- 1Paramadina Graduate School of Communication, Universitas Paramadina, Jakarta, Indonesia

- 2Paramadina Graduate School of Islamic Studies, Universitas Paramadina, Jakarta, Indonesia

This study explores the case of a reformed former terrorist convict who, through self-initiated efforts, established media-based Preventing/Countering Violent Extremism (P/CVE) initiatives utilizing his YouTube channel. Amidst the ongoing contest within the online public media sphere to counter harmful extremist content, the voices of credible individuals become paramount. This research investigates how Sofyan Tsauri adopted and utilized social media to contribute to P/CVE efforts and engage in civic participation. Consequently, this study employs the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), a socio-technical approach underutilized in media-based P/CVE research. While UTAUT studies are predominantly quantitative, this research adopts a qualitative approach to gain deeper insights, employing a single intrinsic case study design focused on Sofyan Tsauri, whose unique experiences and actions are particularly suited to addressing the research question. Data collection was conducted through semi-structured, in-depth interviews and document analysis. Interview transcripts were analyzed using Nvivo software, employing deductive coding based on UTAUT dimensions. The findings confirm that performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence are associated with the motivation to adopt YouTube, with performance expectancy as the dominant driver. However, this research reveals crucial deviations from the original UTAUT framework. Firstly, this study demonstrates that the former convict’s past experience with digital media enhances his performance expectancy. This diverges from the UTAUT model, which posits that prior experience would enhance effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions. Secondly, this research also identifies a novel dimension, the “restorative motive,” an intrinsic drive within the former convict to atone for past transgressions by engaging ardently to counter and provide alternative narratives to harmful and extremist content, including online. Therefore, these findings offer more nuanced insights into adopting individual-level digital media technology, enriching the theoretical discourse beyond traditional UTAUT applications. By acknowledging the restorative motives in supporting former extremists’ use of social media for P/CVE, governments, and civil society, organizations can enhance these individuals’ capacity to provide alternative and counter-narratives to mitigate online radicalization. This study suggests avenues for future research to deepen our understanding of digital communication practices in fostering a safer and more peaceful world.

1 Introduction

Social media and the internet, in general, have become pivotal domains for the spread of various forms of online radicalization and violent extremism, such as white supremacism (e.g., Minter, 2021), neo-Nazism (e.g., Miller, 2022), and Islamic extremism (e.g., Monaci, 2017). These groups have skilfully utilized these platforms to disseminate propaganda, recruit members, and establish virtual communities reinforcing radical ideas (Adigwe et al., 2024; Winter et al., 2020; Lawrence and Robertson, 2023). To counter this, stakeholders—albeit with varying levels of commitment—have undertaken media-based Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism (P/CVE) initiatives, achieving differing degrees of success. Social media platforms, for example, have struggled to effectively regulate and moderate content on their networks (Borelli, 2023; Thorley and Saltman, 2023). Meanwhile, governments and state institutions are responsible for developing policies and frameworks to address these threats, while civil society organizations (CSOs) and grassroots movements play a critical part in strengthening community resilience (Amit et al., 2021; Barton and Vergani, 2022; Sila and Fealy, 2022).

An important component of these activities is the involvement of former combatants, terrorists, and violent extremists (hereafter referred to as “the formers”) in P/CVE initiatives, including media-based initiatives (Tapley and Clubb, 2019). Having experienced such extremist phases and subsequently renounced their radical beliefs, the formers are often regarded as credible voices with a unique role in influencing both the broader society and radicalized groups (Koehler et al., 2023; Ismail, 2021). This article focuses on the work of Sofyan Tsauri, an Indonesian police officer who became radicalized and was convicted of offenses including the accumulation of arms and leading military training for planned terror attacks. Sofyan was loosely affiliated with Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), an Indonesia-based terrorist organization that operates and aspires to establish an Islamic state across Southeast Asia. Jemaah Islamiyah was responsible for several bomb attacks in the first decade of the 2000s, including the 2002 Bali bombing, which killed hundreds (Solahudin, 2013). Following his release, Sofyan established the “Sofyan Tsauri Channel,” a dedicated YouTube channel that disseminates counter-narratives rooted in his personal experiences and insights to engage audiences vulnerable to radicalization. Notably, no other formers in Indonesia are as actively and independently engaged in media-based P/CVE as Sofyan.

Through a social learning theory lens, Nasution et al. (2021) have studied Sofyan’s process of deradicalization since in prison. This study shows how Sofyan disengaged from and quit the extremism movement, which later led to his involvement in P/CVE initiatives, both those conducted by the state and his own efforts. Meanwhile, Muhyiddin and Priyanto (2023) emphasize the importance of giving voice to the former terrorists, such as Sofyan, in combating radicalization. By pointing to several of Sofyan’s video posts on YouTube, and viewed from the subaltern perspective, they demonstrate how a former terrorist becomes a subject and exercises his own agency. This current research, however, investigates further by focusing on why Sofyan accepts and uses new technologies, such as YouTube, as the center of his P/CVE media initiatives. Therefore, this study applies the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) as a theoretical framework to examine the factors influencing technology adoption, including performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, and prior experience (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Utilizing UTAUT, this research explores how Sofyan adopts and leverages digital platforms to facilitate his civic participation and achieve his P/CVE objectives.

This study contributes to the scholarly discourse on media-based P/CVE in three significant ways. First, it underscores the role of formers as credible actors in developing and delivering counter-narratives on social media. In Indonesia, while some formers, such as those involved in organizations like DeBintal (Noor, 2024) and Lingkar Perdamaian (Evi et al., 2020) initiatives, participate in anti-radicalism efforts, Sofyan stands out for his persistent and independent use of social media. Previous studies have predominantly examined the involvement of formers in state-led or CSO-led P/CVE programs (Tapley and Clubb, 2019; Schewe and Koehler, 2021; Wallace, 2023). Second, the application of UTAUT provides unique insights into how the personal experiences of formers influence their adoption and use of digital media. Earlier research has primarily focused on the effectiveness and ethical concerns (Papatheodorou, 2023) surrounding formers’ participation in P/CVE programs rather than their motivations and methods for engaging with media independently (Wildan, 2022; Aditya et al., 2019). Finally, this study addresses a critical gap in the literature by adopting a sociotechnical approach to the study of media use in deradicalization research (Risius et al., 2024). Previous research has largely overlooked the interplay between technological affordances, individual motivations, and institutional dynamics in tackling online extremism. By focusing on this nexus, the study enriches our understanding of how formers like Sofyan navigate and utilize digital platforms to counter radicalization and promote resilience in the digital age.

2 Literature review

2.1 P/CVE media initiatives: the battleground of the online public sphere

New media has become a critical arena for groups advocating violent extremism, serving as a tool for spreading propaganda, inciting hate, recruiting followers, and even for fundraising and other logistical purposes (Adigwe et al., 2024; Winter et al., 2020). Organizations like ISIS, for instance, have effectively used a variety of media channels (Awan, 2017), including magazines (Novenario, 2016), Telegram (Krona, 2020), Twitter (Badawy and Ferrara, 2018) and more, to further their agenda. Moreover, Monaci (2017) shows that ISIS has successfully employed a transmedia storytelling strategy in which content from various platforms was integrated into a few carefully selected narratives. This strategy has enabled ISIS’s media propaganda to attract new recruits across Southeast Asia, including Indonesia (Arifin, 2017; Moir, 2017; Nuraniyah, 2019). Similarly, Huda et al. (2021) highlight how online media platforms have facilitated youth radicalization in Indonesia, including young women (Nasir, 2019), and with some cases of self-radicalization leading to lone-wolf terrorist attacks (Riyanta, 2022). Besides launching propaganda and recruitment efforts, online activism has even been used by some Indonesian extremist groups to fight among themselves (IPAC, 2015).

Although cyberspace is flooded with extremist content, research on violent extremism and youth in various parts of the world does not show a conclusive conclusion that social media is the sole cause of radicalism (Alava et al., 2017). There are complex, interrelated factors that can lead someone to become a violent extremist. This fact does not make online extremism any less important because it is proven that extremist organizations are actively sophisticated and quickly adopting new media to advance their agendas free from their geographical and temporal limitations (Adigwe et al., 2024).

