- 1Department of Communication, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- 2Leibniz University Hannover, Hanover, Germany

- 3Center for Strategic Studies, Tehran, Iran

Despite a growing body of research on intermedia agenda-setting (IAS) in the contemporary hybrid media landscape, this line of inquiry remains mainly Western-centered. Furthermore, there is a lack of studies across different social platforms and between social media and official online media in authoritarian regimes. We combined computational, quantitative, qualitative, and discursive methods to address these gaps by investigating intermedia agenda-setting between three popular social media in Iran (Twitter, Telegram, and Instagram) and official news websites during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our empirical analyses focused on four distinct datasets collected from January 27, 2020, to April 18, 2020. We find no significant influence between official and social media and no interplatform coupling among social networks, indicating platform-segmented agendas. While canonical health/news topics were common, contentious frames, notably Mismanagement and the politicization of hope and optimism, diverged sharply by platform. Taken together, these results show that in repressive settings, agenda cutting/suppression can decouple state and social spheres, and that user-base composition and platforms’ local trajectories, probably more than affordances or blocking alone, shape both intermedia and interplatform agenda independence. By providing a multi-platform, crisis-period map of agendas in Iran and demonstrating a directional test of influence under repression, the study refines IAS for non-democratic contexts and offers a transferable approach for comparative research on crisis communication.

Introduction

Intermedia agenda-setting (IAS) examines how the salience of issues in one medium conditions coverage in others within a hybrid media system where legacy outlets and social platforms interact over time (Djerf-Pierre and Shehata, 2017; McCombs et al., 2014; Vliegenthart and Walgrave, 2008; Wang and Shi, 2022). In democratic contexts, mainstream media often retain agenda leadership, with social media amplifying or refracting those cues; yet social platforms also inject alternative frames and, at times, operate with partial agenda independence (Asur et al., 2011; Han et al., 2021; Šķestere and Darģis, 2022). Authoritarian settings complicate these dynamics: censorship, propaganda, and agenda-cutting can decouple state-aligned outlets from public conversation, while platform affordances (e.g., Twitter’s open, hashtag-driven visibility; Instagram’s visuality; Telegram’s semi-closed channels) segment audiences and shape diffusion pathways (Highfield and Leaver, 2016; Lou et al., 2021; Theocharis et al., 2022).

COVID-19 created continuous and high-stakes information flows across countries, enabling cross-national comparisons while revealing regime-specific media controls. Iran, an authoritarian, theocratic hybrid regime, features tightly regulated official media and long-standing social-platform adoption as an alternative sphere. Twitter has been filtered since 2009; Telegram, widely adopted, was formally banned in 2018, though both remain in use via circumvention; Instagram was accessible during the first wave studied here (late January–mid-April 2020) and only filtered nationally in 2022 (Carafano, 2009; Faris and Rahimi, 2016; Kemp, 2020; Kermani, 2020; Kermani and Adham, 2021). Early in 2020, Iran became a regional COVID-19 hotspot, generating intense demand for timely news, health guidance, and policy information (Wolters et al., 2022). Prior work shows that first-wave coverage globally centered on core topics such as infection statistics, health instructions, government measures, alongside economic and political repercussions (Krishnatray and Shrivastava, 2021; Montiel et al., 2021; Tsao et al., 2021).

Despite growth in IAS scholarship, evidence remains predominantly Western-centric and mixed for authoritarian regimes (Guo, 2019; Shestopalova, 2023; Wang and Shi, 2022). We lack systematic analyses of (a) state–social agenda influence during a health crisis (beyond political upheavals), (b) interplatform agenda flow among social media under repression, and (c) how blocking, platform affordances, and audience composition/path dependence condition diffusion. Studies from China, Russia, and Turkey suggest that limited, issue-bounded spillovers can occur from social to state media; however, high-dissent topics are often cut or reframed (Belinskaya, 2021; Luo, 2014; Qaisar and Riaz, 2021; Zhou and Zheng, 2022). For Iran specifically, IAS work is scarce; existing evidence suggests weak state–public congruence and frequent agenda-cutting in official outlets (Minooie, 2019). Moreover, most non-democratic studies compare one platform to one outlet, leaving multi-platform social media interactions (such as Twitter, Telegram, and Instagram) underexplored.

This study presents a comprehensive account of social-media and official-media agendas in Iran during the initial COVID-19 wave, advancing IAS beyond democratic benchmarks in three key ways. Theoretically, it foregrounds agenda independence under repression, linking it to agenda-cutting, platform segmentation, and platforms’ local trajectories/user bases, not merely affordances. Empirically, it maps salient issue categories across Twitter, Telegram, Instagram, and official news websites in a period of acute public need, clarifying where agendas converge (e.g., canonical health/news themes) and where they diverge (e.g., mismanagement; politicization of hope). Conceptually, it reframes interplatform dynamics in authoritarian settings as a political variable, coexisting with censorship and propaganda, thereby informing comparative work across crises and regimes (Yang and Vicari, 2021).

Data and methods

We adopt a mixed-methods approach that aligns meaning, measurement, and dynamics in the study of IAS. Classical agenda-setting research combines surveys to capture the public’s agendas with content analysis to estimate media agendas (McCombs et al., 2014). The proliferation of social platforms and the availability of “big text” necessitate computational extensions, notably supervised machine learning (SML), to identify agendas at scale (Russell Neuman et al., 2014). Because SML performance depends on the quality of its labels (Jurafsky and Martin, 2020), we began with human-driven qualitative coding to produce a deliberately constructed training set (Burscher et al., 2014; Scharkow, 2013). This step secured semantic equivalence across outlets and platforms and yielded substantive insight into the qualitative structure of agendas. Using this gold-standard corpus, we then trained ParsBERT to label issues across Twitter, Telegram, Instagram, and official media, producing consistent, time-varying measures of issue salience. The combination of qualitative analysis and SML affords both close and distant vantage points, enhancing construct validity (via expert coding) and measurement reliability (via scalable, out-of-sample labeling). Finally, we estimated directional influence with transfer entropy, which detects information flows across media. This final stage is necessary to investigate the extent and direction of cross-media issue transfer during Iran’s COVID-19 period. All these steps are discussed in detail below.

Data collection and pre-processing

We used different tools to collect research data; academic API for Twitter, CrowdTangle for Instagram, and Telegram official API for Telegram. We also employed web mining to collect the official news media data. We collected data from January 27, 2020, to April 18, 2020, during the first wave of COVID-19 in Iran. We collected all data, e.g., tweets or Instagram posts, which included “Corona: کرونا” or their other variant in Persian as a keyword or hashtag. As a result, we collected 4,165,177 tweets, 5,355,902 Instagram posts, 12,957,051 Telegram posts, and 1,180,801 articles from official websites within the research timeframe.1 Then, we preprocessed the datasets by removing duplicates and non-Persian text. A large body of unnecessary data was removed, and the final datasets stand at 1,503,871 tweets, 9,056,643 Telegram posts, 3,540,340 Instagram posts, and 888,361 articles. From the cleaned text data, we selected weekly samples (500 instances per week) for human coding. As a result, we selected 6,000 units of each of the Twitter, Instagram, Telegram, and online media datasets in a ca. 12-week period. IAS is fundamentally temporal and dynamic, and in uncertain circumstances like COVID-19, issues discussed in the media change rapidly. Our weekly sampling ensures coverage of issue cycles and shocks throughout the research timeline. In addition, this approach provides sufficient precision to estimate weekly issue shares for seeding and auditing the classifier. Under simple random sampling, the 95% margin of error at is per week ; across the 12-week labeled set per medium), the corresponding margin is . This allocation balances annotation feasibility with an informative training signal: weekly labels capture both routine and spike weeks, while the cumulative yields a sufficiently large and diverse gold standard for fine-tuning ParsBERT.

Human-driven qualitative coding

We followed a rich textual approach to code the training datasets to maximize the accuracy and validity of the results. Three well-trained coders coded a random sample from each dataset, as explained above, following Braun and Clarke (2006). Their approach to thematic analysis includes coding the data, looking for patterns of meaning, identifying implicit and explicit ideas or themes, and reporting the content and meaning of patterns in the data.

