- 1Communication Sciences, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Indonesian Christian University in Molluccas, Ambon, Indonesia

- 2Communication Sciences, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia

This study examines the transformation of Marinyo, a traditional communication institution in Ambonese society, within the context of digital media expansion and the transition from Industry 4.0 to Society 5.0. The research addresses the critical challenge of maintaining cultural communication systems while embracing technological advancement, a concern highlighted by UNESCO’s directives on cultural preservation. Using ethnographic communication methods and in-depth interviews conducted across multiple indigenous communities representing both Christian and Muslim populations in Ambon, Indonesia, this research analyzes how Marinyo adapts as a traditional opinion leader in contemporary information ecosystems. The study aims to understand the hybridization processes, legitimacy transformation, and cultural sustainability of traditional communication institutions in the digital age. Findings reveal that rather than being replaced by digital technologies, Marinyo undergoes a complex hybridization process, evolving into unique communication formations that blend traditional authority with digital competencies. The study identifies two distinct hybridization patterns: a Divergent Hybridization Model, characterized by functional bifurcation between administrative-digital and ceremonial-traditional channels, and a Convergent Hybridization Model, marked by organic integration of traditional and digital elements. Results demonstrate how the cultural legitimacy of Marinyo remains a decisive factor in maintaining influence amid digital media penetration, while legitimacy sources expand to include technical competence and formal institutional recognition. This research contributes to understanding traditional communication systems’ resilience and cultural sustainability in the digital age, offering theoretical and practical implications for developing culturally responsive communication policies that bridge digital divides while preserving cultural identity. The novelty of this research lies in its comprehensive analysis of communication hybridization in indigenous contexts, extending beyond Western-centric media theories to provide insights into how traditional institutions strategically negotiate global technological forces while maintaining cultural authenticity.

1 Introduction

In the contemporary transition from Industry 4.0 to Society 5.0, indigenous communication systems face unprecedented challenges to their continuity and relevance. The rapid advancement of digital communication technologies, including social media platforms, instant messaging applications, and artificial intelligence-driven communication tools, has fundamentally transformed how information flows within communities worldwide. Yet, despite these technological advances, the question remains: why do traditional communication institutions like Marinyo persist in an era where digital efficiency seemingly renders human messengers obsolete? This tension between cultural preservation and technological adaptation creates complex dynamics of transformation, particularly for traditional opinion leaders whose authority has historically been rooted in cultural legitimacy rather than technical expertise.

This study examines the evolution of Marinyo, a traditional communication institution in Ambonese society in eastern Indonesia, as it adapts to and integrates with contemporary digital ecosystems. The research addresses a critical gap in understanding how traditional communication systems navigate the global push toward digital transformation while maintaining their cultural essence. This challenge resonates with UNESCO’s 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, which emphasizes preserving traditional practices in rapidly changing societies.

Marinyo, derived from the Portuguese “marinheiro” (sailor), reflects the colonial influence of the Maluku archipelago, where Portuguese traders and colonizers established maritime communication networks (Leirissa, 1975). However, adapting “marinheiro” to “marinyo” in the Ambonese context represents more than linguistic borrowing; it signifies the local appropriation and cultural transformation of external influences. Unlike the maritime connotations of its Portuguese origin, Marinyo in Ambonese society specifically refers to designated community messengers who function as official heralds within traditional governance structures. This semantic evolution exemplifies how Ambonese communities have historically negotiated external influences while maintaining cultural autonomy.

The cultural shift regarding Marinyo in Maluku has been particularly pronounced over the past two decades. Research indicates that while 78% of traditional communities in Maluku maintained active Marinyo systems in 2000, this figure declined to 43% by 2020, with many communities struggling to balance traditional practices with modern communication demands (Tutupoho et al., 2021). This decline reflects broader global trends where conventional communication systems face marginalization in increasingly digital societies.

However, preliminary observations suggest that rather than disappearing entirely, Marinyo undergoes strategic adaptations that reflect what García Canclini (2005) is described as “sociocultural processes in which discrete structures or practices, which existed separately, combine to generate new structures, objects, and practices.” This hybridization process enables traditional institutions to remain relevant while embracing technological capabilities, challenging linear narratives of technological replacement.

The historical development of Marinyo dates to the 16th century when Portuguese colonial administration established formal communication networks throughout the Maluku archipelago. Initially, these messengers served primarily administrative functions, relaying colonial directives between Portuguese officials and local chiefs. However, as local communities appropriated this system, Marinyo evolved into a distinctly Ambonese institution that integrated traditional governance structures with external communication practices. During the Dutch colonial period (1602–1942), Marinyo adapted again, serving as intermediaries between Dutch administrators and indigenous communities while maintaining their role in traditional ceremonies and customary law enforcement.

The post-independence period (1945-present) marked another significant transformation, as Marinyo became integral to Indonesia’s village governance system while preserving their traditional functions. This historical trajectory demonstrates Marinyo’s remarkable adaptability across different political and technological contexts, suggesting an institutional resilience that enables strategic negotiation with external forces while maintaining cultural continuity.

Understanding Marinyo’s transformation is crucial for several reasons. First, it provides insights into how traditional communication systems can maintain relevance in digital contexts without losing their cultural essence. Second, it offers practical guidance for policymakers seeking to develop culturally responsive communication strategies that bridge digital divides. Third, it contributes to theoretical discussions about media hybridization beyond Western contexts, enriching our understanding of how indigenous communities actively shape technological adoption processes.

The significance of this research extends beyond the Ambonese context to broader discussions about cultural sustainability in the digital age. As digital technologies penetrate even the most remote communities worldwide, understanding how traditional institutions adapt and persist becomes crucial for maintaining cultural diversity and preventing the homogenization of communication practices.

This study is guided by three interconnected research questions that frame our investigation of Marinyo’s evolving role in Ambonese society. We seek to understand how Marinyo adapts their traditional positions as opinion leaders within increasingly digital information ecosystems, examining the specific transformations in message dissemination processes that occur through communication hybridization, while also exploring the broader implications of these hybrid forms for the legitimacy and effectiveness of Marinyo as cultural intermediaries in contemporary society. Through these questions, we aim to capture both the practical adaptations of traditional communication roles and the deeper cultural negotiations that occur as indigenous communication systems interact with digital technologies, ultimately providing insights into how cultural sustainability can be maintained through strategic integration rather than wholesale replacement of traditional practices.

The primary objective of this research is to analyze the transformation of Marinyo as a traditional communication institution within the context of digital media expansion in Ambonese society. Specifically, the study aims to examine the adaptation strategies employed by Marinyo in integrating conventional and digital communication practices, identify the patterns of communication hybridization and their implications for message dissemination processes, evaluate the transformation of legitimacy bases for Marinyo as opinion leaders in hybrid media ecosystems, and assess the impact of communication hybridization for cultural sustainability and community cohesion in contemporary Ambonese society.

2 Literature review

2.1 Historical origins and evolution of Marinyo

The institution of Marinyo in Ambonese society represents a fascinating case of cultural adaptation and historical continuity spanning over four centuries. Understanding its origins and evolution provides crucial context for analyzing its contemporary transformation in the digital era.

The earliest documented references to messenger systems in the Maluku archipelago date back to the pre-colonial period, where indigenous communities employed various forms of long-distance communication, including tifa drums, smoke signals, and human messengers for inter-island communication (Leirissa et al., 1983). These traditional systems were primarily based on kinship networks and customary law, reflecting the decentralized nature of Maluku’s conventional governance structures.

The arrival of Portuguese traders and colonizers in the early 16th century marked a pivotal transformation in local communication systems. The Portuguese established formal administrative networks requiring systematic communication between colonial officials and local rulers. “Marinheiro” (sailor/seafarer) was adopted to describe individuals who carried messages between Portuguese naval commanders and coastal communities. However, as Pattikawa (2019) noted, the semantic transformation from “marinheiro” to “marinyo” involved more than linguistic adaptation; it represented the indigenous appropriation of colonial communication structures within traditional governance frameworks.

During the Portuguese period (1512–1,605), early Marinyo functioned primarily as cultural intermediaries who delivered messages and served as interpreters between Portuguese officials and local chiefs. Historical records from the Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino in Lisbon indicate that these messengers were carefully selected based on their linguistic abilities, cultural knowledge, and trustworthiness among Portuguese and indigenous communities (Leirissa, 1975). This dual loyalty requirement established the foundation for Marinyo’s later role as a cultural bridge in Ambonese society.

