- Faculty of Communication, University of Bhayangkara Jakarta Raya, Jakarta, Indonesia

The courtroom in Indonesia functions not only as a formal legal setting but also as a socio-communicative arena where judges, prosecutors, defense lawyers, witnesses, and defendants interact under strict procedural and cultural norms, shaping justice, transparency, and public trust. This study employed a qualitative case study approach to analyze courtroom communication in Indonesian criminal trials, with data collected through interviews with nine informants (judges, prosecutors, defense lawyers, a witness, and a defendant), observations of three trials at the Bekasi District Court, and document analysis. Using thematic analysis involving coding, categorization, interpretation, and conclusion, the study identified two dominant communication flows: one-way communication, such as judicial instructions and verdict delivery, and multi-directional communication, such as examinations and cross-examinations. Furthermore, six communication characteristics were found: professional, hierarchical, confrontational, investigative, adversarial, and supportive, illustrated by examples such as judges’ clarifying questions, prosecutorial challenges, and empathetic accommodations for vulnerable witnesses. Theoretically, the study advances socio-legal communication research by integrating dimensions of authority, contestation, and fairness in courtroom interaction, while practically, it provides insights for legal practitioners to strengthen communication strategies that enhance effectiveness, fairness, and legitimacy in judicial processes, thereby reinforcing public trust in Indonesia’s justice system.

1 Introduction

The courtroom is the formal arena for adjudication. It is a designated space in which legal proceedings are examined by all parties to the judicial process, and where interaction occurs in an orderly and structured environment. Parties involved in legal cases include judges, prosecutors, lawyers, witnesses, and defendants who interact to achieve justice for both defendants and victims (Aronsson et al., 1987; Grossman, 2019; Walenta, 2020; Widodo, 2019).

Courtrooms comprise interrelated elements of physical layout, institutional norms, and communicative practices (Bandes and Feigenson, 2020; LeVan, 1984; Rossner et al., 2021). The physical layout refers to the trial facilities, among others, the judge’s bench, prosecutor’s desk, lawyer’s desk, witness bench, and seating for the defendant as well as the audience or visitors to the trial (Hawilo et al., 2022). Meanwhile, norms and values are elements that support the principle of conducting open, transparent and fair trials, including the provisions and communication processes carried out in achieving the objectives of the trial. Every element in the courtroom, from the physical layout to the various rules including the rules of communication, aims to support a fair and impartial judicial process (Gordon and Druckman, 2018). In this environment, communication plays an important role, in determining the outcome of the judicial process (Otu, 2015; Turner and Hughes, 2022). Through communication, trial actors share information, in order to achieve the intended goals (Widodo, 2022; Widodo et al., 2018).

The form of communication that occurs in the courtroom is part of what is known as Courtroom Communication (Cowles and Cowles, 2011; Farley et al., 2014a; Hans and Sweigart, 1993). McCaul (2016) define courtroom communication as a concept that includes communication events or specific aspects of interactions that take place in the law enforcement process. Various terms are used to describe the dynamics of communication in a trial, depending on the role, participation, and form of interaction between participants. Howes (2015) use the term forensic communication to emphasize the content and substance of the message conveyed. Roach Anleu and Mack (2015) prefers the term judicial communication which highlights the legal dimension of communication that occurs during the trial (Leung, 2012). Philips (1985) uses the term trial communication which refers to communication based on stages or processes in the trial (Philp, 2022). Although scholars using different terms (courtroom communication, judicial communication, forensic communication, and trial communication), they all refer to the context of communication in the courtroom involving actors, messages with legal purposes, and structured interactions.

Communication in the courtroom has a very important role in determining justice for both defendants and victims in the Indonesian justice system (Donoghue, 2017). In the courtroom, interactions between various legal actors such as judges, prosecutors, lawyers, defendants, witnesses, and other related parties have an influence on the process of formation and decision-making, including through perception, dramaturgy, and nonverbal communication(Aceron, 2015; Elbers et al., 2012; Suffet, 1966; Wodak, 1980). The dynamic of Communication that occurs in the trial affect way the evidence, the arguments submitted, and the conclusions drawn by the judge and accepted by the legal actors. In general. Widodo (2019) describes this communication through the law enforcement communication model, the examination communication model, and the communication model between law enforcement and defendant or witnesses in court (Widodo, 2024a, 2024b; Widodo, 2020; Widodo, 2019).

Existing studies on courtroom communication can be grouped thematically into several streams. Research on verbal communication has shown how arguments are framed, how examinations are structured, and how advocates adapt their language to audiences such as judges and jurors (Farley et al., 2014b; Hans and Sweigart, 1993). Other studies have emphasized nonverbal and multimodal aspects, demonstrating the importance of gaze, posture, and vocal delivery as well as the influence of documents, recordings, and screen-based exhibits in shaping courtroom interaction (Gordon and Druckman, 2018; LeVan, 1984; Otu, 2015) Scholars have also examined interactional patterns among legal actors, highlighting how judges regulate presence, participation, and turn allocation, including in virtual or hybrid courts (Donoghue, 2017; Rossner and Tait, 2023). In addition, socio-legal research has linked courtroom communication to broader outcomes of procedural justice and legitimacy, showing that clarity of expression, equal opportunities to speak, and respectful treatment of participants are crucial in building public trust in the judicial process (Bandes and Feigenson, 2020; Walenta, 2020).

At the Bekasi Regional District Court, communication in the courtroom occurred in the law enforcement process. Based on the results of the researcher’s observations, law enforcers interact and communicate in the courtroom, not only between law enforcement officials and witnesses and defendants, but also with court officers. Communication between the parties is one of the keys to the implementation of the trial and the success of the law enforcement process in the courtroom. Communication depends on the special characteristics of the conference. The Bekasi city district court trial is one of the courts that carries out communication in the trial as an interaction process that occurs in a trial process with different characteristics.

This research focuses on the characteristics of communication in court trials. This research is important to be carried out in order to understand the communication process in criminal trials. Communication is done by ensuring that each party involved in the judicial process has an equal opportunity to present their arguments and evidence. In addition, effective communication can also help in creating an environment conducive to creating public trust in the justice system. In a broader context, this research can also contribute to the development of more effective communication methods and strategies in criminal justice. With an understanding of how communication affects the judicial process, relevant parties, including judges, prosecutors, lawyers, and legal counsel, can develop a better communication approach to achieving desired legal goals.

To address this, the present study employs an explicit theoretical framework that integrates three complementary perspectives. First, Goffman’s concept of gatherings (1963) views the courtroom as a socially organized event in which roles, authority, and norms are performed and negotiated. This perspective highlights the professional and hierarchical dimensions of courtroom communication, where authority is enacted symbolically through verbal and nonverbal practices. Second, the framework of judicial communication (Roach Anleu and Mack, 2015), emphasizes how judges display authority, neutrality, and legitimacy through both verbal and nonverbal interactions. This perspective is particularly relevant in Indonesia, where judges actively direct proceedings, regulate turn-taking, and ensure fairness while at times providing supportive communication for vulnerable participants such as witnesses or defendants. Third, Howes (2015) concept of forensic communication, further elaborated by Howes (2015), Matoesian (2017), and Maynard et al. (2014) underscores the adversarial and investigative nature of courtroom exchanges, especially in the presentation and testing of evidence through questioning and cross-examination (Howes, 2015; Matoesian, 2017; Maynard et al., 2014). By integrating these three perspectives, the study provides a robust conceptual foundation to interpret courtroom communication not merely as procedural conduct, but as a communicative practice that shapes justice through authority, negotiation, and contestation.

