- imec-SMIT, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium

Since the introduction of Article 7a in the Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD), which enables Member States to impose measures that ensure prominence of general interest services on user interfaces, discussions within media policy on the need of these measures have increased markedly. In Member States such as Germany, France, Italy and Ireland, commitments were already imposed on players offering user interfaces to audiovisual—and in some cases also audio—media services and content of general interest. This article presents the findings of a study examining the desirability and feasibility of implementing due prominence measures in Flanders (Belgium). The research adopts a media policy analytical approach and examines the (i) positions of the different stakeholders on the desirability and feasibility of a revised prominence regime, (ii) the extent to which interests across different stakeholders can be aligned and (iii) the considerations governments need to take into account when developing due prominence measures in Member States. The research is based on a stakeholder consultation conducted with broadcasters, television distributors, streaming services and hardware manufacturers operating in the Flemish market. The research is complemented with interviews with representatives of different market actors. The study identifies considerable oppositional logics between broadcasters and hardware manufacturers and raises challenges in defining the scope of ‘general interest’, the addressees of prominence measures, contextual factors such as markets size and path-dependency in media policy, and the commensurability between different existing legal frameworks at the national and EU level. The authors argue for clearer, more explicit guidelines at the EU level regarding the interpretation of Article 7a.

Introduction

The shifting dynamics of how audiences discover, access and consume content in a highly fragmented media landscape has brought a heightened academic and regulatory interest in the past few years on the notions of prominence and discoverability. Evens and Donders (2018) argued that future profitability of the broadcasting industry will be linked to the control over the operating system (OS), interfaces and digital marketplaces. On the same idea, Johnson (2020, p. 172) underlines the presence of an ‘economics of prominence’, in which “device manufacturers, app providers and platforms sell access to the most prominent positions within their user interfaces (UIs).” In a landscape driven by algorithms determining which content and services are promoted, how easy they are found and whether audiences can come across it, there is a risk that the content surfacing on interfaces is a result of commercial decisions, disadvantaging the smaller creators and providers (Desjardins, 2016), and actors who do not have the financial nor the negotiation power to strike deals for such visibility (Afilipoaie et al., 2021). Since 2015, regulation on prominence, alongside ensuring the prominence of particular content (for example European works) and services (the visibility and findability of services considered relevant for public interest reasons) has gradually been introduced on the policy agenda. Regulatory interest in interfaces grew especially due to the challenges met by broadcasters, especially Public Service Media (PSM), in making audiences aware of their services (Hesmondhalgh and Lotz, 2020; Rozgonyi, 2023). PSM assert their mission and responsibilities to serve the public interest rather than commercial and political agendas, and ensure the accessibility and reach of high-quality, culturally diverse and impartial content, are undermined by private interest-ruled players via algorithmic recommendations and commercial deals. This magnifies the concerns regarding the marginalization of voices and perspectives, threatening cultural diversity and society at large. Indeed, just because services and content are made available, it does not mean that they are also clearly visible, easily findable and thus discovered. The various content curatorial decisions aid audiences to navigate the seemingly endless amount of content on catalogues and services. Yet audiences seem to struggle to find something to watch and many give up on watching altogether as a result of choice overload (Lobato et al., 2024).

Since the introduction of Article 7a in the 2018 revision of the Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD) (European Union, 2018a), Member States have been provided a dedicated legal instrument to enforce due prominence measures for general interest services and content. While ‘media services of general interest’ can be a label that extends beyond solely PSM and comprises certain commercial media, it is mainly PSM that advocate for such rules as they fear that the access to and the visibility of their services are being limited in an online TV landscape heavily disrupted by platform-based media providers (Garcia Leiva and Mazzoli, 2023).

The implementation of prominence measures is, however, complex (Rozgonyi, 2023). For instance, Article 7a does not specify what is considered to be a service of ‘general interest’ or how ‘prominence’ should be achieved (Ledger, 2023). Furthermore, assessing discoverability of media services of general interest is challenging, due to the variety of spaces considered, hardware shortcuts, TV and smartphone app overviews, smart TV interfaces or voice assistants (Johnson, 2020). Moreover, the opacity of algorithms and recommender systems leaves regulators with limited insight into the mechanisms that determine the placement of services and content of general interest on the UIs, as well as into existing commercial deals—often involving international subscription video on demand (SVOD) services or video sharing platforms and hardware manufacturers—that affect prominence. Following platform co-regulation practices, National Regulatory Authorities require platforms to demonstrate prominence assurance, although with limited means to verify claims (Ranaivoson and Domazetovikj, 2023). Lastly, European policy contexts differ significantly and are characterized by distinct path-dependencies with existing measures and definitions (Kostovska et al., 2023), which render the transpositions of rules and lessons learned difficult across different policy contexts.

Most of the Member States that transposed Article 7a into their national laws did so word by word, without further clarifications. This was also the case in Flanders, when in 2021 the region transposed the article into its Media Decree, the main media law that regulates the Flemish media landscape. Upon transposing the AVMSD, the government at the time did commit to further elaborating on the article’s definitions and specific measures. Since 2022, increasing concern and open criticism on the lack of discoverability of content on the interfaces of smart TVs and voice assistants were voiced by the public service broadcaster. Ahead of the Flemish elections the Flemish the regional elections in the Spring of 2024, a symbolic call for action by the three largest broadcasters in Flanders (Delaplace et al., 2024) and political calls in the Flemish Parliament (e.g., Vandaele et al., 2024)—instigated a media policy window (Steen-Johnsen et al., 2019) in Flanders in which the necessity of due prominence rules would take center stage.

Seizing the momentum of this policy window, our research addresses questions surrounding (i) the desirability and feasibility of a revised prominence regime, (ii) the extent to which interests across different stakeholders can be aligned and (iii) the considerations governments need to take into account when developing due prominence measures in Member States. The research builds on evidence collected through a stakeholder consultation part of an independent academic study commissioned by the Flemish Government in preparation of a revised prominence regime; the study was conducted by the authors of this article. The research is comprised of a literature review and document analysis to identify key themes and considerations for policymakers when deciding to introduce prominence measures. The consultation combines written statements and interviews from all (participating) relevant stakeholders operating in the Flemish markets, as well as a series of additional interviews with key representatives of stakeholders and representatives of European media regulators. The recommendations of the study directly serve the development of due prominence measures in Flanders.

The first part of the article theorizes the concepts of prominence and discoverability, and contextualizes the shifting dynamics within the audio(visual) market as part of this discussion. The second part outlines the methodology, and it is followed by the findings section which is comprised of two sub-sections. On the basis of the policy scan, the first part identifies four key themes that are relevant to examine when developing due prominence measures in European markets. The second part of the results section presents the findings from the stakeholder consultation. The final part outlines key lessons learned on the implementation of Article 7a for the EU Member States and frames the findings within the field of media policy and platform governance studies.

The routes to content and conceptualizations of prominence and discoverability

Although creating opportunities for audiences to find, explore and ultimately consume diverse content, questions are raised concerning the mechanisms guiding or affecting the discoverability of content and services in a digital environment (Salganik et al., 2024). Mazzoli and Tambini (2020) define discoverability as the likelihood of content to be discovered and interacted with. Discoverability is part of the content prioritization design and algorithmic decisions. Along the same lines, McKelvey and Hunt (2019, p. 1) argue that discoverability is “a kind of media power constituted by content discovery platforms that coordinate users, content creators, and software to make content more or less engaging.” McKelvey and Hunt (2019) propose a framework composed of three dimensions that lead to discoverability: platform interfaces (surrounds), the pathways users take to find content and the effects those choices have (vectors), and the user experiences resulting thereafter. Inspired by McKelvey and Hunt’s (2019) framework, Salganik et al. (2024) propose a Discovery Ecosystem framework of six interrelated components, each playing a role in the content discovery process; although written with the music sector in mind, the framework is also applicable to other creative sectors. Presentations, one of the six components related to this article’s topic, are defined as “mediums used for presenting information, focusing on various design choices for organizing content within online interfaces” such as the size, the placement and relational positions (Salganik et al., 2024, p. 3). How the information is presented on the interface affects the likelihood of interactions with it, and thus, leading to its discovery (Vannieuwenhuyze et al., 2021; Salganik et al., 2024). Hesmondhalgh and Lotz (2020, p. 389) describe video interfaces as “hubs of media circulation power” due to their centrality and ability to direct audiences towards certain content and away from other. This steering on the interface is done through the various design choices—as mentioned in the Presentations (Salganik et al., 2024)—and through various other means such as “promotional carousels, recommendations, curated and algorithmically-generated recommendations rows, search pages, and ads” (Lobato et al., 2024, p. 1333). The ease of discovery on the interfaces is linked to the ease of visibility, which leads us to the concept of prominence, a concept rooted in the discussions concerning the Electronic Programming Guides (EPGs).

