- 1Department of Communication, Bhayangkara Jakarta Raya University, Jakarta, Indonesia

- 2Department of Communication Science and Community Development, IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia

- 3Department of Forest Management, IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia

This perspective presents a culturally grounded model of education for nomadic maritime communities, drawing on the lived experiences of the Bajo people in Wakatobi, Indonesia. Rooted in a sea-based way of life, the Bajo face systemic barriers to formal education due to rigid school structures that do not reflect seasonal mobility or cultural worldviews. The proposed On–Off School Model redefines education as a dynamic and reciprocal process, where formal instruction (“On”) aligns with times of settlement, and community-based experiential learning (“Off”) takes place during sea voyages. This framework is inspired by Indigenous Holistic Education, which integrates four interdependent dimensions: Body, Spirit, Heart, and Mind. From a developmental communication standpoint, the model highlights the importance of listening, co-creating, and honoring local knowledge systems. Rather than imposing top-down interventions, education has become a dialogic practice rooted in empathy, relevance, and respect. This perspective argues that inclusive education must be adaptable, place-based, and culturally affirming, particularly for historically marginalized groups like the Bajo. The On–Off School invites scholars and policymakers to rethink educational equity through the lens of movement, culture, and communication.

1 Introduction

Education is a fundamental right for every citizen, including those from geographically and culturally distinct communities, such as Indonesia’s Sea Nomads (Sujatmoko, 2016). However, the formal education system in Indonesia remains rigid and uniform, often failing to reach or serve the diversity of coastal populations. Among them are the Bajo people, also known as Bajau Laut, Suku Badjaw, or Same, who are renowned for their nomadic lifestyle at sea. Living aboard traditional wooden boats (bidok lautan), the Bajo do not merely see the ocean as a livelihood source, but as a cultural, spiritual, and social world in itself (Ariando, 2023; Mustamin and Macpal, 2020).

For Bajo children, accessing formal education is challenging. The fixed schedules and spatial rigidity of conventional schools clash with the flexible seasonal rhythms of their maritime life. This mismatch contributes to the high rates of absenteeism and school dropout. The literature points to multiple interlinked factors: the cultural primacy of sea-based life (Ikhsan and Syarif, 2020). Low parental awareness of education (Budi Lestari et al., 2020), lack of family support for schooling (Awaru, 2020), and children’s preference to join their families at sea rather than attend classes (Mustamin and Macpal, 2020). Moreover, structural efforts to promote education in these communities are often constrained by top-down frameworks that do not account for social and cultural contexts (Maemunah et al., 2021).

The result is a persistent educational gap and cultural disconnect. Stationary schooling models have not adapted to the mobility, values, or worldview of the Bajo, and thus contribute to what can be termed communication failure in development. What is needed is not merely access to education, but an approach that communicates with and responds to cultural realities in a holistic manner. This Perspective proposes the On–Off School Model as an alternative framework for inclusive education among sea-based Indigenous communities. Grounded in the holistic Indigenous education model, which integrates the dimensions of Body, Spirit, Heart, and Mind (Archibald, 2008), this approach rethinks learning as a relational process embedded in context. It is designed to be flexible, culturally attuned, and dialogical, affirming local knowledge while offering viable pathways to formal educational recognition through non-conventional means, such as Paket A, B, and C programs. Ultimately, this article argues for a middle path in an education model that does not seek to assimilate Bajo into a sedentary system but instead builds adaptive bridges between schooling and seafaring life. It is through such an approach that education becomes a space of empowerment, not exclusion a form of developmental communication in motion. Education should empower communities to design their own learning systems ones that are relevant, resilient, and sustainable (Smith, 2012). Through such an approach, education becomes a space of empowerment rather than exclusion a dynamic form of development communication.

The On–Off School Model was developed through a participatory qualitative approach that positioned the Bajo people as the main subjects in the formulation of this alternative educational model. This study employed a narrative design rooted in Indigenous Research Methodologies (Smith, 2012), where the experiences, values, and narratives of Indigenous communities serve as primary sources of knowledge. Knowledge is not only understood intellectually but is also relational, spiritual, place-based, and grounded in the collective experiences and historical memory of the community (Kovach, 2021). Thus, the On–Off School Model was developed not through a top-down approach but through an ethical and dialogical communication process, in line with the principles of development communication that honor cultural diversity.

2 The Bajo people of Wakatobi: living with the sea

2.1 A sea-oriented way of life

Coastal regions have profound ecological and cultural significance for many communities, particularly in maritime Southeast Asia. Among the groups most intimately connected to the sea are the Bajo people, also referred to as Sea Nomads, who inhabit the Wakatobi Islands in Indonesia. As ocean dwellers, the Bajo depend entirely on marine resources for their livelihood, with fishing, pearl diving, and sea cucumber harvesting forming the backbone of their local economies (Ariando, 2023; Nurhaliza, 2021). Beyond economic survival, the Bajo lifestyle is infused with rich cultural traditions that structure daily routines, seasonal movements, and socialization practices. For instance, parents train their children in navigation, weather reading, and sea rituals from a young age (Nurhaliza and Suciati, 2019). The sea is not merely a workplace but a spiritual, social, and epistemological space. Traditional norms and values are deeply embedded in their behavior, shaping how Bajo people engage with one another and the natural world (Rustan Surya and Nasution, 2018).

Despite the cultural resilience of Bajo, they face compounded vulnerabilities, such as structural poverty, geographic isolation, and limited access to public services, including education. Their unique worldview and nomadic habits have largely been excluded from mainstream development paradigms, highlighting a critical communication gap between state systems and indigenous realities.

