- 1College of Media and International Culture, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

- 2Faculty of Public Relations and Communication, Ho Chi Minh City University of Economics and Finance, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Introduction: The rural tourism industry has experienced significant growth in the Mekong subregion, with women playing a crucial role in its development. This sector empowers women by enhancing their societal status and amplifying their voices.

Methods: This study examines the representation of women in rural tourism across Mekong subregion countries, focusing on visual and textual content from Destination Marketing Organization (DMOs) websites. It further assesses the alignment of these portrayals with government-led gender empowerment initiatives. Using content analysis, this research evaluates DMOs websites from the Mekong Subregion to explore comparative insights into gendered representations.

Results: The findings reveal disparities in how men and women are portrayed: women are frequently depicted as active contributors to rural tourism within economic and socio-cultural frameworks, while men, by contrast, are more prominently featured as customers and decision-makers in political contexts. The analysis indicates that textual content downplays gender issues compared to visuals. Additionally, Vietnam and Yunnan (China) prioritize female visibility in rural tourism development, while Laos and Myanmar exhibit more conservative representations. A notable finding is the presence of indirect governmental initiatives promoting gender balance across all websites.

Discussion: The study urges policymakers and DMOs to adopt intentional strategies for equitable gender representation, ensuring women’s roles in rural tourism are both visible and empowered. It also calls for stronger alignment between tourism marketing and national gender policies in the region.

1 Introduction

The Mekong Subregion (GMS), encompassing Yunnan and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (China), Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam, is renowned for its rich cultural heritage (Hai and Ngan, 2022), diverse ecosystems, and abundant natural resources (Lyu et al., 2013). Rural life in this region remains deeply intertwined with local communities’ livelihoods and traditions (Lois and Kenneth, 2018). These characteristics have fostered the growth of rural tourism, which serves as a catalyst for local development and women’s empowerment (Dung et al., 2023).

The tourism industry in the Mekong Subregion is projected to generate up to $7.62 billion in revenue (Statista, 2024b, 2024c, 2024d, 2024e), accounting for approximately 5% of Southeast Asia’s gross agricultural production value by 2025 (Statista, 2024a). Within this sector, agricultural tourism is a key driver of the region’s competitive advantage (Biddulph, 2020; Mura and Sharif, 2015).

Recent studies highlight the pivotal role of women in rural tourism across the Mekong Subregion. For examples, in Cambodia, the social enterprise Artisans Angkor employs over 800 artisans, predominantly women, to preserve traditional handicrafts for tourism (Biddulph, 2020). Similarly, in Vietnam, women lead community-based tourism initiatives, such as homestays and culinary experiences, adding distinct value to the sector (Quang et al., 2024). In Yunnan (China), women manage homestay businesses (Jin et al., 2024) and educate tourists about the nutritional and culinary uses of geomushrooms (local edible fungi), enhancing visitor experiences while safeguarding local knowledge (Jin et al., 2024).

However, while tourism is a powerful driver of economic growth, it may initially exacerbate gender inequalities, particularly in the early stages of tourism development. In the Mekong River Basin region, the uneven distribution of tourism-related resources among communities risks widening existing gender disparities (Sithirith, 2021). Women from indigenous or ethnic minority communities often face additional barriers to accessing tourism benefits, leading to income and opportunity gaps within the industry (Adnyani et al., 2021).

Scholars emphasize that such inequalities demand further research and targeted initiatives to advance gender equality (Alarcón and Cole, 2019; Araújo-Vila et al., 2021; Bhatta and Ohe, 2020; Bianchi and Man, 2021). Crucially, achieving gender equality in tourism extends beyond increasing women’s participation, which requires addressing systemic inequities, including representational biases in communication (Araújo-Vila et al., 2021; Zafar et al., 2024). Studies suggest that positive media portrayals of women in tourism can elevate their societal status (Dong and Khan, 2023; Panić et al., 2024) and that well-constructed destination images, including equitable gender representations—shape travelers’ perceptions and visit intentions (Rodrigues et al., 2023). Media platforms also offer women opportunities to amplify their voices within the industry (Damavandi et al., 2022).

Yet research on rural tourism marketing reveals persistent gaps in gender representation. For instance, a study of industrial heritage tourism in Bergslagen, Sweden, identified male-centric narratives dominating media coverage, emphasizing men’s roles in cultural preservation (Funk and Pashkevich, 2020). Similarly, an analysis of 394 travel advertisements on social media found pervasive gender stereotypes and biases that reinforce inequalities (Chhabra et al., 2011).

Investigating gender representation gaps in tourism communication enables researchers to advocate for more inclusive marketing strategies that accurately reflect women’s contributions to rural tourism (Panić et al., 2024). Such analysis informs policymakers in designing targeted initiatives, such as training programs and funding for women entrepreneurs, to bolster women’s participation (Dong and Khan, 2023). Additionally, examining media’s role in shaping gender representations can help develop strategies to promote positive portrayals of women in rural tourism, challenging stereotypes and advancing equitable visibility (Fajri et al., 2022; Senyao and Ha, 2022).

Prior research employs diverse theoretical lenses to analyze tourism’s gendered dynamics such as Feminist Political Ecology (Cole, 2017), the framework for revealing how women’s exclusion from governance perpetuates marginalization in tourism planning. Meanwhile, Kuma and Godana’s (2023) use Women and Development (WAD) approach to identify socio-cultural and economic barriers to empowerment in rural Ethiopia, while Jabeen et al. (2020) demonstrate its utility in evaluating policy interventions that strengthen women’s agency in Pakistan’s tourism sector. Parallel scholarship critiques gendered representations in destination marketing, from Marchi et al.’s (2023a,b) deconstruction of DMOs narratives in Europe to Suradin’s (2017) analysis of Halal tourism’s commodification of gender in Indonesia. However, these strands of research remain largely disconnected.

While media studies have extensively analyzed urban tourism narratives (Marchi et al., 2023b), rural tourism representations, particularly in the GMS, remain understudied in communication research (He and Mai, 2021; Nga, 2024) neglecting qualitative examinations of how media portrayals reinforce or disrupt traditional gender roles. As DMOs serve as powerful channels shaping tourist expectations and local self-perceptions (Lončarić et al., 2013; Omar et al., 2022) there is a critical need for studies that bridge theory and DMOs analysis to interrogate how rural tourism marketing in the GMS constructs gendered narratives.

This study investigates gender representation in GMS rural tourism marketing media through three primary objectives: (1) Critical Analysis: To examine how women’s roles and contributions are portrayed in official tourism promotions (both visual and textual content); (2) Policy Alignment Assessment: To evaluate the congruence (or disparity) between these media representations and existing gender empowerment initiatives in the region; and (3) Framework Development: To construct an evaluative framework for improving equitable representation in tourism communication, offering actionable recommendations for DMOs and policymakers to enhance women’s visibility and counter restrictive narratives in agritourism.

By integrating feminist media theory with destination communication studies, this research provides a critical analytical lens for current representation gaps and practical guidelines for gender-sensitive agritourism media in developing contexts. The findings will equip DMOs, policymakers, and media practitioners with evidence-based strategies to foster authentic, empowering portrayals of women in rural tourism development. This study addresses three key questions:

RQ1: To what extent do DMOs websites in the Mekong Subregion reflect gender-equitable representations in rural tourism?

RQ2: How visible are government/DMOs-led gender equality initiatives on these DMOs platforms?

RQ3: What actionable strategies can DMOs implement to improve gender media representation and advance SDG 5 (Gender Equality) goals?

2 Literature review

2.1 Gender equality in rural tourism in the Mekong Subregion

Gender equality is defined as a state where individuals of all genders have equal rights, responsibilities, and opportunities (UNICEF, 2017). In tourism, gender equality is a multi-dimensional, multi-level, and multi-actor concept that extends beyond women’s empowerment alone (Alarcón and Cole, 2019; Ferguson and Alarcón, 2015; Su et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2022). It encompasses equitable access to resources, decision-making processes, and opportunities across economic, political, and social spheres (Ferguson and Alarcón, 2015; Su et al., 2024). As a core pillar of sustainable development, gender equality is critical for the long-term viability of tourism (Alarcón and Cole, 2019; Su et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2022). The industry can enhance women’s socioeconomic status by fostering employment and entrepreneurship (Peña-Sánchez et al., 2020; Su et al., 2024; UNWTO, 2010, 2022b; Zhang et al., 2022). In agritourism specifically, women have transcended traditional roles through improved social and economic standing (Sulaj and Themelko, 2024), assumed leadership positions, reshaping community dynamics (Mwinnoure and Dzitse, 2024). Consequently, the interplay between tourism and gender equality has garnered significant scholarly attention (Alarcón and Cole, 2019).

Research aligns gender equity in tourism with multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 5 (Gender Equality)—Equal opportunity creation; SDG 8 (Decent Work)—Reducing economic disparities; SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities)—Empowering marginalized groups through inclusive policies (Ferguson, 2011; Ferguson and Alarcón, 2015). In rural settings, these dynamics manifest distinctively, such as in Andes, agritourism has enabled women to shift from domestic roles to income generation and community leadership (Arroyo et al., 2019). In the Mekong Delta, homestay tourism challenges traditional norms while equipping women with practical skills (Quang et al., 2024). Globally, women’s participation in rural tourism, from Iran’s Kurdistan to Greek ecotourism, correlates with more sustainable resource management and culturally sensitive development practices (Ghanian et al., 2017). These cross-regional findings highlight rural tourism’s unique potential to advance gender equality through integrated economic, cultural, and environmental pathways.

Rural tourism encompasses all tourism activities conducted in rural areas (Nair et al., 2023). In the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS)—where approximately 80% of the population resides in rural areas (Singh, 2007)—rural tourism has grown significantly since the 1990s. This growth has been driven by increasing international interest in eco-friendly tourism practices and greater emphasis on local community participation (Bouchon and Rawat, 2016; Giang, 2024; Nair et al., 2023). Rural tourism in the GMS typically features by homestay experiences, eco-tours, agricultural immersion activities (Diep and Duong, 2022; Lalisan et al., 2024). While rural tourism serves as the overarching framework, it encompasses several specialized forms, such as agritourism—Combines agricultural activities with visitor experiences; farm tourism—focuses on farm visits and related tourism; agricultural tourism—involves visiting agribusinesses as travel experiences; agri-tourism—features farm stays with rural life experiences (Petroman and Petroman, 2010; Santosh et al., 2023). Given that GMS tourism typically combines agricultural activities (Gia, 2021; Phuong, 2019), farm visits and local homestay (He and Mai, 2021; Quang et al., 2024), this study employs all these terms interchangeably to describe rural tourism activities in the region.

