- Department of Communication Science, Faculty of Social and Political Science, Universitas Singaperbangsa Karawang, Karawang, Indonesia

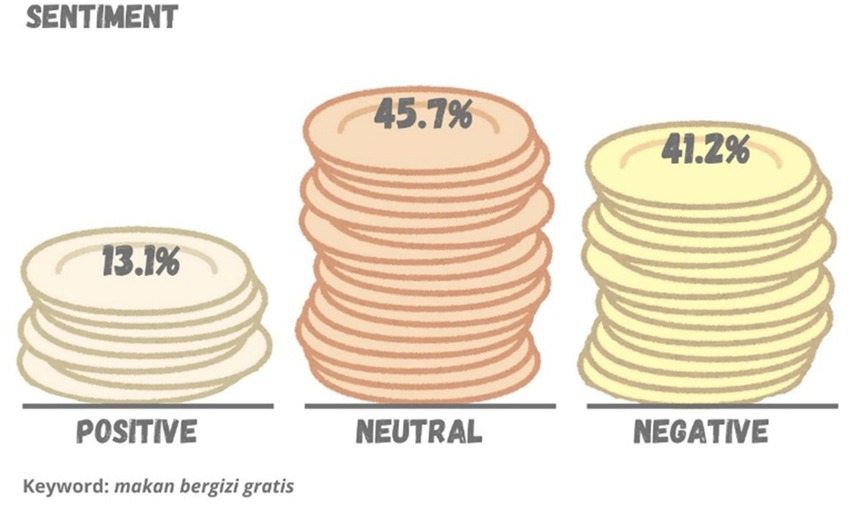

Prabowo Subianto, the President of Indonesia, has recently launched a flagship initiative known as Makan Bergizi Gratis (MBG), like a free school meals program, as part of his political campaign for the 2024 presidential election. This study using sentiment analysis of 4,041 news reports in social media posts collected with Talkwalker analytic tools between 6 and 12 January 2025. In the first week, social media sentiment was predominantly negative, with 41.2% expressing unfavorable views, 13.1% positive sentiments, and 45.7% neutral responses. A key issue in the program’s implementation is equivocal communication, amid the community’s demand for clear information.

1 Introduction

A program similar to the free meals school called Makan Bergizi Gratis (MBG) has been officially implemented since Monday, 6 January 2025 in Indonesia. The MBG is the flagship program of Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto. Until this time, his popularity and electability increased. President Prabowo’s MBG program is considered pro-people because it targets school students in both urban and rural areas. This program aims to improve the nutritional status of students by providing nutritious food according to the daily Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA) standard. Unlike in previous Indonesian nutrition policies that primarily focused on supplementation or conditional cash transfers, MBG represents the first attempt at universal free meals at a national scale.

Prabowo asserted that the MBG program can enhance the regional economy. Its demand for substantial food quantities is expected to boost economic activity and increase sales of essential commodities like rice, fish, eggs, and vegetables in various regions. President Prabowo’s nutrition politics aimed to target many Indonesian students, benefiting farmers and ranchers and helping parents improve their children’s nutrition. The MBG program represents an aspect of Prabowo’s nutrition politics, which seeks to enhance the population’s nutritional status through strategic use of power and policy instruments (Danforth, 1999). The anticipated outcome is improved welfare for farmers, ranchers, and rural communities.

The targets the number of beneficiaries of this program to be around 82.9 million people. In 2025, the government targets around 40%; in 2026–2028, around 80%; and in 2029, 100%. Research has shown that MBG programs significantly improve students’ academic achievement (Gutierrez, 2021), fitness in the learning process (Farris et al., 2014), participation and learning outcomes (Ruffini, 2022), and benefit students’ social and emotional aspects (Zuercher et al., 2022).

Internationally, free school meal programs have been implemented in various forms, notably in the Nordic countries, the United Kingdom, the United States, Brazil, and India. Evidence shows that such programs can enhance diet quality, participation, and academic achievement (Cohen et al., 2021; Ruffini, 2022; Lundborg et al., 2022). For example, Finland has provided free school meals since 1945, and Sweden since 1948, with systematic integration into education law and nutritional guidelines (Juniusdottir et al., 2018).

In India, the Mid-Day Meal Scheme has been associated with improved attendance and child health outcomes (Gharge et al., 2024; Global Child Nutrition Foundation (GCNF), 2024). The UK also holds a MBG program. Previous research indicates that Peer Effects are an effective strategy to support MBG acceptance in schools (James, 2012). The role of peers is crucial in increasing student participation in MBG. Studies show peers significantly influence participation in free school meal programs (Holford, 2015). It is important to note, however, that these examples represent general models of free school meals, whereas MBG is Indonesia’s localized adaptation that requires separate evaluation. Thus, while global evidence provides valuable comparisons, it cannot be assumed that MBG mirrors the outcomes of other countries.