2.2 Educational exclusion and structural incompatibility

The Bajo families in Wakatobi migrate seasonally, depending on oceanic conditions and fishing cycles. Children often accompany their families on long voyages, making consistent school attendance almost impossible (Ikhsan and Syarif, 2020). The fixed calendar of formal schools demanding daily physical presence–stands in stark contrast to the dynamic rhythms of sea-based life. This reflects what (Sharma, 2014) refers to as power chronography the structured power relations embedded in the organization of time. When learning schedules are standardized at the national level without adapting to the ecological calendar and life rhythms of the Bajo people, it results in a profound form of temporal exclusion. Moreover, educational exclusion is not only logistical but also cultural. School curricula rarely reflect maritime knowledge or cultural identity. Studies show that many Bajo parents prioritize economic survival over formal schooling and may lack awareness of its long-term benefits (Awaru, 2020; Budi Lestari et al., 2020). Children often choose to participate in fishing activities rather than attend school, especially when learning feels disconnected from their lived experiences. National education policies, including the 9-Year Compulsory Education Program and Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 4), have not adequately addressed the systemic marginalization of mobile communities. While Indonesia’s 2022 Education Law expands compulsory education to 13 years, implementation remains rooted in sedentary logic. For Bajo, this perpetuates educational inequity and cultural dissonance. What is needed is A model that bridges formal schooling with the cultural lifeworlds of sea-based communities is required. This requires not only physical access to education but also a rethinking of what it means to learn where, when, and from whom. This also involves understanding that each individual or group experiences time differently, depending on their type of work, social roles, and living conditions (Sharma, 2014).