According to Mazzoli and Tambini (2020), prominence is a content prioritization design choice understood as the placement of certain content and services more favorably than other. This could be the result of search and recommendation bias, poor third-party integration but also the prioritization of commercially lucrative content over other content and services (Lobato et al., 2023; Gillespie, 2014). Content and services can also enjoy a more prominent placement as a result of viewers and listeners interacting with them (e.g., viewing, liking, bookmarking for later interaction), but also due to third-party deals and self-preferencing practices (i.e., in-house or owned intellectual property and services). Examples of such self-preferencing practices include Amazon Prime’s or Netflix’s catalogues showcasing their own originals much more prominently over other titles in their catalogues, iPhone privileging Apple apps over similar services or Sony TV clearly making its Sony Pictures titles easily available for viewers on their smart TVs. The recent rise of various Free Ad-supported Streaming TV (FAST) services, allowing to expand channel portfolios at a rapid pace, and often offered by smart TV manufacturers/OSs, has added an extra layer of competition for classic broadcasting content and services. To exemplify, Samsung TV Plus—the FAST service of Samsung—comes preinstalled on all Samsung TVs and offers hundreds of live channels with availability differing by region (Samsung, 2024; Clover, 2024). Likewise, Google and Amazon (via Google TV Streamer and Amazon Fire TV respectively) offer hundreds of FAST channels, combining traditional TV functionalities with the flexibility of streaming services.

Commercial agreements with third parties tend to favor well-funded players—such as US-based streaming giants like Netflix—who can afford to pay for prominent placements. In contrast, smaller players or those operating in much smaller markets, like PSM, often lack the financial resources to negotiate and secure advantageous positions on UIs. As a result, their content risks remaining undiscovered due to insufficient visibility or prominence, significantly reducing the likelihood of user interaction. Over time, these smaller actors may be forced to exit the market. Additionally, with consumers being directed towards higher-priced services or less-fitting offers, content variety and quality on these services might deteriorate. Ultimately, as Krämer and Schnurr (2018) argue, it is the consumer that suffers.

To summarize, in theory, separating the concept of discoverability from that of prominence helps policymakers to clarify the goals of their respective policies. In the case of discoverability, the policy goal is to make the service or content easily discoverable (i.e., ensure that content can be found) and thus increasing users’ potential interaction with it. In this case, the ease with which the content can be found is linked to the discovery taking place through active search, algorithmic recommendations, metadata, tagging and various categorizations. For example, ensuring metadata quality and optimizing the search engine for local content are only a few ways to facilitate the discoverability of content. Finally, discoverability mostly involves active user participation. If the policy goal is to proactively push certain content or services in front of the audiences (i.e., ensure that content is unavoidably seen) for various reasons, including the safeguarding of public interest, due prominence is used as a means to guarantee visibility and findability of particular content. Prominence is about the proactive decision to prioritize the position of the content or services within the UI in a clearly visible place (e.g., homepage, top rows). In practice, prominence can be considered a subset of discoverability, simply because prominence is just one other way of making content discoverable by making it impossible to miss (see, e.g., research on placement of content on interfaces of PSM portals (Bruun et al., 2025)).

In the context of this research, we focus particularly on the prominence and discoverability of services of general interest (SGIs) on audiovisual interfaces or through audio commands in the context of voice assistants. As non-linear viewing becomes the dominant way people consume video content, smart TVs attained a high level of significance as gatekeepers. They allow TV manufacturers and OS providers to position themselves as key players, competing with service providers and device suppliers by serving as gateways to entertainment. TV manufacturers can modify the interface by pre-installing apps, placing shortcuts, and other forms of prioritization throughout the interface (Lobato et al., 2023). The widespread adoption of smart TVs and connected peripherals is accompanied by increasing offers of free alternative viewing options to cable subscription and, to an extent, to streaming services. Companies such as Google, Amazon and Apple did not stand by idly and developed their own so-called streaming boxes which are hardware devices attached to the TV set and connected to the internet, that serve as interfaces organizing streaming services, live TV and apps (Raats et al., 2025). According to Eurostat (2023), in 2022 already more than 52% of people in the EU were using a smart TV. When it comes to smart streaming devices (e.g., streaming boxes and streaming sticks), according to Statista (2024), the revenue generated in Europe amounts to EUR 1.7 billion, being projected to increase to EUR 2.7 billion in 2029 with approximately 59 million units sold.

Important to note, however, is that user-agency is also a factor to consider as there is a clear difference between content that users are exposed to and content that they actually consume (Hildén, 2022). Moreover, as Johnson et al. (2023) and Lobato et al. (2024) highlight, audiences interact with recommendations depending on their developed habitual behaviors, literacy, and expectations. Therefore, the interaction with UI design is not homogenously across all viewers, with those less digital literate feeling less confident to use the TV technologies and services to find and access content to watch.

To summarize, individuals’ choices about what content and on which service to consume, take place in a carefully curated technological environment which potentially affects societal values such as freedom of choice and diversity. This highlights the importance of how content and services are presented on UIs and the necessity of adequate recommendations that surface not only personalized content and content bound by commercial agreements but also recommendations that reflect public interest characteristics of media services and content.

Materials and methods

For this case study (Broughton Micova, 2019), we rely on a mixed methods media policy analysis approach (Freedman, 2014). A first phase included an identification of existing regulations across European markets to identify the key themes for the stakeholder consultation. This phase consisted of a literature review of existing scholarly work as well as aggregated data within studies by the European Commission (hereafter the Commission) and European Audiovisual Observatory on prominence and discoverability (Rozgonyi, 2023l; Garcia Leiva, 2024; Ledger, 2023; European Commission et al., 2022; Cappello, 2022). Additionally, we conducted a document analysis of relevant regulatory documents (laws, policy notes and regulatory guidelines) from Member States in which measures on prominence have been introduced.

The analysis of existing prominence regimes served as the basis for the stakeholder consultation, which was part of a larger study commissioned by the Flemish Government and conducted by the authors. The study is part of the governments’ multi-stakeholder approach, through which it wants to use evidence-based practice and the multi-stakeholder dialogue (Donders et al., 2019) to formulate its proposed legislation. For this study, a first consultation was sent out to relevant stakeholders based in, or offering services in the Flemish market. The consultation composed of 10 questions sent out to 22 stakeholders who were clearly briefed on the objectives of the study, inviting them to reply ‘on the record’, as their input was going to directly serve as a basis for the recommendations advanced to the Flemish government. The stakeholders consulted are PSM, commercial and regional broadcasters, distributors, the Flemish Media Authority, smart TV manufacturers, and regionally as well as internationally operating SVOD providers. 15 stakeholders submitted their answers between February and June 2024. Secondly, a total of 16 complementary interviews were conducted with scholarly and industry experts on the matter between March and June 2024, particularly to contextualize some of the input from the written consultation, and to test perceptions on the desirability and feasibility of some of the suggested scenarios by the stakeholders. Our stakeholder inquiry focused primarily on the development of a prominence regime for audiovisual services and content. As such, we did not consult actors exclusively offering audio or radio services. Nevertheless, various consulted stakeholders include audio or radio services in their portfolio and brought these issues up during the consultation. Based on the consultation and interviews, we commenced the stakeholder analysis (Flew and Lim, 2019; Van den Bulck, 2019) by categorizing the surveyed stakeholders. This initial categorization was done on the basis of the stakeholders’ guiding logics and their attitudes towards the policy issue in its most fundamental form, in this case the extent to which they were in favor or against an updated prominence regime in Flanders.

Results part I: what regulation stipulates and the analyses of policy frameworks

Until the revision of the AVMSD in 2018 (European Union, 2018a), online content curation practices related to online curation and prioritization decisions were not covered by a specific regulatory framework. The revision of the AVMSD included optional prominence provisions through Article 7a, which reads that Member States can “take measures to ensure the appropriate prominence of audiovisual media services of general interest.” Currently Germany, France and Italy have been introducing measures (Raats et al., 2025). While the Commission did not contest the German transposition, which also covered UI providers (such as, e.g., EPG providers, OS providers or in-car entertainment system providers) established outside its national jurisdiction, the Commission did contest France’s and Italy’s transpositions under the Single Market Transparency Directive (EU) 2015/1535 (European Union, 2015); mostly concerning incompatibilities with the country-of-origin principle enshrined in Article 3 of the e-Commerce Directive (European Union, 2000). In Flanders, the Government agreed on a proposal on July 4th 2025, and, at the time of writing, was still to be approved by the Flemish Government in the same year. Discussions in Ireland and the Netherlands are pointing towards legislative developments likely to take place in the future. In Sweden, the regulator MPRT (2023) did not consider prominence to be a problem and advised against further regulation, much to the dismay of Swedish public broadcasters. Outside of the EU, the United Kingdom has also introduced extensive rules on prominence in its Media Act, which received Royal approval in May 2024 and is being implemented at the time of writing (Ofcom, 2025).

