- 1College of Mass Communication, Ajman University, Ajman, United Arab Emirates

- 2Mass Communication, Ajman University, Ajman, United Arab Emirates

Introduction: This study examines the impact of translating international logos into Arabic on brand awareness and corporate image within the Arabian Gulf region. The research draws on semiotic theory, brand culture frameworks, localization strategies, and cognitive processing models to understand how culturally adapted visual identities influence consumer perceptions.

Methods: A quantitative, cross-sectional survey was conducted with 217 participants across Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. The study measured emotional engagement, cultural relevance, brand recognition, and perceptions of professionalism. Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses, including correlation and regression tests, were applied to assess the relationships between logo translation and key brand outcomes.

Results: The findings revealed that translating logos into Arabic significantly enhances brand recognition, with 63.5% of respondents reporting improved recall. In addition, 78.3% associated visually harmonious translated logos with higher professionalism and corporate commitment. Translated logos were also perceived as more culturally relevant and emotionally engaging, fostering stronger trust and connection between brands and consumers.

Discussion: The results highlight the strategic value of culturally adapted visual identities in enhancing brand salience and corporate reputation in the Gulf region. By balancing global brand consistency with local cultural integration, marketers and brand managers can strengthen consumer trust and engagement. The study contributes to cross-cultural branding literature and offers practical implications for global companies operating in competitive GCC markets.

1 Introduction

In the modern global market, brands constantly strive to expand their reach and establish a strong presence in diverse cultural and linguistic environments. With its rich cultural heritage and rapidly growing economies, the Arabian Gulf region represents an important and lucrative market for global brands (Sun, 2024). However, success in this market requires more than high-quality products and services; It requires a deep understanding of local cultural differences and strategic adaptation of brand elements to resonate with the local consumer base. One of this adaptation’s most visible and influential aspects is the translation of brand logos (Yu, 2024).

Logos are the cornerstone of a brand’s identity, becoming symbols of products’ attributes and characteristics due to their longevity and ability to convey knowledge, information, and ideas over time (Liang et al., 2024). Since the Industrial Revolution in 1860, global corporations, defined as enterprises or subsidiaries established by one or more countries and controlled and managed by parent companies within a unified economic entity, have proliferated for cross-border business activities. This spread led to unprecedented growth in the last century, and with economic liberalization, an increasing number of products entered Arab markets. However, these products often face a common challenge: how to accurately translate their logo visually and linguistically (Kislitsyn and Guzheva, 2024; Stashenko and Marchuk, 2022; Steblak, 2024).

Translating logos is not as straightforward as it may seem. A brand’s logo embodies its culture, which is the product of language, politics, culture, customs, and consumer psychology, all of which must be aligned with local laws and cultures (Jing, 2023; Tian and Sun, 2024). Practices have shown that translating business logos is vital to survive and thrive in Arab markets, just as in other markets. This requires understanding the social and cultural characteristics of these countries, including consumer mentality, cognitive levels, and legal regulations (Jing, 2023; Liginlal et al., 2013).

This research explores how translated international logos influence brand awareness and corporate image in the Arabian Gulf. Analyzing consumer perceptions and emotional responses evaluates logo translation as an effective branding strategy. The study provides insights for global brands to enhance their visual identity and marketing in GCC markets by examining the effects on brand recognition, recall, emotional engagement, and trust through cultural alignment.

Addressing challenges like cognitive confusion and meaning distortion, the research emphasizes the need for logos to resonate with the audience’s cultural and informational backgrounds to maintain coherence and trust. Focusing on the Arabian Gulf’s blend of tradition and modernity, the study balances global branding strategies with local cultural values. The findings will contribute to cross-cultural branding literature and offer practical guidance for marketers and brand managers to strengthen their presence and relationships with consumers in the competitive GCC markets.

2 Literature review

2.1 Brand identity

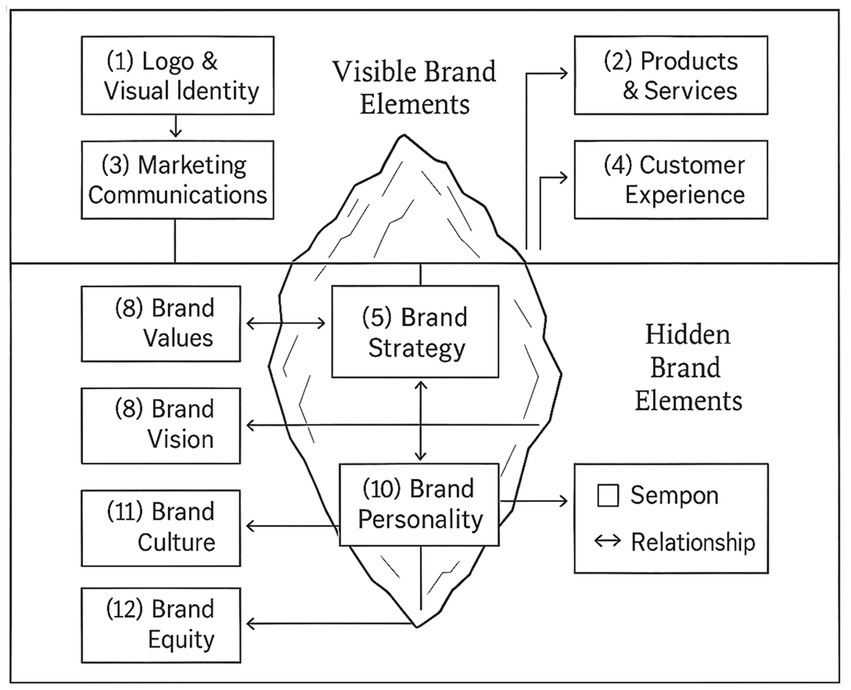

The brand identity consists of several aspects, including visual, emotional, and cultural aspects, which contribute to its uniqueness from its competitors and create a distinctive image in the minds of consumers as in Figure 1 (Rinaldi et al., 2023; Sundaresan et al., 2023; Vo, 2023). Therefore, developing and managing the brand identity strategy effectively necessitates knowing the brand’s purpose, values, principles, and beliefs that guide the brand’s actions (Rinaldi et al., 2023), which produces a compelling emotional connection with consumers who share the same values, which in turn leads to brand loyalty as well as taking into consideration the brand’s position in the market compared to its competitors and determining what distinguishes it in the minds of consumers (Choudhary and Sahu, 2023; Maksiutenko, 2024).

Brand personality includes human traits like innovative, trustworthy, and adventurous to make the brand relatable to consumers. Similarly, the brand voice, the tone used in communications, whether formal, friendly, humorous, or authoritative, should align with this personality (Jhingan, 2023; Jindal, 2023). Visual identity, including the logo, colors, fonts, and images, is key for immediate recognition and conveying the brand’s values. Consistent visual identity across all touchpoints is essential for building a strong brand image (Ali, 2024; Dai et al., 2023; Taufiq et al., 2023).

2.2 Brand culture

The most comprehensive definition of culture is an integrated system of behavioral patterns acquired by members of a society. Culture has branched into several types, such as visual and auditory culture until the modern term “brand culture” emerged and began circulating in advertising, branding, and marketing circles.

Harun et al. (2011) define Culture of Brand Origin (COBO) as a tool for assessing brand authenticity, mainly focusing on cultural factors such as language and the perception of brand name linguistics. These factors significantly impact how consumers perceive and interact with brands based on their cultural origins.

In their 2015 study, Harun et al. highlight the importance of language and linguistics in shaping consumer perceptions and purchasing decisions and the role of cultural factors in influencing consumer behavior. Similarly, Okafor and George (2016) emphasize the need to focus on brand culture, including cultural factors that play a decisive role in shaping brand identity. Understanding and leveraging these components can help organizations enhance and realize their brand value.

Schroeder (2009) focuses on the cultural foundations of brands and highlights the shift towards understanding brand value creation from the perspective of consumer response and services. He discusses elements that help identify and differentiate a seller’s products or services, including names, logos, symbols, and designs. Schroeder also examines the extent to which the emotional traits, cultural traditions, and individual images represented by these cultural elements are perceived to maximize corporate profits, retain consumers, and build a favorable reputation and image among target consumers. These elements carry corporate culture and its underlying ideas through visual stimuli.

Brand culture consists of various elements that define and shape how the brand is perceived internally and externally. It contributes to building a strong and cohesive brand identity. According to Davidson’s “Ice Theory of Branding” (Siashamsai), brand culture depends on several physical, emotional, and human factors that affect institutional reputation, in addition to the visual aspects (such as name, logo, brand identity, packaging, and social presence). These elements collectively enhance a company’s reputation and popularity and increase consumer loyalty, making brand culture a critical component for maintaining a positive public image.

The hypothesis 1 There is a positive emotional connection towards international brands with logos translated into Arabic among consumers in the Arabian Gulf region builds on brand culture theory (Schroeder, 2009) and semiotic frameworks (Visconti, 2017), which posit that logos are cultural texts embedding symbolic meanings that evoke emotional engagement. When adapted linguistically and visually, logos communicate cultural alignment, fostering stronger emotional bonds between consumers and brands.

2.3 International companies

According to the United Nations definition, global corporations are companies or subsidiaries established by one or more countries and controlled and managed by parent companies within a single economic entity for cross-border business activities (Mares, 2022). Since 1860, as a result of the Industrial Revolution, these companies have expanded and achieved unprecedented growth during the 1960s and 1970s. Advertising, in its various forms and through different tools, aims to persuade and influence consumers to increase their desire to purchase a product, service, or idea by utilizing verbal and visual elements that affect economic behavior in general and multinational companies in particular. As new markets open, these companies seek to consistently transmit their brand message with high communication frequency to maintain a positive brand impression (Fan, 2023; Shivam, 2024).

The brand has become an expression of the company’s culture, personality, and the products or services it provides, helping it define itself to customers and distinguish itself from other companies. The pursuit of excellence is increasing among multinational companies, leading them to rely on several factors, including psychological and emotional ones (Si and Li, 2023).

Studies indicate that economic globalization has contributed significantly to disseminating multinational companies’ symbols for several reasons, the most important being technological advancements in communication. This progress has resulted in the rapprochement of cultures and the convergence of visual symbols, making them a means of communication between global cultures through economic patterns, significantly impacting cultural patterns. To achieve successful cross-cultural communication, those responsible for communication must adapt to the variables in different cultures by identifying and understanding cultural differences and modifying their strategies accordingly (Alifuddin and Widodo, 2022).

Wally Olins, in his book “International Corporate Identity,” mentions several factors that affect corporate identity from an international perspective: the current market environment, the need for companies to differentiate themselves emotionally, and the influence of brand culture not only on products and services but also on environments and behavioral issues (Balmer, 2014). This aligns with Denis McQuail’s advertising process, which depends on several key points: presentation, drawing attention to new information, cultural content, and a set of values (Solík, 2014).

The volume of multinational investment projects in the Gulf countries is substantial, reflecting the region’s strategic importance and economic growth initiatives. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has committed to a 10-year investment plan worth $1 trillion to expand the tourism sector. This includes increasing hotel capacity and enhancing tourism-related infrastructure such as airports and transportation systems. Additionally, multinational companies such as PepsiCo and Aramex have moved their regional headquarters to Riyadh, taking advantage of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 plan to diversify the economy (Al Naimi, 2022; Moshashai et al., 2020).

In the UAE, Dubai remains a major hub for multinational companies. The Dubai International Chamber has a strategy to attract 50 multinational companies over the next 3 years and to support the international expansion of Dubai-based companies. Abu Dhabi announced 144 development projects in 2024 worth AED 66 billion ($17.97 billion), focusing on housing, education, human capital, and tourism. With the policy of economic openness, an increasing number of products have entered Arab markets (Mishrif and Kapetanovic, 2018). However, these products may face a common challenge: how to translate and Arabize their brands both visually and linguistically correctly. This can sometimes cause the brand to lose cohesion and unity, leading to alienation (Mehadjebia et al., 2023). Arabizing a brand is not as easy as it may seem; it involves language, politics, culture, customs, and consumer psychology, ensuring compatibility with local laws and cultures. When multinational companies have branches in America and expand to Europe, the situation is more straightforward because the primary languages, whether English or German, are written from left to right, unlike Arabic, Chinese, and Japanese, which have different writing directions and cultural nuances (Sameh et al., 2018).

Branding aims to help companies promote their products, so the brand and its “translation” should be based on consumer psychology and consider consumers’ backgrounds and requirements (He and Ma, 2017). The logo is an essential component of corporate identity that distinguishes the company or institution and conveys its personality. It is based on three essential elements: the brand, the behavior, and the institution’s understanding. Thus, institutional identity affects the cognitive awareness of the institution, enhancing its uniqueness and distinction and contributing to building its mental image.

2.4 Translation vs. localization in marketing

Translation or Arabization? Many people are confused that translation and Arabization are the same, even if they are similar at first glance. In-depth research and research reveals many fundamental differences and differences (Rachael and Mary, 2023). Translation is a conversion from one language to another to demolish the language barrier and understand the message in the closest possible sense without considering the cultural differences that enhance success (Mahmoud, 2024) and realizing the marketing message in a different country, while localization is concerned with the meanings, contents, and cultural symbols that suit a new target audience (Grami, 2019). That is, localization is modifying the consumer experience, especially the visual elements of the logo, such as images, colors, symbols, fonts, and the physical factors of the visual process. For example, the Arabic language reads from right to left, unlike English, which requires the designer to be aware of the physical and psychological factors and adapt the marketing message in terms of content and visual elements (Saleh, 2016).