The Dutch colonial period (1605–1942) significantly changed the Marinyo institution. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) formalized the messenger system, incorporating Marinyo into their administrative hierarchy while recognizing their importance in maintaining local governance structures. During this period, Marinyo began wearing distinctive clothing to signify their official status: black long-sleeved shirts, black pants, and red headbands that symbolized their authority and neutral position in community conflicts. These visual markers, which persist in some communities today, represented the institutionalization of Marinyo as a formal communication role rather than an informal cultural practice.

The Japanese occupation (1942–1945) temporarily disrupted traditional governance systems, including Marinyo practices. However, rather than disappearing, many Marinyo adapted by serving as covert communication networks for resistance movements, demonstrating the institution’s flexibility and resilience during periods of political upheaval. This period highlighted Marinyo’s potential as an alternative communication channel when external forces compromised or controlled formal systems.

The post-independence period (1945-present) marked another significant evolution as Marinyo integrated into Indonesia’s village governance system while maintaining its traditional functions. The Indonesian government’s recognition of customary law (adat) provided a legal framework for preserving traditional institutions like Marinyo, even as modernization pressures increased. During this period, some communities began adapting Marinyo clothing to contemporary contexts, with some abandoning traditional attire for more practical modern clothing while maintaining the ceremonial use of conventional garments for important announcements and cultural events.

Regarding why traditional Marinyo clothing has evolved, the research reveals that climate considerations, practical mobility needs, and generational changes have influenced these adaptations. However, the symbolic significance of traditional attire remains essential for ceremonial functions and cultural identity maintenance. The history of customs presents no fundamental problems with clothing adaptation. Ambonese adat recognizes the principle of “adat yang hidup” (living customs) that allows for practical adaptations while preserving essential cultural meanings.

2.2 Traditional communication systems in theoretical perspective

Traditional communication systems represent complex sociocultural institutions that embody far more than mere information exchange mechanisms. As Melkote and Steeves (2015) argued, these systems function as repositories of cultural values, social structures, and power relations within communities, serving multiple functions that extend beyond the transmission of information to include social cohesion, cultural transmission, and the legitimation of authority structures.

The theoretical understanding of traditional communication has evolved significantly from early modernization theories that viewed traditional practices as obstacles to development toward more nuanced perspectives that recognize their adaptive capacity and cultural significance. Servaes and Malikhao (2012) identify several key characteristics that distinguish traditional communication systems from modern, technology-driven alternatives: participatory nature that involves community members as active participants rather than passive recipients, ritualistic dimensions that embed communication within cultural and spiritual frameworks, cultural legitimacy recognized and accepted by community members, and contextual appropriateness that reflects local values, languages, and social structures.

Research on traditional communication in Indonesia has revealed remarkable diversity in practices and forms across the archipelago’s numerous cultural groups. Purwasito (2015) comprehensive study of “kentongan” (conventional wooden slit drums) in Javanese communities demonstrates how these instruments served not only as communication tools but also as symbols of village identity and communal solidarity. Similarly, Kariasa et al. (2024) investigation of the “kulkul” communication system in Bali reveals how traditional bamboo instruments maintain their relevance in contemporary Balinese society through adaptation and integration with modern governance structures.

In Maluku, traditional communication systems reflect the region’s unique maritime geography and cultural diversity. Studies on “tahuri” (shell trumpet) and “tabaos” (public announcements) have documented distinctive Ambonese communication practices that form the broader ecosystem within which Marinyo operates (Leirissa et al., 1983). These systems typically combine auditory signals (drums, shells, or bells) with human messengers who provide detailed information and ensure message comprehension across linguistic and cultural boundaries.

The functional analysis of traditional communication systems reveals their multidimensional roles within community life. Tutupoho et al. (2021) identify five primary functions: informational (disseminating practical information about events, decisions, or emergencies), educational (transmitting cultural knowledge, values, and norms across generations), integrative (fostering social cohesion and collective identity), regulatory (enforcing social norms and community decisions), and ceremonial (maintaining ritual and spiritual dimensions of community life).

However, as Laksono et al. (2004) observed, traditional communication systems increasingly face challenges from modernization processes and technological change. These challenges include declining traditional knowledge as older practitioners pass away without adequately training successors, competition from modern communication technologies that offer greater speed and convenience, urbanization and migration that disrupt conventional community structures, and changing social values that may deemphasize traditional practices in favor of modern alternatives.

Additional research by Batlolona and Jamaludin (2024) on “Students’ misconceptions on the concept of sound: a case study about Marinyo, Tanimbar Islands” demonstrates how traditional communication knowledge, including understanding of acoustic principles used in Marinyo practices, is being lost among younger generations, highlighting the importance of systematic documentation and education programs for preserving traditional communication knowledge.

2.3 Marinyo as a traditional communication institution

Marinyo occupies a distinctive and complex position within Ambonese traditional governance structures, functioning simultaneously as a communication medium, cultural institution, and symbol of traditional authority. The institution’s multifaceted nature reflects the sophisticated understanding of communication that characterizes many indigenous societies, where information transmission cannot be separated from social relationships, cultural values, and power dynamics.

As Dentis (2024) comprehensively documented, Marinyo performs four primary functions within Ambonese communities. The informative function involves disseminating information from traditional leaders to community members, serving as the primary channel for announcing meetings, ceremonies, work obligations, and important decisions. The educative function encompasses transmitting cultural values, norms, and traditional knowledge. Marinyo often explains the cultural significance of announced events and reinforces community values through their delivery style and content. The persuasive function involves influencing community attitudes and behaviors according to leadership directives, leveraging Marinyo’s trusted position to encourage compliance with community decisions and participation in collective activities. Finally, the integrative function fosters social cohesion and collective identity by symbolizing community unity and shared cultural heritage.

Watloly (2012) anthropological analysis positions Marinyo as “pela komunikasi” (communication bond) that bridges various elements within Ambonese society. This concept of “pela” (bond or alliance) is central to Ambonese social organization, reflecting relationships of mutual support and reciprocity that extend beyond immediate family or clan connections. By serving as a communication medium, Marinyo transcends simple message delivery to become an active agent in maintaining social networks and community solidarity.

The legitimacy of Marinyo stems from dual sources that reflect both traditional and contemporary authority structures. Traditional legitimacy derives from formal recognition within customary governance systems, typically involving ceremonial appointment by the Raja (traditional leader) in consultation with the Saniri (customary council). This appointment process often includes ritual elements that symbolically transfer authority and responsibility to the new Marinyo. Contemporary legitimacy increasingly involves community trust and acceptance based on personal qualities such as communication skills, reliability, cultural knowledge, and moral character (Dentis, 2024).

The positional analysis of Marinyo within indigenous governance structures reveals their strategic importance as cultural intermediaries who navigate between different authority systems. In contemporary Ambon, many communities maintain parallel governance structures, including traditional (Raja and Saniri) and modern (village government and formal administrative systems) elements. Marinyo is a crucial link between these systems, translating decisions and information across cultural and institutional contexts.

Recent ethnographic research Muskita and Latuheru (2022) provides detailed insights into how modernization and mobile technology have begun challenging traditional Marinyo roles in contemporary Ambonese society. Their study reveals that while digital communication technologies have reduced some conventional functions of Marinyo, particularly for routine information dissemination, the institution continues to perform crucial roles in ceremonial contexts, emergencies, and communities where traditional governance structures remain strong. This suggests that rather than experiencing simple obsolescence, Marinyo is undergoing selective adaptation that preserves core functions while adapting to changing communication landscapes.

2.4 Opinion leadership and two-step flow communication

The theoretical framework of opinion leadership provides valuable insights for understanding Marinyo’s communicative role within Ambonese communities. The concept, pioneered by Katz and Lazarsfeld in their groundbreaking studies “The People’s Choice” (1944) and “Personal Influence” (1955), fundamentally challenged prevailing assumptions about mass communication effects by demonstrating that media influence typically flows through a two-step process: from media sources to opinion leaders, and then from opinion leaders to the broader public.

