- Department of Media and Business Communication, Institute Human-Computer-Media, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany

Companies that are family-owned consciously use their family background in marketing communications. Nevertheless, the cause-and-effect mechanisms in the processing of such communication have not yet been investigated. In a two-level between-subjects experiment, we examined the influence of brand origin (family vs. non-family business) on brand credibility and consumers' purchase intention. The results show that brands from family businesses are perceived as more sincere and reliable and, consequently, more credible than brands from non-family businesses. This has a positive effect on attitude toward the brand and increases consumers' purchase intention. The study's findings have valuable implications for research and practice.

1 Introduction

Family businesses can play a decisive role in the corporate landscape of a country (Miroshnychenko et al., 2020). In Germany, for example, they account for over 90 percent of all companies (Stiftung Familienunternehmen, 2007). The family as a source of identity has a significant influence on the strategy and management of the company (Chua et al., 1999) and is characterized by a consistent value system, tradition or long-term orientation (Baumgartner, 2009; Buß, 2006; Diez, 2006; Hirmer, 2015) compared to non-family businesses. This suggests that family businesses have a high marketing potential, but so far, little research has been done on the effectiveness of this potential (Benavides-Velasco et al., 2013; Kashmiri and Mahajan, 2010; Reuber and Fischer, 2011; Rovelli et al., 2022). Content analyses of family business websites suggest that only about half communicate their status as a family business (Botero et al., 2013), with tradition being the most common aspect emphasized (Micelotta and Raynard, 2011). Surveys using correlative data show that family businesses are associated with a certain tradition, a manageable company size and trustworthiness (Binz and Smit, 2013; Botero et al., 2018) as well as attributes such as honest, dedicated, responsible or long-term oriented (Koiranen, 2002; Zellweger et al., 2012). Presumed effects, which, to our knowledge, have not yet been experimentally tested, are that family businesses, compared to non-family businesses, could be perceived as more authentic brands (Lude and Prügl, 2018; Zanon et al., 2019), that are trusted more (Beck and Prügl, 2018; Gallucci et al., 2015), that are more likely to be recommended (Sageder et al., 2015) and evoke a stronger purchase intention or even purchase decision among consumers (Beck and Kenning, 2015; Binz et al., 2013; Craig et al., 2008; Jaufenthaler et al., 2025) and lead to higher customer satisfaction (Schellong et al., 2019). In addition, a match between the name of the family that owns the company and the name of the company (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz, 2013; Kashmiri and Mahajan, 2010) should be beneficial for the company's performance and reputation.

An initial study comparing family businesses and non-family businesses in a kind of experimental setting suggests that family businesses may be rated higher than non-family businesses in terms of service, trust in employees, problem-solving orientation, and customer satisfaction. The results should be viewed with caution, however, because in this study, the manipulation was created using only two different text vignettes about a supposed new grocery store that will be locating in town next fall. The test subjects were not shown anything visual, and the type of text vignette seemed very unusual or artificial and therefore did not correspond to any externally valid scenario. In addition, all dependent variables were queried with regard to the store, not with regard to the brand of the family business (Orth and Green, 2009).

In view of the current state of research, it can be concluded that the cause-and-effect mechanisms in the processing of genuine advertising communication by family businesses vs. non-family businesses have not yet been investigated. Which aspects of communication make a difference in the perception of the brand? On what dimensions is the brand of a family business perceived differently from a comparable brand of a non-family-business, and what psychological processes subsequently influence the evaluation of this brand and the intention to purchase products from this brand? One possible central construct for explaining the positive effects of brands in family ownership is brand credibility, since this can provide consumers with an important point of orientation in the flood of offers (e.g., Eisend, 2003). The effect of brand credibility in connection with family businesses has not yet been investigated. Therefore, the aim of this experimental study was to make an important contribution to the expansion of the research field and to examine whether and why family businesses can claim an advantage in brand credibility compared to non-family businesses and what the resulting consequences are.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Family businesses and brand personality

A brand is an image firmly anchored in the minds of consumers and is composed of associations (Esch, 2005). Aaker (1997) defines brand personality as the totality of human characteristics associated with a brand. Empirically determined brand personality dimensions are sincerity, excitement, competence, sophistication, and ruggedness, which can be subdivided into further facets and characteristics (Aaker, 1997). In the case of family businesses that actively communicate their brand origin in the sense of their organizational origin, the brand personality is strongly influenced by family associations (Hirmer, 2015; Klein, 2010; Wielsma and Brunninge, 2019). In the literature, “family” is generally associated with characteristics such as sincerity (Opielka, 2001), down-to-earthness (Baus, 2013), or honesty (Dreysse, 2015). These family-related associations are best reflected in the dimension of sincerity of the brand personality inventory according to Aaker (1997). Furthermore, “family” is associated with reliability (Grundmann and Wernberger, 2014), which, as a facet of the competence dimension, is also part of the brand personality according to Aaker (1997). Therefore, we were able to plausibly derive the following hypotheses about the personality of family businesses from the overlap of family-related associations and Aaker's brand personality inventory:

Hypothesis 1a: The personality of a brand of a family business is perceived as more sincere than the personality of a brand of a comparable non-family business.

Hypothesis 1b: The personality of a brand of a family business is perceived as more reliable than the personality of a brand of a comparable non-family business.

