- Faculty of Informatics, Kansai University, Takatsuki, Osaka, Japan

In today’s hyperconnected digital landscape, brands cultivate a sense of community among consumers to enhance engagement and loyalty. While such efforts can foster positive brand relationships, they may also lead to unintended negative consequences. This study examines how a strong sense of community among brand consumers can contribute to hostile behaviors, specifically trash talk against rival brands. Drawing on social identity theory, we hypothesize that a sense of community fosters trash talk, mediated by inter-brand and inter-consumer rivalry. A survey of Japanese consumers (N = 310) reveals that while inter-brand rivalry does not significantly drive trash talk, inter-consumer rivalry plays a critical role. Consumers with a sense of community are likely to develop inter-consumer rivalry, which in turn amplifies trash talk. Moreover, a sequential mediation effect is identified, where a sense of community heightens inter-brand rivalry, which subsequently fuels inter-consumer rivalry, leading to trash talk. These findings underscore the risks associated with fostering a sense of community in brand management. While strengthening consumer connections can enhance loyalty, it may also intensify competitive hostility, potentially harming brand equity. This study expands existing research by highlighting the dual nature of a sense of community and its implications for brand strategy.

1 Introduction

In today’s digital marketplace, consumer connections play a crucial role in shaping brand loyalty and engagement. Social media enables consumers to easily interact with others who share their brand preferences, strengthening their attachment to brands and fostering community dynamics (Cova, 1997; Kohls et al., 2023; Marchowska-Raza and Rowley, 2024; Muniz and O’Guinn, 2001). The bonds between consumers have transcended the boundaries of traditional brand communities and are now being formed in a broader communicative space (Arnould et al., 2021; Arvidsson and Caliandro, 2016). This study conceptualizes these connections as a sense of community (Carlson et al., 2008).

While a sense of community has been verified to contribute positively to consumers’ brand loyalty, commitment, and word-of-mouth intentions (Carlson et al., 2008; Lyu and Kim-Vick, 2022), its potential negative effects remain largely unexplored. A strong sense of community can promote hostile behaviors toward rival brands, commonly referred to as trash talk. Trash talk involves derogatory comments aimed at rival brands, often used by consumers as a means of emphasizing their loyalty to their own brand (Hickman and Ward, 2007).

For example, Apple and Samsung have long been at the center of intense brand rivalries, fueled not only by their technological competition but also by their marketing strategies and consumer communities (Ilhan et al., 2018). Apple’s branding often positions its products as part of an exclusive and innovative ecosystem, implicitly setting itself apart from competitors like Samsung. Meanwhile, Samsung frequently engages in comparative advertising that directly critiques Apple, reinforcing the perception of rivalry among consumers. As a result, loyal Apple users often express their brand preference through negative comments about Samsung devices on social media, illustrating how a strong sense of community can sometimes manifest in trash talk. While such rivalry and trash talk can enhance brand engagement, it also poses risks, as excessive negativity can alienate potential consumers and damage brand reputation (Ewing et al., 2013; Fisk et al., 2010; Laroche et al., 2012; Lee, 2005; Wang et al., 2012).

As consumer advocacy and brand interactions increasingly take place in digital spaces, understanding trash talk is crucial for maintaining brand reputation and consumer trust. This study examines how a sense of community fosters trash talk through inter-brand and inter-consumer rivalries. Drawing on social identity theory (Turner et al., 1979), which explains how group membership shapes individual self-perception, we examine the mechanisms that lead to hostile brand-related behaviors.

To address this research purpose, we pose the following specific research questions. First, how does a sense of community contribute to the emergence of trash talk? Second, what roles do inter-brand rivalry and inter-consumer rivalry play in mediating the relationship between a sense of community and trash talk?

This study makes several contributions to the literature. First, it extends a sense of community research by exploring the potential negative outcomes. This extension provides a more nuanced understanding of the double-edged nature of consumer-to-consumer relationships. Second, it introduces and empirically tests a model that explains the process by which a sense of community leads to trash talk, mediated by different forms of rivalry. This model offers a novel perspective on the dynamics of inter-brand competition and its impact on consumer behavior.

This paper is structured as follows. First, it reviews relevant prior research on a sense of community, social identity theory, and trash talk. Next, it presents the theoretical framework and develops hypotheses. The research methodology is then detailed, followed by a report of the analysis results. Finally, theoretical and practical implications are discussed, and the limitations of this study and directions for future research are presented.

2 Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1 Sense of community

The concept of a sense of community, which originated in community psychology, has gained significant traction in consumer behavior and marketing research. Carlson et al. (2008, p. 286) defines it as “the degree to which an individual perceives relational bonds with other brand users.” Unlike traditional brand communities, this concept can exist without formal membership or direct interaction, whether real or online (Bergkvist and Bech-Larsen, 2010; Carlson et al., 2008; Kohls et al., 2023; Sjöblom and Hamari, 2017).

The rise of social media has dramatically transformed how consumers connect with others who share their brand preferences, regardless of how niche those preferences might be. Particularly, features like hashtags enable consumers to easily discover and connect with others who share their interests in specific brands, products, or topics (Arvidsson and Caliandro, 2016). This functionality has lowered the barriers for forming consumer networks, as individuals can join conversations and find like-minded consumers simply by following or using relevant hashtags. In this hyperconnected environment, consumers can interact and engage with one another across diverse settings, leading to both strengthened brand preferences and the discovery of new brand values (Cova, 1997; Muñiz and Schau, 2005; Swaminathan et al., 2020). These consumer-to-consumer relationships collectively form what we understand as a sense of community.

Furthermore, research has empirically demonstrated that this sense of community serves as a fundamental driver of consumer behavior in the digital age. Specifically, it enhances various aspects of brand relationships. Consumers with a stronger sense of community exhibit greater brand loyalty, actively engage in positive word-of-mouth communication, and demonstrate stronger brand advocacy (Bauer, 2022; Carlson et al., 2008; Lyu and Kim-Vick, 2022). The significance of these effects is particularly pronounced in today’s hyperconnected society, where consumer interactions and influence extend far beyond traditional geographical and social boundaries.

When examining a sense of community, it is essential to distinguish it from related concepts, particularly identification with the brand community. While both concepts focus on consumer-to-consumer relationships, there is a fundamental difference between them (Bergkvist and Bech-Larsen, 2010). Identification with the brand community, a core concept in brand community studies, measures the perceived similarity between community members and their community (Algesheimer et al., 2005; Demiray and Burnaz, 2019). This identification requires conscious awareness of and affiliation with the community. In contrast, a sense of community can develop without formal community membership. This distinction is crucial as it allows the concept to describe not only the specific relationships within brand communities but also the broader, looser consumer-to-consumer connections that form in other contexts, such as brand publics (Arvidsson and Caliandro, 2016).