Katz and Lazarsfeld’s definition of opinion leaders as “individuals regarded by their social environment as credible sources of information and influence in particular domains” (Hepp, 2019) provides a valuable framework for analyzing Marinyo’s position within Ambonese communication networks. Opinion leaders typically possess several key characteristics that enhance their influence: greater access to external information sources, particular competence or expertise in relevant domains, strategic social positions within communication networks, and values congruent with community norms and expectations.

Weimann (1994) further development of opinion leadership theory emphasizes the dual role of opinion leaders as both “gatekeepers” and “interpreters” who not only relay information but also frame and contextualize it according to community values and needs. This interpretive function is particularly relevant for understanding Marinyo’s role in Ambonese communities, where they do not simply announce messages verbatim but actively contextualize them according to local understanding, cultural values, and community needs.

The interpretive dimension of Marinyo’s communication role is evident in their adaptation of messages for different audiences within the community. Ethnographic observations reveal that experienced Marinyo modify their language, tone, and examples based on their assessment of the audience’s cultural knowledge, age, and social position. This adaptive communication demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of their communities, enabling effective opinion leadership.

In the Indonesian context, research has Nugraha et al. (2012) found that traditional opinion leaders, including community elders, religious figures, and cultural leaders, play significant roles in shaping public opinion, particularly in areas with limited mass media exposure or strong traditional social bonds. This finding aligns with Coleman and Freelon (2016) the observation that despite the transformative effects of the internet and social media on communication dynamics, traditional opinion leaders maintain substantial influence in communities characterized by strong social cohesion and shared cultural values.

The relevance of opinion leadership theory to understanding Marinyo becomes particularly evident when examining their role in community decision-making processes. Rather than simply transmitting decisions by traditional leaders, Marinyo often serve as crucial feedback mechanisms, conveying community responses, concerns, and suggestions to the Raja and Saniri. This bidirectional communication flow expands the classic two-step flow model into a more circular pattern that positions Marinyo as a critical node in community information networks.

Looking toward future projections with advancing technology, the role of Marinyo faces challenges and opportunities. While artificial intelligence and automated communication systems may handle routine information dissemination, the cultural and interpretive functions of Marinyo remain irreplaceable. To ensure Marinyo’s continued relevance, communities must strategically position them as cultural interpreters and community bridges rather than simple information transmitters. This evolution requires investment in digital literacy training for Marinyo while preserving their artistic knowledge and authority.

2.5 Media hybridization and communication theory

The concept of media hybridization offers a sophisticated theoretical framework for understanding how traditional and digital communication systems interact, influence, and transform each other in contemporary society. While conventional media theories often assumed linear progression from older to newer forms, hybridization acknowledges the complex, multidirectional relationships that characterize contemporary media landscapes.

Chadwick (2017) the seminal work “The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power” provides the foundational theoretical framework for understanding media hybridization. According to Chadwick, “hybrid media systems are shaped by the interaction between older and newer media logics that drive political actors, organizations, and citizens to adapt their behaviors to take advantage of the shifting patterns of comparative advantage in various media technologies.” This definition emphasizes the strategic nature of media adoption, where actors actively choose among available options based on their assessment of effectiveness, reach, and appropriateness for specific communication goals.

Building on Chadwick’s work, García Canclini (2005) a broader conceptualization of hybridization as “sociocultural processes in which discrete structures or practices, which existed separately, combine to generate new structures, objects, and practices” provides crucial insights into the cultural dimensions of media transformation. García Canclini’s emphasis on hybridization as an active process of cultural negotiation rather than passive technological adoption is particularly relevant for understanding how indigenous communities in Ambon strategically adapt global technologies according to local needs and values.

As analyzed by the power dimensions of hybridization, these processes are never neutral but always embedded within relations of power and inequality. Kraidy argues that hybridization can be a strategy for marginalized groups to negotiate their positions within global power structures. It can also serve as an instrument for dominant forces to co-opt and neutralize local resistance. This perspective is crucial for understanding the cultural dimensions of communication hybridization in the Marinyo context, where local traditions interact with global digital technologies within broader contexts of cultural change and modernization pressure.

Recent scholarship has expanded hybridization theory to address the challenges indigenous communities face in digital contexts. Plenković and Mustić (2020) examine “media communication and cultural hybridization of digital society,” arguing that successful hybridization requires active community participation in shaping technological adoption processes. Their research demonstrates that communities that maintain agency in determining how technologies are integrated into local practices are more likely to preserve cultural continuity while gaining technological benefits.

Sani and Obi (2025) analysis of “African Traditional Communication System in the Age of Hybridity” provides valuable comparative insights for understanding indigenous communication hybridization. Their research reveals that successful hybridization typically involves “selective appropriation,” where communities strategically adopt certain technological features while rejecting others that conflict with cultural values or social structures.

The work Uche et al. (2020) on “Digital Media, Globalization and Impact on Indigenous Values and Communication” offers additional theoretical perspectives on how globalization processes interact with local communication systems. Their research suggests that rather than homogenization, digital globalization often creates new forms of cultural expression that combine global technologies with local content, values, and practices.

Studies of indigenous communities and digital technology have also contributed to hybridization theory through concepts like “indigenous media” (Ginsburg, 2008) and “appropriation” (Bruijn et al., 2009). Ginsburg’s concept of indigenous media explains how indigenous communities adapt and appropriate media technologies for cultural and political purposes. It challenges technological determinism by demonstrating how communities actively negotiate and recontextualize technologies according to their values and needs.

Research Bruijn et al. (2009) on mobile technology adoption in Africa identified the concept of “appropriation” to explain how local communities repurpose global technologies according to their local contexts. They argue that this appropriation process creates “alternative modernities” where global technologies are infused with local meanings and practices. This perspective is particularly relevant for understanding how Marinyo might adapt digital technologies not as replacements for traditional practices but as extensions that enhance traditional communication capabilities.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design

This study employed a qualitative approach with an ethnographic communication design to comprehensively examine the transformation of Marinyo’s role in digital information ecosystems. Ethnographic communication methodology, pioneered by Hymes (1962), enables researchers to understand communication patterns within specific cultural contexts, making it particularly suitable for investigating Marinyo as a culturally embedded communication institution.

Ethnographic methodology offers several advantages over other qualitative approaches for this research context. First, ethnographic methods allow for deep, contextual understanding of communication practices within their natural cultural settings, which is essential for understanding institutions like Marinyo that are deeply embedded in traditional social structures. Second, the extended fieldwork period enables researchers to observe communication practices across different contexts and periods, providing insights into routine and exceptional communication patterns. Third, ethnographic approaches facilitate the development of trusting relationships with community members, crucial for gaining access to traditional knowledge and practices that might not be readily shared with outsiders.

The ethnographic communication framework specifically focuses on the cultural dimensions of communication practices, examining what is communicated and how communication reflects and shapes cultural values, social relationships, and power structures. This approach aligns with the research’s focus on understanding how traditional communication institutions adapt to changing technological and social contexts while maintaining cultural continuity.

3.2 Population and sample

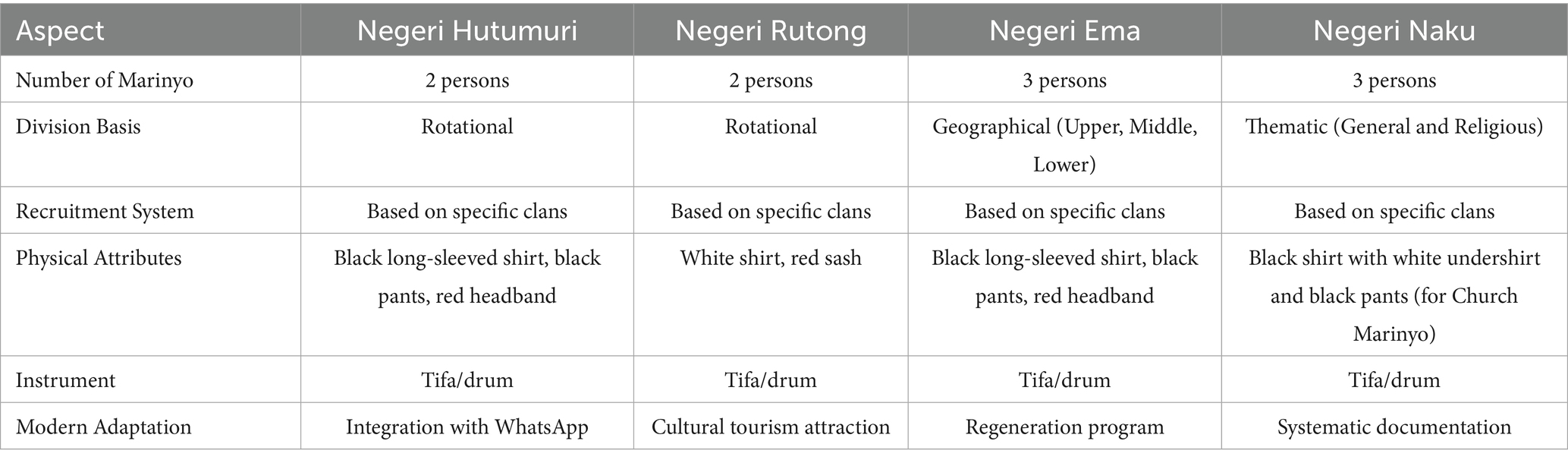

The research was conducted in four indigenous communities (negeri) on Ambon Island, Maluku Province, Indonesia: Negeri Hutumuri, Rutong, Ema, and Naku. These communities were selected through purposive sampling based on several criteria that would provide comprehensive insights into Marinyo practices across different contexts.

