- Department of Law, Economics and Cultures, University of Insubria, Como, Italy

Introduction: This study examines how cultural producers perceive and interpret the UNESCO Creative City designation, focusing on Como, Italy, following its 2021 inclusion in the network. Anchored in critical urban theory and cultural sociology, the research investigates how institutional narratives of creativity intersect with the interpretive frameworks through which cultural actors understand their work.

Methods: The research employed ethnographic methods, including semi-structured interviews with diverse cultural producers (theatrical practitioners, visual artists, craftspeople, musicians, filmmakers, venue operators), participant observation at cultural events, and document analysis. Data were analyzed using constructivist grounded theory principles.

Results: Findings reveal three interrelated disjunctures: (1) institutional disconnection, expressed through parallel cultural worlds governed by conflicting evaluative logics; (2) spatial constraints, exacerbated by tourism intensification, that undermine conditions for creative practice; and (3) network fragmentation, which cultural producers seek to overcome through emergent forms of solidarity. The study demonstrate these tensions exist alongside the potential for virtuous relationships between Creative City designations and cultural tourism development, while also reflecting how local cultural forms are transformed into symbolic capital within broader urban development projects.

Discussion: The study highlights significant tensions between top-down policy frameworks and bottom-up cultural labor, showing how local creative communities actively reinterpret, resist, and reshape institutional discourses. By centering cultural producers’ meaning-making practices, the research contributes to debates on culture’s instrumentalization in urban governance and offers insights for more inclusive, sustainable, and dialogic cultural policy approaches.

1 Introduction

This study examines the complex relationship between institutional narratives of creativity and the lived experiences of cultural producers in Como, Italy, following its 2021 designation as a UNESCO Creative City. Situated at the intersection of global cultural policy, urban development, and everyday creative practice, the research interrogates how transnational cultural frameworks are experienced, interpreted, and negotiated by actors in specific sociocultural contexts.

The UNESCO Creative Cities Network (UCCN, established 2004) exemplifies urban governance approaches positioning creativity as a sustainable development driver. Como’s designation in ‘Crafts and Folk Art,’ centered on silk traditions, offers a rich case study at a critical development juncture characterized by economic restructuring, tourism intensification, and contestation over urban space and cultural identity. Drawing on interviews with a strategically diverse sample of cultural producers—including event organizers, cultural operators, theatrical practitioners, musicians, filmmakers, and other creative professionals—alongside participant observation at cultural events and document analysis, the research employs constructivist grounded theory principles. The ethnographic research reveals systematic patterns in how cultural producers experience and make sense of the Creative City designation. Rather than imposing predetermined analytical frameworks, the study follows participants’ own meaning-making processes to identify the interpretive schemas through which they understand their relationship to institutional structures.

By examining the disjunctures between official creative city narratives and the everyday realities of cultural production, this research aims to contribute to critical debates about the instrumentalization of culture in urban governance and the potential for cultural and creative industries to catalyze transformative change. The findings challenge dominant assumptions underlying creative city policies while offering crucial insights for reconceptualizing cultural policy approaches that meaningfully engage with local creative communities’ perspectives, aspirations, and forms of resistance.

2 Context and background

2.1 Urban space and cultural production

Urban environments have increasingly become privileged sites where cultural value is negotiated, contested, and transformed through complex intersections of institutional rationalities and everyday creative practices. This study situates itself at the nexus of several theoretical traditions that offer complementary analytical frameworks for understanding these dynamics, while maintaining epistemological reflexivity regarding the emergence of theoretical insights from empirical observation. The evolution of critical urban theory has yielded conceptual tools for examining how cultural policies operate within contemporary urban configurations. This intellectual tradition, originating in Lefebvre’s (1991) production of space thesis, Harvey’s (1989) analysis of urban entrepreneurialism, and elaborated through Brenner’s (2009) and Marcuse’s (2010) interrogations of neoliberal urbanization, explored how urban space functions simultaneously as a medium and outcome of social relations, economic processes, and political projects, conceptualising cultural production not as autonomous from broader urban processes but as fundamentally imbricated within patterns of capital accumulation, spatial restructuring, and symbolic legitimation. The creative city paradigm can thus be located within longstanding tensions between culture’s intrinsic societal value and its instrumental mobilization within regimes of urban governance (Zukin, 1995; McGuigan, 2004; Miles, 2007).

Complementing this macro-structural perspective, Bourdieu (1993, 1996) field theory conceptualizes cultural production within relatively autonomous fields structured by internal logics and forms of capital. This framework helps analyze how UNESCO designations introduce symbolic recognition into local contexts, potentially reconfiguring legitimation hierarchies. The concept of habitus, in particular, illuminates why cultural producers interpret creative city frameworks in heterogeneous ways beyond simple resistance or accommodation (Bourdieu, 1990; Swartz, 1997).

Becker’s (1982) ‘art worlds’ approach enriches this analytical framework by foregrounding the collective, cooperative dimensions of cultural production. Eschewing romantic notions of artistic individualism, Becker demonstrated how cultural works emerge through complex networks of cooperation among diverse actors, including not only artists but also intermediaries, technical specialists, patrons, audiences, and institutional gatekeepers. This perspective elucidates how creative city policies may reconfigure established patterns of collaboration within local cultural ecosystems, potentially catalyzing novel cooperative arrangements while disrupting existing relational networks. Becker’s emphasis on conventions—shared understandings and tacit agreements that facilitate coordination among participants in art worlds—provides a conceptual bridge between institutional frameworks and the microsociology of everyday creative practice.

Building on these foundations, Crane (1992) explored how cities operate as hubs of cultural innovation, where global and local cultural currents converge. Her analysis of cultural networks and urban creative dynamics reveals how municipal policies mediate between transnational frameworks and local specificities. DiMaggio’s (1982) work complements this perspective, by emphasizing the role of institutional gatekeepers and cultural entrepreneurs in shaping creative city initiatives and by underscoring the organizational structures that negotiate between global imperatives and localized practices, illustrating how institutional frameworks influence urban cultural production.

More recent theoretical developments have further nuanced our understanding of how cultural production operates within contemporary urban configurations. Western-centric conceptualizations of creative labor have been critiqued, with perspectives from non-metropolitan contexts revealing more diverse patterns of cultural work characterized by informality, relationship-based economies, and alternative value systems (Alacovska and Gill, 2022). This ‘ex-centric’ perspective helps explain why cultural producers in places like Como might develop practices and interpretive frameworks that deviate from institutional models of creativity, suggesting the importance of attending to Como’s particular socio-spatial configurations rather than presuming universal applicability of creative city frameworks.

However, while drawing on these established views, this study maintains a methodological commitment to theoretical sensitivity—allowing conceptual understanding to emerge from sustained empirical engagement with the research context. Rather than imposing theoretical templates onto empirical materials, the analysis remains attentive to how local cultural producers themselves construct meanings and interpretive frameworks in response to the UNESCO Creative City designation. This approach acknowledges both the analytical value of existing theoretical perspectives and the epistemological necessity of remaining receptive to context-specific dynamics that may necessitate conceptual innovation or refinement. By integrating macro-structural analyses with micro-level insights from cultural sociology, this study seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay between creativity, urban space, and governance.

