- School of Psychology, Sport and Health Sciences,University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, United Kingdom

Introduction: The implementation of regulations such as the Online Safety Act by the United Kingdom government to combat hate speech and misinformation has raised critical questions about potential psychological and behavioral impacts on digital expression. This study explores how political orientation influences perceptions of online speech regulation and consequent self-censorship behaviors.

Methods: An online survey was conducted with 548 UK residents (ages 18–65+, M = 35.3), gathering demographic data (age, sex, political orientation). Participants completed the validated Chilling Effect Scale (Cronbach’s α ≥ 0.82), measuring willingness to speak openly online, self-censorship tendencies, and perceived fear of government penalties. Participants also evaluated two anonymised social media posts portraying contentious themes (supporting a terrorist organisation and advocating immigrant expulsion).

Results: Participants showed higher self-censorship towards content perceived as potentially inciting harm. Political orientation significantly influenced willingness to speak out; specifically, “Very Liberal” participants were the most vocal, whereas Non-Political participants exhibited the highest self-censorship (F(5, 542) = 9.16, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.08). Additionally, liberal respondents were more sensitive to harmful content compared to conservatives or politically neutral individuals.

Discussion: The findings highlight the psychological effects of regulatory ambiguity, suggesting the necessity for clear regulatory definitions (e.g., specifying terms such as “legal but harmful”), transparent moderation policies, and support for cross-ideological dialogue. This research underscores critical factors for policymakers striving to balance public safety concerns with the preservation of free speech within polarized digital landscapes.

Introduction

In 2024, politically charged social media posts reacting to a heinous crime sparked protests in English towns, highlighting the role of digital platforms in shaping public discourse and intensifying societal divisions (Zaugg, 2024). These events led to increased legal scrutiny of online behavior, with prosecutions under UK laws such as the Malicious Communications Act 1988 and the Communications Act 2003 criminalizing abusive, threatening, or offensive messages. Terrorism Act 2006, have also been utilised by the state to target hate speech and terrorism-related online content (The Week, 2024). While intended to protect public safety, the vague language surrounding “legal but harmful” speech creates uncertainty about lawful expression, encouraging self-censorship and weakening democratic debate (Institute of Economic Affairs, 2024).

Schauer’s (1978) Chilling Effect Theory and Noelle-Neumann’s (1974) Spiral of Silence elucidate this chilling effect, which arises when vague regulations deter lawful expression and social pressures inhibit dissent. Advocates of regulation underscore the necessity to combat hate speech and misinformation, particularly in polarized contexts (Balkin, 2021; Brown and Peters, 2018). Detractors caution that poorly defined laws stifle legitimate viewpoints, cultivating a culture of fear (Kim, 2017; Laor, 2024; Sunstein, 2018).

This study investigates how these regulatory challenges, public sentiment, and platform policies affect self-censorship. It utilizes the Chilling Effect Scale and the Brandenburg Test to assess responses to contentious content among a politically diverse sample of 548 participants. The findings seek to inform policymakers and platform designers about encouraging democratic engagement and balancing public safety with free expression.

Theoretical context: balancing regulation and free expression

With 56.2 million users in the UK (82.8% of the population), social media is a cornerstone of modern communication and democratic engagement (Kemp, 2024). While these platforms have significantly transformed political discourse, they also present challenges, particularly in causing self-censorship due to ambiguous regulatory boundaries. The Online Safety Act (OSA) and older legislation, including the Malicious Communications Act 1988 and the Communications Act 2003, aim to tackle harmful online content (The Week, 2024). However, vague definitions such as “legal but harmful” introduce uncertainty, increasing the likelihood of users self-censoring to avert legal or reputational risks (Amnesty International, 2024; Büchi et al., 2022). The OSA’s provision concerning false communication, where sharing false information intending to cause “non-trivial” harm constitutes an offence, accentuates concerns regarding unclear boundaries (Newling, 2024; O’Shiel et al., 2023). These issues are particularly pronounced in polarised environments where contentious topics like immigration or national security elicit strong reactions. Conservatives frequently perceive these regulations as disproportionately targeting their viewpoints, while liberals may be reluctant to post content due to concerns about causing unintended harm.

These dynamics reflect Schauer’s (1978) Chilling Effect Theory, highlighting how ambiguous laws suppress lawful expression. Clarifying governmental terminology, such as clearly defining ‘legal but harmful’, would mitigate these effects, enabling users to engage in discourse without disproportionate fear of repercussions (Institute of Economic Affairs, 2024). Additional challenges include platform-specific practices like algorithmic amplification and inconsistent moderation, reinforcing users’ reluctance to engage with contentious issues (González-Bailón et al., 2022; Penney, 2021; Stoycheff, 2016). This study seeks to inform policymakers, government agencies, and platform designers about creating transparent regulations and inclusive moderation practices to balance free expression and public safety by addressing these intersecting factors.

Understanding the chilling effect in the UK

The chilling effect, first conceptualized by Schauer (1978), describes how individuals suppress self-expression due to fears of legal penalties or social backlash, even without direct threats (Kim, 2017; Laor, 2024; Sunstein, 2018). While originally framed in legal contexts, this concept has been adapted to digital environments where perceived surveillance, government overregulation, algorithmic biases, and opaque moderation practices constrain online behaviors (Büchi et al., 2022; Coe, 2022; González-Bailón et al., 2022; Sap et al., 2022; Stoycheff, 2016).

In the UK, the OSA exemplifies this phenomenon by introducing terms such as “legal but harmful,” which create uncertainty around permissible speech and exacerbate fears of unintentional violations (Amnesty International, 2024; Coe, 2022). Ofcom’s expanded authority to impose substantial fines on platforms hosting harmful content has raised concerns about regulatory overreach and its potential to suppress legitimate discourse. These concerns are further heightened by the permanence and visibility of online content, which leaves users anxious and worried that their posts may be scrutinized or penalized long after publication (Ho and McLeod, 2008; Zuboff, 2022).

Notably, recent policy debates, such as the UK government’s postponement of a free speech law in higher education, highlight broader tensions between safeguarding public safety and protecting individual freedoms (Mikelionis, 2024). The chilling effect due to the Online Safety Bill is particularly pronounced for marginalized groups and discussions of contentious issues (Penney, 2020). It may lead some individuals to refrain from participating in political activism, religious discussions, or other sensitive online interactions because of concerns about being monitored or surveilled (Chin-Rothmann et al., 2023). LGBTQ+ individuals often refrain from engaging in sensitive topics online out of fear of privacy violations or potential backlash (Warrender, 2023). Similarly, studies by Das and Kramer (2021) indicate that individuals who regret sharing inappropriate content frequently resort to self-censorship to protect their reputations.

Furthermore, individuals involved in politically diverse networks, such as Facebook groups encompassing various ideological perspectives, report heightened levels of self-censorship due to fears of alienation, social ostracism, or even job loss (Neubaum and Krämer, 2018; Weeks et al., 2024). This illustrates the interconnectedness of regulatory uncertainty, social risks, and political discourse in digital spaces. By exploring these relationships, this study examines how chilling influences democratic engagement online in the UK, particularly among individuals navigating politically polarized environments.

Political orientation and engagement with online content

Political orientation significantly influences individuals’ willingness to express their views or self-censor online. Existing research from the United States shows that the Chilling Effect disproportionately affects moderates, conservatives, independents, and moderate liberals, who are more likely to self-censor than those with more extreme political views (Burnett et al., 2022). Self-censorship may reinforce echo chambers, promote ideological rigidity, and reduce the diversity of perspectives essential for robust democratic debate (Barberá, 2014; Cinelli et al., 2021).

The phenomenon of the chilling effect in the UK is shaped by unique challenges stemming from regulatory ambiguity and the politically diverse digital landscapes. Social media engagement during the 2019 general election exposed clear partisan divides. Labour and SNP supporters predominantly used platforms like X and YouTube, whereas Conservatives gravitated towards Facebook and X (Fletcher, 2024). These patterns mirror broader trends, with X users skewing politically left, as Labor supporters outnumber Conservatives by 2:1 (Blackwell et al., 2019). This imbalance cultivates an online environment where progressive voices prevail, often marginalizing conservative and moderate perspectives.

However, polarizing events like Brexit mobilized right-leaning users, demonstrating how contentious topics can energize groups that might otherwise remain less vocal (Gorrell et al., 2018). Extremists on both ends of the ideological spectrum also exhibit distinct patterns of digital engagement. They often amplify their messages by reposting unverified content and openly expressing their beliefs, even when confronted with opposing viewpoints (Burnett et al., 2022). In contrast, moderates typically fact-check and avoid posting altogether (Lei Nguyen, 2021; Suciu, 2022).

Despite these insights, little is known about which political groups in the UK are most impacted by the chilling effect. This study addresses this gap by examining how regulatory ambiguity and the government’s intent to penalize criminal online content affect people’s willingness to speak out or remain silent on contentious issues. Specifically, it hypothesizes:

H1: Political Orientation and Willingness to Speak Out

Individuals with strong political orientations, whether highly liberal or conservative, will express their opinions on social media more frequently than those with moderate or neutral political views.

H2: Political Orientation and Tendency to Stay Silent Participants with more conservative political orientations, or those who identify as Non-Political, tend to self-censor more on social media due to fears of social or legal repercussions than Liberals, particularly Very Liberals.

