guide emphasises the importance of respecting the beliefs of each religion while also providing space for the expression of tolerance in a pluralistic social context. For example, the guide may suggest the use of universal and inclusive greetings, such as “Greetings of Peace” or “Greetings of Humanity,” in interfaith events. In Indonesia, a country known for its religious diversity, the use of interfaith greetings is a common practice that reflects respect and tolerance among its citizens. Each of the six officially recognized religions in Indonesia has its own unique greeting, which serves as a symbol of unity and harmony. For Muslims, the greeting Assalamu’alaikum warahmatullahi wabarakatuh (May peace, mercy, and blessings of Allah be upon you) is a reflection of their faith’s emphasis on peace. For Christians, both Protestant and Catholic, Shalom (Peace be with you) and Salam sejahtera bagi kita semua (May peace and prosperity be with us all) convey similar wishes for peace and well-being. Hindus use Om Swastiastu (May welfare and safety always accompany us), while Buddhists greet with Namo Buddhaya (I honor the Buddha), reflecting their reverence for the teachings of Buddha. Finally, Confucian followers often use Ni hao or Salam sejahtera (Greetings for peace and well-being), promoting harmony. These greetings highlight the rich cultural and religious tapestry of Indonesia and demonstrate the importance of mutual respect and understanding in a pluralistic society (Susanto et al., 2023; Susanto, 2024).

A critical element in this discourse is the concept of negotiated identity, as proposed by Ting-Toomey. According to this theory, identity is not static but continuously negotiated based on social context and interactions between individuals or groups. In Indonesia’s pluralistic society, where people from diverse religious backgrounds coexist, religious identities are often renegotiated through shared social practices and dialogue. The use of interfaith greetings becomes a form of negotiated identity, allowing individuals and groups to maintain their core religious beliefs while engaging in respectful and inclusive interactions with others.

Educating the public about the essence and values behind aith greetings, namely respect for diversity and commitment to live in harmony in differences (Muhaemin et al., 2023). This education can be conducted through public campaigns, seminars, or religious education programs that emphasise the importance of tolerance and inclusivity. Encouraging joint initiatives among religious communities can strengthen social bonds and mutual trust (Muqowim et al., 2022; Yuliawati et al., 2023). For example, holding social activities, community services, or the erf aith dialogue involving various religious communities. This type of initiative can help bridge differences and foster a spirit of brotherhood. Strengthening the role of the government, especially the Ministry of Religion, in overseeing religious moderation policies and practices. This includes allocating adequate resources to programs that support tolerance and pluralism as well as taking decisive action against any form of discrimination or hate speech based on religion. By combining these approaches, it is hoped that a middle ground can be created where adherence to religious principles can go hand-in-hand with respect to diversity and commitment to maintaining social harmony. This requires goodwill, flexibility, and cooperation from all parties involved. Only with an inclusive and mutually respectful middle way can the sustainability of tolerance and harmony between religious communities in Indonesia be maintained and strengthened.

3.1 The social impact of the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) fatwa on interfaith greetings

The fatwa issued by the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) on interfaith greetings has had a significant social impact across various sectors of society, particularly in public settings and government institutions. Although this fatwa does not hold legally binding authority, it has influenced religious discourse and social behavior, creating challenges for individuals navigating religious pluralism in Indonesia (Mun’im, 2022; Nasir, 2022). This phenomenon is particularly evident in various domains, including pressure on public officials, practices in educational institutions, social media dynamics, and workplace interactions.

3.1.1 Case 1: pressure on civil servants and public officials

One of the most notable cases illustrating the social impact of this fatwa is the pressure faced by civil servants and public officials. In 2019, several local government officials found themselves in situations where they felt compelled to avoid using interfaith greetings in their official speeches. This was due to concerns about violating religious norms set by local religious figures who adhered to conservative interpretations (Azmi, 2023; Imaduddin and Khafidin, 2018). In this context, many officials opted to use more traditional Islamic greetings, such as Assalamu’alaikum, to maintain compliance with religious norms while facing a conflict with the need to respect societal diversity (Nasir, 2022; Qulub and Munif, 2023). This dilemma reflects the tension between the desire to adhere to religious teachings and the effort to uphold pluralistic values.

3.1.2 Case 2: educational practices and religious identity in institutions

The second case concerns educational institutions and the role of religious identity in shaping institutional practices. Schools affiliated with Islamic organizations generally encourage students and staff to refrain from using interfaith greetings, fearing that such practices may dilute the sincerity of Islamic teachings (Hakim and Imam Bustomi, 2021; Wahyu Akbar and Ismaly, 2021). On the other hand, state-run educational institutions, which emphasize religious moderation, actively support the use of interfaith greetings to promote inclusivity among students. For instance, a Muslim teacher at a public school faced criticism from religious figures after greeting students with Sejahtera bagi Kita Semua (“Peace and Prosperity for Us All”), which was intended as a form of respect for diversity (Mun’im, 2022; Nasir, 2022). This situation demonstrates that the fatwa not only influences individual behavior but also creates boundaries within Indonesia’s diverse educational system.

