- 1Department of Communication and Community Development Sciences, Faculty of Human Ecology, IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia

- 2Department of Communication Sciences, Faculty of Communication Science, Universitas Pamulang, Banten, Indonesia

- 3Department of Communication Science, Faculty of Social and Political Science, Universitas Singaperbangsa Karawang, Karawang, Indonesia

- 4Faculty of Information and Communication Studies, University of the Philippines Open University, Los Baños, Philippines

Introduction: Digital platforms are transforming agricultural education in developing countries, yet their role in promoting sustainable farming practices remains understudied. This study investigates how YouTube facilitates knowledge transfer and behavioral change in Indonesian organic farming communities.

Methods: A mixed-methods design was employed, analyzing 1,391 viewer comments from three popular composting tutorial channels. Quantitative content analysis identified engagement patterns, while qualitative analysis explored meaning-making processes. The study also examined multimodal features of videos to understand how linguistic, visual, and audio strategies shaped pedagogical identities.

Results: Three distinct pedagogical identities were identified: the Scientific Demonstrator (technical precision with accessibility), the Faith-Based Pragmatist (religious framing with practical guidance), and the Community Motivator (collective storytelling with emotional support). Statistical analysis showed significant variations in viewer engagement (χ2 = 23.06, p < 0.001), with faith-based approaches producing the highest reports of behavioral change (26%). Qualitative analysis revealed six interconnected meaning-making processes— acceptance, transformation, restoration, appreciation, enactment, and identity reconstruction. The Indonesian concept of balas budi (reciprocal obligation) emerged as a cultural factor influencing participation.

Discussion: Findings demonstrate that effective digital agricultural education requires pedagogical plurality rather than standardization. YouTube can catalyze sustainable agricultural transitions when content aligns with local cultural values and addresses psychological barriers to adoption. This study highlights YouTube’s potential as a scalable model for digital agricultural extension services in Southeast Asia.

1 Introduction

Organic agriculture is a holistic farming approach that integrates crop rotation, green manure, compost, and biological pest management to ensure agricultural sustainability (Aleixandre et al., 2015; Paull, 2011). This method has gained recognition because of its dual contribution to environmental conservation and food security. Research has demonstrated that organic farming enhances ecosystem services, increases biodiversity, and reduces environmental pollution compared with conventional practices (Ondrasek et al., 2023; Parizad and Bera, 2021). In addition, organic produce offers superior nutritional value, positioning it as a healthier dietary choice (Popović-Djordjević et al., 2022). These attributes underscore the potential of organic farming to address global food security challenges while preserving natural resources (Badgley et al., 2007; Lombardi et al., 2021).

However, the transition to organic farming faces significant structural and technical barriers. Farmers encounter high land rents, short-term leases, and stringent food safety standards that discourage the adoption of organic methods (Carlisle et al., 2022). Technical challenges include lower initial yields, complex certification procedures, and limited access to expert guidance (Mazurek-Kusiak et al., 2021). These constraints create an urgent need for accessible and cost-effective knowledge transfer mechanisms that can supplement traditional agricultural extension services.

Digital platforms have emerged as transformative tools for agricultural education and knowledge sharing. Online communities through social media, forums, and messaging applications enable farmers to collectively exchange practical advice and solve problems (Arlena et al., 2024; Cahyani and Arisena, 2023; Ramavhale et al., 2024). These peer-to-peer interactions create translocal communities of practice that support experimentation and adaptation in organic agriculture (Sereenonchai and Arunrat, 2024). Such digital ecosystems are particularly valuable in resource-constrained settings, where formal extension services are limited.

YouTube stands out among digital platforms for its unique multimodal capabilities in agricultural education. The platform combines visual demonstrations, audio explanations, and interactive comment sections, making it particularly effective for teaching technical processes, such as organic fertilizer production and pest management (Bentley et al., 2022; Chakma et al., 2022). Unlike passive content consumption, YouTube enables active community engagement, where farmers troubleshoot problems and adapt practices to local conditions through comment-driven discussions (Yadav et al., 2024).

Despite YouTube’s widespread use in education, its application in agricultural learning remains underexplored, particularly in the Southeast Asian context. While studies have examined YouTube’s educational impact in health, language, and STEM fields (Chai et al., 2024; Li and Hikmatilla, 2025; Lijo et al., 2024), little is known about how farmers engage with agricultural tutorial content beyond viewing specifically through interactions, discussions, and collective meaning-making in comment threads (Ramavhale et al., 2024). This gap is especially pronounced in Indonesia, where organic farming expansion continues despite significant technical and institutional barriers (Sereenonchai and Arunrat, 2024).

This study presents three novel contributions to the agricultural education literature. First, it provides the first systematic analysis of YouTube-based agricultural learning communities in Indonesia, thus addressing a critical gap in digital agriculture research in Southeast Asia. Second, it introduces a four-stage meaning-making framework that extends beyond traditional learning models to include identity transformations among organic farmers. Third, it integrates cultural dimensions, particularly the Indonesian concept of “balas budi” (reciprocal exchange), into understanding digital learning effectiveness in agricultural contexts. These contributions advance the understanding of how digital platforms foster collaborative learning ecosystems for sustainable agriculture (Esteve-del-Valle and Sarchosakis, 2025).

This study examines how Indonesian farmers engage with YouTube tutorials on organic farming practices. By analyzing not only instructional content but also audience participation dynamics and peer exchange patterns, this research reveals how digital platforms transform individual learning into community-driven problem-solving processes. This approach offers practical insights into optimizing digital agricultural education in resource-constrained settings. Building on these foundations, this study addresses the following research questions:

1. What multimodal strategies do Indonesian composting educators employ on YouTube to establish distinct pedagogical identity?

2. How do viewer-comment patterns (relational, task-oriented, and effect-oriented) vary significantly across channels with different pedagogical identities?

3. To what extent do viewers’ meaning-making processes in YouTube comments indicate behavioral changes toward sustainable composting practices?

2 Methods

This study employed a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative and qualitative content analyses, to examine viewer comments on three YouTube channels featuring tutorials on organic fertilizer production. This approach enabled the identification of audience engagement patterns through quantitative analysis while also exploring the processes of meaning-making and informal learning through qualitative analysis (Lee et al., 2017; Mayring, 2000). In addition to comment analysis, the study also examined the visual elements of YouTube videos, such as the use of graphics, text overlays, and close-up shots of technical steps, to understand how multimodal features support viewers’ learning and comprehension.

2.1 Sampling

The target population of this study consisted of Indonesian YouTube viewers who engaged with educational content on organic fertilizer production. The unit of analysis was individual comments posted on the selected videos. A purposive strategy was applied to select three channels representing the diverse contexts of organic farming (urban gardening, household-based practices, and rural organic farming). The sampling frame included more than 50 Indonesian channels on organic farming, of which three channels were chosen for maximum variation.

For comment selection, 30% of comments from each video were systematically sampled, resulting in 1,391 analyzed comments (n = 1,391) out of a total of 4,639. This exceeded the minimum required sample size of 384 (for 95% confidence), ensuring the reliability of the quantitative analysis. The realized sample size consisted of 524 comments from MGB Garden, 516 from Hidup Alami ala Momi Ike, and 351 from Kebun Organik, representing a response rate of approximately 30% for the available comments. A demographic or socio-behavioral profile of respondents could not be obtained due to platform anonymity; however, thematic saturation analysis indicated the representativeness of the sampled comments. This limitation is acknowledged, since commenters represent only about 5–10% of the total viewers, meaning that the study reflects the perspectives of the most actively engaged audience segment.

2.2 Data collection

The data collection process was carried out in three systematic stages designed to ensure both representativeness and analytical depth. The process combined purposive selection of channels, strategic selection of relevant content, and systematic extraction of comments, ensuring alignment with the study objectives of analyzing multimodal communication and informal learning through YouTube.

The data collection period spanned from February to March 2025. All data were retrieved directly from YouTube using automated scripts. As the data consisted of publicly available comments, no direct incentives or recruitment procedures were applied. Instead, emphasis was placed on ensuring systematic, transparent, and replicable data retrieval.

2.2.1 Stage 1: selection of YouTube channels

Channel selection was conducted using purposive sampling based on popularity indicators, particularly the number of subscribers, total views, and volume of comments. From a catalog of more than 50 Indonesian YouTube educational channels focusing on organic farming, three channels were selected (Table 1).

2.2.2 Stage 2: content selection

Content selection focused on tutorial videos explicitly related to organic fertilizer production. The criteria included (1) practical demonstrations of fertilizer-making techniques, (2) high audience engagement (measured by views and comments), and (3) clear multimodal presentation (use of visuals, narration, and on-screen text). Three specific videos were selected.