2.2 Brand credibility

A company's advertising efforts across a wide range of channels bombard consumers with countless bits of information designed to persuade them to buy a product or service. In this flood of offers, it is hardly possible to get in touch with the origin of an advertising message and check information for its truthfulness yourself. In this case, consumers often base their decisions on the credibility of the company and its brands (Eisend, 2003; Erdem et al., 2002). Erdem and Swait (2004) define brand credibility as the credibility of the product information contained in a brand, through which consumers attribute the ability and the will to the brand to keep its promises. This credibility is based on the sub-dimensions of competence and trustworthiness: a competent brand is a brand that is fundamentally capable of keeping its promises (Erdem and Swait, 1998). A trustworthy brand, on the other hand, stands for providing the added value and quality it promises at a consistent level (Ballester and Alleman, 2005). When these two sub-dimensions work together, a brand appears credible in the eyes of consumers, according to Erdem and Swait (1998). A number of studies in communication science have shown that both the sincerity (Bekk and Spörrle, 2010; Grace and Furuoka, 2007; Jin and Sung, 2008, 2009; Kyung et al., 2010; Salwen, 1987) as well as reliability (Jin and Sung, 2008, 2009; Kyung et al., 2010) play an important role in the constitution of credibility. Although the findings relate to source credibility (Hovland and Weiss, 1951), it is assumed that the findings can be transferred due to the close definition to the construct of brand credibility (Erdem and Swait, 2004), from which the following hypotheses arise:

Hypothesis 2a: The stronger the perceived sincerity of the brand, the higher the brand credibility.

Hypothesis 2b: The stronger the perceived reliability of the brand, the higher the brand credibility.

2.3 Brand attitude and purchase intention

Attitudes toward a brand are described as an individual's internal evaluation of a brand (Mitchell and Olson, 1981). It has been shown that this can be positively influenced by increased brand credibility (e.g., Anridho and Liao, 2013; Sheeraz et al., 2016). In the context of marketing, attitudes toward the brand are particularly important because they can trigger active behavior, such as a purchase or a recommendation (Spears and Singh, 2004). It has been shown that increased brand credibility also has a positive effect on purchase intention as a conscious plan of an individual to make an effort to acquire a brand (Kemp and Bui, 2011; Laksamana, 2016; Li et al., 2011; Sheeraz et al., 2012, 2016; Wang and Yang, 2010, 2011). We also assume these positive effects in the context of brands of family businesses:

Hypothesis 3a: The higher the brand credibility, the stronger the positive attitude toward the brand.

Hypothesis 3b: The higher the brand credibility, the stronger the intention to buy the brand.

When we consider the hypotheses presented so far together, the following four serial mediation hypotheses emerge as a consequence:

Hypothesis 4a: The stronger positive attitude toward the brand of a family business compared to a comparable non-family business is mediated by the perceived sincerity of the brand and the brand credibility.

Hypothesis 4b: The stronger positive attitude toward the brand of a family business compared to a comparable non-family business is mediated by the perceived reliability of the brand and the brand credibility.

Hypothesis 5a: The stronger intention to buy the brand of a family business compared to a comparable non-family business is mediated by the perceived sincerity of the brand and the brand credibility.

Hypothesis 5b: The stronger intention to buy the brand of a family business compared to a comparable non-family business is mediated by the perceived reliability of the brand and the brand credibility.