Despite these contributions, several important aspects remain underexplored in the literature. Studies have rarely examined how nonverbal features such as gaze or gesture intersect with verbal strategies in determining courtroom dynamics. Similarly, the multimodal interaction between spoken exchanges, written documents, and technological media is seldom analyzed in depth, leaving a gap in understanding how these layers shape meaning and authority in trials. Furthermore, although power relations are widely acknowledged, the specific ways in which hierarchical structures and role asymmetries influence communication practices in Indonesian criminal courts are not yet sufficiently documented. Cultural influences, including local norms of respect, deference, and emotional restraint, have also received limited scholarly attention, despite their clear relevance to courtroom practice. By addressing these gaps, this study seeks to provide a more comprehensive account of the communicative characteristics of Indonesian criminal trials.

Building on these gaps, the present study is guided by two central research questions: What are the main characteristics of communication in Indonesian criminal court trials? and How do these characteristics influence the flow and outcomes of courtroom interaction? These questions direct the analysis toward identifying the distinctive features of courtroom communication and clarifying their implications for both justice and legitimacy in the Indonesian legal system. Mapping courtroom communication is essential, as every verbal and nonverbal interaction among legal actors (judges, prosecutors, lawyers, defendants, and witnesses) shapes the presentation of evidence, the arguments advanced, and ultimately the judicial decision.

2 Research methods

2.1 Research design

The research approach used is qualitative research. The researcher employs a qualitative case study approach to understand the communication between various parties in a criminal trial at the district court. The researcher conducted interviews with 9 informants and observations at 3 trials in the district court. Research informants are determined based on criteria that meet the needs of the research. In determining informants, the researcher began by determining the law enforcement informants consisting of 3 judges, prosecutors, legal advisors, 1 defendant, 1 witness, 1 visitor, 1 court officer (clerk), 1 security/prisoner.

The researcher selected informants using purposive sampling based on the research objectives, particularly for law enforcement officers (prosecutors, lawyers, and judges). Other informants were chosen incidentally during direct observation, and their eligibility was confirmed according to the data requirements. Some informants agreed to participate, while others required prior consent, such as witnesses and defendants, who needed approval from their legal counsel before being interviewed.

2.2 Data collection

Data collection combined multiple techniques to ensure triangulation:

1. In-depth interviews were conducted with nine informants to capture their perspectives, experiences, and strategies in courtroom communication.

2. Trial observations were carried out in three criminal trials at the Bekasi District Court. Observations included both participatory presence inside the courtroom and non-participatory observations from designated areas that did not interfere with proceedings.

3. Document analysis involved reviewing court transcripts, trial rulings, and audio/video recordings relevant to the observed cases.

2.3 Data analysis

After the data is collected, the data processing and analysis stage is carried out. Interview and observation data were transcribed into text. The data is then coded and categorized based on the theme or topic that appears. The analysis was carried out using content analysis for qualitative data. The analysis was carried out using thematic analysis with stages of coding, categorization, interpretation, and conclusion. Conclusions are made from the results of the analysis that are relevant to the research objectives. The coding and categorization process generated six core themes (professional, confrontational, investigative, adversarial, hierarchical, and supportive) which structured the presentation of results in this study.

2.4 Research procedure

2.4.1 Preparation and research permits

The research began with the preparation of a detailed proposal outlining the background, objectives, methods, and data collection plan. Following institutional requirements, the researcher obtained a formal research permit supported by a cover letter from the affiliated university. The proposal and official request letter were submitted to the Bekasi District Court, after which approval was granted. Coordination with court administrators ensured that interviews and observations did not interfere with trial proceedings.

2.4.2 Fieldwork and data collection steps

After obtaining permission, the researcher conducted fieldwork by observing trial proceedings, conducting interviews with selected informants, and collecting relevant documents. Fieldwork was conducted in phases to match the court’s trial schedule and to secure participants’ availability and consent.

2.5 Data validity

The trustworthiness of the research data was ensured using member checking. Member checking is the process by which data or analysis results are returned to participants to ensure that the researcher has understood and represented their views correctly. In the context of this study, after interviews or observations were conducted, the researcher returned to the judge, prosecutor, lawyer, and defendant to confirm that the results recorded were in accordance with their intended results.

3 Results

3.1 Trial process background

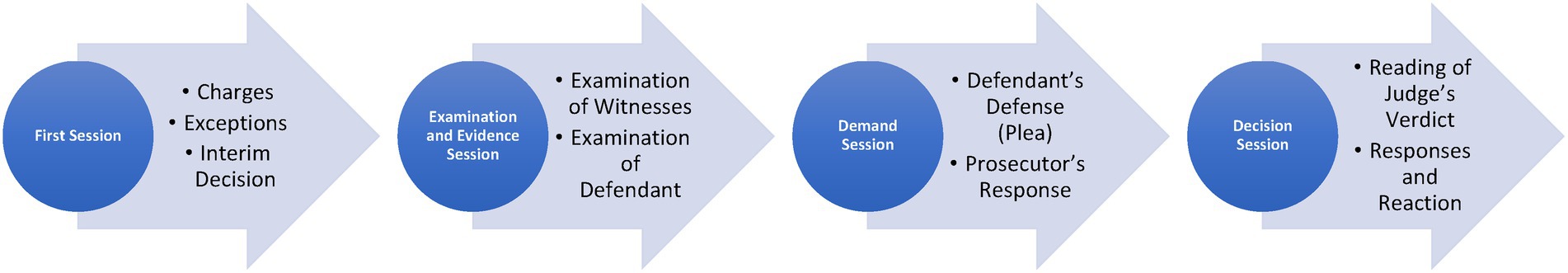

The trial and trial process are a series of trial stages in accordance with the provisions of the Criminal Code in Indonesia. In simple terms, the trial stages consist of the first hearing/indictment hearing, examination hearing, prosecution hearing and verdict hearing. Furthermore, in each of these processes, there can be a trial with a recurring agenda, for example, the examination of witnesses can be carried out many times until the truth is found. The stages are reported here situate where and how communication flows are producted during proceedings (one-way vs. multi-directional).

The criminal trial process is marked by the decision of the panel of judges regarding the first hearing. The first hearing was an indictment hearing, there was a reading of the indictment by the public prosecutor and a response to the indictment read. The second is the examination of witnesses and the examination of the defendant and the responses of each party, the third is the demand by the public prosecutor and the response, as well as the verdict by the Chief Judge and other panels that examine the case through trial. Here are some of the processes that the author refers to are classified in the following Figure 1.

The Figure 1 above illustrates the stages of the criminal trial process in court which consists of four main stages, namely the First Hearing, the Examination and Evidentiary Hearing, the Prosecution Hearing, and the Verdict Hearing

3.1.1 First session

This stage is the beginning of the trial process where the public prosecutor reads out an indictment containing the accusations against the defendant. At this stage, the defendant or his legal counsel can file an exception, which is an objection to the indictment filed, both formally and materially. If there is an exception, the judge will consider it and issue an interlocutory judgment. If the interlocutory ruling states that the indictment is valid and can be continued, then the trial will proceed to the next stage. On the other hand, if the judge accepts an exception, then the case can be stopped or the prosecutor needs to redraft the indictment. Observation Note (Trial 1): Prior to the indictment reading, the presiding judge stated, “We proceed according to the agenda: indictment, then defense response,” establishing a one-way instructional frame.