The psychology of the chilling effect

The chilling effect in online spaces stems from the psychological link between worry and risk perception. This concept underscores the tension between emotional reactivity and the UK government’s “Think Before You Post” strategy for regulating online behavior (McLaughlin, 2024; Zillmann, 2010). As emotional beings, humans may impulsively share harmful content during moments of distress or anger, as demonstrated by the case of a conservative councillor’s wife who was imprisoned for 31 months (Judiciary.uk, 2024). While such stringent punishments aim to deter offences, they raise concerns about whether worry and fear are intentionally employed as tools for compliance (Enroth, 2017). These measures may promote a strategy of self-censorship but risk disproportionately penalizing individuals whose actions stem from fleeting emotional states. Alternatives such as restorative justice programs, hate speech education, or mental health interventions could tackle harmful online behavior without solely relying on punitive measures (Gavrielides, 2012).

The perception of being monitored, whether by OFCOM or through ambiguous regulations such as the Online Safety Act (OSA), amplifies self-censorship. The fear of surveillance prompts individuals to conform to social norms in order to avoid reputational harm or sanctions (Panagopoulos and van der Linden, 2017). Experimental evidence highlights the “watchful-eye effect,” which increases negative emotions like anxiety and nervousness while leaving positive emotions unchanged (Panagopoulos and van der Linden, 2017). This threat of observation suppresses lawful expression.

From the perspective of social norm psychology, these behaviors are rooted in conformity theories. Ambiguous regulations, such as the OSA’s vague “legal but harmful” provisions, exacerbate this issue, compelling individuals to conform to societal norms to navigate unclear boundaries (Huddy et al., 2008). This leads to increased behavioral conformity, particularly in contentious contexts where dissent poses risks of backlash or legal consequences (Hampton et al., 2014).

The “spiral of silence” effect exacerbates the chilling effect, as individuals suppress minority opinions due to fear of punitive outcomes (Noelle-Neumann, 1974). This phenomenon is particularly evident online, where platforms like Facebook promote self-censorship out of concern for offending one’s audience or damaging one’s reputation (Laor, 2024; Marder et al., 2016).

These dynamics influence individuals’ readiness to speak out or to stay silent. This study examines these patterns through the following hypotheses:

H3a: Risk-takers are more likely to speak out on social media.

H3b: Risk-averse Individuals are more inclined to remain silent online.

H4: Concerns about punitive consequences diminish the likelihood of speaking out.

Regulatory challenges: the online safety act and the Brandenburg test

Navigating the tension between ensuring public safety and protecting free expression continues to challenge UK regulators. The perceived severity of governmental punitive measures for voicing personal opinions or beliefs exacerbates self-censorship and the chilling effect in digital spaces.

To contextualize these challenges, this study employs the Brandenburg Test (Healy, 2009) to evaluate perceptions of freedom of expression through two authentic posts. The test’s focus on imminence and likelihood of incitement establishes a clearer standard for determining when speech crosses into unlawfulness. By applying this test to contentious online posts, this study examines how legal ambiguity affects self-censorship. Post A, which glorifies violence in response to geopolitical tensions, may meet the Brandenburg criteria and justify legal action. In contrast, Post B, a derogatory post targeting immigrants, while offensive, may fall into the OSA’s grey area, where it could be penalized despite failing to incite imminent lawless action. These examples underscore the complexities of implementing the OSA and its potential to deter lawful but controversial speech (Weeks et al., 2024).

Hate speech, political intolerance, and balancing free expression

Regulating hate speech is vital for protecting vulnerable groups and ensuring public safety. Nonetheless, ambiguous definitions of terms such as “hate speech” and “harmful content” heighten the risks of self-censorship. In the UK, hate crime is defined as “any criminal offence which is perceived, by the victim or any other person, to be motivated by hostility or prejudice towards someone based on a personal characteristic” (GOV.UK, 2024). While this broad definition promotes inclusivity, it raises concerns about subjective interpretation and potential overreach. For example, non-crime hate incidents (NCHIs) can be recorded solely based on perception, which leads to fears of being falsely accused for lawful expressions of opinion. Between 2014 and 2019, over 119,000 NCHIs were recorded in England and Wales, underscoring the chilling effect on free expression (Cieslikowski, 2023).

Such fears are heightened in polarized environments, where users across the political spectrum may refrain from engaging in contentious discussions (Crawford and Pilanski, 2012). Research illustrates how ideological attitudes influence responses to hate speech. Dellagiacoma et al. (2024) discovered that right-wing authoritarian (RWA) attitudes, which prioritize stability and adherence to norms, reduce engagement with online hate speech (OHS). Conversely, Bilewicz et al. (2017) observed that RWA individuals frequently advocate for penalizing hate speech to maintain social order. Meanwhile, Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory (2012) sheds light on ideological divergence: Liberals emphasize care and fairness, focusing on sensitivity to online harm and reporting hate speech (Wilhelm and Joeckel, 2019), whereas conservatives prioritize liberty and authority, expressing greater concern over regulatory overreach.

Psychological mechanisms, such as threat perception and in-group/out-group dynamics, further elucidate these patterns. Conservatives frequently perceive regulations as disproportionately targeting their beliefs, resulting in feelings of marginalisation. Conversely, liberals view harmful speech as a direct assault on their values or vulnerable groups, leading to heightened support for regulation. Research by Elad-Strenger et al. (2024) underscores how emotional ideological outgroups influence responses to sociopolitical issues. When outgroups act non-stereotypically, hostility may diminish; however, individuals often escalate their ideological positioning to fortify group identity.

The permanence of online content exacerbates these dynamics, as social media users are worried about their posts being scrutinized retroactively (Anderson and Barnes, 2022). This anxiety underpins the following hypotheses:

H5: Liberals are more likely to show greater sensitivity to harmful content than conservatives and non-political participants.

H6a: Conservatives and non-political participants will prioritize free speech over concerns related to hate.

H6b: Liberals and Very Liberals will prioritize addressing harm rather than safeguarding free speech.

Methods

Participants

A convenience sample of 548 participants was recruited online through social media platforms including Facebook, X, LinkedIn, and the subreddit r/PoliticsUK. These platforms were selected to encompass various political orientations and varying levels of online engagement, aligning with the study’s focus on self-censorship and online political behavior. To further expand the sample, recruitment materials were also shared in community forums and general-interest platforms (r/SampleSize) to encourage participation from underrepresented groups. Despite these efforts, the sample may exhibit a bias towards politically active users, acknowledging the exploratory nature of the research limitations. The final sample size of 548 participants was determined by:

Prior Research Benchmarks: Similar studies on self-censorship and political engagement have employed sample sizes ranging from 200 to 600 participants, ensuring adequate statistical power for subgroup analyses.

Stoycheff (2016, Study 1) examined surveillance perceptions and online behaviors with 232 participants. Stoycheff (2016, Study 2) explored the impact of government surveillance on political behavior with 213 participants. Wilhelm and Joeckel (2019) conducted a study involving 457 participants in a 2 × 2 online experiment investigating gender differences in responses to hate comments. These findings illustrate the appropriateness of the chosen sample size for analyzing nuanced patterns in politically sensitive contexts.

Practical Constraints: Recruitment through online platforms ensured wide accessibility but restricted the capacity to meet strict demographic quotas. The sample size balances feasibility with the study’s analytical objectives.

Power Analysis: A post hoc power analysis conducted with G*Power confirmed that the 548-sample size offers over 95% power to detect medium effect sizes (f2 = 0.15) at α = 0.05, ensuring sufficient sensitivity to identify significant relationships.

Demographic breakdown

Age Distribution:

18–30 years: 12%, 31–45 years: 55%, 46–65 years: 29%, Over 65 years: 4%.

Political Orientation:

Very Liberal: 9%, Liberal: 43%, Moderate: 18%, Conservative: 21%, Non-Political: 7%.

Prefer not to say: 1.5%.

The sample was predominantly politically engaged, with 91% identifying along a political spectrum. This demographic information enhances transparency and assists in evaluating the contextual relevance of the findings. The University of Portsmouth ethics committee approved the study, and all participants provided informed consent before participating.

Instruments

Chilling effect scale

The Chilling Effect Scale was adapted from the Spiral of Silence Scale (Lee et al., 2014) and the Pew 2012 Search, Social Networks, and Politics Survey (Gearhart and Zhang, 2015). This 12-item scale assesses participants’ tendencies to self-censor or voice their opinions online:

Willingness to Speak Out (e.g., “When I disagree with political content on social media, I am more likely to speak out”; Cronbach’s α = 0.896).

Tendency to Stay Silent (e.g., “The government’s use of social media for politics makes me more likely to stay silent online”; Cronbach’s α = 0.854).

Expressing Views Despite Consequences (e.g., “I express personal political views online even if there could be government consequences”; Cronbach’s α = 0.824).

Perceived Governmental Punishment (e.g., “I worry about being punished by the government for my political views”; Cronbach’s α = 0.852).

Responses were recorded using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

Brandenburg test framework

The Brandenburg Test was employed to evaluate participants’ perceptions of two anonymized posts created by UK residents, who were subsequently questioned by the authorities regarding their content. These posts served as real-world examples of controversial online speech:

Post A, posted by a journalist, glorified the violent actions of a designated terrorist organisation.

Post B, shared on Facebook, contained derogatory language aimed at immigrants.

The following constructs were assessed based on the Brandenburg Test (Leets, 2001):

Intent (“How do you perceive the intent of this post?”; Cronbach’s α = 0.609). While this construct showed lower reliability, it was retained for its theoretical importance. Results using this measure should be interpreted cautiously and triangulated with other constructs.

Threatening Nature (“This content advocates lawless action”; Cronbach’s α = 0.861).

Harmfulness (“This post is harmful to society”; Cronbach’s α = 0.725).

Persuasiveness (“I found the content persuasive”; Cronbach’s α = 0.708).

Hate Content (“I consider this hate speech”; Cronbach’s α = 0.891).

These constructs were chosen to capture critical dimensions of perceived risk and harm associated with contentious online content, directly related to the study’s focus on chilling effects and self-censorship.

