- School of English and International Studies, Beijing Foreign Studies University, Beijing, China

Translation plays a crucial role in the global communication and dissemination of Buddhism, and English Base for Buddhist Exchange (EBBE)'s recent translation of the Platform Sutra of the Six Patriarch was a new contribution to the existing versions. This paper adopts Lefevere's theoretical perspectives to address the following research questions: (1) Has EBBE's translation of the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch fulfilled its stated translation philosophy? If so, how? (2) What are the potential communicative effects of the EBBE's version? (3) What are some problems in this translation to be addressed in the future? This paper used stratified sampling of three main narrative types across five different versions of the translation of the Platform Sutra, namely EBBE, Shi Chengguan, Huang Maolin, the Buddhist Text Translation Society, and John McRae, and compare them in terms of terminology translation, appraisal resources, thematic progression and Flesch Reading Ease. It is found that EBBE's version does stand out in readability and accessibility in the examined aspects, though certain improvement may still be possible. And an analysis based on Lefevere's theory was conducted for an understanding of the translation philosophy adopted in this latest translation.

1 Introduction

Translation plays a crucial role in the global communication and dissemination of Buddhism, one of the world's major religions that relies heavily on both oral traditions and texts to convey its teachings. Translating religious texts is a complex endeavor that extends beyond mere linguistic conversion which involves navigating profound cultural, spiritual, and ideological nuances (Ibrahim, 2019). Translators must balance fidelity to the source text with the need to render the content accessible and meaningful to the target audience (Abdo and Mousa, 2019; Pei, 2010). This challenge is particularly pronounced when dealing with untranslatable elements and sacred concepts that carry significant ethical implications for cross-cultural understanding (Bergdahl, 2009; Benjamin, 1968). This is especially true for the translation of Buddhist texts, where preserving spiritual heritage and wisdom transcends linguistic conversion. Through dedicated translation efforts, the profound insights of Buddhism become accessible to a diverse global audience, promoting the spread of Buddhism teachings.

Among the extensive corpus of Buddhist literature, the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch holds a special place in Chinese Buddhism, particularly within the Chan tradition (Wang, 2023, p. 6). Attributed to the Sixth Patriarch Huineng, it is unique as the only Chinese-authored text classified as a “sutra,” a term traditionally reserved for teachings directly from the Buddha. This distinction underscores its significance and the central role it plays in conveying the principles of Chan Buddhism.

Despite the existence of more than 30 translations by 2022 (Wang, 2023, p. 2), it remains important to continue translating different versions of the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch. Language evolves over time, as do interpretations and understandings of spiritual texts (Ren and Gao, 2017). New translations can offer fresh perspectives, making the teachings more accessible to contemporary readers and bridging cultural and linguistic gaps (Mingsheng, 2024). Each translation provides a unique lens through which the teachings can be understood, enriching global comprehension of the sutra and allowing for a multifaceted exploration of its teachings.

Recently, the English Base for Buddhist Exchange (EBBE), affiliated with the Buddhist Association of China, undertook a new translation of the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch, adding a contribution to the existing translations. Established in 2017 at Zhuhai Putuo Temple in Guangdong Province, China, EBBE aims to promote cultural exchanges and enhance cultural confidence by inheriting and advancing fine traditional Chinese culture (Mingsheng, 2024). The translation by EBBE is distinguished by two key factors. First, it was completed at Guangzhou Guangxiao Temple, dating back to the Western Han Dynasty and considered the ancestral court of Chan Buddhism, where Huineng the Six Patriarch was ordained and preached. The location of the translation imparts special significance to the EBBE version, connecting it directly to the spiritual and historical roots of the sutra. Completing the translation at this sacred site marks a meaningful milestone in the history of Chinese Buddhism, as Huineng's legacy is translated and disseminated worldwide from its place of origin (Mingsheng, 2024). Second, it embraces a distinctive translation philosophy, as articulated by Most Venerable Mingsheng, Abbot of Zhuhai Putuo Temple and Guangzhou Guangxiao Temple, and leader of EBBE: “We value this text more for its wide circulation rather than its research value. Although translation is a craft performed on the linguistic level, in this case, a literal and strictly academic translation will erode the spirit of Chan and end up on the desk, collecting dust. Using daily expressions to preserve as much as possible the oral and stylistic nuances of Chan discourse, this translation tries to ‘retain the spirit and forsake the form.' In addition, we try to use the original Buddhist terms as much as possible, instead of applying Western philosophical concepts to approximate Chan thought. In translating Buddhist verses, plain sentences were used, which might impair the rhyme inherent in classical Chinese. But this option is justified by the differences between the Chinese and English languages as well as the essence of Chan Buddhism” (Mingsheng, 2024). As the purpose of this translation is to make the teachings accessible to a global audience in a way that honors their original essence, it potentially contributes to the further spread of Chan teachings and enriches the understanding of Chinese Buddhism worldwide.

Translation of Buddhist texts is also part of the broader phenomenon of translation, adhering to its inherent laws and patterns. Since there are multiple translations of this sutra from different periods, it is appropriate to approach it through the lens of Lefevere's (2004) theory. Lefevere, a prominent figure who contributed to the “cultural turn” in translation studies, posited that translation is not merely a linguistic transfer but a culturally and ideologically loaded act of “rewriting” that is shaped by literature and society.

This paper adopts Lefevere's theoretical perspectives to address the following research questions: (1) Has EBBE's translation of the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch fulfilled its stated translation philosophy? If so, how? (2) What are the potential communicative effects of the EBBE's version? (3) What are some problems in this translation to be addressed in the future?

2 Literature review

To address the research questions, this paper will explore prior research in the following key areas: the translation of religious texts, the translation of Buddhist texts, the translation of the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch, and the communicative effects of translating Chinese texts, of which the Platform Sutra is a part.

2.1 Translation of religious texts

Translation of religious texts is the rendering or the process of rendering sacred texts into another language while preserving their doctrinal integrity, cultural context, and spiritual essence. As the sacred nature of the texts, it is considered one of the most challenging forms of translation to maintain the meaning of the text without distortion, requiring translators to reproduce aspects beyond the literal content and to convey the “unfathomable” and “mysterious” elements that transcend mere information (Ibrahim, 2019; Benjamin, 1968). Translators of this kind of texts face significant challenges in balancing fidelity to the sacred source texts with the need for accessibility and relevance to the target audience. Strategies such as domestication and foreignization, as well as text-oriented and reader-oriented approaches, highlight the tension between preserving original meanings and adapting to cultural contexts, while some may seemed to be untranslatable (Abdo and Mousa, 2019; Goodrich, 2014; Bergdahl, 2009).

One of the best-known scholar for religious texts translation is Eugene Nida, who proposed the idea—though not the exact wording—of the theory of Dynamic Equivalence for the first time in his work Principles of Translation as Exemplified by Bible Translation (Nida, 1959a), which emphasized that translators as receptors of the source text and message sender of the target text, should make sure that the readers of the translated texts should have similar reactions to the source text readers. He then proposed Dynamic Equivalence (Nida, 1959b) and further revised that to Functional Equivalence (Nida, 1993). Despite its evolution, his theories all along focused heavily on readers' response (Dun, 2018). While it is fair to say that readers' response should always be the key and core of religious texts translation, it should be noted that religious translation, as a socially-embedded practice, is not only strongly influenced by cultural, ideological, and sociological factors (Abdo and Mousa, 2019; Shih, 2016; Pei, 2010; Hung, 1999), an aspect that should be given more attention by scholarship in religious translation studies. The influence of ideology, patronage, and translator subjectivity emerges as critical in shaping translation choices and outcomes (Berneking, 2016; Pei, 2010). The present study employs Lefevere's (2004) tripartite framework (ideology, patronage, and poetics) to analyze translation choices—a gap in religious translation research.

2.2 Translation of Buddhist texts

Buddhism translation bears historical significance, starting in China as early as the 2nd century (Saito, 2017). During the long history of Buddhism translation, many translators grappled with integrating diverse sources and refining translations (Li, 2023). There is not a lack of theoretical discussions on its translation strategies, for instance, Xuanzang's adherence to the principles of “正翻” (transliteration) and “义翻” (translation of meaning) and the “method of transliteration in five situations,” (五不翻) suggesting that certain terms should be transliterated to preserve the original meanings, especially when they refer to concepts unique to Buddhism (Tao, 2016; Wang, 2022). By choosing not to translate certain key terms, Xuanzang preserved the original meanings and nuances of complex philosophical ideas, which influenced how doctrines were interpreted.