3.1.2 Examination and evidence hearing

This stage is the core of the trial process, where evidence is submitted and tested before a panel of judges. This process begins with the examination of witnesses, both submitted by the public prosecutor and by the defendant (if there are mitigating witnesses). Witnesses give their testimony under oath and can be questioned by judges, prosecutors, and legal counsel of the defendant. After the examination of witnesses is completed, the trial continues with the examination of the defendant, where the defendant is given the opportunity to explain or respond to the facts that arise in the trial. At this stage, other evidence such as letters, recordings, or other evidence that supports the evidentiary process can also be submitted. Observation Note (Trial 2): During cross-examination, the defense interrupted the prosecutor; the judge intervened, “Counsel, one question at a time,” which reopened orderly turn-taking. This alternation from one-way instruction to multi-directional exchange exemplifies Goffman’s gatherings (ordered roles/rituals) and Judicial Communication (authority through turn allocation), while adversarial exchanges operationalize Forensic Communication (testing evidence).

3.1.3 Trial of claims

After the evidentiary process is completed, the public prosecutor will submit criminal charges against the defendant, which is referred to as a requisitoir. These charges include a legal analysis of the facts revealed at the trial as well as the sentencing recommendations submitted by the prosecutor. After that, the defendant or his legal counsel is given the opportunity to submit a plea (defense), which can be in the form of a rebuttal to the prosecutor’s indictments and demands, a request for leniency, or any other defense deemed relevant. After the defense is submitted, the prosecutor is given the right to provide a replica, which is a response to the defendant’s defense. Then, the defendant or his legal advisor can again provide a duplicate, which is a response to the prosecutor’s replica. Prosecutor B explain “We structure the demand to walk the court through the facts; the defense will test our inferences point by point.” This sequenced claim-rebuttal-replica-duplika is a textbook instance of Forensic Communication (claim testing in adversarial settings).

3.1.4 Verdict hearing

This stage is the culmination of the entire series of trials, where the judge reads out the court decision based on the results of the examination and legal considerations carried out. This verdict can be in the form of a free verdict, free from all lawsuits, or a conviction with certain penalties in accordance with applicable regulations. After the verdict is read, the prosecutor and the defendant have the right to express their stance on the verdict. If either party does not accept the verdict, they can file legal remedies such as an appeal to the high court or cassation to the Supreme Court. However, if both parties accept the verdict, then the case is considered complete and the verdict becomes permanent legal force (inkracht). Observation note (Trial 3): The verdict reading proceeded without interruption; responses (accept/appeal) were recorded afterward—typical one-way communication during verdict delivery. Verdict readings enact Judicial Communication of authority and neutrality; the ritualized format reflects Goffman’s gatherings.

Every hearing, the trial process always involves the communication process of the parties involved in the courtroom. The implementation of the trial was carried out in accordance with the trial agenda set by the judge through the clerk. Initially, the Presiding Judge and the panel determined the trial schedule, which began with the determination of the indictment hearing. Furthermore, the trial schedule is carried out according to the decision of the Panel of Judges that has been agreed upon by the Public Prosecutor and Legal Counsel. The Registrar’s informant revealed that usually, the next hearing schedule is one week at most after the previous hearing. “The schedule of the trial depends, is determined and agreed upon by His Holiness.”

The trial at the Bekasi District Court will run if attended by all parties, namely the Panel of Judges including the Registrar, Public Prosecutor, Legal Counsel, and Defendants. The first party to enter the courtroom is the Defendant or the Public Prosecutor, followed by the clerk who coordinates to start the trial. After the trial was ready, the clerk allowed the Panel of Judges to enter the courtroom and occupy the prepared sitting position.

The officer will announce, “Your Majesty enters the room, the audience is requested to stand” or “The Panel of Judges enters the courtroom, the audience is requested to stand.” The Panel of Judges then entered the room with several files, usually in the form of a personal memorandum. After the Panel of Judges was seated in their seats, the officer invited the audience consisting of the Public Prosecutor, Legal Counsel, and visitors to sit, and the judge opened the trial by saying, “Audiences are welcome to sit.” These rituals display ordered deference and role separation consistent with Goffman’s gatherings and the performance of judicial authority.

Respecting the Panel of Judges by standing when they enter the courtroom is a mandatory thing to do, as stated in the Criminal Procedure Code (Criminal Procedure Code). According to Informant 4, this was done as a form of respect for the Court, the law, and the judges. However, based on the researchers’ observations, this respect was only done in the main courtroom. In smaller courtrooms, this is often not done, especially when there is no officer to guide you. Witness E explain “in the smaller room no one prompted us stand; it felt les formal.”

After the Panel of Judges sat and the parties were present in the courtroom, the presiding judge opened the trial with expressions and hammer beats. The presiding judge then mentioned the trial agenda and started the process according to the agreed agenda, whether it was an examination hearing, an indictment hearing or a verdict hearing.

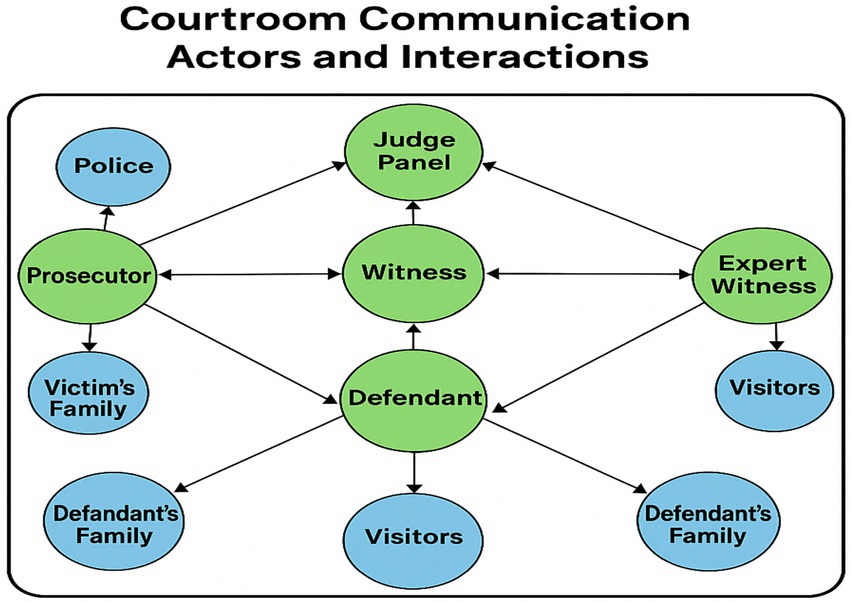

Specifically, the trial in the courtroom involves a variety of participants as support for the trial in the courtroom, based on the observation of the participant involving the main participant and the supporting insertion. The main participants refer to the trial implementation group, namely judges, prosecutors, lawyers, defendants and witnesses, while supporting participants involved in the trial process include the visiting parties, court officers who are envious of the cobrban family and the defendant’s family. Supporting participants included court officers, security/prison officers, and visitors/family members who sometimes affected the communicative environment (e.g., noise, timing).