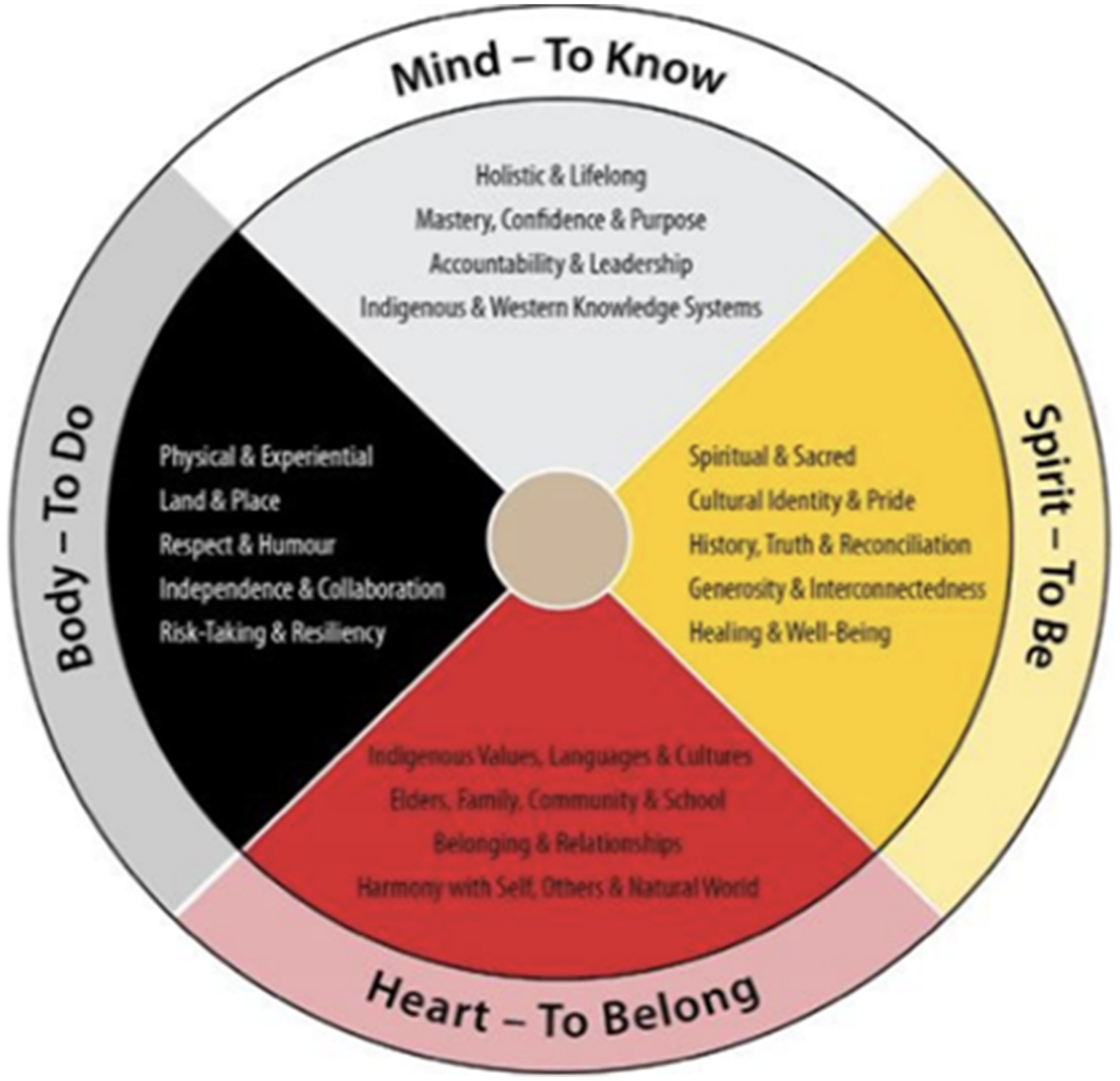

3 Rethinking learning through a holistic indigenous education framework

Holistic education, first articulated by thinkers like Rousseau and expanded through indigenous pedagogies, emphasizes the development of the whole person: intellectually, emotionally, physically, socially, esthetically, and spiritually (Gultekin et al., 2013; Javaherpour, 2023). At its core, holistic learning recognizes that knowledge is relational, place-based, and interconnected. It prioritizes inclusion, balance, and cultural continuity. In the context of indigenous education, this approach is further developed through the Indigenous Education Holistic Lifelong Learning Framework (Pritchard, 2022), which outlines four interdependent learning domains: Spirit To Be: Nurturing spiritual identity, and cultural heritage. Heart to Belong: Fostering emotional well-being and social connection. Body to Do: Encouraging experiential, action-based learning. Mind To Know: Promoting critical and contextual cognitive development.

These dimensions are not isolated categories but integrated elements of human growth. Together, these reflect a worldview in which learning is lifelong, deeply rooted in culture, and inseparable from place and identity. This aligns with Smith (2012), who asserts that Indigenous knowledge cannot be separated from place. In Indigenous epistemology, place is not merely a geographic location, but a living entity that holds spirituality, social relationships, and collective history (Smith, 2012). In the context of the Bajo community, the sea, the coast, and the seasons serve as “learning classrooms” that carry ecological, ethical, and practical values. In applying this model to the Bajo community, we see an opportunity to reframe developmental communication as a two-way process: one that listens, adapts, and evolves with the rhythms of life at sea. Rather than imposing rigid standards, holistic indigenous education offers a flexible, community-based strategy that values knowledge passed down through generations alongside formal academic content.

Figure 1 illustrates a holistic model of education conceptualized as a lifelong learning process:

1. Comprehensive, engaging the full spectrum of human experience—spirit, emotions, body, and mind.

2. Lifelong, continuing across all stages of life.

3. Culturally rooted, grounded in the values, stories, and traditions of Indigenous communities; and,

4. Collectively supported, involving families, Elders, and Knowledge Keepers as central figures in the learning process.

The model is symbolized by the medicine wheel, a cultural representation of life cycles and balance in Anishinaabe philosophy. It emphasizes four essential dimensions of human development: spirit – learners are encouraged to honor their cultural heritage, explore local values, and develop a spiritual identity. Heart – To Belong: Emphasizes the importance of social relationships, empathy, and a sense of belonging rooted in language and local culture. Body – To Do: Centers for action-based learning—engaging with nature, practicing skills, and gaining knowledge through lived experience. Mind To Know: Encourages curiosity, critical thinking, and creativity, supporting learners in building confidence and contextual understanding. This holistic framework challenges reductionist views of education by centering on relationality, spirituality, and cultural resilience as vital components of the development of communication and indigenous knowledge systems.

The On–Off School Model, developed through a holistic educational approach, is not a rejection of the national education system but rather a contextual adaptation that bridges the needs of maritime or sea-nomadic communities like the Bajo. In Indonesia’s education system, the principles of equity and inclusion are enshrined in Law No. 20 of 2003 on the National Education System, particularly Article 5, paragraph 1, which states that “every citizen has the right to obtain quality education.” The On–Off School Model aligns with the efforts of the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education in promoting the Merdeka Curriculum (Independent Learning policy), which emphasizes flexible learning tailored to local needs and positions learners as active subjects in the learning process (Aditomo, 2024). Guided by these principles, the On–Off model stands as a concrete form of contextual educational innovation. The On–Off model can be integrated into non-formal education pathways through equivalency education programs (Package A/B/C). In this way, Bajo children can still participate in equivalency examinations to obtain official diplomas recognized by the state.