Matters related to the (in)compatibility between Article 7a and other existing rules within the EU legislation, do not only relate to the compatibility with the e-Commerce Directive, but also to existing rules on EPGs and must-carry rules as included in the Electronic Communications Code (ECC) (European Union, 2018b). Additionally, more recent discussions related to the interpretation of Article 7a in light of Article 20 of the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA) (European Union, 2024)—which grants users full control over the way they organize visibility of services on interfaces—were also raised. These are just some of the key issues that make the implementation of prominence measures highly complex (Rozgonyi, 2023). The analysis of the legislative transpositions on prominence reveal four key themes that are central to shaping prominence rules.

Theme 1: defining which services (or content) are of general interest

Article 7a does not specify what is a SGI. This leads to arbitrary readings of concepts which in turn complicates the policy-making process across the Member States. The addition of the non-binding recital 25 accompanying Article 7a, complicates matters further as the former refers to ensuring appropriate prominence for the content of general interest, as opposed to the service in its entirety as stipulated in the latter. Although most of the countries that transposed Article 7a did so by considering the entirety of the SGI and not their specific content, our interviews revealed that some countries plan to go down the route of recital 25. The remaining question is thus, which services can qualify as having a general interest. By default, the service of the PSM qualifies due to their public remit. Some countries like the UK (UK Government, 2024) and Ireland (Government of Ireland, 2022) limit the beneficiaries to the PSM only, whereas the rest expand it to qualifying commercial broadcasters as well, based on various criteria. In Germany this criterion includes, among others, the time dedicated to reporting on political and historical events, the ratio of own productions versus content produced by third parties, accessibility quotas, quotas for showcasing European productions and quotas for offerings aimed at young target groups (Die Medienanstalten, 2020). Usually based on a designation criterion, several countries include radio services under the definition of an SGI.

Theme 2: the players captured

There are various ways to access online content on a TV. Generally, the main gateways are smart TVs (e.g., through EPGs, home screens enabled by OSs, hardware shortcuts, TV app stores), TV peripherals (e.g., streaming TV devices and sticks such as Google TV Streamer, Amazon Fire TV, Roku; telecom service providers’ set-top-boxes; shortcuts on remote controls), smartphones (via app stores and through the casting function on the TV) and game consoles (PlayStation, Xbox). Smart speakers (through the voice assistants) can be used to surface content via voice command, a feature most popular in North America (European Broadcasting Union, 2024). It is unanimously agreed that content prioritization occurs both at the level of the device’s UI and its design, the hardware layers which serve as the initial gateways to content, and at the level of the service’s UI, the different software layers with their distinct designs, browsing, searching, and recommendation system functionalities. Although in all the jurisdictions the focus is on smart TVs and their different UIs, in some countries like Germany, the prominence rules extend to all devices with a UI. Moreover, compared to the other countries, Germany is the only jurisdiction where the in-car entertainment systems of certain car manufacturers (Audi, BMW/Mini and Tesla) were officially categorized as a UI (Krieger, 2024). Although this inclusion was primarily done with audio/radio in mind, it also extends to audiovisual content. To determine which UIs are captured, some of the transposing countries have established criteria based on user reach, monthly unique visitors and number of connected units.

Theme 3: making content prominent

Article 7a does not mention how ‘prominence’ should be achieved (Ledger, 2023). On the matter of prominence of European works (Article 13(1) AVMSD), recital 35 highlighted three ways in which Member States could ensure their findability and accessibility: (i) the services’ homepage; (ii) attractive presentation; (iii) search tool. The responsibility and control over content prioritization measures varies depending on the role of different industry actors at the level of the device’s UI and the service’s UI. Inspired by the proposed solutions in recital 35, some of the countries included similar requirements in their rules and guidelines for ensuring the prominence of SGIs. These measures include highlighting those SGIs on the homepage or under a separate tile/category which includes all SGIs, resurfacing these services in recommendations to the users and in the search results of services and content searches carried out by users, or on the remote controls of the devices. Some provisions are more granular, like in the case of Italy, where the SGI category must be named ‘Highlights’ with a logo/icon approved by the Italian regulator, which must be placed on the homepage at the first level of the user offering and must include all the icons/logos of the SGIs in the same order of assignment as the corresponding EPG numbers. Users must be able to access the SGIs in a maximum of two clicks regardless of device (Raats et al., 2025).

Theme 4: reporting transparency and supervision

In all transposing countries, the media regulators are responsible for various tasks, which include (i) publishing and updating of the lists including the recognized SGIs, and the list of addressees to comply with the rules; (ii) elaborating on concrete prominence measures and drafting of guidelines; (iii) evaluating the measures adopted by the service providers and the UIs and monitoring compliance with the rules; (iv) facilitating the cooperation between the stakeholders; and (v) sanctioning non-compliance, issuing reminders and fines. However, platforms and services often treat their algorithms as proprietary or confidential. Without transparency, regulators cannot understand how algorithms rank or display content, limiting their ability to verify if SGIs and their content are being given the required prominence in search and recommendation functions, and whether the measures to ensure prominence are effective or not. Moreover, algorithms are dynamic—they continuously evolve based on user interactions and other variables, making consistent monitoring even more challenging. Finally, attributing decisions to algorithmic processes, makes it harder for regulators to hold those responsible for implementing them accountable in case of non-compliance.

Some of the conclusions emerging from all these cases are that (i) no two legislations are the same; (ii) the national context plays an important role; (iii) different implementations are met with resistance from UI providers; and (iv) there is a concern in several countries that PSM—and, in some countries, additional players—seem to be at the mercy of global players and their commercial deals to fulfill their public service mission.

Results part II: stakeholder consultation

Relevant stakeholders in the audiovisual market

The Flemish audiovisual market (consisting of approximately 6 million inhabitants) is comprised of one public service broadcaster VRT and two larger commercial broadcasters VTM and Play Media. The former is part of DPG Media (which is also active in the French-speaking part of Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark) while the latter is part of Liberty Global-owned Telenet. Aside from the three generalist broadcasters, there are 10 regional television broadcasters—operating through a public license and a mixed public-private financial model—and 10 other small thematic channels.

A second category of stakeholders are the television distributors. Proximus, Orange and Telenet are the most important distributors of digital television in Flanders. Important to note in this analysis is that in Flanders, television distributors pay retransmission fees to broadcasters in return for carrying the broadcasters’ signals. Television distributors are also required to pay a distribution fee to regional broadcasters (Donders and Evens, 2014). While cord-cutting has increased steadily in recent years, due to bundled offers of fixed-line telephone services, mobile services, pay-television through cable or Internet Protocol television and broadband internet (i.e., quadruple play), distributors still hold a strong position in Flanders. They are increasingly integrating on-demand and pay TV offerings and combined packages that include Netflix and other streamers. Their interfaces have been evolving away from the EPG-logic to a catalogue-logic interface in which broadcasting offerings are integrated within broader sets of tiles and decks centered around multiple titles and apps.

