- De Montfort University, Leicester, United Kingdom

Transnational education (TNE) creates a dynamic intercultural space where students, staff, managers, and regulators engage with diverse norms, expectations, and institutional practices across borders. The intercultural challenges embedded in TNE remain underexplored in both research and policy. This study introduces the Triple-A TNE Partnership Framework—agility, adaptability, and alignment—as an empirically grounded conceptual model for navigating these complexities. Drawing on a multi-source dataset—123 student surveys, 67 responses from staff, managers, and regulators, 55 parent surveys, 108 regulatory TNE review reports, and 12 in-depth interviews—this study examines how institutions respond to disruption, negotiate structural differences, and manage competing priorities. Agility supports timely, trust-building responses to change. Adaptability enables context-sensitive teaching, assessment, and governance. Alignment fosters coherence among institutional goals, stakeholder roles, and incentive systems. Together, these capabilities offer a practical and theoretically grounded approach to intercultural engagement. The findings also highlight the need for formal institutional support for those delivering TNE. The Triple-A framework provides institutions and regulators with a clear foundation for building successful and sustainable TNE partnerships in an increasingly complex and interconnected global landscape.

1 Introduction

Transnational education (TNE), which enables students to pursue foreign degrees while remaining in their home country or region, has become a key pillar of global higher education. Defined as the cross-border mobility of academic programs and institutions, TNE encompasses various models, such as dual degrees and international branch campuses (IBCs) (Knight, 2016). More than 333 international campuses have been established worldwide, set up by 39 home countries in 83 host countries (Cross-Border Education Research Team, 2023). This expansion reflects a growing demand for accessible and flexible international education opportunities. The UK, a leader in TNE, reported 606,485 TNE students in 228 countries and territories for the 2022–23 academic year, supported by 173 higher education providers (Universities UK, 2025). Similarly, countries like Australia, the UK, and the USA have leveraged TNE as both an educational initiative and an economic strategy. For example, TNE programs in the UK alone generated £2.4 billion in revenue in 2021 (Department for Education, 2024). Beyond its economic impact, TNE plays a significant role in addressing institutional gaps in regions with limited higher education opportunities. For instance, countries like Sri Lanka have strategically used TNE to expand access to quality education, which has resulted in rapid enrolment growth in recent years.

TNE fosters a dynamic intercultural space where students, staff, and institutions navigate the complexities of differing norms, expectations, and practices between sending and host countries. This interplay of global and local dynamics highlights the need for robust frameworks to address tensions and promote sustainable partnerships. To meet these challenges, this study introduces the Triple-A TNE Partnership framework, built on the pillars of agility, adaptability, and alignment. Following a literature review, I describe the study’s methodology, outline the framework, and present findings on intercultural challenges related to its three pillars. The article further situates these findings within existing theories to offer practical insights into how TNE partnerships can overcome intercultural challenges and achieve long-term sustainability.

2 Literature review

2.1 Defining TNE

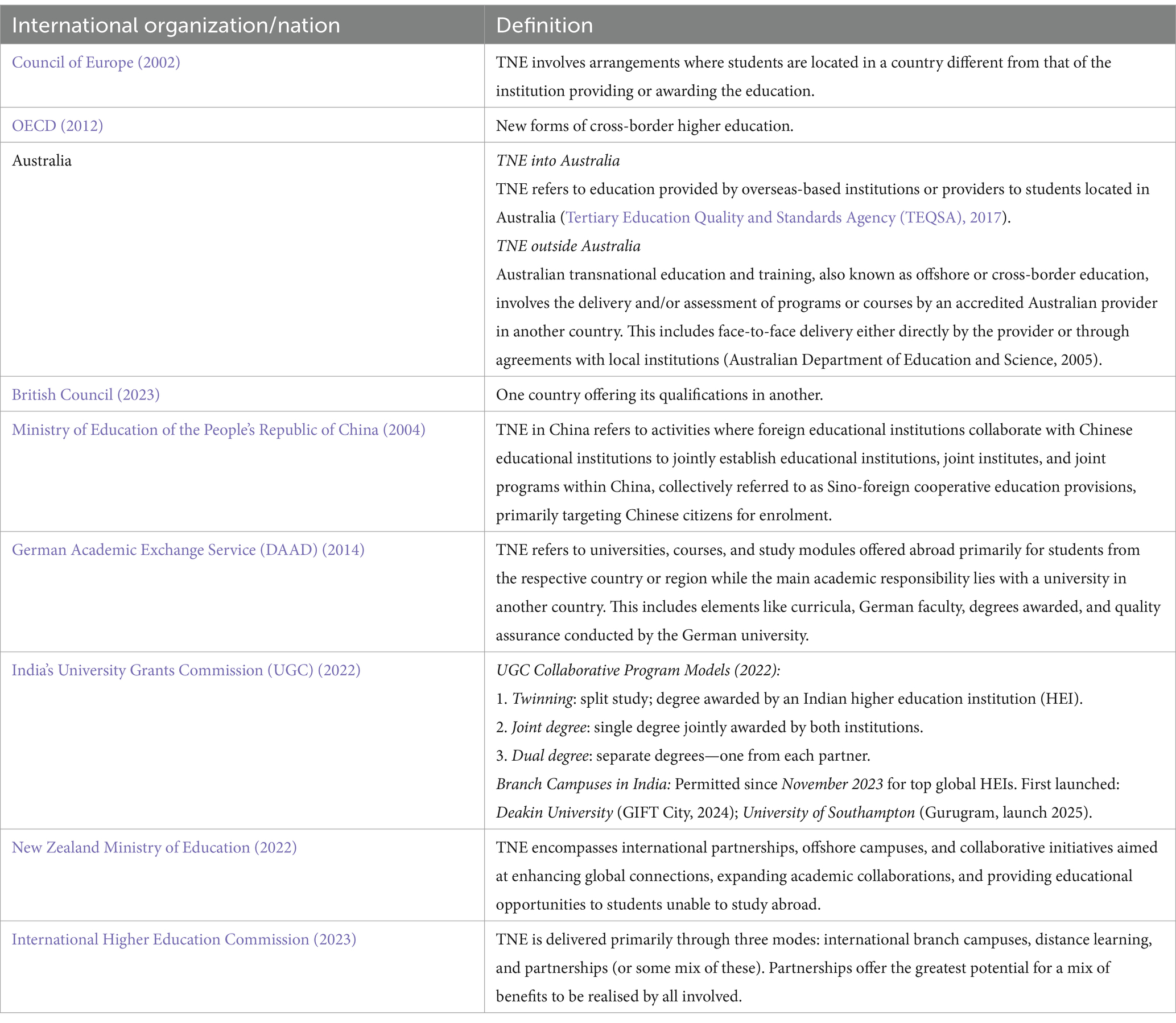

Transnational higher education (TNHE, but more commonly known as TNE) broadly refers to the cross-border mobility of higher education programs and institutions. It allows students to obtain foreign qualifications while remaining in their home country or region (Knight, 2016; Carter, 2024). Despite variations in national regulatory frameworks, there is consensus that TNE entails offshore program delivery and international collaboration (Council of Europe, 2002; OECD, 2012). Table 1 presents how major international organizations and selected countries define TNE.

Across these definitions, shared principles include cross-border delivery, institutional quality assurance, and expanding access to globally recognized qualifications. While some systems centralize oversight (e.g., China), others such as the United States operate institutionally rather than through national frameworks (Branch, 2018).