Xuanzang's translation philosophy is a well-known representative of many efforts of striving to balance textual fidelity with contextual relevance, while translators would choose different strategies, either foreignization strategy to preserve the foreign elements within the target language, such as “Buddha,” “bodhisattva,” or “nirvana” to maintain the original cultural and philosophical nuances of the source text maintaining the original cultural and philosophical nuances of the source text (Saito, 2017) or to substitute the Buddhist concepts with Daoism or Christian concepts already existing in the target language culture (Gong, 2017; Saito, 2017). These choices have their respective influence on the understanding and reception of target readers. And similar to all other religious texts, the translation of Buddhist texts is also subject to the influence of patronage, ideology and poetics (Chen and Zhang, 2006). While in-depth analysis on translation strategies exist in Buddhism translations, methodological limitations persist in that some studies analyzed strategies descriptively but lack theoretical framing to explain the translation choice. The present study applies Lefevere's framework to EBBE's Platform Sutra translation, examining strategies used from theoretical perspectives—an approach to be adopted more by Buddhist text analyses.

2.3 Translation of the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch

The Platform Sutra is an important Buddhism text and has been translated into many different version, and proliferation demonstrates the cultural value and ideological charm of this classic, recognized by Western scholars and readers (Zhou and Zhang, 2023). The various translations of the Platform Sutra have significantly contributed to the spread of Chan Buddhism in the English-speaking world. By adapting to different cultural contexts and audiences, these translations have enabled the teachings of Chan Buddhism to transcend linguistic barriers and foster a greater global understanding of its philosophies. The translation and introduction of the Platform Sutra in the English-speaking world have gone through four stages: popularization, academic translation, localization, and diversification (Xiong and An, 2021).

Many scholars have done research on the translation strategies and methodologies related to this text, provide insights into different translation approaches (Qing, 2021; Long, 2021; Huang, 2019; Yang, 2023; Ma, 2016; Huang, 2007; Yu and Wu, 2018). Translators' strategies were analyzed, for instance, Wing-tsit Chan prefers to minimize transliterations, opting instead for translations even if they are not entirely satisfactory (Long, 2021). McRae, as a Western sinologist, carefully considers the cultural backgrounds of both source and target audiences. By sometimes opting for transliteration, he preserves the original terms' cultural significance; at other times, he employs free translation to reduce reading difficulties, thereby achieving sociopragmatic equivalence. He also adopted a deep translation strategy that includes extensive in-text annotations and avoids excessive clarification to maintain the profoundness of the original text (Yang, 2023; Huang, 2019).

The reception and interpretation of the Platform Sutra translations vary across communities, influenced by translators' backgrounds, intentions, and strategies (Yu, 2016; Chang and Li, 2019). Academic readers value translations that offer rigorous scholarship, while religious communities may focus on translations that align with their beliefs. The differing approaches in translations contribute to the diverse understandings of the Platform Sutra among its readers.

Though many studies contribute significantly to the studies on the translation of the Platform Sutra, there is a lack of empirical research for the translation effects of the Platform Sutra, an effort this present studies attempt to make.

2.4 Communication and effects of translations of Chinese texts

The communication and reception of Chinese classics translations have attracted considerable scholarly attention, as these works are pivotal in cultural exchange between China and the rest of the world. Researchers have explored various aspects of how Chinese classics are translated and received abroad, emphasizing the strategies employed by translators and the factors influencing acceptance by foreign audiences. Firstly, reader awareness is considered essential in the overseas translation and publication of Chinese literary classics (Zhu and Qin, 2022; Zhong, 2011). Secondly, balancing defamiliarization and readability is crucial for the reception of translated works. By adjusting the translation to meet the aesthetic habits and cognitive abilities of Western readers, translators can better convey the original's power and beauty (Wu, 2012; Liu, 2019). Thirdly, progressive acceptance of Chinese classics through successive translations will help with a deeper international understanding of Chinese history and culture, thereby better reader acceptance (Wei, 2021).

2.5 Research gaps and necessity of the present study

Despite extensive research on the translation of religious texts, Buddhist scriptures in general and the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch in particular, gaps remain in the literature regarding the application of contemporary translation theories and the investigation of actual and potential communication effects.

Firstly, despite many studies on the translation theory and practice of Buddhism texts in general and the Platform Sutra in particular, there is a lack of using systematic descriptive framework for the interpretation of translation strategies of Buddhist texts. There seems to be a fissure between traditional Buddhism translation theories with systematic descriptive framework. Therefore, applying Lefevere's (2004) theory of translation as rewriting—which encompasses the concepts of ideology, patronage, and poetics—may offer valuable insights into how external factors shape translations, a perspective that remains underexplored in the context of the translations of the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch. Understanding how these factors influence translation strategies and choices can shed light on EBBE's translation and how it the modern theoretical perspectives can possibly explain its translation strategy.

Secondly, there is a significant lack of empirical research on the actual and potential communication effects of translations of the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch. Despite the abundance of English translations, there is a significant gap of critical evaluations of these contemporary translations, hindering the identification of areas needing improvement. This gap limits the accurate transmission of Buddhist teachings to English-speaking audiences.

Understanding communication effects involves investigating factors such as readability, cultural accessibility, and the resonance of philosophical concepts with foreign audiences. Assessing how translation strategies impact comprehension, appreciation, and the overall communicative effectiveness of the text is crucial.

Therefore, research is necessary that not only applies Lefevere's theoretical framework to analyze the translation strategies employed in EBBE's version of the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch but also examines the potential communication effects among its target audience. This dual focus can uncover how ideological, cultural, and aesthetic factors influence both the translation process and its effectiveness in communication.

By assessing whether the translation aligns with its stated philosophy and how it may be received by its target audience, the research will contribute to a deeper understanding of translation strategies for religious texts and support the effective cross-cultural communication of Buddhist teachings.

This integrated approach addresses the necessity of considering both theoretical and practical aspects of translation. It recognizes that successful translation is determined not only by the strategies employed but also by potentially how well the translation resonates with readers and facilitates understanding across cultural boundaries. The findings have potential implications for translators, scholars, and practitioners in the field of translation studies, particularly concerning religious and philosophical texts.

3 Theoretical framework: André Lefevere's theory of translation

Lefevere (2004) provides a critical framework for understanding translation as a culturally and ideologically charged act of “rewriting.” His theory emphasizes that translations are shaped by three main factors: ideology, patronage, and poetics. This framework is relevant for analyzing translations of religious texts, such as the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch, as it illuminates how external influences can impact the translation process and the translated text.

3.1 Translation as rewriting

Lefevere posits that translation is not a neutral transfer of content but an act of rewriting that reflects the translator's interpretation within the cultural and ideological context of the target language. This process influences literary canons and societal perceptions, highlighting the translator's active role adapting to and shaping the literary culture. By selecting certain meanings over others, translators may alter how a text is perceived, potentially redefining its significance within the target culture.

3.2 Ideology

Ideology operates on both societal and individual levels. Societal ideology dictates what is deemed acceptable within the target culture, influencing which texts are selected for translation and how they are adapted (Hermans, 2004, p. 75; Chesterman, 2012, p. 64). Translators' personal ideologies also affect their choices, and their beliefs, values, and biases can consciously or unconsciously shape the translation (Venuti, 2008, p. 136–137). Ideological shifts may lead to adaptations that align the text with dominant cultural narratives or suppress elements that conflict with prevailing norms, thereby influencing the reader's interpretation and understanding.

3.3 Patronage

Patronage refers to the powers that control the translation process through economic support, political influence, and the ability to confer prestige (Lefevere, 2004, p. 15–16). Patrons can include governments, religious organizations, publishers, or other institutions that determine which texts are translated and disseminated. Their agendas significantly affect the content and reception of translations, often aligning them with specific ideological goals (Shih, 2016). Patronage can thus shape not only the selection of texts but also the manner in which they are presented to the target audience.

3.4 Poetics

Poetics encompasses the literary conventions, aesthetic norms, and stylistic expectations of the target culture (Lefevere, 2004, p. 26–28). Translators must consider these factors to produce translations that are acceptable and appealing to their audience. This may involve adapting the source text's style, structure, or content to align with the target culture's literary traditions, potentially leading to significant deviations from the original. Such adaptations can enhance readability and resonance but may also alter the text's inherent qualities.

3.5 Application of Lefevere's theory to the translation of religious texts

In the context of religious texts, Lefevere's theory illuminates how translations are influenced by ideological considerations, power structures, and cultural aesthetics (Alvarez, 1996). Translators may consciously or unconsciously modify texts to align with dominant ideologies or satisfy the demands of patronage, affecting both the authenticity and reception of the translation (Baker and Saldanha, 2020). For example, religious terms or concepts might be adapted to fit the target culture's beliefs, potentially altering theological interpretations and the intended impact of the original text.