Research demonstrates that agritourism provides multiple benefits such as generating supplemental income for farmers (Alampay and Rieder, 2008; Gia, 2021), promoting sustainable agricultural practices (Alampay and Rieder, 2008), facilitates community engagement and enables cultural exchange by sharing heritage, traditions, and natural environments with visitors (Gia, 2021).

Governments across the Mekong region have implemented strategic initiatives to promote sustainable tourism development and local community benefits. Notable examples include the collaboration between governments and NGOs have improved water resource management and community well-being (He and Mai, 2021) and the initiatives have empowered women by generating sustainable income while enabling them to remain in their villages (Quang et al., 2024).

However, both vertical (hierarchical) and horizontal (sectoral) discrimination against women remains prevalent (ADB, 2022; Alampay and Rieder, 2008). Moreover, current tourism policies show limited efficacy in advancing gender equity (Adnyani et al., 2021). Investigating gender disparities in the Mekong region could identify specific barriers to women’s advancement and inform targeted educational and vocational training programs Investigating the gender disparities in the Mekong region (Campos-Soria et al., 2011; Hillman and Radel, 2022). In addition, it could reveal discrimination patterns through women’s lived experiences and aspirations (Ferguson, 2011). Thus, there is critical need for further research on gender equality in GMS tourism, development of strategies to ensure women’s participation in tourism governance and sustainable tourism outcomes.

2.2 Theoretical framework

In the rural context, a woman’s position is determined by factors of education, income, participation in the decision-making process, and participation in the leadership process (Jabeen et al., 2020; Kuma and Godana, 2023). The representation of women in rural areas in the media is shaped by various theoretical and methodological frameworks, including the Women and Development (WAD) Approach (Abdullah and Hamid, 2024), Framing Theory (Li et al., 2022; Weder et al., 2019) and Feminist Realism (Mooney, 2000). WAD is a feminist approach that emerged in the 1970s and focuses on the relationship between women and development processes (Brahma, 2022). WAD emphasizes that the role of women in and out of the household is essential to the development of society (Brahma, 2022). Previous studies stated that a lack of rural women’s representation in media might affect their position in society (Abdullah and Hamid, 2024; Rae and Diprose, 2024). However, in the previous study, Sirakaya and Sönmez studied state travel advertising flyers, finding out that women are often portrayed through traditional stereotypes, such as subordination and dependency (Sirakaya and Sonmez, 2000). In a research on destination imagery, authors stated that travel marketing often follows the expectations of Western men, maintaining gender roles that have been established in stereotypes (Stoleriu, 2016). Therefore, many scholars argue that the roles of women in rural development need to be acknowledged (Abdullah and Hamid, 2024; Rae and Diprose, 2024). Framing theory argues that the way information is presented can significantly affect audience perception and interpretation, including travel media (Chong and Druckman, 2007; Sullivan, 2023; Weder et al., 2019). Framing theory provides critical insights into how media narratives and destination marketing strategically highlight specific aspects of experiences to influence traveler perceptions and behaviors (Chong and Druckman, 2007; Li et al., 2022; Satriya et al., 2024). By emphasizing positive attributes—such as authentic cultural encounters or sustainable practices—tourism marketers can consciously shape tourist expectations and decision-making processes (Man and Yu, 2024). This selective presentation creates cognitive shortcuts that make certain destinations or activities appear more appealing, ultimately driving visitation and engagement (Hansen, 2020). In a study of the scope of media coverage of medical tourism, authors found how women as tourists or stakeholders can be represented in ways that emphasize vulnerability depending on the narrative constructed by travel marketing (Jun and Oh, 2015). Mooney explores the different ways that travel marketing frames women’s participation, whether as empowered entrepreneurs or passive consumers, to create a more equitable environment (Mooney, 2020). Another study found that when travel information frames stories to benefit both travelers and local communities, it increases participation and support for women-led initiatives (Li et al., 2022). Soulard et al. discuss framing women in dark travel experiences, which revolve around historical events, which can influence public perceptions of women’s role in consuming and reshaping dark travel narratives (Soulard et al., 2023). This study also integrates Feminist Realism, a theoretical lens that foregrounds the material and structural realities of gender inequality (Binetti, 2019; Mooney, 2000), to critically assess how systemic barriers and uplifts shape women’s agency and representation in Mekong Delta agritourism. Similar to Critical Realism, this framework acknowledges an objective reality beyond discourse, emphasizing how institutional power dynamics constrain or advance women’s participation in tourism (Binetti, 2019). Empirical evidence reveals persistent patterns: women are overrepresented in low-wage, stereotypical roles (e.g., “cleaning ladies”) yet underrepresented in leadership, a disparity exacerbated by crises like COVID-19 (Je et al., 2025; Li et al., 2023; Opoku et al., 2024). For example, in tourism, previous studies examine barriers to promotion and discrimination, sexual harassment and assault to women in tourism (Je et al., 2025; Opoku et al., 2024), overrepresented in stereotypical, low-paid roles while under-representation as leaders (Je et al., 2025; Li et al., 2023; Opoku et al., 2024), lack of recognition and support (Je et al., 2025; Opoku et al., 2024). Furthermore, Feminist Realism highlights how institutional and systemic factors limit women’s agency (Binetti, 2019; Li et al., 2023). For example, Li et al. (2023) found out how structural systems, such as positional power and meritocratic myths, naturalize inequality, as seen in Guilin’s tourism sector, where women face diminished wages and restricted access to public services despite industry growth. In addition, Feminist Realism exposes root causes of women’s underrepresentation in tourism (Je et al., 2025). For example, Je et al. (2025) stated that ambivalent sexism and internalized biases among both leaders and female workers perpetuate these inequities, discouraging collective challenges to the status quo. Widiastini et al. (2021) found the female tourism workers in Bali often occupy lower-middle-class positions due to traditional gender roles, limited access to higher positions, and the impact of crises like the Covid-19 pandemic, which disproportionately affect women workers.

In recent studies, scholars found out media actively construct gendered narratives of place and identity, necessitating feminist critiques to expose power dynamics in tourism representations (Figueroa-Domecq and Segovia-Perez, 2020; Frohlick and Macevicius, 2023). Furthermore, digital platforms amplify these gendered discourses, with feminist media analyses revealing how short videos, podcasts, and other formats challenge patriarchal norms in tourism marketing (Saputri, 2021; Wang, 2024). Besides that, feminist tourism research advocates for theoretical and methodological shifts, proposing frameworks to integrate intersectional, decolonial, and reflexive approaches that disrupt traditional paradigms (Munar, 2017). Interdisciplinary studies highlight the intersection of media, gender, and embodied practices, emphasizing how tourism spaces and policies can be reimagined through feminist-cultural collaborations (Díaz-Carrión and Vizcaino-Suárez, 2019; Yang et al., 2018). In addition, the Women and Development (WAD) approach critiques Western-centric models and highlights women’s active roles in development, offering media studies a lens to analyze how gender representations in media, from advertisements to news, either reinforce or challenge structural inequalities (Brahma, 2022). By emphasizing patriarchy, capitalism, and women’s agency, WAD encourages scrutiny of biases in media portrayals, particularly regarding marginalized voices in the Global South (Brahma, 2022; Ricke, 2022). This framework also connects to studies on alternative media and grassroots movements, examining how media shapes or disrupts narratives of women’s socio-economic participation and collective action globally (Ricke, 2022).

This study employs Goffman’s framing theory (Sullivan, 2023) to analyze how Mekong Delta agritourism websites construct and reinforce gendered narratives (Objective 1), while WAD approach (Brahma, 2022) bridges the gap between these mediated portrayals and on-the-ground gender empowerment efforts (Objective 2). The research further adopts Feminist Realism (Binetti, 2019; Mooney, 2000) to propose actionable communication strategies for DMOs, aligning their practices with SDG 5 (gender equality) in GMS rural tourism (Objective 3). Applying these frameworks to rural tourism, this study analyze how DMOs construct narratives that either reinforce or challenge traditional power dynamics. This approach not only aligns with global gender equity goals but also offers actionable insights for media practitioners to create more inclusive narratives that reflect women’s agency in sustainable tourism development.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Data collection

Website content analysis has emerged as an essential research method in tourism studies, allowing researchers to gain a deeper understanding of how destinations and travel organizations express their identities, attract visitors, and communicate important information about their services (Ip et al., 2011; Suradin, 2017; Zaim et al., 2022). Website content analysis help to assess how digital platforms reflect and reinforce societal gender norms (Hallett and Kaplan-Weinger, 2010; Parasnis, 2022). By examining textual and visual elements, such as images, narratives, and promotional materials, researchers can decodes how websites identities are generated and promoted through content (Hallett and Kaplan-Weinger, 2010), and how women are represented in tourism narratives (Hallett and Kaplan-Weinger, 2010; Parasnis, 2022). For instance, Parasnis (2022) use this method to uncover how women are often sexualized and exoticized in tourism marketing, as seen in the study of Jamaican tourism images. Similarly, the study on tourism promotional content found that women are frequently associated stereotype gender norms (Sun, 2017).

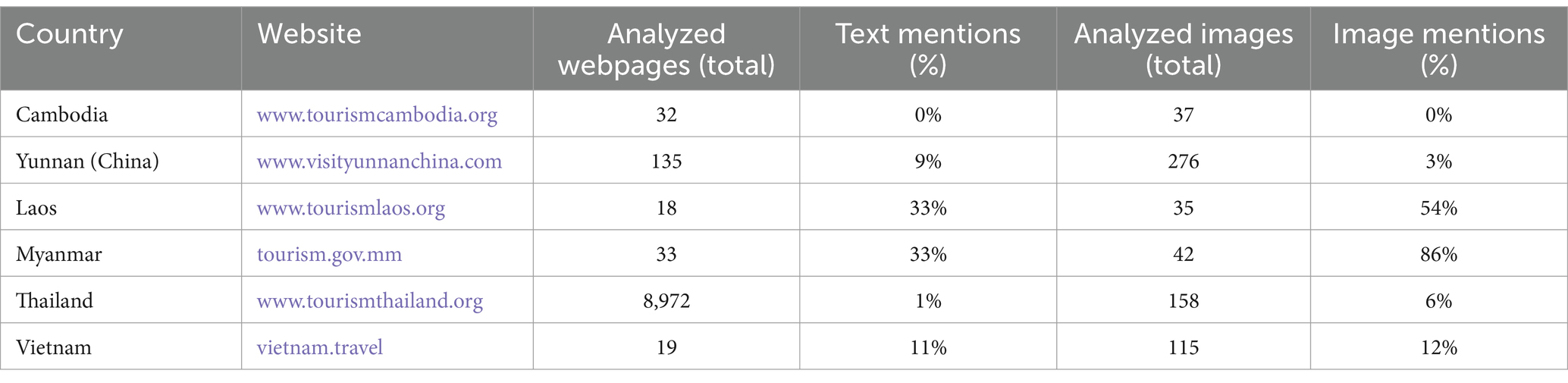

Data collection was conducted in February 2025, focusing on available rural tourism content from official Mekong region tourism boards. Six national DMOs in GMS were selected to ensure representativeness, as these sources reflect institutional perspectives on gender roles in regional tourism. Name of the DMOs, the number of analyzed webpages and pictures for each country are listed in Table 1. However, two exceptions necessitated exclusion: Cambodia’s official tourism website lacked gender-related content, emphasizing only destination promotion, while the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region’s site was inaccessible during data collection, with no viable alternative available. For consistency, the study analyzed English-language versions of these websites.