3.1 Applying holistic indigenous education across global contexts

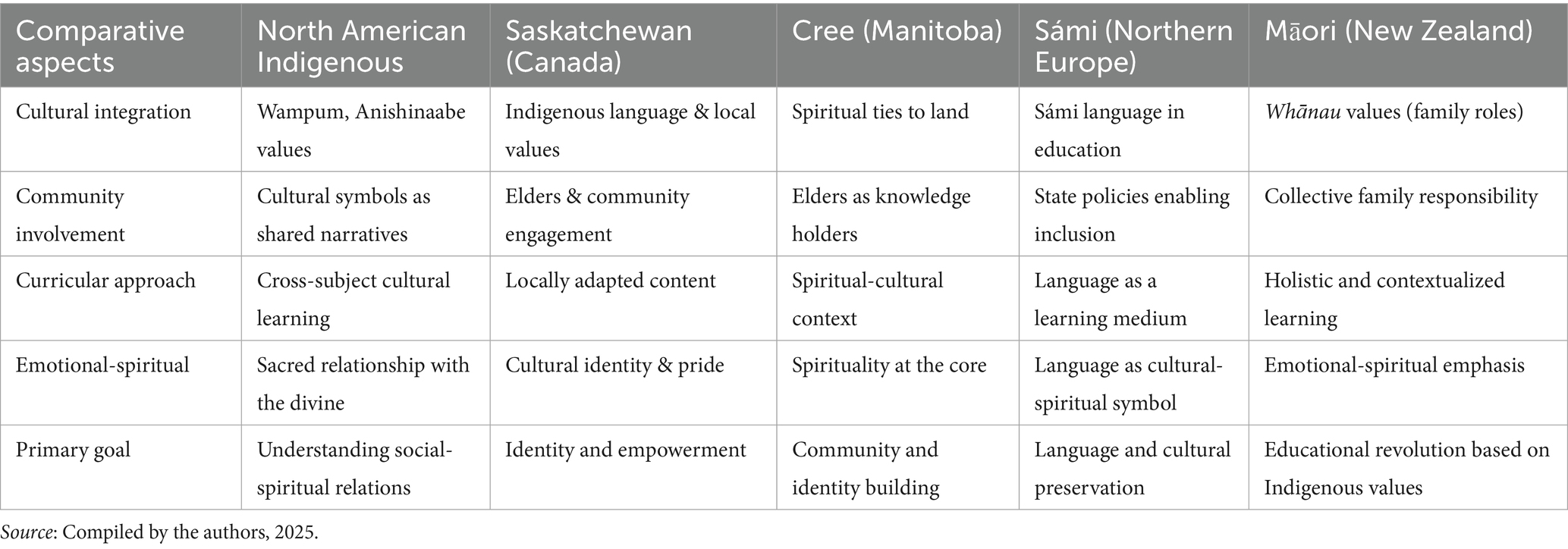

Indigenous communities around the world have experienced significant educational transformations through holistic approaches that integrate the Body, Spirit, Heart, and Mind. These approaches reflect a growing awareness that culturally rooted experience-based learning is more effective in shaping identity, character, and contextual knowledge (Warren and Quine, 2013). Such models are increasingly adopted in countries with significant indigenous populations, offering valuable insights into how culturally grounded education can promote both academic and cultural growth. In North America, particularly among Anishinaabe communities, holistic education is deeply tied to spiritual philosophy. The use of cultural symbols, such as wampums, illustrates how indigenous knowledge can be embedded across curricular subjects. Teachers integrate stories and traditions as part of everyday learning, creating culturally affirming classrooms (Morcom, 2017). In Northern Saskatchewan, alternative schools emphasize the use of indigenous languages, community elders, and value-based learning to foster identity and empowerment among indigenous students (Andrews et al., 2023). Among the Cree communities in Northern Manitoba, education is seen as a process rooted in spirituality, cultural heritage, and land. Elderly people play a central role in maintaining knowledge systems that connect students to their history and community (Hansen, 2018). In Northern Europe, educational reforms for the Sámi people have focused on language rights. Policies now support instruction in Sámi languages, preserving both linguistic and cultural identities through formal education (Keskitalo, 2022). In New Zealand, the Māori have developed a culturally rich educational system that emphasizes (a) cultural integration of whānau values, (b) collective responsibility for children’s learning, and (c) emotional-spiritual growth through Kaupapa Māori pedagogy. The Māori model has become a global reference point for holistic identity-based education (Hingangaroa Smith, 2000). A summary of these international approaches is presented Table 1.