2.2 Social identity theory

Consumers with a sense of community develop an awareness of “in-group” and “out-group,” a concept central to social identity theory. Social identity theory, which emerged within social psychology to explain in-group bias and out-group bias in intergroup dynamics, has become increasingly relevant in understanding the relationship between a sense of community and brand relationships (Carlson et al., 2008; Rosenbaum et al., 2005). This theoretical framework, now widely applied in consumer behavior research, provides valuable insights into how consumers form and maintain brand relationships. This section outlines the fundamental elements of social identity theory and its application to brand relationships.

At its core, social identity theory posits that individuals construct their self-concept through a combination of personal identity (individual traits and capabilities) and social identity (characteristics derived from affiliated social groups) (Hogg and Abrams, 1988; Turner, 1984). When individuals categorize themselves as members of a particular group (their “in-group”) distinct from other groups (“out-groups”), they typically demonstrate favorable (unfavorable) bias toward their in-group (out-groups) (Ferguson and Kelley, 1964; Tajfel et al., 1971). This preferential evaluation serves to enhance self-esteem through positive in-group association (Hogg and Abrams, 1988). Thus, social identification theory effectively explains the mechanisms underlying intergroup discrimination (Tajfel and Turner, 2000).

Social identity theory has proven particularly valuable in brand community research, where consumer collectives are examined. Following Algesheimer et al.'s (2005) introduction of brand community identification, numerous studies have empirically validated that stronger identification with the brand community enhances both community and brand relationships (Chang et al., 2019; Mandl and Hogreve, 2020; Zhou et al., 2012). Building on this research stream, scholars have increasingly focused on the broader concept of a sense of community, with empirical studies confirming that developing a sense of community among consumers strengthens brand relationships (Carlson et al., 2008; Rosenbaum et al., 2005; Swimberghe et al., 2018). In the context of brand consumption, this sense of community leads consumers to recognize clear boundaries that distinguish between users of the brand and non-users. This boundary recognition inherently creates group biases that would not emerge without such a sense of community.

The extensive body of research demonstrates that fostering a sense of community has become a crucial strategy for enterprises seeking to enhance brand relationships in today’s market environment. However, this phenomenon requires careful consideration of its potential drawbacks. While cultivating a sense of community generates beneficial in-group bias, it simultaneously creates negative biases toward out-groups, particularly rival brands. These negative biases can manifest as oppositional behaviors toward rival brands, which existing research has not thoroughly explored. This suggests an important direction for investigation, particularly in understanding how group biases generated by a sense of community lead to oppositional brand behaviors.

2.3 Trash talk

In the field of consumer behavior research, oppositional brand loyalty—which focuses on negative actions and attitudes toward rival brands—is attracting considerable attention. First introduced by Muniz and Hamer (2001), oppositional brand loyalty describes hostile behaviors directed at rival brands of a preferred brand. This concept is distinct from brand hate, which denotes a profound negative sentiment toward a specific brand. While brand hate exclusively focuses on intense negative sentiments toward a particular brand, oppositional brand loyalty is fundamentally rooted in both the robust endorsement of a specific brand and the presence of rival brands (Attiq et al., 2023; Japutra et al., 2014; Liao et al., 2021; Zarantonello et al., 2016).

Oppositional brand loyalty manifests through various behaviors, including the avoidance and rejection of rival brands, schadenfreude, negative word-of-mouth, and trash talk, which have been used as proxy variables in research. Among these manifestations, this study specifically focuses on trash talk—the active insult or denigration of rival brands (Hickman and Ward, 2007; Liao et al., 2023). Two key reasons justify this focus. First, given the growing influence of word-of-mouth on social media (Keller and Fay, 2018), trash talk has become increasingly significant. It can provoke reactions from fans of rival brands, potentially leading to new conflicts and damaging the user image of the favored brand.

Second, while trash talk is observed in various contexts, it remains understudied in consumer behavior research. Originally a concept from sports research, trash talk was introduced to consumer behavior studies by Hickman and Ward (2007), particularly within brand community research. Subsequently, Japutra et al. (2018) revealed that trash talk occurs independently of community participation and is reinforced by strong brand relationships. The relative novelty of trash talk in consumer behavior research, coupled with limited existing studies, indicates a significant need for further investigation.

Given this focus on trash talk, it is crucial to distinguish it from negative word-of-mouth, as they represent distinct concepts. Hickman and Ward (2007) and Marticotte et al. (2016) highlight key distinctions between negative word-of-mouth and trash talk. Negative word-of-mouth arises from specific experiences, such as dissatisfaction, whereas trash talk does not require such an experiential basis. Furthermore, trash talk simultaneously involves rejecting rival brands while endorsing a favored brand, a dual dynamic absent in negative word-of-mouth. Consequently, trash talk represents a more intense and active behavior compared to negative word-of-mouth (Liao et al., 2023).

2.4 Social identity theory and trash talk

Understanding the antecedents of trash talk is essential for both theoretical development and practical brand management. By clarifying the factors that drive consumers to engage in trash talk, brand managers can better prevent potential brand damage stemming from conflicts between brand users, while simultaneously advancing the theoretical understanding of brand relationship dynamics. Prior research has explored various antecedents of trash talk, often focusing on consumers’ relationships with their preferred brand and its users (Hickman and Ward, 2007; Japutra et al., 2018, 2022). However, the findings have been inconsistent regarding the mechanisms that drive trash talk behavior.

Hickman and Ward (2007), in their study of brand community participants, found that stronger identification with the brand community enhances in-group/out-group biases, which, in turn, promotes trash talk. Their findings suggest that trash talk is more likely to emerge when consumers strongly value the brand or feel emotional warmth toward fellow consumers. Similarly, Marticotte et al. (2016) examined the role of brand community identification, brand loyalty, and self-brand connection in trash talk behavior. Their study revealed that brand community identification had no significant effect on trash talk, which they attributed to the cognitive rather than emotional nature of interactions in specific contexts like video game communities.

In contrast, Japutra et al. (2022) highlighted the role of emotional attachment, particularly brand attachment, in driving behaviors such as impulse buying, which in turn promotes trash talk. However, recent studies have challenged these findings. Junaid et al. (2022) argued that brand love has minimal impact on trash talk, suggesting that while brand love increases support for the brand, it may suppress negative opinions toward rival brands. Liao et al. (2023) further noted that brand identification often leads to passive behaviors, such as avoiding rival brands, rather than active behaviors like trash talk. They suggested that disidentification with rival brands might be a stronger predictor of trash talk than brand identification.