To answer this complex challenge, social media technology platforms, governments, and CSOs, both collaboratively (Macdonald et al., 2023) and independently, are undertaking media-related initiatives to counter and mitigate the influence of online violent extremism on society. As counterterrorism actors (Borelli, 2023), social media platforms have community guidelines and policies to prevent extremist material on their sites. Social media platforms are also trying to use new approaches applied in their algorithms to detect, downgrade, or take down harmful, violent extremist content (Thorley and Saltman, 2023; Saltman et al., 2023). However, Williams et al. (2023) found that 48.44% of users reported being exposed to extremist material on their social media platforms, suggesting a significant failure on the part of prominent social media companies to effectively reduce users’ exposure to extremist content, despite their public assurances regarding the removal of such harmful material. Furthermore, they are not consistently applying their own policies, which further undermines their goal of providing a safe environment for all users.

Since the media is a powerful tool for violent extremist groups to spread their message to the public, states and civil society organizations are naturally adopting media and communication technology for countering terrorism (CT) to P/CVE programs. Actions that can be taken include hostile measures such as removing, blocking, or limiting the circulation of content that leads to violent extremism on social media platforms. The effectiveness of this strategy certainly requires good coordination between platforms and states, along with their law enforcers and counterterrorism bodies (Macdonald et al., 2023). However, governments encounter substantial challenges in developing regulations to address harmful content online. One of the primary difficulties arises from the fact that the majority of social media platforms are based in the United States and operate under legal frameworks that strongly emphasize freedom of speech. This emphasis often affords these platforms considerable immunity from liability for user-generated content, effectively shifting the responsibility for such content onto individual users (Yar, 2018). Although some countries have introduced legislation aimed at strengthening state authority over content regulation, the effectiveness of these measures is frequently constrained by limited institutional capacity to implement and enforce a secure online environment (Neudert, 2023).

Another strategy is positive measures, emphasizing the production and dissemination of counter or alternative narrative content, enhancing community resilience, and promoting critical thinking. Besides tech companies and states, CSOs and even individuals are more likely to implement this strategy in their P/CVE initiatives (Tio and Kruber, 2022). Media-based P/CVE programs operate in diverse settings, from developed countries such as the Netherlands (Eerten et al., 2017) and Canada (Waldman and Verga, 2016) to developing regions such as East Africa (Avis, 2016), ASEAN (Shah et al., 2022), Pakistan (Haider, 2022), and Bangladesh (Amit et al., 2021). In Indonesia, the government and the National Counterterrorism Agency (BNPT) also conduct media-related P/CVE, among other programs. With regards to the hostile measures, the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (MOCI) of Indonesia handled 5,731 pieces of content related to radicalism, extremism, and terrorism in the digital space from July 7, 2023, to March 21, 2024 (Rochman, 2024). On the positive measures, however, BNPT, through its Duta Damai program, recruits hundreds of youths across the country to become ambassadors of peace, one of whose tasks is to create positive content on social media (Effendi et al., 2022). Furthermore, BNPT manages a YouTube account that is quite active in uploading video content, including interviews with former terrorists or convicts who have abandoned their extremist beliefs. This YouTube channel is called BNPT TV, and when this article was written, it contained 377 videos (BNPT, n.d.). Meanwhile, some Indonesian civil society organizations (CSOs) have also adopted media-based strategies to combat radicalism—for example, large organizations like Nahdlatul Ulama leverage film and social media (Schmidt, 2021). Additionally, CSOs such as Kreasi Prasasti Perdamaian (Ismail, 2021) and Peace Generation (Hakim et al., 2019) excel in utilizing multi-platform media to implement their P/CVE programs effectively.

2.2 P/CVE initiatives involving the formers

Over the past decade, former extremists have increasingly participated in deradicalization initiatives and preventative measures within P/CVE frameworks across various countries (Tapley and Clubb, 2019). Having been directly involved in extremist activities, often leading to incarceration, and subsequently disengaging from such ideas, their lived experiences offer invaluable insights into the manifestations and dynamics of extremism and terrorism (Hwang, 2018). However, concerns regarding ethics (Papatheodorou, 2023), credibility, and public perception of involving former extremists in such initiatives remain significant (Koehler et al., 2023). On the other hand, the expanding body of research highlights the significant value of integrating the perspectives of former extremists into academic and policy discussions on terrorism and extremism (Scrivens et al., 2020). Their unique insights contribute to a deeper understanding of radicalization, disengagement, and effective counter-extremism strategies.

In the USA, for example, the Life After Hate organization was founded by former members of extreme organizations, especially the White supremacist group, who also carry out P/CVE activities (Wallace, 2023; Wilson, 2017). In Germany, the involvement of former extremists in PVE programs within schools has been established for quite some time. Content analysis of speeches delivered by formers in these settings indicates that much of the material takes the form of biographical narratives. However, given the diverse motivations of these individuals in participating in P/CVE activities—and the fact that some formers may not yet be fully deradicalized—it is crucial to adopt a nuanced perspective on their role, mainly when the target audience comprises children and adolescents (Gansewig and Walsh, 2021). Meanwhile, based on a survey of 1,931 Danish youth respondents, the benefits of involving former extremists in P/CVE programs outweigh the potential risks. These initiatives have effectively reduced the perceived legitimacy of political violence among young people in Denmark (Parker and Lindekilde, 2020).

In Indonesia, some former extremists have actively participated in efforts related to deradicalization, disengagement, counterterrorism, and P/CVE (Aditya et al., 2019; Noor, 2024; Widya et al., 2020; Wildan, 2022). Aditya et al. (2019) provide preliminary evidence indicating that counter-narratives created by these individuals can effectively support disengagement programs for radicalized individuals, emphasizing the importance of involving them further in such initiatives. According to Wildan (2022), these formers engage in three primary categories of activities: (1) prison-based programs, (2) economic empowerment initiatives, and (3) youth-focused programs. Among these, the youth-focused programs are deemed the most successful.

Many individuals collaborate with the National Counterterrorism Agency (BNPT) or Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) specializing in P/CVE. Additionally, some have established their own CSOs to advance deradicalization and P/CVE efforts, including Yayasan DeBintal (Noor, 2024) and Yayasan Lingkar Perdamaian (Asrori et al., 2020; Evi et al., 2020). A notable example of a media-focused P/CVE initiative is Kreasi Prasasti Perdamaian (KPP), which operates the community platform ruangobrol.id. This platform features content and articles authored by former extremists and showcases documentary films depicting their life experiences (Ismail, 2021). Furthermore, Sofyan Tsauri has launched a YouTube channel offering various counter-narrative content to advance P/CVE objectives (Muhyiddin and Priyanto, 2023; Nasution et al., 2021).

2.3 Unified theory of adoption and uses of technology

The UTAUT model is one of the most powerful theories that examines user acceptability and intention to embrace new technologies. It has emerged as one of the most comprehensive and advanced frameworks for understanding technology acceptance, integrating the most effective constructs from earlier theories and models (Momani, 2020). This model was developed by Venkatesh et al. (2003) by consolidating eight existing information technology acceptance and adoption models originating from three research streams – i.e., social psychology, information system management, and behavioral psychology. From the socio-psychological research stream, the theories included in the UTAUT model were the Theory of Reasoned Action, the Theory of Planned Behavior, and the Social Cognitive Theory. The information system management research stream was elaborated by the Technology Acceptance Model, the combined Technological Acceptance Model and Theory of Planned Behavior model (C-TAM-TPB), the Innovation Diffusion Theory, and the model of personal computer utilization. Lastly, the Motivational Model represents the behavioral psychology research stream, implying that user motives can be used to investigate technology adoption and usage behavior (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