4 The On–Off School Model: a holistic approach for the Bajo community

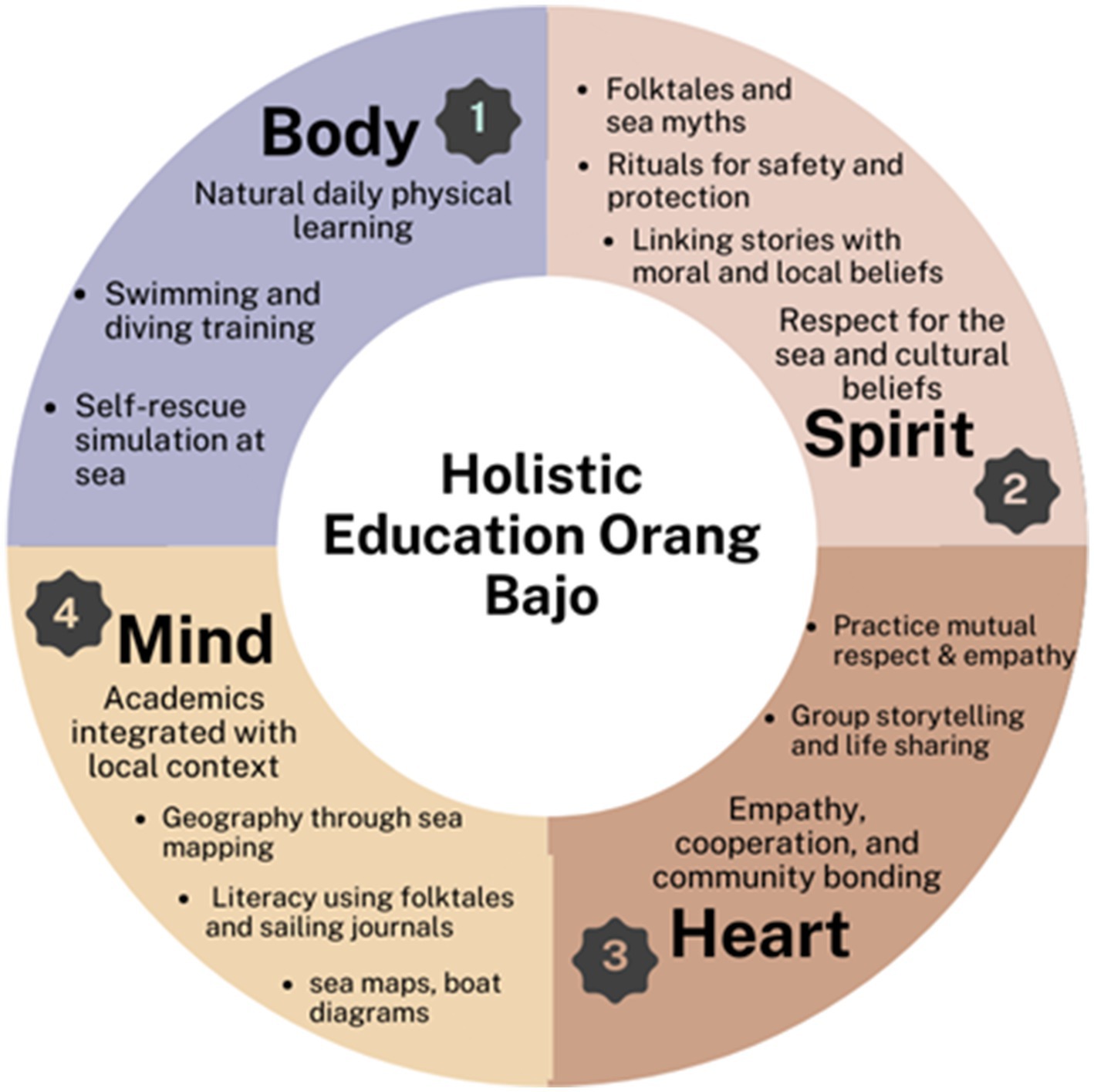

Providing equitable and culturally relevant education for Bajo requires more than expanding access or improving infrastructure. It demands a paradigm shift, one that adapts to the natural rhythms of sea-based life. In this context, we propose the On–Off School Model, an innovative educational framework grounded in indigenous holistic learning and tailored to the cyclical nature of Bajo livelihoods (Figure 2).

Figure 2. On–Off School Model: adaptive integration of formal and informal learning in the Bajo context.

4.1 Adaptive learning across ocean rhythms

The On–Off School Model is designed to align learning activities with the seasonal conditions of the sea that shape the rhythms of life among the Bajo people. During the western monsoon (October to February), when high waves and strong winds temporarily suspend fishing activities, children can engage in structured face-to-face learning. This phase is known as the On period, during which formal education takes place, combining the national curriculum with locally relevant content such as maritime culture, the history of Bajo migration, and coastal conservation.

In contrast, during the eastern monsoon (May to August), when the sea is calm, Bajo families embark on extended fishing journeys and leave their settlements. This marks the beginning of the Off period, where children learn through real-life experiences at sea, guided by their parents. Children learn to recognize wind patterns, ocean currents, record their catches, understand coral reef ecosystems, determine the best fishing times, and practice sustainable ways of life at sea. The length of time spent at sea varies, depending on the distances traveled by the Bajo. Transitional periods (March–April and September) can be utilized for collecting assignments and evaluating children’s learning from the Off phase. Schools may provide self-learning guides for children to bring along during their time at sea with their parents. Children can also be asked to write daily journals documenting the experiences and lessons they gain while accompanying their families. This represents a form of community-based, experiential learning that recognizes local epistemology as a legitimate and meaningful source of knowledge (Kovach, 2021).

Essentially, the rhythm of the sea does not always change predictably, and the shift between On and Off phases can be carried out flexibly, following natural rhythms and local weather conditions. This underscores the importance of reconceptualizing space as something that is not static, homogenous, or neutral. As proposed space should be understood through three key principles: space is the product of interrelations; space is a sphere for diversity; and space and time are always in process, never complete (One et al., 2020). In the context of the Bajo people, space is not merely a geographical location it is shaped by relationships between humans and the sea, between older and younger generations, and between local knowledge and formal education. A similar community-based learning approach can be seen among the Moken children in the Surin Islands, Thailand, through a program known as the “Floating Moken School.” This program aims to integrate traditional skills into the education of Moken children, who face barriers to accessing formal education. For example, children are taught how to row and sail traditional boats, learn the history and cultural values of the Moken people, and acquire diving and fishing skills as part of their daily lived environment (Moken Ancestral Knowledge Teaching, 2025). Thus, space is not a closed entity but an open, dynamic one, constantly shaped by human practice. Education models must therefore be designed with flexibility, capable of adapting to the ever-changing socio-ecological dynamics of mobile communities.

4.2 Culturally responsive curriculum

A major issue frequently encountered in the education of Indigenous communities is the mismatch between the standardized structure of the formal curriculum and the dynamic, context-based learning needs of local communities (Smith, 2012). Therefore, a culturally responsive curriculum approach is needed one that ensures both the sustainability of learning and its socio-cultural relevance. In the context of maritime communities such as the Bajo, the development of a culturally responsive curriculum is not a rejection of the national curriculum, but rather a comprehensive adaptation recognizing that meaningful education must be rooted in the socio-cultural realities of learners.

In this regard, the balance between national core competencies and local context becomes essential to ensure that learning is not disconnected from cultural roots while also keeping pace with national development goals. Each subject continues to follow the National Competency Standards, including literacy and numeracy, but these are integrated across disciplines. For example: Science is contextualized through marine ecosystems, tides, and coral conservation. Children learn directly from observing coral reefs, plankton, fish, and seagrass. They not only identify marine species but also understand food chains based on what they observe and experience while accompanying their families at sea. Geography is taught through local mapping and traditional navigation. Bajo children learn to orient themselves using the position of the sun, wind, and stars, and they draw maps charting their parents’ sailing routes from their village to distant fishing grounds (such as in Flores). These hand-drawn maps are used to assess their understanding of space and direction. Arts are enriched through oral traditions, sea songs, and the heritage of boatmaking. Children learn to interpret the symbols on boat sails and sing traditional Bajo songs.

