- College of Arts-King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

The emergence of transnational cinema as a dynamic force in modern filmmaking has resulted in the promotion of cultural interaction and the formation of global narrative trends. This systematic study, which is driven by the PRISMA framework, is a synthesis of contemporary scholarly viewpoints on how transnational cinema acts as a cultural bridge. The purpose of this study is to synthesize the findings from a carefully selected sample of fifteen research papers, with special emphasis placed on stringent inclusion–exclusion criteria and the utilization of the PRISMA methodology. The sample of articles utilized in this study spans the years 2006 to 2023. The review sheds light on a variety of influences that have influenced the shifting viewpoints on transnational cinema. The practice of transnational cinema encourages cultural hybridity while simultaneously challenging established national identities. One of the most important factors in growing the worldwide effect of films is the role that co-productions and digital platforms play. According to the findings, transnational cinema is facilitating a transformation in the manner in which cultural identities are shown and understood. The blending of different film techniques and the telling of stories from other cultures contributes to the enrichment of global cinema and defies the rigid definitions of national industry. Several topics, including hybridity, diasporic identity, cross-border cooperation, and worldwide audience reception, are investigated in this research. Through an examination of several studies, this study sheds light on the primary tendencies and debates that are characteristic of the modern international cinematic discourse. In further investigations, the phenomena of the digital revolution and the impact it has had on the process of reframing global narratives need to be the primary focus.

Introduction

Cinema has historically been regarded as a powerful medium for the global exchange of narratives, the formation of identities, and the spread of cultural concepts (Ezra and Rowden, 2006a, 2006b; Naficy, 2001). In recent decades, the idea of transnational Cinema has gained significant traction. This expression denotes cinematic works that surpass national confines regarding their creation, dissemination, and audience reception (Higbee and Lim, 2010). This phenomenon illustrates broader trends of globalization, migration, and technological advancement, each contributing to a redefinition of the presentation and consumption of narratives within the film industry.

Globalization has emerged as the prevailing trend shaping the future in recent years, leading to the rise of cultural globalization. The notion of transnationalism is seen as a practical and instinctive approach to depicting global collaboration and cultural exchanges. Cross-cultural and transnational co-productions have emerged as the prevailing trend in the film and television industry across multiple nations, driven by the necessity to captivate global audiences and the impact of diverse cultural policies (Ma and Wang, 2024).

As scholars endeavoured to transcend the limitations of “national cinema” frameworks, which often perpetuated essentialist notions of cultural identity (Higson, 2005) transnational Cinema emerged as a significant focus in the early 2000s. This advancement emerged as scholars endeavoured to transcend the confines of “national cinema”. “Transnational cinema, conversely, underscores the concepts of fluidity, hybridity, and collaboration.” across international borders. R Ezra and Rowden (2006a) describes it as “a cinema of globalization, “and it exemplifies the “deterritorialized” aspect of contemporary cultural production, which involves the participation of filmmakers, funders, and audiences from several different countries. According to Appadurai (1996) this shift reflects more considerable sociopolitical transformations, such as postcolonial diasporas, economic globalization, and digital streaming platforms that democratize access to global narratives.

The discourse around transnational film has transitioned from a limited emphasis on co-productions to a broader framework including cultural diplomacy, circulation networks, and curatorial dynamics. While Falicov (2012) attacks the Ibermedia program for serving primarily as a public relations instrument for Spain rather than a venue for fair cinematic interchange. Campos (2016) and Amiot-Guillouet and Aguilar (2019) emphasize that European-Latin American partnerships often depend on the festival circuit for exposure, yet these venues may perpetuate existing imbalances. Sedeño Valdellós (2013) underscores the significance of worldwide film festivals in constructing a “art cinema” identity that promotes certain aesthetic and cultural anticipations. Elsaesser (2015) contends that festivals, particularly in the digital era, have emerged as crucial organizations in delineating the parameters of global or international cinema. These works together elucidate the complex and sometimes contentious function of cultural bridges in international cinema, extending beyond simple production connections, therefore warranting a concentrated examination of significant contributions in this domain.

Transnational film historically originated from the aftermath of geopolitical realignments following World War II. The influence of the French New Wave on Asian directors like Akira Kurosawa, the collaborations between European and Latin American filmmakers in the 1960s, and the emergence of diasporic directors such as Mira Nair (Monsoon Wedding, 2001) illustrate early manifestations of this tendency. Nonetheless, the 21st century has experienced a significant surge in international Cinema, propelled by streaming behemoths such as Netflix and Amazon Prime, emphasizing narratives with global resonance—from South Korea’s Parasite (2019) to Partida (2019). These films transcend borders and dismantle them, encouraging audiences to confront “otherness” in manners that contest ethnocentric perspectives (Shohat and Stam, 2018).

Differentiate between Crossover Cinema and transnational cinema, and explain how they combine cultures from the outset in their production and storyline (Khorana, 2013). International audiences see these films. This differs from transnational cinema, which examines how migration and globalization have shaped films after WWII. Crossover cinema better depicts worldwide filmmaking, illustrating how other cultures, especially Westerners, shape movies. Research on Eastern Cultural Symbols and Identity in Western Films, citing Memoirs of a Geisha (2004), highlights challenges in transnational Cinema, including oversimplification of symbols, identity conflicts from casting choices, and historical inaccuracies (Wang and Yeh, 2005).

The discussion of international cinema has evolved from production-centric frameworks to more dynamic interpretations including circulation, representation, and curation. Elsaesser (2015) characterizes the digital-festival ecology as a crucial arena for negotiating cultural legitimacy, while Falicov (2012) faults institutional initiatives such as Ibermedia for promoting national branding masquerading as international collaboration. Campos (2016) and Amiot-Guillouet and Aguilar (2019) emphasize that festivals facilitate the exposure of Latin American film in European contexts, often perpetuating imbalanced power dynamics despite the facade of reciprocal cultural exchange. This study examines the cultural gatekeeping inherent in transnational cinema architecture, as highlighted by these studies, via a survey of the relevant literature.