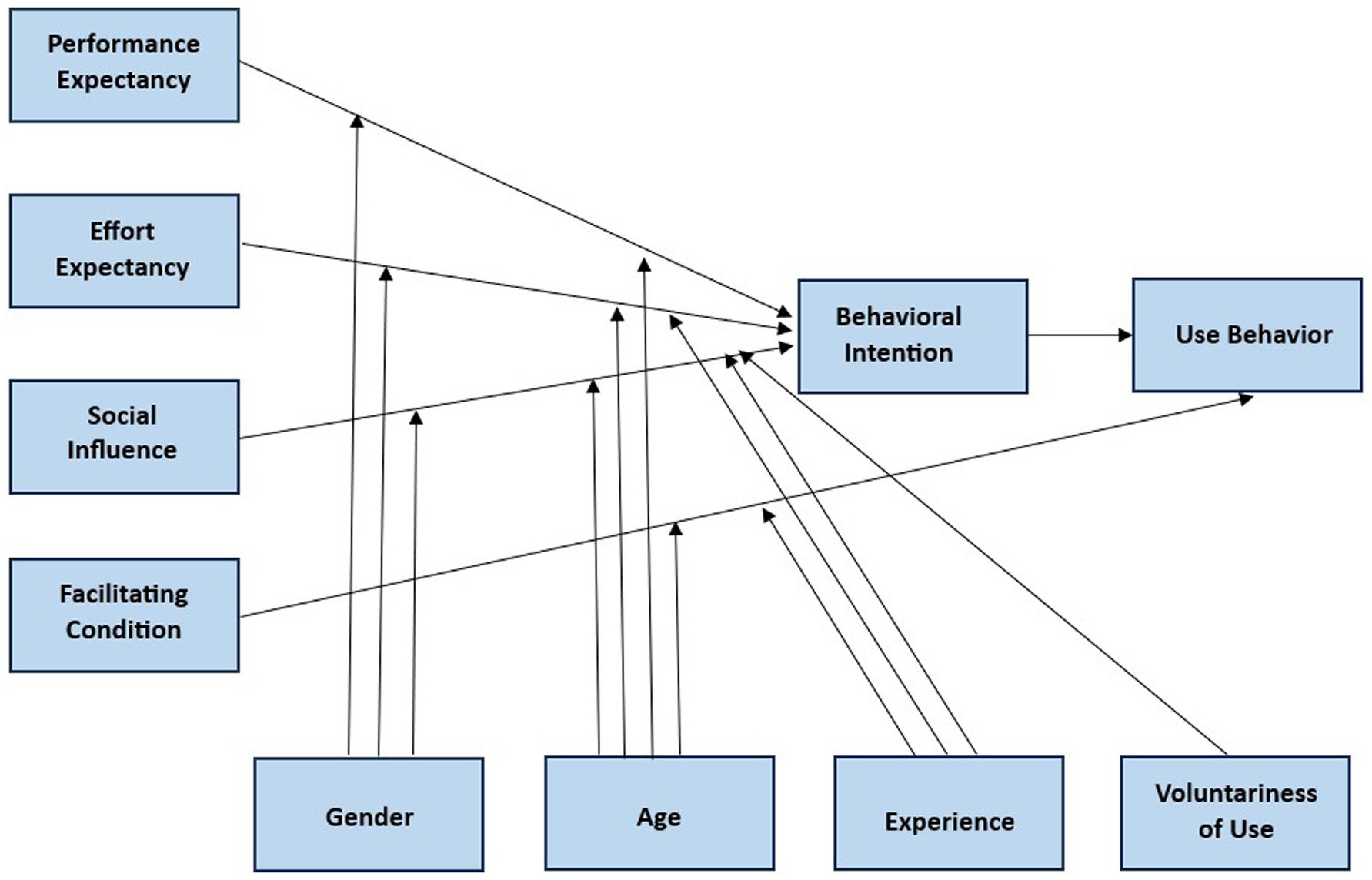

Referring to these earlier models, Venkatesh et al. (2003) developed four important constructs for the UTAUT model: performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions. The first three constructs relate to the behavioral intention, while the last construct (facilitating conditions) refers to the usage behavior. Here are the definitions of each of those constructs (Venkatesh et al., 2003):

Performance expectancy – the degree to which an individual believes that using the system will help him/her to attain gains in job performance (p. 447).

Effort expectancy – the degree of ease associated with the use of the system (p. 450).

Social influence – the degree to which an individual perceives that important others believe he/she should use the new system (p. 451).

Facilitating conditions – the degree to which an individual believes that an organization and technical infrastructure exists to support the use of the system (p. 453).

The relationship was moderated by gender, age, experience, and voluntariness of use. Of all moderating variables, only age moderates the effect of all four constructs. Meanwhile, gender influences the relationships between effort expectancy, performance expectancy, and social influence. Experience moderates the relationships between effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions. Lastly, the voluntariness of use has a moderate effect on the relationship between social influence and behavioral intention. Figure 1 shows the complete research model offered by UTAUT.

Figure 1. The UTAUT research model. Source: Venkatesh et al. (2003, p. 447).

The UTAUT model can explain 70% of the variance in the intention and use of information technology, a validity surpassing previous models (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Over time, this model has been tested in various geographical contexts to examine its generalizability and the role of culture in technology adoption. The study confirms that the UTAUT model’s constructs maintain their significance, irrespective of cultural and geographical variations (Marikyan and Papagiannnidis, 2023). Furthermore, the UTAUT model was intentionally designed with minimal complexity, characterized by a limited number of constructs and moderating variables. This simplicity enhances its applicability and comprehensibility, particularly in studies examining the acceptance of new technologies or information systems (Momani, 2020).

UTAUT model has been employed to investigate technology acceptance across various sectors. Keyword analysis results suggest that the model has been primarily used for technology adoption and acceptance research in e-government, e-banking, e-learning, and e-commerce (Williams et al., 2015). As one of the most popular social media platforms, YouTube has become a prominent topic among UTAUT researchers. However, most recent studies focus on adopting YouTube in various educational and teaching contexts (Guillén-Gámez et al., 2024; Ishak et al., 2022; Nguyen and Le, 2023; Yus and Jayadi, 2022). However, one area of research that has yet to be explored using the UTAUT framework is the study of online extremism and radicalization. Risius et al. (2024) argue that a sociotechnical approach, such as UTAUT, is essential for understanding the dynamics of social and technical components in information technology to mitigate online extremism.

Bibliometric studies show that research using UTAUT as an analytical, theoretical framework is overwhelmingly quantitative (Marikyan and Papagiannnidis, 2023; Venkatesh et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2022; Williams et al., 2015; Xue et al., 2024). However, Xue et al. (2024) suggest that research on the UTAUT would benefit from a greater emphasis on qualitative methodologies, enabling a deeper and more nuanced understanding of individual experiences and perceptions. This recommendation has been acknowledged by UTAUT researchers, who have begun incorporating qualitative approaches into their studies. Such qualitative studies include, for example, the use of health and telemedicine technology (Jayaseelan et al., 2020; Limna et al., 2023; Nymberg et al., 2024), communication technology adoption by older adults (Bixter et al., 2019), new technologies such as ChatGPT (Menon and Shilpa, 2023) and mobile video on cell phones (Lee, 2011), library technology (Rempel and Mellinger, 2015), banking services technology (Bouteraa et al., 2023; Gharaibeh et al., 2018), and social media interface design (Gurgun et al., 2024).

3 Methods

This research employs a descriptive qualitative approach to explore how a former terrorist utilizes social media, particularly YouTube, to counter violent extremism online. This study focuses on Sofyan Tsauri, a former terrorist whose experiences and actions are uniquely suited to addressing the research question. While other former convicted terrorists in Indonesia are involved in counter-narrative and deradicalization programs, Sofyan is notably the most active and consistent among his peers in creating social media content, primarily through his YouTube channel, to carry out his P/CVE (Preventing/Countering Violent Extremism) and peacebuilding initiatives. His public activities and sustained engagement in CVE initiatives offer a unique insight into the perspectives of individuals with such backgrounds. This characteristic makes him an unparalleled source of data for understanding the complexities of CVE and the use of online platforms within this context. Furthermore, Sofyan’s lifelong relationship with the media—before, during, and after his radicalization—serves as an exceptional example of media’s inherent embeddedness in his personal journey.