Searching for rural tourism content in DMOs were conducted via: (1) Internal website search functions of these DMOs; (2) Google’s site operator (e.g., site:tourismlaos.org “rural tourism”); and (3) Manual navigation of “Experience” or “Destination” sections these DMOs. Focusing on rural tourism, we prioritized keywords from previous studies: “village tourism” (Ayazlar and Ayazlar, 2015); “agro-tourism,” agritourism” (Giang, 2024; Thea and Mardy, 2023), “agricultural tourism,” “farm tourism,” culture tourism (Hau and Tuan, 2017), “rural tourism,” “ecotourism” (Rosalina et al., 2021; Nair et al., 2023), “community-based tourism (CBT)” (Müller et al., 2020).

Textual references to gender were extracted using text mining technique with a predefined lexicon for the roles and demographic: “mother,” “father,” “wife,” “husband,” “girl,” “boy,” and “family.” Later, each article underwent a manual review to validate its relevance to the topic of gender. For example, text mentioning “family” without gendered roles were excluded, while those describing “women-led weaving workshops” were retained.

All images of rural tourism on these DMOs were collected, then filtered by: (1) exclusion of non-human subjects (e.g., landscapes, logos); and (2) removal of duplicates (via manual checks). Images were coded for presence (male/female/non-binary) and roles (e.g., laboring, caregiving, guiding).

3.2 Data analysis

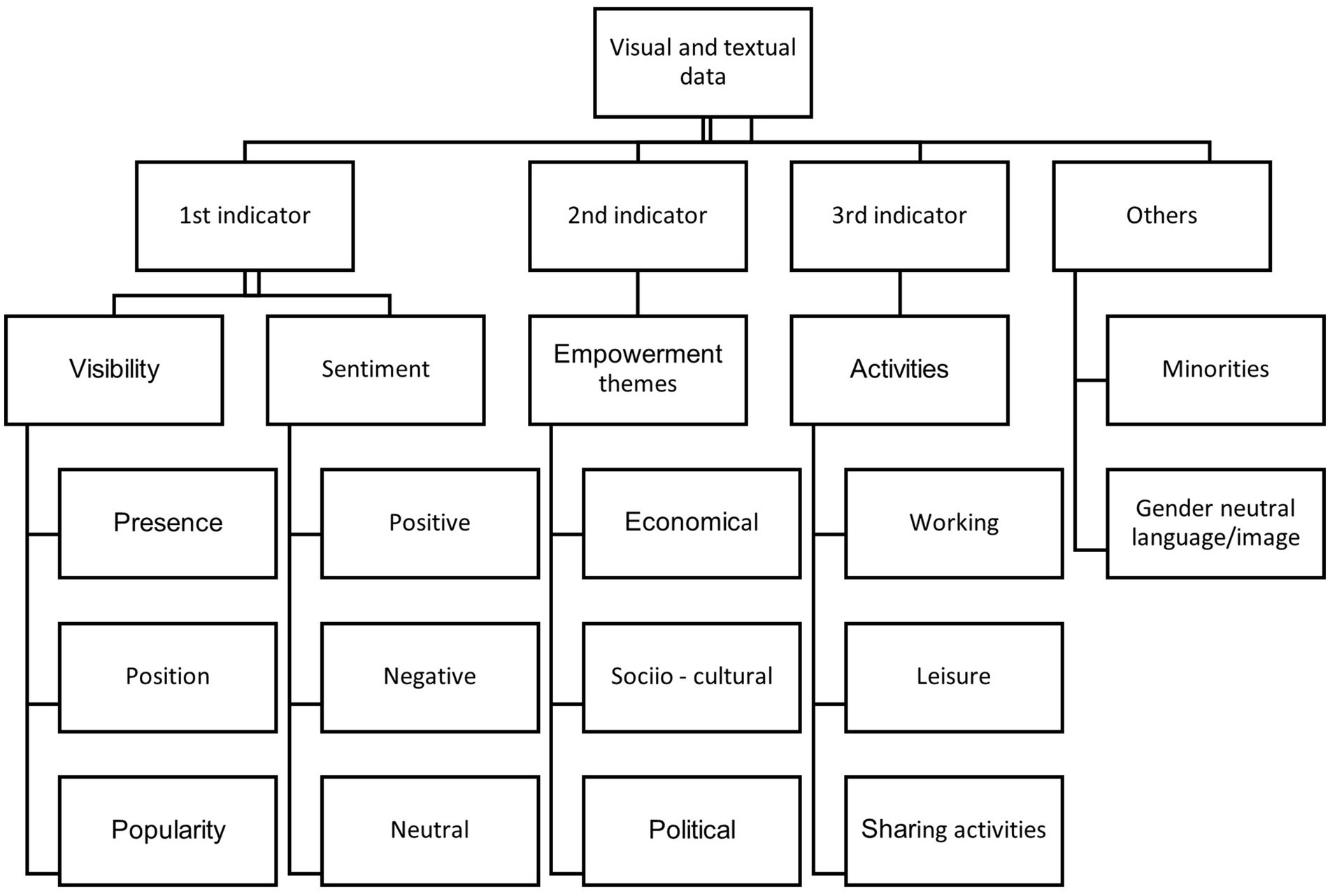

Each picture and text were analyzed using a pre-designed codebook (Appendix 1), which was adapted from previous studies (Marchi et al., 2023a; Picazo and Moreno-Gil, 2019), with three core indicators (Figure 1): (1) Physical space (e.g., farm, marketplace); (2) Subject demographics (gender); and (3) Subject action (e.g., laboring, guiding, caregiving). The codebook uses media framing to examines the tone of gender portrayals, the division of gendered labor in tourism settings, and the extent to which media narratives reinforce or challenge traditional roles. Applying WAD approach, the research assesses gendered agency in rural tourism economies and identifies policy gaps in government initiatives. Through a feminist realism lens, the study evaluates whether state-led programs result in meaningful empowerment or merely symbolic inclusion, where women are featured prominently yet lack real influence.

Two researchers (male and female) independently coded 20% of the dataset to pilot-test the codebook. Discrepancies (e.g., classifying “leadership” roles) were resolved through discussion. Cohen’s Kappa confirmed high agreement (κ = 0.92).

Quantitative text analysis (Krippendorff, 2019) was paired with image analysis (Rose, 2001) to capture both prevalence and nuanced gendered narratives. Following the data collection phase, statistical test including T-tests—to compare the frequency of male/female portrayals (text versus images), Kruskal-Wallis Test – for investigating the difference in gender representation across countries, Chi-square – for comparing gender framing in different themes (socio-cultural, political, economic), McNemar’s Test – for comparison men/women in different roles, Mann–Whitney U Test – for country-level comparisons. These tests would provide the comprehension picture of gender framing on the DMOs in GMS. Besides that, qualitative analysis (with the software NVivo) for the depth insights of the gender representation, the stereotype gender roles and the grassroot reasons for the difference in gender framing.

This methodological approach highlights the dynamic relationship between government-mediated tourism narratives and sociocultural representations of gender. While the study provides valuable insights into institutional portrayals, it also identifies key limitations, such as the exclusion of local languages and grassroots perspectives, that warrant further investigation. Subsequent research should expand beyond state-sanctioned sources to incorporate community voices, multilingual content, and alternative media platforms, thereby offering a more comprehensive understanding of gender dynamics in Mekong Delta agritourism. Regarding to the ethical concerns, this study used publicly available DMOs content, therefore no formal Institutional Review Boards approval was sought, as the study did not involve human subjects directly. Besides that, ethical issues were implicitly addressed by excluding identifiable individuals (e.g., close-up portraits without consent) and focusing on aggregated data rather than individual representation.

