- Translating and Interpreting, School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

This article uses the interpreter’s perspective to explore communication challenges arising from linguistic and cultural discordances faced by LGBTIQA+ migrants when accessing public services in Australia. Drawing on qualitative data collected through interviews with 24 interpreters working across 12 languages, this research reveals the multidimensional complexities of language mediation in encounters involving gender and sexual identity. The findings highlight three key challenges: (1) linguistic barriers, including the absence of standardised translated LGBTIQA+ terminology and difficulties with the use of pronouns; (2) cultural challenges, where interpreters need to strike a balance between linguistic accuracy and cultural sensitivity; and (3) the emotional burden borne by interpreters as a result of their exposure to sensitive, traumatic, or emotionally charged narratives. To address these issues, the study recommends developing multilingual LGBTIQA+ glossaries, improving interpreters’ access to briefings, and incorporating LGBTIQA+ topics into interpreter training and education. These measures aim to foster equitable, dignified communication for LGBTIQA+ migrants in Australia.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, the visibility of LGBTIQA+1 individuals within global migration trends has increased (Tabak, 2016), with scholars coining the term “sexual migration” to describe the phenomenon of international relocation that is driven, in whole or in part, by the sexuality or gender identity of the migrants (Carrillo, 2004; Usta and Ozbilgin, 2023). Mai and King (2009, p. 296) echo this observation by proposing a “sexual turn” in migration studies, arguing that migrants are “sexual beings expressing, wanting to express, or denied the means to express, their sexual identities.” This highlights the fact that migration is no longer solely driven by economic or political factors, but also by the pursuit of safety and freedom to express one’s sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and sex characteristics (or SOGIESC in short). Compared with other migrants, however, individuals who identify as non-heteronormative face an additional layer of complexity in their experiences in the host country (Namer and Razum, 2018). Research consistently indicates that LGBTIQA+ individuals often face discrimination and marginalisation, as well as restricted access to public services (e.g., Albuquerque et al., 2016; Bristol et al., 2018; Clark, 2014; Daley et al., 2017). These multilayered challenges, when coupled with the linguistic and cultural discordances that occur during the process of resettlement in the new country, may amplify their vulnerability.

As early as 1985, Australia became one of the first countries in the world to formally recognise same-sex relationships as a basis for migration (Hart, 2002), a shift that aligned the country’s immigration frameworks with its increasingly inclusive environment and social attitudes towards sexual and gender diversity (Offord, 2001). This shift emerged in parallel with Australia’s broader evolution into a multicultural and more tolerant society, and was an effort to address the growing linguistic and cultural discordances (Hlavac, 2021) resulting from the super diversity of its migrant intake. Although legal frameworks have progressed, and despite the ostensible inclusivity promulgated at policy levels, little attention has been paid to the lived realities of LGBTIQA+ individuals, regardless of whether or not their SOGIESC is a factor in their decisions to migrate, obtain refugee status, or seek asylum. Evidence shows that the experiences of LGBTIQA+ migrants in Australia mirror those of their counterparts in other countries (Dawson, 2016; Forcibly Displaced People Network, 2023; Hill et al., 2020; Migration Council Australia, 2021; Multicultural Youth Advocacy Network, 2023), and include mistreatment in asylum or refugee application processes, challenges in detention centres, and discrimination in employment, education, housing, and access to essential services.

It is essential to recognise that although LGBTIQA+ individuals may migrate in pursuit of safety and opportunities for self-expression, seeking asylum or refugee status is not necessarily the only pathway. Research into queer migration shows that, for sexual minorities, while issues related to asylum seeking often play an important role, the participation of LGBTIQA+ individuals in transnational mobility is driven by a variety of factors that do not always align with the criteria for refugee status. Traditional migration frameworks have often operated under a heteronormative premise, that is, they have assumed that migrants are heterosexual while treating LGBTIQA+ individuals as citizens settled within national borders, consequently overlooking the layered experiences of queer migrants (Luibhéid, 2008). Luibhéid (2008) highlights that a queer individual may be motivated to move across borders by a strong desire for safety, belonging, or self-actualisation. Echoing this, Manalansan and Martin (2006) suggests that sexuality, as well as sexual identities, practises, and desires, can function as vital factors prompting international mobility. Mai and King (2009) further support this by accentuating sexual and emotional motivations as key drivers of migration, noting that migrants often seek spaces where they can live more openly and authentically. These compelling motives, however, typically fall outside the parameters of refugee recognition. Empirical research further corroborates these insights. For example, a study of South Asian gay men in Australia by Smith (2012, p. 92) illustrates how they are driven by “cultural expectations for marriage, social stigma about homosexuality and a lack of private spaces for sexual exploration” in their home countries. These factors, while not always constituting the legal persecution required for refugee or asylum claims, play a significant part in this group’s decisions regarding migration. Collectively, this body of literature offers a more nuanced picture of queer migration—one in which individuals are motivated by a combination of factors related to safety, self-expression, and authentic living.

Ascertaining the exact size of Australia’s LGBTIQA+ population remains a challenge due to a lack of dedicated, large-scale data collection. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) had not collected LGBTIQA+ population data up to the most recent Census, held in 2021, while attempts to include relevant questions in the upcoming (2026) Census still encountered political resistance, with the government stating that it did not want to “open up a divisive debate in relation to this issue” (Linder, 2024b). The government, thus, failed to understand that population-level data can enhance understanding of the health and wellbeing needs of the LGBTIQA+ population, and can facilitate the development of policy and programmes for their communities (Carman et al., 2020). After a community outcry and political revolt, the government reverted its decision, announcing in late August 2024 that it would look to include data on sexual orientation in the 2026 Census (Linder, 2024a). In December 2024 the ABS released its first experimental estimates, that 4.5% of Australians aged 16 and over are LGBTIQA+, a statistic derived from combining data from roughly 45,000 responses to four health surveys (ABS, 2024a,b). However, the government’s own Department of Health has estimated “LGBTI people as representing 11% of the population” (Commonwealth of Australia, 2019, p. 5), without explaining how this number was arrived at. By contrast, Aotearoa New Zealand has moved forward in this regard—from its 2023 Census it is able to provide the first confirmed statistics regarding the 4.9% (i.e., almost 1 in 20) of the country’s adults who belong to its rainbow population (Stats NZ, 2024). Similarly, Scotland included voluntary questions about sexuality, trans health and identity in its 2022 Census for the first time (Linder, 2024a), leading to the understanding that 4.0% of people aged 16 and over in Scotland identified as LGBTIQA+ (NRS, 2024). The rest of the United Kingdom had taken the lead in its 2021 Census by asking the same question, thereby gaining the knowledge that the LGBTIQA+ population is 3.2% of the overall population in England and Wales and 2.1% in Northern Ireland (NRS, 2024).

While these recently emerging national data are encouraging, Carman et al. (2020) call for more policy attention and targeted research in Australia, to promote change for equity and inclusion in view of the existing disparities in health, particularly mental health, experienced by LGBTIQA+ community members compared to the rest of the population. It is important to note, though, that these emerging data do not inform the proportion of the LGBTIQA+ population who come from culturally and linguistic diverse (CALD) backgrounds, including refugees and people seeking asylum, in the respective national contexts. This lack of visibility has made addressing the intersectional vulnerability of these community members even more challenging, which, in turn, perpetuates systemic inadequacies in policy and allocation of resources, including appropriate languages services.

2 Research context

The lived experiences of LGBTIQA+ individuals in Australia have begun to attract interest, although still on a relatively limited scale, amongst researchers (Asquith et al., 2019; Grant et al., 2021; Hughes and King, 2018; Saxby, 2022), government bodies (Hill et al., 2020) and non-governmental organisations (Carman et al., 2020). A prominent focus is the health and wellbeing (Amos et al., 2023; Grant and Nash, 2019; Hallett et al., 2024), especially mental health (Bond et al., 2017; Istiko et al., 2024), of LGBTIQA+ individuals. For example, findings from longitudinal studies such as La Trobe University’s Private Lives 3 Survey highlight that gender diverse individuals are disproportionately affected by mental health burdens, including higher rates of depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (Hill et al., 2020). Parallel research identifies and critiques barriers to service access, revealing how heteronormative assumptions and/or lack of LGBTIQA+ awareness or cultural competence amongst service providers often prevent effective support (Cronin et al., 2021; Hughes, 2009; Lim et al., 2022). Other research trajectories include policy analysis (Pienaar et al., 2018), the experiences and support needs of LGBTIQA+ students in higher education (Waling and Roffee, 2017, 2018), and the interactions of LGBTIQA+ individuals with law enforcement (Dwyer et al., 2015; Dwyer et al., 2022).

