- 1School of Foreign Studies, Anhui University, Hefei, China

- 2Faculty of Foreign Languages, Ningbo University, Ningbo, China

Introduction: Through variations in reporting volume and discursive strategies, the media communicates risks to the public and shapes perceptions during crises.

Methods: This study conducted a corpus-based, quantitative analysis of topoi in American newspapers during the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, comparing media representations of unemployment.

Results: It identifies four recurrent topoi common to both crises that characterize media coverage of unemployment. However, differences in other recurring topics reflect variations in the distinct causes of the crises, unemployment dynamics, and social policy responses.

Discussion: These findings highlight the media’s distinct influences on the evolution of each crisis and its portrayal of unemployment. By examining how media strategies shape discourse on unemployment, this study deepens our understanding of the interplay between media, discourse analysis, and crisis management during major economic disruptions.

Introduction

The first two decades of the 21st century witnessed the emergence of two major crises in the U.S. and the world: the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The financial crisis began in August 2007 with the collapse of the U.S. subprime mortgage market and eventually escalated into a global recession—the most severe since World War II (Verick and Islam, 2010, p. 20). In contrast, the 2020 crisis was triggered by a novel virus that rapidly spread worldwide, claiming at least 1.46 million lives in the U.S. (WHO, 2021) and significantly disrupting economic development (Gourinchas, 2020).

For both crises, extensive research has been conducted from the perspectives of economics and crisis management, focusing on their causes, consequences, and policy responses (Verick and Islam, 2010; Alizadeh et al., 2023). Additionally, they serve as intriguing subjects for media studies, where the performance and roles of the media are scrutinized and assessed (Schiffrin, 2015; Yu and Yang, 2024). Within linguistics, critical discourse analysis has explored the discursive strategies employed in news articles covering these crises (Rice and Bond, 2013; Yu et al., 2021). In recent years, comparative studies have emerged to provide retrospective insights for addressing future challenges, particularly in areas such as unemployment (Scanni MSG, 2021), employment inequality in the U.S. (Fazzari and Needler, 2021), and social policy (Moreira and Hick, 2021).

Despite their differing origins, characteristics, and scales, the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic COVID-19 pandemic profoundly disrupted global economies, particularly employment (Verick and Islam, 2010; Suran, 2023). The widespread job losses in these crises dominated news coverage, fueling intense public discourse. Comparing media portrayals of unemployment during these periods reveals how coverage shapes public perceptions of economic fallout, influences policy responses, and enhances public understanding, offering critical insights for developing effective communication strategies in future crises. To date, except for several comparative studies exploring the causes and extent of unemployment from a public policy perspective (Scanni MSG, 2021; Moreira and Hick, 2021), there has been limited research comparing U.S. media representations of unemployment across the two crises, particularly through the lens of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), an interdisciplinary approach that explores how discourse reflects, reproduces, and challenges power relations, ideologies, and social inequalities (Fairclough, 2013, p. 4).

Specifically, this study will examine how U.S. media reconstructed unemployment during the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, utilizing the argumentative shortcuts known as topoi within the Discourse-Historical Approach (DHA). As recurring rhetorical strategies, topoi will enable the systematic analysis of media discourse, revealing how ideological and power dynamics shape public perceptions and policy responses in these distinct crisis contexts. Through a quantitative analysis of argumentation strategies in news articles from two major U.S. outlets, The New York Times and USA Today, in 2008 and 2020, this research explores the interplay between topoi and the socio-economic conditions surrounding unemployment, offering insights into how media reports reflect and influence crisis-specific dynamics.

Literature review

Critical discourse analysis of unemployment

Unemployment poses challenges at individual, communal, and national levels. Investigating unemployment through the lens of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) constitutes a multidisciplinary endeavor, drawing on linguistics, economics, political science, media studies, and psychology. Typically, such analyses focus on two primary aspects: (un)employment policies and the portrayal of unemployment.

CDA studies examining (un)employment policies, using diverse theories and methodologies, dissect the discursive construction of unemployment across various genres, including policy documents, political addresses, and media narratives. Van Leeuwen (1999) and Wodak and Leeuwen (2002), for instance, scrutinize social actors and legitimation strategies within budget speeches of British and Austrian chancellors, as well as media reports, assessing how government, employers, employees, and their roles in (un)employment processes are depicted, both by governmental entities and the media. Other methodologies have been employed in similar analyses, such as the utilization of genre and register theory from systemic functional linguistics to examine EU employment guidelines (Muntigl, 2002), sociolinguistic analyses of texts from advisory groups and the European Parliament addressing mass unemployment (Weiss and Wodak, 2000), and a critical policy discourse analysis of the Australian new employment services model (Papadopoulos and O’Keeffe, 2024).

While CDA researchers also attend to the discursive representation of the unemployed, this aspect receives comparatively less scrutiny than government policies and media texts on unemployment. Studies reveal that the unemployed are often stigmatized by political figures and media outlets. McArthur and Reeves (2019) for instance, utilizing a dataset measuring the frequency of stigmatizing language about people in poverty in centrist and right-wing newspapers throughout the twentieth century, find that stigmatizing rhetoric about the poor intensifies during periods of rising unemployment, with exceptions during deep recessions. Okoroji et al. (2021), employing a multi-method approach to explore the social psychological construction of stigma toward the unemployed, support the assertion that the stigmatization of the unemployed is linked to political discourse and media elites. Furthermore, CDA analyses of narratives recounting the experiences of the unemployed offer insights into how individuals comprehend and attribute meaning to their circumstances. Blustein et al. (2013) conducted a narrative analysis of interviews with unemployed and underemployed adults, revealing their interpretations of and coping mechanisms for job loss.

As shown in the previous review, to date, little attention has been paid to unemployment in the sphere of CDA, and no studies have been conducted comparing the media representation of unemployment during the 2008 and 2020 crises. This study, using corpus from two major U.S. newspapers and the topoi theory from DHA, attempts to make a corpus-based, quantitative comparison of the use of topoi in the news articles on unemployment in the 2 years, and by drawing on the sociopolitical and economic contexts of the 2008 and 2020 crises, seeks to explain the similarities and variations in media representations of unemployment through the identified topoi. Specifically, the study will address the following questions:

(1) How do U.S. newspapers employ topoi to reconstruct unemployment rhetorically in their coverage of the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, and what similarities and differences emerge in these argumentative strategies?

(2) How do topoi in U.S. newspaper coverage of unemployment during the 2008 financial crisis and 2020 pandemic reflect and influence the socio-economic and policy contexts, particularly unemployment dynamics and social policy responses?