3.2 Communication flow the courtroom

Each stage of the trial has a distinctive communication potential that involves law enforcement as the main actor in communication. Communication in the courtroom describes communication between various parties in the trial and trial process, communication takes place between the Panel of Judges, the Public Prosecutor, Legal Counsel, the Defendant, Witnesses, Registrars, and Visitors. The Panel of Judges plays a central role by officially opening the trial and leading the trial. The Presiding Judge, assisted by the Member Judge, hears arguments, evidence, and testimony from the Public Prosecutor and Legal Counsel. The Public Prosecutor is in charge of submitting the indictment and presenting evidence and witnesses that support the indictment. On the other hand, Legal Counsel, presented the defense and submitted evidence and witnesses to support the defendant. The defendant himself can give statements and answer questions from the Panel of Judges and the Public Prosecutor as well as Legal Counsel, while witnesses give testimony and answer questions from law enforcers. Witnesses play an important role by providing testimony that can support or weaken the arguments of both sides. Court officers, although their role is more administrative, also play a role in ensuring smooth communication between all parties during the trial process. Overall, successful communication in the courtroom relies heavily on clarity, accuracy, and interaction between all parties involved. Role performance, ritual entry, and turn allocation instantiate Goffman’s gatherings (ordered interaction) and Judicial Communication (authority and neutrality).

At the Bekasi District Court, communication in the courtroom involves similar dynamics to the judicial system in other countries, but there are some distinctive differences and nuances. Judges in the Indonesian District Court have a very active role in directing the trial process, including asking direct questions to defendants and witnesses. Judges here often have to double down on the role of law enforcer and communication/dialog facilitator, ensuring that all parties have a fair opportunity to present their arguments. Observation Note Trial, During the indictment hearing, the presiding judge instructed the prosecutor to “read slowly and clearly so that the defendant can understand.” The defendant listened silently and nodded occasionally without any immediate feedback, illustrating a one-way communication flow. According to Informant A, Judge., a judge explained, “As a judge, I have to make sure that all parties get a fair opportunity to speak. The questions I ask should help clarify the facts without showing partiality. Clear and firm communication is essential to maintain the integrity of the trial process”. This reflects Judicial Communication as performative neutrality and clarity; the judge’s interventions also preserve the ordered “gathering” (Goffman).

Meanwhile, Informant B, the Public Prosecutor (JPU), is tasked with representing the state in prosecuting the defendant, and they must present evidence and witnesses who can support the charges. In many cases, the prosecutor’s communication with witnesses and experts is the key to corroborating the cases they file. Observation note trial, During cross-examination of a witness in a narcotics case, the prosecutor asked, “Did you see the defendant at the scene?” The witness hesitated, and the defense counsel immediately interjected: “Objection, the question is leading.” The judge sustained the objection and instructed the prosecutor to rephrase. This exchange demonstrates a multi-directional communication flow involving judge, prosecutor, defense, and witness.

The Prosecutor’s informant, explained, “As a prosecutor, my main task is to present strong evidence and arguments. Communication with witnesses and experts is very important, as their testimony can strengthen or weaken our case. I have to be able to present my arguments in a way that can be understood by all parties, including the judge and the defendant.” Informant C, as the defense lawyer, explained that he often had to work hard to overcome the evidence set by the JPU. Defendant and Attorney used various communication strategies to challenge the evidence presented, question the validity of the testimony, and defend the rights of the defendant. Informan C, a defense lawyer in the Bekasi trial, stated, “My role is to ensure that my client’s rights are protected. This includes presenting arguments clearly and effectively and challenging the evidence presented by the prosecutor. Good communication with the defendant is also very important to ensure that the defense strategy can run well.” At the verdict hearing, the presiding judge read the decision in full without interruption. The atmosphere was silent; the defense and prosecutor only responded after the reading was completed by declaring whether they accepted or appealed. This clearly illustrates a one-way communication flow, where information is delivered without immediate feedback.

Defendants, especially in cases that attract public attention, are often under immense pressure. Their communication, whether directly in the form of statements in court or through their lawyers, can have an impact on the perception of judges and the general public. One defendant who did not want to be named said, “It was very nerve-wracking to be in the courtroom. I had to make sure that my story was heard and understood by the judges. My lawyer helped me make my arguments clearly and supported me throughout the process.” Witnesses, including expert witnesses, give testimony that can be highly technical and require further clarification through questions from judges or lawyers. Informant E, a witness in a narcotics criminal case, said, “Giving testimony in court is a stressful experience. I have to make sure that what I say is true and clear. Judges and lawyers often ask questions that help me explain in more detail.” In another instance, the judge rephrased a complex legal term into simpler language so that the witness could respond accurately. This indicates a supportive communication practice embedded in the flow.

Court officers, too, play an important role in supporting effective communication, managing the administration of the trial, and ensuring all documents and evidence are available in a timely manner. Informant G, said, “His role is to ensure that all documents and evidence are ready on time and the trial runs smoothly. We also have to communicate frequently with various parties to coordinate schedules and needs during the trial, so that it is orderly”. Likewise, the prison guards and security officers ensure that the trial runs safely and orderly.

Overall, communication in the Indonesian District Court courtroom is a complex process that requires the active involvement of all parties to ensure that the objectives of the trial are achieved and justice can be upheld. This communication is influenced by the skills of legal professionals in presenting their arguments clearly and persuasively, as well as by the judge’s ability to manage the trial process wisely and impartially. Communication in the trial through a series of participation of the parties to support the main objectives of the trial. Based on observations and information from informants, the researcher emphasized the connection of communication between the parties in supporting the communication process in the courtroom. As illustrated in Figure 2. The interplay of one-way (authority-performing) and multi-directional (adversarial testing) flows shows how hierarchy and contestation are balanced—central to perceived fairness (Judicial/Forensic Communication within Goffman’s ordered event).

Communication in court involves many factors that affect how information is conveyed, received, and interpreted in legal proceedings. In courtroom communication, each element of communication plays an important role in shaping the dynamics of interaction in the courtroom. Communicators in the trial consist of various parties who have specific legal roles, such as the judge who gives instructions, the prosecutor who reads the indictment, the lawyer who submits the defense, and the witness who gives testimony. The communicator, as the recipient of the message, includes the defendant who receives the indictment, the judge who assesses the arguments of both sides, and the witness who responds to questions asked by the prosecutor or lawyer.

The message communicated in the trial can be statements, instructions, questions, or evidence presented during the judicial process. The communication channels used are generally verbal, such as delivering arguments or interrogations, as well as nonverbal, such as legal documents, evidence recordings, or the judge’s facial expressions in giving signals. In courtroom communication, feedback occurs when the recipient of the message responds to the information received, for example when the defendant answers questions from the judge or the witness provides clarification on the prosecutor’s statement.