3.1.3 Case 3: social media and public reactions

Social media has played a crucial role in amplifying and mitigating the impact of the fatwa on interfaith greetings. In 2022, for example, an Indonesian politician who used interfaith greetings during a national holiday celebration faced severe backlash from conservative religious groups, who viewed the act as a betrayal of Islamic principles (Mun’im, 2022; Purnomo, 2023). Conversely, there were also voices in support of the politician, arguing that the gesture was a reflection of recognition and unity among Indonesia’s diverse communities. Social media has become a battleground where different perspectives clash, often leading to online polarization that extends into real-world social tensions (Hakim and Imam Bustomi, 2021; Nasir, 2022). Many discussions have focused on how these digital platforms can either exacerbate or alleviate social divisions.

3.1.4 Case 4: workplace interactions and religious expression

The final case involves the impact of the fatwa in professional settings, where many employees in government offices and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have reported discomfort regarding interfaith greetings. While some institutions strive to promote religious tolerance by allowing employees to greet others based on their personal preferences, others have implemented policies that restrict or discourage interfaith greetings to avoid internal workplace conflicts (Azmi, 2023; Mun’im, 2022). This situation has created an uncomfortable environment for employees and has the potential to reduce workplace morale, particularly for those who wish to celebrate religious diversity among their colleagues (Hakim and Imam Bustomi, 2021; Wahyu Akbar and Ismaly, 2021).

By examining these various cases, it can be concluded that the MUI fatwa on interfaith greetings has had a complex and multifaceted social impact. While it reinforces potential religious conflicts, it also presents opportunities for interfaith dialogue. In summary, although the fatwa is not legally binding, it has become an integral part of public discourse and social behavior in Indonesia, with broad implications for pluralism and religious moderation in a multicultural society (Mun’im, 2022; Hakim and Imam Bustomi, 2021).

3.2 Comparative analysis: the role and function of MUI in religious guidance and public services

The fatwa issued by the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) on interfaith greetings has had a complex and multifaceted social impact. Although not legally binding, these fatwas significantly influence public discourse and religious behavior, especially in sensitive socio-political contexts. As noted by Zuhri et al. (2024), in the post-truth era, MUI’s fatwas are increasingly prone to contestation and even misuse due to the intricate interplay of cultural, political, and technological dynamics in Indonesia. Therefore, fatwas must be carefully packaged—not only in theological terms but also in a way that is attuned to cultural diversity and political sensitivities. This includes leveraging appropriate online media infrastructures to ensure that religious guidance remains both authoritative and relevant to contemporary society.

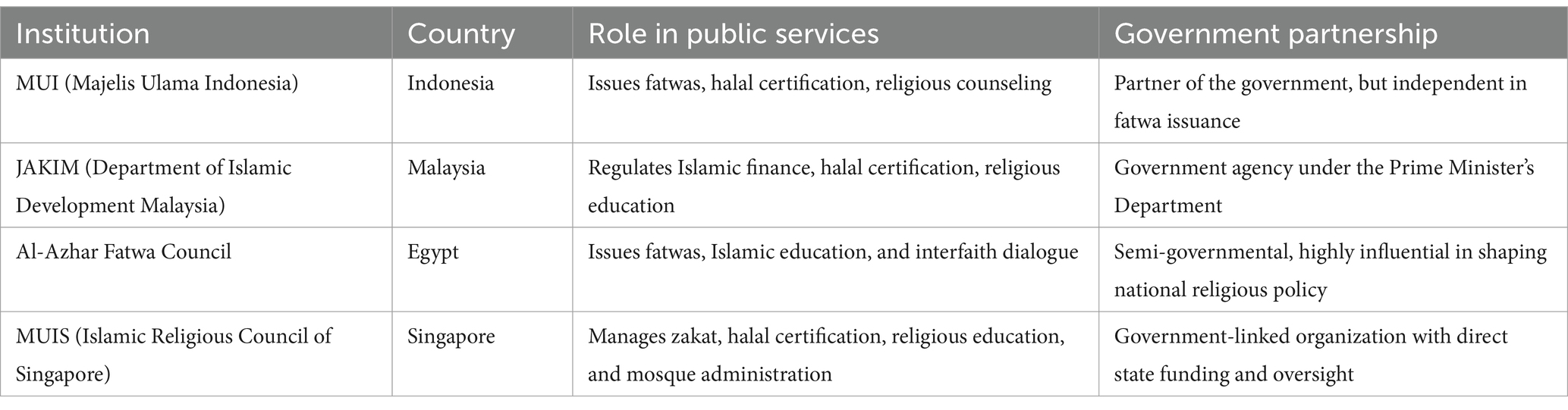

The comparative analysis of the role and function of the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) in providing religious guidance and public services reveals a multifaceted authority that operates within a unique cultural and political landscape, distinctly influencing religious discourse and public policy. The MUI, akin to various religious institutions in different countries, serves essential functions, including issuing legal opinions (fatwas), offering spiritual guidance, and participating in governmental religious affairs. Understanding these roles requires a closer examination of MUI’s functions alongside similar organizations, such as the Department of Islamic Development Malaysia (JAKIM), Al-Azhar in Egypt, and the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (MUIS).