Aim and purpose

The purpose of this research is to analyse the function that transnational cinema plays as a cultural conduit and how it is undergoing a fundamental transformation in its perspective on the movement of cultures all over the world. The objective of this study is to investigate three distinct topic areas: (1) how transnational cinema promotes cross-cultural conversation and hybridity; (2) the influence that digital platforms and worldwide distribution have on audience reception; and (3) the significance of cross-border collaboration in film production from 2006 to 2023. The major purpose is to present a complete synthesis of the research that has already been conducted and to elucidate the complex consequences that transnational cinema has on cultural hybridity, identity building, and global connectivity. Through the purpose of conducting systematic analysis and evaluating a curated selection of publications, the purpose of this study is to enhance the knowledge of prevalent themes, methodologies, and gaps in the current literature on transnational Cinema. Utilising a methodical strategy will allow for the successful completion of this task. The conduct of this study is necessary to guide the direction of future research, to influence the formulation of policies, and to facilitate interactions between international cinema organisations. The goal of this initiative is to support the development of strategies that are both focused and practical to facilitate significant cross-cultural interchange through the medium of cinema. With the use of the PRISMA technique, this review study intends to fulfill the pressing requirement for a thorough grasp of the subject matter. This will be accomplished by conducting a systematic examination of the existing research and literature on transnational cinema. Although this study aims to contemplate more extensive trends in transnational cinema, it recognizes that the conclusions derived from a limited but thematically focused set of studies are interpretive rather than definitive. The scope of systematic reviews is inherently limited by the rigorous inclusion criteria, and this limitation is further elaborated upon in the methodology and discussion sections.

RQ1: In what ways does transnational Cinema serve as a conduit for cultural interaction, and what shifting viewpoints characterize its influence on the exchange of global cultures?

RQ2: What defines transnational Cinema from selected articles?

Assumptions and justifications

Many assumptions were established to enhance the synthesis and analysis of the chosen studies. These assumptions are essential for ensuring a review process that is both logical and organized. Initially, it was anticipated that the selected studies would utilize fundamental concepts like “transnational cinema,” “cultural hybridity,” and “global film exchange” with a degree of uniformity. This assumption is based on the belief that academics in this field will conform to commonly recognized definitions and frameworks (Page et al., 2021). Despite terminological variations, the literature selection process successfully preserved thematic coherence and reduced inconsistencies by employing rigorous screening procedures and strict inclusion criteria.

Furthermore, the choice to incorporate studies released post-2006 stems from the belief that modern research reflects the latest advancements in transnational Cinema, especially regarding globalization and the expansion of digital media. The premise underpinning this decision was the inclusion of studies published after 2006. This assumption stems from the ever-evolving landscape of cinema studies, marked by the continual evolution of transnational film narratives and audience engagement driven by technological advancements, streaming services, and global collaborations. This research meticulously captures the latest insights into the function of transnational Cinema as a cultural conduit while examining the evolution of perspectives surrounding its significance through a thorough review of contemporary literature. This guarantees that the research yields the maximum amount of information attainable. Moreover, this methodology recognizes the dynamic nature of film production, distribution, and audience engagement, aligning with current discourse within the scholarly community and prevailing trends in the industry.

Since Western academic discourse has overlooked Asian, Latin American, and African film, this research highlights them. Research has decentered Euro-American perspectives and highlighted transnational cinema’s role in portraying postcolonial, diasporic, and hybrid identities beyond the Global North (Higbee and Lim, 2010; Smith, 2024). The selected studies show that transnational relationships enrich global cinematic stories and challenge Western film industry homogeneity.

Evaluation of assumptions

Pre-2006 research were eliminated to focus on global transnational film trends. Seminal foundational works (Appadurai, 1996; Naficy, 2001) were acknowledged as relevant but supplemented with recent research (Berry, 2010; Martin-Jones, 2020) to maintain theoretical continuity and address current cinematic issues. In the 21st century, world cinema as a cultural bridge was unified and updated using this sample method. This evaluation focused on works released between 2006 and 2023 for methodological rigor and significance to the worldwide film debate. After 2006, streaming platforms, digital production tools, and multinational alliances revolutionized global cinema (Lim, 2019; Page et al., 2021).

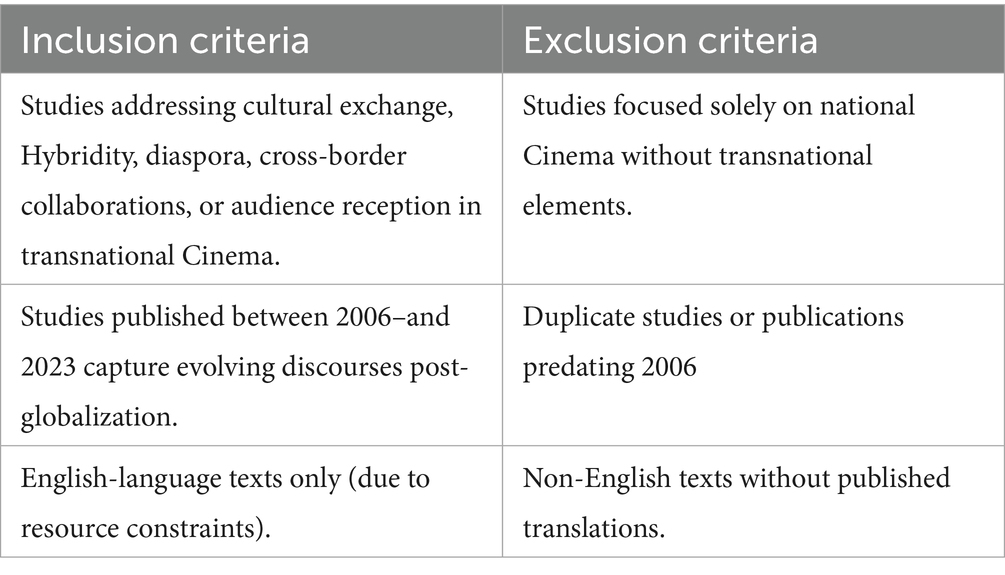

Google Scholar, JSTOR, and Taylor & Francis were the three specialized platforms that the researcher chose to use to conduct their research while considering the complexity and ongoing development of international cinema. The choice of academic databases—Taylor & Francis, JSTOR, and Google Scholar—was deliberate and strategic. These platforms provide peer-reviewed, high-quality scholarly output and are frequently used in systematic literature reviews. While this may exclude some grey literature or industry reports, it ensures academic credibility and consistency in analytical depth. The inclusion–exclusion criteria were grounded in the PRISMA protocol, with a focus on thematic relevance (hybridity, diaspora, co-production, audience reception), peer-review status, English-language accessibility, and methodological transparency. On the other hand, the selection criteria did not prohibit any age, gender, race, ethnicity, nationality, or language from being considered. The search was conducted using the following keywords: “transnational cinema,” “cultural hybridity in film,” “diasporic identity in cinema,” “cross-border film collaborations,” and “audience reception in global cinema. Taking into consideration the suggestions (Page et al., 2021), a review study was carried out by the researcher, and the PRISMA methodology was utilised. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study are stated in Table 1, which provides a summary of the requirements.

