- 1Faculty of Arts, Communication and Information Studies, and Rudolf Agricola School for Sustainable Development, University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

- 2School of Education, Applied Language and Literacy Studies, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

- 3Faculty of Science and Engineering, and Rudolf Agricola School for Sustainable Development, University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

- 4Faculty of Arts, English Linguistics and Rudolf Agricola School for Sustainable Development, University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

- 5Faculty of Arts, Applied Linguistics and Rudolf Agricola School for Sustainable Development, University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

- 6Faculty of Arts, American Studies and Rudolf Agricola School for Sustainable Development, University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

- 7Faculty of Arts, Communication and Information Studies and Rudolf Agricola School for Sustainable Development, University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

- 8Faculty of Arts, Communication and Information Studies and Jantina Tammes School of Digital Technology, Society and AI, University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

This position paper argues that critical language awareness (CLA) must be recognised as a core, future-oriented metacognitive competency. In our time marked by epistemic instability, discursive overload, and interconnected global crises, it is no longer sufficient for people to decode language; they must be equipped to question it, redesign it, and use it ethically to shape more just and sustainable futures. In this paper we review key disciplinary traditions concerned with the power of language and multimodal communication, including critical literacy, rhetoric, sociolinguistics, critical discourse studies, and ecolinguistics. Despite conceptual differences, we identify strong convergences: all treat language as constitutive of social realities and all call for awareness as a form of agency. Building on this shared ground, we propose a unified agenda for CLA that connects theory, practise, and transformation. We outline a new scope and five dimensions of CLA and frame it as a means of developing not only critical awareness, but communicative agency, advocacy, and activism. Scholars and educators can realise CLA’s potential by theorising, teaching, communicating, and operationalising it across disciplines and institutions. We argue that it is time to ‘see the water’: to make visible the linguistic forces that shape our world, and equip learners, educators, and citizens to reshape them.

1 Introduction

1.1 Why language?

Language and communication shape the conceptual foundations of our relationship with our physical and social environment by influencing our thinking—and, importantly, our actions. In our information-based society, major societal issues and our knowledge about them are constituted through text and talk. We are bombarded with (true and false) information, and influenced, cajoled, and persuaded via a range of media platforms. Language (used here in its broadest sense to include all meaning-making resources, from verbal signs to multimodal communication, from grammar to conversational implicatures) is everywhere, all the time—and this is why it somehow goes unnoticed, akin to the proverbial fish who are surprised to discover the substance in which they exist: water. Words, grammar, text and talk, as well as gestures, photos, and videos, are the metaphorical water we are swimming in. However, as Thompson (2003) notes, we “take language for granted, rarely pausing to consider what it involves or just how important it is to us” (p. 9).

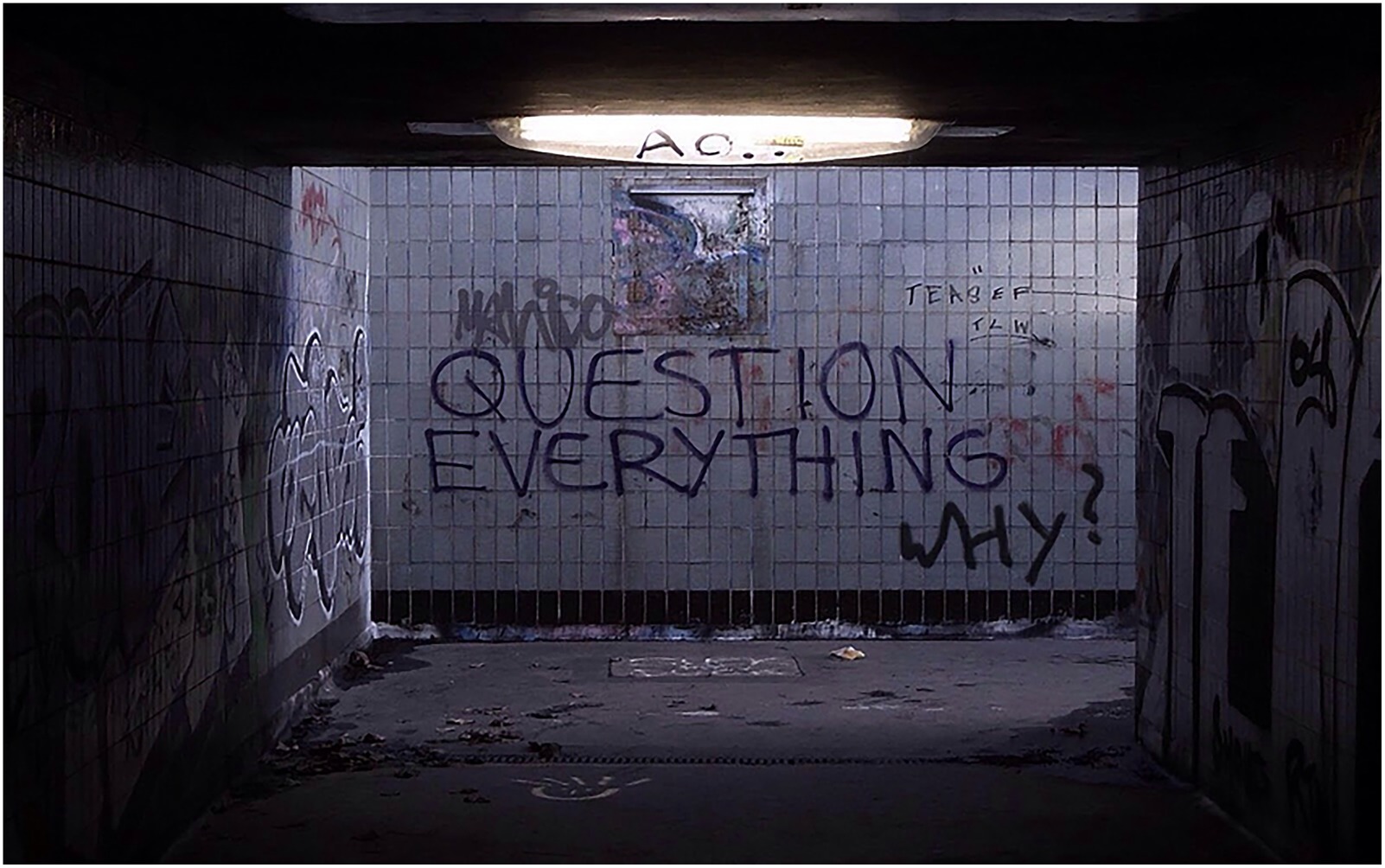

The issue is that we should not take it for granted—we should notice it, question it, and challenge its power (see Figure 1), because it does have immense power. For example, just reading texts that describe extrinsic values is enough to influence people’s attitudes and behaviour, making them less compassionate and less likely to engage with the community or in responsible behaviour (Stibbe, 2019). Adding visuals to such a text can further shape public perceptions and behaviour—by increasing the sense of importance of a particular issue (O’Neill et al., 2013) or by promoting feelings of being able to change something (O’Neill and Nicholson-Cole, 2009). The power of such verbal and multimodal communication is particularly apparent when we consider media reporting, where it has a direct influence and significant impact on the public’s belief in democracy, its confidence in politics, and its faith in the rule of law (Serafis, 2023). Recent works like Koller et al.’s (2019) volume on the discourses of Brexit and McIntosh and Mendoza-Denton’s (2020) collection on language in the Trump era, or Parnell et al.’s (2025) volume on the discourse of the polycrisis1 (see section 1.2) provide compelling cases for this profound and wide-reaching influence.

Figure 1. Question everything (nullius in verba) take nobody’s word for it, Artist: Dunk on Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/dullhunk/, CC-BY 2.0.