3.2.1 MUI as a provider of religious guidance and public services

The primary role of MUI in Indonesia centers around the issuance of fatwas, halal certification, and providing Islamic counseling. Even though MUI operates independently as a non-governmental body, its fatwas carry considerable influence, shaping both public perceptions and Islamic practices within the country (Hakim et al., 2023; Tarantang and Hasan, 2023). Unlike governmental bodies such as the Indonesian Ministry of Religious Affairs (Kemenag), MUI functions independently yet maintains a collaborative relationship with the state on religious matters (Muhaimin and Muslimin, 2023; Yusmad and Siliwadi, 2022). This duality allows MUI to retain its credibility among conservative Islamic circles while simultaneously engaging in discussions that inform governmental policy and public services (Hakim et al., 2023; Hasyim, 2020).

3.2.2 MUI as a government partner in religious affairs

Despite its non-governmental status, MUI acts as an important ally to the Indonesian government in developing and implementing religious policies. The council plays a pivotal role in advising Kemenag on contemporary religious issues, including halal certification and the mediation of religious disputes (Muhaimin and Muslimin, 2023; Tarantang and Hasan, 2023). This partnership, however, is often marked by tension, especially regarding contentious topics such as religious moderation and interfaith relations (Hakim, 2023; Hasyim, 2020). The independence of MUI in issuing fatwas can lead to divergent positions between religious scholars and state authorities, particularly when MUI’s rulings may challenge or critique prevailing government policies. This aspect of MUI’s role highlights the balance it must maintain between advocating for religious integrity and navigating the political landscape in Indonesia.

3.2.3 Comparison with other religious institutions

When situated alongside analogous religious institutions, MUI’s operational framework surfaces several distinctions. For instance, the JAKIM in Malaysia functions as a government agency with regulatory authority over Islamic education, finance, and halal certification, indicating a more integrated governmental function when compared to MUI’s advisory role (Yusmad and Siliwadi, 2022)(De Juan et al., 2015). This governmental oversight ensures that JAKIM’s policies directly shape national religious objectives, contrasting sharply with MUI’s independent stance, which sometimes leads to discord with the government.

In Egypt, Al-Azhar serves both as a prestigious educational institution and a semi-governmental body that significantly influences national religious policy, particularly in areas of interfaith dialogue and Islamic scholarship (De Juan et al., 2015; Fatmawati et al., 2018). Unlike MUI, which may issue fatwas reflecting a diverse array of interpretations, Al-Azhar’s fatwas often align closely with state-sponsored narratives that promote a unified Islamic message. This distinction underlines how state influence may create a more cohesive religious policy in Egypt compared to the pluralistic environment in Indonesia, where multiple religious voices coexist (Table 1).

The MUIS in Singapore represents a model where the council operates as a government-linked organization, managing various religious affairs, including zakat, halal certification, and mosque administration under state oversight. This level of integration ensures that MUIS’s functions are directly supported and funded by the state, facilitating a more streamlined approach toward religious governance compared to MUI’s more autonomous operations.

3.2.4 Diverse roles of MUI across contexts

MUI’s role extends beyond merely advising the government; it actively engages with the public through various initiatives aimed at promoting religious understanding and tolerance within an increasingly pluralistic society (Davis and Rodriguez, 2024; Muhaimin and Muslimin, 2023). This includes addressing contemporary issues that affect the Muslim community, such as public health concerns, as evidenced by MUI’s role during the COVID-19 pandemic, where it issued fatwas that provided guidance consistent with public health measures while upholding Islamic principles (Tarantang and Hasan, 2023; Naim et al., 2023).

The comparative lens also allows for an exploration of the impact of each institution’s operations on social cohesion and harmony within multifunctional societies. In contrast to MUI’s independent approach, JAKIM’s regulatory powers may enforce a singular interpretation of Islam that could limit pluralistic engagements, potentially leading to greater societal cohesion at the expense of diversity (Alim et al., 2023; Hakim et al., 2023).

In conclusion, MUI operates as both a religious authority and a partner in governmental affairs, navigating a complex relationship with state policies while maintaining its autonomy in issuing fatwas. This independence is crucial in fostering credibility and legitimacy among conservative factions within Islam. Nevertheless, it also presents challenges in balancing Islamic principles with the realities of governance in a multicultural Indonesia. Strengthening dialogue among MUI, Kemenag, and other religious organizations will be instrumental in reinforcing religious policies that uphold both theological integrity and social harmony in such a diverse landscape (Hasyim, 2020; Muhaimin and Muslimin, 2023; Peifer, 2015).