DHA and topos

DHA is an approach to critical discourse analysis that “attempts to integrate much available knowledge about the historical sources and background of the social and political fields in which discursive ‘events’ are embedded” (Reisigl and Wodak, 2005, p. 35). As an interdisciplinary approach, it follows the principle of ‘triangulation,’ which entails incorporating a wide range of empirical observations, theories, and methods, as well as background information, into account (Reisigl and Wodak, 2016). Among the approaches used in DHA’s triangulation is the theory of topoi.

Topoi in argumentation theory can be described as parts of argumentation that belong to the obligatory, either explicit or inferable, premises (Reisigl and Wodak, 2005, p. 74). Being the content-related warrants or ‘conclusion rules’ that connect the argument or arguments with the conclusion, the claim, they justify the transition from the argument or arguments to the conclusion (Kienpointner, 1992, p. 194). In argumentative discourse on virtually any topic, topoi are often analyzed as an abstractable pattern of reasoning to help analyze the structure and content of arguments, typically in the form of conditional or causal paraphrases such as ‘if x, then y’ (Reisigl, 2014, p. 75). Their application in argumentation analysis involves identifying the relevant topos for a given argument and analyzing how it is used to support or challenge a particular claim. By examining topoi, we can delve deeper into the context surrounding specific issues and topics present in the dataset (Wodak, 2009).

Because argumentation is ‘always topic-related and field-dependent,’ topoi can also be considered as ‘recurrent content-related conclusion rules that are typical for specific fields of social actions’ (Reisigl, 2014, p. 77). The theory has been applied to the analysis of texts on diverse issues, such as the representation of immigrants and asylum seekers in far-right political leaflets (Richardson and Wodak, 2009), environmental rhetoric (Ross, 2012), and the construction of value in introductions of science research articles (Carter, 2021). The numbers of typical topoi are also varied in discourses of different fields. For example, Wodak (2001) identified 15 topoi in the analysis of discourse on immigrants, Ross (2012) yielded 12 in the analysis of environment discourse, and Wodak (2009) listed 9 in analyzing legitimization strategies and identity construction.

In this study, we will examine how topoi reconstruct unemployment in news media during the 2008 and 2020 crises and explore the extent to which their use reflects the socio-political and economic contexts surrounding unemployment.

Research design

Data collection

To investigate unemployment discourse during the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, we retrieved articles from the LexisNexis database, focusing on two leading U.S. newspapers: The New York Times (NYT) and USA Today (USAT). These outlets were selected for two reasons. First, both are among the most influential newspapers in the U.S. NYT, with 9.13 million total subscribers, is the most widely read newspaper among U.S. digital news consumers and a globally recognized mainstream outlet (Pengue, 2023). USAT, with 2 million digital subscribers, ranks fourth in online circulation among U.S. newspapers, reflecting its broad national reach (Reft, 2022). Second, their contrasting reporting styles enable a comprehensive analysis of topoi in unemployment discourse. NYT’s elite, policy-oriented perspective, characterized by in-depth analysis (Hicks and Wang, 2013; Pengue, 2023), complements USAT’s mass-oriented, narrative-driven style, which emphasizes personal stories and emotional resonance (Gannett, 2020). This duality facilitates a robust examination of rhetorical strategies across elite and popular media during the 2008 and 2020 crises.

The unemployment-related terms, including ‘layoff*,’ ‘lay* off,’ ‘laid off,’ and ‘unemploy*,’ were utilized to search articles in the two newspapers where each term was mentioned at least once. The collected articles span two periods: from 1 January 2008/2020 to 31 December 2008/2020. The year 2008 was selected for data collection of the first crisis because it was the phase when the financial crisis was in full bloom (Verick and Islam, 2010, p. 3). Key events, such as the collapse of Lehman Brothers, made the media coverage of that year the most representative in terms of both quantity and depth. Similarly, 2020 marked the initial year of the pandemic, during which unemployment rates reached unprecedented levels worldwide due to lockdown measures and business closures (Nicola et al., 2020).

Text preprocessing and cleaning

After the data collection process, text cleaning procedures were performed using Python to remove duplicate articles and URL addresses. Additionally, articles related to countries other than the United States were removed. The refined dataset comprises 8,182 articles, totaling 10,719,770 words, with 2,559 articles in the 2008 corpus and 5,623 in the 2020 corpus.

Topoi identification

The identification procedure consisted of four steps. To begin with, we established a framework for identifying topoi in unemployment discourse. Through the close reading of news articles on unemployment, we found significant similarities between unemployment discourse and discourse on immigrants. For example, both unemployment and immigration were considered undesirable and had negative effects on society. Therefore, the most common topoi used by Wodak (2001, 2009) in the analysis of discrimination and immigration discourse were applied in this study as the basic analytical framework. However, to better adapt them to the context of unemployment, they were redefined. In addition, to avoid overlapping definitions, the topos of Finances was combined with Burdening because it is closely related to the latter (Wodak, 2001, p. 78), especially in the context of unemployment discourse. As a result, we compiled a list of 16 topoi for analyzing unemployment discourse.

Second, after all the concordance lines bearing unemployment-related words were searched with the use of AntConc (version 4.0.1), 25% of the data was sampled with the help of the conc_sampler tool (Liang et al., 2010), which resulted in 679 and 2,528 concordance lines from the 2008 and 2020 corpora, respectively.

Third, a preliminary identification of the topoi was conducted under the framework of 16 topoi. A total of 3,200 randomly selected concordance lines were coded by the two authors independently to examine the applicability of the framework. To discern what topos was at work in the sentence about unemployment or the unemployed, we related the sentence containing the concordance line with the claim made in the passage. If it was still difficult to identify the topos, a larger context was considered. In the preliminary analysis, the inter-rater reliability was 0.78. The discrepancies were reconciled with collaborative discussion, and the formulations were refined until an agreement was reached (The framework for topoi identification is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29125847.v1).

Finally, the sampled data were independently processed by the two authors, each coding half of the data. Ambiguous cases were compiled and resolved through discussion between the authors to ensure consistency.

The sampled concordance lines were formatted and coded in TXT files. Upon completion of the coding, AntConc was used to calculate the frequencies of the topoi identified in the data, and the chi-square analysis of the topoi used in the two sampled corpora was conducted using Python.

It should be noted that not all sentences containing unemployment-related words were used as argumentation strategies, such as in the news title ‘a place for the unemployed, not tourists’. These cases were considered to have no topoi and were thus excluded from the data. In the 2008 and 2020 samples, 64 and 75 concordance lines were excluded, respectively, leaving 615 and 2,453 qualified cases in the two samples.