These inconsistencies highlight the need to explore new dimensions of consumer relationships that could explain trash talk more comprehensively. Notably, while prior studies focused on brand identification, there has been limited attention on the broader sense of community that can exist without formal membership. A sense of community refers to the perceived bond among individuals who feel they belong to a group, which can foster in-group/out-group dynamics (Tajfel, 1984). This study seeks to address this gap by investigating how a sense of community, distinct from formal brand communities, drives trash talk through group biases.

When consumers develop a strong sense of community, they perceive themselves as part of a distinct social group, which increases their loyalty and connection to that group (Mamonov et al., 2016; Swimberghe et al., 2018). This enhanced group identity leads to the recognition of boundaries between the in-group (users of their preferred brand) and out-group (users of rival brands). Social identity theory posits that such group distinctions intensify in-group favoritism and out-group hostility, which can manifest as negative behaviors toward out-group members, such as trash talk (Tajfel, 1984).

H1: A sense of community positively affects trash talk.

2.5 Inter-brand rivalry and inter-consumer rivalry

While it is possible to directly link a sense of community with trash talk, introducing mediating variables can facilitate a more precise understanding of the mechanism through which trash talk emerges. This study focuses on brand rivalry as a potential mediating variable. Although rivalry has been discussed as a motive for hostile behavior (Muniz and Hamer, 2001), its relationship with trash talk, particularly in the context of a sense of community, requires further investigation. The widespread observation of rivalry in social media environments, characterized by anonymity and ease of communication (Ewing et al., 2013), underscores the importance of examining this mechanism.

Research has shown that consumers engage in hostile behavior when rival brands threaten their preferred brands (Ewing et al., 2013; Marticotte et al., 2016; Muniz and Hamer, 2001). This phenomenon is particularly evident in markets with clear rivalries, such as Coca-Cola versus Pepsi or Ford versus Holden (Ewing et al., 2013; Muniz and Hamer, 2001). Interestingly, Hickman and Ward (2007) found that when consumers evaluate their in-group significantly higher than the out-group, they are less likely to perceive others as rivals, reducing the likelihood of trash talk. Furthermore, consumers who perceive strong rivalry exhibit an increased desire to protect their preferred brands, strengthening the relationship between brand identification and oppositional brand loyalty (Liao et al., 2021). This connection is further supported by evidence that disidentification with rival brands directly influences trash talk behavior (Liao et al., 2023). These findings show that rivalry toward rival brands is a key factor in deepening our understanding of hostile behaviors such as trash talk.

A sense of community is expected to enhance rivalry through several psychological mechanisms. Consumers with a strong sense of community maintain clear boundaries between in-groups and out-groups. Through social comparison processes (Festinger, 1954; Turner et al., 1979), they actively define their in-group identity by contrasting it with out-groups, which intensifies rivalry. Additionally, as in-group connections strengthen, competition with out-groups naturally emerges (Ashforth and Mael, 1989; Carron and Brawley, 2000), often manifesting as hostile behaviors such as trash talk (Mullen and Copper, 1994).

Rivalry is inherently bidirectional, not unidirectional (Berendt et al., 2018; Osuna Ramírez et al., 2024). Unlike concepts such as brand hate, which represent unidirectional rejection of specific brands (Attiq et al., 2023), rivalry requires the presence of both supporting and opposing brands. This rivalry can be categorized into two distinct but related forms, inter-brand rivalry and inter-consumer rivalry (Berendt et al., 2018; Hickman and Ward, 2007). Inter-brand rivalry occurs between brands themselves, while inter-consumer rivalry develops among users of competing brands.

The relationship between these two forms of rivalry is sequential. Berendt et al. (2018) demonstrated that increased inter-brand rivalry leads consumers to become more aware of brand competition, which subsequently promotes inter-consumer rivalry. This suggests a spillover effect where brand-level competition catalyzes competitive behavior among consumers. Based on this discussion, it can be inferred that inter-brand rivalry develops first, subsequently leading to an increase in inter-consumer rivalry. This sequential relationship suggests that the impact of a sense of community on trash talk may follow two distinct but interconnected paths, one through inter-brand rivalry and another through inter-consumer rivalry.

A strong sense of community reinforces consumer rivalry in multiple way. First, through social comparison processes, they develop inter-brand rivalry by clearly distinguishing their preferred brands from competing ones. This rivalry can directly lead to trash talk as a means of asserting brand superiority. Second, as community members interact with each other, they develop inter-consumer rivalry, which can also trigger trash talk as a form of collective opposition against rival brand users. Moreover, these two forms of rivalry are interconnected. The awareness of inter-brand competition often spills over into consumer-level interactions, creating a cascade effect where brand-level rivalry intensifies consumer-level rivalry and subsequent trash talk behavior.

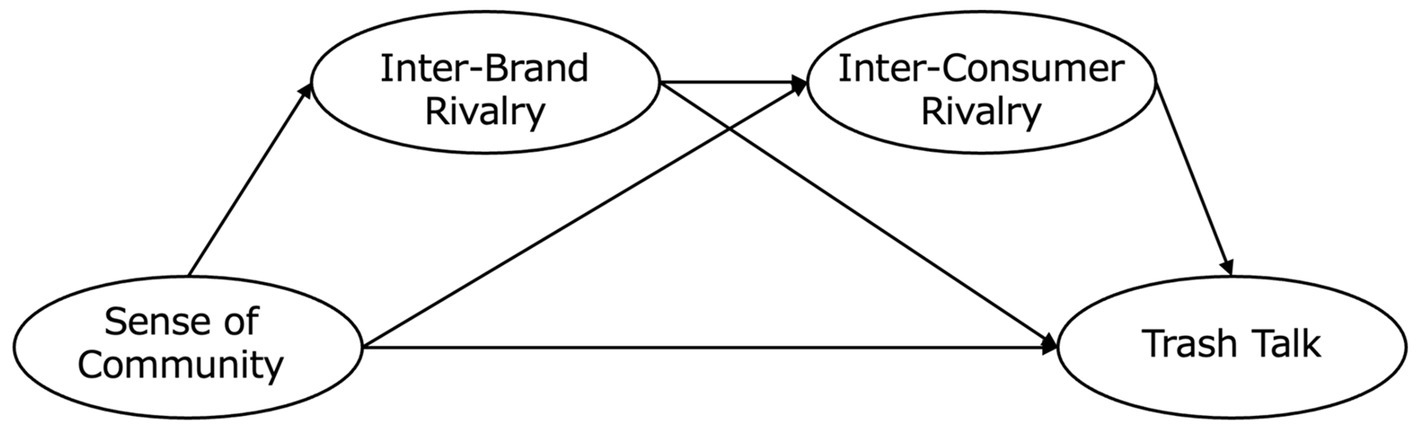

While rivalry serves as a key mediating mechanism, the relationship between a sense of community and trash talk is likely more complex than simple full mediation. A sense of community can also directly influence trash talk through other mechanisms, such as the need to maintain group distinctiveness or demonstrate group loyalty, independent of rivalry (Hickman and Ward, 2007). Furthermore, consumers may engage in trash talk as a manifestation of strengthened brand relationships developed through a sense of community. These direct effects, combined with the parallel pathways through both brand-focused and consumer-focused rivalry (Liao et al., 2021), suggest a partial mediation model. These relationships are illustrated in Figure 1, leading to the following hypotheses.