Coders coded the samples in three consecutive steps: two inductive and one final deductive step. First, they coded 10 percent of each sample (600 instances of each dataset) to produce a primary codebook. We should mention that we only focus on news article headlines for analytical purposes. News headlines usually contain the most significant part of the news and can be used to gauge the most significant issue discussed. During this step, 71 open codes were identified. Coders discussed this codebook during this step as well as at the end of it. At the final meeting of this step, the open codes were culminated in 16 pattern codes. Having refined the codebook in this phase, coders used it to code another 10 percent of each sample. The second portion of the samples was different from the first 10 percent of the samples. Moreover, coders accumulated the pattern codes into 6 classes in this phase (5 main categories and the Other class).2 Then, they coded the main samples, including all units, whether coded in the previous steps or not, based on this codebook in a closed and deductive way. In the final round, all units were coded into two levels (pattern code and final class). We used the results from the final classes to train the model. At the final level, we identified six dominant categories in media in Iran during the pandemic: News and information (NI); Solidarity, hope, and optimism (SHO); Mismanagement; The virus, and health instructions (VHI); Fun, and others. Also, we used the results of open and pattern coding to provide discursive and qualitative interpretations. We calculated the intercoder reliability using Krippendorff’s alpha (Lombard et al., 2002). The intercoder reliability scores were satisfactory across all samples in the final round (Twitter: 0.83, Instagram: 0.82, Telegram: 0.85, online media: 0.92). Appendix 1 provides the codebook, including all pattern and final codes.

Text classification and active learning

In order to automatically identify the most potent method for classifying the large text datasets in this study, we analyzed several techniques like FastText, LSTM (Long short-term memory), Bi-LSTM, and BERT. This primary step revealed that the BERT language model (Devlin et al., 2019) works better to extract features from Persian text and utilize these features in a supervised fashion to learn a classifier. BERT is a powerful method developed on the basis of the transfer learning technique and uses transformers to analyze both the context and the flow of words. Out of all tested methods, BERT returned the highest F1 score. The average F1 score across all datasets was 58%.

Since the results of SML were unsatisfactory, we used ParsBERT as a more sophisticated method (Farahani et al., 2021). The primary results also showed the necessity of data augmentation through a more guided approach, like active learning. In the ParsBERT model, we employed a linear classification layer on top of BERT architecture and fine-tuned it over our annotated datasets. We used the Adam optimization algorithm to train the model. Our training hyperparameters are as follows: learning rate: 2e-5, batch size: 32, and epoch: 4. For validating and testing our model, we split the dataset into three sets: train, validation, and test, with 0.8, 0.1, and 0.1 of the dataset samples, respectively. The existing literature supports this approach, as it prevents data leakage from test to train during tuning and provides an unbiased estimate of generalization on an unseen test set (Jurafsky and Martin, 2020; Kohavi, 1995). The text-as-data approach also recommends train/validate/test splitting with human-coded seeds that supervise models subsequently to annotate large-N political text (Grimmer and Stewart, 2013; King et al., 2013).

For active learning, we combined weak labeling (e.g., heuristic labeling functions; Beñaran-Muñoz et al., 2018) with pseudo-labeling (Arazo et al., 2020). We first had the model assign provisional labels to 10,000 unlabeled items per dataset. These machine-labeled items were then audited and validated by human coders. To prevent over-representation of frequent categories, we capped class counts to balance the training set, and then retrained the model on this validated, class-balanced data. This human-in-the-loop refinement reduces label noise in ambiguous classes and improves generalization (Zhou, 2018). This step significantly improved the model’s accuracy. The F1 value for Twitter, Instagram, Telegram, and online media was raised to 0.72, 0.86, 0.88, and 0.71, respectively. The complete tables of SML results are presented in Appendix 2. Having classified all media datasets, we used transfer entropy to analyze their interplay.

Transfer entropy

We employed transfer entropy (TE) to examine the influence between social media and online news media. TE quantifies the directed predictive information from a source series X to a target series Y: intuitively, it asks whether knowing the past of 𝑋 reduces uncertainty about the future of Y beyond what is already explained by the past of Y. Formally, TE is the conditional mutual information T_{X → Y} = I(X_{t − ℓ:t − 1}; Y_t | Y_{t − ℓ:t − 1}), reported here in bits (log base 2). Larger values indicate stronger directed dependence; however, statistical significance is established through a null hypothesis that preserves each series’ own history (Vicente et al., 2011). To apply this method, we first computed the frequency of each issue in all datasets, using a 3-day lag to capture potential delayed influence. Transfer entropy was then estimated using the IDTxl library in Python, which implements an information-theoretic approach based on conditional mutual information. This method allowed us to assess the magnitude and direction of information transfer between datasets while accounting for dependencies in the time series.

Since we did not make a priori assumptions about the causal direction, we conducted bidirectional TE tests across all datasets, resulting in 12 tests in total. To assess whether an observed TE reflects more than chance co-movement, we use a surrogate (permutation) significance test that produces a p-value (Theiler et al., 1992). The test targets the exact inferential question: under a null in which the source adds no predictive information beyond the target’s own past, how often would a TE at least as large as the observed value occur? Surrogates are generated by reshuffling the source history in a way that preserves each series’ marginal distribution and serial dependence, ensuring validity for autocorrelated and non-linear time series (Theiler et al., 1992). Relying on the p-value provides a scale-free decision rule comparable across source to target pairs even when TE magnitudes differ, explicit control of false positives relative to a realistic, history-preserving null, and a clear link between statistical decision and the presence or absence of directional predictive information at the tested lags (here, 0–3 days).

Results

In this section, we present the identified issues in social and official media. Next, we discuss the extent to which the salient issues on social and official media were similar/different discursively and quantitatively. Finally, we provide the transfer entropy results and discuss the IAS between social and official media in Iran.

Media agendas during the pandemic

We identified five major issues on social media and news websites in Iran during the pandemic, plus an Other category. The first issue, News and information (NI), is an expected theme during crises. Such a theme was also identified in other countries during the COVID-19 crisis (Dada et al., 2021; Krishnatray and Shrivastava, 2021; Montiel et al., 2021; Wang and Shi, 2022). Wicke and Bolognesi (2020) embedded it in a news issue labeled Communications and Reporting. In addition, research on media agendas in Spanish and German outlets shows that such a news issue was dominant in both cases (Xu et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2020). As the label implies, people shared information and news about the pandemic, infected people, and what was happening.

Citizens and official websites also shared information about the virus symptoms and health instructions during the pandemic. Regarding the fact that the first wave of COVID-19 caused an uncertain state around the globe, people were in the dark. They were eager to receive more details about the symptoms as well as the ways they could avoid the virus or what they should do in case of infection. These reasons made VHI an important theme at that time. These two themes had a news nature. However, the next two were more interpretative. Iranian users developed a theme around good news and optimistic information to raise their spirits and encourage others. The main theme of SHO was defeating the virus. The other issue was mismanagement. Forming this theme, social media users, in particular, questioned the policies and control measures taken by the governments. This issue theme was mainly devoted to discussing who was guilty in the crisis and criticizing the decisions and activities that made the situation worse. Criticizing not quarantining the cities in Iran; the U. S, China, and other Western countries’ role in worsening the situation; the lack of medical supplies like face masks and sanitation gels; and the inability of Iran’s state to control the crisis were the main sub-themes of this frame.

The final theme was fun. People made jokes about the virus as well as other topics during the pandemic. All such messages were flagged as fun. Finally, we added a category of others. This category included many relevant and irrelevant messages. There were messages about the pandemic, but they could not be classified within the main themes. Also, the majority of them were not as much to form a new major theme. Furthermore, there were irrelevant messages. For instance, in some Instagram posts, users mentioned coronavirus as a hashtag just to promote the posts. These messages were identified as others. Nonetheless, the others category was not involved in our analysis.

In the next section, we discuss the frequency of each issue in different media.