Patronage plays a significant role in religious translation, as institutions such as religious organizations or governments often sponsor and oversee these endeavors (Shih, 2016). Their influence can dictate not only which texts are translated but also how they are framed and interpreted. The agendas of these patrons can lead to translations that promote specific doctrines or perspectives, thereby shaping religious discourse within the target culture.

Moreover, the poetics of the target culture affect how religious narratives are structured and conveyed, impacting the translation's accessibility and acceptance among readers (Lefevere, 2004). Translators may adapt stylistic elements to conform to the literary norms of the target language, which can enhance the text's appeal but may also result in a departure from the source text's original form and style.

Applying Lefevere's theoretical framework to the translation of the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch allows for an analysis of how ideology, patronage, and poetics influence translation strategies. It provides insight into whether and how EBBE's translation fulfills its stated philosophy of preserving the spirit of Chan Buddhism while making the teachings accessible to a global audience. By examining these factors, the study can assess the potential communicative effectiveness of the translation and identify areas where ideological or aesthetic considerations may have shaped the rendering of the text.

4 Methodology

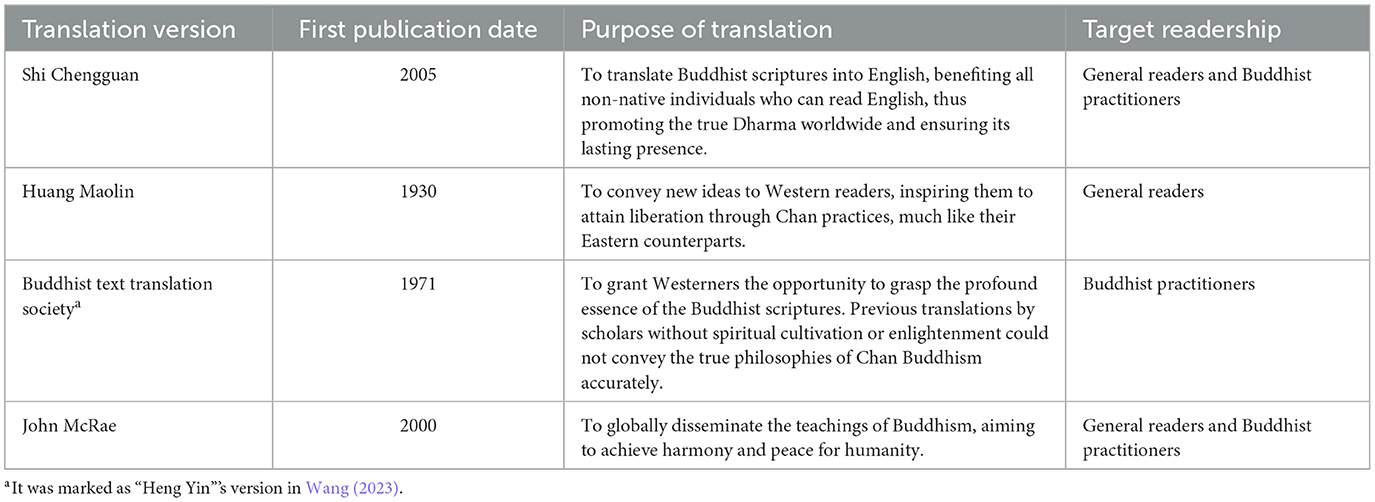

To address the research questions, this paper compares EBBE's translation of The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch with those of Shi Chengguan, Huang Maolin, the Buddhist Text Translation Society, and John McRae. This comparison is not intended to judge the quality of these translations as prior versions have been highly recognized by English-speaking readers and have greatly contributed to the dissemination of Buddhist culture (Wang, 2023, p. 7). However, the comparison serves as an effective method to examine the claimed translation philosophy of EBBE's version and in turn, being helpful to analyze it from the perspective of Lefevere's theory. The reasons for selecting these four among some 30 versions for comparison are as follows: (1) All four versions, along with EBBE's, are based on the same source text compiled by Zongbao and are complete translations (Wang, 2023, p. 26–27), making them comparable in content. (2) They were translated at different times with varied purposes and target readerships (Wang, 2023, p. 121–122), as shown in Table 1. (3) Since Shi Chengguang and Huang Maolin were native Chinese speakers, while McRae was a native English speaker and the translators of the Buddhist Text Translation Society may involve native English speakers, comparing translations by translators with different linguistic and cultural backgrounds may yield insights beneficial to future translation activities, especially for Buddhist sutras.

Table 1. Information on different translation versions of the Platform Sutra (extracted from Wang, 2023, p. 121–122).

To compare the different translation versions of the source text, this paper employs four analytical frameworks: translation of Buddhist terminologies, appraisal resources as defined in Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), thematic progression analysis, and the Flesch Reading Ease score. These methodologies provide a comprehensive assessment of the translations from linguistic, functional, and readability perspectives.

4.1 Terminology translation

The source Chinese text presents profound Buddhist teachings rich in specific terminology carrying deep conceptual meanings. Translating these terms is crucial for accurately conveying the philosophical and spiritual nuances of the teachings. By identifying key terms in the original Chinese text and comparing how each translation renders them, this paper discusses the relationships among the translated terms and comments on the effectiveness and accuracy of each translation.

4.2 Appraisal resources in systemic functional linguistics

The appraisal system, within the framework of SFL, concerns the linguistic resources by which speakers or writers express evaluations, judgments, and attitudes (Martin and White, 2005). It encompasses three main subsystems: Attitude, Engagement, and Graduation. Attitude deals with emotions, judgments of behavior, and appreciation of things. Engagement addresses the sourcing of attitudes and the negotiation of intersubjective stance. Graduation concerns grading phenomena by intensity or amount (Martin and Rose, 2007). By analyzing the appraisal resources in the translations, we can uncover how each translation conveys affect, judgment, appreciation, engagement, and graduation, and potentially how these choices may affect the interpersonal metafunction of the text.

4.3 Thematic progression

Thematic progression refers to how themes (the point of departure for the message) and rhemes (new information or the rest of the message) are organized and developed across a text, contributing to its coherence and cohesion (Daneš, 1974). Different patterns of thematic progression influence the flow of information and the ease with which a reader can follow the development of ideas. Analyzing thematic progression in the translations can reveal how effectively the translators have conveyed the original message and how their choices impact clarity, readability, and cohesion, thus affecting the textual metafunction of the translated texts.

4.4 Flesch Reading Ease

The Flesch Reading Ease (FRE) score is a readability formula assessing text complexity based on sentence length and word syllable count (Flesch, 1948). The score is calculated using the Average Sentence Length (ASL) and the Average Number of Syllables per Word (ASW) with certain formula. A higher FRE score indicates easier readability. Scores are interpreted as follows:

90–100: Very easy to read.

80–90: Easy to read.

70–80: Fairly easy to read.

60–70: Plain English.

50–60: Fairly difficult to read.

30–50: Difficult to read.

0–30: Very difficult to read.

In this analysis, we calculate the FRE scores for the five English translations of the same Chinese paragraph. This quantitative comparison of readability levels may reflect translators' choices affecting the text's accessibility to readers.

Ideally, understanding the effects on readers would involve conducting a reader survey. However, since EBBE's version has only recently been published, a survey is not feasible due to constraints. Therefore, this study analyzes the texts from the readers' perspective using the above indicators to predict potential communication effects as an interim replacement for a direct reader survey.

To understand the claimed translation philosophy of EBBE's version, stratified sampling—randomly selecting specimens from each distinct category—is employed to compare it with the four other versions on three representative types of paragraphs from the Chinese source text of The Platform Sutra: (1) a poem or gatha, a symbolic feature characterized by concise and vivid language conveying either Huineng's explanations of Buddhist teachings or others' understanding; (2) an expository paragraph on Buddhist teachings by Huineng, a primary form of writing in the sutra; (3) a narrative story, another distinctive aspect featuring enchanting storytelling that imbues the text with profound earthiness and captivates readers with its allure.

While it would be optimal to compare all paragraphs of The Platform Sutra across the five translation versions, this is impractical due to limited resources. It is reasonable to assume that if a translator maintains consistent strategies and quality throughout the entire sutra, a stratified sampling based on different types of narratives suffices to understand general trends across versions. Moreover, a detailed comparison of individually selected paragraphs may offer more specific insights than analyzing the entire sutra without differentiating different types of narratives, which might average out differences among various narrative types.

5 Discussion and findings

5.1 Poem/gatha

Source text:

通顿悟性智,遂呈偈曰:

三身元我体,四智本心明,

身智融无碍,应物任随形。

起修皆妄动,守住匪真精,

妙旨因师晓,终亡染污名。 (坛经:机缘品第七)

Target texts:

(EBBE) Zhitong immediately understood the teaching and put his insight in a poem:

“My body is just Three Bodies,And my mind is no other than Four Knowledges.

