- 1Faculty of Philosophy and Political Science, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Almaty, Kazakhstan

- 2Institute of Philosophy, Political Science and Religious Studies by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Almaty, Kazakhstan

- 3Department of Islamic Studies, Faculty of Islamic Studies, Egyptian University of Islamic Culture Nur-Mubarak, Almaty, Kazakhstan

- 4Department of Chemical and Biochemical Engineering, Institute of Geology and Oil-Gas Business Institute named after K. Turyssov, Satbayev University, Almaty, Kazakhstan

Introduction: This study investigates the integration of Sufism into medieval Turkic nomadic culture, analyzing how Sufi rituals, saintly authority, and scholarly networks reshaped social structures and collective identity on the Eurasian steppe.

Methods: We assembled a multidisciplinary corpus, including Divan‑i Ḥikmet verses, 12th-14th‑century hagiographies, waqf endowments, archaeological surveys, and secondary literature, and applied hermeneutic coding in NVivo to identify ritual motifs and symbolic continuities. Ragin’s comparative method organized data across four dimensions: ritual form, institutional patterns, symbolic vocabulary, and succession mechanisms, with intercoder reliability ensured through author reviews.

Results: We found that communal dhikr ceremonies and whirling dances generated Durkheimian collective effervescence that amplified indigenous circle‑based traditions and accelerated Sufi adoption; that charismatic saints such as Khoja Aḥmad Yasawi transcended tribal loyalties through reputed miracles and moral prestige, founding khanqahs and neutral mazars to facilitate peaceful Islamization; and that Qurʾānic literacy, mastery of Sufi poetry, and formal ijāzas functioned as new forms of cultural capital enabling social mobility. Comparative analysis of South Asian, Anatolian, and North African cases confirms Sufism’s role as a cultural mediator adapting to local cosmologies.

Discussion: Our findings show how Sufism simultaneously preserved pre‑Islamic values and transformed Turkic society, revealing the explanatory limits of Durkheim, Weber, and Bourdieu when applied in isolation and highlighting the value of a complementary theoretical approach.

1 Introduction

The arrival of Sufism among Turkic nomads triggered significant cultural and societal shifts (Trimingham, 1998; Chittick, 2007; Özdemir, 1995; Köprülü, 1919). As Sufism spread into Central Asia, it came as a holistic spiritual framework with unique rituals and lifestyles, which greatly stimulated the evolution of Turkic philosophical inquiry (Yıldız, 2010). In the medieval expanse of the Great Steppe, Sufi tenets found resonance with preexisting shamanistic and Tengriist customs, enabling nomadic groups to adopt Islam in a manner that fortified rather than supplanted their indigenous perspectives (Bakhshandeh et al., 2015; Çakmakçi et al., 2006; Şahin, 2003). The mystical facet of Islam appealed to the Turks because it offered them access to the broader achievements of world civilization (through mastery of Arabic and integration into Islamic culture) without sacrificing their own cultural distinctiveness (Şahin, 2003; Karatay, 2001). By emphasizing inner refinement and direct spiritual encounter, Sufism provided previously animist or shamanist Turkic populations with a pathway to weave the new faith into their ancestral belief systems (Chittick, 2007).

From a sociological standpoint, the proliferation of Sufism among nomadic Turks can be analyzed through the lenses of collective ritual, leadership legitimacy, and prevailing cultural value systems. Émile Durkheim’s notion (Durkheim, 1995) of collective effervescence—the powerful communal energy and solidarity felt during shared rituals—proves particularly illuminating (Schimmel, 1975). Nomadic Turkic societies, much like others, organized communal events (such as feasts, dances, and zikr gatherings) that generated intense shared emotions and reinforced social cohesion (Pizarro et al., 2022). The Sufi practice of dhikr (remembrance of God, often accompanied by music and movement) and the whirling dance (Sema) exemplify how spiritual ceremonies functioned as social adhesives, producing ecstatic moments of unity that consolidated group identity (Green, 2012). Through these rituals, abstract doctrines were transformed into vivid, lived experiences, thereby deepening communal commitment to the nascent Islamic-Sufi paradigm. Durkheim observed that such intense collective experiences could reshape cultural symbols and fortify a society’s moral order (Durkheim, 1995). In the context of Turkic nomads, sacred gatherings around Sufi saints or at the tombs of revered figures (mazars) became epicenters of collective effervescence, fostering an emotional embrace of Islam (Schimmel, 1975).

Max Weber’s theory of charismatic authority offers another interpretive angle on this cultural transformation (Weber, 1978). Weber described charismatic authority as legitimacy founded on the perceived extraordinary qualities of a leader (Trimingham, 1998). Such figures were venerated not merely for formal titles or lineage but for their spiritual insight, miraculous deeds, and moral excellence—qualities deemed “of divine origin” by their followers (Schimmel, 1975). These Sufi masters (often referred to as auliya, or saints) commanded devotion through their personal sanctity and ability to mediate between the human and the divine. Their influence often transcended tribal boundaries, enabling them to unite various clans under a spiritual commonality. Consequently, Islam’s acceptance in the Steppe was frequently mediated by these charismatic saints whose presence made the new faith both accessible and consonant with Turkic values. Instead of coercive conversion, it was the compelling spiritual authority of these individuals that facilitated a comparatively peaceful Islamization. They embodied an authority parallel to traditional tribal leadership—rooted in sanctity and wisdom. Over time, elements of this charismatic authority became institutionalized (in Weber’s terms) into recognized Sufi lineages or custodianships of shrines, merging with existing leadership structures and giving rise to new social institutions centered on khanqahs (Sufi lodges) and pilgrimage sites. Empirically, this routinization involved (a) codifying ritual responsibilities (such as inheriting specific dhikr chants, adhering to dress norms, and maintaining shrine-upkeep protocols) and (b) establishing endowments (waqf) whose revenues underwrote annual festivals. This process generated tensions—some younger adherents chafed under rigid lineage rules, while older custodians defended these ritual continuities—demonstrating Weber’s point that routinization can both stabilize and ossify charisma (Haselby, 2024).