2.2 Typologies and models of TNE

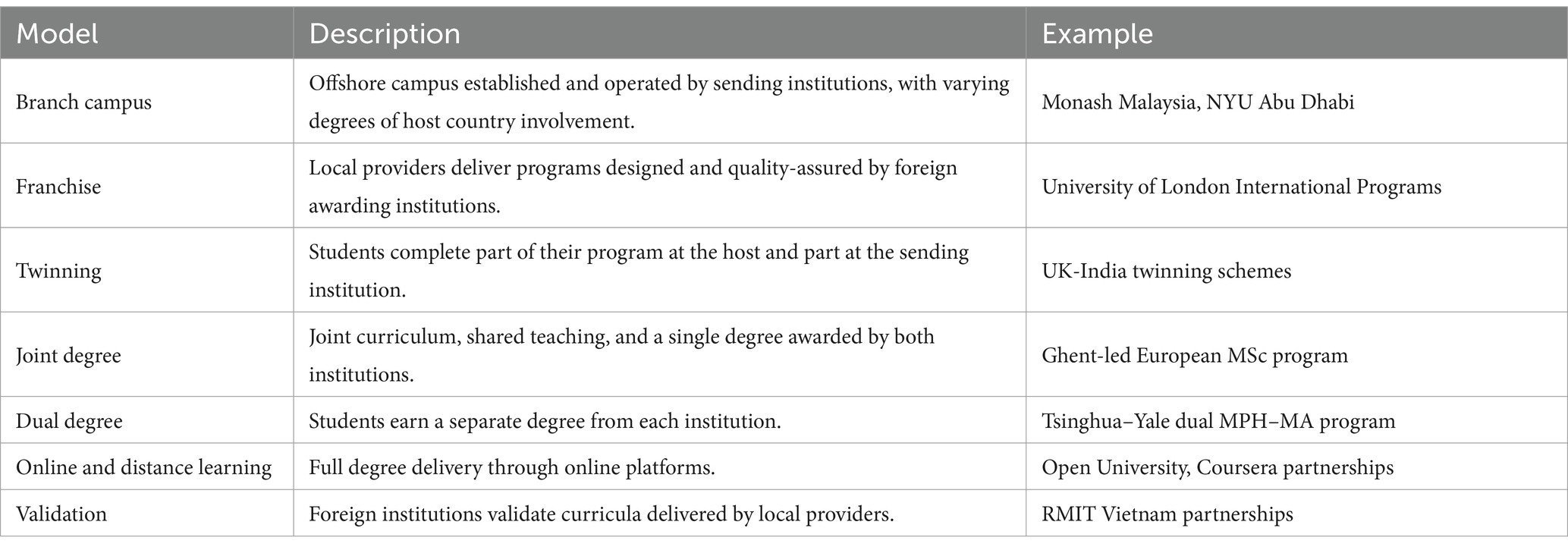

TNE operates through a range of models, most notably IBCs, franchising, validation, joint/dual degrees, joint colleges/institutes, and online learning (see Table 2 for a summary). Knight (2016) distinguishes between independent and collaborative TNE, a typology refined by Knight and McNamara (2017) and challenged by Tran et al. (2023), who argue for a continuum model that captures growing hybridity in TNE (Table 2).

Table 2. Typologies of TNE delivery models (adapted from Knight, 2016; Tran et al., 2023).

Tsiligiris (2025) also notes a shift toward more complex and advanced forms of TNE that require greater strategic alignment, institutional investment, and intercultural competence. As TNE models evolve, universities are expected to deepen local partnerships while maintaining global academic standards and thereby to position TNE as a key site of internationalization.

2.2.1 Independent TNE

Independent TNE models, particularly in their more centralized forms, are characterized by the sending institution’s full control over academic provision and governance. These arrangements often take the form of IBCs, franchising agreements, or distance learning programs, in which local partners have limited involvement in curriculum design or quality assurance. For example, Monash University Malaysia—established in 1998 through a joint venture with the Sunway Group—became wholly owned by Monash University in 2020, consolidating its academic and operational oversight. Similarly, Lancaster University Leipzig operates as a branch campus of Lancaster University in the UK. While Lancaster retains academic control over its degree programs, Navitas delivers the Lancaster-accredited foundation program and manages non-academic services such as facilities, student recruitment, and administrative support. These models help ensure brand consistency and uphold academic standards, but they may struggle to respond quickly to local educational contexts and cultural differences (Knight and McNamara, 2017).

2.2.2 Collaborative TNE

Collaborative models involve substantial co-development and co-governance between partner institutions. This includes joint curriculum design, teaching, and shared governance boards. Xi’an Jiaotong–Liverpool University and NYU Shanghai exemplify high-integration models with cross-cultural staffing and joint management. These partnerships are lauded for fostering mutual capacity building and contextual relevance (Tran et al., 2023), but they must also navigate complex regulatory differences, cultural expectations, and divergent standards of academic practice (Lane et al., 2024).

2.2.3 Continuum of TNE models

In reality, many TNE initiatives fall between the extremes of independent and collaborative models. A continuum approach better captures the evolving nature of partnerships, which may become more or less collaborative over time in response to shifting strategic priorities or external pressures (Kosmützky and Putty, 2016). For instance, franchised programs may gradually shift toward joint degrees, and centrally controlled branch campuses may increase local stakeholder involvement. This fluidity highlights the need for a flexible, nuanced framework for analyzing TNE arrangements.

2.3 Intercultural challenges in TNE

A key yet under-theorized dimension of TNE lies in its intercultural interface—between students, staff, and institutional partners. The term “intercultural” is often taken to mean national cultural differences, but in practice, individuals navigate overlapping and shifting identities—ethnic, institutional, linguistic, and professional. These layered identities defy simple binaries and complicate assumptions about cultural categories (Wang, 2018; Wang, 2023).

Recent scholarship has moved away from essentialist views of culture toward what Dervin (2016, 2023) calls a realist interculturality approach. Rather than treating culture as a static attribute, this approach focuses on how people experience, interpret, and navigate difference in real-world contexts. Building on this stance, the present study does not predefine intercultural challenges but instead analyzes how stakeholders describe and respond to them.

In this article, “intercultural” refers to the dynamic and situated interactions across cultural, institutional, and linguistic boundaries within TNE settings. Unlike international students who relocate abroad, TNE students typically remain in their home countries. As a result, they often lack immersive cross-cultural experiences while still encountering the expectations of a foreign academic model. Despite their growing numbers, these students remain relatively under-researched (Carter, 2024; Mittelmeier et al., 2024; Lane et al., 2025).

Empirical and audit data from this study—as well as prior work such as Dai and Garcia (2019)—show that TNE students experience identity shifts, institutional friction, and varying degrees of agency. These emerge as they navigate divergent pedagogical traditions, misaligned expectations, and limited cross-cultural exposure. The UK’s Quality Assurance Agency (QAA, 2020) emphasizes the persistent challenge of balancing the principles of the awarding institution with respect for local cultures. Similarly, Heffernan et al. (2010) and Montgomery (2014) highlight issues such as learning style mismatch and limited adaptation of fly-in faculty.

Tensions in TNE are not limited to pedagogy. Hill et al. (2014) document significant micro-level tensions in collaborative partnerships, including disagreements over fee structures, marketing responsibilities, staff roles, and quality assurance processes. Malaysian students, they note, often value the branding of UK degrees more than their local academic relevance, while institutional managers focus on managing practical challenges such as scheduling, cost-sharing, and quality standards. These findings reflect not just operational misalignment but deeper divergences in goals and understandings of what constitutes a successful partnership.

The literature also shows that even minor cultural nuances can produce sharply contrasting perceptions (Yeo and Yoo, 2019). Such differences affect communication, decision-making, and classroom dynamics. To provide a more holistic account of these dynamics, this study integrated perspectives from students, academic and administrative staff, institutional managers, regulators, and parents. It then developed the Triple-A TNE Partnership framework, which conceptualizes agility, adaptability, and alignment as key institutional capabilities for engaging with these intercultural complexities in effective, sustainable ways.

2.4 Theoretical frameworks in TNE

As TNE continues to expand and evolve, the need for strong theoretical foundations to explain how cross-border educational partnerships are formed, governed, and sustained has become increasingly apparent. Scholars have approached TNE with a range of perspectives—including institutional strategy, risk management, partnership dynamics, student experience, intercultural engagement, and national positioning. This section synthesizes key contributions from the literature and lays the groundwork for the Triple-A Framework introduced in this study.

2.4.1 Risk, legitimacy, and institutional strategy

Foundational work in TNE often focuses on institutional risk and strategic positioning. Healey (2015) proposed a “4F” typology of TNE models: distance learning, IBCs, franchising, and validation—each presenting varying degrees of reputational, operational, and financial risk. Wilkins and Huisman (2012) apply institutional theory to explain how “institutional distance”—differences in regulation, norms, and culture—can impact perceptions of legitimacy in cross-border partnerships. Wilkins (2016) extends this view by using a strategy tripod model, integrating institutional, industry, and resource-based considerations to inform internationalization decisions.

However, critics urge caution. Rumbley et al. (2012) argue that institutions often underestimate the challenges of operational complexity and market unpredictability. Altbach (2010) notes that many IBCs lack the full academic infrastructure of their parent campuses and questions whether they can truly replicate the home university experience. Tsiligiris and Hill (2021) advocate a “prospective quality” approach, suggesting that student characteristics and contextual factors should be evaluated early in program development—with proactive design prioritized over reactive assurance.

2.4.2 Partnership dynamics and intercultural governance

Scholars increasingly emphasize the importance of relationships and cultural responsiveness in TNE. Caruana and Montgomery (2015) discuss how shifting roles, institutional identities, and power dynamics shape the evolution of partnerships. Montgomery (2014) introduces the notion of “transnational positionality,” where academic actors constantly navigate multiple systems and expectations. These perspectives appreciate trust, mutual understanding, and dialogue.

Shams (2016) advocates for a dual strategy of standardization and adaptation (StandAdapt) that enables institutions to maintain academic consistency while respecting local norms. He also promotes cultural management strategies that engage with local beliefs, assumptions, and practices. Ziguras (2008) critiques the homogenizing tendencies of global education, showing how the drive for uniformity can erode culturally embedded teaching traditions. Similar concerns are raised by Eldridge and Cranston (2009), McBurnie and Ziguras (2006), and Wallace and Dunn (2013), all of whom argue for more inclusive and context-sensitive forms of governance in TNE.

2.4.3 Service quality and the student experience

A growing body of research addresses how students experience and evaluate TNE provision. Zheng and Ouyang (2023) apply the SERVQUAL model alongside transformative learning theory to explore how students assess academic support and institutional responsiveness across borders. Their findings suggest that perceptions of quality extend beyond the curriculum to include the effectiveness of support systems that facilitate academic and intercultural transitions. Hill et al. (2014) add that in some contexts, such as Malaysia, students may prioritize the symbolic value of foreign credentials over localized academic experiences and thus reinforce brand perceptions.