The salience of issues across social and official media in Iran

Official websites: business as usual

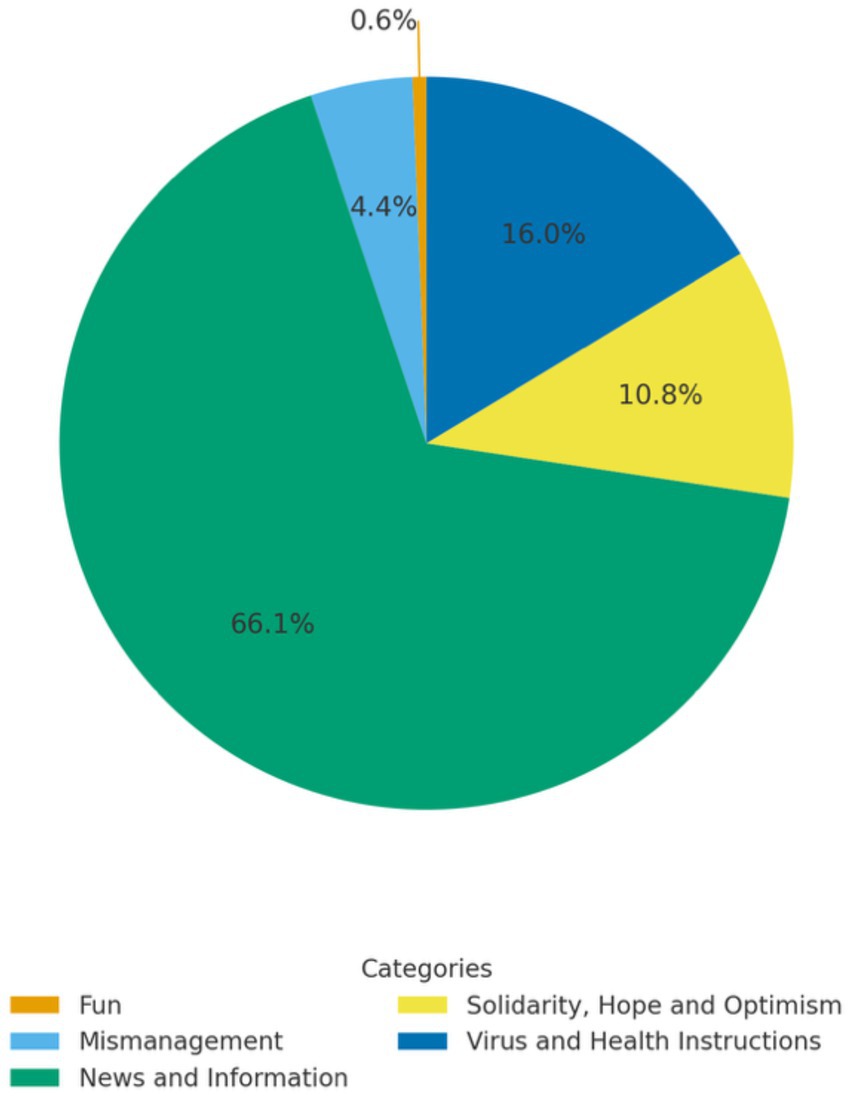

The first figure below presents the percentage of dominant issues on official websites.

Figure 1 indicates that NI overwhelmingly dominated the content of official websites (66.1%), followed by VHI (16.0%). Together, these two news-leaning agendas account for 82.1% of all content on official sites. This pattern is consistent with the composition of our “official websites” stratum, which is comprised mainly of professional news outlets, many of them the web editions of national newspapers and news agencies. The top-posting domains in our corpus were Young Journalists Club, Fars, ISNA, Jamaran, IRNA, Tasnim, Mehr, ILNA, and Borna; Iran’s most prominent mainstream news organizations. Unsurprisingly, their coverage concentrated on national-level news, reports and updates

By contrast, SHO received only modest attention (10.8%), and Mismanagement (4.4%) and Fun (0.6%) were negligible. The near absence of “Fun” content is expected for hard-news outlets. The comparatively low share of “Mismanagement” content is also consistent with the institutional environment in which these media operate, marked by licensing constraints, censorship, and continuous oversight, as well as ownership structures that are often state-linked. Under such conditions, critical coverage of government performance is less likely to be prioritized or sustained.

The curious case of Telegram

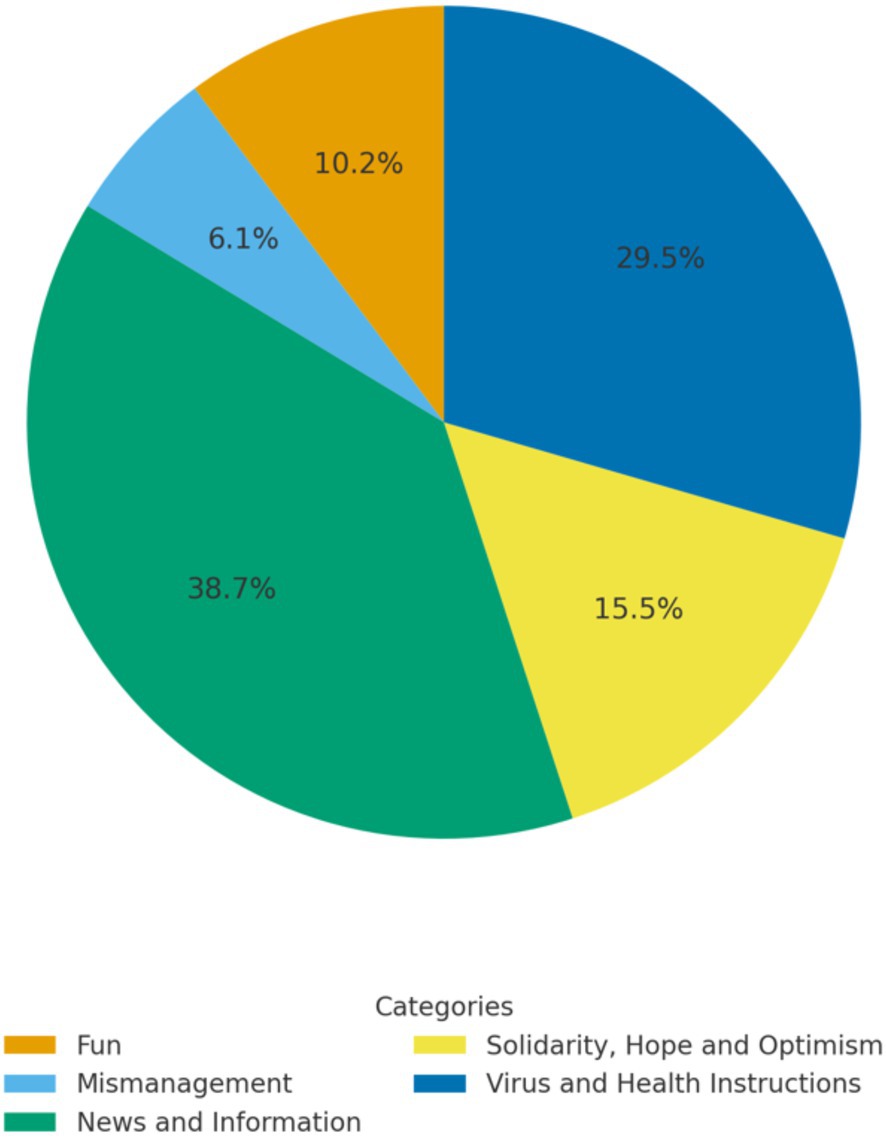

The following Figure 2 shows a high degree of similarity between the online media and Telegram agenda rankings.

Like online media, NI and VHI were also the most dominant issues on Telegram. Of course, the share of NI was lower than on official websites, but in response, the share of VHI was higher. As a result, these news issues together comprise 68.2% of all Telegram content. Despite the quantitative similarity, most Telegram news was dedicated to international and, more significantly, local news. For instance, @shirvanehdeh, a channel operated by the people of Shirvaneh Deh, a village in Abbas-e Gharbi Rural District, Tekmeh Dash District, Bostanabad County, East Azerbaijan Province, Iran, shared the latest COVID-19 news daily. The village accommodates only 346 families. Running a channel on Telegram is easy and does not entail significant cost. Therefore, even people in such small villages and cities carried it out efficiently. However, running a news website is more complicated and expensive. This is probably why local channels were partially common on Telegram.