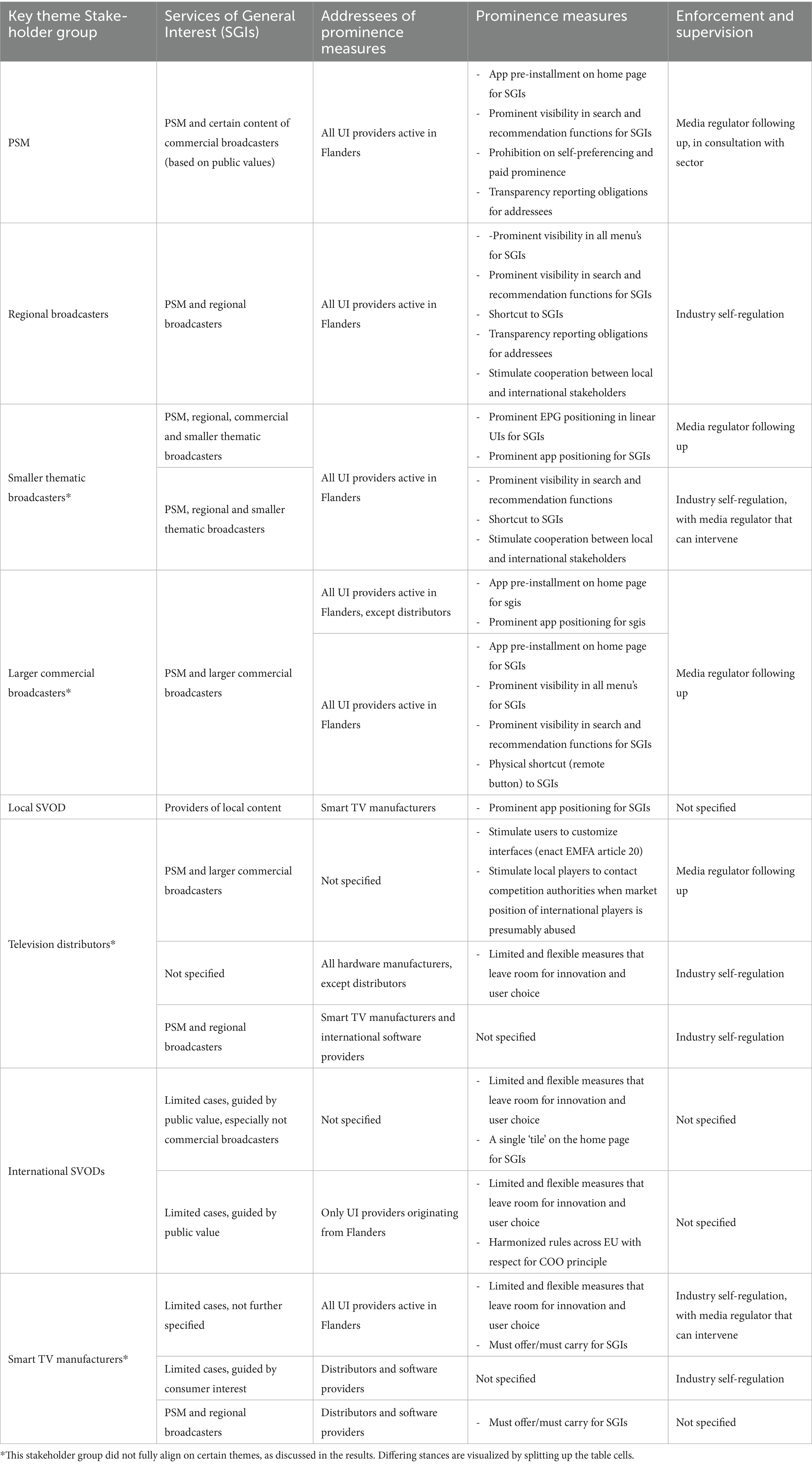

A third stakeholder category comprises the domestic SVOD service. Since 2020, Streamz, a joint venture between DPG Media and Telenet, is a domestic SVOD service operating with predominantly local content (VRM, 2024). A fourth type affecting and affected by prominence discussions are the international streamers, which have been increasingly integrated in the interfaces of smart TVs. Around six out of ten people in Flanders have access to at least one streaming service, with Netflix reaching 47%, followed by Disney+ at 19% reach (De Marez et al., 2024). A fifth category are the different smart TV manufacturers. At the time of writing, 65% of households in Flanders owned a smart TV (De Marez et al., 2024). The consultation involved stakeholder positions for each of these categories of players. Table 1 visualizes the stakeholders relative to their positions on the four key themes that are central to shaping prominence rules.

Table 1. Matrix of surveyed stakeholder groups relative to their positions on the four key themes that are central to shaping prominence rules, in Flanders.

Desirability and necessity of prominence measures in Flanders

In line with the findings of Garcia Leiva (2024), a sharp contrast was visible between domestic broadcasters and international video-on-demand streaming services and hardware manufacturers. In terms of the guiding logics (Van den Bulck, 2019), supporters of regulatory intervention base their stances on either the importance of (local) public values (like media pluralism, education, local information, etc.) as well as the importance of a level playing field between legacy and local players versus international players. Both the PSM and the two largest commercial players recognize the need for regulation in response to a perceived significant shift in the power balance in favor of international streaming services and technology platforms. These businesses engage in direct commercial agreements with hardware manufacturers or distribute their own hardware, allowing them to secure preferential positioning on the UI of smart TVs, as well as on other devices such as smartphones, video game consoles, media streaming devices (such as, e.g., Google Chromecast/TV Streamer), and voice assistants. Given the limited territorial coverage, local broadcasters claim they are either not invited to or lack the funding to strike deals with these global players. All broadcasters emphasize the importance of locally produced content to be locally visible and findable on services, which implies that local content—in Flanders—should be easily findable and discoverable. In a common statement released shortly before the June 2024 elections, the three largest broadcasters published a memorandum demanding ambitious media policy, of which prominence rules were the prime demand (Delaplace et al., 2024). Prominence rules should, according to the broadcasters, encompass both audiovisual and audio measures. Although smaller broadcasters, notably the regional broadcasters and some smaller thematic channels, were not included in this alliance of broadcasters, they are also in favor of regulatory intervention.

International streamers, as well as the smart TV manufacturer with the biggest international market share, stated that regulatory intervention regarding prominence would be undesirable. One of the international streaming services opposes such regulatory intervention as they are concerned by “the potential legal fragmentation any such Member State-specific rules would introduce” (written stakeholder consultation). They substantiate their position by relying on the ‘country-of-origin’ principle (originating from Article 2 and 3 AVMSD and enshrined in Article 3 of the e-Commerce Directive) by which they would only have to comply with the German regulation; as this is currently the European country they are officially located in, despite being active in the whole of the EU. One of the international SVODs would accept prominence measures, but only if the measures exclusively target services and/or devices whose country of origin is Belgium. With this statement, the SVOD echoes discussions on the legal validity of transpositions of Article 7a, as is the case in France and Germany, countries that target players located outside of their borders.

A smaller smart TV manufacturer also finds prominence rules rather undesirable, but favors “minimal, simple, reasonable (rules) and based on industry standards” (written stakeholder consultation) should the government proceed in developing prominence legislation. Arguments put forward to oppose legislation are (i) a presumed lack of evidence that smart devices are effectively making domestic apps less visible; (ii) the belief that consumer sovereignty should prevail over prominence and should not be hampered; and (iii) the assumed increasing costs for hardware manufacturers to customize interfaces and hardware to different markets across Europe, particularly for small ones. Thus, hardware interventions for a low return-on-investment market like Belgium—which, on top of that, consists of a Dutch-speaking and French-speaking part each with their own beneficiaries of prominence—would be very costly. The cost argument is particularly mentioned concerning the visibility on remote control buttons. Smart TV manufacturers claim the costs of customizing remote buttons would be high and consequently detrimental for customers. These stakeholders propose to shift the regulatory focus away from hardware interventions to, for example, the digital environments of telecom distributors and (meta)data that audiovisual services signal through.

Situated somewhere in between the positions of the foreign on-demand services and domestic broadcasters is the position of the domestic television distributors. In principle, they are against legislation, but to some extent, they also support the demand of broadcasters for a level-playing field. This implies that they can cope with regulation if it does not affect them, as they already have in place agreements with broadcasters which include among others, their placement on the UIs. The participating distributors with roots in Belgium point out that international players in the smart environment have less attention for local content and the health of the local Flemish ecosystem, implicitly welcoming—or at least not opposing—legislative intervention against such international players.

Addressees of prominence measures in Flanders

The coalition of stakeholders that welcomes regulatory intervention is also united in their stance on which services and devices should be targeted by prominence measures. With the exception of one larger local broadcaster, who is of the opinion that distributors should not face additional regulation, all local broadcasters—big and small, thematic, regional and national—are in favor of regulating the whole range of smart devices and services that offer intermediating UIs; it is, however, important to remark that this broadcaster is fully owned by one of the television distributors, which explains a diverting view. This television distributor itself refrained from replying further on this topic. The other local distributor was mostly of the same opinion as the previously mentioned larger broadcaster, only differing on the scope of the targeted devices. As this local distributor wants to keep regulatory intervention at a minimum compared to the broadcasters, it only explicitly mentions smart TVs as players with whom negotiations might benefit from policy intervention to mitigate “the absence of sufficiently similar interests” (written stakeholder consultation).