Data analysis

Media coverage and unemployment

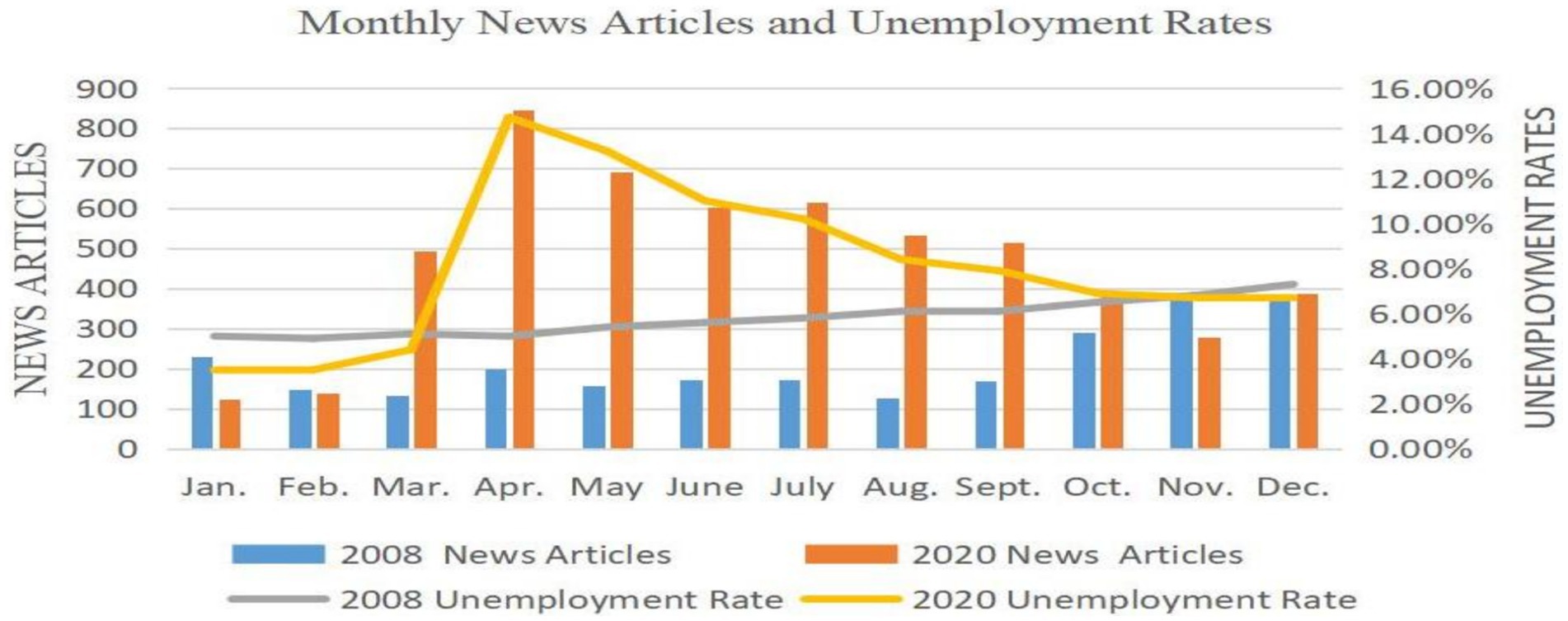

Both the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic led to economic downturns and job losses, which inevitably became focal points for news media. Figure 1 below juxtaposes the U.S. unemployment rates reported by the American Labor Force and unemployment-related media coverage in The New York Times (NYT) and USA Today (USAT) in 2008 and 2020.

Figure 1. Media coverage on unemployment and U.S. unemployment rates in 2008 and 2020. The x-axis of the chart represents the 12 months of 2008 and 2020. The bars denote the number of unemployment-related news reports on The New York Times (NYT) and USA Today (USAT) in 2008 and 2020, indicated by the numerical values on the left y-axis. The two lines display the fluctuations of unemployment rates in the 2 years, represented as percentages on the right y-axis.

Two conclusions can be drawn from the above chart. First, there is a clear correlation between the number of news articles and unemployment rates in both years. Peaks in news coverage correspond closely with peaks in unemployment rates, indicating that media attention intensifies during periods of higher unemployment. Pearson’s correlation analysis confirms a significant relationship between news coverage and unemployment rates in 2008 and 2020 (r = 0.739, p < 0.01; r = 0.908, p < 0.01). This supports a rather generalizable pattern in economic news reporting: negativity bias—the tendency to systematically devote more attention to negative than to positive economic trends (Damstra et al., 2018, p. 2).

Secondly, Figure 1 reveals distinct patterns in the evolution of unemployment and associated news coverage across 2008 and 2020. In 2008, unemployment rates rose steadily throughout the year, increasing from 5% in January to a peak of 7.3% in December, driven by the financial crisis (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2008). By contrast, 2020 saw more dramatic fluctuations, with unemployment rates surging from 4% in March to a high of 14.7% in April—the highest since the Great Depression (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020)—followed by a gradual decline through the end of the year. These distinct patterns highlight how crises of differing origins and severities shaped unique unemployment trends and their corresponding media narratives.