1. “Liquid Fertilizer From Food Scrap” (MGB Garden)

2. “Buat Kompos pakai Compost Bag tanpa cacah dan EM4” (Hidup Alami ala Momi Ike)

3. “Cara Mudah Membuat Kompos Dengan Karung Menggunakan Sistem Keranjang Takakura” (Kebun Organik)

These videos were selected not only for their engagement metrics but also because they reflect diverse modalities of organic fertilizer production, making them suitable for studying both viewer learning and multimodal communication practices.

2.2.3 Stage 3: comment extraction

Data collection for viewer responses was conducted through web scraping of YouTube comments using Python and the YouTube Data API. The procedure involves several steps: installation of the Google API Python client, API authentication, construction of YouTube objects, and systematic extraction of comments (Barbos and Kaisen, 2022; Chowdhury et al., 2024). A total of 1,391 comments were sampled (30% of each video’s comments). Pilot testing demonstrated 95% thematic saturation at this threshold, exceeding the statistical requirement of 384 comments at the 95% confidence level (Riffe et al., 2019).

2.3 Data analysis

A quantitative analysis was conducted to identify patterns of viewer behavior through word and phrase frequency analysis. The main categories included appreciation, gratitude, technical questions, and prayers or good wishes. Because individual comments often contain multiple elements, the percentages could exceed 100%.

To extend beyond descriptive statistics, categorical data were processed using AI-assisted applications to perform chi-square tests. Two types of analyses were applied: (1) a chi-square test of independence to assess whether relational-oriented comments (e.g., gratitude, appreciation, prayers) were distributed differently across the three channels, and (2) chi-square goodness-of-fit tests to determine whether task-oriented and effect-oriented comments deviated significantly from expected distributions. Statistical significance was evaluated at α = 0.05, and effect sizes were reported using Cramér’s V. This procedure enabled us to assess whether specific categories of comments were disproportionately associated with particular channels.

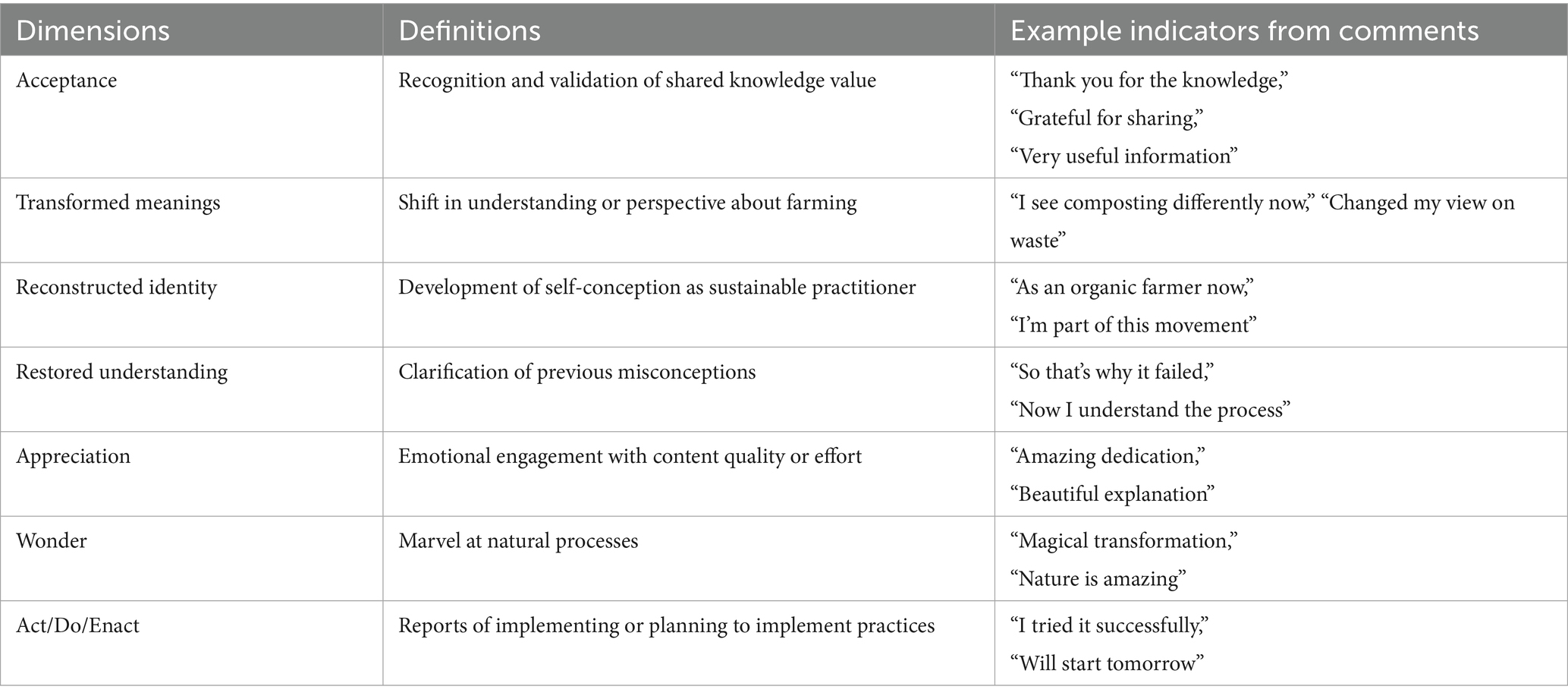

Qualitative analysis employed a directed content analysis approach. The initial coding framework was adapted from Wolsey and Lapp (2019), encompassing dimensions such as acceptance, transformed meanings, reconstructed identity, restored understanding, appreciation, wonder, and act/do/enact (Table 2). Coding was conducted iteratively, allowing for the merging, refinement, or addition of new categories. From this process, several themes emerged, including knowledge acquisition, interest in experimentation, practical application, community identity, and sharing of experiences.

Table 2. Coding framework for comment analysis (adapted from Wolsey and Lapp, 2019).

An additional analysis of visual elements, such as graphics, text overlays, and close-ups of technical steps, was conducted to explore how multimodal features supported comprehension. However, this analysis was descriptive rather than grounded in a systematic multimodal framework and is therefore acknowledged as a limitation of the study.

Taken together, the integration of quantitative and qualitative findings provides a more comprehensive picture of audience engagement. Quantitative analysis highlighted dominant categories, such as gratitude, appreciation, and technical questions, while qualitative analysis revealed deeper processes of transformed understanding, reconstructed identity, and practical enactment. These complementary insights demonstrate that surface-level engagement patterns are closely tied to deeper processes of learning and meaning-making, underscoring the value of a mixed-methods approach.

2.4 Validity and reliability

To ensure the credibility and trustworthiness of the findings, this study employed multiple triangulation strategies (Denzin and Lincoln, 2018). Data triangulation was achieved by analyzing comments across three channels representing different contexts of organic farming, thereby incorporating diverse perspectives. Methodological triangulation was implemented by combining quantitative frequency analysis with qualitative content analysis, allowing for both breadth and depth in the interpretation of audience engagement (Flick, 2018).

Reliability was strengthened through intercoder agreement procedures. Two independent coders analyzed a subset of 100 comments, and the resulting Cohen’s Kappa coefficient of 0.82 indicated substantial agreement (Landis and Koch, 1977). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, with a third researcher serving as the arbitrator. The iterative coding process employed the constant comparison method (Charmaz, 2014), ensuring analytical rigor and facilitating the refinement or emergence of new themes from the data. These strategies of triangulation, intercoder reliability testing, and iterative coding collectively ensured the robustness, credibility, and trustworthiness of both quantitative and qualitative findings.

2.5 Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Ethics Committee of BRIN (Ethics Clearance No. 383/KE.01/SK/04/2025). Written consent was obtained from the channel creators. Although the comments were public, the usernames were anonymized to protect privacy. The complete dataset will be made available in an open repository following publication to ensure transparency.