3 Method

3.1 Design and stimulus

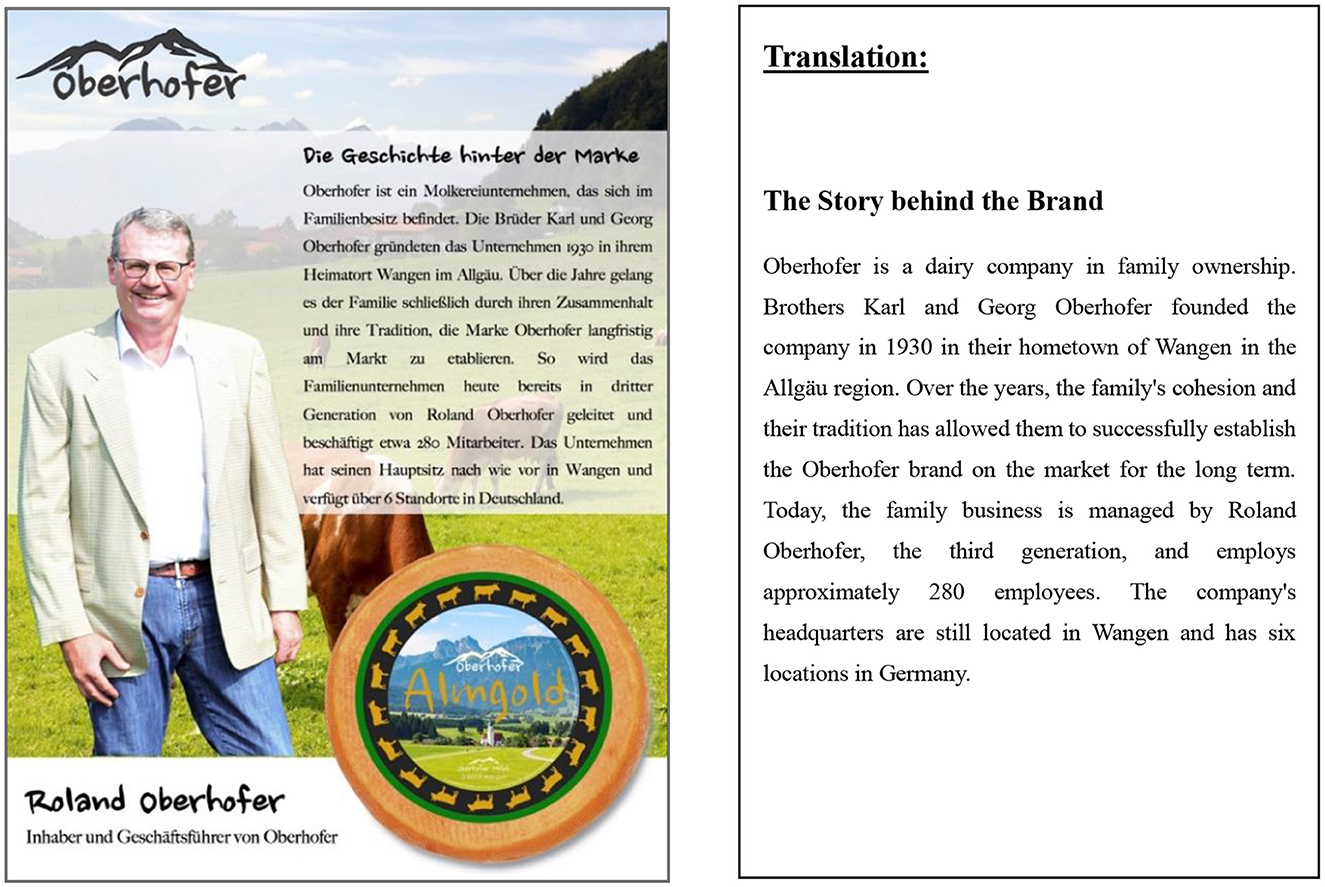

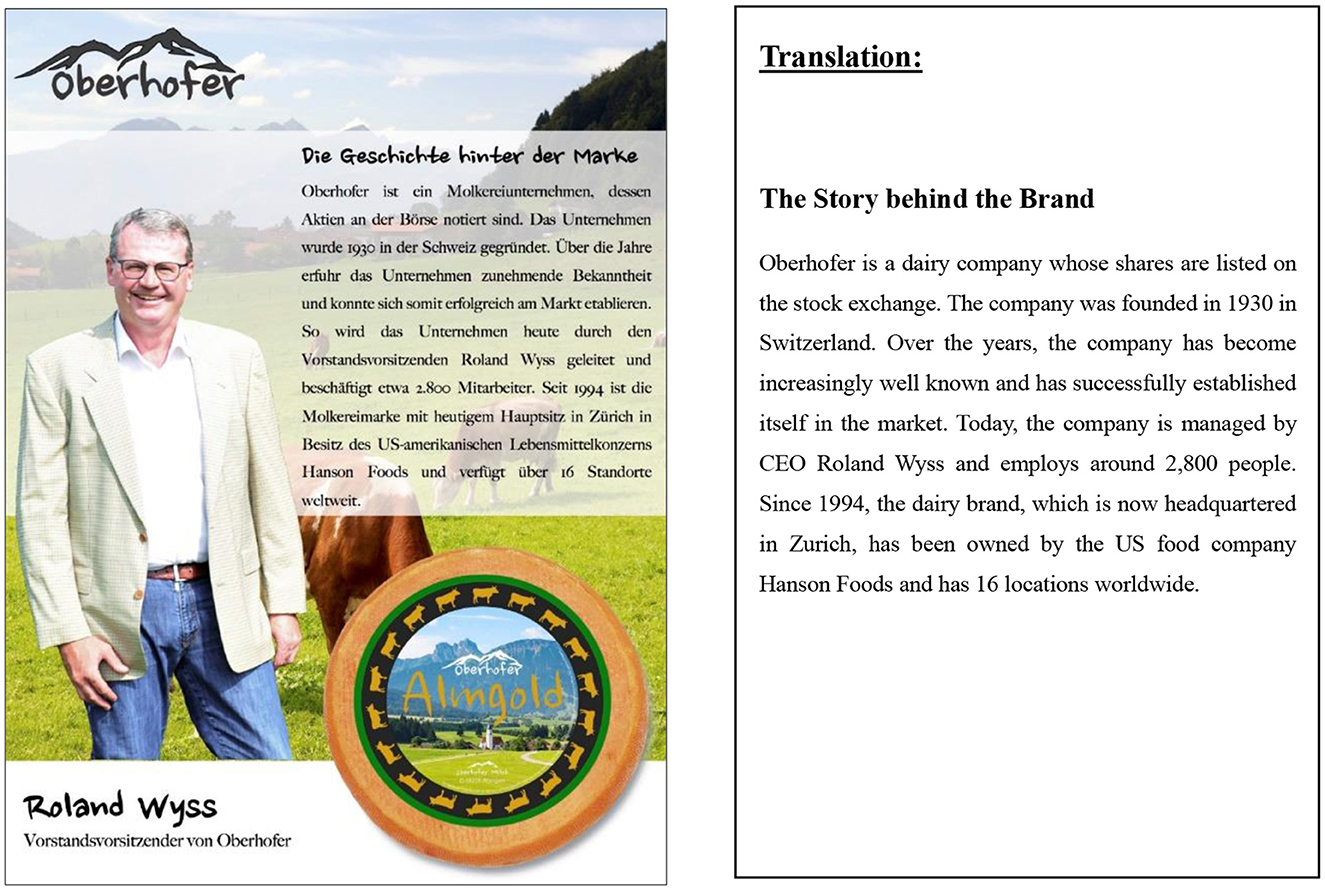

The study was conducted in Germany as an online experiment in a two-level between-subjects design with brand origin (family business vs. non-family business) as the experimentally manipulated factor. An advertisement for the fictitious dairy brand Oberhofer was used as a stimulus. The brand origin was changed in the form of the sender (Figures 1, 2). Dairy products were chosen as a product category that is presumably relevant for a large part of the population, regardless of age, gender and income. It could be assumed that there was a general willingness to buy across the entire sample.

Figure 1. Advertisement of a family business. The background with the alpine pasture and cow, the cheese, the mountain silhouette in the Oberhofer logo, and the mountain landscape and vectorized cows on the round cheese label were reproduced from pixabay.com, with permission.

Figure 2. Advertisement of a non-family business. The background with the alpine pasture and cow, the cheese, the mountain silhouette in the Oberhofer logo, and the mountain landscape and vectorized cows on the round cheese label were reproduced from pixabay.com, with permission.