The use of topoi in news articles on unemployment

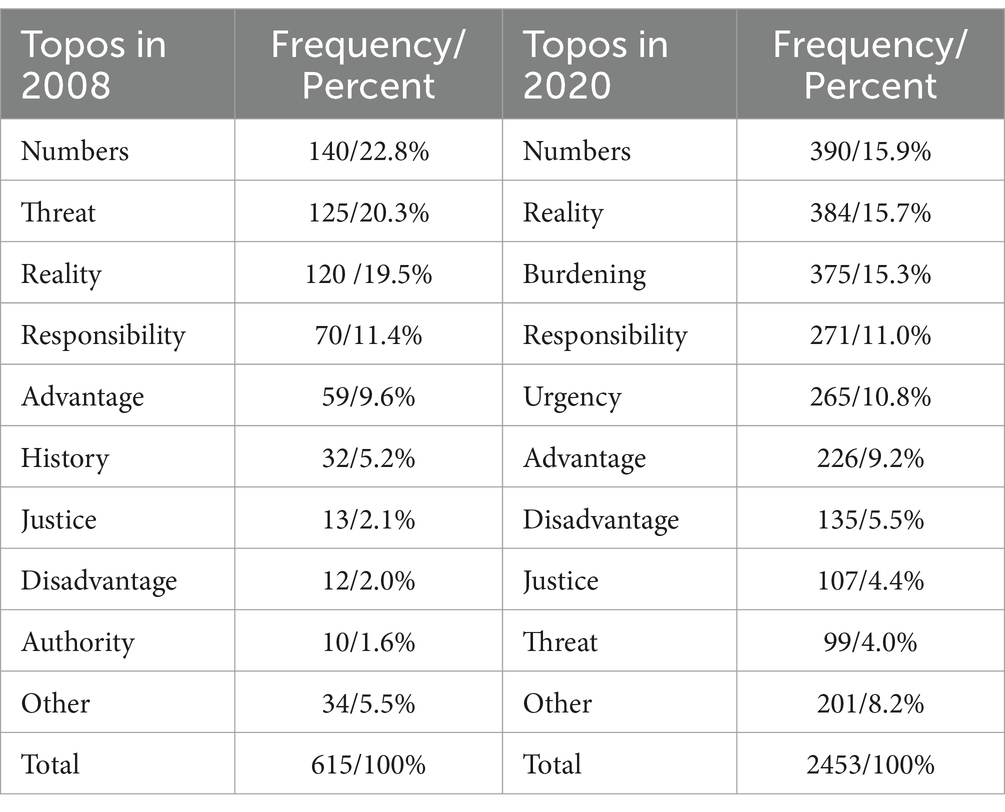

Table 1 below summarizes the results of identifying topoi in the sampled corpora from 2008 and 2020. Although all 16 topoi were present in the sampled data of this study, some, such as Numbers and Reality, appeared frequently, while others, such as Definition and Culture, occurred infrequently. The chi-squared test result indicates a highly significant difference in the distribution of topoi between 2008 and 2020 (χ2 = 548.54, p < 0.001).

The results show that the top six topos account for 88.8 and 77.9% of the 2008 and 2020 samples, respectively. As our focus was on prevailing topoi in this discourse, we analyzed the top 6 topoi in each corpus. As presented in Table 1, the two sampled corpora share four common topoi but diverge in the use of the other 2.

Shared recurrent topoi in 2008 and 2020 samples

In both crises, four rhetorical strategies were consistently employed in news articles as primary means of reconstructing unemployment: numbers, reality, responsibility, and advantage, which are characteristic of unemployment discourse. The Numbers topos, topping both lists, aims to represent the state of unemployment through statistical data. Following Wodak’s (2009) formulation, it is defined in the context of unemployment as: “If sufficient (or insufficient) numerical/statistical evidence regarding unemployment is provided, measures should be taken to address the situation.” By reporting current unemployment rates or the number of unemployed individuals, this topos informs the public about the scale of unemployment or illustrates its progression amid changing economic conditions (or the impact of a pandemic). This is demonstrated by the two excerpts:

(1) NYT, 24 December 2008.

The Labor Department said initial applications for unemployment benefits rose more than anticipated to a seasonally adjusted 586,000 the week ending May 2.

(2) NYT, 5 December 2020.

The national picture mirrors what is happening in New York. Across the country, the overall unemployment rate for November was 6.7%, but it was 10.5% for individuals aged 20 to 24 years.

In these examples, the numbers topos, either presented as the number of unemployment benefit applications or as percentages, serve as an effective strategy to inform the public and policymakers about the unemployment situation, thereby prompting responsive actions.

Notably, there are subtle differences in how the Numbers topos presents unemployment across the 2 years. While percentages and cardinal numbers dominate in both periods, the term ‘million(s)’ is particularly frequent in the 2020 sample, appearing in 40.8% of the cases identified as Numbers (159/390). In contrast, it appeared in only 11.4% of such cases in 2008 (16/140). In 2020, ‘million(s)’ was often used to describe the number of people seeking or receiving unemployment benefits since March 2020, as shown in the following example:

(3) NYT, 27 December 2020.

More than 20 million Americans are collecting unemployment benefits, and the unemployment rate stands at 6.7%.

In example (3), the figure ‘20 million’ is striking, especially when compared to the total job loss of 8.7 million during the 2008 crisis (Fazzari, 2020). The frequent use of ‘million(s)’ in 2020 highlights the unprecedented scale and speed of mass layoffs in the early months of the COVID-19 crisis, underscoring the urgent need for government intervention (Barbieri Góes and Gallo, 2021).

Similar to Numbers, the Reality topos, defined as ‘Because this is the reality of unemployment concerning the country or individuals, a specific action or decision should be taken,’ is also a common strategy in media portrayals of unemployment. Unlike Numbers, it focuses on providing a qualitative description of unemployment rather than relying on statistics, as illustrated in the following extract:

(4) NYT, 4 December 2020.

Small companies would like a bailout?,” said Heather Davison, who lives in Davisburg, less than an hour north of Detroit, and has been unemployed for a year.

Rather than using numerical data, this example highlights the lived reality of an individual who is unemployed. This topos is particularly prevalent in sentences that report the conditions of the unemployed during the crisis.

The Responsibility topos, defined here as ‘Because a state, organization, or group of individuals is deemed responsible for the emergence of unemployment or its mitigation, they should take appropriate actions,’ highlights the obligations of relevant entities during crises. In this sense, it aligns with the blame strategy (Simonsen, 2024), though in this study, it also encompasses responsibility for alleviating issues. Similarly, the Advantage topos, defined as ‘If a decision or action is beneficial in helping the country or individuals out of difficulty, it should be implemented,’ focuses on the potential benefits or usefulness of various stimulus policies and relief measures. These two topoi are particularly prevalent in debates about who should bear responsibility for the problems and their solutions, as well as what policies should be adopted to address them. They are illustrated in the following excerpts:

(5) NYT, 17 April 2020.

We should also address glaring deficiencies in our social safety net, as laid bare by the crisis, such as the inadequacies of healthcare, paid leave, unemployment insurance, and food stamps. And that leads to the final issue for policymakers. The federal government can—and should—continue to borrow vast amounts to address the current crisis.

(6) NYT, 17 April 2020.

Allowing drivers to receive the new federal benefits rather than traditional unemployment assistance could help gig-economy companies, such as Uber and Lyft, avoid significant costs in the future.

In example (5), the newspaper emphasizes the federal government’s responsibility to address shortcomings in the social safety net to support individuals during the pandemic. In contrast, the Advantage topos in example (6) highlight the value of extending new federal benefits to drivers previously ineligible for unemployment insurance (UI) benefits, benefiting both the drivers and gig economy companies.

In conclusion, the four topoi—Numbers, Reality, Responsibility, and Advantage—are extensively employed in news media to reconstruct unemployment during the two crises, aiming to inform, engage, and influence both the public and the government. The first two topoi, through the presentation of statistics and factual accounts, seek to portray an accurate picture of unemployment and the unemployed during the crises. Building on this foundation, Responsibility is utilized to urge governments or institutions to take action, while Advantage highlights the potential benefits of policies and measures implemented to alleviate unemployment and support the unemployed. This reveals a coherent, logical progression in the application of these four topoi within the unemployment discourse.

Different topoi in 2008 and 2020 sampled corpora

As presented in Table 1, notable divergences exist between the two sampled corpora in their top 6 topoi, largely reflecting the distinct contexts surrounding unemployment during the two crises. The Threat and History topoi rank higher in the 2008 corpus. Drawing on Wodak (2001), the Threat topos in this study is defined as: ‘If specific dangers or threats, such as a recession, are identified, a specific action or decision should be taken.’ This is exemplified in the following extract:

(7) NYT, 12 January 2008.