2.2 UNESCO Creative Cities Network: institutional architectures and discursive contestations

The UNESCO Creative Cities Network (UCCN) constitutes a paradigmatic example of how supranational cultural governance increasingly attempts to shape urban development trajectories through designation regimes, policy circulation mechanisms, and transnational knowledge networks. Established in 2004 amid UNESCO’s institutional recalibration toward cultural diversity as a developmental resource, the UCCN has undergone significant expansion, incorporating 350 cities as of 2025 (UNESCO, 2025). The network’s taxonomic framework categorizes urban centers according to eight creative domains—Crafts and Folk Art, Design, Film, Gastronomy, Literature, Media Arts, Music, and Architecture—reflecting UNESCO’s conceptualization of creativity as simultaneously domain-specific in expression yet universally applicable as a catalyst for urban revitalization. The UCCN’s institutional architecture operates through a complex multi-scalar governance apparatus that traverses global, national, and local administrative domains. The UCCN’s objectives outline an ambitious agenda that integrates cultural, social, economic, and environmental dimensions. The Network aims to strengthen cultural goods development, foster creativity among marginalized groups, expand cultural participation, and integrate cultural practices with sustainable urban development (UNESCO, 2023). These objectives reflect UNESCO’s evolution toward positioning culture as both enabler and driver of sustainable development, beyond mere preservation (Duxbury et al., 2016; UNESCO, 2018). This reframing aligns with broader shifts in international development discourse epitomized by the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, which explicitly recognize cultural components within sustainable urban development frameworks (Wiktor-Mach, 2020).

The creative cities paradigm, from which the UCCN emerges, is deeply rooted in urban theory and cultural policy discourse. Its intellectual genealogy can be traced to early reflections on urban creativity (Mumford, 1938), later expanded through analyses of urban diversity and innovation (Jacobs, 1961) and formalized as a strategy for post-industrial urban renewal (Landry and Bianchini, 1995). This conceptual trajectory gained widespread recognition—though in a significantly reconfigured form—through the ‘creative class’ thesis, which asserted that urban prosperity hinges on attracting mobile creative professionals by fostering cultural vibrancy and high quality of life (Florida, 2002; Peck, 2005). Critical scholarship scrutinized the assumptions, policy applications, and socio-spatial consequences of the creative city paradigm. Research revealed how such policies often neglected the production systems and specialized labor markets crucial to cultural economies (Scott, 2006, 2014). Others critiqued their consumption-driven bias, advocating instead for stronger cultural production infrastructures and labor conditions (Pratt, 2008, 2011). These critiques exposed how creative city frameworks prioritized aesthetic experiences while overlooking structural conditions for cultural production. Scholars highlighted tensions between discourse and implementation, noting the persistence of standardized ‘cultural planning templates’ despite claims of distinctiveness (Evans, 2009; Mulero and Rius-Ulldemolins, 2017). While narratives emphasized inclusivity, entrenched inequalities persisted in creative sector employment (Oakley, 2004). Interestingly, studies also highlighted how these policies provoked creativity through opposition, as subcultures resisted the hegemonic narratives of urban creativity (Mould, 2015).

A major critique linked the creative city paradigm to neoliberal urban governance, where strategies commodified urban spaces within inter-city competition rather than fostering organic cultural development (Peck, 2005). Others argued that creative city discourses reflected ‘market reasoning,’ valuing cultural expressions primarily for economic gains over intrinsic social significance (McGuigan, 2009). More recent scholarship explored the geopolitics of creative city designations within global hierarchies. Networks like UCCN functioned as ‘city diplomacy,’ legitimizing urban centers in transnational governance (Acuto and Rayner, 2016), and studies underlined how these frameworks reinforced Western models as benchmarks for ‘world-class’ status (Robinson, 2006), often acting as ‘certification regimes’ that constrained alternative urban development paths (Kuymulu, 2013). Empirical research on UNESCO Creative Cities underscored the variability of local engagement. Some studies showed how cultural producers exerted forms of ‘creative resistance,’ simultaneously contesting and leveraging institutional resources (Comunian, 2011; Comunian and Mould, 2014). Recent scholarship has further developed critical perspectives on the creative city’s paradigm through more nuanced analyses of implementation and impacts. A comprehensive bibliometric analysis of research on creative cities identifies key thematic clusters, research hotspots, and significant gaps in the literature (Ren et al., 2023), revealing how creative city research has evolved from primarily theoretical conceptualizations toward more empirical examinations of implementation challenges and outcomes. These insights underline the value of ethnographic approaches in examining how creative city designations were negotiated and reshaped locally. The UCCN, situated at the intersection of global governance, urban policy, and local creative economies, promoted cultural diversity and sustainable development but unfolded within specific political-economic contexts, generating diverse outcomes. Examining these dynamics requires a multi-scalar perspective that considers both institutional frameworks and the lived experiences of those engaging with them—a lens through which this study approaches Como’s recent designation.

2.3 Como as a UNESCO Creative City

The city of Como, situated at the southern tip of its eponymous lake in northern Italy’s Lombardy region, represents a distinctive case study in urban cultural transformation, characterized by complex intersections of industrial heritage and tourism development. Its socio-economic trajectory has been deeply influenced by its historical prominence in silk production, which dominated the city’s economy and social fabric from the late medieval period through the twentieth century, establishing Como as a leading European textile center. By the mid-nineteenth century, the city had developed a comprehensive silk ecosystem, spanning sericulture, spinning, weaving, and design, with specialized industrial districts emerging across the region. Initial challenges arose in the 1950s and 1960s with increasing international competition, but the most profound transformations occurred from the late 1970s onward, as shifting production paradigms drove a gradual process of deindustrialization. By the late twentieth century, employment in the textile sector had declined significantly, marking a major economic restructuring (Alberti, 2007; Cani, 2016). Despite this contraction, Como’s silk industry has persisted through strategic specialization in high-value design and luxury production, and the industrial restructuring has also left a complex material and symbolic legacy, including an extensive architectural heritage of former manufacturing sites.

Como’s post-industrial transition accelerated in the 1990s, marked by a pronounced shift toward tourism-driven development. Its location on Lake Como—renowned for its scenic beauty and aristocratic villas—has positioned the city as a major tourist destination, with annual visitors rising from approximately 215,000 in 1998 to over 1.4 million by 2019. Employment growth in the tourism sector over the past ten years has been 48% (Grechi and Segato, 2024). This expansion has produced complex socio-spatial effects, including seasonal employment patterns, rising property values in the historic center, and increasing pressure on urban infrastructure. Recent observations indicate that between 2023 and 2024 alone, average residential property prices in the historic center rose by 17% (La Provincia di Como, 2025), significantly outpacing regional trends and raising concerns about potential displacement of long-term residents (Raffa, 2024a). Between 2010 and 2020, Como’s historic center saw a sharp decline in traditional workshops and small-scale manufacturing establishments, while tourism-related businesses expanded significantly (Barbieri et al., 2017). These shifts have raised concerns about tourism-driven gentrification, wherein tourism development reshapes urban space in ways that prioritize visitor consumption over resident needs and traditional economic activities (Gravari-Barbas and Guinand, 2017).

Recent data highlights key trends in Como’s creative sector. In 2023, employment in ‘core’ cultural industries exceeded 8,200 workers, comprising 3.4% of the province’s total workforce. Como ranks first nationally for employment concentration in ‘architecture and design’ and second in ‘publishing and printing.’ However, employment in core cultural industries has declined compared to both 2019 (−2.5%) and 2022 (−2.9%). In contrast, the ‘creative-driven’ sector—encompassing businesses outside traditional cultural domains that integrate creative processes—employed over 6,400 people in 2023 (2.6% of the local workforce), reflecting a 2.8% increase from both 2019 and 2022. Among Como’s cultural enterprises, ‘architecture and design’ dominates, accounting for 47.6% of all businesses in the sector (Unioncamere and Fondazione Symbola, 2024).