Spiritual knowledge is conveyed through Religion and Civics Education, where children learn values of respect for the sea as a living space through storytelling and oral traditions about maritime customs such as taboos against littering the ocean. The balance between national educational competencies and local cultural wisdom can be maintained through the principles of curriculum contextualization, local enrichment in learning design, and the application of adaptive learning models such as the On–Off School. In this way, knowledge is not separated from life knowledge is rooted in environment, culture, and practice. As (Mungmachon, 2012) asserts, local knowledge encompasses survival, cooperation, and moral values essential for sustaining the community.

4.3 Legal pathways and certification

To ensure that Bajo children are not excluded from broader educational trajectories, the On–Off School Model integrates alternative certification mechanisms, such as Paket A, B, and C—non-formal equivalency programs recognized by the Indonesian government. With proper documentation and continuous evaluation, these certifications allow students to access higher education and formal employment while maintaining their traditional lifestyle.

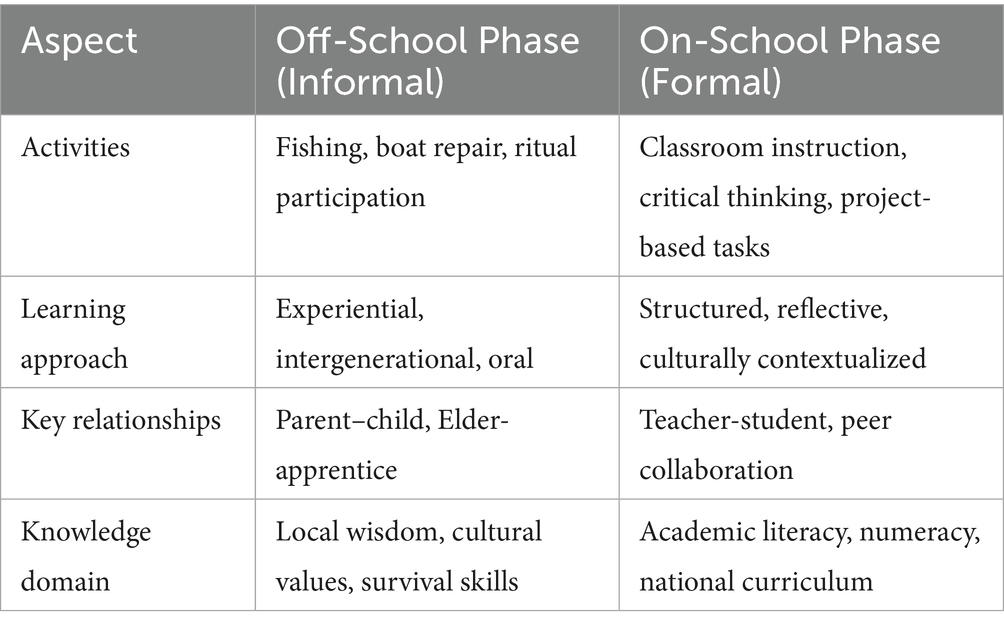

4.4 Synthesis of formal and informal learning

Table 2 illustrates how the On–Off School Model strives to create a balance between formal and informal education, positioning them not in opposition but as complementary domains. Bajo children do not learn solely from books or within classroom walls; they also acquire contextualized knowledge through lived experience. This form of learning builds resilience, identity, and locally grounded skills, which Mungmachon (2012) classifies into three essential knowledge domains:

1. Knowledge for sustaining community (e.g., values, stories, customs),

2. Knowledge for livelihood and,

3. Knowledge for harmony and collective well-being.

Table 2. Comparative structure between Off-School and On-School learning phases in the On–Off School model.

When applied through the lens of holistic Indigenous education, this triad seamlessly maps onto the four dimensions of learning: Body, Spirit, Heart, and Mind. Below, we outline how each dimension can be enacted through culturally grounded learning activities within the On–Off School context.

Body (Physical Learning) Physical education in the Bajo context emerges naturally from daily life. Activities included swimming and diving training sessions guided by physical education teachers, safety drills for ocean survival, and boat maintenance. These practices build not only physical competence but also environmental awareness and risk management. Spirit (Spiritual Learning): The spiritual dimension is deeply embedded in Bajo culture. The sea is regarded as a living entity that deserves respect. Children are introduced to this worldview through folk stories, maritime myths, and ancestral rituals such as tolak bala (protective sea rites), often facilitated by elders. These activities instill ethical stewardship and a sacred understanding of the ocean as a shared life space.

Implementation examples:

• Listening to sea legends from community elders.

• Storytelling sessions focused on cultural beliefs and moral reflection.

• Participating in rituals and reflecting on spiritual values in class discussions.

4.5 Heart (emotional and social learning)

Through community-based projects, children learn empathy, cooperation, and shared responsibility. Emotional literacy is shaped through shared experiences and relational practices that strengthen interpersonal bonds. A contextual approach is needed one that positions the community as a learning space and interpersonal relationships as a medium of learning. Learning activities are designed to actively involve parents as relational facilitators. This can be implemented through activities such as:

Story circles and life-sharing in small groups. For example, children learn to manage their emotions at sea such as dealing with fear during storms or handling disagreements through direct adult guidance. Children are also encouraged to share daily experiences by expressing feelings of fear, joy, or disappointment. Collaborative projects, such as beach cleanups or peer mentoring. Children are engaged in collective tasks such as repairing fishing nets, preparing meals together, or helping other families with daily chores. Rituals and traditions as a medium for emotional learning. Listening to stories at night becomes a reflective space for instilling values like patience, respect, and compassion. For instance, children are invited to listen to tales that depict the sea as a living entity worthy of respect, thereby nurturing empathy toward nature and others. By designing contextual and collaborative activities during the Off phase, emotional and social learning not only continues but becomes more authentic. Social interaction challenges can be addressed through community-based learning models.