The tone changed quickly over the last few weeks, especially after the unemployment rate increased, oil prices reached $100 a barrel, the stock market declined, and the housing crisis worsened. Leading Republican and Democratic economists soon began voicing concerns about a recession, with some even suggesting that one had already begun.

In this example, the rise in unemployment, combined with other economic challenges, poses a threat to the economy, potentially leading to a recession.

The Threat topos ranks second in the 2008 sample (20.3%), with 47.2% (59/125) of its instances occurring in contexts that predict dangers stemming from the current economic challenges. From the media’s perspective, the economic situation in the U.S. in 2008 was still deteriorating, and rising unemployment rates were considered a key indicator of an impending recession or even a broader economic crisis. An analysis of the two corpora reveals that ‘recession(s)’ was mentioned far more frequently in 2008 than in 2020 (678 vs. 278 occurrences per million words). However, the media’s interpretation of unemployment and its warnings in 2008 appear to have been largely overlooked by most economists at the time, though they were later substantiated by retrospective post-crisis studies (Verick and Islam, 2010).

Subsequently, the History topos, which also ranked highly in the 2008 sample, provides a historical perspective on the economic conditions of that year, emphasizing the importance of learning from past experiences. Drawing on Wodak (2001), the History topos in this study are identified when unemployment is examined from a historical viewpoint, suggesting that a specific action should or should not be taken, as illustrated in example (8):

(8) NYT, 7 November 2008.

Only 32% of all unemployed people were receiving state benefit checks in October due to restrictions on eligibility. More than half of all unemployed people drew benefits in the 1950s, and approximately 45% received state checks during the last recession in 2001.

In example (8), where the argument advocates for extending state benefits to more unemployed individuals, historical statistics on benefit recipients during the previous two recessions are provided to support this claim. Thus, it is classified as the History topos. In the 2008 sample, 71.9% (23/32) of the instances identified as history compared the economy or unemployment in 2008 with those during the 1980s recession or the Great Depression. This approach, on the one hand, helps readers understand the severity of economic and unemployment conditions; on the other, by reflecting on the past, it encourages contemporary policymakers to draw lessons from history and avoid repeating past mistakes. This argumentative strategy suggests that the 2008 financial crisis was a crisis of economic growth (Moreira and Hick, 2021). Insights and lessons derived from similar historical crises can contribute to addressing the challenges of this one.

On the other hand, the Urgency and Burdening topoi, which rank higher in the 2020 data, emphasize the scale and pace of unemployment during the pandemic. The urgency topos, reformulated as ‘Because of an external, significant, and unchangeable event beyond one’s control and responsibility, such as unemployment, decisions or actions must be made swiftly,’ highlights the emergency nature of the situation and the need for rapid responses as a result of the unprecedented impact of the pandemic in terms of its magnitude and its scope (Stanca and Tarbujaru, 2022, p. 2). It was frequently employed to argue for the necessity of new unemployment programs to address the financial challenges faced by the unemployed, particularly in the initial months of 2020, when containment measures displaced millions of Americans, and in the final months, when some temporary unemployment programs were set to expire by year’s end. In response to this crisis, Urgency was used in news reports to urge prompt decisions and actions from governments, as demonstrated in the following example:

(9) NYT, 11 November, 2020.

Two critical unemployment programs are set to expire at the end of the year, potentially leaving millions of Americans vulnerable to eviction and hunger.

Example (9) calls for swift congressional action as unemployment programs enacted in spring 2020 neared their end-of-year expiration. The intense media focus on the urgent conditions of the unemployed played a key role in shaping government decision-making on jobless aid (Weible et al., 2020). For instance, on March 27, 2020, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act—the largest single relief package in U.S. history (Gape, 2023)—was signed, allocating $268 billion for expanded unemployment insurance benefits. Similarly, on December 21, 2020, the Curatola (2021) was enacted to provide further economic relief, as some of these programs expired at the end of 2020 (Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2021).

The Burdening topos, reformulated in this context as ‘If the unemployed, a system, or the national (state) budget is burdened by specific issues, decisions or actions should be taken to alleviate these burdens,’ highlights the pressure imposed by prolonged mass job losses on individuals, government budgets, or the unemployment system. This is exemplified in the following extract:

(10) NYT, 29 May, 2020.

The city is far from alone in confronting an economic collapse. New York State is expecting as much as $13 billion less in tax revenue this year; California faces a $54 billion budget deficit, and Los Angeles has a 24% unemployment rate.

This excerpt illustrates the economic strain on state budgets due to unemployment benefit payments, which became increasingly burdensome as the pandemic and unemployment persisted. The use of Burdening as an argumentative strategy underscores the pressure exerted by various policy responses and highlights the need for more effective measures to reduce these burdens.

Discussion

The use of topoi and the context surrounding unemployment

The above analysis reveals intriguing commonalities and divergences in the application of topoi within the unemployment discourse during the two crises. On the one hand, the four topoi—Numbers, Reality, Responsibility, and Advantage—are employed by the media as consistent strategies to represent and frame the impact of mass job losses. On the other hand, the recurrent use of these topoi is closely tied to the contexts surrounding unemployment, including the nature of the recessions, the characteristics of unemployment, and the social policies implemented by governments.

To begin with, the differing topoi employed in news articles reflect the media’s understanding of the varied causes and nature of the 2008 and 2020 crises, as well as their associated unemployment. The 2008 crisis, stemming from widespread failures in financial regulation (Scanni MSG, 2021), emerged as a global financial crisis triggered by the collapse of the U.S. subprime mortgage market (Moreira and Hick, 2021). It led to what was later termed the Great Recession, the most severe downturn since the Great Depression of the 1930s (Verick and Islam, 2010). From a demand-and-supply perspective, the decline in demand was the dominant factor in the Great Recession (Fazzari and Needler, 2021), a pattern consistent with previous recessions (Boushey et al., 2019). The frequent use of the Threat and History topoi in 2008 media coverage mirrors the crisis’s nature: on the one hand, as the recession was deeply rooted in economic turmoil reminiscent of past events (Scanni MSG, 2021), journalists and economists, drawing on indicators like unemployment rates, could anticipate looming challenges and dangers for the economy and public; on the other, they heavily relied on historical lessons when reporting and proposing mitigation strategies. Indeed, as the 2008 crisis unfolded, it became ‘fashionable for reporters to look at earlier crises to depict where we were—and where we were likely to go’ (Schiffrin, 2011, p. 23).