4 Results

4.1 Gender representation in textual and visual information

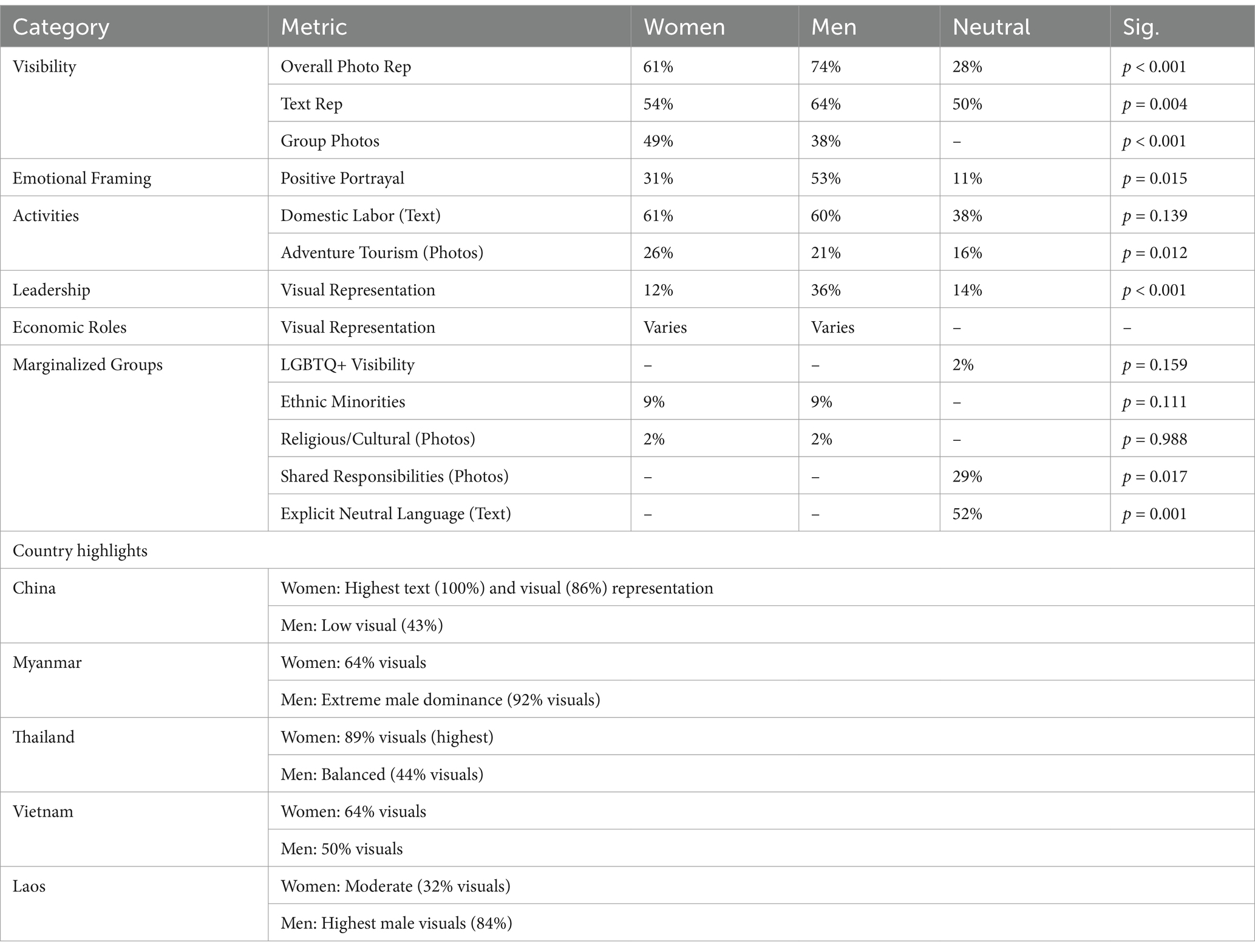

The textual and visual mentions of gender in each countries reveals a clear divide. Laos and Myanmar emphasize gender in both text (33%) and visuals (54–86%), while Thailand and Vietnam show moderate-low representation (1–12%). Yunnan demonstrate minimal engagement (9% text, 3% photos). Myanmar stands out with the most balanced high representation across both formats (33% text, 86% photos). When communicating about agritourism on government tourism websites, coverage of gender issues in textual information is less than visual data, except in Yunnan (China). This information is similar to the finding of Guilbeault et al. (2024) and Jaworska (2016). Chi-square test shows both women’s visibility and men’s visibility show statistically significant variation across countries. The p-values <0.05 confirm that gender representation is not independent of country context, media framing differs by location (Table 2). Besides that, Kruskal-Wallis Test (p = 0.000) also confirm that women’s visibility in rural tourism media is not uniform, some countries emphasize women more than others. In particular, China portrays women far more visibly than Laos, Thailand, Myanmar. China’s media consistently highlights women in rural tourism, possibly due to the roles of women in rural economy is increasing in that country (WAD perspective) (Chen and Barcus, 2024; Matthews and Nee, 2000). Lower visibility in Laos may reflect traditional gender norms in media, where men dominate tourism narratives (Flacke-Neudorfer, 2007), similar with Thailand (Çakmak and Çenesiz, 2020). Besides that, men’s visibility in agritourism media varies significantly by country, similar to women’s visibility but with different patterns. Myanmar portrays men far more visibly than China and Vietnam, could reflect the extremely male dominated society in this country (Minoletti, 2017). This pattern contrasts sharply with China’s low male visibility, where women are more highlighted. The significant results for both genders imply media actively constructs divergent roles for men/women.

In addition, there is a statistically significant difference in how men versus women are depicted in positive contexts. Women are more likely to be shown with culture ambassador such as smiling while wearing traditional clothes, leading cultural activities (for example, in Yunnan, Vietnam). Men are also positively framed but possibly in different contexts, such as in the meeting or when they are working (in Myanmar, Laos) Media reinforces the images of women as warm, welcoming hosts, while men is tied to productivity and achievement. Women are portrayed as positive sentiment but in passive roles also mentioned in many previous studies (Banaszkiewicz, 2014; Sirakaya and Sonmez, 2000).

Regarding to minority representation, media content related to agricultural tourism showcases minority communities at a rate of 9% in both gender, suggesting equal but low representation. Notably, in Thailand, images of transgender individuals are linked to tourism, whereas other countries in the region lack both visual and written representations of this community. Religious groups, particularly Buddhists, are consistently referenced at a rate of approximately 4% within the region. Additionally, the narratives surrounding agricultural tourism in the Mekong River Basin often adopt gender-neutral language when referring to individuals. Remarkably, up to 52% of gender-sensitive media content opts for gender-neutral terms when addressing people (see Table 2).

4.2 Gender representations across economic, political, and socio-cultural themes

There is no significant difference in portrayal of women versus men in labor roles (p = 0.139) (Table 2). Both genders are depicted in work duties, but the type of labor differs. Men are portrayed in the important, high paid job such as “chef,” “shop owner,” “presidents” while women are portrayed more frequent in the less paid position such as “embroidered craft work,” “coffee picking” or” performer.” Regarding to the tourists role, men are more likely to be depicted as adventurous tourists (p = 0.012). On the other hand, examining with (Kruskal-Wallis Test), when being portrayed as a tourists, there is strong cross-country variation in women representation (p = 0.000) and significant but less pronounced in men representation (p = 0.041). In particular, China as the lowest as China’s media rarely depicts women in leisure, aligns with its focus on women as economic actors. Another noticeable information is shared responsibilities between two genders are rare (29%).

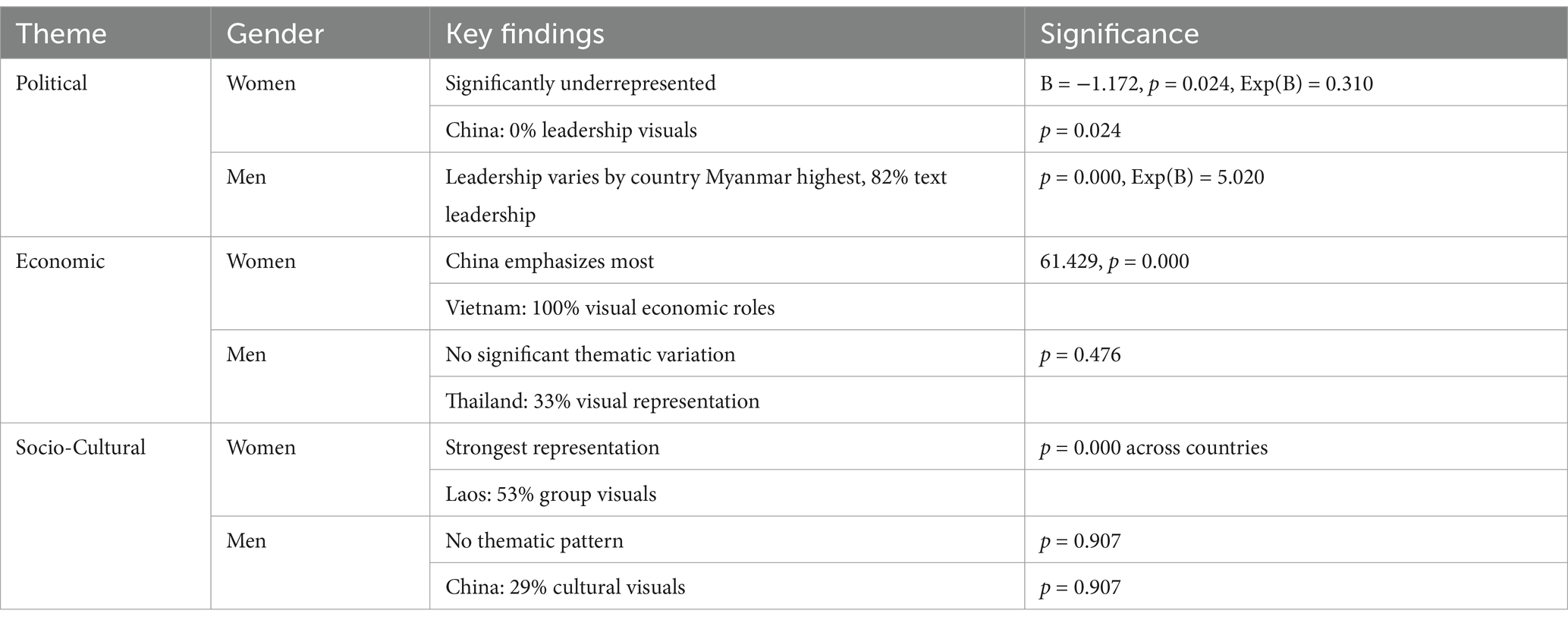

However, while women may be visible, they are portrayed in passive symbols in many countries. For example, in Vietnam, women is mentioned in the passive role as “the wife,” or the female coffee pickers in the farm. In Thailand, women is rarely mentioned but when they were mentioned, the are placed in positive view, such as “the star in the kitchen is the owner’s mother” or “well-trained granddaughter.” They also mentioned as the shop owners or the founder of a business group. In Yunnan (China), women is featured as the one who preserved traditional culture, such as “Wa ethnic women in traditional costumes,” or “the clothes of Huayaodai women are gorgeous.” However, they also linked with gender roles such as the one who washing clothes or vegetables, who welcomes guests or who makes the cake. This finding aligns with a previous study that suggests women are portrayed as a more submissive gender in visual media compared to textual descriptions (Guilbeault et al., 2024). Laos, on the other hand, has positive images of women, as the expert “she is also an ecologist and environmental journalist,” or women take up to half of the tourism workforce. On the contrary, fewer articles mention men, but when they do, roles are rigid. For example, in Thailand, majority of article mentions about men in the important role, such as the chef, “the businessman, the restaurant owner, or the founder of a business chain, similar with Myanmar, where the men is mentioned in political important position such as “union minister,” or “deputy minister.” In Laos, the men is also mentioned as an important person, such as “chairman,” “president” or “minister,” similar with Vietnam, where the man is rarely mentioned but when they do, they are connected with important position such as “famous artist.” In Yunnan (China), men is described as the peer with women, who do works together, like “men and women drag wood together” or “Hani women are busy making Ciba (Rice Cake), while Hani men cut bamboo and set up swings” However, in some circumstance, men also take the important role, such as “men take the lead on the first day of the new year.” Furthermore, according to Table 3, the difference between man and women in political themes show significant disparity (p < 0.001). The result suggests women are systematically excluded from agritourism narratives tied to power, policy, or leadership, aligning with feminist realism critiques of structural inequality. As the reference category, socio-cultural themes likely dominate coverage, potentially reinforcing traditional gender roles. This finding is similar to the findings of Mwinnoure and Dzitse (2024) on ecotourism in Ghana. Research indicates that women remain significantly underrepresented in decision-making roles within the tourism industry, frequently holding only a small proportion of senior positions compared to their male counterparts (Adnyani et al., 2021; Gutierrez and Vafadari, 2023).