Mirroring official websites, Telegram also exhibits a low prevalence of Mismanagement (6.1%), which is initially counter-intuitive. Several factors may explain this pattern. First, Telegram’s user base, large both pre- and post-blocking, has been broader and more heterogeneous than Twitter’s, encompassing older and less politically engaged users (including rural populations) (Gohdes, 2024). This broader audience likely favors popular, utilitarian, and informational content over overtly critical discourse. Second, alongside openly state-linked channels, some high-reach channels appear to receive indirect support or operate under incentives that align with official narratives (e.g., @Khabar_Fouri, ~935 k followers). Others are domestically operated, commercially motivated channels (e.g., @GizmizTel, ~1.02 M followers) whose operators seek growth, advertising revenue, and regulatory safety. After the ban, the legal and reputational risks of posting on a filtered platform plausibly increased self-censorship among such channels: to retain access to audiences and avoid entanglement with authorities, they tend to prioritize non-challenging content, e.g., news updates, practical information, and entertainment, over critical coverage of government performance.

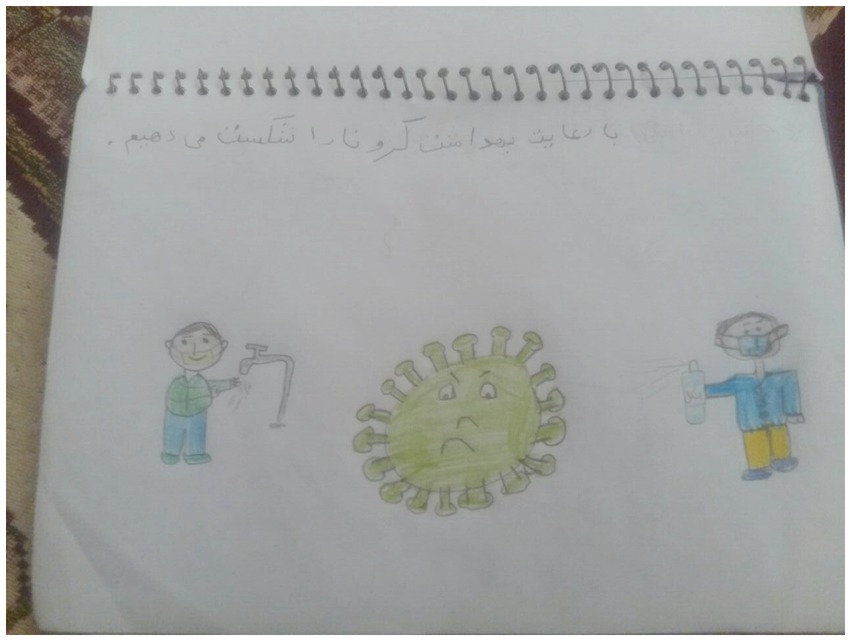

On Telegram, SHO was frequently articulated in a regime-aligned register: posts highlighted state capacity and resilience in managing the crisis and foregrounded the contributions of the Basij and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC/Sepah) to pandemic control. Given that these organizations are routinely criticized by opposition groups and human-rights advocates for their role in suppressing dissent, portraying them as protective and community-oriented actors aligns closely with the government’s preferred narrative. This framing often co-occurred with prominent gratitude themes; thanking physicians and medical staff as life-savers during the pandemic, which provided a civic, non-contentious wrapper for otherwise state-affirming messages. In pursuit of broad reach and emotional resonance, many channels also adopted a sentimental tone, further softening the political edge while amplifying compliance and unity cues. The Figure 3 (a drawing by an elementary student urging adherence to health guidance shared on Telegram) provides an example.

Twitter: a political platform amid the pandemic

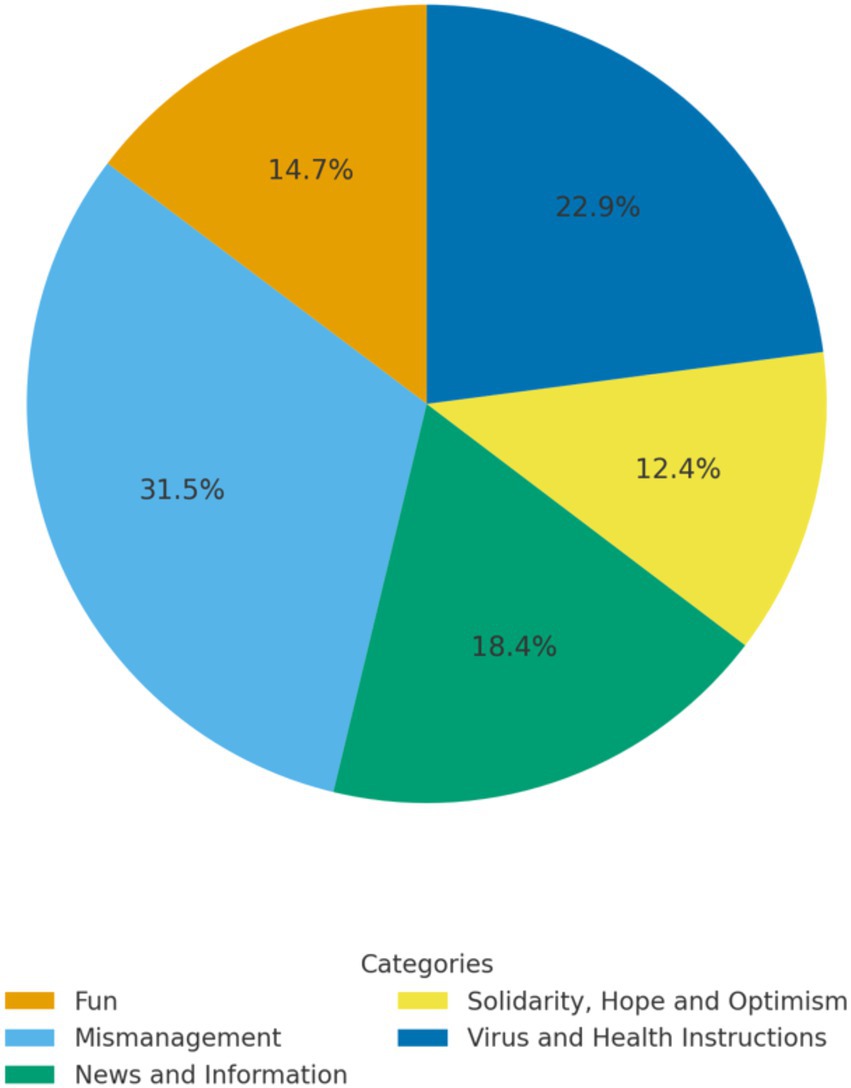

The following chart reveals a sharp difference between Twitter and the outlets above (Figure 4).

Not only was mismanagement the most dominant issue on Twitter, but its discursive articulation was also significantly different from that in online media and Telegram. This theme on Twitter was mainly occupied by anti-regime sentiment and messages criticizing the regime for poor performance and putting the citizens’ lives in danger. This oppositional tenor is consistent with Twitter’s long-standing, dissident-leaning ecology in Iran, which, despite periodic state efforts to reshape it, has remained comparatively hostile to the regime’s narratives (e.g., Azadi and Mesgaran, 2021; Kermani and Tafreshi, 2022; Khazraee, 2019). Beyond blaming the regime, dissident users often extended critique outward, targeting the regime’s international alignments (notably with China, frequently framed as a vector of viral spread). By contrast, the minor Mismanagement shares on official websites (4.4%) and Telegram (6.1%) concentrated on externalized blame (the United States/Western governments), mirroring their more regime-compatible discursive posture. Moreover, while Twitter is widely known as a breaking-news channel, in our corpus, NI on Twitter (18.4%) trailed Mismanagement and VHI (22.9%). In contrast, Telegram’s NI was substantially higher (38.7%), indicating that during COVID-19, Telegram functioned more as a news-dissemination hub than Twitter in Persian-language communication.

