- Department of Communication and Arts, Roskilde University, Roskilde, Denmark

Digital disruptions have put an emphasis on innovation as a means for survival for news and journalism in uncertain times. As a response, Denmark introduced a targeted subsidy instrument for news-media innovation in 2014 to support both the establishment of new news media and the development of legacy media. This study analyzes the first decade of this subsidy instrument (2014–2023), where a total of 23,573,219 EUR was allocated. Guided by studies based on innovation-policy impact assessment, we map and evaluate the news-media innovation subsides with a focus on outputs, outcomes, and impact. The analysis shows that 52 % of the subsidies has been allocated to legacy media, the rest to new news media. Furthermore, we find that new news media predominantly do innovation aimed at content and market development, whereas legacy media pursue product development. One outcome is that 44 new news media have been established with the support of the subsidy instrument, 31 of which still exist. Finally, in terms of impact, the analysis shows that of the 31 new news media, only few are both widely recognized and used by the Danish population.

Introduction

There is a long-standing discussion about the role of state subsidies in connection with innovation. On the one hand, critics argue that such subsidies slow down or even hinder innovation because they remove the incentive for pursuing new, better, and more efficient ways of doing things. On the other hand, proponents argue that exactly the existence of such subsidies create an environment with enough security and stability to make organizations take risks and try new ways. These positions mirror a rather fundamental disagreement about the role of the state in the market, invoking, respectively, notions of an “invisible hand of the market” (Smith, 1961) and of expansionary fiscal policy (Keynes, 2006).

Situated at this inflection point of publicly subsidized innovation is the news industry. As the news industry finds itself in a funding crisis (Cagé, 2016; Park et al., 2024; Picard, 2010), innovation constitutes a Leitmotif in the current search for pathways to a financially sustainable future. More than 20 years into the digital age, the news industry still struggles with digital transformations and their consequences: the business models of the good old days have not found a viable substitute in the digital context (Grueskin et al., 2011; Nel, 2010; Nielsen, 2012), and changes in news consumption as well as ever-increasing competition from digital intermediaries only add insult to injury (Newman et al., 2024; Nielsen and Ganter, 2017). In response to this crisis, news media (old and new) as well as policy makers and many researchers have heralded innovation as the remedy (Küng, 2015; Pavlik, 2013; Posetti, 2018; Solvoll and Olsen, 2024).

This empirical research has often focused on individual actors or specific organizations contexts, largely neglecting a macro-level perspective on the structural frameworks that condition news-media innovation (Noster et al., 2025). However, as innovation is shaped by the environment it exists within, such a structural perspective is important. But, the empirical research is inconclusive. On the one hand, comparative research (building on the media-systems theory by Hallin and Mancini, 2004) finds that the digital transformation and innovation of news media occur at a slower pace in countries within Democratic Corporatist media systems than within those in Liberal and Polarized Pluralist media systems (Meier et al., 2024). The explanation given is that a government focus on media subsidies to legacy news media crowd out innovative competition (Kaltenbrunner, 2024). On the other hand, public subsidies to news media are also found to have beneficial effects such as securing the public access to quality news, even in times of transition and also in creating an economic foundation for news media to experiment with innovation (Kammer, 2017; Murschetz, 2022). While various foundations and privately owned initiatives support news-media innovation and the development of journalism (Buschow et al., 2024; de-Lima-Santos et al., 2023; Hermida and Young, 2024; Lewis, 2011, 2012; Mesquita and de-Lima-Santos, 2023), such public subsidies for news-media innovation are, however, a rare breed internationally (Noster, 2024; Noster et al., 2025).

Against this background, this article explores the first decade of media-innovation subsidies in Denmark, mapping and discussing what the allocation of public funds to the establishment and digital transformation of the news media has resulted in. Denmark, epitomizing the Democratic Corporatist media model (cf. Hallin and Mancini, 2004; Humprecht et al., 2022), constitutes a pertinent case to study, as media subsidies to news media innovation has been an integral part of the system since 2014. The question is, however, what has come out of such a policy intervention. With an empirical focus on the first decade where this subsidy instrument was in effect, that is the question this article answers.

(News media) innovation

Drawing upon Schumpeter's (1950) argument that capitalism develops through cycles of “creative destruction”, Storsul and Krumsvik summarize the dominant terminological understanding of innovation by stating that it “implies introducing something new into the socioeconomic system” (2013, p. 14, emphasis in original). Kline and Rosenberg (1986), likewise, argue that innovation is the meeting between new technology and the market. This way, even though innovation is an umbrella term (Schützeneder, 2022), the scholarly literature emphasizes two characteristics that are typically associated with innovation: first, that is has to do with newness and, second, that that which is new enters the market and/or social life (see also Fagerberg, 2006). The second characteristic is what separates innovations from inventions. Newness, on the other hand, can consist of novel combinations or improvements of existing ideas and technology rather than necessarily the development of something radically new. This way, innovations can (and will often) be incremental in the sense that they improve what already exists (Ettlie et al., 1984; Schumpeter, 1950).

Conceptually, the notion of “something new” of innovations is vague and ambiguous, and it can take many shapes and forms in practice. For example, Storsul and Krumsvik (2013) distinguish between “the four p's” of innovation, namely product, process, position, and paradigm (see also Noster, 2024). Along the same lines, García-Avilés et al. (2018) suggest that innovation in the media will usually fall within the areas of product or service, production and distribution process, company organization, and marketing. This way, there are few boundaries as to what exactly constitutes innovation.

Media innovation, in turn, is innovation that relates to the media specifically. The media in general and the news media in particular are “not just any other business” (McQuail, 2000, p. 190), they are institutions of democracy as well. For this reason, Trappel (2015) normatively asserts that there must be more to media innovation than just introducing something new to the market. Rather, he suggests, what defines media innovation (and what he really refers to is news-media innovation) is the underlying emphasis on democratic development through the societal, political, and cultural roles of the media; media innovation, in his view, must contribute to the realization of the social and democratic objectives of the media, not just to the introduction of commodities to the market. Such a perspective, underlining the particularities of the news media sector and its importance for society, also relates to Storsul and Krumsvik's idea of social innovation; that is, “innovation that meets social needs and improves people's lives” (2013, p. 17, emphasis added; see also Bruns, 2014). The same perspective runs through Danish media policy; one anecdotal example is that the expert report that paved the way for the 2014 overhaul of the press-subsidy framework (which the news-media innovation subsidy is part of) carried the titled “Democracy support” (The Agency for Libraries and Media, 2011).

That said, innovation in the news media that aims at developing, for example, business models or work processes rather than contributing to democracy is obviously also media innovation (it is, after all, innovation that relates to the media). This way, an explicit pursuit of democratic objectives is not necessarily a definitional criterion for something to quality as media innovation, even if it is often the case that there is a direct or indirect democratic benefit from such innovation. Rather, what is important in terms of definitions for innovation to qualify as news-media innovation is that it happens within and supports organizations that contribute to democratic society through conducting journalism.

Media innovation takes place in various organizational and institutional contexts. Legacy media organizations, on the one hand, continuously work on adapting to the digital age, developing formats, tools, and practices that updates and makes “old” organizations relevant to “new”, digital contexts of news making and consumption (Cornia et al., 2017; Küng, 2015, 2017; Pavlik, 2013; Sehl et al., 2017; Usher, 2014). While a number of incumbent actors in the news industry have proved successful in becoming digital innovators (Küng, 2015; Usher, 2014), innovation processes in legacy media organizations are, however, often counteracted by the path-dependence and perseverance of established work patterns (Belair-Gagnon and Steinke, 2020; Boczkowski, 2005). Steensen (2009), for example, shows how established hierarchies and bureaucracies of the newsroom would often stall individual journalists that want to experiment to improve their work. Likewise, organizational bureaucracies have for many years created a barrier for digital innovation because there would be no natural “home” for those activities in the news organizations (Belair-Gagnon and Steinke, 2020; Boyles, 2016).