Procedure

Participants were directed to an online survey hosted on Qualtrics. Recruitment materials clearly outlined the voluntary nature of the study, and participants provided informed consent before proceeding. All data were collected anonymously to ensure privacy.

The survey consisted of the following sections:

Demographic Information: Age, gender, political orientation, and prior exposure to online harassment or hate speech.

Chilling Effect Scale: Measures of willingness to speak out, tendency to stay silent, and perceived risks of online expression.

Brandenburg Test: Evaluation of two anonymized posts using the constructs described above.

The survey, adhering to standard online survey guidelines designed to minimize fatigue, took approximately 15–20 min to complete. Recruitment materials were disseminated across diverse platforms to maximize heterogeneity in participant backgrounds. The limitations of convenience sampling affect representativeness and are acknowledged as a study limitation.

Data analysis

Primary analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 28.0.1.1. Descriptive statistics, correlations, and t-tests were used to explore the relationships between variables. Multiple regression analyses were employed to identify predictors of self-censorship and willingness to speak out. Diagnostic checks, including assessments of multicollinearity and normality, were performed to confirm the regression assumptions.

Supplementary variables

Prior exposure to hate speech was included as a supplementary variable and analyzed concerning self-censorship tendencies. Regression models also employed these variables as covariates to evaluate their impact on the primary constructs.

Sensitivity analyses

To ensure robustness:

Subgroup analyses examined differences across political orientations.

Bootstrapping with 5,000 samples was conducted to calculate confidence intervals for regression estimates.

Ethical considerations

This study followed the ethical guidelines set forth by the University of Portsmouth’s ethics committee. Participants provided informed consent, were assured of their right to withdraw, and survey responses were anonymized to maintain confidentiality. Anonymizing sensitive posts in the survey reduced potential emotional distress for participants.

Results

Descriptive statistics

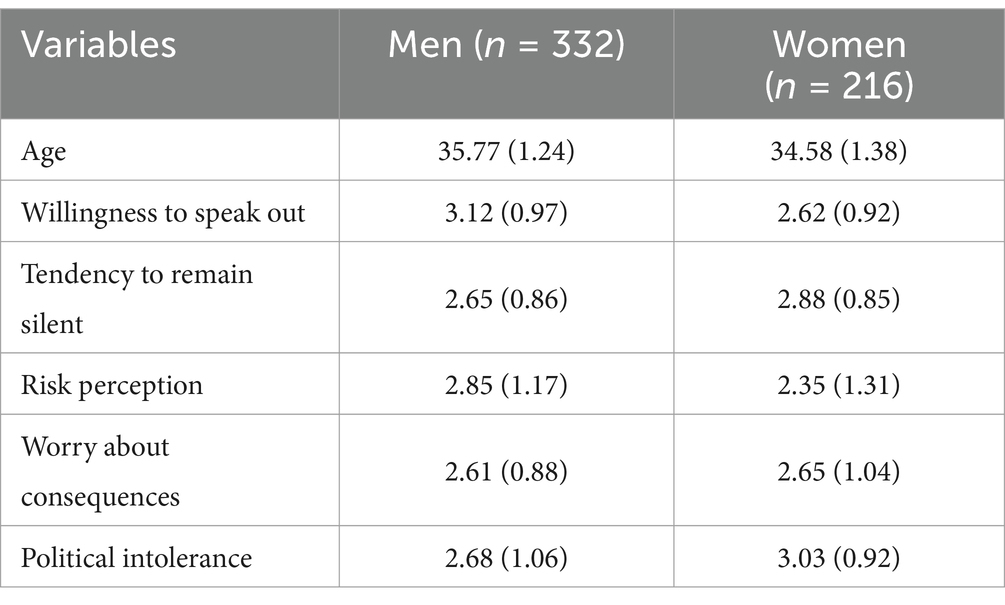

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) for key variables by gender.

Men reported a greater willingness to speak out (M = 3.12, SD = 0.97) than women (M = 2.62, SD = 0.92), with a mean difference of 0.50, 95% CI [0.34, 0.66], indicating a moderate effect size (d = 0.53). Conversely, women demonstrated a stronger tendency to remain silent (M = 2.88, SD = 0.85) compared to men (M = 2.65, SD = 0.86), with a mean difference of −0.23, 95% CI [−0.38, −0.08], reflecting a small effect size (d = − 0.27).

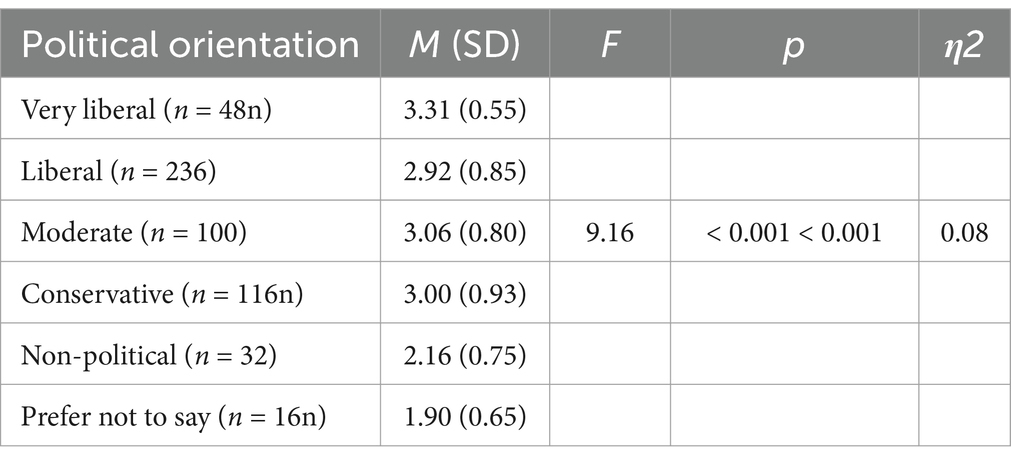

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine the effect of political orientation on willingness to speak out.

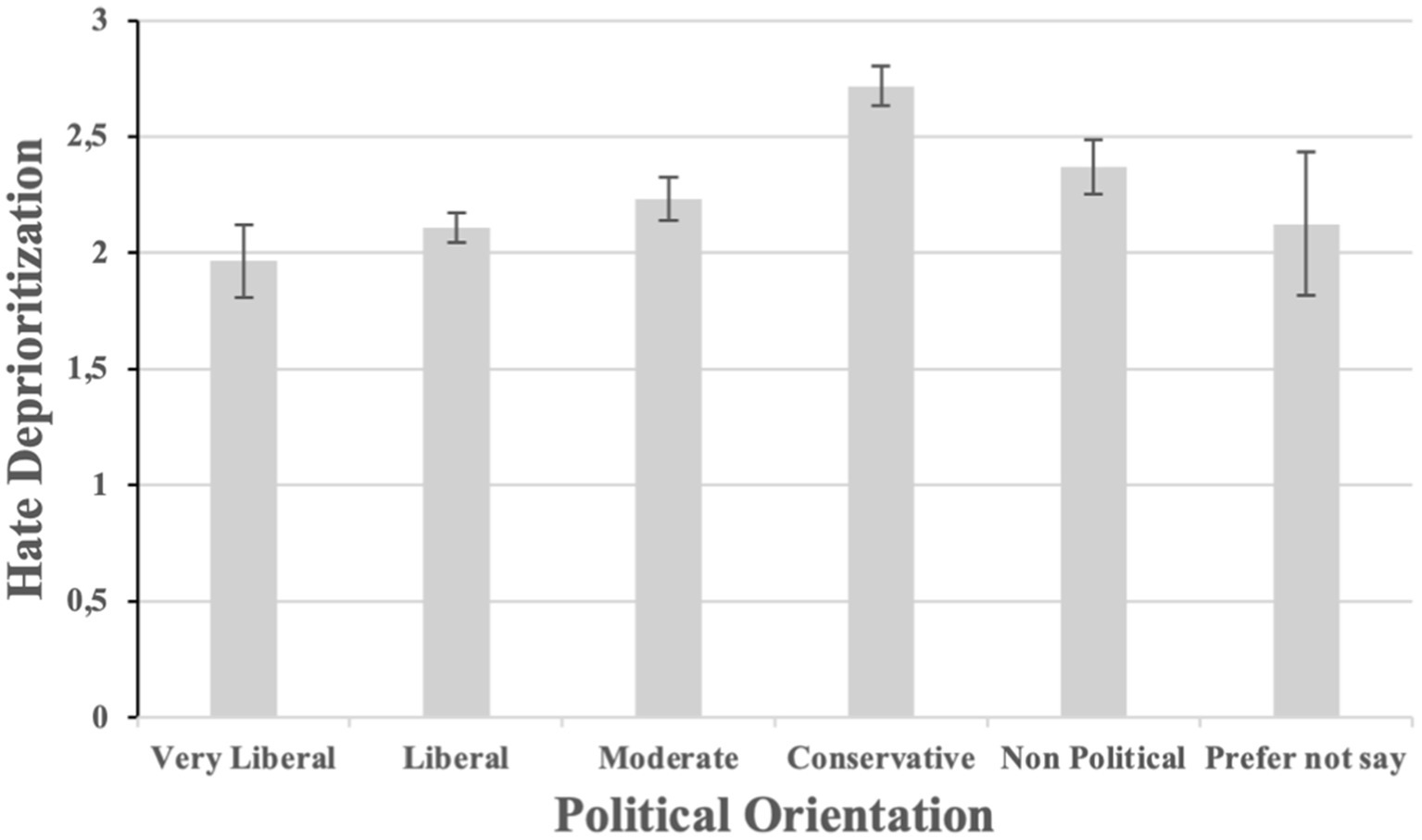

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to evaluate the effect of political orientation on the willingness to express one’s views. The results showed a significant main effect, F(5, 542) = 9.16, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.08, indicating moderate practical significance.