De La Cova (2021) shows that the language used in a product or service dramatically affects the creation and success of a brand. Localizing a brand’s language is essential for achieving global consistency and involves addressing various translation issues at the pre-translation stage. Localization involves adapting products linguistically and culturally to target markets. This includes translating textual content and adapting non-textual content to meet cultural and regulatory requirements. Brand name translation strategies include using the original name, transliteration, or transcreation. Market research and cultural consulting are essential to achieve effective localization. Brand terminology, including product terminology, dramatically affects the brand image and must be carefully managed. Therefore, there is a necessary need to follow a unified strategy in localizing the brand language to ensure consistency and relevance in the market. Translators must be familiar with brand terminology and consult with clients to ensure alignment with their preferences and brand philosophy.

Translation shapes and enhances consumers’ perception of the brand (Massi et al., 2023). Understanding brand messages effectively and appropriately for consumers enhances authenticity and sincerity (Riefler, 2020). We find that brands of international companies with logos translated into regional languages have greater opportunities to gain the trust and loyalty of local consumers (Safeer and Liu, 2023), and the strength of the brand message is also affected by consumers’ ability to understand it easily and conveniently (Han et al., 2021). Many indicators confirm that consumers’ perception and trust in a brand are linked to their emotional attachment (Guèvremont and Grohmann, 2016). Translating the brand contributes to enhancing its credibility among consumers and increasing their confidence in it (Kirkby et al., 2023).

With China’s reform and opening-up policy, more foreign products are entering the Chinese market, but brand translation faces linguistic, cultural, psychological, and legal challenges. The Chinese language is complex and contains many homophones, which may lead to unintended translation meanings. Consumer psychology and cultural preferences must also be taken into account, and local cultural values should be respected, as in the case of Yves Saint Laurent’s “Opium” perfume, which was banned due to its association with the Opium War (He and Ma, 2017). Therefore, effectively translating brands is vital to their success in the local market. Accuracy, consumer psychology, and cultural orientation must be key factors to ensure the brand’s success. Proper translation can greatly influence the success of the brand in this market.

These concepts are equally applicable in the Gulf countries. As in China, translating trademarks into Arabic in the Gulf requires high accuracy and respect for the local culture and its values. Foreign brands must take into account Gulf consumer psychology and preferences, as well as comply with local legal requirements. Appropriate translation and cultural adaptation of brands can contribute significantly to the brand’s success in the Gulf market, ensuring wide acceptance and trust by local consumers (Kushwah et al., 2020; Lyu and Song, 2022).

Translation and Arabization are two vital elements in global marketing strategies, as they contribute to reaching a wider audience of consumers in different markets. Using local language and familiar terminology helps better understand the local market, strengthen customer relationships, and enhance brand trust. It also enhances interaction and engagement, which increases sales and engagement opportunities. This contributes to overcoming barriers of culture and communication and enables companies to build long-term relationships with customers, leading to increased loyalty and trust in the brand (Balashova and Urupa, 2024; Camankulova and Ayhan, 2020).

Jiang and Wei (2012) examine standardization across countries and continents, intending to understand how multinational companies selected from different countries use different standardization strategies in their international advertising campaigns that target two culturally different markets. Based on the standardization model developed by Wei and Jiang (2005), the study on the international advertising strategy of MNCs through the two distinct dimensions of creative strategy and implementation. Intercultural communication focuses on exchanging information between members of different cultures, with research focusing on how multinational corporations (MNCs) adapt their advertising strategies to different cultural backgrounds, specifically in the Chinese market.

Given the significant role of multinational companies in the global economy and their impact on social development and cultural values, Jiang and Wei (2012) argue that multinational companies face significant cultural differences when advertising in different countries. The study stresses that strategies Successful advertising in China requires a deep understanding of different cultural characteristics, consumer mindsets, and cognitive levels. The differences between Chinese and Western cultures are complex and involve unique consumer behaviors and specific cultural norms.

Advertising messages should be adapted to use local personalities and themes, strengthening the connection between the brand and the local audience. Multinational companies can carefully analyze the local cultural backgrounds of countries in the Gulf region (GCC), including studying customs, traditions, social values, and language. Including incorporating elements of Gulf daily life, such as traditional costumes, local foods, and social customs, into advertisements to enhance engagement and acceptance (Sun, 2024). Gulf customs and traditions should be respected in advertising campaigns, such as modest dress and high regard for family and hospitality. Important social issues such as youth empowerment, education, and public health should also be considered in advertisements (Zhou, 2023). Companies must integrate localization with globalization to maintain the consistency of the global brand while adapting messaging to fit the local context. This can be achieved by translating the logo and brand to reflect local values and enhance passion for the brand (Garg, 2023). In addition, the study of intercultural communication can be used to understand how messages can be effectively conveyed between different cultures, which enhances the Gulf audience’s understanding of advertising messages and increases the effectiveness of campaigns. By following these strategies, multinational companies can succeed tremendously in their Gulf region advertising campaigns (Abdel Rahim, 2023).

Cultural adaptation is considered one of the most important factors for the success of visual communication in general and the logo in particular. It is the process of modifying the global logo to be compatible with the elements of regional culture for markets with distinct characteristics while preserving its basic identity. For example, several factors contribute to this. Colors and visual elements are a symbolic language specific to each society. It interacts with it, and according to many cultural components, the color white in Western thought is a symbol of purity, while in some Eastern cultures, it is a symbol of mourning (Sun, 2024). Likewise, the owl symbolizes wisdom in Western countries, while in Arab countries, it symbolizes pessimism. At the same time, the choice of typography must be compatible with methods of reading, especially with People of Eastern cultures who write and read from right to left or from top to bottom. The Translation Studies Dictionary also defines cultural adaptation as a process of adaptation between disparate cultures with differences (Balashova and Urupa, 2024). Cultural adaptation has become extremely important in the modern era, especially after globalization, the spread of social media, and the increase in international companies. The cultural adaptation process must include collecting information, designing, testing, developing, and final design (Barrera et al., 2013).

Much research has focused on the psychological challenges facing consumers’ behavior in the cultural adaptation process, which Molinsky (2007) referred to. In the name of cross-cultural switching, cultural adaptation extends beyond translation to understanding the target audience’s cultural nuances, beliefs, and values to design interventions accordingly Kayrouz and Hansen (2020) point out that cultural adaptation is more comprehensive than translation. The sending company’s awareness of the target audience’s cultural and cognitive differences and diversity. Translating the logo and brand is linked to semantics, which is linked to many human sciences, such as marketing, psychology, and linguistics, reflected in the perception of the logo of international companies in different cultural and linguistic environments. Glukhova (2021) believes that there are two methods of cultural adaptation: the first is cultural adaptation of value, through adapting the message to the values of the target culture, and the second is cultural adaptation to the context of modifying brand communications to comply with the specific contextual understanding and cognitive standards of the target culture. According to Chan (2018). The cultural adaptation of the logo is the process of formulating cultural differences so that the international is accepted locally, and cultural adaptation contributes to the effectiveness of the communication process between companies and individuals with target cultures (Kayrouz and Hansen, 2020).

This hypothesis H2 is grounded in localization theory, which emphasizes adapting brand identities to align with the cultural expectations of target audiences (Glukhova, 2021). It also draws on the Culture of Brand Origin (COBO) framework (Harun et al., 2011), which posits that brands localized to reflect the cultural values of their markets foster deeper resonance and engagement. By translating logos into Arabic, global brands signal cultural respect and integration, increasing their perceived relevance and appeal among consumers in the Arabian Gulf.

2.5 Semiotics in marketing

Visconti (2017) explores the use of marketing semiotics to create brand value by utilizing cultural studies and semiotic theories. He argues that markets are not just economic systems but also places for producing and circulating meaning, which calls for understanding and using the cultural symbols and meanings surrounding brands. This approach invests in enriching brand connotations to improve financial performance and position the brand in its cultural environment. It also focuses on how brands exist in cultural worlds, benefiting from existing cultural meanings and transforming them to become part of the cultural structure of the market. It is therefore important to conduct semiotic ethnography and understand sign systems, consumer behavior, and cultural translation of brand messages.

Bobrie (2018) focuses in his study on the semiotic analysis of the brand and how the visual representation of the brand creates meaning and influences consumer perceptions, going beyond the traditional focus of exploring complex semiotic structures with an emphasis on the brand that includes the entire visual and linguistic structure associated with the product, creating a narrative for the consumer. The study also relies on semiotic tools to analyze the brand as an organized set of linguistic and non-verbal iconic elements to understand how the brand constructs meaning using concepts such as the level of immanence, iconic text, narrative actors, and narrative schema.

A brand is a semiotic object consisting of different signs and narrative structures that create a cohesive, meaningful narrative. Different visual elements play similar roles for the characters in the story. For example, in the case of Nestlé’s low-fat candy brand, various elements such as the Nestlé and Svelties brands and visual motifs create a story about health, taste, and style. These elements contribute valuable insights into how a brand builds meaning, influences consumer perceptions, and creates more effective and differentiated branding strategies (Lelis and Kreutz, 2023; Wei and Tirakoat, 2024).

2.6 Brand awareness

Brand awareness is the ability of consumers to recognize or remember a brand when thinking of a particular product category and to get comfort when that name is mentioned. It motivates the target audience to be interested in and learn about the brand’s products or services (Kotler and Keller, 2016). According to Hutter et al. (2013), brand awareness can be created through numerous media outlets to create a sense of familiarity among the audience.

According to Dewi and Jatra (2018), brand awareness is the ability of different types of audiences, such as current or potential customers, to recognize and remember the brand in their minds. Since brand awareness is the ability of consumers to remember and recognize it, according to Upadana and Pramudana (2020), consumers prefer to buy a product with a brand that is already known or remembered, so the easier the brand is to remember, the higher the brand awareness. Research also indicates that brand awareness relies heavily on logos, which helps companies stand out from competitors and build a strong corporate identity (Van Riel and Van Den Ban, 2001). In a study on the impact of logos on organizational performance, the results showed that logos contribute to improving performance by enhancing brand awareness and purchasing intentions among consumers (Girard et al., 2013). The results of the research conducted by Parmar (2019) who found that brand awareness had a significant positive effect on purchase intention. Brand recognition is crucial at the point of purchase, where a visual image such as a logo elicits a response (Girard et al., 2013). In this context, logos play a key role in reminding the brand and ensuring it remains at the forefront of the audience’s thoughts (Herskovitz and Crystal, 2010).

On the other hand, studies support that brand awareness depends not only on the logo but also on other aspects such as brand names, verbal slogans, and colors. This harmony between visual and textual elements enhances cohesion in the brand identity and makes it more distinctive (Henderson et al., 2003). Research also shows that changing a logo in line with cultural shifts can enhance local audience receptivity and emotional connection to the brand (Peterson et al., 2015).

Four levels define brand awareness: brand awareness, brand recognition, brand recall, and top of mind. Effective branding strategies, such as visual slogans, verbal slogans and brand names, are pivotal in achieving higher brand awareness. Studies show that well-designed logos aid quick recognition and brand recall, especially for products with low involvement (Kohli and Suri, 2002). Logos should be distinctive, memorable, and easily associated with the brand (Mulyani, 2017). In the Arabian Gulf region context, translating logos to reflect cultural and linguistic preferences can significantly enhance brand recognition and recall. For example, a study on Petra Kharisma Abadi (PeKA) showed that a clear, culturally appropriate logo significantly improved brand recognition among the target market (Pribadi, 2022). This emphasizes the importance of culturally appropriate branding strategies in increasing brand awareness and a stronger company image. Translating international logos to fit local cultural contexts can significantly impact the Arabian Gulf region’s brand awareness and company image. By adopting culturally sensitive branding strategies, companies can enhance their visibility and reputation and foster stronger connections with the local market.

The hypothesis H3 Translating international logos into Arabic will significantly improve brand recognition is informed by cognitive processing theories (Kahneman, 2013; Kayrouz and Hansen, 2020), which highlight that familiar linguistic cues reduce cognitive load, enhance encoding, and facilitate memory retrieval. By providing culturally and linguistically familiar visual cues, translated logos are more easily recognized and recalled by consumers.

2.7 Corporate images

Many studies and literature define a corporate image as the perception that the various types of public have about the company, which is formed according to its actions and the communications it provides to its audience. It includes many elements, including brand identity, which includes the visual and verbal elements that define the brand, such as logos, colors, and typography. The public’s company image is formed according to their subjective impressions. Kim and Jung (2013) defined company image as a positive or negative attitude consisting of total subjective beliefs, feelings, impressions, ideas, and knowledge about the company.

Corporate image consists of how customers perceive a company and its values. A localized logo that aligns with local culture can enhance a company’s image by demonstrating cultural sensitivity and inclusivity. This is crucial in the Arabian Gulf region, where cultural values play a large role in consumer behavior. Tulasi (2012) explains that maintaining or improving brand awareness requires continuous efforts to ensure quality and functionality, which is reflected in the company’s brand logo and public image. Gürhan-Canli and Batra (2004) investigated the moderating role of perceived risk when corporate image influences product evaluations, highlighting the importance of managing perceived risks associated with corporate image. At the same time, Park and Lee (2018) see this as a positive or negative impression of the company among its employees and audience. At the same time, Aaker (1991) sees corporate image as a set of factors linked to brand memory. Grund (1996) believes a positive company image can lead to a strong reputation. It is a combination of consumer insights and beliefs about the brand (Campbell, 1998). A company’s image is vital because it influences customer loyalty, investor confidence, and the overall market situation, affecting its success and growth.