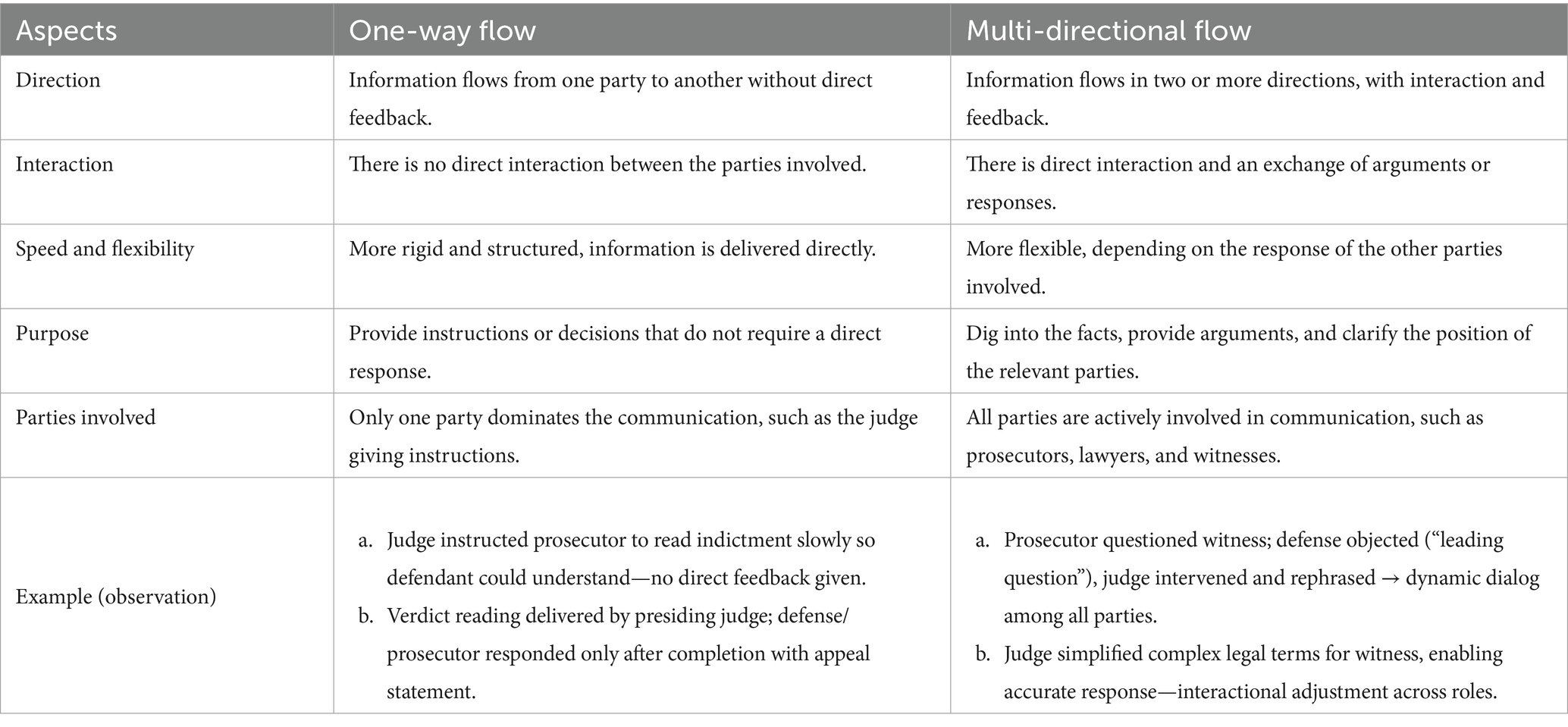

The context in courtroom communication includes legal, social, and psychological factors that affect the course of communication. The legal context includes the judicial rules that must be followed, while the social context can be in the form of public expectations of trial transparency. On the other hand, psychological distress can affect the effectiveness of communication, for example when a witness feels intimidated while giving testimony. In addition, communication disorders (noise) can also appear in various forms, such as physical disorders (noise from court visitors), psychological disorders (witness anxiety that hinders fluent speech), and semantic disorders (the use of legal terms that are difficult for witnesses or defendants to understand). The communication process is through at least two communication streams, namely one-way and multi-directional communication streams,

In real practice in the courtroom, a one-way flow usually occurs when the judge gives instructions or leads the course of the trial. For example, when the trial begins, the judge will instruct the prosecutor and lawyers about the order of the proceedings, such as who first presents arguments or when witnesses are called. Judges also often make final decisions, such as interlocutory rulings or decisions related to the evidence received. These decisions were delivered without any direct feedback from the parties involved at the time, although they could appeal or protest through other legal channels. For example, when a judge decides to accept or reject evidence, this decision is presented to lawyers and prosecutors, who can then accept the decision or make other appeals, but no direct interaction occurs at the time of the reading of the decision.

Multi-directional flow is more reflective of the active dynamics that occur during the trial process. One obvious example is during the interrogation of witnesses, where prosecutors and lawyers take turns asking each other questions and giving arguments. In this process, the witness gives an answer, which can then be further questioned or refuted by another lawyer or prosecutor. Communication here flows back and forth, with each party responding to what the other party says. Another example is when the defendant gives a statement or a lawyer defends his client. The lawyer will provide convincing arguments to the judge or jury, while the prosecutor will also present a rebuttal or clarification. During this process, there is a dynamic exchange of information, either through direct dialog or through reactions to the arguments put forward. One of the real forms of this multi-directional communication flow is seen when the judge decides to give the lawyer the opportunity to ask questions of the witness, which then becomes a question and answer process that requires the judge, prosecutor, lawyer, and witness to interact with each other. In this context, the flow of communication can be very flexible, depending on who is providing the information and how the other party responds to the information.

In the courtroom, there are two forms of communication flows that dominate the judicial process, namely the one-way flow and the multi-directional flow, each of which has an important role in the course of the trial. One-way flow occurs when information flows from one party to another without any immediate feedback at the time. An example is when the judge gives instructions or decisions, such as reading the verdict or directing the course of the trial. In this stream, other parties, such as prosecutors or lawyers, simply receive information without being able to provide an immediate response at that time. In contrast, a multi-directional flow occurs when several parties engage in interactive communication, such as in the question and answer process between prosecutors, lawyers, witnesses, and defendants. In interrogation, each party gives a response that affects the course of the conversation, creating a dynamic dialog and interacting with each other. Although these two streams differ in terms of interaction and communication structure, they have the same goal, which is to ensure that the trial process runs fairly and transparently. The one-way flow serves to provide clear and firm instructions, while the multi-way flow deepens the understanding of the facts revealed during the trial. Both are important in supporting the achievement of legitimate and fair legal decisions. The following Table 1 is meant.

In the context of communication in the courtroom, the flow of communication refers to the direction and pattern of interaction that occurs between various participants during the law enforcement process. These streams of communication can be categorized into two main types:

3.2.1 One-way communication flow

Occurs when information or messages are conveyed from one party to another without any immediate response. An example is when the judge reads the verdict or the prosecutor submits an indictment. In this situation, communication is linear and does not require immediate feedback from the recipient of the message.

One-way communication occurs when information is delivered from one actor to others without immediate feedback. This flow typically appears during formal openings, the delivery of instructions, interlocutory rulings, and the reading of verdicts. In these moments, judges speak with institutional authority, and other parties listen in silence.

Observation, Trial 1, Before the indictment was read, the presiding judge announced, “We proceed according to the agenda: indictment, then defense response.” The statement framed the trial in a top-down manner, establishing authority and structure. The defendant and legal counsel listened quietly without comment, illustrating linear communication. Observation, Trial 3, The verdict was read in its entirety without interruption. The courtroom atmosphere was silent, and only after the reading did the prosecutor and defense state whether they would accept or appeal. This ritualized silence underscored the symbolic authority of the bench. Informant A (Judge) emphasized this performative neutrality: “As a judge, I have to make sure that all parties get a fair opportunity to speak. The questions I ask should help clarify the facts without showing partiality. Clear and firm communication is essential to maintain the integrity of the trial process.”