Challenges often arise in implementing the MBG program across countries. Budgetary constraints are evident in the U.S. National School Lunch Program (NSLP), where political debates on funding impact the social subsidy budget and program implementation. In Brazil, financial limitations have led to substituting meals in the Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar (PNAE) with cheaper items, reducing nutritional value (Kitaoka, 2018). In India, the Mid-Day Meal Scheme (MDMS) faces challenges in food distribution to remote areas with inadequate transport infrastructure (Singh et al., 2014).

Despite the scale of MBG, research on its implementation remains scarce, with most discussions limited to policy announcements or media reports. Existing literature on free school meals has emphasized health and educational outcomes (Farris et al., 2014; Zuercher et al., 2022), but little attention has been paid to how such programs are socially interpreted and communicated in their early stages. In Indonesia, no study has yet examined public discourse around MBG, particularly during its critical launch phase. This presents a gap in both the nutrition policy literature and communication studies, as the social reception of large-scale welfare programs is often as important as their technical design (Domina et al., 2024).

To address this gap, the present study employs Weick’s (2015) theory of Equivocal Communication. Equivocality refers to the coexistence of multiple, and sometimes conflicting, interpretations of a single policy event (Fowler, 2021). In the case of MBG, equivocality emerges when the program is framed simultaneously as a nutrition intervention, an economic stimulus, and a political flagship, generating diverse public responses. By applying this framework, the study contributes novelty to the literature by highlighting how communication processes shape the social meaning of nutrition policies, especially in contexts where policy visibility intersects with political symbolism (Rothbart et al., 2023; Localio et al., 2024).

This study addresses research questions on the implementation of Indonesia’s MBG program during its initial week, informed by news issue mapping, and examines public sentiment. Given the program’s novelty in Indonesia, research on its implementation is limited. Using a communication perspective based on the theory of Equivocal Communication (Weick, 2015), this exploratory research aims to elucidate the equivocality and social impact of the MBG program’s implementation during the first week after its launch by President Prabowo.

2 Data and method

This exploratory study had two stages using sentiment analysis method. The method was guided by Weick’s (2015) theory of Equivocal Communication, which emphasizes how multiple interpretations of a single event arise in organizational and social contexts. Sentiment analysis was used here as a proxy to capture different orientations of public responses (positive, neutral, negative) and thereby identify areas of equivocality in the launch of the MBG program.

Through natural language processing (NLP) techniques, it analyzed news reports and social media conversations with the keyword “makan bergizi gratis.” Researchers used Talkwalker analytic tools, to streamline data processing for thousands of news articles and social media conversations. It used natural language processing (NLP) techniques from data-driven crawling for sentiment determination and analysis. The first stage analyzed news sentiment. Data-driven crawling was used on 4,041 news reports from January 6–12, 2025. Results showed 396 news articles (9.8%) with positive sentiments, 3,548 (87.8%) neutral, and 97 (2.4%) negative.

The skewed distribution reflects two factors: (i) Twitter/X dominates political discourse in Indonesia (Lim, 2017), and (ii) Talkwalker’s crawler prioritizes open-access platforms, potentially underrepresenting closed Facebook groups or private messaging channels. While the data show Twitter’s centrality, they indicate platform bias that must be acknowledged. Talkwalker generated “potential reach” metrics from cumulative follower counts of accounts producing the analyzed posts. This metric estimates message visibility but does not equal actual exposure, as it assumes all followers see each post. The 6.8 billion potential reach figure should be interpreted cautiously, as it likely overestimates exposure.

Researchers then cleaned the 97 negative sentiment news manually through content analysis, considering topic relevance and removing duplicates. This resulted in 77 negative sentiment news, which were used to map issues in the MBG program implementation. The second stage analyzed social media sentiment. It involved mining conversation data from Twitter (98.36%), Facebook (1.37%), and YouTube (0.27%) through data-driven crawling. 138,301 posts related to “makan bergizi gratis” were found from January 6–12, 2025, with a potential reach of 6,849,135,364 people. Talkwalker tools then processed these conversations and performed sentiment analysis categorizing them as positive, neutral, or negative.