On the other hand, as asserted by Achtenhagen (2008), news start-ups often assume a prominent position in the discussion of media innovation. They are new organizations without the path-dependence of institutionalized newsroom routines, but (at least in a US context) often with a Silicon Valley-inspired move-fast-and-break-things approach to filling gaps in the market (Usher, 2017; Usher and Kammer, 2019).1 For this reason, this type of news organizations at the periphery of the industry are where new ideas and solutions are expected to see the light of day and be tested against reality. A leaked innovation report from The New York Times (2014), for example, highlighted newcomers to the news industry such as Vox, Buzzfeed, and the Huffington Post rather than incumbent news media as primary competitors in terms of development and innovation (see also Küng, 2015).

A conflictual relationship between business orientation and the ideological work of journalism has existed throughout most of modern journalism history in the so-called separation between “church and state”. As such, one could expect the turn toward news startups and entrepreneurial journalism to challenge and apply pressure upon the professional tenets of journalism—and studies of news startups also identify this tension as a central one in the formation of new editorial enterprises (see, e.g., Naldi and Picard, 2012; Powers and Zambrano, 2016). That this is the case should come as no surprise since financial sustainability is found to be a central problem for news startups (Bruno and Nielsen, 2012; Sirkkunen and Cook, 2012). Even so, international studies of news startups and the ways they articulate and legitimize their ambitions and values show how they generally confirm the fundamental values of journalism (Carlson and Usher, 2016; Price, 2017; Sen and Nielsen, 2016). As Usher observes, news startups may represent alternatives to the established order, but they “leave the fundamental doxa of the field intact” (Usher, 2017, p. 1116).

Research context: innovation in Democratic Corporatist media systems

Innovation takes place in many different organizational settings and also plays out differently from country to country (Meier et al., 2024). Analyzing innovation subsidies in different countries, Noster (2024) finds seven countries with national subsidies earmarked for news-media innovation as part of the media policy, namely Denmark, France, Luxemburg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Canada. Except for France and Canada, all these countries exist within Democratic Corporatist media systems. While the definition of the Democratic Corporatist system originates with Hallin and Mancini (2004), it has been updated several times, most recently by Humprecht et al. (2022). In this last update, however, the only media system that remains largely unchanged by digital disruption is the Democratic Corporatist system. Thus, what characterizes this media-systemic model is still the co-existence of public and private media, the high level of journalistic professionalism, and the extensive state-intervention in the media sector. This intervention exists in the form of both regulation and direct as well as indirect subsidies, such as the news-media innovation subsidies that are the focus of this article (see also Lund and Lindskow, 2011).

A reason for the strong role of the state can be found in the fact that Denmark is what is also known as one of the Nordic media-welfare states (Syvertsen et al., 2014; see also Kammer, 2016). Here, the existence of media subsidies is not only understood as support for a specific sector of society, but rather as supporting the democratic function of the news media by supporting conditions for democratic discourse to flourish through trustworthy media. As Søndergaard and Helles (2014) summarize it, “the central values of Danish media policy have stayed remarkably constant: the political focus remains on securing the freedom of expression and pluralism of voices by actively supporting both private and public media” (p. 41).

Though welfare states come in different shapes (Esping-Andersen, 1990; Kangas and Kvist, 2018), one can distinguish between a social democratic Nordic model and different continental models. Of the seven countries with media subsidies at a national level investigated by Noster (2024), Denmark, Norway and Sweden are all part of the Nordic social democratic welfare state model, while Luxemburg, Netherlands and France typically would be placed in a so-called continental model of welfare states. Canada is a “liberal welfare” state, but as such much different from the US (Myles, 1998). In other words, the Nordic media welfare states stand out when it comes to media subsidies, and especially subsidies earmarked for media innovation. Nordic media welfare states also stand out as media markets where legacy news media dominate and where trust in news and willingness to pay for news is higher than average (Newman et al., 2024). In this light Denmark is a case study of the Democratic Corporatist model and can be understood as a “most likely” case (Flyvbjerg, 2006) in regard to the study of innovation subsidies for both new and legacy news media.

The case of the Danish news-media innovation subsidies

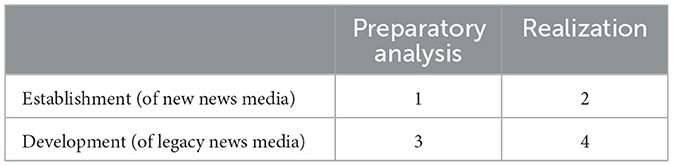

This study focuses specifically on the subsidies for news-media innovation. This particular subsidy instrument has been in effect since 20142 and allocates public funds for both the establishment of new news media and the development (digital transformation) of legacy news media; within both categories, subsidies are allocated for preparatory analysis (to research whether an innovation is feasible) and for the realization of an innovation. This way, there are four different types of innovation subsidies in the framework (see Table 1).

Annually, 2,680,591 EUR3 is allocated in subsidies for news-media innovation (after the period researched in this article, the amount of funding has increased to 4,181,723). This amount of funding constitutes 0.4 % of the total public funding for Danish media, which amounts to approximately 679,093,737 EUR (in 2023). The subsidies are administered by the Agency for Palaces and Culture (an administrative unit under the Ministry of Culture) and allocated on the basis of assessments made by the Media Council, which consists of industry experts and works at arm's-length independence.

A newly established news medium can receive innovation subsidies for a maximum of three years. After that, it should be financially sustainable to a degree that it can transfer to the ordinary press subsidies. The formal criteria for eligibility for, respectively, the innovation subsidies and the ordinary subsidies are almost identical.

Research questions

On the basis of the theoretical framework of (media) innovation and the (media-systemic) characteristics of the empirical case, the study asks what has come out of the innovation subsidies and to what extent this specific subsidy instrument has supported what it was supposed to support. To provide an answer, we draw upon the literature on innovation-policy impact assessment. In the evaluation of innovation policy, focus is commonly on outputs, outcomes, and/or impacts (Lindmark et al., 2013). Outputs, first, are the concrete results to come out of the implementation of an innovation policy; that could be the specific products that the policy supports or new actors in the market. Outcomes, second, “are the changes that arise from the implementation” (Lindmark et al., 2013, p. 133). Impacts, third, are the broader (long-term) consequences which come into existence after the implementation and which can, for that reason, only be assessed diachronically after a period of time has passed.

Aligning with this assessment framework, we explore analytically four research questions which also structure the analysis. The first research question is somewhat descriptive, creating baseline knowledge about the allocation of the news-media innovation subsidies:

RQ1: Who has received funding through the news-media innovation subsidy framework?

Moving on to the three dimensions of innovation-policy impact assessment, the next three research questions make inquiries into, respectively, the outputs, outcomes, and impact of the allocation if news-media innovation subsidies:

RQ2: Which types of news-media innovation have been subsidized?

RQ3: Which new news media have emerged with the support of the innovation subsidies?

RQ4: To what extent are new news media, established with the support of the innovation subsidies, recognized by audiences, and how many audiences do they reach?

Methodology and data

To answer these research questions, we conduct a descriptive mapping (RQs1-3) and a national survey (RQ4).

Descriptive mapping

Within media-policy research, mapping is a methodological approach that employs the systematic registration of actors, organizations, policies, origins and outcomes of said policies, and so forth (Raboy and Padovani, 2010). The mapping in this article is conducted through descriptive analysis of the data. Gerring (2012) argues that descriptive analysis “aims to answer what questions (e.g., when, whom, out of what, in what manner) about a phenomenon or a set of phenomena” (p. 722, emphasis in original). This way, description is not concerned with causality (“why”) but, rather, with the thorough laying-out of a phenomenon and what constitutes it; it is about providing an understanding of the phenomenon, not an explanation.

