- 1School of Business, Qingdao University of Technology, Qingdao, China

- 2School of Health Management, Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jinan, China

Anthropomorphism strategies have been widely applied in brand marketing activities such as advertising, service communication, and word-of-mouth, and have become an important marketing strategy for many brands. However, prior research has focused on single-brand contexts, leaving the effects and mechanisms of co-brand anthropomorphism underexplored. Drawing on anthropomorphism theory and narrative transportation theory, this study constructs a model to examine how co-brand anthropomorphism influences consumers’ evaluations and intentions toward co-branded products. Three experimental studies were conducted. The studies show that: Compared to non-anthropomorphism, anthropomorphism significantly enhances consumers’ evaluations and purchase intentions for co-branded products, with narrative transportation mediating this effect. The type of co-branding appeal moderates the results: anthropomorphism is effective for abstract appeals but not for specific appeals. The findings offer practical insights for brands to leverage anthropomorphism in co-branding campaigns, improving ad persuasion effectiveness.

1 Introduction

In the trend that consumer demands are increasingly personalized, younger, and diversified, how brands can stand out from a large amount of marketing information and consumers’ limited energy and win consumers’ attention and favor has become a common problem that urgently needs to be solved (Besharat and Langan, 2014; Lamberton and Stephen, 2016). Co-branding, as a win-win marketing strategy, can not only effectively attract consumers’ attention but also enhance brand soft assets and market dominant position (Huang, 2017; Nguyen et al., 2020). In today’s saturated market, where consumers are bombarded with countless marketing messages daily, co-branding serves as a critical tool for brands to break through the noise and create memorable, differentiated experiences. This is especially vital for brands targeting younger demographics, who exhibit shorter attention spans and higher expectations for authenticity and creativity in brand communications. Scholars pay more attention to a core question: how brands can more effectively achieve co-branding and try to explore the internal logic of the impact of this brand behavior on consumers (Rajagopal and Burnkrant, 2009; Swaminathan et al., 2015).

In co-branding practice, marketers have gradually paid attention to the role of anthropomorphism and regarded it as an effective means to enhance the effect of co-branding marketing. Some new cases show that implementing anthropomorphism strategies in co-branding may bring better marketing results. For example, HEYTEA and PECHOIN transformed into “the two beauties in Shanghai” Axi and Aqu, integrating classic Shanghai elements of the Republic of China into co-branded products, which were highly sought after by young consumers; Sprite and Jiang Xiaobai became youth partners with different personalities, interacting and teasing each other, and their “lemon sparkling wine” product was widely loved by consumers. These successes highlight the untapped potential of anthropomorphism in co-branding, suggesting that humanized brand interactions may resonate more deeply with consumers than traditional advertising approaches. However, despite these promising examples, many brands still struggle to implement anthropomorphism effectively in co-branding campaigns, often due to a lack of systematic understanding of its psychological mechanisms and boundary conditions. In theoretical research, although anthropomorphism has been widely proven to be an effective strategy in the marketing practice of single brands (Aggarwal and McGill, 2007), it can make consumers have a positive response to a specific brand, such as increasing product affinity (Puzakova et al., 2013) improving brand evaluation (Zhang and Wang, 2023), and enhancing consumer intention to use robots for delivery (Xu et al., 2024). The current literature mainly explored the effects of anthropomorphism of a single brand in different situations, analyzing consumers’ cognition and psychological perception towards a specific brand. These research conclusions also provide solid and powerful inspiration for our article.

However, the current research has yet to demonstrate whether the anthropomorphism of cobrands positively influences these consumer responses. While anthropomorphism has been widely studied in single-brand contexts, its effects on co-branding remain unclear. Specifically, critical questions arise: Will consumers identify with and develop positive emotions toward the anthropomorphized characters in co-branding campaigns? How do they make sense of the relationship between co-brands when both are humanized? Does co-brand anthropomorphism lead to more favorable product assessments and higher purchase intent compared to single-brand cases? To address these questions, we draw on narrative transportation theory (Green and Brock, 2000) to select our mediating variables. Narrative transportation—a state of immersion into a story—has been shown to enhance persuasion by reducing counter-arguing and increasing emotional engagement (Van Laer et al., 2019). We propose narrative transportation as the key mediator because anthropomorphized co-brands often create character-driven narratives, and transportation into these narratives may explain how anthropomorphism influences consumer responses. For the moderating variable, we focus on the type of co-branding appeal (functional vs. emotional), as prior research suggests that narrative effects vary significantly based on message framing (Escalas, 2004). Functional appeals emphasize practical benefits, while emotional appeals leverage storytelling—making this a theoretically relevant boundary condition for anthropomorphism effects. These questions are pivotal because co-branding anthropomorphism involves complex interactions between multiple brand personas, which may differ fundamentally from single-brand scenarios. For instance, humanized co-brands could create synergistic storytelling effects (e.g., enhanced relatability) or introduce new challenges (e.g., role conflicts). Yet, no study has empirically examined these dynamics or the underlying mechanisms (e.g., narrative transportation) that drive consumer responses. Addressing these gaps is essential to advance the theoretical understanding of co-branding and provide actionable insights for marketers leveraging co-branding strategies.

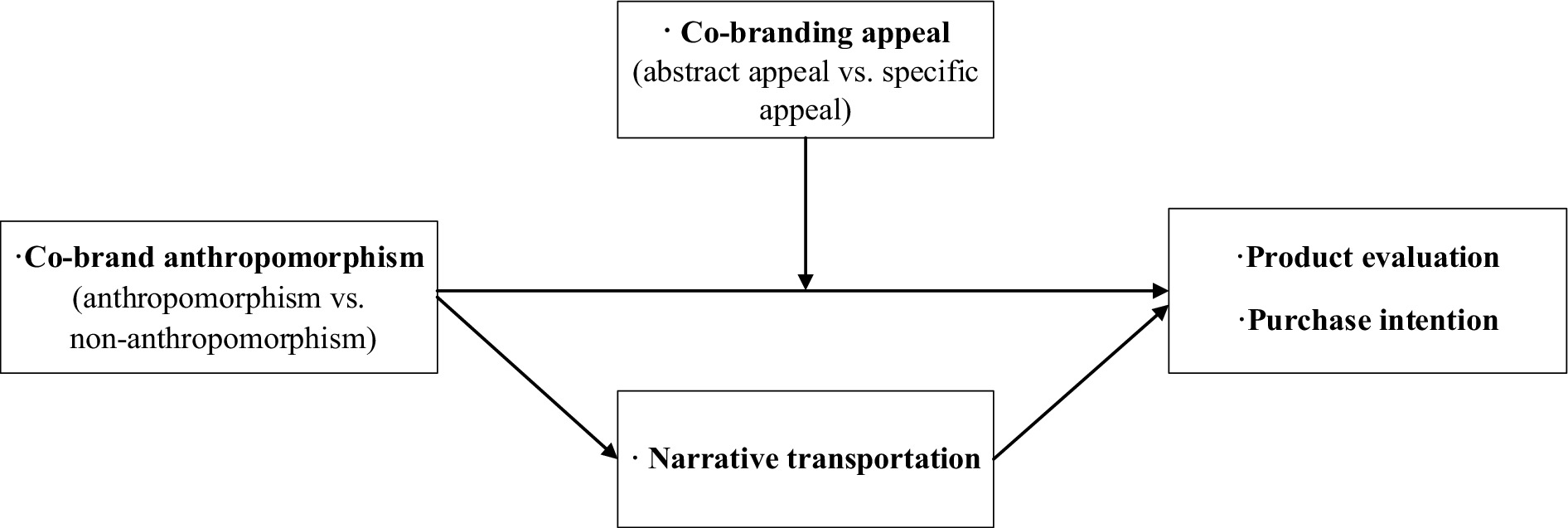

The research constructs a theoretical model and proposes hypotheses around the relationships among cobrand anthropomorphism, narrative transportation, type of co-branding appeal, product assessment, and purchase intent based on the narrative transportation theory. This paper makes up for the lack of attention in the existing literature on cobrand anthropomorphism research, extends the research perspective of anthropomorphism from single-brand contexts to co-branding contexts, and has certain theoretical significance for research on the mechanism and boundary definition of co-branding advertising. The research conclusions have important practical implications for brands to effectively use co-branding and anthropomorphism in their marketing approaches.

2 Literature review

2.1 Co-branding

Co-branding refers to any combination of two brands in marketing environments such as advertising, products, and distribution channels, which is a close cooperative relationship formed between cobrands. In the process of co-branding, the participating brands maintain their unique characteristics, find the fit between themselves and the partner brand based on their brand connotations, characteristics, and unique advantages, and carry out a series of marketing activities for the target consumer group (Huang, 2017; Górska-Warsewicz, 2024). Usually, cobrands create a unique product that contains the characteristics of both brands. Generally, co-branding activities are short-term promotional behavior rather than a long-term brand alliance or a specialized sub-brand matrix.

Previous scholars have fully studied the antecedents of the co-branding effect. Studies have shown that in co-branding, consumers’ evaluation of the focal brand is affected by the partner. The alliance between high-equity brands endows the focal brand with a more positive image and has a positive impact on the partner brand (Washburn et al., 2000). In addition, the success of co-branding largely depends on the fit between brands, such as the fit of product functions (Lafferty et al., 2004), brand image (Baumgarth, 2004), and brand attributes (Jian et al., 2021). Most of the existing literature has carried out exploratory research based on schema congruity theory and analyzed cognitive fluency as an important mediating mechanism (Johan Lanseng and Erling Olsen, 2012; Estes et al., 2012). However, scholars are more concerned about why brands should ally and how to more effectively achieve co-branding (Swaminathan et al., 2015). The deep logical relationship of co-branding urgently needs to be further explored.

2.2 Anthropomorphism

Anthropomorphism refers to endowing brands with human characteristics to make them have human-like properties and communicate more effectively with consumers, thereby encouraging consumers to have a more positive response (Guido and Peluso, 2015; Kim and Swaminathan, 2021; Zhang and Wang, 2023). There is a special inductive reasoning process for consumer’s perception of brand anthropomorphism. Through this process, consumers ascribe human-like attributes, purposes, ideas, or possible mental states to brands, akin to those of other actual or conceptual agents, thereby elevating the overall brand evaluation.

Earlier research efforts have mainly concentrated on exploring the internal mechanism of how anthropomorphism in single-brand contexts affects consumers’ perception and evaluation (Aggarwal and McGill, 2007; Cohen, 2014; Qin et al., 2024). However, emerging studies have initiated a preliminary exploration into the function of anthropomorphism in the realm of brand partnerships and co-branding. According to He et al. (2018), anthropomorphism prompts individuals to perceive co-branding as a special social relationship when the brand alliance breaks up, anthropomorphism will enhance consumers’ negative evaluation of the co-branding. Han et al. (2023) discovered that attributing human-like qualities to co-brands can enhance consumers’ assessment and likelihood of purchasing co-branded products, mainly because anthropomorphism enables consumers to perceive that cobrands, like social people, have the intention to establish a long-term and stable cooperative relationship. Based on the above research conclusions, in the complex context of multi-brand cooperation, the impact effect and mechanism of cobrand anthropomorphism on consumers’ behavioral intention urgently need to be further explored.

2.3 Narrative transportation

Narrative transportation theory is widely used in individual psychological research. It is a theory about the state of story receivers. That is, people immersed in the story will have a strong emotional experience and identify with and have positive emotions toward the story’s characters and situations, thereby enhancing the persuasiveness of the story (Zheng, 2014; Brechman and Purvis, 2015). The emotional response and persuasiveness brought by narrative transportation is a unique psychological process that includes attention, imagination, and emotion (Green and Brock, 2000). In this process, individuals will have an almost real mental representation of the scene described in the story and empathize with the characters in the story. As the story unfolds, they will experience a strong emotional response (Chronis, 2008; Thomas & Thomas and Grigsby, 2024).