4.6 Mind (cognitive learning)

Academic subjects are not abandoned; they are contextualized to reflect local knowledge systems. Mathematics can involve calculating fish yields or navigation distances, science can explore coral reef ecosystems, and geography becomes an exercise in mapping sea routes. Cognitive development is rooted in its relevance. Implementation examples:

• Using local learning media: Bajo sea maps, boat diagrams, marine biodiversity visuals.

• Experiential projects: ocean observation logs, tide tracking, community surveys.

• Literacy programs based on oral traditions and seafaring narratives.

5 Discussion

The On–Off School Model provides a compelling example of how education can be reimagined through the lens of development communication and indigenous pedagogy. This challenges the dominant educational paradigms that treat learning as a static, school-bound process divorced from place, culture, and daily life. In contrast, the on–off approach proposes a fluid, culturally grounded system in which formal and informal learning intersect in response to the rhythms of the sea and the values of the Bajo people. By adopting the holistic framework of Body, Spirit, Heart, and Mind, the model affirms that meaningful learning must engage in the full spectrum of human development. Children are not only prepared for academic achievement but also for ethical decision-making, social empathy, cultural pride, and environmental awareness. The integration of local ecological knowledge, spiritual narratives, and communal values exemplifies the co-creation of knowledge as a communicative act, where teachers, families, and students become collaborators rather than passive recipients.

From a developmental communication perspective, the On–Off School functions as a dialogic platform. It facilitates two-way exchanges between formal institutions and local communities, where cultural capital is not erased but honored and woven into pedagogy. This model foregrounds participation, relevance, and respect as foundational to educational justice, especially in indigenous and marginalized settings.

Efforts must be made to implement the On–Off School Model, including active community involvement from parents, elders, community leaders, and teachers. First, parents can be informally trained through community-based meetings to serve as learning facilitators during the Off phase. In this role, parents act as family learning companions, and their involvement can be included in the child’s flexible individual learning plan.

Second, community elders are involved in sharing stories about cultural rituals such as reverence for the sea. This activity strengthens the Heart to Belong and Spirit to Be dimensions within a holistic learning framework while also serving as a means of transmitting deep customary values.

Third, it is necessary to establish a village learning forum initiated by the village leadership. These forums can be conducted during transitional periods to align school activities with the socio-economic cycles of the Bajo community (such as fishing seasons, customary ceremonies, and religious celebrations). Involving local actors fosters social dialog and participatory learning. These practices cultivate a sense of ownership, enhance the relevance of education, and sustain the connection between education and community life.

Various challenges may arise in implementing the On–Off School Model. For instance, during the Off phase, when children accompany their families at sea for extended periods, there is a risk of losing continuity in basic literacy and numeracy due to limited learning media or lack of structured guidance. Not all parents are able or prepared to act as learning facilitators during this time—either due to limited literacy or the demands of their work at sea.

To address these challenges, several measures can be taken. First, the transitional periods can be used to rebuild children’s motivation through enjoyable activities such as storytelling about sea voyages, mapping learning experiences, and open-air classes that celebrate local knowledge. Second, teachers can maintain regular communication with parents to build awareness that formal education does not negate local knowledge but rather reinforces children’s capacity to shape their future. This also fosters mutual trust and understanding.

6 Conclusion

The On–Off School Model is not merely an educational innovation; it represents a cultural and communicative strategy for inclusion, equity, and resilience. It reframes education as a dynamic relationship between knowledge systems in which tradition and transformation coexist. For the Bajo peopleand other nomadic or coastal communities, this model allows children to access formal education without forsaking their identity, way of life, or spiritual connections to the sea. It nurtures holistic learners who are physically capable, spiritually rooted, emotionally engaged, and intellectually curious.

Crucially, the success of this model depends on collective responsibility. Parents, the elderly, local leaders, and educators must act as co-facilitators of learning. During the OFF phase, community members pass on cultural knowledge, and during the ON phase, teachers translate that knowledge into academic pathways. Education, therefore, becomes a shared journey embedded in mutual respect and sustained by local relevance. As a contribution to the field of communication development, this article calls for education policies that move literally and symbolically—with the communities they serve. The On–Off School is one such movement: a rhythm of resistance and renewal, where learning flows like the tides that shape the lives of nomads.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

WS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AF: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. DS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Department of Communication, Bhayangkara Jakarta Raya University, Indonesia; the Department of Communication Science and Community Development, IPB University, Indonesia; and the Department of Forest Management, IPB University, Indonesia, for their support and resources throughout this research. Their guidance was invaluable in shaping this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aditomo, A. (2024). Panduan Pengembangan Kurikulum Satuan Pendidikan Edisi Revisi Tahun 2024. BSKAP Kemendikbudristek. 4, 4–132.

Andrews, J. W., Murry, A., and Istvanffy, P. (2023). A holistic approach to on-reserve school transformation: pursuing pedagogy, leadership, cultural knowledge, and mental health as paths of change. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 38, 64–85. doi: 10.1177/08295735221146354

Archibald, J. (2008). Indigenous story work: educating the heart, mind, body, and spirit. Vancouver, Canada: UBC Press.

Ariando, W. (2023). Stringing the islands: the Bajau in Wakatobi Islands (issue august). Palmerah Sydnicate. Available online at: http://cuir.car.chula.ac.th/handle/123456789/80777 (Accessed March 28, 2025).