In contrast, the 2020 crisis, caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, represents a global health emergency that precipitated an unprecedented economic decline. Since February 2020, when the World Health Organization (WHO) designated the pandemic as COVID-19, emergency measures implemented by policymakers in the U.S. and worldwide have significantly impacted unemployment (Dreger and Gros, 2021). Unlike the Great Depression, the pandemic altered both the aggregate supply and demand curves of the economy: on the supply side, infections and lockdowns reduced labor supply and productivity, while on the demand side, layoffs and income losses diminished household consumption and firm investment (Dreger and Gros, 2021). In short, the pandemic-induced recession constitutes a dramatic economic crisis with historically unique characteristics (Fazzari and Needler, 2021). ‘The change in economic activity has been larger and more abrupt than anything anyone has ever experienced on a global basis’ (Furman, 2020, p. 191). Consequently, the media faced challenges in predicting outcomes due to the lack of relevant historical precedents, which justifies the lower frequency of ‘Threat’ and ‘History’ in the 2020 corpus.

Furthermore, although both recessions caused mass layoffs, the differing use of topoi suggests that, in the media’s view, unemployment dynamics varied across the crises, as evidenced by the higher ranking of the Urgency topos in 2020. The 2008 crisis, which lasted approximately two years (Scanni MSG, 2021), featured a relatively gradual decline in employment followed by a slow recovery, in contrast to the COVID-19 pandemic (Fazzari and Needler, 2021). However, unemployment in 2020 stood out due to the crisis’s speed and scale (Moreira and Hick, 2021). Following the implementation of containment and mitigation measures, U.S. unemployment rates surged from 3.5% in February 2020 to 14.5% in April (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020), far exceeding job losses during any comparable period of the Great Recession (Fazzari and Needler, 2021). The exceptionally rapid and extensive job losses in the early stages of the COVID-19 recession, combined with risks to public health and national economies, justify the frequent use of the Urgency topos in 2020 media, which pressed governments for immediate action.

Moreover, considering the characteristics of the two recessions and their impacts on unemployment, the use of topoi reflects the varying magnitudes of policy responses, particularly regarding unemployment measures. The Burdening topos in the 2020 corpus indicate that the response to the 2020 crisis was significantly larger than that of 2008, placing considerable strain on federal and state budgets. This aligns with retrospective comparisons of social policies across the two crises. During the 2008 crisis, a range of macroeconomic policies—including monetary and financial measures, as well as fiscal stimulus packages—were introduced to prevent further economic decline, retain workers, and foster job creation (Verick and Islam, 2010). However, in terms of social welfare, beyond Unemployment Insurance and other programs addressing cyclical business fluctuations (Scanni MSG, 2021), much less effort was made to enhance income and employment protection or address the specific needs of vulnerable groups (Verick and Islam, 2010; Moreira and Hick, 2021).

In contrast, the 2020 crisis prompted dramatic shifts in government policies in the U.S. and globally, reflecting unprecedented state intervention and increased generosity in support measures (Moreira and Hick, 2021). In the U.S., a substantially stronger fiscal response (12.3% of GDP) was implemented compared to 2008 (Moreira and Hick, 2021). Unlike the more passive approach to protecting the unemployed during the Great Recession, 2020 saw a greater focus on expanding unemployment support, including cash transfers, such as those provided by the CARES Act (Scanni MSG, 2021). The primary driver for this shift is the public health nature of the crisis, distinct from the standard business cycle of 2008, where prioritizing public health took precedence (Scanni MSG, 2021). These initial fiscal responses were extraordinarily costly (Moreira and Hick, 2021), reflecting the crisis’s urgency and imposing significant debt on national and local budgets. This supports the recurrent use of the Burdening topos in the 2020 media.

A comparison of media’s roles during the two crises

While this study reveals how the use of topoi in news media aligns with the nature of crises, unemployment dynamics, and the scale of policy responses, this comparative perspective also highlights the distinct roles news media played during the two crises. It is widely acknowledged that media, by raising critical questions and keeping them in the public eye (Schiffrin, 2015), shape public perceptions of policy issues, which in turn influence government decision-making (Norris, 2009). During crises, news coverage disseminates information on economic conditions, public health, and policy measures, communicating risks and shaping public perceptions through the volume, content, and tone of reporting (Mach et al., 2021). Although it is challenging to quantify the direct impact of news media on the evolution of crises and unemployment, there is little doubt that, by drawing public attention and influencing government decisions, they have likely contributed to shaping the trajectories of crises and unemployment.

To begin with, media coverage of unemployment differed markedly between the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, reflecting distinct responses to the nature and urgency of each crisis. The U.S. media have rightly been criticized for failing to adequately cover the 2008 crisis (Stiglitz, 2014), which was attributed to a variety of factors, including time pressure and a lack of technical knowledge (Schiffrin, 2011). There was even less attention to unemployment and the unemployed, as the media’s focus was on the financial system’s collapse rather than the stories of the common man (Fraser, 2009). In contrast, media coverage in 2020 was significantly more intense, with the volume of unemployment-related articles 2.2 times higher than in 2008 (Figure 1). A pronounced surge in reporting during the early pandemic period (March–June 2020) closely aligned with peak unemployment rates (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020), underscoring the media’s swift response to the crisis’s urgent conditions. Moreover, the rapidly evolving COVID-19 pandemic generated extensive coverage of diverse issues, including health data, public health messages, and mitigation strategies, with the financial impact of COVID-19 emerging as the dominant theme (Basch et al., 2020).

Moreover, media strategies likely shaped policy responses and the trajectories of the two crises and unemployment in distinct ways. In 2008, the prevalent use of Threat and History topoi, which focused on forecasting risks and drawing historical comparisons, failed to garner sufficient attention from economists and policymakers (Verick and Islam, 2010, p. 3). Several factors contributed to this shortfall. First, the complexity of economic issues, such as the opaque nature of subprime mortgage derivatives, hindered the ability to make accurate predictions and obtain actionable insights (Stiglitz, 2011, p. 235). Second, while Threat and History topoi aimed to warn and contextualize, they were often superficial due to journalists’ reliance on corporate sources and lack of technical expertise (Schiffrin, 2011, p. 24). For example, 45.6% of the 125 cases of Threat topoi in the 2008 sampled corpus expressed vague warnings about unemployment or the economy, such as ‘That job loss would be double the total this year and could push the nation’s unemployment rate past 9% if nothing is done.’(NYT, 21 December, 2008). Schiffrin (2011) further notes that journalists’ fear of undermining market confidence led to cautious phrasing, limiting the depth of crisis coverage (p. 14). These factors contributed to criticisms that the press failed to anticipate the 2008 financial crisis or propose viable solutions to stimulate economic recovery and job creation (Starkman, 2014, p. 19).