Narrative transportation affects consumers’ construction of brand meaning. When receiving advertising information flows, consumers will enter a narrative state and complete the decoding, processing, and internalization of brand meaning (Escalas, 2004). Through carefully constructed stories or plots, brands convey their deep-seated concepts to consumers to gain their recognition (Xu et al., 2020), enhance consumers’ attitudes (Zheng, 2014), and brand evaluation (Brechman and Purvis, 2015). Narrative transportation visualizes products, services, or brands, making it easier for consumers to understand the symbolic meaning of brands, deepening consumers’ understanding of brand meaning, and improving marketing effectiveness (Van Laer et al., 2019). Cobrand skillfully integrates anthropomorphic images into the advertising story of co-branding marketing, which can skillfully use anthropomorphism to deepen consumers’ emotional resonance and identification with co-branded products in terms of values, concepts, visions, product functions, and innovative attributes. Narrative transportation is a breakthrough point in this study to explore the mechanism of cobrand anthropomorphism. It can effectively stimulate consumers’ emotional connection and then enhance the marketing effect of cobrands.

3 Research hypotheses

3.1 The main effect of cobrand anthropomorphism

Anthropomorphism endows brands with human characteristics, making consumers regard brands as real existences with emotions, thoughts, souls, personalities, and autonomous behavioral awareness, promoting consumers to understand the cooperative relationship between cobrands, and then may improve consumers’ perception and evaluation of the brand (Puzakova et al., 2013; Chu et al., 2019). On the one hand, consumers’ processing of brand information with anthropomorphism strategies is more fluent. Anthropomorphism can vividly express the specific characteristics and properties of products and brands, thereby reducing the cognitive resources consumed by consumers (Aggarwal and McGill, 2007), which is beneficial to improving the processing fluency of consumers’ advertising information, reducing consumers’ risk perception, and improving consumers’ evaluation (Kim and McGill, 2011). In addition, brand anthropomorphism hinders consumers’ self-control, thereby reducing the sense of conflict in product consumption and improving individuals’ evaluation and preference for information(Hur et al., 2015). Therefore, cobrands can use anthropomorphism to ease consumers’ perceived barriers in brand and product fit and improve consumers’ positive perception of cobrands.

On the other hand, individuals experience interpersonal communication like the real world, generate trust and pleasure in socialized communication, and meet social interaction needs. Since the dimensions of brand personality are like those of human personality (Aaker, 1997), anthropomorphism improves consumers’ perception of brand personality (Delbaere et al., 2011), makes consumers form self-consistency based on self-concept similarity with the brand, makes the relationship between consumers and the brand more socialized, and then establishes an interpersonal relationship with a “similar to me” brand (Guido and Peluso, 2015). Brand anthropomorphism brings a sense of belonging to consumers through the creation of relationship value (Chen and Yang, 2017), enhances trust with customers, and then improves product evaluation. Similarly, since cobrand anthropomorphism endows brands with human traits and emotions, it meets consumers’ needs for social belonging. Consumers can use more familiar socialized cognitive resources to understand the brand roles and relationships in co-branding. Therefore, the cobrand image and co-branded product characteristics will become more vivid and three-dimensional, and consumers can establish a deep emotional connection with them. This emotional connection makes them find an emotional resonance with the cobrand. Therefore, the cobrand anthropomorphism strategy can effectively improve consumers’ evaluation and win more market recognition for the brand. Thus, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

H1: Cobrand anthropomorphism can elevate consumers’ evaluations and increase their intention to purchase co-branded products.

3.2 Mediating variables: narrative transportation

Consumers’ deconstruction process of brand anthropomorphism is the understanding, processing, and interpretation of anthropomorphic cues. In this process, consumers enter a narrative transportation state due to their immersion in anthropomorphic information. Consumers are vigilant about advertisements with obvious persuasion intentions because the persuasive motivational intention will trigger consumers’ attribution intention (Fein, 1996). As a relatively subtle form of persuasion, a story is less likely to arouse consumers’ antipathy because it does not present an obvious persuasion attempt. The effect of narrative transportation is based on the mechanism of “self-referencing.” Self-referencing involves a cognitive procedure in which individuals compare and comprehend external information relative to their internally stored self-relevant details (Debevec and Romeo, 1992). The self-persuasion generated by self-referencing is a mechanism in which consumers make their cognitive resources consistent with the cognitive resources required for information processing through self-interpretation of the story. The self-connection triggered by the story is a psychological activity actively participated in by consumers. In this process, understanding and reconstructing the story are mainly achieved through the invocation of empathy and imagination. Among them, empathy refers to the story receiver trying to grasp the experiences of the narrative character and immerse oneself in the story world through an analogous perspective (Van Laer et al., 2019). Imagination is a form of psychological expression of unreality. An individual matches the story with the story in memory, actively participates in story shaping through familiar images, personal experiences, similar stories, etc., integrates fragmented plots, and actively fills in narrative gaps (Chronis, 2008). Therefore, consumers interpret and understand the input information according to their prior knowledge, invoke all evaluation and description information related to the brand, and connect the story with themselves as receivers, thereby enhancing their understanding and evaluation of the advertising information.

Anthropomorphism endows brands with human attributes, characteristics, or spirits, forms the roles and plots of advertising stories, promotes consumers to generalize anthropomorphic things through self-knowledge, evokes consumers’ “self-connection,” and promotes consumers’ understanding and recognition of the cobrand relationship and co-branded products. In this process, consumers compare the self-related information in memory with the input information to achieve the connection between the story and the consumer self and generate higher perceived fluency and emotional experience (Debevec and Romeo, 1992). On the one hand, the anthropomorphic story character stimulates consumers’ empathy, makes consumers resonate with the brand story, evokes consumers to have emotional interaction, and thus improves consumers’ evaluation (Escalas, 2004; Shen et al., 2014). On the other hand, consumers connect the story characters, and the brand image becomes more vivid and visualized in the imagination process, which further makes consumers have self-connection and brand connection construction. In addition, anthropomorphism promotes consumers’ social perception, makes consumers more actively interact with brands in a parasocial relationship (Tsao, 1996), and improves consumers’ attitudes and purchase intention of co-branded products in the “quasi-social interaction” process. Consequently, we posit the following hypothesis:

H2: Narrative transportation functions as a mediator in the association between anthropomorphism and both the evaluation of co-branded products and purchase intent.

3.3 Boundary condition: co-branding appeal

In the process of brand cooperation, both will retain their unique brand characteristics and fully consider the brand characteristics of the other party to achieve complementary advantages. Brand characteristics include both specific characteristics and abstract characteristics. Specific characteristics include functional characteristics, iconic elements, brand symbols, etc., and abstract characteristics include the brand’s value concept, symbolic meaning, and brand vision (de Chernatony et al., 2006). The focal brand may achieve co-branding with the partner brand by strengthening its unique function, realizing a concrete co-branding appeal; or it may achieve an alliance with the partner by promoting its value orientation, realizing an abstract co-branding appeal. Different types of co-branding appeals influence the effectiveness of cobrand anthropomorphism. To theoretically contextualize this, the study categorizes co-branding appeals into two types based on prior literature. Abstract appeals refer to that co-branding emphasizes the fit and sharing of the concepts, values, and brand cultures between partner brands, reflecting the symbolic and emotional characteristics of the brand (Xiao and Lee, 2024); while specific appeals refer to highlighting the common interest points, complementarity, and additional value brought by the cobrands through the specific characteristics and advantages of products or services of different brands, highlighting their functionality and practicality to meet consumers’ specific needs (Hornik et al., 2017).

Abstract appeals enable consumers to perceive the core values and cultural concepts conveyed by the brand. This emotional experience resonates with consumers’ inner emotions, fulfilling their psychological needs and establishing deeper emotional bonds. As anthropomorphism fosters interpersonal connections (Guido and Peluso, 2015), it enhances emotional engagement, elicits stronger positive emotions, and stimulates consumers to have positive product preferences and purchase intentions. Thus, abstract appeals align more effectively with anthropomorphic co-branding strategies. On the contrary, specific appeals emphasize product functionality, highlighting the tangible benefits for consumers and addressing their utilitarian needs. By presenting rational attributes, specific appeals enhance consumers’ sense of realism and trust, thereby promoting positive consumption behaviors. This paper argues that specific appeals are more compatible with non-anthropomorphic co-branding, as consumers evaluate functional innovations (e.g., usability) more effectively through direct, low-cognitive-risk presentations. Thus, we posit the following hypothesis:

H3: Co-branding appeal (abstract appeal vs. specific appeal) can exert a moderating effect on the effectiveness of co-brand anthropomorphism. Specifically, under the abstract appeal, anthropomorphism has a significant effect on consumer evaluation and willingness; conversely, under specific appeal conditions, the impact of non-anthropomorphism is more significant.

The conceptual model is shown in Figure 1.

4 Study 1: effectiveness of cobrand anthropomorphism

The main purpose of Study 1 is to test H1, that is, compared with the non-anthropomorphic condition, anthropomorphism of co-branded entities results in enhanced evaluation and increased intention. We use two real brands for analysis and provide preliminary evidence for H2.

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Design

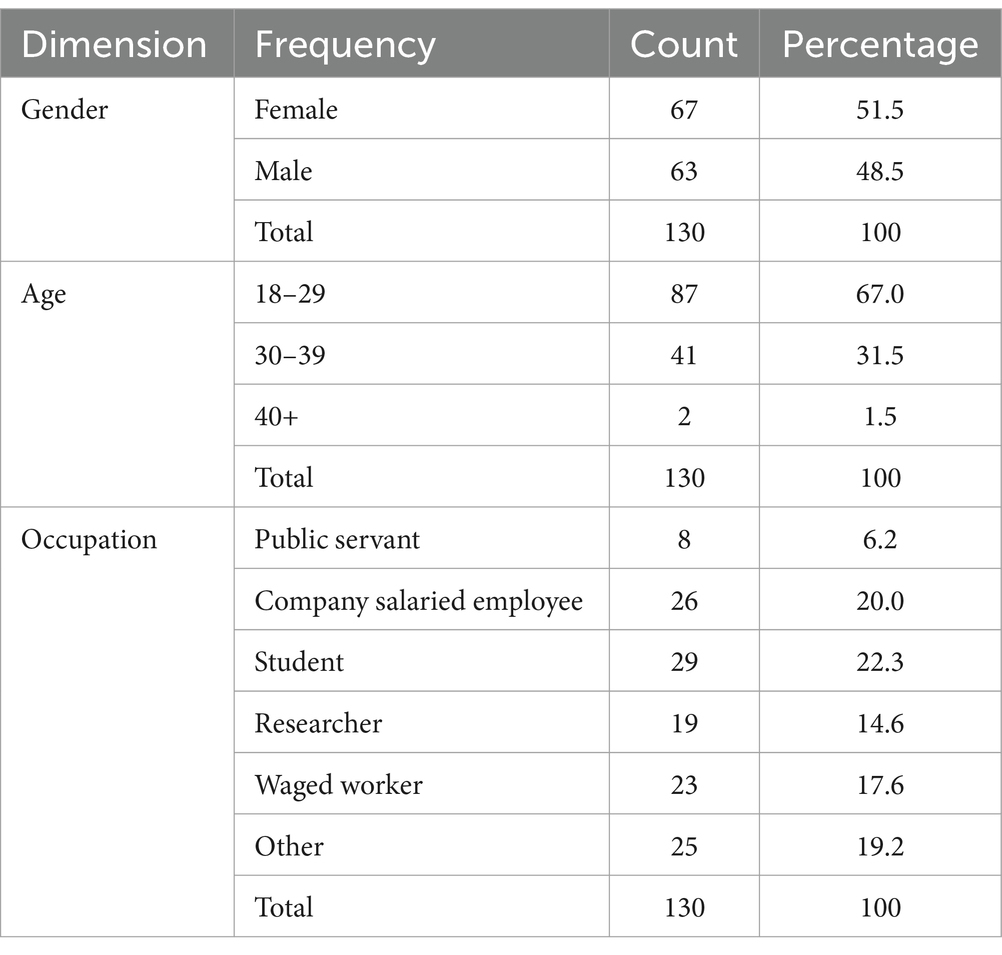

Participants were recruited through Credamo (a professional online survey platform in China, www.credamo.com), which is widely used for academic research and provides high-quality data collection services with rigorous participant screening mechanisms. Recruitment criteria included: (1) being 18 years or older, (2) having purchased co-branded products in the past 6 months, and (3) being active users of beverage products. Participants were enlisted to contribute to our research through an online survey platform. A total of 130 participants (Mage = 25.56, SDage = 6.81, 48.5% male, 98.5% of participants aged between 19 and 40 years; refer to Table 1) were enlisted and divided into two groups: one exposed to the anthropomorphic scenario and the other to the non-anthropomorphic scenario.