Pro-regime accounts on Twitter sought to articulate SHO in defense of state performance, echoing Telegram’s regime-aligned SHO register by emphasizing Basij and IRGC (Sepah) as protective, service-oriented actors. Another discursive struggle emerged around science vs. “traditional medicine.” Dissident users stressed science-based solutions (vaccination, biomedical guidance), while pro-regime voices promoted non−/pseudo-scientific remedies and traditional medicine, consistent with broader anti-Western discursive strategies. Unlike on Telegram, however, these regime-aligned SHO and traditional-medicine frames failed to achieve prominence on Twitter, where oppositional Mismanagement narratives sustained agenda dominance.

Instagram; somewhere in the middle

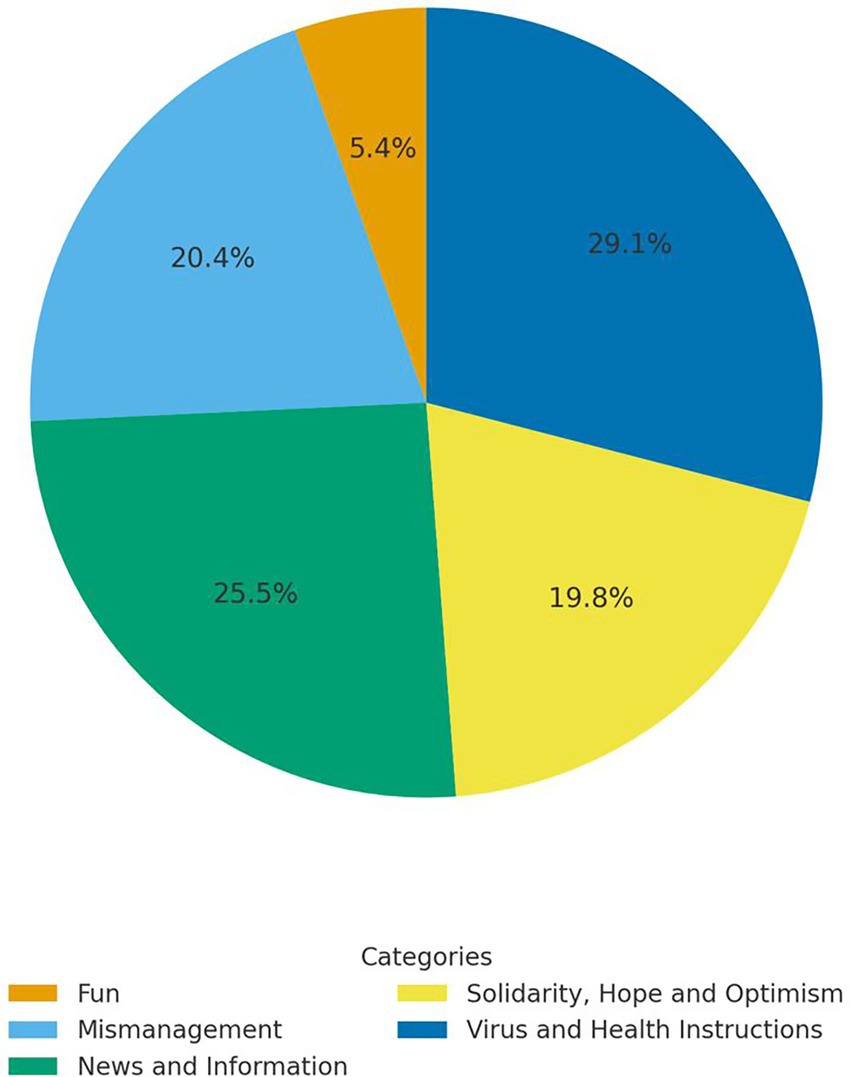

The final chart below presents the share of issues on Instagram.

Two patterns stand out in Figure 5. First, VHI (29.1%) modestly exceeds NI (25.5%); second, SHO (19.8%) is higher on Instagram than on any other medium in our study. Both patterns are consistent with Instagram’s visual-first architecture, which privileges fast, affect-laden communication, as public-health guidance and morale-boosting content travel efficiently through images, infographics, and short videos. A notable departure from platform affordances is the low share of Fun (5.4%), suggesting that during the crisis, information-seeking and compliance cues displaced entertainment.

SHO on Instagram closely followed the gratitude frame, prominently celebrating medical staff’s sacrifices while remaining comparatively non-contentious. By contrast, Mismanagement (20.4%) positions Instagram between other media: lower than Twitter (31.5%), yet substantially higher than official websites (4.4%) and Telegram (6.1%). Its discursive articulation also blended critical and regime-compatible strands. On one hand, posts faulted authorities for inadequate preparedness and crisis handling; on the other, they externalized blame (e.g., highlighting severe conditions in Western countries as cautionary examples) and individualized responsibility (urging citizens to stay home and follow rules). For instance, a user wrote: My fellow countrymen, please please please stay at home these days. Do not go on vacations and stop other entertainments. You are spreading the virus with your irresponsibility and carelessness. This latter emphasis, which shifts accountability toward the public, aligns with broader regime-favoring narratives and helps explain why Instagram functions as a hybrid arena: highly effective for disseminating VHI and SHO, while hosting a tempered Mismanagement discourse: more critical than official websites and Telegram, but less oppositional than Twitter.

The following section presents the transfer entropy output to test the interplay among media outlets.

Intermedia agenda-setting in Iran during the pandemic

Having established similarities and differences in issue salience across social platforms and official news sites, we now examine information transfer between these media.

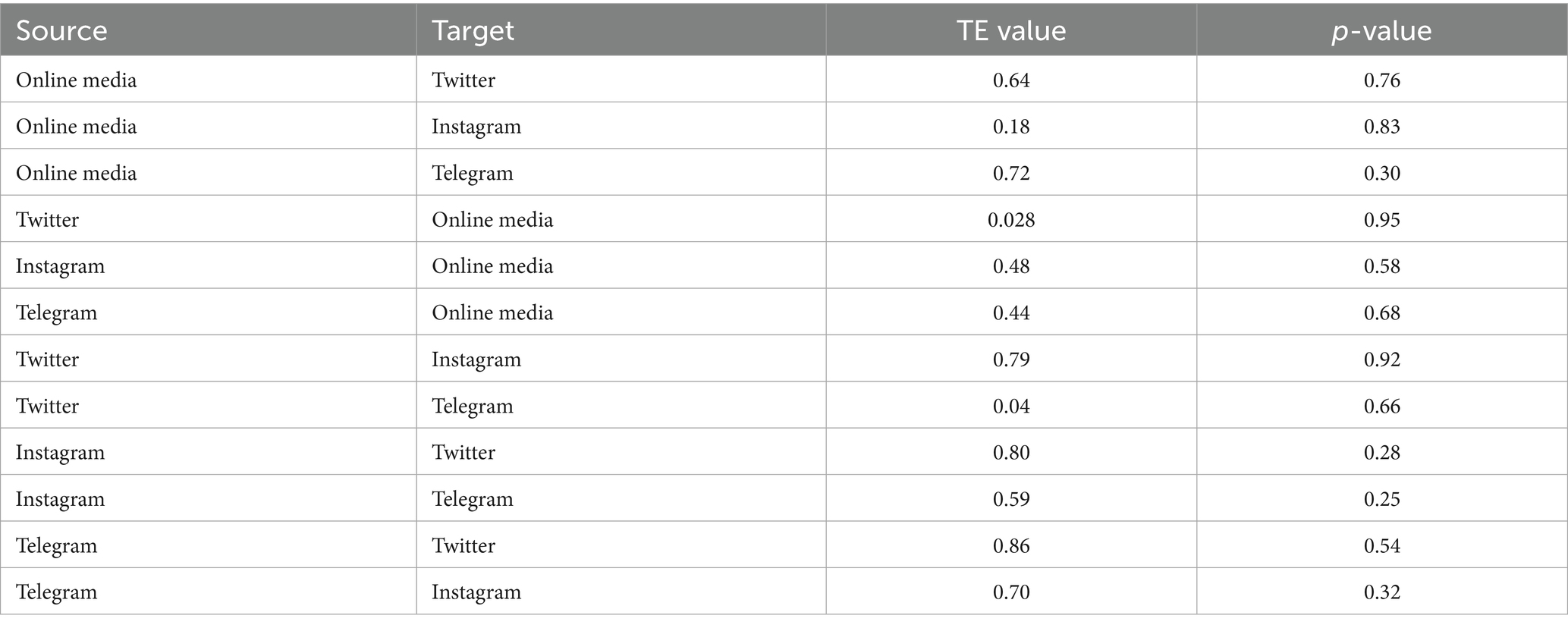

Table 1 shows that across all pairs, no p-value is below 0.05, so we do not reject the null of no directed predictive influence for any source to target pair in this aggregate analysis. This is unsurprising for cross-domain flows between online news and social platforms, but it is noteworthy for social-to-social links where some coupling was expected. Statistically, these are null results, not proofs of absence. We should notice that TE estimates can be attenuated by several factors, such as short or noisy series, common shocks (e.g., nation-wide announcements) that affect platforms simultaneously, and platform access throttling that distorts timing. We will discuss these null findings in the final section.