The selection criteria included: active maintenance of Marinyo practices as verified through preliminary research and community contacts, varying degrees of digital media penetration to enable comparative analysis of hybridization processes, representation of both Christian and Muslim populations to understand religious influences on communication practices, different geographical positions relative to urban centers to examine urbanization effects, and willingness of community leaders to participate in extended ethnographic research.

In ethnographic research, the question of representativeness differs from quantitative approaches. Rather than seeking statistical representation, the four communities were selected to provide what Stake (1995) is termed “maximum variation” - capturing the range of contexts within which Marinyo operates. This approach enables analytical generalization based on theoretical insights rather than statistical generalization to broader populations.

These four villages were specifically chosen as references compared to other villages in Ambon City due to their unique characteristics that make them ideal for studying communication hybridization. Hutumuri and Rutong represent communities that have maintained strong traditional governance structures while experiencing significant urban influence and digital integration. Ema and Naku provide examples of communities that have preserved traditional practices while adapting to modernization pressures in different ways. This selection provides a comprehensive range of adaptation strategies and outcomes that would not be available in a single community study.

The communities represent diverse contexts within Ambonese society. Hutumuri and Rutong, located closer to urban centers, have higher digital penetration rates (approximately 78.3% according to local telecommunications data) and stronger integration with modern governmental systems. These communities represent predominantly Christian populations with long histories of interaction with urban Ambon. Ema and Naku, positioned in more peripheral locations, have moderate digital access (approximately 51.6%) and maintain stronger traditional governance structures. Naku has a more religiously diverse population, including both Christian and Muslim residents, while Ema remains predominantly Christian but with traditional Islamic influences in certain customary practices.

Each community exhibited distinct governance structures and adaptations of Marinyo roles, providing rich comparative data. Hutumuri maintained strong traditional governance structures with active Marinyo roles but had begun formally integrating digital channels through established communication departments. Rutong had developed a more distinct separation between traditional and digital communication functions, with younger community members managing digital platforms while traditional Marinyo maintained ceremonial roles. Ema utilized a decentralized approach with three Marinyo serving different geographical sections of the community, reflecting adaptation to local topographical challenges. Naku had developed the most specialized Marinyo structure, including dedicated religious messengers for church-related communications and a separate Marinyo for traditional governance functions.

3.3 Data collection procedures

Data collection employed multiple methods over an extended five-month period (May–September 2024) to ensure a comprehensive understanding and triangulation of findings. While 5 months represents a shorter timeframe than some classical ethnographic studies, this duration was determined appropriate based on several factors: the focused nature of the research question on a specific institution rather than entire cultural systems, intensive data collection methods that maximized information gathering within the available timeframe, and ongoing relationships with community members that preceded and continued beyond the formal research period.

The relatively short research time was designed to meet ethnographic research standards through intensive, focused fieldwork that concentrated specifically on communication practices and institutional transformation rather than broad cultural analysis. This approach aligns with focused ethnographic methodologies that prioritize depth over breadth in specific cultural domains.

In-depth interviews were conducted with 17 participants purposively selected based on their knowledge of and involvement in community communication systems. The interview sample included current Marinyo (n = 7) representing different communities and specializations, Raja or traditional leaders (n = 4) from each community, members of customary councils (Saniri Negeri, n = 4), and digital communication managers (n = 2) who handled modern communication platforms in communities with formal digital integration.

Interview protocols were developed to explore participants’ perspectives on Marinyo’s changing roles, message dissemination processes, legitimacy sources, and adaptation strategies in the digital era. Interviews were conducted in Bahasa Indonesia and Ambonese Malay, with translation and back-translation procedures ensuring accuracy. Each interview lasted 60–90 min and was audio-recorded with participant consent.

Participant observation formed a crucial component of data collection, involving systematic observation and documentation of Marinyo in action during various community events, formal announcements, and ceremonial occasions. This included observing traditional announcement processes, community meetings where Marinyo reported to leaders, digital communication practices in community WhatsApp groups and Facebook pages, and ceremonial events where traditional and digital communications converged.

Field notes documented both observable practices and contextual meanings attributed to these practices by community members. Particular attention was paid to non-verbal communication, audience responses, and informal discussions that occurred around formal communication events.

Document analysis examined various written materials related to Marinyo practices and community communication. These included formal community regulations (Peraturan Negeri) regarding communication roles and responsibilities, archived announcements in both traditional and digital formats, documentation of community discussions about communication policies and practices, and historical documents related to the evolution of Marinyo practices.

Digital ethnography was conducted on community WhatsApp groups, Facebook pages, and other digital platforms used for community communication. This involved a systematic analysis of message patterns, language use, participation levels, and integration of traditional communication elements within digital spaces. Ethical protocols ensured that only publicly accessible digital content was analyzed, with community consent for research participation.

Focus group discussions (n = 4, with 6–8 participants each) were conducted in each community, bringing together diverse community members to discuss perceptions of changing communication patterns, preferences for information sources, and attitudes toward hybridization of traditional and digital communication. These sessions provided insights into community reception of communication changes and social implications of hybridization processes.

3.4 Data analysis techniques

Data analysis followed a systematic thematic approach guided by Braun and Clarke (2021) reflexive thematic analysis methodology. This approach was chosen for its flexibility in handling complex, culturally situated data while maintaining analytical rigor.

The analysis process involved six phases: familiarization with the data through repeated reading of transcripts, field notes, and documents while maintaining a reflexive journal to track initial impressions and emerging ideas; systematic coding of meaningful units relevant to the research questions, using both inductive codes emerging from the data and deductive codes derived from theoretical frameworks; organization of codes into potential themes through iterative processes of grouping, regrouping, and refining based on patterns and relationships identified in the data; review of themes against the dataset to ensure internal coherence and distinctiveness, with themes refined, merged, or split as necessary; definition and naming of themes to capture their analytical essence and relationship to research questions; and integration of themes into a coherent analytical narrative that connected findings to theoretical frameworks and research objectives.

The analysis employed constant comparison methods, systematically comparing data across communities, participant types, and contexts to identify patterns, similarities, and differences in hybridization processes. This comparative approach enabled the identification of factors influencing different adaptation strategies and outcomes.

Computer-assisted analysis using NVivo software facilitated systematic coding and pattern identification while maintaining a connection to contextual details. However, the analysis prioritized interpretive understanding over mechanistic coding, ensuring that cultural nuances and contextual meanings were preserved throughout the analytical process.

To enhance trustworthiness, the study employed several validation strategies including data triangulation through comparison of information from different sources (interviews, observations, documents), method triangulation by comparing findings from different data collection approaches, member checking through confirmation of interpretations with key informants during follow-up visits, peer debriefing involving other researchers familiar with Indonesian cultural contexts, and researcher reflexivity through maintenance of detailed reflection journals documenting analytical decisions and potential biases.

Ethical considerations were paramount throughout the research process. Formal ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board at Hasanuddin University. All participants provided informed consent after a detailed explanation of the research purposes, procedures, and potential implications. Community protocols were respected, including consultation with traditional leaders before conducting research activities. While Marinyo’s roles are inherently public, confidentiality was maintained regarding personal opinions and sensitive information. The research is committed to reciprocity through sharing findings with participating communities in accessible formats and supporting community efforts to document and preserve traditional communication practices.