Nevertheless, gaps in governance remain. Carter (2024) points out that the student voice is often more rhetorical than real. Despite formal mechanisms for representation, students in TNE contexts frequently feel sidelined from meaningful participation in decision-making. This raises concerns about symbolic inclusion and prompts institutions to reconsider how they engage students as partners in cross-border provision.

2.4.4 Critical perspectives on communication and power

Critical approaches draw attention to how power and communication shape TNE relationships. Djerasimovic (2014) uses discourse theory and Bourdieu’s notion of symbolic capital to demonstrate how implicit hierarchies embedded in institutional structures often marginalize local perspectives. Branch (2018) compiles critiques of commercialization, inadequate oversight, and reputational risk in deregulated TNE environments.

IBCs have come under particular scrutiny. Altbach (2010) likens many to “spartan office complexes” lacking the vibrancy and resources of home campuses. Naidoo (2010) contends that market-driven TNE can dilute academic integrity. The closure of UNSW’s Singapore campus in 2007, reported in Cohen (2007), exemplifies the challenges of misaligned projections and expectations. Although the university did not officially disclose losses, estimates placed them in the millions of Australian dollars. The case underscores the importance of local alignment, realistic planning, and sustainable governance.

2.4.5 Country branding and national educational identity

Wilkins et al. (2025) offer a framework for understanding how national educational brand authenticity influences institutional reputation in TNE. Their study finds that consistency in curriculum, staffing, and messaging fosters trust among students and reinforces a university’s credibility. National branding plays a strategic role in shaping how TNE provision is received and sustained in host markets.

2.4.6 Summary and rationale for the Triple-A framework

Together, these frameworks allow insight into the strategic, relational, and intercultural dimensions of TNE. However, they often focus on individual elements—such as risk, legitimacy, or governance—without integrating them into a coherent model of institutional practice. Several issues remain unresolved:

• the dominance of IBC-focused research (Escriva-Beltran et al., 2019), with less attention paid to joint/dual programs, franchises, and hybrid models;

• a lack of integration between strategic and intercultural theories; and

• limited exploration of institutional capabilities that connect governance, responsiveness, and sustainability.

To address these issues, this study developed the Triple-A TNE Partnership Framework, inductively derived from empirical data—including interviews, surveys, and regulatory documents—and identifies three interconnected capabilities:

• agility, or the ability to respond quickly and effectively to change without sacrificing quality;

• adaptability, or the capacity to recalibrate academic and operational practices in response to local cultural and regulatory environments; and

• alignment, or the coordination of institutional goals, governance structures, and communication mechanisms by partners.

Conceptually inspired by Lee’s (2004) Triple-A framework in global supply chain management, these dimensions emerged from real-world data rather than being imposed in advance. They form a bridge between intercultural theory, strategic management, and organizational governance and are explored in the Findings section.

3 Methodology

This study was part of a larger project examining successes, challenges, and opportunities in TNE. To build a rich and contextually grounded understanding of intercultural challenges in TNE, a triangulated data collection strategy was employed. Three sources of data were exploited: (1) 245 survey responses from TNE stakeholders, (2) 108 publicly available regulator review and audit reports, and (3) 12 in-depth interviews. This multi-strand design allowed for a comparative and inductive analysis, with each dataset offering a distinct perspective on how intercultural dynamics are experienced and managed in TNE settings. University names are anonymized in the findings, except where they appear in publicly available regulator’s TNE review and audit reports.

3.1 Data collection

3.1.1 Surveys

Surveys formed the first strand of data collection and were designed to capture perspectives from three stakeholder groups: students, institutional stakeholders, and parents. Each group received a tailored version of the survey to ensure clarity, contextual relevance, and appropriateness of tone. The instruments were piloted with a small sample and refined based on feedback to enhance accessibility and consistency.

Administered via Qualtrics, the surveys were disseminated through a combination of social media, email, and offline outreach using the author’s personal and professional networks. A snowball sampling strategy was adopted to maximize reach across a diverse range of TNE contexts. The survey reached over 1,000 potential participants globally and yielded 245 valid responses: 123 from students, 67 from institutional stakeholders, and 55 from parents. Respondents were based in 23 countries/regions, including Australia, mainland China, Cyprus, France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, India, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Switzerland, Turkey, the UAE, the UK, the USA, and Vietnam. The overall response rate was approximately 25%, which aligns with expected norms for open, voluntary surveys in international higher education contexts. Full versions of the survey instruments are included in Appendices A–C.

Institutional stakeholders were grouped into five categories: academic staff, administrators, managers, regulators, and other. While Tran et al. (2023) offer a more expansive typology of TNE stakeholders—including host country governments, academic and non-academic staff from both home and host institutions, expatriates, students, quality assurance agencies, and employers—this broader framework was pragmatically adapted for the purposes of this study.

Academic staff included both expatriate and locally employed personnel from home and host institutions and encompassed teaching and academic support roles. Administrators referred to operational staff engaged in program coordination and delivery. Managers included individuals in strategic or leadership roles responsible for TNE provision—ranging from joint program managers to senior campus leaders such as deans, heads of school, and campus directors. Job titles varied in institutions but included vice-chancellor, provost, rector, or other chief executive roles, depending on the institutional structure and context. Regulators comprised individuals from national quality assurance agencies or ministries of education and offered policy-level insights and oversight perspectives. The “other” category captured stakeholders whose roles did not fit neatly into the primary classifications but who were nonetheless involved in or closely connected to TNE operations, such as consultants and affiliated partners.

Among the 67 institutional stakeholder respondents, participants were drawn from 12 host countries and regions (mainland China, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Singapore, the UAE, Qatar, Japan, India, Cyprus, Greece, Sri Lanka, and Germany) and six home countries (the UK, Australia, the USA, France, Canada, and China). The sample included 17 respondents in partnership-facing roles (e.g., joint program or joint institute directors), 12 in senior leadership positions (e.g., campus heads, rectors, provosts), and 33 academic staff: 14 based at host institutions, 11 at home institutions, and 8 expatriates who had relocated from a third country to work in a TNE setting. In addition, five respondents were regulators from national agencies or education ministries.

While the survey addressed a range of topics, this study was focused on two questions related to intercultural engagement:

1. What are the biggest intercultural challenges you have encountered while studying in this TNE program/ in your role within the TNE program(s) /supporting your child’s TNE education? (open-ended)

2. Have you received any guidance or support to navigate intercultural challenges? (multiple choice)

• Yes, and it has been helpful

• Yes, but it could be improved

• No, I have not received support

• Not applicable

Open-ended responses were analyzed thematically using NVivo, following an inductive, bottom-up coding approach to identify recurring patterns. Descriptive analysis of the multiple-choice responses provided further insight into perceptions of the availability and effectiveness of institutional support.

3.1.2 Regulator review and audit reports

The second strand of data drew on 108 publicly available TNE review and audit reports published by the UK QAA and covering 85 institutional partnerships in nine countries/regions. While these reports were primarily designed for quality assurance purposes, they offered rich insight into the intercultural dynamics and operational complexities that arise in the delivery of TNE. A full list of reports is included in Appendix D.

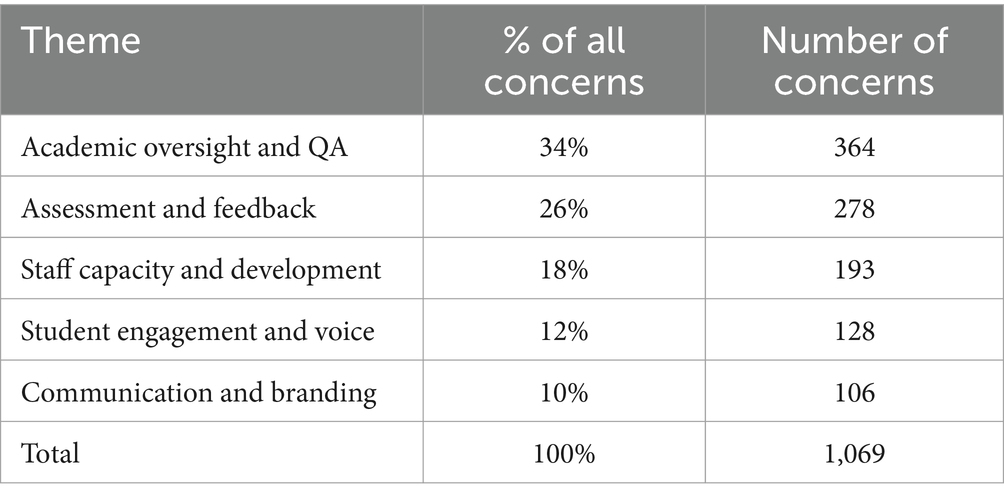

After systematic coding adapted from the approach of Stafford and Taylor (2016), 1,069 concerns were identified in the reports. The analysis was guided by textual markers commonly associated with evaluative or critical commentary, such as however, recommend, and recommendation. These concerns were categorized into five overarching thematic areas (Table 3).