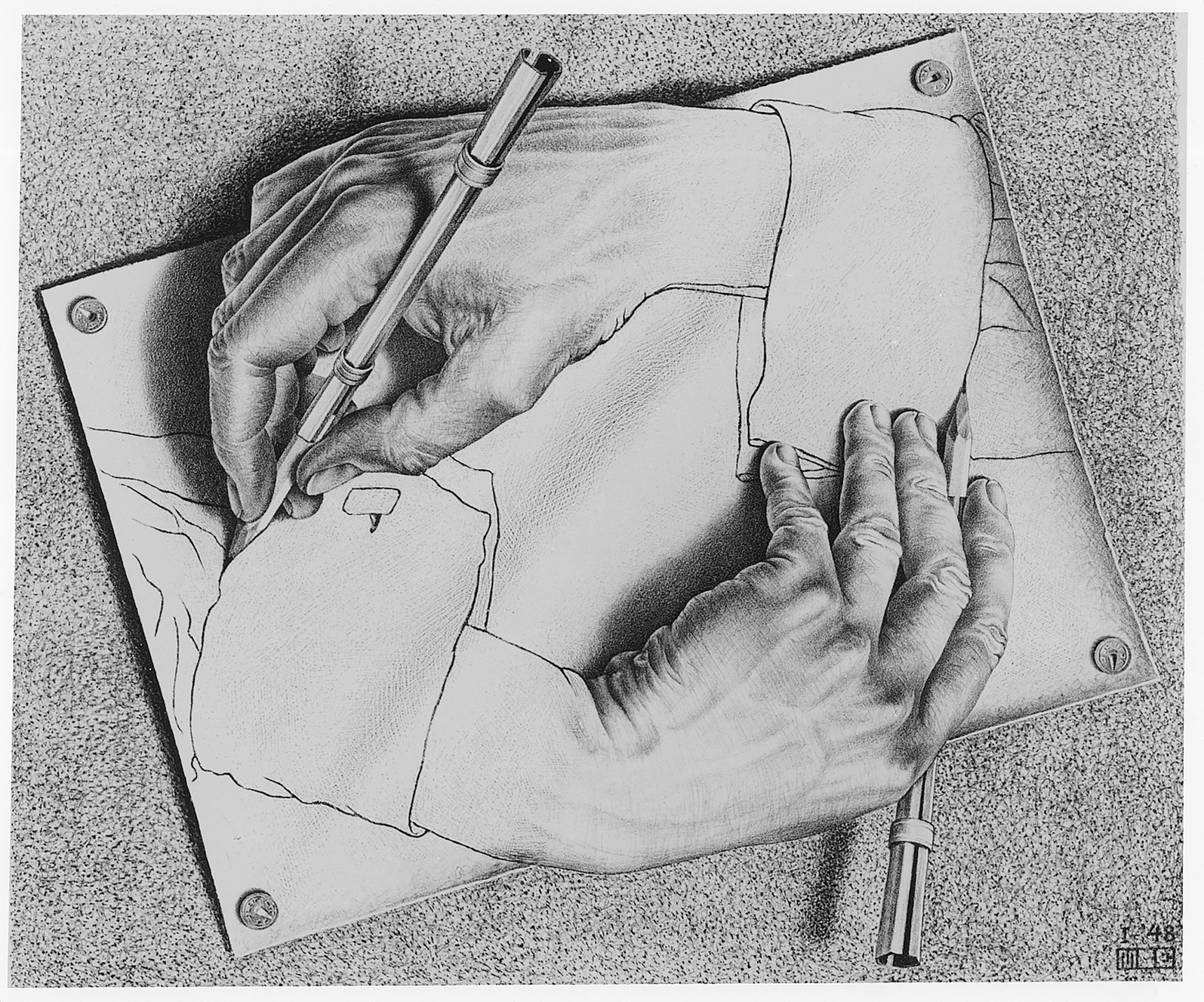

This position paper builds on a social constructionist understanding of language, namely, that language is not a ‘mere’ reflection of reality the way a mirror reflects an image (Potter, 1996, p. 7). In a social constructionist understanding, as proposed by Berger and Luckmann (1991) in their seminal work The Social Construction of Reality [1966], our reality is not a fixed entity but rather (re)produced in our communicative and social practises. We ‘talk’ our social worlds into being (see similar arguments by Burr, 1995; Clark, 2016; Fairclough, 1992; Foucault, 1972; Jørgensen and Phillips, 2002; Potter, 1996; Shotter, 1993). A useful illustration of this is Escher’s lithograph Drawing Hands (Figure 2): our ways of talking and writing are shaped by conventions and lived experience, yet at the same time, our perception of reality is constructed through language itself. Language is not simply a medium but a constitutive force—much like the water for our proverbial fish, it actively shapes and conditions our experience of the world.

Figure 2. M.C. Escher’s “Drawing Hands” © 2025 The M.C. Escher Company-The Netherlands. All rights reserved. www.mcescher.com.

There is an important aspect of this medium—our metaphorical water—that is often overlooked: it is never pure or transparent. A text is always constructed from a particular viewpoint, with a communicative purpose and an intended effect (Duffelmeyer and Ellertson, 2005). The common-sense assumption that language simply represents an objective reality is highly problematic, as Burr (1995) warns, because language filters, frames, and conditions what we perceive (p. 54). Subtle shifts in language can radically affect what people perceive as true or important. Often, this effect is explicitly utilised: a striking recent example is the current US president Trump’s large-scale removal of terms related to gender identity, climate change, and racial equity from government websites and documents (Yourish et al., 2025). This is not simply a matter of swapping or omitting words: it is about redefining what could be acknowledged and acted upon, what is legitimate public debate (Krzyżanowski et al., 2023).

The ability to recognise that language is never neutral and that it shapes our understanding of the world is crucial. This ability is becoming, as Fairclough (1992) argues, a prerequisite for effective democratic citizenship, because “people cannot be effective citizens in a democratic society if their education cuts them off from a critical consciousness of key elements within their physical or social environment” (p. 6). In response to this fundamental educational need, there is growing recognition of the importance of media literacy, digital and AI literacy, data literacy, and bias literacy—something already acknowledged in the early work on the ‘pedagogy of multiliteracies’ (New London Group, 1996; Kalantzis and Cope, 2025). Multiliteracies are understood as so-called meta-literacies that provide meta-languages to describe and analyse the different elements and complex configurations in our daily communication. For example, Kress and van Leeuwen’s (2020) [1996, 2006] concept of ‘visual grammar’ shows how visual design operates according to explicit and implicit rules and conventions—illustrating that meaning-making is structured and never neutral, even beyond verbal language.

Yet, amid this growing number of literacies prioritised at various levels of education and policy, the foundational role of language and multimodal meaning-making is too often treated as an afterthought—or not considered at all: as if we could critically navigate visuals, data, and AI without first understanding the discursive forces that make them meaningful, powerful, or indeed harmful.

1.2 Why language now?

We live in an era of polycrisis, where multiple, interconnected global challenges are unfolding at an existential scale. Environmental degradation, climate change, growing economic disparities, the erosion of democratic values, war, and global health crises do not exist in isolation. They are interlinked, reinforcing each other in ways that shape the future of humanity. Yet, whilst these crises have very real material consequences, our knowledge, understanding, and experience of them is also to a great extent discursive. Some of these processes, especially at a global scale, are not directly perceptible to individuals. Instead, they are constructed and mediated through language, shaped by grand narratives, media representations, public discourse, and interactions across digital platforms. Experiences of them are, quite literally, talked into existence.

Take climate degradation, for example. This crisis unfolds on a vast spatiotemporal scale which may transcend direct human perception. Whilst people certainly experience its effects, we do not experience the full extent of the crisis directly; we come to understand it through the words and images of scientists, policymakers, the media, and activists. The discourse around climate change does not just describe the crisis—it actively constructs it, determining what is acknowledged, debated, and acted upon (Alexander, 2010; Stibbe, 2015). Terms like ‘environment,’ ‘ecology,’ and ‘sustainability’ are not objective realities but contested concepts, filtered through competing voices and illustrated, for example, by visuals of planet Earth burning or melting (see Figure 3).

Even when we directly experience phenomena such as extreme weather events, deforestation, or air pollution, the way these issues are framed and communicated shapes how we perceive and respond to them. The presentation of climate change in the media (Augé, 2023; Chau et al., 2022; Gillings and Dayrell, 2024; Wang et al., 2022), in public policy (Bevitori and Russo, 2025; Ala-Uddin, 2019; Maci, 2025), and in corporate and business communication (Chmiel et al., 2025; Stibbe, 2023) directly impacts public understanding and action. As Fenton (2022) puts it, climate change can be seen as a ‘communication failure’: we have failed to construct narratives powerful enough to change humanity’s trajectory towards environmental collapse.

The role of language and communication is just as—if not more—significant concerning complex issues that are immaterial and intangible, such as distrust in democracy, mis- and dis-information, and artificial intelligence. Well-engineered or unintentional shifts in discourse normalise and legitimise anti-democratic actions (see Krzyżanowski et al., 2023). Public institutions and social media reshape what is seen as legitimate knowledge, or indeed, truth (Demata et al., 2022). Technological innovations, especially artificial intelligence (AI), now act as ultimate accelerators of this epistemic instability by both drawing on and reshaping existing discourses.

As historian and philosopher Harari (2024) warns, by mastering language, AI has effectively hacked the operating system of human civilization:

By gaining such command of language, computers are seizing the master key unlocking the doors of all our institutions, from banks to temples. We use language to create not just legal codes and financial devices but also art, science, nations and religions. What would it mean for humans to live in a world where catchy melodies, scientific theories, technical tools, political manifestos and even religious myths are shaped by a non-human alien intelligence that knows how to exploit with superhuman efficiency the weaknesses, biases and addictions of the human mind? (Harari, 2024, p. 208).

1.3 What now?

Harari’s reflection captures the stakes well: the mastery of language by artificial intelligence could give computers such immense influence that it may lead to the end of human history as we know it. This is an outcome we would very much like to avoid. Now is the moment, we argue, to reclaim mastery over language—not through machines, but through human awareness and education.

This call is not a novel idea. History offers evidence for why linguistic consciousness is essential to human survival and agency. The power of language and communication was already well recognised in Western antiquity. Mastery of rhetoric was seen as essential for participation in public life, law, governance, and philosophy—albeit limited almost entirely to male citizens. The idea that language is power was not a radical proposition but a fundamental truth, and people had first-hand familiarity with rhetoric’s capacity for persuasion and manipulation. This prominent role of rhetoric began to fade with the authoritarian regimes of the Roman Empire and the advent of Christianity, both of which had little use for this type of critical thinking. However, rhetoric never fully disappeared and would reemerge cyclically, often in response to the types of crises described by Harari. Today, it continues to inspire critical thinking about the role of language in shaping our perception of reality.

A second source of evidence for the importance of linguistic awareness comes from a recent revival of linguistic relativism, particularly regarding how language encodes humans’ relationship with the environment. Research in ecolinguistics and linguistic anthropology shows that different languages and Discourses2 within languages structure human thought in ways that shape how people interact with the world (Kimmerer, 2013; Stibbe, 2023; Li et al., 2020). Language impacts ecological systems through accumulated knowledge and cultural traditions that are passed on over time, influencing nature across longer timescales (Steffensen and Fill, 2014). Conversely, nature influences language use in everyday communication (e.g., how weather is discussed in small talk), and can even shape the vocabulary, grammar, and sound systems of languages (Levinson, 2003; Everett et al., 2015; Petrollino, 2022), including ways of adapting to environmental change (Steffensen and Baggs, 2024).

This position paper argues that it is necessary to (re)claim our ability to master language—to become aware of how it surrounds us, just as the anecdotal fish became aware of the water—and to recognise its socially constitutive power and non-neutrality. This competency, called critical language awareness (CLA), is fundamental for navigating the complexities of our time.