In addition, research highlights the importance of logos in building a company’s image. Logos are a formal visual representation of a company or brand name and an essential component of all brand identity programs (Schechter, 1993). Localized logos that align with local culture can enhance a company’s image by demonstrating cultural sensitivity and inclusivity, enhancing customer trust and initial commitment (Rafaeli et al., 2008). Research has also indicated that logos can contribute to building a brand’s personality, leading to the continuity of the brand’s overall message (Herskovitz and Crystal, 2010). However, studies have shown that redesigning logos can be risky, as it may negatively impact customers who are highly committed to the brand (Walsh et al., 2010).

Corporate images are crucial in many important matters, such as hiring decisions, customer loyalty, and consumer trust. It was presented by Shee and Abratt (1989) presented a different approach to the process of managing corporate image effectively. This opinion is confirmed by Gatewood et al. (1993) by the association between company image and initial decisions to choose a job and attract potential employees. Much international marketing research believes that global brands derive their value from various factors, including features and benefits, while Kotabe and Helsen (2010) see that consumer culture plays an active role in shaping the value of the brand, and Steenkamp (2014) adds that foreign consumer culture plays a differential value for brands. Globalism. Thus, the hypothesis H4 Translating logos into Arabic enhances the concept of professionalism and reliability of international brands in the Arabian Gulf region is grounded in Actor-Network Theory (Latour, 2005) and corporate image literature (Harun et al., 2015), which suggest that brand meaning emerges from the interplay between corporate identity, cultural artifacts, and consumer interpretation. Translating logos into Arabic functions as a strategic signal of professionalism, trustworthiness, and commitment to the local market.

2.8 Brand and identity management

Brand management and global logo translation are deeply connected to building and strengthening brand identity in different markets. Brand management is a series of ongoing strategies and techniques to develop, maintain, and improve a brand’s image and reputation in the market, aiming to increase brand awareness, enhance customer loyalty, and increase sales growth. This includes communicating with the brand through various marketing channels (advertising, social media, public relations, and content marketing) to reinforce the brand message and interact with the target audience.

Effective brand management creates a strong emotional connection with customers and distinguishes the brand from competitors. Wood (2000) highlights the importance of brands as the most important corporate assets that must be managed effectively, while Mosley (2007) emphasizes the role of brand management in brand-led culture change and customer experience management. Morgan et al. (2003) discuss the unique challenges that can be overcome through stakeholder partnerships and non-traditional media, while Burmann and Zeplin (2005) present a model of internal brand management focusing on brand commitment through human resource management, communication, and leadership.

Brand management influences the marketing process by creating and evaluating brand value, as Kapferer (1992) points out. This strategic management requires creating, developing, maintaining, and enhancing a brand’s identity, reputation, and market position through actions and decisions to build a strong and positive brand perception among consumers, ensure consistent messaging, and enhance customer loyalty to drive business growth and value. When it comes to translating global logos, this process requires great precision to ensure that the message carries the same value and meaning in the new market. Effective translation addresses cultural and linguistic challenges to ensure the logo fits the local context. This includes language localization and respect for cultural values and traditions (Sun, 2024). Proper translation can contribute significantly to a brand’s success in international markets, as it integrates with brand management strategies to enhance its global image, reputation, and consistency (Tian and Sun, 2024).

2.9 Consumer behavior in Arabian Gulf regions

It is widely known that the Arabian Gulf countries have become one of the most important shopping destinations in the world. Consumers in the United Arab Emirates, for example, want excellent service and feel a personal appreciation for a global brand, which makes it imperative for owners of international companies to consider carefully. The UAE market’s unique demographic trends and how to adapt their strategy to target and engage with specific consumer groups. Many consumers spend a lot of money (Kazim, 2018; Kushwah et al., 2020; Saud Alfayad, 2021).

Consumer behavior in the UAE is characterized by difficulty convincing customers to gain their loyalty. 75% of customers prefer to shop from a single-brand rather than a multi-brand website because they believe that will ensure the best possible customer service. However, expectations go beyond just the ordering, delivery, and returns process, with 65% of customers expecting brands to reach out to them personally and treat them as individuals, which is 9% more than the global average expected personal service. Offering exclusive rewards and benefits attracts 69% of Emirati shoppers and encourages 43% of them to spend more and more frequently by using a personal shopping advisor (Kazim, 2018; Khalif and Rossinskaya, 2024; Lelis and Kreutz, 2023; Tian and Sun, 2024).

The UAE is a ripe market for luxury brands, with tourism and an affluent population being the main drivers of the sector. Dubai alone accounts for 30% of the luxury products market in the Middle East. One study showed that UAE citizens spend about 30% of their monthly salaries on luxury goods. To attract this luxury segment, emphasis can be placed on quality, craftsmanship, and brand positioning to help differentiate and increase local engagement (Kazim, 2018). The UAE also recently ranked eighth in the list of countries whose customers deal with mid-market brands. In addition, having an established global brand gives a considerable advantage, as foreign products make up 58% of total purchases in the UAE (Genç, 2019).

The UAE has a unique demographic, with only 27.8% of the population being female. It may seem like the path to success exclusively targets males, but that would be a missed opportunity as women influence 80% of all purchases in Dubai. Regardless of the product or brand, communicating and engaging the female segment will likely be crucial to UAE marketing strategies. It is also worth noting the purchasing behavior of women in the Emirates, as Emirati women spend 43% of their income on fashion, three times what expatriate citizens spend (Zhang, 2024). A third of these Emirati women spend more than 60% of their monthly income shopping. In addition to gender influences in consumer behavior, the UAE is a unique market comprising 88.5% expatriates and over 200 nationalities. The Jollibee brand embodies the importance of targeting the expatriate community to achieve success in the UAE, as the Filipino fast-food chain has taken the UAE by storm by focusing heavily on the expatriate community (Xu et al., 2024).

On the other hand, Chaudhary et al. (2018) explore the active role of children and young people in family purchasing decisions, seeing gender as an important element in this context. Boys influence decisions about toys and electronics, while girls generally influence family purchases. The emergence of non-traditional families and cultural differences also affect the dynamics of family decision-making. Television advertising and online content are important sources of information for children and young people, influencing their consumption behavior. Accordingly, global companies must consider the growing importance of young consumers in family purchasing decisions and provide insights for marketers targeting this demographic in the GCC region.

According to mapsofarabia.com, international brands have a special place in the Arab Gulf countries, as Arabs prefer the brands of international companies in various fields, including cars, clothing, and smartphones, because they are associated with quality and luxury. The site believes that emotions towards the brand play a pivotal role in the purchasing decision, followed by practical application. Shoppers also care about a brand’s stance on sustainability and social issues, with 87% of consumers in the UAE and 88% in Saudi Arabia indicating that they care about at least one sustainability factor while online purchasing in 2020. In contrast, Khraim (2011) found that those with higher educational levels (undergraduate and postgraduate) prefer international brands. Young female consumers are also highly influenced by advertising and prefer affordable cosmetics. At the same time, older consumers and those with higher education levels are more brand-aware and less influenced by advertising.

Bachkirov (2019) explores the impact of national culture on organizational buying behavior (OBB) in the Arabian Gulf and the relationship between OBB and cultural characteristics. He emphasizes the need for international companies to understand local cultural characteristics to enhance the effectiveness of complex purchasing processes. It also points to the importance of social influences and cultural considerations in organizational buying behavior, providing a framework for understanding the unique dynamics of emerging markets in the Arabian Gulf. Kushwah et al. (2020) confirm that understanding the local culture of the Arab Gulf countries contributes to shaping consumers’ perceptions of brand identity in the region. The researchers urge global companies to develop branding strategies aligned with local culture, emphasizing the importance of incorporating cultural factors into branding efforts. The findings suggest that a one-size-fits-all approach may not be practical and that brands must tailor their strategies to the local cultural context.

In another study, Vadakepat (2013) identified the impact of multicultural factors on consumer behavior in the United Arab Emirates. As the UAE market becomes globalized, the study aims to understand how consumers from different cultural backgrounds behave when purchasing durable and non-durable goods. Consumers’ pre-purchase behavior varies according to their culture; Westerners focus on brand reputation and promotion, while Arabs focus on design, and Asians focus on price and quality. Family influences vary significantly during the purchasing process; Westerners and Asians involve husband and wife in decision-making, while Arabs consider the opinions of children and extended family. Satisfaction levels differ between cultural groups in post-purchase behavior, with quality being a satisfaction factor common to all groups. The study confirms that brand and design are crucial to Arabs and highlights cultural differences in preferences for local versus global brands. Therefore, marketers need to understand the cultural context of their target audience to develop effective marketing strategies. The research suggests that a one-size-fits-all approach may not be practical in such a diverse market and that personalization is key to meeting the diverse requirements of consumers from different cultural backgrounds. Parahoo and Harvey (2014) points out that global companies with products in or targeting the Gulf region should not rely solely on traditional Western models but must consider religious, social, and cultural context factors to meet customer expectations effectively.

2.10 Case studies and comparative analyses

The visual examples presented in the Case Studies section (e.g., Applebee’s, FedEx, Baskin Robbins, and others) were not solely illustrative but were also used as the primary stimuli in the survey. Participants were shown either the original English version or the translated Arabic version of these logos. This ensured that their responses reflected authentic perceptions of real-world brand logos adapted for the Gulf market, rather than abstract or hypothetical designs. Whereas Gani et al. (2014) explore the effect of typography on the ability to remember logos. The research focuses on the physical aspects of typography, including condition, weight, contrast, width, positioning, and style, and their impact on logo recall. All six typography categories showed significant positive relationships with logo recall. It turns out that large letters, bold weight, strong contrast, medium width, Roman stance, and neutral styles are most important in helping logo recall. Typography is crucial in logo design, as it dramatically affects logo recall.

• Applebee’s. logo (available at: https://www.applebees.com & https://www.instagram.com/p/CDXJGNEhUp1/) consists of a red and green apple icon with a serif font logotype. In the Arabic translation, the font appeared inconsistent, with varying thicknesses and spacing issues that disrupted visual harmony.

• AQUA. fashion brand (available at: https://www.aquastyle.com.kw & https://www.aquafashion.com/contact?srsltid=AfmBOoq03S1RpOCirE24CbY9UbGmvy9Yhvj3lOs6BYjtbLZwmpWjC2sq) attempted to Arabize its logotype by adding horizontal lines to connect both language versions. However, this resulted in significant readability challenges, where consumers could only recognize part of the name.

• Baskin Robbins. logo (available at: https://www.baskinrobbinsmea.com & https://www.flickr.com/photos/38242198@N06/13096413915), an international ice cream chain, achieved a successful localization by transforming the “B” and “R” into a visually rhythmic Arabic font that maintained brand consistency and readability.

• FedEx. logo (available at: https://www.fedex.com & https://www.tumblr.com/solnechniy-lis-blog/144081680181/fedex-logo-and-its-struggles-in-a-foreign) is known for its hidden arrow, symbolizing speed. In the Arabic adaptation, the designer attempted to preserve the arrow by combining the “K” and “X.” However, the result reversed the arrow’s direction, which conflicted with natural right-to-left reading flow and disrupted the intended meaning.

• Hamleys. toy store logo (available at: https://www.hamleys.com & https://global.razor.com/middle-east/news/vendor/hamleys/) maintained its freestyle typeface in Arabic, but the lack of horizontal lines and weak diacritics reduced readability, making the brand less accessible to local consumers.

• Jotun. paint company logo (available at: https://www.jotun.com & https://ariana-poshesh.com/home/) retained its visual identity, but the Arabic transliteration altered the pronunciation, resulting in a mismatch with the company’s original Norwegian brand name.

• Koton. The clothing brand (available at: https://www.koton.com & https://ads4tr.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Koton-arabistan.jpg) replicated the English font style for Arabic adaptation. However, the integration of the cotton flower icon with Arabic script created spacing and readability issues.

• M.A.C Cosmetics. Cosmetics logo (available at: https://www.maccosmetics.com & https://maithaalmagoodi.wordpress.com/english-arabic-logos/) is globally recognized for its minimalist three-letter format. In the Arabic version, attempts to replicate the English letters led to distortions, forming “MAK” instead of the original acronym, thereby altering brand identity.

Overall, these case studies highlight the delicate balance required in translating logos into Arabic. While some brands (e.g., Baskin Robbins) succeeded in preserving visual identity and readability, others (e.g., FedEx, AQUA, and M.A.C) faced challenges that risked undermining cultural adaptation and consumer trust.