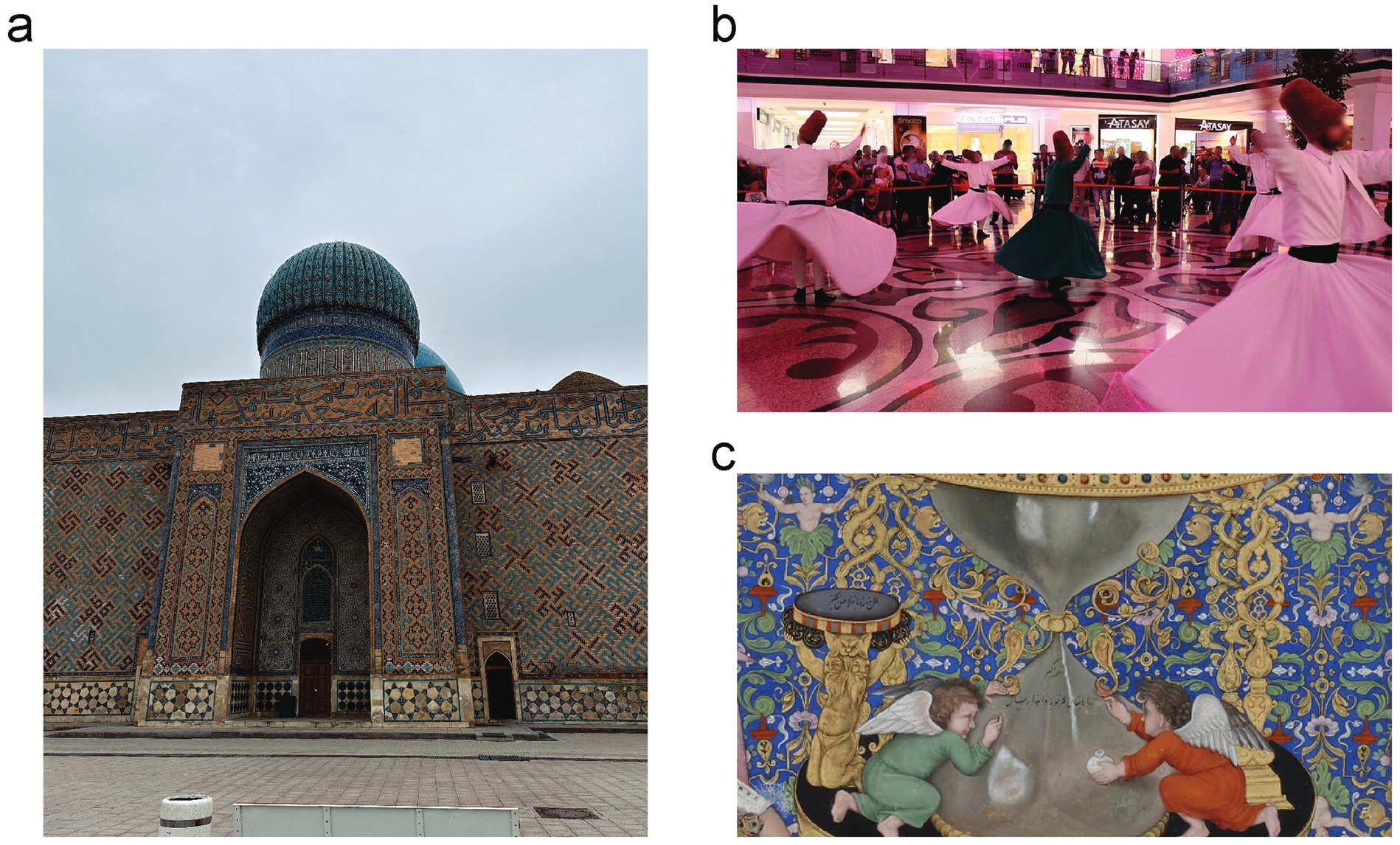

Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital further illuminates how Sufism reshaped Turkic nomadic society (Bourdieu, 1986). Cultural capital encompasses non-economic assets—such as knowledge, skills, education, and symbolic goods—that confer status and influence. Embracing Islam via Sufism granted Turkic nomads access to a vast reservoir of cultural capital from the larger Islamic world (Shahi, 2019). Proficiency in Arabic script and Qur’anic literacy, familiarity with Sufi poetry and philosophy, and participation in transregional Sufi networks became markers of social distinction and channels to new forms of prestige. This cultural capital manifested in two key forms. First, “embodied” dispositions: itinerant disciples dedicated years to memorizing the poetry of Yasawi’s Divan-i Hikmet, mastering virtuoso recitation techniques and the nuanced metaphors of Sufi thought (Figure 1a). As a 13th-century chronicler records, a disciple’s capacity to “recite in Turkic with perfect rhyme and convey spiritual nuance” evolved into a highly prized social skill, rivaling horsemanship (Temirbayev and Temirbayeva, 2021). Second, “institutionalized” capital: obtaining an ijāza from a Sufi sheikh or receiving a Qur’an codex—often produced in Bukhara—functioned as credentials that legitimized a nomadic leader’s claim to authority beyond mere tribal rank. These dual forms of cultural capital explain why certain clan chiefs shifted from traditional shamanic lineages to sponsoring Sufi scholars: the return on investment included both divine endorsement and tangible social mobility. For example, a nomadic chieftain who patronized Sufi scholars or affiliated himself with a respected Sufi order could bolster his legitimacy and connect his community with the cosmopolitan culture of the Islamic caliphates. Sufi values also reoriented concepts of honor and virtue: the Turkic ideal of the “perfect human” (insan-i kamil), promulgated by Sufi teachings, elevated traits like humility, piety, and divine love as esteemed virtues, thereby reshaping the community’s honor code (Chittick, 2007). This influx of cultural capital facilitated social mobility within a stratifying society—for instance, former pagan shamans could emerge as respected Sufi healers, and clan leaders might become Islamic scholars or patrons, thus preserving their influence amidst cultural change (Watson-Jones and Legare, 2018).

Figure 1. Sufi art and architecture: from central Asian Mausolea and ritual dance to Mughal miniatures (a) The Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi in Turkestan (Kazakhstan). The Mausoleum inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2003—features a monumental pishtaq portal surmounted by a soaring turquoise dome. Its entire brick façade is enveloped in intricate geometric tile mosaics of deep blue, turquoise, and ochre, exemplifying the Timurid architectural mastery recognized by UNESCO for its outstanding universal value in Islamic art and Central Asian cultural heritage (Authors’ own figure). (b) Sufi whirling in iraqi kurdistan in Family mall (Serdar, 2013). A troupe of Mevlevi Whirling Dervishes performing the sema ceremony within a modern indoor venue. Each dervish is attired in the traditional tall felt hat (sikke) and long, white robe (tennure), whose sweeping skirts expand outward as the dancers rotate. The central figure, distinguished by a green robe, leads the ritual, symbolizing spiritual guidance. Their circular motion unfolds across a polished floor inscribed with large, flowing motifs that visually echo the rotational movement of the dancers. Observers encircle the performance area behind a low barrier, while additional onlookers view from an elevated gallery. The ambient pinkish lighting unites the contemporary architectural setting with the centuries-old Sufi practice, underscoring the sema’s enduring cultural resonance. (c) Close-up of the Mughal miniature painting “Jahangir preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings,” (c. 1615–18) (Weekes, 2018; Bichitr, 2025). This detail shows two cherubic figures (putti) kneeling before a monumental, transparent hourglass that forms the base of Emperor Jahangir’s throne. The hourglass is not merely decorative—It alludes to the onset of the second Islamic millennium (c. 1591–92) and carries a Persian inscription reading “God is great. O Shah, may the span of your reign be a 1000 years.” By placing Jahangir atop this timepiece, the painter emphasizes the emperor’s divinely sanctioned, timeless authority, while the putti – Inscribing the falling sand – underscore the cosmic order over which Jahangir presides.

This article then examines the interplay between pre-Islamic belief systems and Sufi Islam in the medieval Turkic milieu, exploring how Sufi rituals and symbols corresponded with or transformed indigenous practices. We also analyze the role of Sufi institutions and saints in shaping collective identity and community organization, employing Durkheim’s, Weber’s, and Bourdieu’s theories to shed light on these dynamics (Weber, 1978). Our findings indicate that Durkheimian effervescence aptly explains the rapid emotional embrace of dhikr ceremonies, though it underestimates the ways in which political rivalries among emerging Kazakh khans sometimes co-opted these same rituals for status contests rather than pure spiritual unity. Similarly, Weber’s model of charismatic authority captures how individual sheikhs initially transcended tribal divisions; yet, as charismatic authority became routinized into lineages, new power dynamics emerged in which certain lineages monopolized spiritual influence—contradicting Weber’s assumption that routinization invariably disperses authority. Bourdieu’s framework on cultural capital reveals how Qur’anic literacy and Sufi poetic mastery served as status markers, but it requires supplementation to account for how shamanic embodied knowledge continued to wield social significance. By recognizing these tensions, we deploy each theoretical lens not simply to categorize phenomena but to probe their explanatory limits and propose complementary perspectives where fitting.