Post-hoc Tukey tests revealed the following:

Very liberal (M = 3.31, SD = 0.55) demonstrated a significantly higher willingness to express their views than:

Non-Political (M = 2.16, SD = 0.75): mean difference 1.15, 95% CI [0.85,1.45], indicating a large effect size (d = 1.80).

Prefer Not to Say (M = 1.90, SD = 0.65): mean difference 1.41, 95% CI [1.06,1.76], representing a large effect size (d = 2.39).

Conservatives (M = 3.00,SD = 0.93): mean difference = 0.31, 95% CI [0.05,0.57], representing a small-to-moderate effect size (d = 0.39).

Liberals (M = 2.92, SD = 0.85) also reported significantly higher willingness to speak out than:

Non-Political (M = 2.16,SD = 0.7): Mean difference = 0.760 95% CI [0.46,1.06], p < 0.05, representing a moderate effect size (d = 0.94).

Prefer Not to Say (M = 1.90,SD = 0.65): Mean difference = 1.02 95% CI [0.67,1.37], p < 0.05. representing a large effect size (d = 1.38) (Table 2).

Individuals with very liberal views demonstrated the most excellent willingness to speak out, whereas those who identified as non-political or preferred not to disclose their opinions exhibited significantly lower levels of engagement.

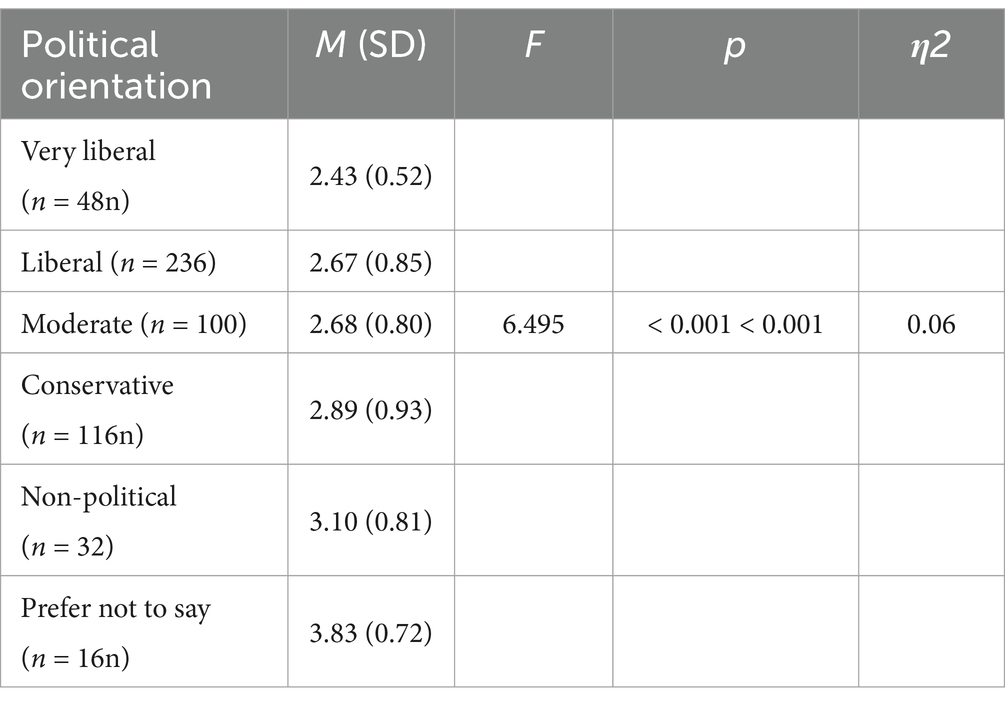

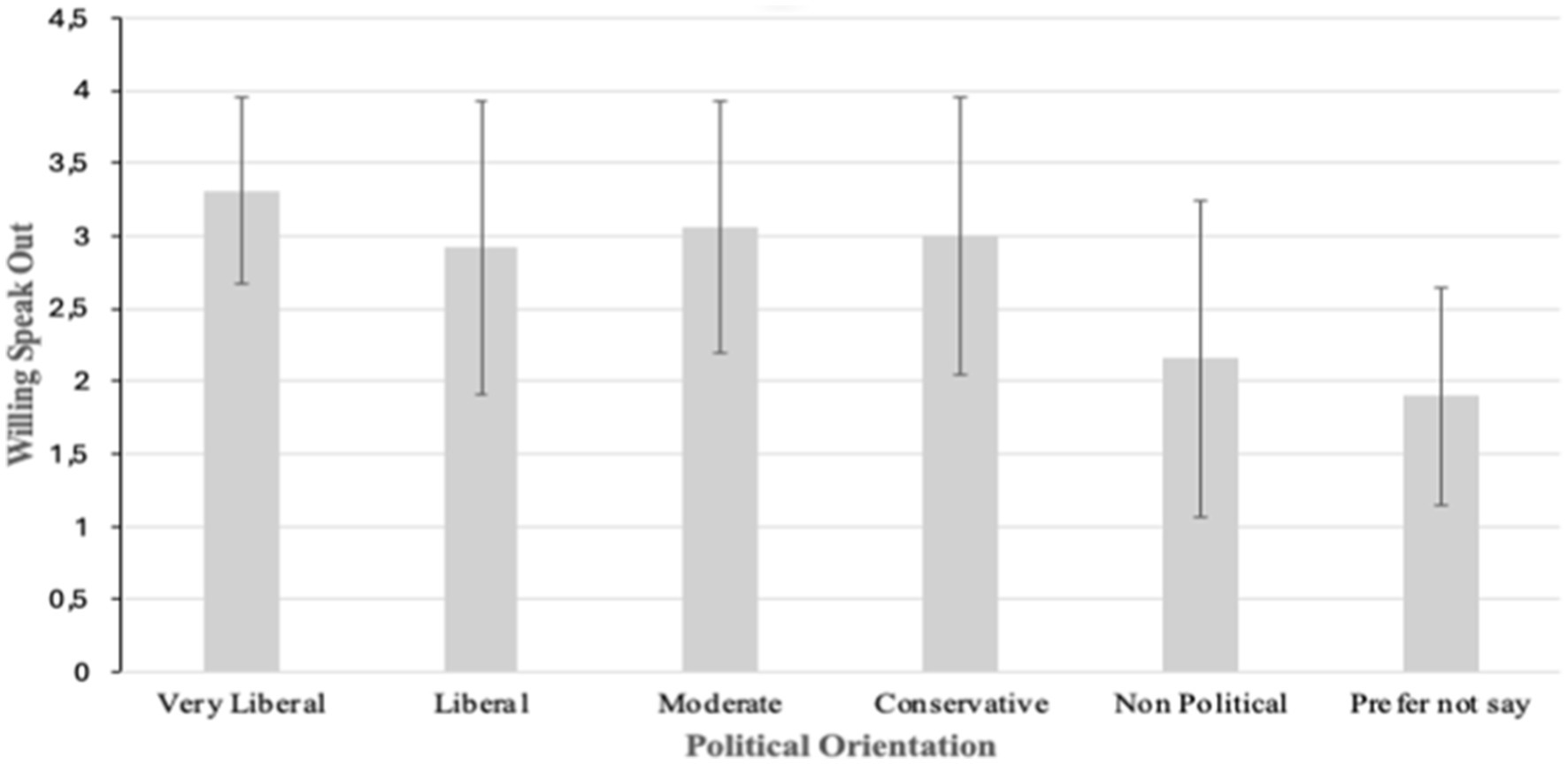

A one-way ANOVA examined the influence of political orientation on the tendency to remain silent.

A one-way ANOVA examined differences in the tendency to remain silent across political orientations, yielding a significant main effect, F(5,542) = 6.495, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.06, indicating small to moderate practical significance.

Post-hoc Tukey tests indicated the following:

Very liberal (M = 2.43, SD = 0.52) reported significantly lower tendencies to remain silent than:

Non-Political (M = 3.10, SD = 0.81): Mean difference − 0.67, 95% CI [−0.99, −0.35], large effect size (d = − 1.03).

Prefer Not to Say (M = 3.83, SD = 0.72): Mean difference − 1.40, 95% CI [−1.77, −1.03], large effect size (d = −2.41).

Conservatives (M = 2.89, SD = 0.93): Mean difference = −0.46, 95% CI [−0.78, −0.14] representing a moderate effect size (d = −0.58).

Individuals with very liberal views reported the lowest inclination to remain silent. In contrast, non-political individuals and those who prefer not to disclose their opinions demonstrated the highest levels of self-censorship.