3 Result

3.1 Multimodal communication in composting tutorials

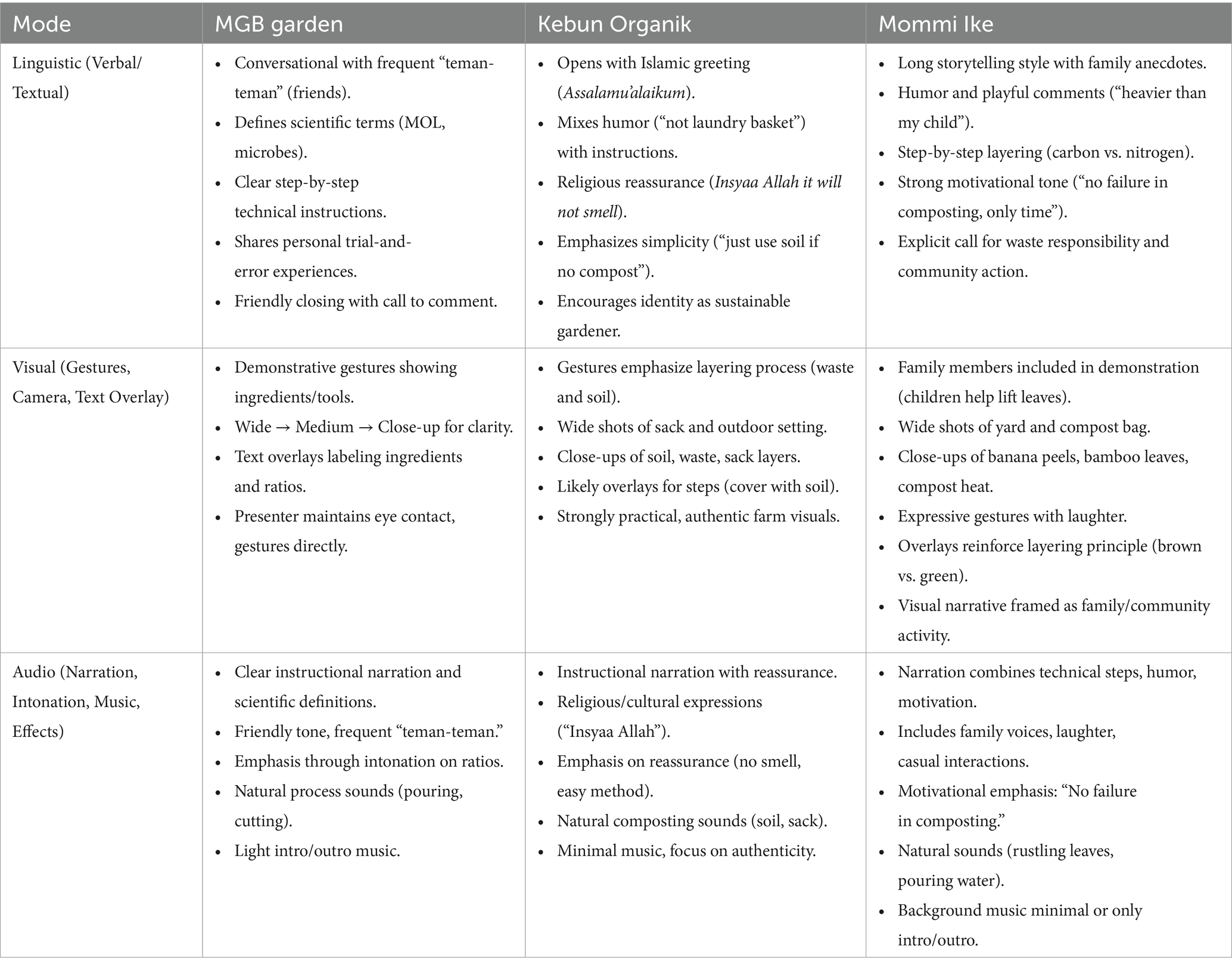

The analysis of three Indonesian YouTube channels, MGB Garden, Kebun Organik, and Hidup Alami ala Momi Ike, shows that although all focus on composting education, each employs distinctive multimodal strategies that shape pedagogical identity and audience engagement (Table 2). Differences emerged across the linguistic, visual, and audio dimensions.

In the linguistic dimension, the MGB Garden combines technical instruction with conversational tone using scientific terminology alongside friendly address (“teman-teman”) and personal experiences. Kebun Organik integrates religious reassurance and humor, beginning with Islamic greetings and emphasizing simplicity with phrases like “InsyaaAllah it will not smell.” In contrast, Hidup Alami ala Momi Ike employs motivational storytelling, using family anecdotes and humor while framing composting as a shared moral responsibility.

Visual strategies further differentiate channels. MGB Garden emphasizes procedural clarity, with demonstrative gestures, structured camera movements, and text overlays. Kebun Organik highlights agrarian authenticity, showing rural settings and practical layering of soil and waste. Hidup Alami ala Momi Ike incorporates family participation, presenting composting as an intergenerational and communal activity, supported by expressive gestures and visual reinforcement of layering principles.

In the audio dimension, MGB Garden delivers a clear instructional narration with an emphasis on ratios, supported by natural process sounds. Kebun Organik focuses on reassurance, using religious expressions and minimal background music to enhance authenticity. Mommi Ike creates a collective atmosphere, mixing technical narration with laughter, casual interaction, and motivational repetition such as “no failure in composting.”

3.2 Relational dimensions of learning: how viewers build social and emotional connections through comments

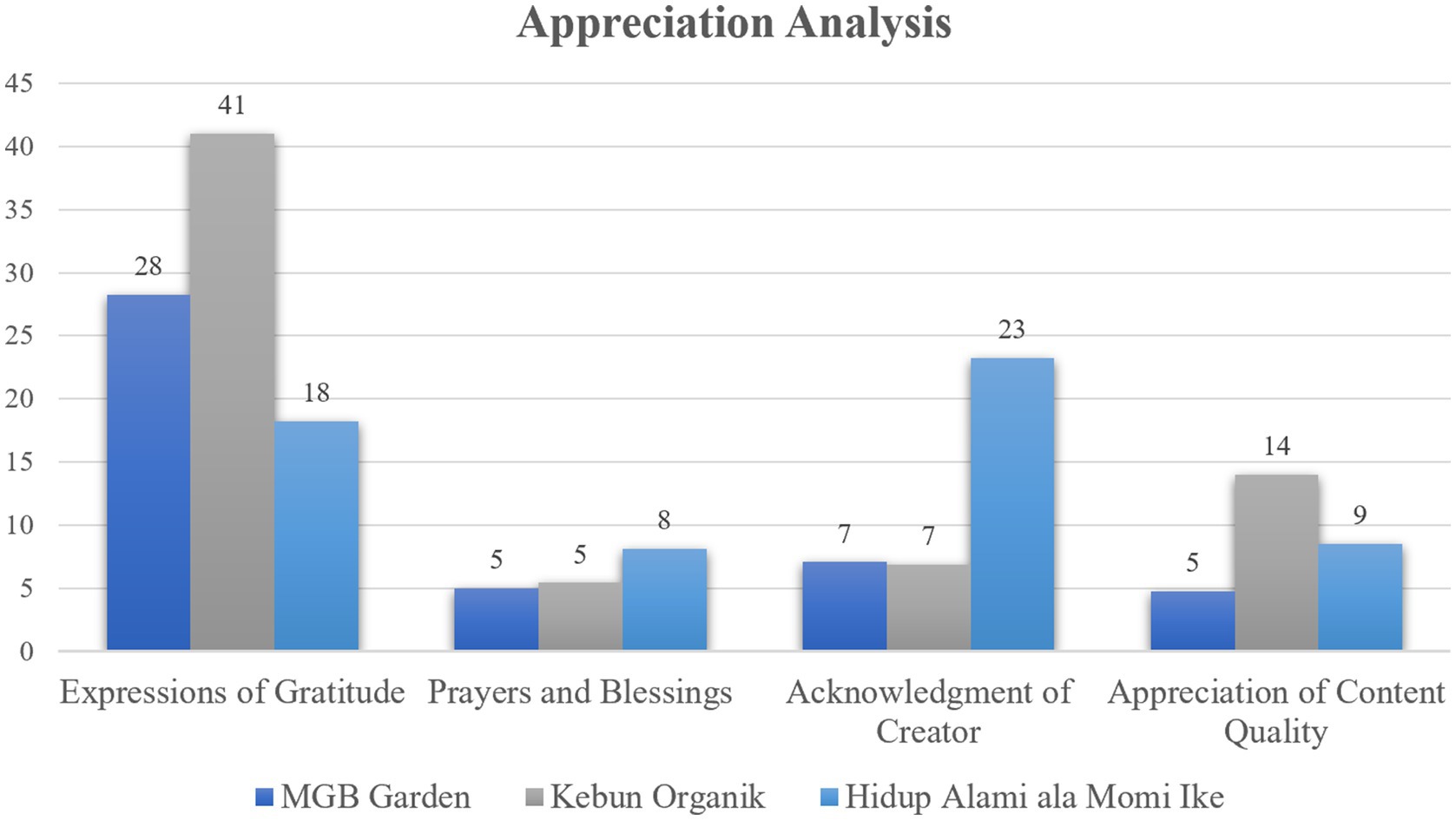

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of relational comments, categorized into four themes: expressions of gratitude were the most frequently expressed sentiment (41%), followed by acknowledgement of the creator (23%), appreciation of content quality (14%), and prayers and blessings (8%).

A chi-square test of independence confirmed statistically significant differences in the distribution of relational comments across the three channels (χ2 = 23.06, df = 6, p < 0.001, n = 1,391), with a moderate effect size (Cramér’s V = 0.287). Post-hoc standardized residual analysis showed that Hidup Alami ala Mommy Ike received significantly more “Acknowledgment of Creator” responses than expected (z = +2.92, p < 0.01) and significantly fewer “Expressions of Gratitude” responses (z = −2.14, p < 0.05). In contrast, Kebun Organik and MGB Garden displayed a higher proportion of gratitude comments, although these differences were not statistically significant at the individual cell level.