Finally, we incorporate comparative examples from other regions—particularly South Asia and the wider Islamic world—to demonstrate that the integration of Sufism with local culture represents a widespread pattern. By weaving together these sociological insights, we aim to elucidate the mechanisms through which Sufi motivations shaped cultural values, social institutions, and collective identity among medieval Turkic nomads. This approach not only enhances the theoretical rigor of our analysis but also situates the Turkic experience within a broader global framework of religious and cultural transformation (Trimingham, 1998) (Figure 1).

2 Methods

2.1 Source selection

We constructed a comprehensive corpus spanning the eleventh through fourteenth centuries, combining primary texts, archaeological reports, and secondary scholarship. Divan-i Ḥikmet (Khoja Ahmed Yasawi’s Turkic poems), supplemented by contemporaneous hagiographies. Medieval chronicles in Persian and Chagatai, such as Tarīkh-i Rashīdī. Travelers’ accounts, online facsimile at British Library Digital Collections. Archaeological surveys and epigraphic notices from Turkestan shrines (12th–14th c.), accessed via the UNESCO World Heritage Centre database and the Kazakh Institute of Archeology archives. All primary sources were read in their original languages (Old Turkic runic, Chagatai, Persian) or in bilingual editions (Kazakh-Russian, Turkish-English). Translations were cross-checked against at least two published editions to resolve discrepancies (Temirbayev and Temirbayeva, 2021).

2.2 Hermeneutic interpretation

We adopted a three-stage hermeneutic workflow, drawing on Gadamer’s fusion-of-horizons (Gadamer, 1975) and Miles and Huberman’s coding procedures (Miles and Huberman, 1994). Close reading of Yasawi’s verses and shrine inscriptions identified recurrent motifs. Each motif was assigned a code in NVivo 12 following Miles and Huberman’s (1994) guidelines (Miles and Huberman, 1994). Using Gadamer’s hermeneutic circle (Gadamer, 1975), we situated each motif within its socio-cultural milieu—nomadic spatial practices, tribal customs, and Timurid patronage. For instance, “circle” references in Yasawi’s poetry were cross-referenced with archaeological plans showing circular madrasa precincts. Contextual keywords were mapped onto coded segments to trace continuity from pre-Islamic shamanic symbolism. We juxtaposed literal, descriptive layers (“whirling as dance”) with esoteric Sufi reinterpretations (“whirling as cosmic unity”), thereby tracking symbolic evolution (Figure 1b). Synthesis meetings among coauthors were conducted biweekly to discuss divergent readings and ensure intercoder reliability (Krippendorff, 2004).

2.3 Comparative framework

Comparison was operationalized via Ragin’s comparative method (Ragin, 1987), organizing data into a four-dimensional matrix: ritual form, institutional patterns, symbolic vocabulary, and succession mechanisms. Central Asian circle-dance ceremonies (11th-14th c.) were compared with South Asian qawwali gatherings (Ali, 2002) and Anatolian dhikr rituals. Data points were coded quantitatively. We examined khanqah endowments recorded in waqf deeds alongside analogous South Asian Sufi khanqah structures (Ernst, 1997). Institutional codes allowed cross-regional comparison. Steppe metaphors were contrasted with Indo-Persian imagery using Schimmel’s compendium (Schimmel, 1975). Each symbolic element was assigned a code and contextualized using corpora from digital manuscript repositories. The Turkic model (flexible, clan-mediated spiritual authority) was contrasted with hereditary silsila systems in South Asia (Eaton, 1978) and Ottoman ṭarīqa structures (Karamustafa, 2007). Sources included genealogical charts in Sufi biographies accessed via Al-Maktaba al-Shamela (Al-Kubra, 1200).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Origins and diffusion of Yasawī Sufism

Khoja Ahmed Yasawi (1141–1166) was a central figure in spreading Sufi Islam among Turkic nomadic tribes. Born in Yasi (present-day Turkestan), he studied in Bukhara and then returned to the steppe, where he composed his Divan-i Hikmet in Old Turkic. By using Turkic poetic meters and weaving in local shamanic metaphors, Yasawi’s teachings resonated far more deeply than the Arabic-only scholarship of his time (de Jong, 1987).

Disciples memorized his Turkic poems and slogans, adopting ritualized recitations at local yurt-gatherings. This embodied practice internalized both Sufi dhikr and indigenous steppe cosmology. Early 13th-century chronicles record disciples “reciting in Turkic with perfect rhyme and spiritual nuance,” demonstrating how embodied memorization carried Sufi baraka into daily nomadic life.

After Yasawi’s death, several close disciples received his ijāza (teaching licenses) and founded the first khanqahs (Sufi lodges) along pilgrimage routes. They endowed waqf funds to support year-round rituals. By the mid-13th century, a network of at least 10 khanqahs—each claiming direct baraka through “Yasawi’s lineage”—linked the Syr Darya to the Urals. These lodges standardized dhikr protocols (chant sequences, dress codes, shrine-maintenance) and generated revenues that funded annual festivals (de Jong, 1987).

As charisma routinized, five principal “Yasawi lineages” emerged, each headquartered at a different shrine. Waqf records from 1,350 CE show that competing lineages vied for pilgrimage revenues; 14th-century Kazakh sources recount disputes over who “legitimately” held Yasawi’s relics. Thus, while Yasawi’s original charisma had once unified many tribes, his institutional successors often clashed over spiritual—and economic—premiership (de Jong, 1987).

3.2 Integrating Sufi mysticism with steppe traditions

A notable aspect of Central Asian history is how Islam was assimilated peacefully into the nomadic lifestyle (Amitai-Preiss, 1999). By the sixth through eleventh centuries CE, the Turkic communities of the Altai and Turan had formed a dynamic civilization characterized by a rich tapestry of beliefs (Foltz, 2010). Their indigenous religion—commonly called Tengriism—centered on shamanistic practices and a nature-based veneration of Tengri alongside a host of ancillary spirits (Findley, 2005). When Islam began to penetrate the steppe, it might have clashed directly with these long-standing traditions. Instead, Sufi missionaries and mystics served as mediators, skillfully bridging the two worldviews (Findley, 2005). Owing to its cosmological orientation and emphasis on personal spirituality, Sufism proved highly compatible with Tengriism’s focus on harmony between humans and the cosmos (Satybaldiev et al., 2024).

Turkic conversion to Islam typically involved a gradual overlay of Islamic practices atop existing Tengriist foundations rather than an abrupt rejection of prior customs. Scholars note that early conversions often bore a “conditional formal character,” where individuals professed Islamic faith outwardly while retaining many pre-Islamic customs in everyday life. The deeper Islamization process was driven by Sufi teachers who demonstrated that monotheistic devotion and reverence for ancestral spirits and nature were not mutually exclusive. For example, Sufi veneration of saints (wali) found a parallel in the nomads’ reverence for ancestral spirits and heroic shamans; many Islamic saints in Turkic regions were identified with local spirit-protectors or legendary shamans. Similarly, the Sufi ritual of Ziyarat corresponded with Tengriist pilgrimages to sacred springs or mountains. Through such analogies, Sufism effectively indigenized Islam, embedding it within the fabric of Turkic cosmology (Hill, 2009).