We argue that CLA as a competency is a prerequisite for human agency, democratic participation, and—more broadly—for shaping futures on terms defined by citizens and communities themselves, rather than passively accepting realities constructed through dominant discourses, institutions, and media.

This argument aligns with broader educational efforts that aim to respond to rapidly shifting global realities (see, e.g., Nussbaum, 2011; Perkins, 2014; OECD, 2025). Scholars working in existential sustainability argue that systemic change must be driven by a deeper shift in human consciousness, that our core stories and assumptions about what matters—what is human, what is valuable—must be revisited (Wamsler et al., 2021; Kopnina, 2020; Stibbe, 2024b). This kind of discursive consciousness is fundamental to “shifting mindsets and advocating new paradigms” (Bristow et al., 2024, p. 8). The role of education—and educators—in this process cannot be overstated: education needs to play a pivotal role in addressing “the emergent meanings of everything” by providing a “new, holistic frame of reference” (Cope and Kalantzis, 2022; p. 1733). CLA offers such a frame, and with it the tools to notice, reflect on, and reorient emergent meanings.

From its earliest formulations, the concept of CLA included a strong focus on transformation. Already back in the 1990s, Clark et al. (1991) argued for the development of “fully-fledged non-oppressive alternatives to dominant discourse conventions” (p. 46). In this sense, CLA has always been about reimagining language use—and through it, reimagining the social world. Awareness, in this tradition, is not an end point but a starting point. As Freire (2021) reminds us [1973], conscientização—the development of critical consciousness—entails moving from recognition to reflection, and from reflection to action—a trajectory we will discuss later in the paper.

Seen in this way, CLA can be understood as a tool of conscientização, and it is precisely this orientation that holds its educational potential. Early developments in CLA research highlighted this, particularly as a means of empowerment, critical thinking, and analytical engagement (Clark et al., 1990, 1991; Clark and Ivanič, 1997; Fairclough, 1992; Janks, 1997). More recent scholarly work (Darics, 2019, 2022; Montessori, 2020; Weninger and Kan, 2013) and initiatives, such as the CLA collective,3 or the CLADES project4 showcase and research CLA’s potential in literacy, civic and professional education.

However, despite growing interest in CLA, and despite its relevance as a future-oriented competency, research and educational interventions largely remain confined to the language classroom—as reflected in The Routledge Handbook of Language Awareness (Garrett and Cots, 2018), various edited volumes (James and Garrett, 2014), and the aims and scope of the journal Language Awareness.

We argue that CLA must gain widespread integration into all disciplines in education (see 3.1), as well as into professional training and policy-making. This paper aims to take the first step towards that goal. Specifically, we seek to:

• Set a forward-moving agenda for CLA theory and practise, particularly in the context of future-oriented education.

• Provide a platform that brings together CLA as a concept and practise across different schools of thought and disciplines.

To achieve these aims, we will first examine areas of scholarship concerned with knowledge about language, communication, and discourse consciousness. Whilst the critical role of language awareness is addressed across multiple disciplines, these discussions often remain fragmented, drawing from different conceptual foundations and diverging in their terminology and educational applications.

This paper seeks to bring these conversations together. In Section 2, therefore, we provide a brief overview of key scholarly fields, including critical (multimodal) literacy studies, rhetoric, relevant aspects of sociolinguistics, critical discourse theory, and ecolinguistics. In Section 3, we identify the convergences between these fields which we use to outline a CLA agenda: its scope and dimensions of awareness, and its transformative potential. A note is due here: whilst we strive to support our argument with a broad scholarly base, we recognise that this review is necessarily selective. We apologize to thinkers and scholars whose work we may have overlooked and hope that this paper serves as a starting point for ongoing conversations and further advocacy for CLA in society.

We briefly touch on this latter point in Section 4 by situating CLA within the rapidly evolving landscape of education and proposing an agenda for future work that demonstrates why CLA must be recognised as a core competency in future-oriented learning frameworks.

2 Fragmentation

In the previous section, we used water as a metaphor for language—something we are immersed in, yet often fail to notice. We made a case for paying attention to this metaphorical water because it is more than just an environment we exist in; it actively shapes our perceptions, interactions, and relationships with both the physical and social world.

Water is also a precious resource, one that is under pressure (just like some languages). Addressing the complex global issues related to water requires considering its many interwoven challenges: climate change, geopolitics, infrastructure, agriculture, or human rights. This is why interdisciplinary platforms need to bring together scholars from across disciplines—scientists, social scientists, and humanities researchers—each offering a different perspective on the same fundamental substance. For the chemical engineer, water is a molecular structure. For the diplomat, it is a political resource. For the poet, it is a symbol.

Scholars approach language and meaning-making in much the same way. Their terms, questions, and priorities are shaped by the disciplinary contexts they operate in. Yet, despite these differences, they are often engaged with the same fundamental phenomenon: language as a central force in shaping our social world. The challenge, however, is that the insights from these disciplines often remain isolated and confined to them. As a result, important advances in thinking about CLA remain fragmented, limiting the potential for shared insights and broader impact. In what follows, we discuss a non-exhaustive number of fields that share strong links with CLA to give an impression of this fragmentation.

Critical literacy studies (CLS) is one such field. Given its orientation towards application, CLS emphasises doing critical literacy (Janks et al., 2013). It is unsurprising, then, that critical literacy approaches are predominantly adopted in language classrooms and teacher training programmes, at the same time acknowledging literacy as multiple and multimodal (Lim and Tan, 2018). In the current age of misinformation and fake news, these approaches are increasingly valuable. They help young people critically examine not only what is being communicated, but also how and why—fostering deeper awareness of the intentions, values, and power relations embedded in everyday texts. Thus, if language, and other expressive forms such as image or video, is our metaphorical water, CLS can be seen as offering swimming lessons: equipping students and teachers to navigate the overwhelming ocean of information around them. By learning to analyse and redesign texts across modes, CLS encourages learners to question dominant and often problematic discourses, and to recognise their own role in shaping more equitable and conscious forms of communication.

Another discipline of note is Rhetorical Criticism, which brings together scholars from argumentation theory, literary criticism, history, philosophy, and many other fields around a shared interest: how language fosters, reinforces, and challenges our perceptions of reality. The power of language to persuade and shape perceptions is as central to the discipline of rhetoric as it is to CLA. Similarly to CLA, rhetorical criticism emphasises the importance of critical awareness. The “critical” aspect refers not just to analysing technical or aesthetic quality, but to recognising what is foregrounded or backgrounded, what perspectives are legitimised or marginalised, and what realities are constructed through language. Critical rhetorical practise demands more than observation: As Klumpp and Hollihan (1989, p. 91) argue, the rhetorical critic must “interpenetrate rhetorical processes into the society of which s/he is part.” Awareness involves understanding both the ethical responsibility of the rhetor and the critical agency of the audience.

The field of sociolinguistics, which analyzes the relationship between language and society, is another discipline that shares many links with CLA. Despite its breadth, sociolinguistics consistently highlights three interrelated themes that align closely with social constructionism and the goals of CLA: language variation and identity construction; language ideologies, attitudes and power structures; and language loss and preservation of linguistic diversity. Together, these three strands underscore that language is not a neutral medium but a central mechanism through which social realities are constructed, contested, and reproduced. They demonstrate that linguistic practices shape who we are, who we can become, and what possibilities are available to us. Developing CLA is therefore not simply a matter of linguistic or semiotic competence—as we will see in section 3, it is a matter of understanding that language diversity matters to communities and speakers, as an important prerequisite for social justice and individual agency, i.e., for the ability of everyone to access resources and participate meaningfully in an unequal and shifting world (see also Sauntson et al., 2025).

Yet another example is the field of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA)—more recently referred to as critical discourse studies (CDS)—emerged in the late 20th century as a distinct approach to studying language in social context. Drawing from diverse theoretical traditions—including Marxist theory, Gramscian hegemony, Foucauldian discourse theory, Bourdieu’s sociology, and Habermas’s critical theory—CDA/CDS focuses on how discourse constructs, maintains, and challenges power relations (Wodak and Meyer, 2016; Flowerdew and Richardson, 2018). This field, too, has in recent years increasingly acknowledged the importance of multimodality, recognising that meaning-making in contemporary communication extends beyond language alone. Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis (MCDA) expands the scope of traditional CDA/CDS by incorporating the analysis of visual, auditory, spatial, and embodied modes alongside verbal language. One key insight from CDS is that ideological discourses are not simply imposed by elites (Serafis and Assimakopoulos, 2025) but are often internalised and reproduced even by marginalised or stereotyped groups themselves (Archakis and Tsakona, 2022, 2024). This pervasive nature of discourse power underscores the necessity of CLA for all citizens—not only as consumers of information but also as participants in meaning-making practises. Notably, it was Norman Fairclough—a leading figure in CDA/CDS—whose early volume explicitly linked Language Awareness and Critical Discourse Analysis (Fairclough, 1992). Although Fairclough’s vision of CLA did not become as influential as his contributions to CDS itself, the central claim remains highly relevant:

Given that power relations work increasingly at an implicit level through language, and given that language practises are increasingly targets for intervention and control, a critical awareness of language is a prerequisite for effective citizenship, and a democratic entitlement (Fairclough, 1992, p. 12).