Both advertisements were designed as corporate advertisements showing the brand logo, a cheese wheel as an example of the product, a company representative with their name and position, and a company biography. The origin of the advertisement was manipulated using characteristic differentiating features from the literature: In the condition family business, the brand and surname of the company representative match, analogous to the naming of the majority of family businesses (Kashmiri and Mahajan, 2010), whereas the representative of the non-family business bears the Swiss surname Wyss, which is very common in the area where the company is based. The first names are identical. Due to different ownership structures as a distinguishing feature (Felden and Hack, 2014), Roland Oberhofer is presented as the owner and managing director of the family business, whereas Roland Wyss is the CEO of Oberhofer in the condition of a non-family business. In addition, the company biographies were manipulated in terms of different ownership structures, regionality, values and company size on the basis of characteristics from the literature to distinguish family and non-family businesses (Baumgartner, 2009; Buß, 2006; Diez, 2006; Felden and Hack, 2014; Hirmer, 2015; Klein, 2010; Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2006; Pieper, 2007).

3.2 Procedure and measurements

The subjects were randomized to one of the two test conditions, knowing that they would be asked about the brand afterwards, and were presented with the stimulus for at least 45 s. After this time had elapsed, the questionnaire could be started.

First, brand credibility was measured using the widely used scale developed by Erdem and Swait (2004). This consists of seven items, although one item had to be slightly modified because our brand was fictitious. Brand credibility (α = 0.89, M = 5.09, SD = 1.04; e.g., “The Oberhofer brand is able to deliver on its promises.”) was measured on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree).

The brand personality was then operationalized using the established scale according to Aaker (1997). Although only the dimension sincerity (11 items, α = 0.93, M = 4.99, SD = 1.12; e.g., “down-to-earth”) and the facet reliability (3 items, α = 0.80, M = 5.02, SD = 1.05, e.g., “hard-working”) are the focus of the study, the entire inventory was collected using a seven-point Likert scale (1 = not at all true to 7 = completely true) in order to also have the additional option in the analysis of showing the particular importance of sincerity and reliability—compared to other brand personality dimensions and facets—in the brand communication of family businesses.

The attitude toward the brand (α = 0.94, M = 5.06, SD = 1.19; e.g., “not appealing”/“appealing”) and the purchase intention (α = 0.91, M = 4.46, SD = 1.12, e.g., “My purchase interest is very low.”/“My purchase interest is very high.”) were each measured using five semantic differentials or sentence pairs according to Spears and Singh (2004). A seven-point response format was used for this.

Afterwards, the subjects were asked to classify the brand origin of the displayed ad on the basis of the item “Oberhofer is a family business” (M = 5.21, SD = 1.97). The answers were again given on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree).

Finally, demographic data as well as a preference for cheese and the familiarity of the advertising face were collected as possible confounding factors or control variables. The subjects did not receive any compensation.

3.3 Participants

The sample was recruited primarily via Facebook. After excluding one person with conspicuous response behavior and nine people who said they knew the advertising face depicted, the result was a sample of 180 participants, of whom 52.2 percent were female. The age range was 16 to 69 years (M = 28.72, SD = 11.46). 53.9 percent of the sample had a university degree as their highest educational qualification. Of the 180 participants, n = 92 (51.1%) were randomly assigned to the family business condition and n = 88 (48.9%) to the non-family business condition. The two groups did not differ significantly in terms of gender [χ2(1, N = 180) = 0.83, p = 0.36], age [t(178) = 0.03, p = 0.96], or education [t(178) = −0.02, p = 0.98].

4 Results

The manipulation check showed a successful experimental manipulation. The advertisement of the family business (M = 6.45, SD = 0.94) was recognized as “from a family business” more strongly than the advertisement of the non-family business (M = 3.91, SD = 1.93), t(124.83) = 11.11, p < 0.001, d = 1.67.

As expected in the context of the first hypothesis, it was found that subjects rated the brand personality of family businesses (M = 5.46, SD = 0.85) as more sincere compared to non-family businesses (M = 4.52, SD = 1.17), t(158.41) = 6.18, p < 0.001, d = 0.93. Similarly, the brand personality of brands from family businesses (M = 5.24, SD = 0.97) was judged to be more reliable than brands from non-family businesses (M = 4.78, SD = 1.09), t(178) = 2.96, p < 0.01, d = 0.44. Hypotheses 1a and 1b are therefore confirmed.