Como’s formal engagement with the UNESCO Creative Cities framework began in 2017, when municipal authorities, in collaboration with local educational institutions and cultural associations, initiated the application process for designation within the ‘Crafts and Folk Art’ category. The designation recognizes Como as the leading city of Italy’s ‘Textile Valley,’ a territorial district with a historical vocation for textile tradition encompassing the provinces of Como and Lecco. The application emphasized Como’s historical significance in silk production, positioning this heritage not merely as an industrial legacy but as a living tradition of craft knowledge and artistic practice. The silk production sector still holds particular significance, with 70% of European silk produced in the Como textile district, which comprises 1,376 companies (down from 1,424 in 2019) employing 15,515 workers (Como Creative City, 2025). This concentration of expertise and production capacity in high-value textiles underscores the city’s distinctive position within global creative production networks, particularly for complex fabrications requiring specialized competencies developed over generations (Camera di Commercio di Como-Lecco, 2024).

Following its UNESCO designation, Como established a formal governance structure to coordinate its engagement with the international network. This includes political representation by the Municipality of Como, and operational management by a Focal Point based at Fondazione Alessandro Volta. Within the ‘Crafts and Folk Art’ cluster, Como has defined its focus around textile craftsmanship, design, the circular economy, and sustainable fashion. Since its designation, stakeholders within the Creative City governance framework have organized numerous events, including educational initiatives on sustainability, training programs, cultural dissemination projects, and international collaborations. Notable efforts include the ‘Circular Textile Valley Italy’ initiative, the ‘Trame Lariane’ educational program integrating art and fashion, and participation in the Creative Cities of Crafts & Folk Art annual meeting in Jinju, Korea. Como’s engagement reflects the broader objectives of the UNESCO Creative Cities Network, which, by 2022, comprised 295 cities spanning seven creative sectors. Member cities exchange best practices to integrate culture into sustainable urban policies and contribute to the United Nations 2030 Agenda. Key challenges include bridging cultural and geographical divides, necessitating a shared framework for collaboration. Early implementation efforts have combined institutional initiatives with grassroots activities, including the launch of the ‘Como Creative Week’ festival (2022), an international textile artist residency, and a digital documentation project on traditional silk-making techniques.

Como’s experience as a UNESCO Creative City can be situated within emerging research on the relationship between creative city designations and tourism development. Recent studies have underlined the complex dynamics between cultural governance, tourism intensification, and local creative ecosystems (Raffa, 2024b). Other studies have demonstrated the potential for virtuous relationships between UNESCO Creative City designations—especially within the Craft and Folk Art cluster—and cultural tourism development (Arcos-Pumarola et al., 2023). Research has also highlighted these designations’ instrumental role in city branding processes (Gathen et al., 2021), while other studies explored how local cultural forms are transformed into symbolic capital and subsequently mobilized within broader urban development projects (Kinkaid and Platts, 2024). Advocates for transformational tourism policies argue for bridging regenerative approaches with local cultural needs, challenging dominant models that prioritize visitor economies over resident creative practices. These perspectives on regenerative tourism offer valuable frameworks for understanding the tensions between tourism development and cultural sustainability in UNESCO Creative Cities like Como. In its context, the UNESCO designation intersects with broader transformations in the city’s economic base, urban fabric, and cultural identity, arriving at a pivotal moment in the city’s trajectory. As outlined in Como’s UNESCO framework, its distinctive approach emphasizes synergies between culture, industry, and craftsmanship, leveraging the diverse creative competencies associated with Made in Italy excellence. This context presents a valuable case for examining how global cultural policy frameworks are locally interpreted, negotiated, and adapted. Understanding these dynamics requires close attention to the relationships between symbolic policy frameworks and cultural labor realities—a central focus of this study’s ethnographic investigation.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design and epistemological foundations

This study is situated within an interpretive research paradigm, drawing on constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014) and phenomenological inquiry (van Manen, 2016) to examine the intersubjective meaning-making processes through which cultural producers interpret and negotiate the UNESCO Creative City designation in Como. This methodological approach acknowledges the socially constructed nature of reality while remaining attentive to the lived experiences and perceptual schemas through which social actors make sense of institutional frameworks (Spillman, 2020). Interpretive approaches are deemed particularly appropriate for investigating the dialectical relationship between structural conditions and phenomenological experiences—a relationship central to understanding how global cultural policy frameworks are mediated through localized meaning-making practices.

The research design ‘bricolage’ approach, strategically integrating methodological elements from grounded theory and phenomenological inquiry to develop a nuanced understanding of participants’ lifeworlds. Grounded theory methodology, with its emphasis on theoretical emergence through iterative analysis (Glaser and Strauss, 1967), provides systematic analytical procedures for developing conceptual insights from empirical data. Simultaneously, phenomenological perspectives (Schutz, 1967; Smith et al., 2009) inform the study’s attention to how participants ascribe meaning to their experiences and position themselves in relation to institutional frameworks.

Such integration of approaches acknowledges the complex, multi-layered nature of social phenomena and the interpretive acts inherent in their investigation (Alvesson and Sköldberg, 2018).

3.2 Data collection and analysis

The research employed ethnographic methods to investigate how cultural producers experience, interpret, and negotiate the UNESCO Creative City designation within their professional practices and meaning-making processes. Primary data collection occurred between September 2024 and January 2025, encompassing multiple sites of cultural production across Como’s urban terrain. The ethnographic approach, informed by Hammersley and Atkinson’s (2019) emphasis on naturalistic inquiry in contextualized settings, facilitated investigation of both discursive articulations and embodied practices through which participants engage with creative city frameworks.

The central data collection method consisted of 15 semi-structured interviews lasting between 60 to 85 min. Participant selection followed theoretical sampling principles (Charmaz, 2014), whereby initial participants were recruited through institutional networks and associations, with subsequent participants selected based on emerging analytical categories and the need to explore contrasting perspectives. This approach aligns with ‘gradual selection’ (Flick, 2018)—a process whereby sampling decisions evolve in response to developing theoretical insights rather than being predetermined at the study’s outset. The participant constellation deliberately encompassed diverse positions within Como’s cultural ecology, resulting in a final sample of 15 participants: one theatrical practitioner, one visual artist, two craftspeople specializing in textile traditions, two musicians (one of whom organizes a local festival), one video maker/audiovisual producer, one visual artist/graphic designer, one independent cinema operator, five cultural venue operators/representatives from cultural associations, and one designer. Within this group, three participants simultaneously functioned as event organizers, and one held dual professional identity as an architect and designer. The identification of subsequent participants combined researcher judgment based on emerging analytical needs with snowball sampling techniques, wherein initial participants recommended others who could provide additional perspectives on identified themes.

Interviews were conducted in Italian. Interview protocols were constructed following Kvale and Brinkmann (2015) principles for interviewing, utilizing open-ended questions designed to elicit detailed accounts of participants’ lived experiences and meaning-making processes. These protocols were iteratively refined throughout the research process, reflecting the emergent nature of theoretical sampling in grounded theory methodology (Corbin and Strauss, 2015). Interview data were captured through audio recordings subsequently transcribed verbatim, or through detailed contemporaneous notes where recording was not possible or appropriate. Interview analysis attended to ‘active interviewing’ (Holstein and Gubrium, 1995), acknowledging that interviews themselves constitute interpretive occasions where meanings are actively constructed rather than merely extracted. Given the close-knit nature of Como’s cultural field and the relatively small size of its art world, detailed tabulation of participant demographic characteristics is deliberately avoided to minimize the risk of inadvertent identification. In this context, generalized professional categories are considered more ethically appropriate than specific demographic indicators that, while potentially of interest to readers, are not analytically essential to the study’s central research purposes.