These practices reflect judicial communication, where authority and impartiality are enacted through one-way, scripted formats, consistent with Goffman’s notion of gatherings (1963). One-way communication thus serves as a performative act of legitimacy, ensuring order and neutrality in the courtroom.

3.2.2 Multi-directional communication flow

Involves a reciprocal interaction between two or more participants, where there is a dynamic exchange of information. For example, during the examination of witnesses, there is a dialog between judges, prosecutors, lawyers, and witnesses. This flow of communication allows for further clarification, affirmation, and exploration of information through questions and answers.

In contrast, multi-directional communication arises during evidentiary stages, especially in witness examinations and cross-examinations. Here, communication shifts dynamically among judges, prosecutors, defense counsel, and witnesses, producing interactional feedback and negotiation. Observation, Trial 2, In a narcotics case, the prosecutor asked a witness, “Did you see the defendant at the scene?” The witness hesitated. Defense counsel immediately objected: “Objection, leading question.” The judge sustained the objection and instructed the prosecutor to rephrase. This exchange demonstrated a multi-actor flow in which turn-taking, feedback, and regulation unfolded interactively. Observation, Trial 2 (Judge’s Intervention): When a witness struggled with a complex legal term, the judge rephrased the question in simpler language. This adjustment allowed the witness to answer accurately, reflecting supportive communication embedded within adversarial exchanges. Informant B (Prosecutor) highlighted the importance of this interactive process: “As a prosecutor, my main task is to present strong evidence and arguments. Communication with witnesses and experts is very important, as their testimony can strengthen or weaken our case.” Informant C described the balance between adversarial advocacy and fairness: “My role is to ensure that my client’s rights are protected. This includes presenting arguments clearly and effectively and challenging the evidence presented by the prosecutor. Good communication with the defendant is also very important to ensure that the defense strategy can run well”.

These exchanges operationalize forensic communication (Howes, 2015), where competing narratives are tested in front of the bench. At the same time, judicial interventions regulate these adversarial dynamics, ensuring that the process remains both rigorous and procedurally fair.

Each of these communication streams has characteristics that affect the dynamics of the trial. One-way communication flows tend to be formal and hierarchical, emphasizing authority and structure in the judicial process. In contrast, multi-directional communication flows are more interactive and participatory, allowing for an in-depth exploration of the facts of the case through direct interaction between the various parties involved. Understanding the flow of communication in a trial is important for participants to optimize their communication strategies. By adapting the communication approach according to the flow that occurs, the effectiveness of the judicial process can be improved, ensuring that each party can convey their information and arguments efficiently and on point.

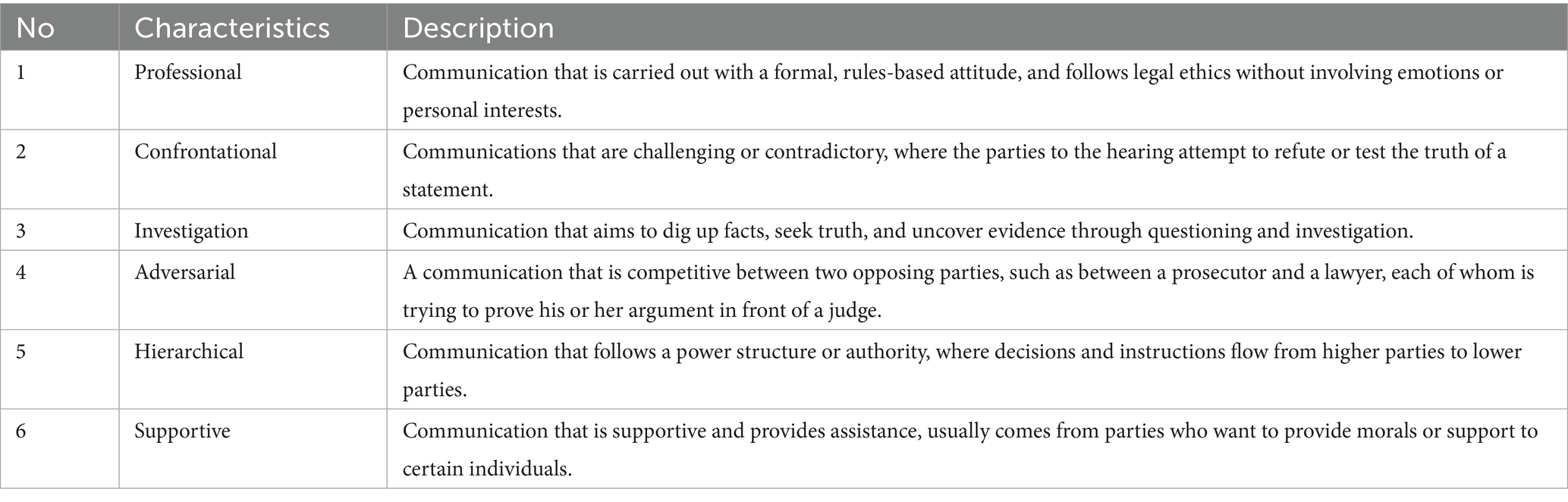

3.3 Communication characteristics in the courtroom

Overall, based on the information of the informants, communication in the trial does have distinctive characteristics and is different in other communication contexts. The informants explained several characteristics that occurred, that communication in the courtroom is a combination of various characteristics that reflect the complexity of the interaction between the participants involved in the trial. This characteristic arises because communication in the trial is influenced by various roles, goals, and goals. Communication that occurs between participants has various characteristics, including procedural, confrontational, hierarchical, investigativehierari, opposite, and mutually supportive. The following is a description of each of the characteristics:

3.3.1 Professional

Communication in the courtroom is carried out formally and in accordance with the rule of law. Judges, prosecutors, and lawyers use language that is polite, unemotional, and should be based on facts. For example, the judge must speak neutrally and objectively, while the prosecutor drafts the indictment based on evidence, not assumptions. This professional attitude is important so that the trial runs fairly and according to the rules. Communication in the trial is professional, where judges, prosecutors, and lawyers use formal legal language and follow established procedures. Professionals are depicted in the presentation of arguments, examination of witnesses, and the decision-making process. Informant A and Informant C, explained that the professional in the trial is that communication that is carried out with a formal, rules-based attitude, and follows legal ethics without involving emotions or personal interests, is a must “… The judge must maintain a balance between justice and law. Every word spoken must be neutral, objective, and based on the facts revealed in the trial” Meanwhile, informant C, revealed “We cannot be careless in drafting indictments. Any statement must be based on legal evidence and facts, not personal assumptions or opinions.” Referring to this information, professional is defined as an objective attitude and responsibility carried out through formal communication.