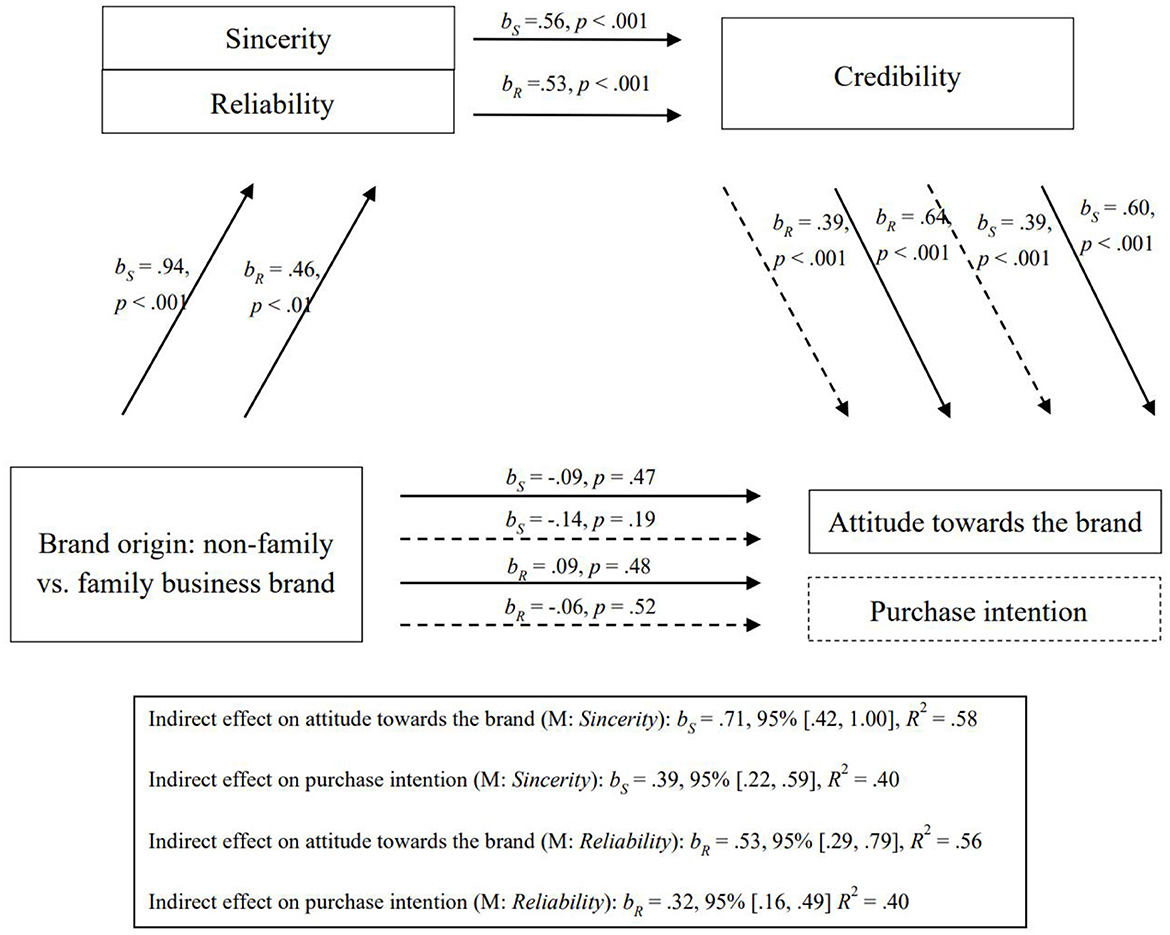

Further hypothesis testing was carried out by calculating four serial mediation analyses according to Hayes (2013) (see Figure 3 for details). As assumed in the second hypothesis, the brand was perceived as more credible the more sincere it was (bS = 0.56, p < 0.001). Similarly, stronger brand credibility also resulted from a more reliable perception (bR = 0.53, p < 0.001), so that hypotheses 2a and 2b are confirmed.

Figure 3. Serial mediation analyses according to Hayes (2013) with unstandardized coefficients and bootstrapping (m = 10,000).

As expected, increased brand credibility—either initiated through sincerity or reliability—led to both a more positive attitude toward the brand (bS = 0.60, p < 0.001; bR = 0.64, p < 0.001) and an increased purchase intention (bS = 0.39, p < 0.001; bR = 0.39, p < 0.001), so that hypotheses 3a and 3b can also be confirmed.

When the mediators of sincerity, reliability, and brand credibility were included, significant indirect effects of brand origin on attitude toward the brand [bS = 0.71, [0.42, 1.00]; bR = 0.53, [0.29, 0.79]] and purchase intention [bS = 0.39, [0.22, 0.59]; bR = 0.32, [0.16, 0.49]] can be observed on a 95% confidence interval. Consequently, hypotheses 4a and 4b as well as 5a and 5b are also confirmed. The individual mediation models explained 58 percent (mediators: sincerity and brand credibility) and 56 percent (mediators: reliability and brand credibility) of the variance in attitudes toward the brand and 40 percent of the variance in purchase intention, respectively.

5 Discussion

This study has responded to the call for research into the marketing of family businesses (Rovelli et al., 2022) by examining the credibility of family-owned brands for the first time. The key factors of sincerity and reliability emerged as important characteristics in the differentiation of family and non-family businesses. Incidentally, post-hoc analyses with the remaining brand personality dimensions (Aaker, 1997) could not determine any further differences between the two experimental groups, which underlines the prominent position of sincerity and reliability as important distinguishing features between brands from family-owned companies and brands from non-family-owned companies. Furthermore, they provide a good explanation as to why family-owned brands are perceived as more credible than brands from non-family-owned companies (cf. Jin and Sung, 2008, 2009; Kyung et al., 2010; Lude and Prügl, 2018). The consequences of this are, in particular, a more positive attitude toward the brand, but also an increased purchase intention (cf. Kemp and Bui, 2011; Laksamana, 2016; Li et al., 2011; Sheeraz et al., 2012, 2016; Wang and Yang, 2010, 2011). The stronger effect of credibility on attitude toward the brand, in contrast to purchase intention, can be explained by the fact that it takes less effort to adapt one's attitude toward a brand than it does to actually purchase the brand, which would require not only cognitive resources but also physical and material resources.

In order to counteract the current lack of experimental research in the field of family businesses, the study was conducted as an online experiment. In order to achieve the best possible internal validity, a randomized assignment was used, a fictitious brand was chosen to avoid attitudes toward the brand prior to contact with the stimulus, and both cheese preference and awareness of the advertising face were included as possible confounding factors. The fact that both experimental groups had a broad age spectrum and a balanced gender distribution was in turn beneficial to external validity.

It should be noted critically that the brand origin was manipulated using several differentiating characteristics of family and non-family businesses and is therefore to be regarded as a syndrome-like variable that bundles several variables (Trepte and Wirth, 2004). It is possible that differences in the perception of brand origin could have already resulted from a single differentiation characteristic. Perhaps simply mentioning the ownership structure (company owned by a family vs. company whose shares are listed on the stock exchange) would have been a sufficient distinguishing criterion, and the other descriptive characteristics could have been kept constant between the two stimuli. However, it could then have been the case that the remaining information, e.g., regionality, values and company size, would have been perceived as inappropriate or implausible for one of the two stimuli. Nevertheless, the subsequent manipulation check showed that the different brand origins were perceived by the subjects to the desired extent and that using fewer differentiation characteristics as a manipulation would probably have been too weak, so we feel vindicated in our approach.