A prime example of this syncretic process is Khoja Ahmed Yasawi (1093–1,166), a Central Asian Sufi poet and teacher whose influence on the Turkic world was profound. Yasawi, revered as a sage of the steppe, composed his poetry in the Turkic vernacular rather than Arabic or Persian, rendering Islamic mysticism accessible to nomads in their mother tongue. His Divan-i Hikmet taught Sufi principles using metaphors familiar to steppe dwellers—portraying the yurt as the world and the spiritual journey as akin to life’s nomadic path (Yesevi, 2018). The Yasawi Sufi order blended shamanic elements—such as incorporating the kobyz fiddle into ritual practice—with Islamic teachings. This syncretic approach allowed a Turkic shaman to convert to Islam yet continue functioning as a Sufi dervish, channeling spiritual power in culturally recognizable ways. Over successive generations, this fusion reshaped the Turkic cultural code: Islamic concepts of one God and prophecy merged with Tengriist notions of the eternal blue sky and sacred ancestors, forging a distinct Turko-Islamic identity (Yesevi, 2018).

Importantly, this transformation was reciprocal. While Islam acquired Turkic characteristics, the Turkic nomadic culture itself evolved by integrating new ethical and philosophical dimensions. The Turkic ideals of erdem and kunilik were reinterpreted through the lens of Islamic ethics. Qualities prized on the steppe—hospitality, bravery, and honor—acquired new expressions via Islamic charity, jihad, and futuwwa. The outcome was a layered cultural identity: on the surface, the society presented as Islamic, yet it retained a worldview attuned to natural rhythms and ancestral memory beneath its Islamic façade. Sufi practices acted as the mediating force that ensured continuity amid change. As one scholar observes, Islam in Turkic lands became “Islamo-Sufi,” a blend that enabled the Turkic peoples to enter the broader Islamic civilization “without destroying their spiritual landscape” (Gabitov, 2012).

3.3 Ritual performance and communal unity

Rituals in ancient Turkic society carried rich layers of symbolism, and the incorporation of Sufi practices only deepened this symbolic vocabulary (Chittick, 1989). The circle occupied a central place in nomadic spirituality, signifying life’s recurring cycles, the cosmic order, and communal solidarity. Just as many other cultures, Turkic peoples understood existence itself as rhythmic: sunrise and sunset, seasonal shifts, and the passage between birth and death all unfolded in repeating loops (Chittick, 1989; Nowicka, 2014). Before Islam arrived, shamans frequently led their communities in circular dances, their steps synchronized to drumbeats that echoed nature’s pulse (Mahatma and Saari, 2021). When Sufi ideas filtered into the steppe, they reinforced these circular motifs. In Sufi cosmology, God is likened to a circle—endlessly encompassing, with no fixed periphery—mirroring ideas of an omnipresent Divine (Nowicka, 2014). Within Turkic Sufi ceremonies, the circle ceased to be merely geometric; it became a living model of the universe, symbolizing the Divine order that shapes all existence (Martin van Bruinessen, 2007).

With the advent of Islam, circular dancing assumed a renewed spiritual weight. The most iconic example is the Sema performed by Mevlevi dervishes. In the Sema, dervishes revolve around a fixed point, one hand reaching skyward and the other pointing toward the earth—a gesture uniting the heavenly with the earthly (Abdul Hamid et al., 2021). To Turkic Sufis, this rotating movement embodied dhikr in physical form. As the participants whirled, they chanted or silently reflected on sacred formulas, slipping into a trance-like ecstasy. In that state, the spinning dancer represents a soul circling Divine Truth as planets circle the sun. Each turn both summons the Divine and surrenders to it (Fremantle, 1976).

Anthropologists interpret such coordinated movement under a spiritual guide as a prime example of Durkheim’s collective effervescence (Durkheim, 1995). When Turkic groups assembled—whether within the round interior of a yurt or on an open steppe plain—to partake in ritual dances or zikr gatherings, individuals often reported a profound merging with both their community and the cosmos (Mahatma and Saari, 2021). Their personal selves dissolved into a tribal unity under God. This aligns with Durkheim’s insight that during communal rites, people “share the same thoughts and participate in the same actions,” generating a unifying energy. In those emotionally charged moments—marked by Sufi poetry recitations, the steady drumming that harkens back to shamanic tambourines, and the whirling dance—the boundary between sacred and mundane blurred (Foltz, 2010). A simple dance transformed into a sacred rite, and the entire community became suffused with a sense of the holy. So powerful was this effervescence that participants sometimes claimed to witness marvels or achieve spiritual visions during the ceremony. Even after the ritual concluded, the collective memory of that ecstasy reinforced group cohesion and strengthened shared beliefs. In essence, Sufi rituals offered a visceral, emotional anchor for faith that complemented the intellectual acceptance of Islamic teachings (Khakimov, 2005).

The symbolism of the circle extended beyond dance into other cultural forms. Yurts themselves are round, and traditional gatherings were arranged in concentric formations (Abdul Hamid et al., 2021). Likewise, in Turkic games and councils, people sat in circles, reflecting ideals of equality and unbroken continuity. Sufi teachings deepened this symbolism by emphasizing that Divine love encircles all—much like the brotherhood within a Sufi order where every member, regardless of rank, joins the zikr circle on equal footing. After Islam’s spread, Turkic art and poetry frequently incorporated circular motifs (including mandala-like designs and floral roundels), blending pre-Islamic imagery with Sufi themes. Today, the persistence of circular folk dances across Central Asia and Anatolia—where participants link hands and move as one ring—stands as testimony to this heritage. Though now largely cultural performances, their origins lie in sacred rituals intended to foster communal harmony and connect with higher powers (Khakimov, 2005).

Beyond dancing, shared music and chanting in Sufi practice also forged communal bonds. Turkic nomads had long sung epic poems and employed throat chanting; these traditions merged easily with Sufi qasida (devotional hymns) and zikr sessions. Repetitively invoking God’s names or reciting poetry until ecstasy created a synchronized rhythm among participants, aligning their emotional states. Contemporary social psychology research confirms that synchronized activities—like chanting or dancing together—heighten feelings of unity and encourage prosocial behaviors (Pizarro et al., 2022). This modern finding resonates with the experiences of Turkic communities centuries ago: collective sacred rituals paved the way to social cohesion. In summary, by embracing the circle archetype and using dance and song as their mediums, Sufi orders in Turkic society preserved an ancient form of collective worship and amplified it—ensuring that, even as the religious content transformed, a familiar mode of communal expression and solidarity endured (Aldeen, 2024).

3.4 Charismatic saints and power structures

The expansion of Sufism among Turkic nomads cannot be fully understood without recognizing the pivotal role of individual Sufi saints and masters. These figures functioned as transformative agents, steering tribes and communities toward novel spiritual paths. In many cases, they rose to prominence as Weberian charismatic authorities—leaders whose legitimacy derived from perceived exceptional qualities and a divine endorsement (Nowicka, 2014). Nomadic tribes, with their relatively fluid leadership structures and merit-based respect systems, provided an ideal environment for such charisma to take root. When a Sufi master entered a nomadic encampment, his reputed healing powers, profound insights, or miraculous endurance in the harsh steppe would lead locals to see him as graced by Tengri or Allah. Tales abounded of these saints communing with nature—causing water to flow in arid lands, taming wild beasts, or foretelling the weather—miraculous feats that resonated deeply with a culture whose survival depended on close ties to nature (Rahman, 2009; Seesemann, 2008).

A case in point is the lore surrounding Ahmed Yasawi after his passing: local traditions held that wolves stood guard at his tomb and that earth taken from near his grave possessed healing properties (Schimmel, 1975). Such accounts elevated Yasawi to the status of a supernatural guardian of the land (Foltz, 2010). Similarly, Suleyman Bakırgani, a disciple of Yasawi, was believed to summon rain during periods of drought through his prayers (de Jong, 1987). Devotees saw these saints as intercessors, swearing oaths by their names, seeking their counsel in conflicts, and crediting clan fortunes to their blessings (Abdul Hamid et al., 2021).