3.3.2 Confrontational

Communication in the courtroom is often conflicting, especially between prosecutors and lawyers who have conflicting interests. The prosecutor is tasked with proving the defendant’s guilt, while the lawyer tries to defend his client by refuting the accusations made. Informant D, a lawyer interviewed revealed that, “sometimes, lawyers do, often face fierce arguments with prosecutors, but that is part of the legal system. We must maintain ethics, even in the face of conflicting arguments.” This confrontation is seen in witness examination sessions, such as in cases where the prosecutor asks, “Are you sure you did not see the defendant at the scene? CCTV evidence shows that the defendant was at the location at 22.00 WIB.” The lawyer then denied with an interruption, “The presence of the defendant at the location does not necessarily prove that he committed a criminal act. How can you be sure that the defendant is the real perpetrator?” In a situation like this, the judge plays the role of controlling the course of the trial so that the debate does not go beyond the limits of legal ethics.

3.3.3 Investigative

Another characteristic found is investigative communication, judges, prosecutors, and lawyers to dig up facts and test the validity of information from witnesses or defendants. The judge often asks clarifying questions to ensure consistency in the testimony given, as in the case where the judge asks, “Brother witness, in the BAP you mentioned that the incident occurred at 9:00 p.m., but the police report said it was 10:00 p.m. Can you explain the difference?.” The interviewed judge explained, “Our job is not only to hear, but also to clarify and ensure that there is no contradictory information. We have to find the truth based on the evidence.” Based on this information, investigative is evidenced by the process of digging or searching for more detailed and in-depth information.

3.3.4 Adversarial

In addition to investigations, communication in the courtroom is also opposite, where the legal system allows for resistance through communication. Resistance is characterized by presenting rebuttal arguments. This interaction is still carried out within ethical limits. One prosecutor explained that, “We are not looking for enemies in court, but our job is to prove the truth based on evidence.” In a trial, communication resistance was seen in the debate between the prosecutor and the lawyer. The prosecutor stated, “The defendant has a clear motive, namely financial gain from the criminal act committed.” Meanwhile, the lawyer countered, “There is no direct evidence to suggest that my client benefited financially from this incident.”

3.3.5 Hierarchical

Communication in trials also shows a hierarchical and formal structure, where judges have the highest authority in controlling the course of the trial, while prosecutors, lawyers, defendants, and witnesses have a predetermined role in the legal system. One witness interviewed revealed that, “I felt pressure when giving testimony because the communication in the courtroom was very formal and strict. Every answer I give must be in accordance with the facts and must not be mispronounced.” This hierarchical structure ensures that the trial runs in accordance with established legal procedures and prevents disruption during the process. An example of formal communication can be seen in the judge’s order, “I open this trial and I declare it open to the public. Prosecutor, please read the indictment.” This formality ensures that the trial takes place according to procedure and that there are no errors in the course of the trial

3.3.6 Supportive

Communication in the courtroom can also be mutually supportive, especially in the interaction between the judge and the witness or between the lawyer and his client. In some cases, judges show empathy for witnesses who testify in emotional cases. A traumatized witness stated that, “The judge gave me time to calm down before continuing to testify. It really helped me to speak more clearly.” In addition, it can also be seen in the lawyer’s interaction with his client. Lawyers often provide moral and technical support to their clients before the trial begins in order to better deal with the legal process.

In a nutshell, the following is a classification in the form of a Table 2:

Communication in the courtroom is not just an exchange of information, but a key interaction in running the legal system effectively. The combination of the various communication characteristics of professionalism, confrontation, investigation, and hierarchical structure creates a communication mechanism that serves to ensure justice for all parties involved. However, the main challenge in trial communication is maintaining a balance between critical debate and legal ethics, as well as ensuring that all participants can participate without intrusive pressure.

4 Discussion

This study interprets the six observed characteristics through an explicit framework integrating Goffman’s concept of gatherings (1963), Judicial Communication (Roach Anleu and Mack, 2015) and Forensic Communication (Howes, 2015), positioning the Indonesian criminal courtroom as a communicative space in which authority is performed, facts are contested, and participants’ “faces” are managed.

Authority and order are enacted through ritual openings such as standing for the bench, the judge’s control of turn-taking, and scripted agenda shifts from indictment to evidence, claims, and verdict. These practices, which Goffman describes as a gathering, materialize judicial authority and neutrality, framing one-way communication during instructions and verdict delivery. The professional and hierarchical features observed are therefore not mere stylistic preferences but institutional performances of legitimacy that display impartiality while keeping proceedings orderly and intelligible.

Contestation and truth-testing emerge most visibly during witness examination and cross-examination, when communication shifts to a multi-directional mode in which prosecutors and defense counsel challenge claims, probe inconsistencies, and present counter-narratives. The confrontational and adversarial characteristics identified in this study constitute the core of forensic testing, where claims are advanced, scrutinized, and either stabilized or weakened. Judges’ clarifying questions extend this scrutiny, blending judicial and forensic communication to ensure that fact-finding remains rigorous yet procedurally fair, which is captured in the investigative dimension.

Care and procedural fairness are also embedded in supportive practices such as allowing pauses, rephrasing complex questions, and acknowledging stress, which protect participants’ “face” (Goffman) and promote perceived fairness (Judicial Communication). In the Indonesian context, where judges actively steer proceedings, such micro-accommodations help sustain participation without diluting neutrality.

International scholarship shows parallel dynamics, such as linguistic accommodation(Aronsson et al., 1987), presence and participation in virtual courts (Rossner and Tait, 2023),and the emotional dimension of legal communication (Bandes and Feigenson, 2020; Ellsworth and Dougherty, 2016), while Indonesian studies (Widodo, 2019, 2020, 2022) have mapped legal communication models and the dramaturgy of defendants. This study contributes by empirically characterizing courtroom communication into six interlocking features and systematically linking them to socio-legal communication theory.

In particular, the dual flow—one-way authority-performing communication versus multi-directional adversarial testing—explains how Indonesian trials balance order and contestation to sustain legitimacy. By treating the courtroom as a gathering where judicial authority is performed and forensic testing unfolds, the findings clarify why professionalism and hierarchy must coexist with confrontation and investigation, and this integrated view further explains how specific communicative practices such as controlled turn-taking, targeted clarification, and ethical rebuttal translate into fairer and more effective adjudication.

5 Conclusion

Communication in the courtroom involves multiple participants including judges, prosecutors, defense lawyers, witnesses, and defendants, each with distinct objectives, and unfolds through complex interactional processes. This study identifies six interrelated characteristics of courtroom communication: professional, investigative, supportive, confrontational, adversarial, and hierarchical. Theoretically, the study advances courtroom communication research by integrating socio-legal frameworks such as Goffman’s gatherings, Judicial Communication, and Forensic Communication to demonstrate how authority, contestation, and fairness are simultaneously enacted in Indonesian criminal trials. This conceptual integration enriches the literature by showing that courtroom interaction is not merely procedural but constitutes a communicative practice that produces legitimacy and justice.

Practically, the findings offer important implications for Indonesian legal practice. Judges must remain firm in controlling communication while providing supportive space for vulnerable participants; prosecutors and defense lawyers should prioritize professionalism and clarity in argumentation; and witnesses and defendants must be enabled to present information without undue pressure. Strengthening these communicative practices can enhance transparency, fairness, and public trust in the judicial system. Therefore, this study confirms that courtroom communication is not simply a technical aspect of trial procedure but a decisive factor in shaping justice that is more accountable, effective, and legitimate.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because this study did not require formal ethical approval, as it did not involve sensitive personal data or medical procedures. However, all participants gave informed consent, and the research was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set by the Faculty of Communication Sciences, Universitas Bhayangkara Jakarta Raya. Additionally, confirmation of the completion of the research was obtained from the informants. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AW: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Visualization, Investigation, Validation, Resources, Data curation, Conceptualization, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aceron, R. M. (2015). Conversational analysis: the judge and lawyers’ courtroom interactions. Asia Pac. J. Multidiscip. Res. 3, 120–127.