Due to the still relatively young research field, there are numerous possibilities for further studies. Following on from this research, for example, replication with other industries or product groups would be interesting. For example, it is entirely plausible that not all types of products are suited to a brand with a family character—just think of an international and ambitious technology brand. Therefore, the perception of the fit between products and the type of company (= communicator) should be particularly decisive for credibility (cf., for effects of the fit between products and communicators: Breves et al., 2019; Janssen et al., 2021; Schramm and Kraft, 2024). An investigation into age- or culture-specific differences would also be interesting. We know, for example, that for many people, the “family” as the epitome of home becomes increasingly important as a symbol of belonging and security throughout their lives (Schramm et al., 2022), and that cultures can differ greatly in their affinity for individualism and thus for the primacy of the individual over collective forms of life, such as the family (Hofstede, 1993; Akolkar et al., 2024). For a replication of the study, the inclusion of further moderating factors such as individual awareness of tradition or different advertising formats could be considered.

The finding that brands can benefit from a family-oriented image in communication has proven to be particularly relevant in practice. This appears to be worthwhile not only for family businesses, but also for non-family businesses that consciously rely on an honest and reliable brand personality in their marketing strategy. However, attention should be paid to the fit with the product or brand, since this study examined dairy products as examples. Nevertheless, this study is an important advance in the expansion of the field of research and provides valuable insights for practitioners.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because in Germany, there is no legal obligation to have every study approved by an Ethics Committee and it is scientific common practice to only do this, if any harm concerning participants is expectable. In this study, as is obvious by the method section in this paper, no such harm was expected. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements because participants were informed about the study on the questionnaire’s home page and could then decide whether or not to participate. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) in Figures 1 & 2 for the publication of any potentially identifiable images.

Author contributions

HS: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. AZ: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aaker, J. L. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality. J. Market. Res. 34, 347–356. doi: 10.1177/002224379703400304

Akolkar, A. H., Neeraj, S., Vardhan, S., Upparu, N. R., and Khan, E. (2024). Cultural differences affecting advertising. Int. Res. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 3, 259–267. doi: 10.56472/25835238/IRJEMS-V3I10P130

Anridho, N., and Liao, Y.-K. (2013). The mediation roles of brand credibility and attitude on the performances of cause-related marketing. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. 4, 266–276.

Ballester, E. D., and Alleman, J. L. M. (2005). Does brand trust matter to brand equity? J. Brand Manag. 14, 187–196. doi: 10.1108/10610420510601058

Baumgartner, B. (2009). Familienunternehmen und Zukunftsgestaltung. Schlüsselfaktoren zur erfolgreichen Unternehmensnachfolge [Family Businesses and Shaping the Future. Key Factors for Successful Company Succession]. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler. doi: 10.1007/978-3-8349-8541-5

Baus, K. (2013). Die Familienstrategie. Wie Familien ihr Unternehmen über Generationen sichern [The family strategy. How Families Are Safeguarding Their Businesses for Generations to Come], 4th Edn. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-02824-4

Beck, S., and Kenning, P. (2015). The influence of retailers' family firm image on new product acceptance: an empirical investigation in the German FMCG market. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 40, 1126–1143. doi: 10.1108/IJRDM-06-2014-0079

Beck, S., and Prügl, R. (2018). Family firm reputation and humanization: consumers and the trust advantage of family firms under different conditions of brand familiarity. Fam. Business Rev. 31, 460–482. doi: 10.1177/0894486518792692

Bekk, M., and Spörrle, M. (2010). The influence of perceived personality characteristics on positive attitude towards and suitability of a celebrity as a marketing campaign endorser. Open Psychol. J. 3, 54–66. doi: 10.2174/1874350101003010054

Benavides-Velasco, C. A., Quintana-García, C., and Guzmán-Parra, V. F. (2013). Trends in family business research. Small Business Econ. 40, 41–57. doi: 10.1007/s11187-011-9362-3

Binz, C., Hair, J. F., Pieper, T. M., and Baldauf, A. (2013). Exploring the effect of distinct family firm reputation on consumers' preferences. J. Fam. Business Strat. 4, 3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jfbs.2012.12.004

Binz, C., and Smit, W. (2013). Sie sind ein Familienunternehmen – na und?!? Eine Untersuchung des reputationalen Effekts des “Status Familienunternehmen” [So you're a family business – so what? An investigation into the reputational effect of “family business status”]. Betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung und Praxis 2, 124–163.

Botero, I. C., Astrachan, C. B., and Calabrò, A. (2018). A receiver's approach to family business brands: exploring individual associations with the term “family firm”. J. Fam. Business Manag. 8, 94–112. doi: 10.1108/JFBM-03-2017-0010

Botero, I. C., Thomas, J., Graves, C., and Fediuk, T. A. (2013). Understanding multiple family firm identities: an exploration of the communicated identity in official websites. J. Fam. Business Strat. 4, 12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jfbs.2012.11.004

Breves, P. L., Liebers, N., Abt, M., and Kunze, A. (2019). The perceived fit between Instagram influencers and the endorsed brand: how influencer–brand fit affects source credibility and persuasive effectiveness. J. Advert. Res. 59, 440–454. doi: 10.2501/JAR-2019-030

Buß, E. (2006). “Unternehmensgeschichte und Markenhistorie. Die heimlichen Erfolgsfaktoren des Markenmanagements [Company history and brand history. The secret success factors of brand management],” in Die Bedeutung der Tradition für die Markenkommunikation. Konzepte und Instrumente zur ganzheitlichen Ausschöpfung des Erfolgspotenzials Markenhistorie, eds. N. O. Herbrand and S. Röhring (Stuttgart: Neues Fachwissen), 197–212.

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., and Sharma, P. (1999). Defining the family business by behavior. Entrepr. Theory Pract. 23, 19–39. doi: 10.1177/104225879902300402

Craig, J. B., Dibrell, C., and Davis, P. S. (2008). Leveraging family-based brand identity to enhance firm competitiveness and performance in family businesses. J. Small Business Manag. 46, 351–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-627X.2008.00248.x

Deephouse, D. L., and Jaskiewicz, P. (2013). Do family firms have better reputations than non-family firms? An integration of socioemotional wealth and social identity theories. J. Manag. Stud. 50, 337–360. doi: 10.1111/joms.12015

Diez, W. (2006). “Grundlegende potenziale von tradition im markenmanagement [The fundamental potential of tradition in brand management],” in Die Bedeutung der Tradition für die Markenkommunikation. Konzepte und Instrumente zur ganzheitlichen Ausschöpfung des Erfolgspotenzials Markenhistorie, eds. N. O. Herbrand and S. Röhring (Stuttgart: Neues Fachwissen), 181–196.