Awaru, A. (2020). “Sosiologi Keluarga” in Media Sains Indonesia (Makassar, Indonesia and Bandung, Indonesia: Media Sains Indonesia).

Budi Lestari, A. Y., Kurniawan, F., and Bayu Ardi, R. (2020). Penyebeb Tingginya Angka Anak Putus Sekolah Jenjang Sekolah Dasar (SD). Jurnal Ilmiah Sekolah Dasar 4:299. doi: 10.23887/jisd.v4i2.24470

Gultekin, M., Cigerci, F. M., and Merc, A. (2013). Holistic education. J. Educ. Anf Future 3:1702. doi: 10.58830/ozgur.pub383.c1702

Hansen, J. (2018). Cree elders’ perspectives on land-based education: a case study. Brock Educ. J. 28, 74–91. doi: 10.26522/brocked.v28i1.783

Hingangaroa Smith, G. (2000). Maori education: revolution and transformative action. Can. J. Nativ. Educ. 24, 57–72. doi: 10.14288/cjne.v24i1.195881

Ikhsan, A. M., and Syarif, E. (2020). Formal child education in the fisherman perspective of the Bajo tribe in Bajo Village. La Geografia 18, 269–288. doi: 10.35580/lageografia.v18i3.13606

Javaherpour, A. (2023). Miller, J. P. The holistic curriculum, vol. 95. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2019–2021.

Keskitalo, P. (2022). Timelines and strategies in Sami education. Indigenising Educ. Citizenship, 33–52. doi: 10.18261/9788215053417-2022-03

Kovach, M. (2021). Indigenous methodologies; characteristics, conversations, and contexts. 2nd Edn. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Maemunah, M., Haniah, S., and Mukramin, S. (2021). Education marginalization of Bajo children based on local wisdom. Int. J. Educ. Res. Soc. Sci. 2, 585–591. doi: 10.51601/ijersc.v2i3.80

Moken Ancestral Knowledge Teaching. (2025). Moken Tourism Team. Available at: https://www.mokenislands.com/moken-ancestral-knowledge-teaching/

Morcom, L. A. (2017). Indigenous holistic education in philosophy and practice, with wampum as a case study. Foro de Educ. 15:121. doi: 10.14516/fde.572

Mungmachon, M. R. (2012). Knowledge and local wisdom: community treasure. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2, 174–181. Available at: https://www.ijhssnet.com/journal/index/1114

Mustamin, K., and Macpal, S. (2020). Ritual Dalam Siklus Hidup Masyarakat Bajo Di Torosiaje. Al-Qalam 26:203. doi: 10.31969/alq.v26i1.799

Nurhaliza, W. O. S. (2021). Studi Etnografi Komunikasi: Aktivitas Melaut Sebagi Sumber Kehidupan Masyarakat Suku Bajo Sampela. Jurnal Ilmu Komunikasi UHO: Jurnal Penelitian Kajian Ilmu Komunikasi Dan Informasi 6:548. doi: 10.52423/jikuho.v6i4.21246

Nurhaliza, W. O. S., and Suciati, T. N. (2019). Potret Sosial Budaya Masyarakat Suku Bajo Sampela di kabupaten Wakatobi. Jurnal Komunikasi Universitas Garut: Hasil Pemikiran Dan Penelitian 5, 341–356. doi: 10.10358/jk.v5i2.671

One, P., Two, P., and Three, P. (2020). Massey, Doreen. SAGE Research Methods Foundations. doi: 10.4135/9781526421036801351

Pritchard, L. A. (2022). Indigenous education holistic lifelong learning framework. Calgary, Canada: Calgary Board of Education.

Rustan Surya, B., and Nasution, M. A. (2018). Adaptasi dan Perubahan Sosial Kehidupan Suku Bajo (Studi Kasus Suku Bajo Kelurahan Bajoe Kecamatan Tanete Riattang Timur Kabupaten Bone). Urban Regional Stud. J. 1, 31–37. Available at: https://journal.unibos.ac.id/ursj/issue/view/1

Sharma, S. (2014). “In the meantime: temporality and culture politics” in Sustainability (Switzerland) (Durham, USA: Duke University Press), 11.

Smith, L. T. (2012). “Decolonizing methodologies research and indigenous peoples” in Decolonizing methodologies; research and indigenous peoples. 2nd ed (London, UK: Zed Books).

Sujatmoko, E. (2016). Hak Warga Negara Dalam Memperoleh Pendidikan. Jurnal Konstitusi 7:181. doi: 10.31078/jk718

Keywords: development communication, indigenous education, holistic learning, Sea Nomads, Bajo community

Citation: Nurhaliza WOS, Sarwoprasodjo S, Fatchiya A and Suharjito D (2025) Rethinking education for Sea Nomads through the On–Off School Model: a perspective on holistic and culturally adaptive schooling for the Bajo people in Indonesia. Front. Commun. 10:1611083. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1611083

Edited by:

Anastassia Zabrodskaja, Tallinn University, EstoniaReviewed by:

Hilda Wono, Universitas Ciputra, IndonesiaMuhammad Taufiq Al Makmun, Sebelas Maret University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Nurhaliza, Sarwoprasodjo, Fatchiya and Suharjito. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wa Ode Sitti Nurhaliza, d2Eub2RlQGRzbi51YmhhcmFqYXlhLmFjLmlk

Wa Ode Sitti Nurhaliza

Wa Ode Sitti Nurhaliza Sarwititi Sarwoprasodjo

Sarwititi Sarwoprasodjo Anna Fatchiya2

Anna Fatchiya2