The categories in the table reflect issues that frequently emerge when implementing UK-based academic standards in culturally and structurally diverse settings.

Examples from the reports illustrate recurring challenges—such as misaligned policies, delays in staff approvals, insufficient contextualization of learning materials, and unclear assessment feedback—that often stem from intercultural disconnects. One such instance read:

Many external examiners have commented on the good quality of feedback to students. However, students who spoke to the review team described their feedback as at best variable. Staff are aware of the fact that feedback to students is at times inadequate, referring to cultural differences in expectations on feedback… Lancaster is recommended to consider how to meet the expectations of its students at Sunway regarding feedback on their assessments. (QAA Review: Lancaster University and Sunway University, Malaysia, 2019. Emphasis added).

The findings offered a regulatory lens through which to examine the structural and cultural frictions in TNE. When combined with the more grounded, practice-based perspectives gathered from surveys and interviews, the audit reports added depth to and allowed triangulation for the overall analysis.

3.1.3 Interviews

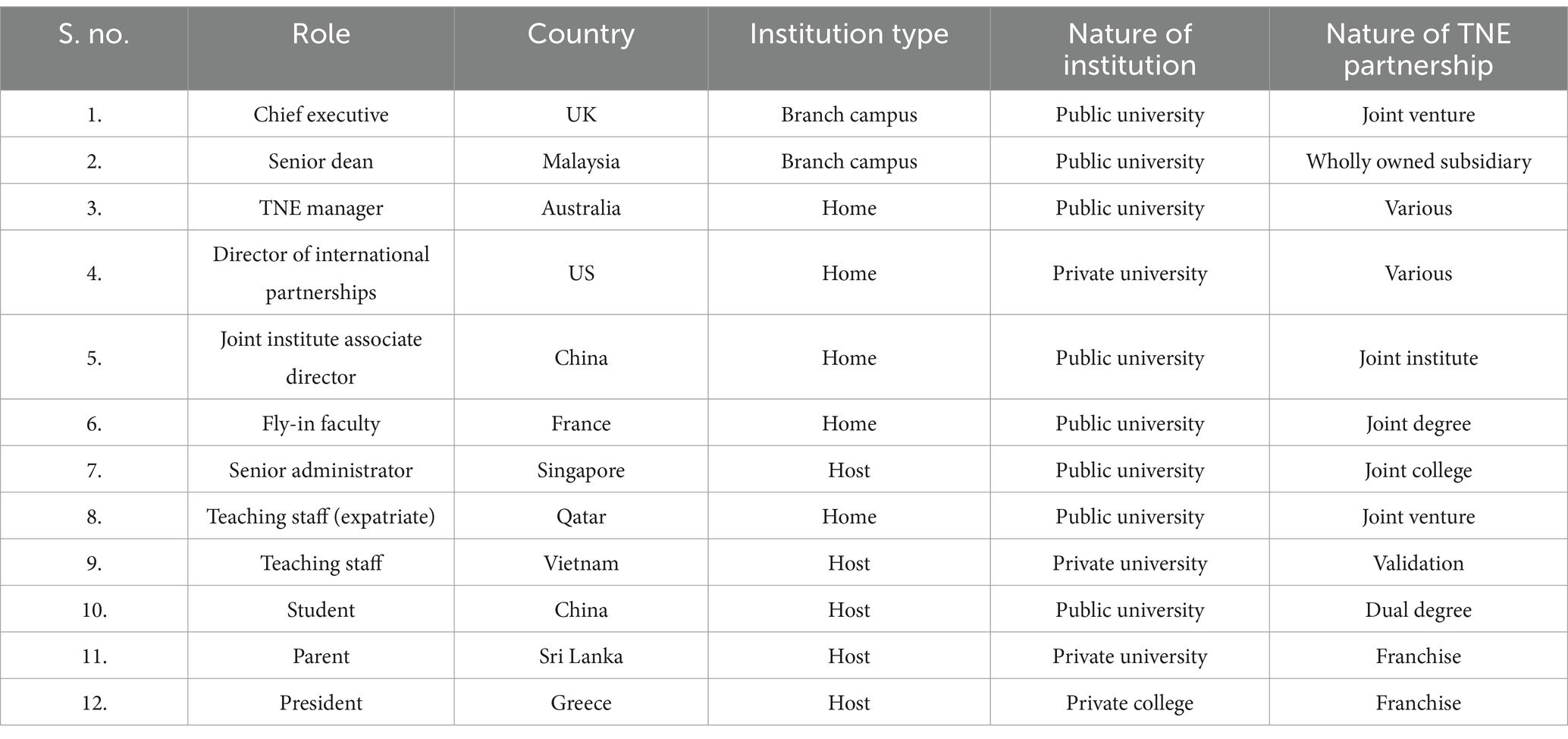

The final strand of data collection involved 12 unstructured interviews with TNE stakeholders, including students, staff, and parents. Interviews ranged from 20 to 50 min in duration and were conducted either in person or online, depending on participant availability (Table 4).

Interview data revealed important contextual nuances, particularly around institutional culture, learning environments, and the day-to-day experience of navigating cultural differences. These perspectives both triangulated and deepened the themes emerging from the surveys and QAA reports. Interviews were thematically analyzed using an inductive coding process in NVivo, with attention paid to both convergences and divergences among stakeholder groups.

3.2 Data integration and analytical approach

The three data sources were analyzed thematically using an inductive, comparative approach with the assistance of NVivo software. Initial coding was conducted independently for each dataset and allowed themes to emerge directly from the data without imposing a preexisting framework. As the analysis progressed, codes were compared across datasets to identify shared concepts, recurring patterns, and points of divergence.

This process led to three core dimensions that consistently appeared in the three datasets: institutional and interpersonal agility, adaptability to local and cultural contexts, and alignment between partner expectations, systems, and practices. While these dimensions were derived inductively from the data, their resonance with Lee’s (2004) Triple-A supply chain framework offered a valuable conceptual bridge. In this study, the framework has been adapted to the TNE context; agility, adaptability, and alignment are reinterpreted as institutional mechanisms for navigating and responding to intercultural challenges.

To strengthen the credibility of the analysis, a second coder independently reviewed a sample of each dataset using the emerging framework. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved collaboratively, and refinements were made to the coding definitions and thematic boundaries. This iterative process helped ensure conceptual clarity and analytical rigor.

The findings that follow are structured around the adapted Triple-A framework. They draw together evidence from the surveys, audit reports, and interviews to explore how TNE institutions manage the complexities of intercultural engagement in diverse partnership settings.

4 Findings: intercultural challenges and the Triple-A framework

This section presents the empirical findings and introduces the Triple-A—alignment, adaptability, and agility—TNE Partnership Framework as a grounded, data-driven model for understanding how institutions navigate intercultural complexity in TNE. The framework emerged inductively from a thematic analysis of 123 open-ended student surveys, 67 surveys with academic and professional staff, senior managers, and regulators, 55 parent surveys, 108 regulator TNE review reports, and 12 stakeholder interviews. Rather than being imposed from preexisting theory, the framework crystallized from recurring patterns observed in the reported experiences of diverse TNE participants.

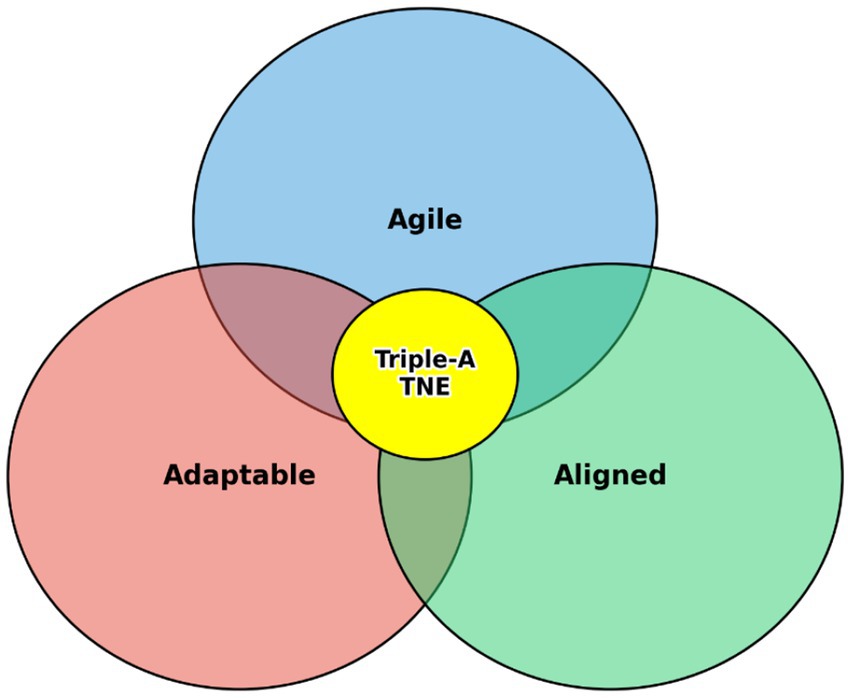

Alignment, adaptability, and agility are presented not as linear stages but as interconnected and mutually reinforcing capabilities. Institutions draw on them simultaneously and dynamically in response to intercultural complexity. Figure 1 illustrates how these capabilities can intersect to support resilient, equitable, and context-sensitive TNE partnerships.