Bodies and Knowledges are in perfect harmony,

And manifest themselves to suit the conditions.

Deliberate practice is wrong.Idleness is not desirable either.

The wonderful Knowledge is revealed through the Master's teaching,

So all designations and defilements are abandoned at last.”

(Shi Chengguan) Thereupon Chi-Tong was instantly enlightened on the Quintessential Noesis, and so he presented a Gatha to express the state of his Enlightenment:

1 The Triple Corpora have always been my own Noumenon,

And the Four Noeses are my Native Mind in its translucent state.

When Corpora infused with Noeses, one would be impediment-free,

Capable of responding to people avatarically in compliance with situations.

2 It would be a delusive act in intending to cultivate oneself;

Yet to stay in immobility would not be the Quintessence, either.

Owing to the Master's instructions, I could apprehend the Wondrous Purports,

And could eventually eliminate all the Titular Defilements in my Mind.”

(Huang Maolin) (Upon hearing this.) Zhi Tong realized suddenly the Prajna of his Essence of Mind and submitted the following stanza to the Patriarch:

Intrinsically, the three Bodies are within our Essence of Mind. When our mind is enlightened, the four Prajnas will appear therein.

When Bodies and Prajnas absolutely identify with each other,

We shall be able to respond (in accordance with their temperaments and dispositions) to the appeals of all beings, no matter what forms they may assume.

To start by seeking for the Trikaya and the four Prajnas is to take an entirely wrong course (for being inherent in us they are to be realized and not to be sought)

To try to “grasp” or “confine” them is to go against their intrinsic nature. Through you, Sir, I am now able to grasp the profundity of their meaning,

And henceforth I may discard for ever their false and arbitrary names.

(The Buddhist Text Translation Society) Instantly enlightened to the nature of wisdom, ChihT'ung submitted the following verse:

Three bodies are my basic substance,

Four wisdoms my original bright mind.

Body and wisdom in unobstructed fusion:

In response to beings I accordingly take form.

Arising to cultivate them is false movement,

Holding to or pondering over them a waste of effort.

Through the Master I know the wonderful principle,

And in the end I lose the stain of names.

(John MacRae) Zhitong [achieved] sudden enlightenment to the nature and the wisdoms. He then offered this verse:

The three bodies are originally the essence of oneself.

The four wisdoms are fundamentally the understanding of the mind.

The bodies and wisdoms interpenetrate without hindrance

Responding to things in accordance with forms.

All [deliberate] activation of cultivation is false activity

To guard one's abiding is not true serenity.

The wondrous purport has been illuminated by the master.

I will forever forget [all] defiled names.

5.1.1 Terminology translation analysis

5.1.1.1 Translation 1: EBBE

This translation employs accessible language, rendering “三身” as “Three Bodies” and “四智” as “Four Knowledges.” While it conveys the general meaning, it uses “Knowledges” instead of the more commonly accepted “Wisdoms” in Buddhist contexts. The verses are straightforward and relatively easy for general readers to understand. And the translation captures the essence of the original text but simplifies nuanced meanings, potentially overlooking deeper philosophical implications. This poem maintains a simple and direct poetic structure, enhancing approachability.

5.1.1.2 Translation 2: Shi Chengguan

Utilizing technical and philosophical terms such as “Triple Corpora” for “三身,” “Noumenon” for “元我体,” and “Noeses” for “四智,” this translation reflects a scholarly approach aiming for precision. The use of specialized vocabulary may present challenges for readers without a background in philosophy or Buddhist studies. The translation strives to accurately reflect the profound concepts of the original text, though the complex terminology might obscure the intended meaning for some readers. The verses are presented in a formal and more academic tone, which may affect the poetic quality of the original gatha.

5.1.1.3 Translation 3: Huang Maolin

Employing traditional Buddhist terms such as “Trikaya” (Three Bodies), “Prajna” (Wisdom), and “Essence of Mind,” this translation aligns closely with established terminology. This translation provides explanatory notes within parentheses, assisting readers' understanding of complex concepts. It attempts to be precise by retaining key Buddhist terms and offering explanations, thus remaining true to the original meaning. The style balances scholarly accuracy with readability, though the inclusion of parenthetical explanations may interrupt the poetic flow.

5.1.1.4 Translation 4:the Buddhist Text Translation Society

This version uses accessible yet accurate terms like “Three bodies,” “Four wisdoms,” and “original bright mind,” which resonate with Buddhist teachings. The translation is clear and maintains the poetic nature of the original text. It faithfully represents the original verses, capturing both the literal meaning and spiritual insights. And the translation is concise and flows smoothly, preserving the rhythm and structure of the gatha.

5.1.1.5 Translation 5: John McRae

Employing precise Buddhist terms such as “three bodies,” “four wisdoms,” and “interpenetrate without hindrance,”, the translation is clear and direct, making it accessible while retaining depth. It closely adheres to the original text, effectively conveying both literal and metaphorical meanings. And the translation maintains a poetic and contemplative tone that reflects the spirit of the original gatha.

Translations by Shi Chengguan (Translation 2) and John McRae (Translation 5) utilize precise Buddhist terminology, which is crucial for conveying exact concepts. EBBE (Translation 1) and Buddhist Text Translation Society (Translation 4) offer more accessible language, making the profound teachings approachable for lay readers. Huang Maolin (Translation 3) provides additional explanations within the text, aiding comprehension but potentially disrupting the poetic flow.

Each translation offers a unique perspective on Zhitong's poem, reflecting different priorities in accuracy, readability, and style. The optimal translation depends on the intended audience and purpose. The translations by Shi Chengguan (Translation 2), Huang Maolin (Translation 3), and John McRae (Translation 5) provide precise terminology and a faithful representation of the original concepts and may be more suitable for academic study or in-depth philosophical exploration. The translations by EBBE (Translation 1) and the Buddhist Text Translation Society (Translation 4) offer clarity and maintain the poetic essence, making the profound teachings accessible and may be more suitable for general readership and introductory understanding.

5.1.2 Appraisal analysis of the translations

5.1.2.1 Attitude

Across all translations, there is a consistent positive appreciation of enlightenment and self-realization. Phrases such as:

“My body is just Three Bodies” (Translation 1).

“Triple Corpora have always been my own Noumenon” (Translation 2).

“Three bodies are my basic substance” (Translation 4).

“The three bodies are originally the essence of oneself” (Translation 5).

Each translation conveys a negative judgment of deliberate practice and attachment, critiquing misguided efforts toward enlightenment:

“Deliberate practice is wrong” (Translation 1).

“A delusive act in intending to cultivate oneself” (Translation 2).

“To start by seeking them elsewhere is to take an entirely wrong course” (Translation 3).

“Arising to cultivate them is false movement” (Translation 4).

“All [deliberate] activation of cultivation is false activity” (Translation 5).

The role of the Master in facilitating enlightenment is acknowledged in all translations, underscoring the importance of guidance:

“The wonderful Knowledge is revealed through the Master's teaching” (Translation 1).

“Owing to the Master's instructions, I have instantaneously been enlightened” (Translation 2).

“Through you, Sir, I absolutely identify with them” (Translation 3).

“Through the Master I know” (Translation 4).

“The wondrous purport has been illuminated by the master” (Translation 5).

A common element is the call to transcend or discard names and defilements, symbolizing the shedding of illusions:

“All designations and defilements are abandoned at last” (Translation 1).

“Eliminate all the Titular Defilements in my Mind” (Translation 2).

“Discard forever their false and arbitrary names” (Translation 3).

“Lose the stain of names” (Translation 4).

“Forever forget [all] defiled names” (Translation 5).

5.1.2.2 Engagement

All translations predominantly utilize monoglossic statements, presenting assertions confidently without referencing alternative viewpoints. This authoritative tone reinforces the conviction of the speaker's enlightened understanding.

5.1.2.3 Graduation

Intensifiers and absolutes are employed to emphasize the profundity and certainty of the enlightenment experience:

Intensifiers such as “just,” “always,” “instantaneously,” “forever,” and “unobstructed.”

Absolute terms like “all,” “no other than,” “entirely,” “fundamentally,” and “impediment-free.”

These linguistic choices amplify the statements and underscore the definitive nature of the insights conveyed.

5.1.3 Thematic progression

5.1.3.1 Translation 1: EBBE

Thematic progression patterns:

Parallel Themes: The first two lines begin with possessive structures (“My body,” “And my mind”), focusing on the speaker's personal experience.