On these grounds, this study descriptively maps “whom” have gotten “what” out of the Danish subsidies for news-media innovation 2014–2023 for “which stated purposes” and to “what effect” (see also Kammer and Blach-Ørsten, 2025).

The data for the descriptive mapping consists, first and foremost, of the overviews of allocations that the Agency for Palaces and Culture publishes annually and keeps publicly available on its website.4 Furthermore, the empirical material consists of the applications for news-media innovation subsidies that were successful (i.e., the applications that resulted in an allocation of funds). These applications consist of filled-out forms, where the applicants describe, among other things, the innovation they want subsidized and specify its “unique character”; this information enables us to register which types of news-media innovation have been subsidized. Access to these documents were secured through right of access to public documents (aktindsigt) from the Danish Ministry of Culture and the Agency for Palaces and Culture.

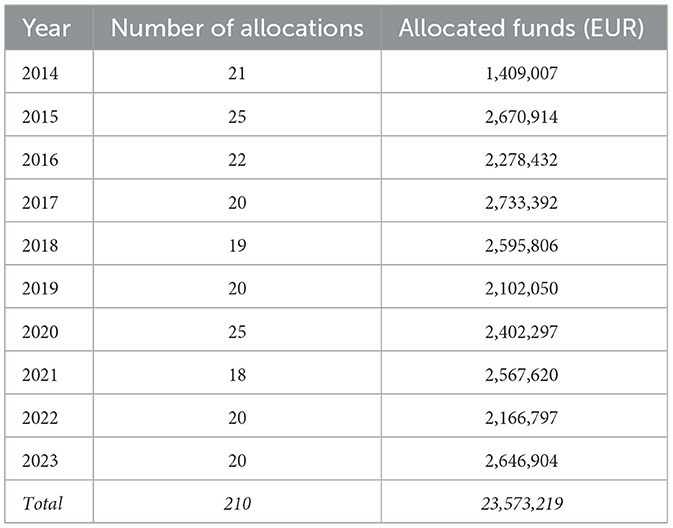

This way, the dataset for the descriptive mapping contains information about the 210 allocations of innovation subsidies that occurred 2014–2023 and accounted to 23,573,219 EUR in total. Table 2 provides an overview of these allocations and shows that both the number of allocations and the allocated amount of funds are fairly stable over the 10-years period (with 2014, the first year of the subsidy scheme, as the exception).

Survey

To explore the impact of the innovation subsidies, we gauge two dimensions: how many audiences recognize the new news media that have been established with support from the subsidy framework, and how many audiences they reach. Both of these measurements are somewhat crude, but they nonetheless capture whether the new news media are known and used among the people in Denmark. Regarding reach, we know from previous studies that public service news media and legacy newspapers online reach the biggest audience (Newman et al., 2024) making it a challenge for new media to enter the market. Regarding brand recognition the same logic applies, as research suggests that new news media struggle in competition with legacy news media, and that time is an important factor in building up an audience (Blach-Ørsten and Mayerhöffer, 2021).

To generate knowledge on brand recognition and media use, we conduct a large survey among the adult Danish population (18–75 years old). In addition to some baseline demographic questions, the survey asked two questions: which of the following news media have you heard or? And which of the following news media have you used within the last week? For the sake of comparison, we also include the most important legacy media.

The survey has 3,020 valid responses, which were collected through Danish polling organization Norstat's online panel from August 14 through August 23, 2024. At this point in time, the population (of people aged 18–75) in Denmark was 4,263,169, so the number of responses and a standard deviation of 0.95 mean that the margin of error is 1.78 %. The survey respondents reflect the overall composition of the Danish population in terms of both gender, age, education, and political leaning.

Findings

The findings are structured around the four research questions.

RQ1: Who has received funding through the news-media innovation subsidy framework?

The descriptive mapping shows that 101 companies have received innovation subsidies through 171 allocations. Furthermore, 39 allocations of innovation subsidies have been directed to individual persons, but even in the cases where these individuals are identifiable, the dataset does not allow for further analysis.

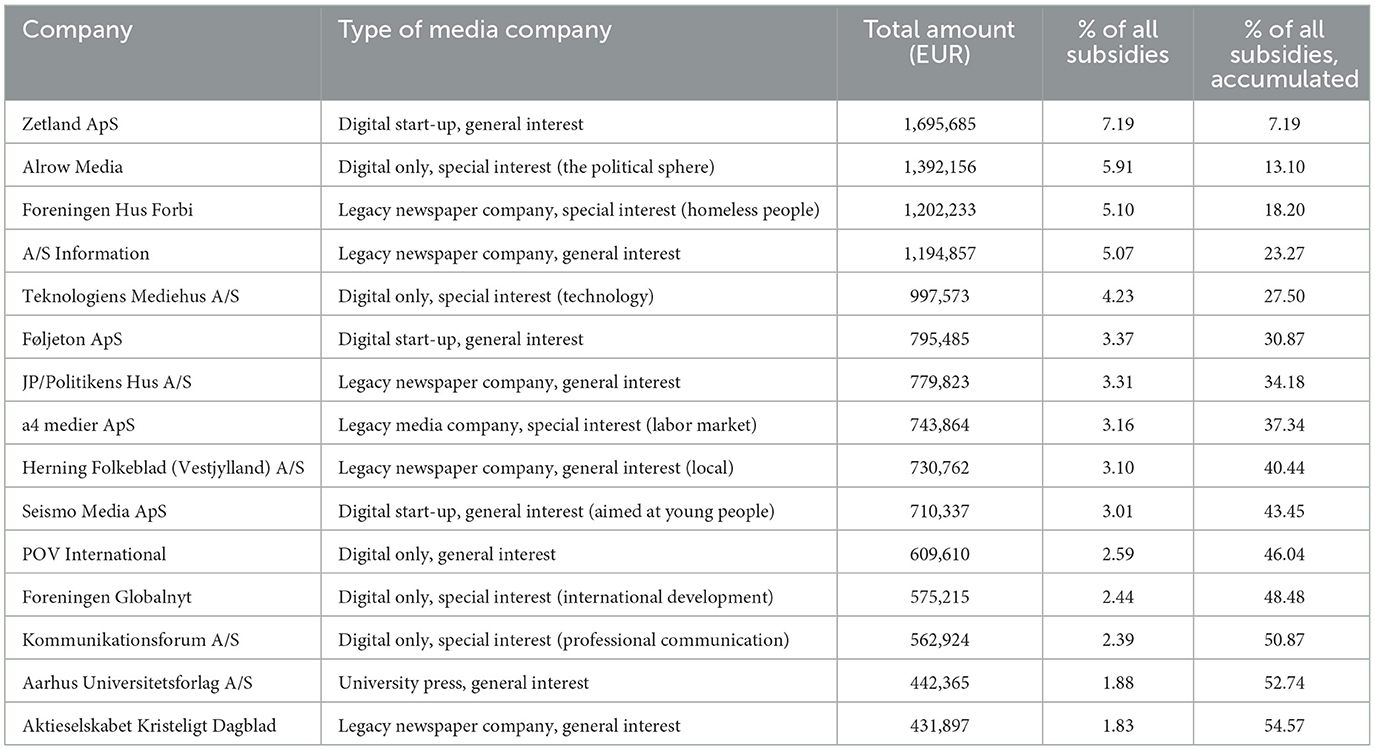

The allocation of the innovation subsidies is highly concentrated around a small number of companies: half of the total amount of innovation subsidies (11,990,522 EUR; 50.87 %) is allocated among only 13 of the 101 companies, three quarters (17,832,033 EUR; 75.65 %) among 32. This way, we observe the “Matthew principle” in effect as a small group accrues a disproportionately large share of the available resources. One company, Zetland ApS, accounts for no less than 7.19 % of all the funds that have been allocated as innovation subsidies for the news media.