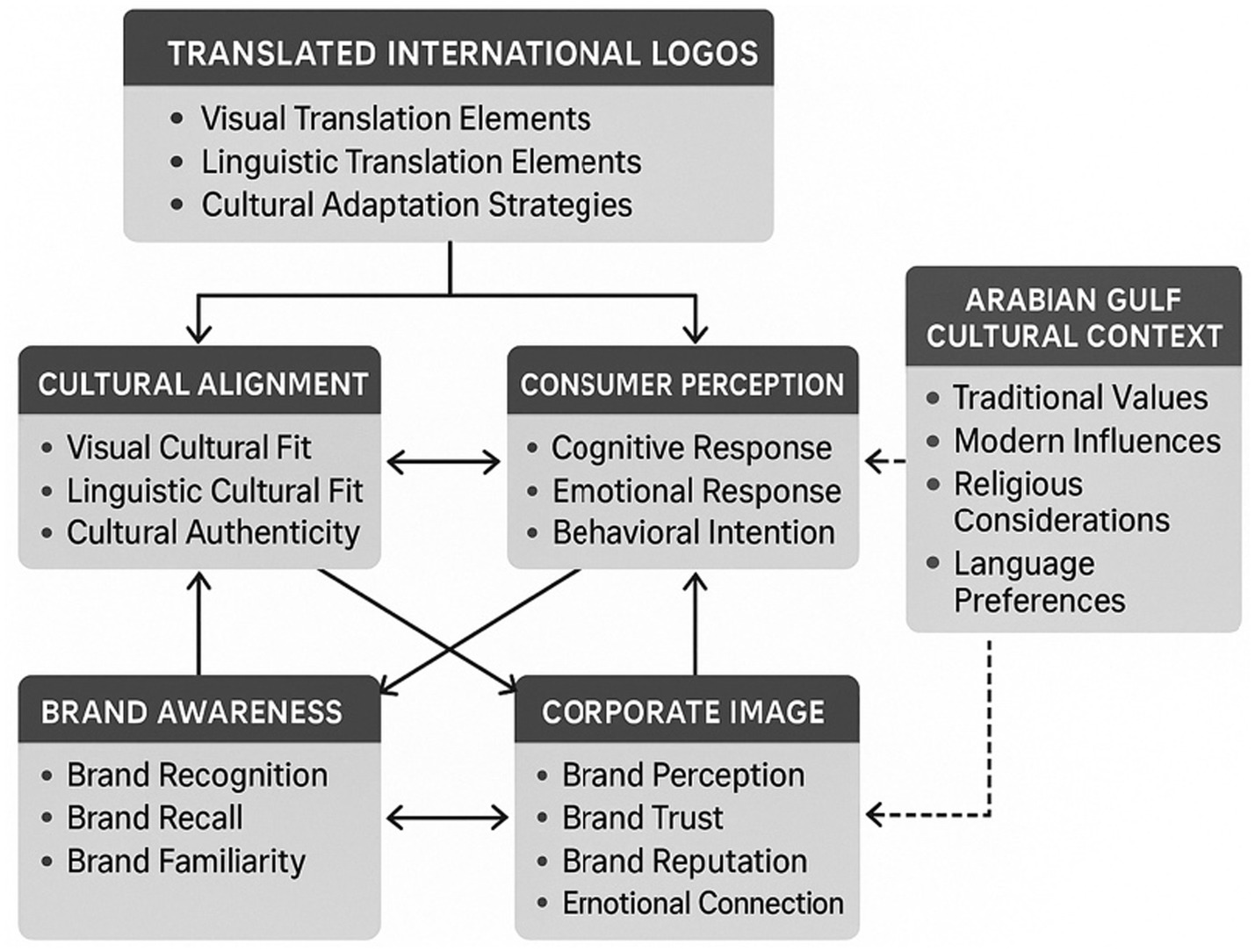

3 Conceptual framework

Based on the reviewed literature, the following conceptual framework (Figure 2) illustrates the hypothesized relationships between brand culture, semiotics, localization strategies, and cognitive processing theories as they inform the four proposed hypotheses (H1–H4). These relationships collectively explain how translating international logos into Arabic can influence emotional engagement, cultural relevance, brand recognition, and ultimately impact brand awarenessand corporate image in the context of the Arabian Gulf.

The reviewed literature underscores that logos function as semiotic carriers of meaning, reflecting both global brand identity and local cultural expectations (Schroeder, 2009; Visconti, 2017). Furthermore, cross-cultural branding research highlights the strategic importance of linguistic and cultural adaptation in enhancing consumer engagement and trust (Glukhova, 2021; Harun et al., 2011). Drawing on semiotic theory, brand culture frameworks, and cross-cultural branding studies, this research proposes the following hypotheses regarding the influence of translated logos on brand awareness and corporate image in the Arabian Gulf.

4 Methodology

4.1 Hypothesis

Building on previous research in brand culture (Harun et al., 2011; Schroeder, 2009), semiotics in marketing (Visconti, 2017), localization strategies (Glukhova, 2021), and cognitive processing models (Kahneman, 2013), it becomes evident that logo translation is not merely a linguistic process but a strategic act with cultural, cognitive, and emotional implications. These theories collectively suggest that adapting international logos to Arabic has the potential to enhance emotional engagement, cultural relevance, recognition, and perceptions of professionalism. From this synthesis, the following hypotheses are formulated:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): There is a positive emotional connection toward international brands with logos translated into Arabic among consumers in the Arabian Gulf region. (Derived from brand culture theory and semiotic frameworks, which posit that linguistically and visually adapted logos foster stronger emotional bonds with consumers).

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Global brands with logos translated into Arabic are perceived as more culturally relevant and engaging by consumers in the Arabian Gulf region. (Grounded in localization theory and the Culture of Brand Origin (COBO) framework, emphasizing that culturally adapted brand identities foster deeper consumer resonance).

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Translating international logos into Arabic significantly improves brand recognition among consumers in the Arabian Gulf region. (Informed by cognitive processing theories, which highlight that familiar linguistic cues reduce cognitive load and enhance memory encoding and retrieval).

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Translating logos into Arabic enhances perceptions of professionalism and reliability of international brands in the Arabian Gulf region. (Based on Actor-Network Theory and corporate image literature, which suggest that translated logos function as strategic signals of professionalism and commitment to the local market).

4.2 Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in compliance with ethical standards, including the Declaration of Helsinki, to ensure the protection of participants’ rights and privacy. Ethical approval was secured from the Research Ethics Committee of Ajman University under approval number “Ma-F-H-7-Jan “on “7/1/2025.” During the survey period from “7/1/2025″ to “15/1/2025″ participants provided digital informed consent after being thoroughly informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, and significance. They were assured of their right to withdraw from the study at any point without any negative consequences. All collected data were anonymized to maintain confidentiality and protect personal information.

4.3 Study setting and participant demographics

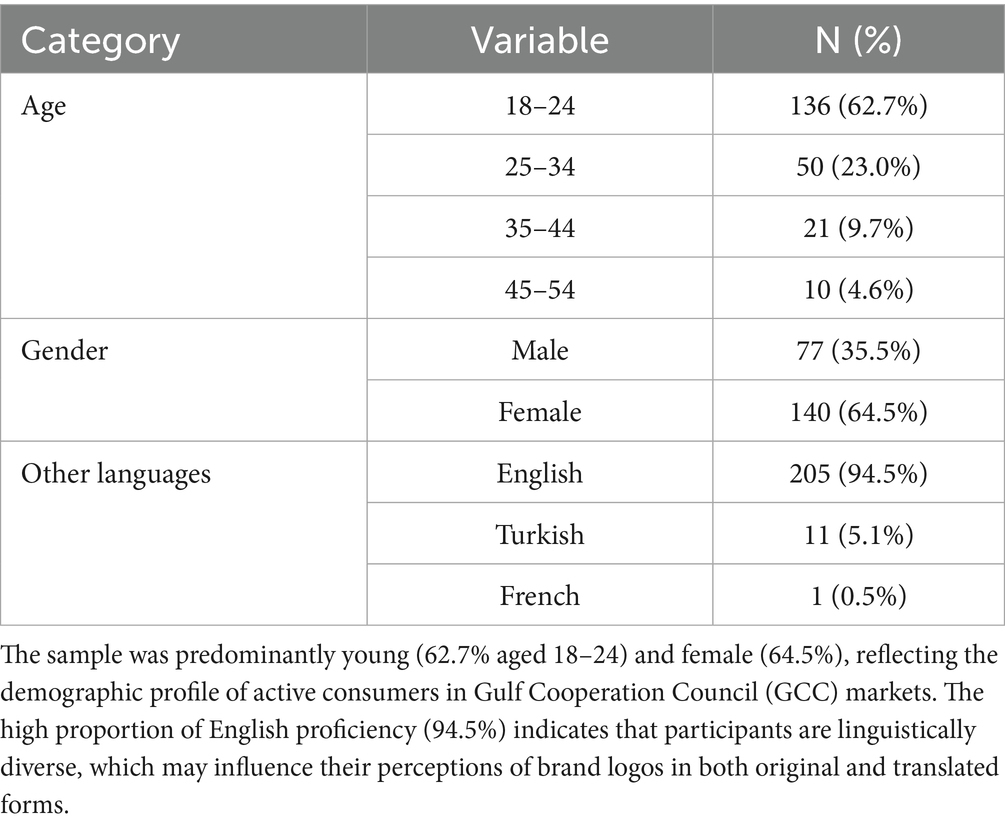

This cross-sectional study is set in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, focusing on a diverse demographic of consumers utilizing convenience sampling. The study area is characterized by its rapid economic growth and a high prevalence of international brands, offering a unique context for exploring how translated global brand logos influence brand awareness and corporate image. The number of participants in this study was 217, and they were selected for their engagement with international brands and varying backgrounds to provide a comprehensive view of consumer perceptions within this culturally rich and economically vibrant region.

4.4 Measurement instrument

Google Forms was employed as a digital method for gathering key demographic information, language proficiency, and perceptions regarding translated global brand logos from participants in the GCC. The survey included demographic queries about age and gender and language proficiency beyond Arabic, such as English, German, French, and Turkish. Additionally, participants responded to a series of statements concerning their perceptions of translated logos using a Likert scale ranging from 0 (“Never”) to 4 (“Always”). These statements explored various aspects such as brand recognition, trust, emotional connection, visual harmony, and cultural appropriateness of the logos when translated into Arabic.

4.5 Procedure

Participants were invited to complete an online survey administered via Google Forms, which was accessible across Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. The survey included a set of international brand logos in their original English versions and their translated Arabic versions, serving as visual stimuli for the study. To minimize potential bias, each participant was randomly assigned to view either the original or the translated version of a logo, but not both, ensuring independent assessments of each logo type.

The logos were presented one at a time, accompanied by statements assessing emotional connection, cultural relevance, brand recognition, and perceptions of professionalism. The order of logo presentation was randomized to reduce order effects and enhance the validity of responses.

The estimated completion time for the survey was 8–10 min, including demographic questions and perception ratings. All responses were collected anonymously through the Google Forms platform, ensuring confidentiality and adherence to ethical research practices.

4.6 Data analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 27.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations) were used to summarize participant demographics and responses regarding perceptions of translated logos.

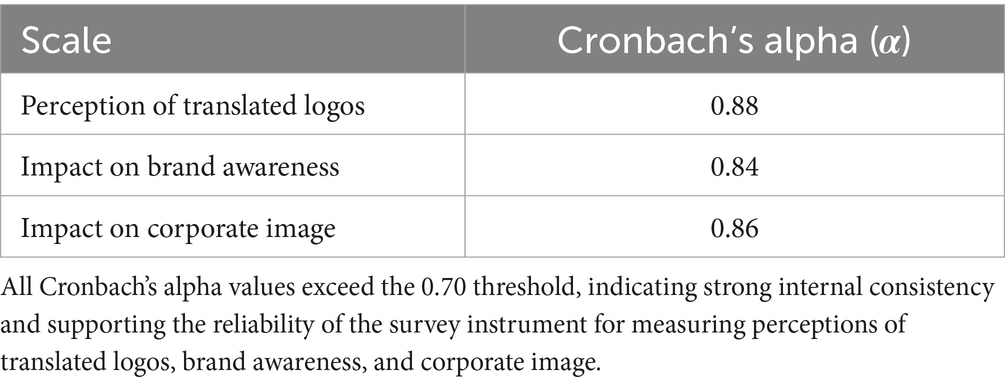

4.7 Reliability analysis

To ensure the internal consistency of the measurement instrument, Cronbach’s Alpha was computed for each scale. The results indicated high reliability across all constructs (Table 1), exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70 (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994).

4.8 Justification for statistical tests

The Shapiro–Wilk test revealed that the data for key variables significantly deviated from normal distribution (p < 0.05). Consequently, non-parametric tests were selected for group comparisons. Specifically, the Mann–Whitney U test was employed to compare two independent groups (e.g., gender), while the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for variables with more than two groups (e.g., age categories). These tests were chosen over parametric alternatives, such as ANOVA, due to their robustness for ordinal data and non-normally distributed samples.

4.9 Inferential analyses

Spearman’s rank-order correlations were used to assess associations between demographic variables and perceptions of translated logos. Multiple linear regression models were conducted to examine the predictive relationships between perceptions, brand awareness, and corporate image outcomes. All analyses were performed at a 95% confidence levelwith a significance threshold of p < 0.05.

5 Results

5.1 Demographic characteristics

The demographic breakdown of the survey respondents is seen in Table 2. The age distribution is skewed towards younger participants, with a majority of 62.7% falling within the 18–24 age bracket, amounting to 136 individuals. This is followed by those aged 25–34, representing 23.0% or 50 respondents. The 35–44 and 45–54 age groups are less represented, comprising 9.7% (21 participants) and 4.6% (10 participants) respectively.