3.3 The use of interfaith greetings as an effort to build religious tolerance moderation

The use of interfaith greetings in Indonesia can be viewed as a tangible expression of the effort to build moderation and tolerance among religious communities in this highly diverse nation. Interfaith greetings are not merely words of greeting but serve as symbols of acceptance of differences and a commitment to maintaining social harmony amidst the pluralism present in Indonesia. As a country with over six officially recognized religions and more than 300 ethnic groups, Indonesia requires effective communication channels to strengthen relations between religious groups, and one of these channels can be realized through the use of interfaith greetings.

3.3.1 Understanding religious moderation

Religious moderation refers to an approach that encourages adherents of various faiths to practice their beliefs in a balanced manner, avoiding extremism, and respecting differences. This approach emphasizes inclusivity, allowing religious practices to coexist peacefully without compromising the core beliefs of each religion. In the context of Indonesia, religious moderation plays a critical role in preventing radicalization and strengthening social cohesion within a diverse society. Therefore, the use of interfaith greetings can be seen as a form of moderation, helping to cultivate a collective awareness of peaceful coexistence.

3.3.2 Interfaith greetings as a tool for tolerance

Interfaith greetings embody values of respect for the beliefs of others and demonstrate a willingness to foster brotherhood despite religious differences. For example, a Muslim wishing a Christian “Selamat Natal” (Merry Christmas) or a Hindu using “Om Swastiastu” during interfaith gatherings, represents recognition and respect for the religious practices and traditions of others, without diminishing the essence of each individual’s faith. In this sense, interfaith greetings act as symbols of appreciation for diversity and as an effort to create a more inclusive public space for dialogue and mutual respect.

3.3.3 The role of government and religious institutions

For interfaith greetings to thrive, the role of government and religious institutions is crucial. The Indonesian government, through the Ministry of Religious Affairs (Kementerian Agama), should take the lead in educating the public on the importance of religious moderation and tolerance in daily life. Moreover, organizations like the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) and other religious bodies should facilitate constructive dialogues to resolve any controversies and find common ground on how interfaith greetings can be used in a way that does not conflict with religious principles.

3.3.4 Historical use of interfaith greetings in Indonesia

The practice of interfaith greetings in Indonesia has evolved significantly over the decades, from the colonial era to the present day, with different presidents shaping the discourse around religious tolerance:

a. Soekarno Era (1945–1967) During President Soekarno’s leadership, Indonesia was undergoing the process of nation-building, where national unity and multiculturalism were paramount. As the first president of a newly independent nation, Soekarno promoted the idea of “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika” (Unity in Diversity), which laid the foundation for pluralism. While formal interfaith greetings were not widely used in official contexts, there was an emerging culture of respect and recognition of religious diversity, especially in the context of national events and celebrations. Soekarno often emphasized national unity, and although the use of interfaith greetings like “Selamat Natal” or “Shalom” was not yet the norm, the spirit of tolerance was embedded in public discourse.

b. Soeharto Era (1967–1998) Under President Soeharto’s New Order regime, Indonesia experienced significant political and social control, with a stronger emphasis on nationalism and religious harmony. During this period, while religious freedom was largely upheld, the use of interfaith greetings began to appear more frequently in official and public spheres, especially in national and social events. However, the government still emphasized the dominance of Pancasila and kept discussions on religious practices within the boundaries of public order. The practice of using interfaith greetings began to solidify, particularly in multicultural events or ceremonies where representatives of different religious groups interacted.

c. Post-Reformasi Era (1998–Present) Following the fall of the New Order and the beginning of the Reformasi era, Indonesia saw an increased level of political and social openness. The 1998 reforms, which included the decentralization of power and greater freedom of expression, brought new opportunities for religious communities to engage with one another more openly. During the presidency of Abdurrahman Wahid (Gus Dur), Indonesia witnessed a significant push for interfaith dialogue and greater religious tolerance. Gus Dur, who was known for his inclusive approach to religion, encouraged the use of interfaith greetings as part of a broader strategy to promote religious pluralism and unity.

d. Under President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (2004–2014), interfaith greetings became more widely accepted, especially during national holidays or events where religious diversity was celebrated. The rise of civil society movements advocating for religious tolerance also contributed to the normalization of interfaith greetings, emphasizing respect for diversity as a national value.

e. Joko Widodo (2014–Present): President Joko Widodo’s administration has continued to build on the foundation of interfaith tolerance, promoting moderate religious practices and inclusive governance. The use of interfaith greetings, such as “Selamat Natal” (Merry Christmas), “Om Swastiastu,” and “Shalom,” has become increasingly common in public and official contexts. The government has also supported interfaith initiatives and encouraged dialogue to foster national unity. At the same time, religious leaders and organizations have emphasized the importance of maintaining the balance between respect for religious beliefs and the need for social harmony.