Dreysse, M. (2015). Mutterschaft und Familie: Inszenierungen in Theater und Performance [Motherhood and Family: Stagings in Theater and Performance]. Bielefeld: transcript.

Eisend, M. (2003). Glaubwürdigkeit in der Marketingkommunikation. Konzeption, Einflussfaktoren und Wirkungspotenzial [Credibility in Marketing Communication. Concept, Influencing Factors and Potential Impact]. Wiesbaden: Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag. doi: 10.1007/978-3-322-90954-1

Erdem, T., and Swait, J. (1998). Brand equity as a signaling phenomenon. J. Cons. Psychol. 7, 131–157. doi: 10.1207/s15327663jcp0702_02

Erdem, T., and Swait, J. (2004). Brand credibility, brand consideration, and choice. J. Cons. Res. 31, 191–198. doi: 10.1086/383434

Erdem, T., Swait, J., and Louviere, J. (2002). The impact of brand credibility on consumer price sensitivity. Int. J. Res. Market. 19, 1–19. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8116(01)00048-9

Esch, F.-R. (2005). Strategie und Technik der Markenführung [Strategy and Technique of Brand Management], 3rd Edn. Munich: Vahlen.

Felden, B., and Hack, A. (2014). Management von Familienunternehmen. Besonderheiten - Handlungsfelder – Instrumente [Management of Family Businesses. Special Features – Areas of Activity – Tools]. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler. doi: 10.1007/978-3-8349-4159-6

Gallucci, C., Santulli, R., and Calabrò, A. (2015). Does family involvement foster or hinder firm performance? The missing role of family-based branding strategies. J. Fam. Business Strat. 6, 155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jfbs.2015.07.003

Grace, P. I., and Furuoka, F. (2007). An examination of the celebrity endorsers' characteristics and their relationship with the image of consumer products. UNITAR E-J. 3, 27–41.

Grundmann, M., and Wernberger, A. (2014). Familie als Gemeinschaft – Gemeinschaften als Familie!? [Family as community – communities as family!?]. Sozialwissenschaften und Berufspraxis 37, 5–17.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hirmer, A.-L. (2015). Familienunternehmen als Kategorienmarke. Eine stakeholderspezifische Analyse der Markenwahrnehmung von Familienunternehmen [Family Businesses as a Category Brand. A Stakeholder-Specific Analysis of Brand Perception of Family Businesses]. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-10552-5

Hofstede, G. (1993). Cultural constraints in management theories. Acad. Manag. Exec. 7, 81–94. doi: 10.5465/ame.1993.9409142061

Hovland, C., and Weiss, W. A. (1951). The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opin. Q. 15, 635–650. doi: 10.1086/266350

Janssen, L., Schouten, A. P., and Croes, E. A. J. (2021). Influencer advertising on Instagram: product-influencer fit and number of followers affect advertising outcomes and influencer evaluations via credibility and identification. Int. J. Advert. 41, 101–127. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2021.1994205

Jaufenthaler, P., Kallmuenzer, A., Kraus, S., and De Massis, A. (2025). The localness effect of family firm branding on consumer perceptions and purchase intention: an experimental approach. J. Small Business Manag. 63, 590–619. doi: 10.1080/00472778.2024.2326581

Jin, S.-A. A., and Sung, Y. (2008). The roles of spokes-avatars' personalities in brand communication in 3D virtual environments. J. Brand Manag. 17, 317–327. doi: 10.1057/bm.2009.18

Jin, S.-A. A., and Sung, Y. (2009). The Effects of Spoke-Avatars' Personalities on source expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness in the 3D virtual environment. Adv. Cons. Res. 36, 877–878.

Kashmiri, S., and Mahajan, V. (2010). What's in a name? An analysis of the strategic behavior of family firms. Int. J. Res. Market. 27, 271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2010.04.001

Kemp, E., and Bui, M. (2011). Healthy brands: establishing brand credibility, commitment and connection among consumers. J. Cons. Market. 28, 429–437. doi: 10.1108/07363761111165949

Klein, S. B. (2010). Familienunternehmen: theoretische und empirische Grundlagen [Family Businesses: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations], 3rd Edn. Lohmar: Eul.

Koiranen, M. (2002). Over 100 years of age but still entrepreneurially active in business: exploring the values and family characteristics of old finnish family firms. Fam. Business Rev. 15, 175–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6248.2002.00175.x

Kyung, H., Kwon, O., and Sung, Y. (2010). The effects of spokes-characters' personalities of food products on source credibility. J. Food Prod. Market. 17, 65–78. doi: 10.1080/10454446.2011.532402

Laksamana, P. (2016). The influence of consumer ethnocentrism, perceived value and brand credibility on purchase intention: evidence from indonesia's banking industry. J. Market. Manag. 4, 92–99. doi: 10.15640/jmm.v4n2a8

Li, Y., Wang, X., and Yang, Z. (2011). The effects of corporate-brand credibility, perceived corporate-brand origin, and self-image congruence on purchase intention: evidence from china's auto industry. J. Glob. Market. 24, 58–68. doi: 10.1080/08911762.2011.545720

Lude, M., and Prügl, R. (2018). Why the family business brand matters: brand authenticity and the family firm trust inference. J. Business Res. 89, 121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.03.040

Micelotta, E. R., and Raynard, M. (2011). Concealing or revealing the family? Corporate brand identity strategies in family firms. Fam. Business Rev. 24, 197–216. doi: 10.1177/0894486511407321

Miller, D., and Le Breton-Miller, I. (2006). Family governance and firm performance. Agency, stewardship, and capabilities. Fam. Business Rev. 19, 73–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00063.x

Miroshnychenko, I., De Massis, A., Miller, D., and Barontini, R. (2020). Family business growth around the world. Entrepr. Theory Pract. 45, 682–708. doi: 10.1177/1042258720913028

Mitchell, A. A., and Olson, J. C. (1981). Are product beliefs the only mediator of advertising effect on brand attitude? J. Market. Res. 18, 318–332. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800306

Opielka, M. (2001). “Familie und familienpolitik [Family and family policy],” in Kindheit und Familie. Beiträge aus interdisziplinärer und kulturvergleichender Sicht, ed. F.-M. Konrad (Münster: Waxmann), 227–247.