Regarding gender, the survey had more female participants than males, with females making up 64.5% (140 individuals) and males 35.5% (77 individuals). This suggests a higher engagement or interest among females in the survey topics.

Regarding linguistic proficiency, the vast majority of respondents, 94.5%, reported English proficiency, translating to 205 individuals. Turkish speakers constitute a smaller fraction, 5.1% or 11 respondents, and only one participant, representing 0.5%, reported fluency in French.

5.2 Response summary and normality

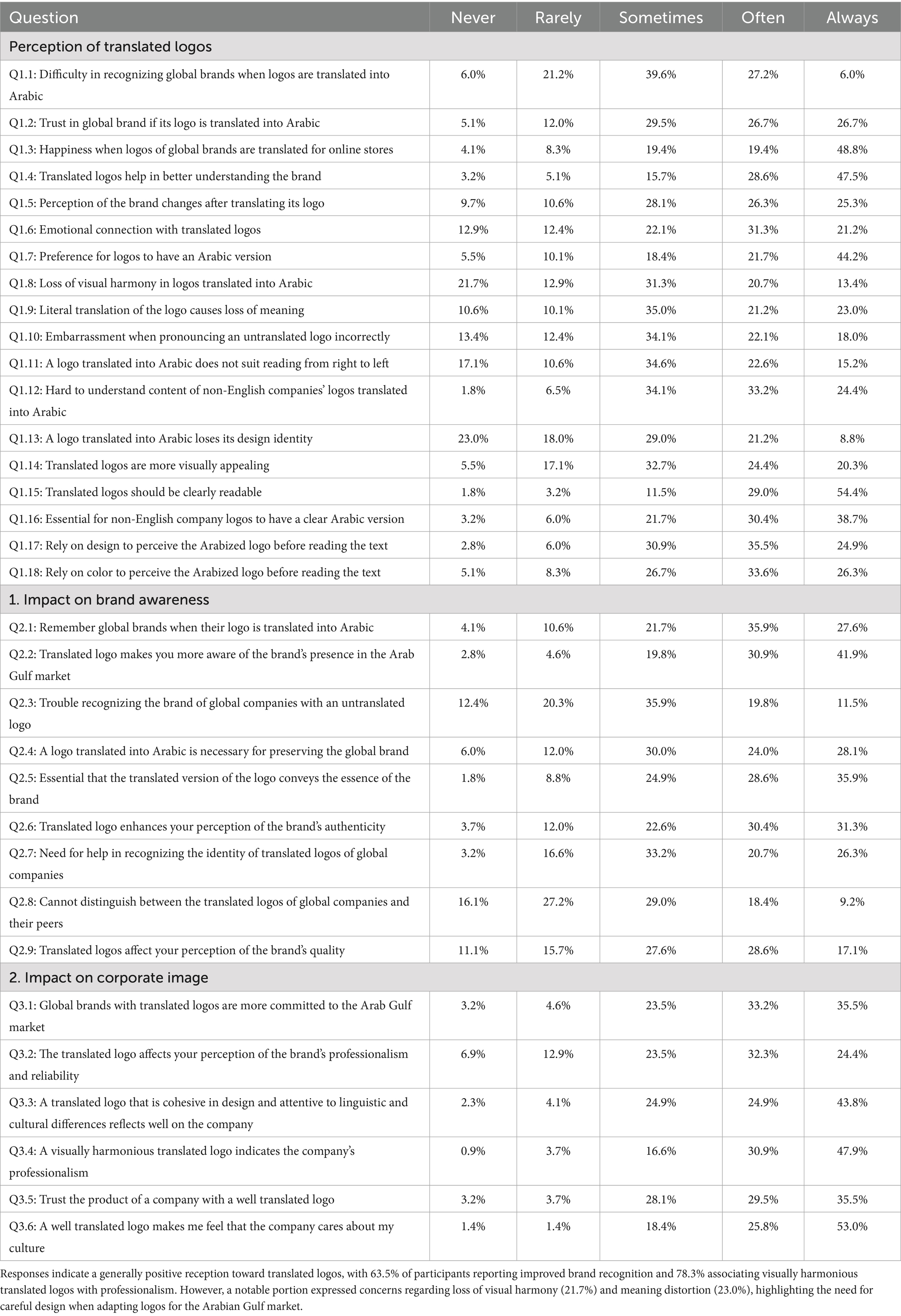

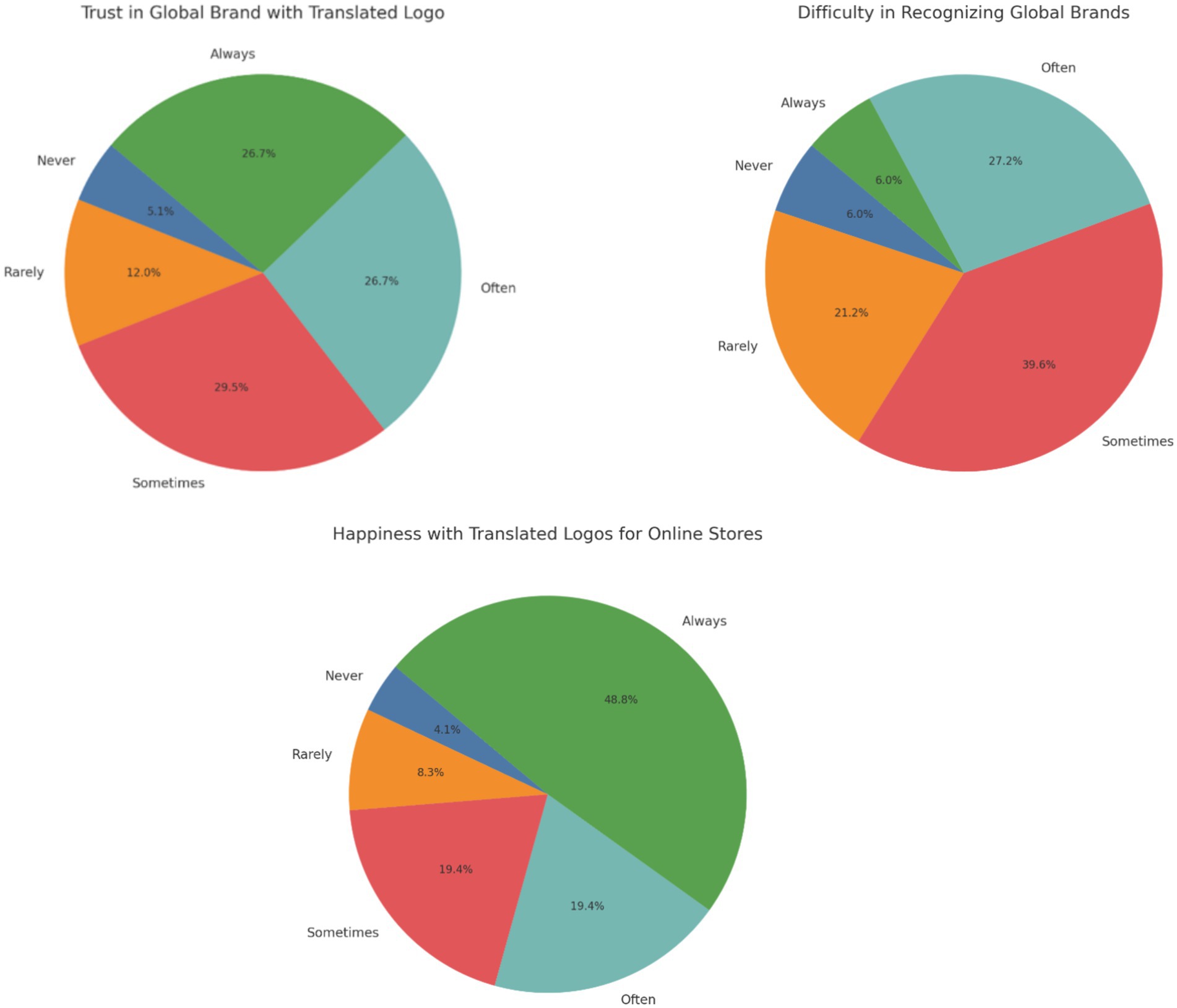

Table 3 and Figure 3 explores various perceptions towards translated logos among participants, highlighting different aspects of brand interaction when logos are translated into Arabic. Across the questions, it is apparent that emotional and cognitive responses to logo translation vary. For instance, a considerable portion of respondents, 39.6%, sometimes find it difficult to recognize global brands when their logos are translated into Arabic (Q1.1), while 26.7% trust these brands often or always (Q1.2). A strong positive response is noted in Q1.3, where 48.8% of participants feel happy always when logos are translated for online stores.

Similarly, nearly half (47.5%) believe that translated logos aid in better understanding the brand often or always (Q1.4). Emotional connection (Q1.6) and preference for an Arabic version of logos (Q1.7) are also notable, with 21.2 and 44.2%, respectively, feeling strongly about these aspects. However, concerns about loss of visual harmony (Q1.8) and original meaning (Q1.9) are also significant, with 21.7 and 23.0%, respectively, feeling that these are often or always issues.

As for brand awareness, translated logos seem to enhance brand recall and market presence awareness in the Arab Gulf significantly, as seen with 63.5% combining the often and always categories in recognizing global brands (Impact on Brand Awareness, Q2.11). However, the data also shows challenges, such as difficulty in distinguishing between translated logos and their global counterparts (Q2.8), where 47.6% sometimes or rarely can make the distinction.

Corporate image is perceived positively when logos are translated thoughtfully. A significant 68.7% feel that a well-designed, culturally attuned translated logo reflects positively on the company’s commitment to the Arab Gulf market (Impact on Corporate Image, Q3.3). Moreover, 78.3% associate a harmonious translated logo with company professionalism (Q3.4).

As for normality, the Shapiro–Wilk test results for perceptions and impacts related to translated logos into Arabic indicate deviations from normality across all categories. For perception, the test rejects normality (statistic = 0.979, p = 0.002). Similarly, the impact on brand awareness shows non-normality (statistic = 0.984, p = 0.014). The impact on corporate image also strongly rejects the normality assumption (statistic = 0.944, p = 0.000).