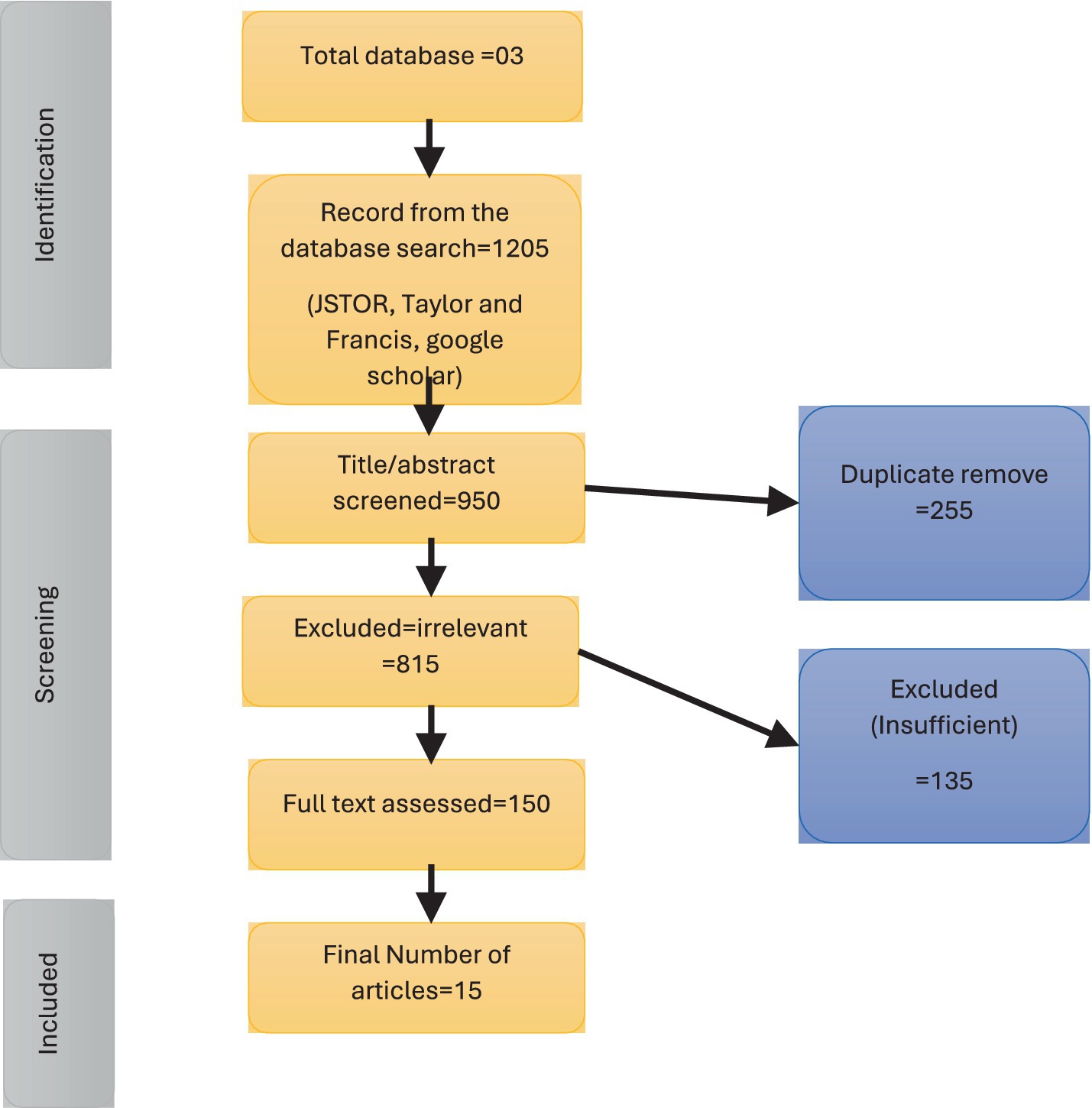

Utilizing the PRISMA screening, evaluation, and selection methodology, the researchers compiled 1,205 records from the designated databases. After eliminating duplicates, 950 articles were assessed for full-text accessibility (135). The researchers ultimately selected n = 15 articles that met the selection criteria. Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA flowchart detailing the article selection process.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standards have been adhered to whenever this review has been conducted. The technique consists of the following (Al Olaimat et al., 2025; Ben Romdhane et al., 2025; Jwaniat et al., 2025; Tahat K. M. et al., 2024):

As part of the identification process, a comprehensive search was conducted across a variety of academic databases, such as Taylor and Francis, JSTOR, and Google Scholar, using phrases such as “transnational cinema,” “cultural hybridity in film,” and “diasporic filmmaking”. During the screening process, duplicates were eliminated, and subsequent research were appraised based on the degree to which they were pertinent to transnational film. Those studies that focused on transnational cinema definition, production, audience reception, and cultural hybridity were taken into consideration for inclusion in the research.

The final decision was made based on the methodology’s rigour and the thematic relevance of the research. The systematic literature review method was the basis for this investigation. Studies based on reviews constitute a large portion of the existing body of research because they closely observe the ongoing trends and complexities in the topic being investigated (Chigbu et al., 2023). In addition, pertinent studies emphasize significant findings to identify gaps further and conduct an in-depth investigation of many areas of transnational Cinema (Al-Muhaissen et al., 2024; Attar et al., 2024; Tahat K. et al., 2024; Tahat et al., 2025). This comprehensive assessment covers academicians, filmmakers, and diasporic audiences from 15 studies. Transnational film artists and consumers are covered in Asia, Latin America, and Africa.

Despite the fact that the final cohort consisted of 15 studies, this was the outcome of the application of rigorous screening criteria that guaranteed the inclusion of only peer-reviewed, thematically aligned, and methodologically sound works. Nevertheless, the generalizability of the findings may be restricted by the limited scope of this dataset.