4.1.2 Procedure

Before the formal study, 38 consumers (57.9% males, Mage = 20.42) were recruited through a pre-test for interviews and questionnaire surveys. Through screening and sorting, 18 categories (107 types) of co-branded products were identified, including clothing, shoes, cosmetics, mobile phones, beverages, food, bags, etc. To avoid the “ceiling effect,” this paper selects beverage products as the study commodity for Study 1.

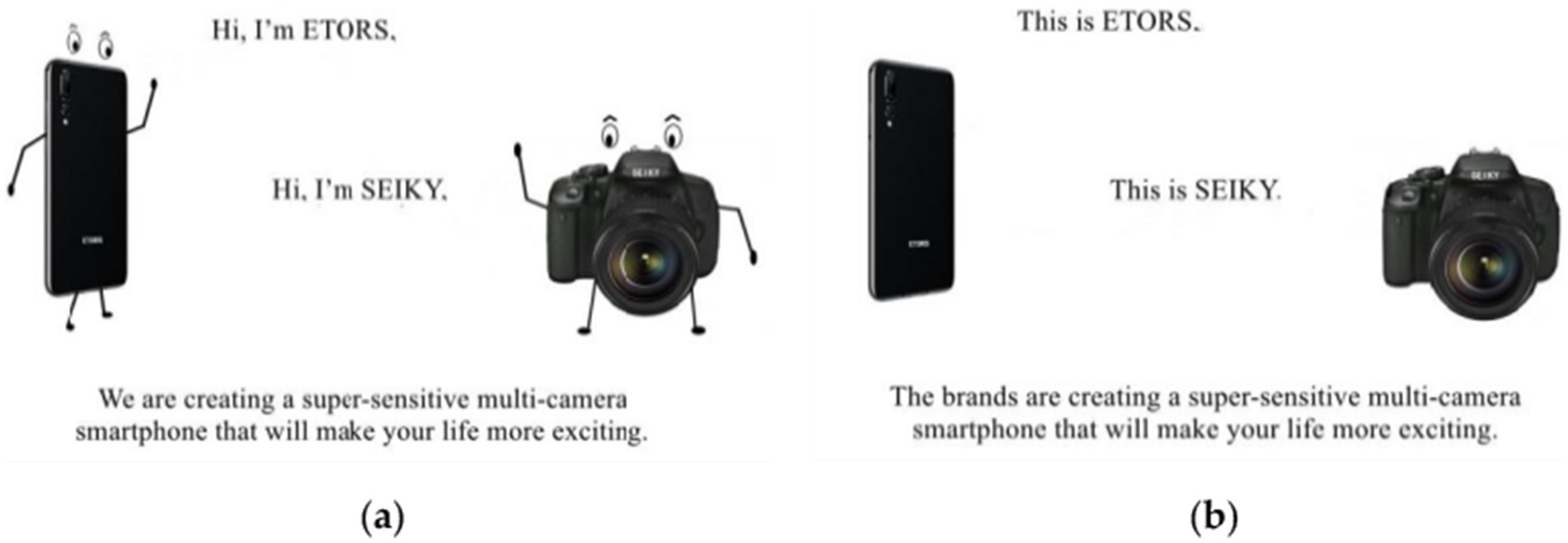

In the formal study, this paper analyzes the co-branding marketing of two real brands, “Sprite” and “JOYBO.” Referring to the research of Aggarwal and McGill (2007), corresponding posters and advertising slogans were designed for the anthropomorphic condition. Specifically, the anthropomorphic condition employed first-person pronouns, whereas the non-anthropomorphic condition utilized third-person pronouns (refer to Figure 2). During the formal study process, the participants were required to read the brief introductions of the above two brands and the study situation introduction. The study scenario was designed as follows: JOYBO is a liquor brand. The beverage brand Sprite is introducing a new lemon soda in collaboration. While shopping with friends, you might see a poster advertising this product. The two groups of participants were asked to read the advertising posters presenting anthropomorphic and non-anthropomorphic contents, respectively.

4.1.3 Measures

To evaluate whether the anthropomorphism manipulation was effective, drawing on the research of Kim and McGill (2011), anthropomorphism was evaluated through three items (i.e., “I feel these brands look like two people,” “I feel these two brands seem to have free will,” and “I feel they seem to have their own intentions”). The product evaluation scale draws on the research of Morgan and Hunt (1994) and the measurement of product evaluation was gauged through a questionnaire on a 9-point scale (1 = “bad, dislike, not useful, undesirable, low-quality, unfavorable”; 9 = “good, like, useful, desirable, high-quality, favorable”) (Mukherjee and Hoyer, 2001). The purchase intention scale, informed by Dodds et al. (1991), includes five items designed in accordance with this paper’s research context (For example, “I am willing to try this co-branded product” “If I happen to see it in the store, I may buy the product” “I may actively search for the product,” etc. 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Manipulation check

The variance analysis revealed that advertisements incorporating anthropomorphic design elicited a stronger perception of anthropomorphism among viewers [Mauth = 4.61, SD = 1.12 vs. Mnonauth = 3.73, SD = 1.10; t (128) = 4.49, p < 0.001, d = 0.793]; The analysis did not reveal any substantial variation in the level of familiarity regarding Sprite [Mauth = 5.28, SD = 1.14, Mnonauth = 5.08, SD = 1.45; t (128) = 0.87, p = 0.384, d = 0.153] and JOYBO [Mauth = 4.52, SD = 1.43, Mnonauth = 4.35, SD = 1.40; t (128) = 0.68, p = 0.496, d = 0.120] between the two groups of participants. Therefore, the influence of brand familiarity on the participants’ attitudes and intentions can be eliminated. Thus, the manipulation of anthropomorphism in the study was effective.