5.3 Participant characteristics scoring

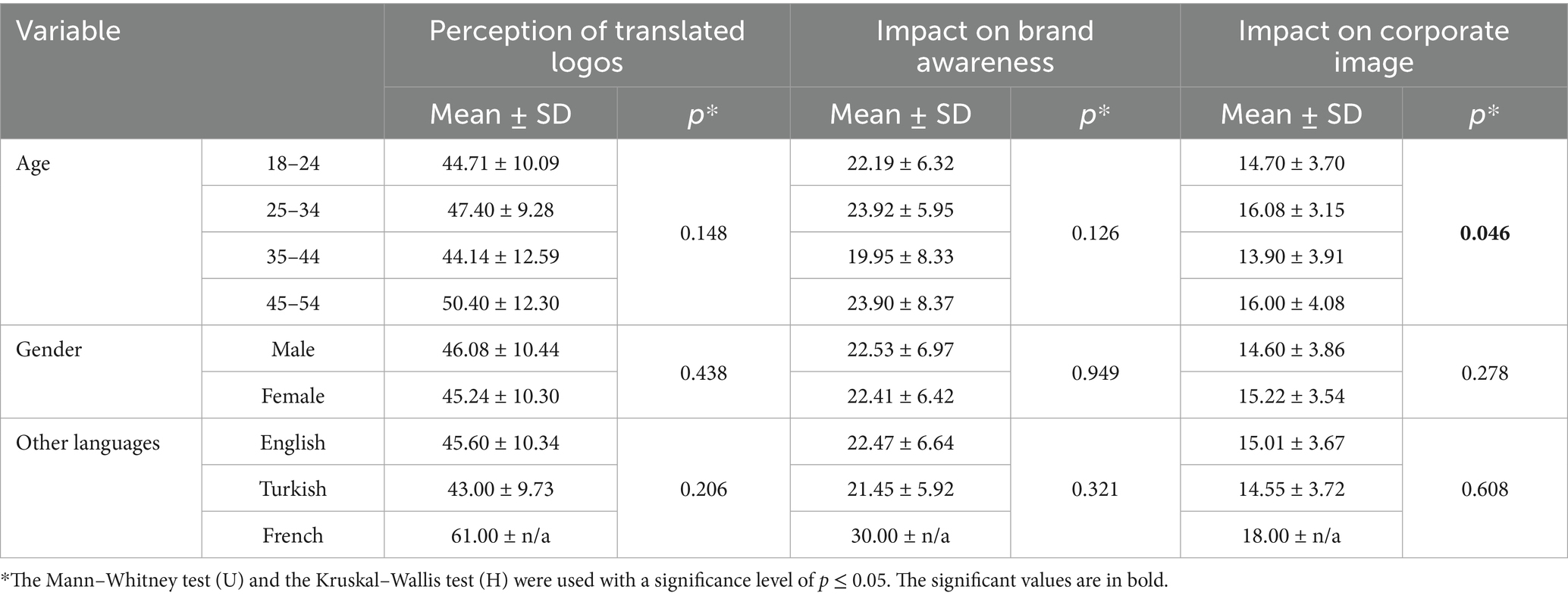

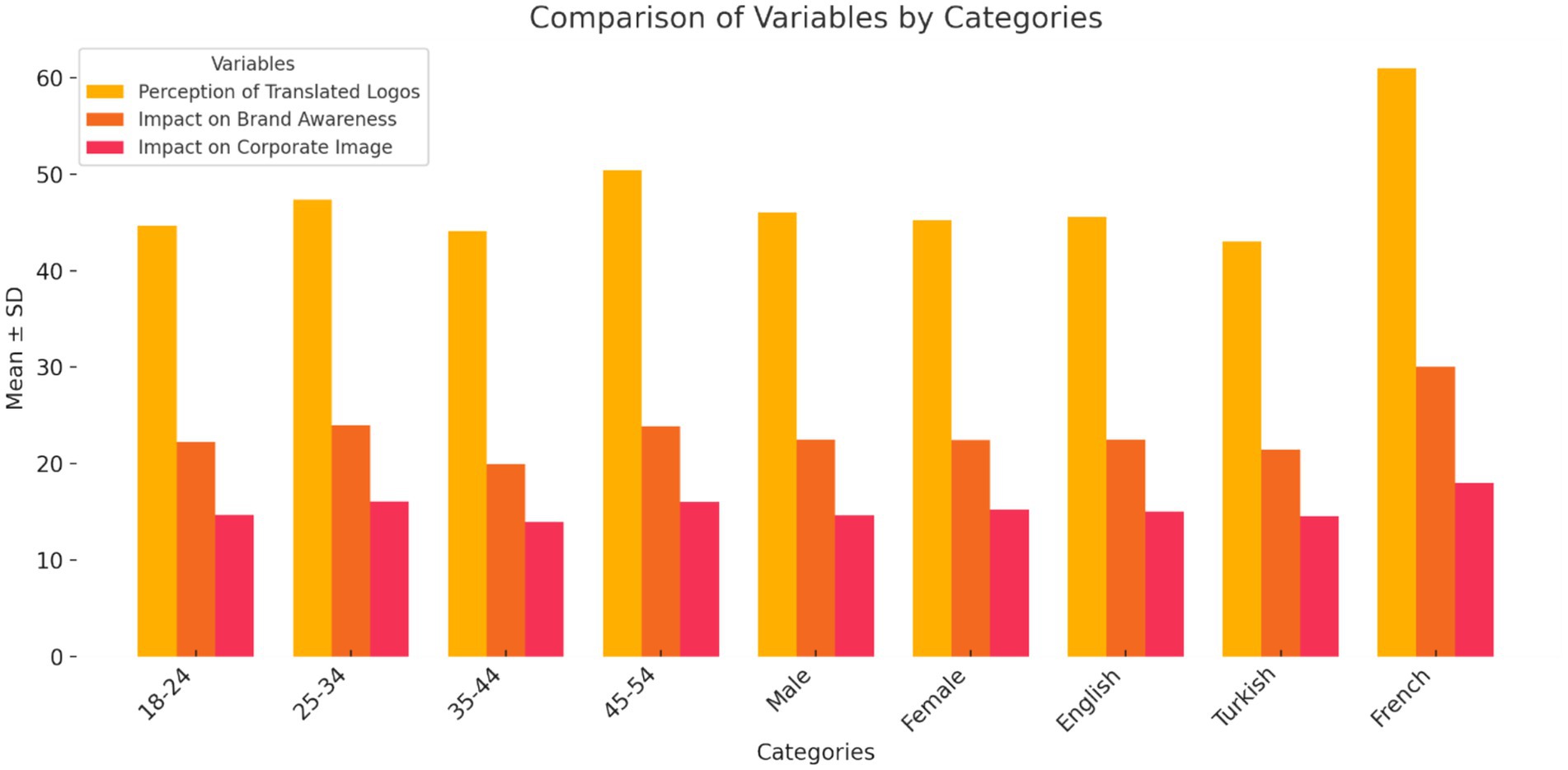

In terms of age, individuals aged 18–24 have moderate scores for perception of translated logos (44.71 ± 10.09), brand awareness impact (22.19 ± 6.32), and corporate image impact (14.70 ± 3.70). The 25–34 age group shows a slight increase in all three categories, with scores of (47.40 ± 9.28), (23.92 ± 5.95), and (16.08 ± 3.15) respectively. Participants aged 35–44 exhibit a slight decrease in perception (44.14 ± 12.59) and brand awareness (19.95 ± 8.33), while their corporate image impact (13.90 ± 3.91) is comparable to younger age groups. The 45–54 age group has the highest scores across all categories, with perception (50.40 ± 12.30), brand awareness (23.90 ± 8.37), and corporate image impact (16.00 ± 4.08). Notably, the impact on corporate image shows statistical significance among age groups (p = 0.046).

For gender, males and females have similar scores for perception and brand awareness impact. Males have slightly higher scores in perception (46.08 ± 10.44) and brand awareness (22.53 ± 6.97), but females score higher in corporate image impact (15.22 ± 3.54) compared to males (14.60 ± 3.86). There are no statistically significant differences across gender for any of the variables.

Regarding other languages, English speakers show average scores across perception (45.60 ± 10.34), brand awareness (22.47 ± 6.64), and corporate image impact (15.01 ± 3.67). Turkish speakers exhibit slightly lower scores in all categories, with perception (43.00 ± 9.73), brand awareness (21.45 ± 5.92), and corporate image impact (14.55 ± 3.72). French speakers, although with limited data, show the highest scores across all three categories: perception (61.00 ± n/a), brand awareness (30.00 ± n/a), and corporate image impact (18.00 ± n/a). The p-values indicate no significant differences for other languages across any of the variables (Table 4 and Figure 4).

Table 4. Perception of translated logos, brand awareness, and corporate image scores based on the characteristics of participants.

Figure 4. An illustration of perception of translated logos, brand awareness, and corporate image scores by participant characteristics.

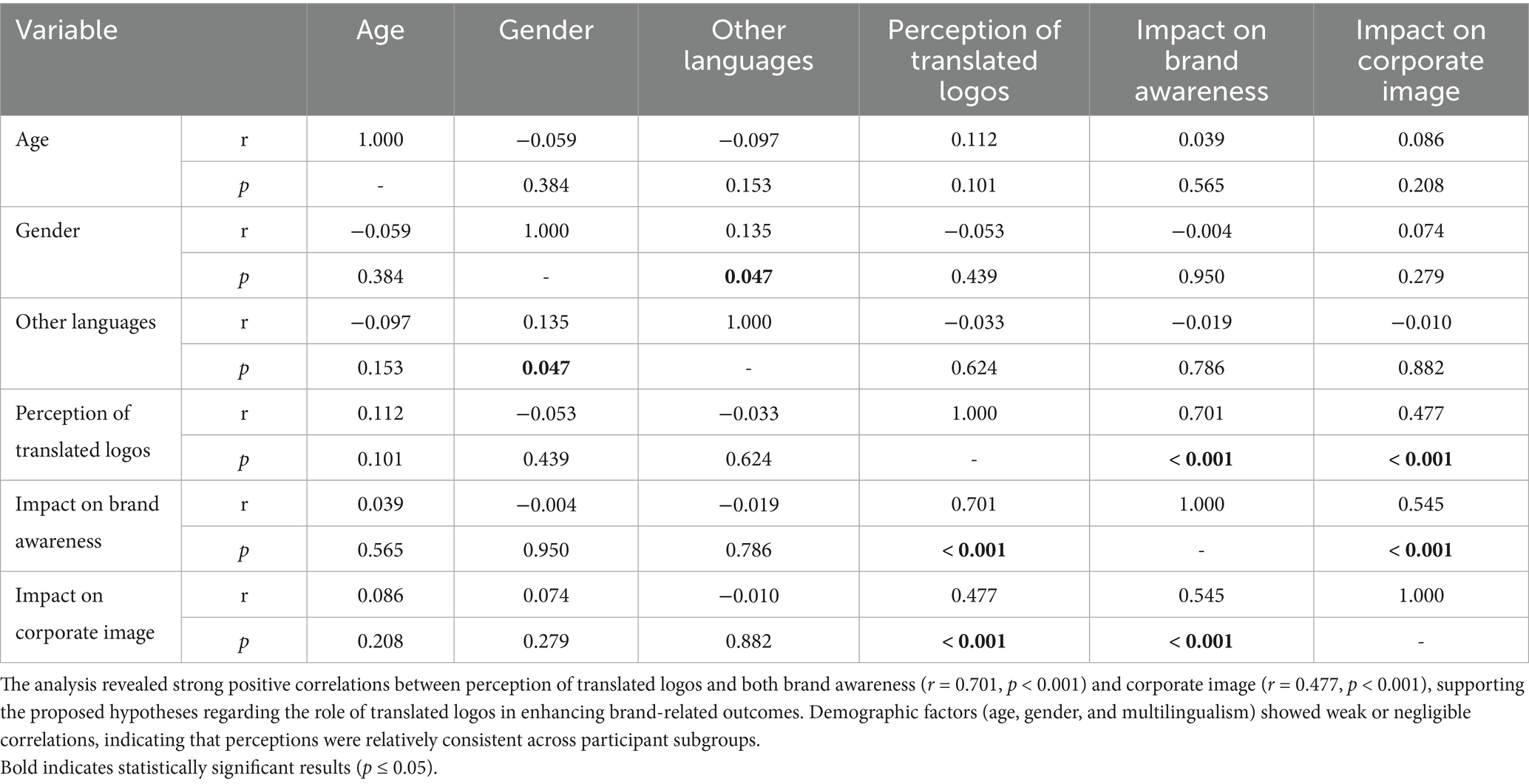

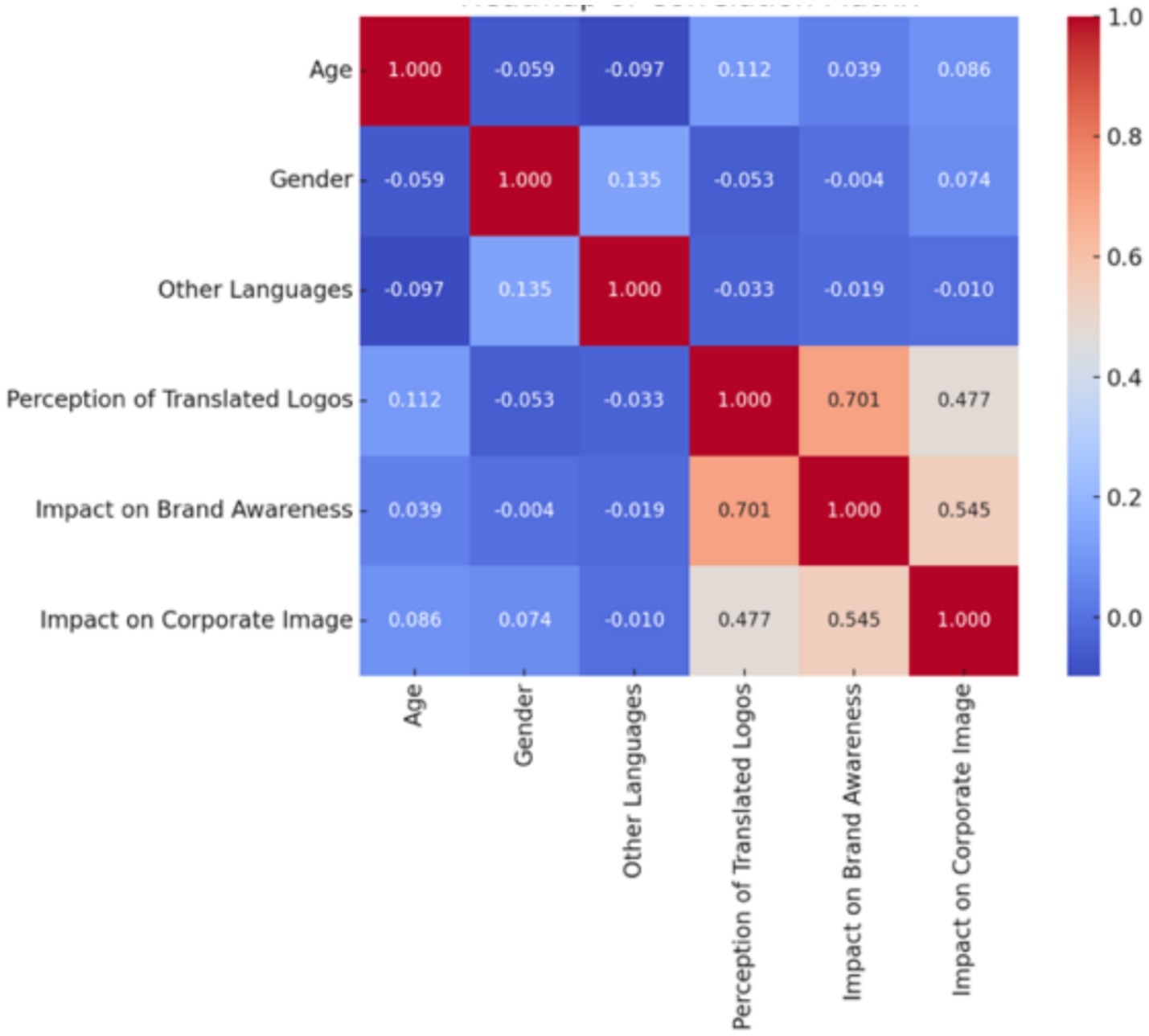

5.4 Correlation analysis

Table 5 and Figure 5 provide a detailed summary of the correlation analysis The Spearman correlation analysis reveals various relationships between demographic factors and perceptions regarding translated logos. Age shows a positive, albeit weak, correlation with Perception of Translated Logos (r = 0.112, p = 0.101), and an even weaker positive correlation with Impact on Corporate Image (r = 0.086, p = 0.208). Interestingly, gender exhibits a small positive correlation with Other Languages (r = 0.135, p = 0.047) and a weaker positive correlation with Impact on Corporate Image (r = 0.074, p = 0.279).