In contrast, research into the experiences of LGBTIQA+ migrants in Australia remains sparse, with only isolated studies on refugees or asylum seekers (Aiyar, 2020; Noto et al., 2014). When these individuals lack English proficiency, they often need to rely on language mediation to access public services. Even less is known about these communicative settings in relation to the efficacy of the language services provided and received. Interpreting in these encounters is highly challenging, as it must not only bridge linguistic and cultural discordances as in other public service contexts, but also convey SOGIESC issues when they emerge with sensitivity and respect, in both English and the language other than English (LOTE). Interpreters are not the authors of the utterances they interpret, and therefore may encounter ethical dilemmas in their level of intervention in such situations. They may also lack training and professional development in this topic area, and therefore—whether knowingly or unknowingly—perpetuate their own values or prejudices in their language output, thereby potentially harming the LGBTIQA+ individual receiving the service. The current study set out to address this gap in knowledge by exploring mediated communication in settings involving LGBTIQA+ individuals in Australia, examining the topic from the interpreter’s perspective with the intention of providing insights and recommendations.

Australia has relatively advanced language service infrastructure compared to most other countries that operate similar migration and humanitarian intake programmes. Community interpreting is publicly funded in Australia, so it is provided at no cost to community members who are not proficient in English but need to access public services such as for healthcare, welfare support and legal matters. According to Australia’s National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters (NAATI), the national standards and certifying authority, there are 9,365 individual practitioners holding 13,942 NAATI certification credentials in 184 languages (NAATI, 2024). Although there are no direct statistics, it is reasonable to deduce that of Australia’s 25.4 million population (ABS, n.d.), those born overseas (just over 7 million, or 27.6%), or who speak a LOTE at home (5.8 million, or 22.8%) (ABS, 2022) would be the main users of interpreting and translating services. Practitioners must abide by a code of ethics and code of conduct issued by the professional association in the country, the Australian Institute of Interpreters and Translators (AUSIT) (see https://ausit.org/code-of-ethics/). Credentialled interpreters in Australia mostly operate as freelancers, registering with multiple language service providers, which are a mixture of private for-profit and government-owned businesses. In principle, public services must use NAATI-certified interpreters (Department of Social Service, n.d.). However, uncertified interpreters are still engaged, either due to shortages of credentialled interpreters in certain languages, or as a shortcut or means to save money in “low-risk situations” (Federation of Ethnic Communities Councils of Australia, 2016, p. 14), and there are still services which opt for using family members or non-trained bilingual persons whose LOTE proficiency is unverified, or even attempt to get by with minimal English spoken by the service receiver, due to a lack of either funding or appreciation of the importance of professional interpreting services.

2.1 Theoretical foundation and analytical lens

This research adopts intersectionality theory as its primary theoretical framework to investigate the communication challenges experienced by LGBTIQA+ migrants through the lens of interpreters. Originally a concept that emerged from Black feminist scholarship, the term “intersectionality” was coined by American legal scholar Crenshaw (1989) in her seminal work Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex which critically pointed out the limitations of anti-discrimination laws in addressing the unique experiences of Black women who faced both racial and gender discrimination. Crenshaw further argued that these women were often disregarded in both feminist and anti-racist legal frameworks, as there was a tendency to see gender and race as separate—rather than interconnected—categories for oppression. Intersectionality theory, therefore, posits that various social and political identities—including race, gender, sexuality, class and nationality—overlap and interact, resulting in specific vulnerabilities for individuals with multiple identities (Crenshaw, 1991). This framework moves beyond single-axis analytical tools, taking into consideration how multiple identities contribute to the compounded marginalisation and discrimination experienced by certain social groups.

For LGBTIQA+ migrants, intersectionality is particularly relevant. These individuals often find themselves in multiple marginalised positions simultaneously: as sexual and gender minorities, as migrants, and often also as members of racial, ethnic or religious minorities. Traditional single-axis approaches would not be sufficient for understanding the multidimensional challenges that queer migrants may encounter. Intersectionality theory provides an analytical tool to effectively examine how these multiple identities collectively contribute to forms of marginalisation that may be different from those experienced by heterosexual migrants or by local LGBTIQA+ community members.

To shed further light on the dynamics of interpreter-mediated communication for LGBTIQA+ migrants, we also draw upon Georg Simmel’s (Rogers, 1999; Simmel, 1908) concept of the stranger (i.e., a third person joins a dyad) and the formation of a social group (i.e., a triad), leading to possibilities for dissolution vs. consolidation, or conflict vs. appeasement. For Simmel (1950), the stranger is not simply a random unknown or foreign figure, but rather an individual who is part of a social group but at the same time outside of it. This placement enables a more objective viewpoint in which strangers occupy a unique position of “distance and nearness, indifference and involvement” (Simmel, 1950, p. 404). In possessing adequate knowledge of the dynamics of the group, the stranger is able to assume a detached perspective and observe what insiders might miss.

An interpreter, by their very role, is positioned as “the stranger” in the mediated interaction between an LGBTIQA+ migrant and a service provider. They are “near” in the sense that they are responsible for facilitating communication and bridging cultural understanding in the interaction. At the same time, they are “far” because they are required to maintain impartiality and keep a personal distance from the content and outcome of the communication. In the communication triad, i.e., a three-person social group (queer migrant, service provider, interpreter), the interpreter finds themself acting as the third party who “takes on the task of the intermediary ‘expert’ with the potential to consolidate or weaken, or at any rate to influence and shape, the social form of the triad” (Bahadır, 2010, p. 127). The current researchers, therefore, acknowledge interpreters’ unenviable situation they oscillate between taking on the role of the powerful (i.e., the service provider or institutional representative) and the oppressed other (Bernstein, 1997; Corrigan et al., 2009; Drescher, 2004) (i.e., the LGBTIQA+ individual).

3 Materials and methods

This study employed an exploratory, qualitative research design to investigate mediated communication for LGBTIQA+ migrants in Australian public service contexts from the interpreter’s perspective. Our decision to focus on interpreters as research participants was made based on both theoretical and methodological considerations. As people who straddle two epistemological spheres, i.e., those of migrant experiences and institutional service provision, interpreters’ unique professional role as strangers who are both “far” and “near” (Simmel, 1950) affords them the opportunity to be witnesses, observing patterns of possible oppression and communication barriers in private, often sensitive communications which are typically inaccessible to researchers. The current researchers’ existing professional networks conveniently provided access to potential interpreter participants who could answer the research questions. Methodologically, this approach circumvented the challenges of identifying and recruiting LGBTIQA+ migrants, who may understandably be reluctant to “out themselves.” We also took into account the potential risk of re-traumatisation when speaking directly to queer participants, particularly if they continue to face discrimination in Australia, where they have settled.

The study was conducted within a larger project in which an LGBTIQA+ terminology repository was constructed to house translations into multiple community languages, using a critical social perspective (Bloomberg and Volpe, 2012; Dunk-West and Saxton, 2024) to create the language resources (see www.rainbowterminology.org). The current study intended to gain understanding about intersectional adversities experienced by queer migrants through insights and perspectives contributed by interpreters as communication mediators in public service encounters where they had to navigate linguistic and cultural discordances. The aim was to identify issues encountered by interpreters in their practice for the purpose of enhancing the language services ultimately received by their LGBTIQA+ clients. Ethics approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee at RMIT University where the researchers are based.

One-on-one interviews was chosen as the data collection method, and a purposive sampling strategy was employed to recruit professional interpreters who had both NAATI credentials and first-hand experience interpreting for LGBTIQA+ clients in a community setting (e.g., healthcare, legal, social services). Recruitment letters were distributed electronically through various interpreter deployment agencies and two professional organisations, AUSIT and NAATI, calling for expressions of interest (EOIs) to participate in online interviews.