Several steps were taken to ensure accuracy and replicability: First, keyword standardization. Only posts and articles containing the exact phrase “makan bergizi gratis” were included, reducing noise from unrelated discussions. Second, manual validation. Negative-sentiment news items were cross-checked by two coders, while social media sentiment classifications were validated with random sampling. Third, documentation: All procedures—including search terms, time windows, and coding protocols—were documented to facilitate replication.

Several limitations must be noted. First, sentiment analysis categorizes text into positive, neutral, or negative polarity but may oversimplify nuanced expressions such as sarcasm or ambivalence, which are central to equivocal communication (Bavelas et al., 1993). Manual validation partially addressed this, but equivocality cannot be fully captured by polarity labels alone. Second, reliance on Talkwalker constrains transparency in algorithmic classification, as the proprietary model does not disclose training data or cultural adaptation for Indonesian language. Third, the platform distribution highlights over-reliance on Twitter, potentially overlooking important discourse occurring in offline or less-accessible online spaces. These limitations do not invalidate the findings but frame them as indicative rather than exhaustive.

3 Results

The MBG program’s implementation was messy in the first week after kick-off, as evident in various news reports. A summary of Indonesian mass media news revealed several MBG problems during January 6–12, 2025. Using the Talkwalker website with the search keyword “makan bergizi gratis,” out of 4,041 news reports, 97 (2.4%) had negative sentiment. The 97 negative sentiment news items were cleaned by adjusting titles, considering relevance to MBG implementation and removing duplicates. This resulted in 77 negative sentiment news items for January 6–12, 2025. A list was created from these items, which were then read and analyzed. Subsequently, a typification of MBG implementation problems was conducted. The typology of these issues is as follows.

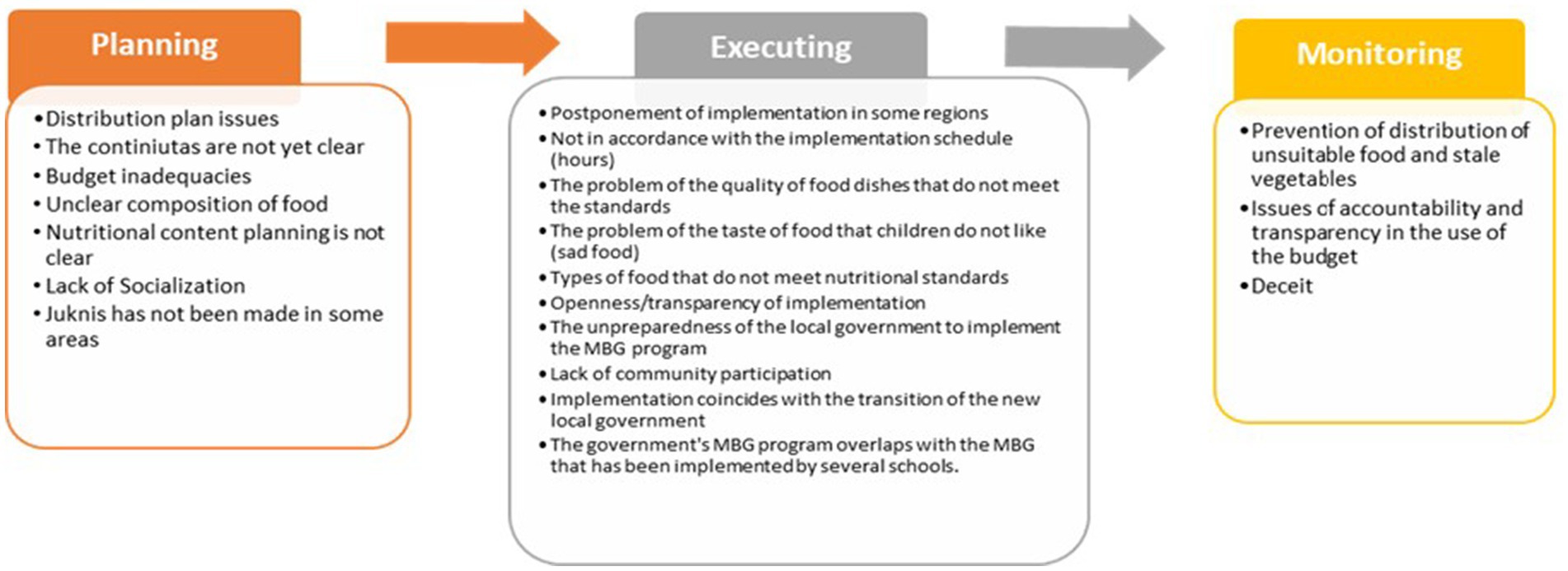

Figure 1 shows three types of problems in the implementation of the MBG program in the first week: planning, implementation, and monitoring. The results of the sentiment analysis show that in the planning problem, the MBG program does not have a mature plan. From the problems that arise in the field, there are several aspects that need to be planned, namely rules or technical instructions, food and nutrition standards, human resources and distribution systems, and budgets. Even after 1 week of the MBG program kicking off, the budget and source values remain uncertain. For example, the initial implementation of the MBG program tended to be rushed and unprepared (Ajeng and Aidil, 2025).