3.4 Building mutual understanding in interfaith greetings: conceptual steps

To address the ongoing polemic surrounding interfaith greetings in Indonesia—an issue that often sparks debates between the MUI, the Ministry of Religious Affairs (Kemenag), and society—a comprehensive and strategic approach is required to prevent similar controversies in the future. As Noviandy et al. (2023) argue, the contestation of religious authority is often less about ideological divergence and more about the struggle to assert dominance over public religious narratives. In this context, interfaith greetings become symbolic of a broader negotiation over religious legitimacy in public space. A key step in responding to this tension is fostering open and constructive dialogue among MUI, Kemenag, and religious leaders from various communities. Such discussions should aim to find common ground that accommodates both the preservation of religious teachings and the necessity of fostering mutual respect in Indonesia’s multicultural society. This dialogue must be rooted in mutual understanding, sincerity, and the shared goal of achieving social harmony.

In addition to dialogue, clear and standardized guidelines regarding interfaith greetings must be developed. These guidelines should provide practical references to ensure that greetings are widely accepted without offending specific religious beliefs. One possible solution is the formulation of a neutral, universal greeting, such as “Greetings of Peace,” “Salam Sejahtera,” or “Greetings of Humanity,” which can be used across religious groups while avoiding elements specific to any one faith. By adopting such an approach, Indonesia can maintain an atmosphere of inclusivity while respecting the theological boundaries of different religious communities.

Furthermore, public education on tolerance and religious moderation should be actively promoted through awareness campaigns, interfaith seminars, and religious education programs. The public needs to understand that respecting religious differences is not merely about etiquette but a commitment to peaceful coexistence. Interfaith greetings, when used appropriately, can serve as a symbol of respect for religious and cultural diversity. The government, together with religious organizations, must take a proactive role in implementing these educational initiatives to reinforce the importance of maintaining harmony in a pluralistic society.

Joint initiatives between religious communities can further solidify interfaith relations. Collaborative social programs such as community service projects, interfaith dialogues, and humanitarian efforts can demonstrate that despite religious differences, people share a collective responsibility toward social wellbeing. These initiatives provide tangible examples of how tolerance can be practiced in everyday life, moving beyond theoretical discussions into real-world applications.

The government also has a critical role in ensuring the protection of religious freedoms, including the right to use interfaith greetings in appropriate contexts. Policies promoting religious moderation and interfaith tolerance should continue to be reinforced, while decisive actions must be taken against discrimination, religious intolerance, and hate speech that threaten social harmony.

Given Indonesia’s rich religious diversity and complex socio-cultural landscape, the debate over interfaith greetings requires pragmatic and inclusive solutions, particularly from MUI, which plays a central role in providing religious guidance and shaping national policies. As Indonesia’s highest Islamic authority, MUI has emphasized the need to contextualize interfaith greetings within two fundamental Islamic frameworks: ibadah (worship) and muamalah (social interactions and transactions). From the perspective of ibadah, MUI maintains that prayers and greetings containing explicit religious elements should remain within the confines of their respective faiths to uphold theological purity. However, within the framework of muamalah, where social and professional interactions among people of different religious backgrounds are inevitable, some scholars within MUI recognize the importance of fostering social harmony and tolerance. This has led to a more nuanced interpretation, suggesting that interfaith greetings may be acceptable in non-religious settings, provided they do not compromise core religious principles.

To strike a balance, MUI, in collaboration with government institutions and religious leaders, has encouraged continuous dialogue to find a middle ground that respects both religious traditions and Indonesia’s multicultural reality. This includes developing guidelines that differentiate the appropriate use of interfaith greetings in formal state functions, professional environments, and religious ceremonies. By adopting a well-balanced approach, MUI aims to protect religious identity while promoting mutual respect and peaceful coexistence in Indonesia’s diverse society. With an inclusive and well-structured strategy rooted in open dialogue, clear guidelines, tolerance education, and interfaith collaboration Indonesia can maintain its pluralistic character while strengthening social harmony amid its religious and cultural diversity.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

TS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Validation. RA: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FD: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. FH: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. HS: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Department of Communication Science, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Singaperbangsa Karawang for their support and resources throughout this research. Their guidance has been invaluable in shaping this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdurrahim, A. (2023). The contribution of Mohammad Natsir’s thoughts in the formation of the unitary state of the Republic of Indonesia (NKRI) perspective of religious moderation Da’wah. Jurnal Syntax Transformat. 4, 10–27. doi: 10.46799/jst.v4i10.830

Akhmadi, A. (2022). Moderation of religious madrasah teachers. Inovasi-Jurnal Diklat Keagamaan 16, 60–69. doi: 10.52048/inovasi.v16i1.294

Alim, M. N., Sayidah, N., Faisol, I. A., and Alyana, N. (2023). Halal tourism in rural tourism context: field study in Madura-Indonesia. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 8:e01546. doi: 10.26668/businessreview/2023.v8i2.1546