Weber’s observation that charismatic authority is inherently unstable and requires continual reaffirmation held true in the Turkic Sufi context. To stabilize and perpetuate the saint’s influence, Sufi lineages and brotherhoods formed around these figures, transmitting the saint’s baraka (spiritual grace) to successive generations. In doing so, charisma became partially institutionalized, creating an authority structure parallel to that of tribal chieftains (Mahatma and Saari, 2021). In certain instances, Sufi sheikhs wielded more influence than local khans, able to mobilize followers across tribal divisions—for example, by calling joint pilgrimages or urging collective action against perceived injustices—relying entirely on their spiritual prestige (Schimmel, 1975).

The authority vested in Sufi saints also played a key role in conflict resolution and alliance-building. A shared reverence for a holy figure could draw together rival tribes. Mazars (pilgrimage sites) dedicated to saints evolved into neutral spaces where various groups could meet peacefully. These gatherings often combined religious devotion with social and economic exchanges, functioning much like tribal councils or fairs under a spiritual ethos of unity rather than political (de Jong, 1987).

A Mughal Indian painting exemplifies a broader pattern: political rulers frequently sought endorsement from Sufi luminaries (Findley, 2005). In the Turkic sphere, khanate leaders—and later Mughal emperors of Turkic-Mongol descent—visited Sufi dargahs (shrines) to legitimize their reigns. For instance, Kazakh khans patronized the shrine of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi in what is now Kazakhstan, transforming it into both a royal mausoleum and a spiritual hub. By doing so, they fused conventional hereditary authority with charismatic spiritual sanction, bolstering their legitimacy in the eyes of their subjects (Nizami, 1998) (Figure 1c).

Nevertheless, the rise of charismatic religious authority sometimes clashed with established political power. Historical records note occasions when Sufi-led movements—especially if they veered toward millenarian or overtly political agendas—were suppressed by cautious rulers. More commonly, however, a mutualistic relationship prevailed: Sufi leaders advised khans, mediated between commoners and elites, and in return received endowments for khanqahs and protection for their communities. This symbiosis embedded Sufi ideals within governance and social norms without causing major ruptures. Moreover, Sufi saints often served as moral compasses for society, able to rebuke rulers (albeit tactfully) by appealing to spiritual principles (Bruinessen and Howell, 2007; Bruinessen, 2007).

The influence of Sufi saints contributed to a dual leadership paradigm in Turkic nomadic society: temporal rulers overseeing worldly affairs and spiritual guides tending to hearts and morals. Weber’s concept of charismatic authority illuminates the ascendancy of the latter: their legitimacy arose from communal belief in their extraordinary divine connection rather than inherited status or codified law (Findley, 2005). Over time, this dynamic fostered a more stratified yet integrated social order—nobles and clerics, warriors and sages each fulfilling distinct roles. Unlike the often antagonistic relationship between church and state in medieval Europe, in the nomadic Turkic world, Sufi orders and tribal leadership frequently traveled together across the steppe, jointly navigating the challenges of survival and faith (Siddiqa, 2018).

3.4.1 Janissary–Bektashi affiliation in the Ottoman context

Beginning in the late 15th century, Ottoman Janissaries (yeniçeri) were officially permitted—and in practice encouraged—to join the Bektashi Sufi order. Sultan Bayezid II (r. 1481–1512) recognized that Bektashi rites (dhikr, communal meals, moral instruction) fostered unit solidarity and loyalty to the Sublime Porte (And, 1999). Each Janissary regiment (ocak) maintained its own Bektashi sheikh, who presided over rituals of initiation (aṣāyī), blessing (berat), and collective remembrance (dhikr). In turn, Bektashi tekkes benefited from imperial endowments and protection, so long as their sermons upheld obedience to the Sultan. By the 16th century, the Bektashi order had become the de facto spiritual institution of the Janissary corps: the Sultan permitted—and even relied on—this affiliation as a means of reinforcing discipline within his elite infantry. Over time, when tensions flared (for instance, if factions of Janissaries claimed divine sanction for political demands), the Porte suppressed only the mutinous soldiers, not the Bektashi order as a whole. Thus, the Janissary–Bektashi relationship exemplifies how Ottoman rulers harnessed Sufi charisma to stabilize military structures without ceding ultimate authority (İnalcık and Quataert, 1990).

3.5 Shaping identity and social assets through Sufism

The conversion of Turkic nomads to Islam through Sufism represented not just a shift in religious beliefs but also a transformation of identity. Embracing the concept of the Ummah introduced a new supra-tribal affiliation that both complemented and at times eclipsed traditional clan loyalties. For societies long organized around lineage and tribal alliances, adopting Islam meant becoming part of a narrative that connected them to distant regions and peoples—from Arabia to Persia to Anatolia (Nowicka, 2014). Sufi teachings eased this transition by offering culturally resonant pathways into the Ummah. In learning Sufi doctrines, Turkic nomads could envision themselves as participants in a universal spiritual quest without abandoning the particularities of their steppe lifestyle (Temirbayev and Temirbayeva, 2021).

Viewed through Bourdieu’s lens of cultural capital, the embrace of Sufism involved acquiring new social assets: familiarity with Islamic theology and jurisprudence (to varying extents), the ability to recite prayers in Arabic or hymns in Persian, and an understanding of the norms of settled Muslim civilizations. Those individuals or clans who obtained this cultural capital often acted as intermediaries. For instance, members of a nomadic tribe who attended a madrassa or completed the Hajj returned with elevated prestige—they could teach others, adjudicate religious matters, and link their community to trade and scholarly networks throughout Muslim Asia. In the evolving social hierarchy, these skills were highly prized (Amitai-Preiss, 1999). Families began to take pride in producing ulama or hafiz, alongside their traditional status as warriors and herders (Huang, 2019).

At the same time, the embodied cultural capital of the steppe—expertise in horsemanship, knowledge of grazing routes, and skill in oratory through epic storytelling—did not vanish. Rather, we observe a melding of old and new forms of capital in social life. The ideal leader (khan) in later Turkic society was expected both to be a stalwart defender and a just, devout ruler (upholding Islamic justice and sponsoring religious institutions). Poetry gatherings (aitys) began incorporating Islamic themes; traditional shaman-bards (bakshis) who once chanted of Tengri and spirits now also praised Muhammad, Ali, and Sufi saints. As a result, knowing the genealogies of saints became as valued as knowing tribal lineages.

Education became another avenue for accumulating cultural capital that could elevate one’s social standing. The establishment of Sufi lodges and schools in centers like Yasi, Bukhara, and Samarkand meant that even nomadic youth sometimes spent a season studying under a Sufi master. Students learned adab, encompassing manners, ethics, and the refined tastes of Islamic civilization (Chittick, 1989). A returning student fluent in Persian etiquette or skilled in Arabic calligraphy was instantly distinguished from those without such exposure. Over generations, this contributed to a subtle social stratification: the more Islamically learned versus the less learned. Yet, Sufi ethics often mitigated stark class divisions by preaching humility and brotherhood. In fact, Sufi orders could function as parallel meritocracies: any nomad could become a Sufi aspirant (faqir) regardless of birth, and if he demonstrated sufficient spiritual aptitude, rise to become a murshid. This opened up new pathways for social mobility beyond lineage or wealth, thereby reshaping the social fabric in a significant way (Cook, 2024).