H2: Inter-brand rivalry mediates the effects of a sense of community on trash talk.

H3: Inter-consumer rivalry mediates the effects of a sense of community on trash talk.

H4: Inter-brand rivalry and inter-consumer rivalry serially mediate the relationship between a sense of community and trash talk.

3 Methodology

3.1 Data collection

A web-based survey was conducted to investigate the relationships between sense of community, inter-brand/inter-consumer rivalry, and trash talk. This study presumes that consumers have a brand they support, as the presence of rivalry necessitates brand support (Berendt et al., 2018). Therefore, participants were instructed to answer the survey questions with their favorite brand in mind. Data collection was conducted in July 2024 through a crowdsourcing service provided by iBRIDGE Corp., Japan. The initial sample consisted of 400 participants (equally divided between men and women) residing throughout Japan. To ensure balanced age representation, 80 samples were gathered from each of five age categories (20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s).

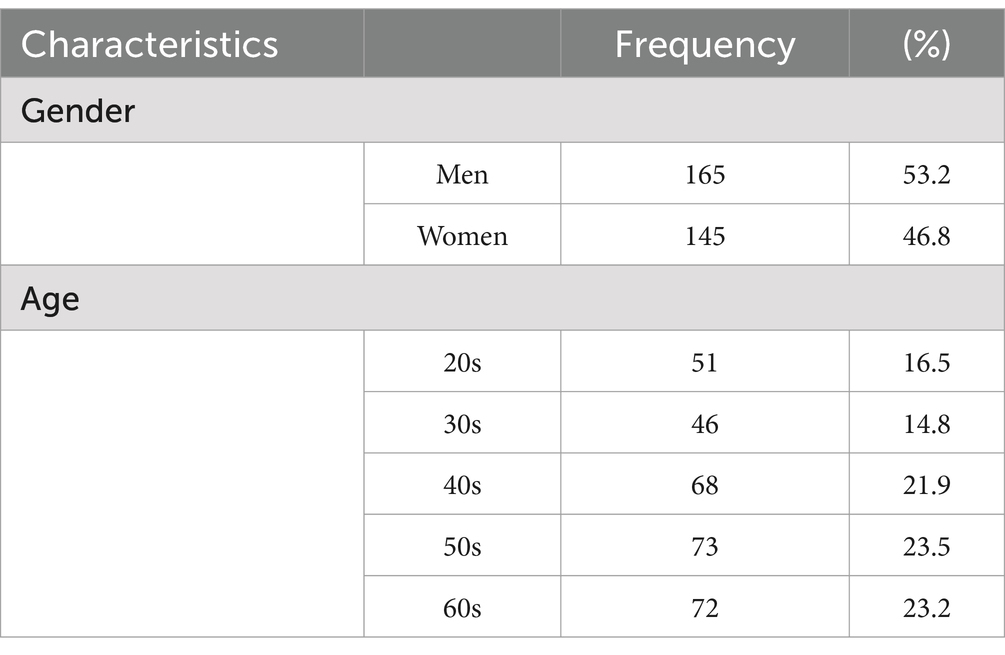

To address the common issue of participants minimizing effort in online surveys (Aust et al., 2013), we implemented two attention check questions to identify and exclude undesirable response behaviors. The first attention check question was embedded within the scale items, instructing participants to “Select neither for this question” among five response options (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”). The second attention check involved a simple numerical calculation (74–47 = ?), where participants selected from five response options (Iseki et al., 2022). Additionally, participants who indicated their favorite brand had no competitors or provided insincere responses (e.g., patterned selections) were excluded from the analysis. After these quality control measures, the final sample consisted of 310 valid responses, yielding an effective participation rate of 77.5%. The demographic details are presented in Table 1.

Analysis of the final sample revealed no significant gender bias. However, there was a slightly higher proportion of participants aged 40 and above, which may be attributed to older participants’ tendency to respond more attentively to survey items, thus being more likely to pass the attention checks.