Table 3 lists the 15 companies that have received the most funds. This group of companies consists primarily of digital start-ups (e.g., Zetland ApS and Føljeton ApS), pre-existing digtal media (e.g., Alrow Media and POV International), and legacy media from the newspaper sector (e.g., A/S Information and JP/Politikens Hus). One digital start-up (Zetland ApS) did exist as a company prior to receiving subsidies for establishment but used the funds as an occasion to restructure the company and its activities so fundamentally that it is, for all practical purposes, a new news medium.

The companies are mainly general-interest media, but there are exceptions: for example, Alrow Media's main activity is Altinget, which is a portfolio of sector-oriented online news media for actors in the political realm, while Teknologiens Mediehus A/S is a media company that focuses on covering technology in all ways, shapes, and forms.

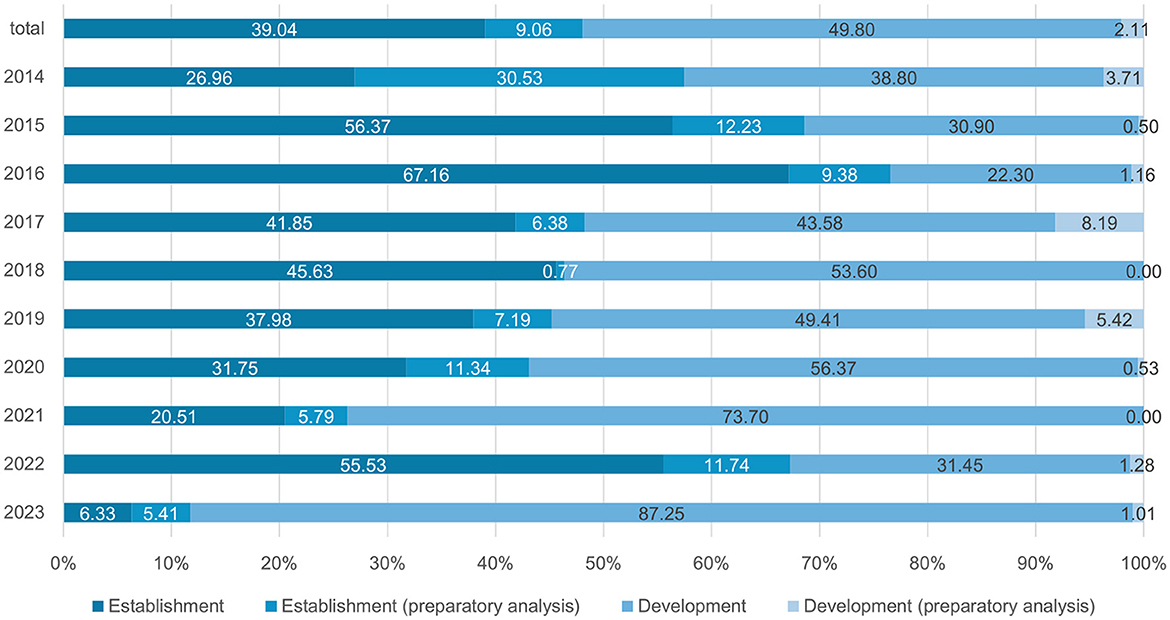

Both new and existing news media are eligible for innovation subsidies; new news media get funds for establishment, existing ones for development (digital transformation). Over the years, the distribution between the two types is almost equal with 48.09 % of the funds (11,337,513 EUR) going to new news media, 51.91 % (12,235,705 EUR) to legacy news media.

However, as Figure 1 illustrates, the distribution of funds within the four categories of allocations develops noticeably over the years. In particular, it is worth noticing how the innovation subsidies are increasingly allocated to development (i.e., to legacy media) rather than establishment: in the first half of the analyzed period of time (2014–2018), establishment accounts for 59.12 % of the total innovation subsidies, whereas it is only 37.26 % in the second half (2019–2023). This way, who gets subsidies changes over time, and this change suggests a structural shift in the subsidizing of news-media innovation in Denmark.

It should, however, also be noticed how the allocation of the subsidies obviously depends upon the applications; after all, the Agency for Palaces and Culture can only subsidize those that actually apply for subsidies. This way, the shift from establishment (of something new) toward development (of something existing) also reflects a shift in the body of applications for this subsidy. The amount of funds applied for in those applications for establishment that meet the formal criteria is simply smaller than that for development.

The empirical data for this study cannot reveal the reason behind this shift, but one probable explanation is that new news media that have “cracked the code” to getting subsidies continue to pursue this source of funding after establishment. For example, Føljeton ApS received subsidies for establishment in 2015 and later for development in 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023. This way, even though it is the same company, its subsidies register differently over the years in Figure 1.

RQ2: Which types of news-media innovation have been subsidized?

The next step of the analysis concerns the outputs of the news-media innovation subsidies, namely what is subsidized. To analyze that, we register the content of the application for innovation subsidies, noting which type of innovation is proposed in each case. We distinguish between five types of innovation, operationalizing the different foci of innovation that are mentioned in the legislation. These types largely correspond with, for example, García-Avilés et al.'s (2018) proposed categories for analyzing media innovation.

The types are:

• New technology or infrastructure (innovation that aims at implementing novel technology or infrastructure; e.g., AI).

• Product development (innovation that aims at developing a new product; e.g., an app or a podcast).

• Market development (innovation that aims at developing a new market; e.g., doing journalism for new audiences).

• Business development (innovation that aims at developing the business; e.g., payment models).

• Content development (innovation that aims at developing new content within existing products; e.g., particular types of journalism or the coverage of new subject areas).

Furthermore, an “other” category exists for the few instances of innovation that do not fit with the other one.

The analysis shows that overall, a little over one third (37.57 %) of the innovation subsidies 2014–2023 is allocated to content development. Examples of content development include the development of new content for younger news avoiders or of better ways to cover local debates. Around one fifth of the subsidies is allocated to product development and market development (23.62 % and 21.12 %, respectively). One example of product development is the development of a new app for tablets and mobile phones or the development of a new type of newsletter. Market development includes, for instance, the development of a new ultra-local newspaper to cater to an under-served segment of the population.