Topical Shifts: Themes shift from personal elements (“body,” “mind”) to abstract concepts (“Bodies and Knowledges,” “Deliberate practice,” “Idleness,” “The wonderful Knowledge,” “All designations and defilements”).

Anaphoric Reference: “And manifest themselves” references the preceding rheme, maintaining cohesion.

Logical Connectives: Conjunctions like “And” and “So” link clauses, indicating relationships between ideas.

The translation employs clear, straightforward sentences with familiar structures. Simple language and parallel constructions enhance readability. Despite thematic shifts, cohesion is maintained through logical connectives and pronouns. The blend of personal and impersonal themes balances personal enlightenment with universal concepts. This translation effectively progresses from personal realization to broader philosophical truths, creating a clear and cohesive narrative.

5.1.3.2 Translation 2: Shi Chengguan

Thematic progression patterns:

Complex nominal groups: Themes often contain technical terms (“Triple Corpora,” “Four Noeses”), which may be unfamiliar to readers.

Circumstantial themes: Use of circumstantial adjuncts (“When,” “Owing to”) provides context.

Ellipsis and continuation: Lines continue ideas from previous ones, but omitted subjects can affect clarity.

Specialized terminology and complex themes may pose challenge for general readers, and long and intricate themes can reduce readability. Logical links exist, but abrupt thematic shifts and heavy jargon may disrupt cohesion. While capturing the philosophical depth of the original, the use of specialized language and complex structures may reduce accessibility.

5.1.3.3 Translation 3: Huang Maolin

Thematic progression patterns:

Circumstantial and hypothetical themes: Markers like “Intrinsically” and “When” set conditions in the initial lines.

Shift from general to personal: Themes move from universal truths to personal experiences (“We,” “I”).

Parallel structures: Infinitive phrases as themes emphasize actions to be avoided.

Explanations in parentheses aid understanding but may interrupt flow, which may in turn affect readability. Logical progression from general principles to personal realization enhances thematic development. The translation balances philosophical depth with explanations, aiding comprehension but potentially disrupting the poem's rhythm.

5.1.3.4 Translation 4: the Buddhist Text Translation Society

Thematic progression patterns:

Parallel themes: Initial lines use parallel structures (“Three bodies,” “Four wisdoms,” “Body and wisdom”), establishing thematic connections.

Shift from abstract to personal: Themes progress from abstract concepts to personal actions (“I”).

Circumstantial adjuncts: Phrases like “In response to beings” and “Through the Master” provide context.

Clear, concise sentences with minimal technical jargon enhance understanding. Parallelism and straightforward language improve readability. Strong thematic links and logical progression create a smooth flow of ideas. This translation effectively balances poetic expression with clarity, contributing to a cohesive and accessible text.

5.1.3.5 Translation 5: John McRae

Thematic progression patterns:

Consistent themes: Focus on key concepts (“three bodies,” “four wisdoms”) maintains thematic consistency.

Infinitive phrases as themes: Verb phrases emphasize actions.

Shift to Personal Theme: Final line uses “I,” highlighting personal enlightenment.

The language is overall accessible, but clarifications in brackets, while aid understanding may somehow be distracting. Cohesive progression from universal concepts to personal realization is maintained. This translation combines clarity with scholarly precision while bracketed explanations clarify meanings but may affect rhythm.

Translations 1 and 4, with straightforward language and familiar structures, are most accessible to general readers. Translation 5 offers a balance, using precise terminology with accessible language. Translations 2 and 3 may be less clear to those unfamiliar with technical terms due to specialized vocabulary and complex structures.

Translation 4 seems to excel with parallelism and logical progression, creating a cohesive text. Translation 1 maintains cohesion through conjunctions and pronouns. Translations 2 and 3 have logical progressions but may seem fragmented due to shifting themes and complex constructs. Translation 5 effectively leads readers from abstract ideas to personal understanding.

Translation 1 (EBBE) and Translation 4 (The Buddhist Text Translation Society) may be more suitable for general readership for their clear language, familiar structures, and cohesive thematic progression. Translation 2 (Shi Chengguan) and Translation 3 (Huang Maolin) may be more suitable for scholarly study for their detailed exploration of concepts with specialized terminology, being suitable for readers interested in in-depth philosophical analysis. Translation 5 (John McRae) combines clarity with precise terminology, may be appropriate for readers seeking both accessibility and detailed comprehension.

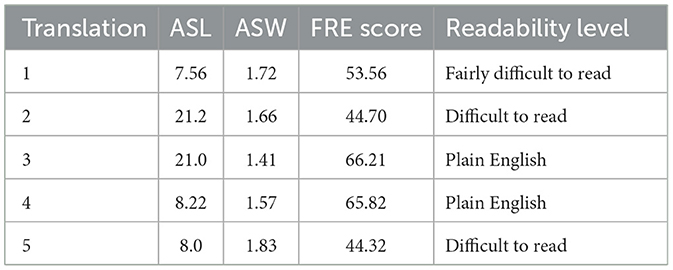

Translations 3 and 4 have higher FRE scores (66.21 and 65.82), indicating they are easier to read and fall within the plain English category (See Table 2). Translations 1, 2, and 5 have lower FRE scores, making them more difficult to read. However, Translation 1 (53.56) strikes a balance but leans toward being fairly difficult to read while Translation 2 is the most challenging due to its long sentences and use of specialized vocabulary.

5.2 Expository paragraph

Source text: 师复曰:诸善知识,汝等各各净心,听吾说法。若欲成就种智,须达一相三昧,一行三昧。若于一切处而不住相,于彼相中不生憎爱,亦无取舍,不念利益成坏等事,安闲恬静,虚融澹泊,此名一相三昧。若于一切处,行住坐卧,纯一直心,不动道场,真成净土,此名一行三昧。若人具二三昧,如地有种,含藏长养,成熟其实,一相一行,亦复如是。我今说法,犹如时雨,普润大地。汝等佛性,譬诸种子,遇兹沾洽,悉皆发生。承吾旨者,决获菩提;依吾行者,定证妙果。(付嘱品第十)

Target texts:

(EBBE)The Master went on, “My Dharma friends, now clear your mind and listen to my teaching. Through One-form Samādhi and One-practice Samādhi, you can attain All-encompassing Wisdom. One-form Samādhi refers to the state in which one's mind does not cling to any form at any time. In this state, free from hatred and love, and a sense of gain and loss, he remains collected, desireless, peaceful, and receptive. One-practice Samādhi refers to the state in which one's mind is authentic and undisturbed under any circumstance: walking, standing, sitting, or lying. This state is where Pure Land exactly is. These two Samādhi-s, once attained can bring benefits as soil enables seeds to grow and yield fruits. This teaching is like timely rain that nourishes beings on the earth. Your Buddha Nature is like the seeds that wake up in the rain. Those who practice according to my instruction will definitely obtain Bodhi, the spiritual fruit.”

(Shi Chenggguan)The Master said again, “Good Mentors, now I would like each one of you to purge your own mind, so as to listen to the Dharma that I am going to divulge unto you: if you desire to attain the Seminal-Noesis,1 you need to apprehend thoroughly the Uni-appearance Samadhi2 and Uni-performance Samadhi.3 Wherever you are, if you would not reside in any Appearance, nor

nurture Detestation or Attachment toward that same Appearance, nor would you seize or repel it, nor ponder over any matter pertaining to benefit, success, or failures, insofar that you could always stay peacefully unengaged, suavely serene, unfervently congenial, and non-chalantly content; such state is termed the Uni-appearance Samadhi.”

“Whereas, wherever you are, during your walking, standing, sitting, or reclining, if you could maintain the Purified One Straight Mind as your Immotive4 Bodhi-Site,5 thereby to realize the Pure-Land truthfully, this state is called the Uni-performance Samadhi.”

“Whoever is endowed with these two Samadhis, he can be compared to the Soil with Seeds therein. This Soil will contain and conceal those Seeds, and it will also nurture and nourish them to make them grow and mature until Fruition. By the same token, the Uni-appearance Samadhi, and the Uni-execution Samadhi would act exactly like this Soil. Now the Dharma that I am divulging is like the opportune

Rain, which will moisten all the ground universally; whereas your Buddha Nature could be compared to the Seeds, which on encountering the Rain's moisture will all start burgeoning. Those who succeed to my Animus are assuredly to obtain Bodhi. Those who implement pursuant to my teachings are decidedly to attest the wondrous Fructifications.