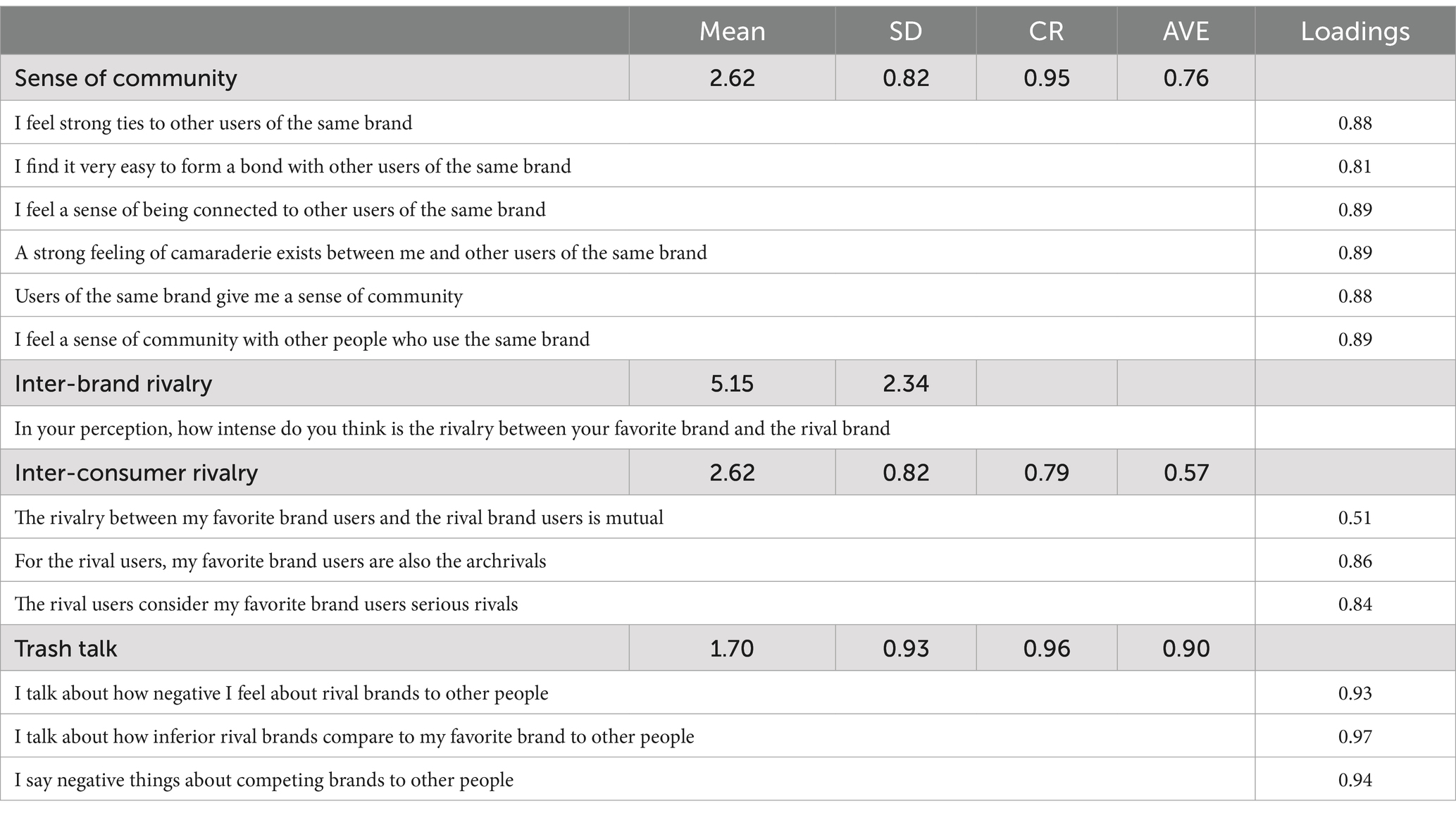

3.2 Measures

Except for inter-brand rivalry, all measures were adapted from previous studies using five-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Table 2 presents the measurement items with their factor loadings. A sense of community was measured using six items from Carlson et al. (2008). Both inter-brand and inter-consumer rivalry measures were based on Berendt et al. (2018), with inter-brand rivalry assessed through a single item (1 = not very intense to 10 = very intense) after participants identified a rival brand, while inter-consumer rivalry was measured using three items. The dependent variable, trash talk, was measured using three items adapted from Hickman and Ward (2007).

Although inter-brand rivalry was measured with a single item, research suggests that reliability can be maintained when the target construct is specific and clear (Bergkvist and Rossiter, 2007; Wanous and Hudy, 2001). Since participants can easily assess the intensity of inter-brand rivalry (Berendt et al., 2018), a single-item measure was deemed appropriate.

Since all measurement scales originated from English-language literature, we implemented a back-translation procedure (Douglas and Craig, 1983). First, we translated the items into Japanese, then a bilingual researcher translated them back to English. A native English speaker compared the original and re-translated versions to ensure semantic and nuanced equivalence. Items requiring revision underwent this process iteratively until no discrepancies remained.

3.3 Reliability and validity of the measures

To address potential common method bias due to self-reported data collected at a single time point, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The largest explained variance before rotation was 49.01% (<50%), indicating no significant common method bias.

Before testing our hypotheses, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis to evaluate measurement properties (Table 2). The model demonstrated satisfactory fit indices with χ2(51) = 74.782, CFI = 0.993, GFI = 0.962, AGFI = 0.942, and RMSEA = 0.039, all of which exceed recommended thresholds (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988). Reliability was confirmed through composite reliability (CR), with all constructs exceeding the standard threshold of 0.60 (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988).

Convergent validity was assessed through factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE) (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988; Hair et al., 2013). With one exception in the inter-consumer rivalry construct, all factor loadings exceeded 0.60. Additionally, AVE values for all constructs surpassed the standard threshold of 0.50 (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988; Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2013), confirming convergent validity. Discriminant validity was verified by comparing the square root of AVE with correlation coefficients (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2013), revealing no concerns.

4 Results

All hypotheses were tested using SPSS 29. First, linear regression was conducted to test the effect of a sense of community on trash talk (H1). The results of the linear regression analysis indicated that a sense of community significantly affected trash talk (β = 0.29, t(308) = 5.94, p < 0.001). The coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.08 (F(1,308) = 27.58, p < 0.001), indicating that a sense of community explained 8% of the variance in trash talk. Thus, H1 is supported.

To test H2 through H4, we conducted a serial mediation analysis using Hayes’ (2022) PROCESS macro (Model 6). This model allowed us to examine the indirect effect with a sense of community as the predictor variable and inter-brand rivalry and inter-consumer rivalry as the mediators, with trash talk as the outcome variable. Furthermore, since age and gender have been suggested to be related to trash talk (Ewing et al., 2013), they were included as control variables. To generate 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals and test the statistical significance of the direct and indirect effects, we applied 10,000 bootstrap resamples. We chose to use bootstrap resamples because this approach provides superior outcomes for indirect effects by effectively controlling Type I error and not assuming normality in the sampling distribution (Mackinnon et al., 2004). An effect is considered statistically significant when the bootstrap confidence intervals do not include zero (i.e., when both the upper and lower limits are either entirely above or below zero). Conversely, if the confidence interval straddles zero, the effect is not statistically significant (Hayes, 2022).

Regarding the control variables, age has a significant negative effect on inter-consumer rivalry (β = −0.10, SE = 0.00, p < 0.05) and trash talk (β = −0.14, SE = 0.00, p < 0.01), indicating that older individuals are less likely to engage in these behaviors. However, its effect on inter-brand rivalry is not significant (β = 0.02, SE = 0.01, p = 0.679). Gender (0 = women, 1 = men) has a significant positive effect on inter-consumer rivalry (β = 0.09, SE = 0.08, p < 0.05) and trash talk (β = 0.11, SE = 0.09, p < 0.05), suggesting that men are more likely to engage in these behaviors. However, its effect on inter-brand rivalry is not significant (β = 0.06, SE = 0.26, p = 0.283).