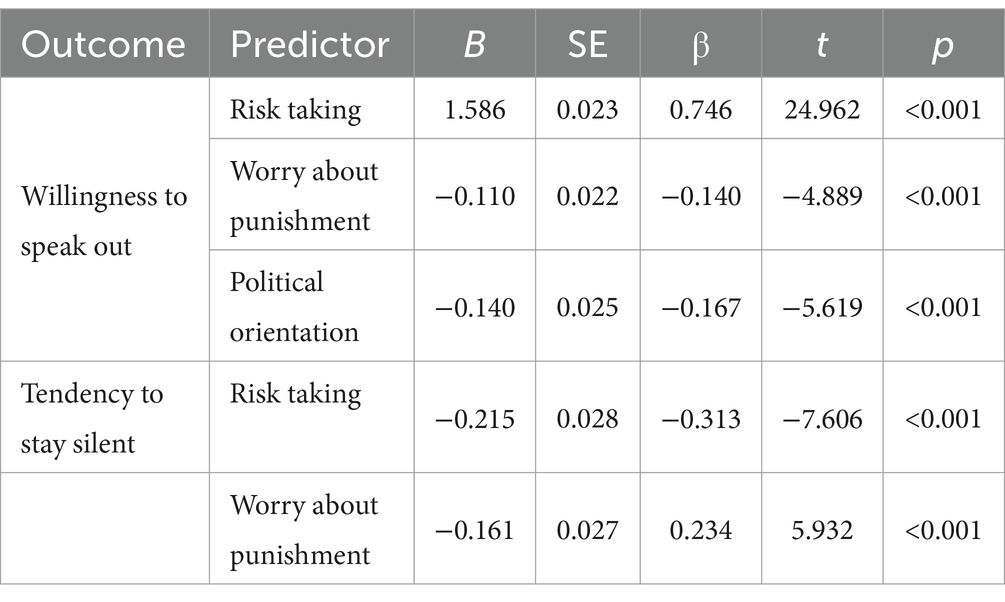

A multiple linear regression model evaluated the factors influencing the willingness to speak out and the tendency to remain silent.

Willingness to speak out

Risk perception significantly predicted greater willingness (B = 0.586, p < 0.001), 95% CI [0.52, 0.65].

Worry about punishment was negatively associated (B = −0.110, p < 0.001 95% CI [−0.15,-0.07]).

The model explained 59.1% of the variance (R2 = 0.591).

Tendency to stay silent

Lower risk perception predicted higher self-censorship (B = −0.215, p < 0.001), 95% CI [−0.27, −0.16].

Worry about punishment was positively associated (B = 0.161, p < 0.001), 95% CI [0.11, 0.22].

The model explained 20.1% of the variance (R2 = 0.201).

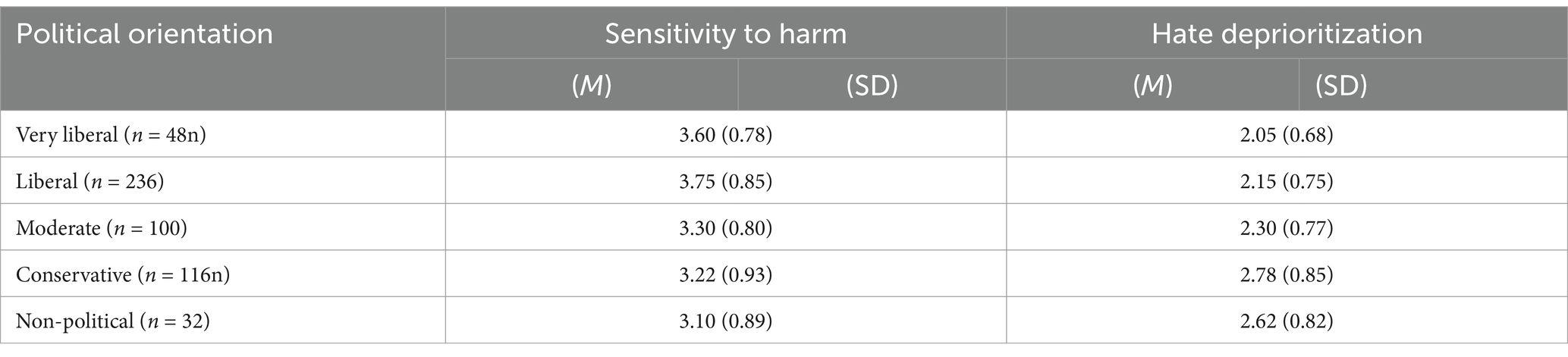

A one-way ANOVA examined the differences in sensitivity to harmful content across political orientations, F(5, 544) = 6.78, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.07.

Post-hoc Tukey tests revealed that Very Liberals (M = 3.60, SD = 0.78) and Liberals (M = 3.75, SD = 0.85) were significantly more sensitive to harm than Conservatives (M = 3.22, SD = 0.93) and Non-Political participants (M = 3.10, SD = 0.89).

Comparisons between Very Liberals and other groups revealed:

Moderates (M = 3.30, SD = 0.80): Very Liberals reported significantly higher sensitivity to content impact. Mean difference = 0.30, 95% CI [0.04,0.56], d = 0.37.

Conservatives (M = 3.22, SD = 0.93): Very Liberals also showed higher sensitivity than Conservatives. Mean difference = 0.38, 95% CI [0.06,0.70], d = 0.45.

Non-Political participants (M = 3.10,SD = 0.89): The most significant difference was observed between Very Liberal and Non-Political participants: mean difference = 0.50, 95% CI [0.17, 0.83], d = 0.62.

These results suggest that Very Liberals are consistently more sensitive to content impact than Moderates, Conservatives, and Non-Political participants, with effect sizes ranging from small to moderate.

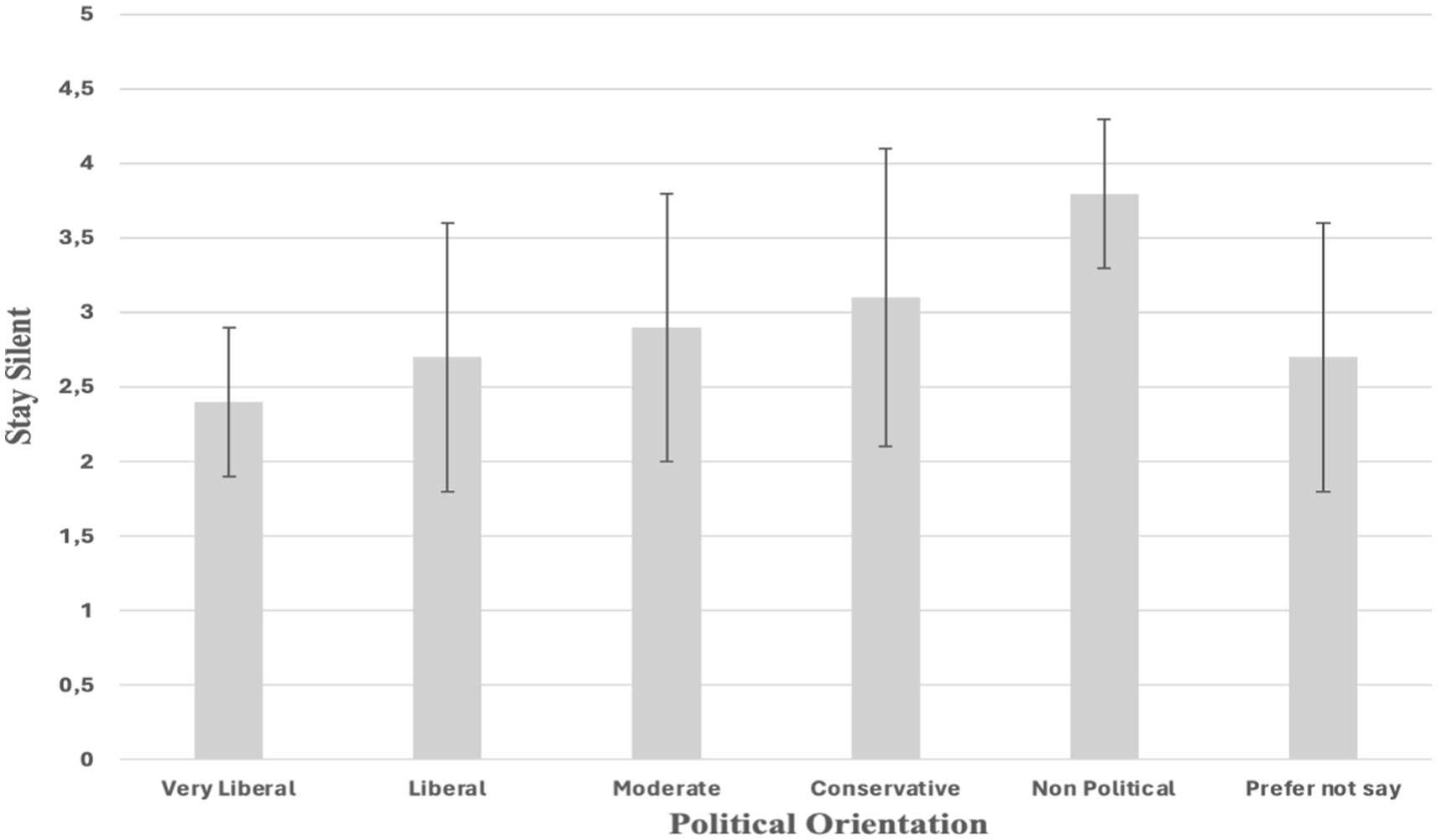

The ANOVA for hate deprioritization revealed significant differences across political orientations, F(5,544) = 8.34, p < 0.01,η2 = 0.08, indicating a moderate effect size.

Post hoc Tukey tests indicated that Conservatives (M = 2.78, SD = 0.85) and Non-Political participants (M = 2.62, SD = 0.82) exhibited the highest levels of hate deprioritization.

In contrast, Very Liberals (M = 2.05, SD = 0.68) reported significantly lower hate deprioritization levels than all other groups.

Moderates (M = 2.30, SD = 0.77): Very Liberals reported significantly lower hate deprioritization. Mean difference = 0.25, 95% CI [0.02, 0.48], d = 0.33.

Conservatives (M = 2.78, SD = 0.85): The difference between Very Liberals and Conservatives was substantial. Mean difference = 0.73, 95% CI [0.47,0.99], d = 0.94.

Non-Political participants (M = 2.62, SD = 0.82): Very Liberals differed significantly from Non-Political participants. Mean difference = 0.57, 95% CI [0.29,0.85.], d = 0.79.