Therefore, this research constitutes an intrinsic case study (Creswell and Poth, 2018), as the case under investigation presents a unique and rare situation warranting detailed exploration. Sofyan was selected not for his representativeness of a larger population, but due to the distinctiveness of his case. Conversely, a limitation of this research is its generalizability, stemming from its reliance on a single informant. Data collection was conducted through semi-structured, in-depth interviews and document analysis. The in-depth interviews were conducted twice at Sofyan’s modest/makeshift studio, which also serves as his home. We obtained permission to record the interview and consent to mention his full name in the report. We conduct the member checking or the informant validation by giving Sofyan the transcript of the interviews so he can check for accuracy and resonance with his experiences. The interview transcript was then analyzed using Nvivo software, with deductive coding and themes according to UTAUT dimensions. Parts that do not fall into the existing dimensions were coded differently to see the possibility of suggestions to expand or modify UTAUT.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Sofyan Tsauri: from a convict terrorist to an “immunizer”

Sofyan Tsauri, a former Indonesian police officer, was convicted and imprisoned for terrorism charges for ten years in 2010. Sofyan served almost six years in prison and was released in late 2015 after receiving sentence reductions. He was one of the key figures in establishing a military training camp in Aceh in early 2010. As a police officer before deserting in 2008, Sofyan had access to illegally purchase firearms and ammunition. He claimed to have amassed around 50 firearms (such as M-16 s and AK-47 s) and fifty-thousand rounds of ammunition. In the Indonesian context, the Aceh military camp represents a significant milestone, as it became a unifying ground where almost all competing and rival jihadist factions sent representatives for military training (International Crisis Group, 2010).

According to Sofyan, his time in prison allowed him to reflect on his actions and the broader jihadist movement deeply. He experienced disillusionment due to intense factionalism within the jihadist circles, particularly from more extreme groups associated with ISIS. Sofyan was aligned with Al-Qaeda networks in Indonesia, and the global hostility between ISIS and Al-Qaeda extended into Indonesian prisons. Under the pseudonym Abu Jihad al-Indunisy, Sofyan authored several tracts while in prison in early 2015, which were published on Muqawommah.net, the website he managed from inside the prison, together with some of his like-minded convict terrorists. These writings strongly criticized Indonesian extremists affiliated with ISIS and what he perceived as deviant Islamic practices. His publications were met with bitter rebuttals from websites associated with the ISIS-affiliated groups in Indonesia, resulting in an “online battle” between both camps’ factions in the country (IPAC, 2015). Sofyan claimed that his writings have prevented many Indonesians from joining ISIS.

While primarily aimed at curbing ISIS’s influence in Indonesia, Sofyan stated that the Muqawommah.net initiative was not intended as an entirely counter-extremism project. Notably, this endeavor emerged from their sympathies with Al-Qaeda. His engagement, however, significantly intensified his introspective process and amplified his disillusionment with violent jihadist ideas. “I began to think that perhaps the correct path of da’wah [Islamic proselytization] is what Nahdlatul Ulama is doing,” he recalled (personal communication, August 13, 2024). This reflection points to Sofyan’s formative background, having studied in a traditional pesantren (Islamic boarding school) within the environment of Nahdlatul Ulama, a major Indonesian Islamic organization comprising more than 40 million members.

Sofyan’s trajectory illustrates that push factors, such as disillusionment with leadership, internal factional disputes, and similar grievances, were the primary catalysts for his deradicalization. Conversely, pull factors, including exposure to state-sponsored deradicalization programs and interventions from more moderate entities, played a lesser role in his process. Indeed, Sofyan’s experience is not unique. Research conducted by Altier et al. (2017) examining the autobiographies of 87 former terrorists from 42 diverse groups (encompassing religious, far-right, far-left extremist, separatist, and nationalist movements) similarly demonstrated that push factors were the predominant drivers of their disengagement from extremist organizations. Upon his release from prison, Sofyan became actively involved in various deradicalization initiatives through personal efforts and in collaboration with state institutions and civil society organizations (CSOs). He served as the coordinator for former terrorist convicts who had disengaged from extremist ideas and were in the process of reintegrating into society. In August 2020, he launched a YouTube channel titled “Sofyan Tsauri Channel”,1 which has since uploaded 480 videos and garnered 17.4 k subscribers. Three videos have garnered over 100,000 views. Two of these videos (299 k and 140 k views) feature Sofyan bringing a group of former terrorists to meet and attend a religious lecture delivered by Gus Baha, a popular Islamic scholar with a traditional Nahdlatul Ulama background (Rohmatulloh et al., 2022). The third video (151 k views) is an interview between Sofyan and Ali Imron, a convicted perpetrator of the Bali Bombing I, who is serving a life sentence and has since expressed remorse for his acts of terrorism. Approximately 15 videos have received between 10,000 and 50,000 views, while most have garnered fewer than 10,000 views. Nevertheless, it is arguably the most active YouTube platform initiated by a former terrorist in Indonesia (Muhyiddin and Priyanto, 2023; Nasution et al., 2021), making it a unique and significant contribution to counter-extremism efforts in the country.

Considering Sofyan’s initiatives, the three categories of roles for former extremists in P/CVE efforts proposed by Wildan (2022) need to be expanded. In addition to prison-based programs, economic empowerment initiatives, and youth-focused programs, former extremists also play a role in launching media initiatives. Utilizing Tio and Kruber’s (2022) framework on P/CVE communication approaches, Sofyan’s YouTube channel offers (a) a positive alternative to unite people around a vision of a cohesive society, (b) counter-narratives by responding to and refuting extremist narratives and (c) encourages critical thinking by facilitating dialogue on issues of radicalism.

4.2 Performance expectancy

In the context of media-based P/CVE efforts undertaken by Sofyan, performance expectancy refers to the extent to which he perceives that utilizing social media, particularly YouTube, will significantly enhance his effectiveness in immunizing society through the delivery of anti-radicalism messages. Sofyan firmly believes that social media is crucial for achieving his objectives. Furthermore, he recognizes that YouTube enables him to reach an audience that, while not large, is geographically dispersed. Compared to other dimensions of the UTAUT framework, performance expectancy emerges as the primary factor driving Sofyan’s adoption of YouTube to counter online radicalism. This study corroborates prior bibliometric research (e.g., Venkatesh et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2022), which highlights performance expectancy as a significant determinant of the intention to adopt technology.

For Sofyan, this social media platform expands the reach of his efforts to help prevent the growth of extremism in Indonesia. He states that.

…we (former terrorism convicts) metaphorically are like a vaccine made from a tamed virus, as we can recognize the same disease. This means we serve as a form of immunity for society. Only former terrorists truly understand the genealogy and growth of extremism. We were the ones who started it, so we must also be the ones to end it. (personal communication, September 22, 2024)

Sofyan emphasizes that individuals like him bear a moral responsibility to counterbalance the content on social media with messages that challenge the more abundant extremist narratives online. As such, he views social media as an effective tool for reaching audiences who have not yet been significantly exposed to such harmful content. Due to their prior involvement in acts of terrorism, these former individuals, according to him, have access to other former extremists and serve as credible voices for delivering anti-extremism content. Sofyan emphasized that these former extremists possess greater legitimacy in conveying peace messages, a finding corroborated by previous studies examining the role of former extremists in P/CVE efforts in Germany (Gansewig and Walsh, 2021), Denmark (Parker and Lindekilde, 2020), and the US (Wallace, 2023).

Furthermore, Sofyan emphasized the importance of his prior experience in his decision to adopt YouTube. He referred to the “online battle” he engaged in while still in prison, stating:

I was one of the founders of Al-Muqowamah.net. We actively countered the narratives of ISIS groups because, at that time, pro-ISIS posts were flooding the internet. I was then affiliated with (a group affiliated with) Al-Qaeda. Our efforts were successful as we thwarted many individuals who intended to travel to Syria. (personal communication, August 13, 2024)

This finding diverges from the UTAUT model proposed by Venkatesh et al. (2003), which posits that prior experience moderates the relationship between the other three factors (effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions) and the intention to adopt and use technology behavior. In Sofyan’s case, his decision to adopt YouTube was rooted in his belief that his performance in “immunizing” society could be significantly enhanced by leveraging his past experience, which he deemed effective.

4.3 Effort expectancy

Effort expectancy is defined as the degree of ease associated with the use of the system (Venkatesh et al., 2003). According to Sofyan, producing and uploading videos to YouTube is not challenging for him and his assistant. He said:

We are self-taught. It’s simple to create content on YouTube. … a few hours later, it can be uploaded…[even] sometimes we create live content. So, it’s not difficult at all. This technology is very easy and makes it easy. (personal communication, August 13, 2024)

In other words, the technological affordances offered by YouTube to content creators have provided Sofyan with the facility to manage his channel. Sofyan did not anticipate that he would exert significant effort in this regard.