The analytical process employed constructivist grounded theory principles (Charmaz, 2014), beginning with line-by-line initial coding that stayed close to participants’ language. This early coding phase generated numerous descriptive codes directly connected to participants’ expressions and experiences. For instance, when analyzing the transcript of a music event organizer who stated, “Cultural resources go to an extremely limited number of entities. Most of these do not even create cultural proposals,” I initially coded this segment as ‘perception of resource inequality’ and ‘questioning legitimacy of resource recipients.’ In another example, a visual artist’s statement that “you immediately get the feeling that no one was waiting for you, no one welcomes you” was initially coded as ‘experiencing social coldness’ and ‘perceiving barriers to integration.’

These initial codes were systematically compared across interviews through constant comparative analysis. During focused coding, I consolidated related initial codes into more conceptual categories. For example, the following memo excerpt illustrates this analytical progression:

Memo: Resource Distribution Patterns (20/12/2024). After comparing codes across interviews 3, 5, and 8, I’m noticing recurring patterns in how participants describe resource allocation. Codes like ‘perception of resource inequality,’ ‘identifying funding recipients,’ and ‘questioning selection criteria’ suggest a broader category related to how cultural resources are distributed. Participants consistently describe experiencing institutional decision-making as opaque and disconnected from their needs. This appears to be more than just frustration with limited resources—it reflects a deeper sense that different evaluative frameworks are operating. Tentatively labeling this focused category as ‘resource allocation asymmetry’ to capture both material distribution and the interpretive frameworks that legitimize it.

Through theoretical coding, I examined relationships between focused categories. The following memo excerpt shows how I developed connections that eventually led to the theoretical construct of “institutional disconnection”:

Memo: Connecting Experiential Categories (12/01/2025). The focused categories of ‘resource allocation asymmetry,’ ‘communication breakdown,’ and ‘parallel value systems’ share an underlying pattern. Participants are not merely describing practical barriers but fundamental differences in how cultural value is understood and operationalized. When [informant] describes institutions focusing on “a small circle of for-profit operators who are completely disconnected from actual creative communities,” they are articulating more than resource competition—they are identifying distinct cultural worlds operating according to different logics. This suggests a theoretical construct I’m labeling ‘institutional disconnection’ that goes beyond communication issues to encompass divergent meaning systems with minimal meaningful intersection.

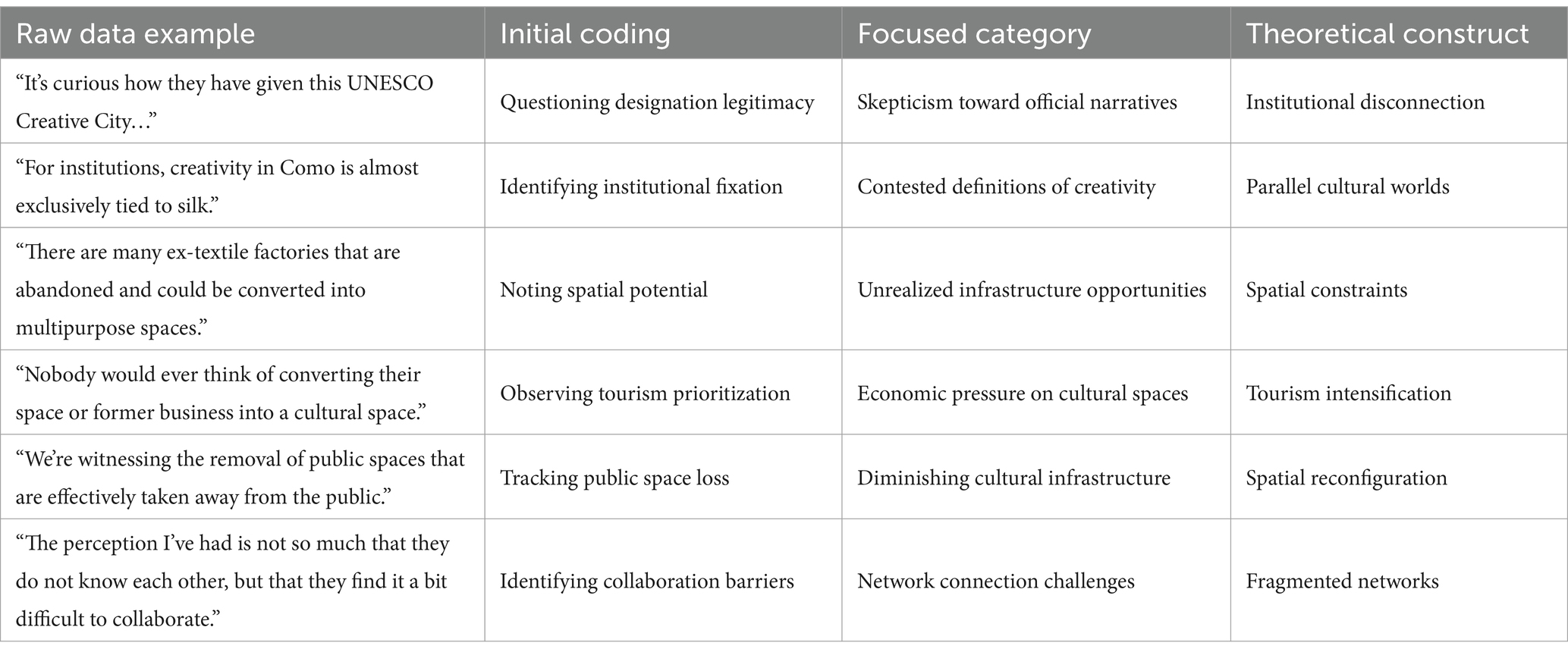

The table below provides additional examples of how raw data progressed through the coding process.

The analytical process involved progressive abstraction from empirical observations to theoretical constructs. For instance, multiple participants’ descriptions of spatial limitations coalesced into the focused category “infrastructure deficits,” which connected to the broader theoretical construct of “spatial constraints.” Similarly, various expressions of difficulty in forming collaborative relationships—initially coded with descriptors like “collaboration barriers” and “networking difficulties”—ultimately informed the theoretical construct of “network fragmentation.” These theoretical constructs emerged through iterative coding and memoing rather than being imposed upon the data from preexisting frameworks, consistent with grounded theory’s emphasis on theoretical emergence. Complementary ethnographic data were generated through systematic participant observation at cultural events, attendance at key institutional meetings including the 2025 Plenary Meeting, and immersion in spaces frequented by art world actors. Detailed field notes documented spatial arrangements, interaction patterns, and discursive frameworks observed during these engagements. Additional contextual insights were gained through informal discussions with stakeholders, local historians, municipal politicians, and administrative personnel, with analytical memos documenting emergent connections between empirical observations and theoretical concepts throughout the fieldwork period.

3.3 Methodological rigor and reflexivity

The research design integrated multiple strategies to ensure methodological rigor. Credibility was enhanced through prolonged field engagement, methodological triangulation, and respondent validation (Birt et al., 2016), where preliminary interpretations were shared with participants for refinement. The analytical process relied on manual coding. The coding involved multiple transcript readings, marginal annotations, color-coded themes, and physical arrangement of excerpts to visualize conceptual relationships, aligning with the creative, non-linear dimensions of qualitative analysis (Strauss, 1987).