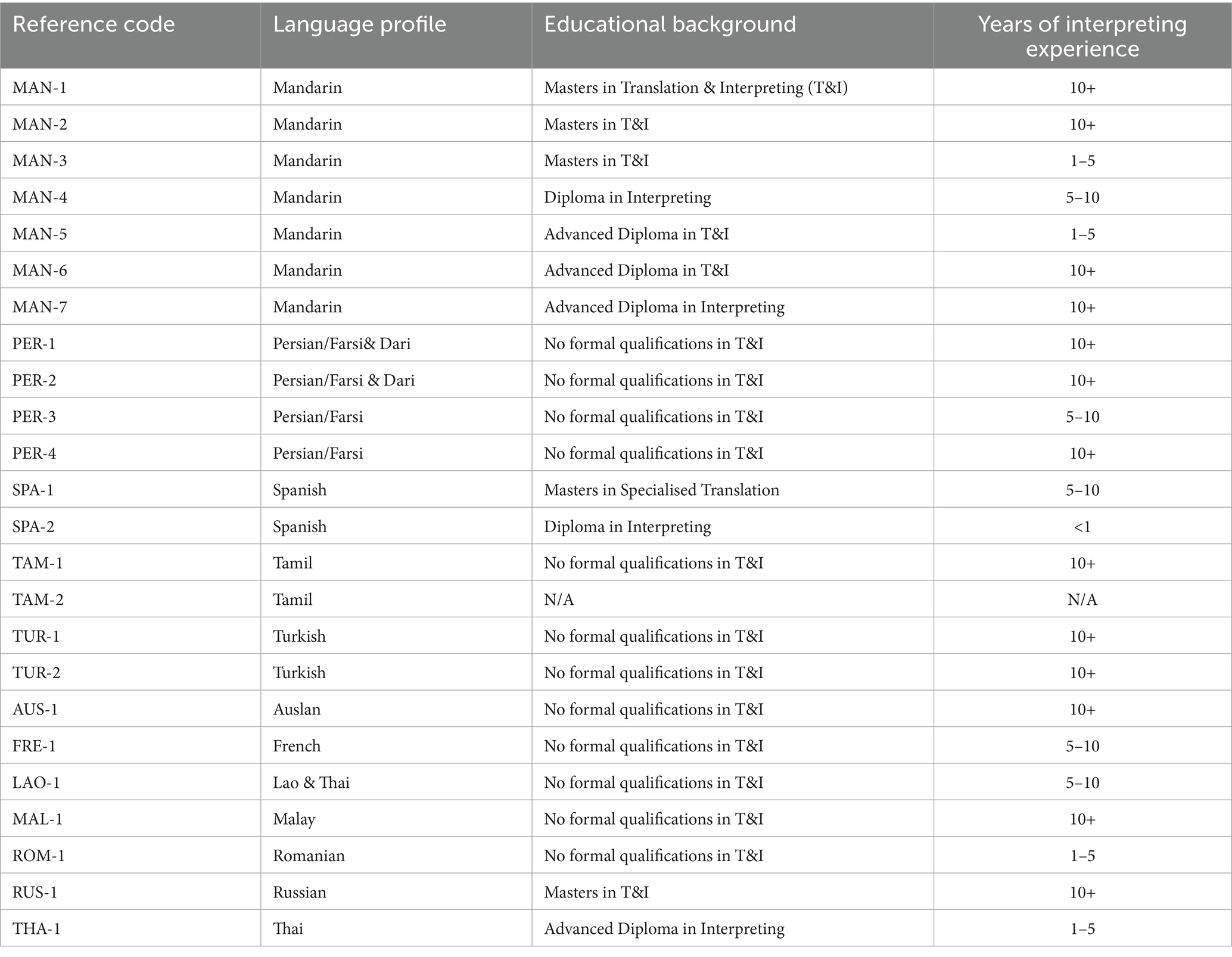

Submitted EOIs were then screened by a research assistant to confirm self-reported eligibility, and those who were deemed qualified were contacted to schedule individual online interviews. A total of 24 interpreters took part in this study, representing 12 different languages: Mandarin (n = 7), Persian/Farsi (n = 4), Spanish (n = 2), Tamil (n = 2), Turkish (n = 2), Australian Sign Language (or Auslan in short) (n = 1), French (n = 1), Lao (n = 12), Malay (n = 1), Romanian (n = 1), Russian (n = 1), and Thai (n = 1). This sample size was deemed sufficient to capture a broad range of linguistic and cultural contexts in Australia, while allowing for thematic saturation. Table 1 presents the assigned reference codes for each participant alongside their corresponding language profiles. All participants provided informed consent and received information on confidentiality measures prior to the interviews.

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews conducted online via Microsoft Teams. An interview guide (see Appendix 1) was developed to elicit responses on participants’ interpreting experiences pertinent to LGBTIQA+ topics, focusing particularly on the challenges they encountered and the strategies they employed to achieve best language service quality. The researchers divided the interview load amongst them, and were mindful that the listed questions were meant to serve as a guide for the conversation to flow organically. Voluntary contributions from participants were welcome, and the researchers took care not to stifle them. Interview length ranged from approximately 30 to 70 min. With participants’ consent, interviews were audio-recorded and subsequently transcribed for the purposes of analysis. All participant identifiers were removed and replaced with reference codes as shown in Table 1 to protect their privacy.

As the study was exploratory in nature, inductive coding for thematic analysis was employed to identify meaning units from which key themes were categorised. Guided by Braun and Clarke’s (2006, p. 87) six-step framework, we first read through the transcripts to achieve familiarity with the data. Next, initial codes were generated to represent ideas or patterns that appeared repeatedly. These codes were then grouped into broader categories or themes reflecting communication challenges and barriers to self-expression. Following this, we reviewed and refined these themes, ensuring that they are coherent and make sense in relation to the overall dataset. The final step involved defining and labelling each theme to highlight its distinct contribution to the understanding of the data.

4 Findings and discussion

These semi-structured interviews with participant interpreters elicited a mixture of their contributions on SOGIESC as people who shared the same cultural backgrounds as their LGBTIQA+ clients, as well as their first-hand experience in facilitating communication for these clients in various government service contexts. In this section, we will present two themes (1A and 2A) derived from the former to set the sociocultural contexts which these LGBTIQA+ individuals have left (i.e., their homelands) and found themselves in (i.e., diasporic ethnic communities in Australia). Then we will outline the three main parameters (1B, 2B and 3B) in relation to the challenges participant interpreters shared when working with LGBTIQA+ individuals. Further sub-themes will be presented under the main parameters, to illustrate the various nuanced challenges embedded within interpreters’ professional practise. The encounters, as reported by participant interpreters, spanned a diverse range of services in which highly sensitive or personal information was frequently shared. They included legal and asylum cases (e.g., Administrative Appeals Tribunals to decide asylum claims, legal consultations in refugee detention centres, court proceedings, communications in police stations, and visa applications), medical and mental health services (e.g., general or specialist medical appointments, hospital visits, sexual and reproductive health consultations, and counselling sessions), and social welfare and support services for victims of torture.

4.1 Sociocultural challenges left behind and re-confronted

For many LGBTIQA+ individuals, the ability to express their SOGIESC openly and freely remains a significant challenge, particularly within social and cultural environments where there is prevalent stigmatisation, conservatism and discrimination. Migration itself can be a stressful and daunting experience. LGBTIQA+ individuals pursuing so-called “sextual migration” (Carrillo, 2004; Usta and Ozbilgin, 2023) may confront additional challenges, facing oppression in the local diasporic community in Australia similar to what prompted them to leave their homelands in the first place.