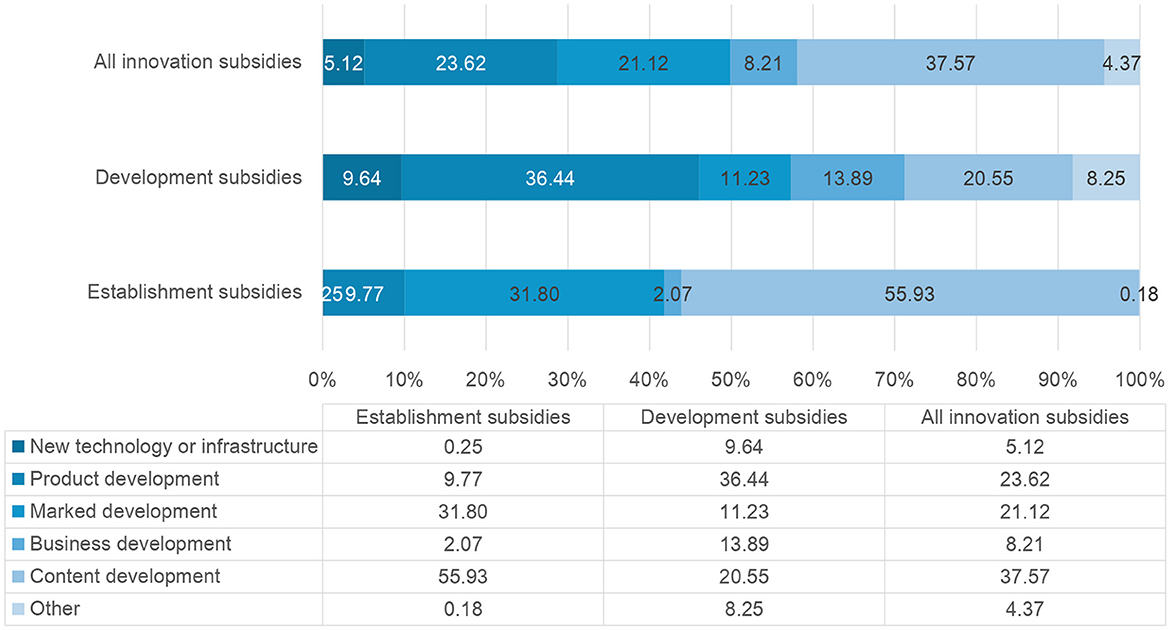

However, on the overall basis there is quite a difference between what new and legacy news media get subsidized. On the one hand, with the new news media (i.e., the subsidies for establishment), 55.03 % of the funds go to content development and 31.80 % to market development. This way, the new news media first and foremost aim at developing new types of content and at building new markets. An example of this is the Kids Newspaper aimed at children from nine to 12 years old. On the other hand, with the legacy news media (i.e., the subsidies for development), the emphasis is on product development (36.44 % of the funds) and to a lesser extent on content development (20.55 %). An example of product development is for instance a legacy newspaper developing a monthly digitized magazine linked to the newspapers brand. Figure 2 provides an overview of the allocation of innovation subsidies to different types of innovation, showcasing the difference between new and legacy media in terms of focus of innovation.

Figure 2. Innovation subsidies across different types of innovation and different types of subsidies, 2014–2023.

RQ3: Which new news media have emerged with the support of the innovation subsidies?

According to Bruno and Nielsen's (2012) research, mere survival should be considered success for news start-ups. Journalism is a resource-demanding activity, and establishing an organizational context for it is difficult.

RQ3 asks whether the allocation of funding from the innovation subsidies has led to the survival of new news media; or to put it in another way, how has the allocation of innovation subsidies supported the emergence of news media, increasing the diversity of the news media in the Danish media system. This way, the third research question inquires what the outcomes of the news-media innovation subsidies are.

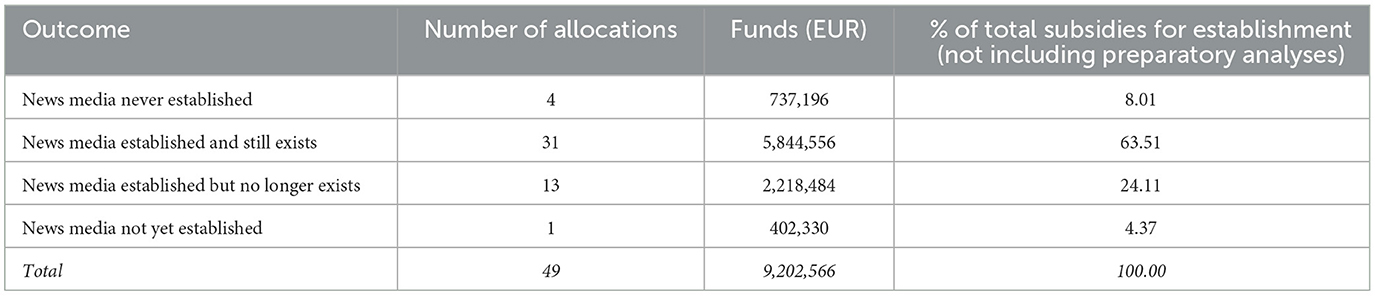

Table 4 lists the fate of the new news media that have received funds for establishment (only realization, not preparatory analysis). In total, there have been 49 allocations of this type of innovation subsidies, and 31 of these new news media still exist at the time of this writing; 13 have been established but no longer exist, four were never established, and one is currently in the process of being established. The analysis furthermore shows that 87.62 % of the innovation subsidies that were allocated to the establishment of new media (8,063,040 EUR out of a total of 9,202,566 EUR) went into new news media that actually came into being. The majority of these funds (a total of 5,844,556 EUR; 63.51 %) was allocated to new media that still exist at the time of this writing.

Table 4. The outcomes of innovation subsidies given to the establishment of new news media, 2014–2023.

These findings suggest that the innovation subsidies do contribute to the pluralism of the Danish news media as they support the establishment of a fair number of new news media in a fairly small country; this way, the innovation subsidies have, indeed, expanded the field of news and journalism in Denmark.

One further step in measuring outcomes is to look into how many new news media received innovation subsidies to then later move into the “ordinary” subsidy framework for established news media. Of the 31 new news media, 11 (Avisen.dk, Børneavisen, Fundats, Føljeton, InsideBusiness, Kulturmonitor, Politiken Skoleliv, POV International, ScienceReport, Seismo, and Zetland) have moved on to receive ordinary press subsidies; that is, they have grown sufficiently financially sustainable to move out of the sandbox of innovation and into the “established” news-media sector. Of the 20 remaining new news media, some are still subsidized through the innovation scheme, some are not eligible for the “ordinary” subsidies (which, e.g., comes with a prerequisite for more employees), and some apparently do not rely upon public subsidies as part of their business models onward.

RQ4: What impact has the innovation subsidies had on news use in Denmark?

Finally, to gauge the impact of the innovation subsidies, we measure the knowledge and use of the new news media (i.e., the news media that have been established with financial support from the innovation subsidies) among the adult Danish population.