Figure 1. Issues typology in the MBG program in the first week. Source: Sentiment Analysis Processing News from Mass Media.

Due to lack of preparedness, many problems occur during executing. Consequently, MBG implementation has been postponed in several regions. Many beneficiary students disliked the MBG menu and considered it sad. For example, several provincial media outlets reported that MBG Implementation Postponed (Hendra, 2025). Furthermore, nutritional standards and food menus are unclear. This ambiguity makes it difficult to evaluate the MBG program’s effect on students’ nutritional fulfillment. An unclear division of roles can be seen in monitoring problems. Some food items were found unsuitable for consumption due to staleness in some areas. Additionally, scams affecting victims have emerged. According to program monitoring results, based on news reports, the MBG program was in disarray (Panangian, 2025).

In addition to the above problems, excesses from MBG programs exist in the environmental and business sectors. MBG programs produce substantial waste and pollute the environment. Worse, the implementation of the MBG program in the region uses plastic packaging, potentially generating large plastic waste. Regarding business impact, the MBG program quieted canteen merchandize around schools. Traders in the canteen and nearby areas revealed this, complaining that the program decreased the number of students buying goods.

The messy implementation of MBG in the first week was illustrated through public opinion on social media. From the results of public sentiment on social media using Talkwalker from January to 6–12, 2025, it was found that as many as 13.1% of people’s posts on social media had positive sentiments, and as many as 41.2% of people had negative sentiments toward the implementation of MBG. Meanwhile, as many as 45.7% of the posts had a neutral sentiment. These data indicate that more posts on social media have negative sentiments than positive ones, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Indonesian Netizens’ sentiment toward the MBG program in the first week. Source: Data Processing of Talkwalker Tools.

Figure 2 demonstrates that there was a significant level of negative sentiment at the onset of the MBG implementation, which surpassed the positive sentiment within the community. This phenomenon can be attributed to the public’s perception during the initial week, which did not align with the anticipated outcomes of the MBG implementation. The program was relatively novel in Indonesia and lacked meticulous preparation, while the target demographic for free meals was substantial, encompassing 82.9 million individuals, nearly equivalent to the total population of Germany.

The findings of this study indicate that numerous challenges were encountered in the execution of the MBG program, contributing to the negative sentiment within the community. Consequently, the anticipated social impact of the MBG program may not be fully realized, potentially hindering the development of Indonesian human resources and the welfare of rural communities (Sarjito, 2024). Ambiguity has emerged as a predominant issue on social media concerning the MBG program. Social media platforms play a crucial role in influencing the social order and sentiment of the community. The intrinsic nature of social media facilitates the swift dissemination of opinions, rendering it a potent tool for assessing public sentiment toward political agendas. Content shared by individuals on social media serves as a reflection of public sentiment (Groshek and Al-Rawi, 2013), and its reach exerts a social impact on society.

These patterns suggest that public sentiment leaned more negative than positive in the initial week, particularly due to the mismatch between expectations and the reality of large-scale rollout. However, it should be noted that the typology of problems was derived exclusively from negative news reports (n = 77). This analytical choice foregrounds implementation challenges but risks overemphasizing negative aspects while underrepresenting supportive or neutral perspectives. Positive news (n = 396) typically highlighted political commitment and potential long-term benefits, whereas neutral items (n = 3,548) often relayed government press releases. The focus on negative reporting should therefore be interpreted as an intentional lens to map emerging issues rather than a comprehensive assessment of all sentiments.

4 Discussion

The early implementation of the Makan Bergizi Gratis (MBG) program demonstrates how unclear or inconsistent communication produces equivocality (Weick, 2020), manifested as uncertainty, complication, and ambiguity. However, empirical findings indicate that equivocality alone cannot fully explain the prevalence of negative sentiment. For example, while ambiguity regarding nutritional standards and per-portion budgets (IDR 10,000 in some provinces versus IDR 15,000 in Papua) clearly created confusion, the 41.2% negative sentiment on social media also reflected political contestation and economic discontent. Canteen vendors framed MBG as a threat to their livelihoods, while opposition narratives amplified logistical shortcomings as evidence of weak government capacity. This suggests that public discourse around MBG is shaped by an interaction of equivocal communication, political framing, and economic interests.