Typical expressions included simple acknowledgements such as “Terima kasih banyak ilmunya, sangat bermanfaat” (Thank you very much for the knowledge, it is very useful), and personalized appreciation like “Ibu Ike luar biasa, semoga sehat selalu” (Madam Ike, you are amazing, may you always be healthy).

3.3 Task-oriented comments on YouTube tutorial videos

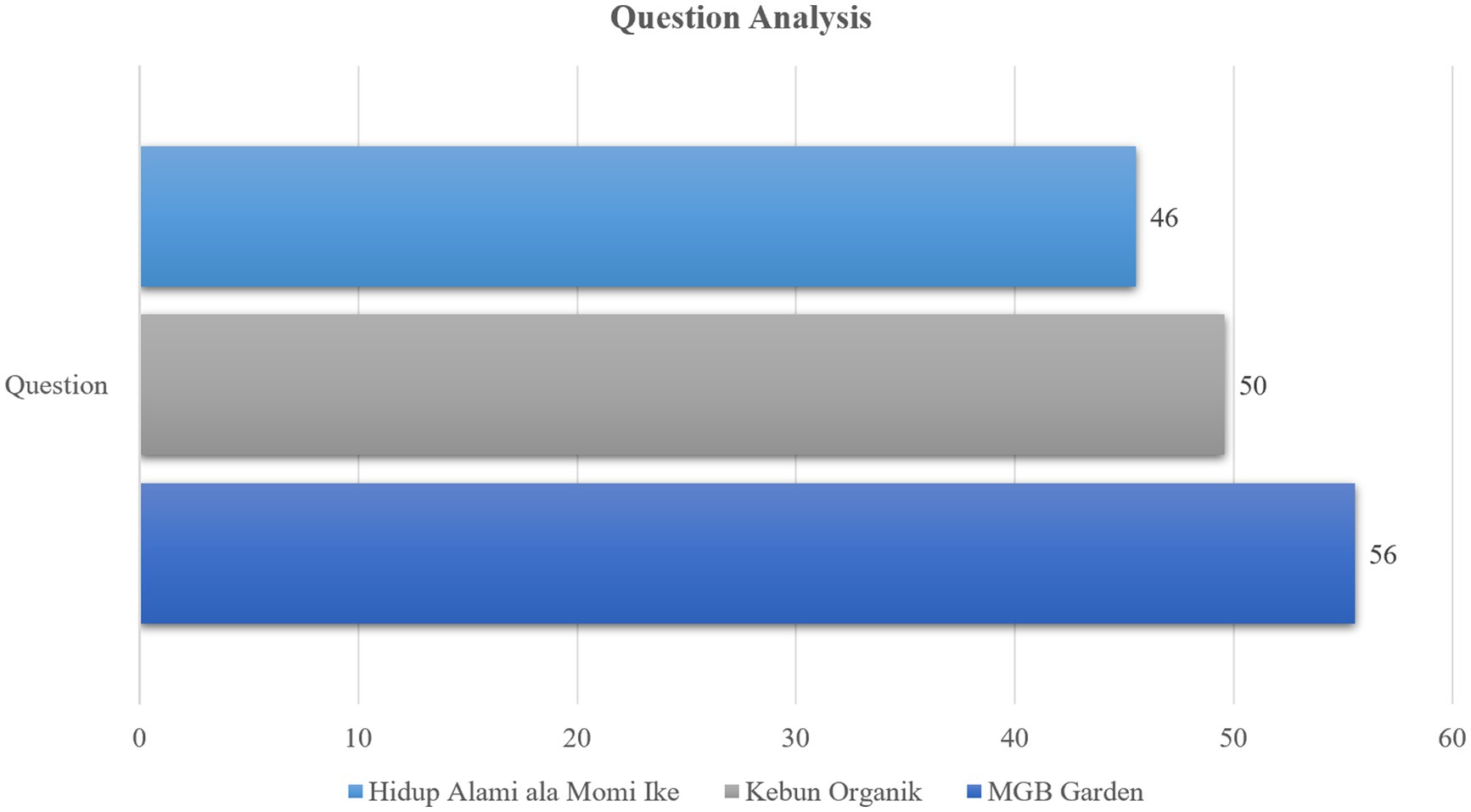

Figure 2 presents the distribution of task-oriented comments, specifically questions raised by viewers. MGB Garden recorded the highest number of questions (n = 56), followed by Kebun Organik (n = 50) and Hidup Alami ala Mommy Ike (n = 46).

A chi-square goodness-of-fit test revealed no significant differences in the distribution of questions across the three channels (χ2 = 1.00, df = 2, p = 0.61). This result indicates that the propensity to ask questions was relatively consistent among viewers across all three channels.

Illustrative examples of task-oriented questions include: “Apakah bisa pakai kulit pisang kalau tidak ada molase?” (Can banana peels be used if molasses is unavailable?) and “Berapa lama proses fermentasi sampai pupuk cair siap dipakai?” (How long does the fermentation process take before the liquid fertilizer can be used?).

3.4 Effect-oriented comments on YouTube tutorial videos

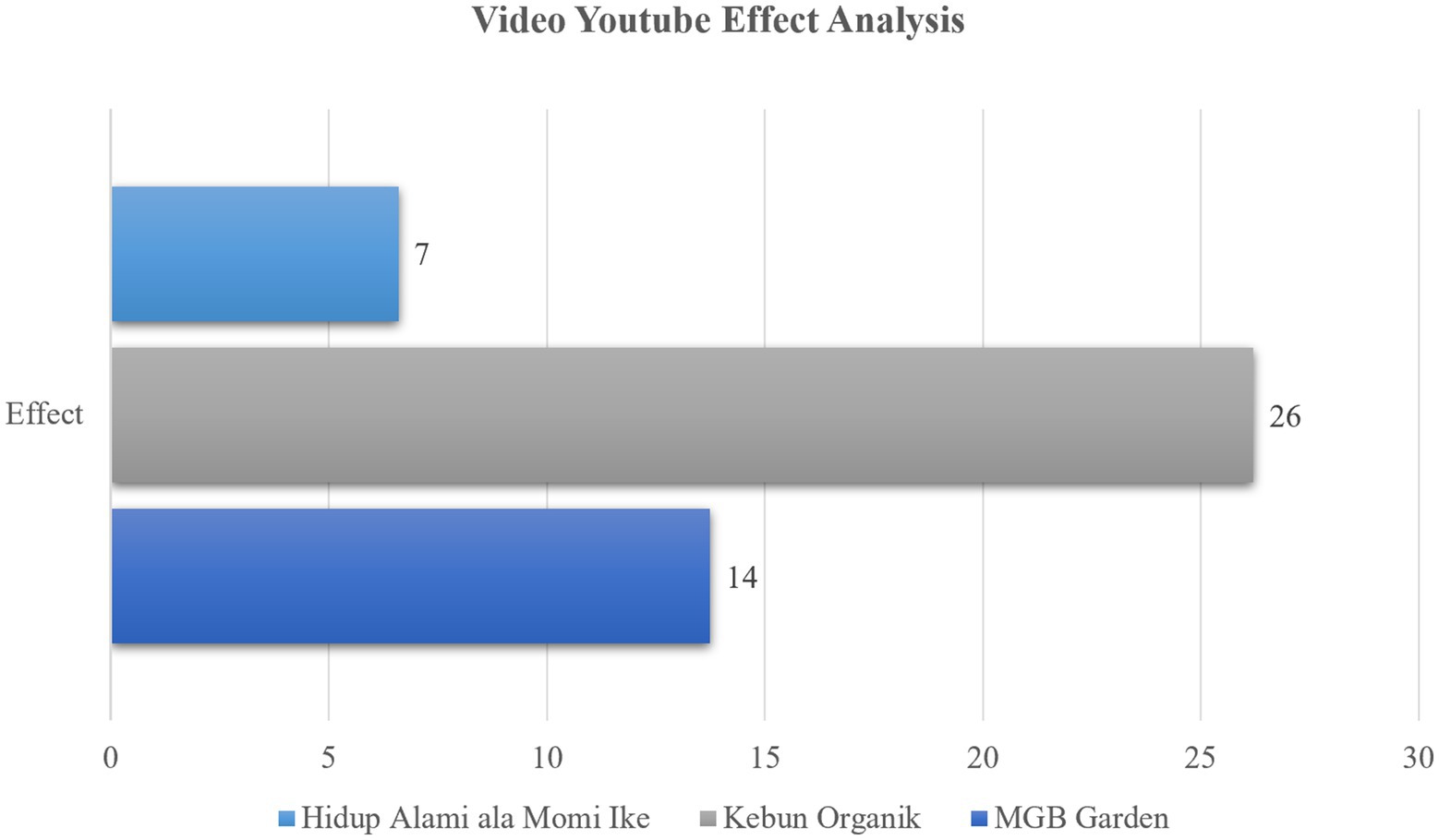

Figure 3 shows the distribution of effect-oriented comments, which reflected viewers’ perceived outcomes after engaging with tutorials. Kebun Organik generated the highest proportion of effect-oriented comments (26%), followed by MGB Garden (14%) and Hidup Alami ala Mommy Ike (7%).