However, according to Sofyan, two non-technical significant challenges associated with using the YouTube platform require considerable effort. First, for a channel to grow and engage its audience effectively, it must produce and consistently upload videos, presenting a challenge for Sofyan, who operates with a largely self-funded model. For instance, inviting former terrorists as guests for interviews entails costs, such as honorariums, which, at the very least, must cover their transportation expenses. According to Sofyan,

The necessity to provide remuneration for interview participants, at minimum covering return transportation expenses such as fuel costs, presents a significant financial constraint that often limits our video production. (personal communication, August 13, 2024)

Second, YouTube’s algorithm compels Sofyan to exercise caution in the wording and tone of his videos. Given the sensitive nature of his content, which could be misinterpreted as promoting terrorism or radicalism, his videos risk being flagged for violating community standards.

We must ensure YouTube’s algorithms do not flag our content as dangerous. We mean well, but it’d be a massive screw-up if we get accused of promoting violence. It’s happened before; one of our videos got marked ‘red’ and had to be taken down. (personal communication, August 13, 2024)

Sofyan also mentioned that one of his videos was banned from being uploaded on YouTube because it reused content intended solely as an illustration for critique and to counter its dissemination. He noted that using “terrorist” or “terrorism” in video titles or descriptions could trigger the YouTube algorithm content moderation. As a workaround, he adapts by modifying the spelling of such words, for example, replacing the letter “e” with the number “3” or the letter “o” with the digit “0.” The technique of replacing common letters with non-alphabetic characters, as observed here, is linguistically classified as leetspeak. This practice originated during the era of online bulletin boards in the 1980s (Perea et al., 2008). By employing leetspeak to respond to the emergent dynamics of power and language resulting from new media, Sofyan also engages in online resistance, which Stano (2022) characterizes as linguistic guerrilla 2.0.

4.4 Social influence

Applying Venkatesh et al. (2003) definition to this research context, social influence refers to the degree to which Sofyan feels that others believe he should adopt and use social media. Sofyan recalls that a friend, who is also a former terrorist, encouraged him to utilize YouTube:

He told me, “You have many activities, but they are undocumented. You should upload them.” So, initially, my channel was merely about documenting my events and activities to prevent them from being forgotten. (personal communication, August 13, 2024)

Sofyan acknowledges the proactive engagement of several non-state actors, notably Indonesia’s prominent Islamic organizations, Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and Muhammadiyah. These groups are actively leveraging social media to disseminate moderate and inclusive religious perspectives. Sofyan notes,

Many young people from Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah backgrounds are becoming more active and progressive. They are stepping forward to correct [radical content] … I also serve as a counterweight because we all share the responsibility… to clarify the actual situation” (personal communication, September 22, 2024)

Sofyan also perceives that various stakeholders highly anticipate his involvement in media-based P/CVE initiatives. He believes his position is crucial for offering the perspective of individuals previously involved in violent extremism. In other words, Sofyan indicated that his primary “important others” are the broader society, particularly individuals who have not yet, or have only minimally, been exposed to radical ideas. Aligned with his desire to immunize society, Sofyan believes that people also want to be exposed to positive content from former terrorists delivered through the social media platforms they engage with daily.

In this regard, Sofyan’s process of social reintegration is evident through his embrace of a new social identity. This observation corroborates Hwang’s study on how former terrorists in Indonesia disengage and quit their networks. According to Hwang (2018), after successfully distancing themselves from the previous network, these individuals construct alternative social identities that “…may eventually displace one’s identity as an extremist” (p. 7). By believing that society requires their active participation, hence the social influences factor, these former extremists undertake new social responsibilities.

4.5 Facilitating conditions

Venkatesh et al. (2003) defined facilitating conditions as “the degree to which an individual believes that an organizational and technical infrastructure exists to support the use of the system.” The UTAUT model posits that facilitating conditions and behavioral intention influence the use behavior of a new system. The three factors discussed earlier—performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence—are determinants shaping behavioral intention toward adopting new technologies. This study focuses on how Sofyan’s facilitating conditions, particularly technical infrastructure availability, affect his YouTube channel use.

The ease of use provided by the YouTube platform enables Sofyan to manage his channel effectively. Despite having limited resources—from essential audiovisual equipment to a simple studio—Sofyan’s messages countering terrorism and radicalism can reach a wider audience. Sofyan recalls that many of his videos suffered from poor audio quality, particularly in the early stages. Due to financial constraints, he gradually improved the production quality by investing in better audiovisual equipment. Sofyan emphasizes that his media-based efforts in initiatives are self-funded:

We are not funded by anyone managing the channel—not by Densus [Indonesian Police Counterterrorism Special Detachment] or BNPT [National Agency for Counterterrorism]. That is why we use inexpensive equipment. (personal communication, September 22, 2024)

However, Sofyan acknowledges that at the outset of his YouTube channel, a senior official from the BNPT (National Agency for Counterterrorism) provided a small contribution to help purchase equipment. In other words, financial resource limitations primarily constrained the frequency of uploading new content, as content production incurred costs. This was particularly evident when inviting other former terrorists as guest speakers or recording Sofyan’s activities outside his hometown.

In this context, Sofyan also mentioned that his channel has reached the monetization stage. The channel has received three payments from YouTube, ranging from one to two million Indonesian Rupiah (approximately USD 62-124). However, he emphasized that this amount is insufficient to cover the channel’s operational costs. Although Sofyan does not seek direct financial gain, he feels proud and pleased that his channel has achieved a significant milestone—one that is not easily reached by a channel with such specialized and non-marketable content.

4.6 Voluntariness of use

Voluntary use refers to whether people embrace and use a system out of choice or because of mandatory obligations (Venkatesh et al., 2003). In this research context, it refers to whether Sofyan’s decision to utilize YouTube was free or pressured by others. In this study, Sofyan uses YouTube voluntarily. He began using digital technology, creating material, and learning primarily on his own initiative. According to the UTAUT framework, the voluntariness of use is a moderating variable for the social influence factor. When voluntariness is high, the impact of social influence on the intention to adopt technology becomes weaker. In this case, although Sofyan is encouraged by his friends (social influence) to utilize digital platforms, the decision to adopt and use YouTube technology primarily stems from Sofyan’s personal choice. He asserted, “I have always been passionate about media technology and creating content. It is something that’s always been in my heart.” (personal communication, September 22, 2024).

4.7 From self-deradicalization to restoration

A more careful analysis of this research shows that there is another factor influencing Sofyan’s motivation to adopt and use YouTube, namely his strong desire to compensate for his past mistakes by spreading positive content to a wider audience. His media-based P/CVE reflects the journey that begins with a process he considers self-radicalization toward his reintegration into society. The inner drive to repair, restore, and reinstate his role and contribution to society keeps him trying to maintain his channel and overcome his obstacles. Sofyan said.

… Back then, we were willing to die for something wrong—so why cannot we now be just as militant for something right? That spirit must not fade. How is it possible that someone once militant has become ayam sayur [spineless wimp]? We still need to be fierce, but this time, we must do so for the right cause. (personal communication, September 22, 2024)

This internal drive appears superficially similar to “hedonic motivation” as defined in the UTAUT2 framework (Venkatesh et al., 2012), an extension of the original model. In the extended framework, hedonic motivation is defined as “the fun or pleasure derived from using a technology” (p. 161). However, this term is not appropriate in the context of this study. The inner drive revealed in Sofyan’s case is more closely related to a higher moral and social calling rather than the sense of fun or pleasure associated with using technology. Therefore, we call it “restorative motivation,” which reflects the extent to which an individual perceives that adopting and using social media technology helps them remedy past wrongs and strives to contribute positively to society as much as possible.

Sofyan’s life journey aligns with the dynamics shown by Hwang (2018) regarding terrorists moving away from their radical understanding. Based on his research on dozens of formers in Indonesia, Hwang shows that there are factors that occur in their disengagement process, all of which happened to Sofyan. However, the importance of each factor may vary in proportion. As he recounted, he went through a process of disillusionment with the movement and divisions among jihadists, along with rational considerations regarding the issue. The process continued with forming a relatively new social network and shifting personal priorities towards reintegration into society.