Orth, U. R., and Green, M. T. (2009). Consumer loyalty to family versus non-family business: the role of store image, trust and satisfaction. J. Retail Cons. Serv. 16, 248–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2008.12.002

Pieper, T. M. (2007). Mechanisms to Assure Long-Term Family Business Survival– A Study of the Dynamics of Cohesion in Multigenerational Family Business Families. Bern: Peter Lang.

Reuber, R. A., and Fischer, E. (2011). Marketing (in) the family firm. Fam. Business Rev. 24, 193–196. doi: 10.1177/0894486511409979

Rovelli, P., Ferasso, M., De Massis, A., and Kraus, S. (2022). Thirty years of research in family business journals: status quo and future directions. J. Fam. Business Strat. 13:100422. doi: 10.1016/j.jfbs.2021.100422

Sageder, M., Duller, C., and Mitter, C. (2015). Reputation of family firms from a customer perspective. Int. J. Business Res. 15, 13–22. doi: 10.18374/IJBR-15-2.2

Salwen, M. B. (1987). Credibility of newspaper opinion polls: source, source intent and precision. J. Mass Commun. Q. 64, 813–819. doi: 10.1177/107769908706400420

Schellong, M., Kraiczy, N. D., Malär, L., and Hack, A. (2019). Family firm brands, perceptions of doing good, and consumer happiness. Entrepr. Theory Pract. 43, 921–946. doi: 10.1177/1042258717754202

Schramm, H., and Kraft, J. (2024). Are product placements in music videos beneficial for the artists? The impact of artist–product fit on viewers' persuasion knowledge and perceived credibility of the artist. Front. Commun. 9:1396483. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1396483

Schramm, H., Liebers, N., and Breves, P. (2022). ‘Heimat' – more than a sense of home: reviving a medieval concept for communication research. Commun. Res. Trends 41, 4–17.

Sheeraz, M., Iqbal, N., and Ahmed, N. (2012). Impact of brand credibility and consumer values on consumer purchase intentions in Pakistan. Int. J. Acad. Res. Business Soc. Sci. 2, 1–10.

Sheeraz, M., Khattak, A. K., Mahmood, S., and Iqbal, N. (2016). Mediation of attitude toward brand in the relationship between service brand credibility and purchase intentions. Pak. J. Commerce Soc. Sci. 10, 149–163.

Spears, N., and Singh, S. N. (2004). Measuring attitude toward the brand and purchase intentions. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 26, 53–66. doi: 10.1080/10641734.2004.10505164

Stiftung Familienunternehmen (2007). Die volkswirtschaftliche Bedeutung der Familienunternehmen [The Economic Importance of Family Businesses]. Stuttgart: Stiftung Familienunternehmen.

Trepte, S., and Wirth, W. (2004). “Kommunikationswissenschaftliche Experimentalforschung im Spannungsverhältnis zwischen interner und externer Validität [Experimental research in communication science in the tension between internal and external validity],” in Forschungslogik und -design in der Kommunikationswissenschaft. Einführung, Problematisierungen und Aspekte der Methodenlogik aus kommunikationswissenschaftlicher Perspektive, eds. W. Wirth, E. Lauf, and A. Fahr (Cologne: Herbert von Halem), 60–87.

Wang, X., and Yang, Z. (2010). The effect of brand credibility on consumers' brand purchase intention in emerging economies: the moderating role of brand awareness and brand image. J. Glob. Market. 23, 177–188. doi: 10.1080/08911762.2010.487419

Wang, X., and Yang, Z. (2011). The impact of brand credibility and brand personality on purchase intention: an empirical study in China. Adv. Int. Market. 21, 137–153. doi: 10.1108/S1474-7979(2011)0000021009

Wielsma, A. J., and Brunninge, O. (2019). “Who am I? Who are we?” Understanding the impact of family business identity on the development of individual and family identity in business families. J. Fam. Business Strat. 10, 38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jfbs.2019.01.006

Zanon, J., Scholl-Grissemann, U., Kallmuenzer, A., Kleinhansl, N., and Peters, M. (2019). How promoting a family firm image affects customer perception in the age of social media. J. Fam. Business Strat. 10, 28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jfbs.2019.01.007

Keywords: brand, brand personality, corporate communication, credibility, family business, values

Citation: Schramm H and Zinser A (2025) “I vouch for it with my name.” The influence of brand perception of family businesses on their credibility and the purchase intention of consumers. Front. Commun. 10:1607511. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1607511

Received: 07 April 2025; Accepted: 27 August 2025;

Published: 24 September 2025.

Edited by:

Peter Kwasi Oppong, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, GhanaReviewed by:

Justice Boateng Dankwah, University of Energy and Natural Resources, GhanaNarjess Aloui, Universite de Tunis El Manar Faculte des Sciences Economiques et de Gestion de Tunis, Tunisia

Copyright © 2025 Schramm and Zinser. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Holger Schramm, aG9sZ2VyLnNjaHJhbW1AdW5pLXd1ZXJ6YnVyZy5kZQ==

Holger Schramm

Holger Schramm Anna Zinser

Anna Zinser