Figure 1. The Triple-A TNE Partnership Framework: alignment, adaptability, and agility as interconnected capabilities for intercultural effectiveness in TNE (each dimension strengthens and supports the others in practice. These are not steps in a sequence but overlapping lenses through which institutions make sense of and respond to intercultural dynamics).

Each data point was coded under one primary theme (alignment, adaptability, or agility) to avoid duplication. In the thematic distribution, 42% of coded examples centered on alignment, followed by 35% on adaptability and 23% on agility. This pattern offers insight into the scale and nature of intercultural tensions: Agility was often required in urgent or disruptive contexts, adaptability in ongoing curricular or regulatory recalibrations, and alignment in strategic negotiations, governance structures, and role definitions.

A consistently cross-cutting theme was the lack of formal institutional support to help stakeholders navigate intercultural challenges. Among surveyed participants, 41% of students, 70% of host institution staff, 71% of home institution staff in fly-in or seconded roles, 74% of expatriate staff (who relocated from one country to deliver a program in a second country for a degree awarded by a third), and 38% of parents reported receiving no intercultural support. Where support did exist, it was typically described as minimal, ad hoc, or symbolic—often limited to a single induction session or left to individual initiative. This absence of systematic provision contributed to a sense of institutional neglect and reinforced a perception that intercultural challenges were personal burdens rather than shared organizational responsibilities.

The following subsections analyze each of the three capabilities in turn, exploring how institutions enacted—or failed to enact—these strategies in different settings. Each subsection presents thematic subcategories, illustrative quotes, and real-world cases to provide analytical depth and insight into how intercultural challenges materialize in practice and what institutional behaviors are required to address them effectively.

4.1 Alignment: harmonizing goals, roles, and incentives

Alignment was the most frequently cited source of tension and the most consequential when neglected. This tension was not only operational; it was often strategic and cultural. It originated from mismatches in institutional priorities, power distributions, and accountability models.

4.1.1 Conflicting and evolving institutional priorities

A central intercultural challenge in TNE is balancing financial imperatives with academic missions. As institutions from different national and organizational contexts come together, their strategic goals may diverge—particularly if local market conditions or political pressures shift over time.

Excerpt 1: We have to be financially profitable, not just break even… but our university partner prioritizes other things. (president, Greek private partner, survey response)

4.1.1.1 Example 1: a leading Australian university in Singapore

In 2004, a leading Australian university was invited by Singapore’s Economic Development Board to establish the nation’s first comprehensive international university. The campus opened in March 2007 with the shared ambition of positioning Singapore as a global education hub. However, by May 2007—just 2 months later—the university announced its closure, with operations ceasing by the end of June. The key issue was that financial expectations were misaligned. The university’s projections overestimated local demand and underestimated the competitiveness of Singapore’s higher education market. Despite the academic potential, the venture proved financially unsustainable. According to a senior TNE manager at the home university (survey response and interview), the failure stemmed from a lack of contextual market analysis and an inability to adapt business strategy to local realities. The case underscores the importance of aligning financial models with host country needs to support long-term viability.

4.1.1.2 Example 2: a world class U.S. university’s liberal arts collaboration

Another case of shifting priorities unfolded in a partnership between a prestigious U.S. university and a top Singaporean institution. The joint liberal arts college, launched in 2011, was celebrated as a pioneering initiative—introducing U.S.-style education to Southeast Asia and receiving substantial government backing. Initially successful, the college attracted high-caliber students and academic acclaim. However, in 2021, the host institution announced its intention to dissolve the partnership, with operations set to end in 2025. The U.S. university expressed disappointment at the unexpected decision. The rationale provided by the host institution pointed to evolving national priorities: a desire to broaden access, reduce exclusivity, and integrate liberal arts elements into a larger institutional framework. The end of government seed funding and the financial challenges of running a small, elite college also contributed.

Excerpt 2: We were quite surprised when the decision to close the college was announced. The partnership had been successful, but it’s clear the [host university]‘s priorities shifted toward making education more accessible and aligning with national goals. (senior administrator at the Singapore university).

These cases reflect a recurring theme: misalignment not just between sending and host institutions but between evolving academic and commercial priorities on both sides. While partners often recognize the need for financial sustainability, differences arise in how they weigh academic integrity, market positioning, and commercial viability—especially under shifting policy landscapes, funding models, or leadership. Tensions can surface when enrolment or revenue targets are missed and raise questions about accountability and risk-sharing. In other instances, institutional goals evolve over time, but without structured opportunities to revisit and realign shared objectives, partnerships drift apart. Where formal mechanisms for dialogue and adjustment are lacking, trust and joint commitment prove difficult to sustain. By contrast, partnerships that embed flexible governance and engage in regular goal realignment are better positioned to adapt to change and maintain resilience.

4.1.2 Unequal roles and marginalized voices: power imbalances and governance challenges

Intercultural challenges in TNE partnerships frequently stem from unclear roles and unequal distributions of authority. When roles are misaligned or poorly defined, power imbalances can take root—excluding key stakeholders and undermining collaboration.

Several faculty members described the mounting burden of working across dual regulatory systems, conflicting academic expectations, and parallel institutional processes. These demands often resulted in significantly increased workloads, especially for those operating at the intersection of two or more governance structures. Yet this additional labor was not always formally acknowledged in workload models, job descriptions, or institutional planning. As one interviewee put it, “You’re accountable to two systems, but no one adjusts your workload for that.” This disconnect reflects a deeper governance gap—where institutional frameworks fail to recognize the intercultural and structural demands placed on frontline staff. Without clearer role definitions, shared responsibility, and sustained support, such arrangements risk undermining both faculty well-being and the long-term sustainability of TNE delivery.

4.1.2.1 Faculty perceptions and power dynamics

A recurring issue among the cases was the perception that expatriate faculty, often affiliated with the home institution, had more influence than local faculty. This dynamic reinforced cultural hierarchies and eroded trust, diminishing the spirit of partnership that effective TNE arrangements require (survey responses: TNE student 23, 45, 73, 121; TNE stakeholder 4, 7, 8, 34, 59).

Excerpt 3: As a local faculty member, I often felt left out of major decisions. It seemed like the expatriate faculty always had more influence, just because they were from the home campus. (faculty member at an overseas branch campus, survey response).

This imbalance was not lost on students. In some settings, they viewed expatriate staff as the “real” academics, even when local staff had more teaching experience. These perceptions, rooted in institutional hierarchies and symbolic authority, undermined team cohesion and mutual respect.

Excerpt 4: They never asked for our input—it felt like they did not trust us. (host faculty, Vietnam, survey response).

Excerpt 5: We’re delivering most of the programme, but decisions are made in another country. We’re implementers, not partners. (academic coordinator, Dubai, survey response).

These accounts reflect a broader pattern of symbolic inclusion without substantive influence. Host faculty often led day-to-day teaching and administration but were excluded from curriculum design, assessment moderation, and strategic planning. Meanwhile, home institution staff—particularly those on secondment or fly-in contracts—were more visible in governance structures and external communications.

4.1.2.2 Student representation

Limited student voice was another persistent concern. Despite references to student engagement in policy documents and quality assurance handbooks, meaningful participation in governance was often lacking. This disconnect between institutional rhetoric and practice created frustration and reinforced a sense of exclusion.

Excerpt 6: There’s a lot of talk about student voice in the handbook, but in reality, our input often feels like an afterthought. Decisions are made at the top without consulting us or understanding what we go through on the ground. (student at a Cyprus branch campus of a UK university, survey response).

In the regulator review report dataset, the QAA repeatedly emphasized the importance of genuine student participation in decision-making as a marker of good practice in TNE governance. However, students in this study often described their involvement as tokenistic, with little evidence that their feedback led to meaningful change.

Institutions that actively addressed these power asymmetries—for example, by establishing shared governance boards, co-chaired curriculum committees, or reciprocal staff development schemes—reported improved morale, stronger collaboration, and greater trust among teams (TNE stakeholder survey responses 1, 52, 56, 61). These measures helped shift TNE partnerships from hierarchical arrangements toward more inclusive and dialogic models of engagement.

4.1.3 Disconnect between local and central operations

Excerpt 7: Out of sight, out of mind… the branch campus just becomes a figure feeding into the bottom line. (chief executive, UK university branch campus, interview).

A recurring challenge reported by participants was the disconnect between central university leadership and local delivery teams, particularly in branch campuses or partner-hosted programs. This disconnect often manifested in duplicated processes, inefficient communication, and a growing sense of marginalization among those responsible for on-the-ground delivery. Local teams described having to navigate parallel systems—for HR, IT, assessment, and student services—without integrated planning, support, or autonomy. Academic policies were often developed centrally and misapplied to local realities.