A more nuanced linkage between sentiment analysis and equivocality is therefore necessary. Equating negative sentiment directly with equivocality risks overgeneralization. Some negative expressions may reflect distrust in government credibility, ideological resistance, or dissatisfaction with economic impacts rather than confusion over information. Sentiment polarity should thus be treated as an indicative proxy of interpretive struggles, not a definitive measure of equivocality (Daft and Lengel, 1983; Gayo-Avello, 2013). Recognizing these limitations adds analytical sharpness and avoids oversimplification.

At the same time, the issue typology derived from 77 negative news reports—planning, implementation, and monitoring—corresponds with Weick’s argument that equivocality emerges when multiple stakeholders interpret a policy differently. For instance, divergent expectations over the inclusion of milk in the MBG package highlight how incomplete information fosters conflicting narratives. Yet, beyond organizational ambiguity, political communication processes also influenced perceptions. Media outlets with varying editorial lines amplified either supportive or critical voices, shaping selective sensemaking in the public sphere. This resonates with research on framing and agenda-setting, which shows how political actors and media bias influence public evaluations of policy (Entman, 1993; Paricio Esteban et al., 2020).

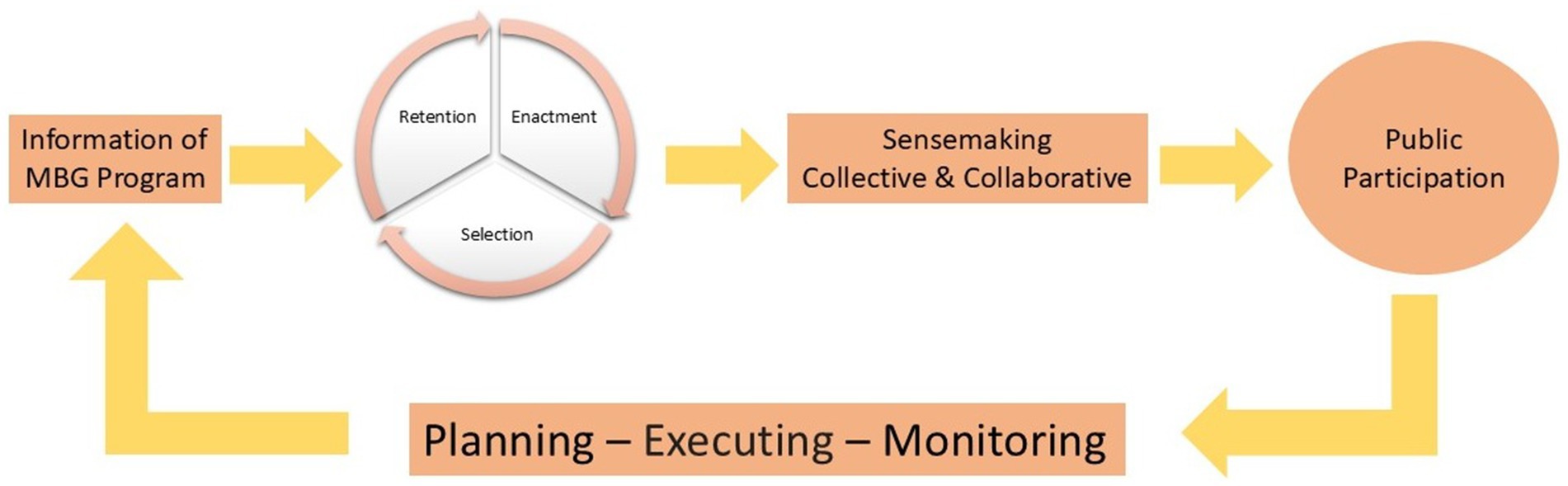

Weick’s three stages of organizing—enactment, selection, and retention (Griffin, 2019)—can be traced in MBG’s rollout. Enactment occurred when the public received conflicting signals about program content and budgets. Selection followed as individuals filtered information through personal experience, media framing, or political allegiance. Retention took place when certain narratives (e.g., “menus are inadequate,” “budgets are unclear”) dominated media cycles and social media conversations, reinforcing collective distrust. This empirical pattern both supports Weick’s framework and extends it by showing how political contestation accelerates the retention of negative narratives.