Astana, A. C., Permatasari, T., Susijati, S., and Rahma, M. (2024). The relationship between the internalization of religious moderation values and the emotional intelligence of students at Buddhist higher education institutions in Indonesia. Proceeding of the International Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities Innovation, 1, 27–38. Available at: https://prosiding.appisi.or.id/index.php/ICSSHI/article/view/24

Azmi, M. (2023). Implementasi Fatwa MUI Tentang Hukum Menggunakan Atribut Non-Muslim Perspektif Pekerja Publik di Kota Malang. De Jure: Jurnal Hukum Dan Syar’iah 12, 297–311. doi: 10.18860/j-fsh.v12i2.15695

Daffa, M. (2023). The relevance of the Abu Dhabi document as a sustainability of religious moderation in Indonesia from a hadith perspective. Harmoni 22, 248–266. doi: 10.32488/harmoni.v22i2.701

Daheri, M., Warsah, I., Morganna, R., Putri, O. A., and Adelia, P. (2023). Strengthening religious moderation: learning from the harmony of multireligious people in Indonesia. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. 31, 571–586. doi: 10.25133/JPSSv312023.032

Davis, L., and Rodriguez, Z. (2024). Do religious beliefs matter for economic values? J. Inst. Econ. 20:262. doi: 10.1017/S1744137424000262

De Juan, A., Pierskalla, J. H., and Vüllers, J. (2015). The pacifying effects of local religious institutions: an analysis of communal violence in Indonesia. Polit. Res. Q. 68, 211–224. doi: 10.1177/1065912915578460

Faidi, A., Fauzi, A., and Septiadi, D. D. (2021). Significance of legal culture enforcement on tolerance among Madurese society through inclusive curriculum at IAIN Madura. Al-Ihkam Jurnal Hukum Dan Pranata Sosial 16, 57–76. doi: 10.19105/al-lhkam.v16i1.4302

Faozan, M., and Rasyidi, A. H. (2023). Critical review and reality of religious moderation in law and legal frameworks in Indonesia. Asian J. Sci. Technol. Eng. Art 1, 394–410. doi: 10.58578/ajstea.v1i2.2259

Fatmawati, F., Noorhayati, S. M., and Minangsih, K. (2018). Jihad Penista Agama Jihad NKRI: Antonio Gramsci’s hegemony theory analysis of radical Da’wah phenomena in online media. Al-Albab 7:199. doi: 10.24260/alalbab.v7i2.1174

Hakim, L. (2023). The Narration of religious moderation for mitigating radicalization among the millennial generations on Pesantren Lirboyo Instagram. Profetik Jurnal Komunikasi 16, 368–384. doi: 10.14421/pjk.v16i2.2633

Hakim, A., and Imam Bustomi, Y. (2021). Analisis Istinbath Ahkam Fatwa Majelis Ulama Indonesia Nomor 14 Tahun 2021 Tentang Hukum Penggunaan Vaksin Covid-19 Produk Astrazeneca. Muẚṣarah Jurnal Kajian Islam Kontemporer 3:8. doi: 10.18592/msr.v3i2.5704

Hakim, M. L., Prasojo, Z. H., Masri, M. S. B. H., Faiz, M. F., Mustafid, F., and Busro, B. (2023). Between exclusivity and inclusivity of institutions: examining the role of the Indonesian Ulema council and its political fatwa in handling the spread of Covid-19. Khazanah Hukum 5, 230–244. doi: 10.15575/kh.v5i3.30089

Hasyim, S. (2020). Fatwas and democracy: Majelis Ulama Indonesia (MUI, Indonesian Ulema council) and rising conservatism in Indonesian Islam. Trans-Reg. Nat. Stud. Southeast Asia 8, 21–35. doi: 10.1017/trn.2019.13

Idi, A., and Priansyah, D. (2023). The role of religious moderation in Indonesian multicultural society: a sociological perspective. Asian J. Eng. Soc. Health 2, 246–258. doi: 10.46799/ajesh.v2i4.55

Imaduddin, M., and Khafidin, Z. (2018). Ayo Belajar IPA dari Ulama: Pembelajaran Berbasis Socio-Scientific Issues di Abad ke-21. Thabiea J. Nat. Sci. Teach. 1:102. doi: 10.21043/thabiea.v1i2.4439

Indainanto, Y. I., Dalimunthe, M. A., Sazali, H. R., and Kholil, S. (2023). Islamic communication in voicing religious moderation as an effort to prevent conflicts of differences in beliefs. Pharos J. Theol. 104:415. doi: 10.46222/pharosjot.104.415

Jati, W. R., Halimatusa’diah, S., Aji, G. B., Nurkhoiron, M., and Tirtosudarmo, R. (2022). From intellectual to advocacy movement: Islamic moderation, the conservatives and the shift of interfaith dialogue campaign in Indonesia. Ulumuna 26, 472–499. doi: 10.20414/ujis.v26i2.572

Muhaemin, R., Pabbajah, M., and Hasbi,. (2023). Religious moderation in Islamic religious education as a response to intolerance attitudes in Indonesian educational institutions. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 14, 253–274.