The final field we want to note is Ecolinguistics, which is not a single unified discipline but a transdisciplinary movement (Stibbe, 2024b). Broadly, it studies how language shapes and is shaped by interactions between human beings, non-human beings, and the biophysical environment (Steffensen, 2024, p. 524), in ways that ultimately affect the conditions for life on Earth (p. 522). Despite the field’s diversity, a major strand of ecolinguistic research critiques the ways language both reflects and constructs human relationships with the more-than-human world (Li et al., 2020). This approach moves beyond treating language as merely descriptive: language shapes worldviews, values, and behaviours towards the environment. Ecolinguistics draws on the idea that we live through “stories” or mental models—simplified structures in the mind that guide perception and action (Stibbe, 2021). Some stories are so deeply ingrained that they become invisible, much like the proverbial water for the fish. Ecolinguistics shares with CLA the goal of making hidden structures visible—fostering agency and critical perception. Initiatives like the Stories We Live By course (Roccia and Iubini-Hampton, 2021) demonstrate how ecolinguistic approaches can be used to educate broader publics, not just academic audiences. Participants who took the course reported newly acquired knowledge that altered their conceptions of language, society, and daily choices—highlighting the transformative potential of critical eco-linguistic awareness.

3 Convergence

In the previous section, we showed that despite historical and conceptual differences, each discipline shares a common epistemological position: language plays a crucial role in shaping perceptions of reality, and ‘awareness’ is central to understanding this process. In this section, we shift our focus to the points of convergence: we specifically explore the scope and dimensions of CLA as reflected in the current state of the art, leading towards a discussion of CLA’s transformative potential in Section 4.

3.1 Scope of CLA

The first point of convergence concerns the scope of CLA. Across the disciplines we have reviewed, CLA emerges not only as an educational practise but as a broader civic competency: an essential foundation for recognising, questioning, and intervening in how language shapes inequalities and social and physical realities. Bringing CLA into educational and public life requires acknowledging that language practises are not just matters of communication, but sites where power is exercised and contested. As Blommaert and Bulcaen (2000) argue, critical language work should not only expose the social dimensions of discourse, but actively empower those who are marginalised by them, amplify silenced voices, and mobilise change. This is the orientation we advocate in this position paper, contributing to the broader vision of CLA as a means of democratic engagement and social transformation (Clark et al., 1990, 1991; Fairclough, 1992; Janks, 2009).

CLA has an established presence in language and writing education (Shapiro, 2022), in challenging standard language ideologies (Rampton, 2002; Razfar and Rumenapp, 2012), and in bilingual and multilingual education (Beaudrie et al., 2021; Hélot, 2003). However, we argue that CLA must be embedded across all levels of education, particularly in curricula focused on developing critical thinking, democratic participation, and ethical citizenship. It must now move into domains where critical awareness of language is less expected. Fields such as management and leadership education (Darics, 2019, 2022; Cohen et al., 2005; Handford et al., 2019; Stibbe, 2024a), science education (Barwell, 2020; Kress et al., 1998), healthcare and health communication (Galasiński and Ziółkowska, 2022; Spilioti et al., 2019; Pitkänen and Vaattovaara, 2024), and teacher education (Cummins, 2023; James and Garrett, 2014; Lindahl, 2019; Chi and Rolstad, 2024) all urgently require CLA. Moreover, CLA must extend beyond formal education systems. Populations outside structured learning environments—for example, some older adults, who have been shown to be particularly vulnerable to misinformation (Moore and Hancock, 2022; Grinberg et al., 2019; Guess et al., 2019; Loos and Nijenhuis, 2020)—also require support in developing critical language competencies.

In an era increasingly shaped by digital disruption, ecological crisis, and failures of democratic and epistemic systems, CLA must be recognised as a foundational metacognitive competence—not an optional nice-to-have, but an imperative for navigating the complexities of contemporary life.

3.2 Dimensions of CLA

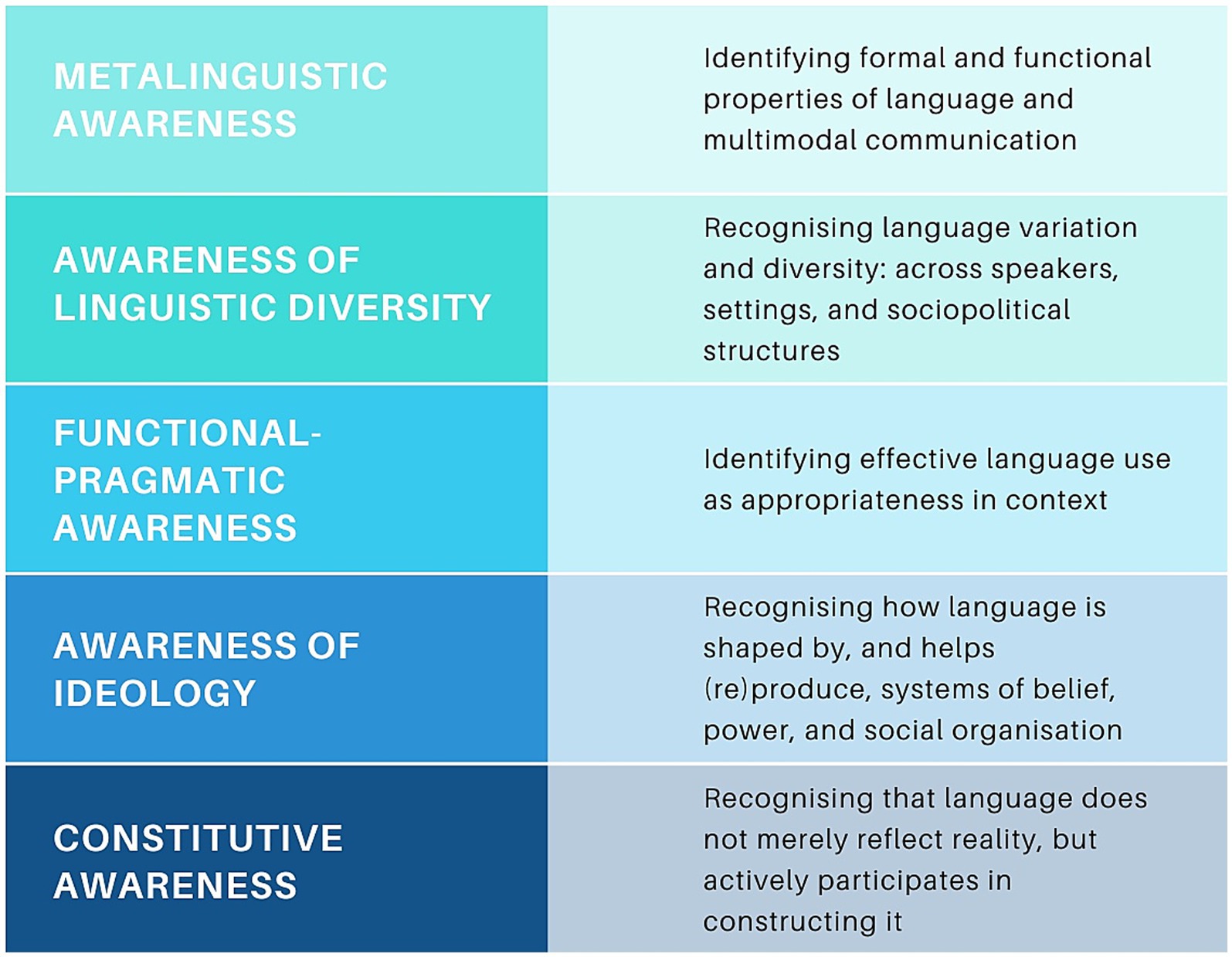

Another point of convergence, one not always acknowledged within the disciplines themselves, emerges when we step back from their siloed perspectives: language awareness is multidimensional. Whilst each subfield tends to foreground specific aspects of language, taken together they offer a complementary and cumulative picture of what it means to be critically aware of language and multimodal communication in society (see Figure 4).

3.2.1 Metalinguistic awareness

The first dimension concerns the ability to notice and analyse the formal and functional properties of language and multimodal communication. This includes awareness of structural levels such as phonetics, syntax, and grammar, as well as discursive resources and strategies such as lexical choice, modality, framing, or metaphor, and the relationships between these elements. Across the disciplines reviewed, attention to the micro-level of language is fundamental: critical literacy studies approach it through systemic functional grammar (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2013), critical discourse studies through textual analysis (Fairclough, 2003), and multimodal studies through the development of metalanguages (Cope and Kalantzis, 2020; Lim et al., 2022; Bateman, 2022; Wildfeuer and Lehmann, 2024).

Metalinguistic awareness is not limited to recognising various features; it involves understanding their effects. How a text is constructed shapes how it is interpreted. Across disciplines, metalinguistic awareness provides the vocabulary and interpretive lens needed to critically engage with the discursive construction of reality.

3.2.2 Awareness of linguistic diversity

The second dimension concerns recognising the importance of linguistic diversity, including how language use varies across speakers, contexts, and sociopolitical structures.

It includes understanding dialects, sociolects, multilingual repertoires, code-switching and translanguaging practises (Wei, 2018; Jørgensen, 2008; Rampton, 2011). The burgeoning field of critical multilingual language awareness is a case in point (De Costa and Van Gorp, 2023; Garrett and Cots, 2018).

It encompasses the maintenance and revitalisation of endangered, minoritized, and Indigenous languages, to counteract linguistic imperialism (the [violent] domination of a few languages over others, guided by a dominant culture’s economic power, Phillipson, 1992) and linguicide (the deliberate neglect or even the planned suppression of a language that is deemed useless or even undesired, Skutnabb-Kangas and Phillipson, 1995).

This dimension of awareness is urgent and of crucial importance: In 2025, about 43% of the world’s languages are classified as endangered by UNESCO. Indigenous languages embody worldviews and are perceived as a spiritual gift by many Indigenous peoples. The language nêhiyawêwin or Plains Cree (Canada) for example aligns with the natural environment by naming the colours after natural elements, like rivers (blue), earth (green) and blood (red), and does so for the name of the months and the trees (Daniels et al., 2025). Languages are instrumental to achieve alternative sociopolitical set ups, as for example one based on Indigenous food sovereignty (DeCaire, 2023 on Kanien’kéha or Mohawk, Canada/USA). Moreover, research shows that the maintenance and vitality of Indigenous languages are protective factors in fostering health and wellbeing for community members (Harding et al., 2025). Cognitive development and learning in the early years is most effective when instruction occurs in the mother tongue, as multiple research projects demonstrated (cf. one for all, the Ife Six-Year Primary Project, Nigeria, Fafunwa et al., 1989). CLA advocates for the vital role of Indigenous languages in achieving agency and justice for minoritized peoples worldwide.