By contrast, in 2020, news media played a more proactive role in shaping public perceptions through increased coverage volume and the use of argumentation strategies. The frequent use of Urgency and Burdening schemes highlighted the immediate challenges facing individuals and unemployment systems, underscored the economic pressures on governments, and emphasized the need for swift and effective measures. Significant social and stimulus policies, such as the CARES Act enacted on March 6, 2020, played a crucial role in stabilizing the labor market amid recurring pandemic waves, while mitigating the negative impact of job losses on gross domestic product (GDP). The decisiveness and agility of short-term responses to COVID-19 were notable (Moreira and Hick, 2021), contributing to a relatively rapid recovery. The U.S. economy, which contracted by approximately 32% in the second quarter of 2020, rebounded in the third quarter, achieving a 4.0% increase in GDP by year-end (Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2021). Concurrently, the unemployment rate steadily declined, reaching 6.7% by the end of 2020 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020).

Conclusion

Through a quantitative analysis of topoi in unemployment discourse, this study examines and compares media representations of unemployment in the U.S. during two major crises. It identifies both commonalities and divergences in the use of topoi, shedding light on the argumentative strategies employed in news coverage related to unemployment. Methodologically, the study advances the understanding of media representations of unemployment in several key ways. While topos theory has primarily been applied to immigration and political discourse, this study’s corpus-based, quantitative analysis of topoi in unemployment-related news articles introduces a novel approach to exploring dominant argumentation strategies in this domain. Additionally, the comparative perspective provides fresh insights into how media interpret the nature of crises, the characteristics of unemployment, and policy responses across the two periods.

This study also has significant practical implications for the media’s role in crisis management. Comparing the effects of media coverage of unemployment in the two crises highlights the media’s capacity not only to inform but also to influence policy responses and drive action during times of crisis. Moreover, it underscores the urgent need for timely government responses during mass layoffs, including substantial support for the unemployed and efforts to foster economic recovery.

Despite its contributions, the study has certain limitations. First, by focusing on unemployment-related sentences rather than the entire news articles, it may not fully capture the complexity of media representations of unemployment. Second, although topos theory typically analyzes entire discourses (Wodak, 2001, 2009), this study adopts a more localized approach, examining argumentation strategies by linking unemployment-related sentences to the claims within specific passages. To address the limitations of this localized analysis, we incorporated a corpus-based method to enhance the precision of topoi identification. Future research could expand the scope of analysis to entire news articles, providing a more comprehensive understanding of unemployment discourse.

In conclusion, this study significantly enhances our understanding of media representations of unemployment. It examines the relationship between topoi and the characteristics of unemployment during various crises, highlighting the media’s crucial role in shaping public discourse and policy responses. While acknowledging its limitations, the study opens new avenues for future research to build on its findings, further illuminating the complex interplay between media, unemployment, and policy responses during times of crisis.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Author contributions

LYa: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LYu: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2025.1581167/full#supplementary-material

References

Alizadeh, H., Sharifi, A., Damanbagh, S., Nazarnia, H., and Nazarnia, M. (2023). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the social sphere and lessons for crisis management: a literature review. Nat. Hazards 117, 2139–2164. doi: 10.1007/s11069-023-05959-2

Barbieri Góes, M. C., and Gallo, E. (2021). Infection is the cycle: unemployment, output and economic policies in the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev. Polit. Econ. 33, 377–393. doi: 10.1080/09538259.2020.1861817

Basch, C. H., Kecojevic, A., and Wagner, V. H. (2020). Coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic in the online versions of highly circulated US daily newspapers. J. Community Health 45, 1089–1097. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00913

Blustein, D. L., Kozan, S., and Connors-Kellgren, A. (2013). Unemployment and underemployment: a narrative analysis about loss. J. Vocat. Behav. 82, 256–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2013.02.005

Boushey, H., Nunn, R., and Shambaugh, J. (2019). Recession ready: Fiscal policies to stabilize the American economy. Washington, DC: Brookings.

Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2021) Gross domestic product, 4th quarter and year 2020 (advance estimate). Available online at: https://www.bea.gov/news/2021/grossdomestic-product-4th-quarter-and-year-2020-advance-estimate (Accessed April 16, 2024).

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2008) Unemployment rate [UNRATE]. Available online at: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE (Accessed March 20, 2024).

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020) Unemployment rises in 2020, as the country battles the COVID-19 pandemic Unemployment rate. Available online at: https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2021/article/pdf/unemployment-rises-in-2020-as-the-country-battles-the-covid-19-pandemic.pdf (Accessed June 9, 2025).

Carter, S. M. (2021). The construction of value in science research articles: a quantitative study of topoi used in introductions. Written Commun. 38, 311–346. doi: 10.1177/0741088320983364

Damstra, A., Boukes, M., and Vliegenthard, R. (2018). The economy: how do the media cover it, and what are its effects? A literature review. Sociol. Compass 12, 1–14. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12579

Dreger, C., and Gros, D. (2021). Lockdowns and the US unemployment crisis. Econ. Disasters Climate Change 5, 449–463. doi: 10.1007/s41885-021-00092-5

Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. London: Routledge.

Fazzari, S. (2020). “24 FMM Conference: Session 4: Into Sharp Relief – Corona and Inequality.” YouTube video, Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, 6 Nov. 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=uTG8f2ltJPM.

Fazzari, S. M., and Needler, E. (2021). US employment inequality in the great recession and the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Econ. Econ. Policies 18, 223–239. doi: 10.4337/ejeep.2021.02.09

Fraser, M. (2009). Five reasons for crash blindness. Br. Journalism Rev. 20:78. doi: 10.1177/0956474809356852

Furman, J. (2020). The crisis opportunity: what it will take to build back a better economy. Foreign Aff. 100:25.

Gannett (2020). Press room: press kit. USA Today. Available online at: https://marketing.usatoday.com/about (Accessed May 22, 2025).

Gape, A. (2023) A breakdown of the fiscal and monetary responses to the pandemic. Available online at: https://www.investopedia.com/government-stimulus-efforts-to-fight-thecovid-19-crisis-4799723 (Accessed April 20, 2024).

Gourinchas, P. O. (2020). Flattening the pandemic and recession curves. Mitigating the COVID economic crisis: act fast and do whatever. NYU 31, 57–62.

Hicks, D., and Wang, J. (2013). The New York times as a resource for mode 2. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 38, 851–877. doi: 10.1177/0162243913497806

Kienpointner, M. (1992). Alltagslogik. Struktur und Funktion von Argumentationsmustern. Pennsylvania: Frommann-Holzboog.