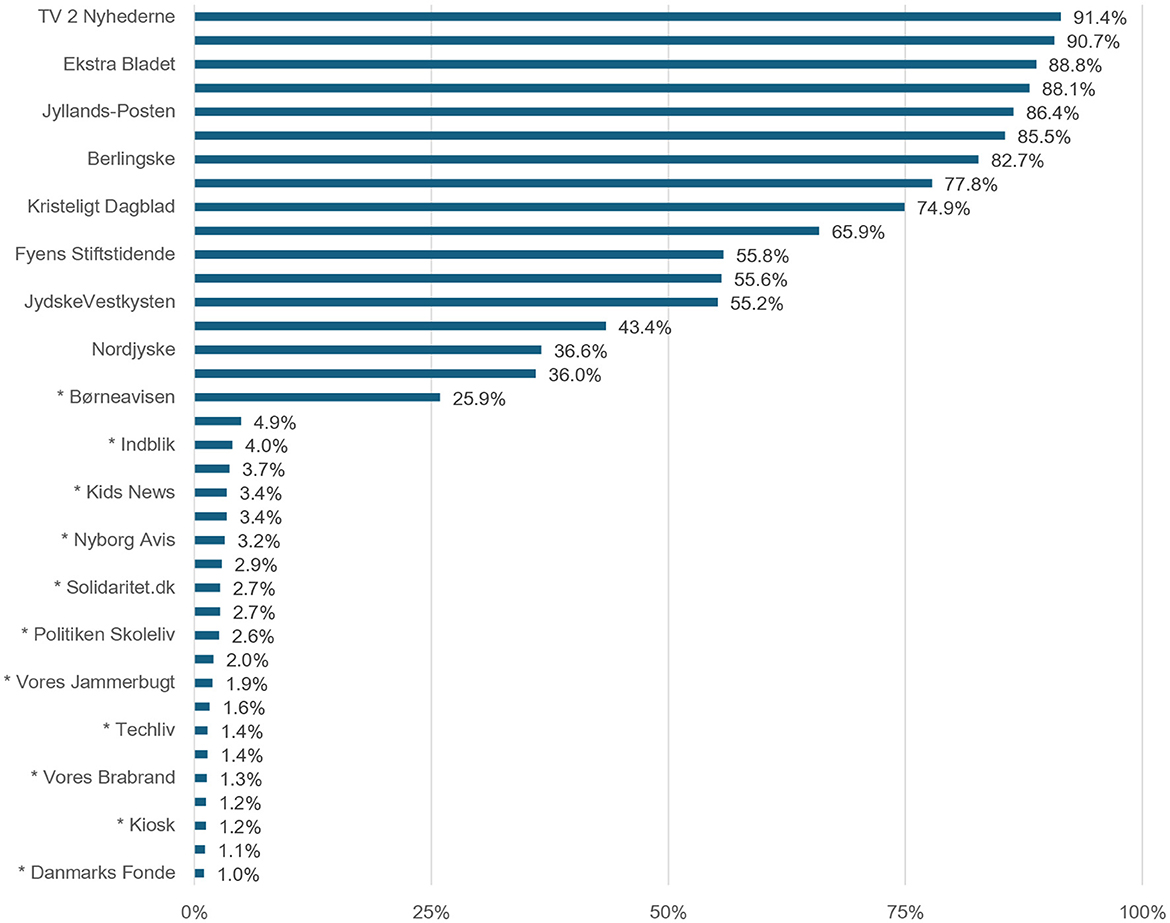

Figure 3 shows the proportion of adult Danes (18–75 years old) who “have heard of” the news media. It is clear that the legacy news media have the highest degree of brand recognition (a finding consistent with those of Schrøder et al., 2024). Among the new news media, Zetland (43 %) and Børneavisen (26 %) are the most widely recognized brands, while a large number of other new news media have much lower levels of recognition (>5 %).

Figure 3. Knowledge of Danish news media. Only news media known by more than 1 % of the respondents are included. New news media (established with financial support from the innovation subsidies) are marked with *. n = 3,020. Question: “Which of the following news media have you heard of?”

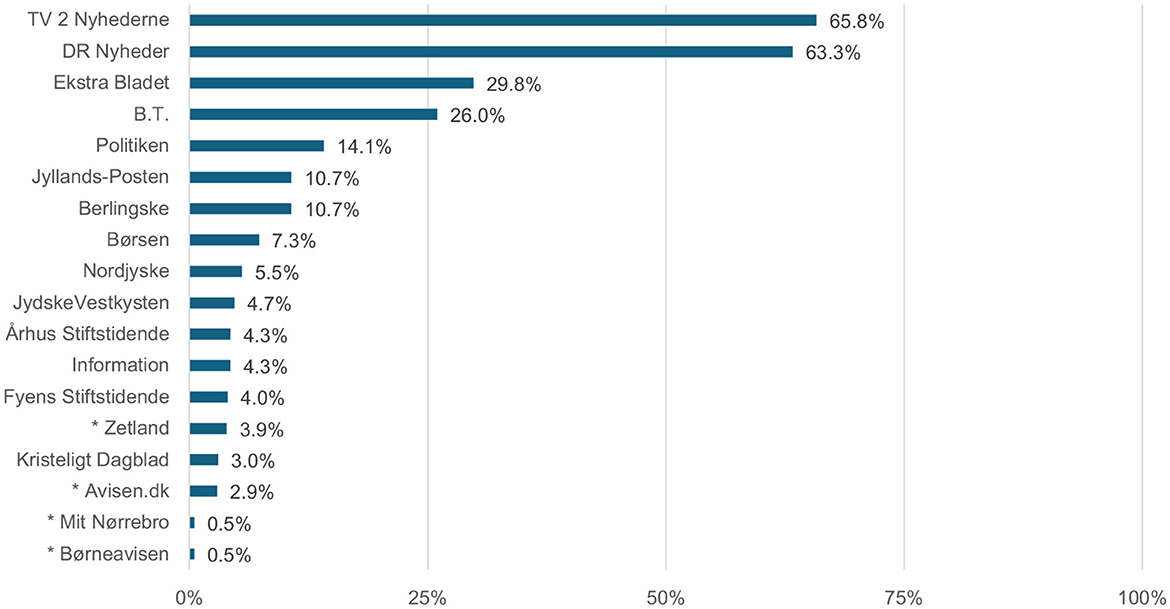

Gauging reach, Figure 4 shows how many respondents have used the news media in the past week. The pattern from the measurement of recognition repeats itself: the established news media score much higher than the new news media. Of the new news media, only one is used by more than one percent of the survey respondents, namely Zetland (3,9 %), whereas both Mit Nørrebro and Børneavisen5 are used by 0.5 %. The rest of the new news media are used by less than 0.5 % of the respondents.

Figure 4. Use of Danish news media. Only news media used by more than 0.5 % of the respondents are included. New news media (established with financial support from the innovation subsidies) are marked with *. n = 3,020. Question: “Which of the following news media have you used within the past week”?

Some of these figures may sound low, but for several reasons it is difficult to assess whether they represent a success or a failure of impact on behalf of the innovation subsidies. To begin with, the legislation behind the subsidy instrument does not specify what is “good enough”, and so there is no threshold to measure the reach of the new news media against. More importantly, however, many of the new news media target only limited groups of audiences (defined by, e.g., demographics or interests), and so they are unlikely in the first place to reach broad audiences. But that does not mean that they cannot contribute valuably to the communities they serve; a hyperlocal news website like Søften Nyt, for example, is irrelevant for the vast majority of the Danish population, but it can be immensely valuable for the people that reside in the small town of Søften.

Discussion

Whether public subsidies for news-media innovation are “good” or “bad” is ultimately a normative issue. And regardless of normativity, it is an empirical condition that within the media-systemic context of the Democratic Corporatist model, such state-intervention does figure prominently as a means to correct market failure and support policy goals.

To judge from the analysis, the Danish subsidy framework for news-media innovation has at the very least served the function it was designed to serve. Most importantly, this policy instrument has supported the emergence of a number of new news media, expanding and adding to the pluralism of the Danish news industry. One can of course discuss whether 31 still-existing new news media constitute “many” or “few”, and whether 11 of them transitioning from the innovation-subsidy framework to the ordinary one is “enough”—but given the relatively small size of the Danish press, 31 new news media do represent a notable addition, even if many of them are small, and even if many of them serve niche audiences.

That said, it should be noted how the analysis also indicates that the innovation subsidies are increasingly allocated to news media that already exist. One interpretation of this finding is that the pool of ideas for new news media is drying up, that the market is saturated and now more focused on consolidation rather than the establishment of something new. Another interpretation would be that the already-established news media, being in operation and having laid the groundwork, are in a better position for crafting the applications that lead to success in the pursuit of innovation subsidies. To better understand this dynamics, more empirical scrutiny (of successful as well as rejected application for the media-innovation subsidies) is necessary.

One limitation of this research is that it does not explore empirically the positive externalities that the innovation may have generated. Even failed news-media innovation (e.g., new news media that have later ceased to exist) can have contributed to informing the public, and it can have accommodated experimentation and knowledge-building among media organizations and professionals that can later be carried over to other contexts of journalism and media production. This way, the 13 new news media that were established with the support of the innovation subsidies but no longer exist can still be of long-term value for a news industry under pressure. Furthermore, the subsidies allocated to the development of legacy news media can contribute to the digital transformation of the news industry through supporting the entrepreneurial spirit within traditional media (see, e.g., Achtenhagen, 2008), even if we cannot assess it structurally through an analysis such as the one presented in this article. Mapping and assessing these types of added value through innovation is beyond the scope of this study, so more research is needed to fully grasp the impact of state-intervention through targeted media subsidies.