5 Conclusion

This study investigates how a former terrorist convict engages in P/CVE efforts through the YouTube social media platform. It delves into the factors that support the intention to adopt and the use behavior of this technology. By adopting a media-based P/CVE framework that explains and predicts user adoption and technology use, the UTAUT framework is employed to analyze this process. The research confirms that performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence significantly impact the motivation to adopt YouTube, with performance expectancy emerging as the most critical factor in the intention to adopt. Moreover, adoption motivation and facilitating conditions influence how YouTube is utilized to disseminate peace messages.

However, the findings also reveal two deviations from the original UTAUT framework. Firstly, Sofyan emphasizes that his past experience with digital media reinforces his belief that his YouTube channel will enhance the performance and effectiveness of his P/CVE initiatives, reaching a wider audience. This contradicts the UTAUT framework, which posits experience as a moderating aspect of the other three factors (effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions). Secondly, this research identifies an additional factor termed “restorative motive,” an intrinsic drive to rectify past wrongs. The restorative motive influences the intention to adopt and use social media technology. Indeed, these findings have theoretical implications for the UTAUT framework, which primarily explains the motivation behind technology adoption and use at the level of collective action. At the individual level, the qualitative investigation in this study offers a more nuanced and in-depth understanding, enriching the theoretical discourse on social media adoption and use. An important question arises: are these findings primarily applicable to individuals with unique backgrounds, such as former extremists, or could they also extend to ordinary individuals? This is an area that future research could further explore.

On a practical level, the findings suggest actionable steps to support former extremists’ use of social media, particularly in advancing their civic participation through P/CVE initiatives. By recognizing the significance of past experiences and restorative motivation, governments or civil society organizations (CSOs) could assist these individuals in building capacity, enhancing their technical skills, and improving their messaging strategies and content creation. This process could leverage their personal narratives and restorative drive to create impactful content. Their media-based P/CVE efforts could achieve a more significant societal impact. Indeed, while the state is tasked with formulating P/CVE policies and frameworks, grassroots P/CVE initiatives conducted by individuals such as Sofyan contribute significantly to building community resilience (see also Barton and Vergani, 2022; Sila and Fealy, 2022).

The involvement of former extremists in P/CVE initiatives has emerged as a globally significant topic, extending beyond Indonesia. Various countries have developed best practices, primarily context-specific and not widely disseminated, which suggest that the inclusion of formers offers promise for enhancing program success. While still subject to debate and contestation, a growing consensus indicates that the effectiveness of former extremists’ involvement depends on several factors. These include individual characteristics, geographical context, the background ideology of violent extremism, and the political landscape (Koehler, 2024; Clubb et al., 2024a). In an effort to standardize the engagement of formers in PCVE programs, Clubb et al. (2024b) developed guidelines based on input from 72 participants and experts, including former extremists themselves, from diverse global regions. In this context, Sofyan’s initiatives, driven by his restorative motivations, exemplify a best practice, particularly in mainly self-supported media-based P/CVE efforts by former extremists. Although Sofyan’s initiative is unlikely to be generalizable or universally applicable across different contexts, it undoubtedly enriches the existing models for involving formers in P/CVE.

The limitation of this research lies in its focus on a single channel managed by a male former convicted terrorist; therefore, it is not intended for generalization. Nonetheless, Sofyan’s channel is the most active among those initiated by former offenders, making this research valuable in providing broader insights into social media-based P/CVE in Indonesia. While this study focuses on the aspects of intention and use of social media platforms, future research could analyze the video content uploaded on the channel to categorize and prioritize the key messages conveyed by Sofyan. Additionally, interactions and audience engagement with the content could be examined to assess viewers’ online involvement with the issues raised by Sofyan. Furthermore, to evaluate the effectiveness of this channel as a means of “immunizing” society, reception analysis could be conducted on audiences who have had limited exposure to harmful content.

In any case, the role of social media technology is increasingly critical in shaping public discourse. This arena also holds the potential to be exploited by extremists to carry out their activities in various forms. Consequently, understanding how to counter harmful content remains a highly significant area of study, notably how reformed former terrorists, as credible voices, contribute to P/CVE initiatives through their civic participation. A deeper understanding has substantial implications for digital communication practices and for fostering a safer and more peaceful world.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institute for Research and Community Service (LPPM), Paramadina University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

PW: Resources, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation, Project administration, Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Supervision. JC: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Funding acquisition. Sunaryo: Resources, Validation, Data curation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The Ministry of Higher Education, Science, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia provided funding for this research through the Fundamental Research scheme, as stipulated in contract number 818/LL3/AL.04/2024.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Online Gemini AI was used to translate some parts of the article. Grammarly was used to correct the grammar and improve the clarity of the writing.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Adigwe, C. S., Mayeke, N. R., Olabanji, S. O., Okunleye, O. J., Joeaneke, P. C., and Olaniyi, O. O. (2024). The evolution of terrorism in the digital age: investigating the adaptation of terrorist groups to cyber technologies for recruitment, propaganda, and cyberattacks. Asian J. Econ. Bus. Account. 24, 289–306. doi: 10.9734/ajeba/2024/v24i31287

Aditya, N., Luthfi, M., Rahmat, M., and Hannase, M.. (2019). “Development of counter-narrative delivery strategies by former terrorist as disengagement effort in Indonesia.” In Jakarta: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Strategic and Global Studies, ICSGS 2018.

Alava, S., Frau-Meigs, D., and Hassan, G. (2017). Youth and violent extremism on social media: Mapping the research. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

Altier, M. B., Boyle, E. L., Shortland, N. D., and Horgan, J. G. (2017). Why they leave: an analysis of terrorist disengagement events from eighty-seven autobiographical accounts. Secur. Stud. 26, 305–332. doi: 10.1080/09636412.2017.1280307

Amit, S., Barua, L., and Kafy, A. (2021). Countering violent extremism using social media and preventing implementable strategies for Bangladesh. Heliyon 7. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07121

Arifin, N. A. (2017). The evolution of ISIS in Indonesia with regards to its social media strategy. Jurnal Ilmiah Hubungan Internasional 13, 145–158. doi: 10.26593/jihi.v13i2.2627.145-158

Asrori, S., Ismail, M., Azmi, A. N., and Zulfa, E. A.. (2020). “Deradicalization from within: enhancing the role of jihadists on countering violence extremism.” In Proceedings of the 1st international conference on recent innovations, 745–1752. ScitePress.

Avis, W. (2016). The role of online/social Media in Countering Violent Extremism in East Africa. Helpdesk report: GSDRC. Birmingham, UK: GSDRC, University of Birmingham.

Awan, I. (2017). Cyber-extremism: Isis and the power of social media. Society 54, 138–149. doi: 10.1007/s12115-017-0114-0

Badawy, A., and Ferrara, E. (2018). The rise of jihadist propaganda on social networks. J. Comput. Soc. Sci. 1, 453–470. doi: 10.1007/s42001-018-0015-z

Barton, G., and Vergani, M. (2022). “Disengagement, Deradicalisation, and rehabilitation” in Countering violent and hateful extremism in Indonesia: Islam, gender and civil society. eds. G. Barton, M. Vergani, and Y. Wahid (Singapore: Palgrave MacMilan), 63–82.

Bixter, M. T., Blocker, K. A., Mitzner, T. L., Prakash, A., and Rogers, W. A. (2019). Understanding the use and non-use of social communication technologies by older adults: a qualitative test and extension of the UTAUT model. Geron 18, 70–88. doi: 10.4017/gt.2019.18.2.002.00

BNPT. (n.d.) “BNPT TV.” Accessed November 24, 2024. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/@bnpttv.

Borelli, M. (2023). Social media corporations as actors of counter-terrorism. New Media and Society 25, 2877–2897. doi: 10.1177/14614448211035121

Bouteraa, M., Raja Rizal Iskandar, R. H., and Zainol, Z. (2023). Challenges affecting bank consumers’ intention to adopt green banking technology in the UAE: a UTAUT-based mixed-methods approach. J. Islam. Mark. 14:2466–2501. doi: 10.1108/JIMA-02-2022-0039

Clubb, G., Scrivens, R., and Islam, D. (2024a). “Conclusion: norms and standards for engaging formers in violence prevention” in Former extremists: Preventing and countering violence. eds. G. Clubb, R. Scrivens, and D. Islam (New York: Oxford University Press), 307–320.