4.2.2 Main effect test

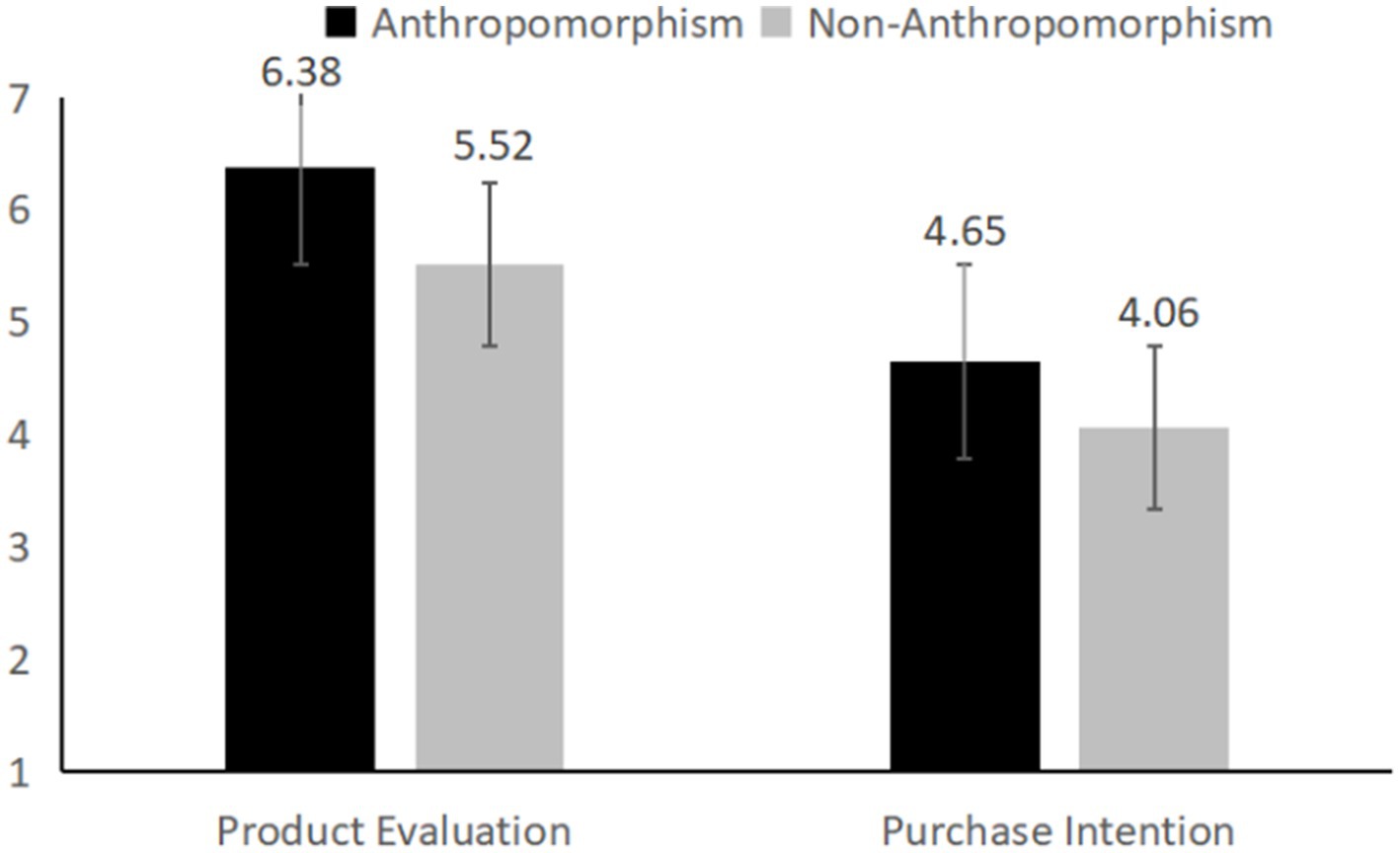

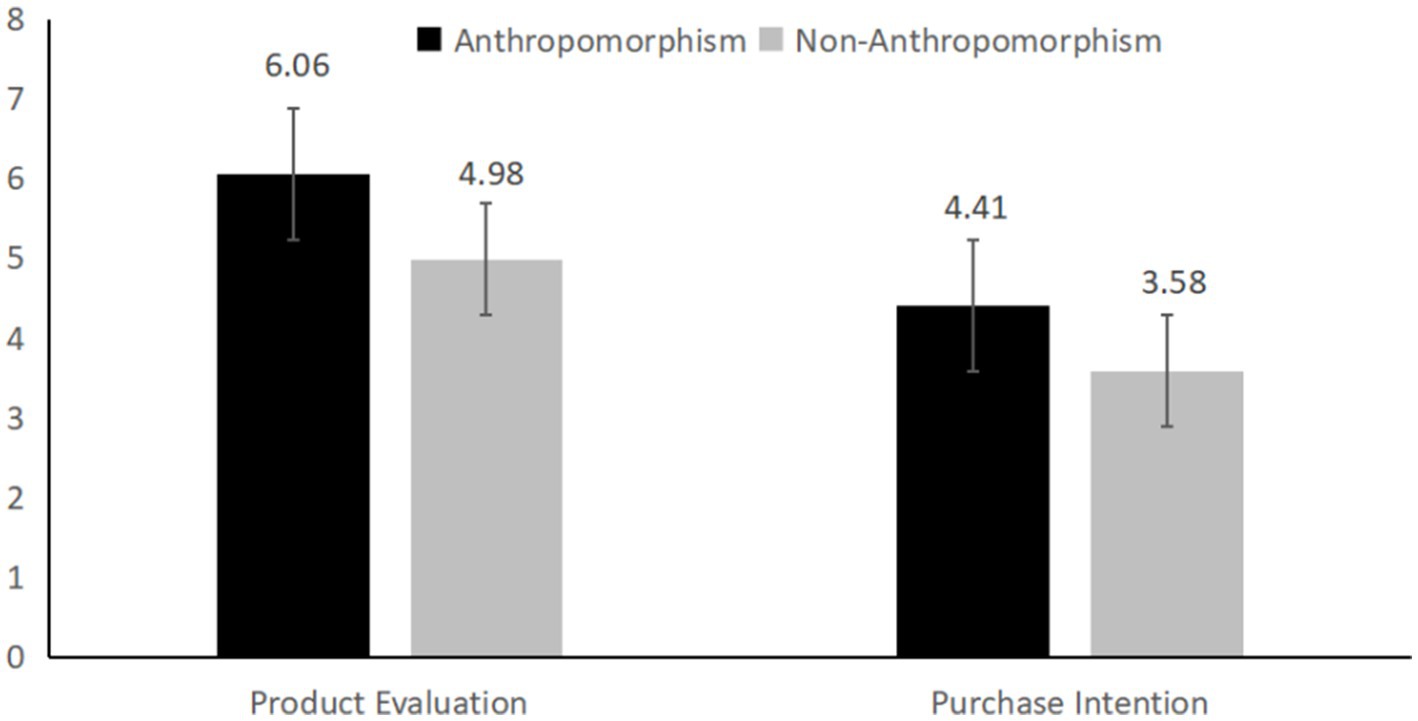

The direct effect of cobrand anthropomorphism was tested. The findings from the one-way ANOVA indicated that cobrand anthropomorphism significantly influenced product evaluation [F (1, 128) = 9.809, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.071] and purchase intention [F (1, 128) = 7.195, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.053]; the outcomes of the independent samples t-test demonstrated that compared with non-anthropomorphism, cobrand anthropomorphism could stimulate consumers to have a higher evaluation of co-branded products [Mauth = 6.38, SD = 1.09 vs. Mnonauth = 5.52, SD = 1.92, t (128) = 3.331, p < 0.01, d = 0.551] and purchase intention [Mauth = 4.65, SD = 0.96 vs. Mnonauth = 4.06, SD = 1.49, t (128) = 4.68, p < 0.001, d = 0.471]. Therefore, H1 was effectively verified. Figure 3 shows the results.

4.3 Discussion

Study 1 revealed that incorporating anthropomorphic elements in cobrands could significantly enhance consumer evaluations and intentions. This preliminary study offered foundational evidence supporting the primary effect within an authentic brand setting. To broaden the applicability of these insights, Study 2 extended the analysis to virtual brands, thereby aiming to reinforce the generalizability of the study’s conclusions.

5 Study 2: the mediating effect of narrative transportation

Study 1 used real brands for a preliminary test of the main effect. To mitigate the potential confounding effect of brand familiarity, Study 2 introduced fictional brands. This approach allowed for a deeper investigation into how co-brand anthropomorphism influences consumer evaluation and intention, as well as the mediating role of narrative transportation. In addition, prior research has indicated that mental simulation is also a critical pathway affecting consumers’ evaluation of new products (Zhao et al., 2011) and advertising persuasion (Escalas, 2004). This study also measured mental simulation and excluded its alternative explanation.

5.1 Method

5.1.1 Design

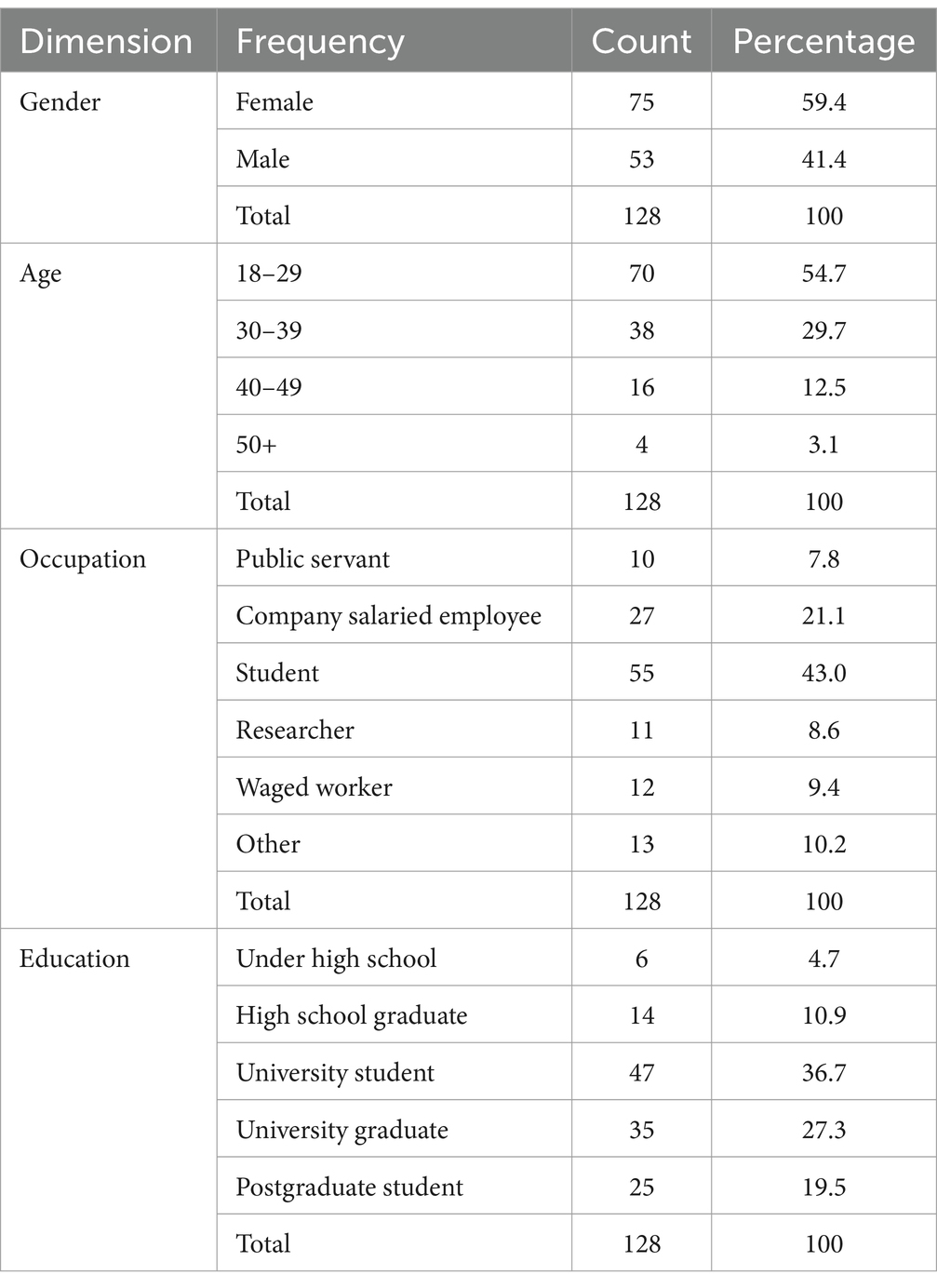

As in study 1, participants were recruited through Credamo in this study. To ensure data quality, we included attention checks and restricted participation to respondents with a high completion rate (≥95%) on the platform. Recruitment criteria included: (1) being 18 years or older, (2) owning a smartphone, and (3) having no prior knowledge of the fictional brands used in the study. The formal study employed a between-subjects design with a singular factor. A total of 128 participants (Mage = 27.35, SDage = 6.3, 40.9% male, refer to Table 2) were recruited, with 64 assigned to the anthropomorphic scenario and 64 to the non-anthropomorphic scenario.

5.1.2 Procedure

In Study 2, taking the co-branding of the mobile phone brand Huawei and the camera brand Leica as the material, the fictional mobile phone brand “ETORS” and camera brand “SEIIKY” were created for analysis (see Figure 4). During the formal study process, the participants were required to read the brief introductions of the above two fictional brands and the study situation introduction. The study scenario was designed as follows: ETORS and SEIKY, brands known for smartphones and digital cameras respectively, are jointly releasing a smartphone with enhanced multi-shot sensitivity. If you are shopping for a new smartphone, you might see this advertisement. The two groups of participants were asked to read the advertising posters presenting anthropomorphic and non-anthropomorphic contents, respectively. Finally, the participants were asked to perform a manipulation check.

5.1.3 Measures

The narrative transportation scale drew on the research of Escalas (2004) and was assessed using three items (i.e., “I feel immersed in this advertisement,” “When I think of this advertisement, I can easily describe what happened in it,” “I can imagine myself in this advertising scenario”). Following the research of Huang et al. (2020), a single item (i.e., “Your familiarity with brand ETORS/brand SEIIKY”) was used to measure brand familiarity. In addition, The scales for other key variables were consistent with Study 1 and used a 7-point Likert scale.

5.2 Results

5.2.1 Manipulation check

The ANOVA findings demonstrated that the advertising poster presenting anthropomorphic content stimulated a higher perception of anthropomorphism than that presenting non-anthropomorphic content [Mauth = 4.11, SD = 1.20, Mnonauth = 2.95, SD = 1.18; t (126) = 5.51, p < 0.001, d = 0.975]; the analysis did not reveal any significant variation in ETORS familiarity [Mauth = 2.34, SD = 1.50, Mnonauth = 2.05, SD = 1.40; t (126) = 1.051, p = 0.295, d = 0.199] and SEIKY [Mauth = 2.24, SD = 1.56, Mnonauth = 1.96, SD = 1.14; t (126) = 2.201, p = 0.147, d = 0.003] between the two groups of participants. The results of the one-sample t-test demonstrated that the brand familiarity level was situated beneath the scale’s median value [METORS = 2.18, SD = 1.45, t (127) = −14.14, p < 0.001; MSEIIKY = 2.09, SD = 1.37, t (127) = −15.69, p < 0.001, d = 0.064]. Therefore, the effect of brand familiarity on participants’ attitudes and intentions can be eliminated. Thus, the anthropomorphism operation was effective.

5.2.2 Main effect test

The one-way ANOVA findings suggested that cobrand anthropomorphism had a significant impact on product evaluation [F (1, 126) = 18.175, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.128] and purchase intention [F (1, 126) = 23.413, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.159]. The results of independent sample t-test showed that compared with non-anthropomorphism, anthropomorphism could stimulate consumers to have a higher product evaluation [Mauth = 6.06, SD = 1.28, Mnonauth = 4.98, SD = 1.52, t (126) = 4.33, p < 0.001, d = 0.769] and purchase intention [Mauth = 4.41, SD = 1.07, Mnonauth = 3.58, SD = 1.21, t (126) = 4.07, p < 0.001, d = 0.737]. Therefore, H1 was further effectively verified. Figure 5 shows the results.