Conclusion

To sum up: analyzing the first decade of the Danish news media innovation subsidies, this article asked three research questions: who has received the innovation subsidies, which types of innovation have been subsidized, and which new news media have emerged with the support of the innovation subsidies?

The analysis shows that the subsidies are fairly equally distributed between new and legacy news media, but also that over the years, an increasing share of the innovation subsidies go to legacy media. The allocation of the innovation subsidies is somewhat concentrated around a small group of media companies. Furthermore, the analysis finds that for new news media, the primary forms of subsidized innovation relates to content and market (i.e., they aim at covering new topics and at serving new audiences), whereas legacy media first and foremost receive this type of funding to support the development of new products (e.g., apps or newsletters). And finally, the analysis shows that the majority of the new news media that have been established with the financial support of innovation subsidies still exist at the time of this writing—and that around one quarter of them (11 out of 49) have even survived to become sufficiently sustainable to have transferred to the ordinary press subsidies.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: Part of the dataset consists of business-sensitive information (about news organizations) that the Danish Ministry of Culture has granted us access to, which means this data cannot be made publicly available. Any further inquiries should be directed to the corresponding author, YXNrZWtAcnVjLmRr.

Author contributions

AK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MB-Ø: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was made with financial support from the Danish Ministry of Culture and the Foundation of the Danish Newspaper Publishers' Association (Dagspressens Fond).

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Eva Mayerhöffer and Anja Noster for thorough feedback on an early draft of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^It should be noted how in a Democratic Corporatist context (like the Danish one), such inspiration mainly manifests in the form of practical approaches to problem-solving (e.g., using design thinking as a way of developing solutions to problems) rather than ideological frameworks (e.g., the move-fast-and-break-things mentality).

2. ^The subsidy instrument came into effect with “Act on media subsidies” (Act no. 1604 of 26/12/2013), which was later amended through “Act on change of Act on media subsidies” (Act no. 472 of 17/05/2017), “Act on change of Act on media subsidies” (Act no. 1558 af 12/12/2023), and “Act on change of Act on radio and television entreprise etc. and Act on media subsidies” (Act no. 675 of 11/06/2024 §2). Furthermore, “Consolidation Act on media subsidies” (Act no. 127 of 05/02/2024) and “Consolidation Act on change of Consolidation Act on media subsidies” (Act no. 1488 of 06/12/2024) are in effect at the time of this writing.

3. ^1 EUR = 7.461 DKK.

4. ^Available through https://slks.dk/omraader/medier/skrevne-medier-trykteweb/innovationspuljen.

5. ^One caveat: Børneavisen is a newspaper for children, and so its intended target audience is not among the respondents for this survey (which are all adults, 18-75 years old). For this reason, additional analysis is necessary to more properly assess the impact of this particular new news medium.

References

Achtenhagen, L. (2008). Understanding entrepreneurship in traditional media. J. Media Busin. Stud. 5, 123–142. doi: 10.1080/16522354.2008.11073463

Belair-Gagnon, V., and Steinke, A. J. (2020). Capturing Digital News Innovation Research in Organizations, 1990-2018. Journal. Stud. 21, 1724–1743. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2020.1789496

Blach-Ørsten, M., and Mayerhöffer, E. (2021). The political information landscape in Denmark 2.0. Politica 53, 99–124. doi: 10.7146/politica.v53i2.130381

Boczkowski, P. (2005). Digitizing the News. Innovation in Online Newspapers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Boyles, J. L. (2016). The Isolation of Innovation. Restructuring the digital newsroom through intrapreneurship. Digit. Journal. 4, 229–246. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2015.1022193

Bruno, N., and Nielsen, R. K. (2012). “Survival is success,” in Journalistic Online Start-Ups in Western Europe (Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Oxford University).

Bruns, A. (2014). Media innovations, user innovations, societal innovations. J. Media Innovat. 1, 13–27. doi: 10.5617/jmi.v1i1.827

Buschow, C., Noster, A., Hettwer, H., Lich-Knight, L., and Zotta, F. (2024). Transforming science journalism through collaborative research: a case study of the German “WPK Innovation Fund for Science Journalism.” J. Sci. Commun. 23:23020802. doi: 10.22323/2.23020802

Cagé, J. (2016). Saving the Media. Capitalism, Crowdfunding, and Democracy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Carlson, M., and Usher, N. (2016). News startups as agents of innovation. For-profit digital news startup manifestos as metajournalistic discourse. Digit. Journal. 4, 563–581. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2015.1076344

Cornia, A., Sehl, A., and Nielsen, R. K. (2017). Developing Digital News Projects in Private Sector Media. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Oxford University.

de-Lima-Santos, M.-F., Munoriyarwa, A., Elega, A. A., and Papaevangelou, C. (2023). Google news initiative's influence on technological media innovation in Africa and the Middle East. Media Commun. 11, 330–343. doi: 10.17645/mac.v11i2.6400

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ettlie, J. E., Bridges, W. P., and O'Keefe, R. D. (1984). Organizational Strategy and Structural Differences for Radical versus Incremental Innovation. Manage. Sci. 30, 682–695. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.30.6.682

Fagerberg, J. (2006). “Innovation. A guide to the literature,” in Oxford Handbook of Innovation, eds. I. J. Fagerberg, D. C. Mowery, and R. R. Nelson (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1–26.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual. Inquiry 12, 219–245. doi: 10.1177/1077800405284363

García-Avilés, J. A., Carvajal-Prieto, M., De Lara-González, A., and Arias-Robles, F. (2018). Developing an index of media innovation in a national market. The case of Spain. Journal. Stud. 19, 25–42. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2016.1161496

Gerring, J. (2012). Mere description. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 42, 721–746. doi: 10.1017/S0007123412000130

Grueskin, B., Seave, A., and Graves, L. (2011). The Story So Far. What We Know About the Business of Digital Journalism. Tow Center for Digital Journalism, Columbia Journalism School.

Hallin, D. C., and Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing Media Systems. Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hermida, A., and Young, M. L. (2024). Google's influence on global business models in journalism: an analysis of its innovation challenge. Media Commun. 12, 1–16. doi: 10.17645/mac.7562

Humprecht, E., Herrero, L. C., Blassnig, S., Brüggemann, M., and Engesser, S. (2022). Media systems in the digital age: an empirical comparison of 30 countries. J. Commun. 72, 145–164. doi: 10.1093/joc/jqab054

Kaltenbrunner, A. (2024). “Media systems on the meta-level of change: How economy, tech development, and media policy create the framework for innovation in journalism,” in Innovations in Journalism: Comparative Research in Five European Countries, eds. K. Meier, J. A. García-Avilés, A. Kaltenbrunner, C. Porlezza, V. Wyss, R. Lugschitz, and K. Klinghardt (London: Routledge), 251–266.

Kammer, A. (2016). A welfare perspective on Nordic media subsidies. Journal of Media Business Studies 13, 140–152. doi: 10.1080/16522354.2016.1238272

Kammer, A. (2017). “Market structure and innovation policies in Denmark,” in Innovation Policies in the European News and Media Industry. A Comparative Study, eds. H. van Kranenburg (Cham: Springer International), 37–47.

Kammer, A., and Blach-Ørsten, M. (2025). The News-Media Innovation Subsidies 2014-2023. Roskilde: Center for News Research, Roskilde University.

Kangas, O., and Kvist, J. (2018). “Nordic welfare states”, in Routledge Handbook of the Welfare State, ed. B. Greve (London: Routledge), 124–136.