Summary of articles selected through PRISMA for review study

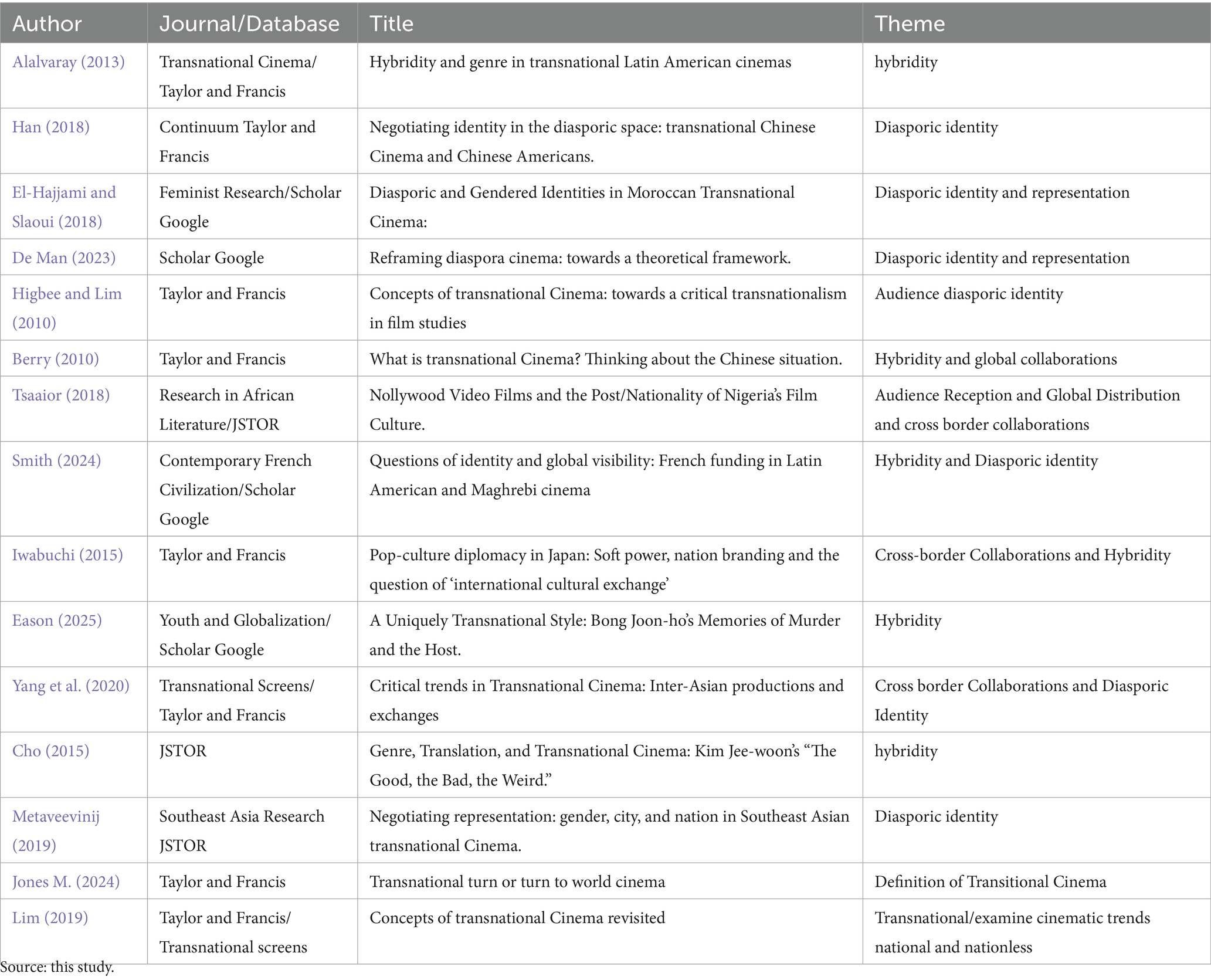

The goal of this review research is to explore academic works on transnational cinema, with a special emphasis on subjects such as hybridity, diasporic identity, audience reception, and collaborative efforts across international borders. Specifically, the research will focus on these topics. These authors are among those who have investigated the concepts of hybridity and international collaborations within the context of transnational film. Some of the authors who have done so are Alalvaray (2013) and Berry (2010), among others. The concepts of diasporic identity and representation are the subject of investigation by a variety of researchers. Researchers such as Han (2018), El-Hajjami and Slaoui (2018), and De Man (2023) are examples of those who have conducted this research. Both Higbee and Lim (2010) and Lim (2019) offer critical critiques of transnationalism within the context of the study of cinema studies. The definition of global film that Jones H. D. (2024) offers, on the other hand, is more comprehensive. The outcomes of research conducted by Iwabuchi (2015), Yang et al. (2020), and Tsaaior (2018) provide light on the value of cultural exchanges and international collaborations from a variety of perspectives. Cho (2015) and Eason (2025) both study the concept of hybridity in terms of genre and style within the framework of world cinema. Specifically, they focus on the hybridity of genres and styles. Smith (2024) and Megamerinid (2019) study the subjects of representation and global exposure about finance, gender, and identity across a range of transnational cinema industries. Specifically, they focus on the film industry.

Discussion

Definition of transnational cinema

The concept of transnational Cinema has evolved into a recognized area of research, surpassing traditional definitions of international film and national Cinema (Berry, 2010). The influence of globalization, neoliberalism, and post-Fordist production is evident, highlighting the evolving dynamics within film cultures and industries (Berry, 2010). Transnational Cinema includes diasporic Cinema, focussing on films created by and intended for migrant communities (Curry, 2016). This area has developed with broader intellectual movements emphasizing multivocality and a de-centred approach in cultural and critical race studies (Curry, 2016).

The term “transnational turn” is used in the field of film studies to refer to a movement that aims to interpret cinema in a context that goes beyond national boundaries. This approach emphasises the political dimensions of films as they connect with other cultures. This approach is crucial because it enables academics to connect many global cinemas and investigate topics like as migration and cultural exchange, which are typically ignored in conventional film studies that are centred on the Western world. With its focus on these political elements, the transnational shift offers fresh viewpoints on film from around the world and supports a variety of analytical methods. China’s cinematic goals and their effect on the United States have been the subject of the most recent study. This research has also investigated new phenomena such as slow film, eco cinema, and impoverished cinema, all of which demonstrate transnational links that do not correspond to national objectives (Lim, 2019). Certain scholars contend that the transnational turn represents a broader transition towards world cinema, aligning with politically engaged film studies methodologies (Martin-Jones, 2019). Certain academics believe the transnational shift is a global cinema movement aligned with politically active film studies (Martin-Jones, 2019). This change emphasizes cross-border film, concept, and minority voice mobility. World cinema, unlike non-Hollywood or international film, is a critical framework that challenges Western cinematic conventions by accepting other aesthetic practices, production circumstances, and geopolitical viewpoints. The linkage with politically active approaches emphasizes cinema’s fight against global inequality, colonialism, and cultural homogeneity. According to Martin-Jones (2019), the transnational shift pushes researchers to look beyond national production taxonomies to the intricate circulations of meaning, identity, and power across cinematic landscapes. This reorientation promotes a more inclusive and decolonial view of film cultures, especially when non-Western cinemas use hybrid forms, translocal partnerships, and grassroots distribution mechanisms.

Transnational film features collaborative productions, multilingual scripts, and themes that question national identity, unlike national cinema, which typically perpetuates state-centric narratives. However, Maghrebi-French co-productions complicate postcolonial and diasporic memory through hybrid narratives (Smith, 2024). French national film may promote cultural preservation. According to the selected literature, transnational cinema involves collaborative production, cross-cultural narratives, and global circulation. It embraces globalization and migration-shaped identities and narrative to challenge the film industry studies’ nation-centered preconceived notions.

Transnational Cinema has emerged as a significant field of study, questioning conventional definitions of national Cinema and illustrating the global transformations in film production, distribution, and audience reception. In addition to the integration of digital technology, the characteristics include the presence of cultural variety and the crossing of borders (Rizvi, 2006). Researchers have investigated the influence of transnational Cinema on global economies, cinematic literacy, and cultural significance (Rizvi, 2006). In general, the concept includes diasporic cinema as a subset, meaning that it places an emphasis on films that were produced by migrant communities and were meant for them (Curry, 2016).