More disparate views were present amongst the group of international stakeholders that deems prominence measures undesirable. One of the international SVODs and all three of the smart TV manufacturers oppose a regime that would introduce region specific (e.g., Flanders) technical requirements for addressees of prominence rules. Only a minimum of EU harmonization is desirable for them. Standing out the most on this question were perhaps the smaller smart TV manufacturer and one TV distributor. Although not in favor of intervention, they would not oppose rules if such rules were to address specific problems identified in the market. In that case, they would prefer the introduction of a technology neutral approach, thus possibly subjecting all types of smart devices to the new regulation. They justify their position by arguing for the need to establish a level playing field among the various technologies that deliver or utilize audiovisual media services such as “smart TVs, smart audio devices and set-top boxes as Apple TV, Google Chromecast/TV Streamer, etc.” (written stakeholder consultation).

Stakeholders advocating for prominence regulation emphasize that the scope of prominence measures should not be limited solely to audiovisual UIs. Especially public broadcaster VRT has been highly vocal about the inclusion of voice assistants, smart speakers, and in-car interfaces within the regulatory framework. For in-car interfaces, the primary concern is ensuring access to and visibility of broadcast radio, particularly through a dedicated radio button or shortcut on media UIs in vehicles. This issue has also been highlighted by the EBU, which has coordinated efforts over the past year to develop a Europe-wide solution through its ‘Connected Car Playbook’ initiative (Granryd, 2024). Findability of radio channels is also mentioned explicitly by other broadcasters who offer radio channels. VRT further stresses the need for voice assistants to direct users to their own online portal when, for example, requesting one of their podcasts via voice commands, rather than redirecting them to third-party platforms such as Spotify.

General interest and beneficiaries

A key challenge in implementing prominence measures is determining how broadly the scope of services of general interest should be defined. This issue raises three main questions for policymakers. First, should the list of beneficiaries extend beyond public broadcasting organizations, and, if so, what criteria should be used to determine eligibility? Second, do players get the status of beneficiary based on their entire offering, or only particular forms of content (such as news, documentary or children’s programming)? Third, at what level should beneficiary status be assigned—should it apply to a broadcaster and all its associated apps, to individual apps, or to specific broadcasting channels? While stakeholders remained relatively vague on the last point, their responses to the first two questions suggest an initial consensus, though closer examination reveals nuanced differences. All broadcasters agree that the PSM should qualify as a service of general interest. However, perspectives diverge when defining who else should be included. Most consider themselves to be of ‘general interest’ but do not necessarily share that view for others. The PSM considers itself to be of general interest, together with “certain content of the commercial broadcasters according to criteria based on media pluralism, freedom of speech, cultural diversity” (written stakeholder consultation). In contrast, the two largest commercial broadcasters consider their entire content offering to be of general interest. While this creates a partial alignment among the three major broadcasters, none explicitly advocate for including smaller regional broadcasters or thematic channels as beneficiaries of prominence measures.

Smaller regional broadcasters, however, argue for a prominence framework that benefits them alongside the PSM. They justify this position by highlighting their existing must-carry status under the Flemish Media Decree, which requires television distributors to offer regional broadcasts across different Flemish provinces. Given this legal recognition of their role in sustaining media pluralism, they contend that their inclusion as beneficiaries is a logical extension. Meanwhile, some thematic broadcasters propose a more restrictive interpretation, limiting general interest status to the PSM, regional broadcasters and themselves—while explicitly excluding the larger commercial broadcasters. Additional issues can arise from this position of the smaller broadcasters. First, if smaller thematic and regional players consider themselves as beneficiaries, it is implied that each of them should have an application that can be made prominent. Thus, they should provide such apps with the necessary (meta)data that UIs require to make their services searchable and visible. Efforts to develop a joint VOD application to create synergies among these players, could help mitigate part of the financial impact such an initiative would have. Nevertheless, discussions in this direction have so far achieved limited progress.

Two of the smart TV manufacturers propose to attach prominence rules to obligations for the beneficiaries/providers of general interest services or content. Put simply, if beneficiaries want prominent visibility for their services or content, they must first comply with industry standards in terms of (meta)data signaling to ensure availability on and compatibility with the desired smart devices. Such an agreement would shift part of the technical, and thus financial, burden from smart manufacturers to the providers of media (services) of general interest. Another important issue, raised by most of the stakeholders opposing prominence measures, is the presumed need to keep the list of beneficiaries as limited as possible. To support their cases, most of them refer to the prominence rules in Germany, which resulted in a rather long list of beneficiaries, which they consider as a “counterproductive” transposition of Article 7a (written stakeholder consultation); or, as formulated by one of the stakeholders formulated it, “if everyone has prominence, ultimately no one has prominence” (written stakeholder consultation).

When inquiring on what level prominence measures should be taken—that of the entire service or that of the (disaggregated) content—we observed most consensus exists on the proponents of the ‘service-level’. One of the local commercial broadcasters and one of the thematic broadcasters would go as far as to install measures on both the level of the service and the content level. Most of the stakeholders though, are explicitly in favor of rules on the service level: the PSM, the local SVOD, a thematic broadcaster, the regional broadcasters, and a local distributor shared this vision. The two bigger smart TV manufacturers prefer rules on a service level, should they be imposed. Finaly, two of the distributors stated to have no preference for measures on either level.

Measures to enact due prominence for SGIs

The specific measures proposed by our surveyed stakeholders unsurprisingly diverge, yet some similarities could be noticed. All stakeholders in the coalition welcoming prominence legislation proposed in some way or form that prominence should be perceived as “increased visibility and findability.” All of them stated that prominence or prominent visibility in search functions and in recommendations should be assured for the beneficiaries of a prominence regime. On top of these proposed rules, the PSM and the two larger commercial broadcasters pled for pre-installation of SGIs and visibility on the homepage of the UIs designated smart devices. The PSM, the larger commercial broadcasters, the smaller thematic and regional broadcasters, all desired a designated shortcut, either virtual on a home screen or, as favored by some, physical on TV remote controls, directly linked to the SGIs.

Some stakeholders also explicitly mentioned the visibility of beneficiaries’ content in the different content decks on UIs. One of the commercial broadcasters wanted content of general interest to make up a “substantial percentage of the currently visible part of content decks” (written stakeholder consultation). Less outspoken were stakeholders on the question whether prominence obligations could be seen as complementary to or replacing existing commercial deals between players (such as the deals between hardware manufactures and global streamers), or, whether players that have been awarded the status of beneficiary could get this as part of a commercial deal, and, finally, whether players that receive the status of beneficiary could negotiate additional deals with the owners of UIs for even better placement or findability. In that regard, the PSM proposed to a prohibition on prominence in return for financial contributions in Flanders. The smaller regional broadcasters and one of the thematic channels, on the other hand, want to include the “stimulation of market agreements” (written stakeholder consultation) between local and international players in a prominence regime. The regional broadcasters also pled for periodical evaluation on the effectiveness of prominence rules.

The coalition opposing prominence legislation, or favoring as little interventions as possible, referred to guiding logics of safeguarding innovation and user sovereignty to substantiate their positions. One of the international SVODs would agree to prominence measures if all beneficiaries of prominence measures were to be grouped together under a single tile on the home screen, as opposed to granting them all a prominent position separately.

All stakeholders agree that any legislative intervention should not come at a high cost; it should not stifle innovation and interventions should not impede the users’ sovereignty. Yet, for the latter, it remains very vague as to when stakeholders consider user sovereignty to be harmed. In that regard, a somehow ambiguous position is defended by the large smart TV manufactures. They continuously stress the importance of the user interest, yet at the same time, these players place their own paid services and content, (regardless of their popularity amongst users) significantly more visible in different UIs. One of the local distributors suggested to include the promotion of Article 20 of the EMFA in a Flemish prominence regime. The promotion of this article, on ensuring the user’s right to customization of the media offer, ought to increase users’ digital literacy and stimulate them to put the Article into practice. They also proposed to stimulate stakeholders in the Flemish media ecosystem to get in touch with competition and anti-trust authorities when suspecting that international players are abusing their dominant market position.

Enforcement and supervision

As a final point in our inquiry, we examined stakeholders’ perspectives on the supervision and enforcement of a prominence regime. We enquired what form such supervision and enforcement should take, and which actor(s) should be tasked with these functions. Most stakeholders agreed that measures should be ‘principle-based’, referring to the different types of UIs and devices. This approach avoids the impracticality of highly detailed and specific regulations tailored to each individual addressee. Secondly, most stakeholders seem to agree on the need to keep measures ‘flexible’, as measures need to evolve at a similar rate as the continuously developing UIs of smart devices. In this context, the PSM advocated for ‘adequate consultation with the sector to ensure that practical input and developments can be discussed in a timely manner’ (written stakeholder consultation). Players in favor of prominence regimes also put the burden of proof of legal compliance on the addressees. The prominence proponents stated that addressees ought to report on how they ensure prominence for beneficiaries. This point was also raised by the regional broadcasters and the Flemish Media Regulator in our consultation, as the complexity and diversity of interventions to ensure findability and visibility is highly difficult to trace as an independent regulator.