4.1.1 Theme 1A: cultural taboos and social stigmas

A significant barrier to self-expression for LGBTIQA+ migrants is often linked to cultural taboos and social stigmas, the origins of which participant interpreters largely attributed to conservative values held by home societies. Participant interpreters suggested that such conservatism is particularly prevalent amongst older generations, as they tend to exhibit stronger adherence to traditional norms and beliefs, including heteronormative structures. For these older diasporic community members, preservation of such values can be a source of pride and an expression of cultural identity which override the individual’s freedom of expression with regard to self-identity. A participant interpreter pointed out that LGBTIQA+ identity “is a taboo matter specifically for the older generation” (ROM-1), which may be considered a threat to traditional values. This highlights the interplay of LGBTIQA+ identity with age, ethnicity, and migrant status in the diasporic community. For example, as observed by TUR-2:

The people that I would generally interpret for, and I assume it’s possibly the same with their languages, generally tend to be a little bit older. People in the community who, despite having been here for a number of years, obviously have not really grasped the language and so they would be more conservative. Even if they did identify or did have those sort of being a member of that community, they would not necessarily open up about that. I think they would just keep it closed because it’s just a conservative older part of the community.

Many participant interpreters shared their observations of the hesitation and silence shown by their LGBTIQA+ clients with regard to expressing their identity or articulating needs based on that identity. In several cultures, such as Chinese and Romanian, discussions of gender identity remain glaringly stigmatised: “In Chinese culture, it’s a taboo. Even if they belong to the [LGBTIQA+] community, they will not tell you” (MAN-4). Similarly, ROM-1 commented that social acceptance of LGBTIQA+ individuals was very poor and there was profound stigma preventing community members from “overtly talking about it or exhibiting it.” The following statement by TUR-2 further supports this pattern:

Even if there was potentially someone that I’m interpreting for who would like, or who needs that kind of understanding, they would not come out because it’s so looked down upon, not just by society, but even by their own family. I think religiously as well, quite religiously. So, unless it’s a very progressive, modern kind of family, I do not think most people would even come out and want to discuss that at all out of fear.

The stigma perpetuated by societal norms, religious beliefs, or even familial expectations significantly contributes to the suppression of identity expression amongst LGBTIQA+ individuals. TUR-2’s statement above highlighted the fear in the Turkish culture that prevents individuals from disclosing their identities, as a result of the absence of safe or supportive spaces.

Another interpreter pointed out the broader societal and cultural dynamics that enforce silence:

From a cultural perspective, …around the queer community there’s still fear, stigma… they are better, but they remain mostly in anonymity and even make up personal life stories different to their own so as to protect themselves and their family. In spite of recent changes, being part of the LGBTQI+ [sic] community is still taboo, and traditional structures are very much in place (PER-3).

The need for LGBTIQA+ community members to come up with alternative personal narratives demonstrates the degree of societal or cultural pressure they face. This form of self-censorship not only limits self-expression but also reinforces their invisibility within the broader community, perpetuating cycles of misunderstanding and stigma. The intersectionality embodied in these LGBTIQA+ migrants leads to double oppression, stemming from heteronormativity, cultural norms, and sometimes religious forces, from both the host country and their ethnic community embedded in it.

4.1.2 Theme 2A: discrimination

Discrimination, often a by-product of deeply rooted cultural stigma and taboo, adds another layer of obstacle to the self-expression of LGBTIQA+ individuals. In heteronormative societies, diverse SOGIESC may be shunned or even rejected by the majority, and in some countries same-sex relations are criminalised; in extreme cases, they can even be punishable by the death penalty (UNHCR, n.d.).

Participant interpreters highlighted how these cultural beliefs and institutionalised violence propelled discriminatory attitudes and behaviours. For instance:

People from the LGBTQI+ [sic] community are discriminated against. Culturally there’s a long way to go. There needs to be education. Language can be a powerful tool to change. If there’s something readily available, it’d make things a lot easier (LAO-1).

Since being transgender is not recognised in Malaysia, no one cares. [Society at large says] I have no respect for you, period (MAL-1).

These statements point to discrimination at both an interpersonal and an institutional levels, adding to existing literature about LGBTIQA+ individuals facing discriminatory treatment in health settings, including lack of clinical competence and restricted access to services (Freaney et al., 2024). More broadly, national reports in Australia reveal that displaced LGBTIQA+ individuals, even after relocation, continue to face systemic barriers to education, employment, housing, and essential services (Forcibly Displaced People Network, 2023; Migration Council Australia, 2021). As a result, LGBTIQA+ migrants may feel discouraged from seeking out social services (Migration Council Australia, 2021), feeding a cycle of invisibility and systemic exclusion.

4.2 Seeing it first-hand in the triad

After reporting on participant interpreters’ voluntary contributions on the cultural taboos, social stigmas, and associated discrimination in relation to LGBTIQA+ topics, both in terms of their home contexts and the diasporic communities in Australia, all of which not unexpected, we now turn our attention to the participants’ first-hand experiences of interpreting in encounters involving LGBTIQA+ migrants.

4.2.1 Theme 1B: linguistic challenges

4.2.1.1 Sub-theme 1.1B: complexities of gender pronouns

Interpreting gender pronouns in cross-lingual and -cultural contexts emerged as a recurring challenge raised by participant interpreters across a number of languages, reflecting deeper issues in the interplay between language, culture, and identity. For example, a neutral “they” can be used in English to circumvent binary third person pronouns (i.e., he/him and she/her), but it is difficult to achieve the same when translating into some languages, and direct translation into a plural third person pronoun simply causes confusion. As was noted by THA-1:

… personally, I was taught “he/she/it” as singular and “we/they” as plural pronouns. That’s a common problem, especially when interpreting from English to Thai if they prefer to use “they.” I think interpreters should be very careful because every time we interpret that, it’s meant to be a singular “they,” but people may take it as plural.

Further, for participants who interpret into languages which have grammatical genders, such as French, Romanian, Spanish and Russian, challenges arise when the LOTE speaker’s preferred gender is unknown. The interpreter has to decide which gender marker they should use—for example, for the word “lonely” as in “Are you lonely?”—when rendering it into LOTE (SPA-1). If it is clear to the interpreter that the LOTE client is from the LGBTIQA+ community, or briefing information provided prior to the interpreting assignment informs them of this, the interpreter can politely ask the client what their preferred pronoun is. A gender pronoun issue may arise in any encounter, catching the interpreter off guard and they may appear unskilled in handling it with sensitivity. MAN-7 shared an example they learned about during a training session provided by their interpreting agency: in a seemingly innocuous telephone interpreting assignment about a utility bill, an interpreter was struggling to ascertain the gender of the LOTE client on the other end of the line, as they had a rather low-pitched voice, so the interpreter said: “I am sorry. Are you a man or a woman?” In telephone interpreting, given the absence of visual cues, taking a third-person approach—rather than adopting the first person to interpret for the conversing parties, as per the normal protocol—can sometimes prevent confusion. In other words, rather than saying “I need a payment plan” on behalf of the client, as would be the norm in face-to-face encounters, the interpreter may say “She said she needs a payment plan” or “He said he needs a payment plan” to the utility company worker. The current authors argue that the interpreter is right in asking such a question. However, the way the question is put is inappropriate and insensitive; a more appropriate approach would be to enquire about the client’s preferred pronouns.

Some languages, including Turkish, do not have gender-specific pronouns. When interpreting into English, to ascertain the gender of a third person being referred to, Turkish interpreters normally need to either use the context of the speech or resort to explicitly asking the Turkish client. TUR-1 explained the absence of gender differentiation on a lexical and grammatical level in their language to English-speaking audiences:

Turkish is gender-neutral… [so] there are no gendered pronouns… It does not exist, it’s not possible… People who speak English may not understand gender neutral as a language concept (TUR-1).

In a similar but different way, “she” and “he” are homonyms in spoken Mandarin,3 and therefore indistinguishable, as MAN-1 states: “So, with pronouns, we do not [differentiate] in [spoken] Chinese, we just use ‘ta’. It does not really say [whether] it’s a ‘she’ or ‘he’ or ‘it’ or ‘they’ [as a gender neutral pronoun in English]…yes, it’s a bit tricky.”