A chi-square goodness-of-fit test confirmed that these differences were statistically significant (χ2 = 11.79, df = 2, p = 0.0028). Follow-up analysis indicated that Kebun Organik received significantly more effect-oriented responses than expected, while Mommy Ike received significantly fewer responses. The distribution for the MGB Garden was consistent with the expected frequencies.

Viewers often described practical applications, such as “Saya sudah coba cara ini dan hasil komposnya bagus sekali” (I tried this method and the compost turned out very well), or noted improvements in farming practice, e.g., “Tanaman saya lebih subur setelah pakai pupuk cair ini” (My plants grew better after using this liquid fertilizer).

3.5 Aspects of meaning-making in YouTube viewer comments

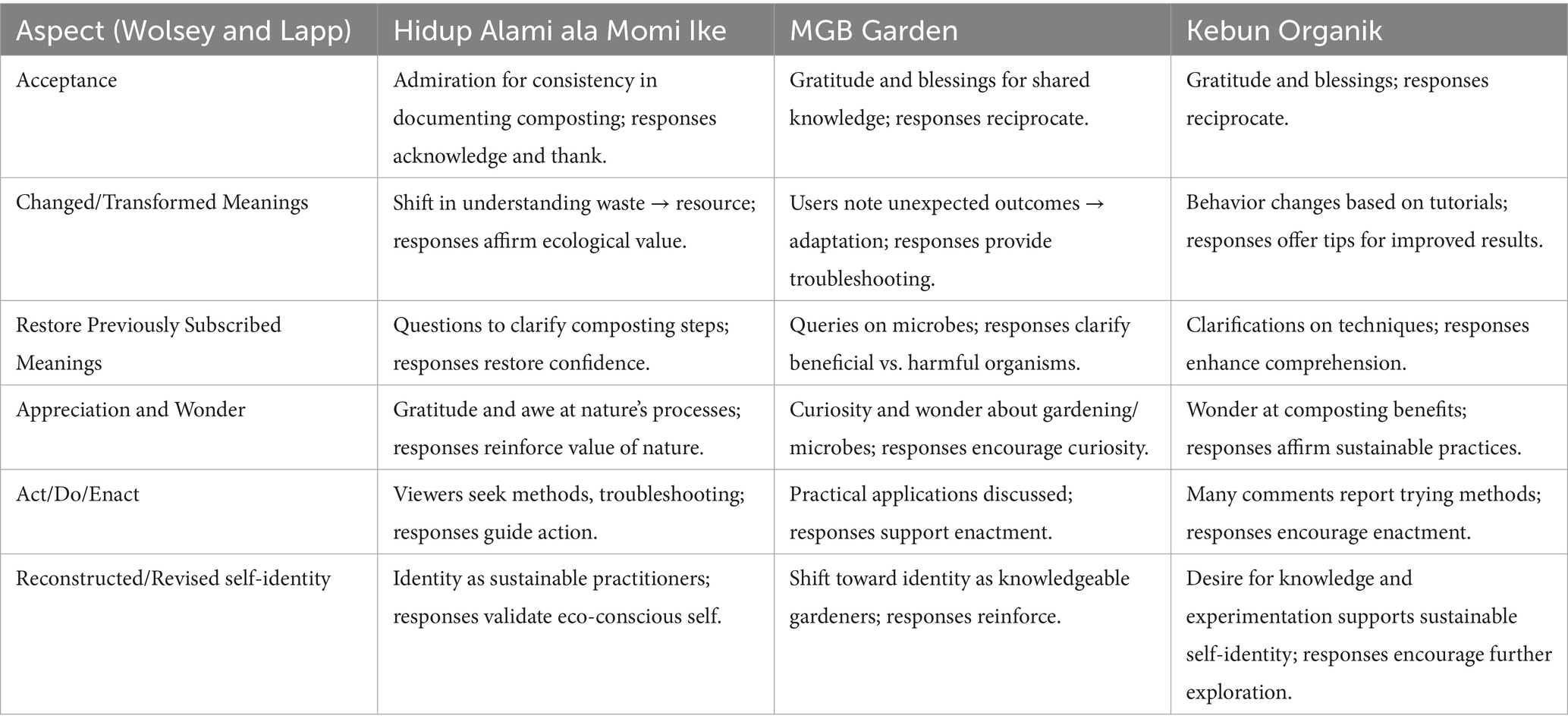

Following the presentation of the quantitative distribution of relational, task-oriented, and effect-oriented comments, a qualitative analysis was conducted to examine the ways in which viewers engaged with the content. This step identified not only the frequency of responses but also the types of meaning-making processes evident in the comments. Using Wolsey and Lapp’s (2019) framework, the coding categorized instances in which viewers expressed acceptance, revised understanding, enacted practices, or referred to aspects of self-identity in relation to tutorials.

The results of this qualitative coding are presented in Table 3: Concise Matrix of Meaning-Making Aspects Across Channels. The table summarizes the recurring aspects across the three channels Hidup Alami ala Momi Ike, MGB Garden, and Kebun Organik and provides representative examples of comments and responses. These findings extend the quantitative results by showing the range of ways in which viewers engage with tutorial content (Table 4).

Table 3. Comparative analysis of linguistic, visual, and audio strategies across three YouTube channels.

Across the three channels, expressions of acceptance were observed in the form of admiration, gratitude, and blessings, with responses typically acknowledging or reciprocating these remarks. Comments reflecting changed or transformed meanings included shifts in viewing waste as a resource, references to unexpected outcomes, and reports of behavioral change. The responses in these cases affirmed or offered practical guidance.

Instances of restoring previously subscribed meanings appeared in questions seeking clarification of composting steps or microbial functions, with responses providing explanations. Expressions of appreciation and wonder were also recorded, such as remarks of gratitude or curiosity about natural processes for which responses frequently provided reinforcement or encouragement. Enactment was evident when viewers asked for methods, shared applications, or reported trying practices, with responses supplying support or guidance. Finally, some comments referred to self-identity, where viewers described themselves as practitioners or learners of sustainable gardening and responses acknowledged or encouraged these statements.

Other aspects included the restoration of previously subscribed meanings, where viewers sought clarification on composting techniques or microbial agents, and responses supplied corrective explanations. Expressions of appreciation and wonder were common across all three channels, highlighting gratitude and curiosity toward natural processes, while responses reinforced these attitudes. Finally, enactment was evident as viewers actively sought guidance for practice, discussed applications, or reported trying methods themselves, and responses supported these actions. In several cases, commenters articulated a reconstructed self-identity, positioning themselves as sustainable practitioners or knowledgeable gardeners, with responses validating and encouraging this emerging identity.

4 Discussion

4.1 Multimodal strategies and pedagogical identity construction

The emergence of distinctive pedagogical identities among Indonesian YouTube composting educators reveals how digital content creators strategically orchestrate multiple semiotic modes to establish educational authority and connect with diverse audiences. This study identifies three distinct pedagogical identities, the Scientific Demonstrator, the Faith-Based Pragmatist, and the Community Motivator, each emerging through specific configurations of linguistic, visual, and audio strategies that reflect fundamentally different epistemological approaches to environmental knowledge transmission.

The Scientific Demonstrator identity, exemplified by MGB Garden, manifests through what Kress and Van Leeuwen, 2001 term “modulated formality,” employing dual-register linguistic strategies that combine scientific terminology with conversational markers. This code-switching between technical precision and accessibility creates a unique pedagogical space in which scientific authority coexists with democratic knowledge sharing. Visually, this identity employs systematic cinematographic progressions from wide to close-up shots, mirroring the cognitive zoom of scientific observation, while text overlays provide cognitive anchoring that reduces the processing load. The acoustic dimension completes this identity through clear enunciation with strategic pauses at measurement points, creating what O’Halloran et al. (2018) describe as ‘intersemiotic complementarity’, where each mode reinforces the others in constructing scientific credibility.

In contrast, the faith based pragmatist identity adopted by Kebun Organik integrates religious discourse with agricultural instruction, consistently opening Islamic greetings and embedding technical content within spiritual frameworks. This religious indexing serves multiple functions beyond mere cultural acknowledgement; it establishes shared identity, reduces uncertainty through divine attribution, and frames composting as a simultaneously practical and spiritual practice. The visual strategy of agrarian authenticity, featuring unadorned demonstrations with soil-covered hands in rural settings, constructs legitimacy through embodied experience rather than theoretical knowledge. The minimalist soundscape prioritizing natural composting sounds with steady, reassuring tones during religious invocations creates sonic markers of trustworthiness that complement visual rusticity.