A reflexive orientation informed the research throughout, acknowledging the situated nature of knowledge production and my positionality as a researcher. It is significant that while I conduct research on Como’s creative ecosystem, I do not reside in the city, which provided a degree of analytical distance from everyday immersion in local cultural politics. Simultaneously, my background as a practicing musician afforded me particular insights into the professional vocabularies, practical concerns, and tacit knowledge that shape cultural producers’ experiences (Becker, 1982). This dual positioning—academically trained in sociological analysis while experientially familiar with the practical realities of creative labor—created a productive tension in the research process, enabling me to recognize nuances in participants’ accounts that might be overlooked without this hybrid perspective (Raffa, 2024c). Indeed, this experiential background facilitated rapport-building with participants, as I could engage with their accounts through shared reference points regarding creative practice. However, this shared positioning also required vigilance against presuming equivalence between my artistic experiences and those of participants operating in Como’s specific context. I maintained awareness of how my own artistic background might shape my interpretive frameworks, particularly regarding potential tendencies to over-identify with certain participant perspectives or to privilege particular forms of cultural practice based on my own life history.

This form of ‘epistemic reflexivity’ required regular memoing to interrogate how my theoretical dispositions, professional background, and social position shaped data interpretation. Following Finlay’s (2002) approach to reflexivity as intersubjective exploration, I regularly examined how research relationships themselves constituted sites of knowledge production rather than neutral channels of information transmission. This practice embodies a kind of ‘reflexivity of discomfort,’ engaging substantively with the epistemological implications of the researcher’s standpoint rather than treating reflexivity as merely procedural (Pillow, 2003).

A methodological challenge meriting reflection is the limited representation of silk craftspeople in this study despite Como’s UNESCO designation in Crafts and Folk Art. This pattern constitutes a theoretically significant finding about classification struggles within cultural fields rather than merely a sampling limitation. The difficulty in accessing silk artisans reveals a fundamental disjuncture between institutional taxonomies of creativity and the lived organization of Como’s cultural ecosystem. This gap exemplifies how official categorizations of cultural value operate as symbolic interventions that may diverge substantially from the practical taxonomies through which cultural producers understand their work and position themselves within creative hierarchies. The UNESCO framework represents an institutional consecration that assigns particular symbolic capital to craft traditions, yet this official valuation appears misaligned with how the perception of prestige actually circulates within Como’s cultural networks. The classification of silk production as “creative” under the UNESCO designation operates in tension with field-specific understandings of cultural legitimacy, where creativity is often conceptualized through frameworks privileging artistic autonomy rather than industrial heritage. This misalignment manifests in the field’s structural organization, where those officially centered in creative city narratives occupy more ambiguous positions in contemporary cultural hierarchies. These methodological reflections suggest that the limited representation of silk craftspeople reveals important insights about how creativity is differently conceptualized within institutional discourses and everyday cultural practice.

The study adhered to established ethical principles for ethnographic inquiry, with formal ethical approval secured before data collection (Murphy and Dingwall, 2001). Participants provided informed consent in verbal form after receiving a detailed explanation of the research purpose, data handling procedures, and potential outputs. All interviews were conducted anonymously.

It is to be acknowledged that this study serves as an exploratory component of a broader project mapping the art worlds of Como. Its objective is to identify preliminary patterns and generate conceptual insights that inform subsequent research phases.

4 Findings

The ethnographic inquiry identified three key thematic areas that characterize the relationship between Como’s institutional framing as a UNESCO Creative City and the everyday practices of local cultural producers. These themes emerged through detailed coding of interview transcripts, field notes, and documentary materials. Consistent with grounded theory methodology, the analysis prioritized conceptual categories that emerged through participants’ own meaning-making processes rather than imposing predetermined theoretical frameworks. Through comparative analysis of participants’ accounts, recurring interpretive patterns became evident in how cultural operators constructed understandings of their position within Como’s creative ecology, experienced material conditions of production, and formed professional networks. These patterns constituted conceptual categories; theoretical constructs grounded in empirical data that explicate social processes across diverse lived experiences.

This analysis approaches the UNESCO Creative City designation as an institutional framework that enters into an already-constituted local cultural ecosystem, becoming one element within the complex symbolic and material environment that cultural producers must interpret and negotiate. In our view, institutional classifications of cultural forms never simply describe pre-existing realities but participate in constituting the objects they purport to categorize. The findings therefore attend to how cultural producers actively engage with, reinterpret, and sometimes contest the categories and valuations embedded in creative city discourse. The following sections present these thematic areas through analytical discussion grounded in participants’ accounts. While presented discretely for clarity, these themes represent interrelated dimensions of social reality in which institutional discourses and everyday practices continuously shape one another through processes of interpretation and appropriation. The analysis attends to the diverse symbolic resources through which cultural producers make sense of their experiences and construct professional identities within broader structures of cultural production.

4.1 Institutional disconnection and parallel cultural worlds

Data analysis revealed a profound experiential disjuncture between institutional frameworks and the daily realities of cultural production in Como. Cultural operators consistently articulated this disconnection not as a mere communication gap but as fundamentally different meaning systems operating in parallel with minimal meaningful intersection. This disconnection manifests most acutely in participants’ descriptions of their relationships with municipal authorities. Cultural operators across diverse sectors—including independent cinema, music events, theater, and visual arts—expressed a pervasive sense of institutional detachment. This was characterized not simply as an absence of supportive structures but as a structural misalignment between institutional priorities and the lived realities of cultural practice. Significantly, this detachment appeared to transcend individual personalities or specific administrative periods, suggesting deeper structural patterns in how cultural value is understood and operationalized at institutional levels.

A central dimension of this institutional disconnection emerged through conflicting interpretations of the UNESCO Creative City designation’s purpose and material implications. Throughout the ethnographic research, cultural practitioners consistently expressed expectations that the designation would generate tangible resources for Como’s broader creative ecosystem. These expectations revealed underlying assumptions about institutional recognition as necessarily linked to material support. A cultural operator offered a particularly incisive reflection:

Cultural resources go to an extremely limited number of entities. Most of these do not even create cultural proposals—they either present mainstream performances that also tour through Como because there are 100,000 residents, so it makes sense to produce that type of show at the Teatro Sociale, or there’s this strange thing in Como that I’ve noticed: the main perceived creative activity is silk production, which is firstly an industrial activity and secondly in decline. The factories have closed, silk is no longer mainly produced in Como, there are only small operators left who largely outsource their work, often to China. So it’s curious how they have given this UNESCO Creative City…

These practitioner expectations stood in stark contrast to institutional understandings of the designation’s function. During a public event attended as part of the ethnographic research, an institutional stakeholder from the Focal Point directly addressed this discrepancy, stating,

I want to clarify […] [that the UNESCO designation] does not automatically provide direct funding to artists, […] this is a misconception we have encountered frequently and […] perhaps should have addressed more proactively in our communications. […] What the designation truly represents for us is a significant honor that carries substantial responsibilities, […] a prestigious commitment that elevates Como’s cultural standing internationally. (public event statement).

This statement reveals a fundamental misalignment in how different actors interpret the meaning and purpose of international cultural designations. Where cultural practitioners understood the designation primarily in terms of potential resource flows, institutional actors framed it as a responsibility and obligation—a structuring of duties rather than an expansion of possibilities. This misalignment extends beyond simple miscommunication to reveal deeper contradictions in how cultural value is understood and operationalized. Cultural practitioners consistently described expectations of material support because their daily experiences involve balancing precarious economic conditions where resources directly determine creative possibilities. In contrast, institutional frameworks often prioritize symbolic capital—international recognition, prestige, and city branding—over material interventions in cultural infrastructure. These different orientations toward cultural value reflect not merely different priorities but fundamentally distinct modes of evaluating cultural significance.