Keynes, J. M. (2006). The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (new edition). London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kline, S. J., and Rosenberg, N. (1986). “An overview of innovation,” in The Positive Sum Strategy: Harnessing Technology for Economic Growth, eds. I R. Landau and N. Rosenberg (Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press), 275–305.

Küng, L. (2017). Strategic Management in the Media. Theory to Practice (2nd Edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Lewis, S. C. (2011). Journalism innovation and participation: an analysis of the Knight news challenge. Int. J. Commun. 5, 1623–1648.

Lewis, S. C. (2012). From journalism to information: the transformation of the Knight foundation and news innovation. Mass Commun. Soc. 15, 309–334. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2011.611607

Lindmark, S., Ranaivoson, H., Donders, K., and Ballon, P. (2013). “Innovation in small regions' media sectors. assessing the impact of policy in Flanders”, in Media Innovations. A Multidisciplinary Study of Change, eds. T. Storsul and A. H. Krumsvik (Novi, MI: Nordicom), 127–144.

Lund, A. B., and Lindskow, K. (2011). Public media support, from postal privileges to license fees. Økonomi and Politik 84, 46–60.

Meier, K., García-Avilés, J. A., Kaltenbrunner, A., Porlezza, C., Wyss, V., Lugschitz, R., et al. (2024). Innovations in Journalism: Comparative Research in Five European Countries. London: Routledge.

Mesquita, L., and de-Lima-Santos, M.-F. (2023). “Google news initiative innovation challenge: technological innovation triggers by google grants,” in Digital Disruption and Media Transformation: How Technological Innovation Shapes the Future of Communication, eds. A. Godulla and S. Böhm (Cham: Springer), 55–70.

Murschetz, P. C. (2022). “Government subsidies to news media. Theories and practices,” in Handbook of Media and Communication Economics, eds. J. Krone and T. Pellegrini (Cham: Springer).

Myles, J. (1998). How to design a “Liberal” welfare state: a comparison of Canada and the United States. Soc. Policy Admin. 32, 341–364. doi: 10.1111/1467-9515.00120

Naldi, L., and Picard, R. G. (2012). “Let's start an online news site”: opportunities, resources, strategy, and formational myopia in startups. J. Media Busin. Stud. 9, 69–97. doi: 10.1080/16522354.2012.11073556

Nel, F. (2010). Where Else Is the Money? A study of innovation in online business models at newspapers in Britain's 66 cities. Journal. Pract. 4, 360–372. doi: 10.1080/17512781003642964

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Robertson, C. T., Arguedas, A. R., and Nielsen, R. K. (2024). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2024. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Oxford University.

Nielsen, R. K. (2012). Ten Years that Shook the Media World. Big Questions and Big Trends in International Media Developments. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford.

Nielsen, R. K., and Ganter, S. A. (2017). Dealing with digital intermediaries: A case study of the relations between publishers and platforms. New Media Soc. 20, 1600–1617. doi: 10.1177/1461444817701318

Noster, A. (2024). Ending the subsidies ice age: conceptualizing an integrative framework for the analysis of innovation policies supporting journalism. J. Inform. Policy 14, 104–131. doi: 10.5325/jinfopoli.14.2024.0003

Noster, A., Buschow, C., Kaltenbrunner, A., and Lugschitz, R. (2025). The role of policy mixes in enabling journalism innovation: a transnational study across five countries. Int. J. Commun. 19, 1511–1532.

Park, S., Fisher, C., Fulton, J., and Picard, R. (2024). News Industries: Funding Innovations and Futures. Canberra: News and Media Research Centre, University of Canberra.

Pavlik, J. V. (2013). Innovation and the future of journalism. Digit. Journal. 1, 181–193. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2012.756666

Picard, R. G. (2010). “A business perspective on challenges facing journalism,” The Changing Business of Journalism and its Implications for Democracy, eds. D. A. L. Levy and R. K. Nielsen (Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Oxford University), 17–24.

Posetti, J. (2018). Time to Step Away From the ‘Bright, Shiny Things'? Towards a Sustainable Model of Journalism Innovation in an Era of Perpetual Change. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Oxford University.

Powers, M., and Zambrano, S. V. (2016). Explaining the formation of online news startups in france and the united states: a field analysis. J. Commun. 66, 857–877. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12253

Price, J. (2017). Can The ferret be a watchdog? Understanding the launch, growth and prospects of a digital, investigative journalism start-up. Digit. Journal. 5, 1336–1350. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2017.1288582

Raboy, M., and Padovani, C. (2010). Mapping global media policy: concepts, framework, methods. Commun. Culture Critique 3, 150–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-9137.2010.01064.x

Schrøder, K., Blach-Ørsten, M., and Eberholst, M. K. (2024). Danes' Use of News Media 2024. Roskilde: Center for News Research, Roskilde University.

Schumpeter, J. (1950). Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (3rd ed.). New York, London: Harper Perennial.

Schützeneder, J. (2022). Buzzword – Foreign word – Keyword: The Innovation term in German media. J. Innovat. Managem. 10, 1–19. doi: 10.24840/2183-0606_010.001_0001

Sehl, A., Cornia, A., and Nielsen, R. K. (2017). Developing Digital News in Public Service Media. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Oxford University.

Sen, A., and Nielsen, R. K. (2016). Digital Journalism Start-Ups in India. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford.

Solvoll, M. K., and Olsen, R. K. (Eds.). (2024). Innovation Through Crisis. Journalism and News Media in Transition. Gothenburg: Nordicom

Søndergaard, H., and Helles, R. (2014). “Media policy and new regulatory systems in Denmark,” in Media Policies Revisited: The Challenge for Media Freedom and Independence, eds. E. Psychogiopoulou (London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan), 41–54.

Steensen, S. (2009). What's stopping them? Towards a grounded theory of innovation in online journalism. Journal. Stud. 10, 821–836. doi: 10.1080/14616700902975087

Storsul, T., and Krumsvik, A. H. (2013). “What is media innovation?,” in Media Innovations. A Multidisciplinary Study of Change, eds. T. Storsul and A. H. Krumsvik (Novi: Nordicom), 13–26.

Syvertsen, T., Enli, G., Mjøs, O. J., and Moe, H. (2014). The Media Welfare State. Nordic Media in the Digital Era. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

The Agency for Libraries and Media (2011). Demokratistøtte. Fremtidens offentlige mediestøtte [Democracy support. The future public support for media]. Copenhagen: The Agency for Libraries and Media.

Trappel, J. (2015). What to study when studying media and communication innovation? Research design for the digital age. J. Media Innov. 2, 7–22.

Usher, N. (2017). Venture-backed news startups and the field of journalism. Challenges, changes, and consistencies. Digit. Journal. 5, 1116–1133. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2016.1272064

Keywords: innovation, media systems, news media, policy, press subsidies

Citation: Kammer A and Blach-Ørsten M (2025) Subsidized news-media innovation: outputs, outcomes, and impact. Front. Commun. 10:1578463. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1578463

Received: 17 February 2025; Accepted: 25 June 2025;

Published: 24 July 2025.

Edited by:

Raquel Seijas-Costa, University of Malaga, SpainReviewed by:

Hilde Van den Bulck, Drexel University, United StatesManuel Puppis, Université de Fribourg, Switzerland

Copyright © 2025 Kammer and Blach-Ørsten. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aske Kammer, YXNrZWtAcnVjLmRr

†ORCID: Aske Kammer orcid.org/0000-0001-9114-5464

Mark Blach-Ørsten orcid.org/0000-0002-6787-105X

Aske Kammer

Aske Kammer Mark Blach-Ørsten

Mark Blach-Ørsten