(Huang Maolin)The Patriarch added, “Learned Audience, purify your minds and listen to me. He who wishes to attain the All knowing Knowledge of a Buddha should know the 'Samadhi of Specific Object' and the 'Samadhi of Specific Mode.' In all circumstances we should free ourselves from attachment to objects, and our attitude toward them should be neutral and indifferent. Let neither success nor failure, neither profit nor loss, worry us. Let us be calm and serene, modest and accommodating, simple and dispassionate. Such is the 'Samadhi of Specific Object,' On all occasions, whether we are standing, walking, sitting or reclining, let us be absolutely straightforward. Then, remaining in our sanctuary, and without the least movement, we shall virtually be in the Kingdom of Pure Land. Such is the 'Samadhi of Specific Mode.”'

“He who is complete with these two forms of Samadhimay be likened to the ground with seeds sown therein. Covered up in the mud, the seeds receive nourishment therefrom and grow until the fruit comes into bearing.”

“My preaching to you now may be likened to the seasonable rain which brings moisture to a vast area of land. The Buddha nature within you may be likened to the seed which, being moistened by the rain, will grow rapidly. He who carries out my instructions will certainly attain Bodhi. He who follows my teaching will certainly attain the superb fruit (or Buddhahood).”

(Buddhist Text Translation Society)The Master added, “All of you Good Knowing Advisors should purify your minds and listen to my explanation of the Dharma. If you wish to realize all knowledge, you must understand the Samadhi of One Mark and the Samadhi of One Conduct.”

“If you do not dwell in marks anywhere and do not give rise to hate or love, do not grasp or reject, and do not calculate advantage or disadvantage, productionand destruction while in the midst of marks, but instead remain tranquil, calm, and yielding, then you will have achieved the Samadhi of One Mark.”

“In all places, whether walking, standing, sitting, or lying down, to maintain a straight and uniform mind, to attain the unmoving Bodhimanda and the true realization of the Pure Land. That is called the Samadhi of One Conduct.” “One who perfects the two samadhis is like earth in which seeds are planted; buried in the ground, they are nourished and grow, ripening and bearing fruit. The One Mark and One Conduct are just like that.”

“I now speak the Dharma which is like the falling of the timely rain, moistening the great earth. Your Buddha-nature is like the seeds which, receiving moisture, will sprout and grow. Those who receive my teaching will surely obtain Bodhi and those who practice my conduct will certainly certify to the wonderful fruit.”

(John MaRae)The master said further, “Good friends, you have each purified your minds and listened to me preach the Dharma. If you wish to achieve the planting [of the roots] of wisdom,6 you must master the sam'adhi of the single characteristic and the sam'adhi of the single practice. If in all locations you do not reside in characteristics, if within those characteristics you do not generate revulsion or attraction and are also without grasping or rejecting if you do not think about matters such as the creation and destruction of [personal] benefit, and if you are relaxed and quiet and emptily melded with the pallid and simple, this is called the sam'adhi of the single characteristic.”

“If in all your walking, standing still, sitting, and lying down you have a pure and unified straightforward mind, not moving [from the] place of enlightenment, truly creating a pure land, this is called the sam'adhi of the single practice.”

“Those who accomplish both sam'adhis are like the earth bearing seeds, which it stores and nourishes during their maturation into fruit. So is it with the [sam'adhis of] the single characteristic and single practice. My preaching the Dharma to you now is like the timely rains that moisten the great earth, and your buddha-natures are likened to the seeds: encountering this watering, [your buddha-natures] will all begin to grow. Those who partake of my meaning will definitely attain bodhi! Those who rely upon my practice will certainly realize the wondrous fruit!”

5.2.1 Terminology translation analysis

5.2.1.1 Translation 1: EBBE

It provides clear translations using straightforward language, making the text comprehensible to a broad audience. It directly

translates certain terms, such as One-form Samādhi, preserving their technical significance within Buddhist philosophy. However, there is occasionally combines terms (e.g., “This state is where Pure Land exactly is”), which may merge separate concepts and slightly alter their distinct meanings.

5.2.1.2 Translation 2: Shi Chengguan

It strives for precision by retaining original terms and providing detailed translations. It includes explanations, sometimes as footnotes, to clarify complex concepts. However, it employs uncommon or archaic English terms (e.g., “Seminal-Noesis,” “Immotive”) that may can obscure the intended meaning, which in turn hinder comprehension for modern readers and reduce readability.

5.2.1.3 Translation 3: Huang Maolin

It engages readers directly through inclusive phrasing, enhancing relational connection. It converts terms into accessible English, facilitating understanding for those less familiar with Buddhist terminology. However, some translations (e.g., “Samadhi of Specific Object”) may not accurately reflect the original terms, potentially leading to misinterpretation.

5.2.1.4 Translation 4: the Buddhist Text Translation Society

It provides faithful translations of key terms, closely adhering to the original Chinese terminology. It employs clear and accessible language, enhancing readability for both practitioners and general readers. It utilizes established Buddhist terms familiar within the tradition, aiding comprehension among practitioners. However, there is occasionally simplified terms (e.g., translating “种智” as “All knowledge”), which may reduce the depth and nuance of the original meaning.

5.2.1.5 Translation 5: John McRae

It offers a detailed and academically rigorous translation, demonstrating deep engagement with the text. It provides notes on uncertainties and textual nuances, reflecting a thoughtful consideration of interpretative challenges. However, it uses sophisticated phrasing and scholarly terminology that may be challenging for general readers. And added explanations within translations can interrupt the textual flow, affecting readability.

Translation 4 (The Buddhist Text Translation Society) and Translation 1 (EBBE) seems to be most effective in faithfully translating terms while maintaining clarity and accessibility. They preserve original meanings and philosophical nuances, making the teachings accessible to both practitioners and general readers. Translation 2 (Shi Chenggguan) and Translation 5 (John McRae) provide detailed and scholarly translations suitable for academic study but may challenge readers due to their complex language and technical terminology. Translation 3 (Huang Maolin) offers an engaging narrative with inclusive language.

5.2.2 Appraisal resources analysis

5.2.2.1 Translation 1: EBBE

5.2.2.1.1 Attitude

Affect: The translation conveys positive emotional states such as being “collected,” “desireless,” “peaceful,” and “receptive,” effectively reflecting the original terms 安闲恬静 (tranquil and serene) and 虚融澹泊 (open and unassuming).

Judgment: It emphasizes the avoidance of negative emotions by stating that one remains “free from hatred and love, and a sense of gain and loss,” accurately translating 不生憎爱, 不念利益成坏等事 (do not give rise to hatred or love, do not contemplate gain and loss). Positive behaviors are highlighted through “mind is authentic and undisturbed,” aligning with 纯一直心 (maintain a pure and straightforward mind).

Appreciation: Metaphors are retained and effectively translated, such as “This teaching is like timely rain that nourishes beings on the earth… Your Buddha Nature is like the seeds that wake up in the rain,” faithfully conveying 犹如时雨,普润大地… 譬诸种子,遇兹沾洽,悉皆发生.

5.2.2.1.2 Engagement

Directives: Uses direct instructions like “Now clear your mind and listen to my teaching,” reflecting 汝等各各净心,听吾说法.

Inclusive address: Addresses “My Dharma friends,” translating 诸善知识 (good and wise friends) inclusively.

Monoglossic presentation: Presents teachings as authoritative statements without referencing alternative viewpoints.

5.2.2.1.3 Graduation

Force: Employs certainty through phrases like “will definitely obtain Bodhi, the spiritual fruit,” matching 承吾旨者,决获菩提;依吾行者,定证妙果.

Focus: Maintains emphasis on key concepts without dilution.

The EBBE translation closely mirrors the original text's appraisal resources, effectively conveying emotional states, judgments, and metaphors in accessible language. The instructive and encouraging tone is preserved, making the teachings clear and relatable to readers.

5.2.2.2 Translation 2: Shi Chengguan

5.2.2.2.1 Attitude

Affect: Describes emotional states with phrases like “peacefully unengaged, suavely serene, unfervently congenial, and non-chalantly content,” elaborating on 安闲恬静,虚融澹泊 but with more complex language.

Judgment: Advises the avoidance of negative behaviors, stating “nor nurture Detestation or Attachment,” corresponding to 不生憎爱. Positive behaviors are encouraged through “maintain the Purified One Straight Mind,” aligning with 纯一直心.

Appreciation: Retains metaphors but elaborates on them: “Dharma… like the opportune Rain… Buddha Nature could be compared to the Seeds,” preserving the original imagery.

5.2.2.2.2 Engagement

Directives: Uses formal instructions like “I would like each one of you to purge your own mind,” reflecting 汝等各各净心.

Formal address: Addresses “Good Mentors,” translating 诸善知识 but with a more formal tone.

Authoritative tone: Employs sophisticated vocabulary, asserting formality.