Another facet of identity formation was the emergence of a moral community. Drawing on Durkheim’s idea that religion underpins a society’s collective conscience (Amitai-Preiss, 1999), the adoption of Sufi-infused Islam among Turkic peoples gradually produced a new communal moral framework that valued umir and aruakh within a monotheistic ethical system. Concepts such as sin, salvation, and the afterlife merged with existing codes of honor. Consequently, the designation “Turk” came to implicitly mean “Muslim”—a synthesis reinforced by language (many Turkic tongues incorporated Arabic-Persian religious terms) and practices. By the era of the Kazakh Khanate, the nomadic identity was thoroughly Islamicate, albeit still tinged with pre-Islamic customs. Contemporary travelers observed that Kazakhs, for instance, invoked both Allah and the sky in their blessings and revered the Qur’an alongside their ancestral sacred sites. This dual veneration exemplifies the Sufi-mediated identity: one could remain a child of the Steppe while fully belonging to the Ummah (Carls, 2025).

Comparative examples from other regions show similar identity transformations. In South Asia, for instance, Turkic-Afghan Sufis played a central role in shaping a new Indo-Muslim identity. Sufi saints in India—such as Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti of Ajmer—won over local populations by accommodating indigenous practices and speaking the vernacular, much as Yasawi had done in the Turkic lands (van Bruinessen, 2007). Over time, Sufi teachings of divine love and human equality resonated across caste and ethnic lines (Jafri, 2006). In places like Punjab and Bengal, participation in the veneration of Sufi saints and attendance at their urs became integral to local culture, regardless of one’s original faith background, forging a composite identity. Similarly, in North and West Africa, Sufi orders such as the Qadiriyya and Tijaniyya were instrumental in Islamizing diverse ethnic groups, creating new identities. These comparative cases underline a consistent pattern: Sufism acts as a cultural catalyst, facilitating the creation of syncretic identities that smooth the transition into Islam by valuing pre-existing traditions and integrating them into a larger Islamic framework.

3.6 Cross-regional perspectives on Sufism’s influence

The involvement of Turkic nomads with Sufism formed part of a broader historical pattern in which Islamic mysticism shaped societies across regions. A comparative look at other areas reveals both distinctive traits and shared dynamics. In South Asia, for instance, Sufism played a crucial role in introducing Islam within a predominantly Hindu-Buddhist milieu (Chatterjee, 1999). Sufi figures there employed familiar strategies—such as performing qawwali music, using local vernaculars, and working reputed miracles—to draw followers, earning affection from diverse communities. Much like the way Turkic nomads integrated Tengriist elements into their Sufi practice, Indian devotees fused Sufi reverence with Hindu devotional traditions: the devotional verses of poet-saints like Kabir and Guru Nanak resonated with audiences from multiple faith backgrounds. The notion of charismatic leadership is demonstrated by personalities like Sheikh Nizamuddin Auliya of Delhi, whose khanqah provided food to thousands and whose mere presence was believed to defuse social tensions. His influence became so widely acknowledged that even Sultans sought his advice—mirroring how Turkic rulers honored their Sufi guides (Eaton, 1993).

Various Sufi orders evolved into mass movements. For example, the Sanusi order in the Maghreb and Libya not only guided spiritual life but also spearheaded anti-colonial efforts. Their leaders commanded both spiritual prestige and political sway, much as Central Asian Sufi saints could rally tribes for or against political causes. The concept of collective effervescence manifested in the massive dhikr assemblies of Naqshbandi and Shadhili orders, where entire towns joined in rhythmic devotion—akin to a nomadic encampment convening for an expansive zikr on the steppe. Such gatherings strengthened communal bonds, particularly during periods of external threat or internal upheaval (Chalcraft, 2017).

From a contemporary sociological viewpoint, one of Sufism’s greatest assets is its capacity to adapt to local cultures, offering a meaning-making framework that could incorporate existing customs and repurpose them (Trimingham, 1971). Additionally, it often served as a vehicle for social capital—membership in a Sufi order fostered networks of trust and mutual assistance (Bourdieu, 1986). Among nomads, this affiliation could translate to safe passage and hospitality when traveling across territories inhabited by different tribes within the same tariqa; in urban contexts, it might facilitate business partnerships and alliances cultivated at the lodge (tekke). Bourdieu’s idea of social capital dovetails with this: ties formed through Sufi connections bridged geographical divides, enabling trade, scholarship, and even diplomatic relations. For itinerant nomads, being part of a trans-regional Sufi network expanded their support systems beyond kinship bonds, introducing a novel form of social organization brought by Sufism (Ernst, 2011).

Moreover, the phenomenon of collective effervescence in Sufi practice has been reinterpreted in modern contexts. Contemporary events—like the Urs of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Pakistan, where thousands dance in trance, or the annual Konya festival in Turkey celebrating Rumi’s legacy with whirling dervishes—demonstrate the same principle: communal emotion, forged through rhythmic devotion, generates a potent but temporary unity that can transcend societal divisions. Sociologists today cite large-scale concerts, mass demonstrations, or sports events as secular parallels to this dynamic, but Sufi rituals have been embodying it for centuries within a religious paradigm (Pizarro et al., 2022).

3.6.1 Turkish Sufi perspectives on Zionist settlement in Palestine

During the late Ottoman period, key Turkish Sufi orders—most notably the Bektashi, Naqshbandi, and Mevlevi—generally endorsed the Sultan’s resistance to Jewish-Zionist settlement in Palestine. Sultan Abdülhamid II (r. 1876–1909), whose closest religious advisors included prominent Sufi sheikhs, famously rebuffed Theodor Herzl’s land-purchase overtures, declaring “as long as I am alive, only our corpse can be divided,” thereby underscoring the sanctity of Islamic waqf lands (Mandel, 1974). In the First World War, the Mevlevi Order even formed a dedicated regiment (Mucâhidîn-i Mevlevîyye) that served under the Ottoman Fourth Army in Palestine, actively opposing Allied and Zionist advances.

Although Turkish Sufi sheikhs did not always issue formal fatwas against Zionist land purchases, their communal teachings emphasized preserving Islamic waqf properties and protecting Muslim inhabitants. After the collapse of the Ottoman caliphate, many Sufi-affiliated networks in the Republic of Turkey maintained solidarity with Palestinian Muslims (Mandel, 1974). Contemporary Naqshbandi-Khalidi groups—whose ideological foundations can be traced back to late Ottoman Sufi activism—have been especially vocal in supporting the Palestinian cause within broader Islamist-political frameworks. In both Ottoman and modern contexts, Turkish Sufis have consistently regarded Zionist settlement in Palestine as an infringement upon Muslim sovereignty, echoing the Sultan’s original stance of opposition (Mandel, 1974).

3.7 Cyberbullying as a form of cultural deviation

In contemporary digital societies, cyberbullying has emerged as a pervasive form of cultural deviation, wherein individuals use online platforms to harass, intimidate, or humiliate others. Unlike traditional bullying—which is often constrained by physical proximity and immediate social sanctions—cyberbullying transcends geographic boundaries and permits anonymity, thereby amplifying its potential for harm. Scholars define cyberbullying as “willful and repeated harm inflicted through electronic text” (Patchin and Hinduja, 2010). The anonymity afforded by the internet can foster disinhibition, leading perpetrators to deviate from established social and moral codes that would ordinarily inhibit such behavior (Kowalski et al., 2014). In this sense, cyberbullying represents a clear break from both legal norms and cultural norms, operating as a modern analogue to historical forms of cultural deviation—albeit within a digital ecosystem.