The Community Motivator identity, embodied by Hidup Alami ala Momi Ike, transforms individual instruction into a collective journey through narrative-motivational linguistic registers featuring extended storytelling and affirmational mantras. This approach aligns with Indonesia’s oral tradition, where knowledge is embedded within stories carrying both practical and moral dimensions. Visually, the consistent inclusion of family members transforms composting from technical practice to family ritual, constructing what Celidwen and Keltner (2023) term “ecological belongin.” The polyvocal soundscape of mixing technical narration with children’s laughter disrupts traditional pedagogical authority, employing affective scaffolding, where emotional support becomes integral to knowledge acquisition.

4.2 Differential viewer engagement patterns

The analysis of viewer comment patterns revealed that pedagogical identity profoundly shapes audience engagement, with statistically significant variations emerging across relational, task-, and effect-oriented responses. These differential patterns demonstrate that pedagogical identity influences not merely knowledge presentation but fundamentally alters how audiences interpret their relationship with content and creators.

The distribution of relational comments reveals a counterintuitive pattern that illuminates the complex relationship between the pedagogical approach and viewer reciprocation. The Community Motivator paradoxically received significantly more personal acknowledgements while receiving fewer expressions of gratitude, suggesting that communal storytelling triggers different relational scripts than traditional pedagogical formats. Comments acknowledging personal qualities rather than expressing thanks indicate parasocial bonding, where viewers relate to the creator as a community member rather than a distant instructor. Conversely, both the Scientific Demonstrator and Faith-Based Pragmatist approaches generated higher proportions of gratitude expressions, suggesting that their more formal pedagogical stances activate traditional teacher-student dynamics where knowledge becomes a valuable gift requiring reciprocation through thanks (Allen et al., 2024).

This differential pattern reflects the Indonesian concept of balas budi, a moral obligation of reciprocal exchange that mediates digital engagement in culturally specific ways. While creators who assert technical precision or spiritual authority elicit reciprocal appreciation from viewers (Sudibyo, 2018), communal approaches transform these obligations into recognition and solidarity (Novianti et al., 2025), fostering peer-to-peer support (Soriano and Cabalquinto, 2024) through YouTube’s interactive features and reflecting evolving cultural norms (Khasanah et al., 2023) and participatory practices in Indonesia (Winarnita et al., 2022).

While all channels received statistically similar numbers of task-oriented questions, qualitative analysis revealed functional diversity beneath surface uniformity. Questions directed at the Scientific Demonstrator predominantly seek procedural precision and exact parameters, treating composting as a technical practice requiring specific conditions. The Faith-Based Pragmatist generates queries about material substitution and local adaptation, with viewers attempting to reconcile idealized practices with material constraints while maintaining promised spiritual efficacy (Prasad, 2021). The Community Motivator receives questions addressing social navigation and communal concerns, reflecting Indonesia’s collectivist orientation, where individual practice must integrate within community contexts.

The most striking differential appears in effect-oriented comments, where the Faith-Based Pragmatist’s 26% significantly exceeds both other channels. This dominance in generating behavioral reports can be explained through “efficacy insurance” religious framing reduces psychological barriers to action by attributing potential failure to divine will rather than personal incompetence (Rosmarin et al., 2023). This cultural adaptation of Bandura’s self-efficacy theory facilitates behavioral activation by reducing outcome anxiety through spiritual scaffolding (Farley, 2020). Conversely, scientific precision may inadvertently create implementation barriers by emphasizing exact specifications that intimidate viewers lacking confidence in replicating laboratory-like conditions, whereas communal framing may build collective identity without necessarily triggering individual action.

4.3 Meaning-making processes and behavioral transformation

The trajectory from digital engagement to behavioral transformation reveals complex meaning-making processes that serve as critical mediators between knowledge exposure and sustainable practice adoption. The analysis identified interconnected dimensions of meaning-making that collectively indicate varying degrees of behavioral change, with each pedagogical approach facilitating different transformation pathways.

The foundational process begins with acceptance, where viewers validate the presented knowledge through expressions of gratitude and blessings. However, acceptance patterns vary significantly by pedagogical approach, revealing different pathways to knowledge internalization. Technical acceptance of scientific accuracy provides insufficient motivation for practice adoption, as evidenced by moderate behavioral activation rates. When acceptance incorporates spiritual dimensions, transforming cognitive acknowledgement into moral-spiritual commitment, it catalyzes action more effectively (Mrazek et al., 2024). Emotional acceptance through parasocial bonds, while building strong connections, may prove insufficient for behavioral change without accompanying technical confidence (Tarsha and Narvaez, 2023).

The most significant indicator of impending behavioral change appears in transformed meanings, particularly the conceptual shift from viewing waste as a disposal problem to recognizing it as a valuable resource. This cognitive restructuring represents transformative learning fundamental shifts in meaning perspectives, enabling new forms of action. These transformations occur through different mechanisms: scientific reframing through understanding decomposition processes; spiritual reframing, where waste becomes divine trust requiring stewardship; and social reframing, where waste management becomes family responsibility (Anokye and Mohammed, 2024). The presence of transformed meanings strongly correlates with subsequent behavioral reports, suggesting that meaning transformation serves as a cognitive bridge between knowledge and action.

Direct evidence of behavioral change appears in enactment comments reporting actual implementation, revealing the progression from initial experimentation through sustained practice to practice expansion. This progression suggests that YouTube-mediated learning catalyzes not only individual behavioral change, but also community-level transformation. The deepest level of change manifests in identity reconstruction, where viewers articulate transformed self-concepts as environmental stewards (Risien and Goldstein, 2021). This identity transformation follows different trajectories: professional identity as knowledgeable gardeners, moral identity where earth care becomes worship, and collective identity emphasizing family commitment. Identity reconstruction represents the most persistent form of behavioral change, indicating a shift from external motivation to internalized values.

The affective dimension of appreciation and wonder toward natural processes creates emotional rewards that reinforce continued practice, while the availability of responsive support through comment interactions provides a safety net that prevents behavioral discontinuation. This interactive dimension suggests that digital platforms offer unique advantages in sustaining behavioral change through continuous community support and troubleshooting assistance.

These findings demonstrate that effective sustainability education through digital platforms requires careful consideration of how pedagogical identity shapes knowledge transmission, audience engagement, and behavioral transformation. The success of different approaches depends not on universal best practices but on the alignment between pedagogical identity, audience expectations, and cultural contexts. Understanding these complex relationships is essential for designing digital environmental education that moves beyond information dissemination to catalyze genuine behavioral change toward sustainable practices.

4.4 Implications

The emergence of distinct pedagogical identities through multimodal orchestration reveals that effective digital education transcends mere information transmission, functioning instead as culturally embedded identity performance. The three identified patterns, Scientific Demonstrator, Faith-Based Pragmatist, and Community Motivator, represent fundamentally different epistemological stances that extend beyond Mayer’s (2024) Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning. While Western models prioritize efficiency and clarity through cognitive load management, Indonesian educators demonstrate that effective agricultural education requires sophisticated integration of technical knowledge with religious frameworks, communal values, and affective support. This finding suggests that multimodal communication in educational contexts serves as identity performance where creators strategically deploy available semiotic resources to construct culturally resonant pedagogical personas, extending Goffman’s dramaturgical approach to digital pedagogical contexts.

The strategic deployment of these multimodal resources indicates that successful digital agricultural education in Southeast Asian contexts requires the recognition of pedagogical plurality rather than standardization. Each identity serves distinct learning needs: technical precision satisfies knowledge seekers, spiritual framing reduces uncertainty for risk-averse practitioners, and communal engagement mobilizes collective action. This pedagogical diversity reflects the heterogeneous nature of Indonesia’s agricultural communities and their varied pathways toward sustainable practice adoption, suggesting that one-size-fits-all approaches to digital education may fail to effectively engage diverse audience segments.

These findings reveal that pedagogical identity functions as an “engagement architecture” that fundamentally structures audience participation patterns in the learning process. The Scientific Demonstrator builds trust through precision but may inadvertently create implementation barriers through complexity, generating high gratitude but moderate behavioral activation. The faith based pragmatist achieves an optimal balance between appreciation and action by reducing anxiety through spiritual scaffolding while maintaining practical focus. The Community Motivator builds strong parasocial bonds and collective identity but may diffuse individual responsibility for action. These differential patterns extend engagement theory by demonstrating that viewer responses represent culturally mediated performances shaped by pedagogical positioning rather than mere reactions to content quality.

This analysis challenges Western models of online engagement that emphasize individual learning and cognitive outcomes, thereby revealing the crucial dimensions of knowledge circulation in collectivist societies. The prominence of relational comments, cultural specificity of reciprocal patterns, and the role of religious framing in behavioral activation point toward the necessity of culturally-situated theories of digital pedagogical engagement that account for concepts like “balas budi” and collective identity formation.