Awareness of linguistic diversity also means recognising the ideologies behind linguistic hierarchies: why some languages are worth preserving whilst others are disposable, why certain language varieties are valorised as ‘standard’ and others marginalised (Lippi-Green, 2012; Milroy, 2001). Standard language ideology operates as a gatekeeping mechanism: it restricts access to education, employment, and social mobility, and speakers of non-standard varieties are often perceived as deficient. This ideological positioning is standard practise, and it is rarely flagged, which brings tangible consequences. Linguistic discrimination—rooted in standard language ideologies—occurs both overtly and covertly across many professional domains (including in legal, educational, policy, or healthcare contexts, at work or in the housing sector, see Du Bois, 2019; Cummins, 2018; Mahili and Angouri, 2015; Tollefson, 1991; Rickford and King, 2016). Whilst frameworks like the Council of Europe’s Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture (Council of Europe, 2016) promote diversity awareness, they stop short of addressing these ideological dimensions. CLA fills this gap by making visible the power relations that define what counts as legitimate language and by challenging the marginalisation of minoritising practises in education and society.

3.2.3 Functional-pragmatic awareness

Another point of convergence is the recognition that effective language use is not about correctness in the abstract, but about appropriateness in context. Across the disciplines we reviewed, there is a shared emphasis (though not always explicitly named) on developing awareness of how communicative choices are shaped by social purpose, audience, medium, and genre. This form of awareness includes the ability to recognise and interpret how different genres—such as a news article, a campaign slogan, a scientific report, or a social media post—work to achieve their communicative goals, whether through language or visual design. It also involves understanding how formal features are shaped by, and in turn shape, the social situations in which texts circulate. This knowledge may include for example critical awareness of argumentative structures (Palmieri, 2022), narrative framings and storytelling strategies (Mäkelä and Meretoja, 2022), genres (Devitt, 2009) or metaphorical choices (Alvesson and Spicer, 2011).

Functional-pragmatic awareness also means being able to adapt one’s own language practises strategically and ethically across contexts—a form of situated communicative competence often foregrounded in rhetorical education, genre-based pedagogy, and multiliteracies frameworks. This awareness relates closely to issues of access and agency. As Clark et al. (1990) argue, empowering learners to access and critically engage with the ‘right’ kinds of discourse is key to participation in public, professional, and civic life.

This dimension of CLA is particularly relevant in professional domains where communication is not just a tool but the core product. In today’s knowledge economies—across contexts ranging from PR and marketing to customer service, translation, speechwriting, and copywriting—communication is the practise itself. Yet, whilst the symbolic output of these language workers underpins entire industries (Thurlow, 2019), even experienced communicators often lack the metalinguistic vocabulary and tools to critically reflect on how they produce meaning (Koller, 2018; see also Bateman, 2022). This is precisely where functional-pragmatic CLA becomes crucial. Making invisible language work visible and subject to reflection is essential for developing ethical, reflexive communication practise.

3.2.4 Awareness of ideology

The fourth dimension recognises that language is shaped by and reinforces ideological beliefs and social inequalities. Ideological awareness allows us to ask whose interests are served. Foundational insights, mostly from CDS, illustrate how discourse legitimises inequality and normalises specific worldviews (Gee, 2012), whilst promoting ideological awareness (see 2 above, also Fairclough, 1995; van Leeuwen, 2007, 2008; Krzyżanowski and Forchtner, 2016). The ideological dimension was also central to the emergence of CLA, where it was positioned as a pedagogical response to the hidden ideological work of language (Clark et al., 1990; Fairclough, 1992; Janks, 1997, 2009), which in turn enables individuals to see language as a site of struggle over meaningful constructions of reality.

3.2.5 Constitutive awareness

The final and perhaps most far-reaching dimension is constitutive awareness: the recognition that language does not simply describe the world but plays a central role in constructing it. Whilst ideological awareness focuses on the reproduction of power through discourse, constitutive awareness foregrounds language as a primary force in creating social facts, relations, and institutions.

Constitutive awareness integrates all previous dimensions—metalinguistic, diversity, functional-pragmatic, ideological—into a full realisation of the socially constitutive power of language and multimodal meaning-making. It is the moment of explicit awakening, when language use is no longer seen as a transparent medium but as a dynamic agent shaping reality itself. This is the moment when the fish discover the water, or as James and Garrett (2014, p. 5), describe, the bridge through the consciousness gap, where our natural ability to use language, our implicit knowledge of and about it turns into conscious, explicit knowledge. This metacognitive step includes not only the realisation of how language constructs the world, but the recognition of our own role in shaping it. This awareness lays the groundwork for CLA’s true transformative potential, as we will discuss below.

4 CLA’S transformative potential

In the scholarly areas reviewed above, a shared aim becomes evident: to move from noticing to action. Across all these fields, noticing is not an end in itself: it is the first step in a larger reflective and ethical practise that asks how meaning is made, by whom, for what purpose, and with what consequences.

But awareness alone is not enough. As is evident in our collective response to issues as varied as the dangers of smoking, excessive air travel, or intensive livestock farming, knowing something rarely leads to acting on it by default. What is often missing is a bridge between noticing and doing: the reflective space in which people decide how to relate to—or act on—what they have become aware of. We have already mentioned Freire’s conscientização (the development of critical consciousness) (Freire, 2000; Freire, 2021) which is inseparable from praxis: the joint process of reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it. This ‘bridging’ process is also central to awareness-based systems change models such as Theory U (Scharmer, 2018), which suggests that real change begins with “seeing” the current system with fresh eyes, followed by “sensing” one’s connection to it, and then “presencing”—a pause to reflect and choose how to move forward. Only after this deep awareness and stance-taking does effective action become possible.

CLA supports this same arc: it enables us to notice elements, variation and diversity, function, encoded ideologies and constitutive power—and to take responsibility for how we relate to them, and what we choose to do next.

4.1 From awareness to action: a note to ourselves

If CLA is to contribute to transformation, it must begin with the recognition that we—researchers, academics, educators—are participants in the discursive world we seek to understand and reshape. In a constructivist, anti-positivist framework, observation is never neutral: knowledge does not emerge independently from experience, but is always mediated by the categories, metaphors, and narratives through which we frame it. As Heller et al. (2018, p. 74) note, “knowledge does not derive directly from evidence or experience but is mediated by how we choose to formulate it and represent it in specific contexts of communication.” This means that awareness must also include our own language use and positionality as researchers, educators, and communicators.

In the same way we ask students to question assumptions in texts, we must be attuned to the discursive framings that shape our own institutions, our practises, our writing and research questions, and our criteria for what counts as ‘knowledge’ (for a critical investigation of the discourse of neoliberal academia, see Morrish and Sauntson, 2019; for a reflection on scholarly writing practises see Sauntson et al., 2025). CLA must begin with our own practise: after all, as Thurlow notes, “without a proper reflexivity of our own, we remain conveniently unaware of the normative, language-ideological entanglements of our approaches to language” (2019, p. 7).

And just as we have argued for moving from noticing through reflection to action, that same imperative applies to us as scholars. Yet this move is often countercultural in academia. Researchers are typically trained to observe, not to intervene. With the exception of traditions like rhetoric—where inventio and actio are integrally linked—many in CDS/CDA, ecolinguistics, or sociolinguistics still treat awareness-raising as the end goal, assuming that change will follow once others recognise the power of language. But if transformation is what we seek, then our own discursive accountability—our willingness to act as well as analyse—must be part of our agenda. This includes challenging the dominant values and discourses we are analysing, reflecting on our own biases, and resisting professional norms that reward detachment over engagement (see Serafis and Bennett, 2025). It also means questioning the academic monopoly on critical metalanguage: as Spencer-Bennett (2021) argues, everyday speakers are often already well aware of the politics and power of communication, and these insights should be taken seriously as foundations to ensure societal impact of our work (see section 5).