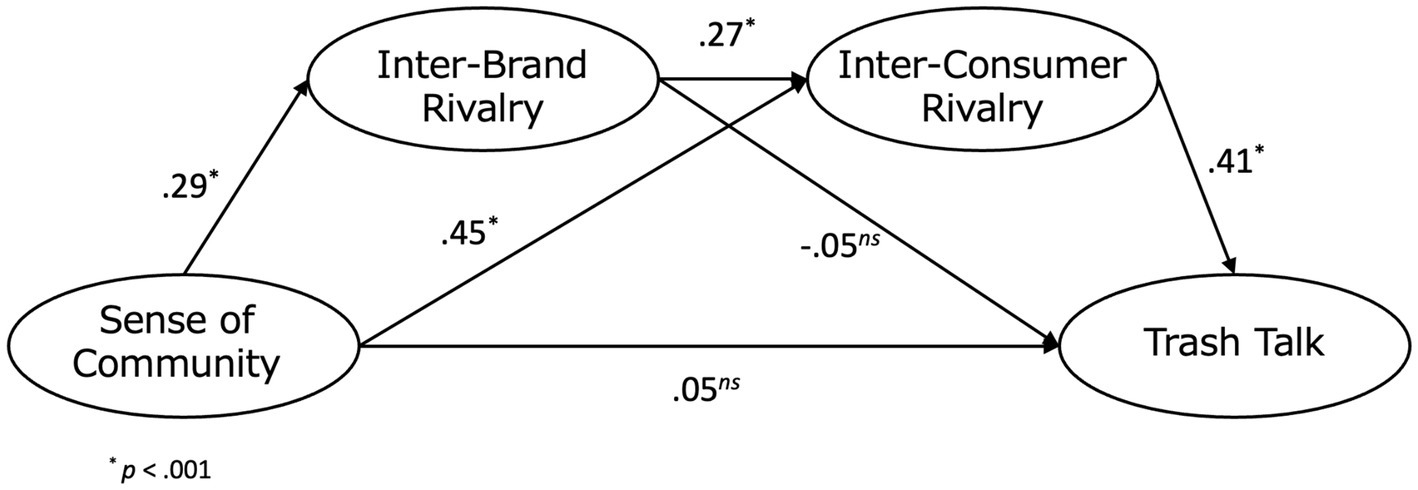

In examining the hypothesis, the findings revealed that inter-brand rivalry did not significantly mediate the relationship between a sense of community and trash talk (95% CI [−0.049, 0.016], β = −0.01, SE = 0.02). Although a sense of community positively affected inter-brand rivalry (β = 0.29, SE = 0.14, p < 0.001), inter-brand rivalry did not positively affect trash talk (β = −0.49, SE = 0.02, p = 0.374).

Inter-consumer rivalry significantly mediated the relationship between a sense of community and trash talk (95% CI [0.120, 0.258], β = 0.19, SE = 0.04). A sense of community positively affected inter-consumer rivalry (β = 0.45, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001). Inter-consumer rivalry then positively affected trash talk (β = 0.41, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001).

The sequential mediation indirect effect, wherein a sense of community indirectly affects trash talk through inter-brand rivalry and inter-consumer rivalry, was significant (95% CI [0.015, 0.053], β = 0.03, SE = 0.01). Although an indirect effect of a sense of community on trash talk was observed, no significant direct effects were identified (β = 0.05, SE = 0.06, p = 0.366). The total effect of a sense of community on trash talk was significant (95% CI [0.131, 0.280], β = 0.20, SE = 0.04). All results are presented in Figure 2. In conclusion, H2 was not supported, while H3 and H4 were supported.

5 Discussion

This study examined how a sense of community influences trash talk behavior, focusing on the mediating roles of inter-brand and inter-consumer rivalry. The results confirmed Hypothesis 1 (H1), demonstrating that a stronger sense of community directly leads to more negative behaviors toward rival brands. However, this direct effect disappeared when the two types of rivalry were introduced as mediators.

Further analysis of the underlying mechanisms revealed that inter-brand rivalry did not mediate this relationship (H2), consistent with Liao et al. (2023), who found that brand rivalry primarily leads to passive behaviors, such as brand avoidance, rather than active negative behaviors like trash talk. In contrast, inter-consumer rivalry emerged as a significant mediator (H3), indicating that heightened group-level competition directly fosters active negative behaviors, supporting Hickman and Ward’s (2007) argument that perceptions of in-group superiority drive consumers to engage in trash talk.

Additionally, our sequential mediation model (H4) revealed that a sense of community first intensifies inter-brand rivalry, which then escalates into inter-consumer rivalry, ultimately fostering trash talk behavior. This chain reaction suggests that brand-level competition evolves into consumer-level rivalry, further promoting negative behavioral outcomes. These findings underscore the paradoxical role of a sense of community in encouraging negative behaviors through the complex interplay of brand and consumer rivalry dynamics.

6 Implication

6.1 Theoretical implications

This study offers three significant theoretical contributions to the understanding of consumer behavior and brand communities. First, it illuminates the previously underexplored dark side of a sense of community. While existing research has extensively documented the positive outcomes of community belonging, such as enhanced word-of-mouth intentions and brand loyalty (Bergkvist and Bech-Larsen, 2010; Carlson et al., 2008; Kohls et al., 2023; Swimberghe et al., 2018), the potential negative consequences have received limited attention. By quantitatively examining the relationship between a sense of community and trash talk, this study extends the work of scholars who have investigated similar phenomena in brand community identification contexts (Hickman and Ward, 2007; Marticotte et al., 2016).

Second, this research enhances our understanding of how rivalry mediates the relationship between a sense of community and trash talk. By distinguishing between inter-brand and inter-consumer rivalry, we reveal a more nuanced perspective in which inter-brand rivalry alone does not directly lead to trash talk but contributes to negative behaviors through its interaction with inter-consumer rivalry. This finding adds complexity to the existing discourse on rivalry in consumer behavior research.

Third, our sequential mediation model challenges the assumption of a direct relationship between a sense of community and trash talk. These findings indicate that the relationship between a sense of community and trash talk is more complex than previously assumed, requiring specific mediating factors. In fact, an analysis without mediating variables showed a significant effect of a sense of community on trash talk. However, when rivalry relationships were incorporated as mediating variables, the direct effect became non-significant.

6.2 Managerial implications

These findings have some critical implications for marketing practitioners. First, while fostering a sense of community remains a valuable marketing strategy, managers must be aware that it can unintentionally encourage hostile consumer behaviors. To protect brand image and maintain positive relationships with competitors’ consumers, companies should carefully monitor consumer interactions. To mitigate potential negative effects, brands should frame competition at the brand level rather than promoting direct rivalry among consumers. Our findings indicate that while inter-brand rivalry alone does not significantly increase trash talk, inter-consumer rivalry does.

Furthermore, according to the findings of the present study and Hickman and Ward (2007), when consumers do not perceive out-groups as rivals, trash talk does not occur. This suggests that strengthening the positive aspects of a brand community without making comparisons to out-groups can help prevent trash talk about competitors. In other words, campaigns that foster a positive self-perception without emphasizing rivalry are likely to be effective.