5.2.3 Mediating effect test

The influence of narrative transportation as a mediator was evaluated in this study. The assessment utilized the Bootstrap method described by Hayes and Scharkow (2013), where Model 4 was selected and estimated by the Bias Corrected Bootstrap method (5,000 times). The findings indicated that narrative transportation served as a mediator in the relationship between co-brand anthropomorphism and product evaluation at the 95% confidence level (β = 0.35, SE = 0.14, CI: [0.11, 0.67]). Upon incorporating the mediating variable (narrative transportation), the direct effect of co-brand anthropomorphism on product evaluation remained significant (β = 0.73, SE = 0.24, CI: [0.26, 1.20]), suggesting that narrative transportation exerted a partial mediating influence, and H2 was verified.

Similarly, the findings revealed a significant indirect effect of cobrand anthropomorphism on purchase intention at the 95% confidence level (β = 0.36, SE = 0.14, CI: [0.12, 0.66]). When narrative transportation was controlled for, the direct effect became non-significant (β = 0.46, SE = 0.18, CI: [0.11, 0.82]), suggesting that narrative transportation partially mediated the effects of the independent variables on the outcome variables. H2 was verified.

5.2.4 Alternative explanation

This study examined the mediating role of mental simulation. The Bootstrap analysis revealed that mental simulation did not significantly mediate the relationship between co-brand anthropomorphism and product evaluation at the 95% confidence level (β = 0.07, SE = 0.09, CI: [−0.04, 0.31]). Similarly, the mediating effect on purchase intention was also non-significant at 95% confidence (β = 0.08, SE = 0.08, CI: [−0.04, 0.27]). These findings suggest that mental simulation does not provide a viable alternative explanation for the observed effects.

5.3 Discussion

In Study 2, virtual brands were utilized to extend the examination of both the primary and mediating effects within the proposed model. Specifically, cobrand anthropomorphism led to higher evaluations and intentions compared to non-anthropomorphic conditions, reinforcing its efficacy. Additionally, Study 2 confirmed the mediating role of narrative transportation, showing that cobrand anthropomorphism enhances consumer responses through this mechanism. However, it remains unclear whether these findings hold across various co-branding appeal scenarios. To address this, Study 3 was designed to explore the boundaries within which the theoretical model applies, testing its consistency under different conditions.

6 Study 3: co-branding appeal as a boundary condition

Study 3 determined to scrutinize the effect of co-branding appeal at the brand level. To achieve this goal, a between-participants study design of 2 (cobrand anthropomorphism: with vs. without) × 2 (co-branding appeal: abstract appeal vs. specific appeal) was carried out. This study selected the real brands Oreo and Hershey’s Chocolate as the focal brand and partner brand, respectively, to verify the moderating effect of co-branding appeal.

6.1 Method

6.1.1 Design

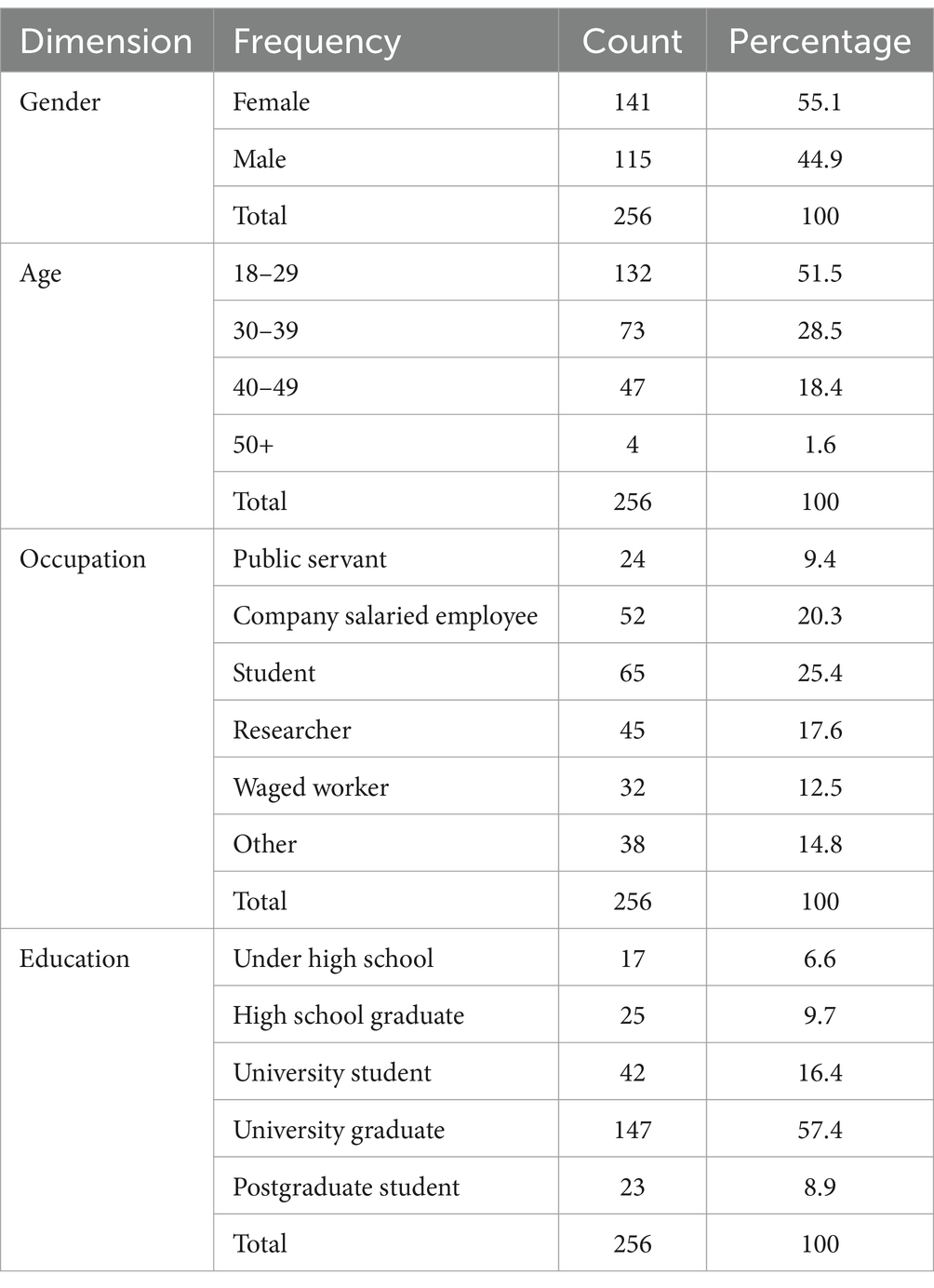

Participants were recruited through Wenjuanxing,1 a widely used online survey platform in China. To ensure data quality, we included attention checks and restricted participation to respondents with a high completion rate (≥95%) on the platform. Recruitment criteria included: (1) being 18 years or older, (2) residing in China, and (3) being familiar with co-branded food products (e.g., Oreo or Hershey’s). The formal experimental procedure adopted a between-participants design with a single factor. We recruited volunteers from the Internet to participate in the experiment. A total of 256 valid participants (Mage = 29.48, SDage = 8.68, 44.9% male, refer to Table 3) were recruited. The group subjected to abstract appeal with anthropomorphic characteristics included 64 participants, that of the abstract appeal-non-anthropomorphic group was 63, that of the specific appeal-anthropomorphic group was 67, and that of the specific appeal-non-anthropomorphic group was 62.

6.1.2 Procedure

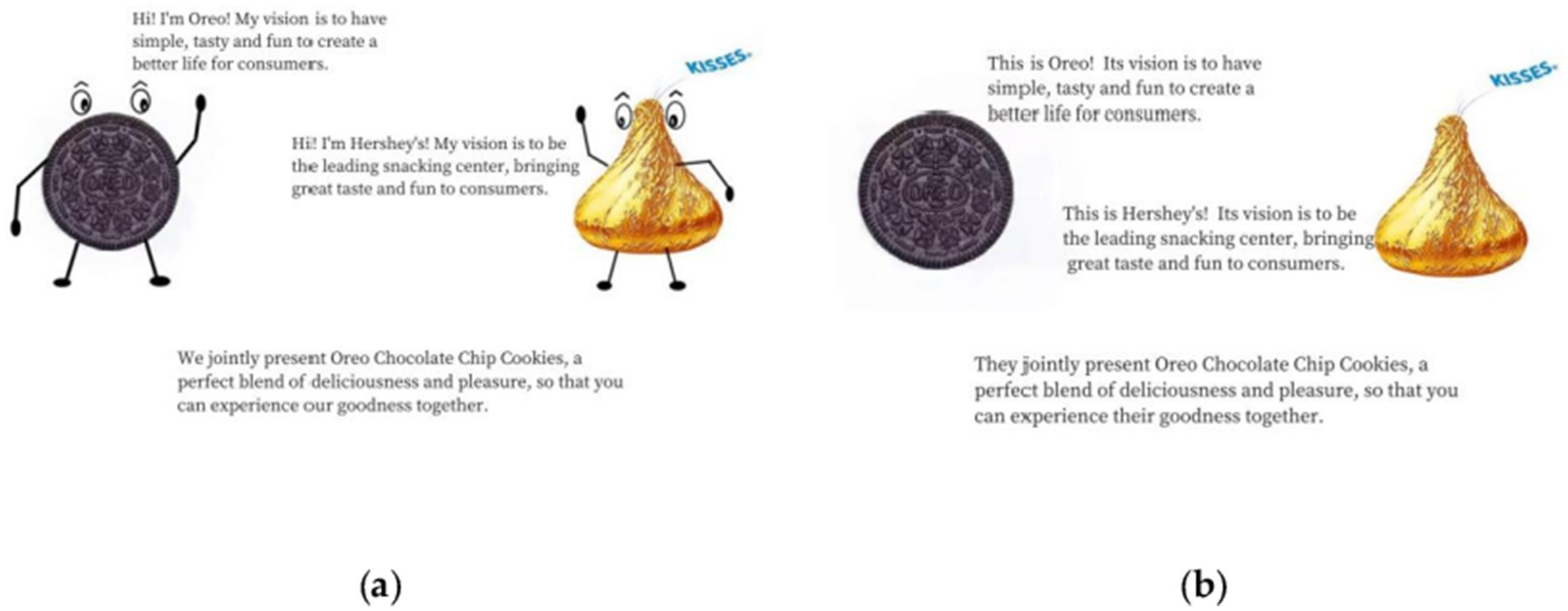

To ensure the successful manipulation of co-branding appeal and that the two brands had the same level of familiarity, a pre-test was conducted on another 58 participants. This study selected the joint marketing material of Oreo and Hershey’s Chocolate for analysis. The study scenario was designed as follows: Oreo, a famous cookie brand, and Hershey’s, a renowned chocolate brand, are collaborating on a new product launch. Suppose you need to prepare some snacks during your winter vacation travels, and it so happens that you notice the content of the product’s advertisement, browse its content and price, and find that it just meets your needs and budget.

Participants were initially presented with the study materials and tasked with evaluating both advertising appeal types individually. Pre-test analyses confirmed the successful manipulation of co-branding appeal. Participants perceived higher levels of abstractness in the abstract appeal condition compared to the specific appeal condition [Mabstract = 4.65, SD = 0.80 vs. Mspecific = 4.08, SD = 0.96; t (254) = 5.17, p < 0.01, d = 0.645]. In contrast, the specific appeal condition resulted in higher perceptions of concreteness [Mabstract = 4.64, SD = 1.32 vs. Mspecific = 4.12, SD = 1.17; t (254) = 3.31, p < 0.01, d = 0.417].