The knowledge of Other Languages shows negligible correlations with Perception of Translated Logos (r = −0.033, p = 0.624), Impact on Brand Awareness (r = −0.019, p = 0.786), and Impact on Corporate Image (r = −0.010, p = 0.882), indicating that multilingualism does not significantly affect these perceptions.

Perception of Translated Logos is strongly correlated with both Impact on Brand Awareness (r = 0.701, p < 0.001) and Impact on Corporate Image (r = 0.477, p < 0.001). Similarly, there is a strong correlation between Impact on Brand Awareness and Impact on Corporate Image (r = 0.545, p < 0.001) (Table 4 and Figure 4).

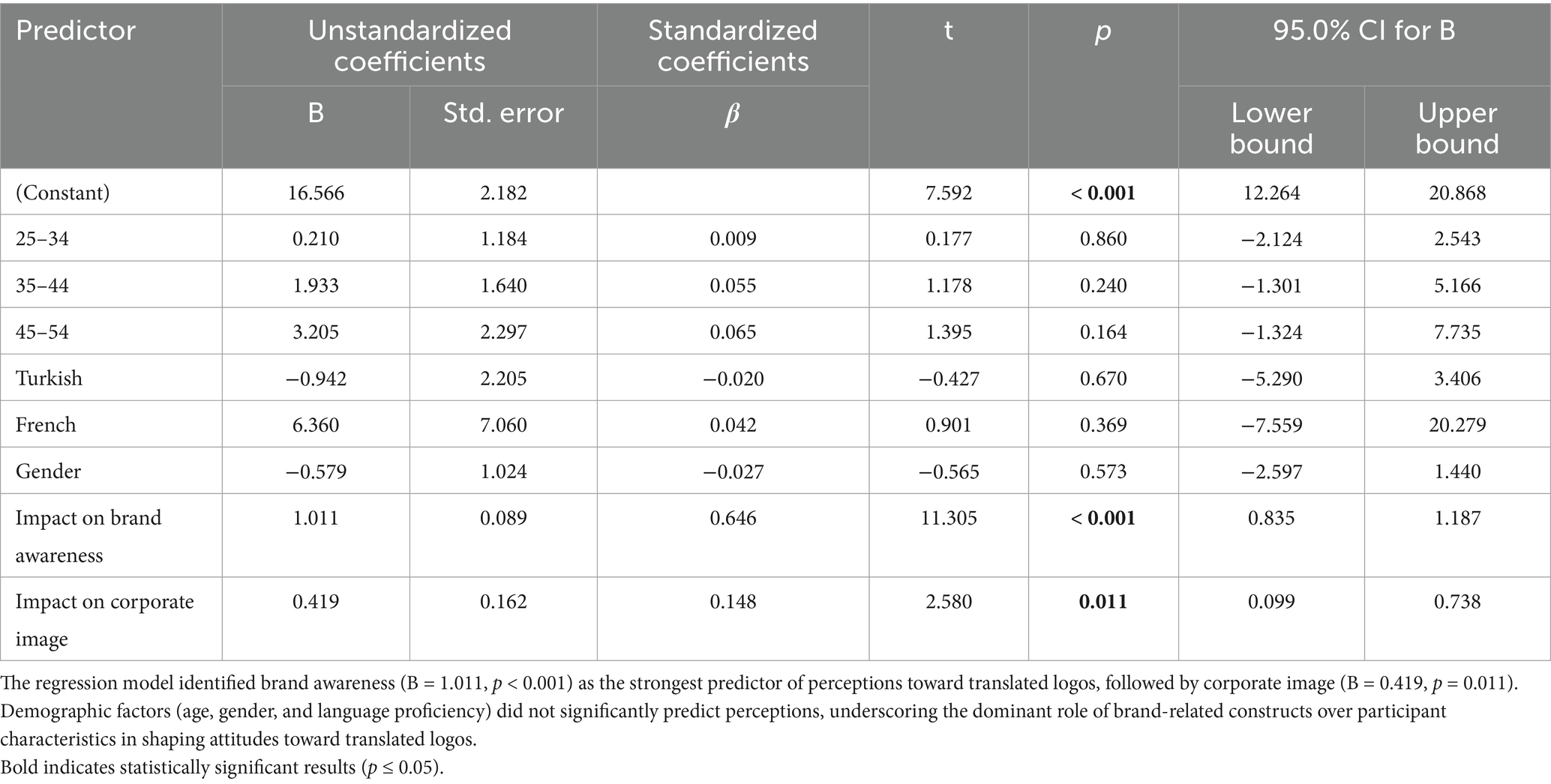

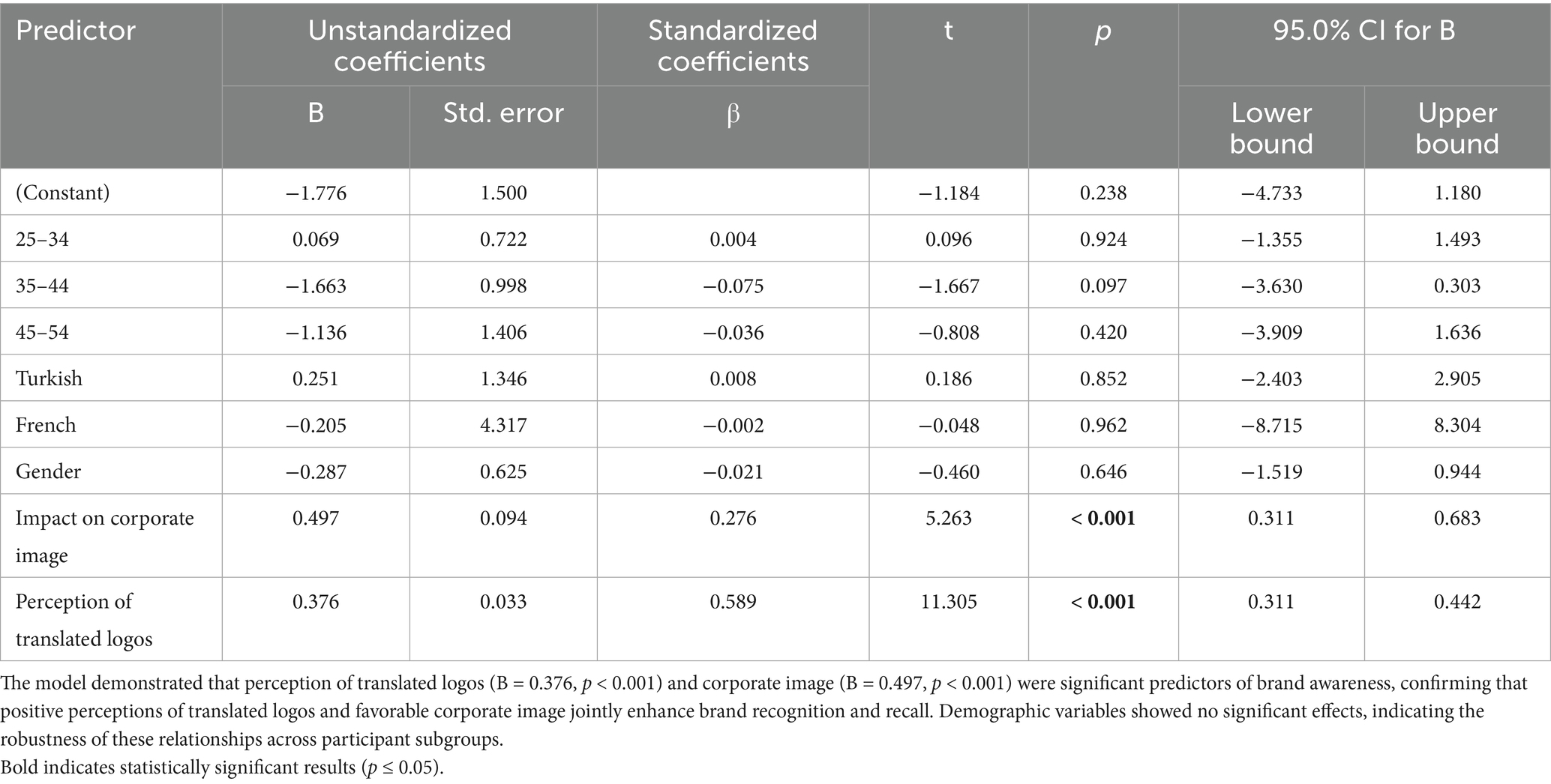

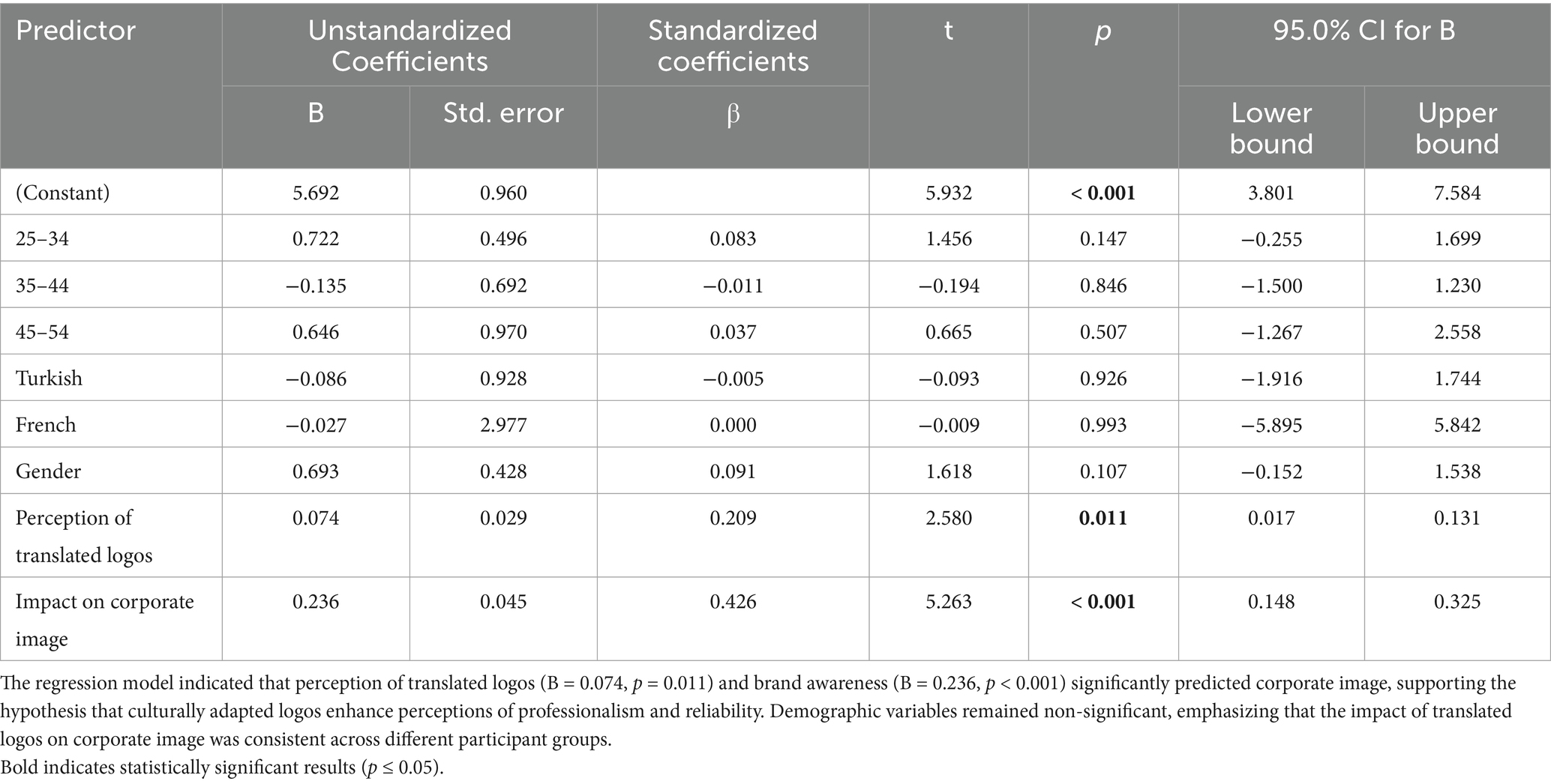

5.5 Regression analysis

Table 6 provides a summary of the regression analyses provide insights into how different variables influence perceptions of translated logos, brand awareness, and corporate image. In the regression model with Perception of Translated Logos as the dependent variable, significant predictors were Impact on Brand Awareness (B = 1.011, β = 0.646, p < 0.001) and Impact on Corporate Image (B = 0.419, β = 0.148, p = 0.011), while other variables like age groups (25–34, 35–44, 45–54), knowledge of other languages (Turkish, French), and gender did not show significant effects.