This comprehensive methodological approach enabled a rich, contextual understanding of the complex processes of communication hybridization involving Marinyo as traditional opinion leaders adapting to and integrating with digital communication ecosystems in contemporary Ambonese society.

4 Results

4.1 Marinyo in the structure of Ambonese indigenous communities

The research revealed that Marinyo continues to occupy an important position in the governance structure of Ambonese indigenous communities, though with significant adaptations across the four communities studied. In all communities, Marinyo functioned as an official messenger within the traditional governance structure, operating under the authority of the Raja (traditional leader) and Saniri (customary council), but with varying degrees of formal integration with contemporary administrative systems.

In Negeri Hutumuri, Marinyo maintained a formal position in the governance structure, with specific individuals appointed based on hereditary lineage from clans (soa). As one Marinyo from Hutumuri explained:

“Marinyo ni ada dalam struktur negri, beta su jadi Marinyo su 15 taong. Katong dapa pilih dar raja deng saniri negri, iko soa atau fam yang dar dolo su jadi Marinyo, seng sabarang orang bisa jadi Marinyo, musti pung keturunan yang batul deng musti mangati adat” (Interview, Marinyo Negeri Hutumuri, September 16, 2024).

“Marinyo exists within the governance structure of the Negeri [community]. I have been a Marinyo for 15 years now. The Raja and Saniri select us based on specific clans that have traditionally held the Marinyo position. Not just anyone can become a Marinyo; one must have the right lineage and understand traditional customs.”

The study found variations in Marinyo arrangements across communities. Hutumuri and Rutong each maintained two Marinyo who worked on a rotational basis. Ema employed three Marinyo, each responsible for specific geographical sections of the community. Naku demonstrated the most specialized structure with dedicated Marinyo for general announcements and specific Marinyo for religious communications—referred to as “Marinyo Gereja” (Church Marinyo), who specialized in announcing religious events and death notices.

The Raja of Ema explained their decentralized approach:

“Di katong pung negri ada tiga Marinyo karna katong pung negri basar. Satu Marinyo voor bagiang atas negri, satu di bagiang tenga negri deng satu lai bagiang bawah. Itu su dar dolo bagitu, supaya pesan bisa sampe ka samua orang deng capat” (Interview, Raja Negeri Ema, September 18, 2024).

“In our community, we have three Marinyo because our territory is large. One Marinyo serves the upper section, one for the middle section, and one for the lower section. It has been arranged this way since long ago to ensure messages reach everyone quickly.”

Analysis of community regulations and interview data identified five key criteria for becoming a Marinyo: (1) belonging to specific hereditary clans with traditional rights to the position, (2) possessing thorough knowledge of customs and social structures, (3) having a strong voice and clear communication abilities, (4) physical stamina for traveling throughout the community, and (5) being respected by community members.

The research revealed that while the Marinyo position remains predominantly male-dominated in all four communities, discussions about gender inclusion have begun to emerge. The Raja of Naku noted:

“Beta pikir seng ada alasan voor parampuang seng bisa jadi Marinyo di jaman skarang ni, yang penting dia pung pengetahuan adat deng komunikasi bagus, ada beberapa parampuang di Naku yang pung kemampuan itu labe bae dar laki-laki” (Interview, Raja Negeri Naku, September 17, 2024).

“There is no reason women could not become Marinyo in the current era. What matters is their knowledge of customs and communication skills. Some women in Naku’s abilities in these areas surpass those of men.”

Table 1 compares the structural position and characteristics of Marinyo across the four communities.

4.2 Communication patterns in Marinyo practice

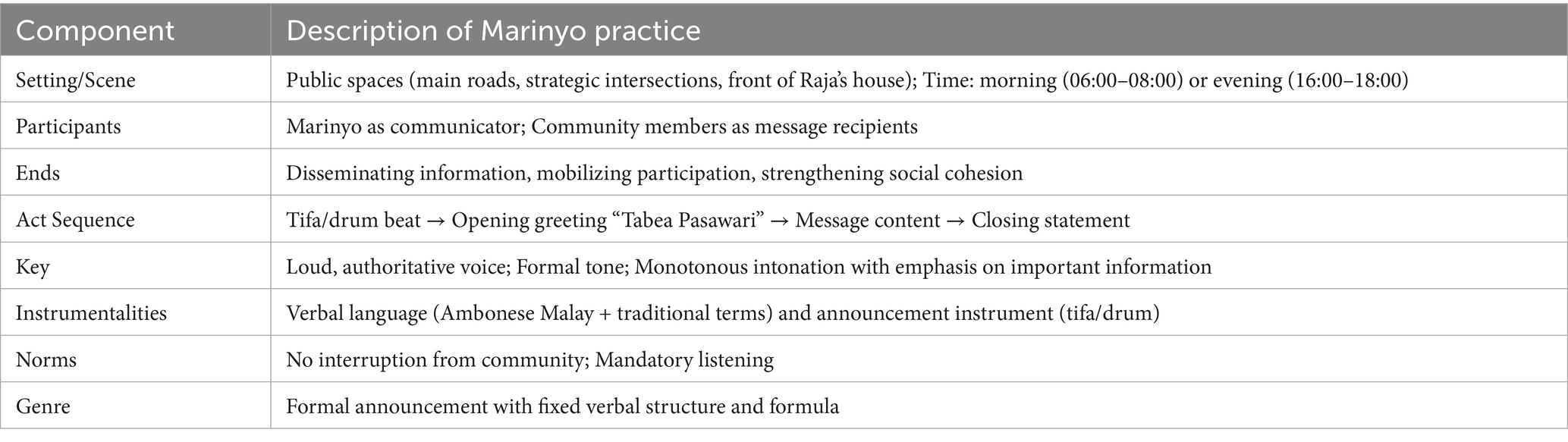

The study revealed distinctive communication patterns in Marinyo practice across all communities. Using Hymes’ SPEAKING framework for ethnographic communication analysis, several consistent elements were identified in Marinyo communication.

Setting/Scene: Marinyo communication typically occurred in public spaces such as main community roads, strategic intersections, and sometimes in front of the Raja’s house. The timing followed established patterns: mornings (around 6:00–8:00 AM) or evenings (around 4:00–6:00 PM).

Participants: Marinyo functioned as the primary communicator, with community members as message recipients. The interaction was predominantly one-way, with no direct feedback mechanism during the announcement process.

Ends (goals): The communication served multiple purposes, including information dissemination from leadership to community, mobilization of community participation in collective activities, and reinforcement of social cohesion.

Act Sequence: Marinyo typically began by beating their tifa (traditional drum) to attract attention, followed by a formal greeting such as “Tabea Pasawari” (Respectful Greetings), then delivering the main message, and concluding with closing formulaic expressions.

Key (tone): Messages were delivered with a loud, authoritative voice with a distinctive cadence. The tone was formal and solemn, with a somewhat monotonous intonation but emphasis on important information.

Instrumentalities: Communication employed verbal language (Ambonese Malay mixed with traditional terms) and the non-verbal sound of the tifa drum as an attention signal.

Norms: Clear norms governed the interaction, with an expectation that community members would listen attentively without interruption when Marinyo spoke.

Genre: The communication took the form of formal announcements with relatively fixed verbal formulae and structures.

A Marinyo from Rutong described their communication process:

“Kalo beta mo kasi tabaos, pertama tu beta pukul tifa dolo tiga kali supaya smua tau kalo ada pengumuman. Abis itu beta bilang “Tabea Pasawari” Tabea voor Raja deng Saniri, Tabea voor masyarakat negeri’ [Salam hormat, Salam untuk Raja dan Saniri, Salam untuk masyarakat negeri, baru beta tabaos ini pengumuman deng suara yang kras. Beta iko samua jalang di negri dar ujung ka ujung di tiap jalan beta barenti, pukul tifa deng kas ulang tabaos” (Interview, Marinyo Negeri Rutong, September 19, 2024).

“When I deliver announcements, I first beat the tifa three times so everyone knows there’s an announcement coming. Then I say ‘Tabea Pasawari, Tabea for the Raja and Saniri, Tabea for the community members.’ Only then do I deliver the actual announcement with a strong voice. I follow all roads in the community from end to end, stopping at each intersection, beating the tifa, and repeating the announcement.”