According to 2006–2025 publications, transnational cinema is culturally varied and adaptive across borders. Diasporic stories, co-productions, and global dissemination are included. This paradigm promotes mobility, cooperation, and hybridity to improve global cultural exchanges and challenge national identities (Lim, 2019; Martin-Jones, 2019).

This review prioritizes post-2006 literature to reflect current changes, but it recognizes that older academics’ viewpoints are crucial to understanding global cinema. Dennison and Lim (2006) rebelled against national norms in European cinema. Translocalism, neolocalism, and cultural affinity—affective links between audiences and transnational literature based on common historical, linguistic, or diasporic backgrounds—influenced the debate. The emergence of transnational film in Western and non-Western nations requires these theoretical lenses (Cook, 2004; Shaw, 2017).

Discussion: synthesizing themes in transnational cinema

The fifteen articles shed light on transnational Cinema’s function as a cultural bridge. They investigate the intricacies of this role by examining four interwoven themes: Hybridity, diaspora, audience reception, and cross-border cooperation. The following is a synthesis of these topics and a study of their consequences.

Hybridity in transnational cinema

It has been demonstrated that the creative potential of hybridity may be viewed as both a strength and a possible downside. When it comes to highlighting hybrid genres in the films of Bong Joon-ho and Latin American cinema, respectively. Eason (2025) and Alalvaray (2013) emphasize hybrid genres as a method to universalize local issues while keeping cultural individuality. One point of view on hybrid genres is that the combination of many creative or cultural forms may help make local concerns more accessible to an international audience while yet maintaining the distinctive cultural character from which they come. However, Iwabuchi (2015) warned that Japanese co-productions generally water down the authenticity of the culture to appeal to Western consumers. This occurs as a result of the higher expectations of Western markets. It is clear from this that there is a tension between the creative ingenuity of artists and the commercialization of art production. In a similar vein, Smith (2024) critiques Maghrebi-French films for their inclination to romanticize the traditions of North Africa. When hybridity is mediated via colonial legacies, this reveals how power imbalances may be maintained. Hybridity is a concept that links civilizations, but it also runs the risk of flattening distinctions under the influence of globalized aesthetics. This paradox illustrates the double-edged nature of hybridity, which is that it bridges cultures. While there are scholars who are concerned about “cultural homogenization” (Tomlinson, 1999) there are also some who believe that transnational films have the potential to fight against this flattening by placing the attention on voices that are marginalized. The rise of Nollywood as a worldwide industry, for example, poses a challenge to the dominance of its Hollywood counterpart. The Nigerian film industry (Nollywood) offers narratives that are deeply rooted in Nigerian customs while yet appealing to African diasporas all over the world (Hertzke, 2016). The research conducted by Ang et al. (2015) suggests that platforms such as YouTube and TikTok provide grassroots filmmakers with the ability to sidestep conventional gatekeepers. These platforms also encourage participatory storytelling, which redefines cultural boundaries between each individual. The author analyzes hybridity in genre translation rather than focusing on international collaboration or diaspora as the primary focus of their research. The film The Good, the Bad, and the Weird is a hybrid cinematic text that reinterprets existing genre norms. It investigates how the film combines numerous Western traditions to form this hybrid text. The hybridity of transnational cinema, which integrates cultural and stylistic elements from a variety of different traditions in order to produce something uniquely original, is one of the most distinctive characteristics of this type of film. Decker (2021) presents a fresh perspective on the interaction that takes place between local and global cinematic traditions by demonstrating how transnational film may both honor and corrupt the genres from which it draws inspiration.

Diasporic identity and representation

The film of the diaspora navigates the complex relationship between belonging and displacement. Both Han (2018a) and El-Hajjami and Slaoui (2018) provide examples of how films such as Eat Drink Man Woman and Ici et là make use of food, labour, and familial ties to navigate dual identities (De Man, 2023), contributes to this conversation by putting out a theoretical shift from diasporic “victimhood” to agency, emphasizing the ability of filmmakers to recover narratives about their experiences. In contrast to the remark made by Smith (2024) that Maghrebi-French films frequently cater to European exoticism (Tsaaior, 2018), it underscores the grassroots success of Nollywood in expressing African diasporas without the intervention of Western media. The findings of this research collectively support the idea that diaspora cinema might serve as a space for resistance; nevertheless, the success of this space is contingent on equally distributed and represented works. Films such as “The Namesake” (2006) and “In This World” (2002) investigate the emotional and cultural dissonance that is experienced by communities of migrants. According to Naficy (2001), these works frequently make use of fragmentary narratives and dialogue in multiple languages to reflect the “in-betweenness” of diasporic identity. The article by Yang et al. (2020) investigates the changing landscape of transnational Cinema in South and East Asia. The authors concentrate on transnational remakes, co-productions, genre cross-contamination, diasporic and postcolonial cinemas, and documentary film festivals. This Martin Jois in line with other research, such as Han (2018b) study on diasporic identity in transnational Chinese Cinema and El-Hajjami and Slaoui (2018) study on gendered representations in Moroccan Cinema. It also investigated Hybridity and genre in transnational contexts, particularly emphasizing the interaction of gender, space, and nation in Southeast Asian Cinema.

Diasporic cinema addresses intricate matters of identity, belonging, and citizenship within both national and transnational frameworks. it examines the experiences of displaced communities, questioning conventional understandings of nationhood and cultural identity (Martin and Yaquinto, 2007). Films serve as a medium for articulating complex identities and exploring themes related to immigration internationalism, and nationalism (Dhanalakshmi and Sobana, 2024). The convergence of popular media and diasporic identities has the potential to challenge established political narratives, exemplified by Québécois cinema produced in the United States (Abramson, 2001). Diasporic film engages with historical memory, emotion, and the creation of cultural ideas, playing a significant role in the development of international groups of shared interest (Ledo-Andión and Castelló-Mayo, 2013). These films act as a platform for establishing mobile subjectivity and examining the intricacies of cultural nationality in a world that has become more globalized, where traditional boundaries between nations and cultures are becoming more fluid.