Aronsson, K., Jönsson, L., and Linell, P. (1987). The courtroom hearing as a middle ground: speech accommodation by lawyers and defendants. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 6, 99–115. doi: 10.1177/0261927X8700600202

Bandes, S. A., and Feigenson, N. (2020). Virtual trials: necessity, invention, and the evolution of the courtroom. SSRN Electron. J. 68:1275. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3683408

Cowles, K. M., and Cowles, K. M. (2011). Communication in the courtroom. Honors college and center for interdisciplinary studies. South Carolina: Coastal Carolina University.

Donoghue, J. (2017). The rise of digital justice: courtroom technology, public participation and access to justice. Mod. Law Rev. 80, 995–1025. doi: 10.1111/1468-2230.12300

Elbers, N. A., van Wees, K. A. P. C., Akkermans, A. J., Cuijpers, P., and Bruinvels, D. J. (2012). Exploring lawyer-client interaction: a qualitative study of positive lawyer characteristics. Psychol. Inj. Law 5, 89–94. doi: 10.1007/s12207-012-9120-0

Ellsworth, P. C., and Dougherty, A. (2016). Appraisals and reappraisals in the courtroom. Emot. Rev. 8, 20–25. doi: 10.1177/1754073915601227

Farley, E.J., Jensen, E., and Rempel, M., (2014a). Improving courtroom communication: a procedural justice experiment in Milwaukee 88.

Farley, E.J., Jensen, E., and Rempel, M. (2014b). Improving courtroom communication: a procedural justice experiment in Milwaukee.

Gordon, R. A., and Druckman, D. (2018). “Nonverbal behaviour as communication: approaches, issues, and research” in The handbook of communication skills, fourth edition. Ed. O. Hargie

Grossman, N. (2019). Just looking: justice as seen in Hollywood courtroom films. Law Cult. Humanit. 15, 62–105. doi: 10.1177/1743872114564032

Hans, V. P., and Sweigart, K. (1993). Jurors’ views of civil lawyers: implications for courtroom communication. Indiana Law J. 68, 1297–1332.

Hawilo, M., Albrecht, K., Rountree, M. M., and Geraghty, T. (2022). How culture impacts courtrooms: an empirical study of alienation and detachment in the Cook County court system. J. Crim. Law Criminol. 112. doi: 10.21428/cb6ab371.7d359846

Howes, L. M. (2015). The communication of forensic science in the criminal justice system: a review of theory and proposed directions for research. Sci. Justice 55, 145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.scijus.2014.11.002

Leung, J. H. C. (2012). Judicial discourse in Cantonese courtrooms in postcolonial Hong Kong: the judge as a godfather, scholar, educator and scolding parent. Int. J. Speech Lang. Law 19, 239–261. doi: 10.1558/ijsll.v19i2.239

LeVan, E. A. (1984). Nonverbal communication in the courtroom: attorney beware. Law Psychol. Rev. 8, 83–104.

Matoesian, G. (2017). Communication in investigative and legal contexts: integrated approaches from forensic psychology, linguistics and law enforcement, edited by Gavin Oxburgh, Trond Myklebust, Tim Grant and Rebecca Milne. Police Pract. Res. 21, 95–96. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2017.1283901

Maynard, D. W., Maynard, D. W., American, S., Foundation, BWinter, N., Maynard, D. W., et al. (2014). “Communication in investigative and legal contexts: integrated approaches from forensic psychology, linguistics and law enforcement” in Police practice and research. eds. G. Oxburgh, T. Myklebust, T. Grant, and R. Milne, vol. 21 (Malden: Oxford and Chichester: Wiley Blackwell), 1–33.

McCaul, K. (2016). “Understanding courtroom communication through cultural scripts,” Exploring Courtroom Discourse: The Language of Power and Control.

Philp, G. (2022). Listening and responding to the future of virtual court: A report on the future of virtual courts in Canada, Nova Scotia Court of Appeal Canada

Philips, S. U. (1985). Linguistic evidence: Language, power, and strategy in the courtroom by William M. O’Barr. Lang. Soc. 14, 113–117. doi: 10.1017/S0047404500011015

Roach Anleu, S., and Mack, K. (2015). Performing authority: communicating judicial decisions in lower criminal courts. J. Sociol. 51, 1052–1069. doi: 10.1177/1440783313495765

Rossner, M., and Tait, D. (2023). Presence and participation in a virtual court. Criminol. Crim. Justice 23, 135–157. doi: 10.1177/17488958211017372

Rossner, M., Tait, D., and McCurdy, M. (2021). Justice reimagined: challenges and opportunities with implementing virtual courts. Curr. Issues Crim. Justice 33, 94–110. doi: 10.1080/10345329.2020.1859968

Suffet, F. (1966). Bail setting: a study of courtroom interaction. Crime Delinq. 12, 318–331. doi: 10.1177/001112876601200403

Turner, K., and Hughes, N. (2022). Supporting young people’s cognition and communication in the courtroom: a scoping review of current practices. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 32, 175–196. doi: 10.1002/cbm.2237

Walenta, J. (2020). Courtroom ethnography: researching the intersection of law, space, and everyday practices. Prof. Geogr. 72, 131–138. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2019.1622427

Widodo, A. (2019). Model Komunikasi Penegak Hukum dalam Ruang Persidangan di Pengadilan Negeri Jakarta Pusat. Jurnal Penelitian Komunikasi 22, 139–154. doi: 10.20422/jpk.v22i2.660

Widodo, A. (2020). Model Komunikasi Pemeriksaan Dalam Sidang Agenda Pembuktian Perkara di Pengadilan. J. Komun. 12:157. doi: 10.24912/jk.v12i2.8447

Widodo, A. (2022). Dramatisme Terdakwa di Ruang Pengadilan. Jurnal ILMU KOMUNIKASI 19, 87–102. doi: 10.24002/jik.v19i1.3600

Widodo, A. (2024a). Transformation model for online trials at the Bekasi District court. Jurnal Komun. 16, 359–379. doi: 10.24912/jk.v16i2.29002

Widodo, A. (2024b). Communication type in trial: ethnography communication in Indonesian criminal courtroom process. J. Intercult. Commun. 24, 156–167. doi: 10.36923/jicc.v24i3.891

Widodo, A., Hidayat, D. R., Venus, A., and Suseno, S. (2018). Communication and service quality in public sector: an ethnographic study of a state court of justice in Jakarta. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 7:7553. doi: 10.14419/ijet.v7i3.25.17553

Keywords: courtroom communication, criminal trials, interactional dynamics, judicial authority, Indonesia

Citation: Widodo A (2025) Courtroom communication: identification of the communication characteristics of criminal trials in Indonesian courts. Front. Commun. 10:1623307. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1623307

Edited by:

Douglas Ashwell, Massey University Business School, New ZealandCopyright © 2025 Widodo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aan Widodo, YWFuLndpZG9kb0Bkc24udWJoYXJhamF5YS5hYy5pZA==

Aan Widodo

Aan Widodo