Discussion

This study examines Iran as an understudied authoritarian setting during the COVID-19 pandemic to illuminate intermedia dynamics in non-democratic contexts. We analyze IAS between social and traditional media, as well as interplatform dynamics among social media. In doing so, the paper clarifies how Iranian social-media users constructed issue salience and assesses the extent to which these salient issues converged with or diverged from those articulated in official media.

Findings reveal that while citizens around the globe mainly focus on a set of core issues, e.g., pandemic statistics, prevention measures, and government responses (Han et al., 2021; Krishnatray and Shrivastava, 2021; Šķestere and Darģis, 2022), the quantitative ranking and discursive articulation of these issues can be context-specific. In this study, we identified five salient issues in the Iranian media: NI, VHI, SHO, mismanagement, and fun. While NI and VHI were canonical themes during the pandemic, which dominated both traditional and social media regardless of the context (Han et al., 2021; Krishnatray and Shrivastava, 2021), SHO and Mismanagement were more ideologically driven. Not only were contentious issues like Mismanagement absent in democratic contexts to some extent, but even when they appeared, they mainly focused on the government’s performance (Hayek, 2024; Solvoll and Høiby, 2022; Teschendorf, 2023). On the contrary, in a repressive context like Iran, Mismanagement was articulated in opposition to the totality of the regime to a great extent, particularly on Twitter. Iranian users employed COVID-19 as an opportunity to criticize the whole regime and connected its poor COVID-19 performance with its historical failure in serving the people. As in other authoritarian regimes like Russia, Mismanagement was of the lowest interest in official media in Iran (Stepanov and Komendantova, 2022). Nevertheless, in countries with greater media freedom, such as Turkey, despite recent tightening, Mismanagement emerged in the criticism of the government, particularly in opposition media and on Twitter (Moussa et al., 2023).

While Mismanagement remained mainly anti-regime, despite its low share of anti-Western articulation on Telegram and official media, SHO was framed mostly in defence of the regime across all platforms. This finding shows a high similarity with other authoritarian regimes, which attempted to use the crisis as an opportunity to bolster their capabilities and successes. Zhang (2023) show that the Chinese government and party Weibo shifted toward soft, affect-laden propaganda during COVID-19 and heroic depictions of medical staff paired with regime-credit claims. In contrast to pro-regime citizens and outlets, anti-regime users on Persian Twitter advanced a counternarrative that downplayed the role of regime military forces and foregrounded scientific progress. Although this narrative did not achieve hegemonic status, the contestation within SHO and between Mismanagement and SHO underscores that even ‘hope’ is politically constructed during crises, particularly in authoritarian regimes.

Nonetheless, whilst the existing literature on authoritarian regimes is mainly limited to a single platform or to comparisons between two media outlets (Zhou and Zheng, 2022; Luo, 2014; Qaisar and Riaz, 2021), our research compares three popular platforms with each other and with official media. In this way, we not only studied the interplay between official and social media but also among social platforms themselves. This comparative analysis indicates that Twitter was the most political social platform during the pandemic, as it was primarily used to share anti-regime content. Telegram was the least political social medium, and Instagram was a mixture of both. Although regime-aligned media predictably defend authority and depoliticize the sphere, our findings also clarify the extent to which social platforms differ in their agenda-setting under pandemic conditions.

Most notably, TE indicates no significant influence among Iranian media outlets. The lack of interplay between state-aligned websites and social platforms aligns with patterns observed in other authoritarian contexts and is consistent with agenda-cutting and suppression (Haarkötter, 2022; Buchmeier, 2020). Although modest cross-media influences have been observed in China and Turkey at certain times (including COVID-19; Luo, 2014; Qaisar and Riaz, 2021), Iran’s lack of any measurable linkage between official and social media is noteworthy. Official media in Iran, as mentioned earlier, are under severe censorship and surveillance. The regime either keeps them under tight control by owning them directly or by passing punitive laws and shutting them down frequently. This highly repressive environment led to an almost complete separation between official media and the public in Iran (Mahoozi, 2025; Minooie, 2019), which could explain this result. Another factor could be pertinent to the operationalization of ‘official media’ in this research. They were mainly news websites. Therefore, they cannot share as quickly as social media a wide range of short and long messages from news to fun. There are studies focusing on traditional media that reach different results (Gilardi et al., 2021; Luo, 2014; Vargo and Guo, 2017). Such studies focus only on news messages (coded into categories such as politics, economics, etc.) or on a few print mainstream media outlets. We took an exploratory approach to identify all issues in official and news media. This classification includes news-leaning agendas (NI and VHI) as well as other categories (like fun and mismanagement), which could have probably affected the result.

In addition, we detect no statistically significant inter-platform coupling across social media. Given their status as alternative arenas less constrained by regime norms, some cross-influence was anticipated. Although the blocking of Twitter and Telegram during the observation window plausibly attenuates interplatform transfer, our estimates continue to show null relations and pronounced divergences in agenda salience. While affordance differences offer a plausible mechanism, the observed cross-platform gaps in agenda salience substantially exceed what an affordance-only account would explain. Illustratively, despite Twitter’s reputation as a news-sharing venue, NI peaks on Telegram in our corpus. Note that our coding protocol prioritized the non-NI theme whenever NI co-occurred, consequently, NI counts are conservative. Even under this conservative rule, Telegram exhibits higher rates of pure news posts than Twitter. This pattern may reflect platform use: Twitter users often pair news with personal sentiments (Papacharissi and De Fatima Oliveira, 2012), whereas Telegram channels tend to circulate straightforward news bulletins.

Two additional factors, including the platform’s user base and its historical trajectory in society, may also account for cross-platform differences. The anti-regime tilt of political agenda-setting on Persian Twitter is plausibly rooted in the platform’s early adoption by dissenting, urban, and educated users (notably since the 2009 Green Movement) and their continued political use during crises (Azadi and Mesgaran, 2021; Kermani and Adham, 2021). They continued employing the platform for political purposes even during a health crisis, resulting in dominating Mismanagement and articulating other issues, such as SHO, in opposition to the regime. Telegram’s largely apolitical or regime-leaning profile in our data is plausibly linked to its large, socially broad user base and its local adoption history (Gohdes, 2024; Kermani, 2018). Before and despite its blocking in 2018, Telegram had on the order of 40–45 million Iranian users, and usage largely persisted through circumvention tools, giving it a mass-audience character that incentivizes channel admins to post easy-to-grasp., non-polarizing ‘bulletin’ content and to pursue commercial traffic via popular channels (Al-Rawi, 2022; Bayat et al., 2023; Dagres, 2022). These structural factors help explain why Telegram’s agenda often tracks state-media norms more closely than Twitter’s and also suggest that blocking per se is a weaker predictor of agenda patterns than audience composition and path-dependent platform embeddedness in Iran’s media ecology; they likely matter even more than affordances alone. These dynamics could also help explain platform-based user segmentation and the resulting interplatform independence of agendas.