Moreover, several participants described how Como’s silk heritage, rather than functioning as an enabling tradition for contemporary creativity, potentially constrains cultural innovation by reinforcing particular dispositional orientations toward cultural production. As an event organizer reflected,

For institutions, creativity in Como is almost exclusively tied to silk. But this creates a small business, petty bourgeois mentality where culture is expected to generate immediate profit. The artistic community works in completely different timeframes and with different values. Third sector organizations are doing the real cultural work while institutions focus on a small circle of for-profit operators who are completely disconnected from actual creative communities.

Moreover, as a textile artisan observed,

The real core of creativity in Como used to be the design studios, and now there’s basically none left. There used to be a real continuity between industry and the creative sector. But when Como decided back in the 1970s that it did not want to be an industrial city anymore, it also kind of gave up on being a creative one. All that stuff you read nowadays is nothing but propaganda to help businesses seeking to capitalize on the label.

These observations show how different conceptions of temporality underpin institutional versus practitioner understandings of cultural value. Where institutional frameworks often privilege measurable short-term outcomes aligned with economic rationales, cultural practitioners frequently operate according to different temporal horizons and value systems. This misalignment creates fundamental barriers to meaningful engagement between institutional structures and cultural practices, as each operates according to incompatible evaluative criteria. This reflects a broader sense of disconnection experienced by artistic practitioners vis-à-vis local institutions, which are widely perceived as complicit in a decades-long process of urban tertiarization. According to many cultural actors, this shift has contributed to the gradual depersonalization of the city—a loss of its situated identity—now rendered particularly visible in the patterns of transient, extractive tourism that dominate the historic center and lakefront. The lived experience of cultural producers suggests that what is at stake is not merely an economic reorientation, but a deeper transformation in the affective and symbolic texture of urban space.

The ethnographic data revealed that the discussed dynamics extend beyond resource allocation to shape processes of cultural visibility and legitimation. Informants often seem to that such institutional disconnection operates through active processes of selective recognition that render certain cultural forms hyper-visible in official representations while others remain institutionally illegible despite their significance within local cultural ecosystems. These processes of visibility and invisibility construct particular versions of ‘creativity’ that may bear little relationship to how cultural producers themselves understand their practices. Significantly, data identified how these patterns of disconnection produce specific forms of subjectivity among cultural producers. Many participants described developing a sort of ‘strategic disengagement’—a set of practical orientations and emotional dispositions characterized by deliberate distance from institutional frameworks. Rather than seeking institutional recognition or support, these cultural producers focus on developing self-sustaining operational models and alternative legitimation frameworks. This strategic disengagement represents not simply a reaction to institutional limitations but an active construction of professional identity that positions institutional detachment as a marker of authenticity and independence.

These patterns of institutional disconnection reveal how the UNESCO Creative City designation enters a complex field of preexisting relationships, expectations, and disappointments rather than a neutral social space. The ethnographic data suggests that without addressing these underlying dynamics of disconnection, global cultural policy frameworks may inadvertently reinforce rather than transform existing patterns of cultural marginalization and institutional distrust. The parallel worlds of institutional representation and lived cultural practice continue to operate according to different logics, with the creative city designation potentially widening rather than bridging this experiential gap (Table 1).

4.2 Spatial constraints and tourism intensification

The second major theme emerging from the ethnographic data reveals a profound tension between Creative City designation and the material transformation of urban space through tourism intensification. Participants consistently identified how tourism reshapes the urban fabric in ways that fundamentally contradict the cultural development possibilities implied by the Creative City framework. A dominant was participants’ articulation of the irony inherent in promoting Como as a lively creative hub while simultaneously witnessing the erosion of spaces where creative practices can actually develop. A music event organizer reflected on this contradiction:

When you talk about creative cities, about Como’s excellence, about directing boards… these are all big words that administrators and some people in Como throw around… You need to create a path, you need to nurture it. It really requires a process of networking, of sharing objectives, which has never happened. And especially where young people have always been cut out of this.

This observation highlights how the Creative City designation is perceived as disconnected from the material conditions necessary for sustaining creative ecosystems. The participant’s emphasis on process and nurturing suggests an understanding of creativity as requiring specific spatial and temporal conditions that conflict with the perceived urban development patterns. Data showed how tourism development directly impacts the spaces potentially available for cultural production, particularly those connected to Como’s craft heritage that forms the basis of its UNESCO designation. A designer and cultural operator observed:

There are many ex-textile factories that are abandoned and could be converted into multipurpose spaces. This is a big issue… do I make B&Bs or do I try to make as much revenue as possible with the properties I own in Como? So, nobody would ever think of converting their space or former business into a cultural space or a space that could be dedicated to arts and culture.

Cultural operators articulated experiencing a contradiction between Como’s Creative City designation and their lived reality: while the city officially celebrates silk traditions, they found that tourism-driven property markets made it nearly impossible to repurpose historic industrial spaces for creative work. Their accounts revealed how gentrification and real estate speculation created what they experienced as insurmountable barriers to developing cultural infrastructure that might connect historical craft knowledge with contemporary creative communities. Many participants’ narratives centered around contested understandings of ‘tourism quality’ in Como. Their accounts revealed how they conceptualized quality primarily through meaningful cultural engagement and authentic connections to local creative practices, which they perceived as fundamentally different from institutional approaches focused on visitor numbers and spending. This tension appeared particularly in how they described the Silk Museum—a space they experienced as symbolizing unfulfilled cultural potential and a missed opportunity to develop tourism beyond superficial consumption patterns. For these cultural producers, the progressive outsourcing of silk production represented something more profound than economic restructuring—they experienced it as cultural loss that undermined what made Como distinctive as a creative center. Through their accounts emerged a sense of disconnect between celebrated heritage and the material conditions they experience in their daily creative practices. Several participants described witnessing the closure of venues that previously supported community-based cultural practices. A cultural organizer reflected:

We’re witnessing the removal of public spaces that are effectively taken away from the public, from citizens… from the bowl club they closed and took away from those poor elderly men to the Chiostrino Artificio. There was a space managed by an association called Artificio, and the people from Luminanda and Couture Migrant were involved. I experienced it with great surprise because there was a space in the center given to an association that had done so many things, because it was on three floors and each floor had taken on this multipurpose role of various kinds.

This observation highlights how the Creative City designation operates alongside contradictory processes of spatial reorganization that actually reduce rather than expand creative possibilities. The participant’s surprise at discovering a multipurpose cultural space in the city center suggests how unusual such arrangements have become, indicating a broader pattern of spatial transformation that privileges commercial uses over cultural infrastructure. Significantly, data analysis identified a widespread perception that the Creative City designation primarily serves tourism marketing rather than addressing the actual needs of cultural producers. As a visual artist and cultural operators stated,

There aren’t even venues to hold events in. The Officina della Musica has closed. The only concert hall is remote and poorly connected to the city and has a very small capacity.

This account reveals how cultural operators experience a fundamental disconnect between the city’s international designation as a center of creativity and the actual infrastructure available to support creative practice. The tension between preserving cultural identity and attracting economically significant tourist flows also emerged as a central issue in participant narratives. Such tension is particularly evident in the historic center, where the proliferation of mass tourism-oriented activities is perceived by many as a threat to the integrity of the city’s urban and social fabric. A citizen active in community associations articulated this multidimensional crisis:

Como is a wealthy city but one that no longer expresses its capacity for investment, either from an industrial or a cultural point of view… industrial activity no longer exists, there’s no capacity to innovate through culture, patrons are missing.