These operational breakdowns reflected weak coordination but also a deeper strategic misalignment between what institutions valued centrally and what was needed locally. Branch campuses, while institutionally governed by the sending university, were often treated as revenue-generating extensions rather than academic partners—which undermined morale, initiative, and innovation.

By contrast, institutions that invested in regional hubs, appointed TNE liaison roles, or embedded joint governance structures were better positioned to support day-to-day coordination and decision-making across sites. However, even strong operational systems were insufficient without broader alignment with national and institutional strategies on both sides.

Successful TNE programs aligned with host country priorities—such as regional development and workforce planning—but also leveraged sending country incentives to enhance their sustainability.

4.1.3.1 Example 1: China’s emerging tier-one cities

China’s Ministry of Education has encouraged foreign universities to expand into cities like Xi’an and Chengdu, supporting regional development through targeted talent pipelines. TNE providers who aligned programs with these priorities—particularly in sectors such as renewable energy or smart infrastructure—gained local legitimacy and policy support while ensuring enrolment sustainability.

4.1.3.2 Example 2: a prominent U.S. university in Japan

A leading U.S. university campus in Japan serves a highly diverse student body: one-third local Japanese students, one-third internationally mobile students, and one-third U.S. military veterans funded under the Yellow Ribbon Program. This model highlights how TNE institutions can strategically align with home-country policies—in this case, U.S. government funding for veterans—while also responding to host-country educational needs. The result is a resilient and contextually embedded program, rooted in bilateral relevance.

These cases show that alignment with incentives on both ends of the TNE relationship—nationally and institutionally—is key to reducing operational friction and building sustainable, high-impact partnerships.

4.2 Adaptability: integrating global standards with local contexts

Adaptability refers to the capacity of TNE institutions to recalibrate curricula, pedagogy, support systems, and regulatory processes to suit the host environment while upholding the academic standards and values of the home institution. This capability emerged most clearly in relation to three persistent themes: language barriers, contrasting learning traditions, and regulatory complexity. In each case, successful adaptation went beyond surface-level localization and required sustained institutional investment and contextual responsiveness.

4.2.1 Language barriers

Excerpt 8: Even when I understood the topic, I was too scared to say something wrong in front of everyone. (first-year student, China, interview).

Language barriers were among the most frequently cited challenges across all stakeholder groups. For students, these barriers affected not only comprehension of academic content but also confidence in expressing ideas during seminars, presentations, and assessments. Even when students met the linguistic requirements for entry, many reported anxiety around speaking in class or engaging in discussion-based activities. This was particularly acute in contexts where the medium of instruction was English, but the surrounding environment remained monolingual.

Survey and interview data suggested that this lack of confidence often led to classroom silence, reduced participation, or a reliance on native language when working in small groups. In response, some institutions introduced bilingual teaching assistants, glossary-supported or dual-language lectures, and low-stakes, anonymized engagement tools such as live polls and online Q&A formats. These measures helped reduce students’ affective barriers and enabled more inclusive classroom engagement, particularly in the early stages of study.

Language-related challenges also affected staff and quality assurance processes, especially where TNE programs were delivered in non-English languages. Several UK universities delivering degrees in Spanish or Greek reported difficulties in sourcing suitably qualified external examiners who were both bilingual and familiar with UK academic standards. This created bottlenecks in external moderation and risked undermining assessment credibility.

Excerpt 9: The [host institution] deliver[s] our degree in Spanish, and it’s extremely difficult to find an external examiner who is both bilingual and has the right subject expertise and familiarity with UK standards. (program director, UK university, survey response).

Institutions that planned proactively for these challenges, for example by maintaining bilingual documentation or appointing co-examiners, were better equipped to balance the demands of local accessibility with the expectations of transnational academic quality.

4.2.2 Contrasting learning traditions

We were told to learn independently, but nobody showed us how. (business undergraduate, Malaysia, survey response).

TNE students from educational systems that emphasize rote learning and strong teacher authority often struggled with pedagogical models that required independent study, critical inquiry, and self-reflection. Silence in the classroom was sometimes misinterpreted by home-campus faculty as disengagement, when it more often reflected unfamiliarity with these new learning norms or uncertainty about what was expected.

This misalignment was also noted in QAA TNE reviews, which called for clearer evidence that institutions were actively supporting students in their transition to independent learning. The most responsive TNE institutions addressed this by developing scaffolded approaches to academic autonomy, co-teaching models that paired local and home staff, and academic skills modules designed with the host context in mind. These interventions helped students navigate the cultural shift in learning style and contributed to greater academic engagement and success.

4.2.3 Navigating regulatory and accreditation diversity

Regulatory complexity presented another significant area where adaptability was tested. Institutions delivering dual degrees, joint programs, or franchised offerings were required to meet the standards of both the home and host education systems. These requirements were not always aligned and, in many cases, remained fluid due to evolving national policies or unclear guidelines.

4.2.3.1 Example 1: China – the one-third rule

In Chinese-foreign joint education programs, the Ministry of Education enforces the “Four One-Thirds Rule” to ensure substantial involvement from foreign educational partners. This rule mandates:

1. At least one-third of the total courses (modules in the UK context) should be introduced from the foreign partner institution.

2. At least one-third of the core (specialization) courses should be sourced from the foreign partner institution.

3. At least one-third of the core courses should be taught by faculty from the foreign partner institution.

4. At least one-third of the total teaching hours should be delivered by faculty from the foreign partner institution.

These regulations are designed to ensure that foreign education partners commit a significant portion of teaching and learning resources to the joint venture, thereby enhancing the quality and internationalization of the education offered. However, implementing these requirements necessitates careful planning, intercultural collaboration, and program design adjustments. Institutions must effectively manage faculty deployment and resource allocation to comply with these guidelines while maintaining their global standards (TNE stakeholder survey response 9, 10, 19, 23, 51).

4.2.3.2 Example 2: India – evolving regulations

India’s approach to TNE has seen significant changes in recent years. Until late 2023, foreign universities were not allowed to establish branch campuses in the country. However, as of November 2023, this restriction has been lifted. Eligible institutions can now set up campuses and offer a wide range of academic programs, provided they receive prior approval from the University Grants Commission (UGC), India. In addition to this, the UGC introduced rules in 2022 for non-branch campus TNE collaborations, marking the first formal framework for such partnerships (UGC, 2022). These regulatory changes are part of broader reforms under India’s National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 to internationalize its higher education.

Excerpt 10: The biggest challenge is navigating India’s complex regulatory environment… things are still a work in progress. (TNE manager, Australian university, interview)

4.2.3.3 Example 3: Qatar – dual accreditation for health care programs

In Qatar, a U.S.-based university adapted its healthcare programs to meet both U.S. accreditation standards and Qatari professional licensure requirements. According to the surveyed teaching staff, this was described as the “biggest cultural challenge ever.” Despite the complexities, this adaptation ensures that graduates are qualified for employment in both contexts, highlighting the adaptability required to adapt to multiple regulatory systems successfully.

4.3 Agility: navigating disruption and intercultural friction

In TNE, agility refers to the ability of institutions, staff, and students to respond quickly and flexibly to unexpected disruptions and intercultural complexities. Unlike alignment and adaptability—which often involve strategic planning and gradual adjustment—agility is about responding in real time to fluid, high-pressure situations. These ranged from global crises and communication breakdowns to classroom sensitivities. Across the dataset, agility was observed in how participants handled mismatched communication norms, navigated cultural tensions, and sustained operations during crises.

4.3.1 Mismatched communication preferences

We have to check both WeChat and email, and each university expects us to follow their preferred platform. (student, China–UK joint institute, survey response).

Mismatched communication preferences were a recurring intercultural challenge, reflecting deeper cultural differences in interaction style and expectations. In China, for instance, students and staff widely use WeChat as the default professional communication tool, while UK institutions continue to rely on institutional email. Students at joint institutes described confusion and frustration caused by the need to manage multiple platforms across different systems.

My classmates and I find it very hard to keep up with the latest messages. My [Chinese host university] teachers use WeChat, but my [UK sending university] teachers use emails. We also have two university email addresses—one for each side—so we have to keep jumping between these different systems of communication. This is a challenge! (TNE student, China–UK joint institute, survey response).

This sentiment was echoed by staff:

Many of my students only use their [Malaysian college] email address and rarely check their [Australian university] email. My [Australian university] colleagues struggle to get hold of students via email because they do not use the Australian email. I cannot blame the students; after all, they are studying an Australian degree at a Malaysian college. (course leader, Australian franchise program in Malaysia, survey response).

In the absence of institutional strategies to bridge these divides, students and staff were often left to find workarounds themselves. However, more agile institutions developed dual-channel communication policies, embedded local platforms into formal workflows, and appointed liaison officers to help consolidate information flow. These strategies reduced confusion and allowed more seamless engagement across national systems.

4.3.2 Intercultural responsiveness in the classroom

I paused the recording during an LGBTQ+ discussion. It wasn’t ideal, but necessary in that context. (lecturer, Middle East, survey response).

Lecturers operating in culturally sensitive contexts often needed to adjust their teaching in real time to navigate potential risks. In some cases, this involved changing how topics were framed, skipping certain examples, or modifying recorded content to avoid political or cultural repercussions. These micro-decisions are indicative of the agility required of staff to reconcile global academic norms with local values.