On the side of the market intervention coalition there is no entirely unified view on what supervision of prominence regulation should look like. Most players (PSM, the larger commercial broadcasters, smaller thematic channels, and one television distributor) propose a system in which the media regulator oversees compliance with prominence measures outlined by the government. The other distributor, alongside the other thematic broadcaster, consider self-regulation the best form of supervision, provided that a regulator can step in and mediate when conflicts arise. The regional broadcasters, together with the PSM, would rather like to see a system of self-regulation, but with transparency requirements relating to the recommendation algorithms employed by the addressees of the prominence regulations. In the market freedom coalition, there is also no single unified stance on how to address this matter. One large smart TV manufacturer, together with the international distributor deemed self-regulation the best form of legal enforcement. A smaller smart TV manufacturer commented to be in favor of a self-regulatory system with a regulator that can step in to mediate, referring to the same type of co-regulation as some of the prominence regime proponents.

Discussion

This study presented the perspectives of a varied group of stakeholders on the revision of Flemish local policy on appropriate prominence, visibility and findability for audiovisual and auditive media SGIs, following the transposition of Article 7a of the AVMSD (European Union, 2018a). Our inquiry gives insight into the stakeholders’ views on desirability and feasibility, considerations to be made when developing prominence regulation, and presents lessons to be learned beyond the Flemish case. The results of the consultation are part of a large-scale study assessing the feasibility and desirability of prominence regulation in Flanders.

This research was based on a snapshot of input collected between February and June 2024 and is based on those viewpoints submitted to the consultation or those of the experts selected and available for interviews. Thus, the research cannot encapsulate amended and deepened argumentations, as legal, market and technical knowledge within media players’ strategy departments also progresses as more Member States start imposing measures. This study did not include the audience as a stakeholder, as we felt the perspective of audiences warrants a separate more dedicated focus. Research of Lobato et al. (2023), amongst others, support the need for intervention based on audience research demonstrating the lack of knowledge and understanding of audiences on how smart device UIs affect visibility and findability of content and services.

The research identified two opposing stakeholder coalitions: one advocating for the implementation of prominence obligations and the other opposing such measures. The former comprises all the domestic broadcasters, and the latter consists of foreign businesses without a direct link to (Flemish) broadcasting. Positioned in between these two broad groups are stakeholders who typically do not support regulatory intervention, as it may impose additional obligations on them. However, they also acknowledge a perceived imbalance in the competitive landscape, particularly between global streaming services, technology platforms, and hardware manufacturers on one side, and local market players on the other. Their concerns align with broader debates on the lack of a level playing field in areas such as advertising regulations, or obligations related to the promotion of European works.

Most diverging opinions within this stakeholder group related to defining which players should be considered to be of ‘general interest’ and, additionally, which criteria the government should use to categorize players. That the three larger broadcasters—including purely commercial players of which one is a full subsidiary of an internationally owned media conglomerate—have formed a strategic alliance on the matter, corresponds with earlier findings showing the specificity of the Flemish market context. This context has traditionally been characterized by an ‘ecosystem’ logic in market discourse and policy approaches (Raats, 2023) that aims to protect all players investing significantly in domestic original content. At the same time, it shows that this ecosystem logic does not extend to smaller, admittedly, much less popular, regional or thematic broadcasters, who struggle to secure sufficient revenue. This issue is likely to become even more pressing in the coming years.

Opposition to prominence rules is often motivated by several arguments. First, the market context: critics contend that the Flemish market is too small and complex to justify the customization of UIs and hardware devices. Second, the legal context: stakeholders highlight legal ambiguities and potential conflicts between Article 7a of the AVMSD and existing EU legislation, particularly the e-Commerce Directive (specifically, the country-of-origin principle) and the ECC (which includes provisions on must-carry obligations and EPGs). With a potential review of the AVMSD on the horizon, it is essential that the Commission provides clear guidelines to ensure coherence between Article 7a, internal market regulations, and EMFA. Third, the technological context: UI providers and hardware manufacturers argue that compliance with certain regulatory requirements may be technically unfeasible or could hinder innovation in UI design. Fourth, the audience interests: there are concerns that prominence rules could conflict with audience preferences and expectations. Fifth, the financial considerations: opponents also emphasize the financial burden associated with implementing prominence obligations on UIs and devices, an argument that resonates with policymakers wary of potential price increases for consumers. Additionally, critics call for empirical evidence demonstrating the necessity of prominence regulations. For policymakers assessing the feasibility and desirability of due prominence obligations, it is crucial to incorporate audience perspectives, to gather data on challenges in accessing general interest content, and to establish a regulatory framework that allows for flexible adaptations. Such an approach would enable timely responses to evolving market conditions and mitigate any unforeseen consequences of new obligations.

Our research further highlights the challenges of translating prominence obligations into clearly measurable and enforceable interventions, as well as the difficulties regulators face in assessing whether and how designated entities comply with these requirements. This is especially difficult considering the personalized nature of media consumption, which results in UIs varying across consumers and interventions related to search or audio recommendations which are simply not traceable. In this context, prominence measures reflect a broader trend in digital media policy, wherein large technology companies—and, in this case, hardware manufacturers—are increasingly subjected to European regulatory obligations. However, the burden of proof and transparency largely remains with regulated entities themselves. Regulators often lack the necessary tools and expertise to systematically assess compliance, while media devices and services frequently operate with limited transparency, making regulatory oversight more difficult (Helberger, 2019, p. 1004). The lack of knowledge regarding the actual impact of hardware and UI manipulations—combined with the technical complexity of these systems—has emerged as a significant obstacle to policy development, particularly for non-technical stakeholders involved in the regulatory process.