While this study advances understanding of IAS in authoritarian settings, it has several limitations. First, the analysis is confined to a single case (Iran) and to the first wave of the pandemic; comparative, longitudinal research that spans subsequent waves and other health or political crises, includes additional platforms, and covers multiple countries would substantially extend this line of inquiry. Such designs could explicitly test how user-base composition and platforms’ local historical trajectories, alongside affordances, shape agenda setting across time and context. Second, our analyses focus on content rather than producers. Incorporating source typologies, e.g., user roles on social media (ordinary users, influencers, activists, bots) and domestic vs. exile outlets in legacy media, would help explain who drives IAS under repression and how agendas travel (or fail to travel) across media layers. Nonetheless, this study provides some insights into how IAS should be theorized and measured beyond democratic benchmarks.

Conclusion

This article mapped agendas across Twitter, Telegram, Instagram, and official news websites in Iran during the COVID-19 pandemic’s first wave and found a decoupled media system: no directional influence between the state and social media, and no interplatform coupling among social networks. Canonical health/news issues appeared everywhere, but contentious frames diverged sharply; Mismanagement concentrated in oppositional spaces, while SHO was mobilized to affirm regime competence, with counter-SHO articulations that foregrounded science rather than state credit.

Taken together, these results show that, under authoritarian rule, IAS during a health emergency neither mirrors the legacy leads/digital follows pattern typical in democracies nor coalesces into a unified social media chorus. Instead, agenda cutting insulates official outlets, and platform-specific publics, shaped by user-base composition and local platform histories, produce independent, politicized agendas. The study thus refines IAS for non-democratic contexts and offers a comparative template for future crisis communication research: theorize power, selection, and path dependence alongside affordances; measure directional influence directly; and design communication strategies that address each platform’s actual audience ecology rather than assuming cross-media diffusion.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because this study investigates social media posts written by anonymous people. Therefore, it does not jeopardize any human participants. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements because this study investigates social media posts written by anonymous people.

Author contributions

HK: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Writing – original draft. AB: Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft. RB: Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Open access funding provided by University of Vienna. The first author also thanks the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Vienna for their financial support for proofreading.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. We used ChatGPT (GPT-5) for literature searching and grammar/style polishing only. Study design, theory development, data analysis, and interpretation were conducted exclusively by the authors.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2025.1598405/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

^We collected data from websites that have been registered by the Iranian government. We used a list of 770 websites in the Iranian Ministry of Culture and Guidance. In this sense, we refer to them as official news websites.

^Since SML models tend to perform well with clear-cut binary categories (De Grove et al., 2020), we tried to aggregate diverse codes into some general and inclusive themes. This way, we hope that the model gives better results. However, putting different codes in similar classes may lead to losing some meaning in the text. First, it is an inevitable choice since there is a trade-off between generalizing classes and covering the grounded meaning. Second, we tried to lessen this weakness by incorporating discursive and qualitative interpretations. This indicates that while we put the codes in general categories regarding the methodological limitations, we did not confine our analyses to those classes. We used discursive analyses to better understand how these classes were elaborated in different media.

References

Al-Rawi, A. (2022). News loopholing: telegram news as portable alternative media. J. Comput. Soc. Sci. 5, 949–968. doi: 10.1007/s42001-021-00155-3

Arazo, E., Ortego, D., Albert, P., O’Connor, N. E., and McGuinness, K. (2020). Pseudo-labeling and confirmation bias in deep semi-supervised learning. arXiv. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1908.02983

Asur, S., Huberman, B. A., Szabo, G., and Wang, C. (2011). Trends in social media: persistence and decay. SSRN Electron. J. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1755748

Azadi, P., and Mesgaran, M. B. (2021). The clash of ideologies on Persian twitter (issue 10). University of Stanford.

Bayat, A., Fathian, M., Moghaddam, N. B., and Saifoddin, A. (2023). The adoption of social messaging apps in Iran: discourses and challenges. Inf. Dev. 39, 72–85. doi: 10.1177/02666669211022032

Belinskaya, Y. (2021). The ghosts Navalny met: Russian YouTube-sphere in check. J. Med. 2, 674–696. doi: 10.3390/journalmedia2040040

Beñaran-Muñoz, I., Hernández-González, J., and Pérez, A. (2018). Candidate Labeling for Crowd Learning (No. arXiv:1804.10023). doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1804.10023

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Buchmeier, Y. (2020). Towards a conceptualization and operationalization of agenda-cutting: a research agenda for a neglected media phenomenon. Journal. Stud. 21, 2007–2024. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2020.1809493

Burscher, B., Odijk, D., Vliegenthart, R., de Rijke, M., and Vreese, C. H. (2014). Teaching the computer to code frames in news: comparing two supervised machine learning approaches to frame analysis. Commun. Methods Meas. 8, 190–206. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2014.937527

Carafano, J. J. (2009). All a twitter: how social networking shaped Iran’s election protests. In The Heritage Foundation (Vol. 4999, Issue 2300).

Dada, S., Ashworth, H. C., Bewa, M. J., and Dhatt, R. (2021). Words matter: political and gender analysis of speeches made by heads of government during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Glob. Health 6:e003910. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003910

Dagres, H. (2022). Iranians on #SocialMedia. Atlantic Counci Available online at: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Iranians-on-SocialMedia.pdf (Accessed June 20, 2024).

De Grove, F., Boghe, K., and De Marez, L. (2020). (what) can journalism studies learn from supervised machine learning? Journal. Stud. 21, 912–927. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2020.1743737

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K., and Toutanova, K. (2019). BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding (No. arXiv:1810.04805). doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1810.04805

Djerf-Pierre, M., and Shehata, A. (2017). Still an agenda setter: traditional news media and public opinion during the transition from low to high choice media environments: still an agenda setter. J. Commun. 67, 733–757. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12327

Farahani, M., Gharachorloo, M., Farahani, M., and Manthouri, M. (2021). ParsBERT: transformer-based model for Persian language understanding. Neural. Process. Lett. 53, 3831–3847. doi: 10.1007/s11063-021-10528-4

Faris, D. M., and Rahimi, B. (2016). Social Media in Iran: Politics and society after 2009. Albany, NY: SUNY.

Gilardi, F., Gessler, T., Kubli, M., and Müller, S. (2021). Social media and political agenda setting. Polit. Commun. 39, 39–60. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2021.1910390

Gohdes, A. R. (2024). “Online controls and the protest- repression nexus in Iran” in Repression in the digital age. 1st ed. Ed. A. R. Gohdes (New York: Oxford University Press), 113–129.

Grimmer, J., and Stewart, B. M. (2013). Text as data: the promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Polit. Anal. 21, 267–297. doi: 10.1093/pan/mps028

Guo, L. (2019). Media agenda diversity and intermedia agenda setting in a controlled media environment: a computational analysis of China’s online news. Journal. Stud. 20, 2460–2477. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2019.1601029

Han, C., Yang, M., and Piterou, A. (2021). Do news media and citizens have the same agenda on COVID-19? An empirical comparison of twitter posts. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 169:120849. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120849

Hayek, L. (2024). Media framing of government crisis communication during Covid-19. Media Commun. 12:7774. doi: 10.17645/mac.7774

Highfield, T., and Leaver, T. (2016). Instagrammatics and digital methods: studying visual social media, from selfies and GIFs to memes and emoji. Commun. Res. Pract. 2, 47–62. doi: 10.1080/22041451.2016.1155332

Jurafsky, D., and Martin, J. H. (2020). Speech and language processing. Available online at: https://web.stanford.edu/~jurafsky/slp3/ (Accessed April 29, 2024).

Kemp, S. 2020 Digital 2020: Iran. In We are Social & Hootsuite. Available online at: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-global-digital-overview (Accessed June 10, 2024).

Kermani, H. (2018). Telegramming news: how have telegram channels transformed the journalism in Iran? Türkiye İletişim Araştırmaları Dergisi 31, 168–187. doi: 10.17829/turcom.423307

Kermani, H. (2020). Decoding telegram: Iranian users and ‘Produsaging’ discourses in Iran’s 2017 presidential election. Asiascape Digit. Asia 7, 88–121. doi: 10.1163/22142312-12340119

Kermani, H., and Adham, M. (2021). Mapping Persian twitter: networks and mechanism of political communication in Iranian 2017 presidential election. Big Data Soc. 8:5568. doi: 10.1177/20539517211025568

Kermani, H., and Tafreshi, A. (2022). Walking with Bourdieu into Twitter communities: An analysis of networked publics struggling on power in Iranian Twittersphere. Inf. Commun. Soc. 1–22. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2021.2021267

Khazraee, E. (2019). Mapping the political landscape of Persian Twitter: The case of 2013 presidential election. Big Data Soc. 6. doi: 10.1177/2053951719835232

King, G., Pan, J., and Roberts, M. E. (2013). How censorship in China allows government criticism but silences collective expression. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 107, 326–343. doi: 10.1017/S0003055413000014

Kohavi, R. (1995). A study of cross-validation and bootstrap for accuracy estimation and model selection. Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence - Volume 2, 1137–1143.