This statement effectively synthesizes the perception of a multidimensional crisis affecting not only the tourism sector but more generally Como’s urban development model. The debate on tourism quality in Como is thus linked to broader questions of urban identity, economic development, and social cohesion. The ethnographic data revealed particularly significant tensions between the type of tourism that Como attracts and the development of authentic cultural experiences. Many participants expressed concerns that current tourism patterns generate economic pressures that privilege standardized consumption over distinctive cultural production. A design professional described this dynamic:

One thing that has always made me furious is that the tourist tax is not reinvested in cultural events. You cannot use it to fix potholes in the roads or things like that, you are supposed to put 70% of it into organizing events and activities that make Como lively. But the Como administration and especially the Como bourgeoisie do not want it lively because a lively city is a noisy city. It’s like they are thinking, “I spent 800,000€ for an apartment in Como, I do not want music playing underneath it, I do not want young people around who might get drunk and disturb me.”

This observation connects spatial limitations directly to how tourism revenue is allocated, suggesting how economic resources generated by tourism could potentially support cultural infrastructure but are directed elsewhere. The patterns of spatial transformation reveal significant contradictions in how the UNESCO Creative City designation operates within Como’s urban development. While officially celebrating creativity, particularly craft traditions, the designation coexists with urban processes that increasingly constrain rather than expand spaces for creative practice. Several cultural operators highlighted what they perceived as a fundamental disconnect between existing cultural resources and tourism development strategies. Cultural operators frequently contrasted Como’s untapped cultural assets with its dominant tourism model. An informant referenced Cinema Astra—the sole remaining movie theater in the historic center with approximately one thousand arthouse film club subscribers—as evidence of existing demand for sophisticated cultural offerings. This participant interpreted this substantial audience base as demonstrating the presence of a critical mass that could potentially support more substantive cultural tourism initiatives. Yet, participants generally perceive a strategic misalignment wherein institutional investment prioritizes ephemeral tourism experiences—exemplified by “day-trippers who merely take boat tours before returning to Milan” (cultural operator, personal interview)—over developing the cultural infrastructure that might position Como as a destination for cultural events with longer visitor engagement cycles.

4.3 Fragmented networks and emerging forms of solidarity

The third thematic area emerging from the data concerns the social organization of Como’s cultural field—specifically the patterns of connection, fragmentation, and nascent collective action among cultural producers. The research revealed a cultural ecosystem characterized by significant fragmentation with simultaneously emerging forms of solidarity developing in response to shared structural constraints. Cultural operators consistently articulated experiencing substantial barriers to forming cohesive networks within Como’s creative ecology. A young designer involved in event organization explained:

The perception I’ve had is not so much that they do not know each other, but that they find it a bit difficult to collaborate. It’s difficult to have that point of contact where forces unite and you try to move towards a common direction.

This reflection shows how cultural producers experience Como’s creative ecosystem not as entirely disconnected but as characterized by limited substantive collaboration despite mutual awareness. The distinction between mere recognition and meaningful cooperation suggests that barriers to collective action exist not in complete isolation but in difficulties translating awareness into collaborative practice. Significantly, institutional stakeholders corroborated these perceptions from their vantage point. Several institutional representatives observed that associations frequently struggle to coordinate effectively among themselves. This institutional perspective on fragmentation suggests that the pattern is recognized across different positions in the field, though with varying interpretations of its causes and implications. Where cultural operators often located fragmentation in structural conditions, institutional actors more frequently attributed it to organizational cultures or leadership differences.

The contestation of public space emerged as a crucial dimension of fragmentation and solidarity development. Through comparative analysis across informants’ accounts, a pattern emerged of systematic reduction in accessible public spaces where diverse cultural actors could interact. Several participants described the closure of specific venues and community spaces as not merely individual losses but as representing a broader reconfiguration of Como’s public space that significantly impacts possibilities for cultural connection. Many participants connected these patterns of fragmentation to broader socio-cultural characteristics of the local context. Several described experiencing Como’s distinctive social atmosphere as fundamentally affecting how cultural networks form. A cultural operator who had relocated to Como from another region reflected:

Here in Como you immediately get the feeling that no one was waiting for you, no one welcomes you, and in fact, all things considered, you could have stayed where you were. I believe it’s a way of being that’s rooted in this place.

This account reveals how cultural producers interpret Como’s social climate as creating particular conditions for network formation and collaborative possibilities. The participant’s attribution of these patterns to qualities “rooted in this place” suggests their understanding of local social behaviors as culturally embedded rather than merely circumstantial, constituting an interpretive schema through which they make sense of their experiences of disconnection. Data analysis showed how cultural producers develop strategic responses to these conditions through alternative forms of spatial practice. Several participants described creating temporary, improvised cultural spaces when permanent venues proved inaccessible. For instance, a participant involved in organizing alternative cultural events said they have been “looking for a space for a year and a half, we are here knocking on warehouses of priests, friends, friends of friends” (personal interview). This statement underlines the improvised spatial strategies through which cultural producers attempt to overcome structural limitations. The reference to “warehouses of priests” suggests how cultural operators mobilize diverse networks and alternative spaces outside conventional institutional channels to sustain cultural practice. These practices represent important forms of agency amid constraint, revealing how cultural producers actively construct possibilities for practice rather than passively accepting limitation. A particularly significant pattern in the ethnographic data was the emergence of deliberate bridging initiatives designed to connect Como’s fragmented cultural ecosystem. From interviews, what emerges is a form of institutional entrepreneurship wherein cultural producers recognize fragmentation as a structural condition and develop organizational strategies specifically designed to address it. These bridging initiatives often develop through connections between locals and newcomers to the city. Several participants noted how cultural organizations that successfully balance Como’s fragmented networks frequently involve people from diverse geographical backgrounds. This aspect suggests that ‘outsider’ positioning, often considered a disadvantage in cultural fields, may paradoxically enable certain forms of connection that prove difficult for more embedded actors.

Some participants recounted earlier periods when alternative cultural spaces operated with greater autonomy while simultaneously attempting to engage municipal authorities. As documented by the local inquiry association FuoriFuoco (2024), Como’s cultural history includes notable examples of grassroots initiatives that created vibrant spaces for artistic expression and community gathering. These historical spaces—particularly music venues that served as social hubs in the 1980s and 1990s—are frequently referenced by current cultural operators as representing a different model of cultural engagement, characterized by greater cross-class participation and artistic experimentation. These historical narratives play an important role in how contemporary cultural producers interpret current institutional frameworks. Several participants drew explicit comparisons between past models of cultural self-organization and present institutional approaches, suggesting that earlier bottom-up initiatives created more authentic connections across social boundaries despite operating with minimal official support. These recollections serve as interpretive resources through which current cultural operators make sense of their relationship with formal structures, often framing contemporary challenges as continuations of longstanding tensions between grassroots cultural production and institutional recognition. The persistence of these historical reference points suggests how cultural memory shapes current perceptions of institutional relationships, with past experiences of autonomy and marginalization influencing how today’s cultural producers engage with frameworks like the UNESCO Creative City designation.

The ethnographic research additionally revealed how participants described shared frustrations with institutional frameworks as sometimes catalyzing new forms of solidarity. Several cultural operators recounted developing collective projects specifically in response to what they perceived as institutional gaps. They characterized these initiatives as alternative organizational forms that emerge when they experience institutional frameworks as not addressing community needs—creating what might be conceptualized as parallel infrastructures that they described as operating according to different logics than what they perceived as dominant institutional arrangements. These patterns of how participants described fragmentation and emerging solidarity illustrate the complex social landscape into which the UNESCO Creative City designation enters—characterized by what cultural operators experienced as limited collaboration alongside what they interpreted as nascent attempts at field-building. Moreover, data showed how cultural producers made sense of the creative city framework primarily through their lived experiences of existing social networks and collaborative possibilities. Their accounts suggest their understanding that creative city designations primarily recognize and celebrate creativity as an abstract quality while they perceived a need for addressing the social infrastructure they considered necessary for sustainable creative ecosystems. Participants’ narratives revealed how they conceptualized the development of cultural fields as requiring not only formal recognition but what they described as substantive engagement with the material and symbolic conditions that shaped their collaborative cultural practices in Como.