Clubb, G., Sengfelder, K., Altier, M. B., Scrivens, R., and Islam, D. (2024b). Standards for employing formers in P/CVE: The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT) policy brief. doi: 10.19165/2024.4600

Creswell, J., and Poth, C. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA & London: SAGE publications.

Eerten, J. J., Van, B. D., Konijn, E., de Graaf, B. A., and de Goede, M. (2017). “Developing a social media response to radicalization: the role of counter-narratives in prevention of radicalization and de-radicalization” in The research and documentation Centre (WODC-2607) (The Netherlands: Ministry of Security and Justice).

Effendi, R., Sukmayadi, V., Unde, A. A., and Triyanto,. (2022). Social media as a medium for preventing radicalization (a case study of an Indonesian youth community’s counter-radicalization initiatives on Instagram). Plaridel 19, 1–7. doi: 10.52518/2021-14edut

Evi, T., Muhamad, S., and Logahan, J.. (2020). “Peace culture of ex-combatant as an alternative program of Deradicalization in Indonesia (case study of Ali Fauzi Manzi).” In ICSGS 2019: Proceedings of 3rd international conference on strategic and global studies, ICSGS 2019, 380. European Alliance for Innovation.

Gansewig, A., and Walsh, M. (2021). Broadcast your past: analysis of a German former right-wing extremist’s YouTube Channel for preventing and countering violent extremism and crime. J. Deradicalization 29, 129–176. doi: 10.1080/09546553.2020.1862802

Gharaibeh, M. K., Mohd Arshad, M. R., and Gharaibh, N. K. (2018). Using the UTAUT2 model to determine factors affecting adoption of mobile banking services: a qualitative approach. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 12, 123–134. doi: 10.3991/ijim.v12i4.8525

Guillén-Gámez, F. D., Colomo-Magaña, E., Ruiz-Palmero, J., and Tomczyk, Ł. (2024). Teaching digital competence in the use of YouTube and its incidental factors: development of an instrument based on the UTAUT model from a higher order PLS-SEM approach. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 55, 340–362. doi: 10.1111/bjet.13365

Gurgun, S., Arden-Close, E., Phalp, K., and Ali, R. (2024). Motivated by design: a codesign study to promote challenging misinformation on social media. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 1:1–26. doi: 10.1155/2024/5595339

Haider, H. (2022). “Countering online misinformation, hate speech or extremist narratives in the global south.” doi: 10.19088/K4D.2022.070

Hakim, Y. R., Bainus, A., and Sudirman, A. (2019). The implementation of counter narrative strategy to stop the development of radicalism among youth: a study on peace generation. Central Europ. J. Int. Sec. Stud. 13, 111–139.

Huda, A. Z., Runturambi, A. J. S., and Syauqillah, M. (2021). Social media as an incubator of youth terrorism in Indonesia: hybrid threat and warfare. Jurnal Indo-Islamika 11, 21–40. doi: 10.15408/jii.v11i1.20362

Hwang, J. C. (2018). Why terrorists quit: The disengagement of Indonesian jihadists. London: Cornell University Press.

International Crisis Group (2010) “Indonesia: Jihadi Surprise in Aceh.” Asia Report No 189. Jakarta/Brussels: International Crisis Group.

Ishak, M. S., Sarkowi, A., Mustaffa, M. F., and Mustapha, R. (2022). Acceptance of YouTube for Islamic information acquisition: a multi-group analysis of students’academic discipline. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 13, 927–937. doi: 10.14569/IJACSA.2022.01307108

Ismail, N. H. (2021). Disrupting Indonesia’s violent extremism online ecosystem: best practices from running a community website. Home Team J. 10, 198–213.

Jayaseelan, R., Kadeswaran, S., and MsBrindha, D. (2020). A qualitative approach towards adoption of information and communication technolgoy by medical doctors applying UTAUT model. J. Xi’an Univ. Architec. Technol. 12, 4689–4703.

Koehler, D. (2024). “Understanding the effectiveness of formers: contexts and measurements” in Former extremists: Preventing and countering violence. eds. G. Clubb, R. Scrivens, and D. Islam (New York: Oxford University Press), 17–36.

Koehler, D., Clubb, G., Bélanger, J. J., Becker, M. H., and Williams, M. J. (2023). Don’t kill the messenger: perceived credibility of far-right former extremists and police officers in P/CVE communication. Stud. Conflict. Terror., New York: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2023.2166000

Krona, M. (2020). Collaborative media practices and interconnected digital strategies of Islamic state (IS) and pro-IS supporter networks on telegram. Int. J. Commun. 14, 1888–1910.

Lawrence, N., and Robertson, B. W. (2023). Extremist organizations and online platforms: a systematic literature review. Qual. Res. Rep. Commun. 25, 93–103. doi: 10.1080/17459435.2023.2240808

Lee, J. L.. (2011). User behaviors toward Mobile video adoption in Taiwan: a qualitative study. In The 8th Asia-Pacific regional conference of the international telecommunications society (ITS): “Convergence in the digital age”, Taipei, Taiwan, 26th-28th June, 2011. International Telecommunications Society (ITS), Calgary.

Limna, P., Siripipatthanakul, S., Siripipattanakul, S., and Auttawechasakoon, P. (2023). The UTAUT model explaining intentions to use telemedicine among Thai people during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study in Krabi, Thailand. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Res. 7, 1468–1486. doi: 10.25147/ijcsr.2017.001.1.111

Macdonald, S., Staniforth, A., and Mathieson, N. (2023). Tackling online terrorist content together: Cooperation between counterterrorism law enforcement and technology companies : Global Network on Extremism and Technology (London: GNET). Available at: https://open.ncl.ac.uk/ISBN:9781739604400

Marikyan, D., and Papagiannnidis, S. (2023). “The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: a review” in TheoryHub book. ed. S. Papagiannidis.

Menon, D., and Shilpa, K. (2023). ‘Chatting with ChatGPT’: analyzing the factors influencing users’ intention to use the open AI’S ChatGPT using the UTAUT model. Heliyon 9:e20962. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20962

Miller, C. (2022). “Social media and system collapse: how extremists built an international neo-Nazi network” in Antisemitism on social media. eds. M. Hubscher and S. von Mering (London: Routledge), 93–113.

Minter, S. (2021). An ideology online: explaining the causes and proliferation of white supremacist terrorism. SSRN Electron. J. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3790829

Moir, N. (2017). Isil radicalization, recruitment, and social media operations in Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. PRISM 7, 91–107. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26470500

Momani, A. M. (2020). The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: a new approach in technology acceptance. Int. J. Sociotechnol. Knowl. Dev. 12, 79–98. doi: 10.4018/IJSKD.2020070105

Monaci, S. (2017). Explaining the Islamic state’s online media strategy: a transmedia approach. Int. J. Commun. 11, 2842–2860.

Muhyiddin, M., and Priyanto, S. (2023). Deradicalization narratives from former convicts in the digital space: Sofyan Tsauri’s YouTube Channel analysis. Jurnal Komunikasi Islam 13, 1–23. doi: 10.15642/jki.2023.13.01.1-23

Nasir, A. A. (2019). Women in terrorism: evolution from Jemaah Islamiyah to Islamic state in Indonesia and Malaysia. Count. Terror. Trends Anal., London: Royal United Services Institute 11:19–25.

Nasution, S., Sukabdi, Z., and Priyanto, S. (2021). Credible voice of Sofyan Tsauri as the deradicalization strategy for former terrorism prisoners. Technium Soc. Sci. J. 25, 675–686.

Neudert, L. M. (2023). Regulatory capacity capture: the United Kingdom’s online safety regime. Int. Policy Rev. 12:1–34. doi: 10.14763/2023.4.1730

Nguyen, Q. N., and Le, T. D. H. (2023). Factors affecting Youtube acceptance for student learning needs. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 18, 99–114. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v18i23.41647

Noor, H. (2024). From villain to hero: the role of disengaged terrorists in social reintegration initiatives. Polit. Gov. 12:1–18. doi: 10.17645/pag.7838

Novenario, C. M. I. (2016). Differentiating Al Qaeda and the Islamic state through strategies publicized in jihadist magazines. Stud. Conflict Terrorism 39, 953–967. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2016.1151679

Nuraniyah, Nava. (2019). Evolution of online violent extremism in Indonesia and the Philippines. London: Royal United Services Institute for Defence and security studies and IPAC. 11.