Furthermore, Table 3 reveals stark gender disparities in rural tourism representations across the Mekong Subregion. Politically, women are significantly underrepresented (B = −1.172, p = 0.024), with China showing 0% visual depictions of female leadership, while men dominate, especially in Myanmar (82% textual leadership references, p = 0.000). Economically, women’s roles are highlighted more prominently, particularly in China (p = 0.000) and Vietnam (100% visual economic roles), whereas men show no significant thematic variation (p = 0.476). Socio-culturally, women are the most consistently represented (p = 0.000), with Laos depicting them in 53% of group visuals, while men’s representation lacks thematic coherence (p = 0.907). This observation suggests the leadership bias in men, women’s economic visibility is foregrounded in certain countries (Vietnam, China), and women are homogenized as “cultural bearers” in all examined countries.

In general, for RQ1, the analysis reveal limited gender-equality representation on Mekong Subregion DMOs, with women often depicted as laborers but rarely as decision-makers, while men dominate political and leisure narratives. Yunnan (China) and Vietnam lead in women’s visibility, reflecting their strong agricultural roles, whereas Laos and Myanmar show significant gaps. Thailand presents moderate balance but still associates women with economic roles and men with political power. Minority representation remains low, with Thailand uniquely including transgender imagery, while gender-neutral language appears in 50% of gender-sensitive content. These findings highlight a disconnect between women’s economic participation and their portrayal in leadership.

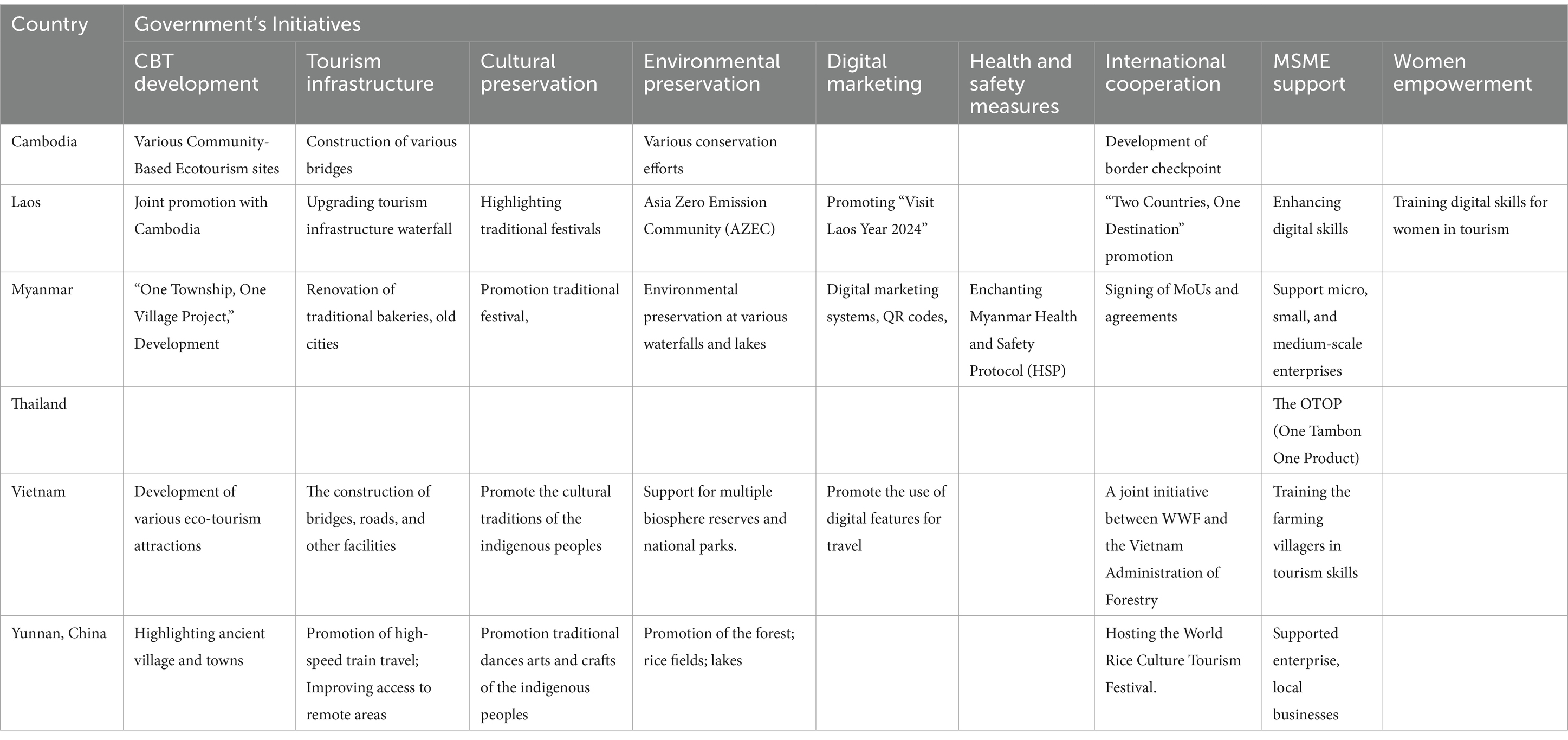

4.3 The government’s initiatives for gender equality in development on the websites

Table 4 reveals that while Laos and Vietnam explicitly include women in tourism development (e.g., Laos’ digital skills training for women and Vietnam’s farming village upskilling) Cambodia and Thailand omit gendered strategies despite CBT growth. For instance, in Cambodia, Community-Based Ecotourism initiative documentation lack documented female leadership, mirroring previous observations that CBT often invisibilizes women’s labor (El-Manhaly and Taha, 2024; Jackson, 2025; McCall and Mearns, 2021). Similarly, Thailand’s OTOP (One Tambon One Product) program promotes MSMEs but does not address structural barriers for women entrepreneurs in rural tourism, although their contribution for this program have been demonstrated in many previous documents (Acharya, 2019; Tamrongterakul and Ocha, 2021). Although the initiatives do not explicitly encourage gender equality, various studies have suggested that community-based training (CBT) can indirectly enhance employment opportunities for women and enable them to assume leadership positions within their local economies (McCall and Mearns, 2021; Vujko et al., 2024). Furthermore, ecotourism has demonstrated its potential to contribute positively to the psychological, social, and economic development of women in the region (Mwinnoure and Dzitse, 2024; Xaba and Adanlawo, 2024). Similarly, the Yunnan region of China has introduced various programs to develop ancient villages and towns. This type of tourism fosters significant community involvement, empowering women and amplifying their voices within the community (Liu, 2022). The region has been a focal point for various governmental initiatives supporting indigenous communities.

Laos may have fewer initiatives than neighboring countries like Vietnam and Cambodia, but these initiatives are diverse and span multiple fields. One notable effort highlighted on the country’s website is to empower women by equipping them with digital skills in the tourism sector. This initiative seeks to connect local tourism products to the global market. Previous research indicates that integrating digital technologies significantly enhances the visibility and marketing of women-led enterprises on social media and various online platforms (Acharya, 2023; Sujarwo et al., 2022). According to Table 4, Vietnam has introduced an initiative to equip farming communities with essential skills in tourism, basic English, and marketing. While the primary focus of this initiative is not specifically on women, they are considered an integral part of the target audience.

Conversely, Thailand’s website emphasizes the introduction of restaurants, eateries, shops, hotels, and resorts to domestic and international tourists. As a result, only one initiative is highlighted, which is OTOP. Launched in 2001, this program aims to stimulate the local economy by encouraging the 7,255 tambon (sub-districts) in Thailand to produce and market distinctive products from their regions, ultimately enhancing the tourism experience (Sitabutr and Pimdee, 2017). The initiative has played a vital role in creating markets for rural products through tourism channels, enhancing rural communities’ incomes, and attracting tourists who seek authentic cultural tourism experiences (Manirojana, 2022). While not explicitly stated, this program is frequently highlighted by researchers for its positive impact on women’s empowerment. For instance, it stimulates the local economy and fosters women’s empowerment through capacity-building and skills training, thereby enhancing their status and capabilities within the community (Nitsch and Vogels, 2022; Sitabutr and Pimdee, 2017).

For answering RQ2, government and DMOs initiatives for gender equality appear inconsistently across Mekong Subregion tourism websites, with most programs. However, CBT (Cambodia, Vietnam) and ecotourism initiatives, while not gender-specific, demonstrate measurable impacts on women’s economic participation and leadership, aligning with SDG 5 targets. Yunnan (China) stands out for its ancient village programs that actively amplify women’s voices, whereas Thailand’s OTOP initiative, though not gender-focused, has inadvertently empowered women through local product markets. These gaps suggest a need for DMOs to explicitly link policies to gender outcomes in their communications, ensuring visibility matches on-the-ground progress.

5 Conclusion

This study examines gender representation in rural tourism marketing across the Mekong Subregion, revealing significant disparities in how women and men are portrayed on official Destination Management Organization (DMO) websites. China’s Yunnan province emerges with particularly high visibility of women, significantly surpassing portrayals in Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar. The opposite trend appears in Myanmar’s coverage, where male visibility dominates the tourism narrative, as this disparity likely mirrors the country’s traditionally male-dominated social structures. Besides that, women are predominantly depicted as “cultural ambassadors” or low-wage laborers, whereas men occupy political and high-status positions. This underrepresentation of women in political narratives reinforces patriarchal norms, despite their visible economic participation in rural tourism. Additionally, ethnic minority and transgender communities remain marginally represented. While Laos emphasizes women’s economic training initiatives, Cambodia and Thailand lack gender-specific strategies, even though programs like Thailand’s OTOP have demonstrably benefited women. Although ecotourism and community-based tourism (CBT) indirectly empower women, DMO communications fail to explicitly address gender equity.