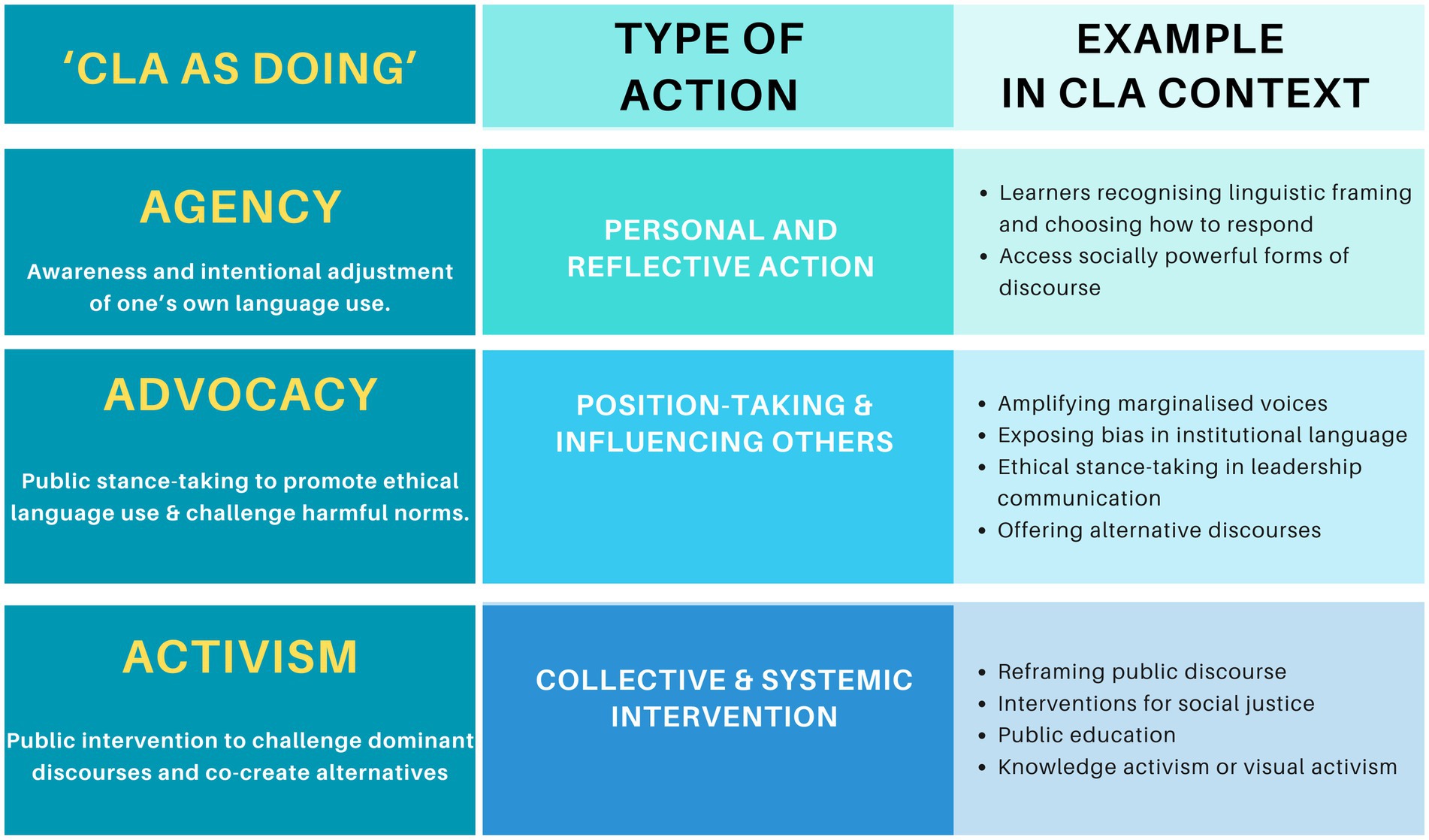

4.2 CLA as doing

4.2.1 Agency

The first step from awareness to transformation is recognising that we have the choice to take up or resist a text’s position, and that our own communicative choices matter. Recent classroom-based research supports this view: critical awareness of language works as a form of metacognition that strengthens agency, especially when learners can spot how language frames issues and then act on that insight (Gilmour et al., 2022; see also projects in the special issue of the Journal of Multilingual Theories and Practices, Zhang-Wu and Tian, 2025). Such agency involves a moral decision, for example whether to accept or reject a text’s position and framing. And this has to do, as Comber et al. (2018, p. 98), argue, “more with an ethics of care for self and others than with text analysis.” Agency, in this sense, is more than noticing power—it is about recognising one’s position and beginning to act from that awareness.

4.2.2 Advocacy

Advocacy, as distinct from the realisation of agency or systemic activism, refers to the commitment to speaking up: naming injustice, framing issues clearly, and sharing knowledge beyond academic audiences. It involves deliberate discourse practises that promote justice, equity, and sustainability—in teaching, research, curriculum design, or language work. Critical traditions such as Critical Discourse Analysis have long argued that critical scholarship should not remain descriptive but should also advocate change (Fairclough and Fairclough, 2018). This is precisely where CLA offers a way forward: by fostering not only awareness, but ethical stance-taking and readiness to intervene. Those who develop CLA gain confidence to use their voice—not from partisanship, but from a deepened sense of responsibility (see Darics, 2019; Hansson, 2024).

In some fields, such as journalism, this advocative stance has deep practical implications: it acknowledges that reporting always involves framing and positioning. This is why we can actually view all journalism as advocacy journalism (cf. Edwards, 2013; Niles, 2011)—the idea of neutrality is itself a rhetorical construction. Rather than concealing perspective, ethical practise demands its disclosure: making ideological assumptions visible, crafting storeys that resonate whilst fostering inquiry rather than obscuring perspective under a guise of objectivity (Laws and Chojnicka, 2020).

Such discourse-based empowerment can take different forms. One approach is amplifying marginalised voices: for example, the project Gender and Language in African Contexts Network uses narrative research to document women’s experiences of gender-based discrimination—raising awareness, shaping policy discourse, and supporting educational outreach (Lumala and Mullany, 2020). Another involves exposing problematic institutional language practises, such as the work by Van der Lee and Ellemers (2015), which revealed how gendered language in research funding reviews systematically disadvantaged women. Their findings led the Dutch national funding agency to implement changes, including reviewer training and a reassessment of evaluative language (Anon, 2015). Offering alternative language is a step beyond exposure: for example, Morrish and Sauntson (2019) propose new ways of talking and writing to challenge the harmful managerialist discourses circulating in higher education.

4.2.3 Activism

If agency is the realisation that change is possible and contingent on ourselves, and advocacy is the commitment to speaking up, then activism is the deliberate effort to transform discourse and reality. Activism means reimagining the world through alternative linguistic and communicative practises: it is rooted in a refusal to accept dominant framings, and a commitment to creating new ones, to crafting new stories to live by (Stibbe, 2021).

Critical literacy explicitly advocates for this kind of transformation through the concept of re-design: the process of reframing and rewriting dominant representations to mobilise change (Janks et al., 2013). An example is the #ReframeCovid initiative, which crowdsourced alternatives to war and violence metaphors during the pandemic, exposing potentially harmful framings and intervening in public discourse by promoting metaphorical reframing as a tool for collective healing, empathy, and resilience (Olza et al., 2021).

Activism can take multiple forms:

• Knowledge activism. The term, coined by Jan Blommaert, captures his rejection of academic neutrality. He worked to empower non-academic audiences through open-access publishing and direct engagement—an example is his self-published and widely debated book on anti-racism (Blommaert and Verschueren, 1994).

• Direct intervention for social justice. For example, activist applied linguistics focuses on communication-related injustices, applying methods from language studies to spotlight and address them (Avineri and Martínez, 2021; Sauntson et al., 2025). One such intervention influenced national policy: researchers developed more equitable language assessment guidelines for refugee status determinations, prompting governmental adoption (Patrick et al., 2018).

• Advice and education. Activism also includes public education efforts, such as collaborations with educators, NGOs, and communities. The Ecolinguistics Association, led by Stibbe (2021, 2023), offers freely accessible courses on reframing ecological messages for broader social and environmental impact.

• Political campaigning. George Lakoff’s work on metaphor and framing (Lakoff, 2014) exemplifies activist scholarship beyond the academy—through books, blogs, public commentary, and educational work via the now-defunct Rockridge Institute.

But activism is not exclusive to researchers. This spirit is alive in community-based discursive activism. One example is the Sea Walls mural project in Cape Town. Keep it Clean (Figure 5), painted in 2023 by Amy-Lee Tak, is located along the Sea Point promenade—a bustling, public-facing space.

Figure 5. Keep it clean by Amy-Lee Tak, Sea Walls: South Africa leaves a lasting legacy photographer: Yoshiru Yanagita, used with permission.

Murals like this foster local ownership and accountability, referencing familiar environments and species to spark reflection. The visual message is part of a broader initiative including beach clean-ups, youth outreach in local schools, and community events such as film screenings and panel discussions on art and ecological advocacy. This mural does not simply raise awareness of the oceans, but repositions the issue—from the oceans, to our oceans, to this ocean. Such local reframing invites a shift in stance: from abstract concern to situated responsibility. It helps us—like the proverbial fish—begin to notice the water that surrounds us, in every sense of the word (Figure 6).

5 The CLA imperative

This position paper has shown that the somewhat siloed landscape of language and discourse oriented research and literacy education is already rich in tools, insights, and practises that converge around the CLA agenda. But to fulfil its transformative potential, CLA must move from the margins to the centre—to classrooms of all levels and disciplines, curricula, and institutional cultures.

Of course language and communication already feature in competency frameworks—the problem is that they are typically treated as technical or instrumental skills. UNESCO’s Education for Sustainable Development Goals (UNESCO, 2017), for example, includes objectives such as questioning perceptions, or articulating a sustainable voice, yet these goals treat communication as a delivery tool, not as a reflective or agentive practise. The same blind spot persists across other key frameworks, including the Council of Europe’s Reference Framework for Competences for Democratic Culture (Council of Europe, 2016) and the Inner Development Goals (Ankrah et al., 2023). What they miss is the deeper function of language, the very medium through which systems are maintained, and through which transformation becomes possible.

What is needed now is stronger theory work. Theorisation is widely acknowledged as a gap when it comes to complex, future-oriented competencies (European Commission, 2021; Jónsson and Garces Rodriguez, 2021), and CLA is no exception. Existing theorists have already laid important foundations, however: Lier’s (1998) levels of awareness trace a progression from intuitive noticing, to discursive reflection, to critical awareness; James and Garrett (2014) highlight CLA’s multidimensional scope, from curiosity and pattern recognition to political critique and communicative performance; and Freebody and Luke’s (1990, 1999) 4 reader roles show its pedagogical value for decoding, meaning-making, participation and critical analysis. Shapiro (2022) adds a practise-oriented perspective, outlining four pathways—sociolinguistics, critical academic literacies, media/discourse analysis, and communicating across difference—that make CLA teachable and transferable across contexts.

The next step of this work is an integrated framework that brings these strands together: developmental progression, multidimensional scope, and transformative potential. Such a model is essential not only to position CLA within existing educational and policy frameworks, but also to provide a solid foundation for its operationalisation.