For the regression model with Impact on Brand Awareness as the dependent variable, significant predictors included Impact on Corporate Image (B = 0.497, β = 0.276, p < 0.001) and Perception of Translated Logos (B = 0.376, β = 0.589, p < 0.001), whereas age groups, knowledge of other languages, and gender showed no significant effect.

In the regression model with Impact on Corporate Image as the dependent variable, significant predictors were Perception of Translated Logos (B = 0.074, β = 0.209, p = 0.011) and Impact on Corporate Image itself (B = 0.236, β = 0.426, p < 0.001), while age groups, knowledge of other languages, and gender did not significantly affect the corporate image (Tables 6–8).

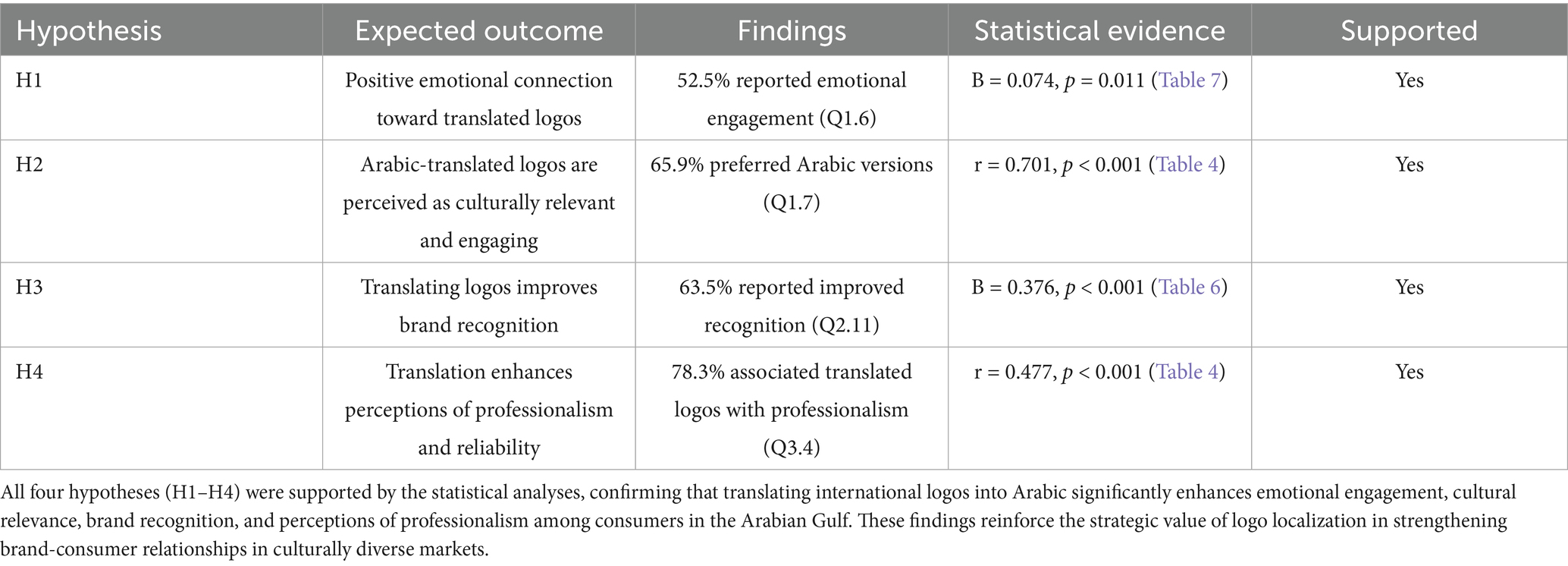

5.6 Hypotheses testing

Table 9 provide a detailed summary The analyses provided clear support for all proposed hypotheses. H1, which predicted a positive emotional connection toward translated logos, was supported, with 52.5% of participants reporting emotional engagement (Q1.6; Table 2) and regression analysis showing a significant association between perceptions of translated logos and corporate image (B = 0.074, p = 0.011; Table 7). H2, which proposed that translated logos are perceived as more culturally relevant and engaging, was validated by 65.9% of respondents preferring Arabic versions of global brand logos (Q1.7; Table 2) and by strong correlations between perceptions of translated logos and brand awareness (r = 0.701, p < 0.001; Table 4). H3, anticipating that translating logos improves brand recognition, was supported by the 63.5% recognition rate (Q2.11; Table 2; Figure 2) and regression results showing a strong predictive relationship between perceptions of translated logos and brand awareness (B = 0.376, p < 0.001; Table 6). Finally, H4, predicting that logo translation enhances perceptions of professionalism and reliability, was confirmed by 78.3% associating visually harmonious translated logos with professionalism (Q3.4; Table 2) and a significant positive correlation between perceptions of translated logos and corporate image (r = 0.477, p < 0.001; Table 4).

6 Discussion

This study examined how translating international logos into Arabic influences brand awareness and corporate image within the Arabian Gulf, with particular attention to the role of cultural adaptation, semiotics, and brand culture. The findings provide robust empirical support for the theoretical constructs introduced in the literature review, demonstrating that the translation of logos is not merely a linguistic process but a cultural and semiotic act that enhances recognition, emotional engagement, and perceptions of professionalism.

This study proposed four hypotheses (H1–H4) to examine how translated international logos influence brand awareness and corporate image in the Arabian Gulf. The findings provide strong empirical support for all hypotheses. H1, predicting a positive emotional connection toward translated logos, was validated by participants’ reported emotional engagement (52.5% often or always; Q1.6; Table 2). H2, which proposed that Arabic-translated logos are perceived as more culturally relevant and engaging, was confirmed, with 65.9% of respondents expressing a preference for localized versions (Q1.7; Table 2). H3, anticipating improved brand recognition through logo translation, was supported by the 63.5% increase in brand recognition (Q2.11; Table 2; Figure 2). H4, positing that translation enhances perceptions of professionalism and reliability, was also supported by the significant positive associations between visually harmonious logos and corporate professionalism (Q3.4; Table 2). These results collectively affirm that logo translation not only enhances brand awareness but also strengthens perceptions of professionalism and cultural sensitivity, reinforcing the strategic value of cultural adaptation in branding.

The results indicate that translating global brand logos into Arabic significantly enhances brand recognition and recall, with 63.5% of respondents reporting improved brand recognition when logos were translated (Table 2; Figure 2). This supports the assertion of Glukhova (2021) that cultural adaptation serves as a bridge between global branding strategies and local cultural frameworks, making brand identities more salient and familiar to consumers in specific cultural contexts. These findings also align with cognitive theories of recognition processing, which suggest that consumers are more likely to recognize and recall brand identities when visual and linguistic cues are culturally familiar (Kayrouz and Hansen, 2020). The cultural adaptation of logos, therefore, functions not only as a branding strategy but also as a cognitive mechanism that facilitates information processing and increases brand awareness.

Emotional engagement emerged as a key outcome of logo translation. Nearly half of the participants (48.8%) expressed happiness when global online store brand logos were translated into Arabic, and 21.2% reported a personal emotional connection to these logos (Table 2; Figure 2). These results validate Schroeder’s (2009) conceptualization of brand culture as a vehicle for emotional resonance and Visconti’s (2017) semiotic framework, which positions logos as cultural texts that embed meaning within local contexts. The finding that 26.7% of respondents trusted global brands more when their logos were translated (Table 2) underscores the semiotic principle that logos act as signifiers of corporate intent, signaling cultural respect and inclusivity (Bobrie, 2018). These emotional and trust-based responses suggest that brand translation fosters stronger relational bonds between consumers and global brands, ultimately enhancing consumer loyalty (Guèvremont and Grohmann, 2016).

The study also uncovered challenges associated with logo translation, particularly concerning visual harmony and meaning retention. Approximately 21.7% of participants expressed concerns about the loss of visual harmony, and 23% noted a loss of original meaning when logos were translated (Table 2). These findings emphasize the delicate balance required in cultural adaptation, supporting Harun et al.’s (2011) Culture of Brand Origin (COBO) framework, which underscores the importance of maintaining the symbolic integrity of a brand while adapting to local contexts. From a semiotic perspective, these tensions reflect the dual responsibility of translated logos to convey global brand identity while simultaneously embedding culturally resonant meanings (Visconti, 2017).

The impact of translated logos on corporate image was profound, with 68.7% of respondents affirming that a well-designed, culturally attuned translated logo reflects positively on a company’s commitment to the Arabian Gulf market, and 78.3% associating visually harmonious translated logos with corporate professionalism (Table 2). These findings reinforce Harun et al.’s (2015) position that linguistic and cultural adaptation enhances perceived authenticity and trustworthiness. They also align with Actor-Network Theory (Latour, 2005), which views brands as assemblages of visual, cultural, and social actors; here, translated logos serve as mediating artifacts that connect global corporations to local cultural networks. The strong correlations between perceptions of translated logos and corporate image (r = 0.477, Table 4; Figure 4) further support this view, highlighting that corporate image emerges from the dynamic interplay between cultural adaptation and consumer interpretation.

Regression analysis strengthens these interpretations by demonstrating that perceptions of translated logos significantly predict brand awareness (B = 0.376, p < 0.001; Table 6) and corporate image (B = 0.074, p = 0.011; Table 7). These quantitative relationships substantiate the proposition that localized visual identities do more than improve recognition—they actively shape how consumers evaluate brand professionalism and cultural sensitivity. By integrating these findings with semiotic and cultural theories, it becomes clear that translated logos act as strategic tools for embedding global brands into the socio-cultural fabric of the Arabian Gulf.

6.1 Comparative summary

These findings resonate with and expand upon previous cross-cultural branding research. For instance, Jiang and Wei (2012) found that multinational corporations that localized advertising messages achieved greater cultural resonance in Chinese markets, a pattern mirrored here in the Arabian Gulf context. Similarly, Safeer and Liu (2023) emphasized that translation enhances brand trust and consumer loyalty, aligning with our results showing increased trust (26.7%) in brands with translated logos. Unlike Peterson et al. (2015), who noted that logo redesigns sometimes alienate core audiences, this study shows that careful linguistic and cultural adaptation can strengthen brand identity without compromising global cohesion. Thus, this research contributes to the growing evidence that localized visual identities, when executed with cultural sensitivity, not only improve recognition but also enhance emotional and professional associations with global brands.

Collectively, these results have important implications for global brand management. Translating logos into Arabic can enhance brand salience, build emotional and cognitive connections, and improve perceptions of corporate professionalism. However, the process must be carefully managed to avoid visual disharmony or semantic distortion, which may undermine brand integrity. This aligns with Glukhova’s (2021) argument that cultural adaptation should be iterative and collaborative, involving designers, linguists, and cultural experts to balance global consistency with local resonance.

In sum, this study confirms that logo translation in the Arabian Gulf is a semiotic and cultural negotiation that shapes consumer perceptions of brand awareness and corporate image. By grounding these empirical findings in the theoretical constructs of brand culture, semiotics, and Actor-Network Theory, the discussion reveals that successful logo translation extends beyond mere linguistic conversion—it is a process of cultural embedding that strengthens consumer trust, emotional engagement, and brand professionalism in a competitive regional market.

6.2 Limitations and future research

Despite the valuable insights provided by this study, there are limitations that should be addressed in future research. The cross-sectional study design and reliance on self-reported data may introduce bias and limit the generalizability of the results. Future research could use longitudinal designs and larger, more diverse samples to validate and extend the current findings. Additionally, exploring the impact of specific design elements and cultural nuances on logo translation can provide more detailed guidance for brands aiming to adapt their visual identity to different cultural contexts.

6.3 Practical implications

These findings carry substantial implications. For global marketers and designers, translating logos into Arabic transcends the notion of mere accessibility—it represents a deliberate strategic branding choice that communicates cultural respect, inclusivity, and a genuine corporate commitment to engaging with local audiences. Such localization efforts can significantly enhance brand salience, streamline cognitive processing through the use of familiar linguistic cues, and strengthen perceptions of professionalism and credibility. This is especially critical in the Arabian Gulf, where cultural and linguistic identity plays a pivotal role in shaping consumer-brand interactions. Consequently, the study underscores the need for collaborative localization approaches, integrating the expertise of linguists, designers, and cultural consultants to achieve a balance between visual harmony and cultural authenticity.

7 Conclusion

This study investigated the influence of translating international logos into Arabic on brand awareness and corporate image among consumers in the Arabian Gulf, employing a quantitative, cross-sectional design grounded in brand culture theory, semiotics, localization frameworks, and cognitive processing models. The results provide compelling empirical support for all four hypotheses, confirming that logo translation significantly enhances emotional connection, cultural relevance, brand recognition, and perceptions of professionalism and reliability. Correlation and regression analyses further revealed that perceptions of translated logos strongly predict both brand awareness and corporate image, underscoring the strategic role of cultural and linguistic adaptation in shaping consumer perceptions of global brands.

These findings advance the scholarly understanding of cross-cultural branding by reframing logo translation as more than a linguistic adjustment. Instead, it emerges as a semiotic and cultural negotiation that allows global brands to embed themselves within local cultural narratives while maintaining global identity coherence. This contributes to literature on brand culture (Schroeder, 2009), semiotics (Visconti, 2017), and the Culture of Brand Origin (COBO) framework (Harun et al., 2011), demonstrating that visual identity localization is a critical driver of consumer trust, loyalty, and engagement in culturally complex markets.