5.2.2.2.3 Graduation

Force: Expresses certainty with phrases like “are assuredly to obtain Bodhi” and “are decidedly to attest the wondrous Fructifications,” matching 决获菩提;定证妙果.

The Shi Chenggguan translation preserves much of the original's appraisal resources but utilizes complex and archaic language. The affective expressions are intensified with multiple adjectives, which may detract from the original's simplicity. The formal tone may create distance between the text and reader, potentially affecting engagement.

5.2.2.3 Translation 3: Huang Maolin

5.2.2.3.1 Attitude

Affect: Uses inclusive language with phrases like “Let us be calm and serene, modest and accommodating, simple and dispassionate,” corresponding to 安闲恬静,虚融澹泊.

Judgment: Instructs the avoidance of negative emotions: “Let neither success nor failure, neither profit nor loss, worry us,” translating 不念利益成坏等事. Positive behaviors are encouraged: “Let us be absolutely straightforward,” reflecting 纯一直心.

Appreciation: Adjusts metaphors by introducing terms like “Kingdom of Pure Land,” while the original was 真成净土 (truly become Pure Land).

5.2.2.3.2 Engagement

Directives: Employs inclusive imperatives with “Let us…,”, encouraging collective action in line with the original's communal address.

Inclusive address: Addresses the “Learned Audience,” translating 诸善知识.

5.2.2.3.3 Graduation

Force: Maintains expressions of certainty: “He who carries out my instructions will certainly attain Bodhi,” mirroring the original's assured outcomes.

The Huang Maolin translation captures the original's appraisal resources and employs inclusive language that engages readers. While affective and judgmental resources are effectively conveyed, some adaptations may diverge a little from the original.

5.2.2.4 Translation 4: the Buddhist Text Translation Society

5.2.2.4.1 Attitude

Affect: Conveys positive emotional states with “remain tranquil, calm, and yielding,” corresponding to 安闲恬静,虚融澹泊.

Judgment: Advises avoidance of negative behaviors: “Do not give rise to hate or love, do not grasp or reject, and do not calculate advantage or disadvantage,” accurately translating 不生憎爱,亦无取舍,不念利益成坏等事. Encourages maintaining “a straight and uniform mind,” reflecting 纯一直心.

Appreciation: Preserves metaphors faithfully: “I now speak the Dharma which is like the falling of the timely rain… Your Buddha-nature is like the seeds,” accurately conveying the original imagery.

5.2.2.4.2 Engagement

Directives: Provides clear instructions: “should purify your minds and listen to my explanation of the Dharma.”

Inclusive address: Addresses “All of you Good Knowing Advisors,” directly translating 诸善知识.

5.2.2.4.3 Graduation

Force: Expresses certainty with “Will surely obtain Bodhi… will certainly certify to the wonderful fruit,” matching the original's emphasis on assured outcomes.

This translation closely mirrors the original text's appraisal resources, effectively conveying emotional states, judgments, and metaphors in clear language. The instructive and authoritative tone is maintained, providing a faithful and accessible rendition of the teachings.

5.2.2.5 Translation 5: John McRae

5.2.2.5.1 Attitude

Affect: Describes emotional states with “relaxed and quiet and emptily melded with the pallid and simple,” translating 安闲恬静,虚融澹泊 but with complex phrasing.

Judgment: Advises avoidance of negative behaviors: “Do not generate revulsion or attraction and are also without grasping or rejecting,” corresponding to 不生憎爱,亦无取舍. Encourages having “a pure and unified straightforward mind,” reflecting 纯一直心.

Appreciation: Retains metaphors: “My preaching the Dharma… is like the timely rains that moisten the great earth… Your buddha-natures are likened to the seeds,” preserving the original imagery.

5.2.2.5.2 Engagement

Acknowledgment of audience's efforts: Adds appreciation with “You have each purified your minds and listened to me preach the Dharma,” which is an interpretive addition not explicitly present in the original.

Directives: Instructions are present but less direct than in other versions.

5.2.2.5.3 Graduation

Force: Uses certainty with “will definitely attain bodhi! Will certainly realize the wondrous fruit!” aligning with the original's expressions of assurance.

The John McRae version captures the appraisal resources but introduces complexity through scholarly language and added explanations. The formal tone and complex phrasing may challenge readers, potentially affecting comprehension.

The EBBE Version and Buddhist Text Translation Society Version may be more suitable for readers seeking clarity and faithfulness for their accurate and accessible translations that faithfully convey the original text's appraisal resources and tone. The John McRae Version offers detailed insights and addresses textual nuances, suitable for in-depth analysis by readers with a background in Buddhist studies. The Shi Chenggguan Version may also appeal to those familiar with technical Buddhist terminology and who prefer a formal tone. The Huang Maolin Version provides an inclusive approach that may resonate with readers seeking a communal and participatory tone.

5.2.3 Thematic progression analysis

5.2.3.1 Translation 1: EBBE

Thematic progression patterns:

Constant Theme Progression: Repeated themes of One-form Samādhi, One-practice Samādhi, and This state maintain focus.

Linear Progression: The rheme of one clause becomes the theme of the next, e.g., This state→These two Samādhi-s.

The EBBE version effectively maintains the thematic progression of the original. The clear alignment of themes aids in preserving the logical flow and coherence. And the translation facilitates understanding by mirroring the structure of the original.

5.2.3.2 Translation 2: Shi Chengguan

Thematic progression patterns:

Complex themes: Long and intricate themes may affect clarity.

Frequent thematic shifts: Changes in themes may make it harder to follow the progression.

The translation captures the thematic elements but uses complex sentence structures. The intricate language and extended themes can obscure the logical flow compared to the original. There seems to be a deviation from the simplicity and directness of the original thematic progression.

5.2.3.3 Translation 3: Huang Maolin

Thematic progression patterns:

Consistent use of imperatives: Maintains thematic focus on collective action.

Parallel structures: Similar to the original's use of conditional clauses starting with 若 (If).

The thematic progression aligns fairly well with the original. The inclusive language enhances engagement though with slight shifts from the original themes.

5.2.3.4 Translation 4: the Buddhist Text Translation Society

Thematic progression patterns:

Linear progression: Rhemes become themes in subsequent clauses, maintaining coherence.

Consistent themes: Key terms are repeated to reinforce focus.

The translation effectively reflects the thematic progression of the original. The logical flow and coherence are preserved, aiding in understanding. The clarity of expression enhances alignment with the original themes.

5.2.3.5 Translation 5: John McRae

Thematic progression patterns:

Interrupted flow: Explanatory notes and parenthetical comments disrupt the thematic progression.

Complex themes: Lengthy conditional themes may affect clarity.

While the translation captures key themes, the added complexities can impede alignment with the original's progression.

EBBE and Buddhist Text Translation Society Versions may be more suitable for readers seeking faithfulness and clarity as they offer the closest alignment with the original thematic progression and provide clear, coherent teachings. Huang Maolin Version may be more suitable for readers seeking inclusive language as it is engaging but be mindful of potential shifts in terminology. John McRae Version and Shi Chenggguan Version may be more suitable for academic study as the former provides scholarly insights but may diverge from the original's thematic simplicity and the latter offers depth but may challenge readability.

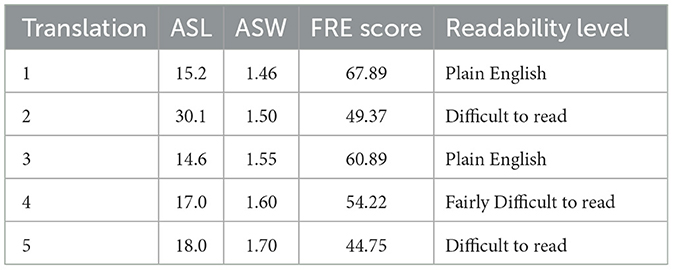

EBBE and Huang Maolin versions have the highest FRE scores, making them the most accessible to a general audience (See Table 3). Buddhist Text Translation Society Version version is slightly more challenging but remains accessible to readers with some familiarity with philosophical texts. Shi Chenggguan and John McRae version has the lowest FRE score, indicating that it is significantly more difficult to read and suited for an academic audience.