Companies that have adopted this type of promotional strategy include LEGO and Allbirds. For example, LEGO’s “Rebuild the World” campaign, launched in 2019, strategically shifts consumer engagement from competition to creativity and collaboration. Rather than emphasizing superiority over competing toy brands, the campaign encourages users to see LEGO as a tool for imaginative exploration and problem-solving. This approach fosters a positive sense of community without positioning rival brands as inferior, effectively reducing inter-brand rivalry while strengthening brand attachment.

Allbirds strategically cultivates a sense of community that is centered on shared values rather than market competition. The brand’s slogan, “We Are Allbirds” fosters a collective identity among its consumers by emphasizing sustainability and environmental responsibility. Instead of differentiating itself through direct comparisons with competitors, Allbirds builds loyalty by reinforcing a sense of community around a movement that extends beyond footwear. This approach minimizes inter-consumer rivalry and encourages positive brand advocacy, reducing the likelihood of trash talk against competing brands.

6.3 Limitations and future research

This study has three primary limitations that suggest directions for future research. First, our focus on Japanese consumers raises questions about the cross-cultural applicability of our findings. Cultural dimensions such as individualism and collectivism (Hofstede and Hofstede, 2004) may influence how rivalry and community dynamics manifest across different societies. Moreover, the study’s broad approach, not specifying particular product categories or brands, leaves room for investigation of how these dynamics might vary across different market contexts (Muniz and Hamer, 2001).

Second, while our study identifies the relationship between a sense of community and trash talk, further research is needed to explore the underlying psychological mechanisms. Particularly intriguing is the unexpected finding that neither a sense of community nor inter-brand rivalry directly influences trash talk, highlighting the need for a more detailed examination of the mediating and moderating variables involved. Additionally, future research could achieve a deeper understanding by incorporating affective concepts central to brand research, such as brand attachment and engagement.

Addressing these limitations through future research will not only deepen theoretical understanding but also enable the development of more effective marketing strategies that can harness the benefits of community while mitigating its potential negative effects.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Kansai University Research Ethics Review Committee for Studies Involving Human Subjects Affiliation: Kansai University, Japan. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI: 23K01644.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. While preparing this work, the author use ChatGPT to improve the language and readability of sentences, and check grammar and spelling. After using this tool/service, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Algesheimer, R., Dholakia, U. M., and Herrmann, A. (2005). The social influence of brand community: evidence from European car clubs. J. Mark. 69, 19–34. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.69.3.19.66363

Arnould, E. J., Arvidsson, A., and Eckhardt, G. M. (2021). Consumer collectives: a history and reflections on their future. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 6, 415–428. doi: 10.1086/716513

Arvidsson, A., and Caliandro, A. (2016). Brand public. J. Consum. Res. 42, 727–748. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucv053

Ashforth, B. E., and Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 14:20. doi: 10.2307/258189

Attiq, S., Hasni, M. J. S., and Zhang, C. (2023). Antecedents and consequences of brand hate: a study of Pakistan’s telecommunication industry. J. Consum. Mark. 40, 1–14. doi: 10.1108/jcm-04-2021-4615

Aust, F., Diedenhofen, B., Ullrich, S., and Musch, J. (2013). Seriousness checks are useful to improve data validity in online research. Behav. Res. Methods 45, 527–535. doi: 10.3758/s13428-012-0265-2

Bagozzi, R. P., and Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 16, 74–94. doi: 10.1007/bf02723327

Bauer, B. C. (2022). Strong versus weak consumer-brand relationships: matching psychological sense of brand community and type of advertising appeal. Psychol. Mark. 40, 791–810. doi: 10.1002/mar.21784

Berendt, J., Uhrich, S., and Thompson, S. A. (2018). Marketing, get ready to rumble—how rivalry promotes distinctiveness for brands and consumers. J. Bus. Res. 88, 161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.03.015

Bergkvist, L., and Bech-Larsen, T. (2010). Two studies of consequences and actionable antecedents of brand love. J. Brand Manag. 17, 504–518. doi: 10.1057/bm.2010.6

Bergkvist, L., and Rossiter, J. R. (2007). The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. J. Mark. Res. 44, 175–184. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.44.2.175

Carlson, B. D., Suter, T. A., and Brown, T. J. (2008). Social versus psychological brand community: the role of psychological sense of brand community. J. Bus. Res. 61, 284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.06.022

Carron, A. V., and Brawley, L. R. (2000). Cohesion: conceptual and measurement issues. Small Group Res. 31, 89–106. doi: 10.1177/104649640003100105

Chang, C.-W., Ko, C.-H., Huang, H.-C., and Wang, S.-J. (2019). Brand community identification matters: a dual value-creation routes framework. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 29, 289–306. doi: 10.1108/jpbm-02-2018-1747

Cova, B. (1997). Community and consumption: Towards a definition of the “linking value” of product or services. Eur. J. Mark. 31, 297–316. doi: 10.1108/03090569710162380

Demiray, M., and Burnaz, S. (2019). Exploring the impact of brand community identification on Facebook: firm-directed and self-directed drivers. J. Bus. Res. 96, 115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.016

Douglas, S. P., and Craig, C. S. (1983). International marketing research. Harlow, England: Longman Higher Education.

Ewing, M. T., Wagstaff, P. E., and Powell, I. H. (2013). Brand rivalry and community conflict. J. Bus. Res. 66, 4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.017

Ferguson, C. K., and Kelley, H. H. (1964). Significant factors in overevaluation of own-group’s product. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 69, 223–228. doi: 10.1037/h0046572

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 7, 117–140. doi: 10.1177/001872675400700202

Fisk, R., Grove, S., Harris, L. C., Keeffe, D. A., Daunt, K. L., Russell-Bennett, R., et al. (2010). Customers behaving badly: a state of the art review, research agenda and implications for practitioners. J. Serv. Mark. 24, 417–429. doi: 10.1108/08876041011072537

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2013). Multivariate data analysis: Pearson new international edition. 7th Edn. London, England: Pearson Education.

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. 3rd Edn. London, England: Guilford Press.

Hickman, T., and Ward, J. (2007). The dark side of brand community: inter-group stereotyping, trash talk, and schadenfreude. Adv. Consum. Res. 34, 479–485.

Hofstede, G. H., and Hofstede, G. J. (2004). Cultures and organizations. 2nd Edn. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional.

Hogg, M., and Abrams, D. (1988). Social identifications: a social psychology of intergroup relations and group processes. London: Routledge.