Importantly, the Indonesian case connects with international experiences of free school meal programs. In the United States, negative feedback on the National School Lunch Program has prompted adjustments in menu design and nutrition standards (Cohen et al., 2021). In the United Kingdom, public debates on Universal Infant Free School Meals influenced funding priorities and peer acceptance strategies (Holford, 2015). These examples show how governments can use sentiment monitoring not only to evaluate policy acceptance but also to recalibrate implementation in response to public concerns. Positioning MBG within this global landscape enriches the analysis and highlights lessons for Indonesia.

Figure 3 shows that these three stages can create sensemaking (Dougherty and Smythe, 2004) for the community, both collective and collaborative sensemaking, so that the community not only understands the MBG program but also receives, interprets information, and even participates in supporting the MBG program. Sensemaking forms the basis of social actions. Sensemaking refers to meanings that materialize to create identity. Cultural narratives help actors make sense by providing them with a framework for understanding a program (Zanin et al., 2020). Collective perceptions of MBG programs can significantly influence the actions of a group, thereby mitigating ambiguous or negative narratives and reducing cynicism within the community (Vardaman et al., 2023).

Figure 3. Information processing model in increasing public participation in MBG program. Source: Developed from Karl Weick’s equivocality theory.

Sensemaking Collective & Collaborative activities can encourage community participation in the planning, implementation, and monitoring processes with the aim of reducing problems in the planning, implementation, and monitoring of MBG programs. Community involvement in a democratic system is important in determining public policies that involve many actors. Moreover, Indonesia has varied sociocultural diversity, so the level of public policy acceptance varies from region to region. The public participation approach, based on local wisdom, is relevant and urgent for ensuring the success of the MBG program.

Sensemaking activities are integral to public communication, underscoring their significance in facilitating communities’ commitment to collective action based on shared understanding and principles (Shaw, 2021). When community members actively engage in planning and decision-making processes, they tend to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the goals and objectives of initiatives, such as the MBG program, thereby enhancing program implementation and sustainability. Moreover, local knowledge and cultural context are pivotal in fostering the public acceptance of policies across various regions of Indonesia. Research indicates that the adoption of culturally relevant strategies is essential for ensuring effective public participation in policymaking (Blomkamp, 2021). By integrating local insights into program design, policymakers can increase the likelihood of public acceptance, thereby mitigating potential resistance to the program.

5 Conclusion

The implementation of MBG during its first week shows how ambiguous communication generates equivocality and contributes to negative public sentiment. This study demonstrates the value of applying Weick’s theory of equivocality beyond organizational contexts to large-scale public nutrition policy, extending the framework into social policy communication. The research links sentiment analysis with equivocal communication, showing how public responses to MBG reveal multiple conflicting interpretations of the policy. The study contributes to communication and policy literature by highlighting equivocality’s role in shaping public trust in government-led nutrition programs. Practically, the findings emphasize designing communication strategies that reduce equivocality in planning, implementation, and monitoring. Clear guidelines, transparent budget information, and participatory menu design are recommended to build credibility and community ownership. These steps can help transform negative perceptions into constructive engagement.

This study has limitations. Sentiment analysis captures polarity but cannot fully disentangle political, ideological, or economic factors behind negative sentiment. Twitter-dominant data may underrepresent discussions in other spaces. Future research should combine sentiment analysis with qualitative methods and explore comparative perspectives from other free school meal programs internationally. In conclusion, the MBG case shows that large-scale nutrition policies require logistical readiness and robust communication strategies to mitigate ambiguity and foster public trust. Strengthening collective sensemaking through culturally grounded communication is key to ensuring program sustainability and legitimacy.

Data availability statement

The social media data analysed in this study (from Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube) were accessed in full compliance with each platform’s Terms of Use and all relevant institutional and national ethical guidelines. In accordance with institutional and national guidelines, no personal, sensitive, or identifiable private information was collected, stored, or reported. Due to the terms and conditions of the platforms, the raw datasets cannot be publicly shared. However, the code used for data collection and analysis and the aggregated data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human data in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not required, for either participation in the study or for the publication of potentially/indirectly identifying information, in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The social media data was accessed and analyzed in accordance with the platform’s terms of use and all relevant institutional/national regulations.