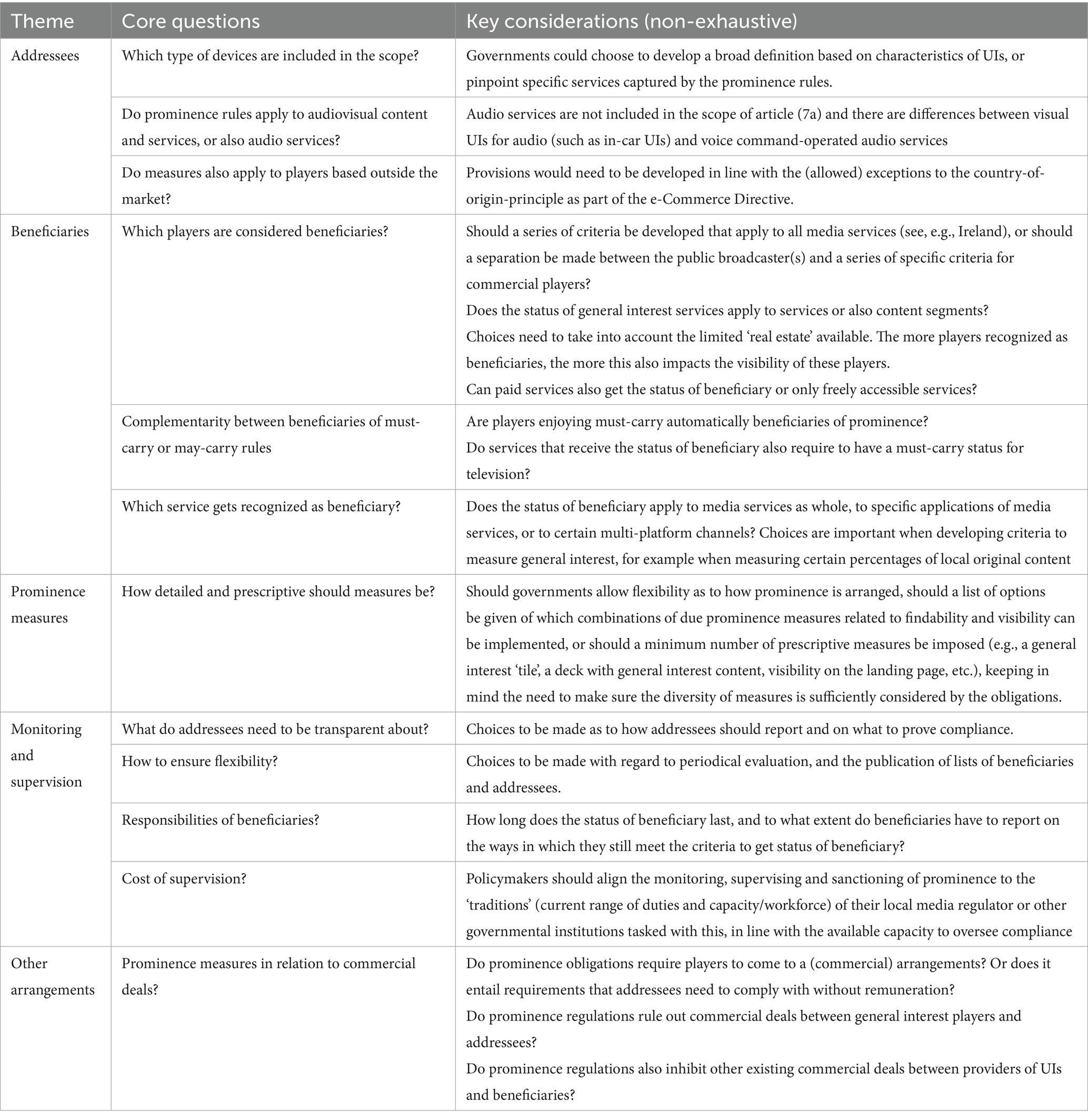

Additionally, our inquiry of different viewpoints and argumentations of stakeholders also shows differences in how key policy considerations such as ‘general interest’, ‘public value’, ‘level-playing field’ or ‘self-regulation’ or even ‘principle-based policies’ are interpreted across the stakeholders. Each of these interpretations are shaped by the stakeholders’ own respective interests and market contexts. Eventually, self-interest was the most dominant guiding logic amongst all stakeholders, and the aforementioned concepts mainly serve this opportunistic stance. In those cases where self-interest is transcended, stakeholders’ positions often reflect strategic considerations aimed at increasing the likelihood that their own interests are ultimately served. For example, commercial broadcasters advocating for recognition as ‘general interest’ services would be quite unlikely if PSM were not, ad minimum, afforded the same status. Based on the consultation, several considerations for policymakers can be made for policymakers in the development of prominence regulations. An overview of key considerations and related core questions can be found in Table 2. These insights may also serve as a valuable reference for researchers, policymakers, and regulators involved in future regulatory frameworks on prominence.

This research demonstrates that despite efforts to ground media policy in broad stakeholder consensus, the designation of both the addressees and beneficiaries of prominence measures ultimately remains a political decision, and multistakeholderism does not necessarily allow decisions are based on shared consensus amongst stakeholders. This decision should be guided by a well-defined rationale and developed with careful consideration to the regulatory and market developments in other jurisdictions. Through this study, we have sought to contribute to the formulation of such a rationale, recognizing that the interests of various stakeholders often align across different countries. Key directions for future research include examining how Article 7a of the AVMSD is implemented across EU markets to ensure compliance with internal market rules. Additionally, further research should explore methodologies for assessing the impact—or lack thereof—of prominence measures across different market contexts. Lastly, legal analysis is needed to clarify the interplay between Article 20 of the EMFA, Article 7a of the AVMSD, and Article 3 of the e-Commerce Directive, and to assess how these interactions influence Member States’ decisions to impose prominence measures, as well as the Commission’s role in evaluating or contesting such measures.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

PE: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TR: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This contribution presents results from data collected as part of a research project funded by the Minister of Media and Department of Culture, Youth and Media in Flanders (CJM).

Acknowledgments

The researchers wish to thank all stakeholders and experts for sharing their views, and reviewers and the advisors of the Minister of Media as well as the Department of Culture, Youth and Media in Flanders (CJM) for their trust, and expertise and ensuring the editorial independence in which this study was conducted.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The LLM ChatGPT was used as a writing aid for this article, primarily to refine vocabulary and sentence structure.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Afilipoaie, A., Iordache, C., and Raats, T. (2021). The ‘Netflix original’ and what it means for the production of European television content. Crit. Stud. Telev. 16, 304–325. doi: 10.1177/17496020211023318

Broughton Micova, S. (2019). “Case study research” in The palgrave handbook of methods for media policy research. eds. H. Van den Bulck, M. Puppis, K. Donders, and L. Van Audenhove (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 71–84.

Bruun, H., Johnson, C., Münter Lassen, J., Nucci, A., Raats, T., and Switkowski, F. (2025). Publishing public service media on demand: a comparative study of public service media companies’ editorial practices on their VoD services in the age of platformization. J. Digit. Media Policy. doi: 10.1386/jdmp_00167_1

Cappello, M. (2022). Prominence of European works and of services of general interest. IRIS Special. Strasbourg: European Audiovisual Observatory. Available online at: https://rm.coe.int/iris-special-2022-2en-prominence-of-european-works/1680aa81dc (Accessed April 25, 2024).

Clover, J. (2024). TV manufacturers selling sets at a loss for advertising rewards. BroadbandTVNews, 18 November. Available online at: https://www.broadbandtvnews.com/2024/11/18/tv-companies-selling-sets-at-a-loss-for-advertising-rewards/ (Accessed January 24, 2025).

De Marez, L., Sevenhant, R., Denecker, F., Georges, A., Wuyts, G., and Schuurman, D. (2024). Imec.digimeter.2023. Digitale trends in Vlaanderen. Ghent: Imec. Available online at: https://www.imec.be/sites/default/files/2024-03/imec%20digimeter%202023%20Rapport.pdf (Accessed October 21, 2024).

Delaplace, F., Lodewyckx, D., and Bronselaer, J. (2024). Gezamenlijk memorandum van de drie Vlaamse omroepen. Available online at: https://www.mediaspecs.be/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Gezamenlijk-memorandum-van-de-drie-Vlaamse-omroepen.pdf (Accessed October 28, 2024).

Desjardins, D. (2016). Discoverability: toward a common frame of reference. Canada Media Fund. Available online at: https://cmf-fmc.ca/now-next/research-reports/discoverability-part-2-the-audience-journey/ (Accessed May 18, 2025).

Die Medienanstalten. (2020). Interstate Media Treaty (Medienstaatsvertrag). Available online at: https://www.die-medienanstalten.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Rechtsgrundlagen/Gesetze_Staatsvertraege/Interstate_Media_Treaty_en.pdf (Accessed October 29, 2024).

Donders, K., and Evens, T. (2014). Government intervention in marriages of convenience between TV broadcasters and distributors. Javn. - Public 21, 93–110. doi: 10.1080/13183222.2014.11009147

Donders, K., Van den Bulck, H., and Raats, T. (2019). The politics of pleasing: a critical analysis of multistakeholderism in public service media policies in Flanders. Media Cult. Soc. 41, 347–366. doi: 10.1177/0163443718782004

European Broadcasting Union (2024) Connected TV landscape 2024. Available online at: https://www.ebu.ch/files/live/sites/ebu/files/Publications/MIS/members_only/market_insights/EBU-MIS-Connected_TV_Landscape_2024.pdf (Accessed January 29, 2025).

European Commission. Parcu, P. L., Brogi, E., and Verza, S. (2022). Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology Centre on Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) CiTiP (Centre for Information Technology and Intellectual Property) of KU Leuven Institute for Information Law of the University of Amsterdam (IViR/UvA) Vrije Universiteit Brussels (Studies in Media Innovation and Technology VUB- SMIT), Study on media plurality and diversity online: Final report Publications Office of the European Union.

European Union (2000). Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the council of 8 June 2000 on certain legal aspects of information society services, in particular electronic commerce, in the internal market (E-commerce directive). Official Journal of the European Union, L178, 17.7.2000, pp. 1—16. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/31/oj/eng (Accessed January 29, 2025).

European Union (2015). Directive (EU) 2015/1535 of the European Parliament and of the council of 9 September 2015 laying down a procedure for the provision of information in the field of technical regulations and of rules on information society services. Official Journal of the European Union, L241, 17.9.2015, pp. 1—15. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2015/1535/oj/eng (Accessed January 29, 2025).

European Union (2018a). Directive (EU) 2018/1808 of the European Parliament and of the council of 14 November 2018 amending directive 2010/13/EU on the coordination of certain provisions laid down by law, regulation or administrative action in member states concerning the provision of audiovisual media services (audiovisual media services directive) in view of changing market realities. Official Journal of the European Union, L303, 28.11.2018, pp. 69—92. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2018/1808/oj (Accessed: 29 January 2025).

European Union (2018b). Directive (EU) 2018/1972 of the European parliament and of the council of 11 December 2018 establishing the European electronic communications code (recast). Official Journal of the European Union, L321, 17.12.2018, pp. 36—214. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32018L1972 (Accessed January 29,2025).