Sometimes this type of challenge is encountered in the reverse when interpreting from English into languages such as Turkish and Mandarin, when a neutral term such as cousin cannot be transferred without further information on gender and kinship relations, for example, whether the cousin is from the maternal or the paternal side. In the case of Mandarin, even more information is required—about whether this cousin is older or younger than the person in question—in order to select the correct term. Such differences between source and target languages in terms of their linguistic structures and properties are not unique to the LGBTIQA+ context. As observed by Sato (2022), languages differ in terms of what information a pronoun conveys, and in certain languages, the absence of gender-specific pronouns creates unique challenges for linguistic mediation in literary works. For example, in Japanese, third-person pronouns kare (he/him) and kanojo (she/her) emerged relatively recently under the influence of European languages. Yet middle-class Japanese speakers seldom use these pronouns in everyday conversations, to avoid being perceived as showing off about their familiarity with Western languages and cultures; in a similar vein, first-person pronouns are tied to one’s social identity and can convey pragmatic cues such as hierarchical relationships and interpersonal dynamics (ibid.).

In LGBTIQA+ settings, these challenges are further magnified due to the intricacies of gender identity and self-expression, when pronouns are not only linguistic units but also deeply intertwined with an individual’s personal and social identities (Buch, 2019). Interpreting for LGBTIQA+ migrants often requires practitioners to go beyond their conventional role in mediating linguistic or cultural nuances, as they may be navigating highly sensitive and emotionally charged interactions. One participant shared:

[I had a client whose] name was Pat [changed to protect privacy]. In my culture, in my country, it is a male name. He was going to change his name to Mandy [changed to protect privacy], which is a female name. And the challenge I had, [was] sometimes because of miscommunication, I have to talk to the professional or to the service provider… I have to use something in order to refer to the client… I wanted to use a pronoun… I got stuck because if I say “he,” [the client] will get upset, and if I say “she,” then what? What will happen? (PER-1).

This Persian interpreter described a situation where the selection of a pronoun required extra care and consideration: using “she” could confuse the service provider, who was unaware of the client’s gender transition, while using “he” could cause emotional distress to the client. This dilemma highlights how pronoun use in LGBTIQA+ contexts requires interpreters to make decisions that take into consideration linguistic, cultural and interpersonal aspects.

4.2.1.2 Sub-theme 1.2B: terminology and jargon

LGBTIQA+-specific terminology presents another set of unique challenges for interpreters across spoken and sign languages, and many participant interpreters acknowledged its complex and ever-evolving nature, in both English and their LOTE. LGBTIQA+ terminology has, indeed, witnessed significant development over the past century, with changes to the meanings of existing terms and emergence of new concepts (Ferris, 2006). This linguistic fluidity has made standardisation of terminology—in both English and LOTE—not entirely attainable, and this makes it difficult to provide consistent language services that are both linguistically accurate and culturally sensitive. As a participant interpreter commented regarding the lack of uniformity in terms rendered into Malay by different interpreters: “Standardising words is great, we need consistency. Otherwise, you may not agree with me and the words I use, and it can create confusion” (MAL-1). Further, THA-1 shared:

A lot of queer jargon is being used in the queer community in Thailand, and certain things being said mean something totally different. For example, a word that used to mean “to wash the fridge” now means to give oral sex. So, from an interpreting perspective, the lack of understanding of those terms can be a problem, and seeking clarification would kind of hinder the flow of communication.

This is an example of LGBTIQA+ jargon signifying something completely different from the literal meaning of the words used. For interpreters, the lack of understanding of such terms can result in misunderstandings or inaccurate rendition, potentially leading to disastrous communication outcomes. Participant interpreters further pointed out that a superficial grasp of these terms was insufficient for conveying their contextual meanings and nuanced connotations; a deeper, more thorough understanding was required. As stated by AUS-1:

You need to understand the queer terminology… When we talk about signs, there’s a lot more to it than just the sign. The sign for “transgender’—or rather “sex change/reassignment”—used to be different [index and middle fingers of both hands “pointing” at each other in a downward motion]. And now we do this [downward motion with cascading fingers that wraps at the heart], cause that’s how I feel at heart. And understanding that is really important in case you need to unpack terms a bit. Invariably, in our Deaf community, many clients are not particularly well educated, our school system does not address the needs of our Deaf students at all, so they are not well read nor have great world knowledge, so unpacking things is very important.

Further, the following statement by TUR-1 concurs with the analysis in this sub-theme so far: “Terminology is a work in progress… There are different explanation or descriptions… for example, the word ‘queer’, it’s hard for me to know what it covers. I saw some explanations online that it covers mostly gay people, so I’m not fully sure of what it defines.”

The term “queer” is a primal example of the dynamic, complex nature of LGBTIQA+ terminology. Historically, “queer” was widely used as a derogatory label to demean individuals who did not conform to heteronormative societal norms, but in the late 20th century it was reclaimed by the LGBTIQA+ community as an inclusive identifier to encompass a wide range of gender identities and expressions (Lee and Kanji, 2017; Zosky and Alberts, 2016). Another example relates to the term “transgender”; before its introduction in 1965, the now-offensive terms “transexual” and “transvestite” were used in its place (Thelwall et al., 2023). This fluidity and the ongoing evolution of language used in the LGBTIQA+ domain pose significant challenges to interpreters, who must keep track of the changes if they are serious about the quality of the language services they provide.

4.2.1.3 Sub-theme 1.3B: lack of equivalent concepts or expressions

“Sometimes there are no equivalents [in Persian], no cultural or linguistic equivalences; that would be a challenge” (PER-2). This statement accurately reflects the linguistic reality faced by interpreters: many languages are yet to catch up with their LGBTIQA+-related vocabulary, and therefore such lack has compelled interpreters to employ other strategies such as explication (i.e., explaining the meaning of the word or phrase) or paraphrasing (i.e., using different words to express the same meaning).

Linguistically it is extremely challenging due to the limitation of the language on concepts that are sanctioned, therefore rarely talked about… In migration tribunal cases, it is often hard to interpret questions from the member when they attempt to establish when the applicant and the partner had started “living together,” as the Russian translation does not convey the same meaning. It would have to be explicated as “having a sexual partner”… (RUS-1).

In this example, although meaning is somehow transferred, one argues that the linguistic option available is not entirely ideal, as it shifts the focus and may misrepresent the intended meaning. In some cases, the absence of specific vocabulary is a reflection of the broader societal or cultural attitudes (Jaber, 2018) as language is underpinned by sociocultural norms. For example, RUS-1 also shared this insight:

In Russia, we do not actually have specific language for same sex anything. And in Russian, I would interpret for people not only from Russia but also from Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine, and other countries where they speak Russian and carry that same legacy of not having any [language] to describe the same sex relationship, history, culture, anything, and where the culture actually does not exist (RUS-1).

In societies or cultures where LGBTIQA+ identities have long been repressed or erased, relevant language used around the topic has often been shaped to disapprove, denigrate and discriminate. As a result, the terms in popular use tend to be degrading and pejorative, for example, “transgender” in Mandarin being referred to offensively as “niáng niáng qiāng” (娘娘腔), meaning “sissy boy,” “rán yāo” (人妖), literally “human monster,” or “biàn tài” (变态), literally “pervert.” In some other languages, certain LGBTIQA+ concepts or expressions are entirely non-existent. For example, Jaber (2018, p. 14) poignantly highlights the lack of queer language in Arabic—a lack which contributes to identity oppression and reinforcing the existing heteronormative power structure: “Arabic is replete with words and terms for gay and lesbian, that clarify the queer identity in terms of existing gendered and sociopolitical hierarchy. ‘Queer’ itself when translated to Arabic becomes ‘3alil’, which means, ‘defected, sickly, infectious’.” Similarly, LGBTIQA+ speakers of a wide range of languages, including Punjabi, Catalan, Polish and Welsh, all report difficulties expressing themselves in their first language due to a lack of appropriate vocabulary (Raza-Sheikh, 2020). Commenting on interlingual transfers of sexual lexicons, Wong et al. (2023, p. 12) caution that “Even when direct translation at the word-for-word level is possible, people of different cultural backgrounds may perceive the meanings of these words rather differently.” These linguacultural realities highlight how language both reflects and perpetuates societal attitudes towards LGBTIQA+ identities. For interpreters, this poses a dual challenge, regardless of whether they are an ally or otherwise: bracketing their own views and values in order to maintain neutrality, as well as persisting in updating contextual and linguistic knowledge in this topic area in order to deliver quality services that are respectful and inclusive.