Muhaimin, R., and Muslimin, J. (2023). The role of the Council of Indonesian Ulama (MUI) to the development of a Madani Society in the Democratic Landscape of Indonesia. Aspirasi Jurnal Masalah-Masalah Sosial 14:3368. doi: 10.46807/aspirasi.v14i2.3368

Muhammad, F. (2021). Ruang Publik Dan Agama Masa Depan. J. Ilmu Sosial Politik Dan Pemerintahan 2, 1–22. doi: 10.37304/jispar.v2i2.365

Mun’im, Z. (2022). Argumen Fatwa Mui Tentang Pluralisme Agama Dalam Perspektif Hak Asasi Manusia. Asy-Syari’ah 23, 205–228. doi: 10.15575/as.v23i2.13817

Muqowim, M., Sibawaihi, S., and Alsulami, N. D. (2022). Developing religious moderation in Indonesian Islamic schools through the implementation of the values of Islām Wasaṭiyyah. Jurnal Pendidikan Agama Islam 19, 207–222. doi: 10.14421/jpai.2022.192-03

Musyarrofah, U., and Zulhannan,. (2023). Religious moderation in the discourse of Nahdlatul Ulama’s Dakwah in the era of industry 4.0. Millah J. Relig. Stud. 22, 409–434. doi: 10.20885/millah.vol22.iss2.art5

Mutaqin, E. Z. (2024). Religious moderation in the interpretation of the Qur’an and its relevance to Islamic religious education in Indonesia. Tawasut 11:10930. doi: 10.31942/ta.v11i1.10930

Naim, N., Badruzaman, A., and Amalina, I. (2023). Madrasah Diniyah and Ma’had Al-Jami’ah-based religious moderation policy in state Islamic University in Indonesia. Jurnal Penelitian 171–184, 171–184. doi: 10.28918/jupe.v20i2.1944

Nasir, M. (2022). Pandangan MUI terhadap Pluralisme Agama. SINTHOP: Media Kajian Pendidikan, Agama. Sosial Dan Budaya 1, 1–17. doi: 10.22373/sinthop.v1i1.2336

Noviandy, N., Amin, M., Zubir, Z., and Masri, M. S. B. H. M. (2023). Contestation of religious Authority in Study Groups: between religious authority and mass Authority in Aceh. Relig. Jurnal Studi Agama-Agama Dan Lintas Budaya 7, 53–64. doi: 10.15575/rjsalb.v7i1.24898

Pajarianto, H., Pribadi, I., and Sari, P. (2022). Tolerance between religions through the role of local wisdom and religious moderation. HTS Teolog. Stud./Theol. Stud. 78:7043. doi: 10.4102/hts.v78i4.7043

Pangalila, T., Rotty, V. N. J., and Rumbay, C. A. (2024). The diversity of interfaith and ethnic relationships of religious community in Indonesia. Verbum et Ecclesia 45:2806. doi: 10.4102/ve.v45i1.2806

Parhusip, A. (2024). Exploring the evolution of religious moderation leadership from the local to national level. HTS Teolog. Stud./Theol. Stud. 80:8630. doi: 10.4102/hts.v80i1.8630

Peifer, J. L. (2015). The inter-institutional Interface of religion and business. Bus. Ethics Q. 25, 363–391. doi: 10.1017/beq.2015.33

Purnomo, B. (2023). Analisa Fatwa MUI Di Masa Covid 19 Dalam Perspektif Ushul Fiqih. NALAR J. Law Sharia 1, 120–130. doi: 10.61461/nlr.v1i2.37

Qulub, S. T., and Munif, A. (2023). Urgensi Fatwa dan Sidang Isbat dalam Penentuan Awal Bulan Kamariah di Indonesia. Jurnal Bimas Islam 16, 423–452. doi: 10.37302/jbi.v16i2.929

Rachmadtullah, R., Syofyan, H., and Rasmitadila,. (2020). The role of civic education teachers in implementing multicultural education in elementary school students. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 8, 540–546. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2020.080225

Ramli, R. (2019). Moderasi Beragama bagi Minoritas Muslim Etnis Tionghoa di Kota Makassar. KURIOSITAS Med. Komunikasi Sosial Dan Keagamaan 12, 135–162. doi: 10.35905/kur.v12i2.1219

Rante Salu, S. B., Siahaan, H. E. R., Rinukti, N., and Putri, A. S. (2023). Early church hospitality-based Pentecostal mission in the religious moderation frame of Indonesia. HTS Teolog. Stud./Theol. Stud. 79:8209. doi: 10.4102/HTS.V79I1.8209

Rusyana, A. Y., Budiman, B., Abdullah, W. S., and Witro, D. (2023). Concepts and strategies for internalizing religious moderation values among the millennial generation in Indonesia. Relig. Inquir. 12, 157–176. doi: 10.22034/ri.2023.348511.1629