Krishnatray, P., and Shrivastava, S. (2021). Coronavirus pandemic: how national leaders framed their speeches to fellow citizens. Asia Pac. Media Educ. 31, 195–211. doi: 10.1177/1326365X211048589

Lombard, M., Snyder-Duch, J., and Bracken, C. C. (2002). Content Analysis in Mass Communication: Assessment and Reporting of Intercoder Reliability. Hum. Commun. Res. 28, 587–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00826.x

Lou, C., Tandoc, J. E. C., Hong, L. X., Pong, X. Y., Lye, W. X., and Sng, N. G. (2021). When motivations meet affordances: news consumption on telegram. Journal. Stud. 22, 934–952. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2021.1906299

Luo, Y. (2014). The internet and agenda setting in China: the influence of online public opinion on media coverage and government policy. Int. J. Commun. 8.

McCombs, M. E., Shaw, D. L., and Weaver, D. H. (2014). New directions in agenda-setting theory and research. Mass Commun. Soc. 17, 781–802. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2014.964871

Minooie, M. (2019). Agendamelding: how audiences meld agendas in Iran. Agenda Setting J. 3, 139–164. doi: 10.1075/asj.18010.min

Montiel, C. J., Uyheng, J., and Dela Paz, E. (2021). The language of pandemic leaderships: mapping political rhetoric during the COVID-19 outbreak. Polit. Psychol. 42, 747–766. doi: 10.1111/pops.12753

Moussa, M. B., Douai, A., and Parmaksiz, M. Y. (2023). “Flattening the curve”: communication, risk and COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Newsp. Res. J. 44, 131–153. doi: 10.1177/07395329231155149

Papacharissi, Z., and De Fatima Oliveira, M. (2012). Affective news and networked publics: the rhythms of news storytelling on #Egypt. J. Commun. 62, 266–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01630.x

Qaisar, A., and Riaz, S. (2021). Inter-Media Agenda setting between Twitter and News-Websites: A case study of the Turkish President’s Visit to Pakistan. Connectist: Istanbul UniversityJ. Commun. Sci. 61, 187–211.doi: 10.26650/CONNECTIST2021-811031

Russell Neuman, W., Guggenheim, L., Mo Jang, S., and Bae, S. Y. (2014). The dynamics of public attention: agenda-setting theory meets big data. J. Commun. 64, 193–214. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12088

Scharkow, M. (2013). Thematic content analysis using supervised machine learning: an empirical evaluation using German online news. Qual. Quant. 47, 761–773. doi: 10.1007/s11135-011-9545-7

Shestopalova, A. (2023). Constructing Nazis on political demand: agenda-setting and framing in Russian state-controlled TV coverage of the Euromaidan, annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas. Cent. Eur. J. Int. Secur. Stud. 17, 112–137. doi: 10.51870/FUQI2558

Šķestere, L., and Darģis, R. (2022). Agenda-setting dynamics during COVID-19: who leads and who follows? Sociol. Sci. 11:556. doi: 10.3390/socsci11120556

Solvoll, M., and Høiby, M. (2022). Framing of the COVID-19 pandemic: a case study of Norwegian broadcasting news- and debate programs. Mediekultur J. Media Commun. Res. 38, 006–027. doi: 10.7146/mk.v38i73.131934

Stepanov, I., and Komendantova, N. (2022). Analyzing Russian media policy on promoting vaccination and other COVID-19 risk mitigation measures. Front. Public Health 10:839386. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.839386

Teschendorf, V. S. (2023). Understanding COVID-19 media framing: comparative insights from Germany, the US, and the UK during omicron. Journal. Pract., 1–22. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2024.2412832

Theiler, J., Eubank, S., Longtin, A., Galdrikian, B., and Doyne Farmer, J. (1992). Testing for nonlinearity in time series: The method of surrogate data. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 58, 77–94. doi: 10.1016/0167-2789(92)90102-S

Theocharis, Y., Boulianne, S., Koc-Michalska, K., and Bimber, B. (2022). Platform affordances and political participation: how social media reshape political engagement. West Eur. Polit., 1–24. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2022.2087410

Tsao, S.-F., Chen, H., Tisseverasinghe, T., Yang, Y., Li, L., and Butt, Z. A. (2021). What social media told us in the time of COVID-19: a scoping review. Lancet. Digit. Health 3, e175–e194. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30315-0

Vargo, C. J., and Guo, L. (2017). Networks, big data, and intermedia agenda setting: an analysis of traditional, partisan, and emerging online U.S. news. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 94, 1031–1055. doi: 10.1177/1077699016679976

Vicente, R., Wibral, M., Lindner, M., and Pipa, G. (2011). Transfer entropy—A model-free measure of effective connectivity for the neurosciences. J. Comput. Neurosci. 30, 45–67. doi: 10.1007/s10827-010-0262-3

Vliegenthart, R., and Walgrave, S. (2008). The contingency of intermedia Agenda setting: A longitudinal study in Belgium. J. Mass Commun. Q. 85, 860–877. doi: 10.1177/107769900808500409

Wang, H., and Shi, J. (2022). Intermedia agenda setting amid the pandemic: a computational analysis of China’s online news. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 1–10. doi: 10.1155/2022/2471681

Wicke, P., and Bolognesi, M. M. (2020). Framing COVID-19: How we conceptualize and discuss the pandemic on Twitter. PLOS ONE. 15:e0240010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240010

Wolters, N., Hoch, E., and Abir, M. (2022). Iran: challenges and successes in COVID-19 pandemic response. Available online at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2022/04/iran-challenges-and-successes-in-covid-19-pandemic.html (Accessed September 12, 2025).

Xu, Y., Yu, J., and Löffelholz, M. (2022). Portraying the pandemic: analysis of textual-visual frames in German news coverage of COVID-19 on twitter. Journal. Pract., 1–21. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2022.2058063

Yang, Z., and Vicari, S. (2021). The pandemic across platform societies: Weibo and twitter at the outbreak of the Covid-19 epidemic in China and the west. Howard J. Commun. 32, 493–506. doi: 10.1080/10646175.2021.1945510

Yu, J., Lu, Y., and Muñoz-Justicia, J. (2020). Analyzing Spanish news frames on twitter during COVID-19—a network study of El País and El Mundo. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:15. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155414

Zhang, Y. (2023). Systematic literature review report: agenda-setting on social media. J. Educ. Human. Soc. Sci. 21, 214–226. doi: 10.54097/ehss.v21i.13280

Zhou, S., and Zheng, X. (2022). Agenda dynamics on social media during COVID-19 pandemic: interactions between public, media, and government Agendas. Commun. Stud. 73, 211–228. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2022.2082504

Keywords: intermedia agenda-setting, social media, agenda-cutting, COVID-19, Iran

Citation: Kermani H, Bayat Makou A and Behzadian Nejad R (2025) Decoupled agendas under repression: social media and state media during COVID-19 in Iran. Front. Commun. 10:1598405. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1598405

Edited by:

Stamatis Poulakidakos, University of Western Macedonia, GreeceReviewed by:

Mohammad Jafar Loilatu, Universitas Muhammadiyah Malang, IndonesiaAngga Prawira Kautsar, Padjadjaran University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Kermani, Bayat Makou and Behzadian Nejad. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hossein Kermani, aG9zc2Vpbi5rZXJtYW5pQHVuaXZpZS5hYy5hdA==

Hossein Kermani

Hossein Kermani Alireza Bayat Makou

Alireza Bayat Makou Reza Behzadian Nejad3

Reza Behzadian Nejad3