The evidence that YouTube comments indicate genuine behavioral change suggests that strategic investment in digital agricultural education could accelerate sustainability transitions in developing contexts where traditional extension services face resource limitations. However, behavioral change requires integrated support for meaning-making processes that bridge knowledge and actions. Effective digital interventions should facilitate meaning transformation by explicitly connecting technical practices to values and identity, provide scaffolding for identity reconstruction through narrative and community building, maintain responsive support systems addressing implementation challenges, integrate cultural-religious frameworks to reduce psychological barriers, and balance individual and collective frameworks to optimize both personal and community change. The progression from acceptance through transformation to identity reconstruction demonstrates that digital platforms can support deep behavioral change when designed to facilitate comprehensive meaning-making processes, positioning YouTube as a powerful tool for sustainability education in the Global South context.

4.5 Policy directions

The emergence of three distinct pedagogical identities—Scientific Demonstrator, Faith-based Pragmatist, and Community Motivator—presents unprecedented opportunities for transforming agricultural education in Indonesia through strategic multisector collaboration. These findings reveal that effective digital agricultural education requires coordinated efforts across the government, civil society, and technology sectors.

At the governmental level, Indonesia’s Ministry of Agriculture can leverage these pedagogical insights to revolutionize its extension services. The Faith-Based Pragmatist approach’s remarkable 26% behavioral change rate demonstrates the power of culturally aligned communication in rural communities. By developing a tiered digital strategy that matches pedagogical approaches to specific farmer segments—scientific precision for commercial farmers, faith-based pragmatism for risk-averse smallholders, and community motivation for collective initiatives—the Ministry could exponentially expand its reach beyond the current 15% coverage of Indonesia’s 33 million farmers. This expansion requires recognizing YouTube creators as informal extension agents, providing them with technical validation and research updates while preserving their authentic pedagogical identities.

Building on these governmental initiatives, NGOs can amplify the impact by employing the identified meaning-making processes in their program design. The transformation from viewing waste as a disposal problem to a valuable resource represents a cognitive shift that NGOs can facilitate through culturally resonant narratives. By developing peer-learning networks based on “balas budi” principles and recruiting successful local content creators, NGOs can transform individual learning into community-level change while maintaining the trusted voices that are essential for sustained behavioral transformation.

Finally, digital platforms must evolve from passive content hosts to active agricultural knowledge infrastructure. YouTube and similar platforms should develop features specifically designed for farming communities, from algorithmic recommendations based on pedagogical alignment to agricultural learning pathways that mirror natural meaning-making progressions. These technological adaptations, combined with governmental support and NGO expertise, could create an integrated ecosystem for digital agricultural education that could serve as a model for sustainable development across Southeast Asia.

4.6 Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, it examined only three YouTube channels, which, while representing distinct pedagogical approaches, may not capture the full diversity of Indonesian agricultural educational content online. The selection criteria focused on channels with substantial following and consistent composting content, potentially excluding emerging creators or alternative pedagogical styles that could offer additional insights into multimodal communication strategies.

Second, reliance on publicly visible YouTube comments introduces selection bias, as these represent only viewers who actively choose to engage publicly. Silent viewers, who may constitute the majority of the audience, remain unexamined. Additionally, comments provided self-reported behavioral claims rather than verified practice implementation. The reported 26% maximum rate of effect-oriented comments may overestimate actual behavioral change, as social desirability bias could motivate exaggerated claims of practice adoption.

Third, the cross-sectional nature of data collection prevents the longitudinal assessment of behavioral persistence. While comments indicate initial implementation attempts and identity reconstruction, this study cannot determine whether these changes translate into sustained practice over time. The absence of follow-up data limits the understanding of factors that support or hinder the long-term adoption of sustainable composting practices.

Fourth, the analysis focused exclusively on Indonesian content and audiences, limiting its generalizability to other cultural contexts. The prominent role of religious framing and concepts such as “balas budi” may be specific to Indonesian or Southeast Asian contexts, requiring careful consideration before applying findings to other regions or cultural settings.

Finally, the study did not examine the actual environmental impact of the reported behavioral changes. While increased composting adoption suggests positive environmental outcomes, research cannot quantify waste reduction, soil improvement, or carbon sequestration benefits. Future research should incorporate mixed-methods approaches, including ethnographic observation, longitudinal tracking, and environmental impact assessment, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how digital agricultural education translates into measurable sustainability outcomes.

5 Conclusion

This study examined how multimodal communication strategies on YouTube facilitate meaning-making and behavioral changes in Indonesian organic farming education. Through an analysis of three composting education channels and 1,543 viewer comments, this research reveals the complex interplay between pedagogical identity, viewer engagement patterns, and sustainable practice adoption.

These findings demonstrate that content creators strategically orchestrate linguistic, visual, and audio modes in order to construct three distinct pedagogical identities. MGB Garden establishes itself as a Scientific Demonstrator through technical terminology, systematic visual progression, and precise audio delivery. Kebun Organik emerges as a Faith-Based Pragmatist by integrating Islamic discourse with practical demonstration and agrarian authenticity. Mommi Ike functions as a Community Motivator through family-centered narratives, collective visual participation, and affective engagement. These identities represent different epistemological approaches to agricultural knowledge, scientific empiricism, spiritual pragmatism, and communal constructivism, each resonating with specific audience segments.

Viewer engagement patterns vary significantly across pedagogical identities. Statistical analysis reveals that Mommi Ike receives more personal acknowledgement but less transactional gratitude, suggesting that her communal approach triggers parasocial bonding rather than hierarchical teacher-student dynamics. Kebun Organik generates the highest rate of effect-oriented comments, indicating that religious framing effectively reduces psychological barriers to practice adoption. While all channels receive similar numbers of questions, their functional purposes differ technical clarification for MGB Garden, material adaptation for Kebun Organik, and social navigation for Mommi Ike.

The meaning-making analysis revealed six interconnected processes through which viewers translated digital content into sustainable practices: acceptance, transformation, restoration, appreciation, enactment, and identity reconstruction. The conceptual shift from viewing waste as a disposal problem to recognizing it as a valuable resource marks critical cognitive restructuring that enables behavioral change. Identity reconstruction where viewers describe themselves as organic farmers or zero-waste families represents the deepest level of transformation, suggesting that YouTube facilitates not just skill acquisition but also fundamental shifts in environmental consciousness.

These findings contribute to multimodal communication theory by demonstrating how cultural factors mediate digital learning. The Indonesian concept of “balas budi” (reciprocal obligation) shapes engagement patterns, while religious framing provides “efficacy insurance” that facilitates behavioral activation. This challenges Western-centric online education models by highlighting the importance of cultural-spiritual dimensions in knowledge transfer and application.

This study suggests that effective digital agricultural education requires recognizing pedagogical plurality rather than seeking standardization. Each identity serves different functions: scientific precision builds technical confidence, religious integration reduces implementation anxiety, and communal storytelling constructs a collective identity. This portfolio approach to digital pedagogy could accelerate the development goals by addressing diverse learning needs and cultural contexts in agricultural communities.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article will be made available on request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to c2Fyd2l0aXRpQGFwcHMuaXBiLmFjLmlk.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The National Research and Innovation Agency. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Formal analysis, Validation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TS: Investigation, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AF: Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. DL: Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. IM: Investigation, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to IPB University, Universitas Pamulang, Universitas Singaperbangsa, and the University of the Philippines Open University for their support and collaboration in this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aleixandre, J. L., Aleixandre-Tudó, J. L., Bolaños-Pizarro, M., and Aleixandre-Benavent, R. (2015). Mapping the scientific research in organic farming: a bibliometric review. Scientometrics 105, 295–309. doi: 10.1007/s11192-015-1677-4

Allen, K.-A., Grove, C., May, F. S., Gamble, N., Lai, R., and Saunders, J. M. (2024). Expressions of gratitude in education: an analysis of the #ThankYourTeacher campaign. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 20:13. doi: 10.1007/s40979-024-00159-2

Anokye, K., and Mohammed, A. S. (2024). Indigenous traditional knowledge for cleaner waste systems and sustainable waste management system in Ghana. Cleaner Waste Systems 9:100165. doi: 10.1016/j.clwas.2024.100165

Arlena, W. M., Muljono, P., Sarwoprasodjo, S., and Herawati, T. (2024). Literature review: a study of YouTube utilization for livestock and agricultural businesses. Stud. Media Commun. 13:231. doi: 10.11114/smc.v13i1.7324

Badgley, C., Moghtader, J., Quintero, E., Zakem, E., Chappell, M. J., Avilés-Vázquez, K., et al. (2007). Organic agriculture and the global food supply. Renewable Agric. Food Systems 22, 86–108. doi: 10.1017/S1742170507001640

Barbos, A., and Kaisen, J. (2022). An example of negative wage elasticity for YouTube content creators. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 203, 382–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2022.09.012

Bentley, J., Van Mele, P., Chadare, F., and Chander, M. (2022). Videos on agroecology for a global audience of farmers: an online survey of access agriculture. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 20, 1100–1116. doi: 10.1080/14735903.2022.2057641

Cahyani, D. D. A., and Arisena, G. M. K. (2023). YouTube as a source of information for agribusiness: audience perspective and content video analysis. Theor. Pract. Res. Econ. Fields 14:317. doi: 10.14505/tpref.v14.2(28).11

Carlisle, L., Esquivel, K., Baur, P., Ichikawa, N. F., Olimpi, E. M., Ory, J., et al. (2022). Organic farmers face persistent barriers to adopting diversification practices in California’s central coast. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 46, 1145–1172. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2022.2104420

Celidwen, Y., and Keltner, D. (2023). Kin relationality and ecological belonging: a cultural psychology of indigenous transcendence. Front. Psychol. 14:994508. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.994508

Chai, B. S., Chae, T., and Huang, A. L. (2024). Evaluation of educational YouTube videos for distal radius fracture treatment. J. Hand Surg. Global Online 6, 382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsg.2024.02.009

Chakma, K., Ruba, U. B., and Riya, S. D. (2022). YouTube as an information source of floating agriculture: analysis of Bengali language contents quality and viewers’ interaction. Heliyon 8:e10719. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10719

Charmaz, K. (2014). Grounded theory in global perspective. Qual. Inq. 20, 1074–1084. doi: 10.1177/1077800414545235

Chowdhury, L. H., Islam, S., and Shatabda, S. (2024). A Bengali news and public opinion dataset from YouTube. Data Brief 52:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2023.109938

Denzin, N. K., and Lincoln, Y. S. (2018) in The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. eds. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln. 5th ed (Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc).