Another strategy reported by participant interpreters for terms that do not exist in the target language is by “borrowing” from English, that is, directly importing the English term without translating. For languages with differing scripts, this involves transcribing the sound in English into the target language (Munday, 2012). This strategy is not new; it is often used to bring in new concepts from other languages or cultures and, over time, the imported terms become incorporated into the lexicon of the target language; and the following contribution reveals a deeper consideration when interpreting in this sensitive domain, echoing the paradox reported in Themes 1A and 2A, where LGBTIQA+ individuals re-confront oppression in the diasporic community similar to what propelled them to leave their homeland in the first place.

I mean, most of the people I interpret for come from traumatising cultural settings, so that should be considered because, while we might assume that finding a Farsi word to describe someone or a situation would “bring you back home,” that may be exactly what you are trying to avoid [to ‘feel at home,’] so you might as well stick to the English term (PER-3).

4.2.2 Theme 2B: cultural challenges

Many participant interpreters identified cultural issues as a significant aspect to be considered during their work with LGBTIQA+ clients, highlighting the sensitivities inherent in this dommain. Managing these situations often requires the interpreter to be aware of the underpinning societal norms and cultural expectations, so they can choose appropriate language expressions which balance linguistic accuracy and cultural considerations.

In highlighting the impact of cultural dynamics in interpreting for LGBTIQA+ community members, PER-2 noted the importance of empowering clients’ self-expression in a safe environment:

You need to empower them; it’s their choice to come out and they need to feel comfortable. It’s huge for them. In my culture, for example, males usually do not trust other genders. So, they test you, in the waiting room, to see what your reaction is [right before an assignment]…For example, a male was going through hormone replacement [sic] therapy and operations to become a woman. “He” [sic] told me, “I’m gay, are you ok with that?” I said yes, and asked, “Are you ok with me being a female?” They said “Yes, as long as you keep everything confidential.” It’s all very, very sensitive.

This illustrates the potential for cultural norms regarding gender identity to affect interpersonal dynamics in interpreter-client interactions. In cultures where gender roles are more rigidly defined, interpreters face challenges around exercising cultural sensitivity while maintaining professional boundaries in order to build rapport and trust with the client—a crucial factor for successful communication. Assumptions and missteps could undermine trust. The same interpreter went on to reflect on the importance of body language and collaboration during sensitive consultations:

“He” [sic] was very comfortable with the Aussie doctor, and we talked about really sensitive matters when they would usually be asked to male [patients]. I was very much in control of my body language. I said “This is my first time interpreting about this topic, can you double-check the terms I use?” (PER-2).

As discussed in Sub-theme 1.3B, many languages lack equivalent expressions for LGBTIQA+ terms, or the existing terms carry negative or inappropriate connotations. MAN-2 emphasised that choosing inclusive and culturally appropriate language is crucial to ensure effective and respectful communication:

I have to be very sensitive in choosing the right language, for example, when talking about whether they are married, talking about “partner,” a male saying he “married him,” or a female saying “she is my girlfriend” et cetera. Partner, rather than girlfriend or boyfriend, may be more suitable. I also have to be careful about religion. Some countries are strict with non-heterosexual ideology.

This sheds light on how the interpreter’s role involves being more than a linguistic conduit, but also a cultural mediator who plays an important part in bridging the gap between language and cultural expectations (Angelelli, 2004; Baraldi, 2015; Pöchhacker, 2008). Cultural attitudes towards SOGIESC issues can create complex interpersonal dynamics. In particular, cultural insensitivity from other professionals can create interactional management issues that interpreters must navigate. Misgendering, inappropriate language and judgmental body language can all make the client uneasy, preventing them from expressing themselves fully.

I’ve been in situations where clients have been from the LGBTIQ [sic] community, have been misgendered for example, or the professionals that [they] work with have shown a certain body language that made them feel awkward about it, and there’s very sensitive issues that we tread and when we are in a medical consultation, for example, or when it comes to sexual and reproductive health, it is very important for us to be aware of that, because that [sic] not only can it have negative outcomes in terms of health for that patient, but it can also mean that they will not be able to express themselves fully (SPA-1).

4.2.3 Theme 3B: psychological or emotional challenges

This theme arose outside our expectations: participant interpreters found themselves frequently facing psychological or emotional burdens when working in the LGBTIQA+ context, having to manage sensitive and emotionally charged narratives.

4.2.3.1 Sub-theme 3.1B: emotional impact/vicarious trauma

Interpreters often encounter stories of personal struggle, trauma, discrimination or even torture, and this can take an emotional toll. The accounts from participant interpreters below illustrate how exposure to clients’ distressing experiences can create emotional impact, or even vicarious trauma.

There were some emotional problems I had. Because when you listen to the people, who apply for the protection visa, what happened to them, and what they went through, that really weighs you down emotionally, because you get overwhelmed by the things they went through and that sometimes, I do not know, maybe it’s my age, I get quite emotional. I find it hard to deal with that (TUR-1).

On occasions [when interpreting for trans individuals] I became emotionally affected, several times. Once I had a court assignment, and there was this guy [sic] [a transgender woman] who came to me and said: “Look at me! Just look! Do you think I’m a man?!” And she showed me her hands, they were a woman’s hands, and her fixed hair… I had to take a break and go outside; I even cried, and I empathised with her (MAL-1).

While the interpreter’s professional role requires them to remain neutral, the gravity of some clients’ narratives can elicit a deep human response, challenging their ability to keep emotions at bay. The emotional impact of these experiences is intensified when interpreting for survivors of torture or extreme persecution, as shared by this interpreter:

I was working at STARTTS4 which assists victims of torture. There was a Haitian refugee who had been subject to atrocious torture for being queer. After a while of interpreting their story in the first person, I had to ask for [a] break as I felt I was beginning to own the issue (FRE-1).

This account highlights how interpreting in the first person—that is using “I” to convey the client’s words—can intensify the internalisation of traumatic narratives—a phenomenon reported in other studies (e.g., Darroch and Dempsey, 2016; Lai and Costello, 2021), showing that first-person interpreting increases the risk of experiencing vicarious trauma, due to interpreters’ empathic engagement as part of the cognitive process they undertake to perform their work. The interpreter’s need to take a break reflects the impact of internalising such traumatic events. The risk of “owning the issue” reflects Shakespeare’s (2012, p. 122) finding about interpreters “becoming” their clients—using their tone, body language and words, thus “losing themselves as interpreters in the interaction”—and highlights the thin line between professional empathy and personal emotional entanglement.

4.2.3.2 Sub-theme 3.2B: interpreter’s own identity

It should not be forgotten that some interpreters are from the LGBTIQA+ community themselves, and may therefore face an additional layer of complexity: reconciling their personal identity with their professional responsibilities. One interpreter articulated this tension:

As a practitioner I might have the baggage as a member of the LGBTIQA+ community—how to hide ourselves [our identity] as much as possible and perform the task in an impartial manner (MAN-3).

Interpreters who belong to the LGBTIQA+ community may feel compelled to hide their own identity to avoid any perception of bias. The requirement to maintain impartiality, central to the interpreter’s professional conduct, can conflict with their lived experience and sense of self, creating unique emotional challenges. The need to suppress aspects of their own identity may lead to emotional strain or isolation, particularly when working in scenarios with LGBTIQA+ stigmatisation. Recognising and addressing these challenges is vital for the wellbeing of interpreters and the quality of the services they provide.

5 Recommendations and conclusion

In the last section we first outlined the dominant sociocultural attitudes towards diverse SOGIESC in LOTE contexts, drawing on the contributions from participant interpreters, then we identified the key challenges these interpreters faced when working with LGBTIQA+ migrants—challenges which spanned linguistic, cultural, and psychological spheres. In this section we present insights from participant interpreters on the possible avenues for improving the status quo, and draw conclusions where appropriate.