Nymberg, P., Bandel, I., Bolmsjö, B. B., Wolff, M., Calling, S., Leonardsen, A. C. L., et al. (2024). How do patients experience and use home blood pressure monitoring? A qualitative analysis with UTAUT 2. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 42, 593–601. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2024.2368849

Papatheodorou, K. (2023). Policy paper: the ethics of using formers to prevent and counter violent extremism. J. Deradical. 35, 208–205.

Parker, D., and Lindekilde, L. (2020). Preventing extremism with extremists: a double-edged sword? An analysis of the impact of using former extremists in Danish schools. Educ. Sci. 10:1–19. doi: 10.3390/educsci10040111

Perea, M., Duñabeitia, J. A., and Carreiras, M. (2008). R34d1ng W0rd5 W1th Numb3r5. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 34, 237–241. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.34.1.237

Rempel, H. G., and Mellinger, M. (2015). Bibliographic management tool adoption and use: a qualitative research study using the UTAUT model. Ref. User Serv. Q. 54:45–53. doi: 10.5860/rusq.54n4.43

Risius, M., Blasiak, K. M., Wibisono, S., and Louis, W. R. (2024). The digital augmentation of extremism: reviewing and guiding online extremism research from a sociotechnical perspective. Inf. Syst. J. 34, 931–963. doi: 10.1111/isj.12454

Riyanta, S. (2022). Shortcut to terrorism: self radicalization and lone-wolf terror acts: a case study of Indonesia. J. Terror. Stud. 4:1–20. doi: 10.7454/jts.v4i1.1043

Rochman, F.. (2024). “Kemenkominfo Tangani 5.731 Konten Terkait Radikalisme Di Ruang Digital.” AntaraNews, March 22, 2024. Available online at: https://www.antaranews.com/berita/4024440/kemenkominfo-tangani-5731-konten-terkait-radikalisme-di-ruang-digital

Rohmatulloh, D. M., As’ad, M., and Malayati, R. M. (2022). Gus Baha, Santri Gayeng, and the rise of traditionalist preachers on social media. J. Indon. Islam 16, 303–325. doi: 10.15642/JIIS.2022.16.2.303-325

Saltman, E., Kooti, F., and Vockery, K. (2023). New models for deploying counterspeech: measuring behavioral change and sentiment analysis. Stud. Conflict Terrorism 46, 1547–1574. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2021.1888404

Schewe, J., and Koehler, D. (2021). When healing turns to activism: formers and family members’ motivation to engage in P/CVE. J. Deradicalization 28, 141–182.

Schmidt, L. (2021). Aesthetics of authority: ‘Islam Nusantara’ and Islamic ‘radicalism’ in Indonesian film and social media. Religion 51, 237–258. doi: 10.1080/0048721X.2020.1868387

Scrivens, R., Windisch, S., and Simi, P. (2020). “Former extremists in radicalization and counter-radicalization research” in Sociology of crime, law and deviance. eds. D. M. D. Silva and M. Deflem, (Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited), 25:209–224.

Shah, H. A. R., Zada, K., Ali, N. M., and Sahid, M. M. (2022). “Peace in ASEAN: counter-narrative strategies against the ideologies of radicalism and extremism (goal 16)” in Good governance and the sustainable development goals in Southeast Asia. eds. R. M. Khalid and A. J. Maidin (New York: Routledge), 194–211.

Sila, M. A., and Fealy, G. (2022). Counterterrorism, civil society organisations and peacebuilding: the role of non-state actors in deradicalisation in Bima, Indonesia. Asia Pac. J. Anthropol. 23, 97–117. doi: 10.1080/14442213.2022.2041076

Solahudin, (2013). The roots of terrorism in Indonesia: From Darul Islam to Jema’ah Islamiyah. Sydney: NewSouth Publishing.

Stano, S. (2022). “Linguistic guerrilla warfare 2.0: on the ‘forms’ of online resistance” in Rivista Italiana Di Filosofia Del Linguaggio, 177–186. doi: 10.4396/2022SFL13

Tapley, M., and Clubb, G. (2019). The role of formers in countering violent extremism. The Hague: International Centre for Counter-Terrorism.

Thorley, T. G., and Saltman, E. (2023). Gifct tech trials: combining behavioural signals to surface terrorist and violent extremist content online. Stud. Conflict Terrorism, 46:1–26. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2023.2222901

Tio, R., and Kruber, S. (2022). “Online P/CVE social media efforts” in Countering violent and hateful extremism in Indonesia: Islam, gender and civil society. eds. G. Barton, M. Vergani, and Y. Wahid (Singapore: Palgrave MacMillan), 235–254.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., and Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q. 27:425–478. doi: 10.2307/30036540

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., and Xu, X. (2012). “Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology.” MIS Quarterly, 36, 157–78.

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., and Xu, X. (2016). Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: a synthesis and the road ahead. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 17, 328–376. doi: 10.17705/1jais.00428

Waldman, S., and Verga, S. (2016). Countering violent extremism on social media. Ottawa: Defence Research and Development Canada.

Wallace, M. S. (2023). Credible messengers, formers, and anti-war veterans: former fighters as resources for violence/war disruption. J. Pacifism Nonviol. 1, 236–268. doi: 10.1163/27727882-bja00016

Wang, J., Li, X., Wang, P., Liu, Q., Deng, Z., and Wang, J. (2022). Research trend of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology theory: a bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 14:1–20. doi: 10.3390/su14010010

Widya, B., Syauqillah, M., and Yunanto, S. (2020). The involvement of ex-terrorists inmates and combatants in the disengagement from violence strategy in Indonesia. J. Terrorism Stud. 2:1–18. doi: 10.7454/jts.v2i2.1022

Wildan, M. (2022). “Countering violent extremism in Indonesia: the role of former terrorists and civil society Organisations” in Countering violent and hateful extremism in Indonesia: Islam, gender and civil society. eds. G. Barton, M. Vergani, and Y. Wahid (Singapore: Palgrave MacMillan), 195–124.

Williams, M. D., Rana, N. P., and Dwivedi, Y. K. (2015). The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): a literature review. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 28, 443–488. doi: 10.1108/JEIM-09-2014-0088

Williams, T. J. V., Tzani, C., Gavin, H., and Ioannou, M. (2023). Policy vs reality: comparing the policies of social media sites and users’ experiences, in the context of exposure to extremist content. Behav. Sci. Terror. Polit. Aggress. 17, 110–127. doi: 10.1080/19434472.2023.2195466

Wilson, J.. (2017). “Life after white supremacy: the former neo-fascist now working to fight hate.” The Guardian, April 4, 2017. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/04/life-after-hate-groups-neo-fascism-racism.

Winter, C., Neumann, P., Meleagrou-Hitchens, A., Ranstorp, M., Vidino, L., and Fürst, J. (2020). Online extremism: research trends in internet activism, radicalization, and counter-strategies. Int. J. Confl. Viol. 14, 1–20. doi: 10.4119/ijcv-3809

Xue, L., Rashid, A. M., and Ouyang, S. (2024). The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) in higher education: a systematic review. SAGE Open 14, 1–22. doi: 10.1177/21582440241229570

Yar, M. (2018). A failure to regulate? The demands and dilemmas of tackling illegal content and behaviour on social media. Int. J. Cybersecur. Intell. Cybercrime. 1, 5–20. doi: 10.52306/01010318rvze9940

Keywords: preventing/countering violent extremism (P/CVE), unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT), social media, former terorrists, YouTube, online public sphere

Citation: Widjanarko P, Chusjairi JA and Sunaryo (2025) “Immunizing” communities: social media and preventing/countering violent extremism initiatives by former terrorists. Front. Commun. 10:1593509. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1593509

Edited by:

Cassian Shenanigans Scruggs-Vian, University of the West of England, United KingdomReviewed by:

Michalis Tastsoglou, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, GreeceSapto Priyanto, University of Indonesia, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Widjanarko, Chusjairi and Sunaryo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Putut Widjanarko, cHV0dXQud2lkamFuYXJrb0BwYXJhbWFkaW5hLmFjLmlk

Putut Widjanarko

Putut Widjanarko Juni Alfiah Chusjairi

Juni Alfiah Chusjairi Sunaryo2

Sunaryo2