Audience reception and global distribution

Audiences have a vital role in sustaining transnational Cinema’s cultural impact. Tsaaior (2018) add that European co-productions like Border succeed by breaking national clichés, although their reach depends on festival circuits and streaming gatekeepers. This dichotomy between active involvement and corporate control underscores the necessity to democratize distribution while protecting cultural integrity (Higbee and Lim, 2010). Examines international filmmaking by charting its growing themes and issues over the past decade. It advocates for a non-Eurocentric, critical perspective that navigates the interconnections of global, national, and local cinematic settings. Case studies of diasporic, postcolonial, and East Asian films demonstrate both the liberating potential and the limitations of transnational Cinema as a theoretical framework (Berry, 2010). It is argued that transnational film emerged as a result of global economic and political developments, such as the rise of neoliberalism, free trade, and the decline of socialism, which resulted in the formation of a new cinematic order that was distinct from the conventional national cinema. Nevertheless, it also highlights the fact that transnational cinema is not merely a product of neoliberal capitalism, but also a platform where diverse ideological forces engage with one another and question the global systems that are now in place. Distribution corporations serve as cultural intermediaries, bridging national film cultures with global audiences through their acquisition criteria, curatorial approaches, and market segmentation (Ma and Wang, 2024). The mechanisms at play greatly affect how films from one country are presented, perceived, and experienced by audiences across various cultures Ma and Wang (2024) highlighting the complex dynamics of audience reception and global distribution in transnational cinema.

Cross-border collaborations

Lovatt and Trice (2021) It highlights the shift from a Western-centric approach to a more inclusive study of transnational Cinema, emphasizing the importance of South–South cooperation and the growing influence of Asian film industries like those in China and India. Similarly, Iwabuchi (2015) praises Japanese collaborations like Shoplifters for prioritizing mutual respect over marketability. Tsaaior (2018) Further contrast grassroots initiatives (e.g., Nollywood) with top-down co-productions, arguing that financial pragmatism often overshadows cultural equity. These cases underscore the importance of ethical frameworks to balance economic viability with artistic auto (Metaveevinij, 2019). The central theme of this paper is the representation of gender, city, and nation in transnational Southeast Asian Cinema, focusing on films from Thailand, Laos, Myanmar, and Cambodia. The paper explores how these films construct gendered and spatial identities, contrasting the modern, capitalist masculinity associated with Bangkok (Thailand) with the sentimental, tradition-bound femininity linked to cities like Luang Prabang (Laos), Pakse (Laos), and Mandalay (Myanmar). It argues that while these films are transnational in production, funding, and distribution, their narratives often reinforce national identities and stereotypes, maintaining a strong connection to the “national subject” despite their cross-border nature. Inter-Asian exchanges Yang et al. (2020) highlight the shift in transnational cinema studies. The concept of border landscapes is examined, focusing on how filmmakers and audiences express themes of connectivity across both rigid and flexible boundaries.

Although academic attention on transnational cinema mostly highlights co-productions and festival circuits, recent studies indicate the pivotal influence of digital and immersive technologies in redefining the transnational cinematic experience. Jurado-Martín (2020) examines how virtual, augmented, and immersive reality festivals in Latin America are transforming narrative and audience participation, providing new avenues for cross-cultural contact beyond conventional screens. These advances indicate that transnational cinema encompasses not just geopolitical cooperation but also the ways in which technology facilitates novel aesthetic, sensory, and participative experiences across boundaries. Sedeño Valdellós (2013) contend that globalization and cyberculture have transformed the discourse of film, fostering new hybrid forms and formats. Subsequent study may therefore go beyond traditional cinema texts to investigate how immersive and digital platforms are emerging as crucial venues for international interchange, narrative innovation, and cultural representation.

Conclusion

This systematic review has emphasized transnational Cinema’s transformative power as a cultural bridge, which fosters cross-cultural dialogue, challenges traditional notions of national identity, and reshapes global narratives. The study has identified key themes—Hybridity, diasporic identity, audience reception, and cross-border collaborations—that characterize the evolving discourse on transnational Cinema by synthesizing recent scholarly perspectives. The results emphasize the dual nature of transnational Cinema: it has the potential to democratize cultural exchange and amplify marginalized voices, but it also encounters challenges related to cultural commodification, power imbalances, and ethical dilemmas. Transnational Cinema continues to evolve in response to globalization and digital transformation, and it remains a critical medium for promoting cultural comprehension and connectivity in an increasingly interconnected world. Transnational cinema develops as a vibrant cultural medium, reshaping global cinematic landscapes through international collaborations, blended narratives, and the rise of diasporic identities. Filmmakers are crossing national borders to foster creative exchanges that challenge traditional narrative conventions, resulting in films that reflect a fusion of cultural influences. The integration of hybrid storylines enriches cinematic expression and captivates diverse audiences, fostering a deeper understanding of global connectivity. The reception of international films highlights the changing nature of audience engagement, as viewers increasingly embrace stories that reflect a multicultural reality. At the same time, global distribution networks and digital platforms have broadened the reach of these films, allowing them to transcend language and geographical barriers. The success of transnational cinema raises important questions about cultural authenticity, the dynamics of power in co-productions, and the balance between global appeal and local uniqueness. The development of the business will depend on the interplay of cross-cultural partnerships, hybrid identities, and audience reactions, which will be crucial in shaping the future of transnational cinema. By consistently valuing diversity while navigating the complexities of globalized filmmaking, transnational cinema can continue to serve as a powerful medium for cultural dialogue and mutual understanding in an increasingly interconnected world.

Limitations of the study

1. A select few articles, the same way that diasporic identities can be represented in varying degrees, the spectrum of transnational Cinema cannot be reflected by such a limited focus. The risk of losing an essential level of detail regarding cultural representation across genre and time is present.

2. Most transnational cinema studies have focused on representing Eastern cultures in Western films. However, very few studies engage transnational narratives in films produced in non-Western countries. This results in an incomplete understanding of the global representation of cultural Hybridity that extends beyond the confines of Western film.

3. The depiction of diasporic identity and cultural Hybridity in transnational Cinema is significantly influenced by commercialization. In many cases, filmmakers prioritize marketability over cultural elements, which may dilute cultural elements in favour of broad appeal. This balancing act can impede the ability of films to serve as authentic cultural bridges by restricting the depth and veracity of cultural representations.

4. This assessment acknowledges the importance of streaming platforms in global film but does not fully analyze them. Instead of doing platform studies, the goal was to synthesize conceptual frameworks like hybridity, diaspora, and cross-border production. The review notes that streaming is transforming global cinema and urges for empirical investigations on how digital distribution infrastructures affect transnational film texts’ development, marketing, and reception.

5. The patterns that have been identified indicate that there are new directions in the discourse surrounding transnational cinema. However, these observations should be regarded as exploratory rather than conclusive, given the limited sample size. Additional qualitative validation, such as expert interviews or focus groups, would deepen the analysis beyond bibliographic synthesis, as the topic is abundant.

Recommendations

1. One of the primary recommendations is for filmmakers and scholars to collaborate more directly with cultural specialists, anthropologists, and local historians who can contribute authenticity and substance to the representation. This could prevent the pitfalls of oversimplification and misrepresentation, resulting in more nuanced representations of cultural Hybridity and diasporic belonging.