This study has several limitations, including its reliance on English-language DMO content, which excludes local-language narratives and grassroots perspectives. The focus on institutional media also overlooks participatory platforms such as social media and community-led campaigns. To advance Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 on gender equality, the Mekong Subregion must shift from symbolic inclusion to structural transformation in rural tourism development. By prioritizing women’s agency in policy and media representation, DMOs can position rural tourism not only as an economic driver but also as a platform for social justice, ensuring the region’s cultural diversity aligns with its commitment to inclusivity. Future research should expand beyond official media to analyze alternative sources (e.g., influencer content, NGO reports) to better understand narrative disparities. Incorporating grassroots perspectives is essential to bridge the gap between media portrayals and on-the-ground realities. Longitudinal studies tracking the impact of policy interventions on women’s empowerment would further strengthen these initiatives. Additionally, more research is needed to explore how ethnicity, class, and rurality intersect with gender in tourism media representations.

6 Theoretical implications

These above results lead to three significant implications. First of all, under the media framing framework, the information on DMOs across nations and regions in GMS consistently frames women within cultural/domestic roles and men as economic leaders or tourists, perpetuating traditional stereotypes. In particular, in China, the website highlight the role of women as “cultural bearers” or economic agents may reflect state-controlled narratives celebrating rural development, yet men are depoliticized in agritourism discourse. In Laos and Thailand, women’s labor is often erased in favor of male-dominated development narratives. Myanmar focus on masculinity society men as innovators and political leaders, reinforcing patriarchal governance norms. In addition, positive portrayals of women often mask their exclusion from decision-making roles. Second, under the lens of Feminist Realism, disparities in leadership highlight systemic inequities in rural tourism governance, particularly in patriarchal social systems or the development of society (the case of China). Besides that, media normalizes gendered suffering (low paid jobs; glass celling paradox) without critiquing systemic causes. In China, high female economic visibility without mentioning male political invisibility, suggesting state propaganda co-opts “empowerment” imagery without challenging patriarchy. On the contrary, Myanmar high-visibility of men in politics reflects institutionalized gender hierarchies. Third, applying the WAD approach, women’s economic participation is often confined to low-value sectors, while men dominate entrepreneurship may reflect the problem of “add women and stir” (Dharmapuri, 2011) in WAD approach, which adding visibility without structural change. Besides that, high labor visibility of women in Southeast Asia countries romanticizes poverty rather than addressing transformative empowerment. There are mentions of government initiatives to uplift the women empowerment but there are the need for more active strategies. Finally, compound marginalization of ethnic minorities and LGBTQ+ individuals further exposes the limits of WAD’S universalist assumptions.

7 Practical implications

Based on the findings, the following practical solutions are proposed to enhance gender-inclusive tourism communication in GMS, particularly in rural tourism. These suggestions are also the answer for RQ3.

7.1 Increase gender-sensitive content in text and visuals

Government tourism websites should deliberately incorporate more gender-related discussions in textual content while maintaining balanced visual representations. Given that visuals currently outperform text in gender representation, integrating narratives that highlight women’s leadership, economic contributions, and decision-making roles can counteract existing biases. Unlike generic diversity policies (UNWTO, 2022a), this approach tailors content to regional disparities, ensuring Laos and Myanmar improve representation while Vietnam and Yunnan (China) maintain their progress.

7.2 Promote women in leadership and political narratives

Since men dominate political and decision-making themes, tourism media should actively feature women in these roles, showcasing female entrepreneurs in rural tourism, policymakers, and community leaders. Case studies and interviews can reinforce this shift. While existing direct initiatives, such as Laos’ digital skills program for women, should focus on capacity-building, media representation remains passive. A proactive framing strategy, as suggested by framing theory, would amplify real-world progress in perception.

7.3 Strengthen gender-neutral language with thematic balance

Although 50% of content already uses gender-neutral terms, this should extend to thematic areas where stereotypes persist, especially in political information. For English language, the global could be utilized (EIGE, 2019; UNDP, 2015), but for the local language in the GMS, there would be initiatives and funding to support for developing similar toolkits.

7.4 Highlight women’s contributions to sustainability

Women are portrayed positively in economic and social sustainability, a strength that should be leveraged. Tourism campaigns could spotlight women-led eco-tourism projects or indigenous farming practices. Thailand showed balanced representation aligns with global best practices. Besides that, China with the highlight of women’s role in rural economic development could be a model for other countries in the region.

7.5 Integrate empowerment initiatives into tourism marketing

There should be more direct linked gender empowerment programs, similar with Laos’ digital training, to tourism promotions. Feature success stories of women benefiting from these initiatives to inspire participation and investment. This initiatives outcomes should be specific such as number of media representation, number of engagements, help to creating a feedback loop that reinforces real-world impact.

7.6 Regional collaboration for consistent standards

Establish a GMS-wide working group to share best practices and address gaps. A unified gender-inclusion guideline for rural tourism content could harmonize disparities. While there are policy in ASEAN focus on gender in tourism (Secretariat, 2020), a sub-regional focus on rural tourism would be more actionable.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Author contributions

MH: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TM: Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2025.1596789/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

GMS, Greater Mekong Subregion; WAD, Women and Development Approach; DMOs, Destination marketing organizations; CBT, Community-based tourism; LGBTQ+, Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual/aromantic.

References

Abdullah, F. N. A., and Hamid, N. A. (2024). Portrayals of rural Women’s empowerment in online news reporting. Int. J. Law Gov. Commun. 8, 76–91. doi: 10.35631/IJLGC.833007

Acharya, J. (2019). Lessons for women group enterprises management from one Tambon one product rural development Programme in Thailand. Vidyasagar Univ. J. Econ. 24, 68–83.

Acharya, S. (2023). Tourism as a tool of women empowerment: a general review. Res. Nepal J. Dev. Stud. 6, 101–106. doi: 10.3126/rnjds.v6i1.58928

ADB (2022) Greater Mekong Subregion Gender Strategy. Asian Development Bank. doi: 10.22617/tcs220441-2

Adnyani, N. K. S., Windia, I. W., and Sukerti, N. N. (2021). Tourism policy, Purusa culture, and gender inequality in absorbing women’s employment. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 10, 285–294. doi: 10.20525/ijrbs.v10i6.1331

Alampay, R. B. A., and Rieder, L. G. (2008). Developing tourism in the greater Mekong Subregion economic corridors. J. GMS Dev. Stud. 4, 59–75.

Alarcón, D. M., and Cole, S. (2019). No sustainability for tourism without gender equality. J. Sustain. Tour. 27, 903–919. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2019.1588283

Araújo-Vila, N., Otegui-Carles, A., and Fraiz-Brea, J. A. (2021). Seeking gender equality in the tourism sector: a systematic bibliometric review. Knowledge 1, 12–24. doi: 10.3390/knowledge1010003

Arroyo, C. G., Barbieri, C., Sotomayor, S., and Knollenberg, W. (2019). Cultivating Women’s empowerment through Agritourism: evidence from Andean communities. Sustainability 11:3058. doi: 10.3390/su11113058

Ayazlar, G., and Ayazlar, R. A. (2015). “Rural tourism: A conceptual approach,” in Tourism, Environment and Sustainability, ed. C. Avcikurt St. Kliment Ohridski University Press. 167–184.

Banaszkiewicz, M. (2014). Images of women in tourist catalogues in semiotic perspective. Turystyka Kulturowa [Preprint]. Available online at: https://ruj.uj.edu.pl/server/api/core/bitstreams/cfd7f015-0451-41b5-b19c-8026c236b5c7/content

Bhatta, K., and Ohe, Y. (2020). A review of quantitative studies in Agritourism: the implications for developing countries. Tour. Hosp. 1, 23–40. doi: 10.3390/tourhosp1010003

Bianchi, R. V., and Man, F. D. (2021). Tourism, inclusive growth and decent work: a political economy critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 29, 353–371. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1730862

Biddulph, R. (2020). Tourism and southeast Asian rural livelihood trajectories: the case of a large work integration social enterprise in Siem Reap, Cambodia. J. Qual. Res. Tour. 1, 73–92. doi: 10.4337/jqrt.2020.01.04

Binetti, M. J. (2019). En torno a un nuevo realismo feminista como superación ontológica del constructivismo sociolingüisticista. Debate Feminista 58, 76–97. doi: 10.22201/cieg.2594066xe.2019.58.04

Bouchon, F., and Rawat, R. (2016, 2016). Rural areas of ASEAN and tourism services, a field for innovative solutions. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 224, 44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.398

Brahma, S. M. (2022). “Women in the development narrative,” in Women empowerment a need of hour. eds. N. W. Patil and Muthmainnah Delhi: Akshita Publishers and Distributors.

Çakmak, E., and Çenesiz, M. A. (2020). Measuring the size of the informal tourism economy in Thailand. Int. J. Tour. Res. 22, 637–652. doi: 10.1002/jtr.2362

Campos-Soria, J. A., Marchante-Mera, A., and Ropero-García, M. A. (2011). Patterns of occupational segregation by gender in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 30, 91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.07.001

Chen, Z., and Barcus, H. R. (2024). The rise of home-returning women’s entrepreneurship in China’s rural development: producing the enterprising self through empowerment, cooperation, and networking. J. Rural. Stud. 105:103156. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2023.103156

Chhabra, D., Andereck, K., Yamanoi, K., and Plunkett, D. (2011). Gender equity and social marketing: an analysis of tourism advertisements. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 28, 111–128. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2011.545739

Chong, D., and Druckman, J. N. (2007). Framing theory. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 10, 103–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054

Cole, S. (2017). Water worries: an intersectional feminist political ecology of tourism and water in Labuan Bajo, Indonesia. Ann. Tour. Res. 67, 14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2017.07.018

Damavandi, G. A., Mohammadkazemi, R., and Sajadi, S. M. (2022). The impact of social media marketing on brand equity considering the mediating role of brand experience and social media benefits. J. Int. Bus. Manag. 5, 1–12. doi: 10.37227/aricon-jibm-2022-11-6739

Díaz-Carrión, I. A., and Vizcaino-Suárez, P. (2019). Tourism and gender research in Brazil and Mexico. Tour. Cult. Commun. 19, 277–289. doi: 10.3727/194341419X15542140077530

Diep, D. T., and Duong, P. B. (2022) Sustainable development of rural tourism in emerging economies in Asia: theoretical considerations and empirical aspects from Vietnam. In: Proceeding of Contemporary Economic Issues in Asian Countries. Singapore: Springer. 2022, pp. 411–434.

Dong, H., and Khan, M. S. (2023). Exploring the role of female empowerment in sustainable rural tourism development: an exploratory sequential mixed-method study. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 8, –e01651. doi: 10.26668/businessreview/2023.v8i4.1651

Dung, L. N. T., Loi, N. A., Phat, S. N., Nguyen, D. H. L., and Nguyen, Q. N. (2023). Factors impacting destination attractiveness of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. J. Law Sustain. Dev. 11:e1502. doi: 10.55908/sdgs.v11i11.1502

EIGE (2019). Toolkit on gender-sensitive communication. Luxembourg: European Institute for Gender Equality.