Ilhan, B. E., Kübler, R. V., and Pauwels, K. H. (2018). Battle of the brand fans: impact of brand attack and defense on social media. J. Interact. Mark. 43, 33–51. doi: 10.1016/j.intmar.2018.01.003

Iseki, S., Sasaki, K., and Kitagami, S. (2022). Development of a Japanese version of the psychological ownership scale. PeerJ 10:e13063. doi: 10.7717/peerj.13063

Japutra, A., Ekinci, Y., and Simkin, L. (2018). Tie the knot: building stronger consumers’ attachment toward a brand. J. Strat. Mark. 26, 223–240. doi: 10.1080/0965254x.2016.1195862

Japutra, A., Ekinci, Y., and Simkin, L. (2022). Discovering the dark side of brand attachment: impulsive buying, obsessive-compulsive buying and trash talking. J. Bus. Res. 145, 442–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.03.020

Japutra, A., Ekinci, Y., Simkin, L., and Nguyen, B. (2014). The dark side of brand attachment: a conceptual framework of brand attachment’s detrimental outcomes. Mark. Rev. 14, 245–264. doi: 10.1362/146934714X14024779061875

Junaid, M., Fetscherin, M., Hussain, K., and Hou, F. (2022). Brand love and brand addiction and their effects on consumers’ negative behaviors. Eur. J. Mark. 56, 3227–3248. doi: 10.1108/ejm-09-2019-0727

Keller, E., and Fay, B. (2018). The face-to-face book: why real relationships rule in a digital marketplace. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Kohls, H., Hiler, J. L., and Cook, L. A. (2023). Why do we twitch? Vicarious consumption in video-game livestreaming. J. Consum. Mark. 40, 639–650. doi: 10.1108/jcm-03-2020-3727

Laroche, M., Habibi, M. R., Richard, M.-O., and Sankaranarayanan, R. (2012). The effects of social media based brand communities on brand community markers, value creation practices, brand trust and brand loyalty. Comput. Human Behav. 28, 1755–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.04.016

Lee, H. (2005). Behavioral strategies for dealing with flaming in an online forum. Sociol. Q. 46, 385–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2005.00017.x

Liao, J., Dong, X., Luo, Z., and Guo, R. (2021). Oppositional loyalty as a brand identity-driven outcome: a conceptual framework and empirical evidence. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 30, 1134–1147. doi: 10.1108/jpbm-08-2019-2511

Liao, J., Guo, R., Chen, J., and Du, P. (2023). Avoidance or trash talk: the differential impact of brand identification and brand disidentification on oppositional brand loyalty. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 32, 1005–1017. doi: 10.1108/jpbm-07-2021-3576

Lyu, J., and Kim-Vick, J. (2022). The effects of media use motivation on consumer retail channel choice: a psychological sense of community approach. J. Electron. Comm. Res. 23, 190–206.

Mackinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., and Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behav. Res. 39, 99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4

Mamonov, S., Koufaris, M., and Benbunan-Fich, R. (2016). The role of the sense of community in the sustainability of social network sites. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 20, 470–498. doi: 10.1080/10864415.2016.1171974

Mandl, L., and Hogreve, J. (2020). Buffering effects of brand community identification in service failures: the role of customer citizenship behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 107, 130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.09.008

Marchowska-Raza, M., and Rowley, J. (2024). Consumer and brand value formation, value creation and co-creation in social media brand communities. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 33, 477–492. doi: 10.1108/jpbm-01-2023-4299

Marticotte, F., Arcand, M., and Baudry, D. (2016). The impact of brand evangelism on oppositional referrals towards a rival brand. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 25, 538–549. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-06-2015-0920

Mullen, B., and Copper, C. (1994). The relation between group cohesiveness and performance: An integration. Psychol. Bull. 115, 210–227. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.210

Muniz, A. Jr., and Hamer, L. (2001). Us versus them: oppositional brand loyalty and the Cola wars. Adv. Consum. Res. 28:355.

Muniz, A. M. Jr., and O’Guinn, T. C. (2001). Brand community. J. Consum. Res. 27, 412–432. doi: 10.1086/319618

Muñiz, A. M. Jr., and Schau, H. J. (2005). Religiosity in the abandoned apple newton brand community. J. Consum. Res. 31, 737–747. doi: 10.1086/426607

Osuna Ramírez, S. A., Veloutsou, C., and Morgan-Thomas, A. (2024). On the antipodes of love and hate: the conception and measurement of brand polarization. J. Bus. Res. 179:114687. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.114687

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Rosenbaum, M. S., Ostrom, A. L., and Kuntze, R. (2005). Loyalty programs and a sense of community. J. Serv. Mark. 19, 222–233. doi: 10.1108/08876040510605253

Sjöblom, M., and Hamari, J. (2017). Why do people watch others play video games? An empirical study on the motivations of twitch users. Comput. Human Behav. 75, 985–996. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.10.019

Swaminathan, V., Sorescu, A., Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M., O’Guinn, T. C. G., and Schmitt, B. (2020). Branding in a hyperconnected world: refocusing theories and rethinking boundaries. J. Mark. 84, 24–46. doi: 10.1177/0022242919899905

Swimberghe, K., Darrat, M. A., Beal, B. D., and Astakhova, M. (2018). Examining a psychological sense of brand community in elderly consumers. J. Bus. Res. 82, 171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.09.035

Tajfel, H. (1984). “Intergroup relations, social myths and social justice in social psychology” in The social dimension. ed. H. Tajfel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 695–716.

Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P., and Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1, 149–178. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420010202

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. (2000). “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict” in Organizational identity (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 56–65.

Turner, J. C. (1984). “Social identification and psychological group formation” in The social dimension. ed. H. Tajfel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 518–538.

Turner, J. C., Brown, R. J., and Tajfel, H. (1979). Social comparison and group interest in ingroup favouritism. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 9, 187–204. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420090207

Wang, X., Yu, C., and Wei, Y. (2012). Social media peer communication and impacts on purchase intentions: a consumer socialization framework. J. Interact. Mark. 26, 198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.intmar.2011.11.004

Wanous, J. P., and Hudy, M. J. (2001). Single-item reliability: a replication and extension. Organ. Res. Methods 4, 361–375. doi: 10.1177/109442810144003

Zarantonello, L., Romani, S., Grappi, S., and Bagozzi, R. P. (2016). Brand hate. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 25, 11–25. doi: 10.1108/jpbm-01-2015-0799

Keywords: sense of community, trash talk, inter-brand rivalry, inter-consumer rivalry, hostile behaviors

Citation: Hato M (2025) The negative impact of a sense of community on consumers: focusing on trash talk. Front. Commun. 10:1583048. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1583048

Edited by:

Naser Valaei, Liverpool John Moores University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Nela Filimon, University of Girona, SpainBiyu Guan, Guangdong University of Science and Technology, China

Copyright © 2025 Hato. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Masahiko Hato, aGF0b0BrYW5zYWktdS5hYy5qcA==

Masahiko Hato

Masahiko Hato