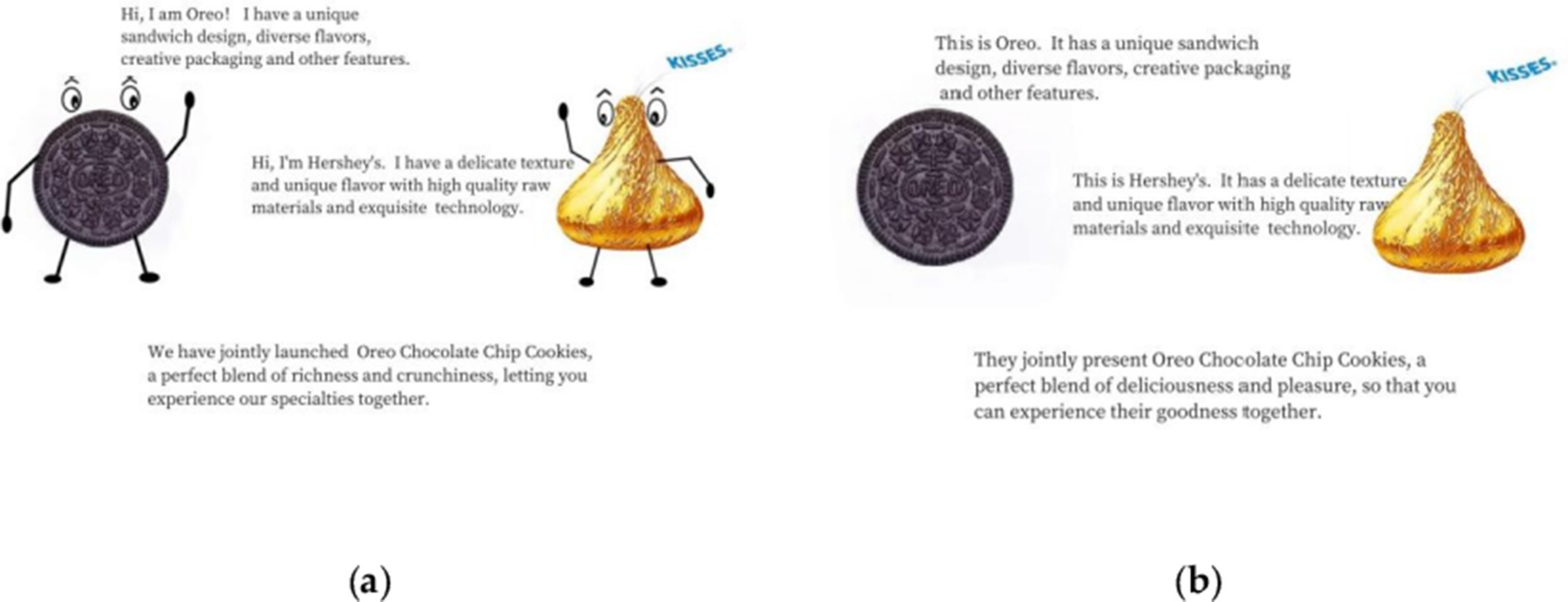

Next, the participants were shown the introductions of the two brands and a study scenario. Then, the four groups of participants were shown four advertising contents, respectively. The pictures of cobrand anthropomorphism and non-anthropomorphism manipulation under abstract/specific appeals are shown in Figures 6, 7.

Figure 6. Cobrand anthropomorphism manipulation under abstract appeal (Study 3). (a) Anthropomorphism under abstract appeal, (b) Non-anthropomorphism under abstract appeal.

Figure 7. Cobrand anthropomorphism manipulation under specific appeal (Study 3). (a) Anthropomorphism under specific appeal, (b) Non-anthropomorphism under specific appeal.

6.1.3 Measures

The manipulation of anthropomorphism, the measurement of narrative transportation, product evaluation, purchase intention, emotional state, and brand familiarity were the same as in Study 1 and Study 2. Among them, the co-branding appeal scale drew on the advertising orientation scale of Jin et al. (2021). The abstract appeal was measured by 3 items (i.e., “To what extent do you think the above advertising content is abstract?,” “When seeing this advertising content, I can easily feel that the two brands are trying to convey a certain common concept,” “When seeing this advertising content, I can feel the deep-seated information such as the values and visions that these two brands want to convey”). The specific appeal was measured by 3 items (i.e., “To what extent do you think the above advertisement is specific?,” “When seeing this advertising content, I can easily feel that the two brands are trying to convey a certain specific function or advantage,” “When seeing this advertising content, I can feel the specific details of the relevant products that these two brands want to convey”).

6.2 Results

6.2.1 Manipulation check

The results showed that the advertising picture presenting anthropomorphic content stimulated a higher perception of anthropomorphism than that presenting non-anthropomorphic content [Mauth = 4.55, SD = 1.08, Mnonauth = 3.79, SD = 1.17; t (254) = 5.35, p < 0.001, d = 0.675]; Participants showed similar levels of familiarity with Oreo [Mauth = 5.38, SD = 1.19, Mnonauth = 5.26, SD = 1.31; t (254) = 0.81, p = 0.126, d = 0.093] and Hershey’s [Mauth = 4.61, SD = 1.51, Mnonauth = 4.56, SD = 1.38; t (254) = 0.28, p = 0.061, d = 0.096] between the anthropomorphic and non-anthropomorphic groups. Therefore, the influence of brand familiarity on the participants’ attitudes and intentions could be eliminated. Thus, the manipulation of anthropomorphism in the study was effective.

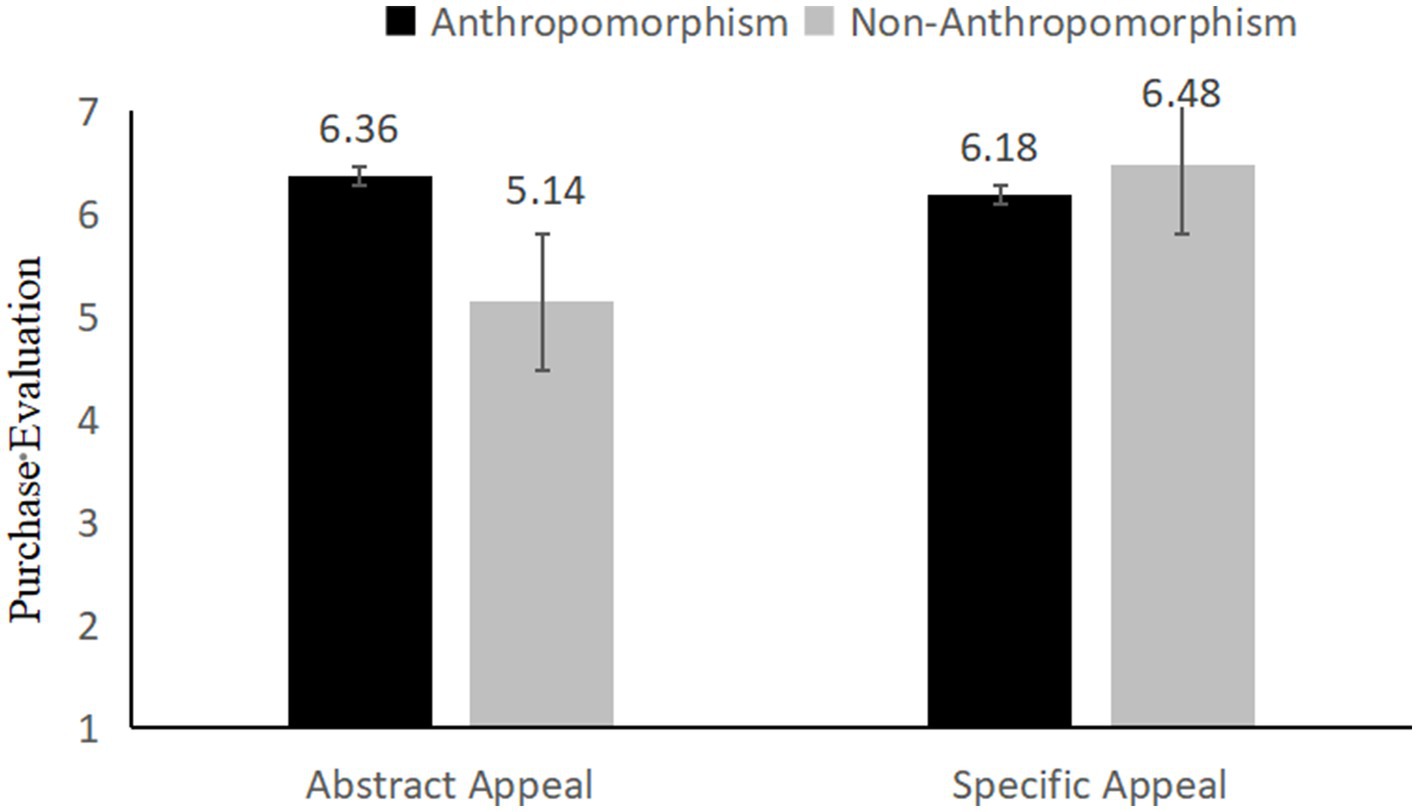

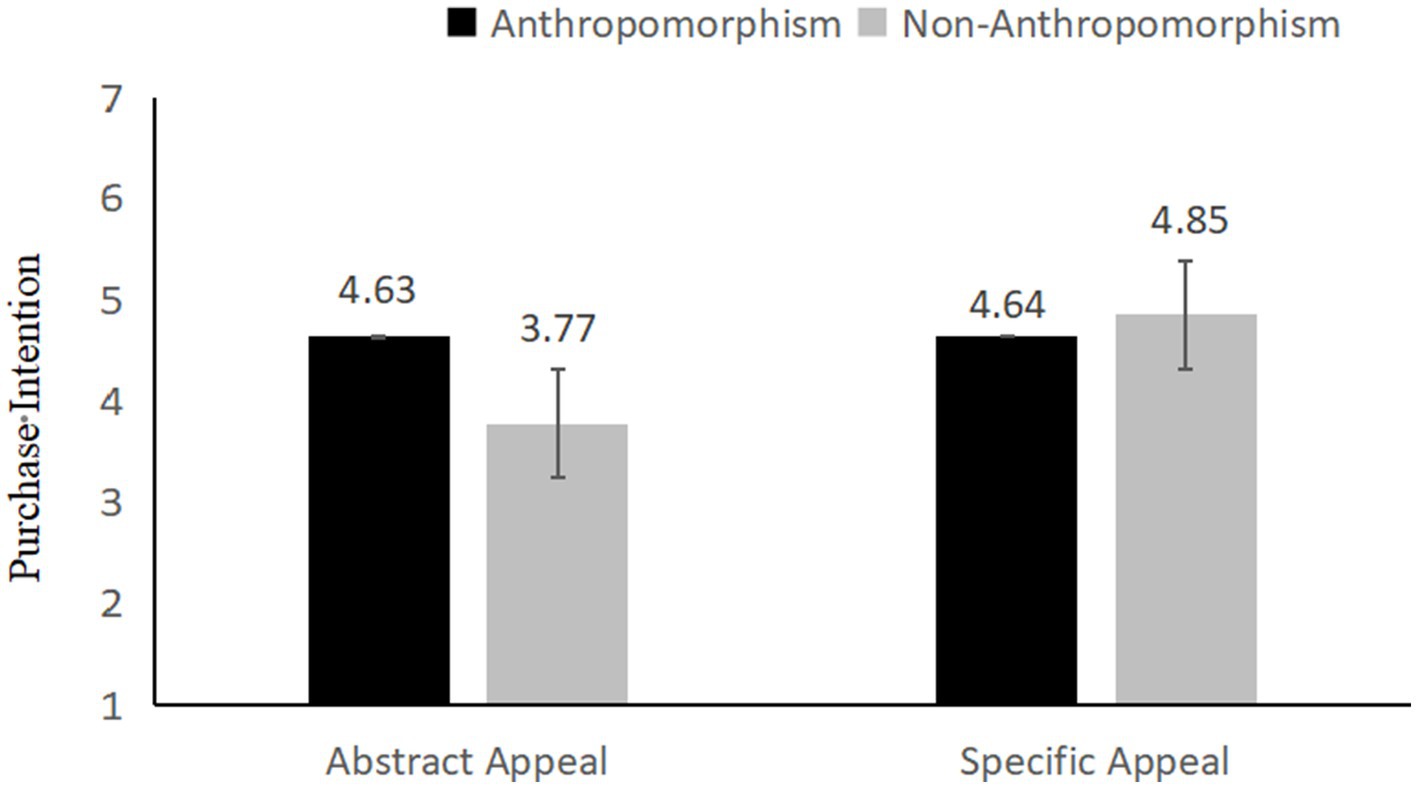

6.2.2 Main effect test

The findings from the one-way ANOVA showed that in the abstract appeal group, co-brand anthropomorphism exerted a significant influence on the evaluation [F (1, 125) = 41.418, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.107] and purchase intention [F (1, 125) = 23.076, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.095]; the independent sample t-test analysis showed that compared with non-anthropomorphism, anthropomorphism could stimulate consumers to have a higher evaluation of co-branded product [Mauth = 6.36, SD = 1.11, Mnonauth = 5.14, SD = 2.21, t (125) = 3.71, p < 0.001, d = 0.724] and purchase intention [Mauth = 4.63, SD = 0.96, Mnonauth = 3.77, SD = 1.61, t (125) = 3.51, p < 0.01, d = 0.649].