The three spheres of linguistic challenges identified—complexities of gender pronouns, LGBTIQA+ specific terminology and jargon, and the lack of equivalent concepts or expressions—collectively point to the need for multilingual resources and targeted training and education for interpreters who work with LGBTIQA+ migrants, to enhance their understanding of the nuances around gender diversity and ability in using appropriate language. This necessary course of action is no different from those in other contextual areas in which interpreters work— such as legal or health care—in that they must be trained and become competent in using the relevant terminology for the domain, in both English and LOTE. On the other hand, intersectionality of gender diversity, sexual migration, displacement, and sociocultural conditioning—in both home and diasporic communities—makes working in this domain challenging in a unique way.

As highlighted by several participant interpreters, a standardised LGBTIQA+ glossary could serve as a practical starting point. One interpreter noted:

If there’s a term in English, there should be a description because when we talk about sex and gender orientations that people may not be familiar with, we all need a consistent understanding of what a term really means (PER-3).

In many instances, interpreters may be unfamiliar or uncomfortable with using emerging terms related to gender or sexual identity, fearing embarrassment or mistakes, particularly when there is a lack of direct equivalence in their working languages. Even with more established terms, different interpreters may use different expressions in the same LOTE, thereby creating confusion. A standardised glossary that provides clear definitions and authoritative translations could bridge this gap and help interpreters achieve linguistic accuracy and consistency. However, as was noted in Sub-theme 1.2B, LGBTIQA+ terminology is fluid and ever evolving; financial and human resources are therefore required for a sustainable solution. The www.rainbowterminology.org project in which the current authors have been involved in is a case in point. Substantial funding was secured to establish the multilingual resources website, which contains a selection of 139 English LGBTIQA+ terms, their definitions, and their translations into eight target languages. Further funding is being sought to ensure that expansion of language coverage, ongoing site maintenance, and terminological updates can continue.

Simply establishing a customised LGBTIQA+ glossary, however, is not enough, as “Glossary is hard to use out of context” (MAN-1). In this sense, targeted training is thought to be of more assistance.

When [a client] is going through difficulties related to their sexual orientation…as an interpreter, if there is certain concept that you have no idea of [sic] or have not been exposed to at all as a person, it could be challenging for the interpreter to quickly grasp the concept and facilitate the communication. Training would be very useful, and [so in the future] interpreters can function better in a similar assignment (MAN-6).

MAN-1 further suggested that “There should be workshops for practitioners with scenarios, so they can practise using them in a supportive learning environment.” This is concurred by MAN-5, who stated “Seminars for interpreters working in the field [would be helpful]. Having the glossary available, they can have a discussion, talk about their experience and exchange ideas.” Although currently there is no systematic training available, awareness of the importance is gathering momentum. For example, Sydney Local Health District, funded by the New South Wales state government’s dedicated LGBTIQA+ Health Funding Pool (2023–25), embarked on a project to develop and deliver training and resources for healthcare interpreters working in their system, aiming to “build their knowledge of the healthcare needs of LGBTIQA+ clients and to increase confidence in providing appropriate, safe and informed interpreting” (NSW Health, n.d.). Further, in 2023, eight webinars and twelve in-person workshops on inclusive and respectful communication involving LGBTIQA+ clients were delivered via a collaboration between AUSIT and ACON (formerly the AIDS Council of NSW) to a total of 540 interpreters and translators, funded by Multicultural New South Wales Health. In 2024–25, a further ten in-person workshops on interpreting for LGBTIQA+ refugees and asylum seekers—funded by Pride Foundation Australia and coordinated by the lead author of this paper—were delivered in three Australian states to a total of 122 practitioners. Under the same project, a free self-paced online training course containing five modules have also been developed, which is expected to be launched later in 2025. These initiatives have responded to practitioners’ need to learn more about the topic, and their appreciation of the important role they play in various service contexts involving queer clients.

Beyond achieving competence in the linguistic aspects of the LGBTIQA+-related domain, interpreters must appreciate the perspectives and lived experiences of LGBTIQA+ migrants in order to ensure that their interpreting is sensitive and respectful. This is, again, more likely to be achieved through targeted training and professional development, as is suggested by FRE-1:

It would be useful to have workshops and webinars with people from the queer community so as to know what the dos and don’ts are. I’m biassed and I know it can be hurtful, but I just do not know when and where it is appropriate to ask questions.

The value of hearing lived experiences from the LGBTIQA+ community is concurred by another interpreter:

I think we all become more receptive when it comes to sharing stories. If someone says, “this happened to me,” you are more likely to listen, to remember and to apply what you have heard or learnt. It opens up a new conversation (SPA-2).

Indeed, interactions with LGBTIQA+ individuals provide interpreters with opportunities to gain insights into appropriate language use and improve their ability to facilitate respectful interactions. Participant interpreters pointed out that some of their colleagues may hold deep-rooted biases themselves, and that this could prevent them from providing respectful and appropriate interpreting. Gaining first-hand insights from LGBTIQA+ community members can serve as a crucial step towards breaking that bias. It may prompt interpreters to reflect on and challenge any internalised assumptions or misconceptions they hold.

In line with this perspective, SPA-1 calls for gender perspective training for interpreters:

Interpreters and translators definitely need some kind of training with gender perspective. I think it is very important to be aware of how the way we speak can affect other people, and in this case clients or people participating in the interpreting situation… How the way we speak shapes basically our reality. If I insist on, for example, misgendering someone, I am creating a reality for me, for them, and for everyone [that is not fair] (SPA-1).

This resonates with the scholarship on feminist and queer translation practises (Castro and Ergun, 2017) which challenges language practitioners to reflect on how language can enforce or contest dominant gender and sexual norms, and how that affects marginalised identities. As observed by SPA-1, language is not a neutral medium, in that it actively shapes how people perceive and are perceived by others. In a similar vein, interpreting is also not a neutral, disinterested mediation activity (Baker, 2013), but rather, it plays a vital part in constructing knowledge, identities and culturally specific understanding (Castro and Ergun, 2017), reflecting Simmel’s (1908) conception of the “stranger” joining a triad and the possible outcome of dissolution vs. consolidation, or conflict vs. appeasement. The current authors would note, though, that diversity trainers with lived experience will be good candidates to engage, and caution should be exercised not to place undue burden on LGBTIQA+ community members to “educate” the “uneducated.” The inevitable reality of outing oneself when accepting such an engagement should also be borne in mind; sensitivity should be strictly exercised when approaching individuals, so they do not feel pressured; and both complete voluntariness and fair compensation for their time and effort are not negotiable.

Apart from targeted training and professional development on LGBTIQA+ vocabulary, gender perspective, and inclusive language use, several participant interpreters raised the importance of pre-assignment briefings to include information about the client’s gender identity when the assignment needs such information to be successful, for example, in sexual health or counselling settings. This would allow interpreters with strong biases to opt out, preventing disrespectful or harmful interactions from taking place. For example:

Something good would be to include a note saying the person is from the LGBTIQ+ [sic] community, so that if you are biassed or have “strong views” about the community, you will not take the job (PER-4).

Further, using appropriate pronouns and respectful language in relevant service contexts provides validation to the queer client, and this is conducive to fostering their sense of safety and aiding the smooth flow of subsequent communication. As PER-2 said:

Provide a briefing. If client is from the queer community, acknowledge it so that the client does not feel embarrassed. Be direct. Persian and Dari are very indirect, so we can use the directness of English to acknowledge. People need to be themselves, their identity [needs to be] acknowledged and respected here.

The importance of briefings for interpreters has long been recognised, in that they improve accuracy and efficacy of interpreting (Díaz Galaz, 2011; Hale, 2013) by enabling the interpreter to research and practise LGBTIQA+ terms beforehand, reducing the risk of miscommunication. On the other hand, it should also be noted that interpreters need to navigate these interactions with heightened sensitivity, in order to avoid “outing” clients or violating their privacy, when such information is not of concern in the encounter if, for any reason, the interpreter comes to possess that information.