However, this type of responsiveness was frequently improvised. Staff reported being given little or no formal guidance and often relying on instinct, informal peer advice, or trial-and-error. One manager noted: “Staff are often given one short induction if they are lucky and then expected to hit the ground running with little or no support.”

Institutions that provided scenario-based briefings, intercultural communication training, and culturally adaptable teaching resources saw more consistent outcomes. These support structures enabled staff to make informed, contextually appropriate decisions while maintaining educational integrity.

4.3.3 Crisis response and digital pivoting

We converted a hotel into a teaching studio. It was the only option. (dean, Sri Lankan partner institution, survey response).

The COVID-19 pandemic was a profound test of institutional agility. It disrupted travel, teaching schedules, and classroom delivery across nearly all TNE partnerships. Students, staff, and administrators were forced to adopt new tools and navigate unfamiliar systems under urgent timelines.

Our university worked flexibly to transition teaching and assessment online, ensuring we could finish our year on time. (TNE student, survey response).

Some institutions pivoted quickly—reallocating resources, decentralizing decision-making, and empowering local leaders to act without waiting for centralized approvals. Others repurposed physical spaces, created makeshift broadcast classrooms, or expanded staff responsibilities to maintain academic continuity. In several cases, local campuses transitioned online weeks ahead of the home university’s formal guidance, reflecting their capacity to act decisively in context.

These experiences not only helped mitigate disruption but also reinforced the importance of trust, decentralization, and responsiveness in TNE governance. While the pandemic exposed weaknesses in institutional preparedness, it also demonstrated the value of embedding agility into systems—from communication to contingency planning.

4.4 Summary of findings

This study introduced the Triple-A framework—alignment, adaptability, and agility—as an empirically grounded model for understanding how institutions navigate the intercultural realities of TNE. Each dimension reflects a distinct capability, yet they are deeply interconnected and often deployed simultaneously in response to the complex dynamics of cross-border delivery.

Alignment emerged as the most frequently cited source of tension, particularly where institutional priorities, governance structures, and stakeholder roles were misaligned across home and host contexts. Strategic divergence over time—whether in enrolment targets, financial expectations, or academic autonomy—often led to operational breakdowns, marginalized voices, and weakened collaboration. Institutions that embedded shared governance mechanisms and aligned their programs with both host-country development goals and home-country incentives were better equipped to build resilient partnerships.

Adaptability was essential in day-to-day teaching and operations, especially in response to language barriers, unfamiliar learning traditions, and regulatory divergence. While many students struggled with English-medium instruction or transitioning to independent learning models, faculty and staff also faced considerable pressures. In particular, working across dual regulatory systems and institutional processes often resulted in increased workloads—challenges that were not always formally recognized in workload models, job descriptions, or performance reviews. This lack of acknowledgment reflected broader governance gaps, where institutional expectations outpaced structural support. Institutions that invested in bilingual support, scaffolded learning models, and regulatory flexibility demonstrated stronger intercultural responsiveness and educational quality.

Agility, though referenced less frequently, was critical in moments of disruption and cultural sensitivity. This included navigating mismatched communication platforms, adapting classroom delivery in politically or socially sensitive environments, and pivoting rapidly during global crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Where local leadership was empowered and institutional systems allowed for real-time decision-making, TNE programs were more successful in maintaining continuity and trust.

In all three capabilities, a consistent theme was the lack of formal, sustained institutional support. Many intercultural challenges were left to individuals to manage, with students, staff, and managers relying on informal coping strategies in the absence of clear guidance or structures. Where institutions viewed these challenges as shared organizational responsibilities—and designed systems to support them—outcomes improved markedly.

The Triple-A framework therefore offers more than a diagnostic tool: It provides a strategic foundation for designing inclusive, contextually grounded, and future-facing TNE partnerships. By recognizing alignment, adaptability, and agility as core capabilities—rather than reactive responses—institutions can move beyond compliance and toward meaningful intercultural engagement and partnership resilience.

5 Discussion

5.1 Interculturality as institutional practice

This empirically grounded framework was not imposed deductively but emerged inductively from stakeholder narratives across three data strands—surveys, interviews, and regulatory reports. As such, it reflects lived experience rather than abstract theorizing, and its practical relevance is grounded in the realities of TNE.

This study situates interculturality as central—not peripheral—to the functioning and sustainability of TNE. The empirical emergence of the Triple-A framework underscores the importance of conceptualizing agility, adaptability, and alignment not as isolated strategies but as interdependent institutional capabilities for navigating complexity. Each capability reflects a strategic orientation grounded in stakeholder experience, policy constraints, and pedagogical practice.

5.1.1 Agility: navigating disruption with responsiveness

Agility addresses the capacity for real-time, context-sensitive responses. Institutions operating across national and cultural borders must contend with disruptions ranging from political instability and public health emergencies to rapidly shifting regulatory expectations. This resonates with Healey’s (2015) emphasis on institutional resilience in risk-prone contexts and with Wilkins and Huisman’s (2012) account of legitimacy challenges in unfamiliar regulatory environments. It also aligns with Dervin’s (2016, 2023) realist interculturality, where institutions engage with cultural complexity through situated, reflexive practices. The study’s findings—such as on staff improvisation in culturally sensitive classroom discussions or rapid digital pivots—demonstrate how agility can sustain trust and institutional continuity.

5.1.2 Adaptability: bridging global standards and local realities

Adaptability emerged as essential for sustainable intercultural engagement. Regulatory plurality, linguistic diversity, and pedagogical mismatch—common features of TNE—require institutions to recalibrate academic and operational practices. Participants highlighted the need for clearer pathways to independent learning, inclusive curricula, and effective support mechanisms. These findings reinforce Shams (2016) StandAdapt model and Ziguras (2008) critique of homogenizing educational delivery. By embracing adaptability, TNE providers can both promote relevance and respect the cultural and educational distinctiveness of their host environments.

5.1.3 Alignment: governance, voice, and equity

Alignment was the most frequently cited capability—and the most structurally complex one. It addresses the need for coherence of governance structures, incentive systems, and strategic priorities. Misaligned goals between home and host institutions, marginalization of local staff, and fragmented communication often result in partnership failure. These findings echo Djerasimovic’s (2014) use of symbolic capital to explain how power imbalances manifest in TNE, and they support Caruana and Montgomery’s (2015) call for more inclusive governance that acknowledges shifting positionalities and stakeholder asymmetries. Alignment requires co-governance models that prioritize mutual accountability and equitable representation.

While Lane et al. (2025) highlight the complex positionality of students in increasingly diverse TNE formats, this study extends that discussion by underscoring the institutional side of the equation and emphasizing the need for joint governance structures that incorporate local and expatriate voices. Such inclusive approaches are particularly important as TNE evolves into more complex and hybrid delivery models. Future research should further examine how governance design influences not just student identity but also partnership sustainability and power dynamics among institutions.

5.2 Supporting the people who deliver TNE

A particularly urgent theme in the data was the lack of intercultural support for staff delivering TNE—including those from the home and host institutions, as well as expatriates relocated from third countries. Participants described being “thrown in at the deep end,” with minimal induction, little guidance on intercultural classroom dynamics, and no systematic support for navigating complex academic and cultural expectations. Specific institutional practices that could support staff agility and adaptability include predeparture intercultural training, ongoing professional development in culturally inclusive pedagogy, team-teaching arrangements, co-developed syllabi, and mentorship schemes for expatriate faculty. An absence of structured support undermines agility and adaptability and directly impacts the quality and continuity of partnership delivery. Governance frameworks matter—but the long-term success of any TNE initiative depends on the people who deliver it.

5.3 Bridging conceptual gaps in the literature

Together, the Triple-A capabilities respond to a longstanding gap in the literature. While models such as the Strategy Tripod (Wilkins, 2016) and Healey’s 4F framework (2015) offer valuable macro-level guidance, they fall short of capturing the intercultural negotiations occurring daily in TNE settings. The Triple-A Framework bridges this gap by integrating operational agility, pedagogical and regulatory adaptability, and governance alignment into a unified model of practice. It shifts the analytical lens from program structures to institutional behaviors—what institutions do, rather than what they are.

The framework also answers recent calls for more practice-oriented and more inclusive models of TNE governance. Montgomery (2014) highlights the complexity of transnational positionality, while Carter (2024) critiques the superficiality of student representation in governance. This study operationalizes those concerns by identifying specific institutional behaviors and design principles that promote more equitable and sustainable TNE ecosystems.

5.4 Practical implications and future research

Practically, the framework can inform the design, evaluation, and regulation of TNE partnerships. Institutions might conduct Triple-A audits to assess their responsiveness and relational practices. Regulators could adapt the framework to develop culturally contextualized benchmarks. Policymakers might use it to support more equitable, resilient, and context-aware cross-border provision.

While it is grounded in rich qualitative data, the framework’s transferability could be enhanced through longitudinal studies and cross-sector application. Future research should investigate how Triple-A capabilities develop over time, vary across TNE models, and influence long-term partnership viability. Comparative studies could also assess how different institutional cultures foster—or inhibit—these capabilities in varied geopolitical and educational contexts.