2. Future research could concentrate on the perceptions of transnational films (prospective) by various audiences, including both Eastern and Western audiences. Understanding the reception of these films can assist us in determining the extent to which bridges between cultures were constructed or destroyed, as well as the broader implications of Hybridity and diasporic identity on a global scale.

Implications

1. Through the presentation of a wide range of narratives and points of view, transnational film creates a medium that facilitates the promotion of cross-cultural understanding. It provides viewers with knowledge of various cultural norms, histories, and societal conventions, therefore reducing preconceived notions and promoting empathy towards people all around the world (Higbee and Lim, 2010).

2. As a result of the growing interconnectedness of film businesses, there has been a progressive dismantling of the barriers that have previously existed across national cinemas. The films that were co-produced by a number of various nations bring challenges to the conventional concepts of nationhood that are prevalent in the film industry. These films have dialogue in many languages, hybrid cultural identities, and themes that will resonate with people everywhere (Naficy, 2001).

3. Transnational films have the ability to shape cultural identity by reflecting the experiences of diasporas and the interactions between different cultures. The visual representations of these descriptions allow migrants and transnational groups to visually validate their observations, so strengthening their cultural linkages and facilitating the negotiation of new identities (Ezra and Rowden, 2006a, 2006b).

4. The development of transnational cinema has led to the consolidation of film productions, the establishment of global financial frameworks, and the establishment of a variety of distribution channels. As a result of the proliferation of streaming services like Netflix and Amazon Prime, the availability of international films has increased, which has enabled these films to reach a wider audience outside of their country of origin (Cunningham and Craig, 2019).

5. The production of transnational films helps to cultivate cultural links, but at the same time, it raises concerns about cultural appropriation and distortion. The dominance of Western production companies in international cinema frequently leads to the commercialisation of non-Western stories, which can sometimes result in the perpetuation of colonial perspectives rather than authentic depictions (Shohat and Stam, 2018).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MA-M: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abramson, B. D. (2001). The specter of diaspora: transnational citizenship and international cinema. J. Commun. Inq. 25, 94–113. doi: 10.1177/0196859901025002002

Al Olaimat, F., Altawil, A., Ma’abrah, A., Al Hadeed, A., Al Hadid, A. Y. B., Tahat, Z. Y., et al. (2025). How AI is being used in universities: PR department’s perspective. Forum Ling. Stud. 7, 83–97. doi: 10.30564/fls.v7i5.8093

Alalvaray, L. (2013). Hybridity and genre in transnational latin aamerican cinemas. Transnatl. Cinemas 4, 67–87. doi: 10.1386/trac.4.1.67_1

Al-Muhaissen, B. M., Al-Hammouri, S., Rachdan, K. M., and Habes, M. (2024). How AI affects the pragmatic function in media discourse: a French press perspective. Forum Ling. Stud. 7, 369–380. doi: 10.30564/fls.v7i1.7800

Amiot-Guillouet, J., and Aguilar, A. L. (2019). Los fondos institucionales y la coproducción: una señal tangible de las relaciones Europa/América Latina y de sus evoluciones desde los años 1990. Archivos de la Filmoteca, 13–19. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2024.137676

Ang, I., Isar, Y. R., and Mar, P. (2015). Cultural diplomacy: beyond the national interest? Int. J. Cult. Policy 21, 365–381. doi: 10.1080/10286632.2015.1042474

Attar, R. W., Habes, M., Almusharraf, A., Alhazmi, A. H., and Attar, R. W. (2024). Exploring the impact of smart cities on improving the quality of life for people with disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Front. Built Environ. 10:1398425. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2024.1398425

Ben Romdhane, S., Elareshi, M., Habes, M., Alhazmi, A. H., and Attar, R. W. (2025). Connecting with the hyper (dis) connected audience: university communication attributes and student attitudes. SAGE Open 15:21582440251341056. doi: 10.1177/21582440251341058

Berry, C. (2010). What is transnational cinema? Thinking from the Chinese situation. Transnatl. Cinemas 1, 111–128. doi: 10.1386/trac.1.2.111_1

Campos, M. (2016). “Un impulso transnacional al cine latinoamericano de festivales” in Nuevas Perspectivas Sobre La Transnacionalidad Del Cine Hispánico (Leiden: BRILL), 72–81.

Chigbu, U. E., Atiku, S. O., and Du Plessis, C. C. (2023). The science of literature reviews: searching, identifying, selecting, and synthesising. Publica 11, 542–560. doi: 10.3390/publications11010002

Cho, M. (2015). Genre, Translation, and Transnational Cinema: Kim Jee-woon’s” The Good, the Bad, the Weird”. Cinema Journal, 44–68.

Cook, P. (2004). Screening the past: Memory and nostalgia in cinema -1st edition-pam (ist). Routledge. Available online at: https://www.routledge.com/Screening-the-Past-Memory-and-Nostalgia-in-Cinema/Cook/p/book/9780415183758?srsltid=AfmBOorhLSm3ikgBRWWBbXK57uigyywv9e6VlhnJAGkih3YKoghok7WN

Cunningham, S., and Craig, D. (2019). Creator governance in social media entertainment. Soc. Media Soc. 5:2056305119883428. doi: 10.1177/2056305119883428

Curry, R. (2016). “Transnational and Diasporic Cinema” in Oxford Bibliographies in Cinema and Media Studies (Oxford University Press).

De Man, A. (2023). Reframing diaspora cinema: towards a theoretical framework. Alphaville J. Film Screen Media 25, 24–39. doi: 10.33178/alpha.25.02

Decker, L. (2021). Transnationalism and genre hybridity in new British horror cinema. UK: University of Wales Press.

Dennison, S., and Lim, S. H. (2006). Remapping world cinema: Identity, culture and politics in film. Italy: Wallflower Press.

Dhanalakshmi, D., and Sobana, S. (2024). Retelling diaspora through films. Kristu Jayanti J. Human. Soc. Sci. 4, 13–19. doi: 10.59176/kjhss.v4i0.2412

Eason, E. (2025). A uniquely transnational style: bong Joon-ho’s memories of murder and the host. Youth Glob. 6, 260–275. doi: 10.1163/25895745-bja10035

El-Hajjami, M., and Slaoui, S. (2018). Diasporic and gendered identities in Moroccan transnational cinema: Mohammed Ismail’s Ici et là (here and there). Fem. Res. 2, 29–33. doi: 10.21523/gcj2.18020104

Elsaesser, T. (2015). Cine transnacional, el sistema de festivales y la transformación digital : USA.

Falicov, T. L. (2012). Programa Ibermedia: “cine transnacional iberoamericano o relaciones públicas para España”. Reflexiones 91, 299–312. doi: 10.1111/famp.12578

Geisha, W. A. (2004). Cinematic realism, reflexivity and the American ‘Madame Butterfly’ narratives. Cambridge Opera Journal 17, 59–93.