In the specific appeal group, cobrand anthropomorphism also had no significant impact on product evaluation [F (1, 127) = 1.20, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.007] and purchase intention [F (1, 127) = 0.078, p > 0.05,η2 = 0.001]. The independent sample T-test results revealed that compared with non-anthropomorphism, anthropomorphism could not stimulate consumers to have an evaluation of differences [Mauth = 6.18, SD = 1.17, Mnonauth = 6.48, SD = 1.24, t (127) = − 1.91, p > 0.05, d = 0.249]. Additionally, the impact of anthropomorphism on purchase intention was not significant [Mauth = 4.64, SD = 1.05, Mnonauth = 4.85, SD = 1.05, t (127) = −1.13, p > 0.05, d = 0.189]. Figures 8, 9 illustrate the results.

Figure 8. Interaction effect between anthropomorphism and co-branding appeal on product evaluation (Study 3).

Figure 9. Interaction effect between anthropomorphism and co-branding appeal on product intention (Study 3).

6.2.3 Moderated mediation effect test

This study examined the mediating role of narrative transportation using Hayes and Scharkow’s (2013) Bootstrap method, where Model 8 was selected and estimated by the Bias Corrected Bootstrap method (5,000 times). The analysis revealed that: in the context of abstract co-branding appeal, narrative transportation significantly mediated the effect of co-brand anthropomorphism on both product evaluation at the 95% confidence level (β = 0.51, CI = [0.18, 0.83]) and purchase intention (β = 0.39, CI = [0.15, 0.67]). Conversely, in the setting of specific co-branding appeal, narrative transportation also played a significant mediating role, but with negative effects on product evaluation (β = −0.37, CI = [−0.63, −0.11]) and purchase intention (β = −0.29, CI = [−0.53, −0.08]). These findings further substantiate the mediating effect of narrative transportation across different types of cobranding appeals.

6.3 Discussion

Study 3 expanded on previous findings by examining how co-branding appeal moderates the effectiveness of anthropomorphism. Results showed that in abstract appeals, co-brand anthropomorphism significantly enhanced product evaluation and purchase intention, whereas in specific appeals, it had no significant effect. Narrative transportation mediated these effects in both contexts, underscoring its pivotal role. Our results did not fully support the hypothesis that non-anthropomorphic strategies excel under specific appeals, possibly due to anthropomorphism’s strong main effect in abstract appeals carrying over, enhancing warmth even in functional messages. The utilitarian focus of specific appeals may have also muted expected contrasts. Additionally, the snack food context (Oreo × Hershey’s) likely favored affective responses, limiting non-anthropomorphic messaging’s advantage. These insights, discussed clarify boundary conditions and deepen theoretical understanding of anthropomorphism’s limits.

7 General discussion

7.1 Research conclusions

Based on the relevant theories of anthropomorphism and narrative transportation, this paper provided strong evidence for the effectiveness of cobrand anthropomorphism through three studies. The findings extend prior single-brand anthropomorphism research (Aggarwal and McGill, 2007; Puzakova et al., 2013) by demonstrating that humanizing co-brands amplify consumer responses through synergistic narrative effects, a mechanism absent in single-brand contexts. The essential findings include that co-brand anthropomorphism can enhance consumers’ evaluations of products and their intention to purchase more than non-anthropomorphic approaches, with narrative transportation acting as a mediator; the type of co-branding appeal plays a moderator — a result aligning with Green and Brock’s (2000) transportation theory but revealing its heightened role in multi-brand storytelling. Notably, the study contrasts with schema congruity-based explanations for co-branding success (Johan Lanseng and Erling Olsen, 2012; Estes et al., 2012), showing that narrative transportation, not just cognitive fluency, drives consumer engagement when anthropomorphism is employed. In other words, when it comes to abstract co-branding appeal, giving human-like traits to the co-brand significantly influences how products are evaluated and the intention to purchase them. In a particular appeal scenario, co-brand anthropomorphism has no significant effect on product evaluation and purchase intention. Narrative transportation mediates in both situations. The research bridges gaps between anthropomorphism theory (traditionally focused on single brands) and co-branding literature (often centered on fit or equity transfer), offering a unified framework where narrative transportation explains how humanized brand interactions create value. The research conclusions have important marketing practice implications for how brands apply anthropomorphism strategies in co-branding marketing and enhance consumers’ in-depth perception and experience.

7.2 Theoretical contributions

First, prior studies have mainly explored the influence of product function complementarity, brand image consistency, and brand attribute complementarity on consumers’ attitudes and intentions toward the main and partner brands in co-branding based on schema congruity theory (Baumgarth, 2004; Johan Lanseng and Erling Olsen, 2012; Swaminathan et al., 2015; Jian et al., 2021). While these studies have advanced our understanding of co-branding success factors, they have largely overlooked the role of brand personality and humanized interactions in shaping consumer responses. Our paper examined how cobrand anthropomorphism affects consumer perception, evaluation, and willingness toward co-branded products, thereby extending the co-branding literature beyond static fit dimensions to dynamic, relationship-driven mechanisms (He et al., 2018; Han et al., 2023). This contributes to the understanding of factors leading to successful co-brandings from a consumer perspective and bridges the gap between single-brand anthropomorphism research (Aggarwal and McGill, 2007; Zhang and Wang, 2023) and multi-brand contexts.

Second, this study contributed to the literature on the psychological motivation and related mechanisms of cobrand anthropomorphism satisfaction. Prior research has demonstrated that brand anthropomorphism positively influences perceived fluency and brand ability (Johan Lanseng and Erling Olsen, 2012; Estes et al., 2012), yet these studies primarily focused on single-brand scenarios (Puzakova et al., 2013; Kim and Swaminathan, 2021). Moreover, while the importance of partner selection in co-branding is well-documented (Geylani et al., 2008), little attention has been paid to how anthropomorphism alters consumers’ interpretation of the co-branding relationship. This study showed that co-branding anthropomorphism could enhance the effect of co-branding marketing, not through traditional cognitive fluency pathways but through the narrative transportation mechanism (Green and Brock, 2000; Van Laer et al., 2019). By immersing consumers in a humanized brand story, anthropomorphism fosters emotional engagement and self-referencing (Debevec and Romeo, 1992; Escalas, 2004), thereby offering a novel explanatory framework for co-branding effectiveness that complements schema congruity theory.

Finally, this study proposed and verified the moderating effect of different types of co-branding appeals on the effect of cobrand anthropomorphism. Previous studies have emphasized that fit, congruence, and consistency are critical to co-branding success (Huang, 2017; Górska-Warsewicz, 2024), yet they seldom addressed how message framing interacts with anthropomorphism strategies. This study identified co-branding appeal as an important boundary condition and empirically demonstrated that abstract appeals (e.g., value-based narratives) synergize with anthropomorphism by leveraging interpersonal connection mechanisms (Guido and Peluso, 2015), whereas specific appeals (e.g., functional benefits) diminish its impact by shifting focus to utilitarian evaluations (Hornik et al., 2017). This finding extends the anthropomorphism literature by contextualizing its effectiveness within the co-branding appeal framework (Xiao and Lee, 2024) and provides actionable insights for marketers designing collaborative campaigns.

7.3 Practical contributions

First, within the realm of co-branding marketing practices, given the focus on the complementarity of product functions and the consistency of brand images, marketers are required to carry out a set of coordinated anthropomorphic communication tactics in line with the properties and features of each brand involved in the co-branding initiative. Marketers can use the anthropomorphism strategy to highlight the interactive behavior between brands, and make consumers generate emotions such as identification, trust, care, and mutual attachment. For example, in the case of a luxury fashion brand collaborating with a tech company, marketers could design anthropomorphic roles where the fashion brand embodies elegance and heritage, while the tech brand represents innovation and precision. Their interaction could be portrayed as a “dialogue” between tradition and futurism, reinforcing the complementary strengths of both brands. Marketers can choose appropriate anthropomorphic roles, create a brand anthropomorphic image exclusive to the enterprise, and integrate the anthropomorphic image into advertising, product packaging, shape, etc., creating a unique and inimitable popularity attribute, improving consumers’ preference for the cobrands.

Second, marketers can endow products with emotional value by telling brand stories and making consumers resonate. Marketers can create novel joint stories and theme contents to interpret the anthropomorphic brand image and its implied quasi-interpersonal relationship, combine brand characteristics and storylines, and make consumers regard the co-branding as an interpersonal interaction context full of emotions and stories, thus creating an emotional connection between consumers and the cobrands, shaping unique co-branded products. In addition, the core of the anthropomorphism strategy is to establish a closer emotional connection with consumers by endowing brands or products with human traits and emotions. Thus, brand managers should concentrate on strengthening the emotional connection with consumers. They can enhance the personality of brands or products through creative design, thereby encouraging consumers to resonate and emotionally identify with them. For example, a children’s product co-branding (e.g., Disney × LEGO) could adopt playful, friendly anthropomorphic characters (e.g., Mickey Mouse and a LEGO figure building adventures together) to evoke nostalgia and joy in both parents and children. As a result, it enhances positive evaluation of the product and the intention to purchase.

Third, when formulating joint marketing strategies, marketers should fully consider consumers’ perception of the co-branding appeal of both parties, reasonably extract, evaluate, and align the traits of the focal brand with the partner brand, better understand the relationship between the brands, and make a reasonable alliance according to their respective advantages. Brand marketers should clarify the type of joint story appeal of themselves and their partners, whether it is abstract or specific. For abstract appeals (e.g., sustainability collaborations like Patagonia × Starbucks), anthropomorphism could focus on shared values (e.g., “Earth Guardians” persona) to emphasize ethical alignment. For functional appeals (e.g., GoPro × Red Bull’s adventure-driven campaigns), anthropomorphism should highlight action-oriented traits (e.g., “Thrill-Seeking Duo”). According to different types of story appeals, brand marketers should timely display the deep-seated information such as the value concept and cultural perspective that the brand wants to convey; but in the context of abstract co-branding appeal, it is necessary to focus on showing the functional characteristics, innovative attributes, etc. of the product that reflect the specific expected benefits for consumers.