The operationalisation of CLA is the key point of our agenda. Without clear pathways for integration, even the most robust theory risks remaining abstract. A case in point is Critical Discourse Studies, which, despite its explicitly critical stance, has at times struggled to translate analytical insight into concrete societal change. As Serafis and Bennett (2025) note, CDS risks becoming reduced to a methodological toolkit, applied across domains but often stripped of its original transformative intent. To avoid a similar outcome, CLA must move forward with an explicit commitment to action, with a well-defined integrated agenda for how awareness can be cultivated, enacted, and scaled across educational and professional contexts.

As we have shown in section 3.1, CLA must move beyond the language classroom and become embedded across disciplines particularly those involved in shaping public discourse and professional practise. To achieve this, two priorities emerge. First, communication around CLA must become more accessible, reaching audiences outside the language and communication sciences and including the wider population—from the youngest of learners to policymakers, educators, and civil society. Research shows that people are already engaging in politically and ethically aware reflections on language (Roccia and Iubini-Hampton, 2021; Spencer-Bennett, 2021). What is missing on a larger scale is the metalanguage to articulate and legitimise these ‘lay’ reflections and to combine insights from the various strands and fields that we touched upon before (see Bateman, 2022; Wildfeuer and Lehmann, 2024). As Spencer-Bennett (2021) notes, critical language work should involve “much less in the way of challenging common sense… and much more in the way of dialogic engagement with actually existing concerns” (p. 295). Similarly, building on van Leeuwen (2005), Bateman (2022) calls for an integrationist interdisciplinarity through triangulation and the development of external or meta-languages. CLA has a key role to play in bridging that gap and finding the common understanding of and for language and communication.

For this wide-scale advocacy—perhaps even activism, as discussed in section 4.2—we need the kind of popular communication and education advocated by Freire (2021) and Blommaert (see in Rampton, 2021), alongside a closer, collaborative relationship between language-oriented research and policy-making (Ayres-Bennett, 2024).

Second, CLA and its effects need to be made visible, through forms of measurement that capture not only knowledge, but also shifts in values, attitudes, and awareness. Scholarly research has already explored how language awareness develops (for an overview see Wang and Liu, 2024), but we know far less about CLA’s broader effects, especially as a catalyst for inner transformation. Some evidence of this already exists, for example reports on the effects of the Ecolinguistics course Stories we live by5 (Roccia and Iubini-Hampton, 2021), the sociolinguistics awareness raising experiments of the RAVE project6 (Deutschmann and Steinvall, 2020) or reports from CLA education in the literacy classroom (Shapiro, 2025) show that critical awareness of language leads to meaningful change in knowledge, values and attitudes.

We are aware that efforts to measure CLA run the risk of reducing complex forms of awareness to simplified indicators. Other frameworks that seek to assess deep competencies, such as the Council of Europe’s Reference Framework for Competences (Council of Europe, 2016) and the Inner Development Goals7 face similar challenges. Still, if CLA is to be operationalised and embedded across curricula, it must work within the realities of educational systems that prioritise measurable learning outcomes. This is a delicate balancing act: whilst reductionism is indeed an inherent risk, we see it counterbalanced by the exceptional transformative potential of integrating CLA into curricula.

CLA is not a peripheral skill, but a future-oriented metacognitive competency. It trains us to see language not as neutral, but as a force that shapes—and can reshape—our shared world. It enables all of us to ask: What is language and multimodal communication doing? Whose interests does it serve? And how can I (or we as society) use it differently? To realise this potential, CLA needs to be more than an idea: it must be theorised, taught and communicated, and made operational through practise and measurement. This is therefore our call to raise awareness of CLA, to find its much needed place in new and emerging frameworks and future-facing learning agendas.

In an era of epistemic instability and discursive overload, awareness is not optional, it is foundational. As Theory U (Scharmer, 2018) reminds us, transformation begins when we pause, reflect, and become aware of the deeper structures shaping our actions. CLA makes these structures visible. It helps us see the water.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

ED: Conceptualization, Project administration, Methodology, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. OS: Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization. MD: Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JC: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology. MM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization. JO: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft. DS: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. JW: Methodology, Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the Agricola School for Sustainable Development at the University of Groningen, the Erasmus+ funding Critical Language Awareness, Democratic Engagement and Sustainability, grant number 2024-1-NL01-KA220-HED-000249129; and the Sub-Saharan Africa travel grant of the University of Groningen, which funded the research visit of Orrie Staschen (University of Cape Town).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the many colleagues whose insights and wisdom have shaped this paper, with special thanks to Shawna Shapiro and Veronika Koller for their generous reviews. We are also deeply grateful to the Rudolf Agricola School for Sustainable Development and the Sub-Saharan Africa Scheme at the University of Groningen, as well as the Erasmus+ programme for their financial support. Their backing gave us the rare chance to share space, think together, and engage in genuine co-creation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The convergence and entanglement of multiple, interconnected crises (e.g., environmental, social, political) which traverse systemic boundaries.

2. ^“Ways of being in the world” (Gee, 2012, p. 11).

3. ^https://cla.middcreate.net/

4. ^https://responsus.org/clades/

5. ^https://www.storiescourse.org/

References

Ala-Uddin, M. (2019). “Sustainable” discourse: a critical analysis of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Asia Pac. Media Educ. 29, 214–224. doi: 10.1177/1326365x19881515

Alexander, R. (2010). Framing discourse on the environment: a critical discourse approach. Abingdon: Routledge.

Alvesson, M., and Spicer, A. (2011). Metaphors we lead by: understanding leadership in the real world. London and New York: Routledge.

Ankrah, D., Bristow, J., Hires, D., and Henriksson, J. A. (2023). Inner development goals: from inner growth to outer change. Field Actions Sci. Rep. 25, 82–87. Available online at: https://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/7326

Anon. (2015). ‘Gender affects awarding of research funding’. Available online at: https://phys.org/news/2015-09-gender-affects-awarding-funding.html (Accessed May 5, 2025).

Archakis, A., and Tsakona, V. (2022). “It is necessary to try our best to learn the language”: a Greek case study of internalized racism in antiracist discourse. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 23, 161–182. doi: 10.1007/s12134-021-00831-3

Archakis, A., and Tsakona, V. (Eds.) (2024). Exploring the ambivalence of liquid racism: in between antiracist and racist discourse. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Avineri, N., and Martinez, D. C. (2021). Applied linguists cultivating relationships for justice: An aspirational call to action. Applied Linguistics. 42, 1043–1054.

Ayres-Bennett, W. (2024). Why language research matters: strengthening connections between academia and policy. London: Institute of Languages, Cultures and Societies, University of London.

Barwell, R. (2020). The flows and scales of language when doing explanations in (second language) mathematics classrooms, paper presented at Seventh ERME Topic Conference on Language in the Mathematics Classroom, Montpellier, France, February 2020.

Bateman, J. A. (2022). Multimodality, where next? – some meta-methodological considerations. Multimodality Soc 2, 41–63. doi: 10.1177/26349795211073043

Beaudrie, S., Amezcua, A., and Loza, S. (2021). Critical language awareness in the heritage language classroom: design, implementation, and evaluation of a curricular intervention. Int. Multilingual Res. J 15, 61–81. doi: 10.1080/19313152.2020.1753931

Berger, P. L., and Luckmann, T. (1991). The social construction of reality: a treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Harlow, England: Penguin Books.

Bevitori, C., and Russo, K. E. (2025). ““Because climate change is the crisis that will stay with us”: crisis, polycrisis, and permacrisis in the EU discursive space” in Critical approaches to polycrisis: discourses of conflict, migration, risk, and climate. eds. T. Parnell, T. Van Hout, and D. Del Fante (Cham: Springer), 283–308.

Blommaert, J., and Bulcaen, C. (2000). Critical discourse analysis. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 29, 447–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.29.1.447

Bristow, J., Bell, R., Wamsler, C., Björkman, T., Tickell, P., Kim, J., et al. (2024). The System Within: Addressing the Inner Dimensions of Sustainability and Systems Transformation (Earth 4 All Deep Dive Paper 17). The Club of Rome. Available online at: https://www.clubofrome.org/publication/earth4all-bristow-bell/ (Accessed May 05, 2025).

Chau, M. H., Zhu, C., Jacobs, G. M., Delante, N. L., Asmi, A., Ng, S., et al. (2022). Ecolinguistics for and beyond the sustainable development goals. J. World Lang. 8, 323–345. doi: 10.1515/jwl-2021-0027

Chi, J., and Rolstad, K. (2024). “Challenging standard language ideology and promoting critical language awareness in teacher education” in International perspectives on critical English language teacher education: theory and practice. eds. A. F. Selvi and C. Kocaman (London: Bloomsbury), 27–32.

Chmiel, M., Fatima, S., Ingold, C., Reisten, J., and Tejada, C. (2025). Climate change as fake news: positive attribute framing as a tactic against corporate reputation damage from the evaluations of sceptical, right-wing audiences. Corp. Commun. 30, 388–407. doi: 10.1108/CCIJ-12-2023-0190

Clark, J. (2016). Selves, bodies and the grammar of social worlds: reimagining social change. London: Palgrave.

Clark, R., Fairclough, N., Ivanič, R., and Martin-Jones, M. (1990). Critical language awareness part I: a critical review of three current approaches to language awareness. Lang. Educ. 4, 249–260. doi: 10.1080/09500789009541291

Clark, R., Fairclough, N., Ivanič, R., and Martin-Jones, M. (1991). Critical language awareness part II: towards critical alternatives. Lang. Educ. 5, 41–54.

Clark, R., and Ivanič, R. (1997). “Critical discourse analysis and educational change” in Encyclopedia of language and education: knowledge about language. eds. L. Lier and D. Corson (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 217–227.