Field observations confirmed that Marinyo communication exhibited characteristics of high-context communication, as conceptualized by Edward T. Hall, where messages rely not only on spoken words but also on shared contextual understanding, relationships between communicator and audience, and collective knowledge of values and norms.

Table 2 summarizes the Marinyo communication pattern based on Hymes’ SPEAKING framework.

4.3 Typology of messages in Marinyo practice

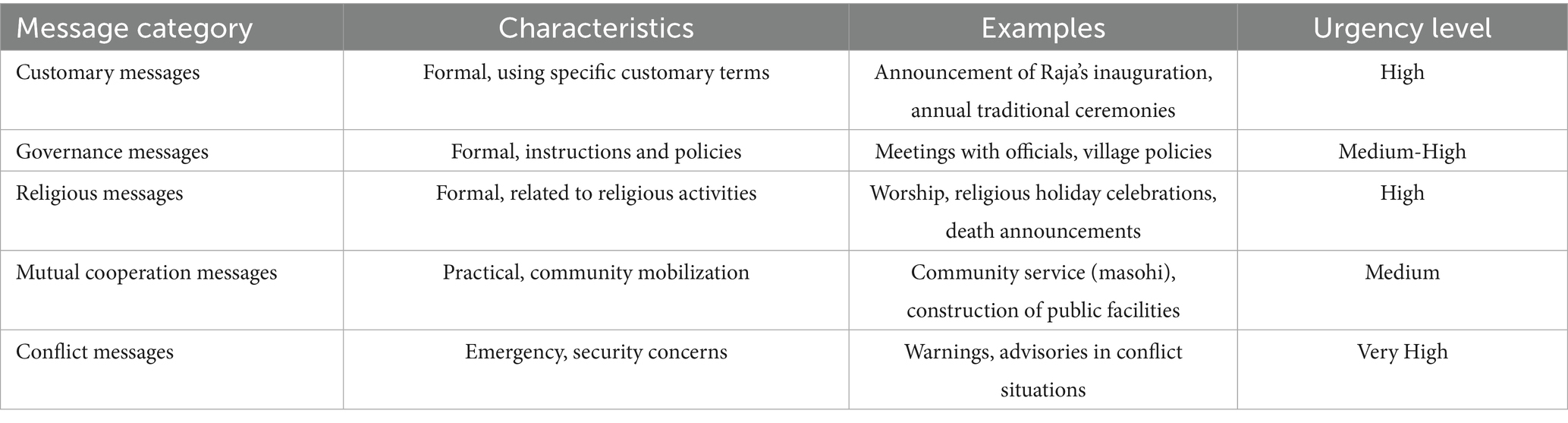

The research identified five distinct categories of messages conveyed through Marinyo across the communities studied:

1. Customary messages: Related to traditional ceremonies, customary meetings, and enforcement of traditional rules.

2. Governance messages: Concerning community policies, formal meetings, and instructions from the Raja.

3. Religious messages: Pertaining to religious activities such as communal worship, religious holiday celebrations, and death announcements.

4. Mutual cooperation messages: Regarding mobilization for community service, development of public facilities, and emergency response.

5. Conflict messages: Warning or advisory messages in conflict situations or potential conflicts.

A Marinyo from Hutumuri provided an example of a typical mutual cooperation message:

“Pesan yang paleng sering beta tabaos tu tentang karja bakti atau masohi, biasanya beta tabaos bagini: ‘Tabea untuk Raja dan Saniri, Tabea untuk masyarakat negeri, beta tabaos beso pagi samua masyarakat dar soa Lewaherila, Sohuat, Moniharapon supaya bakumpul di Baileo jam 7 pagi voor karja bakti kas barsih jalan negeri. Samua kapala keluarga musti datang. Yang seng hadir nanti dapa denda adat” (Interview, Marinyo Negeri Hutumuri, September 16, 2024).

“The message I most frequently announce concerns community service or ‘masohi’. Typically, I announce: ‘Respect to the Raja and Saniri, Respect to the community members, I announce that tomorrow morning all community members from the Lewaherila, Sohuat, and Moniharapon clans should gather at the Baileo [community hall] at 7 AM for community service to clean the village roads. All heads of families must attend. Those who are absent will receive customary penalties.’”

Meanwhile, the Church Marinyo from Naku described religious messages:

“Kalo hari Minggu, beta koliling dar pagi voor kas inga ibadah minggu. Beta bilang jang lupa jemaat gereja ibadah minggu ibadah mulai jam 9 pagi, beta jua kas tau kalo ada orang meninggal, deng pasang, su meninggal deng psang su meninggal ke rumah bapa di surga pada har ini. Jenazah di kuburkan di rumah duka deng dikubur di TPU Naku” (Interview, Marinyo Gereja Negeri Naku, September 17, 2024).

“On Sundays, I go around in the morning to remind people of Sunday worship. I say: ‘Reminder to all church members that Sunday service begins at 9 AM.’ I also announce when someone has passed away, saying: ‘So-and-so has returned to our Father in heaven today. The body will lie in state at the family home and be buried at the Naku cemetery.’”

The research also revealed a hierarchy of messages based on urgency and audience scope. Messages related to emergencies or important events involving the entire community received highest priority and were delivered immediately. Messages intended for specific groups or of a routine nature received lower priority and were typically delivered at designated times.

Table 3 presents the typology of messages in Marinyo practice.

4.4 Marinyo as opinion leaders: two-step flow in practice

The study found that Marinyo functioned as classical opinion leaders in accordance with the two-step flow communication model but with distinctive cultural characteristics. Information flowed from authority figures (Raja and Saniri) to Marinyo, who then interpreted, contextualized, and disseminated it to the broader community.

However, the research revealed that this process was more complex than the classic two-step flow model suggests. The communication process involved multiple stages:

1. Message formulation by traditional authorities: The Raja and Saniri council formulated messages through deliberative processes that considered various perspectives within the leadership structure.

2. Message transmission to Marinyo: Messages were communicated to Marinyo in dedicated meetings that involved explanation of context, expectations, and sometimes discussion of delivery strategy.

3. Interpretation and contextualization: Marinyo interpreted and contextualized messages according to local values and audience understanding before public dissemination.

4. Message delivery with specific protocol: Messages were delivered following established protocols involving traditional instruments, ritualized language, and specific delivery patterns.

5. Clarification and elaboration: After formal announcements, Marinyo often remained available to provide clarification and additional explanations to community members who needed them.

The Raja of Hutumuri explained the interpretive role of Marinyo:

“Marinyo bukang kaya corong yang ida ulang-ulang beta kata. Mar dia pung kemampuan voor bisa terjemahkan beta kata-kata atau pesan ka masyarakat. Ini yang biking dong pung posisi paleng penting di akang negri ni. Dong bisa sederhanakan beta pung parenta deng pasang deng kasi contoh deng kas hubung beta pung kebijakan deng nilai-nilai adat yang su lama masyarakat tau akang. Kalo seng bagini pasti masyarakat ada yang seng mangarti beta pung pasang, karena marinyo makanya sampe oras ni dong mangarti bagus” (Interview, Raja Negeri Hutumuri, September 16, 2024).

“Marinyo is not just a loudspeaker that repeats my words. They could translate my words or messages to the community. This is what makes their position so important in our community. They can simplify my instructions and announcements, provide examples, and connect my policies with traditional values that the community has long understood. Without this, many community members would not understand my messages; it is because of Marinyo that they understand properly.”

A Marinyo from Hutumuri described how they adapted messages for different audiences:

“Pesan yang sama bisa beta tabaos deng cara yang beda tergantung sapa yang dengar beta pung tabaos, waktu beta tabaos deng orang tatua beta pake bahasa adat yang formal, kalo beta tabaos voor anana muda beta pake bahasa gaul bahasa ringan denga da pake lucu-lucu supaya beta pastikan deng car aitu pesan bida dong pahami akang to” (Interview, Marinyo Negeri Hutumuri, September 16, 2024).

“I can deliver the same message in different ways depending on who is listening. When speaking to elders, I use formal traditional language. When speaking to young people, I use more casual language and sometimes humor to ensure they understand the message.”