European Union (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1083 of the European Parliament and of the council of 11 April 2024 on the transparency and targeting of political advertising and amending regulations (EU) 2016/679 and (EU) 2018/1725. Official Journal of the European Union, L202, 18.4.2024, pp. 1—32. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1083/oj/eng (Accessed January 29, 2025).

Eurostat. (2023). Growing importance of internet-connected devices. Eurostat, 29 August, Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20230829-1 (Accessed January 24, 2025).

Evens, T., and Donders, K. (2018). Platform power and policy in transforming television markets. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Flew, T., and Lim, T. (2019). “Assessing policy I: stakeholder analysis” in The palgrave handbook of methods for media policy research. eds. H. Van den Bulck, M. Puppis, K. Donders, and L. Van Audenhove (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 541–555.

Freedman, D. (2014). Media policy research and the media industries. Media Ind. J. 1:103. doi: 10.3998/mij.15031809.0001.103

Garcia Leiva, M. T. (2024). Audiovisual prominence and discoverability in Europe: stakeholders’ alliances under construction. Convergence 1, 1–18. doi: 10.1177/13548565241260490

Garcia Leiva, M. T., and Mazzoli, E. M. (2023). “Safeguarding the visibility of European audiovisual services online: an analysis of the new prominence and discoverability rules” in European audiovisual policy in transition. eds. H. Ranaivoson, S. Broughton Micova, and T. Raats (Routledge), 198–217.

Gillespie, T. (2014) ‘The relevance of algorithms’, In Gillespie, T., Boczkowski, P., and Foot, K. (eds.) Media technologies, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Government of Ireland (2022) Online safety and media regulation act 2022. Available online at: https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2022/act/41/enacted/en/print#sec40 (Accessed December 11, 2024).

Granryd, T. (2024). EBU connected Car playbook. Available online at: https://tech.ebu.ch/files/live/sites/tech/files/shared/other/EBU_ConnectedCar_Playbook.pdf (Accessed October 12, 2024).

Helberger, N. (2019). On the democratic role of news recommenders. Digit. Journal. 7, 993–1012. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2019.1623700

Hesmondhalgh, D., and Lotz, A. D. (2020). Video screen interfaces as new sites of media circulation power. Int. J. Commun. 14, 386–409.

Hildén, J. (2022). The public service approach to recommender systems: filtering to cultivate. Telev. New Media 23, 777–796. doi: 10.1177/15274764211020106

Johnson, C. (2020). The appisation of television: TV apps, discoverability and the software, device and platform ecologies of the internet era. Crit. Stud. Telev. 15, 165–182. doi: 10.1177/1749602020911823

Johnson, C., Hills, M., and Dempsey, L. (2023). An audience studies’ contribution to the discoverability and prominence debate: seeking UK TV audiences “routes to content”. Convergence 30, 1625–1645. doi: 10.1177/13548565231222605

Kostovska, I., Komorowski, M., Raats, T., and Tintel, S. (2023). ““Netflix taxes” as tools for supporting European audiovisual ecosystems: policy interventions for rights retention by independent producers” in European audiovisual policy in transition. eds. H. Ranaivoson, S. Broughton Micova, and T. Raats (Routledge), 157–176.

Krämer, N. J., and Schnurr, N. D. (2018). Is there a need for platform neutrality regulation in the EU? Telecommun. Policy 42, 514–529. doi: 10.1016/j.telpol.2018.06.004

Krieger, (2024). German media authorities extend regulation to in-car entertainment, BroadbandTVNews, 3 April. Available online at: https://www.broadbandtvnews.com/2024/04/03/german-media-authorities-extend-regulation-to-in-car-entertainment/ (Accessed January 29, 2025).

Ledger, M. (2023). Towards coherent rules on the prominence of media content on online platforms and digital services. Namur: CERRE. Available online at: https://cerre.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/CERRE_Prominence-of-Media-Content_Issue-Paper.pdf (Accessed October 28, 2024).

Lobato, R., Scarlata, A., and Schivinski, B. (2023). Smart TVs and local content prominence a submission to the prominence framework for connected TV devices proposals paper. Melbourne: RMIT University/ADM+S. Available online at: https://www.infrastructure.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/pfpp--associate-professor-ramon-lobato-alexa-scarlata-bruno-schivinski-rmit-university.pdf (Accessed April 24, 2024).

Lobato, R., Scarlata, A., and Schivinski, B. (2024). Smart TV users and interfaces: who’s in control? Int. J. Commun. 18, 4813–4833.

Lobato, R., Scarlata, A., and Wils, T. (2024). Video-on-demand catalog and interface analysis: the state of research methods. Convergence 30, 1331–1347. doi: 10.1177/13548565241261992

Mazzoli, E.M., and Tambini, D. (2020). PRIORITISATION uncovered the discoverability of public interest content online. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Available online at: https://rm.coe.int/publication-content-prioritisation-report/1680a07a57 (Accessed December 17, 2024).

McKelvey, F., and Hunt, R. (2019). Discoverability: toward a definition of content discovery through platforms. Soc. Media Soc. 5:9188. doi: 10.1177/2056305118819188

MPRT. (2023). Redovisning av uppdrag om vidaresändningsplikt och framhävande av innehåll av allmänt intresse. Stockholm: MPRT. Available online at: https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/fe8320960b8141d7be94b9524b695ad4/redovisning-av-uppdrag-om-vidaresandningsplikt-och-framhavande-av-innehall-av-allmant-intresse.pdf (Accessed December 17, 2024).

Ofcom. (2025). Media act implementation. Available online at: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/tv-radio-and-on-demand/Media-Act-Implementation/ (Accessed January 27, 2025).

Raats, T. (2023). “Public service media caught between public and market objectives: the case of the “Flemish Netflix”” in Public service media’s contribution to society: RIPE@2021. eds. M. Puppis and C. Ali (Gothenburg: Nordicom, University of Gothenburg), 111–130.

Raats, T., Afilipoaie, A., Van der Elst, P., and Forest, N. (2025). Studie omtrent passende aandacht, zichtbaarheid en vindbaarheid voor audiovisuele en auditieve mediadiensten van algemeen belang in Vlaanderen. Onderzoek in opdracht van het Departement Cultuur, Jeugd, Media en de Minister van Media. Brussels: imec-SMIT-VUB.

Ranaivoson, H., and Domazetovikj, N. (2023). Platforms and exposure diversity: towards a framework to assess policies to promote exposure diversity. Media Commun. 11, 379–391. doi: 10.17645/mac.v11i2.6401

Rozgonyi, K. (2023). Accountability and platforms' governance: the case of online prominence of public service media content. Internet Pol. Rev. 12:1723. doi: 10.14763/2023.4.1723

Salganik, R., Wiratama, V., Afilipoaie, A., and Ranaivoson, H. (2024). Navigating discoverability in the digital era: a theoretical framework, MuRS 2024: 2nd Music Recommender Systems Workshop, Bari, Italy, 14 October. Available online at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2410.09917 (accessed January 8th, 2025).

Samsung. (2024). Samsung TV Plus. Available online at: https://www.samsung.com/be/smart-tv/samsung-tv-plus/ (Accessed December 17, 2024).

Statista. (2024) Smart streaming devices—Europe. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/consumer-electronics/tv-peripheral-devices/smart-streaming-devices/europe (Accessed January 24, 2025).

Steen-Johnsen, K., Sundet, V. S., and Enjolras, B. (2019). Theorizing policy-industry processes: a media policy field approach. Eur. J. Commun. 34, 190–204. doi: 10.1177/0267323119830047

UK Government (2024). Media Act 2024. Available online at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2024/15/contents (Accessed January 29, 2025).

Van den Bulck, H. (2019). “Analyzing policy-making I: stakeholder and advocacy coalition framework analysis” in The palgrave handbook of methods for media policy research. eds. H. Van den Bulck, M. Puppis, K. Donders, and L. Van Audenhove (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan).

Vandaele, W., Coudyser, C., Meremans, M., Pardaens, F., Van Werde, M., and Gryffroy, A. (2024). Conceptnota voor nieuwe regelgeving over de vind- en zichtbaarheid van Vlaamse omroepdiensten. Vlaams Parlement. Available online at: https://docs.vlaamsparlement.be/pfile?id=2050539 (Accessed October 28, 2024).

Vannieuwenhuyze, J., Donders, K., and Picone, I. (2021). Zie ik het of zie ik het niet? Een onderzoek naar de impact van plaatsing op de consumptie van programma’s in een on-demand-omgeving. Tijdschr. Communiewet. 49, 51–83. doi: 10.5117/TCW2021.01.004.VANN