From a sociological perspective, cyberbullying can be framed as a deviation from collective moral standards, resonant with Durkheim’s notion of “anomie,” where regulatory norms weaken and individuals drift from shared values (van Bruinessen, 2007). The digital milieu often lacks the face-to-face accountability that underpins traditional community life, weakening normative constraints and enabling individuals to forsake empathetic engagement. Moreover, the rapid virality of content can create echo chambers in which hostile behaviors are normalized or even valorized (Pizarro et al., 2022). Cyberbullying thus becomes a form of collective deviation: it not only harms individual targets but also erodes trust in online communities, undermining the social capital that digital platforms are expected to foster.

When viewed through the lens of Sufi ethics, cyberbullying starkly contradicts core principles such as compassion (raḥma), restraint (ṣabr), and the cultivation of a pure heart (qalb ṣāfī). Classical Sufi teachings emphasize that true spiritual progress involves purifying the self from malice and practicing empathy toward all beings. As Ibn Arabī (1165–1240) asserts, the hallmark of the spiritually advanced individual is “speaking softly, acting justly, and refraining from hurting others, whether by word or by deed” (Chittick, 2007). Cyberbullying, by contrast, weaponizes speech—often through demeaning language, rumor-mongering, or targeted shaming—to inflict psychological harm. Such behavior can be read as a modern manifestation of what some Sufi masters termed “nafsānī deviance”—that is, actions driven by the “lower self” (nafs) rather than the refined, compassionate self that Sufism cultivates (Schimmel, 1975). In this framework, cyberbullying is not merely a social problem but represents a moral deviation from an ethical paradigm that values spiritual cohesion and mutual care.

In addition, Weber’s concept of charismatic authority can illuminate how online figures who engage in or tacitly condone cyberbullying attain—and abuse—their influence (Weber, 1978). When an online “micro-celebrity” or influencer uses derogatory language to rally followers against a person or group, they embody a pseudo-charisma that legitimizes hostility. Followers, perceiving the influencer as an authority, may imitate or escalate cyberbullying on the influencer’s behalf, thereby reinforcing a subculture that sanctions such deviation (Weber, 1978). In contrast, Sufi masters historically used their charisma to foster unity and collective effervescence, guiding communities toward ethical solidarity (Trimingham, 1998). Consequently, while Sufi charisma aimed at social integration, the “charisma of cruelty” in cyberbullying subcultures functions as a centrifugal force, splintering digital communities and widening moral rifts. To take Weber further, we see that once cyberbullying tactics gain a following, they become routinized into standard platform behavior—memes, coordinated harassment campaigns, and “pile-on” threads—making it difficult to dismantle entrenched online norms. Empirically, this is evident in 2023 platform audits showing that hashtag-driven harassment cycles repeatedly reinstate patterns of abuse, despite platform-led “penalty” interventions.

Finally, from Bourdieu’s perspective on cultural capital, cyberbullying can be seen as a perverse deployment of discursive capital. In many online contexts—social media forums, comment sections, gaming chats—aggressive rhetoric can confer status or notoriety. Individuals who master the tactics of trolling may gain a twisted form of symbolic capital among certain digital subgroups (Bourdieu, 1986). This dynamic stands in direct opposition to the Sufi ideal of “embodied cultural capital,” wherein learning, humility, and spiritual wisdom accrue genuine prestige (Chittick, 2007). Cyberbullies accumulate “capital” not through constructive participation but through deviant speech acts, which ultimately degrade the moral fabric of online discourse.

Together, these perspectives show that cyberbullying is a multifaceted form of cultural deviation—one that erodes normative sanctions, subverts ethical teachings, and repurposes symbolic capital toward destructive ends. As digital platforms continue to evolve, integrating insights from Sufi ethics, sociological theory, and cultural capital frameworks will be crucial in countering this modern deviation.

4 Conclusion

By weaving together sociological theories—Durkheim’s collective effervescence, Weber’s charismatic authority, and Bourdieu’s cultural capital—this study has shown that Sufism did not merely overlay Islam onto Turkic nomadic life but intricately transformed it from within. Sufi rituals like dhikr and whirling dances built on preexisting circle-based communal practices, engendering emotional solidarity that eased the adoption of Islamic beliefs. Charismatic saints such as Khoja Aḥmad Yasawi served as bridges between Tengriist cosmologies and Sufi mysticism, their perceived miracles and ethical teachings forging supra-tribal networks that often mediated inter-clan relations and even influenced political decision-making. The acquisition of cultural capital—through Qurʾānic literacy, Sufi poetic mastery, and formal ijāzas—provided new avenues for social mobility, reshaping honor codes and leadership criteria beyond traditional notions of lineage and martial prowess. Moreover, the comparative examination of South Asian, Anatolian, and North African Sufi trajectories demonstrates that the Turkic experience reflects a widespread pattern: Sufi orders’ capacity for local adaptation allowed them to absorb indigenous symbols, repurpose rituals, and thus facilitate Islamization without erasing existing cultural landscapes. In contemporary terms, the contrast between Sufi ethical imperatives and modern deviations such as cyberbullying highlights how Sufi paradigms remain pertinent for addressing moral fragmentation in digital societies. In sum, Sufism functioned historically as a dynamic catalyst that preserved Turkic identity even as it reoriented social values, institutional arrangements, and collective consciousness toward the broader Islamic civilization. This dual process of integration and transformation underscores Sufism’s enduring legacy as both a spiritual path and a social force among Turkic nomads.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

AK: Software, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. YO: Writing – original draft. AS: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Investigation. BA: Writing – review & editing. BK: Project administration, Software, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdul Hamid, M. F., Meerangani, K. A., Suliaman, I., Md Ariffin, M. F., and Abdul Halim, A. (2021). Strengthening spiritual practices among community: dhikr activities in Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. Wawasan: Jurnal Ilmiah Agama dan Sosial Budaya 6, 77–86. doi: 10.15575/jw.v6i1.11930

Aldeen, A. S. (2024). From Sufism to hallucination: music’s journey beyond the universe. Available online at: https://medium.com/@ahmedshehap2011/from-sufism-to-hallucination-musics-journey-beyond-the-universe-484138ab9f8f (Accessed February 14, 2025).

Amitai-Preiss, R. (1999). Sufis and shamans: some remarks on the Islamization of the Mongols in the Ilkhanate. J. Econ. Soc. Hist. Orient 42, 213–237.

Bakhshandeh, E., Rahimian, H., Pirdashti, H., and Nematzadeh, G. A. (2015). Evaluation of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria on the growth and grain yield of rice (Oryza sativa L.) cropped in northern Iran. J. Appl. Microbiol. 119, 1371–1382. doi: 10.1111/jam.12938

Bichitr. (2025). Close-up of the Mughal miniature painting "Jahangir preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings", c. 1615–18. Available online at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hourglass_throne_close-up_of_the_Mughal_miniature_painting_%22Jahangir_preferring_a_Sufi_Shaikh_to_Kings%22,_c._1615–18.png (Accessed February 12, 2025).

Bourdieu, P. (1986). Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. New York, NY: Greenwood.

Bruinessen, M. V. (2007). “Sufism and the ‘modern’ in Islam” in Sufism and the ‘modern’ in Islam. eds. M. V. Bruinessen and J. D. Howell. 1st ed (London: I.B.Tauris).

Bruinessen, M. V., and Howell, J. D. (2007). “Sufism and the ‘modern’ in Islam” in Sufism and the ‘modern’ in Islam. eds. M. V. Bruinessen and J. D. Howell. 1st ed (London: I.B.Tauris).