The study also identified a feedback mechanism in the traditional communication system. Marinyo not only delivered messages from leadership to the community but also conveyed community concerns, questions, or feedback to the Raja and Saniri. The Raja of Hutumuri emphasized the importance of this two-way function:

“Marinyo bantu katong tau apa yang masyarakat piker deng rasa, dong sering kasi saran tentang bagemana keputusan dong tarima atau apa yang dong pikir susah, Informasi ini paleng penting voor kas pasti kalo katong pung jabatang tetap dengar dong pung keluh kesah” (Interview, Raja Negeri Hutumuri, September 16, 2024).

“Marinyo helps us understand what the community thinks and feels. They often advise us on how our decisions are being received or what concerns people might have. This information is crucial to ensure our leadership remains responsive to community needs.”

This feedback function expanded the traditional two-step flow model into a more circular communication pattern, positioning Marinyo as critical nodes in a complex information network rather than mere transmitters in a linear process.

4.5 Digital transformation and hybridization of Marinyo’s role

A central finding of this research was the identification of strategic adaptations through which Marinyo integrated their traditional roles with digital communication technologies. Rather than being replaced by digital media, Marinyo underwent a process of hybridization that transformed their communication practices while maintaining their core cultural functions.

The study identified distinct hybridization patterns across the four communities. In Negeri Hutumuri and Batu Merah (more urbanized communities with higher digital penetration), transformation took a more formalized approach by establishing Communication Departments incorporating digital functions while preserving ceremonial Marinyo roles. The Raja of Batu Merah explained:

“Katong sadar kalo skrang ni tuntutan teknologi su beda deng dolo-dolo, Marinyo tradisional dolo pung keterbatasan dalam jangkau masyarakat yang dong aktivitas su tinggi, katong bentuk bagian kehumasan jadi katong strategi voor pastika pesan dar pemerintah negri dapat masyarakat tarima deng bae, termasuk katong pake media digital lae.” (Interview, Raja Negeri Batu Merah, September 15, 2024).

“We recognize that technological demands today differ from the past. Traditional Marinyo have limitations in reaching community members who are now highly mobile. We established a communications Department as a strategic move to ensure government messages are well-received by the community, including through digital media.”

In contrast, Negeri Urimesing and Naku (more peripheral communities) adopted a more evolutionary approach by developing “Modern Marinyo Teams” that explicitly preserved continuity with traditional Marinyo roles while integrating digital capabilities. These teams consisted of traditional Marinyo who received digital training, supplemented by younger members with technological expertise. The Raja of Urimesing described their approach:

“Katong seng mau kehilangan inti dar marinyo dalam katong pung system komunikasi negri. Marinyo bukang Cuma tabaos pasang, mar jua symbol penting adat deng dia jaga kebiasan tradisi negri yang su ada dar dolo. Katong biking katong sesuaikan deng dia peran supaya sama deng kebutuhan skarang, termasuk katong pake WA deng FB voor jangkau katong warga yang seng bisa hadir langsung dalam katong pung pertemuan negri bagitu” (Interview, Raja Negeri Urimesing, September 22, 2024).

“We do not want to lose the essence of Marinyo in our community communication system. Marinyo is not just a messenger but also an important symbol of tradition who maintains community customs that have existed for generations. We’ve adapted their role to meet current needs, including using WhatsApp and Facebook to reach community members who cannot attend community meetings in person.”

The research identified three forms of communication hybridization in Marinyo practice:

1. Media hybridization: Integration of traditional instruments (tifa drums) and communication channels with digital platforms (WhatsApp groups, Facebook pages, websites). In Negeri Hutumuri, official announcements were simultaneously delivered through traditional Marinyo and posted to community WhatsApp groups, often with accompanying photos or videos of the Marinyo delivering the message.

2. Content hybridization: Traditional message formats and ceremonial language adapted for digital contexts. Analysis of WhatsApp messages in Negeri Urimesing revealed the persistence of traditional opening formulas (“Tabea Pasawari”) and closing expressions in digital communications, maintaining cultural continuity while utilizing new media.

3. Temporal hybridization: Transformation of communication rhythms from traditional time-bound patterns to more continuous flows. While traditional Marinyo operated at specific times (morning/evening), digital communications enabled more constant information flow, creating a layered temporal experience for community members.

A member of the Modern Marinyo Team in Negeri Urimesing explained this hybridization process:

“Katong bage karja iko pasang deng situasi, voor pasang umum kaya jadwal karja sama atau pasang pemerintah, katong bage dar grup WA deng FB. Voor pasang penting kaya orang mati deng bencana katong bilang marinyo bajalang koliling tabaos pake pakiang adat lengkap.” (Interview, Marinyo Modern Team Negeri Urimesing, September 25, 2024).

“We divide tasks based on message type and context. We share general information through WhatsApp groups and Facebook, such as community service schedules or government announcements. We still send Marinyo to deliver announcements in full traditional attire for important information like death announcements or emergencies.”

The study also revealed that the legitimacy basis for Marinyo underwent hybridization. Traditional legitimacy based on customary appointment and cultural knowledge was increasingly supplemented by digital competence and formal professional skills. In more urbanized communities (Hutumuri and Batu Merah), legitimacy was increasingly derived from technical competence and professional communications training. In more traditional communities (Urimesing and Naku), cultural legitimacy remained dominant but was enhanced with digital capabilities.

4.6 Models of communication hybridization

Based on a comparative analysis of the four communities, the research identified two distinct hybridization models that characterized the transformation of Marinyo’s role in the digital era:

1. Divergent hybridization model (observed in Hutumuri and Batu Merah): Characterized by the bifurcation of communication functions, with administrative-informational aspects shifting to digital platforms managed by formal Communications Departments, while ceremonial-symbolic functions remained with traditional Marinyo. This model featured a clear separation between digital and traditional channels, standardized communication formats, and legitimacy primarily derived from technical competence and formal position.

2. Convergent hybridization model (observed in Urimesing and Naku): Characterized by organic integration of traditional and digital elements through “Modern Marinyo Teams” that maintained continuity with traditional roles while incorporating digital capabilities. This model featured more fluid boundaries between digital and traditional communication, adaptive practices based on message type and context, and legitimacy derived from both cultural authority and developing digital competencies.

In communities following the Divergent Model, digital communication dominated everyday information flows, while traditional Marinyo were reserved primarily for ceremonial occasions and formal cultural events. A Marinyo from Batu Merah reflected on this shift:

“Dulu, menjadi marinyo adalah tentang menguasai seni komunikasi lisan, mengenal setiap sudut negeri, memahami konteks sosial dari setiap keluarga. Sekarang, semua reduksi menjadi teks di layar. Ya, informasi tersampaikan, tapi nuansa, makna, dan ikatan sosial yang terbentuk melalui tatap muka itu tidak tergantikan oleh teknologi. Ketika saya tampil dalam upacara adat, saya merasa seperti artefak budaya yang dipamerkan, bukan lagi sebagai bagian integral dari sistem komunikasi sehari-hari.” (Interview, Ceremonial Marinyo Negeri Batu Merah, September 19, 2024).

“In the past, being a Marinyo was about mastering the art of oral communication, knowing every corner of the community, and understanding the social context of each family. Now, everything is reduced to text on a screen. Yes, information is conveyed, but the nuance, meaning, and social bonds formed through face-to-face interaction cannot be replaced by technology. When I perform in traditional ceremonies, I feel like a cultural artifact on display, no longer an integral part of the everyday communication system.”

In contrast, communities following the Convergent Model maintained a more balanced integration of traditional and digital practices. A young member of the Modern Marinyo Team in Urimesing explained:

“Saya tidak melihat penggunaan WhatsApp atau Facebook sebagai ancaman terhadap tradisi marinyo. Sebaliknya, ini adalah cara kami mengadaptasi tradisi agar tetap relevan. Dalam grup WhatsApp, kami masih menggunakan struktur pesan yang sama seperti yang digunakan marinyo tradisional, dengan salam pembuka dan penutup khas. Saya belajar banyak dari marinyo senior tentang cara menyampaikan pesan dengan hormat dan efektif, hanya medianya yang berbeda. Pengetahuan tradisional tidak hilang, tapi beradaptasi.” (Interview, Young Modern Marinyo Team Member Negeri Urimesing, September 26, 2024).