6 Limitations and future directions

It is important to acknowledge that our study took place in the Australian context, reporting on challenges faced by interpreters mediating communication for queer migrants in an English-dominant service environment. We recognise that there may appear to be an underlying suggestion in our findings that the English language is a more effective option for expressing diverse identities and discussing LGBTIQA+ experiences. English, however, is not a neutral medium but, rather, an embodiment of cultural and ideological domination, connected to colonial and racialised hierarchies (Pennycook, 1994, 1998; Phillipson, 1992, 2010). Research in lavender—that is, queer—linguistics demonstrates that a wide range of languages offer well-developed terminologies and conceptual frameworks for understanding diverse gender and sexual identities (e.g., Cage, 2003; Hart and Hart, 1990; Stief, 2017; Ulla et al., 2024). We fully recognise this linguistic richness and do not wish to dismiss its significance. Rather, our recommendation for a standardised English glossary of LGBTIQA+ terms with consistent definitions and translations is motivated by practical considerations based on the specific challenges identified by our participants. The interpreters in our study reported lacking foundational knowledge of queer issues and experiences, which could lead to tension or conflicts in the communicative encounters and hinder effective, dignified service delivery. In light of this, our proposed glossary is intended to serve as a pragmatic tool in addressing these immediate professional needs within the Australian service context. Future research would benefit from examining the dynamics of interpreter-mediated communication for LGBTIQA+ migrants in other geographical locations with different institutionally dominant languages, migration policies, public service infrastructure, and sociocultural attitudes towards queer individuals.

Another limitation of this study is that it relied solely on the perspectives of interpreters, without incorporating the voices of LGBTIQA+ migrants, nor those of the service providers. Although the current researchers are fully cognisant that queer migrants should not unfairly bear the burden of “educating the uneducated,” where they may out themselves or be re-traumatised in the process of contributing to this area of research; there should be scope for future studies that are carefully designed and respectfully conducted. While interpreters bear witness to the challenges faced by queer migrants as a result of cultural and linguistic discordances, their contributions cannot fully reflect queer individuals’ lived experiences, communication struggles, or satisfaction level with services received from both interpreters and public service providers. Similarly, the study did not canvas the perspectives of public service providers who are on the other receiving end of the mediated communication. They may be able to provide further assessment of the effectiveness of communication, facilitating data triangulation to identify gaps between interpreting strategies and clients’ needs. Ultimately, only when all viewpoints from the communication triad are properly accounted for can comprehensive improvement be achieved for all parties involved.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by RMIT University Human Research Ethics Committee Approval No. EC00237. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ML: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. EZ: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. EG: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was conducted as part of the project entitled “Finding the words is easy--or is it?” funded by the City of Melbourne’s Social Partnerships Program 2021-23 under #SPP-2021/23-040.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the interpreters who took part in this study and shared their valuable insights.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^This article adopts the initialism of LGBTIQA+ to denote Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, Queer/Questioning and Asexual, and “plus” to cover all other gender diverse individuals. The authors acknowledge that there is no single, universally accepted initialism, and many variations are seen, for example, from LGBT, LGBTI and LGBTQ, with or without the “+,” to 2SLGBTIQA + (adding “2S” to represent “two-spirit” at the front). We also acknowledge that this topic field and its relevant terms are not static and are evolving all the time.

2. ^This participant is coded under Lao, although this person also has another working language, Thai.

3. ^Mandarin is the standardised spoken form of Chinese and one of its many spoken varieties from different regions such as Cantonese, Shanghainese and Hokkien. The pronoun challenges discussed here pertain specifically to Mandarin as a spoken language.

4. ^STARTTS stands for The NSW Service for the Treatment and Rehabilitation of Torture and Trauma Survivors.

References

ABS. (2022). “Cultural diversity of Australia: Information on country of birth, year of arrival, ancestry, language and religion.” Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/cultural-diversity-australia (accessed December 20, 2024).

ABS. (2024a). “ABS Releases First Ever Estimates of LGBTI+ Australians.” Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/abs-releases-first-ever-estimates-lgbti-australians (accessed December 19, 2024).

ABS. (2024b). “Estimates and Characteristics of LGBTI+ Populations in Australia - Data on Gender, Trans and Gender Diverse, Sexual Orientation, and People Born with Variations of Sex Characteristics.” Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/estimates-and-characteristics-lgbti-populations-australia/latest-release (accessed December 19, 2024).

ABS. (n.d.) “Population: Census. ABS.” Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/population-census/latest-release (accessed December 20, 2024).

Aiyar, R. (2020). ‘It’s better to have support’: Understanding wellbeing and support needs of gender and sexuality diverse migrants in Australia. Adelaide: The University of Adelaide.

Albuquerque, A., de Lima Garcia, G. C., da Silva Quirino, G., Alves, M. J. H., Belém, J. M., dos Santos Figueiredo, F. W., et al. (2016). Access to Health services by lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: systematic literature review. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 16, 2–10. doi: 10.1186/s12914-015-0072-9

Amos, N., Hart, B., Hill, A. O., Melendez-Torres, G. J., McNair, R., Carman, M., et al. (2023). Health intervention experiences and associated mental Health outcomes in a sample of LGBTQ people with intersex variations in Australia. Cult. Health Sex. 25, 833–846. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2022.2102677

Angelelli, C. V. (2004). Revisiting the interpreter’s role: A study of conference, court, and medical interpreters in Canada, Mexico, and the United States, vol. 55. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Asquith, N. L., Collison, A., Lewis, L., Noonan, K., Layard, E., Kaur, G., et al. (2019). Home is where our story begins: CALD LGBTIQ+ people’s relationships to family. Curr. Issues Crim. Just. 31, 311–332. doi: 10.1080/10345329.2019.1642837

Bahadır, Ş. (2010). The task of the interpreter in the struggle of the other for empowerment. Transl. Interpret. Stud. 5, 124–139. doi: 10.1075/tis.5.1.08bah

Baker, M. (2013). Translation as an alternative space for political action. Soc. Mov. Stud. 12, 23–47. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2012.685624

Baraldi, C. (2015). An interactional perspective on interpreting as mediation. Lang. Cult. Mediat. 1, 17–36. doi: 10.7358/lcm-2014-0102-bara

Bernstein, M. (1997). Celebration and suppression: the strategic uses of identity by the lesbian and gay movement. Am. J. Sociol. 103, 531–565. doi: 10.1086/231250

Bloomberg, L. D., and Volpe, M. (2012). Completing your qualitative dissertation: A roadmap from beginning to end. 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Bond, K. S., Jorm, A. F., Kelly, C. M., Kitchener, B. A., Morris, S. L., and Mason, R. J. (2017). Considerations when providing mental Health first aid to an LGBTIQ person: a Delphi study. Adv. Ment. Health 15, 183–197. doi: 10.1080/18387357.2017.1279017

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bristol, S., Kostelec, T., and MacDonald, R. (2018). Improving emergency Health care workers’ knowledge, competency, and attitudes toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients through interdisciplinary cultural competency training. J. Emerg. Nurs. 44, 632–639. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2018.03.013

Buch, L. A.. (2019). “The effect of gender neutral pronouns on non-binary gender identity experience.” La Jolla, California: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

Cage, K. (2003). Gayle: The language of kinks and Queens: A history and dictionary of gay language in South Africa. Johannesburg: Jacana Media.

Carman, M., Farrugia, C., Bourne, A., Power, J., and Rosenberg, S. (2020). Research matters: How many people are LGBTIQ? Melbourne: Rainbow Health Victoria.

Carrillo, H. (2004). Sexual migration, cross-cultural sexual encounters, and sexual Health. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 1, 58–70. doi: 10.1525/srsp.2004.1.3.58

Castro, O., and Ergun, E. (2017). “Introduction: re-envisioning feminist translation studies: feminisms in translation, translations in feminism” in Feminist translation studies: Local and transnational perspectives. eds. O. Castro and E. Ergun (New York: Routledge), 1–11.

Clark, F. (2014). Discrimination against LGBT people triggers Health concerns. Lancet 383, 500–502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60169-0

Commonwealth of Australia. (2019). “Actions to support lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and gender diverse and intersex elders: a guide for aged care providers.” Canberra. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2019/12/actions-to-support-lgbti-elders-a-guide-for-aged-care-providers.pdf (accessed November 30, 2024)