Çakmakçi, R., Dönmez, F., Aydın, A., and Şahin, F. (2006). Growth promotion of plants by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria under greenhouse and two different field soil conditions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 38, 1482–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.09.019

Carls, P. (2025). Available online at: https://iep.utm.edu/emile-durkheim/ (Accessed December 25, 2025).

Chalcraft, J. (2017). “Popular movements in the Middle East and North Africa” in The history of social movements in global perspective: A survey. eds. S. Berger and H. Nehring (London: Palgrave Macmillan Uk).

Chittick, W. C. (1989). The Sufi path of knowledge: Ibn al-‘Arabi’s metaphysics of imagination. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Cook, M. A. (2024). Part ii the Muslim world from the eleventh century to the eighteenth.Part 2. A history of the Muslim world. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Eaton, R. M. (1978). The rise of Islam and the Bengal frontier, 1204–1760. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Eaton, R. M. (1993). The rise of Islam and the Bengal frontier, 1204–1760. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Foltz, R. (2010). Religions of the silk road: Premodern patterns of globalization. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gabitov, H. T. (2012). Kazakh culture in the context of islamic and Turkic civilizations. Available online at: https://pps.kaznu.kz/kz/Main/FileShow2/124447/110/359/1528/0/2019/2 (Accessed February 2, 2025).

Haselby, S. (2024). Indomitable Sufis. Available online at: https://aeon.co/essays/sufi-transitions-between-mullahs-and-sufis-in-afghanistan (Accessed February 2, 2025).

Hill, M. (2009). The spread of Islam in West Africa: containment, mixing, and reform from the eighth to the twentieth century. Available online at: https://spice.fsi.stanford.edu/docs/the_spread_of_islam_in_west_africa_containment_mixing_and_reform_from_the_eighth_to_the_twentieth_century (Accessed March 2, 2025).

Huang, X. (2019). Understanding Bourdieu - cultural capital and habitus. Rev. Eur. Stud. 11:45. doi: 10.5539/res.v11n3p45

İnalcık, H., and Quataert, D. (1990). An ottoman empire: A short history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jafri, S. Z. H. (2006). The Islamic path: Sufism, politics, and Society in India. New Delhi: Konrad Adenauer Foundation.

Karamustafa, A. T. (2007). God’s unruly friends: Dervish groups in the Islamic later middle period, 1200–1550. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press.

Khakimov, A. (2005). The art of the northern regions of Central Asia, (History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. VI). Paris, France: UNESCO Publishing.

Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N., and Lattanner, M. R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: a critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychol. Bull. 140, 1073–1137. doi: 10.1037/a0035618

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA.

Mahatma, M., and Saari, Z. (2021). Embodied religious belief: the experience of Syahadatain Sufi order in Indonesia. Wawasan: Jurnal Ilmiah Agama dan Sosial Budaya 6, 87–100. doi: 10.15575/jw.v6i1.13462

Mandel, N. J. (1974). Ottoman policy and restrictions on Jewish settlement in Palestine: 1881-1908: part I. Middle East. Stud. 10, 312–332. doi: 10.1080/00263207408700278

Miles, M. B., and Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA.

Nizami, K. A. (1998). Popular movements, religious trends and Sufi influence on the masses in the post-Abbasid period. Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000112870 (Accessed March 3, 2025).

Nowicka, E. (2014). Siberian circle dances: the new and the old communitas. Pol. Sociol. Rev. 184, 253–274. Available online at: https://polish-sociological-review.eu/Siberian-Circle-Dances-the-New-and-the-Old-Communitas,119647,0,2.html

Patchin, J. W., and Hinduja, S. (2010). Cyberbullying and self-esteem. J. Sch. Health 80, 614–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00548.x

Pizarro, J. J., Zumeta, L. N., Bouchat, P., Włodarczyk, A., Rimé, B., Basabe, N., et al. (2022). Emotional processes, collective behavior, and social movements: a meta-analytic review of collective effervescence outcomes during collective gatherings and demonstrations. Front. Psychol. 13:974683. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.974683

Ragin, C. C. (1987). The comparative method: Moving beyond qualitative and quantitative strategies. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Rahman, A. A. (2009). Middle class and Sufism: The case study of the Sammaniyya order branch of Shaikh Al Bur'ai. Khartoum, Sudan: University of Khartoum.

Satybaldiev, D., Attokurova, T. A., Attokurova, M., and Seitimbetova, A. (2024). Nomadic governments of Central Asia from ancient times to the middle ages. Open J. Soc. Sci. 12, 684–704. doi: 10.4236/jss.2024.1212043

Schimmel, A. (1975). Mystical dimensions of Islam. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Seesemann, R. (2008). Sufis and saints' bodies. Mysticism, corporeality, and sacred power in Islam. By Scott Kugle. J. Am. Acad. Relig. 76, 514–521. doi: 10.1093/jaarel/lfn029

Serdar, K. M. (2013). Sufi whirling in iraqi kurdistan in Family mall. Available online at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sufi_whirling_in_Erbil.jpg (Accessed April 5, 2025).

Shahi, D. (2019). Introducing Sufism to international relations theory: a preliminary inquiry into epistemological, ontological, and methodological pathways. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 25, 250–275. doi: 10.1177/1354066117751592

Siddiqa, A. (2018). Sinners, saints, soldiers of god: has Sufism failed to counter radicalism? Available online at: https://thefridaytimes.com/16-Feb-2018/sinners-saints-soldiers-of-god-has-sufism-failed-to-counter-radicalism (accessed February 16, 2018).

Temirbayev, T., and Temirbayeva, T. (2021). Pilgrimage in Kazakhstan: the graves of the Sufi sheikhs. Eurasian J. Religious Stu. 27, 50–58. doi: 10.26577//ejrs.2021.v27.i3.r6

van Bruinessen, M. (2007). Les pratiques religieuses dans le monde turco-iranien: changements et continuités. Cahiers d'études sur la Méditerranée orientale et le monde turco-iranien 40, 101–121. doi: 10.4000/cemoti.1769

Watson-Jones, R. E., and Legare, C. H. (2018). The social functions of shamanism. Behav. Brain Sci. 41:e88. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X17002199

Weekes, U. (2018). A closer look at Mughal Emperor Jahangir depicted on the hourglass throne. Available online at: https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/blog/closer-look-mughal-emperor-jahangir-depicted-hourglass-throne/ (Accessed March 17, 2025).

Keywords: cultural deviation, Sufism, charismatic authority, cultural capital, identity formation

Citation: Kurmanbek A, Osserbayev Y, Shagyrbay A, Azhimov B and Kossalbayev BD (2025) The roots of the cultural deviation of Sufism in the ancient Turkic nomadic culture. Front. Commun. 10:1591725. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1591725

Edited by:

Busro Busro, State Islamic University Sunan Gunung Djati, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Mehmet Ali Yolcu, Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, TürkiyeDesmadi Saharuddin, Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University Jakarta, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Kurmanbek, Osserbayev, Shagyrbay, Azhimov and Kossalbayev. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yeldos Osserbayev, ZWxkb3MuY3NAbWFpbC5ydQ== Bekzhan D. Kossalbayev, a29zc2FsYmF5ZXYuYmVremhhbkBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Akaidar Kurmanbek

Akaidar Kurmanbek Yeldos Osserbayev

Yeldos Osserbayev Almasbek Shagyrbay

Almasbek Shagyrbay Bekzhan Azhimov

Bekzhan Azhimov Bekzhan D. Kossalbayev

Bekzhan D. Kossalbayev