“I do not see the use of WhatsApp or Facebook as a threat to Marinyo tradition. Rather, it’s how we adapt tradition to remain relevant. In WhatsApp groups, we still use the same message structure as traditional Marinyo, with characteristic opening and closing greetings. I’ve learned much from senior Marinyo about conveying messages respectfully and effectively; only the medium is different. Traditional knowledge is not lost but adapted.”

The research found that these hybridization models had varying implications for cultural sustainability and community cohesion. The Divergent Model enabled efficient information dissemination and standardization but risked marginalizing traditional communication practices to purely ceremonial functions. The Convergent Model preserved greater cultural continuity and intergenerational knowledge transfer but sometimes sacrificed efficiency and standardization in communication.

Factors influencing which model prevailed in a community included demographic characteristics (urban/rural, homogeneous/heterogeneous), digital penetration rates, leadership vision (Raja and Saniri), and the strength of traditional governance structures.

4.7 Social implications of communication hybridization

The research identified significant social implications arising from the hybridization of Marinyo communication practices across all communities studied. These implications manifested in changes to social interaction patterns, transformation of participation in decision-making processes, and tensions between cultural revitalization and erosion.

In communities following the Divergent Hybridization Model (Hutumuri and Batu Merah), the research observed:

1. Reduction in face-to-face interactions: With the dominance of digital communication, a significant reduction occurred in direct interactions between community members in the context of information dissemination.

2. Communication space fragmentation: The formation of parallel communication spaces (digital and physical) sometimes creates information gaps between different community groups.

3. Increased passive participation: Rising “information consumption” without active involvement in communal discussions.

4. Access democratization: Better information access equity, especially for previously marginalized groups (e.g., residents in remote areas).

A Saniri member from Batu Merah acknowledged these dynamics:

“Media digital membantu kami mempublikasikan keputusan dan mendapatkan input dari lebih banyak warga. Namun, tantangannya adalah format digital cenderung menguntungkan kelompok tertentu yang lebih vokal dan melek teknologi. Suara dari kelompok lansia atau kurang teredukasi sering kali tidak terwakili dalam forum-forum digital.” (Interview, Saniri Negeri Batu Merah, September 18, 2024).

“Digital media helps us publicize decisions and get input from more residents. However, the challenge is that digital formats tend to favor certain groups who are more vocal and technologically literate. Voices from elderly or less educated groups are often underrepresented in digital forums.”

In communities following the Convergent Hybridization Model (Urimesing and Naku), the study observed different patterns:

1. Complementary interaction spaces: Creation of complementary interaction spaces between digital and physical realms, with relatively clear functional divisions.

2. Strengthened diaspora networks: Reconnection of migrated community members through digital platforms, creating new forms of community engagement.

3. More effective collective mobilization: A Combination of digital and direct communication enhances the effectiveness of community mobilization for collective activities.

4. Multi-generational dialogue: Digital platforms are becoming spaces for dialogue between younger and older generations, with Modern Marinyo Teams mediating.

The Raja of Urimesing explained their hybrid approach to community decision-making:

“Untuk keputusan penting, kami tetap mengadakan pertemuan fisik di Baileu (balai adat), tapi sekarang dilengkapi dengan sesi diskusi di grup WhatsApp sebelumnya. Tim Marinyo Modern bertugas mengumpulkan dan mengorganisir aspirasi dari kedua forum. Mereka juga memastikan warga yang tidak aktif di WhatsApp tetap mendapatkan informasi dan kesempatan menyampaikan pendapat melalui marinyo keliling. Dengan cara ini, kami mendapatkan perspektif yang lebih luas tanpa mengecualikan siapapun.” (Interview, Raja Negeri Urimesing, September 22, 2024).

“For important decisions, we still hold physical meetings at the Baileu (traditional hall), but now supplemented with prior discussion sessions in WhatsApp groups. The Modern Marinyo Team collects and organizes input from both forums. They also ensure residents who aren’t active on WhatsApp still receive information and opportunities to express opinions through circulating Marinyo. This way, we gain broader perspectives without excluding anyone.”

The research also revealed complex dynamics between cultural revitalization and erosion. In all communities, digital media was used to document traditional practices, including Marinyo performances, creating digital archives of cultural knowledge. However, in communities following the Divergent Model, traditional communication practices were increasingly confined to ceremonial contexts, risking the loss of their everyday relevance and the intergenerational transmission of associated knowledge.

In contrast, communities following the Convergent Model demonstrated “adaptive continuity” by maintaining core elements of traditional communication within contemporary practices. This was evident in the persistence of conventional language formulas, message structures, and communication protocols within digital communications, as well as the active involvement of traditional Marinyo in digital adaptation.

5 Discussion

5.1 Theoretical contributions to hybridization theory

This study extends media hybridization theory beyond its traditional applications in Western political and mass media contexts to indigenous communication systems, revealing new dimensions of how local communities strategically negotiate global technological forces. The findings challenge linear narratives of technological replacement by demonstrating how traditional institutions like Marinyo undergo strategic transformation that maintains cultural continuity while embracing technological capabilities.

The identification of Divergent and Convergent Hybridization Models contributes to García Canclini (2005) the conceptualization of hybridization as “sociocultural processes in which discrete structures or practices combine to generate new structures, objects, and practices.” While García Canclini’s framework emphasized the creative potential of hybrid formations, this study reveals that hybridization outcomes vary significantly based on community agency, leadership vision, and the strength of traditional governance structures.

The research findings align with and extend Plenković and Mustić (2020) the analysis of “media communication and cultural hybridization of digital society.” Their emphasis on active community participation in shaping technological adoption processes is confirmed by this study’s findings, particularly in Convergent Model communities where traditional leaders actively guided hybridization processes to preserve cultural values while gaining technological benefits.

Comparison with Sani and Obi (2025) the analysis of “African Traditional Communication System in the Age of Hybridity” reveals both similarities and differences in how indigenous communities navigate digital transformation. Like African communities in their study, Ambonese communities demonstrated “selective appropriation” of digital technologies. However, the Ambonese case reveals more complex patterns of institutional adaptation that go beyond simple technology adoption to include fundamental restructuring of communication roles and legitimacy sources.

5.2 Opinion leadership in hybrid media ecosystems

The transformation of Marinyo’s role as an opinion leader provides valuable insights into how traditional authority structures adapt to digital communication environments. The research extends Katz et al. (2017) two-step flow communication theory by revealing how digital technologies create multiple, parallel information flow patterns that complement rather than replace traditional opinion leadership.

In Convergent Model communities, the emergence of “Modern Marinyo Teams” represents what might be termed a “distributed opinion leadership” model, where traditional authority is maintained while technical capabilities are distributed across multiple individuals. This finding challenges assumptions about digital communication democratizing or flattening authority structures, instead revealing how traditional authority can be strengthened through strategic technological integration.

The research confirms Coleman and Freelon (2016) observation that traditional opinion leaders maintain substantial influence in communities with strong social bonds, even as digital communication transforms interaction patterns. However, this study reveals that maintaining influence requires active adaptation and strategic technology adoption rather than simple resistance to change.

The bidirectional communication function of Marinyo, serving as both information disseminators and feedback collectors, demonstrates how traditional opinion leaders can enhance their relevance by leveraging digital technologies to strengthen their intermediary roles. This finding extends Weimann (1994) the conceptualization of opinion leaders as “gatekeepers” and “interpreters” by revealing how digital tools can amplify these traditional functions.

5.3 Cultural sustainability and adaptive continuity

The research provides evidence for what might be termed “adaptive continuity” — the ability of traditional institutions to maintain cultural essence while transforming operational practices. This concept offers a more nuanced understanding of cultural sustainability than approaches that emphasize preservation versus change.

The study’s findings support arguments Ginsburg et al. (2002) about the importance of culturally grounded approaches to media technology adoption. Communities that maintained agency in determining how technologies were integrated into local practices were more successful in preserving cultural continuity while gaining technological benefits.

Comparison with Uche et al. (2020) research on “Digital Media, Globalization and Impact on Indigenous Values and Communication” reveals both convergent and divergent patterns. Like the communities in their study, Ambonese communities demonstrated the ability to infuse global technologies with local meanings and practices. However, the Ambonese case reveals more systematic institutional adaptation that goes beyond individual technology use to include formal community-level policies and structures.