Han, Q. (2018). Negotiating identity in the diasporic space: transnational Chinese cinema and Chinese Americans. Continuum 32, 224–238. doi: 10.1080/10304312.2017.1301380

Hertzke, A. D. (2016). “The catholic church and catholicism in global politics” in Routledge handbook of religion and politics. (UK: Taylor and Francis), 36–54.

Higbee, W., and Lim, S. H. (2010). Concepts of transnational cinema: towards a critical transnationalism in film studies. Transnatl. Cinemas 1, 7–22. doi: 10.1386/trac.1.1.7/1

Higson, A. (2005). “The limiting imagination of national cinema” in Cinema and nation. France. doi: 10.1007/s10240-005-0030-5

Jones, H. D. (2024). Transnational European Cinema: Representation, Audiences, Identity. Springer Nature.

Iwabuchi, K. (2015). Pop-culture diplomacy in Japan: soft power, nation branding and the question of ‘international cultural exchange.’. Int. J. Cult. Policy 21, 419–432. doi: 10.1080/10286632.2015.1042469

Jurado-Martín, M. (2020). Aproximación a los certámenes cinematográficos de realidad virtual, aumentada e inmersiva en América Latina. Comunic. Medios 29, 134–145. doi: 10.5354/0719-1529.2020.56993

Jwaniat, M., Habes, M., Elareshi, M., and Chaudhary, S. (2025). Data journalism usages in the Middle East (Jordan): practices, policies and challenges. J. Digit. Media Policy 16, 219–236. doi: 10.1386/jdmp_00175_1

Khorana, S. (2013). Crossover cinema: a conceptual and genealogical overview. Available online at: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:55872693

Ledo-Andión, M., and Castelló-Mayo, E. (2013). Cultural diversity across the networks: the case of national cinema. Comunicar 20, 183–191. doi: 10.3916/C40-2013-03-09

Lim, S. H. (2019). Concepts of transnational cinema revisited. Transnatl. Screens 10, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/25785273.2019.1602334

Lovatt, P., and Trice, J. N. (2021). Theorizing Region: Film and Video Cultures in Southeast Asia. JCMS. Available at: https://www.filmfantourism.org/map

Ma, R., and Wang, X. (2024). Cultural representation in transnational cinema: a study of eastern cultural symbols and identity in Western films. Humanities. 3, 23–33. doi: 10.1609/icwsm.v16i1.19366

Martin, M. T., and Yaquinto, M. (2007). Framing diaspora in diasporic cinema: concepts and thematic concerns. Black Camera 22, 22–24. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27761689

Martin-Jones, D. (2019). Transnational turn or turn to world cinema? Transnatl. Screens 10, 13–22. doi: 10.1080/25785273.2019.1578527

Martin-Jones, D. (2020). Transnational turn or turn to world cinema? In Transnational Screens. UK: Routledge 19–28.

Megamerinid. (2019). An introduction to biodiversity of the Himalaya: Jammu and Kashmir state. biodiversity of the Himalaya: Jammu and Kashmir state, 3–26.

Metaveevinij, V. (2019). Negotiating representation. South East Asia Res. 27, 133–149. doi: 10.1080/0967828X.2019.1631043

Naficy, H. ed. (2001). “Situated accented cinema” in An accented cinema: exilic and diasporic filmmaking. UK.

Partida, G. D. (2019). Are we or not? Traits of Mexican identity from Roma. Journal of Latin American Communication Research 7, 79–105.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 134, 103–112. doi: 10.1016/J.JCLINEPI.2021.02.003

Rizvi, W. R. (2006). Transnational Cinema: The Film Reader, Elizabeth Ezra and Terry Rowden, Ny: Routledge, (Book Review).

Sedeño Valdellós, A. M. (2013). Globalización y transnacionalidad en el cine: coproducciones internacionales y festivales para un cine de arte global emergente. J. Commun. 6, 285–303. Available at: https://www.torrossa.com/en/resources/an/3006241

Shaw, D. (2017). Transnational cinemas: Mapping a field of study (Dennison, S. P.; Stone, Rob, Ed.). Routledge. Available online at: https://researchportal.port.ac.uk/en/publications/transnational-cinemas-mapping-a-field-of-study

Shohat, E., and Stam, R. (2018). “Stereotype, realism and the struggle over representation” in Unthinking Eurocentrism. Spain. Available at: https://repositorio.cultura.gob.cl/handle/123456789/2419

Smith, K. (2024). Questions of identity and global visibility: French funding in Latin American and Maghrebi cinema. Contemp. Fr. Civiliz. 49, 41–66. doi: 10.3828/cfc.2024.3

South Korea’s Parasite (2019). ‘Parasite’ and South Korea’s Income Gap: Call It Dirt Spoon Cinema. NA-NA: International New York Times.

Tahat, K. M., Habes, M., Tahat, D., and Alghizzawi, M., (2024). Social media use in journalism and education mediated by personal integrative needs. 2024 11th International Conference on Social Networks Analysis, Management and Security (SNAMS), 161–167.

Tahat, Z. Y., Hatamleh, I. H. M., Diab, N. M., Snoussi, T., Abduljabbar, O. J., Alrababah, O. A., et al. (2025). Faculty members’ views on digital journalism as a source of information: educational issues perspective. Forum Ling. Stud. 7:104. doi: 10.30564/fls.v7i2.8094

Tahat, K., Mansoori, A., Tahat, D., and Habes, M. (2024). Examining opinion journalism in the United Arab Emirates national press: a comparative analysis. Newsp. Res. J. 45:07395329241255159. doi: 10.1177/07395329241255159

Tsaaior, J. T. (2018). “New” nollywood video films and the post/nationality of Nigeria’s film culture. Res. Afr. Lit. 49, 145–162. doi: 10.2979/reseafrilite.49.1.09

Wang, G., and Yeh, E. Y. (2005). Globalization and hybridization in cultural products: the cases of Mulan and crouching Tiger, hidden dragon. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 8, 175–193. doi: 10.1177/1367877905052416

Keywords: globalization, transnational cinema, hybridity, urban solutions, PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis)

Citation: Al-Maliki MSS (2025) Cultural bridges in film: evolving perspectives of transnational cinema. Front. Commun. 10:1614642. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1614642

Edited by:

Lucyann Snyder Kerry, Canadian University of Dubai, United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Eka Perwitasari Fauzi, Mercu Buana University, IndonesiaMontserrat Jurado-Martín, Miguel Hernández University of Elche, Spain

Loukia Kostopoulou, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Maria C. Puche-Ruiz, Sevilla University, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Al-Maliki. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mona Shaddad Siraj Al-Maliki, bW9uYWFsbWFsaWtpNzczQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Mona Shaddad Siraj Al-Maliki

Mona Shaddad Siraj Al-Maliki