Esteve-del-Valle, M., and Sarchosakis, F. A. (2025). The “algorithmic gatekeeper”: how Dutch farmers’ use of YouTube curates their views on the nitrogen crisis. Sustainability 17:3347. doi: 10.3390/su17083347

Farley, H. (2020). Promoting self-efficacy in patients with chronic disease beyond traditional education: a literature review. Nurs. Open 7, 30–41. doi: 10.1002/nop2.382

Flick, U. (2018). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research design. 2nd Edn. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Khasanah, M. K., Qudsy, S. Z., and Faizah, T. (2023). Contemporary fragments in Islamic interpretation: an analysis of Gus Baha’s tafsir Jalalayn recitation on YouTube in the Pesantren tradition. Jurnal Studi Ilmu Ilmu Al-Qur’an Dan Hadis 24, 137–160. doi: 10.14421/qh.v24i1.4389

Kress, G., and Leeuwen, T.Van. (2001). Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Landis, J. R., and Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33, 159–174

Lee, C. S., Osop, H., Goh, D. H.-L., and Kelni, G. (2017). Making sense of comments on YouTube educational videos: a self-directed learning perspective. Online Inf. Rev. 41, 611–625. doi: 10.1108/OIR-09-2016-0274

Li, B., and Hikmatilla, U. (2025). Getting viral on social media: exploring Chinese language EduTubers’ perceptions and practices. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 1–25, 1–25. doi: 10.1080/17501229.2025.2505700

Lijo, R., Castro, J. J., and Quevedo, E. (2024). Comparing educational and dissemination videos in a STEM YouTube channel: a six-year data analysis. Heliyon 10:e24856. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24856

Lombardi, G. V., Parrini, S., Atzori, R., Stefani, G., Romano, D., Gastaldi, M., et al. (2021). Sustainable agriculture, food security and diet diversity. The case study of Tuscany, Italy. Ecol. Model. 458:109702. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2021.109702

Mayer, R. E. (2024). The past, present, and future of the cognitive theory of multimedia learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 36:8. doi: 10.1007/s10648-023-09842-1

Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. IEEE Int. Symposium Industrial Electron. 1, 851–855. doi: 10.17169/fqs-1.2.1089

Mazurek-Kusiak, A., Sawicki, B., and Kobyłka, A. (2021). Contemporary challenges to the organic farming: a polish and Hungarian case study. Sustainability 13:8005. doi: 10.3390/su13148005

Mrazek, M. D., Dow, B. R., Richelle, J., Pasch, A. M., Godderis, N., Pamensky, T. A., et al. (2024). Aspects of acceptance: building a shared conceptual understanding. Front. Psychol. 15:1423976. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1423976

Novianti, W., Noegroho, A., Yamin, M., Lotulung, L. J. H., and Desmiwati, D. (2025). Comparative study of the utilization of social media by indigenous religious organizations in Indonesia: the cases of Paguyuban Budaya Bangsa and Lalang Rondor Malesung. J. Intercult. Commun. 25:30–45. doi: 10.36923/jicc.v25i2.1032

O’Halloran, K. L., Tan, S., Pham, D.-S., Bateman, J., and Vande Moere, A. (2018). A digital mixed methods research design: integrating multimodal analysis with data mining and information visualization for big data analytics. J. Mixed Methods Res. 12, 11–30. doi: 10.1177/1558689816651015

Ondrasek, G., Horvatinec, J., Kovačić, M. B., Reljić, M., Vinceković, M., Rathod, S., et al. (2023). Land resources in organic agriculture: trends and challenges in the twenty-first century from global to Croatian contexts. Agronomy 13:1544. doi: 10.3390/agronomy13061544

Parizad, S., and Bera, S. (2021). The effect of organic farming on water reusability, sustainable ecosystem, and food toxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 71665–71676. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-15258-7

Paull, J. (2011). Nanomaterials in food and agriculture: the big issue of small matter for organic food and farming. Proceedings of the Third Scientific Conference of ISOFAR, 96–99.

Popović-Djordjević, J. B., Kostić, A. Ž., Rajković, M. B., Miljković, I., Krstić, Đ., Caruso, G., et al. (2022). Organically vs. conventionally grown vegetables: multi-elemental analysis and nutritional evaluation. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 200, 426–436. doi: 10.1007/s12011-021-02639-9

Prasad, M. (2021). “Pragmatism as problem solving” in Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 7.

Ramavhale, P. M., Zwane, E. M., and Belete, A. (2024). The benefits of social media platforms used in agriculture for information dissemination. South Afr. J. Agric. Extension (SAJAE) 52, 77–90. doi: 10.17159/2413-3221/2024/v52n2a15342

Riffe, D., Lacy, S., Watson, B. R., and Fico, F. (2019). Analyzing media messages. London: Routledge.

Risien, J., and Goldstein, B. E. (2021). Boundaries crossed and boundaries made: the productive tension between learning and influence in transformative networks. Minerva 59, 539–563. doi: 10.1007/s11024-021-09442-9

Rosmarin, D. H., Chowdhury, A., Pizzagalli, D. A., and Sacchet, M. D. (2023). In god we trust: effects of spirituality and religion on economic decision making. Personal. Individ. Differ. 214:112350. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2023.112350

Sereenonchai, S., and Arunrat, N. (2024). Communication strategies for sustainable urban agriculture in Thailand. Sustainability 16:10898. doi: 10.3390/su162410898

Soriano, C. R., and Cabalquinto, E. C. (2024). “Digital Bayanihan as Method” in The Routledge companion to media audiences. (London: Routledge), 536–546.

Sudibyo, L. E. (2018). Narratives of teacher professional learning in Indonesia. Urbana: University of Illinois.

Tarsha, M. S., and Narvaez, D. (2023). The evolved nest, oxytocin functioning, and prosocial development. Front. Psychol. 14:1113944. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1113944

Winarnita, M., Bahfen, N., Mintarsih, A. R., Height, G., and Byrne, J. (2022). Gendered digital citizenship: how Indonesian female journalists participate in gender activism. Journal. Pract. 16, 621–636. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2020.1808856

Wolsey, T. D., and Lapp, D. (2019). Meaning-making. Int. Encycl. Media Liter. 1–12. doi: 10.1002/9781118978238.ieml0102

Keywords: organic farming, multimodal communication, informal learning, digital agricultural education, meaning-making, pedagogical identity, sustainable agriculture, community engagement

Citation: Sarwoprasodjo S, Mardiansyah I, Susanto T, Flor AG and Lubis DP (2025) Meaning-making in multimodal spaces: the role of YouTube in promoting organic farming practices in Indonesia. Front. Commun. 10:1620706. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1620706

Edited by:

Suhono Suhono, Institut Agama Islam Ma’arif NU (IAIMNU) Metro Lampung, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Cipta Pramana, Universitas Islam Negeri Walisongo Semarang, IndonesiaSurapon Boonlue, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, Thailand

Copyright © 2025 Sarwoprasodjo, Mardiansyah, Susanto, Flor and Lubis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarwititi Sarwoprasodjo, c2Fyd2l0aXRpQGFwcHMuaXBiLmFjLmlk

†ORCID: Sarwititi Sarwoprasodjo, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3371-677X

Iis Mardiansyah, https://orcid.org/0009-0007-4287-9876

Tri Susanto, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0828-248X

Alexander G. Flor, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5312-4443

Djuara P. Lubis, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2033-2187

Sarwititi Sarwoprasodjo

Sarwititi Sarwoprasodjo Iis Mardiansyah

Iis Mardiansyah Tri Susanto

Tri Susanto Alexander G. Flor

Alexander G. Flor Djuara P. Lubis

Djuara P. Lubis