Author contributions

HS: Validation, Resources, Project administration, Data curation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Software.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The author express their gratitude to their colleagues at Universitas Singaperbangsa Karawang for their valuable input and suggestions, which have contributed significantly to the development of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The author(s) verify and take full responsibility for the use of Generative AI in the preparation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used Talkwalker was used to in the context of processing extensive volumes of news and numerous social media posts, the utilization of Talkwalker offers a more time-efficient alternative compared to traditional tools. Nevertheless, the application of Talkwalker is subject to regulation and is guided by the author’s directives. The author(s) are fully responsible for the accuracy and content of the manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ajeng, N., and Aidil, M. (2025). Makan Bergizi Gratis Perdana Sasar 600 Ribu Orang, Jauh Dari Target Awal - Apakah Program Ini Terlalu Tergesa-Gesa? BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/indonesia/articles/cx2ywv21708o (Accessed January 6, 2025).

Bavelas, J. B., Black, A., Chovil, N., and Mullett, J. (1993). Equivocal communications. Can. J. Commun. 18:1–6. doi: 10.22230/cjc.1993v18n1a721

Blomkamp, E. (2021). Systemic design practice for participatory policymaking. Policy Des. Pract. 5, 12–31. doi: 10.1080/25741292.2021.1887576

Cohen, J. F. W., Hecht, A. A., McLoughlin, G. M., Turner, L., and Schwartz, M. B. (2021). Universal school meals and associations with student participation, attendance, academic performance, diet quality, food security, and body mass index: a systematic review. Nutrients 13:911. doi: 10.3390/nu13030911

Daft, R., and Lengel, R. (1983). Information richness. A new approach to managerial behavior and organization design. Res. Organ. Behav. 6:73.

Danforth, M. E. (1999). Nutrition and politics in prehistory. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 28, 1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.28.1.1

Domina, T., Clark, L., Radsky, V., and Bhaskar, R. (2024). There is such a thing as a free lunch: school meals, stigma, and student discipline. Am. Educ. Res. J. 61, 287–327. doi: 10.3102/00028312231222266

Dougherty, D., and Smythe, M. J. (2004). Sensemaking, organizational culture, and sexual harassment. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 32, 293–317. doi: 10.1080/0090988042000275998

Entman, R. (1993). Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 43, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Farris, A. R., Misyak, S., Duffey, K. J., Davis, G. C., Hosig, K., Atzaba-Poria, N., et al. (2014). Nutritional comparison of packed and school lunches in pre-kindergarten and kindergarten children following the implementation of the 2012-2013 National School Lunch Program Standards. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 46, 621–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.07.007

Fowler, L. (2021). How to implement policy: coping with ambiguity and uncertainty. Public Adm. 99, 581–597. doi: 10.1111/padm.12702

Gayo-Avello, D. (2013). A meta-analysis of state-of-the-art electoral prediction from twitter data. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 31, 649–679. doi: 10.1177/0894439313493979

Gharge, S., Vlachopoulos, D., Skinner, A. M., Williams, C. A., Revuelta Iniesta, R., and Unisa, S. (2024). The effect of the mid-day meal programme on the longitudinal physical growth from childhood to adolescence in India. PLoS Glob. Public Health 4, 1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0002742

Global Child Nutrition Foundation (GCNF). (2024). 2024 global survey of school meal programs. Seattle, Washington: Global Child Nutrition Foundation (GCNF).

Griffin, E. (2019). A first look at communication theory. Universitas Wheaton. 10th Edn. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

Groshek, J., and Al-Rawi, A. (2013). Public sentiment and critical framing in social media content during the 2012 U.S. presidential campaign. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 31, 563–576. doi: 10.1177/0894439313490401

Gutierrez, E. (2021). The effect of universal free meals on student perceptions of school climate: evidence from New York City. EdWorkingPaper 21–430 21, 1–59. doi: 10.26300/mc-

Hendra, Y. (2025). Sudah 10 Hari, MBG Di Padang Masih Mundur Karena Peralatan Dapur. Media Indonesia. Available online at: https://mediaindonesia.com/nusantara/735080/sudah-10-hari-mbg-di-padang-masih-mundur-karena-peralatan-dapur (Accessed January 16, 2025).

Holford, A. (2015). Take-up of free school meals: price effects and peer effects. Economica 82, 976–993. doi: 10.1111/ecca.12147

James, J. (2012). Peer effects in free school meals: Information or stigma? San Domenico di Fiesole: Eui.Eu.