5.3 Story narrative

Source text:

惠能严父,本贯范阳。左降流于岭南,作新州百姓;此身不幸,父又早亡,老母孤遗,移来南海,艰辛贫乏,于市卖柴。时,有一客买柴,使令送至客店;客收去,惠能得钱,却出门外,见一客诵经。惠能一闻经语,心即开悟,遂问:客诵何经?客曰:《金刚经》。复问:从何所来,持此经典?客云:我从蕲州黄梅县东禅寺来。其寺是五祖忍大师在彼主化,门人一千有余;我到彼中礼拜,听受此经。大师常劝僧俗:但持《金刚经》,即自见性,直了成佛。(行由品第一)

Target texts:

(EBBE) “My father, a native of Fanyang County, was deprived of his official status and banished to Xinzhou, Lingnan as a mere commoner. Unfortunately, he passed away when I was young, leaving my mother and me in a dire situation. Impoverished, we moved to Nanhai and made a living by collecting and selling firewood. One day, someone bought my firewood and asked me to send it to his shop. I went to the shop and was paid there. Just as I was about to leave, I saw a Frcustomer chanting a sutra. On hearing it, I was suddenly enlightened. So I asked him what sutra he was chanting. He said, ‘The Diamond Sutra.' I then asked him where he was from and how he got this sutra. He replied, ‘I came from the Dongchan Temple in Huangmei, Qizhou.' The Fifth Patriarch Master Hongren presides there with more than one thousand followers. I paid a visit there and received the teachings on this sutra. He often advised monastics and the laity to chant The Diamond Sutra, which would lead directly to your Intrinsic Nature and Buddhahood.”'

(Shi Chenggguan)My father was originally from Fan-Yang County, but for some reason he was demoted and relocated to Ling-Nan area, ending up with becoming an ordinary citizen in Hsin State. Unfortunately, my father passed away early, and thereafter my elderly widowed mother, together with me, her bereaved only child, moved over to this area, Nan-Hai. We lived in hardship and destitute, and I used to sell firewood in the market place for a living.

Once a customer bought some firewood from me and demanded me to send the wood to his tavern lodge, which I did. The customer took the firewood from me; thereupon I collected the money, and withdrew outside the doorway, where I saw a wayfarer reciting some Sutra. On hearing the Words of the Sutra, at that very instant, I was enlightened in the mind. Thence I asked him what the Sutra was that he was reciting. He said, “The Diamond Sutra.7” I then enquired of him where he came from, and how he came to practice this Sutra. He replied, “I just came from East Ch'an Temple at Huang-Mei County in Chi State. That temple is now presided by the Fifth Patriarch, Master Hong-Jen, who is the major Dharma8 Master there, with more than one thousand disciples under him. When I went there to pay homage to the Master, I was exposed to the teachings of this Sutra from the Master himself. The Master frequently exhorts both the Clerical9 and the Laity by saying that if only one can sustain The Diamond Sutra, one shall be able to perceive one's own Innate Essence10 of one's own accord, and thereby to be enlightened directly to attain Buddhahood.”

(Huang Maolin)My father, a native of Fanyang, was dismissed from his official post and banished to be a commoner in Xinzhou in Guangdong. I was unlucky in that my father died when I was very young, leaving my mother poor and miserable. We moved to Nanhai and were then in very bad circumstance. I had to sell firewood in the market. One day, one of my customers ordered some firewood to be brought to his shop. Upon delivery being made and payment received, I left the shop, outside of which I found a man reciting a Sutra. As soon as I heard the text of this Sutra my mind at once became enlightened. Thereupon I asked the man the name of the book he was reciting and was told that it was the Diamond Sutra (Vajracchedika or Diamond Cutter). I further enquired whence he came and why he recited this particular Sutra. He replied that he came from Dongchan Monastery in the Huangmei District of Qizhou; that the Abbot in charge of this temple was Hong Ren, the Fifth Patriarch; that there were about one thousand disciples under him; and that when he went there to pay homage to the Patriarch, he attended lectures on this Sutra. He further told me that His Holiness used to encourage the laity as well as the monks to recite this scripture, as by doing so they might realize their own Essence of Mind, and thereby reach Buddahood directly.

(Buddhist Text Translation Society) “Hui Neng's stern father was originally from Fan Yang. He was banished to Hsin Chou in Ling Nan, where he became a commoner. Unfortunately, his father soon died, and his aging mother was left alone. They moved to Nan Hai and, poor and in bitter straits, Hui Neng sold wood in the market place.”

Once a customer bought firewood and ordered it delivered to his shop. When the delivery had been made, and Hui Neng had received the money, he went outside the gate, where he noticed a customer reciting a Sutra. Upon once hearing the words of this Sutra: “One should produce that thought which is nowhere supported.” Hui Neng's mind immediately opened to enlightenment.

Thereupon he asked the customer what Sutra he was reciting. The customer replied, “The Diamond Sutra.”

Then again he asked, “Where do you come from, and why do you recite this Sutra?”

The customer said, “I come from Tung Ch'an Monastery in Ch'i Chou, Huang Mei Province. There the Fifth Patriarch, the Great Master Hung Jen dwells, teaching over one thousand disciples. I went there to make obeisance and heard and received this Sutra.”

“The Great Master constantly exhorts the Sangha and laity only to uphold The Diamond Sutra. Then, they may see their own nature and straightaway achieve Buddhahood.”

(John MaRae)”My father was a native of Fanyang (Zhuo Xian, Hebei), but he was banished to Lingnan and became a commoner in Xinzhou (Xinxing Xian, Guangdong). I have been unfortunate: my father died early, and my aged mother and I, her only child, moved here to Nanhai.11 Miserably poor, I sold firewood in the marketplace.”

“At one time, a customer bought some firewood and had me deliver it to his shop, where he took it and paid me. On my way out of the gate I saw someone12 reciting a sutra, and as soon as I heard the words of the sutra my mind opened forth in enlightenment. I then asked the person what sutra he was reciting, and he said, ‘The Diamond Sutra.' I also asked, ‘Where did you get this sutra?' He said, ‘I have come from Dongchansi (‘Eastern Meditation Monastery') in Huangmei Xian in Qizhou (Qizhun, Hubei). The Fifth Patriarch, Great Master Hongren, resides at and is in charge of instruction at that monastery. He has over a thousand followers. I went there, did obeisance to him, and received this sutra there. Great Master [Hongren] always exhorts both monks and laymen to simply maintain the Diamond Sutra, so that one can see the [self]-nature13' by oneself and achieve buddhahood directly and completely.”

5.3.1 Terminology translation analysis

Translation 1, 3, and 5 tend to offer straightforward translations that closely align with the original terms. Translation 2 sometimes uses different terms (“wayfarer,” “tavern lodge”) that, while not incorrect, add nuances not explicitly present in the original. Translation 4 includes more descriptive additions (e.g., “stern father”) and provides the Sutra quote, which, while enriching, may introduce elements not detailed in the original passage.

As for the translation of “严父,”, only Translation 4 translates this term as “stern father,” adding an appraisal while other versions simply use “my father.”

As for the translation of “客店,”, most versions use “shop,” possibly due to modern interpretations or target audience familiarity while Translation 2's “tavern lodge” aligns more closely with “inn,” reflecting the historical context.

As for the translation of “客,”, “Customer” is the prevalent choice, fitting the context of purchasing firewood, while translation 2's “wayfarer” adds a sense of a traveler, which is a valid interpretation but shifts the focus slightly.

5.3.2 Appraisal resources analysis

5.3.2.1 Translation 1: EBBE

Affect:

“Unfortunately, he passed away when I was young, leaving my mother and me in a dire situation.”

Translation Accuracy: Captures the original affective meaning of misfortune and loss (此身不幸,父又早亡).

Additional Intensification: “Dire situation” intensifies the hardship (艰辛贫乏).

Judgment:

“was deprived of his official status and banished”: Accurately reflects the negative judgment of the father's fate (左降流于岭南).

Appreciation:

“As a mere commoner”: Emphasizes the loss of status, aligning with 作新州百姓.

“Impoverished, we moved to Nanhai”: Conveys economic hardship.

Graduation:

“Suddenly enlightened”: Mirrors 心即开悟, emphasizing immediacy.

This version remains faithful to the original text's appraisal resources, effectively conveying the emotions, judgments, and appreciations. The use of terms like “dire situation” and “impoverished” enhances the emotional impact, similar to the original. It maintains the original's tone without adding significant bias or additional judgment.

5.3.2.2 Translation 2: Shi Chengguan

Affect:

“Unfortunately, my father passed away early”: Reflects the original sense of misfortune.

“We lived in hardship and destitute”: Corresponds to 艰辛贫乏, though “destitute” should be “destitution”.

Judgment:

“For some reason, he was demoted”: Introduces uncertainty not explicit in the original.

“Demanded me to send the wood”: Adds a negative judgment toward the customer, not present in the original 使令送至客店 (asked me to deliver).

Appreciation:

“Hardship and destitute”: Aligns with 艰辛贫乏.

“Wayfarer reciting some Sutra”: “Wayfarer” adds a literary flavor but diverges from 一客 (a traveler/customer).

Graduation:

“At that very instant, I was enlightened in the mind”: Emphasizes immediacy, matching 心即开悟.