6 Conclusion

TNE partnerships are shaped by constant negotiation—across borders, institutions, and cultures. This study introduces the Triple-A Framework—agility, adaptability, and alignment—as an empirically grounded conceptual model for navigating the intercultural and operational complexities of TNE. These capabilities are not merely abstract ideals. Rather, they emerged inductively from the experiences of students, staff, managers, and regulators in diverse contexts.

Agility enables timely, culturally attuned responses to disruption. Adaptability ensures that teaching, governance, and support are locally relevant while maintaining global standards. Alignment fosters coherence of goals, roles, and incentives and supports trust, inclusivity, and long-term resilience.

The findings suggest that the sustainability of TNE relies not just on strategy but on the people who deliver it—particularly staff at both home and host institutions. However, support for these actors remains inconsistent. Many are expected to navigate dual systems and intercultural tensions without adequate preparation, guidance, or voice. Addressing this gap is essential. Structured intercultural training, joint curriculum design, team teaching, and co-governance can build institutional capacity from within.

The study also underscores the importance of balancing commercial viability with academic ambition. TNE partnerships may falter when driven solely by market logics or misaligned priorities. The Triple-A Framework provides institutions and regulators with a lens to evaluate and strengthen their strategy and practices—bridging operational effectiveness with cultural sensitivity and ethical responsibility.

Future research should explore how these capabilities develop over time and how investment in staff and stakeholder support shapes partnership outcomes. As TNE continues to expand and diversify, embedding agility, adaptability, and alignment into its governance and daily practice will be essential to building partnerships that are not only scalable, but also equitable and enduring.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Cambridge. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Correction note

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the scientific content of the article.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2025.1568138/full#supplementary-material

References

Altbach, P. G. (2010). Why branch campuses may be unsustainable, International Higher Education. 58, 2–3.

Branch, J. D. (2018). “A review of transnational higher education” in Advances in educational technologies and instructional design. ed. B. Smith (London: IGI Global), 1–20. doi: 10.4018/978-1-5225-4972-7.ch013

British Council (2023). Transnational education strategy 2023-25. Available online at: https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/transnationaleducationstrategy.pdf (Accessed May 7, 2025).

Carter, D. (2024). The student experience of transnational education. Reading: Higher Education Policy Institute.

Caruana, V., and Montgomery, C. (2015). Understanding the transnational higher education landscape: shifting positionality and the complexities of partnership. Learning Teaching 8, 5–29. doi: 10.3167/latiss.2015.080102

Cohen, D. (2007). Settlement in Singapore over failed university, inside higher. Available online at: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2007/12/13/settlement-singapore-over-failed-university (accessed December 17, 2007).

Council of Europe (2002). Code of good practice in the provision of transnational education. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Cross-Border Education Research Team (2023). List of international campuses. Available online at: https://www.cbert.org/intl-campus (Accessed May 11, 2025).

Dai, K., and Garcia, J. (2019). Intercultural learning in transnational articulation programs: the hidden agenda of Chinese students’ Experiences. J. Int. Stu. 9, 362–383. doi: 10.32674/jis.v9i2.677

Department for Education. (2024). UK revenue from education-related exports and transnational education activity. Official statistics in development. Available online at: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/uk-revenue-from-education-related-exports-and-transnational-education-activity#releaseHeadlines-summary (Accessed May 11, 2025).

Dervin, F. (2023). Interculturality, criticality and reflexivity in teacher education. 1st Edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Djerasimovic, S. (2014). Examining the discourses of cross-cultural communication in transnational higher education: from imposition to transformation. J. Educ. Teach. 40, 204–216. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2014.903022

Eldridge, K., and Cranston, N. (2009). Managing transnational education: does national culture really matter? J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 31, 67–79. doi: 10.1080/13600800802559286

Escriva-Beltran, M., Muñoz-de-Prat, J., and Villó, C. (2019). Insights into international branch campuses: mapping trends through a systematic review. J. Bus. Res. 101, 507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.049

German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). (2014). Transnational education in Germany: DAAD position paper. Available online at: https://static.daad.de/media/daad_de/pdfs_nicht_barrierefrei/der-daad/daad_standpunkte_transnationale_bildung_englisch.pdf (Accessed May 10, 2025).

Healey, N. M. (2015). Towards a risk-based typology for transnational education. High. Educ. 69, 1–18. doi: 10.1007/s10734-014-9757-6

Heffernan, T., Morrison, M., Basu, P., and Sweeney, A. (2010). Cultural differences, learning styles and transnational education. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 32, 27–39. doi: 10.1080/13600800903440535

Hill, C., Cheong, K. C., Leong, Y. C., and Fernandez-Chung, R. (2014). TNE – trans-national education or tensions between national and external? A case study of Malaysia. Stud. High. Educ. 39, 952–966. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2012.754862

International Higher Education Commission. (2023). The role of transnational education partnerships in building sustainable and resilient higher education. Available online at: https://ihecommission.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/IHEC_TNE-report_13_12_2023.pdf (Accessed May 4, 2025).

Knight, J. (2016). Transnational education remodeled: toward a common TNE framework and definitions. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 20, 34–47. doi: 10.1177/1028315315602927

Knight, J., and McNamara, J. (2017). Transnational education: a classification framework and data collection guidelines for international programme and provider mobility (IPPM). London: British Council.

Kosmützky, A., and Putty, R. (2016). Transcending Borders and traversing boundaries: a systematic review of the literature on transnational, offshore, cross-border, and borderless higher education. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 20, 8–33. doi: 10.1177/1028315315604719

Lane, J. E., Borgos, J., and Schueller, J. (2024). Analysing risk in transnational higher education governance: a principal-agent analysis of international branch campuses. Compare J. Comp. Int. Educ. 22, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/03057925.2024.2374300

Lane, J., Schueller, J., and Farrugia, C. (2025). What is an “international student” in transnational higher education? Critic. Int. Stu. Rev. 4:1044. doi: 10.70531/2832-3211.1044

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (2004). Regulations on Sino-foreign cooperative education. Beijing: Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China.

Mittelmeier, J., Lomer, S., and Unkule, K. (2024). Research with international students: Critical conceptual and methodological considerations. London: Routledge.

Montgomery, C. (2014). Transnational and transcultural positionality in globalised higher education. J. Educ. Teach. 40, 198–203. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2014.903021

Naidoo, V. (2010). Transnational higher education: Why it happens and who benefits? Int. High. Educ. 58, 6–7.

New Zealand Ministry of Education (2022). International education strategy 2022–2030. Available online at: https://www.education.govt.nz (Accessed May 11, 2025).

OECD (2012). Guidelines for quality provision in cross-border higher education: Where do we stand? OECD education working papers 70. Paris: OECD.

QAA (2020). Future approaches to the external quality enhancement of UK higher education transnational education. Available online at: https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/international/tne-enhancement-consultation-report.pdf (Accessed May 11, 2025).

Rumbley, L. E., Altbach, P. G., and Reisberg, L. (2012). “Internationalization within the higher education context” in The SAGE handbook of international higher education. eds. D. K. Deardorff, H. De Wit, and J. D. Heyl (London: Sage), 3–26.

Shams, S. M. R. (2016). Sustainability issues in transnational education service: a conceptual framework and empirical insights. J. Glob. Mark. 29, 139–155. doi: 10.1080/08911762.2016.1161098

Stafford, S., and Taylor, J. (2016). Transnational education as an internationalisation strategy: meeting the institutional management challenges. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 38, 625–636.

Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) (2017). Guidance note: transnational higher education into Australia (including international providers seeking to offer higher education in Australia). Available online at: https://www.teqsa.gov.au/guides-resources/resources/guidance-notes/guidance-note-transnational-higher-education-australia-including-international-providers-seeking-offer-higher-education-australia#:~:text=What%20does%20transnational%20higher%20education,note%20on%20Third%20Party%20Arrangements (Accessed May 11, 2025).

Tran, N. H. N., Amado, C. A. D. E. F., and Santos, S. P. D. (2023). Challenges and success factors of transnational higher education: a systematic review. Stud. High. Educ. 48, 113–136. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2022.2121813

Tsiligiris, V. (2025). TNE is a strategic imperative. Times Higher Education. Available online at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/opinion/tne-strategic-imperative-it-cant-be-done-cheap (accessed April 12, 2025).

Tsiligiris, V., and Hill, C. (2021). A prospective model for aligning educational quality and student experience in international higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 46, 228–244. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2019.1628203

UGC (2022). UGC TNE academic collaboration regulations. Pdf. Available online at: https://www.ugc.gov.in/pdfnews/4555806_UGC-Acad-Collab-Regulations.pdf (Accessed May 10, 2025).

Universities UK (2025). Transnational education (TNE) data. Available online at: https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/what-we-do/policy-and-research/publications/features/uk-higher-education-data-international/transnational-education-tne-data#:~:text=Overview%20of%20UK%20higher%20education,60.9%25%20from%202018%E2%80%9319 (Accessed May 11, 2025).