Juniusdottir, R., Hörnell, A., Gunnarsdottir, I., Lagstrom, H., Waling, M., Olsson, C., et al. (2018). Composition of school meals in Sweden, Finland, and Iceland: official guidelines and comparison with practice and availability. J. Sch. Health 88, 744–753. doi: 10.1111/josh.12683

Kitaoka, K. (2018). The national school meal program in Brazil: a literature review. Jap. J. Nutr. Dietet. 76, S115–S125. doi: 10.5264/eiyogakuzashi.76.S115

Lim, M. (2017). Freedom to hate: social media, algorithmic enclaves, and the rise of tribal nationalism in Indonesia. Crit. Asian Stud. 49, 411–427. doi: 10.1080/14672715.2017.1341188

Localio, A. M., Knox, M. A., Basu, A., Lindman, T., Pinero Walkinshaw, L., and Jones-Smith, J. C. (2024). Universal free school meals policy and childhood obesity. Pediatrics 153, 1–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2023-063749

Lundborg, P., Rooth, D.-O., and Alex-Petersen, J. (2022). Long-term effects of childhood nutrition: evidence from a school lunch reform. Rev. Econ. Stud. 89, 876–908. doi: 10.1093/restud/rdab028

Panangian, M. R. (2025). Menyeruak Bau Rasuah Makan Bergizi Gratis, Ompreng Mau Diseleweng. Inilah.Com. Available online at: https://www.inilah.com/bau-rasuah-makan-bergizi-gratis (Accessed January 12, 2025).

Paricio Esteban, M. P., López, M. P., and Almerich, S. F. (2020). Public relations and campaigns about road safety and drug use: efficacy assessment of campaigns in audiovisual media. Comunicacao e Sociedade 2020, 127–150. doi: 10.17231/comsoc.0(2020).2744

Rothbart, M. W., Schwartz, A. E., and Gutierrez, E. (2023). Paying for free lunch: the impact of CEP universal free meals on revenues, spending, and student health. Educ. Finance Policy 18, 708–737. doi: 10.1162/edfp_a_00380

Ruffini, K. (2022). Universal access to free school meals and student achievement. J. Hum. Resour. 57, 776–820. doi: 10.3368/jhr.57.3.0518-9509r3

Sarjito, A. (2024). Free nutritious meal program as a human resource development strategy to support national defence. Int. J. Admin. Bus. Organ. 5, 129–141. doi: 10.61242/ijabo.24.454

Shaw, L. C. (2021). From sensemaking to sensegiving: a discourse analysis of the scholarly communications community’s public response to the global pandemic. Learned Publ. 34, 6–16. doi: 10.1002/leap.1350

Singh, A., Park, A., and Dercon, S. (2014). School meals as a safety net: an evaluation of the midday meal scheme in India. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 62, 275–306. doi: 10.1086/674097

Vardaman, J. M., Maher, L. P., Sterling, C., Allen, D. G., and Dhaenens, A. (2023). Collective friend group reactions to organizational change: a field theory approach. J. Organ. Behav. 44, 1094–1108. doi: 10.1002/job.2706

Weick, K. E. (2015). Karl E. WEICK (1979), the social psychology of organizing, Second Edition. Paperback: 294 pages Publisher: McGraw-Hill (1979) language: English ISBN: 978-0075548089. Management 18, 189–193. doi: 10.3917/mana.182.0189

Weick, K. (2020). Sensemaking, organizing, and surpassing: a handoff*. J. Manag. Stud. 57, 1420–1431. doi: 10.1111/joms.12617

Zanin, A. C., Kamrath, J. K., Ruston, S. W., Posteher, K. A., and Corman, S. R. (2020). Labeling avoidance in healthcare decision-making: how stakeholders make sense of concussion events through sport narratives. Health Commun. 35, 935–945. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2019.1598742

Zuercher, M. D., Cohen, J. F. W., Hecht, C. E., Hecht, K., Ritchie, L. D., and Gosliner, W. (2022). Providing school meals to all students free of charge during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: challenges and benefits reported by school foodservice professionals in California. Nutrients 14, 1–20. doi: 10.3390/nu14183855

Keywords: equivocal communication, free meals school, MBG program, nutrition policy, sensemaking, sentiment analysis

Citation: Sianturi HRP (2025) Politics on a plate: equivocal communication in Indonesian presidential nutrition policy. Front. Commun. 10:1612652. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1612652

Edited by:

Nilesh Chandrakant Gawde, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, IndiaReviewed by:

Fotarisman Zaluchu, Universitas Sumatera Utara, IndonesiaAthik Hidayatul Ummah, Universitas Islam Negeri Mataram, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Sianturi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hendry Roris P. Sianturi, aGVuZHJ5LnJvcmlzQGZpc2lwLnVuc2lrYS5hYy5pZA==

Hendry Roris P. Sianturi

Hendry Roris P. Sianturi