Liang, M. C., Li, W. Z., and Xu, J. J. (2010). Using corpora: A practical coursework. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

Mach, K. J., Salas Reyes, R., Pentz, B., Taylor, J., Costa, C. A., Cruz, S. G., et al. (2021). News media coverage of COVID-19 public health and policy information. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 8. doi: 10.1057/s41599-021-00900-z

McArthur, D., and Reeves, A. (2019). The rhetoric of recessions: how British newspapers talk about the poor when unemployment rises, 1896–2000. Sociology 53, 1005–1025. doi: 10.1177/0038038519838752

Moreira, A., and Hick, R. (2021). COVID-19, the great recession and social policy: is this time different? Soc. Pol. Admin. 55, 261–279. doi: 10.1111/spol.12679

Muntigl, P. (2002). Policy, politics, and social control: a systemic functional linguistic analysis of EU employment policy. Text Talk 22, 393–441. doi: 10.1515/text.2002.016

Nicola, M., Alsafi, Z., Sohrabi, C., Kerwan, A., Al-Jabir, A., Iosifidis, C., et al. (2020). The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int. J. Surg. 78, 185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018

Norris, P. (2009). Public sentinel: News media and governance reform. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Publications.

Okoroji, C., Gleibs, I. H., and Jovchelovitch, S. (2021). Elite stigmatization of the unemployed: the association between framing and public attitudes. Br. J. Psychol. 112, 207–229. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12450

Papadopoulos, A., and O’Keeffe, P. (2024). Automating activation in Australia: a critical policy discourse analysis of the new employment services model. Crit. Policy Stud. 18, 131–149. doi: 10.1080/19460171.2023.2207618

Pengue, M. (2023) 25 insightful New York Times readership statistics, the 2023. Available online at: https://letter.ly/new-york-times-readership-statistics/ (Accessed May 22, 2025).

Reft, R. (2022) USA today at 40. Unfolding history: library of congress. Available online at: https://blogs.loc.gov/manuscripts/2022/09/usa-today-at-40/ (Accessed May 22, 2025).

Reisigl, M. (2014). “Argumentation analysis and the discourse-historical approach: a methodological framework” in Contemporary critical discourse studies. eds. C. Hart and P. Cap (London: Bloomsbury), 67–96.

Reisigl, M., and Wodak, R. (2005). Discourse and discrimination: Rhetorics of racism and antisemitism. London: Routledge.

Reisigl, M., and Wodak, R. (2016). “The discourse-historical approach (DHA)” in Methods of critical discourse studies. eds. R. Wodak and M. Meyer. 3rd ed (London: Sage), 23–61.

Rice, J. S., and Bond, A. M. (2013). The great recession and free market capitalist hegemony: a critical discourse analysis of U.S. newspaper coverage of the economy, 2008–2010. Sociol. Focus 46, 211–228. doi: 10.1080/00380237.2013.798227

Richardson, J. E., and Wodak, R. (2009). The impact of visual racism: visual arguments in political leaflets of Austrian and British far-right parties. Controversia 6, 45–77.

Ross, D. G. (2012). Common topics and commonplaces of environmental rhetoric. Written Commun. 30, 91–131. doi: 10.1177/0741088312465376

Scanni MSG (2021). The Great Recession vs The Covid-19 Pandemic: unemployment and implications for public policy. Theses-Graduate Programs in Economic Theory and Policy 33. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/levy_ms/33 (Accessed March 19, 2024).

Schiffrin, A. (2011). Bad news: How America’s business press missed the story of the century. New York City: New Press.

Schiffrin, D. (2015). Approaches to discourse: Language as social interaction. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell.

Simonsen, S. (2024). Discursive blame attribution strategies in migration news frames: how blame for perceived migration-related problems is mediated in journalistic framing. Discourse Context Media 58:100772. doi: 10.1016/j.dcm.2024.100772

Stanca, I., and Tarbujaru, T. (2022). Crisis management: what COVID-19 taught the world. Logos Univ. Mentality Educ. Novelty Econ. Adm. Sci. 7, 01–18. doi: 10.18662/lumeneas/7.1/32

Starkman, D. (2014). The watchdog that didn’t bark: The financial crisis and the disappearance of investigative journalism. Columbia University Press.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2011). Rethinking development economics. The World Bank Research Observer, 26, 230–236.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2014). “The media and the crisis: an information theoretic approach” in The media and financial crises. eds. S. Schifferes, R. Roberts, S. Schifferes, and R. Roberts (New York: Routledge), 168–180.

Suran, M. (2023). Long COVID linked with unemployment in new analysis. JAMA 329, 701–702. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.0157

Van Leeuwen, T. (1999). “Discourses of unemployment in new labor Britain” in Challenges in a changing world:Issues in critical discourse analysis. eds. R. Wodak and C. Ludwig (Vienna: Passagen Verlag), 87–100.

Verick, S., and Islam, I. (2010) The great recession of 2008-2009: causes, consequences and policy responses. IZA Discussion Paper No. 4934. IZA Discussion Papers.

Weible, C. M., Nohrstedt, D., Cairney, P., Carter, D. P., Crow, D. A., Durnová, A. P., et al. (2020). COVID-19 and the policy sciences: initial reactions and perspectives. Policy. Sci. 53, 225–241. doi: 10.1007/s11077-020-09381-4

Weiss, G., and Wodak, R. (2000). European Union discourses on employment: strategies of depoliticizing unemployment and ideologizing employment policies. Concepts Transform. 5, 29–42. doi: 10.1075/cat.5.1.05wei

WHO (2021) Overview. Available online at: https://covid19.who.int/ (Accessed 20 May 2024).

Wodak, R. (2001). “The discourse-historical approach (DHA)” in Methods of critical discourse studies. eds. R. Wodak and M. Reisigl. 1st ed (Cham: Sage), 63–94.

Wodak, R., and Leeuwen, T. V. (2002). Discourses of un/employment in Europe: the Austrian case. Text Talk 22, 345–367. doi: 10.1515/text.2002.014

Yu, H., Lu, H., and Hu, J. (2021). A corpus-based critical discourse analysis of news reports on the COVID-19 pandemic in China and the UK. Int. J. Engl. Linguist. 11, 36–45. doi: 10.5539/ijel.v11n2p36

Keywords: unemployment, discursive comparison, topoi, media, crisis

Citation: Yang L and Yu L (2025) Media’s role in the crisis: a discursive comparison of U.S. media representations of unemployment in 2008 and 2020. Front. Commun. 10:1581167. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1581167

Edited by:

Adilson Vaz Cabral Filho, Fluminense Federal University, BrazilReviewed by:

Michalis Tastsoglou, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, GreeceÁlvaro López-Martín, University of Malaga, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Yang and Yu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lingli Yu, eXVsaW5nbGlAbmJ1LmVkdS5jbg==

Ling Yang

Ling Yang Lingli Yu

Lingli Yu