These findings indicate that Very Liberals place significantly more emphasis on addressing hate-related concerns than Moderates, Conservatives, and Non-Political participants. The effect sizes ranged from small d = 0.33 to large d = 0.94.

Discussion

This unique study examines the chilling effect in the UK, emphasizing how political orientation, risk perception, regulatory ambiguity, and the government’s intent to penalize criminal online content shape online self-censorship and digital expression. Grounded in Schauer’s (1978) Chilling Effect Theory, the findings confirm that individuals’ willingness to engage in digital discourse is influenced by their political orientation, perceptions of risk, and the broader regulatory environment.

Results indicate that Very Liberal participants are the most willing to express their opinions, while Conservatives and Non-Political participants display the highest levels of self-censorship (Table 3). Risk perception further complicates these dynamics, with risk-averse individuals 28% more likely to engage in self-censorship, whereas risk-takers are significantly more inclined to partake in contentious discussions. Ambiguities within regulations, such as those in the Online Safety Act (OSA), amplify the chilling effect, particularly among Conservatives and Non-Political participants who perceive these provisions as threats to free expression. The vague definition of “legal but harmful” speech generates uncertainty, leading users to err on the side of caution. These findings reflect trends in other regulatory contexts, such as increased self-censorship in countries with ambiguous speech regulations (Burnett et al., 2022; Vogels, 2020), while offering vital insights into the unique regulatory and cultural challenges within the UK context.

This study underscores the relationship among psychological traits, political ideologies, and systemic factors, emphasizing the necessity for balanced approaches to online governance. More transparent regulatory language, clarity in moderation practices, and encouraging inclusive discourse are vital for promoting online safety while safeguarding free expression.

Political orientation and digital expression

Political orientation emerged as a critical factor in shaping online engagement, consistent with H1 and H2. Supporting H1, Very Liberal participants were the most vocal (Figure 1), concurring with previous findings that individuals with extreme political views are more likely to express their opinions online (Burnett et al., 2022; Goren et al., 2009). This trend is attributed to the stronger pull of partisan messaging, which resonates deeply with those holding ideologically extreme positions (Kashima et al., 2021). Liberals often view digital platforms as tools for systemic change, amplifying causes related to social justice and inclusivity (Burnett et al., 2022). Platforms like X and Facebook have historically reinforced these dynamics, validating progressive activism (Barberá, 2014). Interestingly, although Very Conservative was available as a response option, no participants identified with this category. While speculative, this absence may reflect a broader sociopolitical asymmetry in online expression norms. In the current UK sociopolitical climate, strong right-leaning stances are sometimes equated with far-right ideology and may carry greater reputational costs, potentially deterring open expression. By contrast, similarly extreme left-wing views appear to be more accepted within prevailing online discourses. This asymmetry is reflected in platform demographics; for instance, during the 2019 UK general election, Labour-affiliated users outnumbered Conservative users by a ratio of 2:1 on X (formerly Twitter), reinforcing an online environment that amplifies liberal perspectives while potentially suppressing dissenting voices (Blackwell et al., 2019). Conversely, as posited in H2, conservatives and non-political individuals exhibited stronger tendencies toward self-censorship (Figure 2). This finding reflects broader patterns of conservative disengagement in environments perceived as dominated by progressive norms. Gearhart and Zhang (2015) observed that conservatives often view digital platforms as unwelcoming or hostile, while Vogels (2020) highlighted how such perceptions lead to self-censorship to avoid conflict or backlash.

Figure 1. Willingness to speak out on social media by political orientation. Error bars represent standard deviations. Participants identifying as Non-Political and Prefer Not Say reported a significantly lower willingness to speak out than all other groups, with Very Liberals reporting the highest scores.

Figure 2. Tendency to stay silent on social media by Political Orientation. Error bars represent standard deviations. Participants identifying as Very Liberal had significantly lower tendencies to stay silent compared to Non-Political individuals and those who Prefer Not Say, who reported the highest levels of silence.

Although liberals are generally more vocal, they may also self-censor on issues that challenge progressive norms or critique their ideological positions. This “internal silencing” within dominant groups is consistent with findings by Mahmoudi et al. (2024), who argue that ideological silos suppress dissent even within politically dominant circles. Addressing these imbalances requires platform designs that encourage diverse perspectives across ideological divides. The influence of platform-specific and regulatory changes on ideological engagement is noteworthy.

Historically, social media platforms in the UK have been dominated by progressive voices. However, recent shifts in moderation policies on platforms like X and Meta, which have reduced censorship, could embolden conservative voices and alter longstanding patterns of discourse (Luse et al., 2025; Powers, 2025). Such changes highlight the fluidity of ideological dynamics online and the need for ongoing evaluation of how regulatory and platform decisions shape expression. These findings underscore the role of ideological dominance in reinforcing the chilling effect. Past progressive dominance on platforms like X has amplified the self-censorship of conservatives and moderates, who often fear that their views will face hostility. However, with social media increasingly prioritizing free speech over censorship, creating spaces encouraging ideological inclusivity remains critical for achieving a balanced and democratic digital discourse.

Risk perception and the chilling effect

Risk perception and worry about punishment emerged as significant predictors of social media behavior, addressing H3a, H3b, H4a, and H4b. The results indicate that a higher propensity for risk-taking predicted a greater willingness to speak out (B = 0.586, p < 0.001). In contrast, lower risk-taking (Table 4) was linked to a stronger tendency to remain silent (B = −0.215, p < 0.001). Conversely, worry about punishment was negatively associated with the willingness to speak out (B = −0.110, p < 0.001) and positively associated with a tendency to stay silent (B = 0.161, p < 0.001). Together, these predictors accounted for 59.1% of the variance in willingness to speak out (R2 = 0.591) and 20.1% of the variance in self-censorship (R2 = 0.201).

These findings concur with Schauer’s (1978) Chilling Effect Theory, illustrating how the fear of punitive consequences discourages individuals from expressing their opinions. In the UK, the ambiguity surrounding the Online Safety Act (OSA) intensifies these fears, as individuals find it challenging to discern the boundaries of “legal but harmful” speech. Heightened self-censorship among participants may also reflect the influence of high-profile cases in which the judiciary imposed swift fines and imprisonment for online posts, further fueling concerns about reputational harm, societal backlash, and legal repercussions (Anderson and Barnes, 2022; Laor, 2024; Reuters, 2024). These behaviors exemplify Panagopoulos and van der Linden’s (2017) “watchful-eye effect,” wherein perceived surveillance increases anxiety and behavioral conformity.

Risk-taking and worry were particularly significant for politically moderate and conservative participants. Risk-averse individuals tended to completely disengage from digital discourse to avoid potential repercussions, which exacerbated the chilling effect. Meanwhile, those with heightened worry and anxiety about punishment suppressed lawful and valuable contributions to public debate, reflecting patterns observed regarding algorithmic moderation and surveillance fears (Penney, 2021).

The OSA’s vague definitions heighten uncertainty compared to international frameworks like Germany’s NetzDG law and the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA). The precise mechanisms established by the NetzDG law for reporting and appealing harmful content have effectively curtailed harmful speech while minimizing overreach (Büchi et al., 2022). UK policymakers could adopt similar strategies, including clearly defining “harmful content” and implementing consistent enforcement mechanisms to alleviate fear and encourage digital engagement.

These findings underscore the critical need for regulatory clarity and proportionality to mitigate self-censorship while preserving free expression. The pervasive worry about punitive consequences reinforces self-censorship behaviors, limiting intellectual diversity and stifling democratic participation in digital spaces (Weeks et al., 2024). A balanced regulatory approach and transparent platform moderation are vital to reducing the chilling effect and enabling open dialogue in polarized online environments (Table 5).

Sensitivity to harm and hate deprioritization

This section explores how ideological beliefs influence responses to contentious online content, explicitly addressing H5, H6a, and H6b. Significant differences in sensitivity to harm and prioritization of free speech were noted across political orientations. Supporting H5, liberals (M = 3.75, SD = 0.85) and very liberals (M = 3.60, SD = 0.78) demonstrated the highest sensitivity to harmful content (Figure 3), whereas conservatives (M = 3.22, SD = 0.93) and non-political participants (M = 3.10, SD = 0.89) exhibited the least sensitivity. Similarly, H6a and H6b were confirmed, with conservatives (M = 2.78, SD = 0.85) and non-political participants (M = 2.62, SD = 0.82) prioritizing free speech over harm concerns (Figure 4), while liberals and very liberals (M = 2.15, SD = 0.75; M = 2.05, SD = 0.68) concentrated on harm mitigation. These differences were statistically significant (p < 0.01).

Liberals’ sensitivity to harm reflects their emphasis on care and fairness, consistent with the Moral Foundations Theory (Haidt, 2012). This sensitivity reflects their preference for stricter moderation policies to reduce harm caused by discriminatory or inciting content (Burnett et al., 2022). Conversely, conservatives’ prioritization of free speech highlights their focus on procedural justice and autonomy, which leads to skepticism about regulatory overreach (Feldman, 2003; Wilhelm and Joeckel, 2019).

The findings further underscore ideological divides in interpreting contentious posts. Liberals and very liberal individuals perceived such posts as inciting harm and strongly favored moderation. Conversely, conservatives and non-political participants regarded the identical posts as controversial yet permissible, reinforcing their focus on individual liberty (Bilewicz et al., 2017; Dellagiacoma et al., 2024). These interpretations illustrate how moral and ideological values shape perceptions of harm and regulatory needs.

Psychological mechanisms such as threat perception and in-group/out-group dynamics exacerbate these divides. Conservatives often perceive regulations as disproportionately targeting their perspectives, resulting in resistance and marginalization (Weeks et al., 2024). In contrast, liberals view harmful speech as an attack on their values or marginalized groups, which drives stronger support for punitive measures (Burnett et al., 2022; Vogels, 2020).