Cohen, L., Musson, G., and Tietze, S. (2005). Teaching communication to business and management students: a view from the United Kingdom. Manag. Commun. Q. 19, 279–287. doi: 10.1177/0893318905278536

Comber, B., Janks, H., and Hruby, G. G. (2018). Texts, identities, and ethics: critical literacy in a post-truth world. J. Adolesc. Adult. Lit. 62:95. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26632941

Cope, B., and Kalantzis, M. (2020). Making sense: Reference, agency, and structure in a grammar of multimodal meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cope, B., and Kalantzis, M. (2022). Futures for research in education. Educ. Philos. Theory 54, 1732–1739. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2020.1824781

Council of Europe (2016). Reference framework of competences for democratic culture: living together as equals in culturally diverse democratic societies. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Cummins, J. (2018). “Foreword” in Language awareness in multilingual classrooms in Europe: from theory to practice. eds. C. Hélot, C. Frijns, K. Van Gorp, and S. Sierens (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton), V–X.

Cummins, J. (2023). Critical multilingual language awareness: the role of teachers as language activists and knowledge generators. Lang. Awareness 32, 560–573. doi: 10.1080/09658416.2023.2285361

Daniels, B., Sterzuk, A., Morin, R., Cook, W. R., Thunder, D., and Turner, P. (2025). “ē-nitomikoyahkik kakīwēyahk [they’re calling us home]”: kinship, land, and wellness in indigenous language revitalization. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 81, 214–235. doi: 10.3138/cmlr-2024-0074

Darics, E. (2019). Critical language and discourse awareness in management education. J. Manage. Educ. 43, 651–672. doi: 10.1177/1052562919848023

Darics, E. (2022). Language awareness in business and the professions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

De Costa, P. I., and Van Gorp, K. (2023). Centering critical multilingual language awareness in language teacher education: towards more evidence-based instructional practices. Lang. Awareness 32, 553–559. doi: 10.1080/09658416.2023.2285359

DeCaire, O. R. (2023). “Language and food: a world view in verbs” in Earth to table legacies. eds. D. Barndt, L. Baker, and A. Gelis (New York: Rowman & Littlefield).

Demata, M., Zorzi, V., and Zottola, A. (2022). Conspiracy theory discourses. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Deutschmann, M., and Steinvall, A. (2020). Combatting linguistic stereotyping and prejudice by evoking stereotypes. Open Linguistics 6, 651–671. doi: 10.1515/opli-2020-0036

Devitt, A. (2009). “Teaching critical genre awareness” in Genre in a changing world. eds. C. Bazerman, A. Bonini, and D. Figueriredo (Fort Collins, Colorado, USA: The WAC Clearinghouse), 337–351.

Du Bois, I. (2019). Linguistic discrimination across neighbourhoods: Turkish, US-American and German names and accents in urban apartment search. J. Lang. Discrimin. 3, 93–116. doi: 10.1558/jld.39973

Duffelmeyer, B., and Ellertson, A. (2005). Critical visual literacy: multimodal communication across the curriculum. Across Disciplines 3, 1–13. doi: 10.37514/ATD-J.2006.3.2.02

Edwards, D. (2013). All journalism is ‘advocacy journalism’. Media Lens. Global Research. Available online at: https://www.globalresearch.ca/all-journalism-is-advocacy-journalism/5345916 (Accessed April 25, 2025).

European Commission (2021). Towards a structured and consistent terminology on transversal skills and competences. Luxembourg: European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (CEDEFOP).

Everett, C., Blasi, D. E., and Roberts, S. G. (2015). Climate, vocal folds, and tonal languages: connecting the physiological and geographic dots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 1322–1327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417413112

Fafunwa, A. B., Macauley, J. I., and Sokoya, J. A. F. (1989). Education in mother tongue: the Ife primary education research project. Ibadan: University Press Ibadan.

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis: the critical study of language. London: Routledge.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: textual analysis for social research. London: Routledge.

Fairclough, N., and Fairclough, I. (2018). A procedural approach to ethical critique in CDA. Crit. Discourse Stud. 15, 169–185. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2018.1427121

Fenton, D. (2022) ‘Climate change: a communications failure’, The Hill. Available online at: https://thehill.com/opinion/energy-environment/3709795-climate-change-a-communications-failure/ (Accessed May 05, 2025).

Flowerdew, J., and Richardson, J. E. (Eds.) (2018). The Routledge handbook of critical discourse studies. London: Routledge.

Freebody, P., and Luke, A. (1990). Literacies programs: debates and demands in cultural context. Prospect. 5, 7–16.

Freebody, P., and Luke, A. (1999). ‘Further notes on the four resources model’, Reading Online, International Reading Association. Available online at: www.readingonline.org (Accessed May 05, 2025).

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th anniversary edition). London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Galasiński, D., and Ziółkowska, J. (2022). “Language guides: an exercise in futility” in Language awareness in business and the professions. ed. E. Darics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 83–100.

Garrett, P., and Cots, J. M. (Eds.) (2018). The Routledge handbook of language awareness. London: Routledge.

Gee, J. P. (2012). Social linguistics and literacies: ideology in discourses. 4th Edn. London: Routledge.

Gillings, M., and Dayrell, C. (2024). Climate change in the UK press: examining discourse fluctuation over time. Appl. Linguist. 45, 111–133. doi: 10.1093/applin/amad007

Gilmour, G., Batty, E., Holmes, W., Whalley, S., and Inugai-Dixon, C. (2022). The role of the international baccalaureate middle years Programme interdisciplinary unit as a cohesive, collaborative and synergistic practice to increase student language awareness for agency: an action research report from Hiroshima global academy. J. Res. IB Educ. 6, 115–124. doi: 10.50923/ibjournal.6.0_115

Grinberg, N., Joseph, K., Friedland, L., Swire-Thompson, B., and Lazer, D. (2019). Fake news on twitter during the 2016 US presidential election. Science 363, 374–378. doi: 10.1126/science.aau2706

Guess, A., Nagler, J., and Tucker, J. (2019). Less than you think: prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Sci. Adv. 5:eaau4586. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aau4586

Halliday, M. A. K., and Matthiessen, C. M. (2013). Halliday's introduction to functional grammar. London and New York: Routledge.

Handford, M., Garrett, P., and Cots, J. M. (2019). Introduction to language awareness in professional communication contexts. Lang. Awareness 28, 163–165. doi: 10.1080/09658416.2019.1654647

Hansson, S. (2024). “Blame avoidance and critical language awareness: an approach from critical discourse studies” in The politics and governance of blame. eds. M. Flinders, G. Dimova, M. Hinterleitner, R. A. W. Rhodes, and K. Weaver (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 159–181.

Harari, Y. N. (2024). Nexus: a brief history of information networks from the stone age to AI. New York: Random House.

Harding, L., DeCaire, R., Ellis, U., Delaurier-Lyle, K., Schillo, J., and Turin, M. (2025). Language improves health and wellbeing in indigenous communities: a scoping review. Lang. Health 3:47. doi: 10.1016/j.laheal.2025.100047

Heller, M., Pietikäinen, S., and Pujolar, J. (Eds.) (2018). Critical sociolinguistic research methods: Studying language issues that matter. New York: Routledge.

Hélot, C. (2003). Language policy and the ideology of bilingual education in France. Lang. Policy 2, 255–277. doi: 10.1023/A:1027316632721

James, C., and Garrett, P. (2014). “The scope of language awareness” in Language awareness in the classroom. eds. C. James, P. Garrett, and C. N. Candlin (London: Routledge), 3–20.

Janks, H. (1997). “Teaching language and power” in Encyclopedia of language and education: language policy and political issues in education. eds. R. Wodak and D. Corson (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 241–251.

Janks, H., Dixon, K., Ferreira, A., Granville, S., and Newfield, D. (2013). Doing critical literacy: texts and activities for students and teachers. 1st Edn. New York: Routledge.

Jónsson, Ó. P., and Garces Rodriguez, A. (2021). Educating democracy: competences for a democratic culture. Educ. Citizensh. Soc. Justice 16, 62–77. doi: 10.1177/1746197919886873

Jørgensen, J. N. (2008). Polylingual languaging around and among children and adolescents. Int. J. Multiling. 5, 161–176. doi: 10.1080/14790710802387562

Jørgensen, M. W., and Phillips, L. J. (2002). Discourse analysis as theory and method. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Kalantzis, M., and Cope, B. (2025). Multiliteracies since social media and artificial intelligence. Harv. Educ. Rev. 95, 135–151. doi: 10.17763/1943-5045-95.1.135

Kimmerer, R. W. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge, and the teachings of plants. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions.

Klumpp, J. F., and Hollihan, T. A. (1989). Rhetorical criticism as moral action. Q. J. Speech 75, 84–96. doi: 10.1080/00335638909383863

Koller, V. (2018). Language awareness and language workers. Lang. Aware. 27, 4–20. doi: 10.1080/09658416.2017.1406491

Kopnina, H. (2020). Education for the future? Critical evaluation of education for sustainable development goals. J. Environ. Educ. 51, 280–291. doi: 10.1080/00958964.2019.1710444

Kress, G., Ogborn, J., and Martins, I. (1998). A satellite view of language: some lessons from science classrooms. Lang. Aware. 7, 69–89. doi: 10.1080/09658419808667102

Kress, G., and van Leeuwen, T. (2020). Reading images: the grammar of visual design. 3rd Edn. London: Routledge.

Krzyżanowski, M., and Forchtner, B. (2016). Theories and concepts in critical discourse studies: facing challenges, moving beyond foundations. Discourse Soc. 27, 253–261. doi: 10.1177/0957926516630900

Krzyżanowski, M., Wodak, R., Bradby, H., Gardell, M., Kallis, A., Krzyżanowska, N., et al. (2023). Discourses and practices of the ‘new Normal’ towards an interdisciplinary research agenda on crisis and the normalization of anti-and post-democratic action. J. Lang. Polit. 22, 415–437. doi: 10.1075/jlp.23024.krz