7.4 Research limitations and prospects

To begin with, past studies suggest that anthropomorphism does not always have beneficial effects and might negatively impact brand image (Puzakova et al., 2013). Brand collaboration is a strategy between companies that can lead to both positive and negative spillover effects. Nonetheless, our research did not examine the outcomes of this phenomenon from the reverse viewpoint. Further studies can uncover the dual impacts of brand cooperation anthropomorphism and offer more practical advice for businesses. Secondly, earlier studies primarily investigated the marketing impact of brand anthropomorphism via the cognitive fluency mechanism, whereas this research empirically confirmed the influence of cobrand anthropomorphism and narrative transportation. Thus, future research can conduct a comparative analysis. This paper focused on the use and mechanism of anthropomorphism in linking two brands instead of multiple brands (three or more). For complex brand alliances, anthropomorphism may influence consumers’ perceptions of brand group identity and their attitudes toward co-branded products. Future research should explore these psychological impacts to understand the effects of anthropomorphism on consumer behavior. Finally, it is important to acknowledge that the sample populations across the three studies were predominantly composed of young adults, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader demographic groups. Future research should incorporate more heterogeneous samples to validate the robustness of the results and enhance their applicability across different consumer segments.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LY: Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. YW: Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation Youth Program (ZR2023QG069), Social Science Research Planning Project of Linyi, Shandong Province (2025LX376) and Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation General Program (ZR2022MG021).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^www.wjx.cn

References

Aaker, J. L. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality. J. Mark. Res. 34, 347–356. doi: 10.1177/002224379703400304

Aggarwal, P., and McGill, A. L. (2007). Is that car smiling at me? Schema congruity as a basis for evaluating anthropomorphized products. J. Consum. Res. 34, 468–479. doi: 10.1086/518544

Baumgarth, C. (2004). Evaluations of co-brands and spill-over effects: further empirical results. J. Mark. Commun. 10, 115–131. doi: 10.1080/13527260410001693802

Besharat, A., and Langan, R. (2014). Towards the formation of consensus in the domain of co-branding: current findings and future priorities. J. Brand Manag. 21, 112–132. doi: 10.1057/bm.2013.25

Brechman, J. M., and Purvis, S. C. (2015). Narrative, transportation and advertising. Int. J. Advert. 34, 366–381. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2014.994803

Chen, Z., and Yang, G. (2017). Which anthropomorphic brand image will bring greater favorability? The moderation effect of need to belong. Nankai. Bus. Rev. 20, 135–143. (in Chinese)

Chronis, A. (2008). Co-constructing the narrative experience: staging and consuming the American civil war at Gettysburg. J. Mark. Manag. 24, 5–27. doi: 10.1362/026725708X273894

Chu, K., Lee, D. H., and Kim, J. Y. (2019). The effect of verbal brand personification on consumer evaluation in advertising: internal and external personification. J. Bus. Res. 99, 472–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.11.004

Cohen, R. J. (2014). Brand personification: introduction and overview. Psychol. Mark. 31, 1–30. doi: 10.1002/mar.20671

De Chernatony, L., Cottam, S., and Segal-Horn, S. (2006). Communicating services brands’ values internally and externally. Serv. Ind. J. 26, 819–836. doi: 10.1080/02642060601011616

Debevec, K., and Romeo, J. B. (1992). Self-referent processing in perceptions of verbal and visual commercial information. J. Consum. Psychol. 1, 83–102. doi: 10.1016/S1057-7408(08)80046-0

Delbaere, M., McQuarrie, E. F., and Phillips, B. J. (2011). Personification in advertising. J. Advert. 40, 121–130. doi: 10.2753/JOA0091-3367400108

Dodds, W. B., Monroe, K. B., and Grewal, D. (1991). Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 28, 307–319. doi: 10.1177/002224379102800305

Escalas, J. E. (2004). Narrative processing: building consumer connections to brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 14, 168–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327663jcp1401&2_19

Estes, Z., Gibbert, M., Guest, D., and Mazursky, D. (2012). A dual-process model of brand extension: taxonomic feature-based and thematic relation-based similarity independently drive brand extension evaluation. J. Consum. Psychol. 22, 86–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2011.11.002

Fein, S. (1996). Effects of suspicion on attributional thinking and the correspondence bias. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 1164–1184. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1164

Geylani, T., Inman, J. J., and Hofstede, F. T. (2008). Image reinforcement or impairment: the effects of co-branding on attribute uncertainty. Mark. Sci. 27, 730–744. doi: 10.1287/mksc.1070.0326

Górska-Warsewicz, H. (2024). Relationship between entrepreneurial orientation, innovative co-branding partnership, and business performance. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 20, 139–159. doi: 10.7341/20242027

Green, M. C., and Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 79, 701–721. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701

Guido, G., and Peluso, A. M. (2015). Brand anthropomorphism: conceptualization, measurement, and impact on brand personality and loyalty. J. Brand Manag. 22, 1–19. doi: 10.1057/bm.2014.40

Han, J., Wang, D., and Yang, Z. (2023). Acting like an interpersonal relationship: Cobrand anthropomorphism increases product evaluation and purchase intention. J. Bus. Res. 167:114194. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114194

Hayes, A. F., and Scharkow, M. (2013). The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: does method really matter? Psychol. Sci. 24, 1918–1927. doi: 10.1177/0956797613480187

He, D., Chen, F., and Jiang, Y. (2018). How do consumers react to anthropomorphized brand alliance? Applying interpersonal expectations to business-to-business relationships. Adv. Consum. Res. 57, 305–318.

Hornik, J., Ofir, C., and Rachamim, M. (2017). Advertising appeals, moderators, and impact on persuasion: a quantitative assessment creates a hierarchy of appeals. J. Advert. Res. 57, 305–318. doi: 10.2501/JAR-2017-017

Huang, J. (2017). The effect of crossover marketing on value creation in Mobile internet environment. Chin. J. Manag. 14, 1052–1061. (in Chinese)

Huang, F., Wong, V. C., and Wan, E. W. (2020). The influence of product anthropomorphism on comparative judgment. J. Consum. Res. 46, 936–955. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucz028

Hur, J. D., Koo, M., and Hofmann, W. (2015). When temptations come alive: how anthropomorphism undermines self-control. J. Consum. Res. 42, ucv017–ucv358. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucv017

Jian, Y., Zhu, L., and Zhou, Z. (2021). The mechanism of brand alliance attitude towards cross-boundary co-development: based on the perspective of consumer inspiration theory. Nankai. Bus. Rev. 24, 25–38. (in Chinese)

Jin, X., Huang, E., and Xu, W. (2021). Influence of the matching effect between social crowding and advertising-oriented on consumer attitudes towards products. J. Northeastern. Univ. (Soc Sci). 23, 40–46. doi: 10.15936/j.cnki.1008-3758.2021.06.006

Johan Lanseng, E., and Erling Olsen, L. (2012). Brand alliances: the role of brand concept consistency. Eur. J. Mark. 46, 1108–1126. doi: 10.1108/03090561211247874

Kim, S., and McGill, A. L. (2011). Gaming with Mr. slot or gaming the slot machine? Power, anthropomorphism, and risk perception. J. Consum. Res. 38, 94–107. doi: 10.1086/658148

Kim, J., and Swaminathan, S. (2021). Time to say goodbye: the impact of anthropomorphism on selling prices of used products. J. Bus. Res. 126, 78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.046

Lafferty, B. A., Goldsmith, R. E., and Hult, G. T. M. (2004). The impact of the alliance on the partners: a look at cause–brand alliances. Psychol. Mark. 21, 509–531. doi: 10.1002/mar.20017

Lamberton, C., and Stephen, A. T. (2016). A thematic exploration of digital, social media, and mobile marketing: research evolution from 2000 to 2015 and an agenda for future inquiry. J. Mark. 80, 146–172. doi: 10.1509/jm.15.0415

Morgan, R. M., and Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 58, 20–38. doi: 10.1177/002224299405800302

Mukherjee, A., and Hoyer, W. D. (2001). The effect of novel attributes on product evaluation. J. Consum. Res. 28, 462–472. doi: 10.1086/323733

Nguyen, H. T., Ross, W. T. Jr., Pancras, J., and Phan, H. V. (2020). Market-based drivers of cobranding success. J. Bus. Res. 115, 122–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.04.046

Puzakova, M., Kwak, H., and Rocereto, J. F. (2013). When humanizing brands goes wrong: the detrimental effect of brand anthropomorphization amid product wrongdoings. J. Mark. 77, 81–100. doi: 10.1509/jm.11.0510

Qin, H., Xie, Z., Ding, C., Wang, J., and Xu, Y. (2024). Healing or hesitation? The impact of anthropomorphism on consumers' repair intentions for products. J. Consum. Res. 79:103805. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2024.103805

Rajagopal, P., and Burnkrant, R. E. (2009). Consumer evaluations of hybrid products. J. Consum. Res. 36, 232–241. doi: 10.1086/596721

Shen, F., Ahern, L., and Baker, M. (2014). Stories that count: influence of news narratives on issue attitudes. J. Mass Commun. Q. 91, 98–117. doi: 10.1177/1077699013514414

Swaminathan, V., Gürhan-Canli, Z., Kubat, U., and Hayran, C. (2015). How, when, and why do attribute-complementary versus attribute-similar cobrands affect brand evaluations: a concept combination perspective. J. Consum. Res. 42, 45–58. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucv006

Thomas, V. L., and Grigsby, J. L. (2024). Narrative transportation: a systematic literature review and future research agenda. Psychol. Mark. 41, 1805–1819. doi: 10.1002/mar.22011

Tsao, J. (1996). Compensatory media use: an exploration of two paradigms. Commun. Stud. 47, 89–109. doi: 10.1080/10510979609368466

Van Laer, T., Feiereisen, S., and Visconti, L. M. (2019). Storytelling in the digital era: a meta-analysis of relevant moderators of the narrative transportation effect. J. Bus. Res. 96, 135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.053

Washburn, J. H., Till, B. D., and Priluck, R. (2000). Co-branding: brand equity and trial effects. J. Consum. Mark. 17, 591–604. doi: 10.1108/07363760010357796

Xiao, N., and Lee, S. H. M. (2024). Brand identity fit in co-branding: the moderating role of CB identification and consumer coping. Eur. J. Mark. 48, 1239–1254. doi: 10.1108/EJM-02-2012-0075

Xu, S., Zhang, X., Kim, R., and Su, M. (2024). Anthropomorphic last-mile robots and consumer intention: an empirical test under a theoretical framework. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 81:104028. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2024.104028

Xu, L., Zhao, S., Cui, N., Zhang, L., and Zhao, J. (2020). The impact of story design mode on Consumers' brand attitude. J. Manag. World. 36, 76–95. (in Chinese)

Zhang, Y., and Wang, S. (2023). The influence of anthropomorphic appearance of artificial intelligence products on consumer behavior and brand evaluation under different product types. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 74:103432. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103432

Zhao, M., Hoeffler, S., and Zauberman, G. (2011). Mental simulation and product evaluation: the affective and cognitive dimensions of process versus outcome simulation. J. Mark. Res. 48, 827–839. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.48.5.827

Keywords: cobrand anthropomorphism, narrative transportation, co-branding appeal, product evaluation, brand collaboration

Citation: Han J, Yun L and Wang Y (2025) Immersed in our narratives: a study of the effectiveness of cobrand anthropomorphism. Front. Commun. 10:1602833. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1602833

Edited by:

Tereza Semerádová, Technical University of Liberec, CzechiaReviewed by:

Wenfang Fan, Chongqing University, ChinaWidarto Rachbini, Universitas Pancasila, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Han, Yun and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yaming Wang, aXNhYmVsbGFfc3dhbjEzMTRAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Jie Han1

Jie Han1 Yaming Wang

Yaming Wang