The UK’s regulatory environment heightens tensions as government efforts to hold platforms accountable for harmful content polarize debates around free speech and harm reduction. Liberals regard regulation as vital for inclusivity, while conservatives consider it an overreach that stifles legitimate expression (Amnesty International, 2024; Büchi et al., 2022). These dynamics illustrate broader ideological conflicts between freedom and fairness.

Algorithmic amplification deepens divisions by prioritizing progressive narratives or right-leaning views (González-Bailón et al., 2022) while marginalizing opposing perspectives (Barberá, 2014). However, interventions such as Reddit’s community-driven moderation and Instagram’s customizable feeds offer potential solutions (Chandrasekharan et al., 2022). Reddit permits users to influence content visibility, and Instagram reduces bias by enabling users to personalize their experiences. Expanding such measures could assist in balancing content visibility across ideological divides.

Policymakers must tackle these challenges by clarifying terms such as “harmful content” and ensuring transparent enforcement. Algorithmic accountability and proportionate moderation are vital to creating inclusive, balanced digital spaces that allow diverse perspectives to flourish.

Limitations and future research

While this study provides valuable insights into self-censorship, political orientation, and risk perception in online spaces, limitations warrant discussion. The reliance on convenience sampling likely skewed the sample towards politically engaged individuals, potentially underrepresenting self-censorship behaviors among less politically active users. Additionally, although the sample included a range of political orientations, it lacked sufficient representation from “Very Conservative” participants, which may have restricted the study’s ability to capture ideological variations in self-censorship fully.

Future research could address these gaps by employing stratified sampling to ensure balanced representation across demographic and ideological groups. Engaging community networks and general-interest platforms targeting less politically active populations and implementing demographic quotas could enhance inclusivity and provide a more comprehensive understanding of self-censorship dynamics.

This study acknowledges the relevance of contemporary theories, such as the Digital Panopticon (Lynch, 2024; Manokha, 2018), in understanding how perceptions of surveillance influence online behavior. These theories emphasize the internalization of constant monitoring by governments or platforms and how this shapes individuals’ willingness to engage in political discourse. They provide a valuable perspective on how perceptions of surveillance may influence online behavior, complementing the Chilling Effect Theory and the Spiral of Silence framework used in this research. Integrating these perspectives into future analyses could deepen understanding of the relationship between political orientation, risk perception, and self-censorship.

Methodologically, although the quantitative approach yielded robust statistical insights, subsequent qualitative interviews could complement these findings by uncovering the decision-making processes underlying self-censorship. Such interviews would provide rich contextual data on how individuals navigate online expression in politically charged environments, revealing perspectives that quantitative measures may not capture.

Revising the “intent” construct within the Brandenburg Test framework could improve reliability by integrating additional validated measures such as behavioral intention scales or scenario-based assessments. These enhancements would provide more nuanced insights into how individuals interpret and respond to online content, thus strengthening the validity of future research in this area.

This study focused on individuals’ perceptions and behaviors but did not examine how platform-specific features, such as algorithmic moderation, influence self-censorship dynamics. Future research could investigate how tools like Instagram’s anti-harassment filters or Reddit’s community-driven moderation systems impact users’ willingness to express opinions. Such inquiries would provide actionable insights for platform design and inform regulatory policy.

Expanding the study beyond the UK through cross-national or longitudinal designs could illuminate how evolving regulatory frameworks and public attitudes influence global self-censorship. By addressing these opportunities, future research can build on this study’s foundation, advancing the theoretical, methodological, and practical understanding of self-censorship in digital spaces.

Conclusion

This study deepens the understanding of political psychology in digital environments by examining how regulatory ambiguity, political orientation, government mandates, and perceptions of risk influence self-censorship and online expression. At a time when social media platforms play a pivotal role in political discourse, these findings provide valuable insights into the psychological processes that underpin the chilling effect.

This research focuses on the UK and addresses a gap in a field often dominated by studies centered on the U.S. It highlights the influence of regulatory frameworks, such as the Online Safety Act, in a context that provides fewer constitutional protections for online speech. The study enhances theories of the chilling effect and spiral of silence by offering empirical evidence on how political beliefs affect the willingness to speak out or remain silent.

The findings hold significance for policymakers and platform designers. Clear regulatory definitions and consistent enforcement mechanisms are urgently required to alleviate uncertainty and build trust in content moderation. Standardized protocols and accessible appeals processes would reassure users and encourage their participation. Platforms should introduce tools that provide immediate feedback on harmful posts and promote digital literacy, encouraging constructive engagement.

This study reveals ideological differences, with liberals demonstrating greater sensitivity to harm and conservatives prioritizing free expression. These insights deepen our understanding of how political ideologies shape responses to regulatory ambiguity and contentious content.

This research enhances understanding of the chilling effect in the UK. It offers practical guidance for cultivating balanced digital environments where diverse perspectives can flourish without fear of censorship or reprisal.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Portsmouth Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NAD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Amnesty International. (2024) UK: letter from leading rights groups warn government of “chilling effect” on protests. Amnesty International UK. Available at: https://www.amnesty.org.uk/press-releases/uk-letter-leading-rights-groups-warn-government-chilling-effect-protests (Accessed December 20, 2024).

Anderson, L., and Barnes, M. (2022). Hate speech. Stanf. Encycl. Philos. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/hate-speech/ (Accessed December 20, 2024).

Barberá, P. (2014). How social media reduces mass political polarisation. Evidence from Germany, Spain, and the US. Job Market Paper, New York University, 46, 1–46.

Bilewicz, M., Soral, W., Marchlewska, M., and Winiewski, M. (2017). When authoritarians confront prejudice. Differential effects of SDO and RWA on support for hate-speech prohibition. Polit. Psychol. 38, 87–99. doi: 10.1111/pops.12313

Blackwell, J., Fowler, B., and Fox, R. (2019). Audit o f political engagement 16:The 2019 report, vol. 16. London: Hansard Society, 1–53.

Brown, N. I., and Peters, J. (2018), Say this not that: government regulation and control of social media. Available at: https://heinonline.org/. https://lawreview.syr.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/I-Brown-and-Peters-FINAL-v3.pdf (Accessed December 3, 2024).

Büchi, M., Festic, N., and Latzer, M. (2022). The chilling effects of digital Dataveillance: a theoretical model and an empirical research agenda. Big Data Soc. 9:205395172110653. doi: 10.1177/20539517211065368

Burnett, A., Knighton, D., and Wilson, C. (2022). The self-censoring majority: how political identity and ideology impacts willingness to self-censor and fear of isolation in the United States. Social Media Soc. 8:205630512211230. doi: 10.1177/20563051221123031

Chandrasekharan, E., Jhaver, S., Bruckman, A., and Gilbert, E. (2022). Quarantined! Examining the effects of a community-wide moderation intervention on Reddit. ACM Transac. Comput. Hum. Interact. 29, 1–26. doi: 10.1145/3490499

Chin-Rothmann, C., Rajic, T., and Brown, E. (2023). A new chapter in content moderation: Unpacking the UK online safety bill. CSIS. Available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/new-chapter-content-moderation-unpacking-uk-online-safety-bill (Accessed January 3, 2025).

Cieslikowski, J. (2023). UK police’s speech-chilling practice of tracking “non-crime hate incidents.” The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. Available at: https://www.thefire.org/news/uk-polices-speech-chilling-practice-tracking-non-crime-hate-incidents (Accessed January 3, 2025).

Cinelli, M., De Francisci Morales, G., Galeazzi, A., Quattrociocchi, W., and Starnini, M. (2021). The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118:e2023301118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2023301118

Coe, P. (2022). The draft online safety bill and the regulation of hate speech: have we opened Pandora’s box? J. media Law 14, 50–75. doi: 10.1080/17577632.2022.2083870

Crawford, J. T., and Pilanski, J. M. (2012). Political intolerance, right and left. Polit. Psychol. 35, 841–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00926.x

Das, S., and Kramer, A. (2021). Self-censorship on Facebook. Proceed. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 7, 120–127. doi: 10.1609/icwsm.v7i1.14412

Dellagiacoma, L., Geschke, D., and Rothmund, T. (2024). Ideological attitudes predicting online hate speech: the differential effects of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation. Front. Soc. Psychol. 2:1389437. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2024.1389437

Elad-Strenger, J., Goldenberg, A., Saguy, T., and Halperin, E. (2024). How our ideological out-group shapes our emotional response to our shared socio-political reality. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 63, 723–744. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12701

Feldman, S. (2003). Enforcing social conformity: a theory of authoritarianism. Polit. Psychol. 24, 41–74. doi: 10.1111/0162-895x.00316

Fletcher, R. (2024). Which social networks did political parties use most in 2024? UK Election Analysis. Available at: https://www.electionanalysis.uk/uk-election-analysis-2024/section-6-the-digital-campaign/which-social-networks-did-political-parties-use-most-in-2024/ (Accessed January 3, 2025).

Gavrielides, T. (2012). Contextualizing restorative justice for hate crime. J. Interpers. Violence 27, 3624–3643. doi: 10.1177/0886260512447575

Gearhart, S., and Zhang, W. (2015). “Was it something I said?” “no, it was something you posted!” a study of the spiral of silence theory in social media contexts. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 18, 208–213. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0443

González-Bailón, S., d’Andrea, V., Freelon, D., and De Domenico, M. (2022). The advantage of the right in social media news sharing. PNAS Nexus 1:137. doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac137

Goren, P., Federico, C. M., and Kittilson, M. C. (2009). Source cues, partisan identities, and political value expression. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 53, 805–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00402.x

Gorrell, G., Roberts, I., Greenwood, M. A., Bakir, M. E., Iavarone, B., and Bontcheva, K. (2018). Quantifying media influence and partisan attention on twitter during the UK EU referendum. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci 11185, 274–290. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-01129-1_17

GOV.UK. (2024). Police recorded crime and outcomes open data tables user guide. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/police-recorded-crime-open-data-tables/police-recorded-crime-and-outcomes-open-data-tables-user-guide (Accessed January 3, 2025).