El-Manhaly, S., and Taha, s. (2024). The effect of community-based tourism on woman empowerment to achieve sustainable development: the case of Nuba. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Stud. 6, 87–107. doi: 10.21608/ijthsx.2024.275396.1081

Fajri, D. N. A., Damanik, J., Priyambodo, T. K., and Sutikno, B. (2022). “Actor’s role in developing creative rural tourism Marketing in the Digital era: a case study in Ponggok, Central Java” in Post pandemic tourism: trends and future directions. Atlantis Press. 278–292.

Ferguson, L. (2011). Promoting gender equality and empowering women? Tourism and the third millennium development goal. Curr. Issue Tour. 14, 235–249. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2011.555522

Ferguson, L., and Alarcón, D. M. (2015). Gender and sustainable tourism: reflections on theory and practice. J. Sustain. Tour. 23, 401–416. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2014.957208

Figueroa-Domecq, C., and Segovia-Perez, M. (2020). Application of a gender perspective in tourism research: a theoretical and practical approach. J. Tour. Anal. 27, 251–270. doi: 10.1108/JTA-02-2019-0009

Flacke-Neudorfer, C. (2007). Tourism, gender and development in the third world: a case study from northern Laos. Tour. Hosp. Plann. Dev. 4, 135–147. doi: 10.1080/14790530701554173

Frohlick, S., and Macevicius, C. (2023). Listening otherwise: from “silent tourism” soundscapes to privileged sonic ways of knowing. Tour. Stud. 23, 149–173. doi: 10.1177/14687976231171713

Funk, M., and Pashkevich, A. (2020). Representations of industrial heritage in tourism marketing materials: Analysing androcentric discourse in textual and visual content. Dos Algarves Multidiscip. J. 36, 41–58. doi: 10.18089/damej.2020.36.3

Ghanian, M., Ghoochani, O., and Crotts, J. (2017). Analyzing the motivation factors in support of tourism development: the case of rural communities in Kurdistan region of Iran. J. Sustain. Rural Dev. 1, 137–148. doi: 10.29252/jsrd.01.02.137

Gia, B. H. (2021). Some solutions for sustainable agricultural tourism development in the Mekong Delta in Vietnam. E3S Web Conf. 234:00063. doi: 10.1051/e3sconf/202123400063

Giang, N. T. (2024). Promoting economic development through rural tourism in Vietnam. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Res. Manag. 8, 42–47.

Guilbeault, D., Delecourt, S., Hull, T., Desikan, B. S., Chu, M., and Nadler, E. (2024). Online images amplify gender bias. Nature 626, 1049–1055. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07068-x

Gutierrez, E. L. M., and Vafadari, K. (2023). Women in community-involved tourism enterprises: experiences in the Philippines. Asia Pac. Viewp. 64, 85–97. doi: 10.1111/apv.12361

Hai, N. C., and Ngan, N. T. K. (2022). Factors affecting community participation in Khmer festival tourism development in Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Geo J. Tour. Geosites 44, 1482–1490. doi: 10.30892/gtg.44436-968

Hallett, R. W., and Kaplan-Weinger, J. (2010). Official tourism websites, a discourse analysis perspective. Bristol, UK: Channel View Publications.

Hansen, T. (2020). Media framing of Copenhagen tourism: a new approach to public opinion about tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 84:102975. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.102975

Hau, P. X., and Tuan, V. A. (2017). The development of rural tourism in Vietnam – objectives, practical experiences and challenges. Van Hien Univ. J. Sci. 5, 189–200. doi: 10.58810/vhujs.5.2.2017.5216

He, J., and Mai, T. H. T. (2021). The circular economy: a study on the use of Airbnb for sustainable coastal development in the Vietnam Mekong Delta. Sustainability 13:7493. doi: 10.3390/su13137493

Hillman, W., and Radel, K. (2022). Transformations of women in tourism work: a case study of emancipation in rural Nepal. Gaze J. Tour. Hosp. 13, 27–49. doi: 10.3126/gaze.v13i1.42040

Ip, C., Law, R., and Andy, L. H. (2011). A review of website evaluation studies in the tourism and hospitality fields from 1996 to 2009. Int. J. Tour. Res. 13, 234–265. doi: 10.1002/jtr.815

Jabeen, S., Haq, S., Jameel, A., Hussain, A., Asif, M., Hwang, J., et al. (2020). Impacts of rural Women’s traditional economic activities on household economy: changing economic contributions through empowered women in rural Pakistan. Sustainability 12:2731. doi: 10.3390/su12072731

Jackson, L. A. (2025). Community-based tourism: a catalyst for achieving the United Nations sustainable development goals one and eight. Tour. Hosp. 6:29. doi: 10.3390/tourhosp6010029

Jaworska, S. (2016). A comparative corpus-assisted discourse study of the representations of hosts in promotional tourism discourse. Corpora 11, 83–111. doi: 10.3366/cor.2016.0086

Je, J. S., Yang, E. C. L., Khoo, C., and Lockstone-Binney, L. (2025). The effectiveness of gender equality initiatives in hospitality organizations: exploring the perceptions of organizational actors using critical realism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 128:104150. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2025.104150

Jin, W., Min, K., Hu, X., Li, S., Wang, X., Song, B., et al. (2024). Enhancing rural B&B management through machine learning and evolutionary game: a case study of rural revitalization in Yunnan, China. PLoS One 19:e0294267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0294267

Jun, J., and Oh, K. M. (2015). Framing risks and benefits of medical tourism: a content analysis of medical tourism coverage in Korean American community newspapers. J. Health Commun. 20, 720–727. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018574

Kuma, B., and Godana, A. (2023). Factors affecting rural women economic empowerment in Wolaita Ethiopia. Cogent Econ. Financ. 11:2235823. doi: 10.1080/23322039.2023.2235823

Lalisan, A. K., Fresnido, M. B. R., Ramli, H. R., Aung, A., Utama, A. A. G. S., and Ating, R. (2024). Empowering the ASEAN community through digitalization of agriculture for rural tourism development: an NVIVO analysis. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1366:012018. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/1366/1/012018

Li, L., Hazra, S., and Wang, J. (2023). A realist analysis of civilised tourism in China: a social structural and agential perspective. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 7:100411. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100411

Li, S., Saayman, A., Stienmetz, J., and Tussyadiah, I. (2022). Framing effects of messages and images on the willingness to pay for pro-poor tourism products. J. Travel Res. 61, 1791–1807. doi: 10.1177/00472875211042672

Liu, Y. (2022). “The importance of community participation on Ancient Village tourism development of China,” in 2022 7th International Conference on Financial Innovation and Economic Development, Atlantis Press (Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Financial Innovation and Economic Development (ICFIED 2022)), 3241–3244.

Lois, W. M., and Kenneth, R. O. (2018). The pulses of the Mekong River basin: Rivers and the livelihoods of farmers and fishers. J. Environ. Prot. 9, 431–459. doi: 10.4236/jep.2018.94027

Lončarić, D., Bašan, L., and Marković, M. G. (2013) Importance of Dmo websites in tourist destination selection. In: 23rd CROMAR Congress, Congress Proceedings: Marketing in a Dynamic Envinronment – Academic and Practical Insights, 2013. University of Rijeka.

Lyu, X., Hirsch, P., Kimkong, H., Manorom, K., and Tubtim, T. (2013). Cross-boundary peer learning in the Mekong: a case of field-based education in natural resources management. J. Contemp. Water Res. Educ. 150, 41–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1936-704X.2013.03134.x

Man, L., and Yu, W. (2024). Tourism advertising attribute framing effects on travel consumers’ visit intention. EUrASEANs J. Glob. Socio-Econ. Dyn. 3(46), 126–137. doi: 10.35678/2539-5645.3(46).2024.126-137

Manirojana, P. (2022). Public participation for promote Thai cultural tourism and the development of OTOP Nawatwitee for reduce social equality. Int. J. Health Sci. 6, 150–166. doi: 10.53730/ijhs.v6nS5.5214

Marchi, V., Lovrečić, K., and Brščić, K. (2023a). A comparison of official tourism websites in Tuscany region and Istria County using topic modelling : Tourism in Southern and Eastern Europe, 249–267.

Marchi, V., Marasco, A., and Apicerni, V. (2023b). Sustainability communication of tourism cities: a text mining approach. Cities 143:104590. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2023.104590

Matthews, R., and Nee, V. (2000). Gender inequality and economic growth in rural China. Soc. Sci. Res. 29, 606–632. doi: 10.1006/ssre.2000.0684

McCall, C. E., and Mearns, K. F. (2021). Empowering women through community-based tourism in the Western cape, South Africa. Tour. Rev. Int. 25, 157–171. doi: 10.3727/154427221X16098837279967

Mooney, S. K. (2020). Gender research in hospitality and tourism management: time to change the guard. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 32, 1861–1879. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-09-2019-0780

Müller, S., Huck, L., and Markova, J. (2020). Sustainable community-based tourism in Cambodia and tourists’ willingness to pay. Austrian J. Southeast Asian Stud. 13, 81–101. doi: 10.14764/10.aseas-0030

Munar, A. M. (2017). To be a feminist in (tourism) academia. Anatolia 28, 514–529. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2017.1370777

Mura, P., and Sharif, S. P. (2015). Exploring rural tourism and sustainability in Southeast Asia through the lenses of official tourism websites. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 7, 440–452. doi: 10.1108/WHATT-06-2015-0025

Mwinnoure, M. K., and Dzitse, C. D. (2024). Empowering women through ecotourism: a case study of women’s involvement in the Wachau hippo sanctuary project in Ghana. J. Multidiscip. Acad. Tour. 9, 259–272. doi: 10.31822/jomat.2024-9-3-259

Nair, V., Hamzah, A., and Musa, G. (eds). (2023). Responsible Rural Tourism in Asia. Channel View Publications (Tourism Geographies).

Nga, V. H. T. (2024). Some recommendations in tourism development to adapt to climate change in the Mekong Delta. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Growth Eval. 5, 898–904.