Singgih, E. G. (2023). Religious moderation as good life: two responses to the Ministry of Religious Affairs’ directive on religious moderation in Indonesia. Exchange 52, 220–240. doi: 10.1163/1572543x-bja10038

Sulaiman, S., Imran, A., Hidayat, B. A., Mashuri, S., Reslawati, R., and Fakhrurrazi, F. (2022). Moderation religion in the era society 5.0 and multicultural society. Linguist. Cult. Rev. 6, 180–193. doi: 10.21744/lingcure.v6ns5.2106

Suntana, I., and Tresnawaty, B. (2022). The tough slog of a moderate religious state: highly educated Muslims and the problem of intolerance in Indonesia. HTS Teolog. Stud./Theol. Stud. 78:7933. doi: 10.4102/hts.v78i1.7933

Susanto, T. (2024). Ethnography of harmony: local traditions and dynamics of interfaith tolerance in Nglinggi Village, Indonesia. Asian Anthropol. 1–5, 1–5. doi: 10.1080/1683478X.2024.2434988

Susanto, S., Desrani, A., Febriani, S. R., Ilhami, R., and Idris, S. (2022). Religious moderation education in the perspective of millennials generation in Indonesia. AL-ISHLAH Jurnal Pendidikan 14, 2781–2792. doi: 10.35445/alishlah.v14i3.1859

Susanto, T., Sumardjo Sarwoprasodjo, S., and Kinseng, R. A. (2022). The message of peace from the village: development of religious harmony from Nglinggi Village. Al-Balagh Jurnal Dakwah Dan Komunikasi 7, 119–150. doi: 10.22515/albalagh.v7i1.5016

Susanto, T., Sumardjo Sarwoprasodjo, S., and Kinseng, R. A. (2023). Identity negotiations for the development of inter-religious harmony in a Peaceful Village, Nglinggi Klaten, Indonesia. Hong Kong J. Soc. Sci. 61:72. doi: 10.55463/hkjss.issn.1021-3619.61.72

Tarantang, J., and Hasan, A. (2023). The changing roles of Mui’S fatwas in the realization of Indonesian Government’S new Normal policy. Al-Turath J. Al-Quran Al-Sunnah 8:2. doi: 10.17576/turath-2023-0801-02

Thohir, M., and Lukluk Atsmara Anjaina, M. (2022). Moderation of religiosity in the view of Islam Nusantara. E3S Web Confer. 359:04005. doi: 10.1051/e3sconf/202235904005

Wahyu Akbar, W., and Ismaly, A. (2021). Epistemologi Fikih Filantropi Masa Pandemi Covid-19 di Indonesia. Jurnal Bimas Islam 14, 345–366. doi: 10.37302/jbi.v14i2.460

Wildan, M., and Muttaqin, A. (2022). Mainstreaming moderation in preventing/ countering violent extremism (P/Cve) in Pesantrens in Central Java. Qudus Int. J. Islamic Stud. 10, 37–74. doi: 10.21043/qijis.v10i1.8102

Yuliawati, S., Dienaputra, R. D., and Yunaidi, A. (2023). Coexistence of the ethnic Chinese and Sundanese in the city of Bandung, West Java: a case study on Kampung Toleransi. Asian Ethn. 24, 390–405. doi: 10.1080/14631369.2022.2158784

Yusmad, M. A., and Siliwadi, D. N. (2022). The position of the fatwa of the Indonesian Ulema council number 33 of 2018 concerning the measles-rubella vaccine: National law Perspective. Jurnal Ilmiah Al-Syir’ah 20:123. doi: 10.30984/jis.v20i1.1836

Yusuf, M., Alwis Putra, E., Witro, D., and Nurjaman, A. (2023). The role of Anak Jalanan at-Tamur Islamic boarding School in Internalizing the values of religious moderation to college students in Bandung. Jurnal Ilmiah Islam Futura 23, 132–156. doi: 10.22373/jiif.v23i1.15358

Keywords: interfaith dialogue, interfaith greetings, MUI fatwa, Ministry of Religion (Kemenag) Indonesia, negotiated identity theory

Citation: Dharta FY, Susanto T, Anggara R, Hariyanto F and Sianturi HRP (2025) MUI’s fatwa on interfaith greetings and religious tolerance: can Indonesia find a middle ground? Front. Commun. 10:1537568. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1537568

Edited by:

Busro Busro, State Islamic University Sunan Gunung Djati, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Usep Dedi Rustandi, State Islamic University Sunan Gunung Djati, IndonesiaDesi Erawati, State Institute of Islamic, Palangka Raya, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Dharta, Susanto, Anggara, Hariyanto and Sianturi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tri Susanto, dHJpLnN1c2FudG9Ac3RhZmYudW5zaWthLmFjLmlk

Firdaus Yuni Dharta

Firdaus Yuni Dharta Tri Susanto

Tri Susanto Reddy Anggara

Reddy Anggara Fajar Hariyanto

Fajar Hariyanto Hendry Roris P. Sianturi

Hendry Roris P. Sianturi