5 Discussion

This ethnographic study examines the multifaceted connections between institutional frameworks and cultural practitioners’ lived realities in Como. The findings highlight significant fissures between official narratives and everyday creative labor experiences, as the UNESCO designation introduces symbolic capital that reconfigures legitimation hierarchies without necessarily transforming material conditions. How stakeholders interpret this recognition varies considerably based on their structural positions and resource access. The three thematic domains—institutional disconnection, spatial constraints, and network fragmentation—are deeply interwoven, constituting different dimensions of a cultural field marked by structural tensions and symbolic struggles. In my view, these tensions may reflect the differentiated distributions of capital that shape the positions and practices of cultural agents within Como’s urban environment.

Institutional disconnection emerges from a structural misalignment between cultural producers’ habitus—often oriented toward autonomy and long-term practice—and institutional logics that privilege business results, prestige and visibility. This misalignment generates not merely detachment but a rupture in meaning-making, where cultural producers and institutional stakeholders operate according to incompatible evaluative frameworks. These symbolic disconnections directly inform spatial exclusion dynamics. Across Como’s fractured cultural terrain, a convergence of perception emerges despite otherwise divergent evaluative frameworks: both institutional stakeholders and cultural producers articulate profound disquiet regarding tourism intensification, albeit through distinct interpretive schemas reflecting their structural positions. The resulting spatial regime engenders a double dispossession—simultaneously symbolic and material—wherein cultural forms lacking immediate touristic legibility become progressively illegible within institutional frameworks while simultaneously being deprived of the spatial conditions necessary for their reproduction. This dispossessive process manifests concretely in the atomization of Como’s cultural networks, as actors find themselves operating in spatial isolation despite cognitive awareness of parallel practices. Yet this fragmentation, while constraining collective capacity, simultaneously generates conditions for the emergence of alternative socialities characterized by improvisational spatial practices, ephemeral solidarities, and tactical reappropriations of interstitial urban spaces (De Certeau, 1984). These emergent forms of collective practice represent generative reconfigurations of the relationship between cultural production, urban space, and collective organization, articulating through practice alternative visions of urban cultural possibility that exist in tension with tourism-driven spatial logics.

Together, these domains form a dynamic system in which institutional disconnection, spatial pressures, and network fragmentation mutually reinforce one another while also generating new forms of agency. The UNESCO Creative City designation thus becomes embedded within local fields of power and practice—reshaping, but also being reshaped by, the complex sociocultural ecology it enters. Ethnographic data revealed how legitimacy within Como’s creative ecosystem is perceived to be unevenly distributed. Indeed, implicit classification systems privilege certain forms of cultural production over others, reinforcing existing hierarchies of artistic legitimacy. Participants consistently distinguish between ‘authentic’ cultural activities—such as music, independent cinema, and contemporary visual arts—and commercially driven practices like silk production, often conceptualized predominantly as an industrial enterprise rather than a creative pursuit, despite respondents’ acknowledgment that creative intentionality invariably undergirds silk production processes. A music event organizer’s description of silk as “firstly an industrial activity” illustrates how cultural actors construct taxonomies of value that operate independently of institutional classifications. Such classification struggles highlight the ways in which sectoral boundaries are constructed in practice. The distinction between ‘cultural industries’ and ‘creative industries’ follows a conceptual trajectory found in existing taxonomies (Hesmondhalgh, 2002; Throsby, 2008). The former primarily includes industries that produce and disseminate cultural texts, such as publishing, film, and music, emphasizing the role of mass reproduction and meaning-making. The latter, by contrast, incorporates a broader set of activities, including design, advertising, and fashion, which rely on creative inputs but do not necessarily center on cultural content creation (KEA European Affairs, 2006). Participants’ implicit classifications resonate with these distinctions, as they tend to perceive activities tied to artistic expression as more aligned with ‘culture,’ while those embedded in industrial production are viewed as distinct. This distinction is further complicated by more extensive interpretations, such as Santagata’s (2009) model, which broadens the notion of creative industries to include activities traditionally considered industrial. In this approach, creative inputs can function as added value even in sectors where the cultural dimension is secondary to economic or manufacturing processes. Some participants appear to resist this more expansive classification, implicitly aligning with definitions that prioritize cultural expression over commercial application. Their perspectives reflect an ongoing tension in cultural policy discourse: whether to maintain a narrower, meaning-centered definition of cultural industries or to embrace a more integrative framework that accounts for their intersection with economic production.

The emerging relationship between structural urban transformations and the spatial practices of cultural producers can be theorized through examining how cultural actors perceive and engage with Como’s tourism-oriented spatial reconfiguration. Participants view tourism-driven development not merely as an economic strategy but as a fundamental reorganization of urban space that they believe privileges consumption-oriented spatial arrangements over production-oriented infrastructures. Their accounts reveal perceptions of how tourism intensification systematically revalues urban space through market mechanisms that they experience as rendering cultural infrastructure increasingly precarious. One designer’s observation that “nobody would ever think of converting their space or former business into a cultural space” reflects a perception that exchange value imperatives displace potential cultural uses. Similarly, the critique that “the tourist tax is not reinvested in cultural events” expresses how participants perceive tourism-generated capital flows as reinforcing rather than mitigating the spatial marginalization of cultural production.

These interpretations resonate with Urry’s (1990, 2007) analysis of the ‘tourist gaze,’ where cities are increasingly curated as visual spectacles for transient visitors rather than as lived environments for creative communities. Participants expressed frustration with what they perceived as the aestheticization of Como’s cultural identity, believing that institutional investments favor heritage preservation and mass tourism over contemporary artistic practices. These perceived spatial constraints align with broader critiques of neoliberal urban governance (Harvey, 1989; Peck, 2005) and Sassen (1991) concept of ‘new geographies of centrality and marginality.’ As one cultural association member asserted, Como “no longer expresses its capacity for investment, either from an industrial or a cultural point of view.” Cultural producers respond to these perceived structural conditions through spatial practices that simultaneously acknowledge constraint while asserting alternative valuations of urban space. In their accounts, the intersection of housing market transformations and cultural infrastructure emerged as particularly significant, with participants consistently connecting what they see as tourism-driven property speculation with diminishing opportunities for cultural production. This positioning of cultural production under tourism intensification reveals a perceived contested field where cultural producers view themselves neither as passive subjects of structural determination nor as autonomous agents, but as reflexive actors whose practices simultaneously reproduce and challenge dominant spatial arrangements. Their spatial adaptations represent claims to urban space based on cultural use value that they position in tension with exchange value imperatives, constituting a form of everyday spatial politics operating beneath the level of formal contestation while nonetheless articulating alternative urban possibilities.

These findings resonate with recent research on how cultural policies adapt to changing societal circumstances. As discussed by Comunian and England (2020), cultural and creative workers seem to interpret increasingly precarious conditions by developing adaptive strategies that often operate parallel to formal institutional structures. Their analysis of creative sector precarity during the COVID-19 pandemic reveals patterns of adaptive resilience similar to those observed in Como, where cultural producers develop alternative frameworks and practices in response to institutional constraints. The improvisational spatial practices and emerging solidarity networks identified in this study reflect comparable strategies of creative resilience amid structural limitations.