Nitsch, B., and Vogels, C. (2022). Gender equality boost for regenerative tourism: the case of Karenni village Huay Pu Keng (Mae Hong Son, Thailand). J. Tour. Futures 8, 375–379. doi: 10.1108/JTF-01-2022-0032

Omar, A. M., Hassan, S. B., and Wafik, G. M. (2022). Evaluating the impact of DMO websites on Travellers’ attitudes toward tourism destination selection: a case study of Fayoum governorate. Int. J. Herit. Tour. Hosp. 16, 14–25. doi: 10.21608/ijhth.2022.309514

Opoku, E. K., Wimalasena, L., and Sitko, R. (2024). Sexism and workplace interpersonal mistreatment in hospitality and tourism industry: a critical systematic literature review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 53:101285. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2024.101285

Panić, A., Vujko, A., and Knežević, M. (2024). Economic indicators of rural destination development oriented to tourism management: the case of ethno villages in Western Serbia. Menadžment u hotelijerstvu i turizmu 7. doi: 10.5937/menhottur2400006P

Parasnis, S. (2022) Representations of women and gender relations in Jamaican tourism promotional marketing: an analysis of visual images on Jamaica’s national DMO website. Lund University.

Peña-Sánchez, A. R., Ruiz-Chico, J., Jiménez-García, M., and López-Sánchez, J. A. (2020). Tourism and the SDGs: an analysis of economic growth, decent employment, and gender equality in the European Union (2009–2018). Sustainability 12:5480. doi: 10.3390/su12135480

Phuong, N. H. (2019). Advantages and challenges for tourism in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 8, 1364–1368. doi: 10.29322/IJSRP.8.9.2018.p8157

Picazo, P., and Moreno-Gil, S. (2019). Analysis of the projected image of tourism destinations on photographs: a literature review to prepare for the future. J. Vacat. Mark. 25, 3–24. doi: 10.1177/1356766717736350

Quang, T. D., Tran, N. M. P., Sthapit, E., Thanh Nguyen, N. T., Le, T. M., Doan, T. N., et al. (2024). Beyond the homestay: Women’s participation in rural tourism development in Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Tour. Hosp. Res. 24, 499–514. doi: 10.1177/14673584231218103

Rae, M., and Diprose, K. (2024). Bush Podpreneurs: how rural women podcast producers are building digital and social connectivity. J. Radio Audio Media ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 1–20. doi: 10.1080/19376529.2024.2328690

Ricke, F. (2022) Review of gender and development paradigms: illustrative examples from a rural Kenyan context. University of South Florida.

Rodrigues, S., Correia, R., Gonçalves, R., Branco, F., and Martins, J. (2023). Digital Marketing’s impact on rural destinations’ image, intention to visit, and destination sustainability. Sustainability 15:2683. doi: 10.3390/su15032683

Rosalina, P. D., Dupre, K., and Wang, Y. (2021). Rural tourism: a systematic literature review on definitions and challenges. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 47, 134–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.03.001

Rose, G. (2001). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual methodologies. Great Britain: Sage Publications Ltd.

Santosh, S., Shubham, G., and Hiba, M. (2023). Unveiling the contrasts between rural tourism and agro-tourism. Agri Great Britain. 5, 51–58.

Saputri, G. M. (2021). How women Lead podcast series: feminist media framing in challenging symbolic annihilation of Indonesian women leadership. Salasika Indones. J. Gend. Women Child Soc. Incl. Stud. 4, 81–94. doi: 10.36625/sj.v4i2.78

Satriya, C. Y., Wahyuni, H. I., and Sulastri, E. (2024). A framing analysis of Indonesian newspaper on the issue of community-based tourism in Magelang. Jurnal Visi Komunikasi 23, 213–238. doi: 10.22441/visikom.v23i02.30637

Secretariat (2020). The ASEAN (2020) ASEAN Gender and Development Tourism Framework and Work Plan2020-2030. Indonesia: Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

Senyao, S., and Ha, S. (2022). How social media influences resident participation in rural tourism development: a case study of Tunda in Tibet. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 20, 386–405. doi: 10.1080/14766825.2020.1849244

Singh, A. S. (2007). Agriculture and rural development in the greater Mekong sub-region the important Nexus. Policy brief. Hanoi, Vietnam: CUTS Hanoi Resource Centre.

Sirakaya, E., and Sonmez, S. (2000). Gender images in state tourism brochures: an overlooked area in socially responsible tourism marketing. J. Travel Res. 38, 353–362. doi: 10.1177/004728750003800403

Sitabutr, V., and Pimdee, P. (2017). Thai entrepreneur and community-based enterprises’ OTOP branded handicraft export performance. SAGE Open 7:2158244016684911. doi: 10.1177/2158244016684911

Sithirith, M. (2021) River Basin management – sustainability issues and planning strategies. IntechOpen Limited.

Soulard, J., Stewart, W., Larson, M., and Samson, E. (2023). Dark tourism and social mobilization: transforming travelers after visiting a holocaust museum. J. Travel Res. 62, 820–840. doi: 10.1177/00472875221105871

Statista (2024a) Agriculture – Southeast Asia. Statista market forecast. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/outlook/io/agriculture/southeast-asia (accessed March 1, 2025).

Statista (2024b) Travel & Tourism – Cambodia. Statista market forecast. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/outlook/mmo/travel-tourism/cambodia (accessed March 1, 2025).

Statista (2024c) Travel & Tourism – Laos. Statista market forecast. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/outlook/mmo/travel-tourism/laos (accessed March 1, 2025).

Statista (2024d) Travel & tourism – Thailand. Statista market forecast. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/outlook/mmo/travel-tourism/thailand (accessed March 1, 2025).

Statista (2024e) Travel & Tourism – Vietnam. Statista market forecast. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/outlook/mmo/travel-tourism/vietnam (accessed March 1, 2025).

Stoleriu, O. M. (2016). “Gendered constructions of Romania’s tourist destination image,” in WLC 2016: World LUMEN Congress. Logos Universality Mentality Education Novelty 2016. 965–974. doi: 10.15405/epsbs.2016.09.120

Su, M. M., Wang, M., Wall, G., Liu, Z., Dong, H., and Zhang, M. (2024). Gender equality in a Chinese rural tourism destination: perspectives of females and males. J. Sustain. Tour., 1–21.

Sujarwo, S., Tristanti, T., and Kusumawardani, E. (2022). Digital literacy model to empower women using community-based education approach. World J. Educ. Technol. Curr. Issues 14, 175–188. doi: 10.18844/wjet.v14i1.6714

Sulaj, A., and Themelko, H. (2024). Agritourism as a pathway to Women’s empowerment: insights from rural Albania. Eur. Countrys. 16, 628–646. doi: 10.2478/euco-2024-0032

Sullivan, K. (2023). Three levels of framing. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 14:e1651. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1651

Sun, Z. (2017). Exploiting femininity in a patriarchal postfeminist way: a visual content analysis of Macau’s tourism ads. Int. J. Commun. 11, 2624–2646.

Suradin, M. (2017). Halal tourism promotion in Indonesia: an analysis on official destination websites. J. Indones. Tour. Dev. Stud. 6, 143–158.

Tamrongterakul, S., and Ocha, W. (2021). “Empowering women for economic development: the case study of Thai fabrics women groups,” in RSU International Research Conference 2021. Rangsit University.

Thea, T., and Mardy, S. (2023). Agro-tourism development in Cambodia: a literature review | international journal of sustainable applied sciences. Int. J. Sustain. Appl. Sci. 1, 479–498. doi: 10.59890/ijsas.v1i5.826

UNDP (2015) Gender responsive national communications toolkit. Available online at: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/UNDP%20Gender%20Responsive%20National%20Communications%20Toolkit.pdf.

UNICEF (2017) Gender equality: Glossary of terms and concepts. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/rosa/media/1761/file/Genderglossarytermsandconcepts.pdf (accessed 28 February 2025).

UNWTO (2022a) Gender-inclusive strategy for tourism businesses. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284423262 (Accessed: March 15, 2025).

UNWTO (2022b) Regional report on women in tourism in Asia and the Pacific. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284423569 (Accessed: March 15, 2025).

Vujko, A., Karabašević, D., Cvijanović, D., Vukotić, S., Mirčetić, V., and Brzaković, P. (2024). Women’s empowerment in rural tourism as key to sustainable communities’ transformation. Sustainability 16:10412. doi: 10.3390/su162310412

Wang, Y. (2024). The “female-to-male” phenomenon in short videos: a feminist media analysis. Commun. Humanit. Res. 45, 15–20. doi: 10.54254/2753-7064/45/20240070

Weder, F., Lemke, S., and Tungarat, A. (2019). (re)storying sustainability: the use of story cubes in narrative inquiries to understand individual perceptions of sustainability. Sustainability 11:5264. doi: 10.3390/su11195264

Widiastini, N. M. A., Rosa, S. A. S., Putera, R. E., Susilowati, G., and Wibowo, T. H. (2021). The resilience of women tourism workers during the Covid-19 pandemic in Bali. Sosiohumaniora: Jurnal Ilmu-ilmu Sosial dan Humaniora 23, 372–379. doi: 10.24198/sosiohumaniora.v23i3.31556

Xaba, F., and Adanlawo, E. F. (2024). Are women empowered through ecotourism projects? A quantitative approach “ecotourism and women empowerment.”. Pak. J. Life Soc. Sci. 22, 3085–3092. doi: 10.57239/PJLSS-2024-22.1.00224

Yang, E. C. L., Khoo-Lattimore, C., and Arcodia, C. (2018). Constructing space and self through risk taking: a case of Asian solo female travelers. J. Travel Res. 57, 260–272. doi: 10.1177/0047287517692447

Zafar, M., Bashir, M. F., and Bukhari, A. A. A. (2024). Women’s empowerment and tourism: emerging determinants of poverty in low and middle-income countries. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 74, 1069–1085. doi: 10.1111/issj.12498

Zaim, I. A., Koesoemadinata, M. I. P., and Sari, S. A. (2022). Sundanese culture representation in tourism marketing: a visual content and semiotic analysis of website pictorial element. Asian J. Technol. Manag. 15, 224–234. doi: 10.12695/ajtm.2022.15.3.3

Keywords: gender representation, rural tourism, textual information, visual information, official websites, Mekong Subregion, cross-national analysis

Citation: Hoang M and Le Minh T (2025) Reframing gender in rural tourism: a cross-national analysis of official websites in the Mekong Subregion. Front. Commun. 10:1596789. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1596789

Edited by:

Tereza Semerádová, Technical University of Liberec, CzechiaReviewed by:

Noha Khalil, Matrouh University, EgyptKrishna Dhakal, International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Nepal

Airin Liemanto, Gadjah Mada University, Indonesia

Fani Efthymiadou, Boğaziçi University, Türkiye

Rindi Metalisa, Riau University, Indonesia