Haidt, J. (2012). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. New York: Pantheon.

Hampton, K., Lu, W., Dwyer, M., Shin, I., and Purcell, K. (2014). Social media and the ‘spiral of silence’. Washington, DC.: Pew Research Center.

Healy, T. (2009). Brandenburg in a time of terror - NDLScholarship. The Notre Dame Law Review. Available at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1201&context=ndlr (Accessed December 3, 2024).

Ho, S. S., and McLeod, D. M. (2008). Social-psychological influences on opinion expression in face-to-face and computer-mediated communication. Commun. Res. 35, 190–207. doi: 10.1177/0093650207313159

Huddy, L., Feldman, S., and Weber, C. (2008). The political consequences of perceived threat and felt insecurity. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 614, 131–153. doi: 10.1177/0002716207305951

Institute of Economic Affairs. (2024). The Battle for truth: Social media, riots, and freedom of expression. The Battle for Truth: Social Media, Riots, and Freedom of Expression. Available at: https://insider.iea.org.uk/p/the-battle-for-truth-social-media (Accessed January 3, 2025).

Judiciary.uk. (2024). Rex -V- Lucy Connolly. Courts and Tribunals Judiciary. Available at: https://www.judiciary.uk/judgments/rex-v-lucy-connelly/ (Accessed January 3, 2025).

Kashima, Y., Perfors, A., Ferdinand, V., and Pattenden, E. (2021). Ideology, communication, and polarisation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 376:20200133. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2020.0133

Kemp, S. (2024). Digital 2024: the United Kingdom - DataReportal – global digital insights. DataReportal. Available at: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-united-kingdom (Accessed December 20, 2024).

Kim, S. (2017). Spiral of silence: fear of isolation and willingness to speak out. Int. Encyclop. Media Effects 1–9. doi: 10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0037

Laor, T. (2024). Breaking the silence: the role of social media in fostering community and challenging the spiral of silence. Online Inf. Rev. 48, 710–724. doi: 10.1108/OIR-06-2023-0273

Lee, H., Oshita, T., Oh, H. J., and Hove, T. (2014). When do people speak out? Integrating the spiral of silence and the situational theory of problem solving. J. Public Relat. Res. 26, 185–199. doi: 10.1080/1062726x.2013.864243

Leets, L. (2001). Responses to internet hate sites: is speech too free in cyberspace? Commun. Law Policy 6, 287–317. doi: 10.1207/s15326926clp0602_2

Lei Nguyen, O. O. (2021). The rise of digital extremism: how social media eroded america’s political stability. IVolunteer Int. Retrieved December 3, 2024, from https://www.ivint.org/the-rise-of-digital-extremism-how-social-mediaeroded-americas-political-stability/

Luse, B., Jingnan, H., Rose, C. A., Girdwood, B., Romero, J., and Williams, V. (2025). Is fact-checking “censorship?” why Meta’s changes are a win for conservatives. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2025/01/17/1225172096/meta-free-speech-zuckerberg

Lynch, K. (2024). The digital Panopticon: how online communities enforce conformity. Virginia Review of Politics. https://virginiapolitics.org/online/2021/12/4/the-digital-panopticon-how-online-communities-enforce-conformity (Accessed January 3, 2025).

Mahmoudi, A., Jemielniak, D., and Ciechanowski, L. (2024). IEEE Access. IEEE Access. Piscataway, NJ. 12, 9594–9620. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3353054

Manokha, I. (2018). Surveillance, panopticism, and self-discipline in the digital age. Surveill. Soc. 16, 219–237. doi: 10.24908/ss.v16i2.8346

Marder, B., Joinson, A., Shankar, A., and Houghton, D. (2016). The extended ‘chilling’ effect of Facebook: the cold reality of ubiquitous social networking. Comput. Hum. Behav. 60, 582–592. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.097

McLaughlin, S. (2024). UK government issues warning: “think before you post.” The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. https://www.thefire.org/news/uk-government-issues-warning-think-you-post (Accessed January 3, 2025).

Mikelionis, L. (2024). UK government accused of cracking down on free speech: “think before you post.” WFIW FM/WFIW AM/WOKZ-FM. Available at: https://www.wfiwradio.com/2024/09/14/uk-government-accused-of-cracking-down-on-free-speech-think-before-you-post/ (Accessed January 3, 2025).

Neubaum, G., and Krämer, N. C. (2018). What do we fear? Expected sanctions for expressing minority opinions in offline and online communication. Commun. Res. 45, 139–164. doi: 10.1177/0093650215623837

Newling, D. (2024). What are the new offences under the online safety act 2023?. Hickman & Rose Solicitors - London. Available at: https://www.hickmanandrose.co.uk/what-are-the-new-offences-under-the-online-safety-act-2023/ (Accessed December 20, 2024).

Noelle-Neumann, E. (1974). The spiral of silence: a theory of public opinion. J. Commun. 24, 43–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1974.tb00367.x

O’Shiel, C., Marlow, R., Price, C., and Flanagan, N. (2023). The online safety act in focus: key challenges, implementation, and navigating Ofcom’s approach. The online safety act in focus: key challenges, implementation, and navigating ofcom’s approach. https://www.algoodbody.com/insights-publications/the-online-safety-act-in-focus-key-challenges-implementation-and-navigating-ofcoms-approach (Accessed December 20, 2024).

Panagopoulos, C., and van der Linden, S. (2017). The feeling of being watched: do eye cues elicit negative affect? N. Am. J. Psychol. 19, 113–122.

Penney, J. (2020). Online abuse, chilling effects, and human rights. Citizenship in a connected Canada: A research and policy agenda. Ottawa, ON: University of Ottawa Press.

Penney, J. W. (2021). Understanding chilling effects. Minn. L. Rev. 106:1451. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3855619

Powers, C. (2025). Zuckerberg calls on us to defend tech companies against European “censorship.” Available at: https://www.euractiv.com/section/tech/news/zuckerberg-calls-on-us-to-defend-tech-companies-against-european-censorship/ (Accessed January 12, 2025).

Reuters. (2024). More than 1,000 arrested following UK riots, police say|Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/more-than-1000-arrested-following-uk-riots-police-say-2024-08-13/ (Accessed January 12, 2025).

Sap, M., Swayamdipta, S., Vianna, L., Zhou, X., Choi, Y., and Smith, N. (2022). Annotators with attitudes: How annotator beliefs and identities bias toxic language detection. Proceedings of the 2022 conference of the north American chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human language technologies

Schauer, F. (1978). Fear, risk and the first amendment: unraveling the chilling effect. BUL Rev. 58:685.

Stoycheff, E. (2016). Under Surveillance. J. Mass Commun. Q. 93, 296–311. doi: 10.1177/1077699016630255

Suciu, P. (2022). Social media and the midterms – are the platforms doing enough to address the spread of misinformation?. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/petersuciu/2022/10/07/social-media-and-the-midterms--are-the-platforms-doing-enough-to-address-the-spread-of-misinformation/?sh=1c304dd75b7e

Sunstein, C. (2018). Republic: divided democracy in the age of social media. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

The Week. (2024). When is an offensive social media post a crime? UK legal system walks a “difficult tightrope” between defending free speech and prosecuting hate speech. The Explainer. https://theweek.com/law/when-is-an-offensive-social-media-post-a-crime (Accessed January 3, 2025).

Vogels, E. A. (2020). Partisans in the U.S. increasingly divided on whether offensive content online is taken seriously enough. Washington, DC.: Pew Research Center.

Warrender, E. (2023). The online safety bill will endanger LGBTQ+ people on a global scale. Open Access Government. https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/the-online-safety-bill-will-endanger-lgbtq-people-on-a-global-scale/165913/ (Accessed December 20, 2024).

Weeks, B. E., Halversen, A., and Neubaum, G. (2024). Too scared to share? Fear of social sanctions for political expression on social media. Journal of computer-mediated. J. Comp. Mediated Commun. 29, 4–7. doi: 10.1093/jcmc/zmad041

Wilhelm, C., and Joeckel, S. (2019). Gendered morality and backlash effects in online discussions: an experimental study on how users respond to hate speech comments against women and sexual minorities. Sex Roles 80, 381–392. doi: 10.1007/s11199-018-0941-5

Zaugg, J. (2024). British far-right groups fuel violence at riots. Le Monde.fr. Available at: https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2024/08/04/british-far-right-groups-fuel-violence-at-riots_6708998_4.html (Accessed January 3, 2025).

Zillmann, D. (2010). “Mechanisms of emotional reactivity to media entertainments” in The Routledge handbook of emotions and mass media. (eds.). K. Döveling, C. von Scheve, and E. A. Konijn (London: Routledge), 115–129.

Keywords: social media, chilling effect, free speech, government regulation, political orientation, content sensitivity, spiral of silence

Citation: Daruwala NA (2025) Social media, expression, and online engagement: a psychological analysis of digital communication and the chilling effect in the UK. Front. Commun. 10:1565289. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1565289

Edited by:

Temple Uwalaka, University of Canberra, AustraliaReviewed by:

Sarah Joe, Rivers State University, NigeriaAlem Febri Sonni, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Daruwala. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Neil Anthony Daruwala, bmVpbC5kYXJ1d2FsYUBwb3J0LmFjLnVr

Neil Anthony Daruwala

Neil Anthony Daruwala